1

PER

CAPIT

SUBMISSION TO SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES ON

ENVIRONMENT AND COMMUNICATIONS’ INQUIRY INTO THE

NATIONAL CULTURAL POLICY

Per Capita

March 2023

‘I regard the theatre as the greatest of all art-forms, the most immediate way in which a human being can

share with another the sense of what it is to be a human being.’

1

- Thornton Wilder, 1957

Per Capita welcomes the opportunity to provide this submission to the Senate Standing Committees on

Environment and Communications, for their inquiry into the National Cultural Policy (the Policy).

Per Capita is an independent public policy think tank, focused on building a new vision for Australia. One that

promotes shared prosperity, social justice, and fairness.

Access to, and participation in cultural events is a social justice issue, for creative industry workers, and for

the public. Australians living outside of capital cities, with lower levels of education, and lower household

incomes attend cultural activities at a lower rate than their counterparts. Socioeconomic factors inhibit access

to the arts, and thus, to the coinciding benefits the arts can provide to health, social cohesion, and community

building.

2

This is recognised in one of the Policy’s ten guiding principles: that ‘[a]ll Australians, regardless of

language, literacy, geography, age, or education, have the opportunity to access and participate in arts and

culture’.

3

Per Capita has considered the Policy and is broadly supportive of its aims. The Policy clearly acknowledges

the importance of the arts in Australia, and the essential role it plays in our sense of belonging and identity.

The Policy seeks to restore funding to industries, horribly neglected by former governments, and pave the way

for a much-needed restoration of our creative ecosystem.

However, Per Capita submits that within the actions enumerated in the Policy, a stronger focus on audience

access to live performance should be considered, to promote further access for all Australian to participate in

arts and culture, regardless of socioeconomic status.

This submission will focus primarily on live theatre in Australia’s desperately under-subsidised, publicly

subsidised theatres, with emphasis on the fifth of the Policy’s interconnected pillars: Engaging the Audience –

making sure our stories connect with people at home and abroad.

4

Why live theatre?

Theatre is unique to other artforms, incorporating multiple disciplines into one. It is deeply intimate and

unique in its nowness. As the fourth wall crashes down, audience and players are locked in a shared

experience; where no two performances are ever the same.

Writing for the International Federation of Actors (FIA), Michael Crosby, Australian trade unionist and

former general secretary of FIA, considered the important role of Actors as the storytellers of our society:

1

Richard Goldstone, ‘The Art of Fiction XVI: Interview with Thornton Wilder’ [1957] (15) The Paris Review 36, 47

2

Australian Bureau of Statistics, Attendance at Selected Cultural Venues and Events, Australia (Catalogue No 4114.0, 26 March 2019) Table 2,6-7.

3

Commonwealth of Australia, Revive a place for every story, a story for every place – Australia’s cultural policy for the next five years (Policy

Document, January 2023) 19.

4

Ibid 18.

•

per

cap1ta

FIGHTING

INEQUAL

I

TY

IN

AUSTRALIA

National Cultural Policy

Submission 13

2

PER

CAPIT

they are essential to the intellectual and emotional health of a society. They are the face and voice of

a nation’s culture. They tell a nation their own stories. They reflect what it is to be a citizen of that

nation. They hold a mirror to society so that it can see its true nature. They embody the intellectual

and emotional struggles going on in each of our societies.

5

But who is being reflected in this mirror? And who can view this reflection?

The economic and non-economic benefits of the Australian creative industries were well investigated by the

2021 House of Representatives Standing Committee on Communication and the Arts inquiry into Australia's

Creative and Cultural Industries and Institutions.

6

However, without access to the stages where our stories are

told, many Australians miss out on these benefits.

Who is being reflected?

Diversity is front and centre in this report, and whilst language, literacy, geography, age, or education all

contribute to socioeconomic disadvantage in our community, more emphasis should be placed on

investigating and correcting barriers to access so that everyone can experience the social benefits (individual

and societal) of viewing live theatre.

