JOURNALISTS IN THE UK

Neil Thurman, Alessio Cornia, and Jessica Kunert

RISJ Report | Journalists in the UK Neil Thurman, Alessio Cornia, and Jessica Kunert

PART OF THE WORLDS OF JOURNALISM STUDY

NEIL THURMAN, ALESSIO CORNIA, AND JESSICA KUNERT

SUPPORTED BY

JOURNALISTS

IN THE UK

© 2016 Reuter

s Institute for the Study of Journalism

DOI: 10.60625/risj-83nm-gr64

...............................................................................................................................................................................................

Foreword …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………5

About the Authors

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………6

Acknowledgements

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………6

Executive Summary

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………7

...............................................................................................................................................................................................

1. Personal Characteristics and Diversity ………………………………………………………………………………………………… 9

Neil Thurman

2. Employment Conditions

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 15

Neil Thurman

3. Working Routines

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 24

Neil Thurman

4. Journalists’ Role in Society

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 30

Jessica Kunert and Neil Thurman

5. Journalism and Change

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 35

Neil Thurman

6. Influences on Journalists’ Work

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 41

Alessio Cornia and Neil Thurman

7. Journalists’ Trust in Institutions

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 47

Jessica Kunert and Neil Thurman

8. Ethics and Standards

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 51

Alessio Cornia and Neil Thurman

9. Methodology

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 56

Neil Thurman

...............................................................................................................................................................................................

References ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 60

...............................................................................................................................................................................................

4 4REUTERS INSTITUTE FOR THE STUDY OF JOURNALISM / JOURNALISTS IN THE UK

Journalism plays a pivotal role in keeping us informed and

critically aware. But in a period when digital communications

technologies are violently disrupting news industry business

models there is confusion and debate as to whether the

result is less journalism, worse journalism or more and better

journalism delivered through a more diverse array of media,

including social media.

Given the importance of journalism and the current fluidity of

the industry’s commercial circumstances, it is very good to have

an up-to-date insight into what journalists themselves have to

say about some of these matters.

Building upon the work of a previous UK survey in 2012 and

in collaboration with the global Worlds of Journalism project

designed to produce comparative data on journalists’ opinions

and attitudes, this Reuters Institute report illuminates essential

ground. It is based upon a survey of 700 of the UK’s almost

64,000 professional journalists.

Some of its conclusions are familiar but still stark: the chronic

failure to achieve even reasonable levels of ethnic diversity

in journalism; and the very strong flow of women into the

profession – they form a majority among young journalists but

are still very much a minority in the senior ranks.

Particularly fascinating are the journalists’ answers on ethical

issues, which emerge as mostly in line with ocial codes of

practice. Journalists say that their behaviour is aected more

than anything else by ethical guidelines and professional codes

of practice. This suggests that the Leveson era may have

made more impact than is generally acknowledged. Since a

majority of journalists also believe that their profession has lost

credibility over time, it might even indicate the start of a fight-

back.

Pleasing also, to me at least, is the historically rooted hierarchy

of values which emerges from the journalists questioned. At the

very summit, they place first the provision of reliable information

and, second, holding power to account. In third place comes

entertainment, which I also interpret positively: dull reporting,

pedestrian writing and predictable analysis undermine the first

two values.

Journalists, the data show, continue to be better and better

educated, but for most of them pay remains relatively modest.

The best paid jobs are still in television, where disruptive forces

bearing on news are weaker.

The proportion of journalists working in newspapers has fallen

sharply, but disagreement about definitions makes it unsettled

whether overall in the digital age we have more or less

journalism and more or fewer journalists. The authors estimate

that there are now 30,000 journalists working wholly or partly

online, but many bloggers are excluded from this count, along

with others whose journalistic identity is complex.

Digital influences also mean that journalists have more data

about audience responses to their work; it remains unclear to

what extent they feel bullied by this into the clickbait game,

rather than feeling that they can use the data to make better,

independent decisions about how to provide a service the

audience values.

For me, the overall impression delivered by the survey is

positive. In spite of the most turbulent period of change in

the news industry for a century, there is a read-out here of

core purpose and conviction among British journalists. As

business models start to settle down in the third decade of the

internet and new types of proprietor establish themselves, this

persuades me that the outlook is more promising than is often

suggested.

FOREWORD

Ian Hargreaves

Professor of Digital Economy, Cardi University

Former Editor, the Independent; Deputy Editor, the Financial Times;

Editor, The New Statesman; and Director BBC News and Current Aairs

4 4 5/

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Dr Neil Thurman is a Professor of Communication with an emphasis on computational journalism in the Department of Communication

Studies and Media Research, LMU Munich. He is a VolkswagenStiftung Freigeist Fellow.

Dr Alessio Cornia is a Research Fellow at the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, University of Oxford.

Dr Jessica Kunert is a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Communication Studies and Media Research, LMU Munich.

The authors would like to thank Mike Bromley, Sophie Cubbin, Richard Fletcher, Ed Grover, Thomas Hanitzsch, John Hobart, David Levy,

Corinna Lauerer, Rasmus Kleis Nielsen, Alex Reid, Jane Robson, Nina Steindl, and the whole Worlds of Journalism Study team.

Proposals for collaboration on further publications based on this survey data should be directed to Dr Neil Thurman <neil.thurman@iw.

lmu.de>.

6REUTERS INSTITUTE FOR THE STUDY OF JOURNALISM / JOURNALISTS IN THE UK

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

This report is based on a survey conducted in December 2015

with a representative sample of 700 UK journalists. Our analysis

of the survey data and of over a hundred other relevant sources

of information has produced numerous findings.

On UK journalists’ personal characteristics and diversity:

• Although women make up a relatively high proportion of the

profession, they are less well remunerated than men and

are under-represented in senior positions.

• Journalism is now fully ‘academised’. Of those journalists

who began their careers in 2013, 2014, and 2015, 98% have

a bachelor’s degree and 36% a master’s. While this trend is

helping to correct historical gender imbalances, it may have

other, undesirable, consequences for the socio-economic

diversity of the profession.

• Journalists are less religious than the general population

and a smaller proportion claim membership of the Muslim,

Hindu, and Christian faiths.

• UK journalism has a significant diversity problem in terms of

ethnicity, with black Britons, for example, under-represented

by a factor of more than ten.

• About half of journalists take a left-of-centre political stance,

with the remaining half split between the centre and the

right-wing. Right-of-centre political beliefs increase with rank.

On UK journalists’ employment conditions:

• 20% of journalists have gross yearly earnings of less than

£19,200, likely to be at or below the ‘living wage’ for many.

• 83% of journalists in their mid to late twenties earn less than

£29,000, an income that makes getting on the property

ladder a significant challenge.

• 27% of journalists engage in other paid work.

• Most journalists (54%) work in a single medium (TV, radio,

print, or online) and working across multiple media provides

no clear financial benefit.

• A third of journalists working for UK ‘national’ newspapers

now consider their outlet’s reach to be transnational.

On UK journalists’ working routines:

• Since 2012 the proportion of journalists in the UK working

in newspapers has fallen from 56% to 44%, while the

proportion working online has risen from 26% to 52%.

• We estimate there are now 30,000 journalists in the UK

who work wholly or partly online. However, those working

exclusively online are less well paid than journalists who

work only in newspapers.

• 53% of journalists are specialists, with the most populous

beats being business, culture, sport, and entertainment.

There are few politics, science, or religious specialists.

• UK journalists typically produce or process ten news items

a week, although that number doubles for journalists who

work exclusively online.

On UK journalists’ role in society:

• Journalists most commonly believe that their role is to

provide accurate information, to hold power to account,

and to entertain. However, few see importance in roles

that are more directly connected with politics, like being an

adversary of the government.

• Radio journalists, rather than journalists working online, feel

most strongly that their role should include letting people

express their views.

• 45% of UK journalists see it as very or extremely important

to provide news that attracts the largest audience, a higher

proportion than was found in a US survey in 2008–9.

On journalism and change:

• Twice as many UK journalists believe that their freedom to

make editorial decisions has decreased over time as believe

it has increased. We argue this could be a result of the

increasing influence of audience research and pressure to

‘keep up with the competition’, with negative consequences

for the diversity of news output.

• A large majority believe time for researching stories has

decreased and the influence of profit-making pressures, PR

activity, and advertising considerations has strengthened.

6 7/

• Most UK journalists believe their profession has lost

credibility over time.

• UK journalists overwhelmingly believe that the importance

of technical skills and the influence of social media

platforms have increased over time.

On influences on journalists’ work:

• UK journalists believe that ethics, media laws and

regulation, editorial policy, their editorial supervisors, and

practical limitations exercise the greatest influence over

their work.

• Although UK journalists ascribe little influence to state

ocials, politicians, pressure groups, business people, and

PR, a large majority acknowledge the influence of news

sources; and the most frequently cited sources in news

stories are representatives of these very groups.

• Most journalists think that owners, advertising

considerations, and profit expectations have little influence

over their work, although these sources of influence are

rarely experienced directly but rather through organisational

constraints.

On UK journalists’ trust in institutions:

• Contrary to stereotype, UK journalists appear to be more

trusting in general terms, and no less trusting of politicians

and government, than the general population.

• UK journalists show more trust in the judiciary and the

courts than they do in their own profession, the news media.

• Journalists have less trust in religious leaders and trade

unions than they do in Parliament, the police, and the

military, in part, we argue, because of their reliance on these

latter institutions as sources of information.

