SETTING

COURSE

A CONGRESSIONAL

MANAGEMENT GUIDE

EDITION FOR THE

117t h

CONGRESS

SETTING COURSE

117th

CONGRESS

SETTING COURSE, n

ow in its 17

th

edition for the 117

th

Congress, is a

comprehensive guide to managing a congressional ofce. Part I is for Members-elect

and freshman ofces, focusing on the tasks that are most critical to a successful

transition to Congress and setting up a new ofce. Part II focuses on dening the

Member’s role — in the ofce and in Congress. Part III provides guidance to both

freshman and veteran Members and staff on managing ofce operations.

Setting

Course

is the signature publication of the Congressional Management Foundation

and has been funded by grants from:

A CONGRESSIONAL

MANAGEMENT GUIDE

“The best thing a new Member and his or her staff can do is to sit

down and read Setting Course cover to cover. It’s a book that has

stood the test of time.”

—House Chief of Staff

“Setting Course is written as if you were having a conversation

with someone who has been on Capitol Hill for 50 years and knows

how things work.”

—Senate Ofce Manager

Deborah

Szekely

THE CONGRESSIONAL MANAGEMENT FOUNDATION (CMF)

is a 501(c)(3) nonpartisan nonprot whose mission is to build

trust and effectiveness in Congress. We do this by enhancing the

performance of the institution, legislators and their staffs through

research-based education and training, and by strengthening the

bridge between Congress and the People it serves. Since 1977 CMF

has worked internally with Member, committee, leadership, and institutional ofces in the House

and Senate to identify and disseminate best practices for management, workplace environment,

communications, and constituent services. CMF also is the leading researcher and trainer on citizen

engagement, educating thousands of individuals and facilitating better understanding, relationships,

and communications with Congress.

CongressFoundation.org

sponsored by

SOCIETY FOR HUMAN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT

AMerICAn LIbrAry AssoCIATIon

DEBORAH SZEKELY

Deborah

Szekely

SETTING

COURSE

has been made possible by grants from

A CONGRESSIONAL

MANAGEMENT GUIDE

EDITION FOR THE

117t h

CONGRESS

©Copyright 1992, 1994, 1996, 2000, 2002, 2004, 2006, 2008,

2010, 2012, 2014, 2016, 2018, 2020 Congressional Management Foundation

©Copyright 1984, 1986, 1988 The American University

All Rights Reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner, except for brief quotations used in critical articles or reviews,

without written permission from the Congressional Management Foundation.

Congressional Management Foundation

216 Seventh Street SE, Second Floor

Washington, DC 20003

202-546-0100

www.CongressFoundation.org

Printed in the United States of America

ISBN: 978-1-930473-24-9

i

Table of Contents

TABLE OF FIGURES ............................................................................................v

PREFACE ............................................................................................................. vii

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .....................................................................................ix

INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................... xiii

PART I: TRANSITIONING TO CONGRESS AND SETTING UP YOUR OFFICE

CHAPTER ONE:

Navigating The First 60 Days: November and December ...................................3

Importance of Setting Priorities .........................................................................4

The Critical Transition Tasks ............................................................................6

Guiding Principles for the Transition ..............................................................10

Orientation and Organizational Meetings ........................................................13

Conclusion .......................................................................................................15

Chapter Summary ................................................................................................ 16

CHAPTER TWO:

Selecting Committee Assignments .......................................................................17

Importance of Committee Assignments ...........................................................18

How the Committee Assignment Process Works .............................................18

Advice for Choosing and Pursuing Committee Assignments ..........................23

Conclusion .......................................................................................................25

Chapter Summary ................................................................................................ 26

CHAPTER THREE:

Creating a First-Year Budget ............................................................................... 27

Congressional Budget Primers ........................................................................28

The Member’s Role in Budgeting ....................................................................32

Developing a First-Year Budget ......................................................................33

Veteran Ofce Advice on Developing a First-Year Budget .............................42

Conclusion .......................................................................................................44

Chapter Summary ................................................................................................ 45

CHAPTER FOUR:

Creating a Management Structure and a System for

Communicating with the Member ...................................................................47

Selecting a Management Structure ..................................................................48

Designing a System for Member–Staff Communications ...............................55

ii

✩ ✩ ✩ ✩

SETTING COURSE

Communication Objectives .............................................................................. 57

Conducting Effective Meetings .......................................................................59

Conclusion .......................................................................................................60

Chapter Summary ................................................................................................ 61

CHAPTER FIVE:

Hiring Your Core Staff .........................................................................................63

Importance of Hiring Only a Core Staff in November and December ............64

Which Functions To Hire as Part of Your Core Staff .......................................66

Fitting Core Staff to Your Mission and Goals .................................................. 70

Hiring the Rest of Your Staff ...........................................................................71

Recruiting the Best Candidates ........................................................................ 72

A Process for Hiring the Right Staff Candidates .............................................73

Conclusion .......................................................................................................79

Chapter Summary ................................................................................................ 80

CHAPTER SIX:

Selecting and Utilizing Technology ...................................................................... 81

The Basic Congressional System .....................................................................82

Glossary of Technology-Related Ofces and Staff .........................................83

Determining When to Upgrade ........................................................................85

Critical Questions ............................................................................................87

Key Considerations ..........................................................................................88

Six Steps to Making Wise Technology Purchases ...........................................90

CMF Technology and Communications Research ..........................................91

Keeping Your System Running Smoothly .......................................................94

Conclusion .......................................................................................................97

Chapter Summary ................................................................................................ 98

CHAPTER SEVEN:

Establishing District and State Ofces ................................................................ 99

Importance of Decisions Concerning District/State Ofces .......................... 100

Selecting the Number of District/State Ofces .............................................101

Ofce Location and Space Considerations ....................................................104

Which Ofce To Open First ........................................................................... 108

Furniture and Ofce Equipment ....................................................................109

Conclusion .....................................................................................................111

Chapter Summary .............................................................................................. 112

PART II: DEFINING YOUR ROLE IN CONGRESS AND YOUR OFFICE

CHAPTER EIGHT:

Understanding the Culture of Congress: An Insider’s Guide ......................... 115

Constants in Congress ....................................................................................116

Table of Contents iii

Three Congressional Trends: Close Party Ratios, Inux of New

Members and Increased Partisanship .........................................................118

Conclusion .....................................................................................................122

Chapter Summary .............................................................................................. 123

CHAPTER NINE:

Dening Your Role In Congress ......................................................................... 125

The Importance of Dening Your Role ..........................................................126

A Discussion of the Five Roles ...................................................................... 127

Balancing Major and Minor Roles ................................................................133

Selecting Your Role .......................................................................................134

Conclusion .....................................................................................................137

Chapter Summary .............................................................................................. 138

CHAPTER TEN:

The Member’s Role as Leader of the Ofce .....................................................139

The Member as Leader ..................................................................................140

Organizational Culture ...................................................................................141

Assessing and Understanding Your Leadership Style ....................................147

How to Address the Two Common Leadership Problems .............................150

Conclusion .....................................................................................................153

Chapter Summary .............................................................................................. 154

PART III: MANAGING YOUR CONGRESSIONAL OFFICE

CHAPTER ELEVEN:

Strategic Planning In Your Ofce ...................................................................... 157

The Value of Planning ....................................................................................158

The Planning Process ..................................................................................... 160

Conducting an Effective Planning Session ....................................................162

Conclusion .....................................................................................................175

Chapter Summary .............................................................................................. 176

CHAPTER TWELVE:

Budgeting and Financial Management .............................................................177

The Strategic Importance of Budgeting .........................................................178

