Old Dominion University

ODU Digital Commons

Human Movement Sciences Faculty Publications Human Movement Sciences

2013

Proceed to Checkout? !e Impact of Time in

Advanced Ticket Purchase Decisions

Brendan Dwyer

Joris Drayer

Stephen L. Shapiro

Old Dominion University, [email protected]du

Follow this and additional works at: h=ps://digitalcommons.odu.edu/hms_fac_pubs

Part of the Marketing Commons, Sales and Merchandising Commons, and the Sports Sciences

Commons

<is Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Human Movement Sciences at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion

in Human Movement Sciences Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact

Repository Citation

Dwyer, Brendan; Drayer, Joris; and Shapiro, Stephen L., "Proceed to Checkout? <e Impact of Time in Advanced Ticket Purchase

Decisions" (2013). Human Movement Sciences Faculty Publications. 22.

h=ps://digitalcommons.odu.edu/hms_fac_pubs/22

Original Publication Citation

Dwyer, B., Drayer, J., & Shapiro, S. (2013). Proceed to checkout? <e impact of time in advanced ticket purchase decisions. Sport

Marketing Quarterly, 22(3), 166-180.

166 Volume 22 • Number 3 • 2013 • Sport Marketing Quarterly

Sport Marketing Quarterly, 2013, 22, 166-180, © 2013 West Virginia University

Introduction

In an environment where several variables could

impede a consumer from attending a sporting event

(e.g., weather, mood, team performance), advanced

ticket sales provide a sport organization with the secu-

rity of guaranteed revenue. And while revenue from

multimedia rights are at an all-time high, event atten-

dance remains the largest revenue source for several

professional leagues including Major League Baseball

(MLB) and the National Hockey League (NHL; Fisher,

2010). As a result, advance selling has become a dis-

tinct marketing objective and ticketing strategy for

many organizations looking to combat consumer sov-

ereignty, uncertain event outcomes, and a highly com-

petitive marketplace (Hendrickson, 2012).

The proliferation of the secondary ticket market,

which provides consumers with multiple purchase

options, has also been a function of the growing

importance of advanced ticket sales in sport. Where

ticket sources were once limited to the organization or

ticket scalpers, the contemporary sport consumer now

has several advance ticket purchase options. For

instance, one can obviously still purchase directly from

the sport organization (primary market). However, if a

sellout occurs, or even if tickets are still available

directly from the team, secondary market platforms

such as StubHub or eBay provide potential consumers

additional purchase options. As a result, organizations

in the primary market must adapt to an evolving mar-

ketplace and develop appropriate marketing strategies

to ensure advanced purchases.

Further complicating advanced sales, and consumer

behavior in general, are the varying levels of attach-

ment associated with sport consumers (Koo & Hardin,

2008). Several researchers have suggested that sport

organizations intentionally underprice their tickets at

least in part to ensure that consumers maintain their

positive feelings about the team (Coates & Humphreys,

2007; Fort, 2004; Krautmann & Berri, 2007). However,

Drayer and Shapiro (2011) found that “fans who have

stronger team identification or loyalty are willing to

pay more to see the team play” (p. 396). Additionally,

highly identified sport consumers are less affected by

Proceed to Checkout?

The Impact of Time in Advanced

Ticket Purchase Decisions

Brendan Dwyer, Joris Drayer, and Stephen L. Shapiro

Brendan Dwyer, PhD, is an assistant professor and the director of research and distance learning for the Center for Sport

Leadership at Virginia Commonwealth University. His research interests include sport consumer behavior with a distinct

focus on the media consumption habits of fantasy sport participants.

Joris Drayer, PhD, is an associate professor and the director of programs in sport and recreation management at Temple

University. His research interests include ticketing and pricing strategies in both primary and secondary ticket markets, as

well as consumer behavior.

Stephen L. Shapiro, PhD, is an assistant professor of sport management at Old Dominion University. His research focuses

on financial management in college athletics, ticket pricing in college and professional sport, and consumer behavior.

Abstract

When purchasing tickets in advance, sports consumers are often faced with uncertainty. Most notably, in

today’s real-time environment, it can be challenging for consumers to determine how ticket prices and seat

availability will change over time. Guided by the generic advanced-booking decision model, the current

study investigated the role of time, ticket source (primary or secondary market), and team identification in

advanced ticket purchasing by exploring a consumer’s perceptions of ticket availability and finding a lower

price. The results suggest the perceived likelihood of ticket availability and finding a lower priced ticket

increased as the date of the game drew closer. Ticket source and team identification were also found to be

statistically significant main effects factors, while ticket source significantly moderated consumer percep-

tions of finding a lower price over time. These outcomes both confirm and contradict various findings in

the leisure literature and provide a strong foundation for future sport-related examinations.

Abstract

When purchasing tickets in advance, sports consumers are often faced with uncertainty. Most notably, in

today's real-time environment, it can be challenging for consumers to determine how ticket prices and seat

availability

will change over time. Guided by the generic advanced-booking decision model, the current

study investigated the role

of

time, ticket source (primary

or

secondary market), and team identification in

advanced ticket purchasing by exploring a consumer's perceptions

of

ticket availability and finding a lower

price. The results suggest the perceived likelihood

of

ticket availability and finding a lower priced ticket

increased

as

the date

of

the game drew closer. Ticket source and team identification were also found to be

statistically significant main effects factors, while ticket source significantly moderated consumer percep-

tions

of

finding a lower price over time. These outcomes both confirm and contradict various findings in

the leisure literature and provide a strong foundation for future sport-related examinations.

Volume 22 • Number 3 • 2013 • Sport Marketing Quarterly 167

fluctuations in team performance (Branscombe &

Wann, 1991; Wann & Branscombe, 1993). That said,

less-identified sport consumers are equally important

to sport organizations, and despite more dramatic

demand fluctuations based on team performance,

teams must continually recruit and retain this group of

potential consumers (Whitney, 1988). In the end,

despite the difficulty in establishing different market-

ing strategies based on team identification, it has been

established as a primary market segmentation strategy.

Empirical research related to team identification and

advance ticketing strategies is lacking.

In addition to ticket source and team identification,

perhaps the most important variable in the advance

sales equation is time. With several options from

which to purchase, varying levels of team interest, and

ultimately, multiple market factors related to ticket

supply and demand, sport consumers are forced to

speculate before acting. It is challenging for consumers

to speculate how ticket prices and seat availability will

change over time, not to mention the difficulty of

speculating on the consumer utility factors listed above

(e.g., weather, mood, and team record). Previous

research on demand-based pricing in sport has provid-

ed evidence of price shifts based on both time and

availability of tickets (Drayer & Shapiro, 2009; Shapiro

& Drayer, 2012). However, consumer perceptions of

these influences and how they affect purchase decisions

within the context of sporting events have not been

explored. Thus, guided by the generic advanced-book-

ing decision model (Schwartz, 2000; 2006), this study

systematically explored the role of time in an

advanced-purchasing setting. In addition, the study

examined ticket source (primary or secondary market)

and team identification as potential moderators of the

advanced sport ticketing process. Given the direct rela-

tionship between a consumer’s advanced purchasing

behavior and an organization’s pricing decisions, it is

believed that a more comprehensive understanding of

the sport consumer decision making process in an

advanced-sales setting will aid sport organizations in

implementing more effective pricing and revenue

management tactics.

Review of Literature

Ticketing Strategies and Sources

Traditional ticket pricing strategies used seat location

as the primary factor in determining price differences

between tickets. Around the turn of the millennium,

several professional sports franchises introduced vari-

able ticket pricing (VTP) which allowed them to use

additional factors in setting prices such as opponent

and day of the week. However, as these prices were set

before the start of the season, they still ignored the

changes in consumer demand for these events over the

course of the season. Subsequently, in 2009, the San

Francisco Giants introduced dynamic ticket pricing

(DTP) where prices changed daily based on fluctuating

demand conditions. Over half of the teams in MLB

along with several more in the NHL and National

Basketball Association (NBA) have now adopted some

form of DTP.

While understanding what factors to consider when

setting prices on a daily basis is a difficult task, a wealth

of previous literature has examined changes in con-

sumer demand. For example, when considering the

quality of the game, several researchers have focused on

changes in attendance based on the expected outcome.

