Canada’s Health Crisis:

Profiling Opioid Addiction in Alberta & British Columbia

Report for the Stanford Network on Addiction Policy (SNAP) by:

Blair Gibbs

Ryan Workman

Jake Kiefer

Chosen Canlas

March 2023

1

Background

This project was commissioned by Professor Keith Humphreys of Stanford University and was funded through the

Stanford Network on Addiction Policy (SNAP).

Purpose of Study

The purpose of this report is to investigate the current state of the opioid addiction crisis in Canada. The report gives

specific attention to Alberta and British Columbia, the two provinces in Canada with the highest rates of opioid-related

overdose deaths. The report seeks to identify drivers of the crisis and key features of the provincial policies, along with the

makeup of the addicted populations and overdose victims.

Methodology

This report utilized publicly available data at both the federal and provincial level applying both quantitative and qualitative

research methods. All data was retrieved between September 2022 and February 2023. Access to certain datasets was

refused in the absence of an ethics approval.

2

Executive Summary

Canada’s drug addiction crisis has been mounting for two decades, and shares many of the same features as the

well documented experience of the United States. In both countries, the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the health

harms, with rates of drug mortality in areas like British Columbia (BC) in 2022 as high as the worst affected parts of the

USA.

There is more political attention on the issue compared to a decade ago, but a situation that warranted a

declaration of a public health emergency in BC in 2016 has not improved since then – in fact the crisis has

escalated. As of December 31, 2022, the rate of illicit drug toxicity deaths in BC has more than doubled since the

emergency was first declared in 2016.

This report explores what is behind this dramatic deterioration and focuses on the characteristics of the crisis in

British Columbia and Alberta – two neighbouring provinces in Western Canada that are home to a disproportionate

share of the harm caused by opioid addiction today.

Key Findings

Canada’s addiction crisis in context

• The scale of drug-related harms in Canada are significant, dramatically outpacing comparator jurisdictions in

places like Europe. The death rate in Canada’s worst affected province – British Columbia – has risen from 5.8 per

100,000 in 2000 to 44.2 per 100,000 in 2021. In Canada, the number of accidental apparent opioid toxicity deaths

(AAOTDs) per 100,000 was 20.2 per 100,000 in 2021. For comparison, in 2019, England and Wales had a drug-

related mortality rate of 7.7 per 100,000.

• BC’s AAOTD rate in 2021 was more than double the national average, and Alberta was not far behind at 36 per

100,000. Ontario had the most total AAOTDs (2,772) but had a lower death rate of 19.4 per 100,000.

• Between them, BC and Alberta accounted for a quarter of Canada’s population but almost half (49%) of drug

deaths (3,804). To put this another way, 1 in every 7 Canadians live in BC and 1 in every 9 live in Alberta, but 1 in

3

every 4 AAOTD in 2021 was a British Columbian and 1 in every 5 was an Albertan. The share of AAOTDs held by

Alberta and BC has actually decreased slightly from 54% in 2016.

• In Canada overall, in 2020 and 2021, opioids caused nearly half as many deaths (13,815) as COVID-19 over the

same period (29,985), and were responsible for five times the number of lost life years. The COVID-19 pandemic

caused approximately 90,000 lost years of life in 2020 and 2021. Over that same period, premature deaths from

opioids caused nearly 450,000 lost years of life. The crisis has gotten so severe that it halted the increase in Canadian

life expectancy between 2016 and 2017, the first time that Canadian life expectancy has decreased in over four

decades.

• Opioid addiction is now at a scale that makes it a general public health concern. Alcohol and tobacco kill more

Canadians than illicit drugs, however those who overdose on opioids are usually far younger than those who die of

alcohol or tobacco. Because the chronic health impacts of alcohol or tobacco consumption manifest over decades of

use, opioids are responsible for more life years lost than tobacco, and nearly as many life years lost as alcohol, despite

not having the same level of general use in the population.

Opioid addiction in Canada

There are many dimensions to opioid-related-harms, but this report focuses on deaths, hospitalizations, lost life years, and

drug-related crime. Key findings regarding opioid-related harms include:

• Although illicit drug use often begins in adolescence or young adulthood, the people most impacted by

AAOTDs in Canada are those aged between 30 and 49. In 2021, middle-aged Canadians aged 30-49 represented

27% of the population and over half (52%) of all AAOTDs. Two other cohorts – 20-29-year-olds and 50-59-year-olds –

together represent 26% of the population and 38% of AAOTDs.

• The impact of opioid addiction is not evenly spread, and the concentration is significant. Geographically, the

harms are concentrated in Alberta and BC, and there is a disproportionate impact according to age and sex. Over half

of those suffering from opioid harms in Canada are 30-59-year-old men, though in BC the most impacted group is 50-

59-year-old-men.

• Indigenous people in Canada are also over-represented in terms of opioid harms. In Alberta, First Nations

individuals were dying at a rate nearly 7 times that of non-first nations in the first six months of 2020. In BC, between

January and June 2021, 14% of overdose deaths were among First Nations peoples despite them representing only

4

3.3% of the population. First Nations people had an illicit drug-related death rate 4.8 times greater than other BC

residents in 2021.

• Low income and lack of employment were also key drivers of opioid harms. The BC Coroners Service found that

only 35% of those who suffered illicit drug toxicity deaths between August 2017 and July 2021 were employed at the

time of their death. Data for BC shows income levels were also correlated with opioid-related mortality and

hospitalization, with those in the lowest quintile being 3.8 times more likely to suffer opioid-related mortality and 4.3

times more likely to be hospitalized for opioid-related reasons.

• Drug addiction often compounds other health issues, with poor mental health a common aggravating factor. In

BC, between August 2017 and July 2021, 62% of people who died of illicit drugs were experiencing mental health

issues. Those who die have often been in contact with the health system. Decedents had a higher number of health

visits, and 30% had had a previous paramedic attended non-fatal illicit drug related event.

Key drivers of drug deaths

Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid that can be up to 50 times stronger than heroin and 100 times stronger than morphine, but it

was not a feature of the drug market even 10 years ago. Fentanyl and its analogues have played an important role in the

opioid crisis because they are significantly cheaper to produce per dose and much harder to detect illicit supply routes.

This makes them more widespread in illicit drug markets and harder for law enforcement to trace and detect, and it is also

more likely that a dose will be too potent and cause people who use these drugs to overdose:

• The single factor that best explained the distribution of drug harms in Canada, based on published data, was

the prevalence of fentanyl. Though the populations of drug users were highest in Alberta and BC, the difference was

not substantial enough to explain why these provinces have approximately double the rate of deaths than Canada as a

whole, and eight times the AAOTD rate compared to jurisdictions such as Quebec and Newfoundland.

• Fentanyl was detected much more frequently in samples seized by law enforcement in Western Canada than in

Eastern Canada. Based on data from Health Canada’s Drug Analysis Service (DAS), this indicates a preponderance

for more toxic drug supply in these provinces, and marked correlations in other parts of Canada.

• In Alberta, in 2021, fentanyl was detected in 81% of all accidental drug poisoning deaths. In BC between 2019 and

2022, fentanyl was detected in 85% of all illicit overdose deaths. Further, fentanyl detection in BC has risen in tandem

with the death rate.

5

• Increased harms are not the result of an increase in the user base for illicit drugs. When considered alongside

survey data on self-reported drug use, it appears the increase in opioid-related harms in Canada is being driven by the

increased toxicity of the supply, rather than an increase in the number of drug users in the general population.

Other possible drivers of the higher rates of drug harm in Alberta and BC not considered in detail for this report include

access to treatment and rates of attrition in recovery services; inward migration of drug users; income and socio-economic

inequality; distribution of ethnicities within provinces; housing access and stability; and prescribing and dispensing

practice.

