PUBLISHED

JULY

2020

PUBLISHED

August

2020

United States Secret Service

NATIONAL THREAT ASSESSMENT CENTER

MASS ATTACKS IN PUBLIC SPACES - 2019

U.S. Department of Homeland Security

National Threat Assessment Center

U.S. Secret Service

U.S. Department of Homeland Security

August 2020

is publication is in the public domain. Authorization to copy and distribute this publication in whole or in part is granted.

However, the U.S. Secret Service star insignia may not be otherwise reproduced or used in any other manner without advance

written permission from the agency. While permission to reprint this publication is not necessary, when quoting, paraphrasing,

or otherwise referring to this report, the citation should be: National reat Assessment Center. (2020). Mass Attacks in Public

Spaces - 2019. U.S. Secret Service, Department of Homeland Security.

is report was authored by the following sta of the U.S. Secret Service

National reat Assessment Center (NTAC)

Diana Drysdale, M.A.

Supervisory Social Science Research Specialist

Ashley Blair, M.A.

Lead Social Science Research Specialist

Arna Carlock, Ph.D.

Social Science Research Specialist

Aaron Cotkin, Ph.D.

Social Science Research Specialist

Brianna Johnston, M.A.

Social Science Research Specialist

Steven Driscoll, M.Ed.

Supervisory Social Science Research Specialist

David Mauldin, M.S.W.

Social Science Research Specialist

Jeffrey McGarry, M.A.

Social Science Research Specialist

Jessica Nemet, M.A.

Social Science Research Specialist

Natalie Vineyard, M.S.

Social Science Research Specialist

Lina Alathari, Ph.D.

Chief

Special thanks to the following for their contributions to the project:

Chris Foley, M.S.S.W.

Assistant to the

Special Agent in Charge-NTAC

Katie Lord

Domestic Security

Strategist, Region 2-NTAC

Arlene Macias

Domestic Security

Strategist, Region 4-NTAC

Peter Langman, Ph.D.

Psychologist and Author

RAND Corporation

Homeland Security Operational

Analysis Center

Mass Attacks in Public Spaces - 2019 LIMITED TO OPEN SOURCE INFORMATION 2

The U.S. Secret Service’s National Threat Assessment Center (NTAC) is an integral resource for the agency’s no-fail

mission to safeguard this nation’s highest elected ofcials. NTAC’s continuous efforts to ensure the informed

development of prevention strategies through research has also enabled outreach programs and publications that assist

our protective and public safety partners in their missions to prevent targeted violence in communities across the

United States.

This latest study, titled Mass Attacks in Public Spaces – 2019, examines 34 targeted attacks that occurred in public or

semi-public spaces (e.g., schools, places of business, houses of worship, open spaces) from January through December

2019. This report is the agency’s third in a series of annual reports that have examined mass attacks in the United States,

during which three or more individuals were harmed. Since this project began in 2017, there have been 89 mass attacks

involving 92 attackers that occurred in various locations throughout the nation. Understanding the key factors in

preventing these attacks is even more critical this year with the COVID-19 pandemic causing additional stressors in the

lives of our citizens.

To inform prevention efforts, NTAC researchers studied the tactics, backgrounds, and pre-attack behaviors of the

perpetrators to identify and afrm recommended best practices in threat assessment and prevention. Implications

include the identication of potential threats and individuals exhibiting concerning behavior. Strategic development of

interventions and risk mitigation efforts tailored to those specic individuals are also a core aspect of this study. We

encourage our public safety partners to review the information and apply it to their own best practices for providing a

safe environment for communities across the country.

Law enforcement ofcers, mental health professionals, workplace managers, school personnel, faith-based leaders, and

many others all play a signicant role in the multidisciplinary team approach that is the foundation of the eld of threat

assessment. The Secret Service is committed to facilitating information-sharing across all platforms of targeted violence

prevention and public safety. Our longstanding collaborative partnerships with these valuable members of the

community serve to enhance public safety, and strengthen our mandate to keep our nation’s leaders safe.

James M. Murray

Director

The U.S. Secret Service’s National Threat Assessment Center (NTAC) was created in 1998 to provide guidance on threat assessment both within

the U.S. Secret Service and to others with criminal justice and public safety responsibilities. Through the Presidential Threat Protection Act of

2000, Congress formally authorized NTAC to conduct research on threat assessment and various types of targeted violence; provide training on

threat assessment and targeted violence; facilitate information-sharing among agencies with protective and/or public safety responsibilities; provide

case consultation on individual threat assessment investigations and for agencies building threat assessment units; and develop programs to promote

the standardization of federal, state, and local threat assessment processes and investigations.

MESSAGE FROM THE DIRECTOR

Mass Attacks in Public Spaces - 2019 LIMITED TO OPEN SOURCE INFORMATION 3

TABLE OF CONTENTS

United States Secret Service

NATIONAL THREAT ASSESSMENT CENTER

Mass Attacks in Public Spaces - 2019 LIMITED TO OPEN SOURCE INFORMATION

Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 5

Overview of the attacks ............................................................................................................. 7

Weapons ............................................................................................................................... 7

Locations .............................................................................................................................. 8

Timing .................................................................................................................................. 9

Targeting ............................................................................................................................ 10

Resolution .......................................................................................................................... 10

Motives ............................................................................................................................... 11

e attackers .....................................................................................................................13

Demographics ................................................................................................................... 13

Employment history ......................................................................................................... 14

Substance use .................................................................................................................... 14

Prior criminal charges ...................................................................................................... 15

History of violence and domestic violence.................................................................... 16

Mental health .................................................................................................................... 17

Psychotic symptoms .................................................................................................. 17

Depression ................................................................................................................. 18

Mental health treatment........................................................................................... 18

Beliefs ................................................................................................................................. 19

Fixations ............................................................................................................................. 19

Online inuence ............................................................................................................... 20

8chan .......................................................................................................................... 20

Online misogyny ....................................................................................................... 20

Stressors within ve years ................................................................................................ 21

Financial instability .................................................................................................. 21

Home life factors ....................................................................................................... 22

Triggering event ........................................................................................................ 22

reats and other concerning communications ........................................................... 22

Behavioral changes ........................................................................................................... 23

Social isolation .................................................................................................................. 24

Elicited concern ................................................................................................................ 25

Conclusion ........................................................................................................................26

Summary and tables .........................................................................................................29

List of incidents ................................................................................................................. 32

Endnotes ............................................................................................................................ 33

INTRODUCTION

While our nation responds to the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic, we must also contend with the tragic aermath of

mass violence that has impacted our communities. Acts of targeted violence aect cities and towns of all sizes, and impact

individuals in the places where we work, learn, and otherwise carry out our daily activities. e response to this problem, like

many others, requires a community-oriented approach. Although law enforcement agencies plays a central role in preventing

targeted violence, they must be joined by government ocials and policy makers, mental health providers, employers, schools,

houses of worship, and the general public, all of whom have a role to play in keeping our communities safe.

What is

reat Assessment?

In the 1990s, the U.S. Secret

Service pioneered the eld of threat

assessment by conducting research

on the targeting of public ocials

and public gures. e agency’s

threat assessment model oers law

enforcement and others with public

safety responsibilities a systematic

investigative approach to identify

individuals who exhibit threatening

or concerning behavior; gather

information to assess whether they

pose a risk of harm; and identify the

appropriate interventions, resources,

and supports to manage that risk.

Since its founding in 1998, the U.S. Secret Service National reat Assessment

Center (NTAC) has supported our federal, state, and local partners in the

shared mission of violence prevention. NTAC’s research, which informs the

U.S. Secret Service’s approach to countering targeted violence, called threat

assessment, has been made available not only to public safety professionals,

but also the general public. To enhance the impact of these research ndings,

NTAC has delivered more than 2,000 trainings to over 180,000 public safety

professionals. In addition to law enforcement, these events benet mental

health workers, school ocials, and other community stakeholders. NTAC

has further oered direct consultation to law enforcement agencies and other

partners on how to establish threat assessment programs, tailored to the

needs of each community. ese programs are designed to prevent targeted

violence using the U.S. Secret Service’s behavior-based methodologies, which

involve proactively identifying and intervening with individuals who pose a

risk of violence.

United States Secret Service

NATIONAL THREAT ASSESSMENT CENTER

Mass Attacks in Public Spaces - 2019 LIMITED TO OPEN SOURCE INFORMATION 5

is report, NTAC’s third analysis of mass attacks that were carried out in public or semi-public spaces, builds upon

Mass Attacks in Public Spaces – 2017 (MAPS – 2017) and Mass Attacks in Public Spaces – 2018 (MAPS – 2018). is

report provides further analysis of the thinking and behavior of mass attackers, as well as operational considerations

for our public safety partners.