Benefits of theatre

The economic and non-economic benefits of the Australian creative industries were well investigated by the

2021 House of Representatives Standing Committee on Communication and the Arts inquiry into Australia's

Creative and Cultural Industries and Institutions.

7

However, without access to the stages where our stories are

told, many Australians miss out on these benefits.

Research published in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, in 2021, found that attending theatre

improves empathy, changes attitudes, and leads to pro-social behaviour.

8

In the first part of this study,

researchers examined the effects on audiences of the play Skeleton Crew, by Dominque Morisseau, a play

about the impacts on Detroit’s auto workers following the 2008 financial crisis. It was a production which ‘put

onstage people of a race and class and type that much mainstream theatre might ignore or demonise’.

9

Results

from the study showed that surveyed audience members reported:

feeling more empathy towards factory workers in Detroit… [s]pecifically, they reported feeling more

empathic concern for factory workers… were more likely to think that racial discrimination is a major

issue; that the government should reduce income disparities; and were more supportive of corporate

regulation.

10

What we put on our stages is important. It plays a crucial role in how we understand our wider community.

The Australian stage

Australia’s first international export of live spoken word theatre was Ray Lawler’s 1955 play Summer of the

Seventeenth Doll. This production dealt heavily with class, gender, race, and the Australian national identity.