Budgeting Toward Your Goals, Year After Year ............................................. 181

Establishing Financial Procedures for Your Ofce ........................................ 185

Tips for House and Senate Ofces ................................................................189

Conclusion .....................................................................................................192

Chapter Summary .............................................................................................. 193

CHAPTER THIRTEEN:

A Process for Managing Staff ...........................................................................195

Rationale for a Performance Management System .......................................196

iv

✩ ✩ ✩ ✩

SETTING COURSE

Implementing a Performance Management System ......................................197

How to Run Successful Staff Performance Meetings .................................... 204

Handling Staff with Different Needs .............................................................206

Evaluating Your System .................................................................................210

Conclusion .....................................................................................................211

Chapter Summary .............................................................................................. 212

CHAPTER FOURTEEN:

Managing Constituent Communications ..........................................................213

The Growth of Constituent Communications ................................................214

CMF Research on Member-Constituent Engagement ...................................215

Assessing the Priority of Mail in Your Ofce ................................................ 216

Establishing Mail Policies .............................................................................218

CMF Model Mail System ..............................................................................220

Addressing Common Mail Issues ..................................................................227

Improving the Processing of Email ...............................................................230

Proactive Outreach Mail ................................................................................231

Conclusion .....................................................................................................233

Chapter Summary .............................................................................................. 234

CHAPTER FIFTEEN:

Strategic Scheduling ...........................................................................................235

Strategic Scheduling Dened.........................................................................236

Six Steps to Developing and Implementing a Strategic Schedule .................237

District/State Trips .........................................................................................243

The Weeks in Washington, DC ......................................................................248

Addressing Common Problems .....................................................................251

Scheduling Issues Faced by Members ...........................................................256

Conclusion .....................................................................................................260

Chapter Summary .............................................................................................. 262

CHAPTER SIXTEEN:

Managing Ethics..................................................................................................263

The Changed Ethics Environment .................................................................264

Coping with the Changed Environment ......................................................... 266

Guidelines for Managing Ethics in Congressional Ofces ............................267

The Top Five Areas of Ethical Risk ...............................................................269

Conclusion .....................................................................................................272

Chapter Summary .............................................................................................. 273

INDEX .................................................................................................................277

AUTHORS ...........................................................................................................291

ABOUT CMF ......................................................................................................295

v

Table of Figures

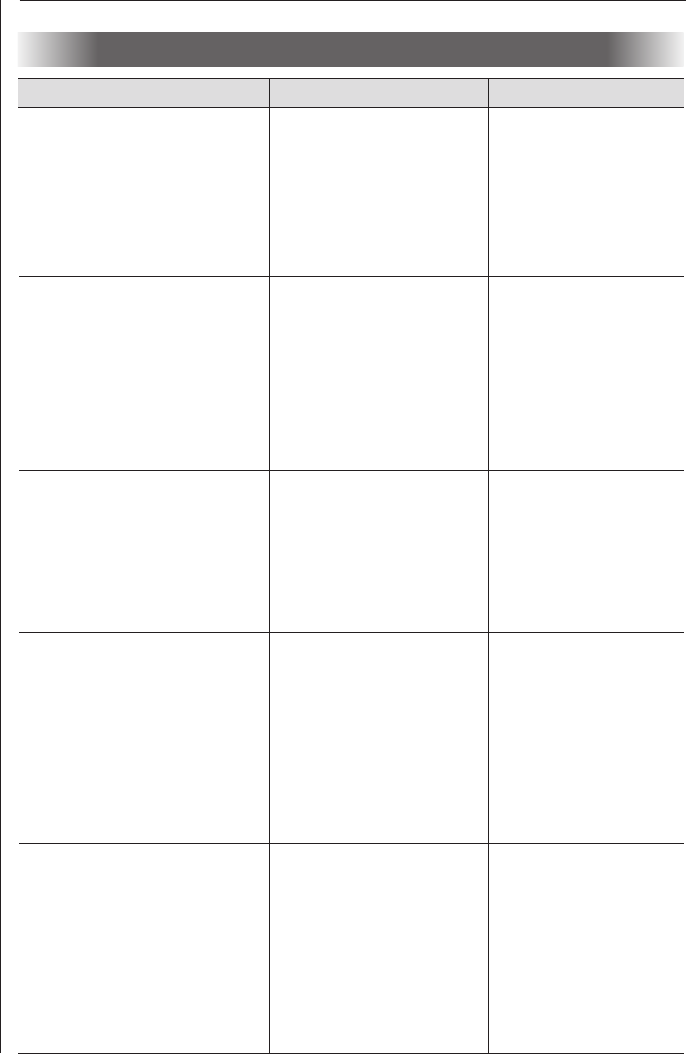

CHAPTER ONE: Navigating The First 60 Days: November and December

Figure 1-1: Urgency and Importance Matrix ....................................................5

Figure 1-2: Matrixing Typical Ofce Activities ...............................................6

CHAPTER TWO: Selecting Committee Assignments

Figure 2-1: House Committee Categories ......................................................21

Figure 2-2: Senate Committee Categories ......................................................22

CHAPTER THREE: Creating a First-Year Budget

Figure 3-1: Average Spending by Freshman House Ofces

in Their First Year ........................................................................................34

Figure 3-2: Average Salaries of Congressional Staff ......................................37

Figure 3-3: House Budget Worksheet ............................................................. 39

Figure 3-4: Senate Budget Worksheet ............................................................40

CHAPTER FOUR: Creating a Management Structure and a System for

Communicating with the Member

Figure 4-1: Model 1: Centralized Structure .................................................... 50

Figure 4-2: Model 2: Washington–District/State Parity Structure .................. 51

Figure 4-3: Model 3: Functional Structure .....................................................52

Figure 4-4: Pros and Cons of Management Structures ................................... 54

CHAPTER FIVE: Hiring Your Core Staff

Figure 5-1: Sample House Core Staff ............................................................. 68

Figure 5-2: Sample Senate Core Staff ............................................................69

CHAPTER SEVEN: Establishing District and State Ofces

Figure 7-1: District/State Ofces Maintained by Members .........................102

CHAPTER NINE: Dening Your Role in Congress

Figure 9-1: Congressional Role Selection Chart ..........................................136

CHAPTER ELEVEN: Strategic Planning in Your Ofce

Figure 11-1: Impact Achievability Grid ........................................................166

Figure 11-2: Scorecard for Goal Evaluation ................................................ 167

Figure 11-3: Sample Goal-Oriented Action Plan ..........................................169

CHAPTER THIRTEEN: A Process for Managing Staff

Figure 13-1: Five Steps of Performance Management .................................197

Figure 13-2: Sample Staff Self-Evaluation Form .........................................202

CHAPTER FOURTEEN: Managing Constituent Communications

Figure 14-1: CMF Mail System Flow Chart .................................................225

vi

✩ ✩ ✩ ✩

SETTING COURSE

CHAPTER FIFTEEN: Strategic Scheduling

Figure 15-1: Model Speech/Event Evaluation Form ....................................247

Figure 15-2: Sample Event Scheduling Form ...............................................254

Figure 15-3: How Often Members Go Home ............................................... 259

Figure 15-4: Sample Event Preparation Request Form ................................261

vii

Preface

While running for Congress in 1982, Deborah Szekely learned that no manual

existed to help new Members of Congress set up their ofces. Although

she lost the election, in commissioning this book, she discovered a valuable

way to serve the Congress. Without her enthusiasm and foresight, Setting

Course simply would not exist. In the rst edition in 1984, we predicted that

Members of Congress would be in Deborah’s debt for years to come. Thirty-

six years later, that prediction has come true. Many people have good ideas,

but few have the ability to implement them. Fortunately, Deborah excels in

transforming her ideas into projects, and her projects into successes. CMF

remains indebted to Deborah for conceiving and funding the original edition of

Setting Course and for her continued commitment to this book.

