1620 Eye Street, NW, Suite 200 | Washington, DC 20006 | (202) 387-6121 | ConsumerFed.org

Auto Insurance Regulation

What Works 2019

How States Could Save Consumers

$60 Billion a Year

J Robert Hunter

Director of Insurance

Douglas Heller

Insurance Expert

February 11, 2019

Abstract

Updating decades of research, the Consumer Federation of America reveals what data shows about

the many different approaches to auto insurance market oversight and consumer protection in the

United States and how some states have saved drivers billions, while others have allowed

significantly increased costs for drivers.

Auto Insurance Regulation - What Works 2019 | Consumer Federation of America 2

Table of Contents

I. Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 4

II. Analysis of Auto Insurance Results from Every State ...................................................... 5

A. Overview ............................................................................................................................... 5

B. Data ....................................................................................................................................... 5

C. Analysis................................................................................................................................. 6

1. Auto Insurance Expenditures ......................................................................................... 6

2. Auto Insurance Liability-Only Expenditures .................................................................. 9

3. Differences By Regulatory System ............................................................................... 11

a) Stronger Regulation Yields Better Results for Consumers Over Time....................12

b) Regulatory Oversight Does Not Inhibit Profitability...............................................14

4. Competition In The States ............................................................................................ 15

a) A Formal Measure of Market Concentration..........................................................16

b) Competition Enhancing Practices among the States...............................................17

III. Findings ............................................................................................................................... 18

A. Stronger Regulation Leads To Lower Rates For Automobile Insurance Consumers ......... 18

B. The Effectiveness of Prior Approval Regulation In California and Hawaii Have Saved

Drivers Billions ................................................................................................................... 20

1. $154 Billion Saved In California and Other Benefits .................................................. 20

2. Hawaiian Drivers Have Benefited From a Strong Prior Approval System ................. 23

C. Americans Have Overpaid For Auto Insurance By $1 Trillion Since 1989. With Better

Regulation They Could Be Saving $60 Billion Per Year. .................................................. 24

IV. Recommendations and Conclusion ................................................................................... 25

Appendix ...................................................................................................................................... 27

1. Average Expenditure and Liability Average Premium (1989, 2015) ................................. 27

2. Average Return On Net Worth (1989-2016) ...................................................................... 28

3. Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) By State ..................................................................... 29

4. Other Data Reviewed (Table 1) .......................................................................................... 29

5. Other Data Reviewed (Table 2) .......................................................................................... 31

Auto Insurance Regulation - What Works 2019 | Consumer Federation of America 3

Table of Figures

Figure 1. Smallest and Largest Percentage Increases in Auto Insurance Expenditure (1989-2015)

......................................................................................................................................................... 7

Figure 2. Percentage Increase of Auto Insurance Expenditures (1989-2015) ................................ 7

Figure 3. Dollar Increase in Auto Insurance Expenditures (1989-2015) ........................................ 8

Figure 4. Smallest and Largest Dollar Increases in Auto Insurance Expenditure (1989-2015) ..... 9

Figure 5. Change in Liability Average Premium (1989-2015) ..................................................... 10

Figure 6. States With More Than 100% Increase in Liability Average Premium (1989-2015) ... 11

Figure 7. Regulatory System by State.......................................................................................... 12

Figure 8. Regulatory Systems of States with Lowest and Highest Rate Changes (1989-2015) .. 13

Figure 9. Auto Insurance Expenditure Change by Regulatory Rating System (1989-2015)........ 13

Figure 10. Auto Insurance Liability Average Premium Change by Regulatory Rating System

(1989-2015)................................................................................................................................... 14

Figure 11. Profitability by Regulatory System, Weighted by Market Size ................................. 14

Figure 12. Most and Least Profitable States (Average Annual Profitability) (1989-2016) .......... 15

Figure 13. Least Concentrated Auto Insurance Markets .............................................................. 16

Figure 14. Average HHI by State Regulatory System .................................................................. 17

Figure 16. Percentage Change in Average Insurance Costs (1989-2015) .................................... 21

Figure 17. Auto Insurance Expenditure Increases in Hawaii at Various Intervals Compared With

1989 Expenditures ........................................................................................................................ 23

Figure 18. Theoretical Annual Consumer Savings (In Millions) if State Adopted California-Style

Oversight ....................................................................................................................................... 24

Auto Insurance Regulation - What Works 2019 | Consumer Federation of America 4

I. Introduction

When Americans shop for auto insurance, as required by law in every state but New

Hampshire, the premiums they find in the market depend upon a combination of insurance losses

and expenses, driving and non-driving related characteristics of the individual driver, and a

variety of management-level decisions reflecting the company’s market objectives. However,

there is also a macro-level influence on auto insurance premiums stemming from the regulatory

framework in place in each state-based market. As insurance products are overseen exclusively

by the states, each state market is different, and those differences can be assessed in terms of

consumer outcomes.

In this report updating research conducted in 2008 and 2013 to now cover 30 years of

results, Consumer Federation of America (CFA) looks at state consumers’ auto insurance

expenditures and other data in each state to determine what types of rules best serve American

auto insurance policyholders. There are a variety of actuarial reasons why one state might expect

higher auto insurance expenditures than another – including different coverage limits, different

levels of traffic density, different mix of vehicle types – and these reasons are generally

consistent over time. Those statewide characteristics are baked in to the differences in premiums

between states, and we would expect drivers in a state with high traffic density and high

coverage limits to pay more for auto insurance than those in a state with low traffic density and

low coverage requirements. But, as this report illustrates, the trajectory of rates over time in

different states are wildly different, and we have concluded that the level of consumer protection

and regulatory oversight in the states plays an important role in determining that trajectory.