1

e study examines 34 incidents of mass attacks – in which three or more people, not

including the attacker(s), were harmed – that were carried out by 37 attackers in public spaces across the United States

between January and December 2019. In total, 108 people were killed and an additional 178 people were injured.

e ndings from this report oer critical information that can aid in preventing these types of tragedies, and assist law

enforcement, schools, businesses, and others in the establishment of appropriate systems to recognize the warning signs

and intervene appropriately. Key ndings from this analysis include:

2

• e attacks impacted a variety of locations, including businesses/workplaces, schools, houses of worship, military

bases, open spaces, residential complexes, and a commercial bus service.

• Most of the attackers used rearms, and many of those rearms were possessed illegally at the time of the attack.

• Many attackers had experienced unemployment, substance use or abuse, mental health symptoms, or recent

stressful events.

• Attackers oen had a history of prior criminal charges or arrests and domestic violence.

• Most of the attackers had exhibited behavior that elicited concern in family members, friends, neighbors, classmates,

co-workers, and others, and in many cases, those individuals feared for the safety of themselves or others.

ese violent attacks impacted a variety of community sectors and were perpetrated by individuals from dierent

backgrounds and with varying motives. However, similar to previous Secret Service research, common themes were

observed in the behaviors and situational factors of the perpetrators, including access to weapons, criminal history,

mental health symptoms, threatening or concerning behavior, and stressors in various life domains. e presence of these

diverse themes shows the need for a multidisciplinary threat assessment approach to violence prevention. Community

professionals, with the proper training to recognize the warning signs, can intervene and redirect troubling behavior

before violence occurs. e Secret Service threat assessment approach encourages assessing each situation as it arises,

and applying the appropriate interventions – which may include the involvement of family members and friends, social

services, mental health professionals, faith-based organizations, or law enforcement when appropriate. is report is

intended to inform those eorts, as we strive together to keep our communities safe.

United States Secret Service

NATIONAL THREAT ASSESSMENT CENTER

Mass Attacks in Public Spaces - 2019 LIMITED TO OPEN SOURCE INFORMATION 6

OVERVIEW OF THE ATTACKS

Researchers identied 34 incidents in which three or more persons, not including the perpetrator, were harmed during a

targeted attack in a public or semi-public space in the United States between January and December 2019.

3

ree of these

attacks were perpetrated by pairs of attackers. In this section, percentages are calculated based on the 34 attacks.

WEAPONS

Most of the attacks (n = 24, 71%) involved the use of one or more rearms, which included ries, handguns, and a shotgun.

Other weapons used included bladed weapons (n = 6, 18%), vehicles (n = 4, 12%), and blunt objects (n = 3, 9%). ree

attacks involved a combination of weapons, including a rearm and a knife, a rearm and a vehicle, and a knife and glass

bottles. Several incidents involved the attackers bringing weapons to the site (e.g., additional rearms, pipe bombs) that

were not ultimately used.

Attacks Involving Firearms

Percentages shown are out of 24 incidents involving rearms

Seventeen (71%) attacks involved only handguns, six (25%) involved only long guns,

and one (4%) involved both types.

4

In four attacks, multiple rearms were used.

In at least ten (42%) of the attacks involving rearms, one or more of the attackers possessed the rearm illegally

at the time of the incident.

5

In two incidents, an attacker was a minor in possession of a handgun, which is

prohibited under federal law. In the remaining incidents, the attackers had prior felony convictions, had stolen

the rearm, had not obtained a valid weapons license, had a previous involuntary commitment to a mental health

facility, or had another factor present that prohibited them from purchasing or possessing a rearm based

on federal and/or state laws.

6

*Chart totals 37 as 3 attacks used 2 types.

Types of Weapons Used*

Bladed Weapons and

Blunt Objects

Folding knife,

switchblade,

machete,

hunting knife

Hammer,

3-ft 15-lb

piece of metal,

bottle

United States Secret Service

NATIONAL THREAT ASSESSMENT CENTER

Mass Attacks in Public Spaces - 2019 LIMITED TO OPEN SOURCE INFORMATION 7

LOCATIONS

7

e 34 attacks occurred in 21 states. Of these, 59% (n = 20)

took place at public sites that are freely accessible to the

general population, including sidewalks, restaurants, retail

stores, and a gas station. e remaining 41% (n = 14) were

carried out at semi-public sites, including workplaces, schools,

houses of worship, and military bases. e locations of attacks

in 2019, both public and semi-public, represent a variety of

key sectors in our communities, including education, business,

government, and religion.

e 34 incidents impacted 36 public sites, as two attacks were

carried out at multiple locations.

8

e type of locations most

frequently impacted were places of business/service (n = 15,

44%) and open spaces (n = 11, 32%).

e remaining locations included three educational

institutions (9%), including a high school, a K-12 public

charter school, and a university; two houses of worship (6%);

two military bases (6%); two residential complexes (6%)

9

;

and one bus (3%).

Business/Service Locations

Six service sites:

Automobile service center

Property management co.

Plasma center

Plumbing company

Cemetery

Bank

Four retail sites:

Superstore

Beer and wine store

Gas station

Small supermarket

ree restaurants/bars

One manufacturer

One city municipal building

* With the addition of the new location categories of “Residential Complex” and “Military”

in 2019, the number of open space attacks for 2017 changed from nine to eight as an

attack at an outdoor pool within a residential complex was recoded accordingly.

Public Sites*

United States Secret Service

NATIONAL THREAT ASSESSMENT CENTER

Mass Attacks in Public Spaces - 2019 LIMITED TO OPEN SOURCE INFORMATION 8

TIMING

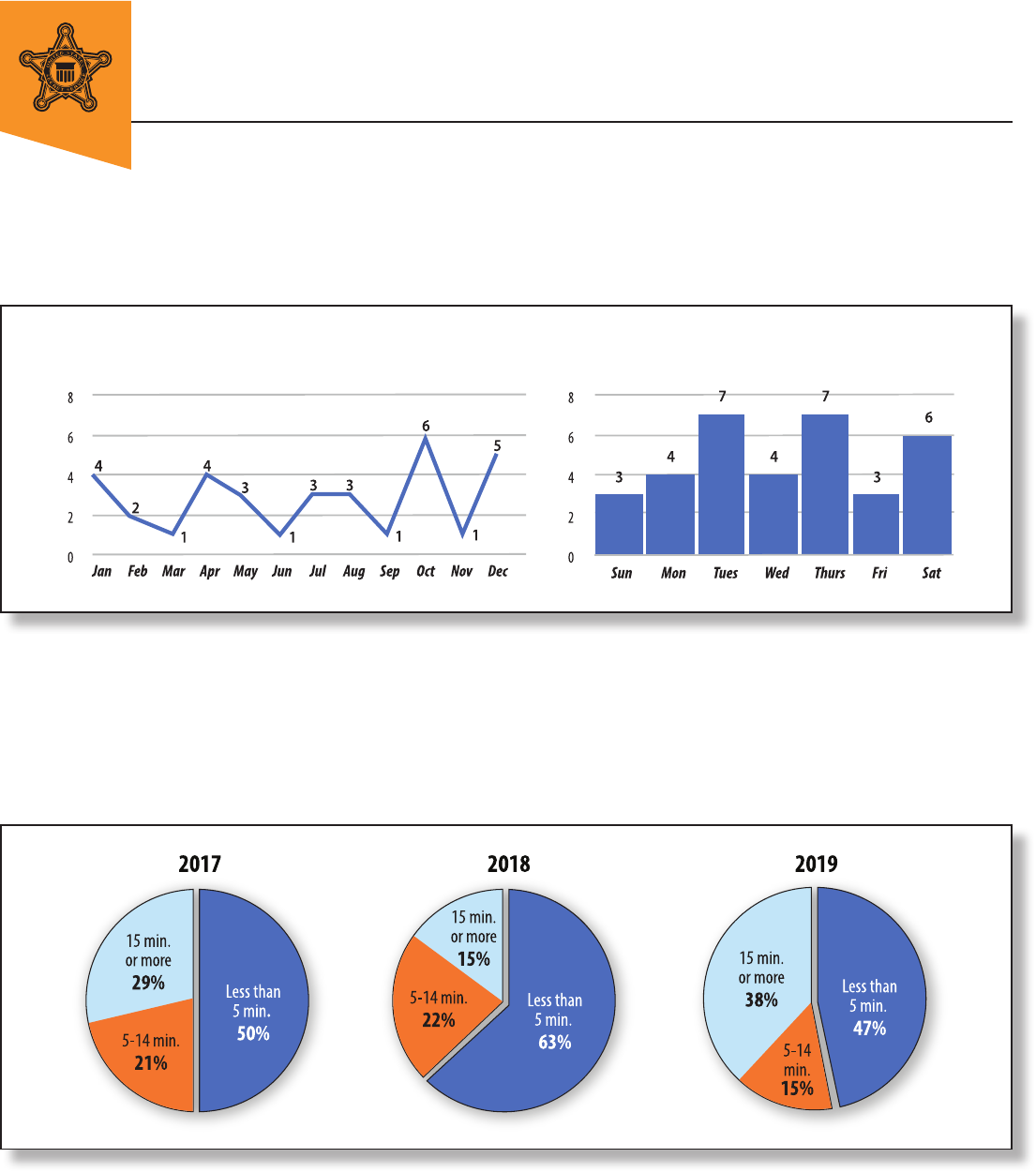

e attacks occurred on each day of the week and during every month of the year. Two-thirds of the attacks (n = 22, 65%)

took place during the day and early evening, between the hours of 7:00 a.m. and 7:00 p.m.