And yet, this edition comes to Congress at probably the most uncertain of

times in generations. Like all places of work, the coronavirus has upended how

Congress does its job. Starting in March 2020 through when this book was

published in October 2020, every Member, staffer, and ofce has been forced

to adapt in order to do their jobs. (To assist ofces during this crisis, CMF

created and consolidated resources into a “Coronavirus Resource Center” on

our website at CongressFoundation.org/COVID-19. From here you can access

webinars, handouts, publications, and articles on crisis management, remote

work, burnout and stress, remote town halls, and employee assistance.)

On the positive side, the Select Committee on the Modernization of

Congress in the 116

th

Congress produced 97 recommendations to improve

the House of Representatives, some which will be implemented during

the orientation of new Members in November 2020. The Committee’s

recommendations have the potential of signicantly changing ofce budgets,

technology, and the professional development of House staff. (Freshman

lawmakers and staff should refer to ofcial resources for updates on these

topics.)

Even with these changes, this edition of Setting Course follows Deborah’s

vision of providing timely, proven guidance on the fundamentals of setting

up and managing a congressional ofce. It offers ideas, models, and advice

to guide Members of Congress — whether in their rst, fourth, or tenth term.

It combines the wisdom of previous editions with new insights and updated

information for the 117

th

Congress.

CMF’s mission is “building trust and effectiveness in Congress.” Though

it may seem idealistic to some, our experience has proven that greater

effectiveness is both realistic and achievable. We believe that if Members of

viii

✩ ✩ ✩ ✩

SETTING COURSE

Congress implement the management and planning advice in this book, they

can increase their own productivity and efciency, thereby improving the

effectiveness of Congress as an institution.

We are honored that Deborah Szekely, the Society for Human Resource

Management, and the American Library Association support this mission

and enable us to continue providing the critical guidance contained in Setting

Course through their generous nancial contributions. Without their support,

this 17

th

edition would not have been possible.

As the world’s largest professional association devoted to human resource

management, SHRM, the Society for Human Resource Management, is

dedicated to promoting effective management and leadership all over the

globe. We are proud to partner with them to offer management advice and

techniques to individual House and Senate ofces through Setting Course, our

Life in Congress research project, the CMF Democracy Awards, and a variety

of professional development programs. SHRM also was the exclusive sponsor

for Keeping It Local: A Guide for Managing Congressional District and State

Ofces.

CMF welcomes a new sponsor to the publication, the American Library

Association (ALA). Founded on October 6, 1876 during the Centennial

Exposition in Philadelphia, the mission of ALA is “to provide leadership for

the development, promotion and improvement of library and information

services and the profession of librarianship in order to enhance learning and

ensure access to information for all.”

CMF is fortunate to produce Setting Course with such forward thinking

supporters of the Congress who understand the powerful link between

effective management and professional success — whether the goal is

building a thriving business and meeting customer needs or formulating

forward-looking public policy to address constituent concerns more

effectively.

Thank you.

Bradford Fitch

President & CEO

Congressional Management Foundation

ix

Acknowledgments

The Congressional Management Foundation (CMF) is indebted to many

people for their help in producing Setting Course. We warmly thank all who

contributed to its success.

Current Congressional Staff

Lynden Armstrong, Deputy Assistant Sergeant at Arms and Chief Information

Ofcer, Senate Sergeant at Arms

Brian Bean, Placement Ofce Manager, Senate Sergeant at Arms

Christopher Brewster, Administrative Counsel, Ofce of the Chief

Administrative Ofcer (CAO)

Jeff Brinkley, Technology Representative, Senate Sergeant at Arms

Richard Cappetto, Chief Customer Ofcer, Ofce of the Chief

Administrative Ofcer (CAO)

Lucretia Coles, Ofce Support Services, Senate Sergeant at Arms

Jen Daulby, Republican Staff Director, Committee on House Administration

Jamie Fleet, Staff Director, Committee on House Administration

Russell Gore, Deputy Counsel, Ofce of House Employment Counsel

Walt Herzig, District Director, Rep. Andy Levin

Christopher Hoven, Administrative Assistant, Rep. Adam Schiff

Tim Hysom, Chief of Staff, Rep. Alan Lowenthal

Teresa James, Deputy Executive Director, Ofce of Congressional Workplace

Rights

Mary Suit Jones, Assistant Secretary of the Senate

Gloria Lett, Deputy Clerk, Ofce of the Clerk

David Maddux, Congressional Staff Academy, Ofce of the Chief

Administrative Ofcer (CAO)

Charles Marshall, Communication and Technology Integration, Senate

Sergeant at Arms

Michael Modica, Customer Relations Manager, Technology Support, Ofce

of the Chief Administrative Ofcer (CAO)

Andrea Olley, Assistant State Liaison, State Ofce Operations, Senate

Sergeant at Arms

Susan Olson, Deputy Chief of Staff and General Counsel, Sen. John Boozman

Eric Petersen, Specialist in American National Government, Congressional

Research Service

Deb Powers, Financial Systems, Secretary of the Senate

Captain Kimberly Schneider, U.S. Capitol Police

Lisa Sherman, Chief of Staff, Rep. Susan Davis

x

✩ ✩ ✩ ✩

SETTING COURSE

Janice Siegel, Director of Operations, Rep. Jerrold Nadler

Kate Summers, State Ofce Operations Director, Senate Sergeant at Arms

Tracee Sutton, Deputy Chief of Staff and Legislative Director, Rep. Greg

Stanton

Wayne Weak, Technology Representative, Senate Sergeant at Arms

Kathi Wise, Scheduler/Executive Assistant, Sen. John Barrasso

Former Congressional Staff

Jackie Aamot, Director, Financial Counseling, House Finance Ofce

Bob Bean, Minority Staff Director, Committee on House Administration

Bern Beidel, Director, Ofce of Employee Assistance, Ofce of the CAO

Melissa Bennett, Scheduler, Rep. Rob Portman

Gail Bergstad, State Representative, Sens. Kent Conrad and Byron Dorgan

Wineld Boerckel, Chief of Staff/Policy Director, Rep. Gwen Moore

Steven Bosacker, Chief of Staff, Rep. Tim Penny

Dave Cape, Ofce Support Services, Senate Sergeant at Arms

Wanda Chaney, House Information Resources, Ofce of the CAO

Tamara Chrisler, Executive Director, Ofce of Compliance

Chris Chwastyk, Chief of Staff, Rep. Chet Edwards

Chick Ciccolella, Director of Information and Technology, Senate Committee

on Rules and Administration

Bernadette Connell, Ofce Support Services, Senate Sergeant at Arms

Nancy Davis, Ofce Support Services, Senate Sergeant at Arms

Debi Deimling, Executive Assistant, Rep. Mike Oxley

Chris Doby, Financial Clerk, Senate Disbursing Ofce

Michelle Donches, Budget Manager/Finance and Payroll Administrator, Rep.