On ethics and standards:

• There is close correspondence between UK journalists’

views on ethics and their professional codes of practice.

However, they are more likely to find justification for

ethically contentious practices, such as paying sources, than

journalists in the United States.

• Rank and file journalists in the UK push ethical boundaries

more than their managers, and 25% of all journalists believe

it is justified, on occasion, to publish unverified information.

8 8REUTERS INSTITUTE FOR THE STUDY OF JOURNALISM / JOURNALISTS IN THE UK

PERSONAL

CHARACTERISTICS

AND DIVERSITY

NEIL THURMAN

Our survey gathered a range of information on UK journalists’

personal characteristics. Basic data on the age spread and

gender balance of our sample is reported in Section 9. Here in

Section 1 we focus in detail on the dierences between male

and female journalists in employment status, income, rank, and

editorial freedom; and how the proportions of men and women

entering the profession are changing. This section also reports

on journalists’

• education;

• religious aliation and depth of belief;

• ethnicity; and

• political aliation.

In addition, our survey asked journalists about the length of

time they had spent working in the profession. We have used

this data in various ways in this study, for example to find out

from those who have been in the profession for at least five

years how they feel journalism has changed over time (see

Section 5). For the record, the journalists who completed our

survey had between one and 54 years of work experience, with

an average of 18.5 years. About a quarter had less than ten

years’ work experience.

1.1 GENDER

Our results show that 45% of UK journalists are women, a

similar figure to that found in other surveys (see Section

9.5). This figure is relatively high compared with some other

professions. For example, only 31% of practising barristers (Bar

Standards Board, 2014) and 33% of medical consultants (GMC,

2015) are female. It does not, however, tell the whole story. We

also need to look at the levels of influence and recognition that

women in journalism have.

Starting with employment status, we see that according to

our survey women are slightly more likely to be employed on

part-time or freelance contracts than men. However, women

and men who are regular employees rather than freelancers

are almost exactly as likely as each other to be on a permanent

rather than a temporary contract: 96% of men against 98% of

women (see Figure 1.1a).

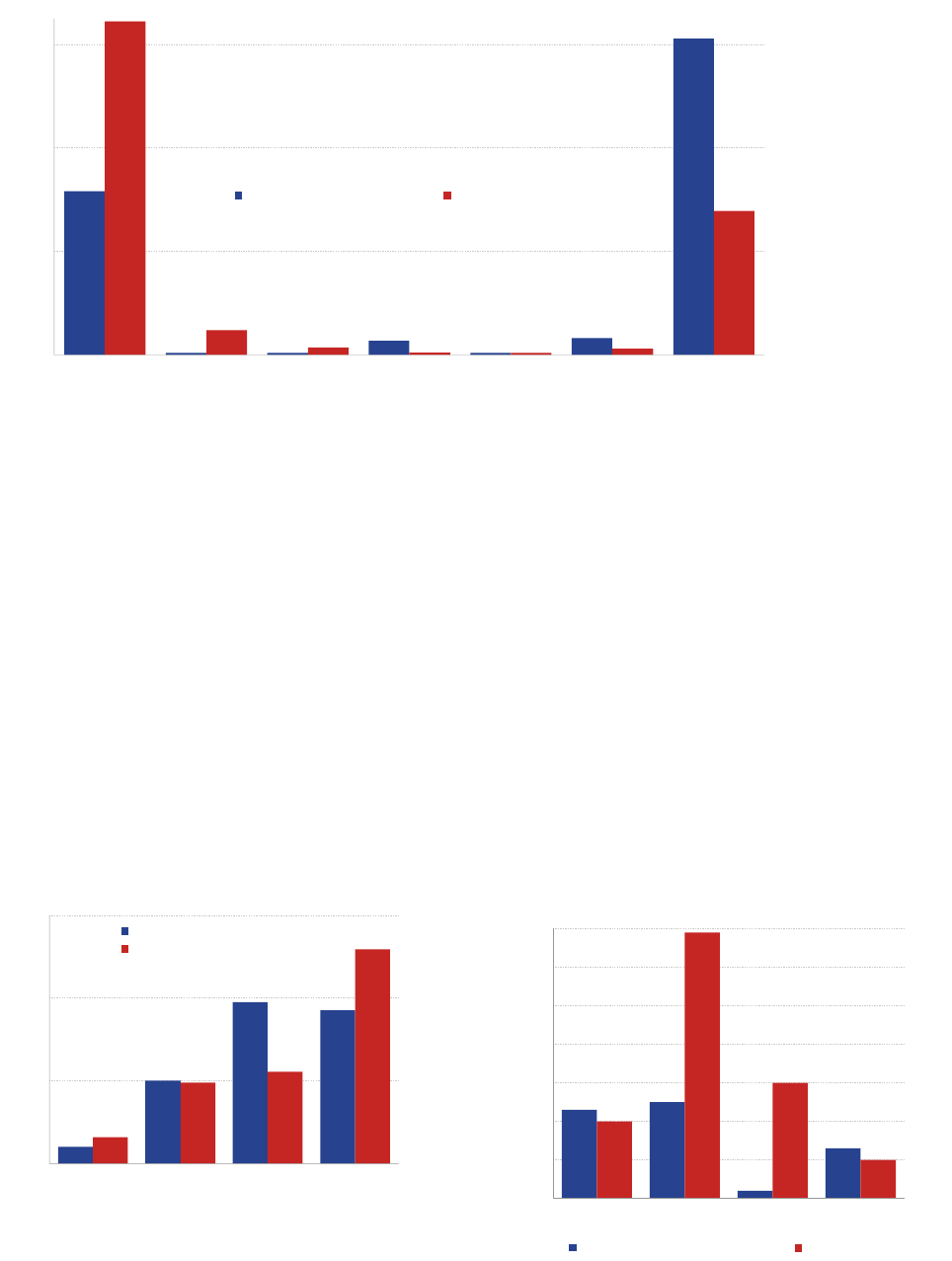

FIGURE 1.1a: EMPLOYMENT STATUS OF MALE

AND FEMALE JOURNALISTS IN THE UK,

DECEMBER 2015.

Figure 1.1a:

E

mployment status of

m

ale and female

j

ournalists in the UK,

D

ecember 2015.

70%

77%

9%

5%

18%

16%

2%

3%

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

Women (n = 314) Men (n = 381)

Other

Freelance

Part-time

Full-time

To compare income across the sexes we focused on full-time

employees only, and excluded journalists who also worked in

other paid activities at the same time. The results show that a

significantly higher proportion of women journalists earn less

than £2,401/month. About half of women are in this salary band

compared with a third of men. Although the same proportion of

male and female journalists earn between £2,401 and £4,000/

month, men are considerably more likely to have a salary of

over £4,000/month (see Figure 1.1b overleaf). We can clearly

see then that the salaries of full-time female journalists are

weighted towards the bottom of the salary scale, whereas

men’s salaries are more evenly spread across the full spectrum

of earnings.

1

1

It should be noted that the female journalists in our sample were, on average, five years younger than their male colleagues which is likely to explain some, but not

all, of this income disparity.

8 9/ 8

This fi nding chimed with one young, female journalist working

at a national news publication who completed our survey.

She told us that ‘there are a few men who do the same job

as me and are paid considerably more despite having less

experience’. In her view one of the barriers to equal pay was

a lack of transparency: ‘you don’t know how big the gap is

because there’s huge secrecy around how much everyone is

paid’ (personal communication, 23 February 2016).

FIGURE 1.1b: GROSS MONTHLY SALARIES OF

FULL-TIME MALE AND FEMALE JOURNALISTS

IN THE UK, DECEMBER 2015 (n = 411).

50%

34%

29%

31%

22%

36%

0%

20%

40%

60%

Women Men

<=£2,400 £2,401–£4,000 >£4,001

Notes: Journalists who said they also worked in other paid activities outside

journalism were excluded. The average age of female journalists in our survey was

40 against 45 for men. This age difference is likely to explain some, but not all, of

the income disparity between the sexes.

Figure 1.1b: Gross

m

onthly salaries of

f

ull-time male and

f

emale journalists

i

n the UK,

D

ecember 2015 (

n

= 411).

Notes: Journalists who said they also worked in other paid activities outside

journalism were excluded. The average age of female journalists in our

survey was 40 against 45 for men. This age di erence is likely to explain

some, but not all, of the income disparity between the sexes.

On the question of seniority, our survey shows that although

similar proportions of men and women work as rank and fi le

journalists, women appear to get stuck in junior management

roles, whereas men are more likely to progress into senior

management (see Figure 1.1c). The female journalist we

spoke to felt that part of the explanation was the way existing

structures were inclined to replicate themselves: ‘there is a

tendency for senior management to be predominantly male

and for them to promote men as well’ (personal communication,

23 February 2016).

In addition to rank, our survey provided us with other ways of

measuring di erences in the relative levels of infl uence wielded

by the sexes. We asked journalists how much freedom they

had in selecting news stories, in deciding which aspects of a

story should be emphasised, and how often they participated

in editorial meetings and newsroom coordination. There was

no di erence in the frequency with which men and women

felt that they participated in editorial coordination, for example

attending editorial meetings or assigning reporters. However,

men said that they had a little more freedom both in selecting

news stories and in deciding which aspects of a story to

emphasise (see Figure 1.1d).