Consistent with previous studies on targeted violence, the attacks in this study were frequently short in duration. For

example, one attack targeting a bar district lasted only 32 seconds, yet still resulted in 9 individuals killed and 20 more

injured. Just under half (n = 16, 47%) of the attacks in 2019 ended within ve minutes from when the incident was

initiated. However, over one-third (n = 13, 38%) of the attacks in 2019 lasted 15 minutes or more, a larger percentage than

those in 2017 and 2018. ese incidents included attackers engaging in standos with law enforcement, moving through

oce buildings, and some who moved between locations by car or on foot.

LONGEST ATTACK: On December 10, 2019, at around 12:21 p.m., a 47-year-old male and a 50-year-old female

opened re on a kosher market, killing three and injuring at least three. By 12:30 p.m., 911 received calls regarding

shots red, and by 12:43 p.m., numerous law enforcement personnel responded to the scene. e ensuing gun battle

lasted until 3:25 p.m., when police breached the storefront using an armored vehicle. In the end, both attackers were

killed. e attack lasted 3 hours and 26 minutes.

Attacks by Day of the WeekAttacks by Month

United States Secret Service

NATIONAL THREAT ASSESSMENT CENTER

Mass Attacks in Public Spaces - 2019 LIMITED TO OPEN SOURCE INFORMATION 9

TARGETING

e attacks resulted in harm to 286 people (108 killed and 178 injured). In three-quarters of the incidents (n = 26, 76%),

the attackers directed harm only at random persons. In the remaining one-quarter of the incidents (n = 8, 24%), the

attacker appeared to have pre-selected specic targets. In all of the incidents involving specic targets, at least one of the

specically targeted individuals was harmed, in addition to at least one random person. e eight incidents involving

specic targets were also all motivated, at least in part, by some type of grievance that was related to a workplace, domestic,

or other issue.

On February 21, 2019, a 35-year-old shot and killed his girlfriend near their residence. e attacker then walked

approximately half a mile to a gas station/convenience store and opened re on random people there, killing the

co-owner of the store and injuring an employee and a customer. e attacker then returned to the scene of the rst

shooting, near his home. He threw away his handgun when he saw the police and was arrested just aer midnight.

ough police called the initial shooting of the girlfriend domestic in nature, they have not released any information to

suggest any connection the attacker may have had to the gas station or any of the victims.

RESOLUTION

10

Almost half of the attacks (n = 15, 44%) ended when the attackers departed the scene on their own. Four attackers called

911 to report their attack and identify themselves as the perpetrator.

Eight attacks (24%) were brought to an end by law enforcement intervention at the scene, including one incident that was

stopped by a private security guard at a school. In ve of these incidents, the attackers were killed by law enforcement. e

remaining attacks ended when the attacker’s weapon became inoperable (n = 5, 15%), as a result of bystander intervention

(n = 3, 9%), or when the attacker committed suicide at the scene (n = 3, 9%). ree additional attackers committed suicide

aer leaving the scene.

11

United States Secret Service

NATIONAL THREAT ASSESSMENT CENTER

Mass Attacks in Public Spaces - 2019 LIMITED TO OPEN SOURCE INFORMATION 10

MOTIVES

Motives for violence are oen multifaceted. e most

common motives identied for mass attacks in 2019

were related to grievances, mental health symptoms,

and ideological/racial bias.

Grievances

In nearly one-third of the incidents (n = 11, 32%),

attackers were retaliating for perceived wrongs related

to specic issues in their lives. ese grievances most

oen related to some type of personal factor (n = 8,

24%), such as an ongoing feud with neighbors, being

kicked out of a retail establishment, being teased or

bullied, facing an impending eviction, or being angered

and frustrated about college debt and job prospects. e

remaining attacks were motivated by grievances related

to workplace issues (n = 3, 9%) or domestic situations

(n = 1, 3%).

COMPONENTS TO MOTIVE* 2017 2018 2019

Grievances 46% 52% 32%

Personal 2 6 8

Workplace 6 3 3

Domestic 5 6 1

Mental health/psychosis 14% 19% 21%

Ideological/racial bias 21% 7% 21%

Fame 4% 4% 6%

Political 4% 0% 3%

Desire to kill — — 3%

Undetermined 14% 22% 32%

On December 19, 2019, a 66-year-old resident entered the administrative oce of his assisted living facility and

opened re, killing one and injuring two before returning to his apartment and fatally shooting himself. e attacker

had been the subject of complaints for smoking in his apartment, which was prohibited. e complaints resulted in his

rent being increased, and he was warned that he could be evicted if the violations continued.

Related to symptoms of mental health or psychosis

In seven incidents (21%), the attackers’ motives were related to their symptoms of mental illness, including at least three

who claimed to have heard voices commanding them to kill, and others who experienced delusional or paranoid beliefs.

On June 17, 2019, a 33-year-old male drove onto the sidewalk and struck a pedestrian, injuring him. He then drove

down the street and onto the sidewalk again, this time killing a pregnant woman, her unborn child, and her two-

year-old son before crashing into a business, injuring an employee. e attacker attempted to ee but was detained by

bystanders until police arrived. e attacker later told police that just prior to the attack, he heard a voice in his head

that told him to kill methamphetamine addicts and that the baby’s stroller had meth in it.

Ideological/racial bias

Seven incidents (21%) involved attackers who were motivated to violence by extreme or hateful views. Attackers targeted

members of various groups including Jewish, Muslim, Asian, or Hispanic people, as well as police and U.S. soldiers. For

three of these incidents, the attackers were also experiencing mental health symptoms that inuenced their motives.

* The percentages for each year do not total 100 as some attackers had multiple motives.

United States Secret Service

NATIONAL THREAT ASSESSMENT CENTER

Mass Attacks in Public Spaces - 2019 LIMITED TO OPEN SOURCE INFORMATION 11

On April 23, 2019, during the evening rush hour, a 34-year-old male drove his car through a crowd of pedestrians,

injuring eight at an intersection. He was allegedly targeting two people in the crowd, believing they were Muslim. e

attacker’s car ultimately jumped the curb and hit a tree. He then exited his vehicle, repeatedly said, “I love you Jesus,”

and laid facedown until police arrived and arrested him. e attacker had a history of PTSD and psychotic symptoms.

Nine of the attackers were inuenced by, or showed interest in, past perpetrators of mass violence. Some attackers

documented their admiration of past attackers in their own manifestos or in social media postings, while others spent

time consuming information about past attacks. Five of these attackers referenced other attackers from earlier in 2019

prior to committing their own acts of violence. While three of them referenced other incidents contained in this report,

the remaining two named a mass attacker who targeted public places outside of the United States. One additional

attacker researched a female who was so obsessed with the 1999 Columbine High School shooting that she traveled

from Florida to the Columbine High School area in April 2019. She purchased a weapon, but committed suicide prior

to initiating an attack.

At least six attackers made statements or engaged in prior behaviors that indicated they did not intend to survive their

planned attack. Among these six attackers, four committed suicide aer engaging in the attack.

