1

November 13, 2019

Substantial Income of Wealthy Households Escapes

Annual Taxation Or Enjoys Special Tax Breaks

Reform Is Needed

By Chuck Marr, Samantha Jacoby, and Kathleen Bryant

With the nation’s income and wealth highly concentrated at the top and growing more so in

recent decades, policymakers should reconsider how the tax code treats the most well-off. High-

income, and especially high-wealth, filers enjoy a number of generous tax benefits that can

dramatically lower their tax bills. Eliminating or limiting these preferences would make the tax code

more progressive and push back against inequality. It also would raise significant revenue that could

be used to fund key priorities and help address the nation’s fiscal challenges.

A critical tax advantage for wealthy households is that much of their income doesn’t appear on

their annual tax returns because the tax code doesn’t consider it “taxable income.” For example,

taxes on capital gains (the increase in the value of assets such as stocks, real estate, or other

investments) are effectively voluntary to a substantial extent: high-wealth filers may accumulate

capital gains every year as their investments appreciate, but they don’t owe tax on those gains until

— or unless — they “realize” the gain, usually by selling the appreciated asset. Wealthy individuals

can wait to sell until it makes the most sense for them, such as a year in which they will have large

capital losses to offset the gain. And, if a wealthy individual opts instead to pass on her appreciated

assets to her son when she dies, neither she nor her son will ever owe capital gains tax on the assets’

growth in value during her lifetime. In contrast, people who earn their income from work (for

example, from wages or salaries) typically have income and payroll taxes withheld from every

paycheck; if their tax liability for the year exceeds those withheld taxes, they must pay the balance by

the following April 15.

Further, a significant part of the income that does show up on wealthy households’ annual tax

returns is taxed at preferential rates. Capital gains and dividends are taxed at a maximum income tax

rate of 20 percent, far below the 37-percent top rate on wages and salaries.

1

Also, the 2017 tax law

created a new 20-percent deduction for certain pass-through business income (income that the

owners of businesses such as partnerships, S corporations, and sole proprietorships report on their

individual tax returns), which lowers the tax rate on this income by up to 7.4 percentage points. The

1

High-income taxpayers are also subject to a 3.8 percent surtax (known as the Net Investment Income Tax) on capital

gains, dividends, and certain other forms of unearned income, and a 3.8 percent Medicare tax on wages and salaries.

1275 First Street NE, Suite 1200

Washington, DC 20002

Tel: 202-408-1080

Fax: 202-408-1056

www.cbpp.org

2

deduction disproportionately benefits wealthy people: 61 percent of the benefit will ultimately flow

to the top 1 percent of households, the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) estimates. The 2017 law

also slashed the corporate rate from 35 percent to 21 percent, which disproportionately benefits

wealthy shareholders.

The amount of the nation’s income and wealth flowing to the most well-off has increased sharply

in recent decades. (See Figure 1 and box.) Tax policy choices benefiting wealthy filers have

contributed to these disparities. By the same token, new approaches to tax policy can push back

against these trends.

FIGURE 1

Policymakers have a number of ways to raise more revenue from the most well-off. They fall into

two broad categories:

2

• Expanding the types of income considered taxable. For example, instead of waiting to tax

capital gains until assets are sold, the tax code could impose a “mark-to-market” system,

which would impose tax annually on the gain in value of assets that high-income individuals

hold, whether or not they are sold. Policymakers also could repeal the “stepped-up basis” tax

break, which enables wealthy people who have avoided capital gains taxes on the growth of

assets during their lifetimes to pass them to their heirs free of capital gains tax.

• Improving taxation of income already taxed under the current system. For example,

policymakers should repeal the 20 percent pass-through deduction. They also could end or

scale back the preferential rates for capital gains and dividend income by raising their rates to

match or come closer to the prevailing rates on ordinary income, such as wages and salaries.

2

As discussed in detail below, many of the options outlined in this report are complementary and should be enacted

together (such as eliminating stepped-up basis and raising tax rates on capital gains), while others are alternatives (such as

strengthening the estate tax or creating an inheritance tax).

3

And they could broaden the tax base by narrowing or eliminating various unproductive tax

breaks used primarily by large corporations and wealthy individuals, described later in this

report.

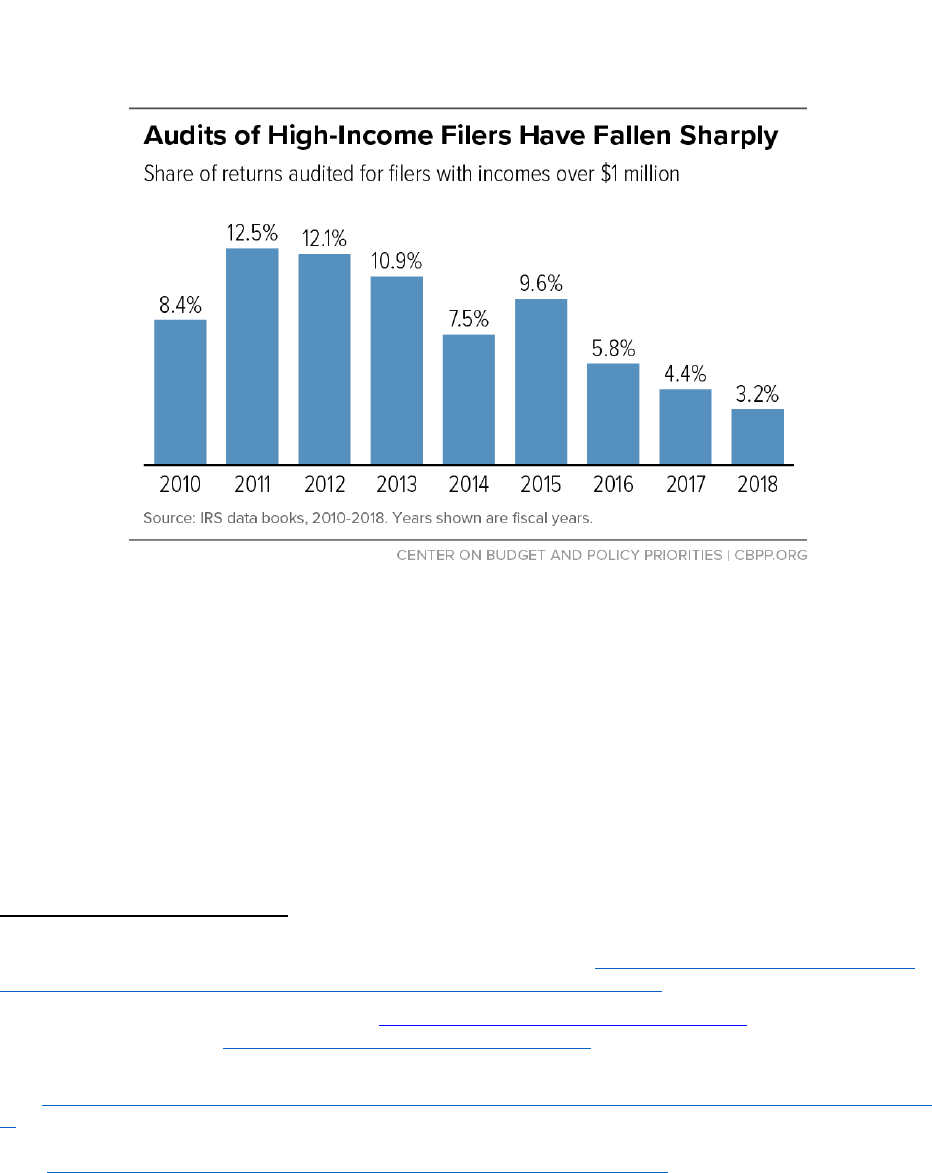

Policymakers also should pursue a parallel effort to rebuild the IRS’ enforcement division and

strengthen tax compliance efforts, which have been dramatically underfunded in recent years. The

agency has fewer revenue agents (auditors who tend to audit the most complex returns) than in 1954,

when the economy was roughly one-seventh its current size. As a result, the IRS in 2018 audited just 3.2

percent of tax returns showing incomes above $1 million, down from 8.4 percent of such returns in

2010. Rebuilding the IRS’ enforcement function will require a multi-year funding commitment to

hire and train auditors and other staff. A reasonable initial goal would be to return funding to its

inflation-adjusted 2010 level over four years.

Income, Wealth Are Highly Concentrated and Growing More So

Income and wealth are highly concentrated at the top and have grown more so in recent decades.

The highest-income 1 percent of households received 12.3 percent of total household income

after taxes and government transfers in 2016, up from 7.4 percent in 1979, according to the

Congressional Budget Office (CBO).

a

The share going to the bottom 80 percent fell over that

period, from 58.4 percent to 53.1 percent.

b

In other words, most of the decline in the bottom 80

percent’s share of household income mirrored the increase in the top 1 percent’s share.