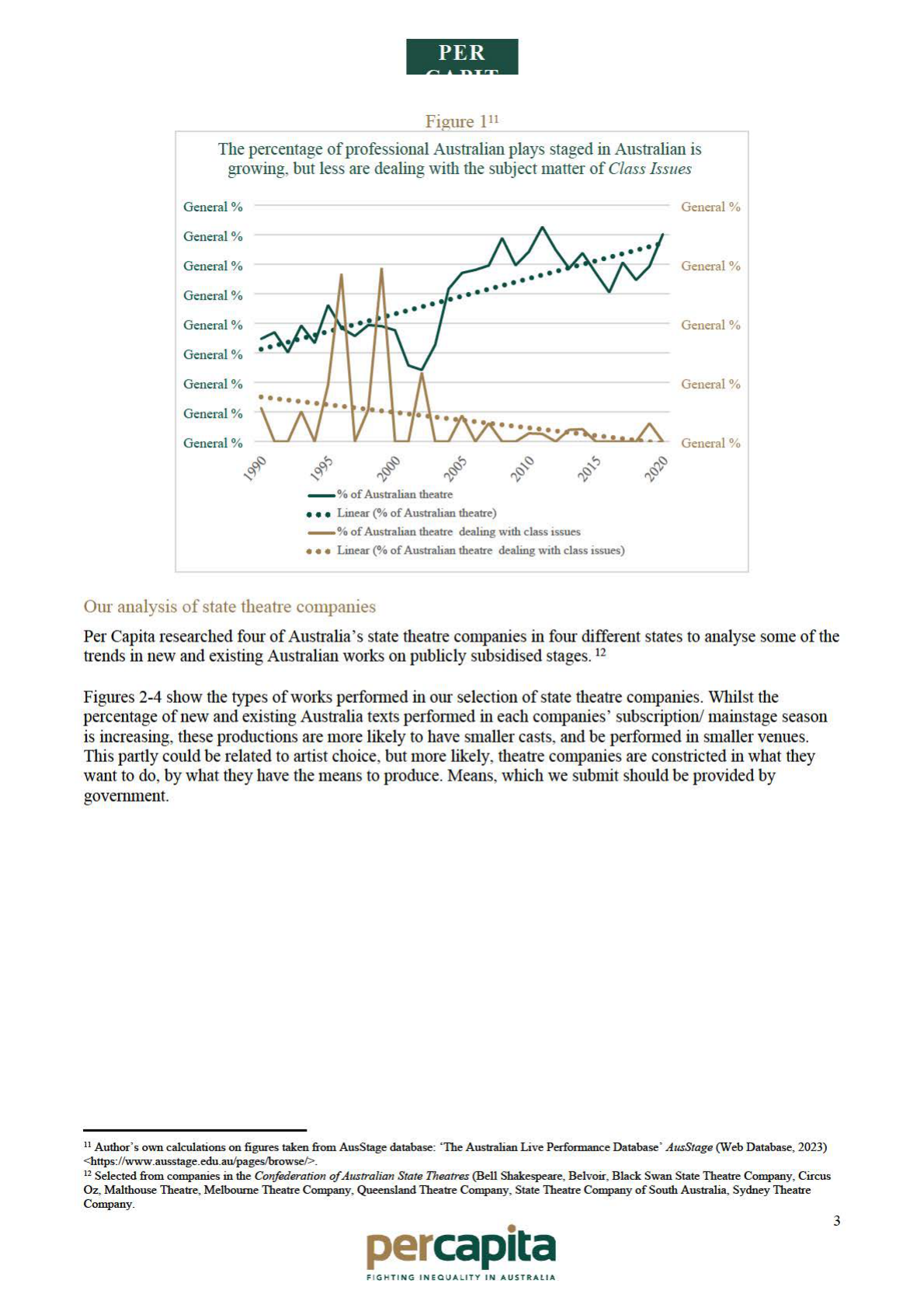

However, political theatre that deals with class issues is minimal in Australia. Even with reduced funding to

the sector, the number of new and existing Australian spoken theatre texts performed professionally on

Australian stages has increased, but the number of those productions which deals with class issues has

decreased. This is presented in Figure 1.

5

Michael Crosby, ‘Reflections on the Challenge of Organising Actors’(FIA Document, International Federation of Actors, August 2020) 3 <https://fia-

actors.com/fileadmin/user_upload/News/Documents/2021/January/FIA_Organising_Actors.pdf>.

6

House of Representatives Standing Committee on Communications and the Arts, Parliament of Australia, Sculpting a National Cultural Plan -

Igniting a Post-COVID Economy for the Arts (Report, October 2021).

7

House of Representatives Standing Committee on Communications and the Arts, Parliament of Australia, Sculpting a National Cultural Plan -

Igniting a Post-COVID Economy for the Arts (Report, October 2021).

8

Steve Rathje, Leor Hackel and Jamil Zaki, ‘Attending Live Theatre Improves Empathy, Changes Attitudes, and Leads to Pro-social Behaviour’ (2021)

95 (January) Journal of Experimental Social Psychology.

9

Ibid 2.

10

Ibid 3.

•

per

cap1ta

FIGHTING

INEQUAL

I

TY

IN

AUSTRALIA

National Cultural Policy

Submission 13

Figure 1

11

The

percentage

of

professional Australian plays staged in Australian

is

growing, but

less

are dealing with

the

subject matter of Class Issues

General %

General %

General %

General %

General %

General %

General %

General %

General %

- %

of

Australian theatre

• • •

Linear(%

of

Australian theatre)

- %

of

Australian theatre dealing with class issues

• • • Linear (%

of

Australian theatre dealing with class issues)

Our analysis of state theatre companies

General%

General%

General%

General%

General%

Pe

r

Ca

pita

re

searc

hed

four

of

Australia's state theat

re

compan

i

es

in four different states

to

analyse

some

of

the

trends in

ne

w

and

existi

ng

Australian

works

on publicly

subs

idised

stages.

12

Fig

ure

s

2-4

s

how

the

types

of

works

perfo1med in

our

se

lection of state theatre companies. Whilst the

percentage of

ne

w and

ex

i

st

ing Australia texts

perfo1med

in each companies'

su

b

sc

1ip

tion/ mainstage season

is

incre

as

ing, t

he

se

productions are

mo

re likely

to

h

ave

smaller casts, and

be

perfo1med in

sma

ller

ve

nue

s.

This

pa1t

ly could

be

related

to

rutist choice, but

more

likely, theatre companies

ru·e

constricted in what they

want

to

do

, by what they h

ave

the

means

to

produce.