Diane Black

Paula Effertz, Ofce Manager, Sen. Jay Rockefeller

Mary Sue Englund, Director of Administration and Operations, Committee

on House Administration

John Enright, Chief of Staff, Rep. Don Sherwood

Teresa Ervin, Deputy Chief of Staff, Sen. Saxby Chambliss

Margaret Fibel, Deputy for IT & Strategic Planning, Senate Disbursing Ofce

Lani Gerst, Senior Professional Staff, Senate Committee on Rules and

Administration

Todd Gillenwater, Legislative Director, Rep. David Dreier

Bill Grady, District Director, Rep. Linda Sanchez

George Hadijski, Senior Advisor, Committee on House Administration

Tina Hanonu, Assistant Chief Administrative Ofcer (CAO)

Joel Hinzman, Professional Staff, Committee on House Administration

Cathy Hurwit, Chief of Staff, Rep. Jan Schakowsky

Acknowledgments xi

John Lapp, Chief of Staff, Rep. Ken Lucas

Diane Liesman, Chief of Staff, Rep. Ray LaHood

Cathy Marder, Ofce Manager, Sen. John Ensign

Chris McCannell, Chief of Staff, Rep. Michael McMahon

Ellen McCarthy, Professional Staff, Committee on House Administration

Rachelle Mobley, House Learning Center, Ofce of the CAO

Dan Muroff, Chief of Staff, Rep. Michael Capuano

Jenny Ogle, Casework Manager, Sens. Mike DeWine and George Voinovich

Katie Patru, Deputy Staff Director, Committee on House Administration

Mary Paxson, State Scheduler/Field Representative, Sen. Craig Thomas

Robert Paxton, Chief of Staff, Secretary of the Senate

Mark Perkins, Financial Manager, Rep. Alcee Hastings

David Pike, Deputy Chief of Staff, Sen. Jeff Bingaman

Margo Rushing, Administrative Director, Sen. Conrad Burns

Alan Salazar, Senior Political and Policy Advisor, Sen. Mark Udall

Judy Schneider, Specialist on the Congress, Congressional Research Service

Reynold Schweickhardt, Director of Technology Policy, Committee on

House Administration

Joe Shoemaker, Communications Director, Senate Majority Whip Dick Durbin

Gene Smith, District Director/Press Secretary, Rep. Howard Berman

Mark Strand, Chief of Staff, Sen. James Talent

Paula Sumberg, Deputy Executive Director, Ofce of Compliance

Steve Sutton, Chief of Staff, Rep. John Kline

Jeanne Tessieri, State Ofce Liaison, Senate Sergeant at Arms

Cole Thomas, Operations Director, Sens. Mike DeWine and George Voinovich

Stacy Trumbo, Administrative Director, Sen. Craig Thomas

Jason Van Eaton, Deputy Chief of Staff, Sen. Kit Bond

Connie Veillette, Professional Staff, Senate Committee on Foreign Relations

David Vignolo, State Ofce Liaison, Senate Sergeant at Arms

Rob von Gogh, Special Projects, Ofce of the CAO

Mary Watts, House Information Resources, Ofce of the CAO

Marie Wheat, Chief of Staff, Rep. Jim DeMint

Tim Wineman, Financial Clerk, Senate Disbursing Ofce

Todd Womack, Chief of Staff, Sen. Bob Corker

Rowdy Yeates, Chief of Staff, Rep. Jim Kolbe

Former CMF Staff and Others

Beverly Bell, CMF Consultant and Trainer; former CEO of CMF; former

House Chief of Staff

Ira Chaleff, CMF Management Consultant; former CMF Executive Director

and chair emeritus of the CMF Board of Directors

xii

✩ ✩ ✩ ✩

SETTING COURSE

Christopher Deering, Interim Dean for the College of Professional Studies

and the Virginia Science & Technology Campus (VSTC) at The George

Washington University

Betsy Wright Hawkings, Select Committee on the Modernization of

Congress; former Chief of Staff, Reps. Andy Barr, Christopher Shays and

Bobby Schilling; former CMF Deputy Director

Meredith Persily Lamel, CMF Management Consultant and former Director

of Training and Consulting Services

Michael Patruznick, former CMF Director of Research

Chet Rogers, Professor Emeritus of political science, Western Michigan

University; and former House AA

Craig Schultz, former CMF Director of Research

Laura D. Scott, CMF Management Consultant and former Deputy Director

Gary Serota, former CMF Executive Director

Rick Shapiro, CMF Management Consultant and former Executive Director

Patty Sheetz, former Senior Advisor, Rep. Jeff Fortenberry; former CMF

Management Consultant

David Twenhafel, former CMF Director of Research

Don Wolfensberger, Fellow at the Bipartisan Policy Center; Congressional

Scholar at the Woodrow Wilson Center; former Chief of Staff for the House

Rules Committee

Revising a publication of this scope and magnitude is a signicant

undertaking and could not have been completed without the support and

hard work of CMF staff and research assistants. For their timely assistance

with the revision and production of this edition, I thank Brad Fitch, Kathy

Goldschmidt, Sarah Thomson, Maya Clark, and Ian Harris. Special thanks to

William Mioduszewski, who went above and beyond in the nal stages.

We must also acknowledge our predecessors. The rst three editions of

Setting Course were the joint product of The American University’s Center

for Congressional and Presidential Studies (CCPS) and CMF. We are proud

to follow in the footsteps of the outstanding staff who collaborated on these

editions: Burdett A. Loomis, Paul Light, James A. Thurber, Gary Serota, and

Ira Chaleff.

CMF has worked diligently on Setting Course to keep the guidance

accurate and relevant. However, we care deeply about improving our products

and welcome all feedback, corrections, or suggestions for the next edition.

Nicole Folk Cooper

Director of Research and Publications

Congressional Management Foundation

Editor, Setting Course (17

th

Edition for the 117

th

Congress)

xiii

Introduction

In the classic 1972 lm, The Candidate, Robert Redford portrays an idealistic

young man running for the Senate against an entrenched incumbent. The nal

weeks of the campaign are a frantic whirl of events, and no one — not the

candidate, nor the campaign team — has time for a single thought beyond

election day. Redford wins, of course — this is the movies — but on the way

to deliver his victory speech in the famous nal scene, he pulls his campaign

manager aside and asks in a daze, “What do we do now?” And credits roll.

Where The Candidate ends, Setting Course begins.

Successful careers in Congress don’t just happen; they are the result of

careful planning and management. We believe that good management and

planning techniques can be applied to congressional ofces. More specically,

well-managed ofces are more likely to achieve their political and legislative

objectives. We also believe that improving the performance of individual

ofces enhances the overall effectiveness of the Congress and strengthens the

public trust.

The need to apply management principles to a congressional ofce is

especially true for freshmen, given the extraordinary challenges they face.

Members-elect have two months from election day until swearing-in day be-

fore they are expected to be up and running — an insufcient time to nish

the massive array of tasks they must complete to become a fully functioning

House or Senate ofce. To employ the nautical metaphor of this book, cop-

ing with this shortage of time leaves freshman Members with the daunting

initial challenge of trying to sail their boats in the ocean at the same time that

they are building them. It is a demanding and dangerous task that requires

signicant management skills and courage to succeed.

Effectively setting and implementing priorities is also a discipline veteran

ofces must continually practice if they are to avoid the common congressional

hazard of working very hard but accomplishing very little. This book is

intended to help freshman and veteran Members better serve their constituents

and better serve their country. It is based on four decades of CMF research into

the best practices used by House and Senate personal ofces.

We’ve divided Setting Course into three distinct sections to meet the

needs of our different audiences. New Members and their key transition

staff can use Part I to better understand the critical transition decisions

they face in November and December and to receive guidance for making

these decisions. Part II is designed to help freshman and veteran Members

understand the culture of Congress, choose a path to success within the

xiv

✩ ✩ ✩ ✩

SETTING COURSE

institution, and become effective leaders of their ofces. Part III provides

guidance to freshman and veteran Members and their staff on managing

many of the critical functions of a congressional ofce: planning, budgeting,

managing staff, constituent communications, scheduling, and ethics.

