Trafficking Victim Identification

A Practitioner Guide

This Practitioner Guide was prepared by NEXUS Institute in the framework of the project: Improving

the Identification, Protection and Reintegration of Trafficking Victims in Asia: Practitioner Guide Series,

implemented jointly by NEXUS Institute and the Regional Support Office of the Bali Process. The

Practitioner Guide Series supports the work of practitioners in ASEAN and Bali Process Member States

by identifying, distilling and presenting existing evidence in a succinct and accessible format and

offering guidance on how to address issues and challenges to improve the identification, protection

and reintegration of trafficking victims in the region.

Authors: Rebecca Surtees and Laura S. Johnson

Technical review: Stephen Warnath, Marika McAdam and Jake Sharman

Design and layout: Laura S. Johnson

Copy editing: Millie Soo

Publishers: NEXUS Institute

1440 G Street NW

Washington, D.C., United States 20005

Regional Support Office of the Bali Process (RSO)

27

th

floor, Rajanakarn Building

3 South Sathorn Road, Sathorn 10120

Bangkok, Thailand

Citation: Surtees, Rebecca and Laura S. Johnson (2021) Trafficking Victim Identification: A

Practitioner Guide. Bangkok: Regional Support Office of the Bali Process (RSO) and

Washington, D.C.: NEXUS Institute.

© 2021 NEXUS Institute & Regional Support Office of the Bali Process (RSO)

The NEXUS Institute

®

is an independent international human rights research and policy center. NEXUS

is dedicated to ending contemporary forms of slavery and human trafficking, as well as other abuses

and offenses that intersect human rights and international criminal law and policy. NEXUS is a leader in

research, analysis, evaluation and technical assistance and in developing innovative approaches to

combating human trafficking and related issues.

www.NEXUSInstitute.net @NEXUSInstitute

The Regional Support Office of the Bali Process (RSO) was established in 2012 to support ongoing

practical cooperation among Bali Process members. The RSO brings together policy knowledge,

technical expertise and operational experience for Bali Process members and other key stakeholders to

develop practical initiatives in alignment with Bali Process priorities. The Bali Process on People

Smuggling, Trafficking in Persons and Related Transnational Crime (Bali Process) established in 2002

and Co-Chaired by Australia and Indonesia, is a voluntary and non-binding process with 45 Member

States and 4 international organizations, including the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

(UNHCR), the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), the International Organization

for Migration (IOM) and the International Labour Organization (ILO), as well as several observer

countries and international agencies.

www.BaliProcess.net/Regional-Support-Office/ @BaliProcessRSO

Nearly every sought-after improvement for meaningful advances in protection, prosecution and

prevention in human trafficking responses depends on first understanding and applying new insights

and skills to effectively identify victims reflecting the full range of manifestations of human trafficking

cases. This Practitioner Guide contains an important collection of these practical insights that reveals a

path for increasing proactive discovery of human trafficking cases in communities and countries.

Stephen Warnath

Founder, President and CEO

NEXUS Institute

Washington, D.C.

Unless victims are identified they cannot be assisted and protected, nor can their traffickers be brought

to justice. Regardless of the country or context in which trafficked victims are exploited, their effective

identification requires that a range of skills from a range of counter-trafficking stakeholders be brought

to bear. The RSO is proud to make this Practitioner Guide available to practitioners across Bali Process

Member States, to support them in their efforts to learn from each other’s experiences in improving

victim identification. This guide supports efforts called for in the 2018 Bali Process Ministerial

Declaration to strengthen Member State collaboration with civil society to identify victims of trafficking

and prevent serious forms of exploitation.

Jake Sharman

Dicky Komar

RSO Co-Manager

(Australia)

Regional Support Office of the Bali Process (RSO)

Bangkok, Thailand

RSO Co-Manager

(Indonesia)

Regional Support Office of the Bali Process (RSO)

Bangkok, Thailand

Table of contents

About the Practitioner Guide ................................................................................................. 1

What it is ................................................................................................................ 1

Who it is for ............................................................................................................. 1

How to use it ........................................................................................................... 1

What is victim identification? ................................................................................................. 2

Legal obligations in trafficking victim identification ............................................................... 5

Issues and challenges in the identification of trafficking victims ............................................ 6

Trafficking victim experiences of identification .................................................................. 7

Fear of traffickers and authorities ............................................................................................ 7

Physical and psychological impacts of trafficking ............................................................... 9

Identification does not offer what victims want and need .............................................. 10

Cultural norms and language barriers ................................................................................... 12

Structural and institutional challenges of victim identification ......................................... 15

Hidden nature of trafficking .................................................................................................... 15

Biases, assumptions and misconceptions of practitioners ................................................ 16

Insufficient knowledge, skills and sensitivity of practitioners ......................................... 17

Insufficient screening tools and procedures for victim identification ........................... 21

Geographical and practical barriers to identification ........................................................ 23

Other Bali Process and NEXUS Institute resources on trafficking victim identification .... 26

1

About the Practitioner Guide: Trafficking Victim Identification

What it is

This Practitioner Guide distills and presents existing research and evidence on the identification (and

non-identification) of trafficking victims, including challenges and barriers that may impede victim

identification and practices that may enhance it. It is part of the NEXUS/RSO Practitioner Guide series:

Improving the Identification, Protection and Reintegration of Trafficking Victims in Asia, which shares

knowledge and guidance on different aspects of trafficking victim protection, including:

• Trafficking victim identification

• Trafficking victim protection and support

• Recovery and reintegration of trafficking victims

• Special and additional measures for child trafficking victims

This series is drafted by NEXUS Institute and published jointly by NEXUS Institute and the Regional

Support Office of the Bali Process (RSO). Practitioners from Bali Process Member Governments of

Australia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam contributed to the development of

these guides in a virtual roundtable discussion convened by the RSO in April 2021. The project is

generously funded by the Australian Department of Home Affairs, through the RSO. The series is

available on the NEXUS Institute website and the RSO website.

Who it is for

This guide is for practitioners in Bali Process Member States, as well as further afield, seeking to better

understand and conduct the identification of adult and child trafficking victims. This includes a range

of practitioners engaged in victim identification and referral (for example, police, prosecutors,

healthcare practitioners, immigration and border authorities, labor inspectors, social workers and child

protection staff as well as staff of multi-disciplinary teams (MDTs), task forces and victim identification

agencies). This Practitioner Guide will also be useful for policymakers tasked with improving victim

identification practice and procedures.

How to use it

This Practitioner Guide offers a comprehensive overview of victims’ experiences of identification as

well as key issues and challenges in conducting trafficking victim identification. Practitioners can use

this guide to improve their knowledge of victim identification as well as use the concrete, actionable

guidance to address issues and barriers in their day-to-day work on victim identification.

Key Guidance Notes Tips

Victim experiences Structural and institutional challenges

2

What is victim identification?

Victim identification is the process, generally a series of interactions, through which an individual is

identified as a trafficking victim by relevant practitioners. Identification may be reactive (when an

individual self-identifies as a trafficking victim and seeks

assistance) or proactive (when practitioners identify

trafficking victims in the course of their work).

An individual is preliminarily assessed or identified as a

presumed trafficking victim, based on signals and

indicators that arise through observing, interacting and

speaking with the individual. Those who consent are then

referred for further assessment, as well as assistance and

protection. Formal identification is the official

determination that a person is a victim of trafficking,

leading to voluntary referral for assistance, reintegration

and/or legal remedy. The threshold for formal victim

identification varies substantially from country to country,

as do the rights and protections afforded to trafficking

victims.