FIGURE 1.1d: COMPARATIVE FREEDOM

OF MALE AND FEMALE JOURNALISTS IN

THE UK IN EDITORIAL DECISION-MAKING,

DECEMBER 2015.

Figure 1.1d:

Comparative

freedom of male

and female

journalists in the

UK in editorial

decision-making,

December 2015.

69%

74%

52%

75%

81%

53%

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

Have 'complete' or

'a great deal' of

freedom in selecting

news stories (n = 689)

Have 'complete' or

'a great deal' of freedom

in deciding which aspects

of story should be

emphasised (n = 689)

Participate in editorial

coordination 'always' or

'very often' (n = 691)

Women

Men

Note: Journalists at the start and end of their careers are not shown because those with less than 6 years professional experience are unlikely to have had

signifi cant opportunities for promotion and those with more than 29 years are more likely to be working part-time and in a freelance capacity (see section 2.5).

23%

30%

37%

41%

39%

41%

36%

31%

21%

0%

20%

40%

60%

6–10 (n = 44) 11–20 (n = 110) 21–29 (n = 70)

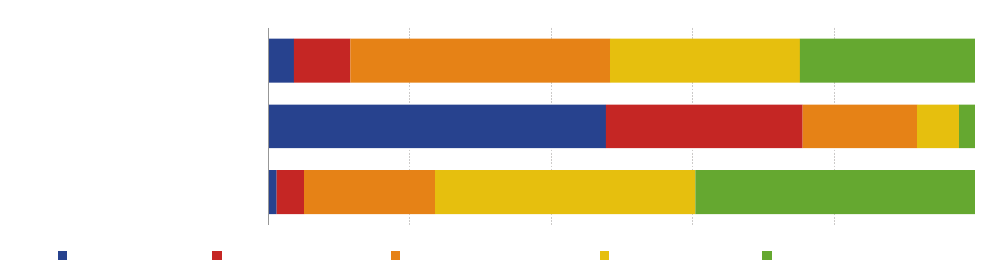

Figure 1.1c: Rank of male and female journalists in the UK by years of professional

e

xperience, December 2015.

17%

21%

18%

35%

50%

55%

48%

29%

28%

0%

20%

40%

60%

6–10 (n = 56) 11–20 (n = 94) 21–29 (n = 51)

Senior managers Junior managers Rank and file journalists

Women

Men

Note: Journalists at the start and end of their careers are not shown because those with less than 6 years professional experience are unlikely to have had

significant opportunities for promotion and those with more than 29 years are more likely to be working part-time and in a freelance capacity (see section 2.5).

FIGURE 1.1c: RANK OF MALE AND FEMALE JOURNALISTS IN THE UK BY YEARS OF

PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE, DECEMBER 2015.

10

REUTERS INSTITUTE FOR THE STUDY OF JOURNALISM / JOURNALISTS IN THE UK

Our survey provides very limited data about any dierences

between the sexes in terms of the ‘beats’ or subject areas they

cover. This is because only about half of our respondents say

they specialise in a particular beat. If we look at the specialisms

of those who do, all we can say with any certainty is that a

lot more men cover sport than women: by a factor of about

ten. Analysing the relative proportions of men and women at

outlets with dierent geographic markets shows that gender

diversity is worse at news organisations that are ‘local’ and

‘transnational’ in reach but better at those targeted at ‘regional’

and ‘national’ audiences.

So far our survey has painted a mixed picture of equality in

influence and recognition for female journalists in the UK.

Whilst men and women are approaching equality in security

of employment and in their autonomy at work, women are

paid less and are less likely to progress to senior levels

of management. What then of the future? Are there any

indications in our data that women will be better represented in

senior positions in times to come? While it does not follow that

having at least as many women as men entering the profession

will result, eventually, in more equality in senior roles, it is

a start. If we look at the profile of journalists entering the

profession in recent years we can see that two-thirds of those

starting their careers very recently – in the last two years – are

women, almost exactly the reverse of the gender balance of

journalists who have been working for more than 30 years (see

Figure 1.1e). We can only hope that the high numbers of women

among the recent entrants to the profession will receive fair

remuneration and rise to positions of influence more easily than

did the generations that preceded them.

FIGURE 1.1e: PROPORTIONS OF MALE

AND FEMALE JOURNALISTS IN THE UK BY

YEARS OF WORKING EXPERIENCE IN THE

PROFESSION, DECEMBER 2015 (n = 682).

Figure 1.1e:

P

roportions of male

a

nd female

j

ournalists in the UK

b

y years of working

e

xperience in the

p

rofession, December

2

015

(

n

= 682).

65%

50%

52%

46%

42%

33%

36% 50% 48% 54% 58% 67%

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

<=2 3–5 6–10 11–20 21+ 30+

Men Women

Note: Data only include journalists who were working in the profession in December

2015.

Note: Data only include journalists who were working in the profession in

December 2015.

1.2 EDUCATION

Traditionally, journalism has been a profession that has

accommodated entrants without specialist training and, indeed,

without any university-level education. In 2012 Jonathan Baker,

the then Head of the BBC College of Journalism, wrote that

to get into the BBC as a journalist ‘a university degree is not

required’, adding that ‘many of the BBC’s top journalists did

not have a university education’ (Baker, 2012). While saying

a degree was ‘not required’, Baker did concede that the

qualification gave applicants ‘a definite advantage’. This view

is in line with the trend, observed globally (see e.g. Hanusch,

2013), towards the ‘academisation’ of journalism, as fewer and

fewer journalists enter the profession without both a tertiary

education and also some specialist education in journalism.

This trend is clearly evident in the UK. Indeed, Jonathan

Baker is himself now running a journalism degree programme

at the University of Essex (University of Essex, 2014). Our

survey shows that 86% of UK journalists now have at least

a bachelor’s degree. This academisation becomes even

more pronounced if we look at those who have entered the

profession in recent years. Of those with three or fewer years

of employment, 98% have at least a bachelor’s degree with

36% having a master’s. We can conclude then that journalism

has become fully academised. Given the increasing costs of

university education in the UK, especially when that education

may include a master’s degree, and given the competitiveness

of university entry, questions need to be asked about

the socio-economic diversity of future generations of UK

journalists. For example, the university entry rate for ‘men

receiving free school meals in the White ethnic group’ is just

9% (UCAS, 2015: 14) compared with 31% for all 18-year-olds in

England (UCAS, 2015: 11).

2

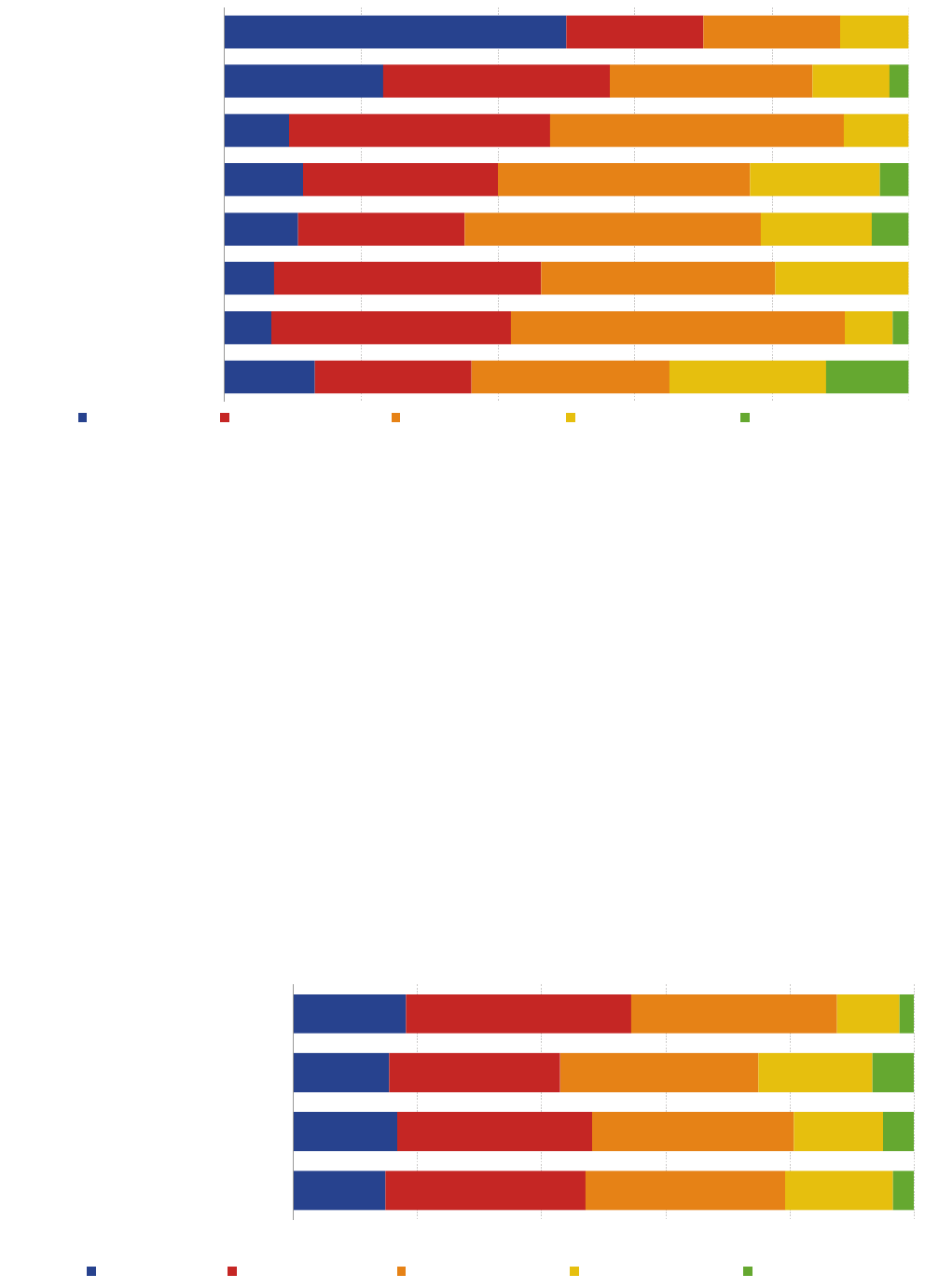

1.3 RELIGIOUS

AFFILIATION AND BELIEF

To what extent do UK journalists consider themselves aliated

with any particular religion? Comparing our data with the 2011

Census shows that all religious groups are under-represented

in the population of UK journalists with the exception of

Buddhists and Jews. Muslims are most under-represented,

followed by Hindus and Christians (see Figure 1.3a overleaf).