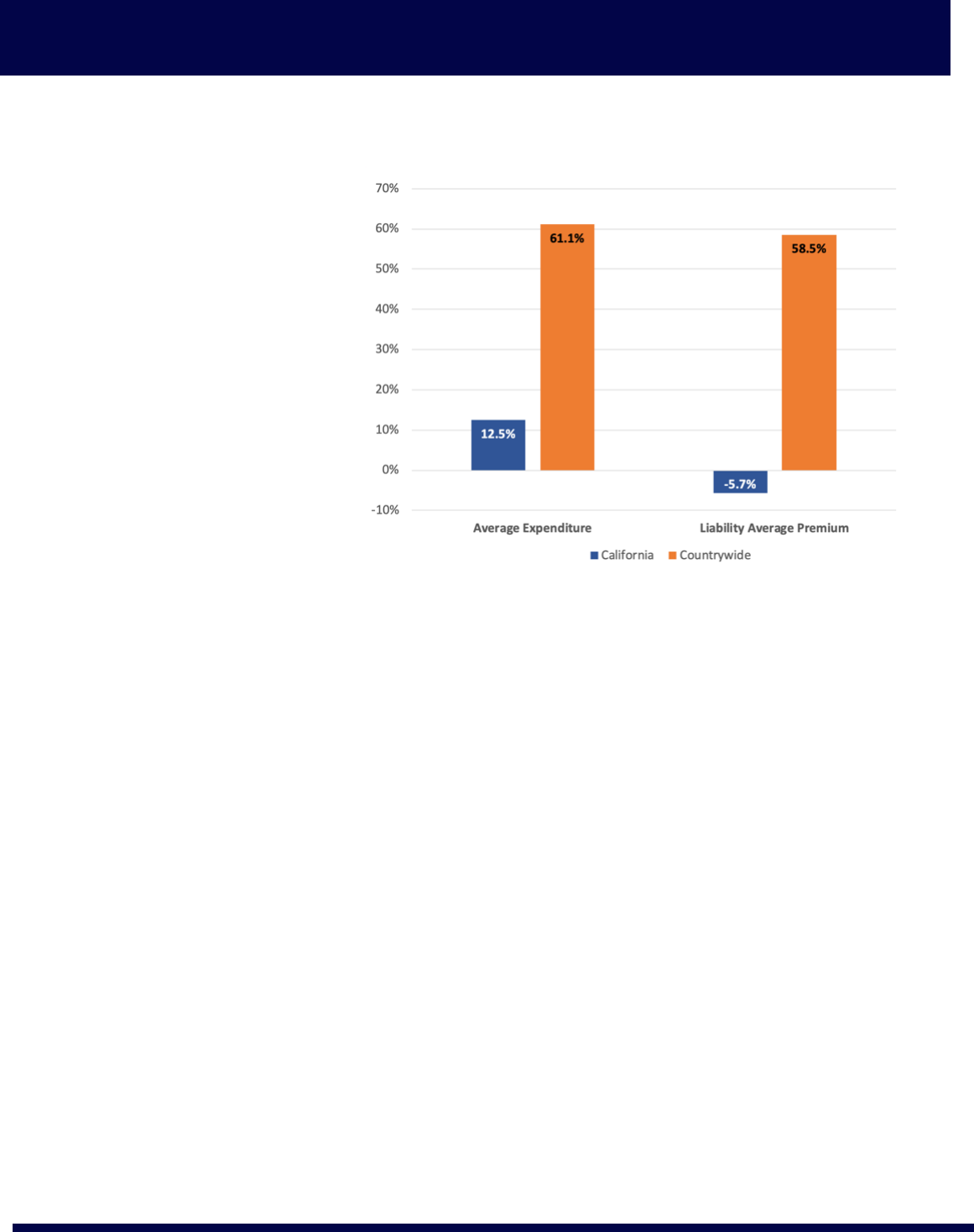

Since 1989, the average expenditure on auto insurance by Californians has increased by

12.5%, while the average increase across the country has been 61.1%, nearly five times that

faced by California drivers. When it comes to the cost of liability insurance, the state-mandated

portion of coverage, Californians paid 5.7% less in 2015 than they paid in 1989 (without any

adjustment for inflation), while the nationwide average increased by 58.5%.

In addition to the savings achieved under California’s consumer protection system, it is

notable that the system of strong regulation of insurance companies has fostered a robust and

extremely competitive market, helping California to become the second least concentrated auto

insurance market in the nation.

The data show, and this is consistent with prior CFA analyses over the past decade, that

strong “prior approval” oversight of auto insurance markets, in which insurance companies have

to justify rate changes before imposing them on policyholders, leads to the best outcomes for

consumers. Over the past 30 years, no set of state rules has been as beneficial to its resident

drivers as the consumer protections put in place by California voters in November 1988 through

Auto Insurance Regulation - What Works 2019 | Consumer Federation of America 5

Proposition 103. We calculate that California drivers have saved $154 billion in auto insurance

premiums as a result of voters’ decision to adopt the 1988 ballot initiative. Our research

indicates that if every state market in the nation had been strengthened by California-style

consumer protection, American drivers would have saved $60 billion in 2015 and nearly a

trillion dollars over the past 30 years.

In the following pages we first summarize the research and our findings with respect to

the experience in all 50 states and Washington, DC. Thereafter we provide a detailed look into

the experience in California, including why we believe that state has succeeded in protecting

drivers better than any other.

II. Analysis of Auto Insurance Results from Every State

A. Overview

A primary purpose of this report is to assess the effectiveness of the various regulatory

approaches to auto insurance across the country. Through our research we have identified the

best practices that can serve as models for regulators and policymakers seeking to ensure a

competitive and fair market that is first and foremost protective of consumers. In order to

develop our findings, we have looked at data from 1989-2015 (the last year for which complete

data were available when the research was conducted, except where noted)

1

and considered a

variety of questions about state markets and the regulatory systems in each state. Among those

questions are:

• How have auto insurance expenditures changed over time?

• How have liability-only expenditures changed over time?

• How have expenditure changes varied under different regulatory systems?

• How competitive is the auto insurance market in each state?

• How profitable has the industry been in each state?

B. Data

The data in this report are public data published by the National Association of Insurance

Commissioners (NAIC) over the past 30 years. Each year the NAIC publishes an “Auto

Insurance Database Report” that is “compiled to make information about cost factors in each

state readily available to insurance regulators monitoring the market, and to the public.”

2

These

1

The sources of premium and expenditure data contained in this report, unless otherwise described, are the National

Association of Insurance Commissioners Auto Insurance Database Reports (1990-2015), NAIC Report

on Profitability by Line by State (1999-2016) and Best’s Aggregates and Averages, various editions.

2

NAIC, December 2017. Auto Insurance Database Report 2014/15. p.1.

Auto Insurance Regulation - What Works 2019 | Consumer Federation of America 6

reports break out data on premiums, expenditures, and exposures by coverage and, critically for

this study, by state.

This report focuses primarily on the Average Expenditure in each state, which “is the

total written premium for liability, collision, and comprehensive coverages divided by the

liability written car-years (exposures). This assumes that all insured vehicles carry liability

coverage but do not necessarily carry the physical damage coverages (i.e., collision and/or

comprehensive). The average expenditure is an estimate of what consumers in the state spent, on

average, for auto insurance.” [Emphasis added.]

Where we have used other data in the report, we have cited it and described our

calculations. The data in the report are all publicly available and the calculations easily

reproduced.

C. Analysis

1. Auto Insurance Expenditures

Average auto insurance expenditures grew by 61.1% countrywide between 1989 and

2015 (the last year for which data were available during the course of research). The average

annual expenditure countrywide in 1989, in unadjusted dollars, was $552; in 2015 it was $889,

or $337 more spent on auto insurance. Among the states, California drivers faced the smallest

increase, 12.5%, while Nebraskans encountered the sharpest increase, 139.3%, during this

period.

During this time period the average state increase was 75.1% and the median increase

was 71.5%. These average and median increases are significantly higher than the rate of

expenditure growth calculated on a countrywide basis (61.1%) largely because California’s

disproportionate share of the national market (about 1 of every 8 insured vehicles is in the state)

has an outsized impact when quantifying change for the nation as a whole.

Other than California, only Hawaii (+13.6%) experienced a rate increase less than 25%

during the period, while 12 states experienced increases topping 100% since 1989. Figure 1

presents the states with the smallest and largest increases by percentage over the time period, and

Figure 2 provides the increases for all states.

Auto Insurance Regulation - What Works 2019 | Consumer Federation of America 7

Figure 1. Smallest and Largest Percentage Increases in Auto Insurance Expenditure

(1989-2015)

Smallest Increases

Largest Increases

California

12.5%

Nebraska

139.3%

Hawaii

13.6%

North Dakota

125.2%

New Hampshire

27.2%

South Dakota

125.1%

New Jersey

28.8%

Michigan

123.5%

Pennsylvania

35.9%

Louisiana

115.4%

Connecticut

41.7%

Kentucky

113.5%

Maine

42.1%

Wyoming

106.3%

Arizona

45.1%

Oklahoma

106.3%

Massachusetts

45.3%

Montana

106.1%

District of Columbia

49.4%

Kansas

105.0%

Figure 2. Percentage Increase of Auto Insurance Expenditures (1989-2015)

Auto Insurance Regulation - What Works 2019 | Consumer Federation of America 8

During the period reviewed, the actual, unadjusted dollar impact of these changes on state

consumers averaged $348, and only Hawaii and California saw increases that were less than

$100 total. Hawaii, which had a lower average expenditure in 1989 than California, counted a

$91 increase during the period, while California experienced a $93 increase. On the other end of

the spectrum, Louisiana and Michigan expenditures rose the most, by $660 and $681,

respectively. Florida, Delaware, and New York also faced steep increases, each with average

expenditures rising by more than $550. Figure 3 illustrates the dollar impact of increasing auto

insurance expenditures over the 27-year period.

Figure 3. Dollar Increase in Auto Insurance Expenditures (1989-2015)

Auto Insurance Regulation - What Works 2019 | Consumer Federation of America 9

Figure 4 presents the smallest and largest dollar increases during the time period

reviewed.