Interactions at all stages of the identification

process should be trauma-informed, victim-

sensitive, child-friendly, gender-sensitive and

culturally appropriate.

Some individuals will not be formally

identified as victims of trafficking after they

have been preliminarily identified as

presumed victims. Victims should have the

right to appeal a negative determination,

although this does not exist in all countries.

Individuals determined not to be trafficking

victims may nonetheless have protection and

assistance needs and should therefore be

referred to relevant authorities for protection

and support.

Which institutions are responsible for identification is

determined by the legal and administrative framework in place

and may include various practitioners (police, prosecutors,

social workers, healthcare practitioners, child protection staff,

immigration and border officers and labor inspectors as well as

staff of multi-disciplinary teams (MDTs), task forces and victim

identification agencies).

Large numbers of trafficking victims are unidentified in the destination country and also when they

return home. Many victims come into contact with authorities at various stages of trafficking but

experience missed identification (being unidentified by practitioners) or mis-identification (being mis-

categorized as an irregular or smuggled migrant or involved in illegal activities).

As a consequence,

they may not know that they are entitled to assistance as a trafficking victim.

trauma-informed: recognize the impact of

trauma and promote environments of

healing and recovery

victim-sensitive: prioritize the victim's

wishes, safety and well-being in all matters

and procedures

child-friendly: design and implement

measures with the needs, interests, safety

and best interests of the child in mind

gender-sensitive: treat all victims with

equal respect regardless of their gender

identity, refraining from stereotypes or

assumptions on the basis of gender

culturally appropriate: take into account

and respect the victim’s cultural and

religious beliefs, values, norms, practices

and language

preliminary

identification

formal

identification

referral for

assistance

3

Some trafficking victims may avoid identification or decline to be identified for different reasons.

Those who initially decline identification and assistance may change their minds at a later stage and

should have the option to be identified and assisted. Whether this is possible differs by country.

Identification may differ in the case of trafficked children, for whom additional protection obligations

apply. Those who appear to be children should be presumed to be children until determined

otherwise. Identification processes for children require contacting and involving relevant child

protection authorities (usually state social workers) and applying a set of protective measures and

specific approaches. If a child is not assessed to be a trafficking victim, they should nonetheless be

referred to child protection agencies for protection and to address their needs and vulnerabilities.

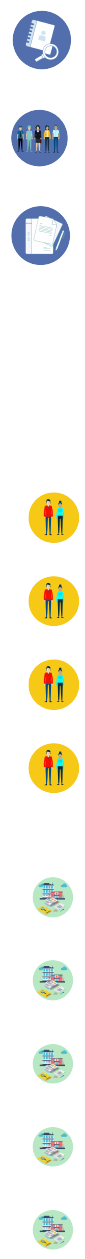

Different pathways of identification experienced by trafficking victims

4

Different pathways of identification, protection and reintegration experienced by trafficking victims

5

Legal obligations in trafficking

victim identification

Trafficking victim identification is assured in

some international and regional instruments,

which may be relevant for domestic laws and

policies.

International law and guidance

UN Trafficking Protocol (2000) offers the

first agreed definition of trafficking in persons

and calls on states parties to implement

measures to criminalize trafficking (Article 5)

and assist and protect trafficking victims

(Article 6).

UNOHCHR Recommended Principles and

Guidelines on Human Rights and Human

Trafficking (2002) emphasize the importance

of written identification tools and call on states

to consider developing such tools to permit the

rapid and accurate identification of trafficked

persons and to train authorities in the

application of these tools (Guideline 2), giving

special consideration to the identification of

trafficked children (Guideline 8).

UNICEF Guidelines on the Protection of

Child Victims of Trafficking (2006) call on

states to develop and adopt effective

procedures for the rapid identification of

trafficked children (Guideline 3.1).

UN Convention on the Rights of the Child

(1989) calls for protection of children from

economic, sexual and all other forms of

exploitation (Articles 32, 34, 36) including

measures for identification, reporting, referral,

investigation, treatment and follow-up of

instances of child maltreatment (Article 19).

Regional law and guidance

ASEAN Convention Against

Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and

Children (ACTIP) (2015) requires states parties

to establish national guidelines or procedures

for the proper identification of victims of

trafficking and to ensure that countries

mutually recognize identification decisions

(Article 14).

ASEAN Plan of Action Against

Trafficking in Persons, Especially Women and

Children (2012) calls for member states to

utilize existing regional guidelines and develop

or strengthen national guidelines for the

identification of trafficking victims, including

applying appropriate and non-discriminatory

measures that help to identify trafficking

victims among groups who are more

susceptible to trafficking.

ACWC Gender-Sensitive Guidelines

(2016) state that presumed victims should be

treated as victims unless another determination

is made; that a presumed child should be

considered a child until determined otherwise;

and stress the importance of victim-centered

and gender sensitive interventions.

ACWC Regional Guidelines and

Procedures to Address the Needs of Victims of

TIP, especially women and children (2018) call

on ASEAN member states to adopt clear

definitions of human trafficking; conduct rapid

and accurate victim identification; mutually

recognize identification decisions; refer

identified victims; and offer special measures in

the identification and referral of children.

COMMIT-ASEAN Common

Indicators of Trafficking and Associated Forms

of Exploitation and COMMIT Victim

Identification and Referral Mechanisms:

Common Guidelines for the Greater Mekong

Sub-Region (2016) offer guidance on

identification including agreed indicators.

Council of Europe (CoE) Convention on

Action Against Trafficking in Human Beings

(2005) provides detailed measures on victim

identification, including special measures for

the identification of child trafficking victims.

European Union Directive 2011/36/EU

(2011) calls specifically for the development of

general common indicators for the

identification of victims of trafficking in the

European Union.

6

Issues and challenges in the identification of trafficking victims

Issues and challenges faced in trafficking victim identification center around two main themes:

• Trafficking victim experiences of identification

• Structural and institutional challenges of identification

• Fear of traffickers and authorities

• Physical and psychological impacts of

trafficking

• Identification does not offer what

victims want and need

• Cultural norms and language barriers

• Hidden nature of trafficking

• Biases, assumptions and misconceptions of

practitioners

• Insufficient knowledge, skills and sensitivity

of practitioners

• Access to information about identification

and referral

• Insufficient screening tools and procedures

for victim identification

• Geographical and practical barriers to

identification

These issues and challenges are not mutually exclusive and practitioners must often tackle multiple

challenges in their efforts to identify trafficking victims. Issues are also context-specific and change

over time (for example, over the course of a trafficking victims’ life, as traffickers change their strategies

and tactics and as capacity of institutions and practitioners engaged in victim identification improves).

7

Trafficking victim experiences of identification

Fear of traffickers and authorities

Victims are generally fearful at identification, both of traffickers and authorities. Fear leads many

victims to avoid identification or refuse it once identified. Children may be especially fearful of and

controlled by traffickers, informing also their perceptions of authorities and the identification process.