Of course surveys show that people can identify with a

particular religious group, perhaps for social or cultural

reasons, without practising regularly. A 2014 YouGov poll

(Jordan, 2014) found that, irrespective of any aliation with a

formal faith, 76% of those surveyed said that they were ‘not at

all’ or ‘not very’ religious. A similar number of UK journalists

feel religion is of little or no importance (74%); however,

their rejection is more profound, with 52% saying religion or

religious belief is ‘unimportant’ against 37% of the general

population who say that they are ‘not at all’ religious (see

Figure 1.3b overleaf).

2

The entry rate for disadvantaged 18-year-olds in England is 18.5% (UCAS, 2015: 13) and 16.4% for those who have received free school meals (ibid. 14).

11/ 10PERSONAL CHARACTERISTICS AND DIVERSITY

UK journalists, then, are less likely to be religious or spiritual in

general terms and much less likely to aliate with a particular

religious group than the wider community. Surprisingly,

perhaps, this finding was welcomed by some religious

representatives we talked to. A spokesperson from the Hindu

Council UK said:

It is heartening to note that a majority of UK journalists

say that religion or religious belief is of little importance

in their lives. Religious pluralism, including equal respect

for atheists, is key to the future peace and success of this

planet. Doing the right things (e.g. reporting accurately and

reflecting the true picture without power and prejudice) are

the key important factors. (Personal communication, 20

February, 2016)

FIGURE 1.3b: DEGREE OF RELIGIOSITY/

IMPORTANCE OF RELIGIOUS BELIEF

TO UK JOURNALISTS VS THE BRITISH

POPULATION.

Figure 1.3b:

D

egree of

r

eligiosity/

i

mportance of

r

eligious belief

t

o UK

j

ournalists vs

t

he British

p

opulation.

4%

20%

39%

37%

6%

20%

22%

52%

0%

20%

40%

60%

Very religious /

Very or

extremely

important

Fairly religious /

Somewhat

important

Not very

religious / Of

little importance

Not at all

religious /

Unimportant

British population (n = 2,143)

UK journalists (n = 685)

Note: Data about the British population are from a YouGov poll (Jordan, 2014)

in which respondents were asked ‘How religious, if at all, would you say you

are?’ UK journalists in our survey were asked ‘How important is religion or

religious belief to you?’

Note: Data about the British population are from a YouGov poll (Jordan,

2014) in which respondents were asked ‘How religious, if at all, would you

say you are?’ UK journalists in our survey were asked ‘How important is

religion or religious belief to you?’

While the Hindu Council UK recognised the need to encourage

minority groups, especially from deprived areas of the UK,

to join the journalism profession, their response emphasised

bridging the gap between spiritual and secular worldviews and

encouraging religious pluralism, two areas that they felt would

benefit from ‘disinterested’ journalists.

1.4 ETHNICITY

Comparing the results of our survey with data from the 2011

UK Census shows that those of Asian and Black ethnicity are

under-represented in the population of UK journalists. The

most under-represented group are Black Britons, who make up

approximately 3% of the British population but just 0.2% of our

sample. Asian Britons represent approximately 7% of the UK

population but just 2.5% of our sample (see Figure 1.4).

FIGURE 1.4: ETHNICITY OF NON-WHITE UK

JOURNALISTS IN 2015 COMPARED WITH

THE 2011 CENSUS.

Figure 1.4:

Ethnicity of

non-white UK

journalists in

2015 compared

with the 2011

Census.

2.3%

2.5%

0.2%

1.3%

2.0%

6.9%

3.0%

1.0%

0%

1%

2%

3%

4%

5%

6%

7%

Mixed race Asian Black Other

UK journalists in 2015 (n = 683)

2011 UK Census

Note: White journalists made up 94% of our sample, while the 2011 Census

revealed that 87% of the UK population was white.

FIGURE 1.3a: PERCENTAGE OF UK JOURNALISTS AFFILIATED WITH A RELIGION (OR NONE)

COMPARED WITH THE 2011 CENSUS.

Figure 1.3a: Percentage of UK journalists affiliated with a religion (or none) compared with

the 2011 Census.

31.6%

0.4% 0.4%

2.7%

0.4%

3.3%

61.1%

64.4%

4.8%

1.4%

0.5%

0.4%

1.2%

27.8%

0%

20%

40%

60%

Christian Muslim Hindu Jewish Buddhist Other religion No religion

UK journalists in 2015 (n = 669) 2011 UK Census

12REUTERS INSTITUTE FOR THE STUDY OF JOURNALISM / JOURNALISTS IN THE UK

Journalists from ethnic minority backgrounds who completed

the survey had mixed opinions on discrimination in the

industry. One, a young Asian fi nancial journalist who worked

in the trade press, said discrimination ‘is not something I’ve

ever experienced. I’m on my third journalism job and every

o ce I’ve ever worked in, bar one which was very small, was

quite diverse.’ However, he did think that the situation might

be di erent ‘on some of the nationals and defi nitely on some

of the regional newspapers’ (personal communication, 23

February 2016).

Another journalist, a Muslim magazine editor, felt his ethnicity

had been a hindrance when applying for jobs. So much so that

he once ‘applied for the same job using an “English” sounding

name and got an interview after being rejected the fi rst time’

(personal communication, 23 February 2016). Both journalists

felt that cultural expectations and social connections were part

of what prevented more Asians going into journalism. Traditional

familial ambitions for children to go into ‘respected professions’

like ‘medicine, engineering, and dentistry’ make journalism a

second-tier career; and because getting into journalism is highly

competitive it requires ‘either a lot of luck or someone you

know’, and‘Asian parents often don’t know anyone in the media’

(personal communication, 23 February 2016).

1.5 POLITICAL STANCE

Although it is more common for media institutions to be

accused of political bias – the ‘right-wing press’ or ‘the liberal

media’

3

– individual journalists too can fi nd themselves labelled

as being of the right or of the left, often as a way of seeking to

explain behaviour that is outside journalistic norms. Examples

include the ‘extreme’ rhetoric used by ‘right-wing journalist’

Richard Littlejohn (O. Jones, 2012) or the ‘controversial columns

defending . . . Palestinian freedom fi ghters’ written by ‘left-wing’

journalist Seumas Milne (Blanchard, 2015).

A search of the Nexis database of UK newspaper stories dating

back to 1982 reveals that the term ‘left-wing journalist’ has been

used 538 times, about twice as frequently as the term ‘right-

wing journalist’. But where are UK journalists on the political

spectrum? We asked journalists to choose a point on a scale

from 0 to 10 (where 0 was left, 10 was right, and 5 was centre)

that was closest to their own political stance. Our results show

that the single most chosen point on the scale was the centrist

5, with 24% of journalists choosing that position. A little over

half (53%) chose a position to the left of centre and 23% to the

right of centre (see Figure 1.5a).

FIGURE 1.5a: POLITICAL AFFILIATION OF UK

JOURNALISTS, DECEMBER 2015 (n = 603).

Figure 1.5a:

P

olitical affiliation

o

f UK journalists,

D

ecember 2015 (

n

= 603).

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

5 = political centre point Politically ‘left’ Politically ‘right’

This pattern di ers somewhat between journalists of di erent

ranks and levels of responsibility. Our survey shows that, while

the proportion of journalists with a centrist political view stays

fairly steady across the ranks, there is a clear increase in right-

of-centre journalists in more senior roles, and a corresponding

decrease in left-of-centre journalists, particularly above the rank

of junior manager (see Figure 1.5b).

FIGURE 1.5b: POLITICAL AFFILIATION OF UK

JOURNALISTS BY RANK, DECEMBER 2015.

Figure 1.5b:

P

olitical

a

ffiliation of UK

j

ournalists by

r

ank, December

2

015.

42%

55%

56%

27%

22%

26%

31%

23%

18%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

Senior managers

(n = 154)

Junior managers

(n = 228)

Rank and file

journalists

(n = 206)

Left Centre Right

Such self-reported political beliefs do not, of course,

necessarily correspond to ‘objective’ assessments of political

identity. For example, one study reported that ‘participants

showed a signifi cant bias toward perceiving themselves as

more conservative than they actually were, and this e ect was

more pronounced among independents and conservatives than

liberals’ (Zell and Bernstein, 2014).