Mea

ns, which

we

su

bmi

t sh

ou

ld

be

provi

ded

by

government.

11

Author's

own

calculations

on

figures taken from

Au

sStage database:

'The

Australian Live Performance Database' AusStage (Web Database,

20

23)

<htt.ps://

www

.ausstage.eclu.au/pages/browse

/>

.

12

Selected from companies

in

the Confederation

of

Australian State Theatres (Bell Shakespeare, Belvoir, Black

Swan

State Theatre Company, Circus

Oz

, Malthouse Theatre, Melbourne Theatre Company, Queensland Theatre Company, State Theatre Company

of

South Australia, Sydney Theatre

Company.

•

per

cap1ta

FI

GHT

I

NG

IN

EQUALITY

IN

AUSTRALIA

3

National Cultural Policy

Submission 13

Fip;me

2

13

The percentage

of

new and existing Australian works is increasing

on

om

publically

susidised stages

General

GJi'mi

GJi'mi

GJi'mi

GJi'mi

GJi'mi

GJi'mi

GJi'mi

GJi'mi

%

9

8

7

6

5

4

3

2

I

0

~◊

~◊

~

'\,v '\,v

~

<;),'>

<;i'""

<;i'"

<;)~

"\) "\) "\) "\)

- %

of

non

-Australian works - %

of

all

Australian works

- %

of

new Australian works

Fip;me

3

14

The average cast size for new Australian works is typically smaller than non-

Australian works

I II I I I I

~'

~

<;)◊

"\)

0

~

~

"\,<:,

~"'

~

~""

"\,<:,

~

~

~'l,

<;)~

~

"\)

■ Average

cast

size

in

non

-Australian works

■

Average cast size

in

Australian works

Fip;me

4

15

More new Australian works are performed

in

each

company's smallest main venue for productions

in

their

subscription/mainstage season

Less new Australian works are performed

in

each

company's largest

main

venue for productions

in

their

subscription/mainstage season

General %

General %

General %

General %

General %

General %

General %

General %

General %

General %

General %

I ■

I.

Company A Company B Company C Company D

■

%

of

new Australian works 2011-2019

■

%

of

non-Australian works 2011-2019

General%

General%

General%

General%

General%

General%

General%

General%

General%

General%

I I

Company A Company B Company C Company D

■

%

of

new Australian works 2011-2019

■

%

of

non-Australian works 2011-2019

13

Author's

own

calculations

on

figures taken from annual reports from 2010-2021

of

Me

lbourne Theatre Company (Vic), Black

Swan

State Theatre

Company

(YI

A)

, Queensland Theatre Company (Qld),

and

State Theatre Company

of

South Australia (SA) and AusStage database:

The

Australian

Li

ve

Performance Database' AusStage (Y,eb Database, 2023)

<h

t

t.ps:

//

www

.ausstage.edu.au/pages/brows

e/>

.

14

Ib

id.

l S

Ib

id.

•

per

cap1ta

FI G

HT

I NG

IN

EQUALI

TY

IN

AUSTRALIA

4

National Cultural Policy

Submission 13

5

PER

CAPIT

Who gets to view the reflection?

As early as 1856, Australian workers were rallying for the right to recreation. At the first Eight-hour day

procession in Melbourne, workers led the procession carrying a banner which read Eight hours labour, eight

hours recreation, eight hours rest.

16

Since its inception, the Australian labour movement has understood that to advance the interests of the

working class, unions needed to be involved in all activities that encompassed the of lives members and their

families, not merely their mainstay struggle for better wages and conditions.

17

In 1977, in its first resolution on the subject, the Congress of the Australian Council of Trade Unions declared

‘that there is an urgent need for the trade unions to become more involved in the arts and cultural life of the

Australian people’.

18

Why? Because as their 1991 Cultural Policy elucidates:

Successful democracies need four common qualities: productive and inventive economies; highly

skilled and well-educated work forces; highly developed social security systems and high levels of

cultural involvement. Cultural involvement is a critical and supportive element to the other three

qualities.