Intimidation, threats, control and violence by

traffickers. Traffickers use different strategies

to stop victims from seeking help including

controlling victims, threatening and abusing

them, withholding payments and documents

and using debt. Traffickers commonly control

or limit victims’ contact with others at all

stages of trafficking. Victims may be required

to stay in pre-departure migrant worker

training centers with restricted freedom of

movement. They are often strictly monitored

during their journey and upon arrival at their

destination. While trafficked, many

employers/exploiters isolate and control

trafficking victims, keeping them largely out

of sight and limiting their contact with others.

Traffickers often accompany victims when in

public and are strategic in whom they permit

them to interact with.

Many victims refuse or avoid identification

out of fear

of their traffickers. Trafficking

victims may be intimidated, threatened,

coerced and abused by individuals or

agencies while trafficked as well as once

home. Some trafficking victims fear

retaliation against their co-workers if they

escape or report to the police.

Traffickers also foster fear of authorities,

warning victims that they will be arrested,

imprisoned and deported if they cooperate

with the authorities, which, in some cases,

may be true. Once out of trafficking, some

victims fear that their decision to be

identified or assisted will be understood by

traffickers as collaboration with authorities.

Traffickers withhold payments and

documents to deter victims from seeking or

accepting identification. Many victims go

unpaid for months and years but feel unable

to escape because of promises that they will

be paid in future. Some victims receive small

8

amounts of money, which they may assess as

better than not earning anything. Traffickers

often confiscate victims’ identity documents

and professional certifications to prevent

escape. They also threaten workers with

blacklisting, to bar them from future

employment options.

Traffickers also create and manipulate debt to

prevent victims from seeking or accepting

help. Many victims go into debt to a

recruitment agency or trafficker and this debt is

then used to prevent victims from withdrawing

from migration before departure or to prevent

them from escaping while exploited. Often

times debt increases as traffickers force victims

to pay inflated food and living costs and

“fines” for alleged violations.

Arrest, detention, deportation, criminalization

by authorities. Many trafficking victims have

had negative experiences of authorities before

trafficking as well as while trafficked, including

not being believed to be a victim, being

criminalized and even being brutalized. Some

have had especially negative experiences and

may be particularly fearful of authorities. As a

result, they often do not trust the officials

screening them as trafficking victims or believe

that they will be protected if identified. Many

also doubt assistance offers made to them.

Many trafficking victims avoid detection by

authorities, fearing arrest, detention and/or

deportation.

Being arrested and imprisoned is frightening, stressful and traumatizing. In some cases, trafficking

victims are abused in detention. Being detained or criminalized also impacts how victims’ families

view and receive them as they are often misunderstood as criminals rather than victims.

Victims also

worry about detection once they return home, fearing fines or arrest for having migrated irregularly or

required to participate in legal proceedings.

To conduct proactive identification, practitioners require up-to-date information about

how traffickers control victims and interfere with identification. It is also important in

understanding victims’ decision-making about identification and assistance and in

developing strategies to assuage victims’ fears. Practitioners also require information,

tools and training to be able to effectively and sensitively screen trafficking victims and

avoid mis-identifying victims as irregular migrants or involved in illegal acts. An

understanding of victims’ negative experiences of authorities can aid practitioners in

their work. Using trauma-informed techniques, including providing reassurances to

victims that they are safe, can help to overcome victims’ fear and distrust.

9

Physical and psychological impacts of trafficking

Exploitation has a severe and negative

impact on trafficking victims’ physical and

psychological well-being. This, in turn,

influences their feelings and decisions at

identification. Trafficked children are

especially harmed by the physical,

psychological and emotional impacts of

trafficking, although this differs according

to their age and stage of development as

well as the nature and length of their

trafficking.

Physical impacts. Many victims are

seriously ill and badly injured as a result of

trafficking (for example, due to hazardous

and unhealthy living and working

conditions, lack of food and medical care,

use of alcohol and/or narcotics, physical

and sexual violence, exposure to sexually

transmitted infections). Being physically

unwell may mean victims avoid

identification for fear of arrest and in the

hopes that they can find treatment or ways

to recover.

Psychological impacts. Victims also suffer

from many psychological and emotional

impacts of trafficking including symptoms of

post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD),

depression, anxiety, low self-esteem, lack of

confidence, eating disorders, self-harm,

suicidal ideations, substance misuse and

anger and combativeness. Many victims

suffer memory problems and may not be

able to remember events that practitioners

need to understand to identify them. They

may be afraid, confused, disoriented and

unable to understand identification and

what it offers them. They may then be

unable to make informed decisions about

accepting identification and assistance.

Many victims suffer complex trauma that

impedes their ability or willingness to

disclose trafficking experiences.

Victims feel uncomfortable, ashamed and embarrassed about having been deceived and victimized by

traffickers. Some feel ashamed of what they have been forced to do while trafficked (for example,

migrate irregularly, use false documents, engage in sexual acts or criminal activities). Many victims are

ashamed because they failed to earn money and have substantial migration debt. Victims’ anxieties

may be exacerbated when others in their community migrate successfully and remit money.

10

Some trafficked persons avoid and refuse

identification (and, by extension, assistance)

because they do not want to be stigmatized and

discriminated against as trafficking victims in

their family or community. Many victims do not

tell anyone about the fact that they were

trafficked.

Some trafficking victims do not want to talk about

their trafficking experience and so refuse to be

engaged in an identification procedure. Some

may seek out identification and assistance once

they recover from the initial shock and begin to

make decisions about their lives, including the

need for assistance. Disclosure often takes place

over time, once the victim is able to understand

and trust practitioners and also stabilizes

psychologically and emotionally.

It is important that practitioners understand the physical and psychological impact of

trafficking on victims, including how it interferes with memory, comprehension and

identification decisions. Understanding victims’ concerns and reactions (for example,

confusion, lack of trust, shame, fear) will aid practitioners in the identification and

referral process. Approaches that are trauma-informed, victim-sensitive, child-friendly,

gender-sensitive and culturally appropriate improve victims’ experiences of

identification and lead to better identification outcomes.

Victims are better able to trust

and feel comfortable with practitioners who are sensitive to their feelings and concerns.

Identification does not offer what victims want and need

Identification as a trafficking victim does not always offer what trafficking victims want and need in

their lives after trafficking. This leads, in some cases, to victims avoiding or refusing identification.

Does not lead to assistance or better options.

When a formal identification determination does

not trigger referral and assistance, it offers victims

no benefit and exposes them to, at best,

unnecessary discomfort and stressful screening

procedures and, at worst, harm to their physical

and mental well-being. When identification does

not lead to assistance, it is not an advantage for

the victim to be identified.

Identification also does not always offer victims a

better situation. Some victims opt to stay in

exploitative situations because they are able to

earn money and being identified as a trafficking

victim interferes with this. Some victims

negotiate their exit from trafficking and

identification impedes these plans. Some

trafficking victims are also asylum seekers and

may avoid identification as a trafficking victim as

their asylum claim may offer a more durable

solution than trafficking victim protection.