Whatever the self-perceived or ‘objective’ political stance of

journalists, their individual beliefs are not directly and uniformly

refl ected in the output of the media. First, not all journalists

exercise the same degree of infl uence on the news agenda.

Secondly, journalists’ personal beliefs are moderated by other

infl uences on their work, such as editorial policy and journalism

ethics. The infl uences that journalists feel a ect their work are

3

A search of the Nexis database of UK newspaper stories dating back to 1982 found more than 3,000 mentions of the phrase ‘liberal media’, and more than 2,000

mentions of the ‘right-wing press’.

13/

12

PERSONAL CHARACTERISTICS AND DIVERSITY

more fully discussed in Section 6. However, we will mention

here that our survey shows journalists think ‘Editorial Policy’

and ‘Journalism Ethics’ are more influential on their work than

their personal values and beliefs.

Ethical codes of practice that apply to UK journalists mention

the need to distinguish between ‘fact’ and ‘opinion’ or

‘comment’ (NUJ, 2011; IPSO, 2016), obligations that most

journalists claim to take seriously: 66% of the journalists in our

survey ‘strongly agree’ that ‘journalists should always adhere

to codes of professional ethics’, with another 28% agreeing

‘somewhat’. Beyond strict codes of practice, UK journalists work

within a professional culture where there is an expectation

that they will be ‘detached’ and ‘report things as they are’.

We discuss the professional roles that journalists consider

important in full in Section 4. In the context of this discussion

about the extent of the influence of journalists’ political beliefs,

we will simply report how our survey revealed that more

than three-quarters felt that being a ‘detached observer’ was

‘extremely’ or ‘very’ important and that even more (93%) felt the

same about ‘reporting things as they are’.

In this section we have reported journalists’ perceptions of their

political stance, noted how that pattern changes with seniority,

and pointed to other moderating influences on journalists’

work. There is no space to enter into a full debate on how

journalists’ personal political beliefs weigh up against other

factors in influencing the selection of news stories and their

framing. However, we will say that there are those who believe

that influences such as ownership, commercial considerations,

sourcing practices, and media management by vested interests

carry much more weight than the beliefs of individual journalists

(see e.g. Herman and Chomsky, 1994).

1.6 CONCLUSIONS

Although women make up a relatively high proportion of the

journalism profession in the UK and are on a par with their male

colleagues in terms of the editorial freedom they wield and

their contractual conditions, they are less well remunerated and

less likely to progress to senior positions. The normalisation of

the graduate entry route into the profession is helping correct

historical gender imbalances,

4

although this academisation

of journalism may have other, undesirable, consequences,

particularly for its socio-economic diversity.

UK journalists reflect the general population’s religious diversity

far less well than its male/female ratio, although some religious

representatives do not think this is necessarily a bad thing,

as long as journalists report accurately and without bias.

UK journalism has a significant diversity problem in terms of

ethnicity, with Black Britons, for example, under-represented

by a factor of ten. Some of our survey’s respondents had

witnessed discrimination based on their ethnic characteristics

first-hand. Commenting on this survey’s findings, Michelle

Stanistreet, general secretary of the National Union of

Journalists, said ‘employers must now be compelled to do an

equality audit of their own organisations and then address clear

disparities’ (personal communication via Oscar Williams, 26

February 2016).

About half of journalists in the UK say they take a left-of-centre

political stance, with the remaining half split between the centre

and the right-wing. Although certain political beliefs (those

to the right-of-centre) increase with levels of responsibility,

journalists claim to adhere strongly to the professional

paradigm of neutrality. They also maintain that their personal

beliefs, political and otherwise, are less important than other

influences on their work. While this may be so, those other

influences, such as public relations activity, are not politically

neutral and, as we will show later, their eects are strong and

growing.

4

Women outnumbered men on UK journalism degrees in every year between 2007 to 2014 except 2008 (Reid, 2015).

14REUTERS INSTITUTE FOR THE STUDY OF JOURNALISM / JOURNALISTS IN THE UK

In this section we present data on the employment conditions

of journalists in the UK, including the nature of their contracts;

the number of newsrooms and outlets they work for; the

proportion who take other paid work; and their job roles, rank,

and income. We also consider the geographical reach of the

primary news outlets journalists work for, to try to gauge, at a

time of instant international communication, the growth in the

importance of audiences who are geographically removed from

the journalists who serve them.

2.1 NATURE OF

CONTRACT

TABLE 2.1: PROPORTIONS OF UK

JOURNALISTS WORKING FREELANCE OR AS

A PERMANENT OR TEMPORARY EMPLOYEE.

Table 2.1: Proportions of UK journalists working freelance or as a

p

ermanent or temporary employee.

This

survey

(2015)

NCTJ

(2012)

LFS

(2015)

Whole

labour

force

a

Permanent 74% 66% 61%

79%

Temporary 7% 5% 1%

5%

Freelance

b

17% 21% 37%

15%

Other 3% 8% 1%

0.5%

a

June–September 2015. Source: ONS, 2015b.

b

The ONS LFS used the term ‘self-employed’ rather than ‘freelance’. The NCTJ’s

survey also asked journalists whether they were ‘self-employed’ (either freelance or

working for their own company).

a. June–September 2015. Source: ONS, 2015b.

b. The ONS LFS used the term ‘self-employed’ rather than ‘freelance’. The

NCTJ’s survey also asked journalists whether they were ‘self-employed’

(either freelance or working for their own company).

Our survey shows that 81% of journalists in the UK are regular

employees, with 17% working on a freelance basis, and another

3% having some ‘other’ arrangement (see Table 2.1). This

proportion of freelance journalists is slightly lower than that

found in the NCTJ’s Journalists at Work survey (NCTJ, 2012),

and signifi cantly lower than that found in the O ce for National

Statistics’ Labour Force Survey (LFS). In 2012, the NCTJ found

that 21% of journalists worked in a ‘self-employed’ capacity –

12% freelance and 9% for their own company (NCTJ, 2012). For

the third quarter of 2015, the LFS shows 37% of journalists as

being self-employed (ONS, 2015b), although the small sample

size (96) means we should interpret their data with caution. The

higher proportion of freelancers found by the LFS may be due

to the fact that journalists looking for work are included (8% of

the sample), some of whom may identify as freelancers. The

sampling strategy we used in our survey targeted journalists

who were actively working – excluding those who earned less

than 50% of their income from journalism.

At 17%, the proportion of journalists we found to be working

freelance is slightly above the average for the UK labour force,

although about the same as in the wider ‘Information and

Communications’ sector: in the third quarter of 2015, 15% of

the UK labour force were self-employed as were 16% of those

working in ‘Information and Communications’ (ONS, 2015b).

There have been regular reports of journalists in permanent

employment being made redundant and replaced by freelance

(and ‘citizen’) journalists. For example, in October 2015, the

Brighton Argus, part of the Newsquest group, announced it

intended to ‘reduce the pictures department from three full-

time photographers to one full-time picture editor as part of

its policy to use readers’ pictures and freelance contributions’.

Similar changes have happened in other newspaper groups

including Johnston Press (NUJ, 2016).

Has there been, then, an increase in the proportion of freelance

journalists in recent years? Is the restructuring of the sort

mentioned above creating more opportunities for freelance

journalists – as proprietors’ press releases may lead us to

believe – or is it, on the other hand, putting out of work skilled

professionals who are unlikely to continue working in journalism

due to the limited opportunities available to freelancers?

If we look at the LFS data on ‘Journalists, newspaper and

periodical editors’ from 2001 to 2015, we see that there is not a

clear pattern of increased freelance working. For example, the

proportion of freelance journalists in 2011 (32%) was no higher

than it was in 2002, 2004, or 2005 (see Figure 2.1 overleaf).

We would conclude, then, that opportunities for freelance work

within journalism do not appear to be increasing. Instead, it

may be the case that many of those being made redundant are

being lost to the profession along with the skills they embody.

Mike Pearce, for 20 years an editor of local newspapers in

Kent, suggests that the gaps left, especially at the local level,

EMPLOYMENT

CONDITIONS

NEIL THURMAN

15/

14

are being fi lled by low-quality content from ‘citizen journalists’.

This trend, he believes, is hastening the demise of newspapers,

with readers reluctant to buy titles that are increasingly poorly

illustrated and written:

The arrival of so-called ‘citizen journalists’ means

proprietors are near their holy grail of producing news

without the expense of reporters. Training schools have

closed, on-the-job training is minimal. Background stories

are rarely tackled, courts go unreported, raw copy appears,

unsubbed. (Personal communication, 19 February 2016)

FIGURE 2.1: PROPORTION OF UK

JOURNALISTS IDENTIFYING AS SELF-

EMPLOYED, 2001–2015.

Note: Data are for June–September each year. Source: ONS, 2015b.

Figure 2.1: Proportion of UK journalists

i

dentifying as self-employed, 2001–2015.

0%

20%

40%

60%

Note: Data are for June–September each year. Source: ONS, 2015b.

2.2 FULL- AND PART-TIME

WORKING

Our questionnaire only asked journalists who were permanent

or temporary employees – not freelancers – whether they

worked full- or part-time. The results show there is a strong

connection between the type of employment contract and

full-time working. A higher proportion (90%) of journalists who

are permanently employed work full-time than those on a

temporary contract, for which the fi gure is 50%. Our fi gures

show the same general trend as the NCTJ’s 2012 survey. That

survey, unlike ours, did report data on freelancers, showing that

only about half work full-time (see Table 2.2).