The CBO data only go back to 1979, but estimates from economists Thomas Piketty, Emmanuel

Saez, and Gabriel Zucman show that the top 1 percent’s share of after-tax income has reached a

level not seen since before World War II.

c

Their data also show that the growth of the top 1

percent’s share of income has largely occurred among households at the very top: the top 0.1 and

0.01 percent.

Wealth inequality, which is even more pronounced than income inequality, has also grown in

recent decades, according to the Federal Reserve’s Survey of Consumer Finances, the main

source of data for the distribution of household wealth. The wealthiest 1 percent of households

held 39.6 percent of wealth in 2016, up from 33.8 percent in 1983 — an increase representing

trillions of dollars. The bottom 80 percent’s share fell from 18.7 percent to 10.1 percent over that

4

Income From Wealth Is Taxed More Lightly Than Income From Work

To understand how the tax code taxes income from wealth more lightly than income from work,

one must first distinguish between labor income (such as wages, salaries, and employer-provided

benefits), which flows from work, and capital income (such as dividends, interest, rental income, and

capital gains), which flows from ownership of assets.

Most Americans primarily earn labor income; it constitutes at least 80 percent of the total income

for each of the four bottom income quintiles, according to CBO.

3

(See Figure 2.) The vast majority

of this labor income is wages and salaries, which are taxed at ordinary income rates.

3

“Income” is defined in this discussion about capital and labor income as what CBO calls “market income” and omits

taxes and transfers. CBO’s definition of labor income does not include profits from pass-through businesses.

period.

d

Data from Saez and Zucman also show that wealth inequality has reached levels not seen

since before World War II and has been driven by a rapidly escalating share of wealth for

households in the top 0.5 percent.

e

The heavy concentration of income and wealth has an important racial dimension, because

households of color are overrepresented at the lower end of the income and wealth distributions

while white households are overrepresented among the wealthy. For example, 25 percent of all

households were Latino or Black in 2016, but they represented 34 percent of the least wealthy 60

percent of households and less than 10 percent of the wealthiest 1 percent.

f

These inequities are

rooted in policies that have been shaped by historic and ongoing racism and limit opportunity for

households of color.

g

a

Congressional Budget Office, “The Distribution of Household Income, 2016,” July 9, 2019,

https://www.cbo.gov/publication/55413. Income shares have been recalculated to exclude households with negative

income.

b

Ibid.

c

Thomas Piketty, Emmanuel Saez, and Gabriel Zucman, “Distributional National Accounts: Methods and Estimates for

the United States,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 133, No. 2, 2018. This study measures income inequality

differently than the CBO estimates. For instance, CBO uses Census data and IRS tax return data to estimate household

income both before and after taxes. The Piketty, Saez, and Zucman estimates incorporate the portion of national income

not captured in tax or survey data into the analysis of income inequality. That is, Piketty, Saez, and Zucman look at

income flows in the broader economy and attempt to assign those income flows to households even if they don’t show

up on tax returns or in survey data.

d

Edward N. Wolff, “Household Wealth Trends in the United States, 1962 to 2016: Has Middle Class Wealth

Recovered?,” NBER Working Paper 24085, November 2017, https://www.nber.org/papers/w24085.pdf. Wolff

calculates wealth shares using Survey of Consumer Finances data, but his numbers differ slightly from those published

by the Federal Reserve due to differences in how “net worth” is defined. For example, Wolff excludes vehicles from his

definition of household wealth.

e

Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman, “Wealth Inequality in the United States Since 1913: Evidence from Capitalized

Income Tax Data,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 131, No. 2, May 2016, http://gabriel-

zucman.eu/files/SaezZucman2016QJE.pdf.

f

Chye-Ching Huang and Roderick Taylor, “How the Federal Tax Code Can Better Advance Racial Equity,” Center on

Budget and Policy Priorities, July 25, 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/how-the-federal-tax-code-can-

better-advance-racial-equity.

g

Ibid. See also Angela Hanks, Danyelle Solomon, and Christian E. Weller, “Systematic Inequality: How America’s

Structural Racism Helped Create the Black-White Wealth Gap,” Center for American Progress, February 21, 2018,

https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/race/reports/2018/02/21/447051/systematic-inequality/; Michael

Leachman et al., “Advancing Racial Equity with State Tax Policy,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, November 15,

2018, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/advancing-racial-equity-with-state-tax-policy.

5

FIGURE 2

For the top 1 percent of households, in contrast, capital income — most of which enjoys

preferential tax rates

4

— constitutes 41 percent of their taxable incomes, while labor income makes

up just 34 percent, according to CBO.

5

Most of the remaining 25 percent is pass-through business

profits,

6

which are usually a combination of labor and capital income and also enjoy special tax

preferences.

7

This means that most of the taxable income of the top 1 percent receives favorable tax

4

A small share of high-end income — about 4 percent of the income of the top 1 percent — consists of interest

payments, which are a form of capital income but are taxed at ordinary income tax rates.

5

Congressional Budget Office, “The Distribution of Household Income, 2016,” July 9, 2019,

https://www.cbo.gov/publication/55413. Income shares have been recalculated to exclude households with negative

income.

6

The remaining 3 percent is what CBO calls “other market income,” which consists of retirement income and other

nongovernmental sources of income.

7

It’s not always clear whether income represents capital income or labor income. This is especially true for the pass-

through business income of owners who work for the companies they own, because their compensation is, by definition,

a mixture of capital and labor. The owner of a major beer distributor, for example, invests capital in warehouses and

trucks, and some of the profits reflect the return on that investment. But she may also contribute labor to the business

— recruiting employees, managing the accounting records, and seeking new business opportunities, for example. These

6

rates. Moreover, these figures omit unrealized capital gains, which as noted, often don’t face income

tax for years, if ever, and are highly concentrated in the top 1 percent.

The importance of capital income for households at the top not only helps explain why the tax

code contains so many provisions that tilt in their favor, but also has important implications for

designing effective policies to raise revenue in a progressive manner, as discussed below.

Tax Code Allows Wealthy to Exclude Much of Their Income from Tax Returns

Much of the income of the very well off never appears on their tax returns. Workers typically have

income and payroll taxes withheld from every paycheck; this withheld income shows up on their tax

returns when they reconcile how much they owe by April 15 each year. But that’s not the case for

the investment income for wealthy households, because policymakers have given them several ways

to delay income tax or even avoid it altogether.

Deferral of Capital Gains Income

Unlike other types of income, like wages, the amount of capital gain claimed on a tax return is

often effectively voluntary due to the “realization principle,” which means that a capital gain is only

taxed when the capital gain is “realized,” typically when the asset is sold. Only part of capital gains

are realized in any given year. The rest are deferred, and no tax is immediately due, even if the

unrealized capital gain makes up a significant share of a household’s income as reflected in the

growth of its net worth.

The ability to defer capital gains taxes confers three benefits on taxpayers who can take advantage

of this tax break:

• Instead of paying taxes each year on their capital gains, they can continue earning returns on

the money that they would have paid in tax, and these returns compound over time. Delaying

by decades the day when taxes are due is a large benefit.

• They can wait to sell assets until doing so is beneficial for other tax reasons. They may wait,

for example, until a year in which they will be in a lower tax bracket or will have large capital

losses to offset the gains, or they may hold on to assets in hopes of a future capital gains tax-

rate cut. Wage earners typically do not have this option since they owe tax on their income in

the year they receive it.

• They can take advantage of many of the other tax benefits for capital gains discussed below,

such as stepped-up basis.

This deferral option disproportionately benefits wealthy households. Not only do they receive the

large bulk of capital gains (see discussion below), but unrealized capital gains make up 34 percent of

the assets of the wealthiest 1 percent of households, which held $6.6 million in unrealized capital

activities also help generate the company’s profits but reflect a return on her labor rather than on her investment. When

she reports her profits on her individual tax return, she will enjoy special privileges on the total profit, even though a

large share of it likely reflects her labor. An important new paper estimates that three-quarters of the pass-through

profits that wealthy households receive are properly considered labor income instead of capital income. Matthew Smith

et al., “Capitalists in the Twenty-First Century, National Bureau of Economic Research, NBER Working Paper No.

25442, January 2019, https://www.nber.org/papers/w25442.

7

gains apiece, on average, in 2013. The comparable figures for households in the bottom 90 percent

are just 6.1 percent and $9,000, respectively.

8

Not surprisingly, many wealthy households take advantage of this very generous tax break.

Research in the 1980s by Eugene Steuerle (now with the Tax Policy Center) found that less than

one-third of overall capital income (including unrealized gains) was reported on individual tax

returns.

9

And an important 2018 paper by Jenny Bourne, Steuerle, and others found that over the

2002-2006 period, when the stock market was delivering annual returns of 7-8 percent after

adjusting for inflation, wealthy people were reporting taxable returns on their wealth of “less than 3

percent and the predominant rate was in the 1 to 2 percent range.”

10

The authors concluded that

“these results are consistent with earlier work . . . indicating that in aggregate most capital income is

not reported on tax returns.”