This book has changed markedly in content and structure since the

rst edition in 1984, but the core guidance and wisdom of this book have

remained relatively unchanged. Thirty-six years ago, Setting Course was an

interesting experiment addressing the untested question: Would Members

of Congress and staff read and apply sound management guidance from a

written manual? Today, this book has become required reading for Members-

elect and a valuable desktop reference for virtually every Chief of Staff and

many veteran Members. We hope it is as helpful to you in setting your course

for your career in Congress. Enjoy the journey.

Part I:

Transitioning to Congress and

Setting Up Your Ofce

Chapter One: Navigating the First 60 Days:

November and December ........................................... 3

Chapter Two: Selecting Committee Assignments ..........................17

Chapter Three: Creating a First-Year Budget ....................................27

Chapter Four: Creating a Management Structure and a System

for Communicating with the Member ......................47

Chapter Five: Hiring Your Core Staff ..............................................63

Chapter Six: Selecting and Utilizing Technology ........................... 81

Chapter Seven: Establishing District and State Ofces ......................99

Notes a series of questions. Your unique answers can help

you make decisions about managing an ofce and a career.

Alerts you to a situation which Hill ofces have found to be

problematic. Proceed with caution and pay close attention.

Notes a concept or recommendation that CMF has determined,

through its research with congressional ofces, to be helpful.

Identies an ofce or organization which you may wish to

contact for further information on the topic.

Notes a process or steps you can use in the operations of

your ofce.

I

D

E

A

I

I

I

I

I

I

P

R

O

C

E

S

S

C

O

N

T

A

C

T

Q

U

E

S

T

I

O

N

C

A

U

T

I

O

N

Icons Used in Setting Course

CHAPTER ONE

Navigating the First 60 Days:

November and December

This Chapter Includes...

✩ A process for setting priorities during the transition

✩ Those key activities which should be your focus in

November and December

✩ Guiding principles to help you make more informed decisions

and maintain your focus during the transition

Not long ago, freshman Members of Congress could use most of the two

months between Election Day and swearing-in day for a well-deserved

vacation. Times have changed. Increasingly, what you do and don’t do

during the transition may well govern the success of your rst term, if not

your career.

You probably can (and should) nd a few days to relax with friends and

family. But only a few. Freshmen who get a late start tend to make rushed,

uninformed decisions about their ofce operations and are often unable to

rebound and demonstrate accomplishments in their rst terms.

It is equally important to recognize that you cannot do everything during

the transition, nor should you. You simply don’t have the time, resources or

information. Rather, you should identify and concentrate on the essential

tasks which will set the stage for a successful rst term. Other, non-critical

decisions should be deferred.

Part I of this book is designed to help you make these decisions and

navigate your transition to Congress.

3

4

✩ ✩ ✩ ✩

SETTING COURSE

Importance of Setting Priorities

All Members, from the newly elected to the most senior, share a common

problem. There is much more to do than can possibly be done. This is

especially true for freshmen during November and December, when it seems

you are trying to build and sail your ofce ship simultaneously.

You don’t have much time or many resources (money, staff, ofce space) at

your disposal. You probably don’t have all the information you need to make

knowledgeable decisions, or even perhaps a sense of what data would be most

helpful. Yet your responsibilities are enormous, every decision appears critical

and pressing, and the possibilities of what you could be working on are almost

limitless.

There is hope, and it begins when you accept that you and your limited

staff cannot and should not try to accomplish everything in the rst 60 days.

Some tasks are essential to your rst-term success. Countless, tempting others

will have little impact on your

effectiveness, or can be safely

delayed. It is far better to identify

the critical activities and devote

your energy to getting them

done well than to overreach,

spread your resources too thin

and get a lot done poorly or

just adequately. Your rst duty, therefore, is to set priorities and distinguish

between critical and non-critical tasks for the rst 60 days. To do so, you

need to look at how each potential task will or will not contribute to your

effectiveness as a Member.

Dr. Stephen Covey in The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People dened

effectiveness in terms of bringing about “the maximum long-term benecial

results possible.” Thus, in order to be effective, you need to know what results

you are attempting to achieve. It is possible to be very efcient at getting a lot

of things done without being effective. This applies to both you and your ofce.

For example, you could spend much of November and December

drafting personal responses to all the mail you receive. You could work

very productively on this task, but not very effectively, because it would do

very little to help you achieve “long-term benecial results.” A much more

effective approach would be for you to hire a Chief of Staff who could

then help you assemble staff, computers and supplies by January to answer

current and future mail.

“ It is far better to identify the critical activities and

devote your energy to getting them done well than

to overreach, spread your resources too thin and

get a lot done poorly or just adequately.”

CHAPTER ONE Navigating the First 60 Days: November and December 5

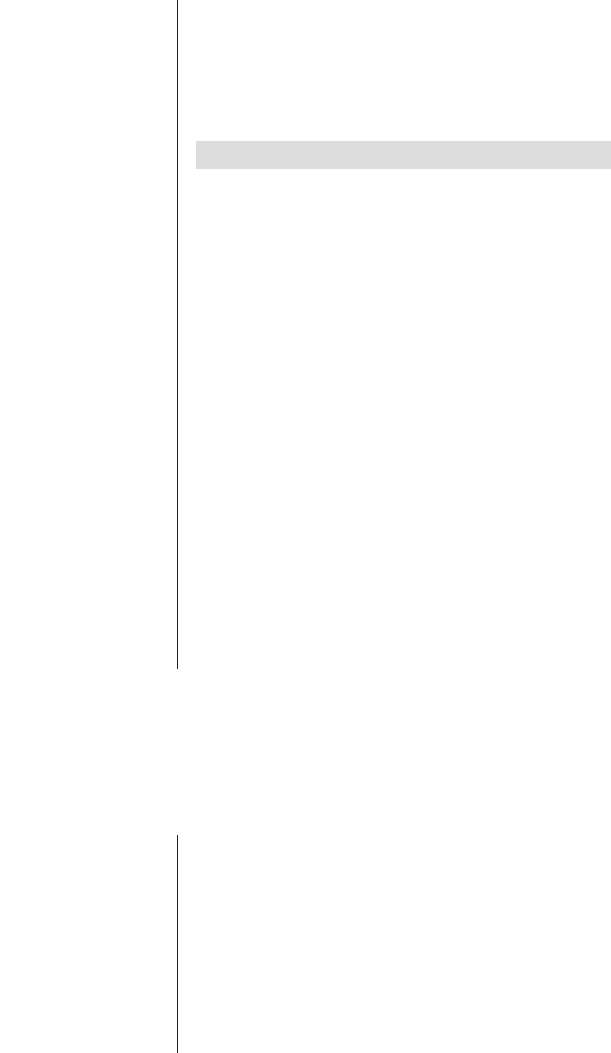

Dr. Covey used two criteria, urgency and importance, to develop a matrix

that can help you to determine where you should focus your time, energy, and

resources (see Figure 1-1).

Urgent tasks are those that need to be done right now, such as answering a

ringing telephone. Important tasks are those that contribute to the achievement

of goals and objectives. For example, selecting a good Chief of Staff is very

important to your effectiveness as a Member.

Covey argues that the most crucial quadrant for long-term effectiveness is

Quadrant II. By planning, building relations, and seeking to prevent crises, it

is possible to achieve goals and objectives. The more time spent with Quadrant

I activities — those that are urgent and important — the more you are

responding to outside pressures rather than shaping your own activities. Time

spent in Quadrants III and IV do little to contribute to long-term effectiveness.

Covey’s model can help focus new Member activity during the transition.