Figure 4. Smallest and Largest Dollar Increases in Auto Insurance Expenditure (1989-

2015)

Smallest Increases

Largest Increases

Hawaii

$91.36

Michigan

$680.55

California

$93.48

Louisiana

$659.81

New Hampshire

$165.90

Florida

$575.04

Maine

$182.89

Delaware

$571.62

Idaho

$225.52

New York

$569.77

Pennsylvania

$232.15

Texas

$436.87

Indiana

$239.95

Kentucky

$426.26

Ohio

$254.86

Oklahoma

$424.32

Vermont

$256.75

Rhode Island

$422.13

Arizona

$262.50

West Virginia

$418.16

As is obvious from these tables, and as will be discussed in the analysis section below,

California and Hawaii stand out among the states.

2. Auto Insurance Liability-Only Expenditures

In every state but New Hampshire, drivers are required to purchase a basic liability policy

as a condition for driving. This mandate includes Personal Injury Protection (no-fault) coverage

in some states, while in many states it is limited to third-party liability (injuries and damage to

others), and in some states Uninsured Motorist coverage is also required. In its Auto Insurance

Database Report, NAIC combines these coverages, along with Medical Payments coverage, to

form the data series “Liability Average Premium,” which we assess below.

By excluding the amount spent on comprehensive and collision coverage, Liability

Average Premium offers a closer approximation of the cost of coverage that is required of

drivers. These data, when considered in light of the whole report, help assess how states have

done in protecting lower-income drivers and others who purchase a state’s minimum-limits

policy in order to comply with the state mandate.

Since 1989, the countrywide liability average premium has increased by 58.5%. Only two

states have seen reductions in the premium paid for liability coverage. In California and Hawaii,

premiums for liability insurance dropped by 5.7% and 2.0%, respectively. Figure 5 below shows

the change in liability average premium, ranked from smallest to largest change.

Auto Insurance Regulation - What Works 2019 | Consumer Federation of America 10

Figure 5. Change in Liability Average Premium (1989-2015)

While it costs drivers in California and Hawaii less to buy liability coverage in 2015 than

it did three decades ago, eleven states faced premiums that had doubled or, in the case of

Michigan, tripled between 1989 and 2015, as shown in Figure 6. For lower-income drivers who

do not lease or make payments on their vehicle (and, thereby, may forego comprehensive and

collision coverages), these significant price hikes on a product they are required to purchase has

led to considerable discussion among policymakers, regulators, and consumer advocates about

the affordability of state mandated auto insurance policies.

Auto Insurance Regulation - What Works 2019 | Consumer Federation of America 11

Figure 6. States with More Than 100% Increase in Liability Average Premium (1989-

2015)

State

Increase

Michigan

215.9%

Nebraska

144.1%

Kentucky

141.0%

Utah

128.3%

South Dakota

113.3%

Oklahoma

111.4%

Delaware

111.1%

Wyoming

110.0%

New York

107.7%

Louisiana

106.8%

Florida

103.9%

3. Differences by Regulatory System

In the United States, auto insurance is regulated at the state level. Each state has its own

unique set of laws and no two states' insurance regulation regimes are precisely the

same. However, the states can be grouped, generally, among six different regulatory structures,

ranging from the more vigorous “prior approval” approach to rates in California to the virtual

deregulation of rates in Wyoming. The six structures, as illustrated in Figure 7, are:

• Prior Approval

• File and Use

• Use and File

• Limited Flex

• Flex

• Deregulated

For this report, we have generally followed the National Association of Insurance

Commissioners (NAIC) report on state rate filing laws

3

except as follows:

a) We have added a category – Limited Flex – that reflects four states’ laws that allow

insurers to make (largely) unregulated changes to rates in certain instances, but under

constraints that are more limiting than the states identified by the NAIC as Flex

Rating states. The eight states that are identified as Flex or Limited Flex might

reasonably be treated as Flex Rating systems, but we have decided to distinguish

between those named as Flex by NAIC and those identified otherwise but having a

significant Flex component.

3

NAIC, December 2017. Auto Insurance Database Report 2014/15. p.234.

Auto Insurance Regulation - What Works 2019 | Consumer Federation of America 12

b) NAIC lists Florida as a Prior Approval state with the following caveat: “Companies

may Use and File at the risk of having to refund any excessive charge. Actual text of

the Law says ‘File and Use.’” Because companies are not required to seek prior

approval, we treat it as a File and Use state per the text of state law.

Countrywide, there are 13 prior approval states, 20 file and use states, nine use and file

states, eight flex- or limited flex-rating states, and one deregulated state.

Figure 7. Regulatory System by State

a) Stronger Regulation Yields Better Results for Consumers Over Time

Auto Insurance Regulation - What Works 2019 | Consumer Federation of America 13

Our findings show that states with stronger regulatory systems - that is, states that require

prior approval of rates before they can take effect - have had the most success in slowing the rate

of increases over time. Figure 8 shows the regulatory system of the five states with the smallest

auto insurance expenditure changes and the five states with the largest increases.

Figure 8. Regulatory Systems of States with Lowest and Highest Rate Changes (1989-

2015)

Lowest Rate Changes

Highest Rate Changes

State

Regulatory

Structure

Change

State

Regulatory

Structure

Change

California

Prior Approval

12.5%

Nebraska

File and Use

139.3%

Hawaii

Prior Approval

13.6%

North Dakota

Limited Flex

125.2%

New Hampshire

File and Use

27.2%

South Dakota

File and Use

125.1%

New Jersey

Prior Approval

28.8%

Michigan

File and Use

123.5%

Pennsylvania

Prior Approval

35.9%

Louisiana

Prior Approval

115.4%

Although each state’s application of their regulatory system is different – particularly

among the group of prior approval states – the data show that prior approval states taken as a

group provide significantly better results for consumers than other regulatory approaches. This

is the case whether we evaluate the systems using a simple or weighted average, as is detailed in

Figure 9. The simple average demonstrates the systemic pull of the regulatory approach rather

than the particular rate trajectory of a single large state like California or Texas. The weighted

average allows us to adjust our assessment of the rating system’s efficacy to account for some

small state outliers on either end of the data set, such as Hawaii and the Dakotas.

Figure 9. Auto Insurance Expenditure Change by Regulatory Rating System (1989-2015)

Rating System

Percent Change

Simple Average

Weighted Average

Prior Approval

63.2%

45.0%

Use and File

74.7%

70.0%

File and Use

78.5%

82.3%

Limited Flex

85.8%

82.9%

Flex Rating

86.7%

91.7%

Deregulation

106.3%

106.3%

It is not surprising that Prior Approval states, in which insurance companies are subject to

up-front scrutiny of their rate hikes, have yielded the best results for consumers over time.

Similarly, it is not surprising that the deregulation approach in Wyoming and the partial

deregulation of the flex states have offered the least protection. In those states, insurers have the

ability (in varying degrees) to raise rates without any scrutiny whatsoever. Clearly, they have

taken advantage of that. The fact that the use and file states have seen more constrained premium

Auto Insurance Regulation - What Works 2019 | Consumer Federation of America 14

increases than file and use states suggests that it is not the timing of the paperwork, but scrutiny

by the regulator that makes a difference. In both cases the likelihood of regulatory review and

rejection of rate increases is low but not quite as low as the statutory lack of accountability given

insurers in the flex-rating and deregulated states.

Similar, though more pronounced, results are apparent when assessing the change in

liability premiums among the different regulatory systems. As Figure 10 illustrates, drivers in

prior approval states faced the least severe premium increases on the coverages that are required

by state law. Less regulated systems provided significantly less protection from rate increases for

the mandatory coverage during this period.

Figure 10. Auto Insurance Liability Average Premium Change by Regulatory Rating

System (1989-2015)

Rating System

Weighted

Average Change

Prior Approval

36.1%

Use and File

67.9%

File and Use

89.5%

Flex Rating

98.5%

Limited Flex

103.0%

Deregulation

110.05%

b) Regulatory Oversight Does Not Inhibit Profitability

We considered the question of whether the regulatory system in a state tends to support

more or less profitability for the industry. Presumably, insurers would prefer a system that

supports higher profits. As Figure 11 indicates, however, profits are relatively unaffected by

regulatory systems, except that Flex Rating systems seem to trend toward lower profitability.