11

The latter study also found that the share of income that households report on their tax returns

declines as one moves up the wealth scale.

12

Berkshire Hathaway Chairman Warren Buffett is one

example.

13

The value of Buffett’s main asset, Berkshire Hathaway stock, rose over 17 percent in

2010, from approximately $34.8 billion to $42 billion.

14

These figures imply income of roughly $7.2

billion. Yet in his tax returns for 2010 (which he made public via a letter to former Congressman

Tim Huelskamp), Buffet’s adjusted gross income was $62.8 million, or less than 1 percent of that

amount.

15

8

Adam Looney and Kevin B. Moore, “Changes in the Distribution of After-Tax Wealth: Has Income Tax Policy

Increased Wealth Inequality?,” Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Finance and Economics Discussion

Series 2015-058, 2015, https://www.federalreserve.gov/econresdata/feds/2015/files/2015058pap.pdf. These capital

gains figures omit unrealized capital gains on primary residences, which have a $500,000 per couple tax exclusion.

9

Eugene Steuerle, “Wealth, Realized Income, and the Measure of Well-Being,” in Martin David and Timothy Smeeding,

eds., Horizontal Equity, Uncertainty, and Economic Well-Being, 1985,

https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/alfresco/publication-pdfs/1001573-Wealth-Realized-Income-and-the-

Measure-of-Well-Being.PDF.

10

Jenny Bourne et al., “More Than They Realize: The Income of the Wealthy,” National Tax Journal, June 2018.

11

Ibid. The calculation of capital gain does not take inflation into account, so some portion of the taxable capital gain

reflects inflation instead of a real gain. Some bills introduced in the House and Senate would exclude that portion from

taxation, thereby creating a costly tax cut concentrated among the most affluent households with capital gains. The

Trump Administration has also considered whether it can index capital gains through regulation. Chye-Ching Huang and

Kathleen Bryant, “Indexing Capital Gains for Inflation Would Worsen Fiscal Challenges, Give Another Tax Cut to the

Top,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, September 6, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-

tax/indexing-capital-gains-for-inflation-would-worsen-fiscal-challenges-give

12

Ibid.

13

Matt Krantz, “Warren Buffett calls Trump’s bluff, releases his tax returns,” USA Today, October 10, 2016,

https://www.usatoday.com/story/money/markets/2016/10/10/warren-buffett-disputes-trumps-tax-

claims/91859962/.

14

CBPP calculations based on Berkshire Hathaway’s Form Def 14A filings with the SEC and public share price data

from 2010.

15

The letter is available at https://money.cnn.com/news/storysupplement/buffett-letter-to-huelskamp/?iid=EL.

8

Or consider Jeff Bezos, the founder of Amazon. The company’s filings with the Securities and

Exchange Commission (SEC) show that he receives an annual salary of $81,840,

16

which is subject

to ordinary income taxes each year.

17

As founder, however, Bezos owns a significant share of

Amazon stock.

18

The value of Bezos’s Amazon holdings grew by more than $100 billion over the

last decade, making him the world’s wealthiest person.

19

This $100 billion in income is only taxed

when — or if — Bezos decides to sell some of his stock. This ability to defer tax on one’s primary

source of income effectively makes the income tax largely voluntary for most of the income that

people like Bezos receive, unlike for the salary income that middle-income people live on. Bezos

sold Amazon shares worth roughly $6.3 billion between 2009 and 2018, according to SEC filings,

20

but the tax code ignores the rest of his $100 billion gain. Thus, his tax bill on a decade of stock sales

likely was about $1.5 billion, or less than 1.5 percent of his increase in wealth due to the appreciation

of his Amazon stock.

Wealthy owners of profitable corporations can choose to never sell their valuable stock and

therefore avoid paying tax throughout their lives. If they need access to large amounts of cash, they

have plenty of options besides selling their shares. Larry Ellison, the CEO of Oracle and one of the

world’s richest people, pledged a portion of his Oracle stock as collateral for a $10 billion credit

line.

21

In other words, he can borrow up to $10 billion, and if he fails to repay the debt, the bank can

seize his Oracle shares. This lets him obtain cash without selling his shares; thus, he avoids paying

taxes, and the stock can continue growing in value. Though he must pay interest on the debt and

eventually pay back amounts borrowed, this is often a much cheaper strategy than selling stock and

paying capital gains taxes, particularly when interest rates are low.

These examples show that, as a recent study explained, “[i]t is a simple fact that billionaires in

America can live very extraordinarily well completely tax-free off their wealth. It is equally a simple

fact that people who live off paid wages cannot do so.”

22

Targeted Capital Gains Tax Breaks

The tax code contains other ways to defer or avoid capital gains tax. These special tax breaks are

often targeted to a specific industry, such as real estate, or are intended to encourage certain types of

supposedly socially beneficial investments, but instead often reward wealthy investors for making

investments they likely would have made anyway.

16

Amazon.com, Inc. Form Def 14A,

https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1018724/000119312519102995/d667736ddef14a.htm.

17

According to Amazon’s SEC filings, Bezos also receives approximately $1.6 million in annual fringe benefits, the value

of a portion of which would also be subject to ordinary income taxes.

18

As of February 25, 2019, Bezos owned 16 percent of Amazon’s common stock. Amazon.com, Inc. Form Def 14A,

https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1018724/000119312519102995/d667736ddef14a.htm

19

Katie Warren, “9 Mind-Blowing Facts That Show Just How Wealthy Jeff Bezos, the World’s Richest Man, Really Is,”

Business Insider, May 2, 2019, https://www.businessinsider.com/how-rich-is-jeff-bezos-mind-blowing-facts-net-worth-

2019-4.

20

CBPP calculations based on Jeff Bezos’s Form 4 filings with the SEC.

21

Julie Bort, “Larry Ellison Has Secured $10 Billion Worth of Credit for His Personal Spending,” Business Insider,

September 26, 2014, https://www.businessinsider.com/larry-ellison-has-a-10b-credit-line-2014-9.

22

Edward J. McCaffery, “The Death of the Income Tax (or, the Rise of America’s Universal Wage Tax),” Indiana Law

Journal, forthcoming, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3242314.

9

One example is the “like-kind exchange” loophole, which allows people to sell certain types of

assets and still avoid paying tax on the realized capital gain in the year of the sale. Originally meant

to exempt small-scale and barter transactions (such as farmers trading horses) from taxation, like-

kind exchanges are now used extensively in the commercial real estate industry.

For example, suppose an investor buys a small office building for $10 million and its value rises

over time to $15 million. She thinks it has little additional potential to gain in value and wishes to

invest in real estate somewhere else. If she sells the building for $15 million, she’ll owe tax on the $5

million capital gain. But if she exchanges it for a ski lodge, for example, the $5 million won’t be

subject to tax until she sells the ski lodge — and she could continue deferring tax by exchanging that

property for yet another.

The 2017 tax law eliminated like-kind exchanges for certain assets (such as vehicles, equipment,

and artwork) but retained them for real estate, so wealthy real estate investors can continue to sell

buildings without claiming the gains from those sales on their income tax returns. In fact, they can

buy and sell properties throughout their lives and never pay tax on the gains — and then combine

this tax avoidance with stepped-up basis at death to avoid tax liability completely, as the next section

of this paper explains.

Another example is the opportunity zone tax break created by the 2017 tax law, which lets

investors defer taxes that they would otherwise owe on capital gains if they invest in designated low-

income areas. If investors hold on to their opportunity zone investments for a certain number of

years, they can qualify for additional tax breaks — including a permanent capital gains tax exemption

on future gains on their opportunity zone investments. The opportunity zone tax break was

promoted as a measure that would encourage substantial new investment in low-income areas, but it

doesn’t require investors to make investments that actually produce public benefits. This raises

questions about whether its main effect will be simply to boost investors’ profits.

23

Yet another example is the tax break for investing in so-called “qualified small business stock,”

which allows early investors in corporations to avoid capital gains taxes when they sell their stock.

This tax break often fails to target truly small businesses (which are typically organized as pass-

through entities rather than corporations and thus do not qualify for this tax break). Instead, it often

serves as a large tax break for investors in successful tech startups, which likely could have attracted

sufficient capital even without qualified small business stock.

24

Furthermore, the combination of the

qualified small business stock tax break and the 2017 tax law’s large corporate rate cut created what

23

Samantha Jacoby, “Potential Flaws of Opportunity Zones Loom, as Do Risks of Large-Scale Tax Avoidance,” Center

on Budget and Policy Priorities, January 11, 2019, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/potential-flaws-of-

opportunity-zones-loom-as-do-risks-of-large-scale-tax. See also Jesse Drucker and Eric Lipton, “How a Trump Tax

Break to Help Poor Communities Became a Windfall for the Rich,” New York Times, August 31, 2019,

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/08/31/business/tax-opportunity-zones.html.