Using a variety of measures including betting odds

(Welki & Zlatoper, 1999), difference in league ranking

(Garcia & Rodriguez, 2002), average number of games

behind the first place team (Noll, 1974), and differences

in games won (Price & Sen, 2003), these researchers

examined how outcome (un)certainty may influence

consumer demand for an event. There is no shortage of

research on the factors influencing consumer demand

(see Borland & McDonald, 2003, for a summary of

such studies). However, these studies examined con-

sumer demand based on fluctuations in attendance and

did not consider how these factors may influence con-

sumer attitudes and/or their willingness to pay for tick-

ets. Further, DTP considers how these factors change

over time suggesting that perhaps the importance of

these factors may be influenced by time itself.

The evolution of primary market pricing strategies

from a seat-location-based approach to VTP, and

eventually DTP, coincides with the growth of the sec-

ondary market. With the ability of the Internet to

quickly and conveniently facilitate transactions, this

resale market has evolved into a legitimate, multi-bil-

lion dollar industry (Drayer & Martin, 2010). In this

transparent, free-market environment, research has

been conducted which has further illuminated cus-

tomer preferences for tickets. For example, Drayer and

Shapiro (2009) examined online auctions on eBay and

determined that several factors, including home and

visiting team performance, population, and day of the

week influenced the amount customers were willing to

bid for tickets. Additionally, they found the number of

days before the game affected final auction prices. In

other words, prices decreased as the event drew closer.

Shapiro and Drayer (2012) also compared dynamic

prices in the primary market to secondary market

prices on StubHub. They determined sellers in the pri-

mary market steadily increase prices over time while

secondary market sellers were more inclined to lower

prices over time. In this case, sellers’ consideration of

168 Volume 22 • Number 3 • 2013 • Sport Marketing Quarterly

the effect of time on consumers’ willingness to pay is

quite different. This suggests the phenomenon is in

need of further examination.

The influence of time was also apparent in the work

of Moe, Fader, and Kahn (2011), who found ticket

sales were influenced by constantly fluctuating factors

such as team performance and days before the game.

As attractiveness of teams fluctuates based on perform-

ance, and the game date nears, ticket sales and seat

location choices change. The authors concluded data-

driven pricing decisions based on consumer demand

are most likely to capture true value of the ticket as

prices can change based on outcome uncertainty.

Of course, consumers’ perceptions of the source of

these tickets may also influence consumers’ perception

of the ticket being offered. The studies mentioned pre-

viously focus primarily on sellers’ price setting strate-

gies and ignore how consumer perceptions of the

product may influence these consumption decisions.

There is a wide array of research suggesting that con-

sumers’ perception of a product goes beyond the

extrinsic characteristics and may be influenced by

other intrinsic attributes such as perceived trustworthi-

ness of the seller and experience with similar transac-

tions in the past (i.e., reference transactions). For

example, Xia, Monroe, and Cox (2004) found that

transaction similarity and buyer-seller relationship

influenced consumer attitudes. Within the tourism and

hospitality literature, several studies have considered

consumers’ perceptions of the seller. However, given

that the product is guaranteed to be the same across all

platforms, third party websites’ formalized relation-

ships with hotels. Several studies have focused primari-

ly on the fairness of sellers’ pricing strategies (Choi &

Mattila, 2005; Kimes, 2003; Wirtz & Kimes, 2007).

There are, however, differences between tourism and

sport. Specifically, third party sellers (i.e., secondary

market sellers) are not supplied with tickets from sport

organizations through any contractual relationship,

meaning that consumers may be uncertain about the

authenticity of the ticket. One of the unique features of

the secondary market is that perceptions of the indus-

try have been affected by previous instances of unethi-

cal business practices and the existence of laws in many

states that makes ticket resale illegal (Drayer & Martin,

2010). Thus, consumers’ perceptions may be affected

by not only the price of the ticket but also their per-

ception of the source. However, to date, no research

has explored how ticket source affects consumers’ atti-

tudes and purchase intentions. In the advanced ticket

purchase setting, ticket source may be an intriguing

and timely variable as sport consumers are no longer

strictly limited to a team’s pricing structure.

Team Identification

Identification refers to the roles an individual plays

within a network of social relationships (Stryker &

Burke, 2000). Identities are organized and conceptual-

ized through social interactions, and these identities

can influence behavior (Stryker, 1968, 1980). Social

interactions not only affect the development of identi-

fication, but these interactions impact the salience of

these identities. This is the foundation of identity theo-

ry proposed by Stryker (1968, 1980).

Various facets of identity theory have been examined

in social-science research providing significant evi-

dence of the role identity plays in the decision making

process. Within the context of sport marketing, there is

a wealth of literature on the role of identification and

its relationship with other aspects of sport consumer

behavior (Lock, Taylor, Funk, & Darcy, 2012; Fink,

Trail, & Anderson, 2002; Trail, Anderson, & Fink,

2000; Wann & Branscombe, 1993; Zillman, Bryant, &

Sapolsky, 1989). According to Wann and Branscombe

(1993), team identification can be used not only to

understand the interaction between sport consumers

and teams, but to gauge the level of consumer behav-

ior. In essence, team identification can help predict

sport consumption.

Some of the early research on sport and identifica-

tion claimed spectator sport provides an opportunity

for individuals to establish a sense of belonging and

develop relationships with other sport consumers who

identify highly with a team (Zillman et al., 1989). High

levels of identification with a team have been shown to

enhance one’s allegiance to that team regardless of per-

formance (Branscombe & Wann, 1991). This is an

important point of emphasis, as the literature on

demand in sport has consistently identified a positive

relationship between team performance and atten-

dance (Hansen & Gauthier, 1989; Lemke, Leonard, &

Tlhokwane, 2010; Noll, 1974; Whitney, 1988). In gen-

eral, consumers attend fewer games when a team does

not perform well. In the case of highly identified con-

sumers, however, team performance is less of a factor

(Branscombe & Wann, 1991; Wann & Branscombe,

1993).

Additionally, team identification has been shown to

influence consumption within a variety of contexts

beyond event attendance. Wann and Branscombe

(1993) found highly identified sport consumers tend to

invest more time and resources into their favorite

team. Subsequent examinations have supported these

findings. Wakefield (1995) found a positive relation-

ship between team identification and re-patronage,

providing some of the first evidence that a consumer’s

attachment to team can have an effect on future inten-

tions. Trail et al. (2000) and Trail, Fink, and Anderson

Volume 22 • Number 3 • 2013 • Sport Marketing Quarterly 169

(2003) found highly identified sport consumers are

more likely to attend games. Additionally, Trail et al.

(2003) discovered these consumers purchase more

team-related merchandise.

In terms of team identification moderating various

attitudes and behavior within the context of sport, the

research is limited. Trail et al. (2012) examined

whether team identification moderated the relation-

ship between vicarious achievement and basking in

reflected glory (BIRGing) or cutting off reflective fail-

ure (CORFing). There were no interacting effects

found for the moderating models. However, Wann

and Branscombe (1993) suggest this moderated rela-

tionship could exist based on the fact that individuals

with high team identification would be more likely to

support the team and less likely to reject them regard-

less of outcome. The extent to which a relationship

between time and ticket purchase decisions might be

influenced by attachment to a team is unknown.

Although there is strong support for the relationship

between team identification and consumption, little is

known regarding the level of team identity and the

ticket purchase process. In the current demand-based

pricing environment, where the price and number of

tickets available are constantly changing, it is impor-

tant to understand the role identification may play in a

sport consumer’s decision to purchase a ticket at a

given time before a game. This information becomes

more important as consumers begin to fully under-

stand the process of DTP and the secondary ticket

market, where prices may fluctuate daily making it dif-

ficult to determine the optimal purchase time and/or

price. The role of team identification in this process

should not be understated.

