Legislative Council Sta

Nonpartisan Services for Colorado’s Legislature

Economic & Revenue Forecast

June 2024

June 2024 | Economic & Revenue Forecast

Contents

Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................................................ 3

General Fund Budget Overview ................................................................................................................................. 5

TABOR Outlook .............................................................................................................................................................. 21

General Fund Revenue ................................................................................................................................................ 27

Cash Fund Revenue ...................................................................................................................................................... 37

Economic Outlook ........................................................................................................................................................ 51

Colorado Economic Regions ..................................................................................................................................... 81

Appendix: Historical Data........................................................................................................................................ 119

Contributors

Greg Sobetski, Chief Economist

Marc Carey

Louis Pino

Elizabeth Ramey

David Hansen

Emily Dohrman

Amanda Liddle

Thomas Rosa

Debbie Grunlien

Special thanks to David Williams, Dan Phillips, Kent Parker, Suzanne Keim, Katie Kolupke,

Annabelle Tracy, Cathy Eslinger, Anna Gerstle, Bill Zepernick, Erin Reynolds, Matt Bishop, and

Kristine McLaughlin.

Legislative Council Staff • State Capitol Building • Denver, Colorado 80203

(303) 866-3521 • LCS.Economist@coleg.gov • http://leg.colorado.gov/EconomicForecasts

Legislative Council Staff is the nonpartisan service agency of the Colorado General Assembly.

June 2024 Executive Summary Page 3

Executive Summary

This report presents the budget outlook based on current law and the June 2024 forecast for General

Fund revenue, cash fund revenue, and the state TABOR outlook. It also includes summaries of

expectations for the U.S. and Colorado economies and discussion of the economic situation for nine

regions of the state.

General Fund Budget Outlook

The General Fund is expected to end FY 2023-24 with a 13.5 percent reserve,

$163.6 million below the statutory reserve requirement. General Fund revenue is

expected to fall by about $700 million, or 3.9 percent, mostly as a result of income

tax credits enacted during the 2024 session. Despite the decrease in revenue and an

8.5 percent increase in the Referendum C cap, collections are expected to exceed

the cap by $1.41 billion. Additionally, the state is obligated to refund $33.9 million

to correct prior underrefunds related to insurance premium tax revenue credited to

the Health Insurance Affordability Enterprise.

This forecast incorporates the 2024 Long Bill and other legislation affecting the

FY 2024-25 budget overview. The General Fund is expected to end FY 2024-25 with

a 14.5 percent reserve, $86.0 million below the statutory reserve requirement. This

amount may change based on ballot measures approved at the November 2024

election and legislation enacted during the 2025 legislative session. General Fund

revenue is expected to decrease by 1.7 percent and total $17.01 billion. After

adjusting for tax credits enacted during the 2024 legislative session, state revenue

subject to TABOR is expected to exceed the Referendum C cap by only about

$330 million. Given normal forecast error, it is possible that state revenue subject to

TABOR may fall below the Referendum C cap, which would cause the FY 2024-25

budget to be constrained by available revenues, rather than the TABOR limit.

General Fund revenue is expected to grow 8.0 percent and total $18.37 billion, with

state revenue subject to TABOR exceeding the Referendum C cap by $1.09 billion.

The General Fund is projected to have $1.26 billion, or 7.5 percent, more available

to spend or save than what is budgeted to be spent in FY 2024-25, after current law

transfers and the statutory reserve requirement. This amount does not incorporate

caseload growth, inflation, or other budgetary pressures, such as the expiration of

ARPA funds that were used to offset a portion of FY 2024-25 appropriations.

The General Fund Budget Overview section presents an alternative scenario that

projects additional FY 2025-26 budget obligations based on current law. Under this

scenario (“Scenario B”), the year-end General Fund reserve could fall short of the

reserve requirement by $575.7 million. Additional explanation can be found in the

discussion of budget Scenario B (see Table 2 on page 10).

Risks to the budget outlook. Risk to the budget outlook has increased relative to earlier forecasts,

as reduced revenue expectations raise the possibility that state revenue may fall short of the

Referendum C cap in FY 2024-25 and/or FY 2025-26, even without an economic recession. Other

usual risks likewise persist, including recession risk, volatile income tax revenue streams, and cash

fund revenue subject to TABOR that may trade off with available General Fund budget space.

FY 2023-24

FY 2024-25

FY 2025-26

Unbudgeted

June 2024 Executive Summary Page 4

TABOR refund requirement for exceeding Proposition FF Blue Book estimate. Income tax

revenue attributable to Proposition FF is now estimated to reach $127.1 million in FY 2024-25 on an

accrual basis, exceeding the estimate provided to voters in the 2022 Blue Book by $26.4 million. If

revenue does exceed the estimate, the state will be required to refund the excess unless voters

approve a ballot measure allowing the state to keep this amount.

Cash Fund Revenue

FY 2023-24 cash fund revenue subject to TABOR is projected to end the year at a level close to that

attained in FY 2022-23, with revenue increasing 0.5 percent to a total near $2.77 billion. Increases in

transportation-related revenue and other miscellaneous cash funds are expected to offset a

significant decrease in severance tax revenue and gaming tax revenue subject to TABOR. In FY

2024-25, cash fund revenue subject to TABOR is projected to increase 4.8 percent and total just over

$2.90 billion, driven by moderate increases in transportation-related revenue and severance tax

revenue. Finally, revenue for FY 2024-25 is expected to increase by 2.6 percent and total just below

$3.0 billion as growth in the largest revenue streams moderates.

Economic Outlook

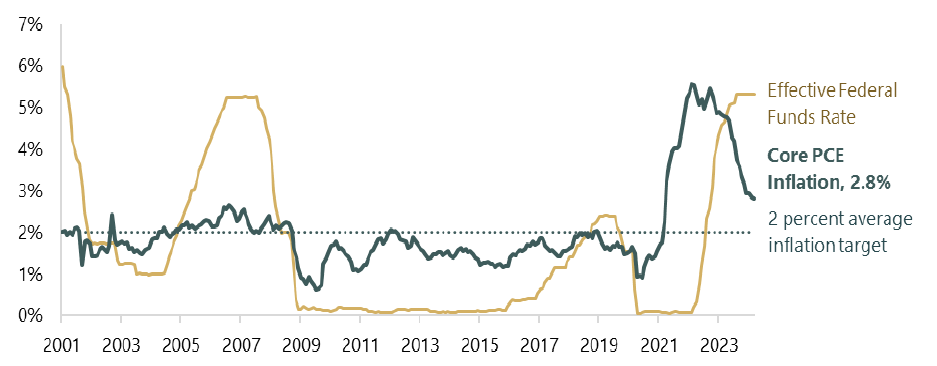

The U.S. economy continues to emerge from a tense period where runaway inflation resulted in

higher interest rates and borrowing costs, thereby slowing overall economic activity. Despite these

headwinds, the U.S and Colorado economies continued to expand through the first quarter of this

year. U.S. inflation remains high, and yet consumer activity has been resilient. Employers continue to

add jobs at a healthy rate. Households spending is buoying businesses even in the face of high

interest rates. Taken together, current indicators suggest that the U.S. economy is maintaining an

average or slightly below average pace of expansion, converging toward expectations for a

slowdown in growth.

This forecast expects continued moderate expansion in the U.S. and Colorado economies at a slightly

slower pace in 2024 than in 2023. Receding inflation and interest rate reductions, which are

anticipated to begin late this year, will boost growth, while deteriorating household balance sheets

will raise headwinds. Colorado’s economy is expected to modestly outperform the nation’s, with

comparable employment growth in 2024, higher income growth, and lower inflation.

Tables 19 and 20 on pages 79 and 80 present the economic forecasts for the U.S. and Colorado,

respectively. The tables in the Appendix, beginning on page 119, present historical data for the U.S.

and Colorado economies.

June 2024 General Fund Budget Overview Page 5

General Fund Budget Overview

This section presents the General Fund overview based on current law. The General Fund overview is

shown in Table 1. This section also presents the following:

a budget scenario for FY 2025-26 that incorporates General Fund obligations expected under

current law (Table 2);

a summary of changes in expectations relative to the March 2024 forecast (Table 3);

transfers to the State Education Fund (Figure 1);

transfers to transportation and capital construction funds (Table 4);

the disposition of fiscal policies dependent on revenue conditions, including calculations for an

affordable housing transfer required by statute to appear in this June forecast (Table 5);

General Fund rebates and expenditures (Table 6); and

cash fund transfers to and from the General Fund (Table 7).

Legislative Assumptions

This forecast is based on current law and incorporates all 2024 legislation that has become law or will

become law if a referendum petition is not filed. Notably, the forecast incorporates the FY 2024-25

Long Bill and associated budget package. The forecast does not account for provisions that would

only take effect if voters approve ballot measures at the November election.

Table 10 on page 28 summarizes legislation affecting the General Fund revenue forecast. Legislation

affecting TABOR accounting and TABOR refund mechanisms is discussed in the TABOR Outlook

section. Legislation affecting the cash fund revenue forecast is discussed in the Cash Fund Revenue

section.

