281

Games and Culture

Volume 1 Number 4

October 2006 281-317

© 2006 Sage Publications

10.1177/1555412006292613

http://gac.sagepub.com

hosted at

http://online.sagepub.com

Building an MMO

With Mass Appeal

A Look at Gameplay in

World of Warcraft

Nicolas Ducheneaut

Nick Yee

Eric Nickell

Robert J. Moore

Palo Alto Research Center

World of Warcraft (WoW) is one of the most popular massively multiplayer games

(MMOs) to date, with more than 6 million subscribers worldwide. This article uses data

collected over 8 months with automated “bots” to explore how WoW functions as a

game. The focus is on metrics reflecting a player’s gaming experience: how long they

play, the classes and races they prefer, and so on. The authors then discuss why and how

players remain committed to this game, how WoW’s design partitions players into

groups with varying backgrounds and aspirations, and finally how players “consume”

the game’s content, with a particular focus on the endgame at Level 60 and the impact

of player-versus-player-combat. The data illustrate how WoW refined a formula inher-

ited from preceding MMOs. In several places, it also raises questions about WoW’s

future growth and more generally about the ability of MMOs to evolve beyond their

familiar template.

Keywords: multiplayer online games; player behavior; automated data collection;

game design

Introduction

World of Warcraft (WoW) recently took the world of online gaming by storm,

achieving levels of success previously unheard-of for U.S.-based massively multi-

player online games (MMOs). Whereas MMOs in Southeast Asia (and in particular

Korea) have routinely reported subscribers numbering in the millions (Woodcock,

2005), WoW far surpassed the pioneering EverQuest to place itself at the top of U.S.

charts, claiming more than 6 million subscribers worldwide (Blizzard, 2006).

Multiplayer game designers have long been in search of the “magic bullet” that

would help them break the coveted million subscribers mark. Numerous books (e.g.,

Bartle, 2004; Mulligan & Patrovsky, 2003) and research articles have been written

to either report on the workings of current MMOs or to offer suggestions about the

design of future games in the genre. Most of this past work however suffers from one

major limitation: a lack of large-scale, longitudinal data about the players’ behaviors

and their interaction with each game environment. Indeed, most of the current online

gaming research tends to be based on self-reports obtained from the players using

interviews (Yee, 2001), surveys (Seay, Jerome, Lee, & Kraut, 2004), or ethnographic

observations (Brown & Bell, 2004; Taylor, 2003). Except for Ducheneaut and Moore

(2004) and Ducheneaut, Yee, Nickell, and Moore (2006), no studies are based on

data obtained from the games themselves. Yet, game designers recognize the need

for a more systematic analysis of online games. At the recent Austin Game

Developers Conference for instance, Ubisoft’s Damion Schubert (2005) commented

that “[Game designers] don’t do enough data mining...we should let data analysis

lead design.”

In this article, we would like to answer Schubert’s call by reporting on our obser-

vations of more than 220,000 World of Warcraft characters we studied over 8

months. To address the lack of large-scale longitudinal data about MMOs, we devel-

oped a data collection infrastructure based on automated bots placed in the game

world to record information about each player’s whereabouts and activities over

time. We initially mined this data to better understand the social dimensions of play-

ing WoW: how often players interact with each other, the size and prevalence of

groups, and so on. These results are reported elsewhere (Ducheneaut et al., 2006). In

another contribution to this issue we also use our data to take a closer look at

guilds—persistent player associations that play an important role in multiplayer

games (Williams et al., 2006 [this issue]). For the purpose of this article, we will use

our data to describe instead how WoW functions as a game. In other words, we will

focus on metrics that reflect the players’ gaming experience: the time they spend at

each level, the classes and races they choose and their impact on their progression in

the game, and so on.

Surprisingly, this simple information has not been available from any MMO so

far. To bridge this gap we therefore decided to present a descriptive account of game-

play in WoW that would frame the other contributions to this special issue, provid-

ing important background information about the basic mechanics of the game. As we

will see, analyzing simple gameplay metrics also raises interesting questions about

the potential and inherent limits of the current “MMO formula.” Our contribution is

structured as a detailed case study, highlighting the tough balancing act of designing

a MMO with wide appeal and longevity.

