1

Plan for Play in public

spaces, 2030 horizon in

Barcelona

In collaboration with:

2

Table of contents

1. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................... 3

2. PROCESS OF DRAFTING THE CROSS-CUTTING, PARTICIPATORY PLAN ........................................ 6

3. FRAMEWORKS AND REASONS .................................................................................................. 11

3.1 FRAMEwORKS: LEGISLATION, COMMITMENTS, PLANS AND STRATEGIES ............................................................ 11

3.2 REASONS: WHY AN OUTDOOR PLAY PLAN FOR THE CITY OF BARCELONA? ............................................... 15

4. PARADIGM SHIFT: 3 LAYERS AND 7 CRITERIA FOR A PLAYABLE CITY ........................................ 21

4.1 THE COLLECTIVE BENEFITS OF PLAY ..................................................................................................................... 21

4.2 THE 3 LAYERS FOR RETHINKING AND PROMOTING MORE AND BETTER PLAY OPPORTUNITIES IN PUBLIC SPACES 22

4.3 QUALITY CRITERIA FOR MOVING TOWARDS A PLAYABLE CITY ............................................................................. 24

5. DIAGNOSIS OF THE OPPORTUNITIES FOR PLAY IN BARCELONA’S PUBLIC SPACES .................... 29

5.1 THE PLAYFUL INFRASTRUCTURE ........................................................................................................................... 30

5.2 PLAYFUL USES OF PUBLIC SPACE ........................................................................................................................... 51

5.3 SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................................................... 59

6. 2030 HORIZON AND TARGETS: BARCELONA A PLAYABLE CITY ................................................. 62

6.1 HORIZON 2030 ........................................................................................................................ 62

6.2 Key milestones of the 2030 Plan…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..64

7. OPERATIONAL CONTENTS OF THE PLAN ................................................................................... 68

7.1 STRATEGIC LINES .................................................................................................................................................. 68

7.2 GENERAL OBJECTIVES OF THE PLAY PLAN ............................................................................................................. 69

7.3 PUBLIC SPACE PLAY PLAN ACTIONS ...................................................................................................................... 70

7.4 LEAD PROJECTS .................................................................................................................................................... 92

7.5 ESTIMATED BUDGET FOR THE LEAD PROJECTS AND ACHIEVING THE TARGETS .................................................... 122

8. GOVERNANCE, MONITORING AND EVALUATION OF THE PLAN .............................................. 125

8.1 GOVERNANCE ................................................................................................................................................... 125

8.2 MONITORING AND EVALUATION ....................................................................................................................... 128

9. SCHEDULE .............................................................................................................................. 129

10. BIBLIOGRAPHY ....................................................................................................................... 134

3

1. Introduction

The Barcelona Public Space Play Plan Horizon 2030 is the city’s first such plan, a pioneering

roadmap that puts outdoor play and physical activity among the key polices for creating a

more habitable city and improving the well-being, health and community life of its residents,

starting with children and teenagers.

As envisaged, and on the foundations laid by the Barcelona plays things right Strategy:

towards a public space play policy (presented at the Full Council meeting in February 2018),

this Plan has been drawn up in a year with a cross-cutting, participatory approach. Its

purpose is to improve and diversify the opportunities for play and physical activity in public

spaces because of its ample benefits for the development and well-being of children and

adolescents, as well as the health and social life of all citizens. The Plan is also based on the

premise that an urban environment that is more suitable for growing up and spending

childhood in is a better city for everyone.

Drafting the Play Plan, coordinated by the Barcelona Institute of Childhood and Adolescence,

has involved 400 people, including council staff, experts, social entities and ordinary citizens,

both children and adults. The initial diagnoses have produced new data and knowledge and

2030 has been agreed as the target date for achieving the playable city model, with 3 core

strategies, 14 objectives and 10 measurable targets. Criteria based on international

benchmarks have been established for Barcelona, in order to start making the changes

operational, and over 60 specific actions have been identified and planned involving many

city services and players. A start has already been made on some of these in certain

neighbourhoods which can be scaled up to a city level and others are set to get under way.

Obviously, the Public Space Plan is not starting from nothing. It catalyses lines of action by

giving shape to various aspects of other municipal plans and strategies, such as those on

greenery and sustainability, the climate, urban planning for gender and everyday life,

universal accessibility or sports facilities, as well as childhood, adolescence and ageing.

Moreover, the Plan contributes to achieving the Agenda 2030 Sustainable Development

Goals for making cities safer, more inclusive and more resilient by adapting public spaces so

they are more suited to social groups with less presence there. In other words, the Plan adds

a playability layer to a city model that is committed to greening, sustainability and climate

change mitigation; to calming city streets and reclaiming them as places for people to meet

in their leisure time; to being an educating city, with healthy neighbourhoods and more

inclusive environments that encompass age, gender, background and functional diversity.

The Public Space Play Plan is the result of answering some important questions for improving

the everyday life of city residents: what does Barcelona’s urban environment offer for

outdoor play and physical activity, thinking about children first of all but also adolescents,

young adults, grown-ups and elderly people? What interventions could be promoted and

boosted to encourage this playful and physical activity alongside other citizen uses of public

spaces? What aspects of the urban model do we need to rethink if we want to diversify and

improve the playful infrastructure, going beyond the standard playgrounds and play areas?

4

The Play Plan has enabled the city to start answering these questions, which are relevant to

the City Council’s commitment and obligation to make progress on the rights of children and

adolescents, bearing in mind the Child-Friendly City seal of recognition it received in 2008,

renewed in 2018. Henceforth, Barcelona City Council will be held accountable – under the

requirements that the United Nations imposes on public authorities by means of the

Committee on the Rights of the Child’s General Comments on the right to play – for

protecting, respecting and promoting the human right of children and adolescents to play

and leisure (recognised under Article 31 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child). In fact,

4 out of 10 Barcelona residents have a direct interest in the well-being of children and

adolescents in the city (because 15% are minors and 23% are adults who live with and look

after them). Moreover, we know that people’s experiences in this stage of their lives

determine the paths they take in the future, as well as social cohesion in the city. Therefore,

the more creative, diverse, free, inclusive and shared play they take part in when they are

young, the greater will be their independence, resilience, social skills and physical and mental

health later in life.

Given this approach and commitment, Barcelona City Council has taken a qualitative step

towards a public space play policy that is based on a comprehensive, cross-cutting view and

combines urban planning actions (ranging from micro-interventions and tactical planning to

major urban development projects) and social actions (from touring animation initiatives to

new public service concepts) in order to move forward as a playable city and a city that

people play in. Thus, the three core strategies that the Plan is organised around aim to

improve and diversify playful infrastructure in the city’s urban model, as well as stimulate

outdoor playful and physical activity among everyone from 0 to 99 by reversing the play

deficit and, finally, reinforce the social importance we attach to play.

We wish to emphasise the starting point of the Plan is to promote the exercise of the right of

children and adolescents to play. However, it is also conceived to ensure young people find

more attractive possibilities for doing physical and playful activity and getting together in

public spaces, and so adults and elderly people regain a taste for play and sharing time and

places for intergenerational play. Promoting active, everyday playful habits which give rise to

social life and help to transform the social setting is an opportunity for reversing social

problems such as sedentary lifestyles, child obesity, screen addiction, a lack of autonomy or

independence, individualisation and social isolation, or the lack of contact with nature and

green spaces, the high level of environmental pollution and road accident rates.

Taking into account a city which is lived and built from a perspective of play, and the benefits

of this, enables us to focus on often forgotten everyday needs such as playing, doing sport

and getting together in public spaces. At the same time, it helps to drive specific

improvements in the urban environment, making it greener, safer and calmer so it creates

more and better opportunities for play which, in turn, generates social life on the streets. In

this task of rethinking opportunities for outdoor play, the Plan provides new useful categories

for going beyond playgrounds and play areas and including in the planning and analysis the

city, based on the concepts of playful space, playful ecosystems and playful infrastructure. It

also considers school playgrounds and school surroundings as part of this playful

infrastructure in the city.

5

This Plan highlights the vital, human, everyday need to play and its capacity for transforming

the city through the sum of many small actions that impact on the well-being, health and

social life of its residents. And it does so by responding to the demands of children and

adolescents themselves, as well as those of educational leisure associations and the

educational innovation and renovation sector which, historically, have asserted the

significance of play and the importance of having time and suitable places for it. Likewise,

residents’ associations have also linked demands for dignifying public spaces to the need for

places to play and meet socially in the neighbourhoods.

Finally, it is envisaged that the City Council will work on this through its various service teams

and district plans and actions in order to promote and develop this Play Plan to the

maximum. However, decisive progress towards a more playablecity and one where people

play requires co-responsibility. Apart from the local authority, it calls on other players to

develop affinities and change their habits and priorities, ranging from social bodies to

commercial enterprises, as well as educational and health professionals, even the general

public, and especially adults.

6

2. Process of drafting the cross-cutting,

participatory plan

The Public Space Plan is based on and is one of the main measures envisaged in the

Barcelona plays things right Strategy, presented at the Full City Council meeting in February

2018. This is a joint initiative of two City Council areas – Ecology, Urban Planning and

Mobility, and Social Rights – working together on it, listening to social entities and the public

– children, adolescents and grown-ups – in 24 face-to-face working sessions involving over

400 people between March and December 2018. The Plan is based on an agreed time-frame

and criteria for the paradigm shift while also taking technical feasibility into account.

The Barcelona Institute for Children and Adolescents, as the City Council’s instrumental body,

was the one responsible for politically and technically coordinating the process, as well as

preparing the draft, where a cross-departmental approach and public participation were key

in providing the knowledge to ensure the rigour and quality of the contents.

A participatory process: political, technical and public spheres

The Plan’s premise is the need to rethink the places and opportunities for play that the city

offers all its citizens, especially children and adolescents, for diverse and inclusive play and

physical activity outdoors, thus helping to improve community life. This reflection was the

result of participation designed to gather the various views in the city on outdoor play and

physical activity. The process was enriched by the experience of various players, so the

resulting plan takes into account the different needs expressed on outdoor play.

The participatory process for drawing up the Public Space Play Plan was designed according

to the guidelines set out in the new Citizen Participation Regulation (October 2017). As laid

down in the regulation, a participatory process monitoring committee was set up to monitor

the drafting of the Plan comprising six of the city’s social entities.

The work carried out encompasses the political, technical and public spheres.

Political sphere:

In the political sphere a reference forum was set up comprising the political heads of the

government team (council executive) jointly led by two deputy mayor’s offices and including

the commissioners of the main local policies involved:

•

Deputy Mayor’s Office for Social Rights

•

Deputy Mayor's Office for Ecology, Urban Planning and Mobility

•

Commissioner for Ecology

•

Commissioner for Education, Childhood and Youth

•

Commissioner for Health and Functional Diversity

•

Commissioner for Sport

Two presentation and working sessions were also held with representatives of the municipal

political groups with City Council representation in order to present the time-frame

(horizon), process and contents of the Plan.

7

Technical sphere:

The technical work of municipal staff was done in five sessions covering two dimensions: one

with heads of the different City Council areas and institutes involved and the other with the

district technical representatives.

Initial exploratory sessions: with two objectives: 1) to present the conceptual

framework of the Play Plan and 2) to start identifying the key factors to be taken into

account. Some 70 service, area and district staff took part in the two sessions held.

Technical evaluation sessions: these sessions, involving some 60 professionals, were

held with the aim of measuring the feasibility and interest of the various action proposals

gradually shaping the Plan’s operational content.

o

Session with the Municipal Institute for Persons with Disabilities and the Citizen

Agreement for an Inclusive Barcelona’s Independent Living and Accessibility

Network.

o

Session with educators from Municipal Children’s Leisure and Play Centres.

o

Session with city district technical managers.

Public sphere:

The process in the public sphere sought the participation of entities involved in the city’s

participatory bodies, and social organisations, businesses and reference persons linked to the

play sphere and the various uses of public space, as well as individual citizens, both children

and adults. Half the working sessions of the entire process were in this sphere (11 out of 24).

Initial exploratory session: Involving some 30 representatives of social entities in the city

and experts, with two objectives: 1) to present the conceptual framework of the Play

Plan and 2) to start identifying the key factors to be taken into account.