The budget outlook below also includes notable adjustments for:

House Bill 24-1231, which reduced the statutory reserve requirement by $41.25 million for

FY 2023-24 and is expected to reduce the FY 2024-25 and FY 2025-26 reserve requirements by

the same amount;

House Bill 24-1390, which re-routes income tax revenue collected under Proposition FF to a

new Healthy School Meals for All Cash Fund, rather than the General Fund, beginning in

FY 2024-25; and

House Bills 24-1465 and 24-1466, which make budgetary adjustments concerning the

expenditures of federal American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) funds allocated to Colorado. Together,

they reduce FY 2023-24 and FY 2024-25 General Fund appropriations and make $1.395 billion in

transfers out of the General Fund in FY 2023-24. HB 24-1466 applies a $56.5 million increase to

the FY 2024-25 statutory reserve requirement calculation and contemplates an increase in the

reserve requirement for FY 2023-24; however, it is expected not to affect the FY 2023-24

requirement due to a technical issue with how the adjustment is written.

FY 2023-24

The General Fund is expected to end FY 2023-24 with a 13.5 percent reserve, $163.6 million below

the statutory reserve requirement, which is set at 15.0 percent of appropriations less $41.25 million

(Table 1, line 20). Expectations for the year-end excess reserve were revised down by $128.3 million

relative to the March forecast, mostly because increased General Fund obligations for transfers,

June 2024 General Fund Budget Overview Page 6

primarily under HB 24-1466, exceeded the amount saved by decreasing appropriations and reducing

the reserve requirement. General Fund revenue collections are expected to fall by 3.9 percent relative

to FY 2022-23, mostly as a result of income tax credits enacted during the 2024 legislative session.

State revenue subject to TABOR is still expected to exceed the Referendum C cap by $1.41 billion.

The General Fund obligation for TABOR refunds is estimated at $1.45 billion (Table 1, line 8) and

includes $33.9 million in under-refunds of prior obligations identified in the Single Statewide Audit

for FY 2022-23. The State Auditor found that $33.9 million in insurance premium tax revenue

credited to the Health Insurance Affordability Enterprise between FY 2020-21 and FY 2022-23 had

been accounted incorrectly as TABOR-exempt. This amount will be refunded with the state TABOR

refund obligation for FY 2023-24, and House Bill 24-1470 causes this revenue to be credited to the

General Fund, rather than the enterprise, beginning in FY 2023-24.

FY 2024-25

Incorporating appropriations adopted in the Long Bill and other 2024 legislation, new transfers to

and from the General Fund, as well as forecast expectations for revenue, preexisting transfers,

rebates and expenditures, and the TABOR refund obligation, the General Fund is expected to end

FY 2024-25 with a 14.5 percent reserve, $86.0 million below the statutory reserve requirement, which

is set at 15.0 percent of appropriations less $41.25 million (Table 1, line 20). This amount may change

due to normal revenue forecast revisions, ballot measures approved at the November 2024 election,

supplemental appropriations adopted during the 2025 legislative session, and other legislative

changes to appropriations and transfers.

General Fund revenue collections are expected to decrease by 1.7 percent, mostly due to expected

declines in corporate income tax revenue collections. Following the incorporation of tax credits

enacted during the 2024 legislative session in this revenue forecast, state revenue subject to TABOR

is expected to exceed the Referendum C cap by only about $330 million, much less than in recent

fiscal years. This means that it is possible, given normal forecast error, that state revenue subject to

TABOR will fall below the Referendum C cap in FY 2024-25, which would cause the FY 2024-25

budget to be constrained by available revenues, rather than the TABOR limit.

Refund obligation for exceeding Proposition FF Blue Book estimate. Under House Bill 24-1390,

revenue from the income tax addition in Proposition FF will be credited to a new Healthy School

Meals for All Cash Fund beginning in FY 2024-25. This forecast expects Proposition FF revenue to

total $127.1 million for FY 2023-24, exceeding the estimate of first full fiscal year revenue provided to

voters in the 2022 Blue Book by $26.4 million. If voters do not approve a ballot measure allowing this

revenue to be retained, the state will be required to refund this amount to taxpayers. This forecast

assumes that this refund would be administered differently than refund obligations when the state

exceeds the TABOR limit, and these amounts are not included in the refund mechanisms presented

in the TABOR Outlook section.

June 2024 General Fund Budget Overview Page 7

Table 1

General Fund Overview

Dollars in Millions

FY 2022-23

FY 2023-24

FY 2024-25

FY 2025-26

Funds Available

Actual

Estimate

Estimate

Estimate

1

Beginning Reserve

$3,203.2

$2,427.4

$1,867.9

$2,228.8

2

General Fund Revenue (Table 11)

$17,998.0

$17,299.8

$17,010.0

$18,372.9

3

Transfers from Other Funds (Table 7)

$53.5

$93.2

$177.5

$63.2

4

Total Funds Available

$21,254.8

$19,820.4

$19,055.4

$20,665.0

5

Percent Change

1.5%

-6.7%

-3.9%

8.4%

Expenditures

Actual

Budgeted

Budgeted

Estimate

6

General Fund Appropriations Subject to the Limit

1

$13,308.1

$13,818.6

$15,330.2

*

7

Appropriations from Healthy School Meals Account

1

$115.3

8

TABOR Refund Obligation Under Art. X, §20, (7)(d)

$3,678.3

$1,445.6

$328.1

$1,094.9

9

Rebates and Expenditures (Table 6)

$168.7

$231.4

$172.6

$180.2

10

Transfers to Other Funds (Table 7)

$1,005.7

$1,944.0

$478.0

$406.6

11

Transfers to the State Education Fund

2

$290.0

$0.0

$146.0

$0.0

12

Transfers to Transportation Funds (Table 4)

$88.0

$5.0

$117.5

$117.5

13

Transfers to Capital Construction Funds (Table 4)

$488.3

$392.6

$254.1

$20.0

14

Total Expenditures

$19,027.2

$17,952.4

$16,826.5

*

15

Percent Change

6.7%

-5.7%

-6.3%

*

16

Accounting Adjustments

3

$199.8

*

*

*

Reserve

Actual

Estimate

Estimate

Estimate

17

Year-End General Fund Reserve

$2,427.4

$1,867.9

$2,228.8

*

18

Year-End Reserve as a Percent of Appropriations

18.2%

13.5%

14.5%

*

19

Statutorily Required Reserve

4

$1,996.2

$2,031.5

2,314.8

*

20

Amount in Excess or (Deficit) of Statutory Reserve

$431.2

-$163.6

-$86.0

*

21

Excess Reserve as a Percent of Expenditures

2.3%

-0.9%

-0.5%

*

Perspectives on FY 2025-26 (Unbudgeted)

Estimate

Estimate

Estimate

Scenario A: Holds FY 2024-25 Appropriations Constant

5

22

Amount in Excess or (Deficit) of 15% Reserve Requirement

$1,257.4

23

As a Percent of Prior-Year Expenditures

7.5%

Scenario B: Projected Obligations Based on Current Law

6

24

Amount in Excess or (Deficit) of 15% Reserve Requirement

-$575.7

25

As a Percent of Prior-Year Expenditures

-3.4%

Addendum

Actual

Estimate

Estimate

Estimate

26

Percent Change in General Fund Appropriations

10.5%

3.8%

10.9%

*

27

5% of Colorado Personal Income Appropriations Limit

$18,757.9

$20,898.4

$22,110.7

$23,192.6

28

Transfers to State Education Fund per Amendment 23

$1,066.4

$1,209.0

$1,082.5

$1,185.0

Totals may not sum due to rounding. * Not estimated.

1

Line 6 shows appropriations subject to the statutory reserve requirement (line 19) and the appropriations limit (line 27). Line 7 shows

appropriations from the Healthy School Meals Program Exempt Account, which are not subject to the reserve requirement and

appropriations limit.

2

Includes transfers pursuant to HB 22-1390, net of amendments in SB 22-202, and SB 23B-001. Does not include transfers to the SEF

under Amendment 23, which are shown on line 28.

3

Reversions of appropriated amounts and other accounting adjustments to arrive at the year-end balance published in the Annual

Comprehensive Financial Report. FY 2022-23 includes $114.9 million underrefunded from the TABOR refund obligation, mostly due to

Proposition 121.

4

The required reserve is calculated as 15 percent of operating appropriations, minus $41.25 million (beginning in FY 2023-24), plus

$56.5 million (for FY 2024-25 only). Appropriations from the Healthy School Meals Account (line 7) are exempt from the reserve

requirement.

5

This scenario holds appropriations in FY 2025-26 equal to appropriations in FY 2024-25 (lines 6 and 7) to determine the total amount

of money available relative to FY 2024-25 expenditures, net of the obligations in lines 8 through 13.

6

This scenario includes expected cost pressures from the rolloff of ARPA contributions to the operating budget after FY 2024-25,

annualized costs for 2024 legislation, assumed increases for school finance, Medicaid, higher education, community provider rates, and

state employee salaries; capital construction and IT capital projects approved to date; and State Architect recommendations for

controlled maintenance. See Table 2.

June 2024 General Fund Budget Overview Page 8

FY 2025-26 (Unbudgeted)

General Fund revenue is expected to grow by 8.0 percent in FY 2025-26, above its historical trend

growth rate, though the revenue forecast is less accurate when looking further into the future.

Collections from individual and corporate income taxes are expected to rebound after a weak

FY 2024-25, primarily as a result of income tax policy changes enacted during the 2024 legislative

session becoming fully phased in. State revenue subject to TABOR is expected to exceed the

Referendum C cap by $1.09 billion. Because a budget has not yet been enacted for FY 2025-26, this

forecast presents two scenarios for the General Fund budget outlook.