Figure 11. Profitability by Regulatory System, Weighted by Market Size

Regulatory

System

Total Premium

(in billions)

Average Annual

Profitability

Prior Approval

$72.8

7.99%

File and Use

$85.4

7.24%

Use and File

$24.5

8.87%

Limited Flex

$17.4

8.33%

Flex

$8.3

4.79%

Deregulated

$0.4

9.60%

Total

$209.0

7.69%

Auto Insurance Regulation - What Works 2019 | Consumer Federation of America 15

Perhaps most notable is the clear evidence that the stronger regulatory oversight

associated with Prior Approval systems does not inhibit insurer profitability as some opponents

of regulation might suggest. Figure 12 illustrates the five most profitable states since 1989 and

the five least profitable states. This, along with the full list of states, reveals that, for this period,

those with prior approval systems are distributed throughout the profitability range, with Hawaii

as the most profitable, and Nevada and Louisiana as the least profitable. Another prior approval

state, Alabama, had an 8.4% average annual profit, the median figure for the dataset. See

Appendix 1-D.

Figure 12. Most and Least Profitable States (Average Annual Profitability) (1989-2016)

Most Profitable

Least Profitable

State

Regulatory

Structure

Profitability

State

Regulatory

Structure

Profitability

Hawaii

Prior Approval

16.6%

Louisiana

Prior Approval

2.6%

Maine

File and Use

13.0%

Nevada

Prior Approval

3.1%

District of

Columbia

File and Use

12.8%

South

Carolina

Flex

3.1%

New Hampshire

File and Use

12.5%

Michigan

File and Use

3.5%

Vermont

Use and File

12.1%

Kentucky

Flex

4.5%

It is common to assume that regulation limits profitability, but that is a

mischaracterization of both the public policy goal underlying regulation and, as shown in this

data, not borne out by the facts. The public policy orientation of insurance regulation, and price

regulation generally, is to eliminate excessive profits from overcharging customers and to

prevent insolvency from underpricing the product. There is no reason to believe that a rigorous

prior approval system, when built on that public policy rationale, should make it more unlikely

for a law-abiding insurer to earn a reasonable profit. Indeed, virtually every state requires

insurers to price insurance within the parameters of the inadequate–excessive construct, so prior

approval of rates is a law enforcement tool, not an additional standard. That prior approval states

do not clump together in one area of the profitability range affirms this point and should be

recognized as a key finding that dispels some of the anti-regulation rhetoric that is used to

challenge prior approval systems.

4. Competition in the States

In many markets, competition can be a force for lower prices. In the auto insurance

market, where prices are meant to hew closely to the risk of loss, competition can help improve

efficiency, incentivize safety and loss mitigation efforts, and improve service quality. But,

because the insurance market is different than most markets, special attention is needed to foster

competition.

Auto Insurance Regulation - What Works 2019 | Consumer Federation of America 16

Unlike most products and services sold in the American marketplace, auto insurance is a

government-mandated purchase for motorists in all states, save New Hampshire. This removes

the demand-side power of consumers to say “no” to the market as a whole if it is overpriced or

non-competitive. Additionally, insurance is a complex financial instrument that, for most people,

is purchased but rarely used, and studies show that consumers do not shop for coverage

frequently. Finally, the insurance industry has a rare exemption from federal antitrust laws, and

around the country, where state authority over collusive behavior exists, it is rarely enforced. The

interaction of these unique qualities makes the role and relevance of a competitive marketplace a

complicated concern.

We consider two indicators of competitiveness, a standard measure and an analysis of

state policy regarding market participation.

a) A Formal Measure of Market Concentration

To identify the level of competition in the auto insurance market, we used the test

commonly employed by the United States Department of Justice (DOJ) to measure market

concentration, the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI).

4

The closer a market is to being a

monopoly, the higher the HHI index. The DOJ considers a market with a score of less than

1,000 to be a competitive marketplace, a score of 1,000-1,800 to be a moderately concentrated

marketplace and 1,800 or greater to indicate a highly concentrated marketplace. Figure 13

provides the list of the ten states with the lowest HHI.

Figure 13. Least Concentrated Auto Insurance Markets

State

HHI

Maine

703

California

723

North Dakota

741

Vermont

760

Connecticut

770

New Hampshire

786

Utah

786

South Dakota

819

Idaho

822

Washington

825

4

The HHI is calculated by squaring the market share of each firm competing in a market and totaling the resulting

figures.

Auto Insurance Regulation - What Works 2019 | Consumer Federation of America 17

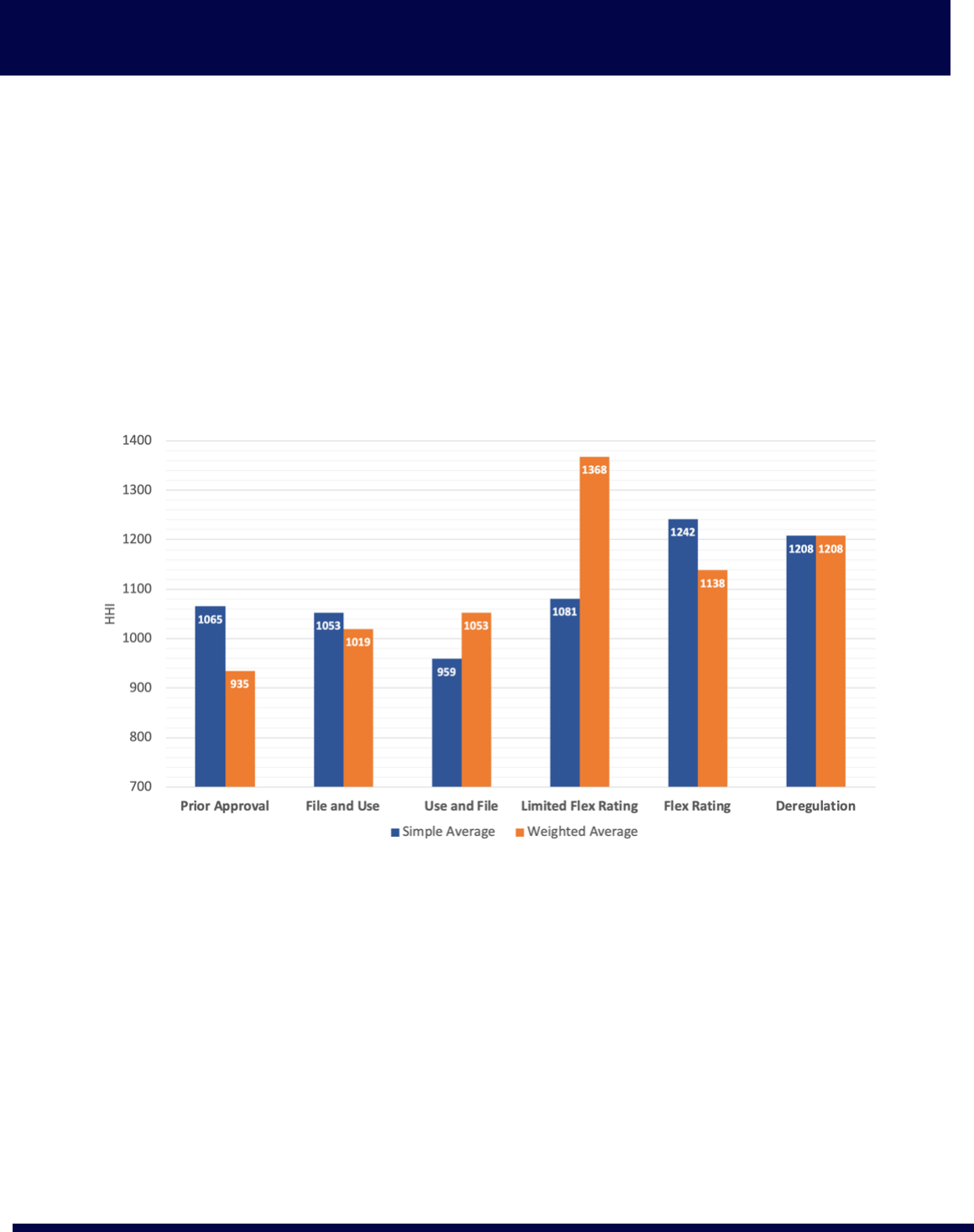

As Figure 14 illustrates, when market concentration is reviewed in the context of state

regulatory systems, we find that the deregulated and flex-rating states have higher levels of

market concentration. Measured on a premium volume-weighted basis, prior approval states are

the most competitive but using a simple average the use and file states are more

competitive. Taken together, the data show that the nexus between regulatory oversight and the

robustness of the auto insurance market does not support a conclusion that regulation limits

competition and deregulation encourages it. Just the opposite appears to be the case, with states

that allow greater amounts of unregulated activity in the auto insurance market finding their

markets most likely to be dominated by a small number of insurers.