24

Ben Steverman, “When an Eight-Figure IPO Windfall Can Mean a Zero-Digit Tax Bill,” Bloomberg, June 10, 2019,

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-06-10/silicon-valley-wins-big-with-tax-break-aimed-at-small-

businesses.

10

one accounting firm called a “supercharged tax planning opportunity”

25

that may cause more

companies to form as corporations in order to benefit from the tax break.

Stepped-Up Basis

One of the tax code’s largest subsidies for capital gains is the stepped-up basis tax break. If an

investor holds on to an asset (such as stock) and passes it on to an heir instead of selling it, neither

she nor her heir owes capital gains tax on its increase in value during her lifetime. (Technically, the

asset’s basis — or the price paid for it — is “stepped up” to its fair market value at the time of

inheritance.) Stepped-up basis encourages wealthy people to turn as much of their income into

capital gains as possible and hold on to assets until death, when a lifetime of gain becomes

permanently exempt from tax. (The asset, however, may be subject to the estate tax, as explained

below.)

Combined with the benefits of deferral and the other targeted capital gains tax breaks discussed

above, stepped-up basis allows large corporate stockholders and other wealthy investors to pay no

income tax on the increase in assets’ value during their lifetimes and then pass the assets on to their

heirs, who pay no income tax on those inheritances. For example, Steve Jobs, the former Apple

CEO, received an annual salary of $1, as reported on the company’s SEC filings.

26

Instead of a

traditional salary, he received shares of Apple stock worth $75 million in the early 2000s.

27

He likely

paid ordinary income tax on the value of those shares when he received them as income. But

because he never sold the shares during his lifetime, he never paid tax on the subsequent massive

gain as Apple’s stock skyrocketed.

28

At his death, Jobs’ Apple stock was worth roughly $2 billion,

and all of that gain was permanently exempt from income tax.

Weakened Estate Tax

Many people may assume that all income faces the income tax, meaning that wealthy people pay

tax on their income throughout their lives. But that’s not how it works. As explained above, wealthy

people can permanently avoid federal income tax on capital gains, one of their main sources of

income, and heirs pay no income tax on their windfalls.

The estate tax provides a last opportunity to collect some tax on income that has escaped the

income tax. The amount of income involved is considerable: more than half of the value of the

largest estates is unrealized capital gains income that has never been taxed. (See Figure 3.) The estate

tax, therefore, serves as an important backstop to the income tax.

25

Joel Boff and Jay Anand, “The Power of Section 1202 — Everything Old Is New Again,” CohnReznick, March 26,

2018, https://www.cohnreznick.com/insights-and-events/insights/the-power-of-section-1202-everything-old-is-new-

again.

26

Apple, Inc., Form Def 14A, https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/320193/000119312511003231/ddef14a.htm.

27

Brett Arends, “Steve Jobs Was Robbed,” MarketWatch, May 18, 2010, https://www.marketwatch.com/story/apples-

steve-jobs-blunders-on-options-swap-2010-05-18.

28

David S. Miller, “The Zuckerberg Tax,” New York Times, February 7, 2012,

https://www.nytimes.com/2012/02/08/opinion/the-zuckerberg-tax.html.

11

In addition, the estate tax could push back

against inequality by imposing some tax on the

windfall an heir receives. Though levied on the

estate, the tax effectively falls on heirs, research

shows.

29

Large inheritances play a significant role

in the concentration of wealth: they represent

roughly 40 percent of all wealth and account for

more than half of the correlation between

parents’ wealth and that of their children.

30

Despite the need for a robust estate tax, a

decades-long political effort to undermine the

estate tax has severely weakened it.

31

Most

recently, the 2017 tax law doubled the amount

that a wealthy couple can pass tax-free to their

heirs, from $11 million to $22 million, and

indexed these thresholds for inflation going

forward. Today, fewer than 1 in 1,000 estates are

expected to owe any estate tax.

32

Moreover, the few estates large enough to

potentially face the tax can use loopholes to

reduce or eliminate their estate tax liability, such

as by artificially valuing their assets at less than

their true value. (For example, the “minority ownership discount” allows an estate that owns a

minority share of a business to value — and therefore pay estate taxes on — the estate’s share of the

business below its fair market value.

33

) IRS researchers analyzing the estate tax returns of deceased

prior members of Forbes magazine’s annual list of the 400 wealthiest Americans concluded that on

average, their wealth as reported for tax purposes was roughly half of Forbes’ estimate of their

wealth.

34

29

Lily Batchelder, “The Silver Spoon Tax: How to Strengthen Wealth Transfer Taxation,” Washington Center for

Equitable Growth, October 31, 2016, https://equitablegrowth.org/silver-spoon-tax/.

30

Ibid.

31

Public Citizen and United for a Fair Economy, “Spending Millions to Save Billions: The Campaign of the Super

Wealthy to Kill the Estate Tax,” April 2006, https://www.citizen.org/wp-content/uploads/estatetaxfinal.pdf.

32

Roderick Taylor, “New Estate Tax Cut Encourages More Wealthy Individuals to Skirt Capital Gains Tax,” Center on

Budget and Policy Priorities, May 17, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/new-estate-tax-cut-encourages-more-wealthy-

individuals-to-skirt-capital-gains-tax.

33

For purposes of estate and gift taxes, taxpayers may value minority ownership interests in closely held businesses at

below their fair market value, on the grounds that such ownership interests are presumably less valuable than a

controlling interest. The Treasury Department under President Obama proposed a regulation that would have restricted

this tactic for avoiding the estate tax, but the Treasury Department under President Trump withdrew it. See Richard

Rubin, “U.S. Treasury to Withdraw Proposed Tax Rules on ‘Valuation Discounts,’” Wall Street Journal, October 4, 2017,

https://www.wsj.com/articles/u-s-treasury-to-withdraw-proposed-tax-rules-on-valuation-discounts-1507147280.

34

Brian Raub, Barry Johnson, and Joseph Newcomb, “A Comparison of Wealth Estimates for America’s Wealthiest

Decedents Using Tax Data and Data from the Forbes 400,” https://www.ntanet.org/wp-

FIGURE 3

12

Another common planning technique is to use grantor retained annuity trusts (GRATs) to pass

along considerable assets tax-free. Under this tax break, a wealthy individual puts assets such as

stock or real estate into a trust in return for a stream of fixed payments, typically over two years, that

total the initial value of those assets plus interest at a rate set by the Treasury. If the assets in the

trust rise in value by more than the Treasury rate, the gain goes to the trust beneficiary (such as the

trust owner’s child) tax-free. If the assets don’t rise in value by more than the Treasury rate, the

assets still go back to the trust owner through the fixed payments received. Such techniques have

been described as a “heads I win, tails we tie” bet.

35

The Walton family successfully fought the IRS

in court to exploit this loophole,

36

and casino owner Sheldon Adelson was estimated at one point of

having used multiple GRATs that will ultimately allow him and his heirs to bypass the estate tax on

$7.9 billion in wealth.

37

This device reportedly is also popular among wealthy Silicon Valley and Wall

Street financiers.

38

Putting all these tax breaks together, wealthy people can escape taxation on much of their capital

income throughout their lives and have their income tax liability on these gains wiped out at death.

They also can use loopholes to reduce or eliminate their estate tax liability. And their heirs owe no

income tax on those inheritances — even though other types of earned and unearned income, such

as lottery or gambling winnings, face income taxes. Thus, massive fortunes can accumulate across

generations largely tax-free.

Even Taxable Income Often Enjoys Advantages

Even the income that wealthy people have to include on their annual tax returns often enjoys

favorable tax treatment. This includes a top tax rate that’s low by historical standards, a substantially

lower rate for capital gains than for wages and salaries, and a new deduction for certain pass-through

income.