Scenario A: Holds appropriations constant from FY 2024-25. Scenario A, shown on lines 22 and

23 of Table 1, shows the amount of revenue available to be spent or saved in FY 2025-26 if

FY 2025-26 appropriations were held constant from FY 2024-25 appropriations. This scenario does

not include annualizations of 2024 legislation. Based on this forecast, the General Fund will have

$1.26 billion, or 7.5 percent, more available to spend or save than in FY 2024-25. This amount

assumes current law obligations for FY 2025-26, including transfers, rebates, and expenditures

(Table 1, lines 9 through 13), as well as a reserve requirement equal to 15.0 percent of

appropriations, minus $41.25 million, and the projected TABOR refund obligation. The $1.26 billion

amount is a cumulative amount that reflects the FY 2024-25 enacted budget and projected year-end

balance. Any changes in revenue or adjustments made to the budget for FY 2024-25, including the

2025 supplemental budget package, will carry forward into FY 2025-26. This amount holds

FY 2024-25 appropriations constant and therefore does not reflect any caseload, inflationary, or

other budget pressures.

Scenario B: Projected Obligations Based on Current Law. Scenario B, shown on lines 24 and 25 of

Table 1, presents the amount of revenue in excess or deficit of the statutory reserve requirement for

FY 2025-26 based on a set of projected changes to appropriations and transfers to accommodate

current law budget pressures. The inclusion of Scenario B is illustrative and should not be considered

an endorsement of any of the listed actions by Legislative Council Staff. Under Scenario B, the

General Fund would end FY 2025-26 with an 11.3 percent reserve, $575.7 million below the statutory

reserve requirement.

Table 2 details the assumptions used to calculate Scenario B. Some additional explanation is

provided below.

Changes in General Fund appropriations. Scenario B incorporates adjustments to accommodate

the end of ARPA-related cost savings in the General Fund budget. House Bill 24-1466 transferred

General Fund revenue to ARPA recipient cash funds in FY 2023-24 and decreased General Fund

appropriations in FY 2023-24 and FY 2024-25; these adjustments are incorporated in the General

Fund overview for these years presented in Table 1, above. The bill reduced General Fund

appropriations for personal services by $587.2 million in FY 2024-25. In order to show an ongoing

personal services expense that incorporates both the amounts paid from the General Fund and

federal ARPA funds in FY 2024-25 that would be paid from the General Fund only in FY 2025-26,

Scenario B (Table 2, line 2) adjusts the Scenario A assumption to add back the $587.2 million

one-time cut when computing the FY 2025-26 budget.

Scenario B also includes out-year cost annualizations for 2024 legislation. Based on LCS final fiscal

notes, FY 2025-26 General Fund expenditures for 2024 legislation are expected to be $5.6 million

more than FY 2024-25 expenditures (Table 2, line 3).

June 2024 General Fund Budget Overview Page 9

Finally, Scenario B shows how appropriations for the largest areas of General Fund expenditure may

change in FY 2025-26. The growth rate assumptions provided below are based on JBC Staff analysis

of prior year budget actions, and may overstate or understate needed cost increases for FY 2025-26

specifically:

$127.2 million in increased General Fund appropriations for school finance, representing

3.0 percent year-on-year growth (Table 2, line 4);

$367.3 million in forecast-driven increases in General Fund appropriations for the Department of

Health Care Policy and Financing, mostly for medical services premiums (Table 2, line 5);

$82.7 million in increased General Fund appropriations for higher education institutions,

representing 5.3 percent year-on-year growth, the 20-year compound average annual growth

rate for this appropriation (Table 2, line 6);

$74.2 million in increased General Fund appropriations for community providers, representing

2.0 percent year-on-year growth with similar targeted rates to those for FY 2024-25 (Table 2,

line 7); and

$117.3 million in increased General Fund appropriations for state employee salaries, representing

similar increases to those for FY 2024-25 (Table 2, line 8).

In total, Scenario B shows the budget impact of $1,361.4 million in additional appropriations in

FY 2025-26 compared with the FY 2024-25 used for Scenario A (Table 2, line 9). With this increase,

the scenario also estimates a $204.2 million increase in the statutory reserve requirement (Table 2,

line 14). Scenario B does not incorporate the costs for any new state programs receiving General

Fund appropriations, which would further reduce the available amount.

Changes in General Fund transfers for capital projects. Scenario B shows a total of $267.5 million

in additional General Fund obligations for transfers to the Capital Construction Fund (Table 2,

line 13). The amount includes out-year costs for capital construction (line 10) and IT capital (line 11)

projects funded in FY 2024-25, alongside the State Architect’s recommended annual allocation for

controlled maintenance spending (line 12), equal to 1 percent of the current replacement value of

state buildings. The costs for new projects funded with General Fund transfers in FY 2025-26 would

add to the total amount.

June 2024 General Fund Budget Overview Page 10

Table 2

FY 2025-26 Budget Scenario B

Projected Obligations Based on Current Law

Dollars in Millions

FY 2025-26

1

Excess Reserve Under Scenario A

$1,257.4

Change in Appropriations Under Scenario B

2

Year-Over-Year Budget Impact of Rolloff of ARPA Funds

$587.2

3

2024 Legislation Out-Year Cost Annualizations

$5.6

4

School Finance (3% increase in General Fund appropriation)

$127.2

5

HCPF (all decision items, primarily Medical Services Premiums)

$367.3

6

Higher Ed. Institutions (5.3% GF increase based on 20-year CAAGR

1

)

$82.7

7

Community Providers (2% increase with FY 2024-25 targeted rates)

$74.2

8

Salary Survey (similar growth to FY 2024-25)

$117.3

9

Total Change in Appropriations

$1,361.4

Capital Construction Transfers Under Scenario B

10

Out-Year Cost of FY 2024-25 Funded Capital Const. Projects

$65.1

11

Out-Year Cost of FY 2024-25 IT Capital Projects

$26.8

12

State Architect Recommendation for Controlled Maintenance

$175.7

13

Total Change in Capital Transfers

$267.5

14

Change in Required Reserve (15% of Line 9)

$204.2

15

Total Change in General Fund Obligations

(Line 9 plus Line 13 plus Line 14)

$1,833.1

16

Excess Reserve Under Scenario B

(Line 1 minus Line 15)

($575.7)

Source: June 2024 LCS Forecast and Joint Budget Committee Staff.

1

CAAGR = compound average annual growth rate.

Risks to the General Fund Budget Outlook

Recession risk is budget risk. This forecast projects that the economy will realize a soft landing,

with no recession in 2024. However, the economy is still susceptible to a downturn if confronted with

major shocks. A recession would likely reduce revenue below the Referendum C cap, thereby

reducing the amount available for the General Fund budget beginning in the year when the

recession occurs.

Revenue may fall below the Referendum C cap even without a recession. FY 2024-25 revenue is

expected to exceed the Referendum C cap by $328.1 million, or 1.7 percent. Even without a

recession, it is well within the range of normal forecast error for revenue to fall below the

Referendum C cap, in which case revenue, and not the cap, would limit the amount available for the

General Fund budget.

The corporate income tax outlook is especially uncertain. Corporate income tax collections

increased 50.9 percent in FY 2022-23, an unprecedented rise that followed another mammoth

increase in FY 2021-22. Corporate collections are expected to rise 16.5 percent further in FY 2023-24,

June 2024 General Fund Budget Overview Page 11

then fall by 19.3 percent in FY 2024-25. Given recent volatility, there is significant bidirectional risk to

the forecast. In the near term, forecast error would result in a higher or lower TABOR refund

obligation with no downstream impact on the state budget. However, especially volatile corporate

collections could exacerbate the budget consequences if revenue falls below the Referendum C cap.

Higher-than-expected cash fund revenue would increase General Fund budget pressures. Most

sources of cash fund revenue—including severance tax revenue, which is the state’s most volatile

revenue stream—are subject to the TABOR limit. Because TABOR surpluses are refunded using

General Fund money, higher-than-expected cash fund revenue would create additional budgetary

pressures for the General Fund.

Changes Between the March and June Forecasts

Table 3 presents revisions to the General Fund budget outlook relative to the March forecast. These

changes are explained below.

FY 2023-24. The March forecast anticipated that the General Fund would end FY 2023-24 with a

reserve $35.3 million below the statutory requirement. This June forecast downgrades that

expectation by $128.3 million, and anticipates a reserve $163.6 million below the statutory

requirement (Table 1, line 20). The lower expectation is a result of the transfers to ARPA recipient

funds in HB 24-1466, which more than offset decreased appropriations and the decreased statutory

reserve requirement. This was an intentional consequence of the legislation, which frontloaded the

transfers to FY 2023-24 while accomplishing a reduction in General Fund appropriations for both

FY 2023-24 and FY 2024-25, decreasing General Fund obligations on net over the two-year period.

Expected General Fund revenue and the expected TABOR refund obligation were both reduced.

Downgrades in the forecast of cash fund revenue subject to TABOR more than offset the refund

requirement attributable to the State Auditor’s finding regarding insurance premium taxes paid to

the Health Insurance Affordability Enterprise, which was discussed in the March forecast but not

included in the baseline expectation. On net, the TABOR limit is expected to apply $63.0 million less

in budget pressure than was forecast in March

FY 2024-25. The March forecast was prepared before the General Assembly had enacted a budget

for FY 2024-25. Table 3 compares the June 2024 forecast for FY 2024-25, which includes the Long Bill

and all other 2024 legislation, to the March forecast’s Scenario A in order to show how available

funds were spent.