Drug crime in Canada

Crime associated with illicit drug markets is a further cause of harm to communities. Compared to twenty years ago, the

emphasis in Canada has shifted away from punishing users and sanctioning possession to deter drug use. However, as in

the USA, the fentanyl causing overdoses in Canada are supplied by an illegal market where addicted drug users are

exploited by organised crime and their international suppliers, who are still subject to serious penalties when they are

caught and prosecuted. The current state of this activity is hard to gauge, but our research found:

• Enforcement against drug crime has reduced in recent years. For Canada overall, sentencing volumes for drug-

related crime have dropped by over 50% in the past decade. Convictions for crime overall in Canada have also

dropped, but not to nearly the same extent, indicating a general lessening of criminal justice enforcement against drug

offences in Canada during the escalating health crisis of opioid addiction.

• The majority of reported opioid-related offences occur in BC. In 2021, BC – comprising approximately 13% of

Canada’s population – had nearly half of all police-reported opioid trafficking, production, and distribution (TPD)

incidents in Canada (drug offences that do not encompass personal possession). BC’s rate of opioid-related police

recorded incidents in 2021 was more than four times the recorded incident rate in Alberta.

• Despite the high volume of drug violations in BC, criminal charges for these offences are low, and appear

disconnected from incident rates. By contrast, charges for serious drug-related crimes are much higher in Alberta,

and increases in charges broadly tracked the trend in incidents, with rising rates after 2012 and reductions more

recently.

• In BC, drug possession incidents have increased significantly in the last decade, and TPD incidences have also

increased after 2016, but charge rates for both categories have remained broadly flat or even fallen over the same

period, suggesting a lack of interest by law enforcement in traditional prosecution for these offences.

6

• Crime incident data confirms BC is the epicentre of drug-crime in Canada, reporting 57 opioid-related incidents

per 100,000 population, compared to 13 per 100,000 in Alberta. Vancouver also has much higher numbers of drug-

related violations than anywhere else, and significantly higher than large cities like Calgary or Edmonton.

• In BC, drug users caught in possession have not been routinely charged by police in recent years,

foreshadowing the formal decriminalisation of drug possession in BC that came into effect on 31 January 2023.

However, this does not seem to reflect a law enforcement focus on upstream interdiction instead. When considering

the more serious drug offences involved in supply and profiting from the illicit market, the gap between TPD incidents

and charges in BC, however, is significant (80 per 100,000 incidents vs. 22 per 100,000 charges in 2019). In contrast,

Alberta charges far more people for TPD relative to the incidents detected (46.6 per 100,000 incidents vs. 38 per

100,000 charges).

Provincial comparison

Drug addiction affects every community but there is also a geographic concentration in western Canada. For more than a

decade, Alberta and BC have been Canada’s opioid hotspots, but there are some differences in how the crisis has

presented in the two provinces.

• British Columbia has a much longer history with substance harms than Alberta, and volume of harm is much

higher in BC, measured according to deaths and hospitalisations. However, the rise in AAOTDs in Alberta during

the pandemic has been steeper relative to its pre-pandemic levels.

• BC’s opioid addiction crisis skews older and more male – for reasons that have not been closely studied. On

age, Alberta is similar to the Canadian average, with 30-49-year-olds representing 30% of the population and 54% of

deaths. Those dying in BC, however, tend to be older: 50–59-year-olds represented only 13% of the province’s

population in 2021, but account for 28% of all AAOTD deaths.

• The ratio of male to female deaths in Alberta was in line with national averages, but was more acute in BC,

where 80% of all AAOTDs in 2021 were men. This could indicate that the resident base of drug users in BC – which

itself may explain the elevated number of deaths there - is being supplemented by inward migration from other

provinces.

• The impact on emergency dispatch caseloads from the addiction crisis is much higher in BC. Looking at

ambulance data, Emergency Medical Service (EMS) responses to suspected opioid-related overdoses are highest in

BC (24,152 responses) – three times the volume of such incidents in Alberta (8,215 responses).

7

Policy Responses in Western Canada

Strategies and municipal initiatives have been launched to addressed the crisis, beginning with the landmark ‘Four Pillars’

strategy published by the City of Vancouver in 2000. Major funding commitments have been made by the provincial

governments; however, the addiction crisis continues in both provinces, with 2022 being the second-deadliest year ever

for drug harms in both jurisdictions.

Both Alberta and BC deploy elements of harm reduction along with recovery. This report found that there was a significant

degree of overlap between the policy approaches and services provided by the two provinces, however the policy framing

and direction are not the same:

• Both provinces support harm reduction activity such as Naloxone distribution to emergency services and

community providers. In recent years, there has been a dramatic upswing in naloxone kit distribution in Alberta

where in 2022 there was approximately 135,330 kits distributed compared to only 32,140 in 2017, and 6,181 in 2016.

In BC, over one million naloxone kits were distributed between 2012 and 2021.

• Both provinces also fund and permit syringe exchange programs, and supervised consumption sites (SCS) in

multiple locations, with Vancouver being the location for the first such facility that opened in 2003.

However, there are some notable differences between Alberta and British Columbia:

• The provincial government and health providers in BC have placed a stronger emphasis on harm reduction,

with ‘safe supply’ for users of illicit drugs, and the recent decriminalization of drug possession, approved by the Federal

Government, in order to further reduce stigma and protect drug users from enforcement.

• Alberta has weighted their response more towards investment in rehabilitation beds and spaces, such as

therapeutic communities. Alberta has also not adopted the models of ‘safe supply’ – including proposals for

automated dispensing – that have been setup in BC. In addition to investments in treatment and new community

dispensing of licensed medicines like Sublocade, the province has also committed capital to building new recovery

communities.

• Published data implies that there is more residential recovery bed provision in Alberta than BC today, but

comparisons are hampered by a lack of consistent recording. It is currently not possible to compare the two provinces

on the politically salient issue of treatment and recovery outcomes based on the available data.

8

• The most apparent difference in policy between the provinces is BC’s recent decriminalisation of substance

possession. Alberta, while, bolstering funding and support around its recovery model, is maintaining current

approaches to law enforcement around illicit drugs.

• Enforcement appears to be a more integral part of the response in Alberta, although the province has also seen a

reduction in its incident caseload. The ratio of serious drug incidents to charges was nearly 1:1 in Alberta, compared to

BC where the ratio of incidents to charges was about 4:1.

There is a lack of policy innovation in BC on the issue of drug addiction, although a growing political interest in finding

sustainable solutions. Alberta’s nascent ‘Recovery-oriented System of Care’ model has new investment and political

leadership but has not yet had time to fully deliver results, with recovery communities still being constructed.

As the implementation of these neighbouring strategies advances, ongoing scrutiny of their impacts and effectiveness is

required to inform policymakers across Canada and other jurisdictions. Close engagement between policymakers and

service leads in both provinces will be important to allow sharing of learnings, especially in those areas where provincial

practices begin to diverge.

Headline conclusions

Despite the urgency of this crisis, and the many years to make the necessary investments, some basic information

architecture is still not in place to support policymakers or to guide those practitioners on the ground working to help

users suffering from drug addiction. This means that the impact of many policies in Canada to reduce harms and to aid

recovery cannot be properly evaluated.

Canada’s experience could provide lessons to other countries like the USA, but only if governments at all levels

commit to a consistent suite of reporting measures that accurately describes the progress being made, and one that

counts more than caseloads, inputs, or a series of ‘harm’ metrics.

Given the significant public funds that continue to be spent, it is time for provincial and federal policymakers to

urgently agree upon what success looks like and how it will be measured. In the absence of robust metrics around

treatment and pathways for recovery, the ‘harm’ metrics around deaths and hospitalisation become the only marker of

policy progress.