Figure 14. Average HHI by State Regulatory System

b) Competition Enhancing Practices among the States

Given the unique market power held by insurance companies vis à vis consumers – who

have to purchase their product – states can play an important role in ensuring that motorists can

access a competitive market for auto insurance. Below we describe several competition

enhancing rules and practices we found amongst the states:

1. Take All Good Drivers. Four states – California, Massachusetts, New Hampshire,

and North Carolina – require insurers to take all good drivers who apply for

insurance. In these states, a good driving record gives a consumer the right to obtain

insurance from any licensed insurance company. This is a pro-competitive

requirement, since all states but New Hampshire require that consumers purchase

Auto Insurance Regulation - What Works 2019 | Consumer Federation of America 18

auto insurance as a condition of driving their own car. Because of these mandatory

insurance laws, auto insurance demand is inelastic. A mandate on insurers requiring

that coverage be made available to good drivers balances this supply-demand

situation.

2. Prohibit Shifting Good Drivers to Non-Preferred, Higher Rate Subsidiaries.

California is also the only state to require that an insurer group place good drivers

into the lowest priced policy available from any of its affiliated companies when an

insurance applicant asks for a quote. This blocks insurance companies from shifting

drivers with good records into the expensive insurance policies written by an insurer’s

non-preferred subsidiary, which has been one of several techniques that insurers use

to avoid selling policies to good drivers who do not fit into a company’s target

demographic.

3. Enact and Enforce Antitrust Laws. The insurance industry has historically engaged

in extensive price fixing, relying in many instances on shared pricing tools developed

by industry-controlled rating and advisory organizations. Collusive data sharing tends

to result in inflated prices and unfair rating practices, which antitrust enforcement

would tend to diminish. However, all states, except Illinois and California, which

have exercised some antitrust authority, continue to authorize insurers to engage in

conduct that application of antitrust laws would otherwise prohibit.

III. Findings

A. Stronger Regulation Leads to Lower Rates for Automobile Insurance

Consumers

In order to assess the efficacy of the regulatory regimes in place around the country, we

evaluated four significant factors in each state and for each of the six regulatory systems in use

across the nation. By evaluating data related to changes in consumers’ cost of insurance,

profitability of companies, and overall competitiveness of the state insurance markets, we are

able to draw conclusions about the various state markets and the systems that govern them.

The first two tests examined the ability of a state and rating system to hold down rate

increases. The first of these tests considered the change in Average Expenditures over time – that

is how much more or less people pay for all their auto insurance coverage – and the second test

examined how much more or less people pay for the portion of auto insurance – liability

coverage – that is typically required under state laws. It is very clear in the results that lower

price increases were associated with more stringent regulatory regimes, while less oversight led

to higher price increases over time. This fact is brought into stark relief when reviewing the

Auto Insurance Regulation - What Works 2019 | Consumer Federation of America 19

liability premiums only, where the nation’s most rigorous regulatory system – in California –

saw premiums that are lower than they were in 1989, even as the nation’s premiums rose by

nearly 60 percent. In both tests of rates, Prior Approval states taken together saw the smallest

increases and while the more weakly overseen flex and deregulated states allowed for the largest

rate increase during the nearly three decades reviewed.

Next, we examined insurer profitability as a function of regulatory system. Although

premium increases were significantly below average in prior approval states, profits were not.

The experience of insurers across the country suggests that the role of consumer protection rules

was to improve efficiency rather than draw down company profits. Prior approval regulation, it

appears, serves as a stabilizing force that allows companies to succeed even as it protects

consumers from excessive pricing. At the very least, the profitability results demonstrate that

prior approval oversight of insurance companies cannot be seen as an inhibitor of insurance

company success. Further, it is evident that in all cases and under any regulatory system, insurers

have generally thrived over the decades, enjoying reasonable profitability in virtually every state.

Finally, we tested the competitiveness of markets under each system of regulation and

found that prior approval regulation yielded, on a weighted average, the most competitive

insurance markets. The less regulated states, including the various flex systems and deregulated

Wyoming, exhibited much weaker levels of competition. There is some irony that deregulated

insurance markets are sometimes described as “Competitive States,” when, in fact, weak

regulation more closely correlates with highly concentrated markets than with competition.

Overall, the Prior Approval system of regulation works best for consumers. This system

is superior at holding prices down while allowing reasonable insurer profits and maintaining a

competitive market. It is also clear that the worst regulatory regimes for consumers are the

Deregulated and Flexible Rating systems, which do not hold down prices, foster less competitive

markets and often allow higher than average profits to insurers.

We also analyzed data on several other key factors that could affect insurance rates,

including seatbelt laws, bad faith claims settlement laws, uninsured motorist population, size of

the residual market, the legal regime in use for auto claims, thefts, traffic density, disposable

income, repair costs and other factors, as shown in the appendices. These data do not appear to

be confounding variables and instead help us affirm the first general finding that Prior Approval

regulation is the best system for consumers. Additionally, as discussed below, the data shed light

on the second significant finding of this analysis, that California’s active prior approval system

has consistently proven itself the strongest in the nation in ensuring access to reasonably priced

auto insurance rates.

Auto Insurance Regulation - What Works 2019 | Consumer Federation of America 20

B. The Effectiveness of Prior Approval Regulation in California and

Hawaii Have Saved Drivers Billions

The degree to which California and, in recent years, Hawaii have set themselves apart

from the rest of the country is astounding and reflects the efficacy of prior approval regulation in

conjunction with a strong consumer orientation in its implementation. The data reviewed in this

study begin in 1989, immediately after California voters enacted Proposition 103, which

converted California from a deregulated state to a strongly regulated state incorporating several

consumer protection rules, and marked the beginning of the transformation from one of the most

expensive places in America to insure a vehicle to a state in which premiums are below the

national average.

1. $154 Billion Saved in California and Other Benefits

By comparing California premiums in 2015, after 27 years of Prop 103, to what they

would have been if, instead, these premiums simply followed the national average growth, CFA

calculates that Californians have saved $154 billion on their auto insurance premiums, or an

average savings of nearly $6 billion each year. Put differently, using an estimate of 22 million

insured vehicles in California, there is an annual $275 Prop 103 auto insurance savings for every

insured car on the road.

In order to reach this figure, we calculated the change in auto insurance expenditures

between 1989 and 2015 for the country as a whole and for California only. We then calculated

the savings California enjoyed compared to the savings if California had prices change at the

national averages, a conservative choice since prior to the passage of Proposition 103, the price

increases in California greatly exceeded the national price changes. Because the countrywide

data include California data, this trajectory is also conservative in that the national price changes

were restrained by the savings actually experienced in California.

A review of California’s auto insurance consumer protections illustrates that the savings

California drivers have accrued over the years are not the only benefit of having the nation’s

strongest auto insurance protections in the nation. California passed virtually every test for good

performance, with the exception of a high-uninsured motorist population (which we expect is

changing as discussed below) and profit levels for insurers that are higher than necessary. We

found the following results for California:

Auto Insurance Regulation - What Works 2019 | Consumer Federation of America 21

• Ranked first among all states

in holding down overall rate

increase;

• Ranked first among all

states in holding down the

cost of mandatory liability

coverage;

• Ranked second in market

competitiveness as

measured by the HHI;

• Has totally repealed its

antitrust exemption for

automobile insurers;

• Has a low residual market

population (i.e., low level

of participation in higher

cost assigned risk plans);

• One of only four states to guarantee insurance to a good driver from any insurer the driver

chooses;

• The only state to require that a person’s driving record be the most important factor in

determining insurance rates;

• One of only three states to ban the use of credit scoring;

• The only state that funds consumer participation in the ratemaking process when consumers

or consumer organizations make a substantial contribution to the process;

• The state with the most regulatory transparency, with all rate and rule filing data and

information supplied by insurance companies made available to the public;

• The only state that bars insurance companies from considering whether a motorist was

previously insured, or had a gap in coverage (such as a short drop of insurance during a time

with no car) when pricing applicants for auto insurance; and

• One of only two states (along with New Jersey) with a special low-cost auto insurance policy

for low-income drivers.