June 2024 General Fund Budget Overview Page 12

Table 3

Changes in the General Fund Budget Relative to the March 2024 Forecast (Scenario A)

Dollars in Millions, Positive Amounts Reflect an Increase Relative to March

Components of Change

FY 2023-24

FY 2024-25

Description of Changes

Funds Available

-$293.5

-$1,870.5

Beginning Balance

$0.0

-$323.0

Carries forward anticipated FY 2023-24 year-end balance to FY 2024-25.

General Fund Revenue

-$315.8

-$1,643.1

Reflects forecast changes, largely due to new income tax credits; see

Table 10 (legislative impacts) and Table 11 (General Fund revenue). For

FY 2024-25, also reflects the movement of Proposition FF revenue out of

the General Fund under HB 24-1390.

Transfers from Other Funds

$22.3

$95.6

Mostly legislative changes, including HB 24-1415 for FY 2023-24, and

HB 24-1413 and HB 24-1426 for FY 2024-25. See Table 7.

Expenditures

$29.5

-$935.0

Operating Appropriations

-$1,023.4

$372.9

Reflects the FY 2024-25 Long Bill, HB 24-1466, and other legislation.

TABOR Refund Obligation

-$378.9

-$1,581.6

Changes to General Fund and cash fund revenue forecasts, as well as

HB 24-1469. See Table 9.

Rebates and Expenditures

-$5.8

-$14.1

Primarily reduced expected Old Age Pension payments. See Table 6.

SEF Transfers

$0.0

$0.0

Transportation Transfers

$0.0

$0.0

Capital Const. Transfers

$41.3

$234.1

HB 24-1231, HB 24-1425, and SB 24-222. See Table 4.

Other Cash Fund Transfers

$1,396.4

$53.8

Reflects 2024 legislation, most notably HB 24-1466 for FY 2023-24, and

HB 24-1313 for FY 2024-25. See Table 7.

Required Reserve

-$194.8

$88.5

15 percent of change to operating appropriations shown above, alongside

reduced requirement for both years (HB 24-1231) and increase for

FY 2024-25 only (HB 24-1466).

Surplus Relative to

Required Reserve

-$128.3

-$1,024.0

Nets the above changes.

June 2024 General Fund Budget Overview Page 13

State Education Fund Transfers

The Colorado Constitution (Amendment 23) requires the State Education Fund (SEF) to receive one-

third of 1 percent of taxable income. In FY 2023-24, the SEF will receive a total of $1.21 billion as a

result of this requirement, equal to $1.07 billion in estimated transfers required for the current year,

plus $135.1 million in corrections for prior year under-transfers, discussed below. The SEF transfer is

estimated at $1.23 billion in FY 2024-25, including a transfer scheduled under Senate Bill 23B-001,

and $1.18 billion in FY 2025-26, with increases attributable to growth in taxable income among

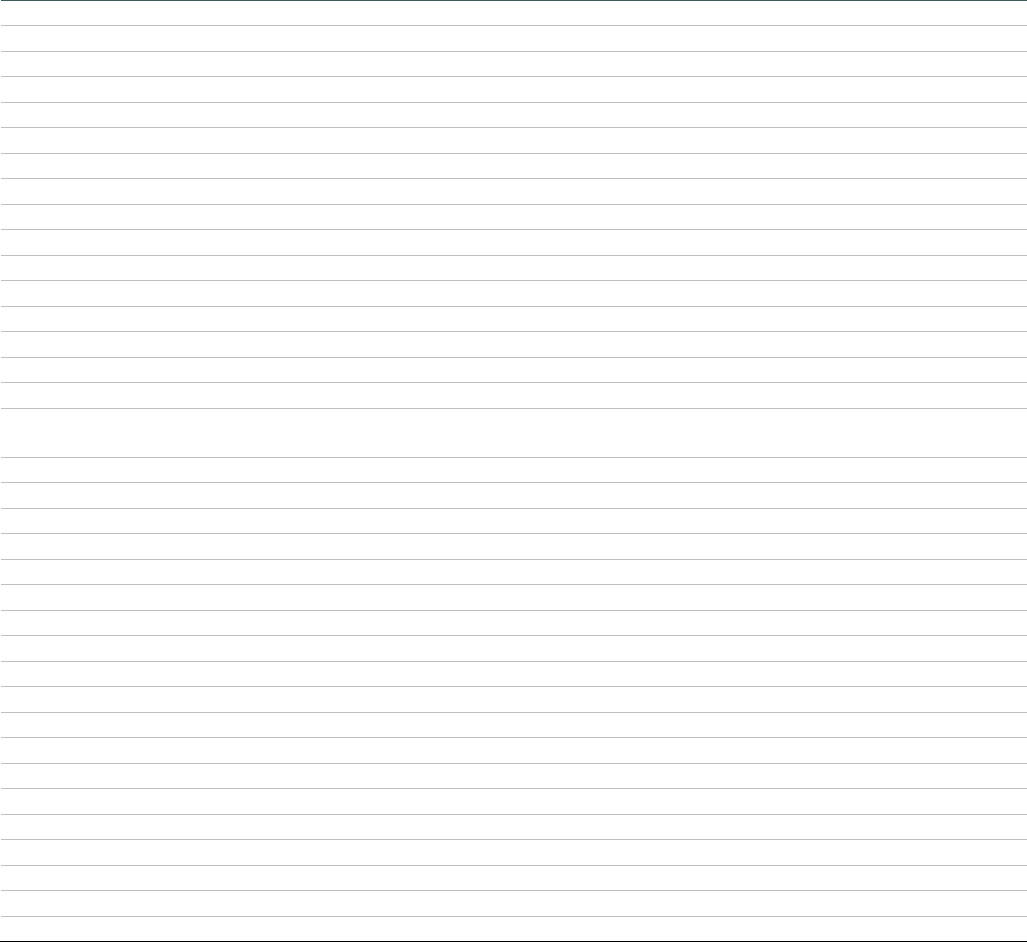

Colorado taxpayers. Figure 1 shows revenue to the State Education Fund, which is required to be

used to fund kindergarten through twelfth grade public education.

Figure 1

Revenue to the State Education Fund

Dollars in Millions

Source: Colorado State Controller’s Office and Legislative Council Staff forecast. f = Forecast.

*Includes transfers under SB 19-246 for FY 2019-20, HB 20-1420 for FY 2020-21 and FY 2021-22, HB 20-1427 for

FY 2020-21 through FY 2022-23, SB 21-208 for FY 2021-22, HB 22-1390 for FY 2022-23, and SB 23B-001 for

FY 2024-25.

**One-third of 1 percent of federal taxable income is required to be dedicated to the State Education Fund under

Article IX, Section 17 of the Colorado Constitution (Amendment 23).

Correction of prior year under-transfers to the State Education Fund. LCS is required to calculate

SEF transfer amounts with each quarterly forecast and notify the Department of Revenue of quarterly

transfer requirements. State law requires LCS to correct for prior year errors in transfer amounts

when these are identified. Every annual transfer contains error because data on taxable income

amounts are unavailable at the time that transfers are performed. Since the September 2020 forecast,

LCS has kept a rolling accounting of all prior year errors, dating back to FY 2019-20, and

incorporated corrections for these errors in each quarterly forecast’s SEF transfer amount.

The June 2024 forecast corrects a relatively minor methodological error related to adjustments for

the impact of refundable income tax credits on estimates of the transfer amount. This

methodological improvement brought to light $19.0 million in cumulative under-transfers between

FY 2019-20 and FY 2022-23. More importantly, the new methodology allows for a complete review of

all SEF transfer amounts dating back to the first SEF transfer in FY 2000-01. This review found that

$540

$617

$693

$647

$875

$994

$1,066

$1,082

$40

$118

$274

$429

$146

$565

$642

$718

$687

$992

$1,268

$1,496

$1,209

$1,228

$1,185

$0

$200

$400

$600

$800

$1,000

$1,200

$1,400

$1,600

Other Transfers*

Senate Bill 13-234

Constitutionally Required**

Transfer totals in bold

June 2024 General Fund Budget Overview Page 14

LCS had corrected transfer errors between FY 2000-01 and FY 2003-04, but had usually

under-transferred revenue, without correction, by amounts between $5 million and $15 million per

year between FY 2004-05 and FY 2018-19. The cumulative under-transfer over the 19-year period

between FY 2004-05 and FY 2022-23 totals $135.1 million, equal to about 1.3 percent of the

calculated transfer requirement over that period.

This forecast corrects the entire $135.1 million under-transfer by making a positive adjustment to the

FY 2023-24 transfer, and anticipates that no later corrections will be required for FY 2022-23 or any

prior year. For a complete discussion of the corrections, see the June 20, 2024, LCS memorandum

titled “Corrections of Prior-Year Transfers to the State Education Fund,” available here.

Revenue transferred to the SEF under Amendment 23 is exempt from TABOR. Transfer amounts

reduce both General Fund revenue and the state TABOR refund obligation, with no net impact on the

amount available for the General Fund budget.

General Fund Transfers for Transportation and Capital Construction

Statutory transfers from the General Fund to transportation and capital construction funds are shown

in Table 4. In the General Fund overview shown in Table 1, these transfers are included on lines 12

and 13. Other non-infrastructure-related transfers to and from the General Fund are summarized in

Table 6, and shown on lines 3 and 10 of Table 1.