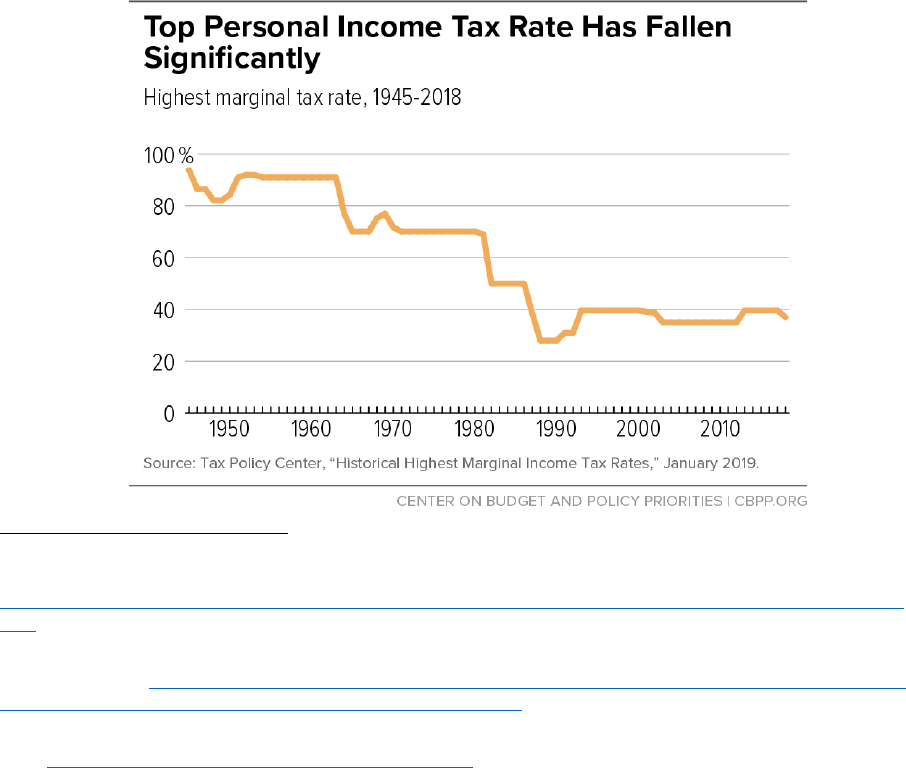

Top Tax Rate

The top income tax rate — which applies not only to wages and salaries but also interest, stock

options, and some pass-through business income — is 37 percent, which is well below the post-

World War II average of 59 percent.

39

During the early postwar decades, a time of both robust

economic growth and broadly rising living standards, the top rate was 70 percent or higher, although

content/uploads/proceedings/2010/020-raub-a-comparison-wealth-2010-nta-proceedings.pdf. The researchers noted

that some of the variation between the Forbes estimates and the estate tax return data was the result of methodological

differences, particularly with respect to assets held in trust and the joint wealth of spouses.

35

Bloomberg, “How to Preserve a Family Fortune Through Tax Tricks,” September 12, 2013,

https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/infographics/how-to-preserve-a-family-fortune-through-tax-tricks.html.

36

Zachary R. Mider, “GRAT Shelters: An Accidental Tax Break for America’s Wealthiest,” Washington Post, December

28, 2013, https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/grat-shelters-an-accidental-tax-break-for-americas-

wealthiest/2013/12/27/936bffc8-6c05-11e3-a523-fe73f0ff6b8d_story.html?utm_term=.e813fadf5c13.

37

Matthew Heimer, “How Billionaires Beat the Estate Tax,” MarketWatch, December 20, 2013,

http://blogs.marketwatch.com/encore/2013/12/20/how-billionaires-beat-the-estate-tax/.

38

Ibid; Deborah L. Jacobs, “Zuckerberg, Moskovitz Give Big Bucks to Unborn Kids,” Forbes, March 7, 2012

https://www.forbes.com/sites/deborahljacobs/2012/03/07/facebook-billionaires-shifted-more-than-200-million-gift-

tax-free/#6b200f316c9f.

39

Tax Policy Center, “Historical Highest Marginal Income Tax Rates,” January 18, 2019,

https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/statistics/historical-highest-marginal-income-tax-rates.

13

much income escaped that rate. (See Figure 4.) In recent decades, a period of surging incomes at the

top and stagnant working-class incomes,

40

it has been considerably lower. Most recently, the 2017

tax law reduced it from 39.6 percent to 37 percent for married couples with taxable incomes above

$600,000, exclusively benefiting the top 1 percent.

In addition, the income threshold at which the top bracket kicks in does an increasingly poor job

of differentiating between the wealthy and the extremely wealthy. Between 1913 and 1970, the

income level at which the top rate took effect was usually well above the threshold for the top 0.1

percent (and in most years, even the top 0.01 percent), a recent analysis by The Washington Post

found.

41

Yet, starting in the 1970s, the top bracket threshold began to fall relative to the incomes of

those extremely wealthy groups. Today, the top bracket begins at $600,000 for a married couple,

which is modestly above the threshold for the top 1 percent (roughly $480,000 in adjusted gross

income in 2015

42

) but well below the $2 million threshold for the top 0.1 percent.

Someone making $600,000 has a high income by any reasonable measure, but that is still much

smaller than $7 million or $70 million. Yet the tax code fails to distinguish between these different

levels of affluence by imposing gradually higher marginal tax rates on them.

FIGURE 4

40

Chuck Marr, Chye-Ching Huang, and Brendan Duke, “Tax Plans Must Not Lose Revenue and Should Focus on

Raising Working-Class Incomes,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, September 8, 2017,

https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/tax-plans-must-not-lose-revenue-and-should-focus-on-raising-working-

class.

41

Christopher Ingraham, “The tax code treats all 1 percenters the same. It wasn’t always this way,” Washington Post,

February 11, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/us-policy/2019/02/11/tax-code-treats-all-percenters-same-it-

wasnt-always-this-way/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.a813add1a40f.

42

Adrian Dungan, “Individual Income Tax Shares, 2016,” Internal Revenue Service Statistics of Income Bulletin, Winter

2019, https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-soi/soi-a-ints-id1901.pdf.

14

Capital Gains Rate

Much of wealthy households’ taxable income is taxed at lower rates than ordinary income. A

prime example is long-term capital gains, which today are taxed at 20 percent, plus a 3.8 percent

surtax known as the Net Investment Income Tax (NIIT).

43

This means that not only is the tax on

capital gains largely voluntary (since it is only paid when taxpayers sell assets), but when investors

actually pay it, they get a special low rate.

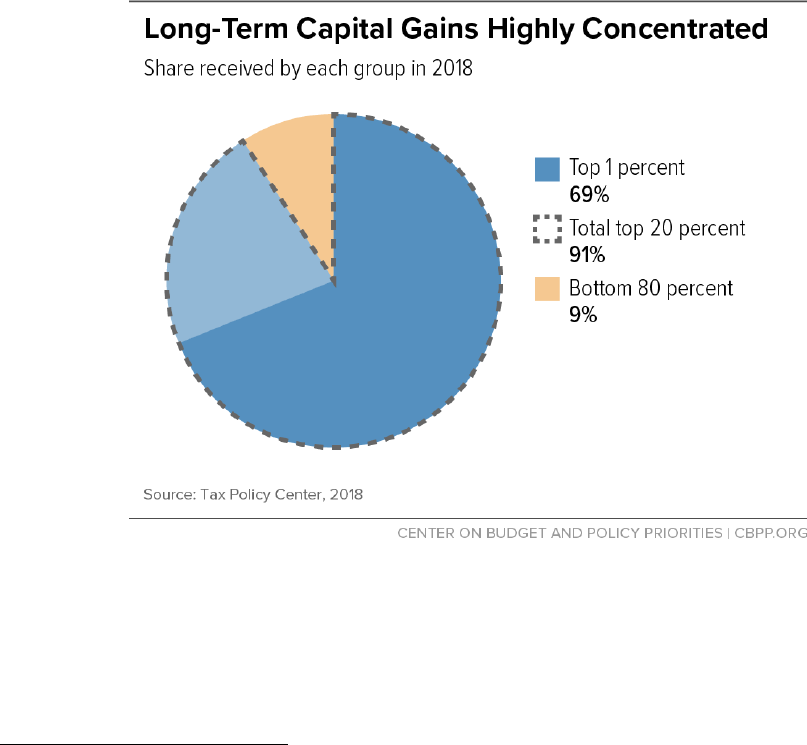

This rate is particularly important to the wealthiest households because capital gains are so

concentrated. The top 1 percent received 69 percent of the taxable long-term capital gains in 2018 (see

Figure 5), according to the Tax Policy Center. More than half went to the top 0.1 percent alone. And

while 3 in 4 households in the top 0.1 percent reported taxable capital gains income in 2018, fewer

than 1 in 20 households in the bottom 60 percent did.

44

(These figures omit unrealized capital gains,

which likely are even more concentrated at the top.)

FIGURE 5

Dividends Rate

A special tax rate for capital gains income is a longstanding tax break for investors; the low tax

rate on dividends is much more recent. Historically, dividends were taxed at the same rates as wage

and salary income, as well as most interest income. This changed in 2003, when policymakers

43

High-income individuals owe the NIIT on their income from capital gains, dividends, and other types of capital

income.

44

TPC Table T18-0231.

15

temporarily cut the top rate on qualified dividends

45

from 38.6 percent to 15 percent; they later set a

permanent rate of 20 percent. Like capital gains, dividends are subject to the 3.8 percent NIIT.

Therefore, qualified dividends are taxed at the same special low rate as long-term capital gains.

Proponents argue that a low tax rate on dividends promotes investment and job creation, but a

landmark study by University of California, Berkeley Professor Danny Yagan found that the 2003

dividend tax rate cut “caused zero change in corporate investment and employee compensation”

46

while providing a windfall to high-income people. Dividend income is highly concentrated: 46

percent of qualified dividend income flows to the top 1 percent of households, and 28 percent flows

to the top 0.1 percent.

47

Nearly 89 percent of the top 0.1 percent of households have dividend

income, compared to just 7.9 percent of the bottom 60 percent of households.