9

Of the two provinces studied for this report, Alberta is currently experiencing a reduction in key addiction-related

harms; however, it is based on two quarters of data, and would need to be sustained through 2023 to represent an

established trend. Our research indicates that Canada overall, and BC in particular, is not yet showing the progress that

the public and those impacted by drug addiction deserve.

Widespread public concern about this challenge is likely to continue and as death rates remain high, more

transparency, innovation and new policy responses are therefore needed. The current political attention on how two

provinces are choosing to respond to the opioid addiction crisis provides a window of opportunity to embrace new

solutions with focused political leadership in order to finally see Canada’s harmful trends around opioid addiction

reversed.

10

Contents

Background ......................................................................................................................................................................... 1

Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................................................. 2

Contents ............................................................................................................................................................................. 10

Foreword ............................................................................................................................................................................ 14

Introduction ....................................................................................................................................................................... 17

CHAPTER 1: Defining the Problem ................................................................................................................................... 21

Opioids: their function and role ....................................................................................................................................................... 21

Benefits and Harms........................................................................................................................................................................... 22

Risk and Context ............................................................................................................................................................................... 23

CHAPTER 2: History of Canada’s health crisis ................................................................................................................ 26

Overview ............................................................................................................................................................................................. 26

Wave 1 (1980s – 2010) .................................................................................................................................................................... 27

Wave 2 (2010 – 2014) ...................................................................................................................................................................... 27

Wave 3 (2014-2019) ......................................................................................................................................................................... 28

Wave 4 (2020 – Present) .................................................................................................................................................................. 29

What Comes Next? ........................................................................................................................................................................... 29

CHAPTER 3: Data ............................................................................................................................................................... 30

Deaths, Hospitalizations and EMS .................................................................................................................................................. 30

Population of People who Use Illegal Substances in Canada .................................................................................................... 31

Fentanyl and Overdose Deaths ....................................................................................................................................................... 33

Policing and Criminal Justice .......................................................................................................................................................... 34

11

Multi-Drug Use ................................................................................................................................................................................... 37

Risk Factors........................................................................................................................................................................................ 38

Sex ................................................................................................................................................................................................. 38

Age ................................................................................................................................................................................................. 39

Age and Sex ................................................................................................................................................................................. 40

Ethnicity ......................................................................................................................................................................................... 40

Employment and Socio-Economic Status ................................................................................................................................ 42

Location of Death and Household Characteristics ................................................................................................................. 43

Marital Status ................................................................................................................................................................................ 44

Area-Level Characteristics ......................................................................................................................................................... 44

Mental Health and Contact with Healthcare System .............................................................................................................. 44

Education ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 45

Summary: Canada, Alberta, BC ...................................................................................................................................................... 45

CHAPTER 4: Policies and Services in Alberta and British Columbia ............................................................................. 47

Provincial Contrast? .......................................................................................................................................................................... 47

Enforcement and Decriminalization ................................................................................................................................................ 47

‘Safer Supply’ and Harm Reduction ............................................................................................................................................... 48

Recovery ............................................................................................................................................................................................ 50

Services .............................................................................................................................................................................................. 50

Supervised Consumption Sites ................................................................................................................................................. 50

Rehabilitation ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 52

Naloxone ............................................................................................................................................................................................. 54

12

Opioid Agonist Treatment ................................................................................................................................................................ 55

Technology ........................................................................................................................................................................................ 56

Summary ............................................................................................................................................................................................ 57

CONCLUSIONS .................................................................................................................................................................. 58

Alberta and BC .................................................................................................................................................................................. 58

Policy Recommendations................................................................................................................................................................. 61

Bibliography ...................................................................................................................................................................... 63

Appendix A: Calculations for COVID-19 and Opioid Life Years Lost, 2020-2021 .......................................................... 72

COVID-19 ........................................................................................................................................................................................... 72

Opioids ................................................................................................................................................................................................ 73

Appendix B: Estimating Drug User Population based on CADs data ............................................................................. 74

Appendix C: Terminology for Different Indigenous Groups in Canada ......................................................................... 75

Appendix D: Drivers of the Opioid Crisis ......................................................................................................................... 76

Increased Toxicity ............................................................................................................................................................................. 78

Improved Product ............................................................................................................................................................................. 79

Policing and Enforcement ................................................................................................................................................................ 80

Prescribing and Dispensation ......................................................................................................................................................... 82

Technology ........................................................................................................................................................................................ 83

Point of Entry ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 84

Criminal Networks ............................................................................................................................................................................. 85

Immigration ........................................................................................................................................................................................ 86

Gender/Age ........................................................................................................................................................................................ 87

13

Income and Inequality ...................................................................................................................................................................... 88

Housing and Homelessness ............................................................................................................................................................ 89

Ethnicity .............................................................................................................................................................................................. 90

Marriage Rates .................................................................................................................................................................................. 91

Drug Culture and Stigma ................................................................................................................................................................. 92

Physical and Mental Health ............................................................................................................................................................. 93

Driver Summary ................................................................................................................................................................................ 94

14

Foreword

The United States and Canada continue to experience high rates of opioid-related mortality and other harms associated

with opioid and drug misuse. As neighbouring jurisdictions, these two countries have faced similar challenges in respect of

over-prescribing of opioids, and the problematic impact of new illicit substances in the community, such as fentanyl.

Canada’s opioid addiction crisis has been mounting for two decades, and the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the

health harms, with rates of drug mortality in areas like Greater Vancouver in 2022 as high as the worst affected parts of the

USA. Despite very different healthcare models, both countries have endured a level of adverse population impact from

drug addiction that has not been experienced in other developed nations.

Two decades ago, the City of Vancouver in British Columbia set out their four-pillar strategy (harm reduction, prevention,

treatment and enforcement) to address drug addiction and associated challenges, and the province has attempted to be a

leader in how it innovates to respond to the evolving crisis ever since. It was outside the scope of this project to evaluate

the efficacy of interventions over that period, but nonetheless a clear conclusion is that the collective impact of drug harms

has significantly increased since that comprehensive strategy was announced.

More recently, opioid addiction was declared a ‘public health emergency’ in BC in 2016, and although the nature of the

problem remains essentially unchanged, interventions since that time to address the challenge have not reduced the

societal impact in communities. Judged only by one key metric, the scale of the harms to individuals in BC has actually

grown significantly – with the number of deaths doubling by 2022 compared to when the emergency was first declared.

Drug policy failure doesn’t just harm people who use drugs. The collateral consequences are myriad, and include crime,

family violence and divorce, community disorder, degraded public spaces, lost business investment, and depressed tax

revenue. As such, the wider public is entitled to challenge public health and safety approaches that policymakers have

adopted if they appear to be limited in impact, or potentially exacerbating the problem.

A generalised commitment to ‘harm reduction’ predominates in Canada, and as such, key metrics are viewed more

narrowly as a collection of statistics referring to negative outcomes and harms experienced by individuals who use drugs.

This makes the wider societal impact of drug addiction and the harm reduction policies adopted in response to it, much

harder to track.

15

For example, the evidence base in criminology is clear that addiction drives much offending behaviour, and that a minority

of offenders are responsible for a disproportionate amount of crime, but rarely does research attempt to quantify the

public impact and cost of elevated crime levels associated with drug-addicted offenders or the continuation of addiction in

these populations.

A narrow focus on ‘harm’ to the individual user also provides no framework for measuring success in line with what the

relatives or friends of those suffering from drug addiction might want as an outcome for their own loved one – that is, to

escape addiction and to desist from behaviour that may lead to premature death.

There is an emerging perception in the media and public debate that the strategies adopted in Canada to address the

problem have not yielded sustained improvements across a range of key metrics. The result has been an increase in

public concern and political attention on the issue, and there is a renewed debate about the merits of different policy

responses in Canada.