Table 4

Infrastructure Transfers from the General Fund

Dollars in Millions

Transportation Funds

2022-23

2023-24

2024-25

2025-26

SB 21-260

$2.5

$117.5

$117.5

HB 22-1351

$78.5

SB 22-176

$7.0

SB 23-283

$5.0

Total

$88.0

$5.0

$117.5

$117.5

Capital Construction Funds

2022-23

2023-24

2024-25

2025-26

HB 15-1344*

$20.0

$20.0

$20.0

$20.0

HB 22-1340

$462.2

SB 23-141

$6.1

SB 23-243

$294.2

SB 23-294

$18.2

HB 24-1215

$19.0

HB 24-1231

$41.3

HB 24-1425

$232.2

SB 24-222

$1.9

Total

$488.3

$392.6

$254.1

$20.0

*Transfers are contingent upon requests made by the Capital Development Committee.

June 2024 General Fund Budget Overview Page 15

General Fund contributions to transportation. Senate Bill 23-283 directs $5.0 million to the State

Highway Fund in FY 2023-24 only. Senate Bill 21-260 will direct annual transfers from the General

Fund to the State Highway Fund ($107.0 million) and the Multimodal Transportation and Mitigation

Options Fund ($10.5 million) beginning in FY 2024-25. These transfers continue annually at the same

amounts through FY 2028-29 and are then reduced to smaller amounts beginning in FY 2029-30.

General Fund transfers for capital projects. Legislation enacted in 2023 directed transfers of

$312.4 million in FY 2023-24 for capital construction and IT projects. In 2024, the General Assembly

enacted four bills making transfers for capital construction and IT projects. House Bills 24-1215

and 24-1231 together transfer $60.2 million in FY 2023-24, while House Bill 24-1425 and

Senate Bill 24-222 together transfer $234.1 million in FY 2024-25.

Fiscal Policies Dependent on Revenue Conditions

Certain fiscal policies are dependent upon forecast revenue conditions. These policies are

summarized below.

Tax credit availability and amounts. In 2023 and 2024, the General Assembly adopted four bills

that create income tax credits for which availability and amounts depend on revenue forecasts.

Forecast assumptions for each credit are described below.

Tax credits related to decarbonization in HB 23-1272. The bill extends pre-existing income

tax credits for electric and plug-in hybrid electric passenger vehicles (through 2028) and trucks

(through 2032). It also creates new income tax credits for installation of heat pumps or sales of

electric bicycles, both through 2032. Beginning in tax year 2026, credit amounts are reduced by

half in tax years where the preceding June forecast from either Legislative Council Staff (LCS) or

the Office of State Planning and Budgeting (OSPB) anticipates that state revenue subject to

TABOR will grow by less than 4 percent. The trigger will first apply based on the June 2025

forecasts of revenue for FY 2025-26. Under this forecast, revenue subject to TABOR is expected

to increase by 7.4 percent in FY 2025-26, and the full credit amounts are expected to be available

for tax year 2026.

Workforce shortage tax credit in HB 24-1365. The bill creates a tax credit for tax years 2026

through 2032 for facility improvement and equipment acquisition costs associated with training

programs to alleviate worker shortages. Total credit certificates issued for each tax year may not

exceed $15 million. This amount is reduced to $7.5 million in tax years where the preceding

September forecast from either LCS or OSPB anticipates that state revenue subject to TABOR will

grow by less than 4 percent. The trigger will first apply based on the September 2025 forecasts of

revenue for FY 2025-26. Under this forecast, revenue subject to TABOR is expected to increase by

7.4 percent in FY 2025-26, and $15 million credit cap is expected to be apply for tax year 2026.

Earned income tax credit in HB 24-1134 and family affordability tax credit in HB 24-1311.

These bills expand the state earned income tax credit (HB 24-1134) and create a family

affordability income tax credit (HB 24-1311). Both credits apply unconditionally in tax year 2024.

For tax year 2025 and later tax years, the credits in the bills may be reduced based on revenue

projections for the fiscal year that begins during the tax year, as projected in the December

forecast that is prepared by the agency whose forecast was selected by the Joint Budget

Committee (JBC) to balance that fiscal year’s budget. For example, because the JBC selected the

March 2024 OSPB forecast to balance the FY 2024-25 budget, the amounts of the credits for tax

year 2025 will depend on the December 2024 OSPB forecast for revenue subject to TABOR for FY

2025-26.

June 2024 General Fund Budget Overview Page 16

Under this forecast, FY 2025-26 revenue growth is expected to be sufficient to allow both credits

in full for tax year 2025. A forecast of revenue growth for FY 2026-27 is not yet available, and the

forecast assumes that both credits will be available in full for tax year 2026. Actual credit

availability and amounts will depend on the December 2024 OSPB forecast, and a

December 2025 forecast from either LCS or OSPB.

Partial refundability of the conservation easement tax credit. The conservation easement income

tax credit is available as a nonrefundable credit in most years. In tax years when the state refunds a

TABOR surplus, taxpayers may claim an amount up to $50,000, less their income tax liability, as a

refundable credit. The state collected a TABOR surplus in FY 2022-23, and this forecast expects a

TABOR surplus in each of FY 2023-24, FY 2024-25, and FY 2025-26. Therefore, partial refundability of

the credit is expected to be available for tax years 2023 through 2026. Under Senate Bill 24-126, the

refundable amount will increase to $200,000 per taxpayer per year beginning in tax year 2027.

Contingent transfers for affordable housing. House Bill 19-1322 created conditional transfers

from the Unclaimed Property Trust Fund (UPTF) to the Housing Development Grant Fund for

affordable housing projects for three fiscal years. House Bill 20-1370 delayed the start of these

contingent transfers until FY 2022-23. The transfers are contingent based on the balance in the UPTF

as of June 1 and the Legislative Council Staff June 2023 forecast and subsequent June forecasts. For

the fiscal year in which the June forecast is published, if revenue subject to TABOR is projected to fall

below a “cutoff” amount, equal to the projected Referendum C cap minus $30 million dollars, a

transfer will be made. The transfer is equal to the lesser of $30 million or the UPTF fund balance.

Based on the June 2023 LCS forecast, no transfer was made for FY 2022-23.

Statute requires that each June forecast report estimates of state revenue subject to TABOR and the

cutoff amount, and the calculated transfer amount based on these estimates for the current fiscal

year. Table 5 presents these amounts for FY 2023-24.

Table 5

FY 2023-24 Transfer from the Unclaimed Property Trust Fund

to the Housing Development Grant Fund

Dollars in Millions

FY 2023-24

Revenue Subject to TABOR

$19,484.9

TABOR Limit (Referendum C Cap)

$18,073.2

Transfer Cutoff Amount

$18,043.2

Excess/(Deficit) of Cutoff Amount*

$1,441.7

FY 2023-24 Transfer Amount

$0.0

*This amount must be $0 or less for a transfer to be made.

Because this forecast projects that revenue subject to TABOR will exceed the cutoff amount, no

transfer will be made for FY 2023-24. Based on this forecast, no transfer is expected for

FY 2024-25 or FY 2025-26, as revenue subject to TABOR is expected to come in above the cutoff

amount in both years.

June 2024 General Fund Budget Overview Page 17

Table 6

General Fund Rebates and Expenditures

Dollars in Millions

Category

Actual

FY 2022-23

Percent

Change

Estimate

FY 2023-24

Percent

Change

Estimate

FY 2024-25

Percent

Change

Estimate

FY 2025-26

Percent

Change

Senior and Veterans Property Tax Exemptions

$163.7

1.0%

$161.2

-1.5%

$166.2

3.1%

$174.0

4.7%

TABOR Refund Mechanism

1

-$163.6

-$161.2

-$166.2

-$174.0

Property Tax Assessed Value Reductions

$291.9

$0.0

$50.0

TABOR Refund Mechanism

2

-$238.6

NA

-$50.0

Cigarette Rebate

$7.7

-7.0%

$6.4

-16.7%

$5.4

-15.2%

$5.4

-0.6%

Old Age Pension Fund

$84.9

10.4%

$84.3

-0.7%

$84.2

-0.1%

$94.1

11.8%

Aged Property Tax and Heating Credit

$12.0

105.2%

$10.3

-14.6%

$11.4

11.0%

$8.5

-25.3%

Older Coloradans Fund

$10.0

0.0%

$10.0

0.0%

$10.0

0.0%

$10.0

0.0%

Interest Payments for School Loans

$10.5

952.4%

$26.2

149.0%

$19.9

-24.1%

$19.0

-4.8%

Firefighter Pensions

$4.3

-5.0%

$4.0

-5.5%

$4.1

1.2%

$4.5

9.8%

Amendment 35 Distributions

$0.7

-6.9%

$0.7

-3.9%

$0.6

-8.5%

$0.6

0.5%

Marijuana Sales Tax Transfer to Local Governments

$21.9

-14.5%

$19.7

-9.9%

$18.7

-5.1%

$19.5

3.9%

Business Personal Property Exemptions

3

$16.6

-0.5%

$16.4

-1.2%

$18.3

11.0%

$18.7

2.2%

Total Rebates and Expenditures

$168.7

12.8%

$231.4

37.1%

$172.6

-25.4%

$180.2

4.4%

Totals may not sum due to rounding. NA = Not applicable.