United States Secret Service

NATIONAL THREAT ASSESSMENT CENTER

Mass Attacks in Public Spaces - 2019 LIMITED TO OPEN SOURCE INFORMATION 12

THE ATTACKERS

DEMOGRAPHICS

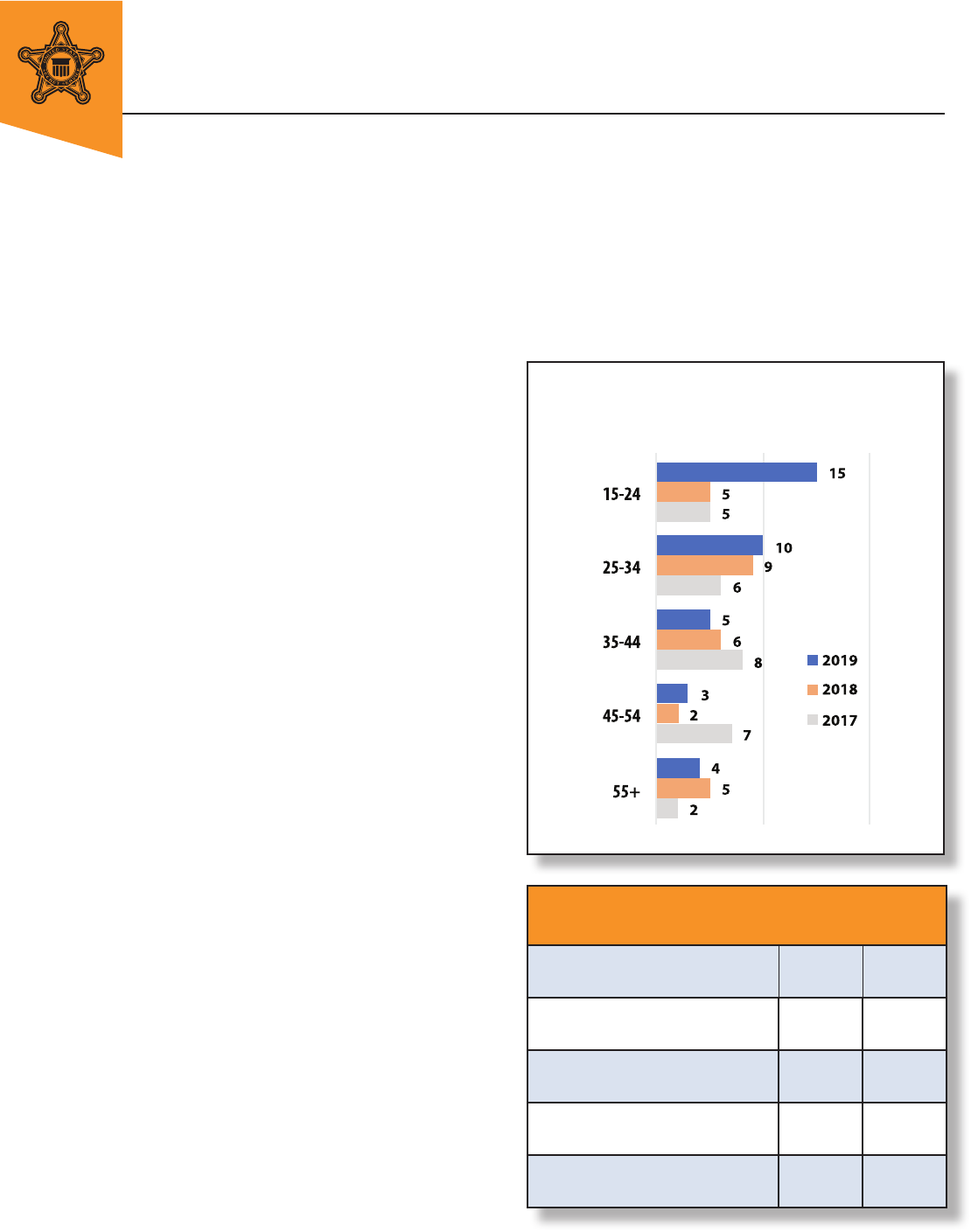

Consistent with previous Secret Service analyses of mass attacks,

nearly all of the attackers from 2019 were born male (n = 34,

92%). ere was one female attacker, and two attackers were

born female but identied as male at the time of the attacks. e

attackers’ ages ranged from 16 to 80, with an average age of 33.

Over two-thirds of the attackers (n = 25, 68%) were under the

age of 35. More attackers in 2019 were in the 15-24 age range

than the previous two years combined.

YOUNGEST: On November 14, 2019, on his 16th

birthday, a student opened re at his high school and

fatally shot two students and injured three others before

fatally shooting himself. e attacker had struggled with

his alcoholic father’s death two years before and was

reportedly having recent problems with his girlfriend.

In the months and days leading up to the attack, some

classmates described the attacker as acting strangely or

appearing depressed while others observed him cracking

jokes and described him as acting normally.

OLDEST: On October 3, 2019, an 80-year-old resident

walked into the lobby of his access-controlled senior

apartment complex and opened re, fatally shooting

one fellow resident, and injuring another and his former

caretaker. About a month prior, the attacker had been

turned down when he asked his former caretaker to

become his mistress, and he had an ongoing feud with the

resident he killed.

According to public information, half of the attackers were

White non-Hispanic (n = 19, 51%), 10 attackers (27%) were

Black/African American, and 5 attackers (14%) were Hispanic.

Two (5%) of the attackers belonged to multiple categories, and

the racial identity of one attacker (3%) could not be determined.

All of the mass attacks previously studied by the U.S. Secret Service - those that occurred in 2017 and 2018 - were carried

out by lone attackers. In 2019, however, three attacks were carried out by pairs of attackers.

For the remainder of this report, all percentages are calculated based on the 37 attackers.

RACE/ETHNICITY

White non-Hispanic 19 51%

Black/African American 10 27%

Hispanic 5 14%

Two or more 2 5%

Undetermined 1 3%

Ages of the Attackers,

2017-2019

United States Secret Service

NATIONAL THREAT ASSESSMENT CENTER

Mass Attacks in Public Spaces - 2019 LIMITED TO OPEN SOURCE INFORMATION 13

EMPLOYMENT HISTORY

Nearly one-third of the attackers (n = 11, 30%) were known to be employed at the time of the attack, while approximately

the same percentage (n = 11, 30%) were unemployed. ose employed held a variety of positions, including two military

personnel, two fast food employees, a city engineer, a vocal instructor and delivery driver, a chiropractor, a tech support

representative, a defense auditor, a handyman, and a manufacturing assemblyman. e employment status of the

remaining 13 (35%) attackers could not be determined because of limited publicly available information.

SUBSTANCE USE

Nearly half of the attackers (n = 17, 46%) had a history of using illicit drugs (e.g., cocaine, methamphetamine, LSD,

Ecstasy) or misusing prescription medications (e.g., Xanax, Adderall, Vyvanse). For two-hs of the attackers (n = 15,

41%), the use of these substances and/or alcohol and marijuana may have reached the level of abuse causing negative

consequences in their lives, including criminal charges, academic failures, court-ordered treatment, and eviction. One

of the attackers later claimed to have no memory of his attack, alleging he had been drinking heavily at the time and had

blacked out. In this sample of attackers, a signicant relationship was observed between substance abuse and domestic

violence.

12

Ten attackers (27%) had histories of both domestic violence and substance abuse.

On August 4, 2019, a 24-year-old male fatally shot 9 and injured 20 in a popular bar district before being killed by

responding law enforcement. Friends reported the attacker regularly used amphetamines, marijuana, cocaine, and

LSD for at least ve years leading up to the attack. e attacker was found to have had Xanax and cocaine in his

system at the time of the shooting. He also had a history of assaulting women he dated.

Recent Job Loss

Seven attackers experienced, or were about to experience, a job loss prior to their attacks. Four of the unemployed

attackers experienced a job loss in the year prior to the attack. is included two attackers who quit, one attacker

whose contract ended, and one attacker who le active duty military service. Two more attackers were red

minutes or hours prior to initiating their attacks. is included one attacker who opened re immediately aer

being terminated, and another who drove through two towns fatally shooting seven and injuring approximately 25

others two hours aer his termination. Another attacker submitted his two-week notice hours before opening re

at the city municipal building where he worked.

United States Secret Service

NATIONAL THREAT ASSESSMENT CENTER

Mass Attacks in Public Spaces - 2019 LIMITED TO OPEN SOURCE INFORMATION 14

PRIOR CRIMINAL CHARGES

Half of the attackers (n = 19, 51%) had a criminal history, not including minor trac violations. All nineteen had

previously been arrested or faced charges for non-violent oenses, including drug charges, evading arrest, and reckless

driving. Nearly one-third of the attackers (n = 11, 30%) faced prior charges for violent oenses including assault, robbery,

and domestic violence. In one case, an attacker was arrested and released aer committing felony assault on a deputy sheri

one month before perpetrating his mass attack.

Some of the attackers had extensive criminal histories before reaching the age of 30. Examples included:

On July 9, 2019, a 29-year-old male used a 3.5-inch folding knife to stab three people on a downtown city street in

front of the corporate headquarters for a department store. e attacker had over 30 prior arrests. At the time of

the incident, he was under supervision in the community by the Department of Corrections, who, as early as 2017,

designated the attacker as highly violent with multiple violent oenses and likely to re-oend.

On October 5, 2019, a 24-year-old homeless man used a 15 lb. piece of scrap metal to attack other homeless men

sleeping on the streets, killing four and injuring one. e attacker had a history of at least 14 prior arrests, four of

which occurred within a year of the attack. His three most recent assault charges were dropped because the victims

stopped cooperating, and another charge was dismissed due to a technicality. At the time of the oense, the attacker

had two warrants for failure to appear in court and at a court-appointed program.

On January 29, 2019, a 29-year-old male injured four people by driving his vehicle into a homeless encampment.

e attacker had over 10 prior arrests and numerous probation violations. About two months before the attack, he

assaulted two homeless people while intoxicated and was arrested shortly aer eeing the scene in his car. He was

released on pretrial supervision aer receiving multiple charges, including DUI, driving on a suspended license, and

battery. He was later charged with a felony related to obstruction and resisting arrest. He was released back on pretrial

supervision. At the time of the attack, he had an active warrant for missing a court date ve days prior.