• The only state with a suite of ratemaking innovations to keep rates down including the

removal from rates of the cost of fines and bad faith judgments the insurer received for bad

behavior, removal of political contributions and lobbying expenditures, limits on the amount

of executive compensation that can be included in the rates, and exclusion of certain types of

advertising costs from rates.

On the negative side, California has the twelfth highest uninsured motorist population in

the nation according to the industry organization, the Insurance Research Council (IRC). While

still too high, the population has decreased sharply from the 1980s when California had one of

Figure 16. Percentage Change in Average Insurance Costs

1989-2015

Auto Insurance Regulation - What Works 2019 | Consumer Federation of America 22

the highest rates of uninsured motorists. As of 2015, California has an uninsured motorist rate of

15 percent, according to the IRC study, compared to a 13 percent rate nationally.

5

California’s

unique situation as home to the most undocumented residents in the nation may explain some of

the uninsured population. However, we expect that estimates of uninsured motorists in California

will be lower in coming years when the data catch up to the growing population of

undocumented immigrants who have obtained driver’s licenses under a law that took effect in

2015, making it easier for those drivers to purchase insurance. According to the California

Department of Motor Vehicles, as of April 2018 more than one million licenses have been issued

to previously undocumented immigrants since 2015,

6

which is also the last year for which

uninsured motorist estimates are available. Indeed, researchers at Stanford University found that

hit and run accidents decreased by 7 - 10% after undocumented drivers were allowed to get a

driver’s license even though overall accident rates did not change, strongly suggesting a

significant increase in insured drivers.

7

If the implication of this finding bears out, California’s

uninsured motorist population might already be significantly lower than the national average.

A second area where California’s results are on the wrong side of the national average is

in auto insurance company profitability. While effective regulation will allow for reasonable

profits, insurers in California have enjoyed an average annual Return on Net Worth of 10.5

percent compared with an 8.5 percent annual average nationally. This raises the question as to

whether insurers should be required to further reduce their rates in California. The fact that

California has seen both below average rate changes and above average profits also suggests that

the nation’s less well-regulated markets are much less efficient than they could be, which, as

discussed below, is likely costing consumers around the country billions of dollars annually.

A third area in which California could improve the auto insurance market for consumers

has to do with a loophole that insurers have exploited in recent years at the expense of California

drivers. Under California’s auto insurance rules, consumers are allowed to buy auto insurance,

usually at discounted rates, as part of a group plan. Historically, this has provided benefits to

members of groups such as teacher organizations and senior citizen associations. Over the last

several years, however, insurers have expanded the use of this group insurance provision to

group drivers by occupation – irrespective of their membership in any particular association –

and differentiate premiums based on drivers’ job titles. This “group pricing” has unfairly harmed

people with lower wage occupations as well as the unemployed in California. Consumer

advocates have sought clarifications of the rules to prohibit this expansive and discriminatory

interpretation of state law, but consideration of this problem has languished under the

administrations of the prior two Insurance Commissioners.

5

Uninsured Motorists, 2017 Edition, Insurance Research Council.

6

https://www.dmv.ca.gov/portal/dmv/detail/pubs/newsrel/2018/2018_30

7

Lueders, H., Hainmueller, J., & Lawrence, D. (2017). Providing driver’s licenses to unauthorized immigrants in

California improves traffic safety. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 201618991.

Auto Insurance Regulation - What Works 2019 | Consumer Federation of America 23

These few weaknesses do not, however, alter the very clear finding of our research that

California’s strong prior approval system of auto insurance regulation has been the best in the

nation for consumers. In prior studies, CFA has provided significant detail about the laws and

regulations that have guided California to such extraordinary success.

A complete review of the history and structure of California’s auto insurance regulatory

system is available in Part 2 of CFA’s 2013 “What Works” report on auto insurance, which is

available at https://consumerfed.org/pdfs/whatworks-report_nov2013_hunter-feltner-heller.pdf.

2. Hawaiian Drivers Have Benefited From a Strong Prior Approval System

While California has consistently stood out from the rest of the nation in CFA’s rate

change analyses over the past 20 years, Hawaii has produced significant savings for consumers

relative to the nation in recent years. Since 2010, Hawaii has seen average auto insurance

expenditures decline, joined only by Alaska as states to see costs drop during the post-financial

crisis period, when higher premiums were predicted as high rates of joblessness began their

return toward historical norms. Though not as strikingly as in the past few years, as Figure 17

shows, Hawaiian auto insurance premiums have grown much less than the national average for a

long time.

Figure 17. Auto Insurance Expenditure Increases in Hawaii at Various Intervals

Compared With 1989 Expenditures

1989-1998

1989-2005

1989-2010

1989-2015

Percentage

Change

18.4%

25.2%

13.7%

13.6%

Rank

8

th

3

rd

2

nd

2

nd

Least Change

During Interval

-4.0%

(California)

12.9%

(California)

-0.3%

(California)

12.5%

(California)

Hawaii, which uses a prior approval system, has overseen its auto insurance market with

a consumer protection orientation for many years. We believe that the consistent implementation

of the state’s rate regulation rules has contributed to this success. We will further investigate

Hawaii’s effective consumer protection in future research.

Auto Insurance Regulation - What Works 2019 | Consumer Federation of America 24

C. Americans Have Overpaid for Auto Insurance by $1 Trillion Since

1989. With Better Regulation They Could be Saving $60 Billion per

Year.

In this report we calculate the amount of money that Californians have saved since 1989

when voters imposed a prior approval regulation system on its auto insurance market. To do that,

we calculate how much more drivers would pay for coverage had California voters not veered

off the highway to high prices that California and the nation was on. If California premiums

simply followed the rate increases endured by the country as a whole since 1989, that would

have cost Californians $154 billion more. But what if we invert that calculation and imagine how

much would be saved by drivers if all other states had also adopted the California approach back

in 1989?

As Figure 18 shows, we calculate that in 2015 premiums across the country would have

been $59.8 billion lower had other states employed a regulatory system that provides results that

followed California’s consumer protection trajectory.

Figure 18. Theoretical Annual Consumer Savings (in Millions) if State Adopted

California-Style Oversight

States

Savings

State

Savings

State

Savings

Alabama

$909

Kentucky

$1,230

North Dakota

$200

Alaska

$139

Louisiana

$1,768

Ohio

$1,670

Arizona

$876

Maine

$125

Oklahoma

$1,091

Arkansas

$753

Maryland

$1,198

Oregon

$880

California

N/A

Massachusetts

$1,038

Pennsylvania

$1,326

Colorado

$1,134

Michigan

$3,973

Rhode Island

$231

Connecticut

$536

Minnesota

$1,096

South Carolina

$1,115

Delaware

$349

Mississippi

$641

South Dakota

$250

Dist. Of Columbia

$74

Missouri

$1,157

Tennessee

$1,241

Florida

$6,437

Montana

$272

Texas

$6,856

Georgia

$2,235

Nebraska

$583

Utah

$670

Hawaii

$7

Nevada

$628

Vermont

$90

Idaho

$254

New Hampshire

$92

Virginia

$1,651

Illinois

$1,901

New Jersey

$886

Washington

$1,617

Indiana

$897

New Mexico

$414

West Virginia

$510

Iowa

$613

New York

$4,651

Wisconsin

$907

Kansas

$722

North Carolina

$1,755

Wyoming

$182

Auto Insurance Regulation - What Works 2019 | Consumer Federation of America 25

When we extend that hypothetical further and capture the total savings that would have

accrued over the 27-year period since 1989, we reach a total of $940 billion in savings across the

country. Put differently, American drivers have overpaid for auto insurance for the past three

decades to the tune of nearly one trillion dollars simply because their state has not been

regulating in a strong and effective manner.