Theoretical Background

The generic advanced-booking decision model

(Schwartz, 2000; 2006) served as the theoretical foun-

dation for this study as it is grounded in the consumer

decision making process. This model was developed

and validated in the field of travel and tourism with

the particular aim at understanding the process of

hotel reservations. In general, the literature on

advanced selling comes almost exclusively from the

field of travel and tourism (e.g., airlines & hotels)

where price discrimination and yield management

strategies have been found to provide competitive

advantages for gaining market share, ensuring capacity

fulfillment, and ultimately, creating profitability (Gale

& Holmes, 1992; Shugan & Xie, 2000; 2005; Xie &

Shugan, 2001).

However, the extension of this particular theory to

the field of sport marketing is both logical and needed

(Gibson, 1998). First, several similarities exist in the

experiences of sport consumers and tourists with

respect to product and service consumption. For

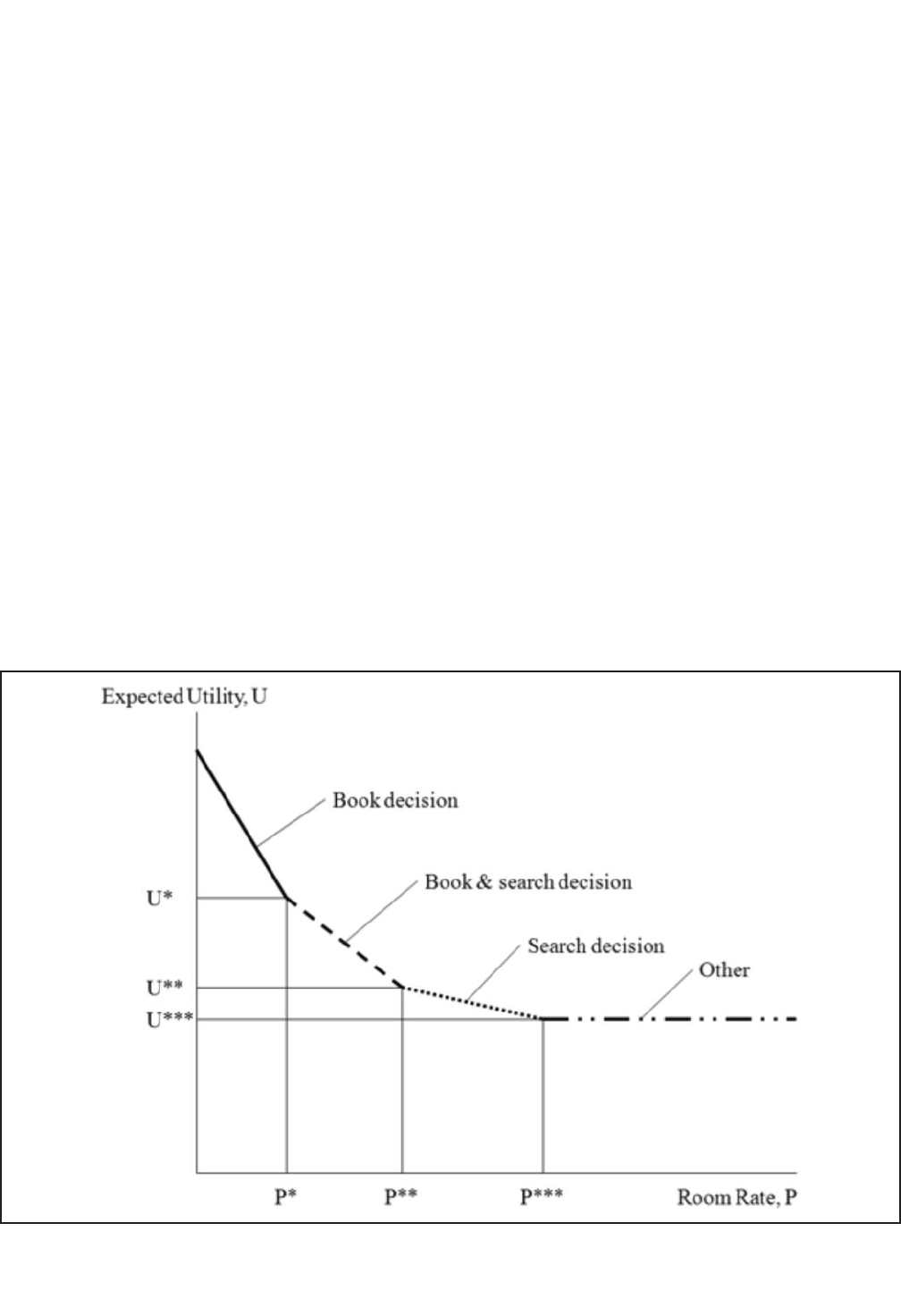

Figure 1. Generic Advanced-Booking Decision Model (Schwartz, 2000; 2006) Rates and Optimal Zones

'

'

Bookd 1

100

'

*

1---------1----

- ....

bd l

100

ar h

·····

...

***

1--------lf-----i----

··-

··

-·~

·--

p

***

m

at

• P

170 Volume 22 • Number 3 • 2013 • Sport Marketing Quarterly

instance, similar to staying in a hotel, attending a

sporting event is a perishable experience driven by the

intersection of tickets available (hotel rooms available),

ticket price (room rate), and consumer demand.

Second, purchasing a ticket or reserving a room in

advance have similar uncertainties related to availabili-

ty as limited information about alternatives is readily

accessible. Lastly, due the similarities between the

tourist and sport consumer experiences, there is a

growing need to bridge theoretical gaps between the

two fields (Gibson, 1998).

According to the model, prospective consumers have

four different generic decision options as they respond

to a price quoted by a hotel: (1) reserve the hotel

room, (2) reserve the room and continue searching for

a better rate, (3) not reserve and continue searching for

a better rate, or (4) disregard the hotel entirely and

consider alternatives. Placed on an expected utility-rate

plane, as depicted in Figure 1, one can see three strate-

gic switching points where one must choose between

the rate quoted by the hotel and the other options. The

model assumes risk neutral consumers that choose the

action in which their expected utility is maximized.

Several variables are at play in the determination of the

switching points including the search cost, the dis-

count the consumer expects the hotel will offer in the

future, the probability the hotel will sell out, the prob-

ability that a discounted rate will be offered after a

given number of periods of search, and the penalty for

canceling the reservation. From the hotel’s perspective,

it is preferable that the consumer choose option one

followed by option two, three, and four.

Clearly, the options available to sport consumers are

not exactly the same as it is not an accepted practice to

reserve a ticket while searching for alternatives. Most

ticket transactions are final. However, with the emer-

gence of the secondary ticket market, opportunities exist

to resell tickets purchased in advance to recoup some or

all of the cost. In the case of a high-demand event, sell-

ing a ticket on secondary ticket market may even result

in a substantial profit. Regardless, the specific options

available to sport consumers as compared to hotel con-

sumers are not of particular importance in this context.

In general, advance-booking consumers, sport or other-

wise, have several options when quoted a price, and it is

the incorporation of timing within the advanced-book-

ing model that makes the extension cogent.