Sessions for constructing the desired time-frame to 2030: The aspects to be considered

served as the starting point for constructing the time-frame and doing it jointly in four

working sessions involving the various consultative bodies in the city most closely linked

to the issues concerned, with some 50 people taking part.

o

Session with the Municipal Council for Social Welfare and the Citizen Agreement

for an Inclusive Barcelona

8

o

Session with the Municipal Sports Council

o

Session with the Municipal Schools' Council

o

Session with the Barcelona Youth Council

Face-to-face theme-based sessions: with the aim of gathering ideas and possible actions,

five sessions, each with a specific theme and open to the public, were organised. They

attracted around 100 people with a variety of profiles and links to the subject area, which

enriched the creative process and reflection on play in public spaces.

Barcelona Decidim Platform: a two-month window gave anyone interested the chance

to submit their suggestions to the digital participation platform but the level of

contributions was very low.

Children’s feedback: in order to get the benefit of children’s expertise on the lead

projects, a working session was held with some 40 fifth- and sixth-year primary school

students at Escola Pegaso. Also included were the reflections contributed by 200 children

aged 10 to 14 from five schools and an educational recreation centre over the course of

the Parc Central de Nou Barris and Parc de la Pegaso co-creation process.

9

A cross-cutting process: three municipal areas and the districts

The complexity and scope of the Public Space Play Plan’s objectives required an integrated,

cross-cutting working logic throughout the municipal organisation that incorporated a range

of perspectives, both those of deputy mayor’s offices as well as departments and municipal

institutes. Thus the process was led in a cross-cutting, cross-departmental fashion, on a

political as well as a technical level. The political figures and bodies mentioned above and

linked to the policies on green spaces, urban planning and mobility, social rights, health,

functional diversity, sport, education and youth. On the technical side, a cross-sectoral

committee was set up to draft the Public Space Play Plan comprising services from three

areas – Ecology, Urban Planning and Mobility, Social Rights, and Citizens' Rights, Participation

and Transparency – and from the districts, all coordinated by the Barcelona Institute for

Children and Adolescents.

The Cross-sectoral Committee for Drafting the Public Space Play Plan, comprising 35 people

had 5 meetings and served as the monitoring and technical validation forum for the process

proposals and Plan contents, besides working on identifying players and actions to bear in

mind and exploring synergies to give the Plan consistency and scope. This cross-cutting work

made it possible to bring a range of expertise and perspectives together and to start from

experiences already under way in the districts, which the Play Plan highlights, redirects and

gives new meanings to or scales up to a city level.

Public presentation at the Play and City Conference

The Play and City Conference, held at the Barcelona Contemporary Culture Centre on 6

February 2019, opened a discussion on the social importance of play. It was also where the

Public Space Play Plan was publicly presented to 400 people from various spheres and

organisations: educators, architects, landscapers, companies making games and play

equipment for playgrounds and play areas, and municipal technical staff from Barcelona and

other cities.

10

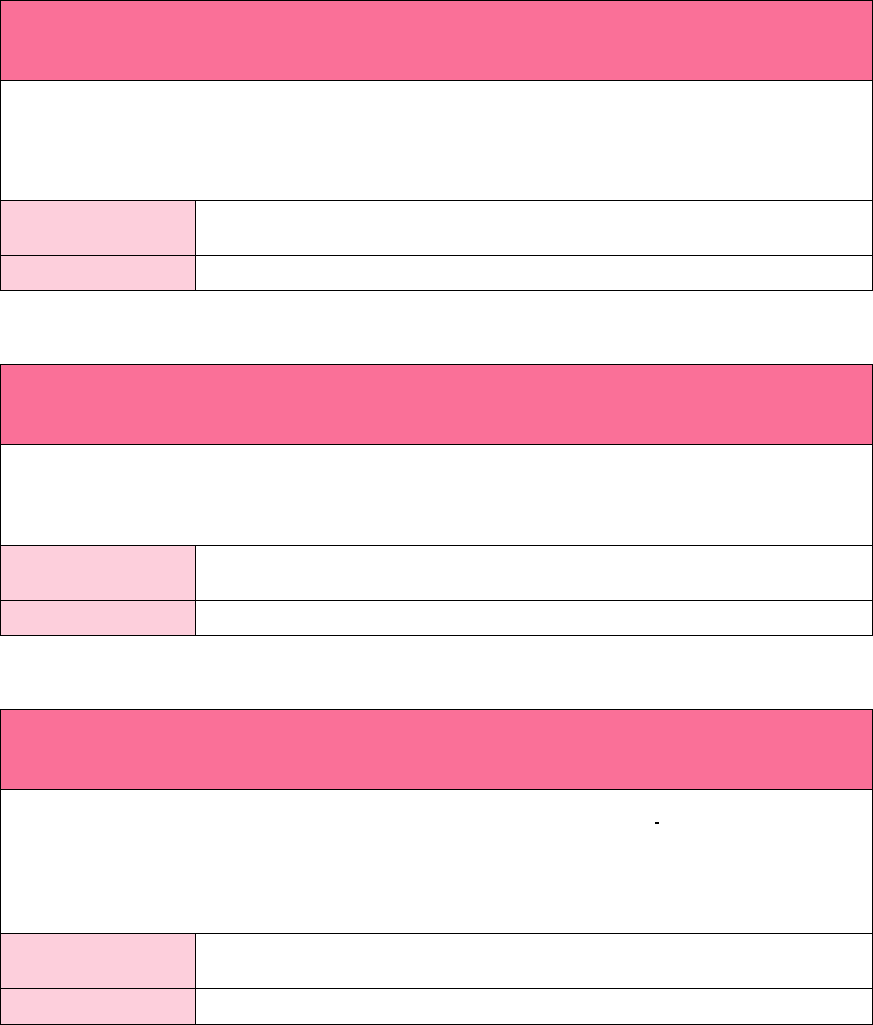

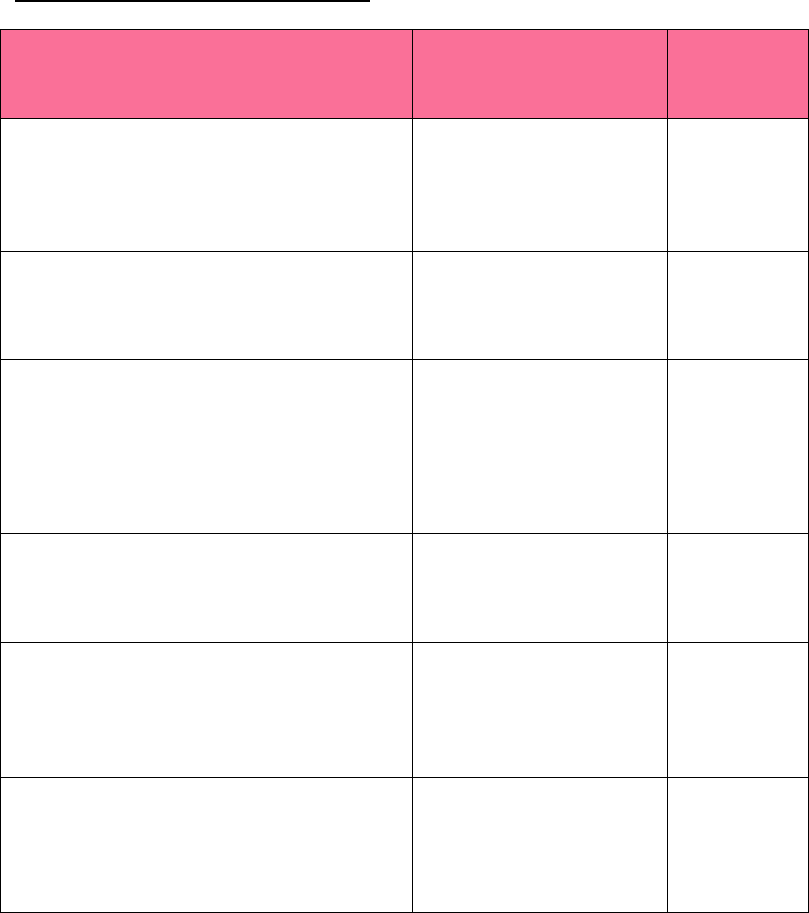

a

n

d

Cross-cutting political guidance

Deputy Mayor’s Office for Social Rights

Deputy Mayor's Office for Ecology, Urban

Planning and Mobility Commissioner for

Ecology

Commissioner for Education, Childhood and

Youth Commissioner for Health and

Functional Diversity Commissioner for Sport

Cross-cutting Play Plan drafting committee

Dir. Urban Model, Dir. Environment and Urban Services, Dir. Conservation and Biodiversity, Dept. Urban

Prospective, Dir. Communication and Participation Ecology, Dir. Communication Social Rights, Dir. Children,

Youth and Elderly, Dir Community Action, Dir. Citizens' Rights and Diversity, Dir. Active Democracy, Districts,

Dept. Gender Mainstreaming, municipal institutes: IMPJ, IBE, IMPD, IMSS, IMEB, ASPB, BR, IIAB