19

Bovell, Cornelius, Reeves, Tsiolkas and Vela’s Who’s Afraid of the Working Class, is play that puts the

struggles of the working-class front and centre. This production forced the audience to consider pressing

issues of everyday Australians, powerless in the face of growing inequality. As Melbourne theatre reviewer,

Kate Herbert wrote at the time: it was a story about the ‘disenfranchised underclass created by insensitive

government policies and a shrinking job market’.

20

In the introduction of the 2017 reprint of the play, director Julian Meyrick muses on the development, and

importance, of this Melbourne Workers theatre production, first performed at Victorian Trades Hall on 1 May

1998:

The choice of the aesthetic entailed considerable risk. It meant breaking with the upbeat,

celebrational mood of so much Australian community theatre, a style with which the commissioning

company, the Melbourne Workers Theatre, was partially identified. There was always the fear of

being negative, regressive even, painting things as worse than they were. But how could they be any

worse than what we saw, daily, around us? As rehearsals for the first season got underway it was

easy to research the characters in the play. All you had to do was walk down the street.

21

The first mount of Who’s Afraid received highly enthusiastic reviews and attracted large audiences.

22

With

tickets at $8-$15

23

the cost to attend made up just 1.5% of the average weekly wage at the time.

24

Jumping

forward to 2020, the average ticket price for all theatre in Australia is $105.14,

25

almost 6% of the 2020

weekly average wage.

26

Live Performance Australia’s trends analysis shows a 82% growth in average ticket

16

Peter Love 'Report: Melbourne Celebrates the 150

th

Anniversary of its Eight Hour Day' (2006) 91 (November) Labour History 193, 193.

17

Sandy Kirby, Artists and Unions A Critical Tradition A Report on the Art & Working Life Program (Australia Council, 1992) 8. Redfern, 1992

page 8

18

Richard Walsham, ‘Have a Cultural Bent’ (1978) 59(4) Journal of the New South Wales Public Schools Teachers Federation 75, 75.

19

Australian Council of Trade Unions, ‘Cultural Policy’ (Congress Policy Document, September 1991) (emphasis added)

<https://www.actu.org.au/media/349680/actucongress1991_cultural_policy.pdf>.

20

Kate Herbert, ‘Who’s Afraid of the Working Class?’ Kate Herbert Theatre Reviews (Blog, 1 May 1998)

<https://kateherberttheatrereviews.blogspot.com/1998/05/whos-afraid-of-working-class-may-1-1998.html>.

21

Andrew Bovell et al, Who’s Afraid of the Working Class?, ed Julian Meyrick (Currency Press, 2

nd

ed, 2017) vi.

22

Glenn D'Cruz, ‘Class’ and Political Theatre: The Case of Melbourne Workers Theatre’ (2005) 21(3) New Theatre Quarterly 207, 209.

23

Bronwen Beechey, ‘When the class is no longer working’ (1998) May (317) Green Left (Online) <https://www.greenleft.org.au/content/when-class-

no-longer-working>.

24

Australian Bureau of Statistics, Average Weekly Earning, Australia (Catalogue No 6302.0, 13 August 1998).

25

Live Performance Australia, Live Performance Industry in Australia: 2019 and 2020 Ticket Attendance and Revenue Report (Report, 7 October

2021) 91.

26

Australian Bureau of Statistics, Average Weekly Earning, Australia (Catalogue No 6302.0, 13 August 2020).

•

per

cap1ta

FIGHTING

INEQUAL

I

TY

IN

AUSTRALIA

National Cultural Policy

Submission 13

6

PER

CAPIT

prices, from an average of $43.87 in 2004 to $105.14 in 2020.

27

In our analysis of state theatre companies, we

found ticket prices had increased for concession and full fare from 19-24% from just 2015 to 2023.

28

Who’s afraid of the working class today? No-one. They can’t get through the door.