In 2008, Schwartz extended the generic advanced-

booking model to include time as a variable claiming

the options available to consumers are not static over

time. In other words, holding all other factors con-

stant, the decision to reserve a hotel depends some-

what on how far out the purchase decision was from

the date of stay. Two specific variables in the model

were identified as important factors in the decision

making process as they relate to time. First, to ensure

occupied rooms, it has become common for hotels to

change prices as the date of stay nears based on supply

and demand. As mentioned above, DTP strategies that

account for fluctuating demand have emerged in pro-

fessional sports as a means to more effectively manage

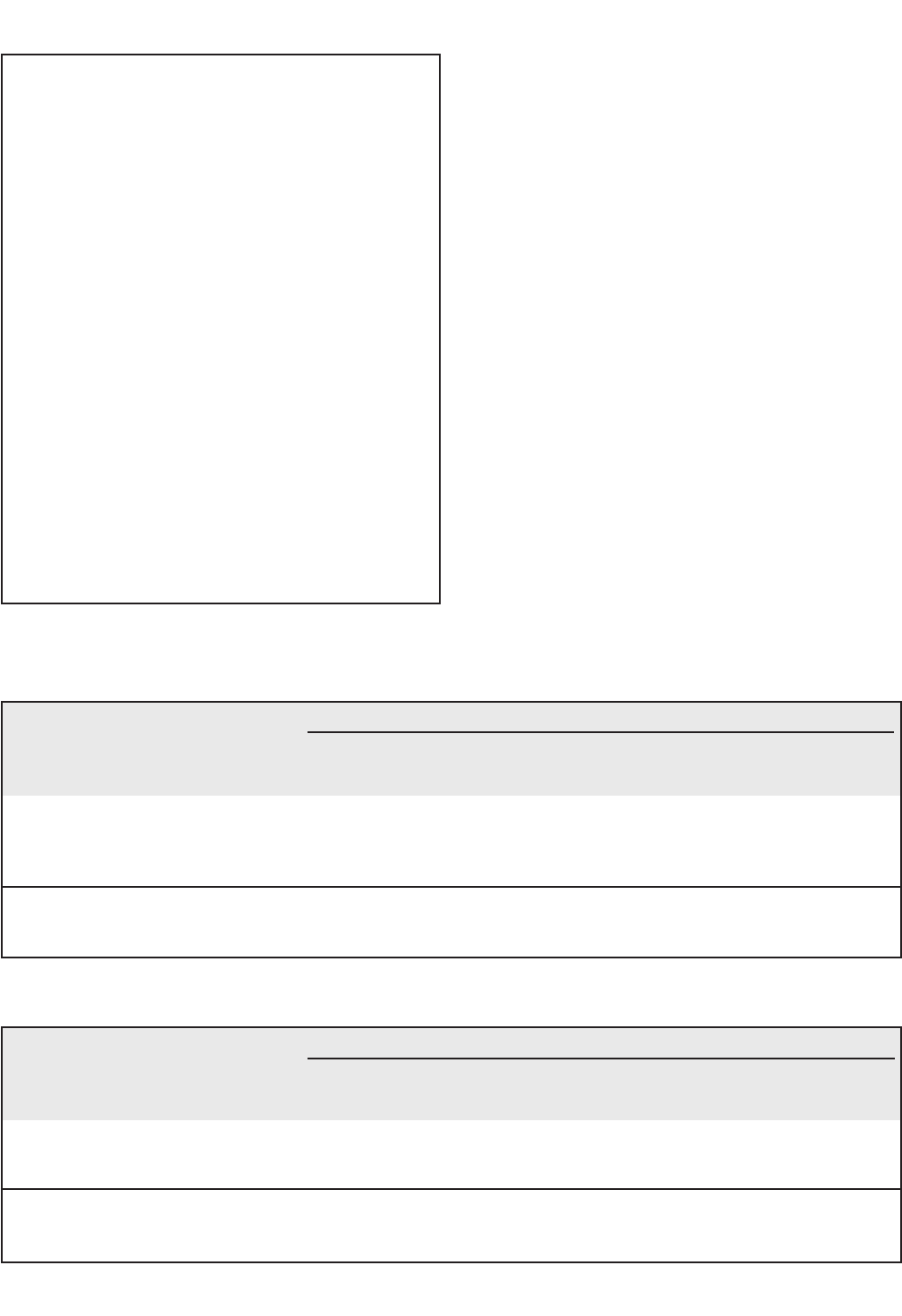

Figure 2. Conceptual Model for Research Questions 1 & 3

ility

.

u

r

Rt

'

'

'

ii

;

;

;

ii

;

;

;

;

------------------------------------·

t

Volume 22 • Number 3 • 2013 • Sport Marketing Quarterly 171

revenue. Thus, the probability that a discounted price

will be offered in the future (Expected Lower Rate

[ELR]) is an important variable in the advanced-book-

ing decision process. Second, the supply of hotel

rooms and sporting event tickets is limited; thus, the

probability the hotel or game will sell out (Expected

Ticket Availability [ETA]) is an important variable in

the purchasing process.

Schwartz (2008) argued for the testing of this time-

related extension of the advanced-booking model. It

was proposed that testing of the impact of time in a

booking decision would provide organizations a better

understanding of the time-related shifts in consumer

perception and propensity to book. As a result, organi-

zations could practice more effective revenue manage-

ment strategies. Chen and Schwartz (2008b) tested the

impact of time on ELR and ETA related to hotel book-

ing decisions and found that consumer perceptions

and expectations about variables related to advanced

booking changed as the date of stay neared. The

change patterns were more complicated than hypothe-

sized, and as a result, the authors suggested further

research. In particular, the authors recommended

investigations should focus on the final 21 days before

the intended hotel stay.

Similar empirical research in the field of sport man-

agement and marketing is lacking despite the fact that

understanding time-related shifts in demand would

provide vital revenue management information. Thus,

the current study explored the role of time in the

advanced-ticket purchasing decisions by first measur-

ing the impact of time on a sport consumer’s expecta-

tions of ticket availability (ETA) and finding lower

priced tickets (ELR) with respect to a given profession-

al sporting event. Second, given the potential impor-

tance of team identification and ticket source, these

variables were examined as moderators of the time,

ELR, and ETA relationship. Moderating relationships

were hypothesized for team identification and ticket

source because relationships between time, ELR, and

ETA have been established in the travel and tourism

literature, and similar relationships were hypothesized

for this study.

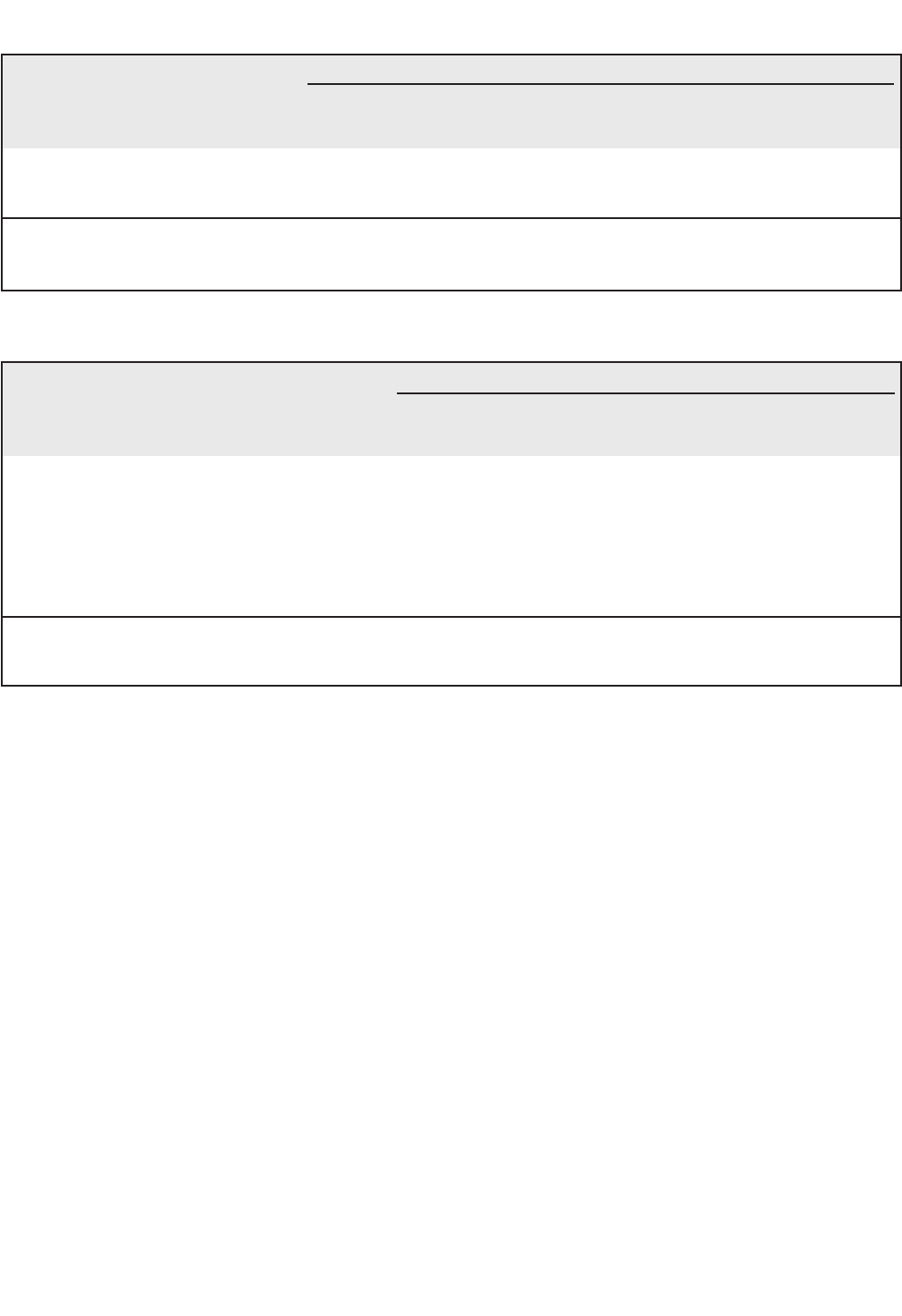

Figure 2 provides the conceptual model for the first

aim of the study, and Figure 3 provides the conceptual

model for the second. The solid lines denote relation-

ships examined in the current study where the dotted

lines were established by Schwartz (2000) or Chen and

Schwartz (2008a). The following research questions

were developed to guide the research:

Figure 3. Generic Advanced-Booking Decision Model (Schwartz, 2000; 2006) Rates and Optimal Zones

\

\

\

\

I

I

I

I

\

\

\

I

I

I

r p n ity

t B k

172 Volume 22 • Number 3 • 2013 • Sport Marketing Quarterly

RQ1: Does a consumer’s expectation of ticket

availability with respect to an upcoming profes-

sional sporting event differ over time?

RQ2: Is the relationship between consumer

expectation of ticket availability and days before

the event moderated by ticket source and/or team

identification?

RQ3: Does a consumer’s expectation of finding

lower priced tickets with respect to an upcoming

professional sporting event differ over time?

RQ4: Is the relationship between consumer

expectation of lower priced tickets and days before

the event moderated by ticket source and/or team

identification?

Method

Sample and Procedures

Through a partnership with the Philadelphia Inquirer,

the research team had access to a panel of over 2,300

Philadelphia area sports fans. As a result, a Philadelphia

Flyers’ home game against the Montreal Canadiens was

chosen as the context for the investigation. Participants

were solicited electronically via three date-specific

email blasts prior to a March 24th game. Within each

email, a brief message and link were provided to an

online questionnaire. The online questionnaire was

hosted by Qualtrics. An incentive was provided to

entice participation. Subjects who agreed to participate

were provided one of two written, imaged-enhanced

scenarios: (1) an opportunity to purchase a ticket from

the Flyers website, or (2) an opportunity to purchase

the same ticket from StubHub.com, the largest second-

ary ticket market website (see appendix). According to

the scenario, the participant and a friend decided to

attend the Saturday evening game, and the participant

volunteered to find tickets. They (according to the sce-

nario) went directly to the Flyers’ website or

StubHub.com and found a pair of lower level tickets

for $165 each. The arena seating chart was provided as

was an image of the view from the seat. After reading

the scenario, the subjects were asked to answer two

questions estimating the probability of future events

(the two dependent variables). Team identification and

demographic information was collected as well.

Variables

Independent variable. The independent variable was

time, specifically the number of days before the hockey

game. Three levels were chosen based on previous trav-

el research and secondary data provided by StubHub.

While purchasing tickets in advance may occur any

time after the season schedule is released, the volume

of secondary market transactions that occurred within

the last three weeks leading up to the event was sub-

stantial enough to warrant a shorter range of dates. In

addition, the time related work of Chen and Schwartz

(2008b) resulted in greater variability within this range.

As a result, six, 13, and 19 days prior to the game were

selected. Participants were randomly assigned to one of

the three treatments via email solicitation.

Dependent variables. The two dependent variables for

this study were ETA, a participant’s assessment of the

expected availability of the same or similar ticket

between the scenario date and the game, and ELR, a

participant’s assessment of finding a similar priced

ticket between the scenario date and the game. Both

variables were measured by percentage expectation

between 0 and 100. Similar measures were used in

Chen and Schwartz’s (2008b) study of hotel room rates

and time.

Moderating variables. Ticket source, either primary

(Flyers.com) or secondary (StubHub.com), was added

as a moderating variable given the possibility that the

secondary ticket market may influence consumer

behavior (Carter, 2012). Subjects were randomly

assigned one of two ticket sources and grouped as

such. In addition, team identification was examined as

a potential moderator to investigate the importance of

team fandom as a function of time, ETA, and ELR.

Team identification was assessed through Trail,

Robinson, Dick, and Gillentine’s (2003) team attach-

ment items from their larger Points of Attachment

Index. The three item scale used a seven point Likert

type (7=strongly agree; 1=strongly disagree).

Participants were placed into one of two groups (high

and low) based on their mean attachment score. A

score of less than four was deemed low and four or

greater was deemed high.

Statistical Tests

A multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was

conducted to determine the overall differences in the

mean likelihoods between groups. A MANOVA is the

appropriate statistical test to conduct when there are

multiple dependent variables that are moderately cor-

related (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007). Two 3x2x2 facto-

rial analyses of variance (ANOVA) were then

conducted to determine if there were any differences in

the mean assessments for each treatment. The main

effects results were analyzed for time to answer

research questions one and three while the interaction

effects were assessed for ticket source and time and,

team identification and time, and ticket source, team

identification, and time to answer research questions

two and four. A post hoc test (Tukey) was also con-

ducted to see which time treatment differed from the

others. Additionally, due to the use of the same

Volume 22 • Number 3 • 2013 • Sport Marketing Quarterly 173

dependent variables in two separate procedures, a

Bonferonni adjustment was made. The significance

value was set at .025 for all main effects.

Results

A total of 415 Philadelphia area sports fans responded

to the email solicitation with 389 fully completing the

survey resulting in a response rate of 16.9%. Table 1

provides demographic information for the sample.

Table 2 shows the number of observations in each of

the three time treatments as well as the averages and

standard deviations for each of the two dependent

variables (ELR and ETA). Respondents who were

solicited 19 days before the hockey game estimated the

likelihood of the same or similar tickets being available

sometime during the next 18 days to be 35.9%. At 13

days, the respondents estimated the ticket availability

to be 47.1%, and the respondents at six days estimated

the availability to be 52.5%. With regard to lower tick-

et prices, the respondents at 19 days estimated the like-

lihood of finding the same or similar tickets at a lower

price during the next 18 days to be 31.1%. The respon-

dents at 13 days out estimated the probability to be

43.6%, and at six days, the respondents estimated the

probability to be 48.6%. In general, as the game drew

Table 1

Sample Demographics

Age 33.674, Mean

11.792, SD

Ethnicity 92.0%, Caucasian

5.7%, Other

2.3%, Did not specify

Education 6.4%, High School

41.1%, Bachelor’s Degree

18.0%, Graduate Degree

16.5%, Professional Degree

7.7%, Other

9.0%, Did not specify

Gender 79.2%, Male

14.9%, Female

5.9%, Did not specify

Household Income 12.3%, Less than $50K

30.1%, $50K-$99K

24.7%, $100K-$150K

6.1%, More than $150K

16.8%, Did not specify

Table 2

Expected ticket availability (ETA) and expected lower rate (ELR) by days before the event

Expected Ticket Availability Expected Lower Rate

Days Before Number of Average (%)

a

SD Average (%)

b

SD

the Game Observations

6 119 52.5 24.7 48.6 26.5

13 135 47.1 30.5 43.6 28.2

19 135 35.9 27.4 31.3 28.8

a

Main effects result, p < .001

b

Main effects result, p < .001

Table 3

Expected ticket availability (ETA) and expected lower rate (ELR) by ticket source

Expected Ticket Availability Expected Lower Rate

Ticket Source Number of Average (%)

a

SD Average (%)

b

SD

Observations

Flyers Website 193 36.7 26.5 32.5 27.5

StubHub.com 196 52.7 27.2 49.9 27.6

a

Main effects result, p < .001

b

Main effects result, p < .001

174 Volume 22 • Number 3 • 2013 • Sport Marketing Quarterly

closer, the respondents’ perceived probability of both

ticket availability and finding lower ticket prices

increased with the biggest jump occurring between 19

days out and 13.