In recent months, the salience of this issue has increased, with both BC and Alberta seeking to justify and promote their

respective approaches and their record to date. There is however an ongoing lack of good data on key outcomes and

even a consensus on what success would look like in this policy arena.

There is a general acceptance that the harms inflicted by drug misuse, combined with mental health and homelessness,

are ‘wicked’ problems requiring complex and multi-layered responses. In this respect, drug addiction and its

consequences are re-emerging as a key test of the effectiveness of evidence-based urban policymaking in cities across

North America. What can the situation in two of Canada’s worst affected provinces teach us?

The concentration of this crisis in Western Canada is clear, with BC and Alberta comprising half (49%) of all opioid-

overdose deaths in 2022. Below the provincial level, there is a further geographic concentration in major urban areas,

even if victims of opioid overdoses can be found in small towns and rural communities all across Canada. There is also a

strong perception that BC’s crisis is highly concentrated not just in one city (Vancouver), but in one neighbourhood of that

one city centre – the Downtown Eastside.

In Canada more generally, attention of politicians has tended to be dominated by a range of policy and legislative

responses focused on drug users – rather than drug markets or suppliers – that are intended to reduce infectious disease

acquisition, accidental deaths and overdoses. In addition, there has been new steps taken in recent months to further

16

reduce ‘stigma’, including the enactment of decriminalisation of drug possession in British Columbia. This is the first time

that anywhere in Canada has adopted an approach pioneered in just a few other jurisdictions, most famously by Portugal.

This research project, commissioned in Fall 2022, is designed to give an overview of the current drug addiction crisis in

Canada, with a special focus on two neighbouring provinces – British Columbia and Alberta – and to describe its key

features. The goal of the project was to outline the scale and nature of the drug harms affecting these two provinces, to

outline the policy approaches adopted by both provincial governments, and to explore the most likely drivers of the high

death and hospitalisation rates.

It was outside the scope of this report to evaluate the efficacy of different policy responses adopted by each province, or

to make recommendations for how policymakers in both places might respond. Our recommendations – outlined in the

Conclusion – are restricted to those that arise from the research undertaken and relate to how the response to the

challenge might be understood and evaluated more effectively in future.

In terms of years of productive life lost, the sheer scale of the drug addiction challenge makes it the most critical health

crisis for Canada. It demands a sober, non-ideological assessment of what policy responses are working, which

interventions are worth trialing, and how we should judge success when it comes to public policy around drug addiction.

This report provides a summary of where we begin in pursuing answers to those critical questions.

17

Introduction

Canada is in the midst of an opioid overdose crisis.

Though there is not reliable country-wide data on

overdose harms dating back further than 2016, British

Columbia’s death rate due to illicit drugs rose from 5.8

per 100,000 in 2000 to 44.2 per 100,000 in 2021.

1

This is

comparable to some of the worst affected states in the

US. In Canada, the number of accidental apparent opioid

toxicity deaths (AAOTDs) per 100,000 was 20.2 per

100,000 in 2021.

2

For comparison, in 2019, England and

Wales had a drug-related mortality rate of 7.7 per

100,000,

3

and in 2020 the European Union had a drug-

induced mortality rate of 1.5 per 100,000.

4

1

Illicit Drug Toxicity Deaths in BC: January 1, 2012—December 31,

2022. (2022). British Columbia Coroners Service.

2

Opioid- and stimulant-related harms. (2022). Government of

Canada.

* All countries other than Canada measure total drug-related mortality

Fig. 1. Data sourced from the BC Centers for Disease Control (2023), Office

of National Statistics (2020), Government of Canada (2022) and European

Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (2022).

3

Deaths related to drug poisoning in England and Wales. (2020).

Office for National Statistics.

4

Frequently asked questions (FAQ): Drug overdose deaths in

Europe. (2022). European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug

Addiction.

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

2000

2002

2004

2006

2008

2010

2012

2014

2016

2018

2020

Deaths per 100,000

Opioid Overdose Deaths* in Canada

compared to select jurisdictions

USA Canada European Union England and Wales

18

The only G7 country that has a similar rate of overdose

deaths is the United which had 25.4 drug overdose

deaths per 100,000 in 2020 (age-adjusted rate).

5

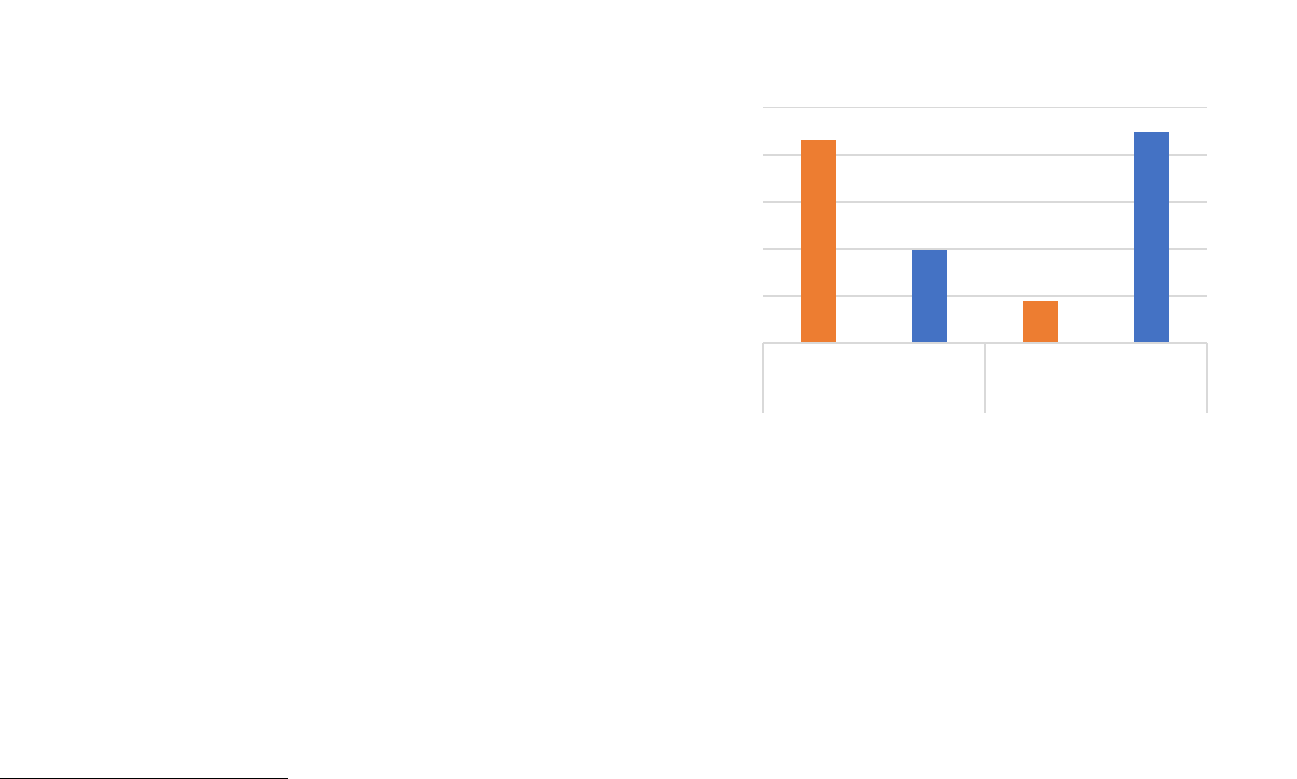

In 2020 and 2021, there were 13,815 deaths attributed to

accidental opioid poisoning in Canada.

6

This is almost half

the death toll that COVID-19 had over the same period

(29,985).