1

Pursuant to SB 17-267, local government reimbursements for these property tax exemptions are the first TABOR refund mechanism used to meet the prior year's

refund obligation.

2

Includes reimbursements to local governments under to SB 22-238, SB 23B-001, and SB 24-111. Reimbursements under SB 22-238 and SB 24-111 are the second

TABOR refund mechanism used to meet the refund obligations incurred in FY 2022-23, FY 2025-26, and FY 2026-27.

3

Pursuant to HB 21-1312, local governments are reimbursed for expanded business personal property tax exemptions.

June 2024 General Fund Budget Overview Page 18

Table 7

Cash Fund Transfers

Dollars in Millions

Transfers to the General Fund

2022-23

2023-24

2024-25

2025-26

HB 92-1126

Land and Water Management Fund

$0.1

$0.0

$0.0

$0.0

HB 05-1262

Amendment 35 Tobacco Tax

$0.7

$0.7

$0.6

$0.6

SB 13-133 &

HB 20-1400

Limited Gaming Fund

$21.6

$22.2

$21.9

$22.4

HB 17-1343

Repeal of Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities

Services Cash Fund

$16.9

HB 20-1427

2020 Tax Holding Fund

$4.1

$4.1

$4.1

$4.1

SB 20B-002

Repeal of Emergency Direct Assistance Grant Fund

$0.02

SB 21-209

Repealed Cash Funds

$0.1

SB 21-213

Use of Increased Medicaid Match

$10.0

$9.2

$7.4

$1.1

SB 21-222

Repeal of Recovery Audit Cash Fund

$0.03

SB 21-251

Loan Family Medical Leave Program

$1.5

SB 21-260

Community Access Enterprise

$0.1

HB 23-1272

Decarbonization Tax Credits Administration

$12.4

$37.6

$35.0

HB 23-1290

1

Proposition EE Revenue Retention

$5.6

SB 23-215

State Employee Reserve Fund

$4.9

HB 24-1413

Severance Tax Cash Funds

$69.3

HB 24-1414

COVID Heroes Collaboration Fund

$3.4

HB 24-1415

State Employee Reserve Fund

$31.2

HB 24-1424

College Opportunity Fund

$1.5

HB 24-1426

Controlled Maintenance Trust Fund

$33.2

Total Transfers to the General Fund

$53.5

$93.2

$177.5

$63.2

Transfers from the General Fund

2022-23

2023-24

2024-25

2025-26

SB 11-047 &

HB 13-1001 &

SB 23-066 &

HB 24-1396

Bioscience Income Tax Transfer to OEDIT

$17.6

$14.4

$15.2

$16.0

SB 14-215

Marijuana Tax Cash Fund

$142.2

$127.7

$121.2

$126.0

SB 15-244 &

SB 17-267

State Public School Fund

$24.9

$22.4

$21.2

$22.1

HB 20-1116 &

HB 24-1398

Procurement Technical Assistance Program

$0.2

$0.2

$0.2

$0.2

HB 20-1427

2020 Tax Holding Fund

$235.0

$215.5

$237.3

$238.2

HB 20-1427

2

Preschool Programs Cash Fund

$0.0

SB 21-281

Severance Tax Trust Fund Allocation

$9.5

HB 22-1001

Reduce Fees For Business Filings

$8.4

HB 22-1004

Driver License Fee Reduction

$3.9

HB 22-1011

Wildfire Mitigation Incentives for Local Governments

$10.0

HB 22-1012

Wildfire Mitigation and Recovery

$7.2

HB 22-1115

Prescription Drug Monitoring Program

$2.0

HB 22-1132

Regulation and Services for Wildfire Mitigation

$0.1

HB 22-1151

Turf Replacement Program

$2.0

1

Because Proposition II was approved by voters, the $5.6 million set aside from the General Fund to pay refunds if Proposition II

had failed is returned to the General Fund under HB 23-1290.

2

HB 20-1427 requires the transfer of 73% of additional sales tax revenue due to the imposition of the minimum cigarette price to

the Preschool Programs Cash Fund on June 30th in 2021, 2022, and 2023.

June 2024 General Fund Budget Overview Page 19

Table 7 (Cont.)

Cash Fund Transfers

Dollars in Millions

Transfers from the General Fund (Continued)

2022-23

2023-24

2024-25

2025-26

HB 22-1298

Fee Relief for Nurses, Nurse Aides, and Technicians

$11.7

HB 22-1299

Fee Relief for Mental Health Professionals

$3.7

HB 22-1381

CO Energy Office Geothermal Grant Program

$12.0

HB 22-1382

Support Dark Sky Designation and Promotion

$0.04

HB 22-1394

Fund Just Transition Community & Worker Supports

$15.0

HB 22-1408

Modify Incentives for Film Production

$2.0

SB 22-036

State Payment Old Hire Death and Disability Benefits

$6.7

SB 22-130

Authority For Public-Private Partnerships

$15.0

SB 22-151

Safe Crossings for Colorado Wildlife and Motorists

$5.0

SB 22-163

Establish State Procurement Equity Program

$2.0

SB 22-183

Crime Victims Services

$1.0

SB 22-191

1

Procurement of Information Technology Resources

SB 22-193

Air Quality Improvement Investments

$1.5

SB 22-195

Conservation District Grant Fund

$0.1

$0.1

$0.1

$0.1

SB 22-202

State Match for Mill Levy Override Revenue

$10.0

SB 22-214

General Fund Transfer to PERA Payment Cash Fund

$198.5

SB 22-215 & SB

23-283

Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act Cash Fund

$84.0

SB 22-238

State Public School Fund

$200.0

HB 23-1041

Prohibit Greyhound Wagering

$0.03

$0.05

HB 23-1107

Crime Victim Services

$3.0

HB 23-1269

2

Extended Stay & Boarding Permits

HB 23-1273

Wildfire Resilient Homes Grant Program

$0.1

HB 23-1290

3

Proposition EE Revenue Retention

$5.6

HB 23-1305

Continue Health Benefits in Work-Related Death

$0.2

$0.2

$0.2

SB 23-001

Public-Private Collaborations for Housing

$5.0

SB 23-005

Forestry and Wildfire Mitigation Workforce

$1.0

$1.0

$1.0

$1.0

SB 23-044

Veterinary Education Loan Repayment Program

$0.5

SB 23-056

4

Compensatory Direct Distribution to PERA

$10.0

SB 23-137

Colorado Economic Development Fund

$5.0

SB 23-141

DMVA Real Estate Proceeds Cash Fund

$4.9

SB 23-161

Firefighting Aircraft

$26.0

SB 23-166

Wildfire Resiliency Code Board

$0.3

SB 23-199

5

Marijuana Cash Fund

SB 23-205

Universal High School Scholarship Program

$25.0

SB 23-246

State Emergency Reserve

$20.0

SB 23-255

Wolf Depredation Compensation Fund

$0.2

$0.4

$0.4

1

Beginning in FY 2023-24, SB 22-191 directs transfers of unspent prior year General Fund appropriations for IT procurement.

Any transfer amount for FY 2023-24 is included in the FY 2022-23 General Fund appropriation amount and not included here.

2

For FY 2022-23 and FY 2023-24, HB 23-1269 requires transfers from unexpended funds appropriated for county child welfare

programs. Any transfer amount is already included in General Fund appropriations amounts and not counted again here.

3

HB 23-1290 required that $23.65 million be transferred to the Proposition EE Refund Cash Fund on September 1, 2023. Of this

amount, $18.03 million was transferred from the Preschool Programs Cash Fund, and the remaining $5.62 million was

transferred from the General Fund.

4

SB 23-056 requires that a $10.0 million warrant be paid from the General Fund to PERA. This amount is shown in this table as

a General Fund obligation that is not included in the appropriations amount in Table 1, line 6.

5

For FY 2022-23 only, SB 23-199 requires transfers from unexpended funds appropriated to the Department of Revenue. Any

transfer amount is already included in the General Fund appropriations amount and not counted again here.

June 2024 General Fund Budget Overview Page 20

Table 7 (Cont.)

Cash Fund Transfers

Dollars in Millions

Transfers from the General Fund (Continued)

2022-23

2023-24

2024-25

2025-26

SB 23-257

Auto Theft Prevention Cash Fund

$5.0

SB 23-275

Wild Horse Management Project

$1.5

HB 23B-1001

Housing Development Grant Fund

$15.1

HB 24-1043

Death and Disability Payment Cash Fund

$2.1

HB 24-1152

ADU Fee Reduction and Encouragement Program

$5.0

$8.0

HB 24-1176

Behavioral and Mental Health Cash Fund

$4.0

HB 24-1211

Senior Services Contingency Reserve Fund

$2.0

HB 24-1213

Judicial Collection Enhancement Fund

$2.5

HB 24-1214

Community Crime Victims Cash Fund

$4.0

HB 24-1237

Child Care Facility Development Cash Fund

$0.3

HB 24-1280

Welcome, Reception, and Integration Cash Fund

$2.5

HB 24-1313

Transit-Oriented Communities Infrastructure Fund

$35.0

HB 24-1364

Longitudinal Data System Cash Fund

$5.0

HB 24-1365

Opportunity Now Grants

$4.0

HB 24-1386

Broadband Infrastructure Cash Fund

$4.6

HB 24-1390

1

Healthy School Meals for All Program Cash Fund

$3.2

HB 24-1397

Creative Industries Cash Fund

$0.5

HB 24-1420

Crime Victim Services Fund

$4.0

HB 24-1421

Multidisciplinary Crime Prevention Crisis Intervention

$3.0

HB 24-1439

Apprenticeship Programs

$4.0

HB 24-1465

Family and Medical Leave Insurance Fund

$0.4

HB 24-1466

ARPA Recipient Cash Funds

$1,394.6

SB 24-170

America 250 - Colorado 150 Cash Fund

$0.3

SB 24-214

2

State Agency Sustainability Revolving Fund

$0.1

$0.4

$0.4

SB 24-218

Lineworker Apprenticeship Grant Program Cash Fund

$0.8

SB 24-221

Rural Hospital Cash Fund

$1.7

Total Transfers from the General Fund

$1,005.7

$1,944.0

$478.0

$406.6

Net General Fund Impact

-$952.2

-$1,850.8

-$300.6

-$343.4

1

The balance of the Healthy School Meals for All General Fund Exempt Account is transferred to a new cash fund on July 1,

2024.