Public Space Play Plan participatory process monitoring committee

Formed by people from social entities

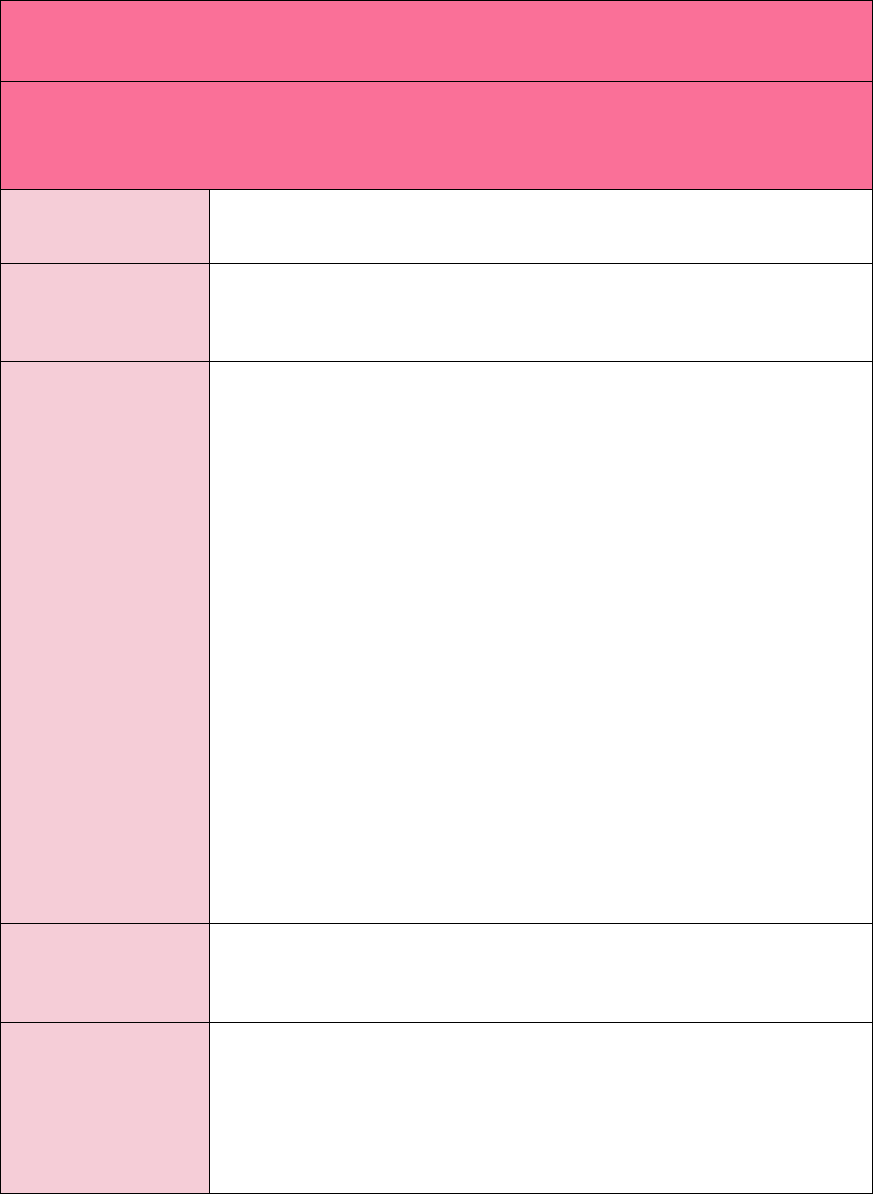

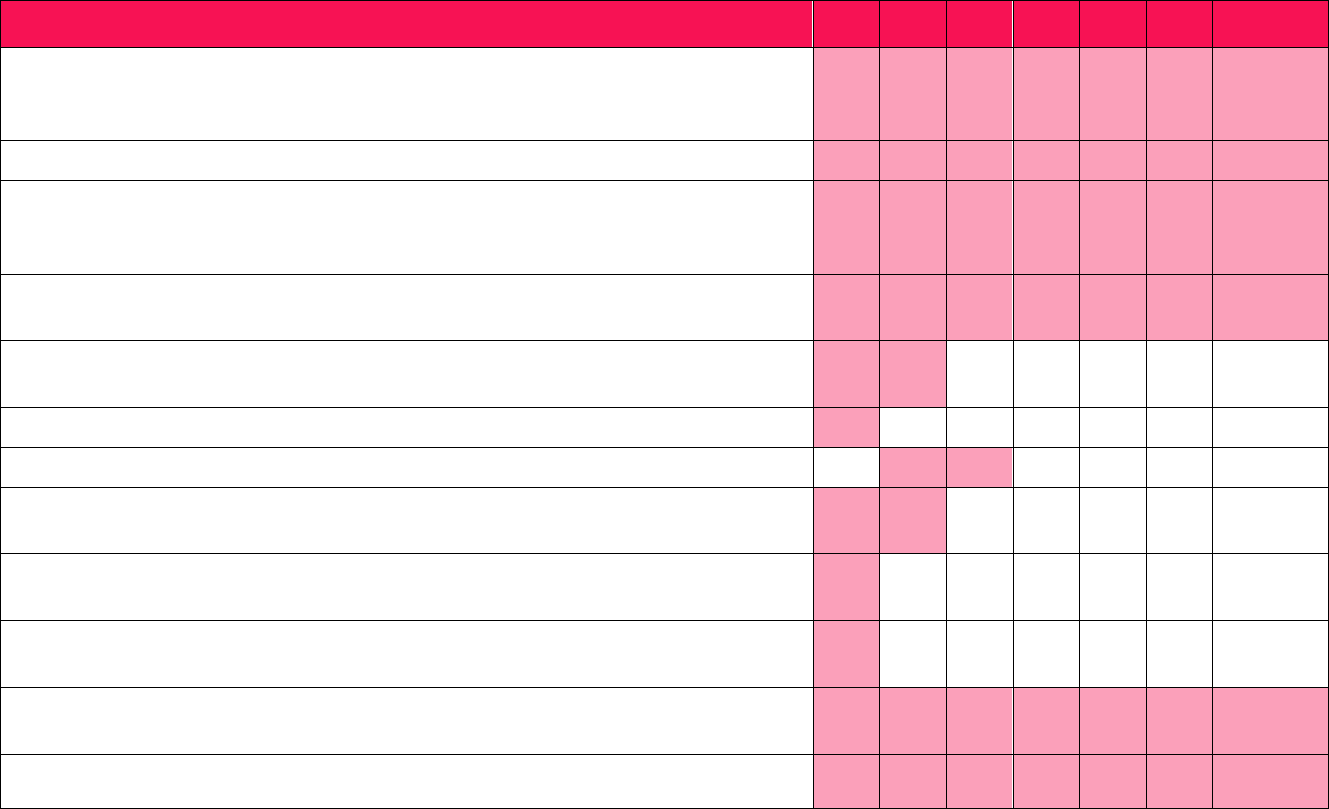

Outline of the Public Space Play Plan drafting process

Play and City Conference Presentation of the Public Space Play

Plan

6 February 2019

Municipal areas and

institutes

Districts

Social entities and

experts

Municipal Social

Welfare Council and

Citizen Agreement

Municipal Sports

Council

Municipal Schools'

Council

Barcelona Youth Council

5 F2F theme-based

sessions

Sessions with

children

Decidim

Sant Andreu Neighbourhood Council

monitoring session Indústria Gardens

information session

Districts

Professional children's

play centre

Accessibility and

Independent

Living Network

Municipal political

groups

Barcelona

plays things

right

Strategy

February

2018

Sessions for

jointly

constructing the

desired scenario

to

consultative

and

participatory

bodies June-

September

Public

evaluation

sessions

October-

November 2018

Technical

evaluation

sessions

September-

December

2018

Initial

exploratory

sessions

March-May

2018

Political

evaluation

sessions

July

2018

January

2019

11

3. Frameworks and reasons

3.1 Frameworks: legislation, commitment,

plans and strategies

The Public Space Play Plan - Horizon 2030 arose from the need to establish a new vision of

play in the city and interacts with a number of earlier frameworks, which are realised in one

way or another or which it helps to catalyse. The various frameworks it intersects with,

whether legislation, commitments, plans or strategies, Catalan or international, are explained

below.

3.1.1

Starting point Barcelona Plays Things Right Strategy

The Barcelona Plays Things Right Strategy: towards a public space play policy was presented

as a government measure at the Full City Council meeting on 23 February 2018. Its purpose is

to compile actions that have already been, or are scheduled to be implemented before the

end of the term of office in six lines of action. These include producing a Barcelona Public

Space Play Plan as an instrument for identifying the core strategies and objectives, and for

planning actions in the short, medium and long term to move towards a play policy in public

spaces.

3.1.2

International agenda and legislative framework

The Play Plan is part of and takes into account both international and Catalan agendas and

benchmark legislation.

UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development Goals

As regards the political agenda, in the international sphere the Plan contributes towards

progress on the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) agreed by the

international community at the United Nations. There are 17 SDGs and the Play Plan works

on Goal 11, which is for cities and human settlements to be inclusive, safe, resilient and

sustainable and, especially, on the target: “By 2030, provide universal access to safe, inclusive

and accessible, green and public spaces, particularly for women and children, older persons

and persons with disabilities” (11.7). And, in relation to actions linked to schools working for

the goal of “building and adapting school facilities so they meet the needs of children and

persons with disabilities, take into account gender issues, and offer safe, non-violent,

inclusive and effective learning environments for everyone” (Quality education 4.7a).

12

UN Convention on the Rights of the Child

With regard to international treaties, this Plan is a specific application of the Convention on

the Rights of the Child, Article 31: “...the right of the child to rest and leisure, to engage in

play and playful activities appropriate to [their] age and to participate freely in cultural life

and the arts” (Art. 31.1). Likewise, all levels of government in States Parties “shall respect

and promote the right of the child to participate fully in cultural and artistic life and shall

encourage the provision of appropriate and equal opportunities for cultural, artistic,

recreationa and leisure activity” (Art. 31.2).

The Plan’s focus and specifications are strongly inspired by and take into account the

interpretation and recommendations of the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, in its

General Comment N. 17 (2013) which spells out the conditions for the gradual fulfilment of

the right to play and leisure embodied in Article 31.

UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities

With regard to children’s participation in cultural life, recreational and leisure activities and

sport, Article 30 of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities establishes

that public authorities “must ensure that children with disabilities have equal access with

other children to participation in play, recreation and leisure and sports activities, including

those activities in the school system”.

European Charter for Safeguarding Human Rights in the City

The Plan also respects the European Charter for Safeguarding Human Rights in the City,

which establishes that “local authorities shall guarantee quality leisure spaces for all children

without discrimination” (Art XXI.2).and also that “administrations have to encourage physical

and sports activities as a healthy habit” (Article 58.4).

Catalan Rights and Opportunities in Childhood and Adolescence Act

The paradigm shift with regard to citizenship and the human rights of minors, which the CRC

(Convention on the Rights of the Child) represented, is reflected in the Catalan Rights and

Opportunities in Childhood and Adolescence Act (14/2010 – LDOIA). This establishes that

“children and adolescents have a right to move around in, enjoy and socially develop in their

own urban environments”, that “ the public authorities must enable the development and

autonomy of children and adolescents in a safe environment”, and that “municipal urban

planning must plan and shape public spaces taking into account the perspective and needs of

children and adolescents” (Art. 55).

As regards areas for recreation and play, the LDOIA envisages that “urban planning must

provide for suitable public playful areas and spaces so children and adolescents can enjoy

play and leisure there (...), taking into account the diversity of play and leisure needs in the

child and adolescent age groups. When designing and deciding the layout of these spaces,

local councils must listen to the opinion and enable the active participation of children and

adolescents”(Art. 56).

Finally, it should be pointed out that the LDOIA specifies that “there has to be a guarantee

that children and adolescents who have a physical, psychological or sensory disability can

access public playful areas and spaces and enjoy them, in accordance with current legislation

on accessibility and the removal of architectural barriers.” (Art. 56).

13

3.1.3

City commitments, plans and strategies interlinked with

the Play Plan: a plan that catalyses

The cross-cutting nature of the Plan means it is essential to bear in mind strategies, plans and

commitments on various matters. At the same time, the Plan itself envisages actions that

reinforce and contribute to achieving two city strategies, five plans, two city and two district

government measures, and a citizen commitment that are specified below:

Barcelona Strategy for Inclusion and Reducing Social Inequalities 2017-2027

This is a working framework shared between the City Council and social entities for reducing

social inequalities and there is a link with the Play Plan in “promoting and ensuring equal,

universal access to leisure, cultural, sports and play activities, especially among children and

teenagers (Goal 2.6). Also with regard to the goal of “ensuring the city is a living space by

offering public spaces and facilities with diverse uses that encourage relations with others, as

well as positive community life and intergenerational and intercultural relations” (Goal 3.6).

Citizen Commitment to Sustainability 2012-2022

This social agreement is spelt out in Barcelona’s Agenda 21 with 10 goals and the Play Plan

contributes specifically to Goal 2: “Public space and mobility: from the street for traffic to the

street for living in” and the specific action line that proposes reclaiming the streets for

people, generating a welcoming, traffic-calmed space, encouraging a culture of shared public

space and promoting and prioritising life on the streets as places for people to meet, spend

time together and play.

Barcelona Green and Biodiversity Plan 2012-2020

This defines the challenges, goals and actions with regard to conserving green spaces and

biodiversity and how the city’s population is aware of them, enjoys them and takes care of

them. Its five goals includes Strategic Line 9: “fostering green spaces as places for health and

enjoyment as well as promoting citizen involvement in their creation and in the conservation

of biodiversity”. Among others, this line of action includes two of the main ones that the

Public Space Play Plan responds to: “Improve and diversify children’s play areas by involving

schools, associations and the community” (9.3) and “Increase and improve the number of

playful and health facilities offered in parks” (9.2).

Climate Plan 2018-2030

This plan compiles a series of action to achieve three goals: reduce CO2 emissions by 45%,

increase urban green spaces by 1.6 km2 and reduce water consumption to less than 100

litres per inhabitant per day. It also responds to the commitment the city assumed by signing

the Global Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy. Its Action Line 3 on preventing

warming includes actions such as prioritising cooling actions, generating more shaded areas

or creating water gardens (accessible fountains, lakes, swimming pools, etc.) that are

included in the Play Plan.

Child and Citizen Focus 2017-2020. Plan for growing up and living childhood and

adolescence in Barcelona

This is the framework for planning and mainstreaming the main policies that affect children

and adolescents in Barcelona. “Participation in social and community life. Participation

rights” includes Challenge 9, which says “Provide more and better opportunities for playful

and inclusive play in public spaces”. It also includes the playable city measure.

14

Adolescence and Youth Plan 2017-2021

This plan seeks to guarantee all the rights of young people, making adolescents and young

people the protagonists of their own lives and players in social change. The main goals that

coalesce with the Play Plan are to: Promote diversity in physical and sports activity with

regard to both the types of activity and profiles of young people (Strategic Line 3.2).

Facilitate and legitimise the use of public space by young people, and foster the co-design

and co-management of public spaces and facilities with the participation of young people

(Strategic Line 4.3).