7

Considering the relative ages of those killed,

however, the opioid crisis has caused a far greater loss in

years of life. COVID-19 caused approximately 90,000 lost

years of life in 2020 and 2021.

8

Over that same period,

opioids caused nearly 450,000 lost years of life (see

appendix A).

9

5

CDC Wonder. (2023). CDC Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention.

6

Opioid- and stimulant-related harms. (2022). Government of

Canada.

7

COVID-19 daily epidemiology update. (2020). Public Health Agency

of Canada.

Fig. 2. Data sourced from Government of Canada (2022) and Public Health

Agency of Canada (2022).

The crisis has gotten so severe that it halted the increase

in Canadian life expectancy between 2016 and 2017, the

first time that Canadian life expectancy has decreased in

over four decades.

10

8

COVID-19 daily epidemiology update. (2020). Public Health Agency

of Canada.

9

Opioid- and stimulant-related harms. (2022). Government of

Canada.

10

Changes in life expectancy by selected causes of death, 2017.

(2019).

0

100,000

200,000

300,000

400,000

500,000

0

7,000

14,000

21,000

28,000

35,000

COVID-19 Opioids COVID-19 Opioids

Deaths Life Years Lost

Life-years lost - COVID-19 vs.

Accidental Opioid-Related Overdoses

19

32%

22%

46%

28%

21%

51%

Alberta and BC's Share of Canada's

AAOTDs, 2016 and 2021

BC Alberta Other Provinces and Territories

Addressing opioid addiction in BC and Alberta

Though opioid overdose deaths have been increasing

across the country, they have been most concentrated in

BC, Alberta, and Ontario. BC’s AAOTD rate in 2021 was

more than double the national average, and Alberta was

not far behind at 36 per 100,000. Ontario had the most

total AAOTDs (2,772) but had a lower death rate of 19.4

per 100,000. Between them, BC and Alberta accounted

for only 25% of the population but 49% of AATODs

(3,804). To put this another way, 1 in very 7 Canadians

live in BC and 1 in every 9 live in Alberta, but 1 in every 4

AAOTD in 2021 was a British Columbian and 1 in every 5

is an Albertan. The share of AAOTDs held by Alberta and

BC has actually decreased slightly from 54% in 2016.

11

In response to the crisis, both BC and Alberta have made

new investments in addiction services. BC’s 2021 budget

earmarked $0.5 billion for mental health and addiction

services over the next three years

12

and its 2023 budget

marked over a billion

13

, while Alberta’s 2022 budget

included $1 billion for addiction and mental health care

with an additional $60 million over three years to build a

recovery-oriented system of care.

14

11

Opioid- and stimulant-related harms. (2022). Government of

Canada.

12

Grochowski, S. (2021). B.C. announces historic half-billion-dollar

funding for overdose crisis, mental health. Maple Ridge - Pitt

Meadows News.

Fig. 3. Data sourced from Government of Canada (2022).

In recent months, certain policy differences between

Alberta and BC have become politically salient in Canada.

This report found there to be similarities between the two

provinces’ strategies, but also significant differences.

Both provinces support harm reduction activity such as

Naloxone distribution to emergency services and

community providers, syringe exchange programs, and

licenced overdose prevention provision (SCS) in multiple

locations to provide drug users with a safer, regulated

environment to consume. Each province has also shifted

away from police enforcement against drug possession

13

More than $1B announced for mental health, addictions support in

2023. (2023). CBC.

14

Toward an Alberta model of wellness. (2022). Government of

Alberta.

2016

2021

20

and towards diversion to treatment and education for

drug users.

BC’s approach places a stronger emphasis on stigma

reduction and decimalization, with a greater policy focus

on harm reduction, conceptualised as overdose

prevention and access to safer supply (i.e., prescribed

medical alternatives to toxic illegal drugs) including

through automated dispensing. In addition, BC has with

federal consent – as of 31 January 2023 – removed

criminal penalties for possession of illicit drugs.

15

Alberta,

in contrast is pursuing a ‘recovery-oriented system of

care’

16

and has emphasized the importance of community

support, treatment pathways, and more regulation over

and higher standards for SCS.

17

There also appears to be

a generally higher rate of enforcement against drug

trafficking, production, and distribution in Alberta,

although arrest rates for possession have dropped in both

provinces in the last decade.

Alberta and BC are relatively similar geographically and

culturally, are approximately equal in population, and the

factors driving their respective opioid crises seem

comparable. This makes them interesting neighbours for

a jurisdictional comparison; however, the difference in

policy approach is still developing. In time, the outcomes

achieved in AB and BC will provide an important

15

Judd, A., & Zussman, R. (2022, May 31). B.C. becomes first

province to remove criminal penalties for possession of some hard

drugs. Global News.

dimension to the political debate over the right response

to the problem Canada-wide. For now, it is too soon to

analyse the relative progress of each province as it

attempts to address opioid harms; nevertheless, this

report will draw attention to some key differences that

should be monitored going forward.

16

Toward an Alberta model of wellness. (2022). Government of

Alberta.

17

Impact: A Socio-Economic Review of Supervised Consumption

Sites in Alberta. (2020). Government of Alberta.

21

CHAPTER 1: Defining the Problem

In considering the current state of Canada’s opioid crisis,

for this chapter we summarise the role of opioids in

society, and how they may cause harms, either in

isolation, or in conjunction with other addictive

substances.

Opioids: their function and role

Opioids are a group of analgesic (pain relieving) drugs

commonly used in clinical practice. In addition to

providing pain relief, opioids trigger the release of

endorphins, reducing an individual’s perception of pain

and creating feelings of pleasure. Importantly, opioids

also slow multiple biological functions, including

breathing, which is why they can be fatal.

Opioids are used in both legal and illegal contexts. Legal

opioid use is restricted to medical contexts in Canada, as

it is in most countries, and a range of licensed medical

products contain opioids. Individuals may also use

opioids illegally for purposes of managing physical or

psychological pain or for the pleasurable affects of the

drug itself. People can also combine their use of

18

Felbab-Brown, V. (2020). Fentanyl and Geopolitics. Brookings

Institution.

19

Fentanyl Facts. (2022, February 23). Centers for Disease Control

and Prevention.

prescription opioids with other addictive substances or

opioids sourced from the illicit market.

Though certain opioids are primarily used in an illegal

context (e.g., heroin), for many types there is no chemical

difference between the substance being used in legal and

illegal contexts (e.g., fentanyl). Sometimes drugs may

even be sourced from the same production facilities.

18

Some types of opioids are more potent than others.

Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid that can be up to 50 times

stronger than heroin and 100 times stronger than

morphine.

19

Fentanyl and its analogues have played an

important role in the opioid crisis because they are

significantly cheaper to produce per dose. This makes

them more widespread in illicit drug markets, but it is also

more likely that a dose will be too potent and cause

people who use these drugs to overdose.

There are drugs in Canada that kill more people per year

than opioids. Purely in terms of deaths, the two most

lethal substances in the country are alcohol and

tobacco.

20

20

Canadian Substance Use Costs and Harms. (2020). Canadian

Centre on Substance Use and Addiction.

22

Fig. 4. Data sourced from Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction

(2020).

Nonetheless, those who overdose on opioids are usually

far younger than those who die of alcohol or tobacco,

because the chronic health impacts of alcohol or tobacco

consumption manifest over decades of use. Opioids are

responsible for more life years lost than tobacco, and

nearly as many life years lost as alcohol, despite not

having the same level of general use in the population.

21

21

Canadian Substance Use Costs and Harms. (2020). Canadian

Centre on Substance Use and Addiction.

* Productive Life Years lost defined as years lost before the age of 65

Fig. 5. Data sourced from Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction

(2020).