TABLE 2.2: PROPORTIONS OF UK

JOURNALISTS WORKING FULL-TIME.

Table 2.2: Proportions of UK journalists

w

orking full-time.

This survey

(2015)

NCTJ

(2012)

Permanent 90% 89%

Temporary 50% 72%

Freelance

51%

2.3 RANGE OF

NEWSROOMS AND NEWS

OUTLETS

A typical journalist in the UK works in a single newsroom for

two outlets, for example, a print and an online edition. To be

more precise, our survey found that the average number of

newsrooms worked in is 1.48, and the average number of news

outlets 2.2.

Freelancers are more likely to work for multiple newsrooms.

Whereas over 80% of journalists in regular employment work

for one newsroom, only 33% of freelancers do, with 14%

working for three, 9% working for four, and 6% working for

fi ve. Freelancers are also more likely to work for multiple news

outlets. While over 60% of regular employees work for a single

news outlet, only 20% of freelancers do, with 24% working

for two, 15% working for three, 12% working for four, and 7%

working for fi ve.

Although newsrooms do produce separate news outlets in the

same medium, for example, BBC News at Ten and BBC News

at Six, many have outlets in more than one medium. Section 3.1

describes the cross-media working patterns of journalists in the

UK, showing, for example, that 54% work in one medium while

42% work across at least two media.

2.4 JOB ROLE AND RANK

We asked journalists to choose a job category that best

described their current position. ‘Reporter’ was the most

common, followed by ‘Editor-in-chief’ and ‘Senior editor’.

‘Managing editors’ came next, followed by ‘Desk’ and

‘Department’ heads (see Table 2.4a).

TABLE 2.4a: UK JOURNALISTS’ JOB ROLES,

DECEMBER 2015 (n = 698).

Table 2.4a: UK journalists’ job roles,

D

ecember 2015 (

n

= 698).

Position in newsroom

Reporter 23%

‘Other’ 23%

Editor-in-chief

15%

Senior editor

15%

Managing editor

7%

Desk head or assignment editor

6%

Department head

6%

Producer

3%

News writer

1%

Trainee

0.4%

Note: Due to rounding, percentages do not add up to 100%.

Note: Due to rounding, percentages do not add up to 100%.

Nearly a quarter of our respondents felt that their role did

not fi t into one of our nine predefi ned categories, including

some freelancers unsure, perhaps, of how to respond to a

question which asked for their role ‘in the newsroom’ (some

made the point that, as freelancers, they did not work in

16

REUTERS INSTITUTE FOR THE STUDY OF JOURNALISM / JOURNALISTS IN THE UK

a newsroom). Also in the ‘Other’ category were senior or

specialist journalists who felt that their role was not adequately

described by our predefi ned terms ‘reporter’ or ‘news writer’.

Production roles, such as sub-editor or production editor,

also featured. We present a summary of the other roles

journalists defi ned for themselves in Table 2.4b. In it we have

grouped over 100 di erent job titles into 13 broad categories

covering proprietorial, production, supervisory, and writing and

presenting roles. For the purpose of further analysis we also

recategorised the roles of all the journalists in our survey into

three even broader groups:

• senior/executive managers with strategic authority;

• junior managers with operational authority;

• rank and fi le journalists with limited authority.

TABLE 2.4b: OTHER JOB ROLES SPECIFIED

BY UK JOURNALISTS, DECEMBER 2015

(n = 698).

Table 2.4b: Other job roles specified

b

y UK journalists, December 2015 (

n

= 698).

Position in newsroom

Freelance 4%

Deputy/section editor 4%

Feature writer/columnist/leader writer

2%

Writer/senior/chief writer

2%

Editor

2%

Specialist correspondent

1%

Presenter

1%

Sub-editor/senior sub-editor

1%

Other

1%

Broadcast journalist

1%

Online/social media editor

1%

Production editor

1%

Publisher/founder/MD

1%

Our recategorisation is relatively simple. By comparison, the

NCTJ’s Journalists at Work report assigned journalists to seven

groups. The simplicity of our approach has allowed us to

conduct relatively robust cross-tabulations, for example, looking

at the editorial independence of rank and fi le journalists against

their junior and senior managerial colleagues (see Section 3.3)

and how pay di ers by rank.

Overall we found that 25% of our sample were in senior

managerial roles, 38% were in junior managerial roles, and 36%

were rank and fi le journalists. Although lacking in operational or

strategic authority, rank and fi le journalists – for example, those

who call themselves ‘senior writers’, ‘special correspondents’,

and ‘presenters’ – can have salaries in the higher salary bands.

Four rank and fi le journalists told us they took home more than

£115,000 per year.

2.5 INCOME

Our survey shows that UK journalists’ salaries range widely,

5

with around 20% earning less than £19,500/year (gross), and

about 5% earning more than £76,800. The median salary band

was £28,812–£38,400. Our survey only included journalists

who were earning at least 50% of their income from journalism,

which may explain why the median salary earned is higher

than that found by the NCTJ’s Journalists at Work survey. In

that survey more of the sample worked part-time. The median

salary band for journalists surveyed by the NCTJ in 2012 was

£25,000–£29,999, which, when adjusted for infl ation, equates

to £26,629–£31,953 in 2015. However, because of the di erent

sampling strategies and salary bands used by the two surveys,

it is di cult to make comparisons. We are reluctant, therefore,

to reach any conclusions about the growth of journalists’

average salary since 2012. What we can do, however, is

compare incomes across other dimensions: employment

contract, rank, age, gender, education, and type of news outlet

– both in terms of geographical reach and medium.

BY GENDER

In Section 1, which addresses UK journalists’ personal

characteristics and diversity, we describe the pay di erence

between men and women, showing how women working full-

time in journalism earn less than their male counterparts.

BY AGE

As expected, journalists’ salaries rise in their twenties, thirties,

forties, and fi fties, only dropping o at age 60 and over when

a greater proportion start to work part-time and in a freelance

capacity.

6

Almost all (88%) of the journalists in our survey aged

24 or less earned between £0 and £19,200. Given that many

will not be earning at the top of that band, this fi gure is likely

to be at, or even below, the living wage

7

for many. Of those

in their mid to late twenties, a time when many people would

like to buy a property, the vast majority (83%) are earning less

than £29,000 a year (see Figure 2.5a overleaf), about the

same as the median graduate starting salary in 2014–15 (BBC

News, 2015). Given that it has been estimated that, across the

UK, a fi rst-time buyer needs a minimum income of £41,000 –

and £77,000 in London – (Kollewe, 2015), a ordable housing

is a critical issue for many journalists unless they have other

sources of income.

BY MEDIUM WORKED IN

The NCTJ’s 2012 survey found that journalists working mainly

in television earned the highest salaries, with radio and online

coming next, followed by magazines and then newspapers. Our

survey did not ask respondents to indicate their main medium

of employment but rather all the media they worked in (about

42% told us they worked across more than one medium).

Using those data we are able to give an impression of the links

5

Although, as we discuss in Section 7.5, income diversity among journalists is not as wide as that of the general population.

6

Of journalists in their fi fties, 8% work part-time compared with 12% of those in their sixties. 21% of those in their fi fties work freelance compared with 32% of those in

their sixties.

7

£16,302 for those working outside London and £18,570 for those in the capital (Vero, 2014).