United States Secret Service

NATIONAL THREAT ASSESSMENT CENTER

Mass Attacks in Public Spaces - 2019 LIMITED TO OPEN SOURCE INFORMATION 15

On October 6, 2019, a 23-year-old male opened re with an accomplice inside a bar, killing four and injuring ve. e

attacker had a history of at least 10 prior arrests for various oenses, including illegally carrying a concealed weapon,

drug possession, and failure to appear for court. At the time of the attack, he had pending felony cases for possession of

a controlled substance, eeing from police, and tampering with a motor vehicle.

Several attackers engaged in criminal behavior that resulted in contact with police but did not always result in an arrest.

One attacker had over two dozen contacts with a local police department due to his involvement in disputes with his

neighbor, ghts, and driving without a license and/or insurance. In another case, an attacker had law enforcement called on

him at least four times over a period of nine months because he red shots from his residence; a report was never made for

any of the calls. Police contacted the mother of a third attacker aer her son sent another student a message saying he was

thinking of committing suicide-by-cop and taking hostages. Police were also contacted about a fourth attacker aer he told

a peer that he fantasized about slitting her throat.

HISTORY OF VIOLENCE AND DOMESTIC VIOLENCE

Nearly half of the attackers (n = 17, 46%) had a history of violence toward others, though only some of them faced criminal

charges for the behavior. irteen attackers (35%) committed prior acts of domestic violence, only seven of whom were

charged for those acts. is nding is consistent with the rates of domestic violence seen in attackers from 2017 (32%) and

2018 (30%).

On February 15, 2019, a 45-year-old male shot and killed four co-workers and injured one other, aer he was red

during a disciplinary meeting. He proceeded to chase the injured employee into an adjacent warehouse, where he

killed another co-worker. e attacker then opened re on responding police ocers before he was fatally shot by

police. Despite being the subject of a protective order by an ex-girlfriend based on allegations of stalking, the attacker

continued to harass her. is continued harassment resulted in a ne and a supplemental restraining order. He also

assaulted another ex-girlfriend, on one occasion stabbing her multiple times with a butcher’s knife in the back and

neck. For this assault, he served 3 years of a 10-year prison sentence. Both former girlfriends said he would threaten

them in order to manipulate and control them.

While a history of domestic violence does not precede every mass attack, the frequency with which these crimes are

observed should highlight for law enforcement and other public safety professionals the importance of providing

appropriate interventions in scenarios involving physical or verbal abuse directed at partners. As a reminder, federal law

prohibits the possession of a rearm by any person who:

• is subject to a court order restraining the person from harassing, stalking, or threatening an intimate partner or child

of the intimate partner; or

• has been convicted of any crime of domestic violence.

United States Secret Service

NATIONAL THREAT ASSESSMENT CENTER

Mass Attacks in Public Spaces - 2019 LIMITED TO OPEN SOURCE INFORMATION 16

* The numbers reported for the subtypes of psychotic symptoms do not equal the total number of attackers

with psychotic symptoms as attackers often had multiple types of these symptoms.

MENTAL HEALTH 2017 2018 2019

Any mental health 64% 67% 46%

Psychotic symptoms* 32% 37% 30%

Hallucinations 6 1 7

Paranoia 6 9 6

Delusions 2 5 4

Depression 14% 37% 24%

Suicidal thoughts 21% 30% 14%

MENTAL HEALTH

According to estimates from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), over half of the population in

the United States will be diagnosed with a mental health disorder at some point in their lifetime, with 20% of adults

experiencing mental health symptoms each year.

13

Of the 37 attackers in this study, at least 17 (46%) experienced mental

health symptoms prior to their attacks.

e vast majority of individuals in the United States who display the symptoms of mental illness discussed

in this section do not commit acts of crime or violence. e symptoms described in this section

constitute potential contributing factors and should not be viewed as causal explanations for the attacks.

e most common symptoms experienced by

the attackers in 2019 were psychotic symptoms

(n = 11, 30%), including hallucinations, paranoia,

and delusions. e next most common symptom

was depression, which was exhibited by one-

quarter of the attackers (n = 9, 24%). Five attackers

(14%) had a history of suicidal thoughts.

Some attackers experienced multiple types of

mental health symptoms. For example, one

attacker experienced paranoid delusions and also

experienced symptoms of depression, suicidal

thoughts, and aggression.

Psychotic Symptoms

While the percentage of attackers who experienced any mental health issue in 2019 (46%) was lower than the percentages

from 2017 (64%) and 2018 (67%), the percentage of attackers who experienced psychotic symptoms, specically, was

about the same in each year.

14

A third of the attackers (n = 11, 30%) in this study experienced these symptoms.

Compared to the rates of depression and anxiety in the general population, psychotic disorders (e.g., schizophrenia)

are relatively rare occurences. It is estimated that around 3.5% of the population experiences symptoms of psychosis.

15

In this sample, the age of onset varied, with some attackers experiencing symptoms in adolescence while others began

experiencing symptoms later in life. e types of psychotic symptoms experienced by the attackers included:

Hallucinations, or sensory perceptions that seem real but occur without any external stimulation. e most common

type of hallucination is auditory (e.g., hearing voices).

Paranoia,

16

or feelings of pervasive distrust and suspiciousness that one is being harmed, deceived, persecuted, or

exploited by others.

United States Secret Service

NATIONAL THREAT ASSESSMENT CENTER

Mass Attacks in Public Spaces - 2019 LIMITED TO OPEN SOURCE INFORMATION 17

Delusions, or false/idiosyncratic beliefs that are rmly maintained despite evidence to the contrary.

On December 28, 2019, a 37-year-old male entered a rabbi’s house, where a congregation had just nished

celebrating the last night of Hanukkah. He attacked congregants with a machete before being drawn outside and

eeing. Five congregants were injured with one eventually dying from his wounds. e attacker had a long history

of mental health issues, including a diagnosis of schizophrenia. His symptoms included paranoia and auditory

hallucinations that sometimes commanded him to take certain actions. He also displayed a number of compulsive

behaviors, such as washing his hands multiple times a day with bleach, wrapping his items in plastic, washing dollar

bills, and pouring bleach in front of car wheels.

Depression

One-quarter of the attackers (n = 9, 24%) experienced symptoms of depression prior to the attack. Symptoms of

depression included insomnia, changes in appetite, feelings of sadness, diculty concentrating, and thoughts of suicide.

While psychotic symptoms remain the most common mental health symptom observed among mass attackers in

2019, it is worth noting that the two adolescent attackers in this report who targeted K-12 schools are reported to have

experienced symptoms of depression prior to their attacks. Symptoms of depression in adolescent attackers were also

described in a previous U.S. Secret Service study, titled Protecting America’s Schools: A U.S. Secret Service Analysis of

Targeted School Violence,

17

which found that two-thirds of the student attackers exhibited some sign or symptom of

depression prior to their attacks.

On May 7, 2019, a 16-year-old student and an 18-year-old student entered a classroom in their high school, where

they fatally shot one and injured six. One of the attackers was reported to have experienced multiple symptoms

of depression, including self-harm, suicidal ideations and statements, and negative self-talk that he mistook for

command hallucinations.

Mental Health Treatment

Nearly one-third of the attackers (n = 12, 32%) were previously diagnosed with or treated for a mental health condition.

Only ve attackers with histories of mental health symptoms had no known history of diagnosis or treatment based

on open sources. e timing of when attackers were rst diagnosed or began receiving treatment ranged from early

childhood to within months of the attack.

e treatment received by the attackers varied widely and was not always sustained. e type of treatment received

ranged from counseling or medication management to involuntary hospitalization. is highlights the importance of not

only engaging those with mental health symptoms in treatment, but also ensuring that they maintain access to treatment

over time.

On August 31, 2019, a 36-year-old male opened re at pedestrians and vehicles from his car, fatally shooting 7 and

injuring 25 others. He had contacted both 911 and the FBI before his attack and claimed that there was a conspiracy

(or multiple conspiracies) to cyberstalk him, kidnap him, make him watch child pornography, and kill him. He had

a history of mental health issues, paranoia, and violent acts against himself and others, which caused him to be

institutionalized in 2001, 2006, and 2011.

United States Secret Service

NATIONAL THREAT ASSESSMENT CENTER

Mass Attacks in Public Spaces - 2019 LIMITED TO OPEN SOURCE INFORMATION 18

BELIEFS

One-quarter (n = 9, 24%) of attackers held ideological beliefs, some of which were hate-focused and associated with

violence. ese beliefs were oen multifaceted and covered a range of issues, including anti-Semitism, white supremacy,

Nazism, xenophobia, antifascism, jihadism, and anti-immigration. e prevalence of diverse ideological beliefs among

mass attackers studied by the Secret Service has remained between 24% and 30% from 2017 to 2019.