48

The combination of lower rates on both dividends and capital gains creates a large subsidy for

wealthy investors. More than half of the tax benefits from these lower rates go to the top 0.1 percent

of households; less than 5 percent go to the bottom 60 percent of households.

49

In 2018, the lower

rates raised after-tax incomes for the top 0.1 percent by $554,000 apiece (7.4 percent), on average,

the Tax Policy Center estimates, compared to less than $30 for households in the bottom 60

percent.

50

(See Figure 6.)

FIGURE 6

45

To qualify for the lower tax rate on dividends, the stock paying the dividend must be held for a certain period of time

and be the stock of a U.S. company or a qualifying foreign company.

46

Danny Yagan, “Capital Tax Reform and the Real Economy: The Effects of the 2003 Dividend Tax Cut,” American

Economic Review, Vol. 105, No. 12, December 2015, https://eml.berkeley.edu/~yagan/DividendTax.pdf.

47

TPC Table T18-0231.

48

Ibid.

49

TPC Table T18-0187.

50

Ibid.

16

Pass-Through Deduction

Historically, pass-through businesses — including partnerships, S corporations, and sole

proprietorships — have offered a major tax advantage over corporations. The federal government

taxes corporate income twice: profits are taxed first at the business level (through the corporate

income tax), and after-tax profits are taxed a second time to the extent that shareholders receive

them as dividends. Pass-through income, on the other hand, “passes through” the business and is

taxed only once, on the returns of the business’s owners — at the same rates that would apply if the

owners earned the income directly.

Thus, before the 2017 tax law sharply cut the corporate rate,

the combined federal tax rate on

corporate income (including the corporate tax and the tax rate on dividends) was significantly higher

than the top rate on pass-through income.

51

Largely as a result, pass-through businesses have

replaced corporations as the dominant form of business, earning more than 52 percent of all

business income in 2012, up from less than 20 percent in 1980.

52

Proponents of tax cuts for pass-through businesses often hold up small businesses as the intended

beneficiaries. Most pass-through businesses are indeed small and typically make modest profits, but

pass-through income is highly concentrated. Partnerships, a common pass-through structure, are one

example: 69 percent of partnership income flows to the top 1 percent of households.

53

Many large,

profitable businesses are structured as pass-throughs — including financial firms such as hedge

funds and private equity firms, real estate businesses, oil and gas companies, and large multinational

law and accounting firms — and they generate the bulk of pass-through income.

As noted, the 2017 tax law created a 20 percent deduction for certain pass-through income. The

deduction is worth much more, per dollar deducted, to high-income business owners than to small

business owners with modest incomes because the former are in higher tax brackets. And because

high-income households receive the bulk of pass-through income, the deduction’s overall tax benefits

are heavily tilted to the top as well: 61 percent of the tax benefits from the deduction will go to the

top 1 percent of households in 2024, JCT estimates, while just 4 percent will go to the bottom two-

thirds of households.

54

51

Corporations previously faced a 35 percent top tax rate, plus a 23.8 percent top tax rate on dividends paid to

shareholders, for a total blended tax rate of 50.47 percent. The 2017 law lowered the top corporate tax rate to 21

percent, so the combined rate on corporate income is now 39.8 percent. It also lowered the top individual tax rate (that

is, the top rate paid on a wealthy business owner’s pass-through business income) from 39.6 percent to 37 percent, plus

in some cases, the 3.8 percent Medicare tax, though some pass-through owners are exempt from that tax. Furthermore,

with the 20 percent pass-through deduction, a pass-through owner’s tax rate can be reduced to 29.6 percent (or 33.4

percent, if the Medicare surtax applies).

52

Jason DeBacker and Richard Prisinzano, “The Rise of Partnerships,” Tax Notes, July 2, 2015,

https://www.taxnotes.com/tax-notes-today/partnerships-and-other-passthrough-entities/rise-

partnerships/2015/07/02/fw1y?highlight=debacker.

53

Michael Cooper et al., “Business in the United States: Who Owns It, and How Much Tax Do They Pay?,” Tax Policy

and the Economy, Vol. 30 No. 1, 2016

54

Chuck Marr, “JCT Highlights Pass-Through Deduction’s Tilt Toward the Top,” Center on Budget and Policy

Priorities, April 24, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/jct-highlights-pass-through-deductions-tilt-toward-the-top.

17

The deduction gives wealthy business owners a new incentive to recharacterize their labor

compensation as pass-through profits. Such incentives exist even apart from the deduction; for

example, many S corporation shareholders — who receive both wage or salary income from the

company and a share of the company’s profits but pay Medicare taxes only on the wage or salary

portion — underreport the share of their income that comes from wages and salaries and overstate

the share that is pass-through business income in order to reduce their Medicare taxes. A 2009

Government Accountability Office report found that 13 percent of S corporations underpaid wage

compensation in 2003 and 2004, resulting in $23.6 billion in underreported wages and salaries —

and roughly $3 billion in lost Medicare tax revenues during those years.

55

On top of the ability to minimize Medicare taxes, pass-through owners now benefit from the 2017

tax law’s pass-through deduction, which gives qualifying filers a 7.4 percentage point tax rate

reduction on certain pass-through income. As a result, the top income-tax rate is 37 percent for

wages and salaries but just 29.6 percent for pass-through income that qualifies for the deduction.

56

This further encourages pass-through owners to recharacterize their labor compensation as pass-

through profits, which can allow them to avoid the top rate on even more of their labor income.

Corporate Tax Rate

The centerpiece of the 2017 tax law was a cut in the corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 21

percent. Corporate rate cuts largely benefit wealthy corporate shareholders; one-third of the benefits

ultimately flow to the top 1 percent of households, according to TPC.

57

Before the 2017 tax law, there was bipartisan support for reducing the corporate rate while

expanding the corporate tax base to keep the changes revenue neutral. President Obama, for

example, proposed lowering the rate to 28 percent and broadening the base to fully offset the cost.

58

The 2017 tax law, however, cut the rate by twice as much as the Obama proposal and lacked

significant base-broadeners. As a result, the corporate provisions will cost $668 billion over the first

ten years, JCT estimated.

59

Corporate tax payments, which neared $300 billion in 2017 (before the

law took effect), plummeted to $205 billion the following year, well below CBO’s prediction of $243

billion.

60

55

Government Accountability Office, “Tax Gap: Actions Needed to Address Noncompliance with S Corporation Tax

Rules,” December 2009, https://www.gao.gov/new.items/d10195.pdf.

56

Some pass-through income of high-earning taxpayers is subject to the 3.8 percent NIIT, but a large share is exempt

from both the NIIT and Medicare taxes.

57

TPC Table T17-0180; Chye-Ching Huang and Brandon DeBot, “Corporate Tax Cuts Skew to Shareholders and

CEOs, Not Workers as Administration Claims,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, updated August 16, 2017,

https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/corporate-tax-cuts-skew-to-shareholders-and-ceos-not-workers-as-

administration.

58

White House and Treasury Department, “The President’s Framework for Business Tax Reform: An Update,” April

2016, https://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/tax-policy/documents/the-presidents-framework-for-business-tax-

reform-an-update-04-04-2016.pdf.

59

Joint Committee on Taxation, JCX-67-17, https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=5053. This

figure excludes the one-time revenue from the law’s provision allowing corporations to repatriate pre-existing foreign

earnings at a low rate.

60

Congressional Budget Office, “Budget and Economic Outlook: 2018 to 2028,” April 2018,

https://www.cbo.gov/publication/53651; Jane G. Gravelle and Donald J. Marples, “The Economic Effects of the 2017

18

Not only did the 2017 law’s corporate rate cut disproportionately benefit wealthy shareholders,

but the wide gap it created between the 37-percent top individual tax rate and the 21-percent

corporate rate gives wealthy individuals an incentive to shelter their income in corporations.

61

For

example, a wealthy bond investor owning several million dollars of bonds can transfer them to a

new corporation that she has created solely to hold these assets — and potentially pay tax on the

interest income at roughly half the rate she would pay if this income faced the individual income tax

rate.

62

She might eventually have to pay taxes on dividends or capital gains on the wealth that accrues

in the corporation, but she could defer that second layer of tax for decades and even avoid it

altogether by passing the corporation on to her heirs. Before the 2017 law took effect, the corporate

and top individual rates were close enough to each other that this type of sheltering didn’t make

sense for most wealthy taxpayers.

Several Options Exist to Tax High Incomes, Large Fortunes More Effectively

The tax code’s approach to taxing the income of wealthy people and the transfer of large fortunes

is deeply flawed. Much of the income of wealthy people doesn’t show up on their tax returns, and

much of what does show up enjoys special breaks.