Figure 1-2 (on the following page) lists some of the activities in which new

Members could be engaged during the transition, and their locations in the

Covey quadrants.

By virtue of being a new Member of Congress, and representing a

constituency, you are likely to have a higher percentage of activities placed in

the urgent category, but one of the secrets to success is nding ways to reduce

the kind of crisis management involved in constantly dealing with urgent

issues. Investing time in Quadrant II activities reduces the need for crisis

management. For instance, hiring a core staff can become a crisis if you don’t

get around to it until a week before the opening of Congress, and you don’t

have a clear idea of the type of staff you need. By spending time planning,

budgeting and developing a management structure — all Quadrant II activities

— you can develop a better sense of your stafng needs. Hiring a core staff

may still be urgent, but with proper preparation it no longer has to be a crisis.

Figure 1-1

Urgency and Importance Matrix

Urgent Not Urgent

Quadrant I Quadrant II

Important Dealing with crises or handling Planning, building relations

projects with deadlines and preventing crises

Not Quadrant III Quadrant IV

Important Interruptions; some calls, Busy work; some calls

mail and meetings and mail

Figure 1-2

Matrixing Typical Oce Activities

6

✩ ✩ ✩ ✩

SETTING COURSE

It’s also important to remember that just because an activity is urgent

does not necessarily make it important. A reporter’s request for an interview

or a constituent letter both have a sense of urgency to them. A reporter has

a deadline and a constituent is expecting a reply. But are performing these

activities now contributing to your rst-term effectiveness, and is it worth

pushing aside other critical tasks in order to devote time to them? Most often

in these cases, the answer is no.

The Critical Transition Tasks

While each new Member must determine their own list of critical tasks for the

transition, there are three activities which should appear on everyone’s list.

These are the activities which will be vital to any Member’s successful man-

agement of the transition, although the amount of time, attention and resources

devoted to each may vary according to the Member’s priorities.

Critical Activity #1: Decisions About Personal Circumstances

Becoming a Member of Congress means ending one career and lifestyle and

establishing a new one. It’s like taking a new job in a new city. All of the

details involved in a move apply here as well.

Not Urgent

Important

Not

Important

Urgent

Quadrant IV

• Taking ocial photo for press kit

• Having committee sta brief

Member on upcoming legislation

• Obtaining additional oce

furniture

Quadrant III

• Responding to any routine

requests by the media

• Answering a constituent letter or

dealing with casework problems

Quadrant II

• Planning for the term

• Developing relationships with

colleagues

• Drafting a mission statement

• Creating a rst-year budget

Quadrant I

• Hiring core sta

• Seeking committee assignments

• Attending ocial orientation

programs and party organizational

meetings

CHAPTER ONE Navigating the First 60 Days: November and December 7

Most decisions regarding your personal state of affairs will be just that

— personal — and should be decided based upon your needs and those of

your family. You’ll have to leave your current job, and you’ll need a place to

stay in Washington, DC. Other circumstances will vary greatly from Member

to Member. Your spouse/partner may have to leave a job. You may need to

nd child care for your young children. You may need to resolve potential

conicts of interest regarding your investments. And you may need to let

organizations to which you belong know that your new schedule may make

it difcult to continue in the same capacity (e.g., probably unable to continue

serving on local boards or as head of the PTA).

One crucial decision that each new Member faces is whether to relocate

to Washington, DC. Members may want to keep a primary residence in the

district or state and commute to Washington during the weeks that Congress

is in session. Alternatively, they may move their families to Washington

and travel back home on weekends and during district/state work periods.

Unless your personal situation makes the choice obvious, it can be helpful

to discuss these options with freshman and veteran Members who have

already made and lived with their decisions. One word of warning: most

new Members are startled at the high cost of housing in the Washington, DC

metro area.

Personal circumstances qualify as a vital transition activity primarily

because they will contribute to, or distract from, your emotional and physical

well-being, which could signicantly inuence your job performance.

Personal decisions have the potential of consuming a large quantity of your

time and attention, so it’s worth choosing which decisions you want to make

during the transition, and which can be postponed.

Critical Activity #2: Selecting and Lobbying for

Committee Assignments

This is a critical activity for November and December because of the

signicant role committees can play in a Member’s success and because

the entire assignment process is almost always over by swearing-in day.

Committees are the primary means of moving legislation to the House

or Senate oor. They also provide an opportunity, through hearings, for

Members to bring issues to the forefront of the congressional agenda. Not

all committees are alike, however, making it imperative for a Member to

choose committees which will be able to assist in the pursuit of their goals.

Some committees are geared towards specic policy areas or regions of the

country, while others allow a Member to be more of a generalist and national

legislator. Some committees carry more clout, and others are associated with

the leadership.

MANAGEMENT FACT

In 2020, unfurnished

one-bedroom apartments

on Capitol Hill typically

cost between $1500 and

$2300 per month.

8

✩ ✩ ✩ ✩

SETTING COURSE

The formal committee assignment process begins during the orientation

and party organizational meetings held during the rst week Members are

in Washington, DC. The informal lobbying, however, often starts the day after

the election, as Members-elect jockey

for position for open committee seats

along with returning Members who

are looking to switch committees. In

December and January, the party’s

decisions are usually nalized.

We should emphasize that it

is common for Members to try to

switch panels mid-career, so while choosing and lobbying for committee

seats are critical decisions, they are not irreversible. Still, if you are clear

about your goals, it is preferable to get on the committees of your choice as

a freshman.

Chapter 2 will provide you with a comprehensive description of the

committee assignment process, and tips for selecting and lobbying for

committee seats.

Critical Activity #3: Setting Up Your Ofce

There are an incredible number of decisions which encompass the setting up

of a congressional ofce, but some decisions are clearly more important than

others. Your goal for the rst 60 days should be to determine your stafng

and equipment needs, and ofce management policies, for at least two ofces

(Washington and district/state). Accomplishing these tasks will allow you to:

(1) take care of routine business from opening day, and (2) create a foundation

that will provide a smooth climb to a fully functioning operation that reects

your values and priorities, and is capable of accomplishing the strategic objec-

tives you’ve set for your rst term.

We have identied ve tasks that are necessary for setting up a congression-

al ofce. We’ll only briey describe them here, as they are covered in greater

detail in Chapters 3-7. The ve critical tasks are:

Creating a rst-year budget (see Chapter 3). Many of the major decisions

you’ll make in the rst 60 days, such as hiring a core staff and establishing

district/state ofces, will have budget implications. Without a budget, you’ll

have a difcult time allocating your resources in a way that will help you

reach your goals. With a budget, you’ll be able to test whether your goals are

feasible, and make educated trade-offs to stay true to your priorities.

Creating a management structure and method of communicating

between staff and Member (see Chapter 4). A freshman ofce cannot be

effective unless the Member and staff have a clear, shared understanding of

“ The formal committee assignment process

begins during the orientation and party

organizational meetings held during the rst

week Members are in Washington, DC.”

CHAPTER ONE Navigating the First 60 Days: November and December 9

how the ofce will operate: who has decision-making authority and over

what issues, who supervises whom, and how staff and the Member should

communicate with each other. Unless these choices are made in November

and December, staff will be hired without a clear understanding of their

roles in the ofce. Down the line, ad hoc policies will evolve that create staff

confusion and frustration, impair productivity and diminish accountability.

Hiring a core staff (see Chapter 5). Your staff will be your most

valuable resource, greatly inuencing your success in Congress and ability

to accomplish what you set out to do. You will need a core staff on opening

day that can keep your Washington and district/state ofces functioning:

answering phones, responding to mail, scheduling your time, performing

basic legislative research, preparing speeches and talking points, and

processing casework. You’ll also want this staff to bring the skills and

expertise necessary to help you accomplish your longer-term goals.