11

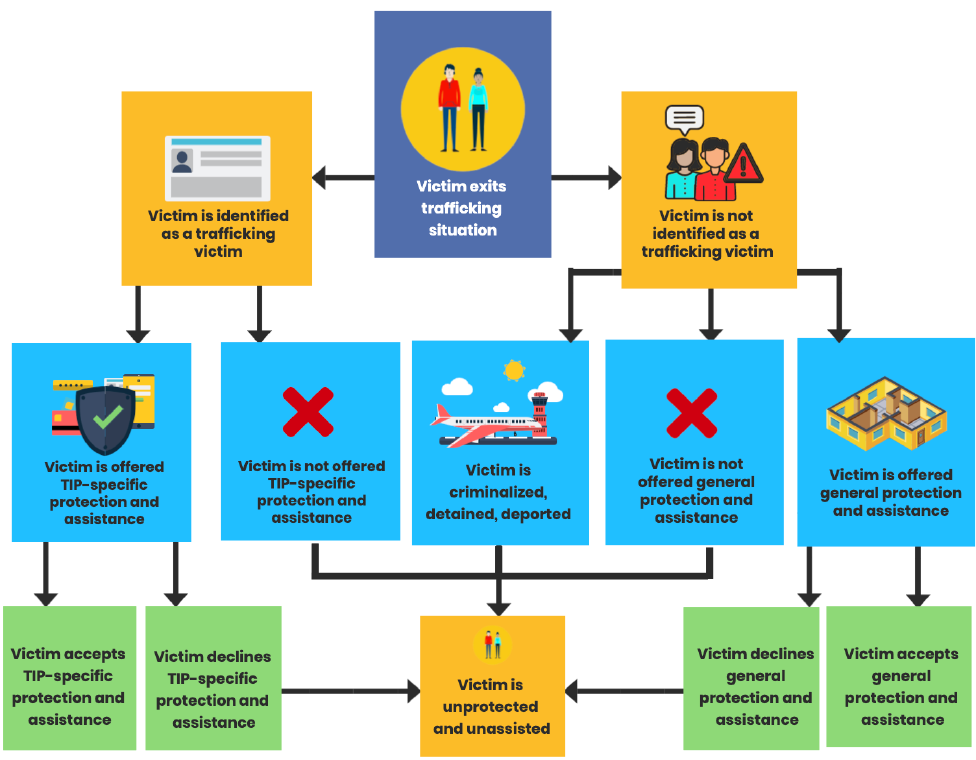

Leads to compulsory assistance and criminal

justice cooperation. Identification may lead to

compulsory assistance, for long periods of time,

living in closed shelters away from family and

without the option to work. Some victims opt

for deportation as irregular migrants rather than

being forcibly assisted in this way. Identification

also often requires being a victim-witness in the

criminal justice process, leading many victims

to decline identification, even when this also

means declining assistance.

Authorities may “encourage” or even strongly

pressure victims to be witnesses, without

explaining what this entails and their right to

decline. In some countries, victims’ rights

(including temporary residence permits) may

be conditional upon cooperation in trafficking

investigations and prosecutions, which victims

often do not wish to be involved in. Often this

assistance is also only temporary and does not

offer a long-term solution.

Assistance is not what victims need or want.

Some trafficking victims are able to cope on

their own and do not need assistance. Others

are able to rely on other types of support in

their recovery and reintegration (for example,

from family, friends, community, religious

organization and other services). In such cases,

there may be no advantages (and many

disadvantages) to being identified as a

trafficking victim. There is also no incentive to

being identified as a trafficking victim when

available assistance is not what one needs (for

example, it does not meet one’s specific and

individual assistance needs) or is offered in a

format that does not align with one’s personal

and family situation (for example, in a shelter,

for a long period of time, away from family,

unable to work).

Do not see themselves as victims. Some

individuals do not see themselves as victims.

For some, this is because they come from

environments where exploitation is normal and

labor protections are lacking. Trafficking is not

always dramatically different from their

previous migration or work experiences.

Others recognize their exploitation but see themselves as “unlucky” rather than as victims. Some do not see

themselves as trafficking victims because they actively migrated and do not identify with vulnerability or

victimhood. Many experience their situation, however difficult, as part of a strategy to improve their

economic situation. For some victims, being called or seen as a victim is jarring and uncomfortable.

12

Even when they may see their situation as

exploitative, identification does not always,

on balance, offer a better alternative.

Perceptions of exploitation depend on what

one compares one’s situation to.

Identification may not be seen as a positive

for those whose material conditions while

trafficked are better than at home or whose

situation will not improve as a result of identification.

Practitioners’ knowledge of victims’ various concerns and considerations about

identification will help them to offer options and opportunities that meet their needs.

Practitioners require an understanding of how trafficked persons perceive their

experiences and needs including why it may lead them to decline identification.

What other concerns might trafficking victims have about being identified?

How can you address these concerns?

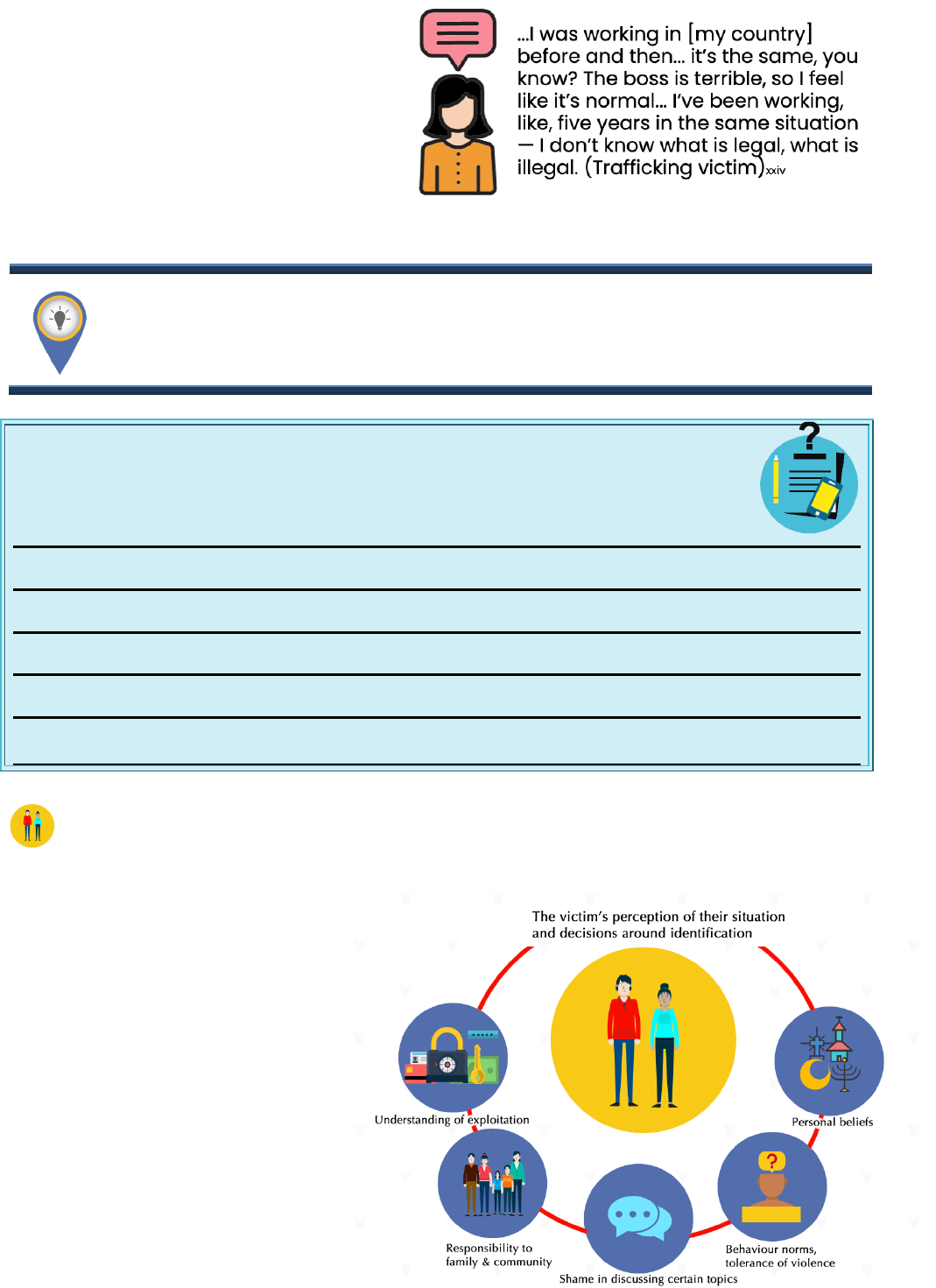

Cultural norms and language barriers

It is important to consider how culture and language inform victims’ perceptions of the identification