The MANOVA test was significant F(4,770) = 6.25,

p<.001 suggesting the participants in each time period

differed in regard to their assessments of ETA and

ELR. Based on the MANOVA results, the subsequent

factorial ANOVAs were conducted. The main effects

results of the ETA factorial ANOVA with regard to

time suggest that the respondents’ estimate of ticket

availability differed between the treatments F(2,377) =

13.50, p<.001. The Tukey HSD post hoc test indicated

that the respondents’ estimate of ticket availability at

19 days was significantly lower than the respondents at

13 and six days. No difference existed between the

groups at 13 and six days. The main effects results of

ETA with regard to ticket source F(1,377) = 30.05,

p<.001 and team identification F(1,377) = 6.69; p =

.010 also resulted in statistically significant differences;.

Respondents provided with the StubHub.com scenario

felt the probability the same or similar ticket would be

available between the scenario date and the date of the

game was higher than those provided with the

Flyers.com scenario. Meanwhile, those with a higher

level of team identification felt there was a better prob-

ability the same or similar ticket would be available

between the scenario date and the date of the game

than those with a lower level of team identification.

Tables 3 and 4 provide the main effects results for tick-

et source and team identification.

The interaction effect results with regard to moderat-

ing influence of ticket source and time was significant

F(2,377) = 3.20; p = .008. As can be seen in Table 5, 19

days before the game, respondents provided with the

StubHub.com purchasing scenario felt there was a

higher probability the same or a similar ticket would

be available in the days leading up to the game com-

pared to those provided with the Flyer’s website sce-

nario. The same interaction effect was true for the

respondents presented with the differing scenarios 13

days out and six days out. The other possible modera-

tors of ETA (time x team identification, source x team

identification, time x source x team identification) did

not result in a statistically significant interaction effect.

The main effects results of the ELR factorial ANOVA

with regard to time was also statistically significant

indicating a difference between the treatments F(2,377)

Table 4

Expected ticket availability (ETA) and expected lower rate (ELR) by team identification

Expected Ticket Availability Expected Lower Rate

Level of Team Number of Average (%)

a

SD Average (%)

b

SD

Identification Observations

Low 171 40.7 26.0 36.6 28.0

High 218 47.7 29.1 44.8 28.8

a

Main effects result, p = .01

b

Main effects result, p = .003

Table 5

Expected lower rate (ELR) and expected availability (EA) by days before the event and ticket source interaction

Expected Ticket Availability Expected Lower Rate

Days Before Ticket Number of Average (%)

a

SD Average (%)

b

SD

the Game Source Observations

6 Flyers Website 57 42.8 23.9 37.5 24.6

StubHub.com 62 56.3 23.9 54.5 26.5

13 Flyers Website 68 35.1 26.5 35.2 26.7

StubHub.com 67 57.1 30.1 54.4 28.2

19 Flyers Website 68 32.2 28.2 22.6 26.6

StubHub.com 67 42.7 25.5 39.1 28.8

a

Main effects result, p = .041

b

Main effects result, p = .018

Volume 22 • Number 3 • 2013 • Sport Marketing Quarterly 175

= 5.58; p =.004. Similar to the ETA results, the post

hoc findings indicate the respondents’ estimate of find-

ing lower ticket prices 19 days out was lower than the

groups at 13 and six days. No difference resulted

between the groups at 13 and six days prior to the

game. Statistically significant differences resulted for

the main effects of ticket source F(1,377) = 36.44,

p<.001 and team identification F(1,377) = 9.23, p =

.003 with regard to ELR. Once again similar to the ETA

results, respondents provided with the StubHub.com

scenario felt the probability of finding a similar ticket

at a lower price between the scenario date and the date

of the game was higher than those provided with the

Flyers.com scenario. In addition, those with a higher

level of team identification felt there was a better prob-

ability of finding a lower priced ticket compared to

those with lower identification levels.

The interaction effect between time and ticket source

was once again statistically significant F(2,377) = 2.33

p = .023 suggesting respondents provided the

StubHub.com scenario at each time interval felt there

was better probability of finding a similar ticket for a

lower price than those provided the Flyer website sce-

nario. The other possible moderators of ELR (time x

team identification, source x team identification, time

x source x team identification) did not result in a sta-

tistically significant interaction effect.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to systematically investi-

gate the impact of time in the advanced-booking setting

of a professional hockey game. Ticket source and team

identification were also examined as potential moderat-

ing variables between time before the event and a con-

sumer’s estimation of ticket availability and finding

lower priced tickets. The results suggest that as time

before the event decreased, a consumer’s estimation of

ticket availability and finding a lower ticket price

increased significantly. In addition, respondents pro-

vided with the secondary ticket source (StubHub) had a

higher estimation of ticket availability and finding a

lower ticket price than those presented with the pri-

mary source (Flyers’ website) scenario. Respondents

with a higher level of team identification also had high-

er estimations for both dependent variables than the

respondents with a lower level attachment to the Flyers.

With respect to previous applications of the generic

advanced-booking decision model, the results appear

to mildly parallel the impact of time on consumer per-

ceptions of availability and price (Chen & Schwartz,

2008b). However, the results soundly confirm the

impact of time as an influential variable within the

consumer decision process, as statistically significant

differences existed with respect to consumer probabili-

ty over time (Chen & Schwartz, 2008a; 2008b).

Therefore, the future application of the theoretical

model in the field of sport marketing should include

data from different points in time. Preferably, the

inclusion of several points of time may provide more

insight to the specific influence of time. In addition, a

more complete understanding as to why consumers

perceive ticket prices will decrease and availability will

increase or stay constant as time before the event

decreases is needed. Howard and Crompton (2004)

suggested the sport industry was headed towards more

consumer focused pricing strategies as opposed to pre-

vious regimes’ aim at covering organizational costs. In

that case, further empirical research related to the

impact of time, consumer perceptions, and the

advanced booking process is strongly suggested. A

more complete understanding of consumer percep-

tions of ticket price and availability over time will pro-

vide for more effective pricing strategies, revenue

management tactics, and ultimately, less empty seats in

the stadium.

Additionally, these findings are consistent with pre-

vious sport literature stating the effect of time on price,

which has focused on consumer demand for tickets

(Moe et al., 2011; Shapiro & Drayer, 2012). Moe et al.

(2011) found that in addition to team performance,

time played a significant role in ticket sales numbers.

Ticket sales appear to fluctuate more rapidly as the

game draws closer. This finding was also supported by

Shapiro and Drayer’s (2012) examination of San

Francisco Giants ticket prices during the first full year

of DTP implementation. In the primary market ticket

prices gradually increased as the game drew closer,

where in the secondary market, ticket prices rose ini-

tially (approximately a month before the game) and

then dropped considerably leading up to game time.

These examinations focused on actual ticket sales and

price data. The current study supports the impact of

time in terms of the consumer’s perception of price

and availability, suggesting a global influence from

both the organization and consumer perspective.

The distinct impact of ticket source as both a main

effects and moderating effect on a consumer’s percep-

tion of price and availability is a finding new to both

the tourism and sport literature. Obviously, the number

of studies in this area is small, but statistically signifi-

cant differences in consumer estimations by ticket

source were present. Similarly, the differences between

the primary source-participants expanded as time

before the game decreased, as the respondents with the

primary source scenario felt less likely to find lower

priced tickets and less likely the seats would remain

available. Several possible explanations may exist as to

why this phenomenon is occurring. For instance, per-

haps consumers perceive the prices offered on StubHub

are more fluid than prices offered by the Flyers, or per-

haps the same perception exists with regard to the

number of options for similar tickets on StubHub com-

pared to the team’s website. It could also be a function

of the general consumer’s lack of awareness of DTP

from a team’s perspective. Obviously, these are just

suggested possibilities, as the answers to these proposi-

tions go far beyond the scope of the current results, but

it is important to note that the probabilities were differ-

ent based on ticket source and ticket source and time;

thus, several questions remain. For instance, what do

these results have to do with the popularity of second-

ary ticket market and/or consumer familiarity with

these platforms? In addition, are these results unique to

sport or is it unique to secondary markets? Further

research in this area is highly-advised.