17/

16

EMPLOYMENT CONDITIONS

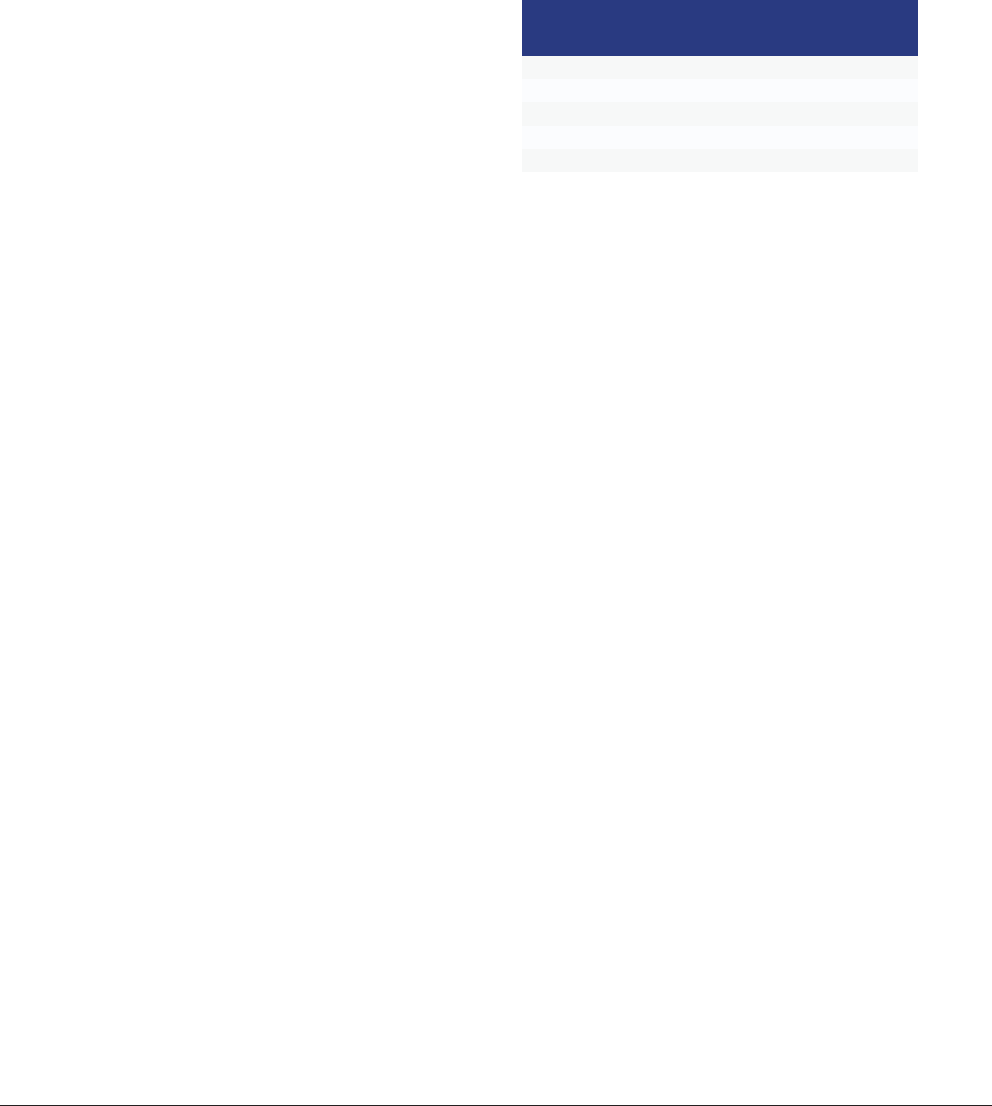

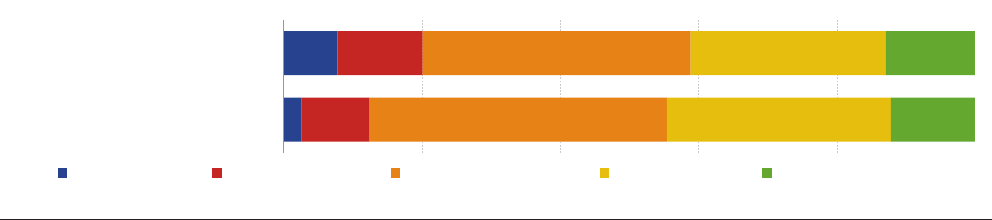

Figure 2.5a: Gross monthly salaries of UK journalists by age, December 2015 (

n

=

587).

88%

35%

12%

9%

9%

23%

8%

48%

41%

27%

20%

30%

4%

16%

39%

37%

37%

33%

2%

7%

23%

24%

10%

2%

5%

11%

5%

<=24

25–29

30–39

40–49

50–59

>=60

£0–1,600 £1,601–2,400 £2,401–4,000 £4,001–6,400 >=£6,401

Figure 2.5b: Gross monthly salaries of UK journalists by medium worked in,

D

ecember 2015 (

n

= 618).

11%

19%

16%

8%

18%

16%

18%

15%

28%

33%

37%

22%

21%

30%

33%

29%

36%

25%

29%

46%

44%

30%

31%

39%

19%

15%

12%

19%

11%

19%

14%

13%

4%

7%

6%

6%

6%

5%

4%

4%

Daily newspaper

Weekly newspaper

Magazine

Television

Radio

News agency

Online outlet (stand-alone)

Online outlet (of offline outlet)

£0–1,600 £1,601–2,400 £2,401–4,000 £4,001–6,400 >=£6,401

Note: Because respondents could indicate that they worked in multiple media (and 42% do, see section 3.1) these figures do not represent the salaries paid by the

separate media industries, but rather the salaries of journalists who work wholly or partly in each media industry.

Figure 2.5c: Gross monthly salaries of UK journalists working in one medium or

two media, December 2015 (

n

= 508).

21%

17%

32%

30%

30%

32%

11%

17%

7%

3%

Work in two media

Work in one medium

£0–1,600 £1,601–2,400 £2,401–4,000 £4,001–6,400 >=£6,401

FIGURE 2.5a: GROSS MONTHLY SALARIES OF UK JOURNALISTS BY AGE, DECEMBER 2015

(n = 587).

FIGURE 2.5b: GROSS MONTHLY SALARIES OF UK JOURNALISTS BY MEDIUM WORKED IN,

DECEMBER 2015 (n = 618).

FIGURE 2.5c: GROSS MONTHLY SALARIES OF UK JOURNALISTS WORKING IN ONE MEDIUM OR

TWO MEDIA, DECEMBER 2015 (n = 508).

Note: Because respondents could indicate that they worked in multiple media (and 42% do, see section 3.1) these fi gures do not represent the salaries paid by

the separate media industries, but rather the salaries of journalists who work wholly or partly in each media industry.

18

REUTERS INSTITUTE FOR THE STUDY OF JOURNALISM / JOURNALISTS IN THE UK

between medium worked in and salary. Our results show, as

the NCTJ’s survey did in 2012, that journalists working wholly

or partly in television are most highly remunerated, with 25%

receiving a gross monthly salary of more than £4,001. At the

other end of the spectrum, those working wholly or partly in

magazines and weekly newspapers appear to be the least well

remunerated (see Figure 2.5b).

We also looked at di erences in salary between journalists who

practised in more than one medium and those who did not. The

results show that there is no clear fi nancial benefi t to working

in more than one medium. For example, while 47% of those

working in one medium earn less than £2,400/month, 53% of

those working in two media do (see Figure 2.5c).

8

Why, then, are the skills required to work across multiple media

apparently not being rewarded? Spyridou and Veglis (2016)

believe the convergence projects that provide opportunities for

journalists to work across multiple media ‘are primarily driven

by the market logic that aims to reduce costs, while increasing

productivity and maximising profi t’, part of a historical process

whereby ‘technology has been used by owners and managers

to . . . make journalistic labor cheaper’. So, although much of

the discussion around multiskilling is framed in positive terms,

what Spyridou and Veglis call the ‘super journalist paradigm’,

some believe that under convergence there is a tendency

for journalists’ skills to be spread thinly over multiple formats,

exploiting ‘the technological and social opportunities o ered by

convergence in order to enhance monetization opportunities’

(ibid.).

In a study of production convergence in UK newsrooms, Saltzis

and Dickinson (2008: 222) predicted a two-tier workforce with

‘the “single skilled” specialists, valued for their high journalistic

standards; and “the multiskilled [journalist]”, valued for their

versatility and adaptability’. Our survey indicates that versatility

and adaptability across multiple media may not command a

premium over high journalistic standards in a single medium.

BY NATURE OF CONTRACT

The median salary band for freelance and full-time journalists

who completed our survey was the same. Looking at the spread

of earnings we can see that, although a greater proportion of

freelance journalists are in the lowest salary band, a higher

proportion are in the highest salary band (see Figure 2.5d).

Overall our survey does not show a huge fi nancial

disadvantage to working on a freelance basis, at least in

terms of annual income. However, other issues face freelance

journalists. A comprehensive survey by the National Union of

Journalists (NUJ, 2004) showed ‘serious, and worrying, fl aws

in the way that sta editors and commissioning editors treat

freelancers’ and the e ect of the isolation that can come with

working from home.

Figure 2.5e: Gross monthly salaries of UK journalists by rank, December 2015.

12%

10%

27%

28%

33%

30%

33%

38%

29%

17%

16%

11%

10%

3%

4%

Senior managers

(n = 150)

Junior managers

(n = 239)

Rank & file journalists

(n = 228)

£0–1,600 £1,601–2,400 £2,401–4,000 £4,001–6,400 >=£6,401

Figure 2.5d: Gross monthly salaries of UK journalists by employment status,

December 2015.

21%

14%

31%

26%

31%

38%

35%

34%

26%

12%

16%

5%

6%

5%

Freelancers (n = 97)

Full-time employees (n = 462)

Part-time employees (n = 42)

£0–1,600 £1,601–2,400 £2,401–4,000 £4,001–6,400 >=£6,401

FIGURE 2.5e: GROSS MONTHLY SALARIES OF UK JOURNALISTS BY RANK, DECEMBER 2015.

FIGURE 2.5d: GROSS MONTHLY SALARIES OF UK JOURNALISTS BY EMPLOYMENT STATUS,

DECEMBER 2015.

8

Some may seek to explain this result by suggesting that younger, less well-paid journalists are more likely to work across multiple media having, perhaps, received

multi-media training at university. In fact, journalists who have entered the profession in the last fi ve years do not work across more media than their more

experienced colleagues (see Section 3.1).

19/

18

EMPLOYMENT CONDITIONS

BY ROLE AND RANK

As is to be expected, journalists’ salary rises with rank.

However, our survey found that around 15% of rank and fi le

journalists, those we classifi ed as having limited strategic or

operational authority, were earning salaries above £48,000.

Furthermore, holding a position of responsibility did not

necessarily come with a high salary. Over 40% of journalists

who were classifi ed as senior/executive managers with

strategic authority were earning less than £29,000 (see Figure

2.5e on previous page).

Looking at income by job role in more detail we can see that

‘News writers’ were the least well paid (other than trainees),

with 50% earning less than £19,200/year, followed by

‘Reporters’. ‘Editors-in-chief’ were the most highly rewarded,

with 35% earning more than £48,000 (see Figure 2.5f).