There are a number of sound proposals to tax high incomes and large fortunes more effectively,

which could mitigate income inequality while also raising new revenue that could help address

various national policy priorities. Some proposals expand the types of income considered taxable;

others improve taxation of income already taxed under the current system. The options below do

not constitute a single agenda; some are complementary (such as eliminating both stepped-up basis

and preferred rates on capital gains), while others are alternatives (such as strengthening the estate

tax or creating an inheritance tax). Nor is the set of options below intended to provide an exhaustive

list of possible ways to raise substantial revenue in a progressive manner. For example, another such

option, not covered in this paper, would be to impose a very small percentage tax — often referred

to as a financial transactions tax (FTT) — on the sale of securities such as stocks and bonds.

63

Tax Revision: Preliminary Observations,” Congressional Research Service, June 7, 2019,

https://www.everycrsreport.com/files/20190607_R45736_7633cfe1a9ceda0931cd8ccfeca6eb5455e2ee1d.pdf.

61

Marr, Huang, and Duke, op. cit.

62

The IRS could use one of several “anti-abuse” rules to combat this type of transaction, but these rules are “notoriously

ineffective.” Michael Schler, “Reflections on the Pending Tax Cuts and Jobs Act,” Tax Notes, January 2, 2018,

https://www.taxnotes.com/tax-notes-today-federal/corporate-taxation/reflections-pending-tax-cuts-and-jobs-

act/2018/01/02/1xdwp#1xdwp-0000044. In any case, anti-abuse rules rely on a strong IRS that can enforce these rules,

but the IRS enforcement budget has significantly declined in recent years, undermining its ability to combat tax

sheltering activity. See Roderick Taylor, “House Bill Leaves IRS Enforcement Depleted,” Center on Budget and Policy

Priorities, May 24, 2018, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/house-bill-leaves-irs-enforcement-depleted.

63

Leonard E. Burman et al., “Financial Transaction Taxes in Theory and Practice,” National Tax Journal, Vol. 69, No. 1,

March 2016, https://ntanet.org/NTJ/69/1/ntj-v69n01p171-216-financial-transaction-taxes-theory-

practice.pdf?v=%CE%B1.

19

Expanding the Types of Income Considered Taxable

Adopting Mark-to-Market Taxation of Capital Gains

Instead of waiting to tax capital gains until assets are sold, the tax code could institute a mark-to-

market system that applies to households with considerable wealth and levies tax annually on the

gain in value of those households’ assets whether or not the assets have been sold.

64

For example, if

a wealthy investor bought publicly traded stock on January 1 for $1,000 a share and the stock’s

trading price was $1,100 on December 31, she would pay capital gains tax on the $100 increase per

share even if she didn’t sell the stock that year. As discussed more below, policymakers could design

a mark-to-market tax to ensure that it applies only to wealthy households.

Since wealthy taxpayers would no longer have a tax incentive to defer asset sales, they would sell

assets when it made economic sense to do so. And eliminating this tax incentive would significantly

increase capital gains tax collections.

A related reform that would also raise capital gains revenue collections would be to raise the

capital gains tax rate. Under current law, the rate that would raise the most revenue is approximately

30 percent, according to JCT. At rates above 30 percent, JCT believes that revenue would begin

falling because taxpayers would substantially increase tax avoidance, such as by delaying asset sales.

65

Under a strong mark-to-market system that largely eliminates such incentives, however, wealthy

taxpayers could no longer avoid capital gains taxes by deferring asset sales. Thus, policymakers could

generate further significant revenue, primarily from the very top of the income distribution, by

raising capital gains rates to match the prevailing rates on ordinary income.

One challenge of a mark-to-market tax on capital gains is the need to value assets and impose tax

each year. For certain types of assets, like a work of art or an ownership interest in a closely held

company, annual valuations could impose administrative burdens on taxpayers and lead to tax

avoidance, as taxpayers shop around for the lowest appraisal. To address this problem, the tax code

could treat non-publicly-traded assets differently: instead of imposing an annual capital gains tax on

unrealized gains in those assets, it could continue to defer taxes on them until realization, but

impose a one-time “deferral charge” when the asset is eventually sold, comprising the amount of

capital gains tax plus an amount similar to interest that would be based on how long the asset was

held before it was sold. This would still reduce the incentive to defer sales of capital assets compared

to the current tax code. It would also make other complementary reforms we discuss here, such as

raising capital gains rates and closing other loopholes that allow some capital gains to go untaxed,

more effective and efficient.

Policymakers have several design alternatives to ensure that a mark-to-market system applies only

to wealthy investors. They could, for instance, exempt all capital gains for taxpayers who are below a

specified income or wealth threshold (these taxpayers would only owe capital gains tax when the

gains are realized), or grant all taxpayers a lifetime exemption of a specified dollar amount of capital

gains, above which they would have to use the mark-to-market system.

64

Taxpayers would also deduct any losses in the year in which they occur.

65

Lily Batchelder and David Kamin, “Taxing the Rich: Issues and Options,” Aspen Institute, September 11, 2019,

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3452274.

20

Senate Finance Committee Ranking Member Ron Wyden recently released a white paper calling

for a mark-to-market tax system for capital gains along with an increase in the capital gains rate to

the same rates as apply to ordinary income.

66

Under Senator Wyden’s proposal, large capital gains on

corporate stock and other securities that wealthy households own would be taxed annually, while

non-publicly traded assets would be subject to a deferral charge at the time of sale. Wyden estimates

that his proposal could raise $1.5 trillion to $2 trillion over ten years.

67

Addressing Other Provisions Encouraging Capital Gains Tax Avoidance

President Obama proposed limiting the amount of capital gain that a taxpayer can defer through

“like-kind exchanges” to $1 million per year and disallowing the like-kind exchange loophole for

sales of artwork or other collectibles.

68

This would have raised more than $47 billion over 2017-

2026. In contrast, the 2017 tax law’s reform of the like-kind provision, which retained the loophole

for real estate, is expected to raise $31 billion over 2018-2027.

69

The like-kind exchange tax break

remains costly and unwarranted, costing roughly $9 billion a year in lost revenue.

70

The best course

of action here would be simply to eliminate this tax break.

Furthermore, because the opportunity zone and qualified small business stock tax breaks directly

benefit wealthy investors and may fall well short of producing socially beneficial investment on a

substantial scale, policymakers should reconsider and, at a minimum, substantially reform and

tighten them — and devote the freed-up resources to investments more directly benefiting low- and

moderate-income people and communities.

Ending Stepped-Up Basis

Policymakers should repeal stepped-up basis by taxing the unrealized capital gains of affluent

households when appreciated assets are transferred to heirs. Since future tax liability on unrealized

capital gains would no longer be eliminated at death, affluent owners of valuable assets would have

less incentive to defer tax by waiting to sell them; instead, they would be more likely to sell the assets

when it made economic sense to do so. (As noted, this change also would allow policymakers to

raise substantial revenue by raising capital gains tax rates, since investors could not avoid those taxes

by holding more assets until death.)

66

Senate Finance Committee, “Treat Wealth Like Wages,”

https://www.finance.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Treat%20Wealth%20Like%20Wages%20RM%20Wyden.pdf.

67

Ibid. Other proposals to implement a mark-to-market system are consistent with Senator Wyden’s revenue estimate.

See Batchelder and Kamin, op. cit.; David Kamin, “Taxing Capital: Paths to a Fairer and Broader U.S. Tax System,”

Washington Center for Equitable Growth, August 2016, https://equitablegrowth.org/wp-

content/uploads/2016/08/081016-kamin-taxing-capital.pdf.

68

Chuck Marr, “The Tax Loophole of 2016: Like-Kind Exchange,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, May 18,

2016, https://www.cbpp.org/blog/the-tax-loophole-of-2016-like-kind-exchange.

69

Joint Committee on Taxation, JCX-67-17, https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=5053.

70

Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimates of Federal Tax Expenditures for Fiscal Years 2018-2022,” JCX-81-18,

October 4, 2018, https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=5148.

21

Such a measure can be designed to shield most or all middle-class households. President Obama

proposed repealing stepped-up basis for most capital gains over $350,000 (including $250,000 for

personal residences and $100,000 of other gains). Such thresholds could be set where policymakers

want to place them. President Obama’s proposal also would have retained rules allowing taxpayers

to donate property to charitable organizations tax-free while allowing a deduction equal to the

property’s fair market value, thereby exempting from federal income tax the appreciation that

occurred while the taxpayer held the assets. JCT estimated that the Obama proposal, along with an

increase in the maximum rate on capital gains and dividends to 28 percent, would have raised $250

billion over ten years.

71

Adopting a mark-to-market system would partially address the problem of stepped-up basis by

eliminating (for wealthy investors) capital gains deferral until death, at least for publicly traded assets

whose gains would be taxed annually. For other asset classes, however, repeal of stepped-up basis

would be beneficial even if a deferral charge is imposed. Stepped-up basis should also be repealed

for gains accrued by wealthy investors before imposition of a mark-to-market system if those gains

aren’t taxed upon transition to the new system.