Team identification was not found to be a moderat-

ing variable as hypothesized, but it was determined to

be an influential variable within the advanced-purchas-

ing process. The inclusion of this variable was based

partly on the uniqueness of sport in eliciting a one-of-

a-kind connection between a consumer and the prod-

uct. Previous research had already established the

importance of team identification in association with

consumption and event attendance (Trail et al., 2000;

Trail et al., 2003; Wakefield, 1995). Therefore, as a

result of this bond, there was a possibility highly-identi-

fied consumers would behave irrationally with respect

to time and estimations of price and availability.

However, the results suggested no significant relation-

ship with time and the dependent variables existed, and

highly-identified consumers actually indicated higher

estimations of ticket availability and finding a lower

price. Perhaps highly-identified consumers are not only

more attached to the team, but also more knowledge-

able of the advanced ticketing process. That is, these

consumers may be more aware of the ticket market and

price fluctuations through DTP and the secondary mar-

ket. Research related to team identification and con-

sumer knowledge is sparse. Wann and Branscombe

(1995) found a relationship between team identification

and objective/subjective knowledge of the sports team,

but the study focused more on fandom than consumer

knowledge. Thus, there is an opportunity for more

empirical research in this area, as well.

From a practitioner’s perspective, the results related

to time and advanced purchases are essential especially

with the supreme importance of advanced sales for

revenue management (Hendrickson, 2012). There are

practical considerations related to time and market

segmentation. Target markets are typically segmented

based on simple descriptors such as gender, age, geog-

raphy, and frequency of purchase. However, one the

most unique features of DTP is that it allows the seller

to consider changes in consumer demand over time. In

previous research, time has been an important factor

in predicting final sale prices (Drayer & Shapiro, 2009;

Moe et al., 2011). The results of the current study indi-

cate that, similar to the tourism and hospitality indus-

tries, sport marketers may be able to segment

consumers based on time. The findings of the current

study suggest that greater uncertainty exists the further

back the ticket sales pitch occurs. Sport marketers may

be able to capitalize on this sense of urgency and con-

tinue to push customers to purchase tickets well in

advance of an event.

Interestingly, Drayer and Shapiro (2009) found that

secondary market prices in an auction environment

(where consumers determined the ultimate sale price)

tended to decline over time. Further, Drayer, Shapiro,

and Lee (2012) suggested that consumers who were

educated about DTP might ultimately be able to

manipulate the market by waiting for prices to fall over

time. In this case, sport properties can be reassured that

there still exists a sense of urgency over time. Although

this phenomenon is still in need of further examina-

tion, DTP creates an opportunity for sport marketers to

segment consumers based on time. Shapiro and Drayer

(2012) found the dynamic ticket prices in the primary

market slowly increased over time. While sport organi-

zations may do this in order to protect the integrity of

their ticket prices and encourage advanced sales, this

strategy may ignore consumers’ expected evaluation of

the ticket market over time. Ultimately, sport marketers

must continue to balance traditional pricing strategies

with an understanding of consumer response to specific

pricing stimuli.

Limitations & Future Research

While the study was grounded in sound theory, it was

essentially an exploratory study within the field of

sport. As a result, the findings only compare differ-

ences in consumer estimation at specific points in

time. It does not, however, explain how or why these

patterns formed. As indicated, more research is needed

examining time as a variable within sport consumer

decision making. For instance, as suggested by Chen

and Schwartz (2008a), more research within the final

21 days before the event may be beneficial. The current

study only examined three distinct points within this

period, but perhaps a less restrictive investigation of

several points or perhaps even all points of time

between day 21 and game day would provide addition-

al insight about this volatile segment of time.

Another potential limitation of this study was the

context of professional hockey. While still considered a

mainstream sport by many, it is obviously less popular

176 Volume 22 • Number 3 • 2013 • Sport Marketing Quarterly

than the National Football League, the National

Basketball Association, and Major League Baseball, to

the average consumer. The population selection of

general Philadelphia area sports fans as opposed to

only Flyers or even only hockey enthusiasts helps the

study’s generalizability, but it also makes it hard to

assess the impact of the context on the variables under

examination. For instance, would the results differ

from an investigation of another league? In addition,

the researchers selected a Saturday evening game late

in the season against a somewhat premium opponent

(Montreal Canadiens). How much did these specifics

of the game impact the results? The study also included

real-life, time-specific details in the scenarios provided

to the participants in an attempt to create a quasi-

experimental research setting. As a result, several con-

straints could have limited a participant’s interest in

attending the Flyers game. For example, participants

may have already had plans for the weekend or per-

haps even already had tickets to the game.

Along the same line, there is a need in the field for

additional longitudinal studies on sport consumers.

Too often, a cross section of individual attitudes and

behaviors are studied with respect to a given phenome-

non. However, as this study shows, consumers are

dynamic and fluid. Thoughts and actions change over

time, and while methods (as employed in this study)

accounting for the influence of time may require more

work upfront, the potential for more impactful results

subsist.

Lastly, as mentioned throughout the discussion sec-

tion, several possible extensions of this study exist for

future examination. For instance, a closer look at how

and why participants believed ticket prices would

decrease, yet availability would increase as time before

the event decreased is a logical follow-up. In addition,

inquiry related to team identification and other forms

of consumer knowledge would be an enticing exten-

sion. Investigating other sport-related factors that are

likely to interact with time within the advanced-pur-

chasing process would also be fruitful. For example,

stadium location, team and opponent quality, or even

number of seats needed could interact with the time

variable. Consumer familiarity with both primary and

secondary markets in conjunction with time, perceived

fairness, and perceived value would also be an interest-

ing line of research. In all, the examination these dis-

tinct attitudinal patterns over time is of great

importance to the field, as they may provide a more

clear understand of consumer behavior in an

advanced-purchasing setting.

References

Borland, J., & MacDonald, R. (2003). Demand for sport. Oxford Review of

Economic Policy, 19, 478-502.

Branscombe, N. R., & Wann, D. L. (1991). The positive social and self con-

cept consequences of sports team identification. Journal of Sport and

Social Issues, 15, 115-127.

Carter, C. (2012, July 8). Understanding sports ticket prices on the second-

ary market. Ticket News. Retrieved from

http://www.ticketnews.com/news/understanding-sports-ticket-prices-

on-the-secondary-market071208568

Chen, C. C., & Schwartz, Z. (2008a). Room rate patterns and customers’

propensity to book a hotel room. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism

Research, 32, 287-306.

Chen, C. C., & Schwartz, Z. (2008b). Timing matters: Travelers’ advanced-

booking expectations and decisions. Journal of Travel Research, 47, 35-42.

Choi, S., & Mattila, A. S. (2005). Impact of information on customer fair-

ness perceptions of hotel revenue management. Cornell Hotel and

Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 46, 27-35.

Coates, D., & Humphreys, B. (2007). Ticket prices, concessions and atten-

dance at professional sporting events. International Journal of Sport

Finance, 2, 161-170.

Drayer, J., & Martin, N. T. (2010). Establishing legitimacy in the secondary

ticket market: A case study of an NFL market. Sport Management

Review, 13, 39-49.

Drayer, J., & Shapiro, S. L. (2009). Value determination in the secondary

ticket market: A quantitative analysis of the NFL playoffs. Sport

Marketing Quarterly, 18, 5-13.

Drayer, J., & Shapiro, S. L. (2011). An examination into the factors that

influence consumers’ perceptions of value. Sport Management Review,

14, 389-398.

Drayer, J., Shapiro, S. L., & Lee, S. (2012). Dynamic ticket pricing in sport: An

agenda for research and practice. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 21, 184-194.

Fink, S., Trail, G., & Anderson, D. (2002). An examination of team identifi-

cation: Which motives are most salient to its existence? International

Sports Journal, 6, 195-207.

Fisher, E. (2010, May 17). MLB teams hang hopes on walk up, single game

sales. Street and Smith’s SportsBusiness Journal. Retrieved from

http://www.sportsbusinessdaily.com/ Journal/Issues/2010/05/20100517/

Fort, R. (2004). Inelastic sports pricing. Managerial and Decision Economics,

25, 87-94.