process and their willingness to be

identified and assisted. Culture informs

a victim’s perception of their situation

during and after trafficking as well as

their decisions about identification. For

example, cultural and social norms

influence perception of what

constitutes exploitation and abuse and

what constitutes a “normal” work

environment. In some cases, cultural

norms (feelings of responsibility to

family and community) may mean that

exploitation is accepted as it allows

them to fulfil obligations to children or

parents. Culture also informs behavioral

norms (for males and females, adults

and children), feelings about discussing

13

sensitive topics (for example, sexual violence, tolerance of violence), beliefs about fate, all of which

may inhibit disclosure of trafficking experiences to practitioners.

Language barriers can impede identification,

with trafficking victims often unable to

understand what is happening and what

practitioners may be able to do to help them.

For practitioners, language barriers can affect

the ability to apply indicators and assess

whether a victim has been trafficked and what

interventions they need. This is amplified in

the case of children who have different

language literacy, as well as comprehension,

especially in relation to complex topics.

Interpreters are not always available, affordable or sensitive in how they approach victims, which

impacts how victims experience identification. Some practitioners rely on those accompanying the

victim (often traffickers) to interpret, which leads to missed identification.

It is important that practitioners consider how culture and language inform victims’

perceptions and decisions about identification, including how this differs from person to

person and group to group. Engaging professional interpreters and cultural mediators

can help to bridge language and cultural divides. Some technological solutions can

assist with language but attention is still needed to sensitivity in interacting with victims.

What cultural and language barriers have you faced in victim identification?

What can you do to address these in future?

14

Guidance for Practitioners

Learn how traffickers block identification and develop proactive strategies to reach victims.

Assess how traffickers control victims and take steps to mitigate these controls, including discussing

concerns and fears directly with victims. Understand how traffickers’ threats and violence lead victims

to avoid or refuse identification and speak to victims about what can be done to protect them.

Learn about the impact of trafficking and trauma on victims including how it interferes with

memory, comprehension and decision-making. Understand how fear and trauma influence what

victims are able and willing to share with you at identification. Be conscious of trafficking victims’

fears and concerns and the threats and violence they have suffered at the hands of traffickers and, in

some cases, authorities. Be sensitive to victims’ negative past experiences of authorities and reassure

them that they are safe, protected and supported.

Be aware of victims’ feelings of shame and embarrassment at having been trafficked and reassure

them that they are not at fault. Be conscious of victims’ fear of discrimination and stigmatization by

their family and community. Recognize that disclosure often takes time and victims may only disclose

their trafficking experiences to you after some time and once trust has been built.

Understand that the identification of trafficked children involves specific vulnerabilities and

requires additional measures and protections, including child-friendly interviewing and the

presumption of minority age until proven otherwise.

Take steps to avoid revictimizing and retraumatizing victims including controlling who comes

into contact with trafficking victims at identification and avoiding multiple and repeat interviewing.

Implement additional safeguards and protections in the case of trafficked children.

Provide victims with clear and comprehensible information in a language and format they can

understand and that will allow them to make informed decisions. Tailor information about

identification and assistance to be accessible to different trafficking victims, including children.

Recognize that identification and assistance do not always meet victims’ needs and not all

victims will accept identification. Build an understanding of different victims’ assistance needs and

work with service providers to meet these needs so that they have an incentive to be identified.

Be sensitive in your interactions with trafficking victims, including their discomfort in talking

about their exploitation. Learn about approaches that are trauma-informed, victim-sensitive, child-

friendly, gender-sensitive and culturally appropriate and apply these principles in your work to identify

and refer trafficking victims. Provide trafficking victims with the time and space needed to disclose

their trafficking experiences including at a later stage if needed.

Identify qualified and sensitive interpreters and ensure that they are trained in trauma-informed

interviewing with trafficking victims. Identify cultural barriers to identification and address these in

identification tools, practice and procedures. Engage cultural mediators to improve identification.

Ensure that victims’ personal information is treated confidentially and their privacy respected

during identification and referral. Interviews should be conducted in a safe and private location.

Ensure that trafficking victims are not penalized for crimes committed as a direct consequence of

being trafficked. Anticipate the potential for mis-identification; carefully screen persons who may not

immediately or at first glance appear to be trafficking victims.

15

Structural and institutional challenges of victim identification

Hidden nature of trafficking

Many trafficking victims are forced to work

and live in hidden or isolated locations,

sometimes even locked in and with no

freedom of movement. They are often kept

“out of sight” and their contact with others is

generally limited and strictly surveilled. This

is the case for victims of labor trafficking (for

example, factory work, fishing, on

plantations, domestic work) as well as

trafficking for sexual exploitation, forced

marriage, begging, delinquency and criminal activities.

That being said, the extent to which victims are

“invisible” to authorities differs substantially

from victim to victim and is influenced by the

form of trafficking and location where they are

exploited.

16

And while being hidden can block

identification, being visible to authorities is

not a guarantee that victims will be

identified.

Some victims work in plain sight

of authorities and move around freely but

nonetheless go unidentified.

Practitioners require in-depth understanding of how different forms of trafficking take

place and where victims are exploited. It is important that practitioners identify the

different locations where trafficking victims may be exploited and coordinate with the

agencies that have the mandate and access to these locations to conduct or support

identification.

Biases, assumptions and misconceptions of practitioners

Some practitioners may have biases, assumptions and misconceptions about trafficking victims which

impede and undermine victim identification.

Focus on some forms of trafficking and

some types of victims. In many countries,

identification efforts focus on victims of

trafficking for sexual exploitation, with

limited identification of victims trafficked

for other forms of exploitation.

In some cases, stereotypical and gendered

images of trafficking victims influence whom

practitioners identify as victims (for example,

women and girls are more recognizable as

trafficking victims than men and boys). Some

males are even mocked and criminalized by

practitioners who do not take seriously what

has happened to them. In other cases,

practitioners consciously decide to focus on

specific forms of trafficking (for example,

considering trafficking for sexual

exploitation to be “more serious” than other

forms of trafficking and assuming that only

females are trafficked for this form of

exploitation). Males trafficked for sexual

exploitation are especially likely to be

overlooked as a result. Trafficking victims

who identify as LGBTQI+ (lesbian, gay,

bisexual, transgender, queer or questioning,

intersex and self-identified sexual

orientations and gender identities) are also

overlooked. For example, in countries where

same sex relationships are illegal, LGBTQI+

victims may be criminalized for same sex

sexual relations rather than recognized as

having been sexually exploited.