Imposing a Wealth Tax on Very Wealthy Households

Annually taxing wealth — whether via a wealth tax or changes to the income tax that have a

similar effect — would fundamentally change the way the federal tax code treats wealthy taxpayers

and raise substantial revenue while reducing inequality.

A wealth tax would apply to a wealthy taxpayer’s overall stock of capital without regard to her

actual gains or losses from that wealth. This would be analogous to the annual state and local

property tax that millions of homeowners across the country pay each year on the value of their

homes.

72

For instance, Senator Elizabeth Warren has proposed a 2 percent tax on the wealth of

households with more than $50 million in net assets and a 3 percent tax on households worth more

than $1 billion. Economists Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman estimate that the proposal would

affect fewer than 0.1 percent of households and would raise around $2.75 trillion over ten years,

73

although their cost estimate has been questioned and may be too high.

74

The Institute on Taxation

71

Joint Committee on Taxation, “Description of Certain Revenue Provisions Contained in the President’s Fiscal Year

2017 Budget Proposal,” JCS-2-16, July 21, 2016, https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=4936;

Kamin, op. cit.

72

Moreover, homeowners pay tax on the full assessed value of the property, even the share subject to debt (i.e., a

mortgage), whereas wealth tax proposals apply only on assets net of any debt.

73

Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman, January 18, 2019, http://gabriel-zucman.eu/files/saez-zucman-wealthtax-

warren.pdf.

74

Extrapolating based on estate tax data, former Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers and Professor Natasha Sarin

estimate that Senator Warren’s proposal would raise only 20-40 percent of what Saez and Zucman expect. Lawrence H.

Summers and Natasha Sarin, “A ‘Wealth Tax’ Presents a Revenue Estimation Puzzle,” Washington Post, April 4, 2019,

https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2019/04/04/wealth-tax-presents-revenue-estimation-puzzle/. Other

research questions the methodology Saez and Zucman use to estimate the amount and composition of wealth. See

Matthew Smith, Owen Zidar, and Eric Zwick, “Top Wealth in the United States: New Estimates and Implications for

Taxing the Rich,” July 19, 2019,https://scholar.princeton.edu/sites/default/files/zidar/files/szz_wealth_19_07_19.pdf.

Professors Lily Batchelder and David Kamin, however, estimate that even with a 30 percent tax avoidance rate (double

22

and Economic Policy estimates that a lower wealth tax rate of 1 percent on households with more

than about $32.2 million (that is, the top 0.1 percent of households in 2020) could raise $1.3 trillion

over ten years.

75

An alternative would be an “imputed income tax,” which would assume that a taxpayer’s stock of

wealth generates a specified, standard rate of return as a proxy for income and require taxpayers to

claim those assumed returns as part of their income on their annual tax returns. This is designed to

address gaps in the current system under which much of the income of wealthy people does not

show up on their tax returns.

The Netherlands, for example, imposes a tax that is formally part of its income tax but operates

similarly to a wealth tax by taxing an assumed return on a taxpayer’s publicly traded stock and some

other forms of wealth. Likewise, Professor Ari Glogower has proposed adjusting key parameters of

the existing federal income tax — such as deductions, credits, or tax rates — to account for

significant wealth holdings.

76

In both cases, taxpayers with great wealth would increase the income tax

they pay as a result of that wealth, much like their rates and tax benefits are currently adjusted for

characteristics such as marital status, age, and investment income.

As with any tax policy proposal, these options have advantages and disadvantages. As noted,

performing valuations annually of certain hard-to-value assets like artwork could create

administrative challenges. Senator Warren’s plan would both dramatically increase the IRS budget,

enabling it to devote more staff to audits, and make the valuation process somewhat less complex

and prone to avoidance.

Structuring a wealth tax as a part of the existing income tax could mitigate concerns about the

constitutionality of a wealth tax. The Constitution requires so-called “direct taxes” to be

“apportioned” among the states in proportion to their populations, meaning that a tax needs to raise

revenue from each state in proportion to that state’s share of the U.S. population.

77

As a result of

this constitutional requirement, the Supreme Court held in 1895 that a federal income tax was

unconstitutional;

78

it took enactment and ratification of the 16

th

Amendment to the Constitution in

1913 to enable a federal income tax to be instituted. Legal scholars debate which taxes are “direct

taxes” under the Constitution and whether a wealth tax like the Warren proposal would in fact be an

the avoidance rate that Saez and Zucman anticipate), a wealth tax similar to Senator Warren’s proposal would likely raise

approximately $2 trillion over ten years. Batchelder and Kamin, op. cit.

75

Steve Wamhoff, “Thoughts about a Federal Wealth Tax and How It Could Raise Revenue, Address Income

Inequality,” Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, January 23, 2019, https://itep.org/thoughts-about-a-federal-

wealth-tax-and-how-it-could-raise-revenue-address-income-inequality/ .

76

Ari Glogower, “A Constitutional Wealth Tax,” Michigan Law Review, forthcoming,

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3322046.

77

U.S. Constitution, Article I, § 2, cl. 3; § 9, cl. 4. This clause was part of the framers’ so-called “compromise” over

slavery, which included the infamous requirement (since superseded) that each slave count as three-fifths of a free

person for apportioning those direct taxes and determining the state’s number of House seats. A number of historians,

constitutional scholars, and judges have argued that the requirement for direct taxes to be apportioned was intended to

protect southern states from the federal government levying taxes on the ownership of slaves, including by making it

harder to levy such taxes at rates sufficiently high as to effectively tax slavery out of existence.

78

Pollock v. Farmers Loan Trust Co., 157 U.S. 429 (1895).

23

unconstitutional direct tax,

79

but many have expressed concern that the current Supreme Court

could rule that a wealth tax violates the Constitution. Though there are strong legal arguments for

the constitutionality of a wealth tax, policymakers might be able to avoid the debate by structuring

the tax through the existing income tax.

Taxes on wealth — whether structured as a wealth tax or an imputed income tax, or whether

pursued through the capital gains, dividends, and estate tax reforms discussed here, which are other

ways of taxing wealth — would help counter the decades-long increase in wealth inequality and

provide a significant source of new progressive revenue at a time when our nation sorely needs it.

Strengthening the Estate Tax

Policymakers also should bolster the estate tax to ensure that wealthy heirs pay their fair share in

tax. For example, they could restore the tax to the parameters that were in place in 2009 — that is, a

$3.5 million exemption (effectively $7 million for a couple) and a 45 percent top estate tax rate.

Doing so could raise about $160 billion over ten years.

80

Policymakers could also enact rules to prevent abuses associated with GRATs and excessive

valuation discounts, such as through use of the minority ownership discount. Obama

Administration proposals to address these abuses would have raised $14 billion over ten years if the

2009 estate tax parameters were also restored.

81

Going beyond the Obama proposals to close these

loopholes entirely could raise still more.

Enacting an Inheritance Tax

An alternative to strengthening the estate tax would be to replace it with an inheritance tax, which

is levied on the income that heirs receive rather than on the value of the estate itself. This reform

would complement repeal of stepped-up basis at death: repealing stepped-up basis would tax

unrealized gains that accrued tax-free during the deceased person’s lifetime, and the heirs — who are

considered separate legal persons from their parents — would then pay inheritance tax on very large

windfalls.

The tax code defines taxable income broadly to include items such as lottery and gambling

winnings, forgiven debt, and fringe benefits from employers like paid moving expenses. In each

79

Glogower, op. cit.; Dawn Johnsen and Walter Dellinger, “The Constitutionality of a National Wealth Tax,” Indiana Law

Journal, Vol. 93, No. 1, Winter 2018, https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj/vol93/iss1/8/.

80

Joint Committee on Taxation, “Description of Certain Revenue Provisions Contained in the President’s Fiscal Year

2017 Budget Proposal,” JCS-2-16, July 21, 2016, https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=4936.

Adopting Senator Bernie Sanders’ 2016 proposal, which would restore the 2009 parameters and establish a higher rate

structure for estates exceeding $10 million, would raise $500 billion. Frank Sammartino et al., “An Analysis of Senator

Bernie Sanders’s Tax Proposals,” Tax Policy Center, March 4,

2016, http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/publications/analysis-senator-bernie-sanderss-tax-proposals. The Sanders

proposal would raise the estate tax rate to 50 percent for estate values between $10 million and $50 million (between $20

million and $100 million per couple), to 55 percent for estate values between $50 million and $500 million, and to 65

percent for estate values over $500 million ($1 billion per couple).

81

Joint Committee on Taxation, JCS-2-16, op. cit.

24

case, tax is imposed on an economic gain. Taxing heirs on their economic gains (their inheritances)

would subject them to the same standards that apply to everyone else.

Moreover, inheritance taxes encourage work, unlike taxes on labor. Inheritances can make people

much richer, which may encourage them to work less. Treasury Department economist David

Joulfaian found that “an inheritance of $1 million, other things equal, reduces labor force

participation by about 11 percent.”

82

By reducing the windfall, an inheritance tax encourages heirs to