Guarantee and Improve the Influence of Grassroot Educational Associations in the City.

One of the main aims of this government measure (May 2018) is to facilitate the presence in

and use of public spaces by educational associations, and specifically includes as one of it

actions “to incorporate steps promoted by and called for by leisure education entities in the

Public Space Play Plan, such as facilitating playful use of streets, squares and parks close to

their premises” (Action 20).

Demographic Change and Ageing Strategy: a city for every cycle of life 2018-2030

This government measure is designed to address the demographic change that is affecting

every sphere of life and people’s life cycles and explicitly refers to the Play Plan: “Foster an

intergenerational perspective in children’s play in the city. Monitor the Public Space Play Plan

to ensure the intergenerational perspective is considered when designing play spaces in the

city.

Universal Accessibility Plan 2018-2026

The goal of this Plan is to put people first and ensure they can fully exercise their rights,

irrespective of whether they have some kind of disability or functional diversity. Universal

accessibility and universal design make it possible for everyone to live in the urban setting in

equal conditions. The Plan provides for a line of analysis and proposals for public spaces, with

a specific analysis of accessibility to play areas and green spaces and, more specifically, to

carrying out a diagnosis of accessibility to public spaces in the city: streets, parks, children’s

play parks and beaches (Goal 10).

Gender Justice Plan 2016-2020

This is a tool for promoting equality between men and women and its goals that need

highlighting include combating gender roles that affect women’s health; highlighting women

and promoting their participation in sport; making progress on introducing a co-education

model in the city’s schools; driving a city model that responds to the needs and experiences

of everyday life, improving the perception of public safety and empowering women in public

spaces.

Urban Planning with a Gender Perspective

This government measure includes a package of measures for integrating a gender

perspective into all urban planning policies to achieve a fairer, more equal, safer city without

barriers. With actions that include, for example, reviewing with a gender perspective the

items that make up all the urban furniture installed in public spaces (benches, lamps, bins

etc.) as well as their layout in the places where they are located, bearing in mind people’s

needs, depending on the stage of the life cycle they are in. (Action 3.1.4)

15

Gràcia Squares, Public and Community Space

This Gràcia district measure includes action to liven up the squares with playful-educational

activities and the swap the leather ball for a foam ball programme in collaboration with local

retailers, inspiring actions that can be scaled up to a city level.

Let’s Fill School Surroundings with Life

This Eixample district measure is a starting point for encouraging action required across the

city, because it proposes improving school surroundings so they become habitable places,

community spaces, an extension of the school and a place for play, greenery, and

neighbourhood life and history.

3.2 Reasons: Why an outdoor play plan for the

city of Barcelona?

Four main reasons for the Public Space Play Plan

In the context we have just outlined, the City Council has decided to construct policies

around play in public spaces for four main reasons:

16

3.2.1

Because children have a right to play and leisure

“Rest, play and leisure are just as important to a child’s development as nutrition,

housing, health care and education”

(General Comment No. 17 of the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child)

As has been pointed out in the previous section, both international human rights law in the

Convention on the Rights of the Child and Catalan law in the LDOIA recognise the importance

of play in the development of children and adolescents. And this is the reason why it has

been recognised as a specific human right of this life stage since 1998. “Play has to be

understood as an essential element in the growth and maturity of children and adolescents.

(...) has to help psychomotor development at each developmental stage (LDOIA Art. 58.2)

The right to play is often referred to as one of the forgotten rights of childhood, as it is

undervalued in relation to others, despite the fact that the UN Committee on the Rights of

the Child (GC No. 17/2013) reminds us of the importance of play in achieving the maximum

development of children and adolescents. It also point out that “when there is investment in

leisure, it usually goes to organised activities, but it is just as important to create spaces and

times so children can devote themselves to exercising their right to spontaneous play, leisure

and creativity, as well as promoting social attitudes that support and foster these activities.”

Likewise, it warns of situations of poverty or inadequate living standards that can deprive

children or condition the exercise of this right, so it needs to be taken into account in housing

policies and policies on access to public spaces for children with fewer opportunities for play

and leisure at home.

As regards identifying the obstacles to moving forward on the right to play, the United

Nations identifies the following nine aspects that pose social challenges around the world

and need to be borne in mind:

1)

Lack of awareness of the importance

of the right to play and leisure time.

2)

Unsuitable play environments, due to

their insecurity.

3)

Resistance to children using public

space due to the growing

commercialisation of public space and

low tolerance of their presence.

4)

Lack of diverse community spaces for

play and leisure for all ages.

5)

Imbalance between risk management and safety.

6)

Lack of access to nature.

7)

Demands of academic success.

8)

Excessively structured and programmed timetables.

9)

Disregard for the right to play in child development programmes.

In order to promote the progressive exercise of the right to play, this United Nations

Committee reminds us of the four governments obligations, including local governments, to:

17

1.

Plan ideal environments, facilities and play and leisure spaces, bearing in mind the

best interest of the child

Availability of parks, community centres, sports facilities and safe inclusive play

areas accessible to all children and adolescents.

Creation of a safe living environment where children can play freely, designing

areas that give priority to people who are playing, walking or riding a bike.

Access to green areas, big open spaces and nature for play and leisure, with safe,

affordable and accessible transport.

Implementation of traffic-related measures such as speed limits, pollution levels,

crossings near schools and so on to guarantee the right of children to play in their

community without danger.

2.

Pay special attention to girls, children in situations of poverty, boys and girls with a

disability or in a minority.

3.

Offer children and adolescents opportunities to participate and be heard so their

opinions are taken into account in drawing up policies and strategies linked to play

and leisure, creating parks and designing environments suitable for children. As well

as moving forward on making children co-responsible.

4.

Compile data, assess and carry out research on the range of public space uses in the

everyday lives of children and adolescents in order to show how public authorities

promote their rights as a whole.

Guaranteeing the right to play means looking out for children’s well-being, an important

issue for city residents because 4 out of 10 Barcelona residents have a direct interest in it,

being children or adolescents themselves (15% of the population are aged 0 to 17) or

because they live with and look after them (23% are adults with minors in their charge).

Finally, children and adolescents themselves are concerned about the possibilities of playing

in public spaces. This is shown through various participatory processes held in the city at

different times and in different formats over many years. Examples include the Barcelona

Children’s Public Hearing in 2001, the Barcelona`s Children Speak programme, Laia’s Speech

at the St Eulalia festival and their participation in Child Focus. In all of these, they have

expressed concerns and proposed improvements so the city might have an ideal and

attractive environment for play. They have called for environmental improvements, including

less traffic and more green spaces, as well as creating more pleasant and nicer

neighbourhoods with wide streets and pavements or installing attractive play features

different from the usual ones, plus more time to play and more possibilities to take part in

designing the city.

18

3.2.2

Because play and physical activity improve

everyone’s well-being and physical and mental

health

“We don’t stop playing because we grow old, we grow old because we

stop playing”

G.B. Shaw.

Playing outdoors implies active play and doing a physical activity which stimulate motor skills

and abilities that are essential for good physical development and also, implicitly, healthy

psychological development, from both a personal and a social point of view. However,

although play responds to a vital need in children to explore their environment and

themselves (their body, their emotions and their limits), the situation in Barcelona is that 1

out of 4 children never play in the park or on the street, with a significant gender differential.

Moreover, increasing obesity and overweight, which affect 3 out of 10 adolescents and are

caused by screen addiction and sedentary lifestyles, among other factors, are growing

problems in today’s society. The physical inactivity indexes in the city are very high and there

are worse evaluations of the health of teenagers living in poor neighbourhoods compared to

high-income neighbourhoods (FRESC-ASPB 2016). Thus, outdoor play is not just a response to

children’s playful needs, it is also key for dealing with the challenges posed to physical health,

with special emphasis on children living in low-income neighbourhoods and young and older

girls.

Another aspect that needs highlighting is the emotional well-being that play brings, especially

when it is done with autonomy, in contact with nature and the outdoors, experimenting and

learning from managing risks and controlling emotions. In that sense, not playing or not

having the possibility to play different games affects skills such as emotional self-control or

facing and taking decisions, resilience and personal autonomy. The play deficit, especially as

regards free play, shared play and play with challenges, has negative consequences for well-

being and mental health, no small matter if we take into account that 1 out of 10 adolescents

in the city are highly likely to have mental health problems (FRESC_ASPB 2016). As the

Barcelona Mental Health Plan notes (in its priority area of childhood and adolescence), good

mental health during childhood helps the processes of learning, interpersonal and family

relationships, achieving goals and the capacity to face life’s difficulties, including the

transitions to adolescence and adult life.

In addition, the lack of autonomy in childhood due to overprotective adults means less

capacity for taking decisions, settling disputes and managing risks. Children themselves

provide data in that respect when they say they are not really satisfied with the autonomy

they have at home, at school or on the streets (EBSIB‐IIAB 2017). This loss of autonomy is

linked to the limited leeway that adults give children to enable them to develop free, self-

regulated play by themselves, thus restricting vital learning opportunities.

What we call motor play in childhood becomes physical activity in adolescence, youth and

adulthood. In Barcelona, 30% of the adult population do no physical activity, either outdoors

or in sports facilities (EBSIB‐IIAB 2018), especially people on low incomes, women, over-65s

and foreign nationals. As in the case of children, sedentary lifestyles are a reality among

adults too and that has implications in terms of worse health and quality of life. The benefits

that physical activity brings throughout our entire life cycle are clear but we must not forget

that play also brings well-being and pleasure at any age. Playing allows adults to enjoy the

moment and live in the present in the same way children do. It also means losing the fear of

looking ridiculous, putting forgotten skills to the test or trying them out again, recalling and

19

recovering games shared in childhood.

A playful attitude and a taste for play in young people, adults and elderly people helps them

to tackle everyday situations in a positive spirit, which is so necessary for good mental health.

Moreover, shared play develops links and affinities in a unique way in both adults and

children. The value of shared play lies in the fact that it is a unique activity for sharing, one of

the best forms of communication, a very special way of letting children know they are very

important, because we share with them what they like and need most: to play.

3.2.3

Because play brings people together and community

life is enriched

“Children playing in the street is a good indicator of the quality of community life”

Jan Gehl, urbanist

Barcelona is a densely populated city where public space is scarce and too much is given over

to motor vehicles (estimates put the figure at 60% of the urban environment), so what is left

for pedestrians and citizen uses is limited and much less. These days, the social meeting

function that streets have always had has very much been lost, having to a large extent and

almost exclusively been replaced by the travel function, for both adults and children. In other

words, there is not enough space and that needs to be improved so streets are suitable for

people to meet and play. That is how the city’s 10 to 12 year-olds put it. They are not

satisfied with the spaces for playing and enjoying themselves in their neighbourhood (EBSIB‐

IIAB 2017). The fact of having children playing on the streets not only has consequences for

the play deficit children face, it also reduces the knock-on effect of encouraging social life

around play. Because it is precisely when there are children playing in public spaces that they

become places for informal gatherings, especially, but not only, of parents accompanying

children but also of young and elderly people or other local residents.

The conditions in the play setting also determine the time that adults stay and, therefore, the

time children play, as well as whether people spend time and socially relate in a public space.

Despite all the measures being adopted, urban planning in the city is still a long way from

universal accessibility and there are few signs of a gender focus. Among other reasons, that is

due to the lack of attention to everyday needs, with urban furniture and features that make

public spaces habitable and encourage people to stay (lighting, benches, tables, play

equipment, toilets, fountains and so on). Currently less than 1 in 10 recreation spaces in the

city have table-tennis tables and only 8.5% of green spaces have public toilets.

There are many ways of experiencing public spaces. Accompanying children playing on the

streets is one, while doing physical activity or stopping to chat with neighbours are others.

Community life in the city requires recognition of the various uses of public spaces but

conflicting uses are a reality. To move forward, so these spaces do not exclude certain public

activities or groups, we need to think about making play area settings more accessible,

accommodating a social mix with people from different backgrounds and cultures in a city

where practically 1 in 4 inhabitants was born in a foreign country (Idescat 2017).