Benefits and Harms

Like many other drugs in modern society, opioids can be

both beneficial and harmful. They are a valuable tool for

the management of acute and chronic pain, and have

clear clinical efficacy and well-established prescribing

guidelines for use. At the same time, opioids are an

addictive substance, and rapid expansion of prescribing

by the medical profession occurred before some of the

0

10,000

20,000

30,000

40,000

50,000

60,000

2015 2016 2017 2015 2016 2017 2015 2016 2017

Alcohol Tobacco Opioids

Deaths by Substance Type, 2015-2017

0

20,000

40,000

60,000

80,000

100,000

120,000

2015 2016 2017 2015 2016 2017 2015 2016 2017

Alcohol Tobacco Opioids

Productive Life Years* Lost by

Substance Type, 2015-2017

23

risks of addiction were properly understood. When

someone takes opioids, their body can become

dependent, making it more challenging to desist, or to

reduce their use of the drug over time. Taking too strong

a dose can have immediate, negative health

consequences, up to and including death.

The policy debate about addiction is complicated by the

nature of the behaviour. Unlike most other illnesses or

adverse health conditions (e.g., cancer), opioid addiction

makes users complicit in their own injury, and unlike most

diseases, subjects do derive some enjoyment from the

use of opioids, which acts as a strong incentive to

continue using.

22

The debate over how to address drug addiction of all

kinds is a legitimate matter of public policy because of the

harms suffered by users, but also because of the wider

societal impact of the behaviour. Opioid use may not only

be harmful to the person themselves – impacting their

employability, housing, and relationships with dependents

– but can also cause harm to those around them. Friends

and family may struggle to help users manage their

addiction, addicts may resort to theft or fraud to sustain

their addiction, children may suffer neglect or separation,

and the broader public may suffer from the crime and

disorder impact of drug addicted populations, including

degradation of the public realm and drug paraphernalia

22

Humphreys, K. (2022). Testimony to the Oregon Senate

Committee on Judiciary and Ballot Measure 100 Implementation.

proliferating in parks or other public spaces. These

broader societal impacts can be exacerbated if drug

using populations are concentrated in certain urban

neighbourhoods where their behaviour is highly visible

and especially when combined with open drug markets

and street dealing of illicit drugs.

Risk and Context

Risk of harm from opioids is highly dependent on why

and how opioids are acquired. The safest context for

mitigating the risks associated with opioids is when they

are used for medical purposes for in-hospital treatment.

The patient does not have unsupervised access to

opioids, the opioids are unlikely to be diverted to an

unintended recipient, and the treatment is closely

monitored and is usually time-limited.

24

Risk contexts for opioid use

Fig. 6. Risk is an interaction between Why and How.

25

Despite being one of the largest consumers of opioids in

the world, Germany has relatively low overdose rates,

and this has been attributed to the fact that opioids are

primarily prescribed in-hospital and in other 24-hour care

settings.

23

Opioids prescribed by medical practitioners are also

relatively low risk. The majority of people who are

prescribed opioids use them for their intended purpose,

and benefit from the resulting pain relief; however, the

opioid crisis in the USA and Canada had its origins in the

over-prescribing of regulated opioid treatments. The

lower the threshold for opioid prescriptions, the greater

the risk for the recipient and those around them.

It is significantly riskier to use opioids for pleasure, even if

the opioids being used are prescription opioids. Like

many other substances (alcohol, cannabis, nicotine),

opioid use carries a number of potential health

implications, such as addiction, liver damage, and

overdoses. The risk of using opioids for pleasure goes up

considerably if the opioids are diverted from an intended

recipient or otherwise acquired via the illicit market or

other unregulated source, where dosage and purity are

not controlled or guaranteed. Self-medicating, either with

diverted prescriptions or illegally sourced substances, is

risky for these same reasons.

23

Felbab-Brown, K. H., Jonathan P. Caulkins, and Vanda. (2020).

What the US and Canada can learn from other countries to combat

the opioid crisis [Brookings].

26

CHAPTER 2: History of Canada’s Health Crisis

Overview

Canada’s opioid addiction crisis can be traced back two decades, and divides into four successive waves, each

representing a significant transition or evolution with an escalation of harms each time. The opioid crisis in the United

States has followed a similar trajectory, and has been included in the below table for comparison. Note that these phases

are a useful heuristic, rather than definitive and discrete categories.

Fig. 7. Data sourced from CDC Centers for Disease Control (2023), Government of Canada (2022), and BC Coroners Service (2022).

27

Wave 1 (1980s – 2010)

The reason that Canada and the USA have such

significant levels of opioid harms compared to other

countries has its origins in their relatively high

consumption of prescription opioids. Though

consumption has decreased in recent years, Canada was

once the second-largest consumer of opioids in the

world.

24

Currently, Canada is the fourth largest per-capita

consumer of controlled opioids, behind only Germany,

Iceland, and the USA.

25

This disproportionate consumption of opioids began as

far back as the 1980s, when opioid manufacturers began

campaigning for the increased utilization of opioids in

healthcare.

26

Since the 1980s, the volume of opioids sold

to hospitals and to pharmacies for prescription increased

by more than 3,000%.

27

As controlled opioid consumption

increased, so did the misuse of opioids. Patients either

used prescriptions for non-medical purposes, or

prescriptions were diverted from their intended

24

Lisa, B., & Jessica, H. (2018). Evidence synthesis - The opioid crisis

in Canada: A national perspective. Health Promotion and Chronic

Disease Prevention in Canada : Research, Policy and Practice, 38(6),

224–233.

25

Richards, G. C., Aronson, J. K., Mahtani, K. R., & Heneghan, C.

(2022). Global, regional, and national consumption of controlled

opioids: A cross-sectional study of 214 countries and non-

metropolitan territories. British Journal of Pain, 16(1), 34–40.

recipients. This was the first wave of the opioid crisis in

Canada and the USA.

It was during this period, in 2001, that Vancouver

implemented its four-pillar drug strategy of Prevention,

Treatment, Enforcement, and Harm Reduction, which

guided the approach in the early stages of what would

later become a much more serious public health crisis.

28

Wave 2 (2010 – 2014)

The first wave resulted in a large base of opioid users in

the general population, even if the majority were not

suffering from addiction or abusing other substances. The

second wave was characterized by the rise of

unregulated opioids from the illicit market, as dealers

responded to the demand for cheap and potent opioids

such as heroin and began to expand distribution.

This trend may have been encouraged by measures

taken by health authorities in Canada and the USA to limit

the supply of medical opioids and tackle over-prescribing

by some clinicians in an effort to reduce the number of

26

Meldrum, M. L. (2016). The Ongoing Opioid Prescription Epidemic:

Historical Context. American Journal of Public Health, 106(8), 1365–

1366.

27

Lisa, B., & Jessica, H. (2018). Evidence synthesis - The opioid crisis

in Canada: A national perspective. Health Promotion and Chronic

Disease Prevention in Canada : Research, Policy and Practice, 38(6),

224–233.

28

Framework for Action: A Four Pillar Approach to Vancouver’s Drug

Problems. (2001). City of Vancouver.

28

people becoming addicted. According to one source,

medical opioid consumption in Canada declined by

36.8% between 2009 and 2019.

29

Though this drop in

medical opioid consumption may have reduced the

number of people suffering addiction for the first time, it

may also have pushed existing dependent users to seek

out riskier alternatives. This likely consequence was

acknowledged at the time and became part of the policy

response to over-prescribing.