IV. Recommendations and Conclusion

Americans spend nearly two hundred billion dollars on auto insurance each year, a

significant portion of which is spent on liability coverage that state laws require drivers to

purchase. Given the size of this market, and the unique circumstances stemming from the

government mandate to buy insurance, policymakers and regulators should carefully and

regularly assess the efficacy of the laws and regulations that govern auto insurance.

In this report, as we have in prior reports, we track the changes in auto insurance rates,

competitiveness, and profits in each state in order to evaluate approaches to regulation and

identify best practices. The data show that states requiring insurance companies to receive

approval for rate changes prior to implementing them get better results for consumers – a slower

pace of increases – than states with looser rules regarding hiking rates on customers. Further,

prior approval states rank, on average, as generally more competitive than states operating under

less regulatory scrutiny. Insurance company profits in prior approval states are marginally higher

than the national average, which makes it difficult for insurers to argue that regulation is bad for

business.

In particular, California’s robust consumer protection rules, which are built on a rigorous

prior approval system, has consistently yielded the best results for consumers. Complementing

California’s prior approval rate structure are a series of laws and regulations that incentivize safe

driving and reduce discrimination. We note, as well, that California’s Department of Insurance

has generally taken a pro-active approach to its responsibilities under the law, which sets

California apart from many other states, including many with prior approval systems but less

consumer-friendly results.

As policymakers and regulators look for ways to ensure the most protection for their own

constituents, the California experience offers significant support for adopting a strong consumer

protection approach to the insurance market. This approach includes,

• a prior approval approach to rate setting;

• incentivizing safe driving and loss reduction by requiring that customer premiums rely

primarily on driving-related factors such as driving record and miles driven annually;

• preventing the pass through to consumers of inefficient company costs, such as bloated

executive salaries, fines and penalties, and lobbying expenses;

Auto Insurance Regulation - What Works 2019 | Consumer Federation of America 26

• support for consumer involvement in the rate setting process; and

• full transparency in the ratemaking process.

As states around the country have long-maintained the policy of mandating the purchase

of auto insurance, it is incumbent upon states to adopt best practices to ensure that coverage is

priced in a fair and reasonable manner. This and prior research confirm that the question of how

to best keep auto insurance rates down has been answered, and it is up to policymakers and

regulators to implement these lessons.

Auto Insurance Regulation - What Works 2019 | Consumer Federation of America 27

APPENDIX

1. Average Expenditure and Liability Average Premium (1989, 2015)

State

Average Expenditure

Liability Average

Premium

1989

2015

1989

2015

Alabama

$426.30

$722.89

$203.37

$394.21

Alaska

$560.27

$872.39

$330.64

$539.68

Arizona

$581.42

$843.92

$393.06

$508.76

Arkansas

$364.68

$736.43

$203.53

$394.13

California

$747.97

$841.45

$519.39

$489.86

Colorado

$515.31

$857.44

$317.43

$520.04

Connecticut

$740.02

$1,048.56

$473.31

$650.94

Delaware

$574.04

$1,145.66

$378.71

$799.30

Dist. Of Columbia

$796.72

$1,190.39

$465.93

$626.82

Florida

$610.21

$1,185.25

$420.61

$857.64

Georgia

$531.01

$896.50

$324.93

$557.38

Hawaii

$673.36

$764.72

$467.87

$458.54

Idaho

$348.31

$573.83

$203.02

$344.29

Illinois

$505.32

$803.64

$272.18

$446.72

Indiana

$426.29

$666.24

$236.17

$382.68

Iowa

$315.02

$599.03

$167.39

$229.18

Kansas

$340.76

$698.45

$179.90

$358.24

Kentucky

$375.71

$801.97

$219.63

$529.21

Louisiana

$571.96

$1,231.77

$375.19

$775.83

Maine

$434.84

$617.73

$237.00

$338.87

Maryland

$646.18

$1,016.81

$429.18

$609.74

Massachusetts

$728.39

$1,058.50

$426.77

$606.04

Michigan

$550.84

$1,231.39

$251.73

$795.32

Minnesota

$460.41

$787.74

$294.95

$456.82

Mississippi

$440.80

$827.31

$237.92

$460.50

Missouri

$430.05

$745.04

$233.33

$415.88

Montana

$336.04

$692.50

$198.36

$386.29

Nebraska

$284.86

$681.54

$148.96

$363.63

Nevada

$586.60

$985.39

$393.56

$681.56

New Hampshire

$609.13

$775.03

$320.65

$400.56

New Jersey

$982.93

$1,265.69

$649.73

$869.57

New Mexico

$443.76

$762.56

$266.51

$488.03

New York

$665.07

$1,234.84

$387.42

$804.51

Auto Insurance Regulation - What Works 2019 | Consumer Federation of America 28

North Carolina

$388.00

$665.37

$248.85

$359.42

North Dakota

$283.11

$637.54

$150.45

$298.18

Ohio

$447.73

$702.59

$255.37

$397.11

Oklahoma

$399.19

$823.51

$218.04

$461.01

Oregon

$466.29

$828.03

$295.33

$584.13

Pennsylvania

$646.03

$878.18

$438.89

$499.06

Rhode Island

$725.82

$1,147.95

$407.83

$759.80

South Carolina

$494.25

$853.53

$311.49

$527.09

South Dakota

$273.51

$615.78

$140.77

$300.22

Tennessee

$423.26

$737.59

$215.93

$413.91

Texas

$497.35

$934.22

$292.92

$528.53

Utah

$385.44

$784.10

$217.89

$497.53

Vermont

$423.43

$680.18

$212.99

$343.12

Virginia

$437.87

$750.85

$276.57

$425.61

Washington

$490.50

$884.24

$316.86

$596.67

West Virginia

$437.09

$855.25

$253.49

$491.83

Wisconsin

$392.46

$664.81

$225.83

$374.37

Wyoming

$318.28

$656.64

$152.84

$321.04

Countrywide

$551.95

$889.01

$339.82

$538.73

2. Average Return on Net Worth (1989-2016)

State

RONW

State

RONW

State

RONW

Alabama

8.39%

Kentucky

4.52%

North Dakota

9.21%

Alaska

9.80%

Louisiana

2.63%

Ohio

10.83%

Arizona

8.86%

Maine

13.04%

Oklahoma

6.24%

Arkansas

6.25%

Maryland

9.61%

Oregon

10.83%

California

10.46%

Massachusetts

7.50%

Pennsylvania

7.89%

Colorado

6.29%

Michigan

3.45%

Rhode Island

10.44%

Connecticut

10.86%

Minnesota

9.88%

South Carolina

3.11%

Delaware

6.29%

Mississippi

5.06%

South Dakota

6.67%

Dist. Of Columbia

12.79%

Missouri

8.04%

Tennessee

7.46%

Florida

5.47%

Montana

6.82%

Texas

6.26%

Georgia

5.25%

Nebraska

7.10%

Utah

10.11%

Hawaii

16.63%

Nevada

3.09%

Vermont

12.13%

Idaho

11.74%

New Hampshire

12.54%

Virginia

10.11%

Illinois

8.97%

New Jersey

6.71%

Washington

7.98%

Indiana

8.93%

New Mexico

9.80%

West Virginia

6.75%

Iowa

9.62%

New York

8.40%

Wisconsin

9.48%

Kansas

7.42%

North Carolina

6.46%

Wyoming

9.58%

Auto Insurance Regulation - What Works 2019 | Consumer Federation of America 29

3. Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) by State

State

HHI

State

HHI

State

HHI

Alabama

1183

Kentucky

1164

North Dakota

741

Alaska

1749

Louisiana

1667

Ohio

854

Arizona

863

Maine

703

Oklahoma

1067

Arkansas

1085

Maryland

1322

Oregon

976

California

723

Massachusetts

1092

Pennsylvania

1008

Colorado

940

Michigan

1006

Rhode Island

1012

Connecticut

770

Minnesota

1116

South Carolina

1153

Delaware

1299

Mississippi

1153

South Dakota

819

Dist. Of Columbia

1928

Missouri

1038

Tennessee

1066

Florida

1191

Montana

1085

Texas

839

Georgia

1003

Nebraska

999

Utah

786

Hawaii

1393

Nevada

900

Vermont

760

Idaho

822

New Hampshire

786

Virginia

1038

Illinois

1335

New Jersey

1016

Washington

825

Indiana

938

New Mexico

1038

West Virginia

1319

Iowa

1011

New York

1504

Wisconsin

946

Kansas

902

North Carolina

887

Wyoming

1208

4. Other Data Reviewed (Table 1)

State

% in Residual

Market (2015)