17

Biases and misunderstandings about victims

trafficked for sexual exploitation. Some

practitioners don’t recognize persons as

trafficking victims when they seem to be

willingly engaged in prostitution. Even child

victims of trafficking for sexual exploitation

have been labeled as prostitutes, despite

force, coercion or other means not being

required in the trafficking of a child.

On the

other hand, some practitioners wrongly

assume that all sex workers are trafficking

victims leading to mis-identification and

sometimes forced identification and

assistance.

Misconceptions about victims’ “worthiness”.

Some trafficked persons are not seen as “real

victims” because of their behaviors and

attitudes (including hostility to being

identified); because they do not “look like a

victim”; or because they have migrated or

been trafficked previously. Some practitioners focus on whether the victim was “really” forced,

rendering trafficking victims more or less worthy, depending on the degree to which they entered

exploitation knowingly. Some practitioners focus on acts committed while a person was trafficked,

including irregular migration or prostitution, rather than on the experiences that cumulatively

constitute trafficking in persons. This means only the most “worthy” or “innocent” victims will be

identified and assisted.

Identification efforts should recognize all forms of trafficking and all characteristics of

victims. It is important that practitioners consider and overcome any biases, assumptions

and misconceptions that they may have about trafficking victims which can undermine

victim identification.

Insufficient knowledge, skills and sensitivity of practitioners

Knowledge and skills of practitioners.

Practitioners who are likely to encounter

trafficking victims (including law

enforcement officers, social workers, health

care practitioners, child protection staff,

immigration and border authorities) often

receive little or no training in how to identify

victims or, once trained, do not receive

further training, mentoring or skills

enhancement. Early anti-trafficking

legislation often narrowly defined trafficking

as trafficking for sexual exploitation or

trafficking of women and children,

impacting the victims who practitioners

were trained to identify. Many countries

have since revised their trafficking laws and

policies to include all forms of trafficking

18

but have not always trained practitioners in

these changes.

Many practitioners lack awareness of the

crime including its magnitude in their

communities and the skills to distinguish

between exploitative labor practices and

trafficking in persons. Lack of training and

capacity may be a consequence of the low

priority given to trafficking in persons, or a

disconnect between who is trained and

who does victim identification in practice.

Lack of capacity may be particularly

pronounced when there is a high rotation

of staff, leading to challenges in building

and retaining capacity. It can also be

difficult to apply the legal definition of

trafficking in persons in practice, to a

person’s real-life experiences.

Victim identification involves complicated

and discretionary assessments of each case

and practitioners are often left without

guidance to operationalize central concepts

(for example, coercion, exploitation, abuse

of a position of vulnerability and how the

definition of trafficking differs between adult

and child victims). Some victims actively

seek to avoid identification and some are

coached by traffickers to evade detection,

further complicating identification efforts.

Victim identification may be one of many

tasks practitioners are responsible for and is

often not prioritized or allocated sufficient

resources. Identification, therefore, tends to

be reactive, rather than proactive

(particularly for labor trafficking), contributing

to low levels of identification.

Sensitivity of practitioners. Identification is

not only about practitioners being able to

recognize signals of trafficking but, equally,

about being able to screen and interact with

victims in ways that translate into trust and

disclosure. And yet, many victims are not

treated sensitively and appropriately. Often

victims experience screening more as

interrogations than interviews. Harsh and

unprofessional treatment upsets and frightens

victims and may mean that they don’t

disclose what has happened to them or

accept to be identified. Settings in which

many trafficking victims are identified do not

generally foster trust or comfort and are not

conducive to disclosure (for example, during

19

labor inspections or police operations, at

borders or upon arrival home).

Negligence, maltreatment and abuse of

power. Some practitioners do not identify

victims and may even extort them, making

them pay “fines” to avoid being arrested.

Victims trafficked for prostitution may be

abused and pressured to pay money and

provide sexual services to avoid arrest. In

some cases, authorities cooperate with

traffickers and even return victims to them

when they seek help. Victims have also

reported being physically and sexually

abused and violated while in detention as

irregular migrants. Depending on the

circumstance, such acts may constitute

negligence, collusion, abuse of power,

corruption or, in some cases, even the crime

of trafficking in persons.

Increasing and standardizing knowledge, skills and capacity of practitioners (including

understanding and applying complex legal concepts) is key to enhanced identification.

Practitioners need to be trained in victim identification and kept abreast of any changes

in the legislative and institutional frameworks. Practitioners also benefit from training in

trauma-informed interviewing to improve victims’ identification experiences and their

openness to accepting assistance. Enhanced sensitivity and care, including creating a

safe and comfortable interviewing environment, contributes to building trust and better

protecting victims. Practitioners should be held to account for failure to identify

trafficking victims. Reports of wrong-doing should be carefully investigated.

What forms of trafficking in persons are criminalized in your country’s law?

What parts of the trafficking in person definition in your country are difficult

to understand and apply?

20

Access to information about identification and referral

Many victims do not fully understand what identification means and offers them. They do not

understand their status as a trafficking victim and their right to protection and support. Some

practitioners do not clearly inform victims about what identification means and the protections that it

affords.

Often victims do not receive clear and

comprehensive information about their rights

and options. Practitioners also do not always

sufficiently take into account factors that

impact victims’ comprehension, including

literacy, educational background, analytical

and decision-making skills, language and

culture, and knowledge of assistance.

Often information is provided verbally and not

repeated at a later stage. It is also seldom

provided in a written form that victims can

read and also refer to when they are in a

calmer and more receptive state of mind.

Child trafficking victims also require but do

not always receive both written and verbal

information about identification as a trafficking

victim and options for support. When

information is provided to trafficked children,

it is not always tailored to children’s age and stage of development.

Practitioners play an important role in informing victims about the help they can get as

a result of being identified as a trafficking victim. It is important to provide trafficking

victims with clear and comprehensive information in a language and format they can

understand to allow them to make informed decisions about identification. Information

should be both verbal and written and tailored to victims with different education and

literacy as well as children of different ages and stages of development.

What can you do to help victims better understand identification and what it

offers them? What information can you provide them with?

21

Insufficient screening tools and procedures for victim identification

Robust tools and procedures are needed for

victim identification. Yet these are not

always in place and, where they are,

practitioners may not be aware of them or

trained in their use. Many tools and

procedures are not publicly available or

shared among practitioners engaged in

victim identification. Different agencies

within a country often use different (and

sometimes conflicting) identification tools

and procedures.

Tools that are available have not always

been tested and revised accordingly. They

are also not always updated to keep pace

with traffickers’ methods, forms of

trafficking or characteristics of trafficking

victims. As a result, some identification

tools and resources may be out of date or

reflect biases and assumptions about

trafficking (for example, a focus on female

over male victims, trafficking for sexual

exploitation over other forms, transnational over internal trafficking, trafficking of foreign over country

nationals, or not including less considered victims such as individuals who identify as LGBTQI+).

Tools and procedures vary in their capacity to be practically implemented. Some detail the steps of

preliminary and formal identification and referral while others lack even basic guidance to identify and

refer victims. Most assume a positive identification outcome (that the person is a trafficking victim) and

lack guidance on how to proceed when a person is not a trafficking victim but may still have

protection needs.