Evaluating your technological needs (see Chapter 6). Technology is

a necessity in today’s fast-paced, information-based world of Congress.

Computer equipment that is inadequate will hurt ofce productivity and

may not even allow your staff to keep up with routine business. Depending

upon your predecessor’s purchases, the equipment you inherit may be top-

notch, barely sufcient or somewhere in between (if something doesn’t meet

minimal standards, you won’t even be allowed to inherit it). You should

evaluate this equipment in November and December to see if it will meet your

most immediate needs. If it won’t, you’ll want to minimize the disruption to

your ofce by being ready on opening day to place your order to upgrade.

Establishing district or state ofces (see Chapter 7). Most House

Members have one or two district or state ofces while the majority of

Senators have between four and six. While veterans say that it is important

to establish one district/state ofce by the rst day of the new Congress — to

demonstrate that you’re “open for business” — it is also important to draw up

the plans for all of your proposed ofces by the time you’re sworn-in. How

many ofces you’ll eventually want, where you’ll locate them, and the work

you’ll expect to be performed out of them, will impact your early decisions

on budgeting, management structure, stafng and technology purchases. Also,

many decisions regarding district/state ofces are difcult to reverse (or at

least not without political or nancial penalties) if you later discover they do

not contribute to achieving ofce goals or do not t into a larger game plan.

Planning now will save time and money later.

Of course, setting up your ofces and deciding which committee assign-

ments to pursue will require some basic understanding of how Congress

operates, both formally (rules/regulations) and informally (norms/practices).

You will likely be guring out “how the place works” well into your rst

10

✩ ✩ ✩ ✩

SETTING COURSE

year. In the short term, your best sources of information will be orientation

programs run by the House/Senate and your party’s leadership. CMF strongly

recommends that you and an aide attend these orientations. You can also pick

up quite a bit of advice by talking with veteran Members and their Chiefs of

Staff. We provide an overview of the orientation and early party organizational

meetings later in this chapter. Chapter 8 in Part II will provide Members-elect

with helpful background information on the culture of Congress, which will

assist you in both pursuing committee assignments and setting up your ofce.

Guiding Principles for the Transition

Develop and Base Decisions Around Your Strategic Goals

As we discuss throughout this book, one of the common attributes of

successful Members is the ability to set clear goals and develop a workable

plan for achieving them. Without clear priorities, ofces quickly become

overwhelmed with the pressures of work and events. Members become crisis

managers putting out an endless series of res with little time to actually

decide upon, or pursue, their priorities.

Many Members-elect make the mistake of deciding that they can put off

planning until later in the year when they have completed the Herculean

activities described earlier. More often than not, they end up making a range

of critical decisions in November and December with too little strategic

thought about their long-term effects. The result can be regrettable decisions;

regrettable because many of these early decisions cannot be easily rectied if

it turns out you need to change course. Planning should precede or accompany

decisions such as:

• Which committee assignments to seek

• Who you should hire for your key staff positions (i.e., your strategic

plan will inuence how you decide to staff your ofces: Should you

hire an outstanding Communications Director or an outstanding

Legislative Director? Four Legislative Assistants and two Constituent

Services Representatives, or the reverse?)

• How many district/state ofces you should open and where you

should locate each one

Developing goals for your rst term requires that you consider three

primary factors: your personal interests; the interests or needs of your district/

state; and the electoral environment within which you are operating. Your

goals should be targeted to achieve strategic ends that you intend to achieve,

C

A

U

T

I

O

N

CHAPTER ONE Navigating the First 60 Days: November and December 11

such as becoming a national leader on medical fraud issues or being seen

throughout the district as the champion for addressing a sewage treatment

problem. And because goals are the

top strategic priorities of the ofce,

you should have no more than six.

Any more indicates that you have

failed to make the hard trade-offs,

leaving you with too many priorities

to pursue effectively.

With clear goals established

early on in your transition, you

will be in a much better position to make wise decisions about setting up your

ofces and positioning yourself for a successful rst term. Freshmen should

also read Chapter 11, “Strategic Planning in Your Ofce” in Part III of this

book. There you’ll nd a complete discussion about planning, as well as a

step-by-step process for setting and evaluating goals.

Recognize: “Less is More”

You will quickly discover that the critical activities we discussed earlier do

not come close to encompassing the potential tasks to which you could be

devoting time and energy during the rst 60 days. In fact, we routinely use

as an orientation training tool a list of more than 60 possible tasks Members-

elect and their aides can undertake during the transition. All seem urgent and

important, and that’s where you can get tripped up.

The reality is that only a handful of tasks need to receive the bulk of your

attention in November and December because they are critical to your rst

term. The topics in Part I of this book cover most of them. You may add a few

more to reect your specic goals and priorities. But remember, the more

items on your list, the less likely you are to accomplish any of them.

We’re not saying that you should ignore the other tasks, but rather that you

should keep a sense of perspective. You don’t need to spend weeks organizing

the VIP list, or selecting the catering and souvenirs for your swearing-in

party. Similarly, it is probably not worth devoting heavy resources to scouting

the best DC ofce suite available through the “ofce lottery.” You’ll have a

swearing-in party and select an ofce, to be sure, but neither a memorable

bash nor a prime ofce location will have much effect on whether you’re a

successful rst-term Member.

By keeping your attention focused and doing the essential tasks well, you

can lay the foundation for later achievements. If one of your goals is to be a

leader on veterans issues, for instance, you may see good reason to spend time

during the transition drafting related legislation so it can be introduced on

C

A

U

T

I

O

N

“ Developing goals for your rst term requires

that you consider three primary factors:

your personal interests; the interests or

needs of your district/state; and the electoral

environment within which you are operating.”

12

✩ ✩ ✩ ✩

SETTING COURSE

opening day. Or maybe you’d want to get together

your biography and ofcial photo so you can

hand them out when veterans visit. But neither of

these activities is the best use of your time.

You will be much more effective in the

long-run by thoughtfully and strategically

completing critical tasks such as creating a

rst-year budget, hiring a quality core staff and

evaluating your technological needs. With this

groundwork, you’ll be in a position not only to

introduce legislation, but to promote it and guide

it through Congress. You will not only have

material available when veterans visit, but you

will be able to use technology to reach them.

Learn to Delegate

A nal consideration as you think about what needs to be done is who should

get it done. New Members are often reluctant to delegate, but being effective

requires it. Delegating involves identifying which tasks should be performed

by the Member, and which can be entrusted to staff. It also entails creating a

reporting or communications structure that allows the Member to oversee and

direct the transition staff without actually having to do the work.

Certain activities should only be done by you, the Member, or by a Member

with staff input. These include setting rst-term strategic goals; selecting a Chief

of Staff; deciding which committee assignments to seek and lobbying for them;

attending Member orientations and party caucuses; deciding how many district/

state ofces to open and where to

locate them; and deciding on an

ofce management structure. In

contrast, many other tasks can easily

be delegated to competent staff.

These tasks include: sorting through

resumes, invitations and casework

requests; working with House and Senate support ofces to negotiate a district/

state ofce lease; evaluating your inherited equipment and determining whether

to upgrade; and coordinating your swearing-in celebration and Washington, DC

ofce suite selection.

You’ll need a transition team for the rst two months, at which time you’ll be

able to bring your core staff on the payroll. Two to four aides should be enough.