BY EDUCATION LEVEL AND

SPECIALISM

There are negligible di erences in salary between those with

at least a bachelor’s degree and those without. In fact those

without a BA or equivalent are actually more likely to be

earning a salary in the upper three of our fi ve salary bands than

those who have one (see Figure 2.5g). This does not, of course,

mean that a degree is without value. As we show in Section 1,

on journalists’ personal characteristics and diversity, a degree

is now almost essential as a way into journalism. Instead, these

results are more indicative of how, in the past, entry into, and

progress through, the profession did not depend on formal

qualifi cations.

There is an inverse relationship between whether

journalists have specialised (at university) in journalism and

communication and the salary they earn, with those who have

specialised earning less than their colleagues whose university

Figure 2.5f: Gross monthly salaries of UK journalists by job role, December

2015.

13%

7%

7%

11%

12%

10%

23%

50%

23%

35%

39%

24%

28%

38%

33%

20%

29%

49%

34%

43%

37%

43%

30%

20%

23%

7%

20%

16%

19%

10%

11%

10%

12%

5%

4%

3%

Editors-in-chief (n = 83)

Managing editors (n = 43)

Desk heads/assignment

editors (n = 41)

Department heads (n = 37)

Senior editors (n = 95)

Producers (n = 21)

Reporters (n = 142)

News writers (n = 10)

£0–1,600 £1,601–2,400 £2,401–4,000 £4,001–6,400 >=£6,401

Figure 2.5g: Gross monthly salaries of UK journalists by level and type of

education, December 2015 (

n

= 575).

15%

17%

16%

18%

33%

31%

28%

36%

33%

33%

32%

33%

18%

14%

18%

10%

3%

5%

7%

No degree

At least BA/BSc

Degree in other subject

Degree in journalism/communication

£0–1,600 £1,601–2,400 £2,401–4,000 £4,001–6,400 >=£6,401

FIGURE 2.5f: GROSS MONTHLY SALARIES OF UK JOURNALISTS BY JOB ROLE, DECEMBER

2015.

FIGURE 2.5g: GROSS MONTHLY SALARIES OF UK JOURNALISTS BY LEVEL AND TYPE OF

EDUCATION, DECEMBER 2015 (n = 575).

20

REUTERS INSTITUTE FOR THE STUDY OF JOURNALISM / JOURNALISTS IN THE UK

Figure 2.5h: Gross monthly salaries of UK journalists by geographical reach of

primary outlet, December 2015.

35%

22%

18%

10%

26%

36%

29%

32%

30%

29%

33%

36%

7%

11%

14%

18%

7%

5%

Local (n = 43)

Regional (n = 92)

National (n = 261)

Transnational (n = 222)

£0–1,600 £1,601–2,400 £2,401–4,000 £4,001–6,400 >=£6,401

FIGURE 2.5h: GROSS MONTHLY SALARIES OF UK JOURNALISTS BY GEOGRAPHICAL REACH

OF PRIMARY OUTLET, DECEMBER 2015.

studies were not related to journalism or communication.

However, this di erence is likely to be related to age

rather than to a specialist education in journalism being an

impediment to promotion, because a higher proportion of new

entrants to the profession have a degree in journalism than

their older, higher-earning colleagues (see Section 5.1).

BY REACH OF PRIMARY OUTLET

Our survey asked journalists to state the reach (local, regional,

national, or transnational) of the news medium for which they

do most of their work. Although reach is a di cult concept

in an era of global digital communication, the results show

that higher salaries are linked to working for an outlet with

wider geographical market reach. For example, about 35%

of local journalists earn less than £19,200

9

compared with

fewer than 10% of those working for a publication with an

international reach. At the other end of the scale, those working

in publications with a transnational reach are about twice as

likely to earn more than £48,000 as those working in local

publications (see Figure 2.5h).

2.6 OTHER OCCUPATIONS

Perhaps because of their low levels of pay, a relatively high

proportion of journalists have a secondary occupation. Our

survey found that 27% of journalists engaged in other paid

activities. This fi gure is slightly lower than found by the NCTJ

in 2012, again probably due to the higher number of freelance

journalists surveyed by the NCTJ. The NCTJ found that the

extent to which journalists worked in other jobs varied less than

expected according to rank. Our results were slightly di erent,

with only a fi fth of junior managers engaging in other paid work

compared with 35% of senior managers and 28% of rank and

fi le journalists (see Table 2.6).

The LFS for the third quarter of 2015 shows that only 3.7% of

the entire UK labour force did ‘other paid work . . . in addition

to’ a main job. Given the similarity of the questions asked in

our survey and by the LFS, we are reasonably confi dent to

conclude that journalists are more than seven times more likely

to have a secondary paid occupation than the average worker

in the UK.

TABLE 2.6: PROPORTION OF UK

JOURNALISTS WHO HAVE OTHER PAID

OCCUPATIONS, 2012 AND 2015.

Table 2.6: Proportion of UK journalists

w

ho have other paid occupations,

2

012 and 2015.

Our survey

(2015)

(n = 692)

NCTJ

(2012)

(n = 1064)

All journalists 27% 34%

Senior managers 35%

Junior managers

20%

Rank and file journalists 28%

Editorial management 27%

Section heads

30%

Non-editorial

management/section

heads

49%

2.7 GEOGRAPHICAL

REACH OF NEWS OUTLET

In an era of instant worldwide communication, when the

fourth most popular online newspaper in the US is the

British MailOnline (Alexa, 2016), the nature of the audiences

that news outlets serve has changed. Our survey asked

journalists to indicate the geographical reach of the news

outlet for which they did most of their work. We present the

data here and have used them elsewhere in this study to

analyse, for example, the di erences in salary or in editorial

freedom between journalists working at news outlets with a

local, regional, national, or transnational reach. The NCTJ’s

2012 survey gathered data on the proportions of journalists

working in provincial and national newspapers, radio, and

television. Our data, although not as specifi c at the provincial

and national level, goes further than the NCTJ’s survey by

asking journalists whether they feel their primary news outlet

addresses a transnational audience.

9

This fi gure is almost identical to that found by a Press Gaze e survey in 2015 (Turvill, 2015b).

21/

20

EMPLOYMENT CONDITIONS

Over a third of UK journalists feel that their main news outlet

has a transnational reach (see Table 2.7a). Such outlets

include specialist publications aimed, for example, at fi nancial

professionals or sports fans; and emerging internet-only

news sites that have global branding and operations in

several di erent countries. Such sites, including Vice News,

the Hu ngton Post, Politico, and BuzzFeed, have gained

signifi cantly in popularity in recent years and are now amongst

the most visited news destinations in the UK. For example, the

Hu ngton Post is the third most popular online news source

in the UK and BuzzFeed attracts more online visitors than ITV

News, Times online, and Independent online (Newman, 2015:

24).

TABLE 2.7a: UK JOURNALISTS’

UNDERSTANDING OF THE GEOGRAPHICAL

REACH OF THE NEWS MEDIUM THEY DO

MOST OF THEIR WORK FOR, DECEMBER

2015.

Table 2.7a: UK journalists’ understanding

o

f the geographical reach of the news medium

t

hey do most of their work for, December 2015.

Reach

All journalists

(n = 700)

Journalists working

for UK national

newspapers

(n = 125)

Local 7% 0%

Regional 14% 2%

National

42% 69%

Transnational 36% 30%

Some journalists working for what have, traditionally, been

national and regional newspapers in the UK also believe that

the reach of their primary news outlet is now international.

Indeed, we found that a third of journalists working for UK

‘national’ newspapers, such as the Guardian, Daily Mail,

The Times, and the Daily Telegraph, now consider their

outlet’s reach to be transnational. Although many UK national

newspapers have had an overseas audience for their print

editions for many years, such international distribution is

expensive, meaning it has been limited in extent. For example,

96% of the Daily Mail’s average daily print circulation is within

England, Wales, Scotland, Northern Ireland and the Republic of

Ireland and only 4%, a total of 56,680 copies, in foreign markets

(ABC, 2016).

The overseas market for UK news publications has been

changed by online publication, making the product available

outside the traditional limitations of print distribution and

increasing the exposure of UK news brands on the international

stage. It has been estimated that online has increased UK

newspapers’ daily overseas audience by between seven and 16

times (Thurman, 2014). MailOnline, for example, now gets 70%

of its online visitors from outside the UK (ABC, 2016).

However, overseas visitors are not as engaged as those from

news outlets’ home markets. The extent of this relative lack

of engagement seems to have remained consistent over the

years. For example, in 2005 overseas readers of UK online

newspapers read ‘3–4 times fewer pages than their domestic

counterparts’ (Thurman, 2007), identical to the pattern in

January 2016 for MailOnline (see Table 2.7b).

TABLE 2.7b: PROPORTIONS OF UNIQUE

BROWSERS AND PAGE IMPRESSIONS FROM

THE UK AND OVERSEAS REGISTERED BY

MAILONLINE, JANUARY 2016.

Table 2.7b: Proportions of unique browsers

a

nd page impressions from the UK and

o

verseas registered by MailOnline,

J

anuary 2016.

Unique

browsers

Page

impressions

Monthly

page

impressions

per unique

browser

UK 30% 63% 54

Rest of the

World

70% 37% 13

Source: Audit Bureau of Circulations.

Nevertheless, in spite of this relative lack of engagement,

the presence of overseas readers does seem to have shifted