Barriers to access

According to statistics from the ABS, the attendance rate for theatre performances is lower for people with

lower household incomes, lower educational attainment, and for people living outside of capital cities. Whilst

attendance rate has reduced across the board, it has reduced considerably more for those in lower

socioeconomic categories. This is show in Table 1.

27

Live Performance Australia, Live Performance Industry in Australia: 2019 and 2020 Ticket Attendance and Revenue Report (Report, 7 October

2021) 91.

28

Author’s own calculations on figures taken from webpages and season brochures from 2010-2021 of selected theatre companies: Melbourne Theatre

Company (Vic), Black Swan State Theatre Company (WA), Queensland Theatre Company (Qld), and State Theatre Company of South Australia (SA).

•

per

cap1ta

FIGHTING

INEQUAL

I

TY

IN

AUSTRALIA

National Cultural Policy

Submission 13

7

PER

CAPIT

Table 1

29

Equivalised gross household

income

Highest educational

attainment

Region

Year

Lowest quintile

Highest

quintile

Postgraduate

degree

Year 12

Capital

cities

Balance of

state/territory

2005-6

11.6 %

25.4 %

29.2 %

16.9 %

17.9 %

15.5 %

2009-10

10.1 %

26.6 %

231.8 %

14.0 %

17.6 %

14.1 %

2017-18

9.4 %

25.6 %

29.0 %

13.2 %

17.6 %

14.2 %

Difference in

attendance rate 2005-

6 to 2017-18

2.2 %

-0.2 %

0.2 %

3.7 %

0.3 %

1.3 %

State theatre companies are doing more with less

Throughout rolling cuts to our cultural institutions, publicly subsidised theatre companies have been

innovating and adjusting to ensure Australian stories remain on our stages. But the lack of funding is forcing

them to rely more heavily on other revenue.

Figures 5-7, highlight the financial stress placed on these companies. Figure 5 looks at Australia Council base

funding as a percentage of total yearly revenue, Figure 6 looks at all Commonwealth, State and Local

Government funding as a percentage of total yearly revenue; and Figure 7 looks at a consolidation of four

companies’ Australia Council base funding adjusted by CPI.

With such little funding, it’s difficult to describe them as public, state or subsidised theatre companies at all.

29

Author’s own calculation from figures taken from ABS, 2013-14 missing relevant figures: Australian Bureau of Statistics, Attendance at Selected

Cultural Venues and Events, Australia, 2017-18 (Catalogue No 4114.0, 26 March 2019) Table 2,6-7; Australian Bureau of Statistics, Attendance at

Selected Cultural Venues and Events, Australia, 2009-10 (Catalogue No 4114.0, 21 December 2010) Table 2,7-8; Australian Bureau of Statistics,

Attendance at Selected Cultural Venues and Events, Australia, 2005-06 (Catalogue No 4114.0, 25 January 2007) Table 2,8-9.

•

per

cap1ta

FIGHTING

INEQUAL

I

TY

IN

AUSTRALIA

National Cultural Policy

Submission 13

100%

90%

80%

70%

60%

50%

40%

30%

20%

10%

0%

100%

90%

80%

70%

60%

50%

40%

30%

20%

10%

0%

Company A

■

Australia Council b

ase

funding as %

of

total yearly revenue

■

Other revenue

CompanyC

20

10 2011 2012 2013

20

14

20

15 2016 2017 2018

20

19 2020 2021

■

Australia Council b

ase

funding as %

of

total yearly revenue

■

Other revenue

Fip;me

5

30

100%

90%

80%

70%

60%

50%

40%

30%

20%

10%

0%

CompanyB

■

Australia Council b

ase

funding as %

of

total yearly revenue

■

Other revenue

General%

General%

General%

General%

General%

General%

General%

General%

General%

General%

General%

CompanyD

■

Australia Council b

ase

funding as %

of

total yearly revenue

■

Other revenue

30

Author's

own

calculations

on

figures taken from annual reports

and

financial reports from

20

10-2021

of

selected theatre companies: Melbourne

Theatre Company (Vic), Black

Swan

State Theatre Company

(WA

), Queensland Theatre Company (Qld), and State Theatre Company

of

South

Australia (SA). Data missing from Company D.