We begin with a description of World of Warcraft for readers who might not be

familiar with the game. Immediately thereafter, we describe our research methods in

detail. We then describe the player’s gaming experience in WoW, breaking down our

analyses into three main areas: general play patterns (e.g., playing and leveling

time), in-game demographics (e.g., character classes, races, and gender), and activi-

ties (e.g., raids in instances, travel). Each section ends with a summary where we

282 Games and Culture

take a critical look at the data and discuss what WoW can teach us about designing

current and future MMOs.

World of Warcraft

World of Warcraft is based on a classic formula inherited from massively multi-

player online role-playing games (MMORPGs) that has been available for many

years. This game genre itself descends from earlier pen-and-paper role-playing

games such as Dungeons and Dragons (Fine, 1983). But whereas the game genre is

clearly not novel, WoW managed to expand its appeal significantly. After its launch

by Blizzard Entertainment in November 2004, it became rapidly clear that WoW was

going to surpass its predecessors’ size and success: The game sold out during its first

store appearance, attracting more than 240,000 subscribers in less than 24 hours

(more than any other PC game in history), and its subscriber base progressively

expanded to 1.5 million in March 2005, eventually reaching 6 million.

As in previous MMORPGs, WoW players first create an alter ego by choosing

from eight races and nine character classes. The character classes can be roughly

divided into types using familiar MMORPG archetypes (Ducheneaut & Moore,

2005): “melee”

1

classes that have to “tank” (take damage from) monsters (e.g.,

Warriors), “ranged” classes attacking from a distance with a bow or a gun (e.g.,

Hunters), and “casters” using various forms of magic, be it for “dps” (high damage

per second, such as a Mage) or for healing other party members (e.g., Priests). WoW

also has several “hybrid” classes combining two or more of these general abilities,

at the cost of being less proficient in each than a specialist of the same type (e.g.,

Paladins are a combination tank/healer but neither as good in melee as a Warrior nor

as proficient at healing as a Priest).

Players must also pick a “faction” to fight for: either the Alliance or the Horde. The

Alliance is comprised of the Night Elves, Humans, Dwarves, and Gnomes; the Horde

is comprised of the Orcs, Trolls, Taurens, and Undeads. Two of the nine classes are fac-

tion specific: Paladins can only be played with the Alliance, and Shamans are restricted

to the Horde. Choosing a faction affects a player’s experience significantly. On all

servers, characters cannot communicate across factions: The text typed by a Night Elf

for instance is automatically translated into gibberish by the system such that an Orc

nearby will not be able to understand it. The only way to communicate across factions

is through gestures (e.g., “/smile,” “/wave”). On player-versus-player (PvP) servers,

the impact of factions is even more important: In most of the game world, players can

attack members of the opposing faction at will. On player-versus-environment (PvE)

servers, player-versus-player combat is consensual, and players must turn on a “PvP

flag” to signal their intentions and enable other players to attack them.

Once their character is created, players can begin questing in Azeroth, a medieval

fantasy world broadly inspired from the works of authors such as J. R. R. Tolkien.

Ducheneaut et al. / Building an MMO With Appeal 283

Azeroth is an extremely vast and richly detailed 3-D environment. Players can fight

dangerous creatures (which as mentioned earlier may include other players) and

explore the game’s two continents alone or in the company of others while under-

taking quests. The game allows players to form temporary parties of up to 5 people

to tackle the most difficult quests and “raid groups” of up to 40 people for high-end

“instances” (dungeons). Completing quests and killing “mobs” (monsters) allows

them to earn “experience points” and reach progressively higher levels (60 is the cur-

rent maximum), improving the abilities of their character and acquiring powerful

items along the way.