%

Uninsured

(2015)

Average

Auto Repair

Costs (2013)

Liability

Regime

Seat Belt Law

Maximum

Speed

Limit

Alabama

0.00%

18.4

$2,671

tort

Primary (P)

70

Alaska

0.00%

15.4

$3,049

tort

P

65

Arizona

0.00%

12.0

$2,368

tort

Secondary (S)

75

Arkansas

0.00%

16.6

$3,100

add-on

P

70

California

0.04%

15.2

$2,289

tort

P

70

Colorado

0.00%

13.3

$2,658

tort

P

75

Connecticut

0.01%

9.4

$3,046

tort

P

65

Delaware

0.00%

11.4

$2,436

no fault

P

65

Dist. Of Columbia

0.12%

15.6

$1,747

no fault

P

55

Florida

0.00%

26.7

$2,452

no fault

P

70

Georgia

0.00%

12.0

$2,364

tort

P

70

Hawaii

0.69%

10.6

$1,951

no fault

P

60

Idaho

0.00%

8.2

$2,883

tort

S

80

Illinois

0.01%

13.7

$2,600

tort

P

65

Auto Insurance Regulation - What Works 2019 | Consumer Federation of America 30

Indiana

0.00%

16.7

$2,611

tort

P

70

Iowa

0.00%

8.7

$2,736

tort

P

70

Kansas

0.13%

7.2

$2,871

no fault

P

70

Kentucky

0.03%

11.5

$2,498

no fault

P

70

Louisiana

0.00%

13.0

$2,838

tort

P

70

Maine

0.00%

4.5

$2,378

tort

P

75

Maryland

2.25%

12.4

$2,272

add-on

P

65

Massachusetts

2.63%

6.2

$2,297

no fault

S

65

Michigan

0.20%

20.3

$2,474

no fault

P

70

Minnesota

0.00%

11.5

$2,646

no fault

P

70

Mississippi

0.00%

23.7

$2,526

tort

P

70

Missouri

0.00%

14.0

$2,565

tort

S

70

Montana

0.00%

0.1

$3,218

tort

P

75

Nebraska

0.00%

6.8

$3,145

tort

S

75

Nevada

0.00%

10.6

$2,291

tort

S

75

New Hampshire

0.04%

9.9

$2,236

tort

P

65

New Jersey

1.00%

14.9

$2,783

no fault

P

65

New Mexico

0.00%

20.8

$2,539

tort

P

75

New York

0.91%

6.1

$3,278

no fault

P

65

North Carolina

31.04%*

6.5

$2,243

tort

P

70

North Dakota

0.00%

6.8

$2,797

no fault

P

75

Ohio

0.00%

12.4

$2,514

tort

S

70

Oklahoma

0.00%

10.5

$2,971

tort

P

75

Oregon

0.00%

12.7

$2,251

tort

P

65

Pennsylvania

0.08%

7.6

$2,542

no fault

S

70

Rhode Island

3.33%

15.2

$3,325

tort

P

65

South Carolina

0.00%

9.4

$2,261

tort

P

70

South Dakota

0.00%

7.7

$3,187

add-on

P

75

Tennessee

0.00%

20.0

$2,665

tort

S

70

Texas

0.02%

14.1

$2,595

tort

P

70

Utah

0.00%

8.2

$2,502

no fault

P

75

Vermont

0.04%

6.8

$2,500

tort

S

65

Virginia

0.02%

9.9

$1,927

tort

S

70

Washington

0.00%

17.4

$2,394

add-on

P

70

West Virginia

0.00%

10.1

$2,834

tort

S

70

Wisconsin

0.00%

14.3

$2,601

add-on

P

65

Wyoming

0.00%

7.8

$3,356

tort

S

75

* NC data reflect state’s reinsurance facility, which is not a traditional residual market.

Source: NAIC Auto Insurance Database Report 2014/15, except Residual Market Data uses NAIC and

AIPSO data, and uninsured data are from Insurance Research Council Uninsured Motorists, 2017 Edition

Auto Insurance Regulation - What Works 2019 | Consumer Federation of America 31

5. Other Data Reviewed (Table 2)

State

Traffic

Density

(2015)*

Urban Residents as

% of Population

(2010)**

Disposable per

Capita Income (000s)

(2014)^

Car Thefts per

1,000 Vehicles

(2014)^

Alabama

0.64

71.5%

$34

1.93

Alaska

0.31

67.4%

$50

2.26

Arizona

0.95

92.5%

$34

3.25

Arkansas

0.33

60.3%

$34

2.09

California

1.48

97.7%

$44

5.45

Colorado

0.55

86.3%

$44

2.71

Connecticut

1.45

91.4%

$56

2.2

Delaware

1.50

78.0%

$40

1.37

Dist. Of Columbia

2.35

100.0%

$60

11.47

Florida

1.64

91.4%

$38

2.85

Georgia

0.87

81.0%

$35

3.38

Hawaii

2.29

70.1%

$42

2.87

Idaho

0.33

65.6%

$34

0.98

Illinois

0.72

87.0%

$42

1.74

Indiana

0.82

78.3%

$36

2.39

Iowa

0.28

56.5%

$40

1.22

Kansas

0.22

68.3%

$42

2.82

Kentucky

0.60

58.2%

$33

1.56

Louisiana

0.79

74.6%

$38

2.62

Maine

0.62

58.4%

$37

0.7

Maryland

1.76

94.6%

$47

3.34

Massachusetts

1.58

99.6%

$50

1.7

Michigan

0.80

81.3%

$36

2.69

Minnesota

0.41

74.9%

$43

1.68

Mississippi

0.52

81.3%

$36

2.22

Missouri

0.54

74.5%

$37

3.16

Montana

0.16

35.2%

$36

1.46

Nebraska

0.21

58.7%

$43

2.35

Nevada

0.21

90.1%

$36

4.7

New Hampshire

0.80

62.2%

$48

0.69

New Jersey

1.92

100.0%

$50

1.74

New Mexico

0.37

66.6%

$33

3.37

New York

1.13

91.9%

$47

1.49

North Carolina

1.02

70.3%

$35

1.77

North Dakota

0.12

48.4%

$51

1.82

Ohio

0.92

80.6%

$37

1.79

Auto Insurance Regulation - What Works 2019 | Consumer Federation of America 32

Oklahoma

1.00

64.2%

$41

3.12

Oregon

0.47

77.7%

$36

2.87

Pennsylvania

0.83

84.1%

$42

1.29

Rhode Island

1.27

100.0%

$43

2.2

South Carolina

0.65

76.5%

$33

3.31

South Dakota

0.11

45.3%

$42

1.07

Tennessee

0.76

73.4%

$37

2.36

Texas

0.23

87.8%

$41

3.35

Utah

0.60

88.6%

$34

3.51

Vermont

0.50

33.8%

$42

0.42

Virginia

1.08

86.1%

$44

1.1

Washington

0.71

87.7%

$45

4.96

West Virginia

0.49

55.7%

$32

1.27

Wisconsin

0.52

72.8%

$39

1.96

Wyoming

0.33

29.7%

$50

0.76

* Density = Millions of Miles Driven Per Mile of Road, Source: Federal Highway Administration

**Source: U.S. Census Bureau

^ Source: NAIC Auto Insurance Database Report 2014/15