20

To include the different groups in community life, we also need to put the emphasis on

reducing the strong gender bias of urban spaces, as well as on the discomfort generated by

the presence of young people in public spaces and which often leads to their expulsion. For

that reason, we need to stress the importance of reclaiming public space as a place for

people to relate and socialise, facilitating access to it and legitimising the uses adolescents

and young people make of it, in harmony with the rest of the population. Public space has to

be a space for relating and shared experiences that belongs to everyone, in all their diversity

in terms of age, gender, social and cultural background and functional diversity.

Finally, a greater presence of people and more life on the streets also increases the

perception of public safety and helps to combat individualisation and social isolation,

promote personal autonomy and foster intergenerational relations.

3.2.4

Because quality play environments help to green,

calm and make the urban environment safer

Barcelona is still a city that lacks urban green spaces, despite the efforts made in recent

decades. Each city resident has 6.6 m

2

of green space (not counting the Collserola hills) and,

in the districts of Eixample and Gràcia, the figure is way below the city average (1.85 m

2

and

3.15 m respectively). In order to mitigate the effects of climate change, Barcelona has made a

commitment to increase green space by 1m

2

per inhabitant by 2030. This green deficit

aggravates a big problem the city faces, namely the alarmingly high level of environmental

pollution, both air and acoustic, which makes people’s health worse, especially in the case of

children and the elderly. Traffic in the city, where there are still too many private motor

vehicles, has a very negative effect on the healthy development of city residents, decreases

road safety and increases road accident rates. This situation also makes safe, independent

children’s mobility as autonomous pedestrians more difficult and, at the same time, limits

the public space available due to wheeled traffic and parking for private vehicles occupying

road space. This applies to the whole city, but especially and worryingly around leisure spaces

and schools, so the aim is to define the LDOIA’s provision regarding the obligation of local

authorities to promote “safe access for children and adolescents to schools and other centres

they frequent” (Art.55.5.c).

The scant contact with green spaces and nature takes on special significance with regard to

children’s play, as it reduces the possibilities for and benefits of play in natural surroundings.

In that regard, half of all play areas and playgrounds are not in green spaces, so there is

considerable room for improvement and a need to increase green spaces and natural

surroundings, specifically and importantly, around play areas, playgrounds and leisure

spaces, as well as school playgrounds and surroundings. In addition, moving towards a

playable city implies securing more public space for play and improving it with diverse

elimination measures, temporary road closures and traffic-calming, above all, around leisure

spaces and school surroundings.

21

4. Paradigm shift: 3 layers and 7 criteria for a

playable city

The vision and goals for achieving the Play Plan mean a paradigm shift in the place given to

outdoor play in the urban environment as a whole. Therefore, a conceptual framework has

been created specifically for Barcelona, to rethink the outdoor playful opportunities. This

framework is based, primarily, on the collective and interconnected benefits of play, not only

for children but for all the city’s citizens, as well as for its potential to generate community

life and provide an opportunity for improving the urban environment (see Section 3.2 for the

reasons). Secondly, the conceptual framework builds a new category of city recreation

infrastructure in three layers and, thirdly, it establishes quality criteria for play in order to

guide space design and take a more playable city into account at the planning stage.

4.1 The collective benefits of play

“Play is the highest form of research”

Albert Einstein

Play is an end in itself for the pleasure it gives, a vital human need and a recognised right of

children and adolescents because of its importance for their development. The UN

Committee on the Rights of the Child defines it as “any behaviour, activity or process started,

controlled and structured by children themselves that can take place anywhere and when

they have the opportunity”. Play, therefore, involves the exercise of autonomy and physical,

mental and emotional energy, adopting infinite forms that adapt and change over the course

of childhood and which can continue into and vary at all the stages of the life cycle. Playing is

linked to fun, uncertainty, challenge, creativity, flexibility, freedom and non-productivity. All

these factors together constitute the main reason why play is an activity which provokes

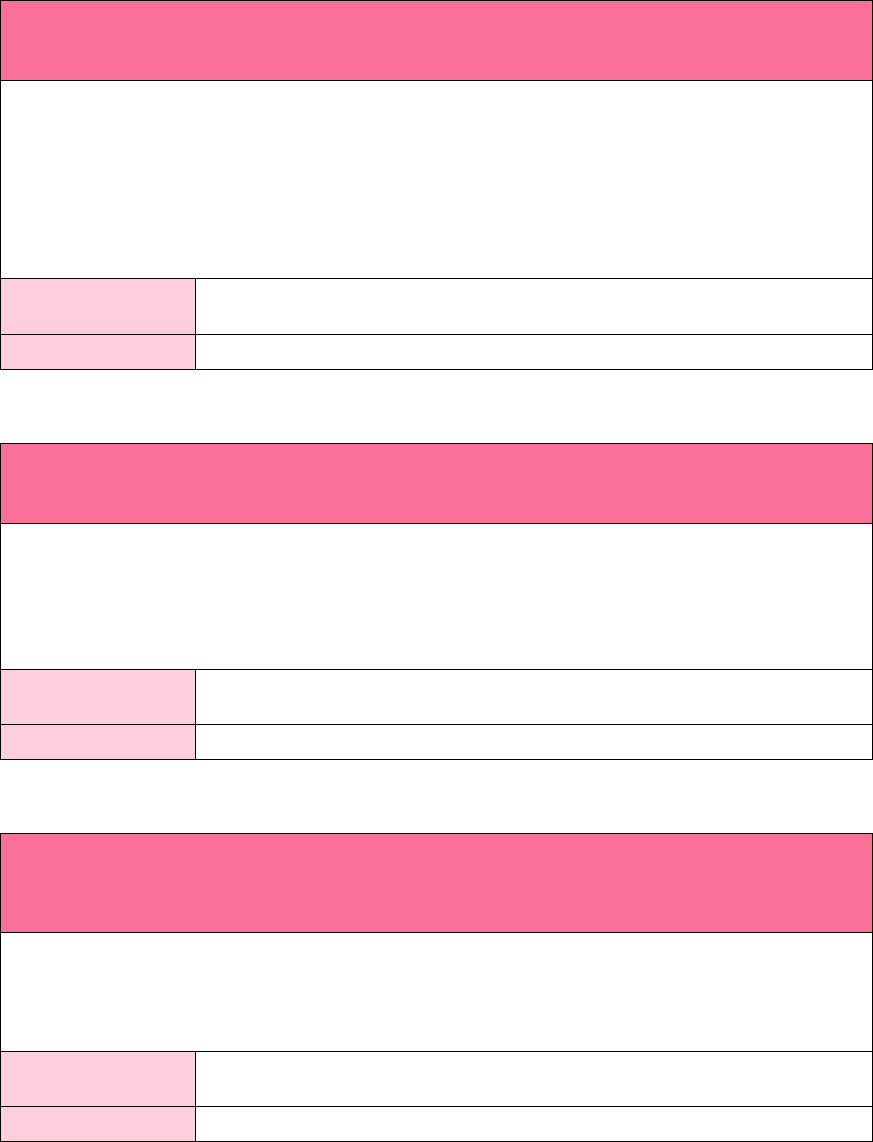

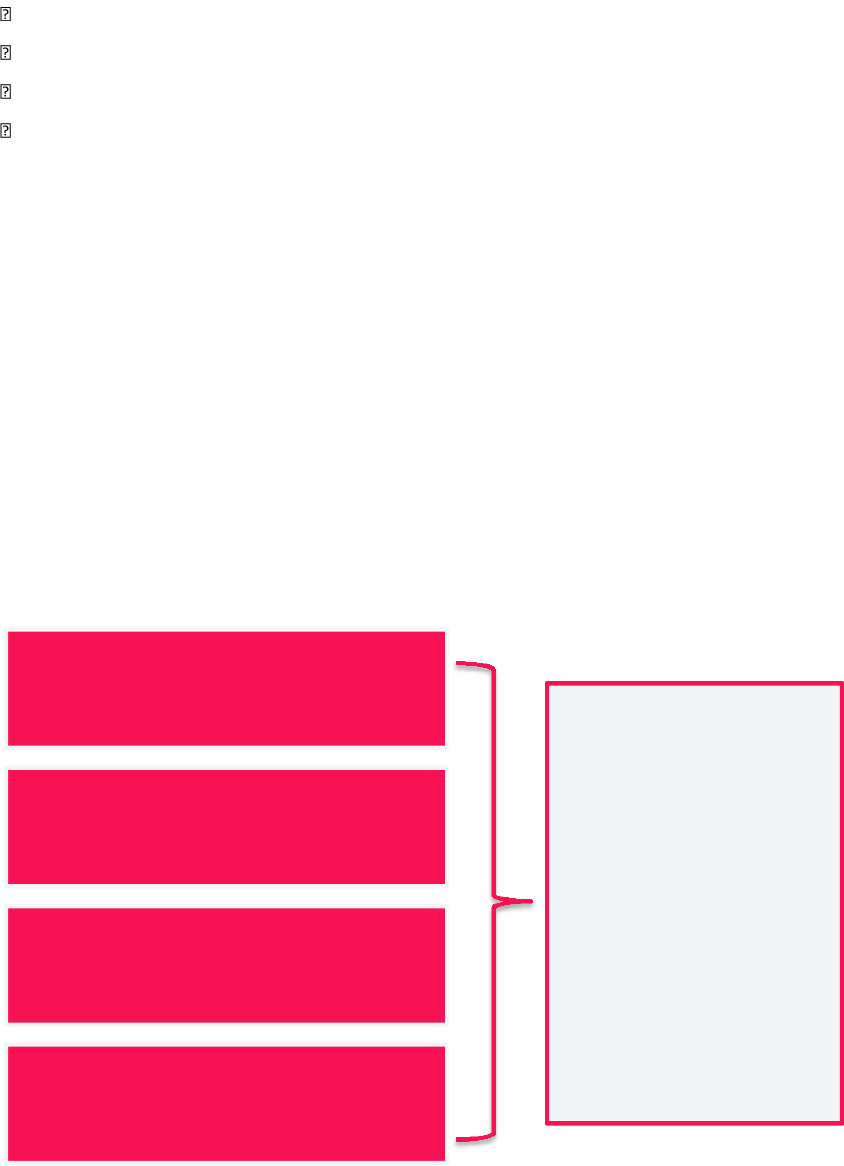

Benefits of

play

Playful

infrastructure

3 layers

7 quality

criteria

22

enjoyment and pleasure. It is a voluntary activity that responds to an intrinsic motivation and

becomes an end in itself, so all the benefits that play brings are positive collateral effects that

need to be fostered, but it is also very important to be clear that they are not the aim during

play. We do not play to learn or because it is healthy, but to have a good time.

There are social and emotional skills that are vital for life which are better learnt playing

because play is experienced in the body and through emotions and play means action,

experience, involvement and participation, which are key strategies for meaningful learning.

Playing is a very serious activity, even though it takes place above all in a fictional framework,

where people concentrate to put into practice all their abilities and resources to achieve the

objective set. In other words, it implies accepting and overcoming challenges. While playing,

people voluntarily put into action their capacity to conquer and excel,accepting not only

success but also failure, which is key to developing confidence and self-esteem and managing

frustration.

Adults have a vital role in guaranteeing the right to free, stimulating, creative and positive

play by putting various quality spaces, free time, materials and friends at children’s disposal

and letting them play. However, in general, adults who look after children and adolescents

do not always play a positive role in encouraging play, for three main reasons, among

others. One is because they organise a daily agenda for their child or adolescent that is

packed with activities and obligations that leave very little free time for them to organise

themselves. A second is their aversion to risk, which leads them to be over-protective, giving

children little or no scope for facing challenges and managing risks, and the third is because

they do not vary the types of games enough, thus reducing the range of play experiences.

4.2 The 3 layers for rethinking and

promoting more and better play

opportunities in public spaces

“We have to accept that the most suitable places for playing are the real spaces in the city:

steps, building courtyards, parks, squares, streets,

monuments... Everything possible needs to be done so everyone

can use them, children too”

Francesco Tonucci

The conceptualisation and design of this Plan, which is intended to improve and diversify the

opportunities for play everywhere and in all the city’s public spaces, offers a broad view not

only of places where play is envisaged but also where people play, more or less

spontaneously, fortuitously and occasionally. Consequently, our work has been based on the

concept of recreation infrastructure, with the aim of having a category for analysing the new

paradigm that includes the different types of outdoor urban spaces with possibilities for play,

rather than just intensity of playful use and intentionality of design for play. Analysing the city

from this perspective of recreation infrastructure enables us to clearly identify three layers

for improving and maximising playability that act as concentric circles and which, together,

make up the urban recreation infrastructure.