Identification tools and procedures are not always child-specific or sensitive to children’s unique needs

and sensitivities. Even those that include generalized statements about ensuring the best interests of the

child often do not specifically consider the unique needs and risks associated with trafficked children

or provide clear guidance on their identification and referral (for example, specific indicators or

questions with which to identify child trafficking victims). This places great responsibility on

practitioners to develop and ask questions in a child-friendly manner, which assumes a high level of

capacity and sensitivity.

Improving screening procedures means engaging

all relevant practitioners in identification, looking

beyond traditional frontline responders (for

example, police and social workers) to include

less considered practitioners in a position to

identify victims (for example, healthcare

providers (as victims require medical care),

firefighters (as fire stations are designated a safe

place in some communities),

psychiatrists (as

some victims access psychiatric units), seafarers’

missions (given their work with fishers in ports),

embassies (given their mandate to assist country

nationals), and village or community institutions

(given that so many victims self-return to their

communities), among others.

22

Identification is very difficult when trafficking

occurs in crisis or conflict settings such as

natural disasters, refugee flight, mass

migrations and pandemics. Forms of

exploitation in crises often differ from

established patterns, making it difficult to

screen victims with existing tools and

procedures. In mass migration flows, for

instance, typical indicators and signals of

trafficking are of variable relevance in

identifying trafficked migrants, asylum seekers and refugees. Screening and identification with this

specific population of trafficking victims requires the development of specific tools, which do not

generally exist.

Practitioners require specific and comprehensive identification tools and procedures

that are tested and regularly revised to keep pace with how trafficking takes places.

Tools and procedures should be tailored to different contexts and complex situations as

well as to different profiles of trafficking victims including children. A wide range of

practitioners have an important role to play in victim identification and referral,

including those not typically considered responsible for victim identification.

What are the tools, protocols and procedures in place to identify victims

in your region/area? Who are the victim identification practitioners in

your region/area?

23

Geographical and practical barriers to identification

Practitioners in some locations (for example,

metropolitan areas) often have more

resources and professional capacity to

conduct victim identification. These

locations are also more likely to have a

dedicated unit or center tasked with

identification. However, many victims do

not live in metropolitan areas and don’t

have money to travel or even to telephone

agencies or hotlines to seek help.

Practitioners also often do not have resources to travel to conduct interviews in rural communities

where victims return to live after trafficking, particularly in lower resourced and geographically vast

countries. Local community institutions that could provide entry points for identification (for example,

health clinics, village administration, schools, youth organizations, religious leaders) are generally not

trained or mandated to conduct victim identification and referral. Lack of community-based

identification opportunities leaves many trafficking victims unidentified and unassisted.

Increasing reach into victims’ home communities including engaging local institutions

in identification will aid practitioners in their work. It is important to explore ways to

overcome geographical and practical barriers to victim identification, including through

the use of technology. How this is done will differ from context to context but is an

important step in identifying more victims of trafficking in a country.

What institutions could assist with victim identification in different locations,

including at the local/village level?

What are the practical barriers you face in reaching victims in different locations,

including at the local/village level?

24

Guidance for Practitioners

Identify different locations where trafficking victims may be exploited, including for different

forms of exploitation and in remote or difficult to access locations. Identify which other practitioners

may have access to these locations to conduct or support identification and cooperate with them in

increasing proactive identification efforts.

Challenge your assumptions and biases about who trafficking victims are and how they behave.

Understand how the effects of trafficking and trauma impact victims’ reactions and behaviors as well

as their willingness to disclose their exploitation and accept identification. Be sensitive in your

interactions with trafficking victims and, when needed, give them time before interviewing.

Increase your knowledge, skills, capacity and confidence to identify and refer trafficking victims,

both adults and children. This includes implementing special measures in identification and referral

such as the presumption of minority age until proven otherwise. Work with colleagues to strengthen

your capacity to understand and apply trafficking definitions to real life situations.

Find out what tools and procedures exist in your region/country to help you identify and refer

trafficking victims. Ensure that you have access to the most current identification and referral materials

to support your work. Be aware of any changes in the legislative and institutional frameworks that

impact who may be identified as a trafficking victim.

Regularly review and revise screening procedures and protocols for victim identification so that

they keep pace with how trafficking takes place in the country. Adjust tools and procedures for victim

identification in less usual contexts such as crisis or conflict settings.

Increase your skills and knowledge in how to sensitively engage with trafficking victims,

including understanding and applying trauma-informed principles. Ensure that you are sensitive and

caring in interacting with trafficking victims, including by creating an environment where victims feel

comfortable to be interviewed. Develop strategies to offset unconducive identification environments.

Learn from trafficking victims about how they experienced victim identification and referral and

identify ways that the process can be improved such as avoiding multiple interviews.

Engage all relevant practitioners from different fields and sectors in the identification process

(preliminary screening, formal identification and referral for assistance and protection). For children

this must include child protection agencies tasked with ensuring the best interests of the child.

Ensure that identified trafficking victims are referred for protection and support. Ensure that

referrals meet the needs of different victims (all genders, ages and characteristics). If you determine

someone is not a trafficking victim but has protection needs, refer them for support. Coordinate with

child protection agencies in all cases of children, whether trafficking victims or otherwise, in need of

protection.

Ensure that practitioners are held to account for failure to identify trafficking victims or to refer

them (or other types of victims) for assistance. Investigate reports of wrong-doing, including by

supervisors, subordinates and colleagues.

Prioritize the proactive identification of victims by making use of existing guidance relevant to

specific contexts and fields of work. Allocate sufficient time and resources to fulfill this task.

25

Notes:

26

Other Bali Process and NEXUS Institute resources on trafficking victim

identification

Bali Process (2015) Policy Guide on Identifying Victims of Trafficking. Bangkok: Regional Support

Office of the Bali Process (RSO). Available at: https://bit.ly/3m6kxT0

Bali Process (n.d.) Assisting and Interviewing Child Victims of Trafficking: A Guide for Law

Enforcement, Immigration and Border Officials. Bangkok: Regional Support Office of the Bali Process

(RSO). Available at: https://bit.ly/3h6FTeZ

Bali Process (n.d.) Quick Reference Guide for Frontline Border Officials. Bangkok: Regional Support

Office of the Bali Process (RSO). Available at: https://bit.ly/2GItMIL

Bali Process (n.d.) Quick Reference Guide on Interviewing Victims of Trafficking in Persons. Bangkok:

Regional Support Office of the Bali Process (RSO). Available at: https://bit.ly/3bHxTAi

NEXUS Institute and Bali Process (2021) Recovery and Reintegration of Trafficking Victims: A

Practitioner Guide. Washington, D.C.: NEXUS Institute and Bangkok: Regional Support Office of the

Bali Process (RSO). Available at: https://bit.ly/3fdGsom

NEXUS Institute and Bali Process (2021) Special and Additional Measures for Child Trafficking Victims:

A Practitioner Guide. Washington, D.C.: NEXUS Institute and Bangkok: Regional Support Office of the

Bali Process (RSO). Available at: https://bit.ly/3fdGsom

NEXUS Institute and Bali Process (2021) Trafficking Victim Protection and Support: A Practitioner

Guide. Washington, D.C.: NEXUS Institute and Bangkok: Regional Support Office of the Bali Process

(RSO). Available at: https://bit.ly/3fdGsom

NEXUS Institute (2020) Identifying Trafficking Victims: An Analysis of Victim Identification Tools and