On April 27, 2019, a 19-year-old male entered a synagogue and opened re, killing one and injuring three

others. Nearly a year and a half prior to the attack, the attacker began to explore and post anti-Semitic and white

supremacist online content. His posts culminated in a seven-page manifesto where he explicitly documented his

hatred for other races, his willingness to violently ght for his beliefs, and the justications for his actions.

FIXATIONS

Seven (19%) of the attackers exhibited a xation, dened as an intense or obsessive preoccupation with a person, activity,

or belief to the point that it negatively impacted aspects of their lives. Fixations oen carried an angry or emotional

undertone and usually involved one of several themes, including ideological beliefs, an intense interest in death or

violence, preoccupation with previous mass attackers, and obsession with a previous romantic partner. Behaviors

associated with xations included stalking and/or harassment, violent verbal or online rhetoric, and writing manifestos.

ese xations were observed by others and, in some cases, extended for a number of years. One attacker was fascinated

with rearms, violence, death, and suicide-by-cop. ose who knew him were well aware of his interest. At one point,

aer telling a counselor that he dreamed of carrying out a school shooting, he was expelled from school. Other attackers

kept their xations to themselves.

On April 30, 2019, a 22-year-old male entered a university campus he had previously attended. Upon entering a

classroom, the attacker killed two students and injured four more. At least a year and a half prior to the attack, the

attacker began to watch videos of previous school attacks and specically researched the 2012 school shooting in

Newtown, CT which resulted in the deaths of 20 children and 6 sta. He spent hours a day conducting these searches.

United States Secret Service

NATIONAL THREAT ASSESSMENT CENTER

Mass Attacks in Public Spaces - 2019 LIMITED TO OPEN SOURCE INFORMATION 19

ONLINE INFLUENCE

e internet allows individuals from across the globe to virtually connect and share ideas in a profound way. is

connectedness has also allowed those with fringe or extremist ideologies to converge and promote their beliefs to a wider

audience. Some of the attackers in this study were inuenced by hateful content shared on “chan sites” and other websites.

8chan

For two of the attackers in this study, their actions were inuenced

by content they consumed online related to 8chan, an imageboard

website. An imageboard is a type of online forum where images

are posted with accompanying text that stimulate comments

and discussion. e attackers’ consumption of 8chan material

inuenced their beliefs, as both attackers described being inspired

by the actions and writings of the individual who attacked

mosques in New Zealand on March 15, 2019. ey described this

inuence in their manifestos, which were posted to 8chan prior to

their attacks.

On August 3, 2019, a 21-year-old male drove over ten

hours from his home and opened re at individuals

shopping at a large chain retail store. He specically

targeted the Hispanic community, killing 23 people and

injuring 22 others. e attacker had actively posted on

his Twitter account and on 8chan about his xenophobic

anti-immigration beliefs. In the minutes before his attack,

he posted a manifesto on 8chan in which he outlined his

political and economic reasons behind the attack, and

what he described as the “Hispanic invasion of Texas.”

He encouraged others to spread his message if his attack

was successful.

Online Misogyny

While much of the extremist rhetoric espoused online is racially or ethnically based, another concerning online community

involves men who use digital platforms to voice misogynistic views and general animosity toward women. Incels, a term

referring to those who are involuntarily celibate, are mostly heterosexual males who view themselves as undesirable to

females and therefore unable to establish romantic or sexual relationships, to which they feel entitled. ose who self-

identify as incels have gravitated toward the Internet to promote their ideology.

In this report, two attackers shared traits consistent with incel ideology, including an intense animosity toward women. For

example, one attacker oen referred to women by derogatory slurs and, while in high school, had composed a “rape list” of

girls who had turned down his advances. He also fantasized about sexual violence against women and had choked females

on multiple occasions in adolescence.

Chan Sites

e rise of 4chan and 8chan (aka Innitechan

or Innitychan), known collectively as “chan,”

has further propagated violent ideologies online.

Chan sites are largely unregulated, with few

rules and moderators to enforce them. Users

are able to post anonymously, and a formal

registration process is not required. Because

of this, it is dicult to block or remove a user

for an extended period of time.

Chan sites have allowed for the dissemination of

new extreme ideologies such as QAnon, an alt-

right movement promoting multiple government

conspiracy theories, which originated on 4chan in

2017. 8chan in particular has been linked to white

supremacy, neo-Nazism, the alt-right, racism,

anti-Semitism, hate crimes, child pornography,

and multiple mass shootings. Aer several mass

attacks in 2019 linked to this platform, it went

oine in August 2019 and was re-launched in

November 2019, rebranded as 8kun.

United States Secret Service

NATIONAL THREAT ASSESSMENT CENTER

Mass Attacks in Public Spaces - 2019 LIMITED TO OPEN SOURCE INFORMATION 20

ose tasked with assessing threats and preventing violence will benet from familiarizing themselves with the incel

movement. Special focus should be given to understanding the traits and terminology of this belief system, such as the

“manosphere,” a term for the websites and digital forums on which these views are shared. While some discussions in the

manosphere involve topics of “men’s rights” and “fathers’ rights” that sometimes dehumanize women, other discussions

attempt to legitimize violence against women outright.

Another emerging philosophy, not only within incel and manosphere forums but also within forums related to far-right or

alt-right communities, is the concept of “the red pill,” which was taken from a popular movie. e main character in that

movie is given the choice between a red pill and a blue pill. ose who take the red pill choose to wake up to the harsh truths

of reality, while those who choose the blue are shielded from the truth and remain oblivious and complacent. One attacker

in this study referenced “redpill threads” in a post about his manifesto on 8chan before he killed one and injured three more

at a synagogue.

STRESSORS WITHIN FIVE YEARS

Most of the attackers (n = 32, 87%) had at least one signicant stressor occur within the ve years leading up to the attack,

and for 30 (81%) attackers, the stressor(s) experienced occurred within one year. Some attackers experienced a persistent

pattern of life stressors that lasted several years, up to the time of their attacks. ese stressors, among others, included

signicant medical issues, turbulent home lives, and strained relationships. In addition to the criminal charges described

earlier, stressors aected dierent areas of the attackers’ lives, including:

• Family/romantic relationships, such as a break-up, divorce, physical or sexual abuse, family health issues, the death

of a loved one, or dealing with protective orders led against them by their partners.

• Social interactions, such as the ending of friendships or being bullied in school.

• Work or school issues, such as disciplinary actions, conicts with colleagues, losing a job, failing classes, or being

expelled from school.

• Contact with law enforcement or the courts that did not result in arrests or charges, such as law enforcement

responding to reports of peeping through windows, ghts, or law enforcement being called for neighbor disputes.

• Personal issues, such as evictions, homelessness, struggles with sexuality, being assaulted, or physical injury.

Financial Instability

Half of the attackers (n = 20, 54%) had a history of nancial instability within ve years of the attack. Indicators of such

instability included an inability to sustain employment, loss of income, and being evicted.

On May 29, 2019, a 65-year-old male shot three people at a plumbing company, then stole a victim’s car and ed the scene.

Aer a gun-battle with o-duty police, during which a deputy was severely injured, the attacker was found hiding under a

boat approximately one mile from the business. As ocers approached, the attacker shot and killed himself. Years prior, the

attacker fought the city over property he owned that was to be condemned. Unable to aord the costs involved, the attacker

ultimately lost the property. In 2009, when the owners of the plumbing company purchased the lot behind their store, they

allowed the attacker to live there for free on the condition that he kept it clean. He stayed there in a van or small shed, and

the owner would oen bring him food and water. To make money, the attacker sold water heaters and scrap metal and

over time the property became lled with vehicles, barrels, and debris. When asked to keep the property clean, the attacker

refused. ree months before the attack, the owner secured an eviction in court, but he delayed the notication. e

attacker was served with eviction papers by the sheri’s department around 48 hours before beginning his attack.

United States Secret Service

NATIONAL THREAT ASSESSMENT CENTER

Mass Attacks in Public Spaces - 2019 LIMITED TO OPEN SOURCE INFORMATION 21

Home Life Factors

Many of the attackers had a history of negative home life factors. For about one-quarter (n = 9, 24%) of them, this included

some form of adverse childhood experience, such as the death of a parent; suering abuse; or exposure to alcoholism, drug

addiction, or domestic violence. Fieen of the attackers (41%) had an unstable home life at the time of the attack. is was

evidenced by evictions, homelessness, the absence of a parental gure, and a parent struggling with mental health symptoms.

Seven of the attackers were homeless at the time of the attack, and two more had received a second or third notice regarding

an impending or possible eviction.

On January 23, 2019, a 21-year-old male entered a bank, made the ve women inside lie facedown on the oor, and

fatally shot each one. He then called 911 and stated that he had shot ve people. e attacker was taken into custody

aer a nearly two-hour stando with police. e attacker had experienced several negative home life factors growing up.

His parents divorced when he was young and his father remarried and divorced again during the attacker’s childhood.