23

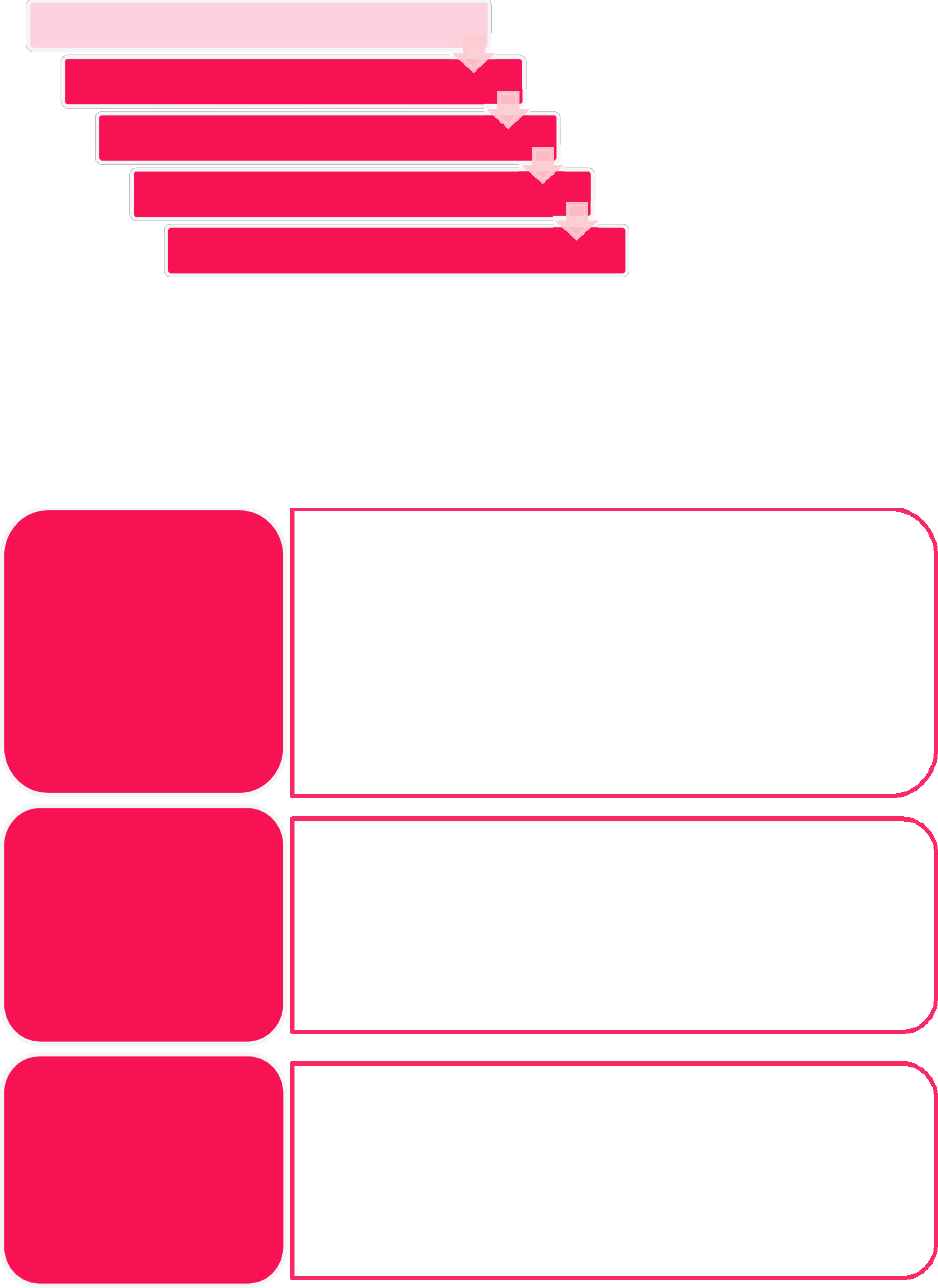

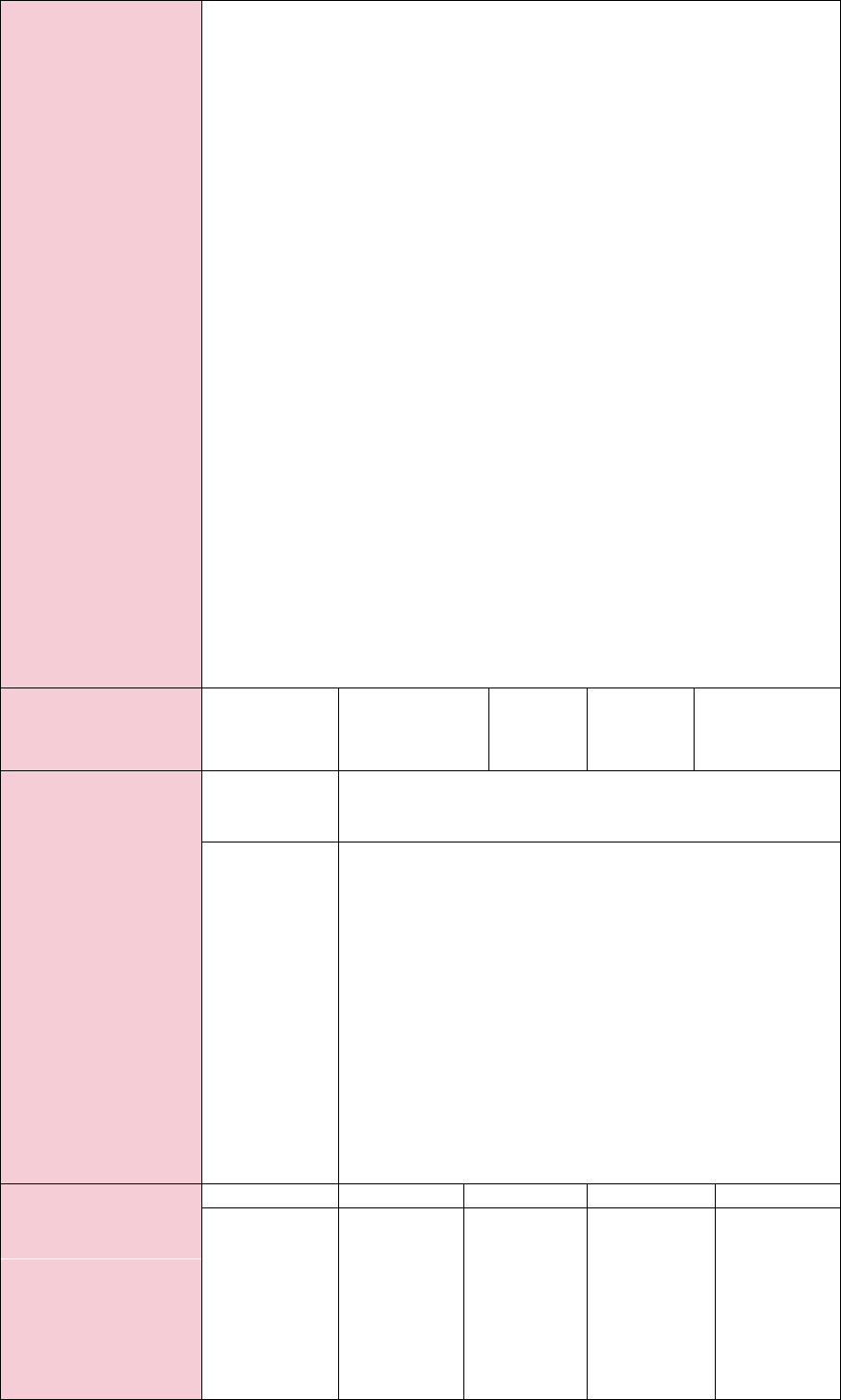

Image 1. Recreation infrastructure

Source: Barcelona Institute for Children and Adolescents

LAYER 1: Play Areas and School Playgrounds

Both of these are ideal places for children to play outdoors, which are not shared with other

uses and are specifically designated and designed for playing and doing physical activity, with

some kind of specially designed equipment that requires certification.

Play areas: Enclosed, sign-posted and certified spaces designated exclusively for play with

expressly designed and certified playful equipment.

School playgrounds: Outdoor spaces at nursery, infant, primary and secondary schools

where children play in school time and at midday, and which can be opened up to the

neighbourhood at other times.

LAYER 2: Playful spaces and School surroundings

Both of these spaces are for the exclusive use of pedestrians with possibilities for play and

playful uses alongside other public activities. Given their characteristics, they may include

urban features with possibilities for play, as well as certified play equipment. They are

basically places for people to meet socially that are vital for intergenerational relations, locals

to mix and community life. Access to them must ensure children’s safety and their autonomy,

as well as facilitate mobility on foot or on wheels. They must also be accessible.

Recreation spaces: Parks, squares, gardens and residential block interiors that offer

possibilities for play alongside other uses and may or may not include a play area. Recreation

spaces offer more risky, more diverse opportunities for play and physical activity that are

suitable for all ages and go beyond what play areas offer, as it is possible to play running,

skating or riding a bike, with a ball, conveying artistic expression or interacting with the

natural surroundings. For the Plan’s operational purposes, we have moved away from the

24

concept of green spaces to call them recreation spaces and identify them as places for play

where the idea is to promote play.

School surroundings: Urban spaces around schools and at nursery, infant, primary and

secondary school entrances with traffic-calmed access and possibilities for an area to relax

and play in.

These places form part of the second layer due to their specific and valuable function as

places for meeting and community life, as the schools’ educational community meet there

throughout the school year, morning, midday and afternoon, time for waiting and

impromptu play. People meet and children play to a greater or lesser extent depending on

the urban features of these areas, the environmental conditions and road safety.

LAYER 3: Playable city

This third layer includes other urban and natural spaces, as well as pedestrian routes in the

city where children, adolescents, adults and elderly people play or do physical activity more

or less spontaneously or by chance. This makes it possible to maximise the opportunities for

play by adopting various measures, from widening, optimising and/or conditioning urban

spaces to installing urban furniture and other highly playable features, tactical urban

planning and one-off initiatives that stimulate play. These include:

Streets for the exclusive use of pedestrians, permanently or temporarily

Traffic-calmed streets and wide pavements

Playable urban furniture (benches, shelters, etc.)

Urban sports parks (skate parks)

Open multi-sports courts

Sports equipment (basketball baskets, table-tennis tables, pétanque courts, etc.)

Beaches, woodland parks and river beds

4.3 Quality criteria for movingtowards a playable

city

Based on the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child’s Comments on the right to play (GC

N. 17, 2013) and an analysis of international reference documents on designs for maximising

the playability of the urban environment (see bibliography), 7 quality play criteria have been

drawn up that should be taken into account when designing spaces to play in the city,

especially play areas and recreation spaces. The preliminary version, included in the

Barcelona Plays Things Right Strategy, has been evaluated in various working forums for

drawing up the Plan, especially in the Urban Model departments, as well as with the

Municipal Institute of Parks and Gardens and the Barcelona Children and Adolescents

Institute. This Plan provides for drawing up an operational handbook for designing projects

that will go into more detail on the requirements and technical guidelines based on these

seven criteria.

25

Quali

ty

criter

ia

for

movi

ng

towa

rds a

play

-

frie

ndl

y

city

Criterion 1: Multiple options for creative, challenging play for

healthy child development

Play areas should offer lots of options that foster all-round healthy child development,

maximising diverse physical activity and stimulating the desire to play.

They should offer children challenges so they explore, decide and handle them as the

protagonists of the action, accepting responsibilities and assuming risks independently,

and testing their skills.

They should allow creative and versatile play with structures that stimulate children to

play in different ways, enabling them to handle objects so they can construct, destroy

and move them, pile them up and so on, thus fostering their imagination and creativity.