Resources in Asia. Washington, D.C.: NEXUS Institute and Winrock International. Available at:

https://bit.ly/3bFZDWl

NEXUS Institute (2020) Trafficking Victim Protection Frameworks in Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR,

Thailand, and Viet Nam: A Resource for Practitioners. Washington, D.C.: NEXUS Institute, Winrock

International and USAID. Available at: https://bit.ly/39Kav65

NEXUS Institute (2018) Identification and Referral of Trafficking Victims in Indonesia. Guidelines for

Frontline Responders and Multi-Disciplinary Teams at the Village Level. Washington, D.C.: NEXUS

Institute. Available at: https://bit.ly/3dMT2Mt

NEXUS Institute (2018) Seeing the unseen. Barriers and opportunities in the identification of trafficking

victims in Indonesia. Washington, D.C.: NEXUS Institute. Available at: https://bit.ly/3bN2lcJ

UNIAP and NEXUS Institute (2013) After Trafficking. Experiences and Challenges in the (Re)integration

of Trafficked Persons in the Greater Mekong Sub-region. Bangkok: United Nations Inter-agency Project

on Human Trafficking (UNIAP) and Washington, D.C.: NEXUS Institute. Available at:

https://bit.ly/37KMDwC

iiiiiiivvviviiviiiixxxixiixiiixivxvxvixviixviiixixxxxxixxiixxiiixxivxxvxxvixxviixxviiixxixxxxxxxixxxiixxxiiixxxivxxxvxxxvixxxviixxxviiixxxixxlxlixliixliiixlivxlvxlvixlviixlviiixlixl

27

i

Surtees, R. (2017) Our Lives. Vulnerability and Resilience Among Indonesian Trafficking Victims. Washington,

D.C.: NEXUS Institute, p. 109.

ii

Surtees, R. (2017) Our Lives, p. 99.

iii

Surtees, R. (2017) Our Lives. p. 94.

iv

Surtees, R. (2007) Listening to victims: Experiences of identification, return and assistance in South-Eastern

Europe. Vienna: ICMPD and Washington, D.C.: NEXUS Institute, p. 58.

v

Surtees, R. and T. Zulbahary (2018) Seeing the unseen. Barriers and opportunities in the identification of

trafficking victims in Indonesia. Washington, D.C.: NEXUS Institute. p. 56.

vi

Brunovskis, A. and R. Surtees (2012) Out of sight? Approaches and challenges in the identification of trafficked

persons. Oslo: Fafo and Washington, D.C.: NEXUS Institute, p. 49.

vii

Surtees, R. and T. Zulbahary (2018) Seeing the unseen, p. 56.

viii

Surtees, R. and T. Zulbahary (2018) Seeing the unseen, p. 57.

ix

Surtees, R. and T. Zulbahary (2018) Seeing the unseen, p. 57.

x

Surtees, R. (2017) Moving On. Family and Community Reintegration Among Indonesian Trafficking Victims.

Washington, D.C.: NEXUS Institute, p. 90.

xi

Surtees, R. (2017) Moving On, p. 90.

xii

Brunovskis, A. and R. Surtees (2012) Out of sight?, p. 37.

xiii

Surtees, R. and T. Zulbahary (2018) Seeing the unseen, p. 61.

xiv

Surtees, R. (2007) Listening to victims, p. 213.

xv

Surtees, R. (2007) Listening to victims, p. 65.

xvi

Brunovskis, A. and R. Surtees (2012) Out of sight?, p. 38.

xvii

Surtees, R. and T. Zulbahary (2018) Seeing the unseen, p. 61.

xviii

Brunovskis, A. and R. Surtees (2012) Out of sight?, p. 46.

xix

Surtees, R. (2013) After Trafficking. Experiences and Challenges in the (Re)integration of Trafficked Persons in

the Greater Mekong Sub-region. Bangkok: United Nations Inter-agency Project on Human Trafficking (UNIAP)

and Washington, D.C.: NEXUS Institute, p. 75.

xx

Surtees, R., L.S. Johnson, T. Zulbahary and S.D. Caya (2016) Going home. Challenges in the reintegration of

trafficking victims in Indonesia. Washington, DC: NEXUS Institute, p. 79.

xxi

Surtees, R. (2007) Listening to victims, p. 179.

xxii

Surtees, R. (2017) Moving On, p. 125.

xxiii

Surtees, R. (2013) After Trafficking, p. 60.

xxiv

Baldwin, S.B., D.P. Eisenman, J.N. Sayles, G. Ryan and K.S. Chuang (2011) 'Identification of Human

Trafficking Victims in Health Care Settings', Health and Human Rights, 13(1), p. 9.

xxv

Surtees, R. (2007) Listening to victims, p. 86.

xxvi

Surtees, R. and T. Zulbahary (2018) Seeing the unseen, p. 38.

xxvii

Surtees, R. (2014) In African waters. The trafficking of Cambodian fishers in South Africa. Geneva:

International Organization for Migration (IOM) and Washington, D.C.: NEXUS Institute, p. 123.

xxviii

Surtees, R. and T. Zulbahary (2018) Seeing the unseen, p. 38.

xxix

Farrell, A. and R. Pfeffer (2014) 'Policing Human Trafficking: Cultural Blinders and Organizational Barriers',

The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 653(1).

xxx

Farrell, A. and R. Pfeffer (2014) 'Policing Human Trafficking’.

xxxi

Surtees, R. (2007) Listening to victims, p. 82.

xxxii

Pearce, J., P. Hynes and S. Bovarnick (2009) Breaking the wall of silence: Practitioners' responses to trafficked

children and young people. United Kingdom: University of Bedfordshire, p. 104.

xxxiii

Surtees, R. (2014) In African waters, p. 118.

xxxiv

Brunovskis, A. and R. Surtees (2007) Leaving the past behind. When victims of trafficking decline assistance.

Oslo: Fafo and Washington, D.C.: NEXUS Institute, p. 136.

xxxv

Pearce, J. et al. (2009) Breaking the wall of silence, p. 129.

xxxvi

Surtees, R. (2014) In African waters, p. 116.

xxxvii

Brunovskis, A. and R. Surtees (2012) Out of sight?, p. 41.

xxxviii

Pearce, J. et al. (2009) Breaking the wall of silence, p. 59.

xxxix

Surtees, R. (2007) Listening to victims, p. 80.

xl

Surtees, R. (2007) Listening to victims, p. 59.

xli

Surtees, R. (2007) Listening to victims, p. 101.

xlii

Surtees, R. (2007) Listening to victims, p. 90.

xliii

Surtees, R. (2007) Listening to victims, p. 102.

xliv

Surtees, R. (2007) Listening to victims, p. 102.

xlv

Surtees, R. (2013) After Trafficking, p. 88.

xlvi

Pearce, J. et al. (2009) Breaking the wall of silence, p. 127.

xlvii

Pearce, J. et al. (2009) Breaking the wall of silence, p. 120.

28

xlviii

LEAG (2019) Detaining victims: human trafficking and the UK immigration detention system. United

Kingdom: Labour Exploitation Advisory Group, p. 30.

xlix

Brunovskis, A. and R. Surtees (2017) Vulnerability and exploitation along the Balkan route: Identifying victims

of human trafficking in Serbia. Oslo: Fafo and Washington, D.C.: NEXUS Institute, p. 22.

l

Surtees, R. (2014) In African waters, p. 157.