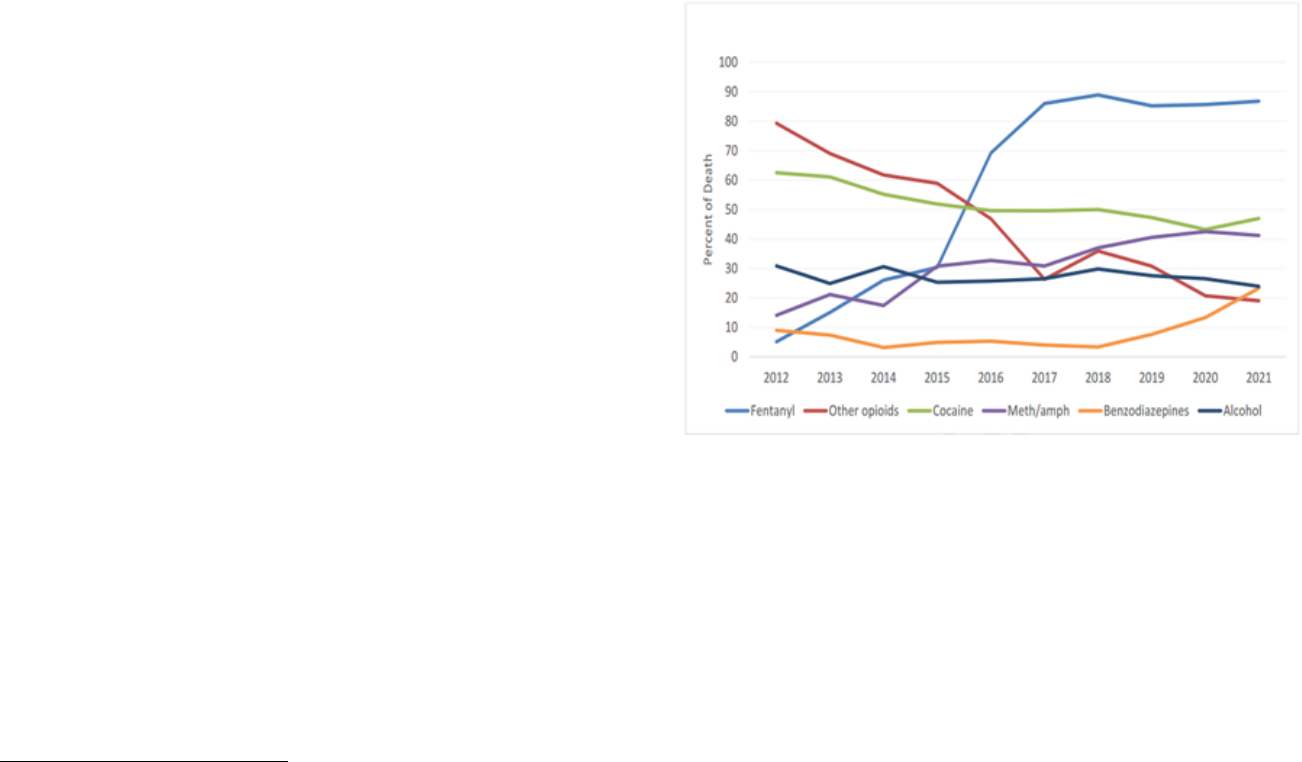

Wave 3 (2014-2019)

The second wave began transitioning into the third wave

as the toxicity of the drugs in the illegal market began to

increase, with deaths rising accordingly. In BC, in 2012,

fentanyl – at that time, the most potent opioid in

circulation – was detected in about 5% of all illicit drug

toxicity deaths. BC Coroners’ Service data shows the

rapid increase in subsequent years, with a sustained rise

in fentanyl detection among deaths over the past

decade).

30

When considered in tandem with the rise of deaths in BC

(see below) it is difficult to dispute that the increased

availability of fentanyl has resulted in a significant

increase in fentanyl consumption and fentanyl-related

29

Jayawardana, S., Forman, R., Johnston-Webber, C., Campbell, A.,

Berterame, S., Joncheere, C. de, Aitken, M., & Mossialos, E. (2021).

Global consumption of prescription opioid analgesics between 2009-

2019: A country-level observational study. EClinicalMedicine, 42.

deaths. More evidence regarding the role of fentanyl is

reviewed in section 4.

Fig. 8. Drug Types Relevant to Death, 2012-2021. From Illicit Drug Toxicity

Deaths in BC: January 1, 2012—October 31, 2022. (2022). British Columbia

Coroners Service.

It is unclear why deaths dropped between 2018 and

2019. One possibility is that use declined because supply

was restricted due to regulatory changes in China that

banned the production and sale of some types of fentanyl

without a license.

31

However, the decline in deaths would

soon reverse.

30

Illicit Drug Toxicity Deaths in BC: January 1, 2012—October 31,

2022. (2022). British Columbia Coroners Service.

31

Felbab-Brown, V. (2020). Fentanyl and Geopolitics. Brookings

Institution.

Drug Types Relevant to Death in BC, 2012-2021

29

It was in 2016 that the provincial government in BC

declared a state of medical emergency regarding drug

toxicity deaths, and greater political attention on the issue

and government funding began.

32

Wave 4 (2020 – Present)

With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of

AAOTDs in Canada began to increase again, reaching

their highest levels ever in 2021. The rise in AAOTDs

would have been caused by a confluence of factors, but

three of what are likely the most prominent drivers are

listed below.

First, social distancing and isolation would facilitate a

riskier environment for drug use. As will be discussed in

section 4, most AAOTDs happen while someone is alone

in a private residence.

Second, the stress of the pandemic caused increase drug

use. Surveys conducted by the Canadian Centre on

Substance Use found that drug users, particularly those

with a history of substance use disorder, reported

32

Provincial health officer declares public health emergency. (2016).

Government of British Columbia.

33

Mental Health and Substance Use During COVID-19. (2023).

Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction.

34

Moallef, S., DeBeck, K., Fairbairn, N., Cui, Z., Brar, R., Wilson, D.,

Johnson, C., Milloy, M.-J., & Hayashi, K. (2022). Inability to contact

increased stress and substance use with the onset of the

COVID-19 pandemic.

33

Third, some health and treatment services were more

difficult to access throughout the pandemic. For example,

one study found that many users had difficulty accessing

their prescriber to access Opioid Agonist Therapy (OAT)

medication.

34

What Comes Next?

Across Canada, AAOTDs have fallen from their record

2021 high, but not by much. Both BC and Alberta are

now making significant investments in tackling the crisis.

In the next section, we will review data on the current

state of the crisis in Canada overall, and then the two

worst affected provinces of Alberta and British Columbia.

opioid agonist therapy prescribers during the COVID-19 pandemic in

a Canadian setting: A cross-sectional analysis among people on

opioid agonist therapy. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice, 17(1),

73.

Illicit Drug Toxicity Deaths by Year in BC

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

2021

270

334

369

529

994

1495

1562

987

1774

2306

30

CHAPTER 3: Data

This project describes the current state of Canada’s

opioid crisis based on quantitative analysis of official

(federal and provincial) data sources. Some municipal

data sources also exist, but they are not widespread and

are not recorded with standardised definitions or to the

same level of assurance.

Deaths, Hospitalizations and EMS

Canada-wide data regarding opioid-related deaths and

hospitalization only begins in 2016. British Columbia does

publish data regarding illicit drug toxicity deaths going as

far back as 1996, but there is not comparable historical

data from other provinces (see fig. 7, pg. 26). To facilitate

comparisons between Canada-wide and BC data, this

report will primarily refer to accidental apparent opioid

toxicity deaths (AAOTDs), which excludes suicides. This

does not significantly impact the analysis because

intentional opioid toxicity deaths represent only a small

portion of all opioid toxicity deaths. In 2021, only 3% (268

out of 7993) of all apparent opioid toxicity deaths were

identified as non-accidental.

35

35

Opioid- and stimulant-related harms. (2022). Government of

Canada.

36

Opioid- and stimulant-related harms. (2022). Government of

Canada.

37

Population and dwelling counts: Canada, provinces and territories.

(2022). Statistics Canada.