The play options should combine movement, symbolic, motor, experimental and other

types of play and, at the same time, ensure maximum diversity in the main playful

activities (see Table 1), in particular sliding, swinging and climbing, as these are the three

that imply more active, more intense play.

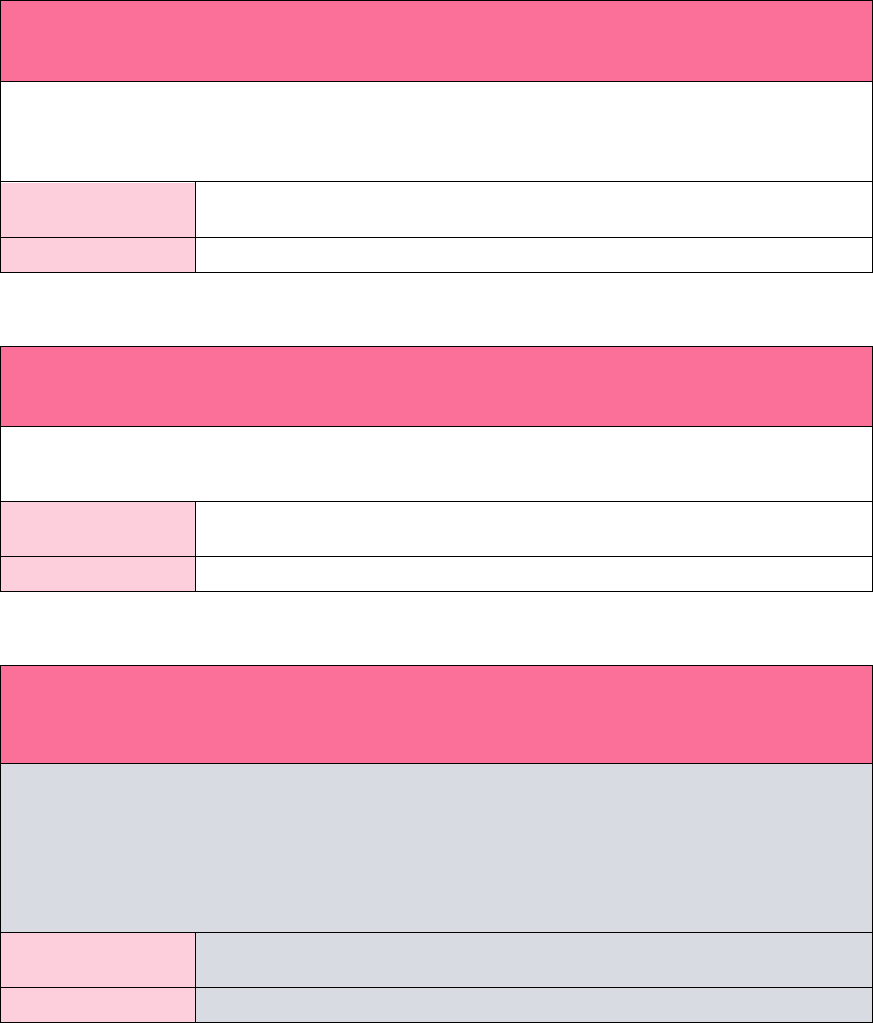

1. Multiple proposals for challenging and creative games that

aid a child and adolescent’s healthy development

7

CRITERIA

FOR A

PLAYABLE

AND

PLAYED-

IN

CITY

2. Diverse, stimulating, connected and

accessible

physical space

3. Inclusive play areas for all ages, genders, backgrounds

and abilities.

4. Contact with nature, greenery and play with sand

and water.

5. Shared, intergenerational and collaborative play.

6. Place for meeting up and where the

community can come together.

7. Playful ecosystems and safe, playable

environments friendly environments.

26

Table 1. Main playful activities and equipment that stimulates them

Activities Equipment/facilities that can stimulate

playful activity

1. Sliding

Slides of different heights and widths, long and short, covered in the

form of a tube or open, with different gradients and shapes, etc.

Sloping slide boards with different heights and gradients.

2. Swinging

Single and multiple swings suitable for different ages, from babies to

adults, different heights, for swinging in pairs, deckchair-type (suitable

for children with functional disability), basket swings for playing

together, for adolescents and children with motor disabilities, etc.

3. Climbing

Climbing walls, ladders, raised platforms, steps, net pyramids,

sculptures that children can climb on, mikado play towers, natural logs

and so on, with different heights and levels of difficulty, for all ages.

4. Maintaining

balance

Balancing bars, log circuits, hanging bridges, etc., at different heights,

with various levels of difficulty.

5. Jumping

Trampolines, flexible net, rubbers structures, platforms with springs,

etc.

6. Feeling dizzy

Merry-go-rounds for one or more children, ziplines, hanging bridges at

different heights, firemen’s poles, etc.

7. Rocking

Individual or multi-child see-saws, spring or up-and-down type, on the

ground or hanging, with ropes and different intensities.

8. Running and

riding

Spaces large and open enough for running, cycling, skating,

skateboarding or scooting around as well as playing ball games, rope

games or other motor-skill games.

9. Hiding

Little houses, bushes forming an enclosure, structures for getting

underneath, tubes, natural elements in the form of a cave, tunnels,

etc.

10. Experimenting

Sand tables or surfaces, natural elements (stones, sticks, leaves),

water channels, games with pulleys with buckets and receptacles,

sound structures, circuit-type spaces for exploring, etc.

11. Role play

Little houses, kitchens, structures in the form of vehicles, vessels,

trains, cars and animals, other structures that suggest settings, for

example, castles, cabins, etc.

12. Self-

expression

Boards, chalk, poles and sand, stages and stepping, smooth concrete

paving and mirror-effect wall for dancing, electricity supply and WiFi for

music, “free” walls for urban art, etc.

13. Meeting up

and relaxing

Places for meeting up with benches arranged for group

conversations, big and small picnic tables, comfortable grass

surfaces for sitting on the ground, shaded areas, etc.

Source: Barcelona Institute for Children and Adolescents

27

Criterion 2: Diverse, stimulating, connected and accessible

physical space

Play areas should adopt an overall perspective on the design for play, meaning that the

whole area should offer stimulating possibilities for playing with a design that fits in with

the environment, offering a variety of uses.

They should be physically attractive, well looked-after, welcoming spaces for people to

stay, meet up and play with surfaces (textures, materials, colours, etc.) and a relief

(tunnels, embankments) that open up various possibilities and enrich play, apart from

the structures.

They should not necessarily, nor always, be confined or demarcated with an enclosure.

This should be dependant on each case, the proximity of any dangers, the suitability of

installing one or not, the perimeter and type of enclosure, reducing them as much as

possible to facilitate connectivity with the rest of the environment.

Criterion 3: Inclusive play areas for all ages, genders, backgrounds and

abilities.

Play areas should be attractive places for people of various ages to play in and, in

particular, include the play and playful needs of adolescents (with team-game and

lifting equipment, spaces for performance play, etc.) as well as play options for

adults.

They should encourage children to play together and, therefore, be diverse places

that do not focus too much on more physical activities at the expense of others.

They should accommodate the city’s cultural wealth and diversity, with a design that

avoids excessive specialisation and encourages children to relate so that,

spontaneously, they become inclusive spaces for children from different

backgrounds.

There should be one or more inclusive-certified pieces of equipment that enables a

child with a functional disability (motor, sensory, intellectual) functional diversity to

enjoy themself with other children.

Criterion 4: Contact with nature, greenery and play with sand and water.

Play areas should include greenery and vegetation that children can interact with,

pass under, hide in, climb, touch and feel the leaves, as well as play with the leaves

and small branches that fall off.

They should include natural elements such as sand, grass, bark, stones for the

surfaces and to expand their playability, as well as water for cooling down and

playing with.

It should be possible to climb, balance and relax on natural features such as rocks or

logs, as well as have play equipment made from natural materials.

Criterion 5: Shared, intergenerational and collaborative play.

28

Play area structures should foster shared play, encouraging the simultaneous play of

two or more children, and group play involving boys and girls (multi-games, see-saws

for two or four, wide slides for more than one person to slide down, swings for older

persons, etc.).

Some structures should incorporate the need for collaboration (pulleys, see-saws,

etc.) as the starting point for shared play which maximises the psychosocial benefits

of play.

There should also be options for shared play between children and the adults looking

after them, equipment that could be used by adults and elderly people, thus

encouraging attitudes and playful activities involving everyone and throughout the

life cycle.

Criterion 6: Place for meeting up and where the community can come together

Play areas and their immediate surroundings should not be conceived as children’s

playgrounds but as a community meeting place, therefore taking into account the

needs of adults looking after the children.

They should be comfortable, welcoming places with benches, picnic tables, toilets,

shade, good lighting, fountains, good maintenance and cleaning.

Places where people come together, meaningful places for the community that

should promote formulas for joint responsibility when it comes to looking after them.

Criterion 7: Playful ecosystems and safe, playable environments

Play areas should be designed fulfilling as many criteria as possible in each one, while

bearing in mind they are part of a broader recreation ecosystem which they

complement.

The community recreation ecosystem comprising various play areas, recreation

spaces, school surroundings and playgrounds with community uses in a given area

should be connected by pedestrian routes, safe paths and traffic-calmed streets. Play

area, recreation spaces and school entrances and surroundings should facilitate the

free movement of children from a certain age and independent play.

29

5. Diagnosis of the opportunities for

play in Barcelona’s public spaces

The knowledge generated in this initial diagnosis of the opportunities for play in Barcelona’s

public spaces enables us to guide the actions of the Plan on the basis of data, create

indicators, establish base lines in 2018 and measurable targets for 2030 for those challenges

for which data is available. This diagnosis is also useful as a starting point for detecting gaps

in our knowledge and for future research to understand the scope, update the challenges,

see the progress and the impacts on play in public spaces. Creating databases and a system

of indicators to carry out this initial diagnosis has required a big effort but means in the

future Barcelona City Council will be in the best possible position to account for its work and

monitor the opportunities for play in public spaces, to help make public decisions based on

evidence in moving towards a playable city that people play in.

This section starts from the preliminary analysis carried out by the IIAG for the Barcelona

Plays Things Right Strategy (February 2018), summarises Barcelona Regional’s specific

diagnostic report on recreation infrastructure and systematises and analyses the scant data

available on the playful uses of public space in Barcelona prepared by the IIAB.

The diagnosis is approached from two angles. First, recreation infrastructure is analysed in

terms of availability, density, proximity and quality. Second, the playful uses of public space

are analysed in terms of playful and physical activity.