Gale, I. L., & Holmes, T. J. (1992). The efficiency of advance-purchase dis-

counts in the presence of aggregate demand uncertainty. International

Journal of Industrial Organization, 10, 413-437.

Garcia, J., & Rodriguez, P. (2002). The determinants of football match

attendance revisited: Empirical evidence from the Spanish Football

League. Journal of Sports Economics, 3, 18-38.

Gibson, H. J. (1998). Sport tourism: A critical analysis of research. Sport

Management Review, 1, 45-76.

Hansen, H., & Gauthier, R. (1989). Factors affecting attendance at profes-

sional sporting events. Journal of Sport Management, 3, 115-32.

Hendrickson, H. (2012). View from the field: Business intelligence in the

sports world. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 21, 136-137.

Howard, D. R., & Crompton, J.L. (2004). Tactics used by sports organiza-

tions in the United States to increase ticket sales. Managing Leisure, 9,

87-95.

Kimes, S. E. (2003). Revenue management: A retrospective. Cornell Hotel

and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 44(5-6), 131-138.

Koo, G., & Hardin, R. (2008). Difference in interrelationship between spec-

tators’ motives and behavioral intentions based on emotional attach-

ment. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 17, 30-43.

Krautmann, A. C. & Berri, S. B. (2007). Can we find it at the concessions?

Understanding price elasticity in professional sports. Journal of Sports

Economics, 8, 183-191.

Lemke, R. J., Leonard, M., & Tlhokwane, K. (2010). Estimating attendance

at Major League Baseball games for the 2007 season. Journal of Sports

Economics, 11, 316-348.

Volume 22 • Number 3 • 2013 • Sport Marketing Quarterly 177

Lock, D., Taylor, T., Funk, D., & Darcy, S. (2012). Exploring the develop-

ment of team identification. Journal of Sport Management, 26, 283-294.

Moe, W. W., Fader, P. S., & Kahn, B. (2011). Buying tickets: Capturing the

dynamic factors that drive consumer purchase decision for sporting

events. Presentation at the MIT Sloan Sports Analytics Conference.

Noll, R. (1974). Attendance and price setting. In R. Noll (Ed.), Government

and the sports business. Washington DC: Brookings Institute.

Price, D., & Sen, K. (2003). The demand for game day attendance in college

football: An analysis of the 1997 Division 1-A season. Managerial and

Decision Economics, 24, 35-46.

Schwartz, Z. (2000). Changes in hotel guests’ willingness to pay as the date of

stay draws closer. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 24, 180-98.

Schwartz, Z. (2006). Advanced booking and revenue management: Room

rates and the consumers’ strategic zones. International Journal of

Hospitality Management, 25, 447-462.

Schwartz, Z. (2008). Time, price and advanced booking of hotel rooms.

International Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Administration, 8, 128-146.

Shapiro, S. L., & Drayer, J. (2012). A new age of demand-based pricing: An

examination of dynamic ticket pricing and secondary market prices in

Major League Baseball. Journal of Sport Management, 26, 532-546.

Shugan, S. M., & Xie, J. (2000). Advance pricing of services and other

implications of separating purchase and consumption. Journal of Service

Research, 2, 227-239.

Shugan, S. M., & Xie, J. (2005). Advance-selling as a competitive marketing

tool. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 22, 351-373.

Stryker, S. (1968). Identity salience and role performance: The relevance of

symbolic interaction theory for family research. Journal of Marriage and

the Family, 30, 558-564.

Stryker, S. (1980). Symbolic interactionism: A socio-structural version. Menlo

Park, CA: Benjamin/Cummings.

Stryker, S., & Burke, P. J. (2000). The past, present, and future of identity

theory. Social Psychology Quarterly, 63, 284-297.

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2007). Using multivariate statistics (5

th

ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson Education.

Trail, G. T., Anderson, D. F., & Fink. J. S. (2000). A theoretical model of

sport spectator consumption behavior. International Journal of Sport

Management, 1, 154-180.

Trail, G. T., Fink, J. S., & Anderson, D. F. (2003). Sport spectator consump-

tion behavior. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 12, 8-17.

Trail, G. T., Kim, Y. K., Kwon, H. H., Harrolle, M. G., Braunstein-Minkove,

J. R., & Dick, R. (2012). The effects of vicarious achievement on

BIRGing and CORFing: Testing the moderating and mediating effects of

team identification. Sport Management Review, 15, 345-354.

Trail, G. T., Robinson, M. J., Dick, R. J., & Gillentine, A. J. (2003). Motives

and points of attachment: Fans versus spectators in intercollegiate ath-

letics. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 12, 217-227.

Wakefield, K. L. (1995). The pervasive effects of social influence on sporting

event attendance. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 19, 335-351.

Wann, D. L., & Branscombe, N. R. (1995). Influence of identification with a

sports team on objective knowledge and subjective beliefs. International

Journal of Sport Psychology, 26, 551-567.

Wann, D. L., & Branscombe, N. R. (1993). Sports fans: Measuring degree of

identification with their team. International Journal of Sport Psychology,

24, 1-17.

Whitney, J. D. (1988). Winning games versus winning championships: The

economics of fan interest and team performance. Economic Inquiry, 26,

703-724.

Xia, L., Monroe, K. B, & Cox, J. L. (2004). The price is unfair! A conceptual

framework of price fairness perceptions. Journal of Marketing, 68, 1-15.

Xie, J., & Shugan, S. M. (2001). Electronic tickets, smart cards, and online

prepayments: When and how to advance sell. Marketing Science, 20,

219-243.

Welki, A. M., & Zlatoper, T. J. (1994). US professional football: The

demand for game-day attendance in 1991. Managerial and Decision

Economics, 15, 489-495.

Wirtz, J., & Kimes, S. E. (2007). The moderating role of familiarity in fair-

ness perceptions of revenue management pricing. Journal of Service

Research, 9(3), 229-240.

Zillman, D., Bryant, J., & Sapolsky, B.S. (1989). Enjoyment from sports

spectatorship. In J. D. Goldstein (Ed.), Sports, games, and play: Social

and psychosocial viewpoints (2

nd

ed., pp. 241-278), Hillsdale, NJ:

Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

178 Volume 22 • Number 3 • 2013 • Sport Marketing Quarterly

Appendix

Flyers.com Scenario

Consider the following scenario: a good friend suggested going to a Philadelphia Flyers game on Saturday, March

24th, 2012 (7 p.m.) where the Flyers play the Montreal Canadiens. You went directly to the Flyers’ website

(www.flyers.nhl.com) and found two tickets in the middle of section 102 (see Seating Chart and View from the

Section) for $165 each.

Please answer the following questions after carefully considering all of the facts outlined in this scenario.

I believe the chance the same or very similar tickets will be available between tomorrow (DATE) and

Saturday, March 24th is _______%. (Please indicate a number between 0 and 100).

I believe the chance that I could find the same or very similar tickets somewhere else at a price lower than

$165 each between tomorrow (DATE) and Saturday, March 24th is _______%. (Please indicate a number

between 0 and 100).

Volume 22 • Number 3 • 2013 • Sport Marketing Quarterly 179

RT

StubHub.com Scenario

Consider the following scenario: a good friend suggested going to a Philadelphia Flyers game on Saturday, March

24th, 2012 (7 p.m.) where the Flyers play the Montreal Canadiens. You went directly to the StubHub website

(www.stubhub.com) and found two tickets in the middle of section 102 (see Seating Chart and View from the

Section) for $165 each.

Please answer the following questions after carefully considering all of the facts outlined in this scenario.

I believe the chance the same or very similar tickets will be available between tomorrow (DATE) and

Saturday, March 24th is _______%. (Please indicate a number between 0 and 100).

I believe the chance that I could find the same or very similar tickets somewhere else at a price lower than

$165 each between tomorrow (DATE) and Saturday, March 24th is _______%. (Please indicate a number

between 0 and 100).

180 Volume 22 • Number 3 • 2013 • Sport Marketing Quarterly

EL

RGOCE

TE

-

GC

RT