Both parents had signicant nancial issues with liens, foreclosures, and court judgments against them. His father had

a number of criminal charges and was at one point delinquent in his child support to two dierent women. According to

friends from high school, the attacker had a dicult relationship with his father, and his mother did not take his mental

health problems seriously.

Triggering Event

Ten (27%) of the attackers appeared to experience a triggering event prior to perpetrating an attack. is included having

their rent increased, being evicted, being kicked out of a business, and being red from a job. For eight (22%) of these

attackers, the triggering event appeared directly related to who they targeted or where they perpetrated the attack. For the

remaining attackers, one attacked random individuals unrelated to his workplace aer he was red, and the other attacked

former coworkers aer a judge issued a second eviction notice.

On October 3, 2019, a 64-year-old male opened re at a cemetery where he formerly worked, killing one and injuring

two others. He had threatened his apartment’s management and le multiple incendiary devices at or near his

residence. e attacker, who had a history of concerning behaviors, was red seven years prior and sought revenge

against his former employer due to the subsequent nancial hardships he faced. e attack appeared to be triggered by

his eviction from his apartment.

THREATS AND OTHER CONCERNING COMMUNICATIONS

Two-thirds of the attackers (n = 24, 65%) engaged in prior threatening or concerning communications. Many had

threatened someone (n = 16, 43%), including threats against the target in eight cases (22%). e attackers who made

threats against someone they later targeted ranged from those who threatened a specic individual (e.g., a co-worker)

to those who threatened an entire group (e.g., Jewish people, the homeless).

On August 4, 2019, a 24-year-old male opened re in a busy nightclub district, killing 9 (including his sibling) and injuring

20 before ocers shot and killed him. e attacker had a history of concerning communications, including harassing

female students in middle and high school, making a hit list and a rape list in high school, telling others he had attempted

suicide, and showing footage of a mass shooting to his girlfriend. Months before the attack, he went to bars and would tell

his friends that he could have “done some damage” there.

United States Secret Service

NATIONAL THREAT ASSESSMENT CENTER

Mass Attacks in Public Spaces - 2019 LIMITED TO OPEN SOURCE INFORMATION 22

Over half of the attackers (n = 21, 57%) made some type of

communication, in the form of written, visual, verbal, or online

statements, that was not a threat but should have elicited concern in

others. ese concerning communications included making paranoid

statements, sharing videos of previous mass attacks, vague statements

about their imminent death, and one attacker telling his school counselor

that he had a dream about killing his classmates.

BEHAVIORAL CHANGES

Two-hs of the attackers (n = 15, 41%) exhibited changes in behavior that

were observable to others, including new or increased substance use, feelings

of depression, isolating from family and friends, engaging in self-harm,

spontaneously quitting a job or withdrawing from school, and changes in

appearance. ese changes in behavior were observed by family members,

friends, and co-workers. In seven of these cases, the behavior changes

occurred within a year of the attack.

On October 5, 2019, a 24-year-old homeless man used a 15 lb. piece of scrap metal to attack other homeless men

sleeping on the streets, killing four and injuring one. He had exhibited behavioral changes as far back as ve years,

and as recently as the day prior to the attack. In 2014, his family noted that he became depressed and started using

drugs, aer which he became paranoid, violent, and lost his job in construction. Over time, he stopped living with his

mother and began staying in shelters and living on the streets. More recently, not only did his family note that he was

further deteriorating mentally, but neighbors for whom he performed odd jobs also noted some changes. e attacker

spoke to them about feeling stressed, and then suddenly stopped coming by. e day before the attack, a neighbor who

saw him lying in a stairwell of his mother’s building noted that he looked more withdrawn than usual, just laid there,

and avoided eye contact. She would later state that he just seemed dierent, not normal, and that when she saw his

eyes, it seemed like he was not there.

Although a behavioral change does not indicate someone is planning a mass attack, it does provide a window of

opportunity to engage with that individual, gather insight into why that behavior change occurred, and identify

appropriate responses.

Social Media Use

Half (n = 18, 49%) of the attackers had at

least one identied social media account

where they posted, shared, or liked

content, including accounts on Facebook,

Twitter, Instagram, LinkedIn, Snapchat,

MySpace, YouTube, and SoundCloud.

e volume of activity seen on social

media ranged from low to high among

the attackers. Some of the online content

included typical behavior, such as

sharing photos of family. Other content

included information about suicidal

ideations, drug use, violence, hate toward

a particular ethnic group, and previous

mass shootings.

United States Secret Service

NATIONAL THREAT ASSESSMENT CENTER

Mass Attacks in Public Spaces - 2019 LIMITED TO OPEN SOURCE INFORMATION 23

SOCIAL ISOLATION

Nearly one-third (n = 11, 30%) of the attackers self-identied or

were described by others as withdrawn, loners, or anti-social.

For some, these behaviors were noted by those who knew them

from an early age. For others, the behaviors were observed during

their school or college years, at their places of work, or in their

neighborhoods. Attackers were classied as socially isolated for

behaviors that went beyond simply not having many friends or

choosing not to participate in various social activities. Rather, they

were considered socially isolated for a range of behaviors, from

consistently showing a clear discomfort around others in dierent

contexts or ignoring social cues, to more overt behaviors like

actively or physically avoiding contact with others. Many attackers

studied by the Secret Service over the previous three years have

displayed these types of socially isolating behaviors.

ISOLATING BEHAVIORS: On May 31, 2019, a 40-year-old male opened re at a city municipal center, killing

12 and injuring 5, before he was killed by police. e attacker had given his two-week notice earlier in the day and

was reportedly distressed in the days leading up to the attack. ough the attacker appeared to have been social in

his youth, he was more isolated in the last decade of his life. At work, he would keep his oce door closed and was

described as private, shy, and reserved. One co-worker noted that he was selective about with whom he would speak.

He rarely attended work events, and when he did, he kept to himself. Estranged from his biological father’s side of the

family for many years, relatives noted that he could be “paranoid, introverted, and uncomfortable around people.”

ough some neighbors said he seemed nice, others noted he never smiled at them and they rarely saw him outside of

his residence.

PHYSICAL AVOIDANCE:

On July 28, 2019, a 19-year-old male opened re at a local community festival, killing 3

and injuring 17 others. Less than one minute aer he began ring, police confronted him and shot him multiple times

before he fatally shot himself in the head. Students and teachers from his high school, who were interviewed aer the

attack, noted that he did not make much of an impression at the school. ree months prior to the attack, he moved

to a small town and had very little contact with others. At one point, he moved into an unfurnished triplex with few

belongings and paid three months’ rent in cash. Speaking of his tenants, the property manager said, “I don’t think

anybody knows anybody [at this property] because they’re there to get away from everybody else.” Residents would

later report that they noticed his presence as a new person in the sparsely populated area, but they seldom saw him.

One neighbor said he saw the attacker walk to the mailbox and occasionally leave his apartment, but never spoke to

him or even heard his voice.