2

This bill increased the amount of a transfer to the Energy Fund that occurred in June 2022. The additional amount, $125,000,

was deposited in the Energy Fund in FY 2023-24.

June 2024 TABOR Outlook Page 21

TABOR Outlook

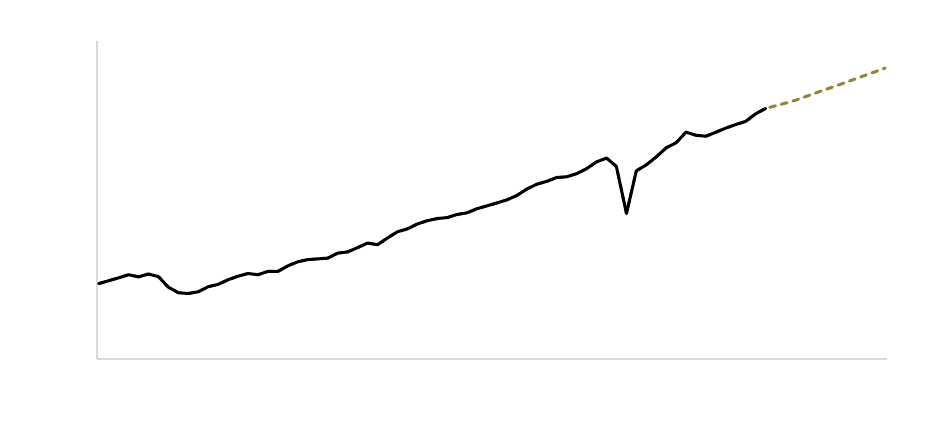

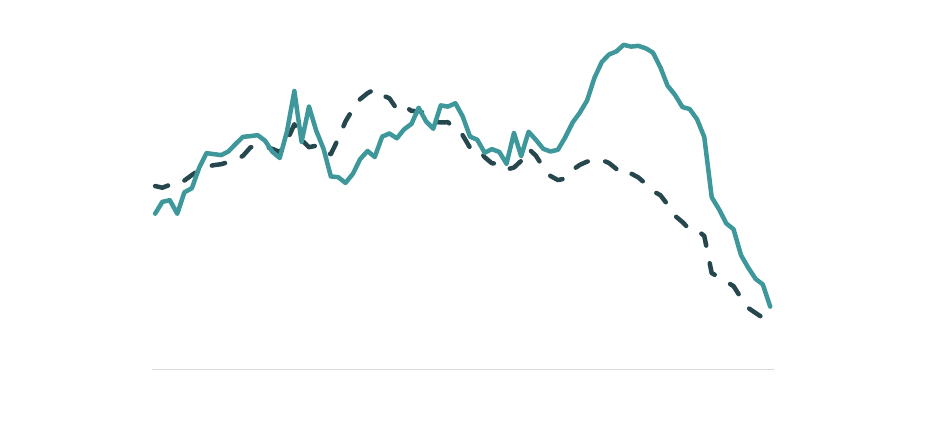

The state TABOR outlook is presented in Table 9 and illustrated in Figure 2, which also provides a

history of the TABOR limit base and the Referendum C cap. In FY 2022-23, state revenue subject to

TABOR exceeded the Referendum C cap, creating a state obligation for TABOR refunds to taxpayers

in FY 2023-24. State revenue subject to TABOR is projected to exceed the Referendum C cap in each

of FY 2023-24, FY 2024-25, and FY 2025-26, creating a state obligation for TABOR refunds to be paid

to taxpayers in each of FY 2024-25, FY 2025-26, and FY 2026-27.

Figure 2

TABOR Revenue, TABOR Limit Base, and the Referendum C Cap

Dollars in Billions

Source: Office of the State Controller and Legislative Council Staff. f = Forecast.

*The refund amount for FY 2023-24 differs from the surplus amounts because it includes $33.9 million

in under-refunds from prior TABOR surpluses.

Forecasts for FY 2023-24 through FY 2025-26. State revenue subject to TABOR is projected to

exceed the Referendum C cap throughout the forecast period. Even with high 2022 inflation resulting

in a doubling of the growth rate used to calculate the FY 2023-24 Referendum C cap, revenue in the

current FY 2023-24 is expected to exceed the Referendum C cap by $1.41 billion. Revenue is

projected to exceed the cap by $328 million in FY 2024-25 and by $1.09 billion in FY 2025-26.

Refunds of those amounts are expected to be returned to taxpayers in the fiscal year following each

surplus. The actual refund obligation in any given year will incorporate any over- or under-refund of

prior year surpluses.

Relative to the March forecast, expectations for revenue subject to TABOR were decreased by about

$413 million in FY 2023-24, by $1.6 billion in FY 2024-25, and by $1.2 billion in FY 2025- 26, reflecting

adjustments for 2024 legislation passed by the General Assembly, primarily reducing individual

income tax revenue with expanded tax credits and deductions. This reduced expectations for General

Fund revenue subject to TABOR. The FY 2024-25 TABOR limit growth rate is 5.8 percent, down from

8.5 percent in FY 2023-24, based on population growth and inflation for calendar year 2023.

$7

$8

$9

$10

$11

$12

$13

$14

$15

$16

$17

$18

$19

$20

$21

$22

Referendum C

Five-Year Timeout

Period

Bars Represent Revenue Subject

to TABOR

Referendum C Cap

TABOR Limit Base

Amounts Above/(Below) the Referendum C Cap:

FY 2023-24: $1.41 billion

FY 2024-25: $328 million

FY 2025-26: $1.09 billion

TABOR Surpluses

June 2024 TABOR Outlook Page 22

The forecast does not include a potential TABOR (3)(c) refund obligation if Proposition FF revenue

exceeds the 2022 Blue Book estimate in FY 2023-24, and if voters do not approve a later ballot

measure permitting the state to retain this revenue. It is assumed that this refund obligation would

be administered differently than the TABOR (7)(d) refund obligations that arise when state revenue

exceeds the TABOR limit. There is no mechanism in current law to refund this excess to taxpayers.

Adjustments to revenue subject to TABOR and the TABOR refund obligation. This forecast

includes partially offsetting adjustments to revenue subject to TABOR and the TABOR refund

obligation stemming from the reclassification of portions of insurance premium tax revenue, gaming

revenue, and cigarette tax revenue.

In the single statewide audit for FY 2022-23, the State Auditor concluded, and the Attorney General

agreed, that insurance premium tax revenue that was credited to the Health Insurance Affordability

(HIA) Enterprise between FY 2020-21 and FY 2022-23 and previously accounted as TABOR exempt,

should be accounted as state revenue subject to TABOR. This forecast includes an upward

adjustment of $33.9 million to the TABOR refund obligation for FY 2023-24 to account for the under-

refunds of insurance premium tax revenue collected in prior years. House Bill 24-1470 ended the

annual diversion of this revenue from the General Fund to the HIA Cash Fund starting in the current

fiscal year.

This forecast also includes downward adjustments to General Fund and cash fund revenue subject to

TABOR as well as the TABOR refund obligation of up to $37.8 million starting in FY 2023-24, pursuant

to House Bill 24-1469. The bill requires that a portion of limited gaming revenue as well as the

portion of the statutory cigarette tax that is distributed to local governments be accounted as

revenue collected for another government, and therefore TABOR exempt. The forecast likewise

includes downward adjustments to cash fund revenue subject to TABOR and the TABOR refund

obligation to account for House Bill 24-1409, which credited a portion of employer support

surcharges to a new Workforce Development Enterprise, and to the existing Unemployment

Insurance Enterprise. These impacts are $49.5 million in FY 2023-24 and an estimated $24.5 million

annually thereafter.

Risks to the forecast. Estimates of the TABOR surplus and TABOR refund obligation represent the

amount by which state revenue subject to TABOR is expected to exceed the Referendum C cap.

Therefore, any error in the General Fund or cash funds revenue forecasts will result in an error of an

equal amount in the TABOR refund forecast. Any forecast error for inflation or population growth will

also impact the TABOR situation by resulting in higher or lower allowable growth in the Referendum

C cap.

TABOR refunds mitigate risks to the General Fund budget from the impacts of lower-than-expected

General Fund revenue. A reduction in General Fund revenue relative to forecast expectations will

result in a smaller obligation for TABOR refunds, and will impact the budget if the error is great

enough to erase the projected TABOR surplus. Relative to the March 2024 forecast, the revisions to

the TABOR surplus increase the budget risk from lower-than-expected General Fund revenue,

particularly in FY 2024-25. Likewise, error in the forecast for cash fund revenue subject to TABOR also

poses a risk to the outlook for the General Fund budget. Greater than expected revenue from cash

fund sources would increase the General Fund obligation for TABOR refunds, thereby reducing the

amount available for the budget.