The health crisis of drug addiction in Canada is

concentrated in BC, Alberta and Ontario. In 2021, there

were 7,725 AAOTDs in Canada. 49% of those deaths

(3,804)

36

occurred in Alberta and BC, despite the two

provinces representing only 25% of Canada’s

population.

37

Ontario had the highest number of AAOTDs

(2,772), but had a comparably low death rate of 19.4 per

100,000 compared to Alberta’s 36.2 and BC’s 41.9.

38

The

Yukon technically had the highest AAOTD rate at 53.2

per 100,000, but due to its low population this

represented a total of only 23 deaths.

39

38

Opioid- and stimulant-related harms. (2022). Government of

Canada.

39

Opioid- and stimulant-related harms. (2022). Government of

Canada.

31

Fig. 9. Data sourced from Government of Canada (2022)

Hospitalization and EMS rates followed a similar trend. Of

the 4,433-accidental opioid-related poisoning

hospitalizations (AOPHs) in Canada, 2,351 (53%) of them

occurred in Alberta and BC.

40

Looking at ambulance data, the impact on emergency

dispatch caseloads from the addiction crisis is much

higher in BC. Emergency Medical Service (EMS)

responses to suspected opioid-related overdoses are

highest in BC (24,152 responses) – three times the

volume of such incidents in Alberta (8,215 responses),

41

40

Opioid- and stimulant-related harms. (2022). Government of

Canada.

Fig. 10. Data sourced from Government of Canada (2022).

though not all provinces shared EMS data and EMS

responses will be highly impacted by provincial

infrastructure.

Population of People who Use Illegal

Substances in Canada

It is important to assess opioid harms against the

estimated population of people who use substances. The

best source of data to estimate such figures in Canada is

the Canadian Alcohol and Drugs Survey (CADS), a

biennial general population survey of alcohol and drug

use amongst Canadians 15 and older. The CADS breaks

down drug use in several ways. For the purposes of this

41

Opioid- and stimulant-related harms. (2022). Government of

Canada.

32

report, population estimates are based on the ‘illegal drug

use, any of 5 drugs’

42

category for 2013, 2015 and 2017

data, and the ‘any of 6 drugs’

43

category for 2019 data

(see appendix B for details).

Any of 5 drugs:

2013, 2015, 2017

Cocaine/crack, speed/methamphetamine/crystal

meth ecstasy, hallucinogens (excluding salvia), and

heroin

Any of 6 drugs:

2019

Cocaine/crack, speed/methamphetamine, ecstasy,

hallucinogens, heroin, salvia

Based on the CADS figures, in 2019 16.1% of Canadians

(c.5 million people) had used at least one of the 6 select

drugs in their lifetime, while 3.5% had used at least one in

the past year (c.1 million). Prevalence of use was highest

in Alberta and BC, the two provinces who had the highest

percentage of past-year users, with 4.8% (170,800) of

Albertans and 3.8% (157,300) of British Columbians

having used at least one of the drugs in the past year.

44

45

Use of at least one of six illegal drugs, 2019

Canada

Alberta

BC

Past year

3.5%

4.8%

3.8%

Lifetime

16.1%

18.0%

17.8%

* Any of 6 drugs in 2019

42

Cocaine/crack, speed/methamphetamine/crystal meth, ecstasy,

hallucinogens (excluding salvia), and heroin

43

Cocaine/crack, speed/methamphetamine, ecstasy, hallucinogens,

heroin, salvia

44

Canadian Alcohol and Drugs Survey (CADS): 2019 detailed tables.

(2021). Government of Canada.

** No data was available for BC in 2017

Fig. 11. Data sourced from Government of Canada (2021).

Past year drug use appeared to increase between 2013

and 2019 in Canada and Alberta. The number of lifetime

users appeared to drop between 2017 and 2019 in

Canada, Alberta, and BC,

46

but this may be attributable to

changes in the survey.

45

Due to sample size, it cannot confidently be said that past year

drug use was higher in Alberta and lower in BC in 2019 (the only

year for which confidence intervals were provided).

46

Canadian Alcohol and Drugs Survey (CADS): 2019 detailed tables.

(2021). Government of Canada.

0

2

4

6

2013 2015 2017 2019*

Percentage of past year users,

any of 5* drugs

Canada Alberta British Columbia

33

* Any of 6 drugs in 2019.

Fig. 12. Data sourced from Government of Canada (2021).

Fentanyl and Overdose Deaths

The single most significant factor that seems to affect the

number of people dying due to drug overdoses across

Canada’s provinces is the degree to which fentanyl is

present in the drug supply. Based on data from Health

Canada’s Drug Analysis Service (DAS), which identifies

substances contained in samples seized by law

enforcement, fentanyl was detected much more

47

Adulterants, Contaminants and Co-occurring Substances in Drugs

on the Illegal Market in Canada. (2020). Canadian Centre on

Substance Use and Addiction.

48

Substance use surveillance data. (2023). Government of Alberta.

frequently in Western Canada than in Eastern Canada.

47

The table below compares the rate of fentanyl detected in

seized samples in different regions and their respective

AAOTD death rate.

In Alberta, in 2021, fentanyl was detected in 81% of all

accidental drug poisoning deaths.

48

In BC, between 2019

and 2022, fentanyl was detected in 85% of all illicit

overdose deaths.

49

Further, fentanyl detection in BC has

risen in tandem with the death rate (see fig. 8, pg. 28).

50

When considered with the previously reviewed CADS

data, it appears the increase in opioid-related harms in

Canada are driven by the increased toxicity of the supply,

rather than an increase in the number of drug users in the

general population.

49

Illicit Drug Toxicity Deaths in BC: January 1, 2012—October 31,

2022. (2022). British Columbia Coroners Service.

50

Illicit Drug Toxicity Deaths in BC: January 1, 2012—October 31,

2022. (2022). British Columbia Coroners Service.

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

2013 2015 2017 2019*

Percentage of lifetime users, any of 5*

drugs

Canada Alberta British Columbia

Region (2021)

Canada

BC

Ontario

Quebec

Fentanyl

detection

69%

91%

55%

14%

Deaths per

100,000

20.2

42.2

18.7

5.2

34

Policing and Criminal Justice

Illicit drug markets are a key aspect of the addiction crisis

in Canada, being responsible for the supply of

unregulated opioids into communities and with criminals

based in Canada and those overseas exploiting users

suffering addiction. Organised crime understands that

addiction makes their ‘customers’ desperate to maintain

access to drugs, even if this means buying them illegally

from street dealers, or becoming indebted to them. As

the opioid crisis has unfolded, enforcement by the police

and prosecutors has continued, but the true picture of

how drug markets are addressed by law enforcement

agencies is difficult to determine.

Canadian criminal justice and policing statistics are not

sufficiently granular to make comparisons between

municipalities on how cases are processed. Data at the

51

Greg Moreau. (2022). Police-reported crime statistics in Canada,

2021. Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics.

provincial level and reported to StatsCan provides a high-

level summary of drug crime across the country, and

incident data is also available for larger census areas.

Police department data (where such city police

departments exist) is not consistent or comparable.

The majority of reported opioid-related offences occur in

BC. In 2021, BC – comprising approximately 13% of

Canada’s population – had nearly half of all police-

reported opioid possession, trafficking, production, and

important/exportation incidents in Canada. BC’s rate of

opioid-related police reported incidents was more than

four times the recorded incident rate in Alberta.

51

Fig. 13. Data sourced from Statistics Canada (2022).

Glossary of Criminal Justice Terminology and Acronyms:

Incident: a set of connected events usually constituting an

occurrence report. An incident may involve

multiple perpetrators and victims.

Charge: When a person is charged, they are formally

accused of committing an offence. Charges are

made on an individual basis.