Social Isolation

United States Secret Service

NATIONAL THREAT ASSESSMENT CENTER

Mass Attacks in Public Spaces - 2019 LIMITED TO OPEN SOURCE INFORMATION 24

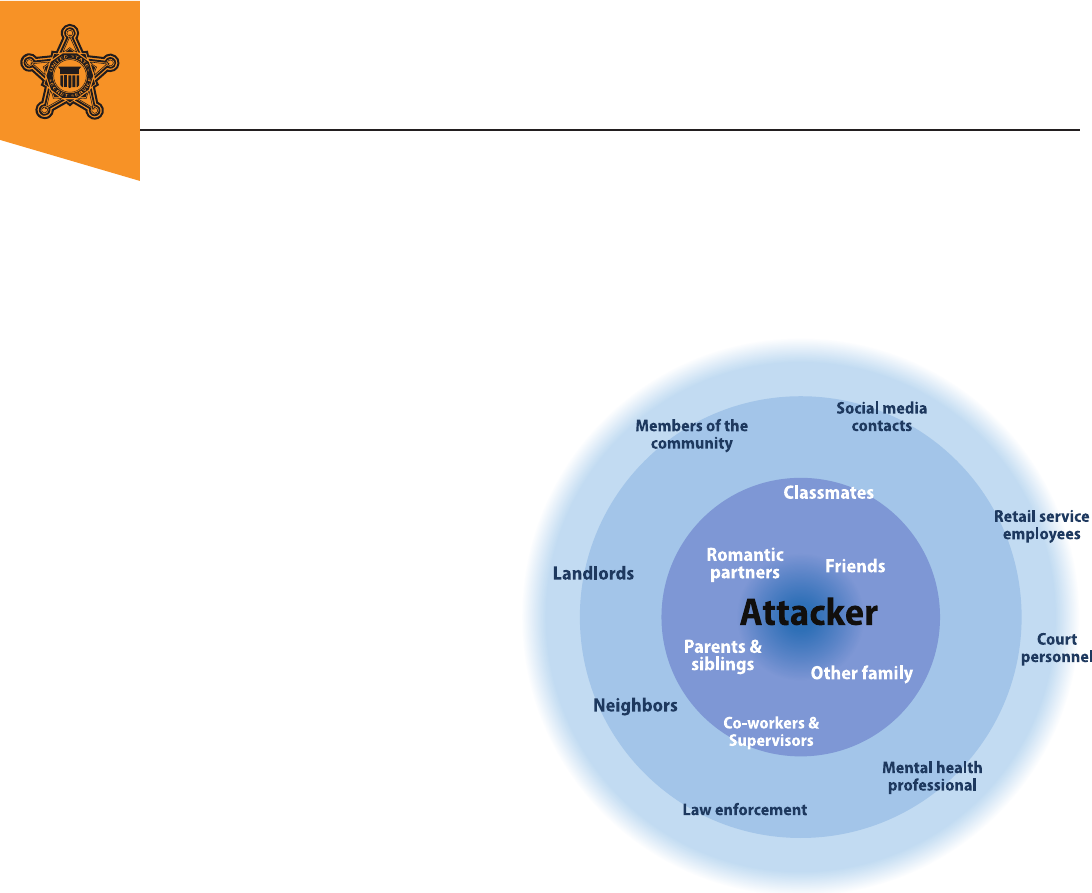

ELICITED CONCERN

Two-thirds of the attackers (n = 24, 65%) in this report

exhibited behaviors that elicited concern in other people.

ose who were concerned had various degrees of

association with the attackers, from those with whom the

attacker was close (e.g., family and friends) to those with

whom they had infrequent or peripheral contact. Most

oen, the attackers elicited concern from multiple people

in their lives. For over half of the attackers (n = 21, 57%),

the behaviors they engaged in concerned others to the

point that the observer feared for the safety of themselves

or others.

e behaviors that elicited concern in others varied

across the attackers. ey included:

• Expressions of homicidal/suicidal ideations

• Domestic violence

• Social media posts with concerning content

• reatening statements toward others

• Weapons purchases

• Harassing or stalking behaviors

• Bizarre/incoherent behavior

• Non-compliance with mental health medication

• Signs of depression

• Increased isolation

• Acts of self-harm

• Poor school attendance

• No longer paying bills

Concerned bystanders oered a variety of responses to these behaviors, from avoiding the attacker to voicing their concern

to others. Some bystanders engaged in more overt eorts to seek help, like transporting the attacker for a mental health

evaluation. Other responses included:

• Romantic partners ling for protective orders, getting a divorce, or otherwise ending the relationship;

• Parents seeking therapy for the attacker, reminding them to take prescribed mental health treatment, requiring them

to move out of the house, or calling law enforcement;

• Colleagues avoiding the attacker, ring them, or confronting them with their concerns;

• Fellow students telling school sta about their concerns, reporting the behavior to a designated central reporting

mechanism, or speaking with the attacker about their concerns;

• School personnel notifying parents about their concern or expelling the attacker from school.

United States Secret Service

NATIONAL THREAT ASSESSMENT CENTER

Mass Attacks in Public Spaces - 2019 LIMITED TO OPEN SOURCE INFORMATION 25

CONCLUSION

Tragically, many communities across the country were impacted by mass violence in 2019. All available data indicates

that these acts of violence are rarely spontaneous and are almost always preceded by warning signs, thereby oering

opportunities for prevention. e U.S. Secret Service stands ready to support our community partners in this vital public

safety mission, with the same eort we dedicate to our no-fail mission of protecting the nation’s highest elected ocials.

ese tragedies are preventable if the appropriate community systems are in place. is report supports the Secret

Service’s long-standing recommendation that multidisciplinary threat assessment programs should be part of any violence

prevention plan. A threat assessment is designed to identify and intervene with individuals who pose a risk of engaging in

targeted violence, regardless of motive, target, or weapon used.

is approach requires an enhanced understanding and awareness of the types of behaviors that tend to precede acts

of violence. NTAC’s research into mass attacks has demonstrated that no two attacks or attackers are exactly alike. For

example, all of the mass attacks that occurred in 2017 or 2018 were carried out by lone attackers, while this year’s analysis

included three attacks that were carried out by pairs of attackers. However, NTAC continues to identify commonalities

that frequently appear in attackers’ backgrounds and provide public safety ocials an opportunity for intervention.

For example, this study identied a signicant relationship between substance abuse and domestic violence in the

histories of the 37 attackers, two areas deserving of enhanced community resources. While a history of drug abuse or

domestic violence does not precede every mass attack, the frequency with which these factors are observed highlights the

importance of providing appropriate interventions in these situations.

e ndings from this report reinforced similar ndings from previous NTAC studies on mass attacks, including the

prevalence of ideological beliefs, grievance-based motives, and a history of violence, among others factors. is year’s study

expands on these ndings by examining additional factors, such as home life and current living situations, behavioral

changes, social isolation, employment status, and online activity. During the analysis of these 34 attacks from 2019,

NTAC researchers identied key ndings that should immediately inuence the violence prevention strategies used by

communities across the United States. ese ndings include:

• e attacks impacted a variety of locations, including businesses/workplaces, schools, houses of worship, military

bases, open spaces, residential complexes, and transportation.

• Most of the attackers used rearms, and many of those rearms were possessed illegally at the time of the attack.

• Many attackers had experienced negative home life factors, unemployment, substance use, mental health symptoms,

• or recent stressful events.

• Attackers oen had a history of prior criminal charges or arrests and domestic violence.

• Most of the attackers had exhibited behavior that elicited concern in family members, friends, neighbors, classmates,

co-workers, and others, and in many cases, those individuals feared for the safety of themselves or others.

United States Secret Service

NATIONAL THREAT ASSESSMENT CENTER

Mass Attacks in Public Spaces - 2019 LIMITED TO OPEN SOURCE INFORMATION 26

In order to address each of these key ndings, the U.S. Secret Service oers the following for consideration:

ESTABLISH THREAT ASSESSMENT PROGRAMS: e attacks examined in this report aected the places where we work,

learn, and otherwise live our daily lives. reat assessment teams can be established in many of these environments, with

the goal of identifying and intervening with individuals who may pose a risk of harm to themselves or others. Police

departments, workplaces, military installations, government agencies, universities, and K-12 schools can implement these

types of programs as part of an overall violence prevention strategy.

For the past 20 years, the U.S. Secret Service has provided guidance on the establishment of threat assessment programs

to law enforcement, schools, government agencies, and others, beginning with the publication of the agency’s rst

threat assessment guide, Protective Intelligence & reat Assessment Investigations: A Guide for State and Local Law

Enforcement Ocials. e North Carolina State Bureau of Investigation’s Behavioral reat Assessment (BeTA) Unit

18

is an

example of a state law enforcement agency using a proactive approach to prevent violence in the community, by intervening

with those individuals identied as having the means and motive to perpetrate an act of targeted violence. Similarly, the U.S.

Department of Veterans Aairs operates a Workplace Violence Prevention Program (WVPP),

19

which incorporates threat

assessment and management practices as part of a robust workplace safety plan.

More recently, the Secret Service published updated guidance for K-12 violence prevention programs, titled Enhancing

School Safety Using a reat Assessment Model: An Operational Guide for Preventing Targeted School Violence. ese

types of programs operate in many schools across the country and regularly facilitate students receiving counseling services

or other interventions when they are in crisis.

ENFORCE EXISTING FIREARMS LAWS: e majority of mass attacks in the United States are carried out using rearms. In

each of the past three years, the Secret Service found that at least 40% of these shootings in public spaces involved a rearm

that was illegally possessed at the time. Federal law establishes several prohibiting factors that make it unlawful for an

individual to purchase or possess a rearm. ese factors include a prior felony conviction, a dishonorable discharge from

the military, and being the subject of a current restraining order. Other noteworthy prohibiting factors include illegal drug

use within the past year and any prior conviction for a crime of domestic violence. All law enforcement and other public

safety ocials must be aware of these longstanding federal restrictions, as well as any additional state or local restrictions,

and take steps to ensure these laws are enforced.

PROVIDE CRISIS INTERVENTION, DRUG TREATMENT, AND MENTAL HEALTH TREATMENT: Many attacks in 2019 were

perpetrated by individuals who had experienced unemployment, substance use, mental health symptoms, and/or recent

stressors. While there is no sure way to predict human behavior or attribute violence to a single cause, early intervention

is a demonstrated best practice for preventing unwanted behavior. Providing resources to address factors like drug abuse,

mental illness, unemployment, and other personal crises is of utmost importance at the community level. Workplaces,

schools, and communities at large should provide support for individuals experiencing these types of distress. For example,

many universities operate behavioral intervention teams to promote well-being within the campus community. ese cross-

campus groups collaboratively facilitate access to mental health and substance abuse treatment, nancial and academic

supports, and other necessary resources for members of the campus community. Early intervention not only improves the