•

per

cap1ta

FI G

HT

I

NG

IN

EQUA

LI

TY

I N A

UST

R

ALIA

8

National Cultural Policy

Submission 13

Company A

100%

90%

80%

70%

60%

50%

40%

30%

20%

10%

I I

0%

• • • • • I

■ Total

Commonwea

lth funding as % of total yearly revenue

■ Total State &

Local

Government

funding as %

of

total yearly revenue

■ Other revenue

100%

90%

80%

70%

60%

50%

40%

30%

20%

10%

0%

■

I I I

CompanyC

■

I

■

■ ■

I

■ Total

Commonwea

lth funding as % of total yearly revenue

■ Total State &

Local

Government

funding as %

of

total yearly revenue

■ Other revenue

Fip;me

6

31

CompanyB

100%

90%

80%

70%

60%

50%

40%

30%

20%

10%

0%

I • • • • • • • • • I I

■ Total

Commonwea

l

th

funding as % of

tota

l yearly revenue

■ Total State &

Local

Government

funding as %

of

total yearly revenue

■ Other revenue

100%

90%

80%

70%

60%

50%

40%

30%

20%

10%

0%

•

■

I

CompanyD

I I I I I

■ Total

Commonwea

l

th

funding as % of

tota

l yearly revenue

■ Total State &

Local

Government

funding as %

of

total yearly revenue

■ Other revenue

Fip;me

7

32

Australia Council b

ase

fund

ing

for

4 state theatre companies

(co

n

so

lidated)

5,100,000

5,050,000

5,000,000

4,950,000

4,900,000

4,850,000

4,800,000

4,750,000

Recommendations

and adjusted for inflation

Within the Policy

we

beli

eve

th

ere

is

space

fo

r fmther

deve

lopment

to

improve

audie

n

ce

access and promote

Australi

an

content in Australia's state theatre

compa

n

ies.

The

COVI

D-

19

pandemic,

alo

ng with bringing our

31

Ibid

.

32

Ibid

; adjusted for inflation using

CPI

(2010 = 100).

•

per

cap1ta

FI

GHT

I

NG

IN

EQUALITY

IN

AUSTRALIA

9

National Cultural Policy

Submission 13

10

PER

CAPIT

creative industries to a jarring halt, intensified divisions in our community. We believe the creative industries

can play a role in repairing these fault lines.

Our analysis shows that state theatre companies will do what they can to get Australian content on our public

stages. We are therefore not recommending content requirements, like that needed in other arts disciplines.

We applaud the return of funding to the Australia Council but make recommendations about additional

funding to ensure that Australian stories on our public stages can be seen by a wider section of our

community.

1. Introduce additional or conditional funding for state theatre companies for subsidising tickets to

encourage attendance from lower income Australians.

2. Undertake further research into the demographics of audiences with a particular focus on the

demographics of theatre attendees at free or discounted productions at state theatre companies.

Conclusion

The Policy outlines ‘a place for every story, a story for every place’. Per Capita submits that it should

maintain a focus on a third tenet: a place for every Australian.

We acknowledge the decades of campaigning by creative industry workers, and the Australian public, who

have fought for a restoration of our creative industries and demanded it be on the government’s agenda.

We acknowledge the Albanese Labor Government, who has listened and acted in developing this Policy,

along with all the contributors from across Australia’s creative industries.

We thank the members of the Senate Standing Committees on Environment and Communications for their

consideration of this submission.

Publicly subsidised theatre companies should be subsidised for the benefit of the entire public. If not, we risk

publicly funded arts being only accessible to the privileged elite and lose the benefits of social cohesion that

come with our stages showcasing stories about our diversity: race, gender, sexuality, and class.

This is how we democratise the arts in our country. This is how we create a true class act.

•

per

cap1ta

FIGHTING

INEQUAL

I

TY

IN

AUSTRALIA

National Cultural Policy

Submission 13