The single most valuable aide would be someone whom you trust, and who

can be designated as the transition team leader. This person can attend some

Early Member Tasks

• Decide rst-term

strategic goals

• Select Chief of Staff

• Target/lobby for

committee assignments

• Attend orientation and

party caucuses

• Determine number and

location of district ofces

• Set up ofce management

structure

■

“ Certain activities should only be done by you,

the Member, or by a Member with staff input.

In contrast, many other tasks can easily be

delegated to competent staff.”

CHAPTER ONE Navigating the First 60 Days: November and December 13

orientation programs, contribute to strategic planning, and manage the details of

setting up your ofce. They also can assist with media requests, and you should

consider whether they are someone who can speak for you, on your behalf.

Ideally, you would pick someone who would eventually become your Chief

of Staff. The second most useful person on the team would be someone with

administrative skills to manage requests and the schedule (you will be inundated

with invitations, resumes, and messages), and provide personal assistance to you

and the transition team leader.

You’ll have to decide how to compensate transition staffers. Senators may

put only two staffers on the payroll during the transition, while the House is

currently exploring the option of paying designated aides for Members elected

in 2020. You also can recruit volunteers or pay some or all of your transition

staff out of campaign funds. Volunteers are free, but they may have competing

demands and loyalties that limit their ability to give you their complete

attention. On the other hand, using campaign funds enables you to quickly

assemble a team exclusively dedicated to serving your needs. However, you

may have to defend your choice to spend these funds for something other than

their original purpose.

Finally, as you delegate during the transition, you’ll need a system that

ensures decisions are being made in accordance with your wishes. No single

system will work for everyone. One Member-elect had his transition team

leader provide daily memos. Other Members-elect relied upon oral briengs

every few days. The key factor is your level of comfort and condence that

tasks are being carried out pursuant to your goals and priorities. Develop

a simple reporting or communications structure that meets your need for

information without bogging down the decision-making process.

Orientation and Organizational Meetings

At separate House and Senate orientations, new Members are provided

handbooks that describe the ofcial rules they must follow in setting up their

ofces and conducting their business. Presentations amplify and expand upon

the written materials. The topics usually covered in these sessions include:

budgets allocated to hire staff and run your ofce; use of the congressional

frank; use of and rules regarding hardware, software, and social media;

emergency preparedness protocols and the security and protection provided

by the U.S. Capitol Police; internal congressional services and ofces (such

as the Attending Physician); employment benets; and congressional ethics.

Additional sessions describe legislative branch support ofces (such as the

14

✩ ✩ ✩ ✩

SETTING COURSE

Congressional Research Service), introduce and explain the duties of the

ofcers of the chamber, and discuss options for setting up a congressional

ofce. Each chamber provides its new Members with tours of their chamber,

while the House also conducts training on its electronic voting system.

Orientation programs are generally taught by Members in each chamber

and are helpful in providing “lessons learned.” Social events are also held for

both Members and their spouses. These orientation programs provide new

Members with their rst opportunity to make impressions on their colleagues

and to begin the important process of establishing coalitions. It is also one

of the few times that party leaders will both make presentations and provide

new Members the opportunity to ask questions.

While the Members-elect are at their orientation meetings, the “designated

aides” accompanying the new Members to Washington receive their own

specialized training overseen by the Committee on House Administration. The

Congressional Management Foundation (CMF) participates in this training

program, and our programming focuses on the critical tasks in setting up an

ofce between November and January.

CMF also works in conjunction with

the House Chiefs of Staff Association

to connect the incoming staffers with

freshman and veteran Chiefs of Staff.

Immediately following orientation,

which usually lasts two or three days,

veteran Members join the freshmen for

early organizational meetings, which

are conducted independently by each

party in each chamber. Whereas the

ofcial orientation provides general

information, the party leadership

programs are more likely to provide

Members with advice on how to

effectively use available resources to

meet political objectives. This program

is more partisan in nature, as party

positions and strategies are decided.

The culmination of the orientation

and early organizational meetings are

party organizing meetings, at which

the organization of the new session

of Congress is determined. During

these meetings, the parties select

CMF Assistance During Your

Transition to Congress

Every election year, the Congres-

sional Management Foundation

(CMF) undertakes several initiatives

aimed at helping Members-elect

successfully transition to Congress.

First, CMF provides every new

Member with this book, Setting

Course, our signature publication.

Then, CMF joins with the

Committee on House Administration

to provide training to the aides

of Members-elect on the most

important transition tasks between

November and January.

At this orientation, the designated

aides also receive copies of CMF's

90-Day Roadmap to Setting Up

A Congressional Ofce, an easy-

to-follow guide on how to spend

your time and resources during this

critical time.

For more information on CMF's

transition resources and materials,

please contact us at 202-546-0100

or visit our New Member Resource

Center, found on our website at:

https://CongressFoundation.org/

New-Member

■

C

O

N

T

A

C

T

CHAPTER ONE Navigating the First 60 Days: November and December 15

their oor leaders and committee leaders, and begin the process of making

appointments to committees. Social events held during this period offer

Members, particularly new Members, valuable opportunities to interact with

senior Members and party leaders.

Outside organizations also conduct policy-oriented programs, primarily

for new Members. In the past, organizations such as the Congressional

Research Service (CRS), the American Enterprise Institute, the Heritage

Foundation, and the Institute of Politics at Harvard Kennedy School all held

seminars in December and January. These programs focus on policy and

ideological topics facing the new Congress. In addition, the CRS program

covers legislative and budget procedures.

Conclusion

Managing the rst 60 days after the election is the rst real test for a new

Member of Congress. Your decisions and choices during the transition will

have a long-lasting impact on your rst term, and quite possibly your career.

You must recognize that some tasks will be critical to overall rst-term

effectiveness; these should receive the bulk of your attention and resources.

You should also develop a handful of goals to guide your early decisions.

Thoughtful decisions now can save time and resources later, and start you

down the path towards achieving your objectives. And, nally, you should put

together a transition team and delegate certain prescribed tasks to them.

The other chapters in Part I take a closer look at the critical tasks we’ve

identied in this chapter and provide advice on how best to accomplish them.

We’ll examine selecting and pursuing committee assignments, creating a rst-

year budget, creating a management structure and method of Member-staff

communication, hiring a core staff, evaluating your technological needs and

establishing district/state ofces. We hope this advice will allow you to chart a

course toward a successful rst term.

16

✩ ✩ ✩ ✩

SETTING COURSE

Chapter Summary

The DO's and DON’Ts of

Navigating the First 60 Days: November

and December

Do...

Don’t...

•

concentrate most of your energy on

three critical activities:

– making decisions about your living and

other household arrangements;

– selecting and lobbying for committee

assignments; and

– setting up your oce.

•

use your strategic goals to shape critical

early decisions, such as:

– creating a rst-year budget;

– establishing/selecting a management

structure;

– hiring a core sta;

– evaluating your technology needs; and

– establishing a district or state oce(s).

•

learn to delegate. A Member should focus

on those tasks which only they can perform,

and delegate the rest to sta.

•

try to do everything. Set priorities so

you can do essential tasks well, rather than

an overwhelming number of tasks only

adequately.

•

put o strategic planning until later

in the year. If you do, you might make

decisions that cannot be easily reversed.

•

skip the House/Senate orientations

and party organizational meetings.

They provide invaluable opportunities for

networking and learning the intricacies of

Capitol Hill.

CHAPTER

ONE

CHAPTER TWO

Selecting

Committee Assignments

This Chapter Includes...

✩ The importance of committee assignments to freshmen

✩ How the committee assignment process works

✩ How to choose and lobby for committee assignments

Perhaps the most important event for a freshman that occurs between the

election and the rst day of the new Congress is the allocation of committee