TABOR refund mechanisms. TABOR refund mechanisms and expected refund amounts are shown

in Figure 3. Current state law includes two ongoing refund mechanisms for FY 2023-24 and beyond.

June 2024 TABOR Outlook Page 23

For FY 2023-24 through FY 2033-34, there are two additional temporary refund mechanisms,

established in Senate Bill 24-228, and for FY 2024-25 and FY 2025-26, there is one additional

temporary refund mechanism, established in Senate Bill 24-111. These refund mechanisms are

discussed below.

The first ongoing refund mechanism that applies for each year in the forecast period is the local

government reimbursement for homestead property tax exemptions for seniors, veterans with a

disability, and Gold Star spouses. Based on this forecast, this mechanism is expected to be used for

tax years 2024 through 2026.

The sales tax refund mechanism is expected to apply for tax years 2024 through 2026, as well, with

refund amounts based on taxpayer incomes in tax years 2024 and 2026, and identical refund

amounts in tax year 2025. The expected TABOR surplus collected in FY 2024-25 does not exceed the

identical refund threshold per taxpayer required to trigger the tiered refunds under Senate Bill 24-

228. Table 8 on page 25 presents estimated six-tier and identical sales tax refund amounts for tax

years 2024, 2025, and 2026.

Senate Bill 24-228 adjusts the mechanisms used to refund the TABOR surplus collected for FY 2023-

24 through FY 2033-34, and creates a new refund mechanism for any state TABOR surplus collected

for FY 2024-25 through FY 2033-34.

The bill raises the identical refund threshold for the sales tax refund mechanism from $15 to the

lowest amount listed for a family size of two for Colorado in the most recent table published in the

Internal Revenue Service instructions for Schedule A on itemized deductions. The most recent

amount, for tax year 2023, is $114.

The bill reactivates the temporary income tax rate reduction as the third refund mechanism after

property tax refund mechanisms. To refund a portion of the FY 2023-24 surplus, the income tax rate

for tax year 2024 is temporarily reduced from 4.40 percent to 4.25 percent. In subsequent years, the

amount of the income tax rate reduction that is triggered depends on the amount of the TABOR

surplus remaining after reimbursements to local governments for property tax exemptions.

The bill also creates a fourth refund mechanism, a temporary sales and use tax rate cut, which

reduces the state sales and use tax rates by 0.13 percentage points, starting in FY 2025-26, provided

the TABOR surplus collected in the prior year is at least $1.5 billion.

This forecast anticipates that the income tax rate reduction mechanism will not be triggered in tax

year 2025, and that the tax rate in tax year 2026 will be reduced from 4.40 percent to 4.28 percent,

based on the expected amounts of the TABOR surpluses remaining after property tax refunds in FY

2024-25 and FY 2025-26. The temporary sales and use tax rate cut is not expected to be activated in

the forecast period.

Senate Bill 24-111 establishes a new refund mechanism used to refund the TABOR surplus collected

for FY 2024-25 and FY 2024-25 through reductions in the assessed value of owner-occupied senior

primary residences for those who have previously qualified for the existing senior homestead

exemption but who are currently ineligible because they moved. Local governments’ foregone

property tax revenue as a result of the bill is reimbursed by the state government. Figure 3 includes

this mechanism with the “Property Tax Refunds” label. The mechanism is estimated to refund $50

million in property tax year 2025 and $43 million in property tax year 2026.

June 2024 TABOR Outlook Page 24

Figure 3

Expected TABOR Refunds and Refund Mechanisms

Dollars in Millions

Source: Legislative Council Staff June 2024 forecast.

*Includes $50 million and $43 million to be refunded from the FY 2024-25 and FY 2025-26 TABOR surpluses,

respectively, under Senate Bill 24-111.

Refunds made via property tax reductions reduce obligations that would otherwise be paid from

General Fund revenue. Refunds made via the income tax rate reduction or sales tax refunds are paid

to taxpayers when they file their state income tax returns. TABOR refund mechanisms are accounted

for as an offset against the amount of surplus revenue restricted to pay TABOR refunds, rather than

as a revenue reduction. Therefore, the General Fund revenue forecast does not incorporate

downward adjustments as a result of refund mechanisms being activated.

$166.2

$224.0

$225.5

$468.6

$400.4

$810.8

$104.1

$469.0

$0

$200

$400

$600

$800

$1,000

$1,200

$1,400

$1,600

2023-24 2024-25 2025-26

TABOR Refund for:

Refunded in Tax Year: 2024 2025 2026

Property Tax Refunds*

Income Tax Rate Reduction

Six-tier Sales Tax Refunds

June 2024 TABOR Outlook Page 25

Table 8

Projected TABOR Refunds via the Identical and Six-Tier Sales Tax Refund Mechanisms

Tax Year 2024 Refunds from FY 2023-24 TABOR Refund Obligation

Taxpayer Distribution by AGI

Single Filers

Joint Filers

up to

$52,000

$142

$284

$52,001

to

$107,000

$190

$380

$107,001

to

$171,000

$219

$438

$171,001

to

$242,000

$260

$520

$242,001

to

$319,000

$279

$558

$319,001

and up

$450

$900

Tax Year 2025 Refunds from FY 2024-25 TABOR Refund Obligation

Taxpayer Distribution by AGI

Single Filers

Joint Filers

up to

$54,000

$26

$53

$54,001

to

$110,000

$26

$53

$110,001

to

$176,000

$26

$53

$176,001

to

$249,000

$26

$53

$249,001

to

$328,000

$26

$53

$328,001

and up

$26

$53

Tax Year 2026 Refunds from FY 2025-26 TABOR Refund Obligation

Taxpayer Distribution by AGI

Single Filers

Joint Filers

up to

$55,000

$80

$160

$55,001

to

$113,000

$107

$214

$113,001

to

$180,000

$123

$246

$180,001

to

$255,000

$147

$294

$255,001

to

$336,000

$158

$316

$336,001

and up

$254

$508

AGI = Adjusted gross income.

Note: Amounts do not include estimates for reimbursements to local

governments for property tax exemptions.

June 2024 TABOR Outlook Page 26

Table 9

TABOR Revenue Limit and Retained Revenue

Dollars in Millions

Actual

FY 2022-23

Estimate

FY 2023-24

Estimate

FY 2024-25

Estimate

FY 2025-26

TABOR Revenue

1

General Fund

1

$17,463.6

$16,714.9

$16,545.8

$17,905.3

2

Cash Funds

$2,757.1

$2,770.0

$2,903.7

$2,978.5

3

Total TABOR Revenue

$20,220.7

$19,484.9

$19,449.5

$20,883.8

Revenue Limit

4

Allowable TABOR Growth Rate

4.2%

8.5%

5.8%

3.5%

5

Inflation (from Prior Calendar Year)

3.5%

8.0%

5.2%

2.5%

6

Population Growth (from Prior Calendar Year)

2

0.7%

0.5%

0.6%

1.0%

7

TABOR Limit Base

$13,445.2

$14,588.1

$15,434.2

$15,972.6

8

Voter Approved Revenue Change (Referendum C)

$3,212.1

$3,485.1

$3,687.2

$3,816.3

9

Total TABOR Limit / Referendum C Cap

3

$16,657.3

$18,073.2

$19,121.4

$19,788.9

10

TABOR Revenue Above (Below) Referendum C Cap

$3,563.4

$1,411.7

$328.1

$1,094.9

Retained/Refunded Revenue

11

Revenue Retained under Referendum C

4

$3,212.1

$3,485.1

$3,687.2

$3,816.3

12

Fiscal Year Spending (revenue available to be spent or saved)

$16,657.3

$18,073.2

$19,121.4

$19,788.9

13

Outstanding Underrefund Amount

5

$114.9

$33.9

14

Revenue Refunded to Taxpayers

$3,678.3

$1,445.6

$328.1

$1,094.9

15

TABOR Reserve Requirement

$499.7

$542.2

$573.6

$593.7

Totals may not sum due to rounding.

1

Revenue differs from the amount in the General Fund revenue summaries because of accounting adjustments across TABOR boundaries.

2

Following each decennial census, the April 1 census population counts are used instead of July 1 population estimates for purposes of calculating

the growth factors for the TABOR limit. Population estimates are used in all other years for purposes of the growth calculation.

3

This forecast assumes that all enterprises will maintain enterprise status. If an enterprise is disqualified, both revenue subject to TABOR and the

Referendum C cap will have equal upward adjustments.

4

Revenue retained under Referendum C is referred to as "General Fund Exempt" in the budget.

5

This amount represents under-refunds from prior years.

June 2024 General Fund Revenue Page 27

General Fund Revenue

This section presents the outlook for General Fund revenue, the state’s main source of funding

for discretionary operating appropriations. The three primary sources of General Fund revenue

are individual income tax, sales tax, and corporate income tax collections. Other sources of

General Fund revenue include excise taxes (retail marijuana, tobacco, and liquor), insurance

premium tax, pari-mutuel tax, court receipts, and investment income. Table 11 on page 35

summarizes final General Fund revenue collections for FY 2022-23 and projections for