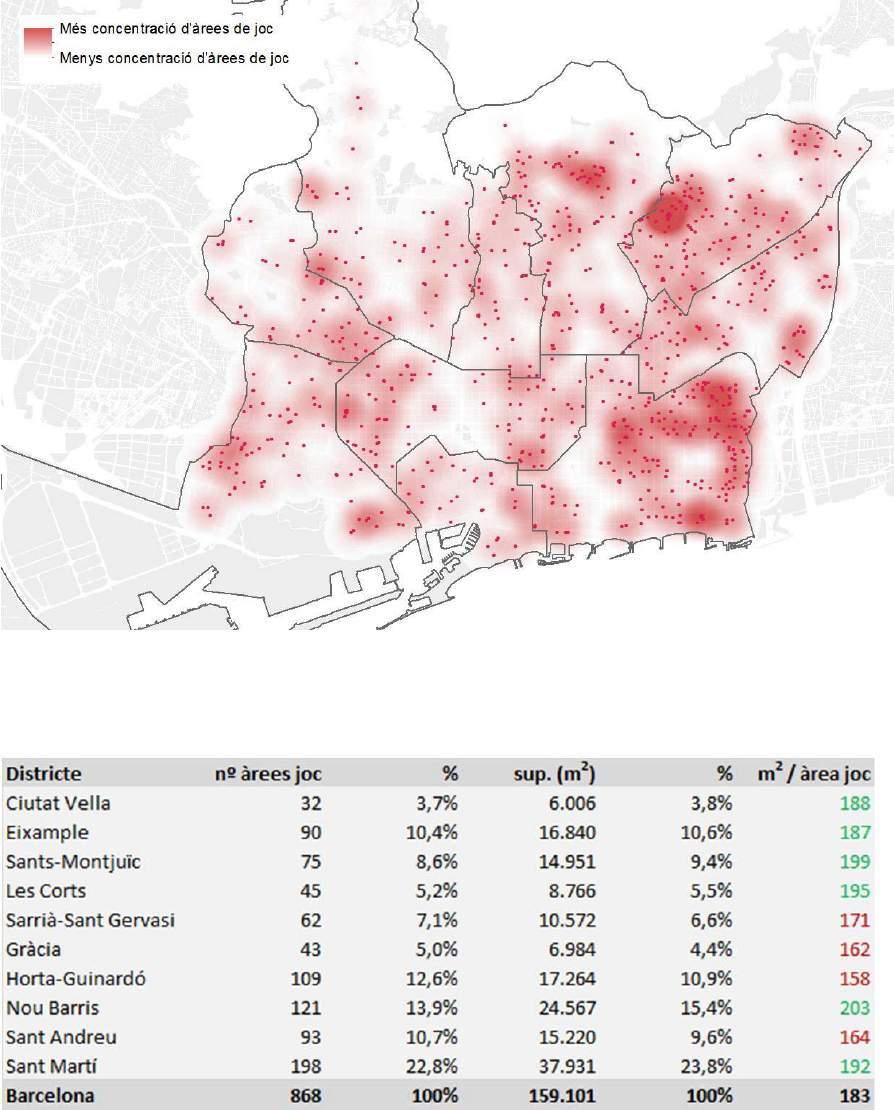

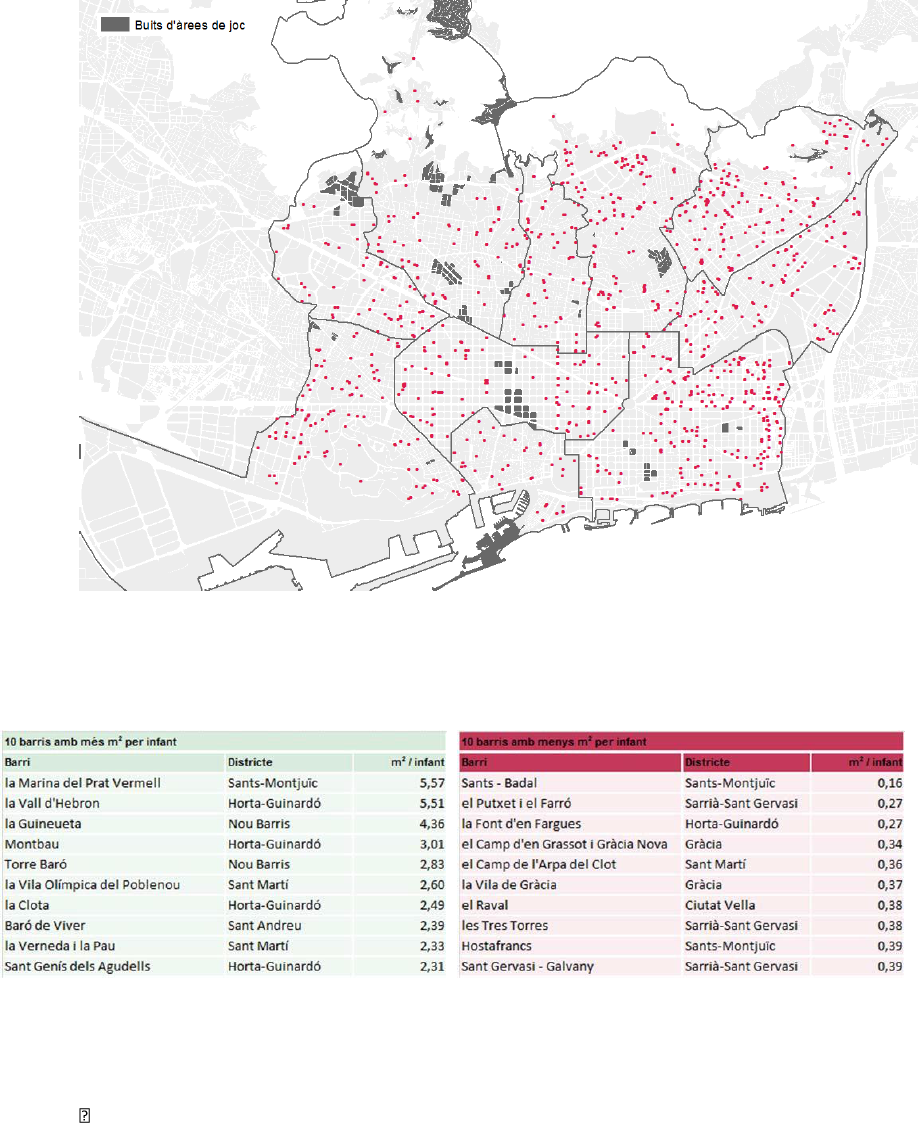

In 2018, Barcelona City Council, or more specifically the Green Spaces, Ecological Biodiversity

and Urban Services Directorate, compiled detailed information on the city’s play areas with

regard to their location, surface area, age, type of paving and enclosure, as well as the type of

playful activity offered in each one based on an analysis of their features. That has enabled a

more in-depth look at the qualitative side of the diagnosis. In addition, data provided by the

Barcelona Institute of Sport has enabled us to supplement the spaces for doing sport with

opportunities for play in any part of the city. A bibliographical review of reports and

documents produced by the Municipal Institute for Persons with Disabilities, the Barcelona

Public Health Agency and the Barcelona Institute for Children and Adolescents has made it

possible to include diagnostic conclusions on other aspects of recreation infrastructure, such

as school playgrounds and the areas around schools or the services offered by parks and

squares, as well as physical activity in and the play uses of public spaces. With regard to the

final aspect on uses, it should be noted that despite the efforts to compile data, there is really

very little information so it will be necessary to continue working on this to improve our

knowledge of the outdoor playful activity of all ages in the city.

Context

Barcelona is one of the most compact and densest cities in Europe (with 159 inhabitants per

hectare) and every day a very significant number of workers and students come here from

the metropolitan area, as well as a large number of tourists. Consequently, public space in

the city comes under lots of pressure from its different uses and has to accommodate the

many needs of urban dynamics, social relations and citizen activities, which include play and

physical activity.

30

One of the dangers that Barcelona faces, therefore, is becoming too compact. The

relationship between the built up area and public space is dominated by the former, which

translates into increased urban pressure with various consequences for the city. Barcelona is

practically consolidated. The margin for growth is limited and very specific as there is no

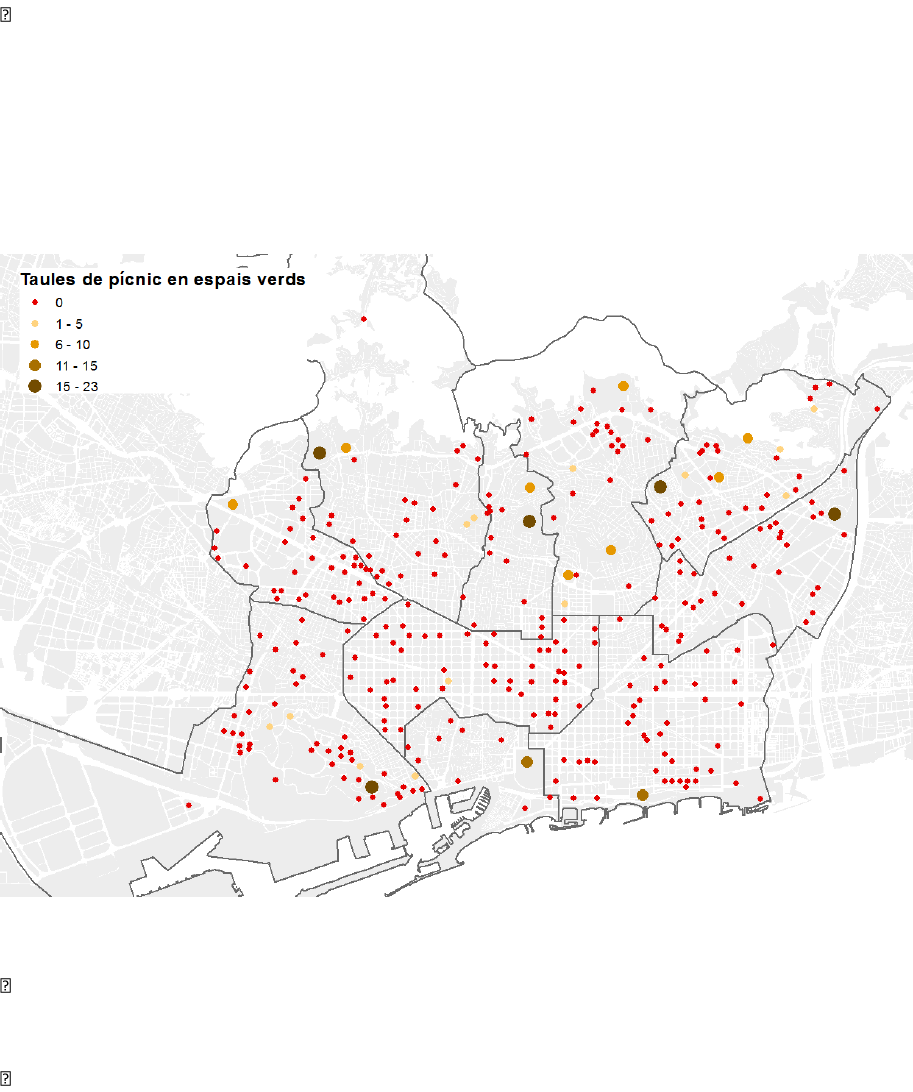

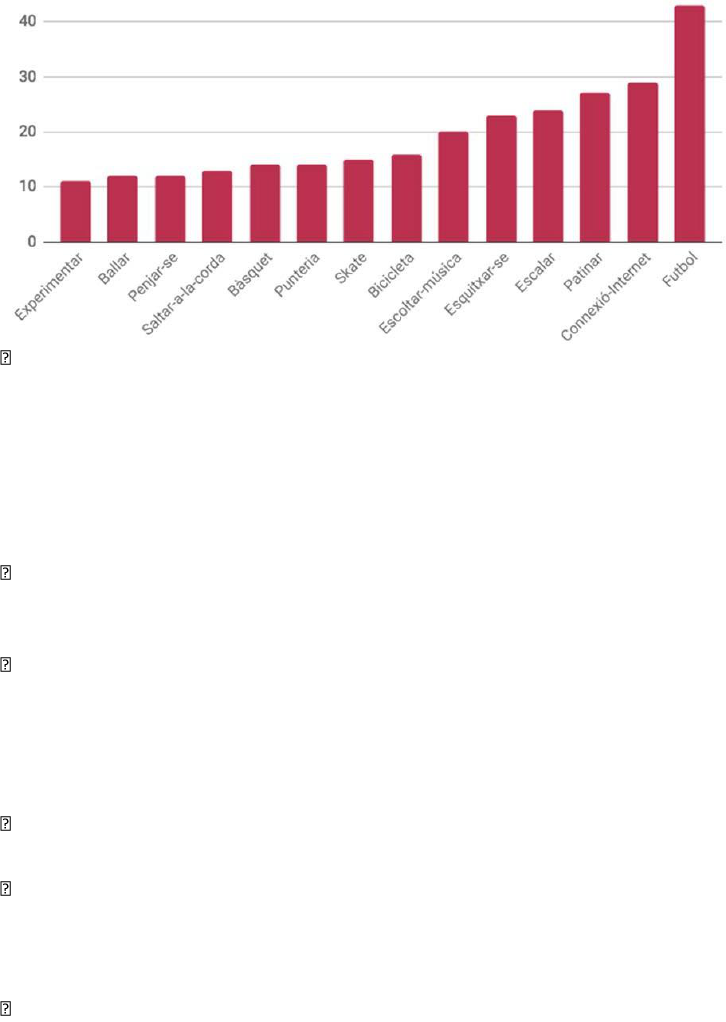

developable land, in other words, hardly any areas remain for development. Public space