The players also often join “guilds,” a more permanent form of association than

the temporary quest groups. A guild allows its members to differentiate themselves

from others with a “guild tag” below their name and by wearing a custom “tabard”

(a shirt with a color and icon selected by the guild officers). Guilds also have access

to a private group chat channel shared between the members. They are usually

described as the place where most of a player’s important relationships are formed

and frame a player’s social experience in the game (Seay et al., 2004; Taylor &

Jakobsson, in press; Yee, 2001)—a hypothesis tested in another contribution to this

special issue (Williams et al., 2006).

Interface

Players interact with the game and other players through an interface that closely

resembles those of previous online games (see Figure 1). At the bottom, several rows

of buttons allow players to perform game-related actions such as casting spells or

turning on special abilities. Players communicate with each other by typing text in

the “chat box” at the lower left of the screen. Several communication channels are

available: private, one-to-one “tells,” group chat, guild chat, “spatial” chat (heard by

all players within a certain radius), and finally “zone chat,” which reaches all the

players in a given zone of the game (zone chat is further subdivided into four chan-

nels: general, trade, local defense, and “looking for group”).

Servers and World Geography

To break down the game’s large subscriber base into more manageable units,

players must choose a specific server to play on. Each server can host a community

of about 20,000 players (there were 107 servers available in the United States at the

time of our writing). Three server types are available. The most common is PvE

where players cannot kill other players by default, unlike PvP servers. The third

server type is role-playing (RP) for players who prefer to “stay in character” during

the game.

On each server, the world of Azeroth is divided into two continents, each further

subdivided into zones. Players can freely travel across these zones, either on foot or

284 Games and Culture

by using various forms of public transportation (e.g., boats). However, each zone is

home to creatures of a particular level range (e.g., Tanaris is a 40 to 50 zone) and

could prove deadly to lower-level players. Each race has a capital city (e.g.,

Ironforge for the dwarves) that plays an important role as transportation hub and

place of commerce. Capitals also host an auction house where players can trade

objects on an open market. As such, they tend to be densely populated and frequently

visited.

Method

We began our study of WoW by observing the game world from the inside and

started playing right after its launch in November 2004. All authors created a main

character and several “alts” (secondary characters) on different servers. We picked

different character classes to get as broad an overview of the game as possible. We

joined guilds and participated in the community’s regular activities (quests—alone

or in groups, guild raids, PvP combat, etc.). This provided us with a rich qualitative

background to frame our analyses.

Ducheneaut et al. / Building an MMO With Appeal 285

Figure 1

World of Warcraft’s Interface

Source: World of Warcraft® provided courtesy of Blizzard Entertainment, Inc.

We later moved to a complementary, more quantitative research approach. WoW

has been designed such that its client-side user interface is open to extension and

modification by the user community. In addition, the game offers by default a

“/who” command listing the characters currently being played on a given server.

These two features have allowed us to develop a custom application to take a census

of the entire game world every 5 to 15 minutes, depending on server load. Each time

a character is observed our software stores an entry of the form:

Alpha,2005/03/24 13:45:30,Crandall,56,Ni,id,y,Felwood,Ant Killers.

The aforementioned represents a Level-56 Night Elf Druid on the server Alpha, cur-

rently in the Felwood zone, grouped (“y”), and part of the Ant Killers guild. Using

this application we have been collecting data continuously since June 2005 on five

different servers: PvE(High) and PvE(Low), respectively, high- and low-load player-

versus-environment servers; PvP(High) and PvP(Low), their player-versus-player

equivalents; and finally RP, a role-playing server. Overall, we observed 223,043

unique characters. We then used the accumulated data to compute a variety of met-

rics reflecting the players’ activities, which we present in the following.

Observations

General Play Patterns

Playing Time

We began our investigations with a simple question: How much time do players

spend in WoW? To calculate every character’s total playing time over a 1-week

period, we parsed through the census logs and accumulated each character’s time

spent in the game. On average, each character spent 615 minutes (N = 76,364, SD =

932.24), or about 10 hours, in WoW during that 1-week period. The median was 216

minutes, or about 4 hours. Although these statistics are significantly less than the

usage patterns reported elsewhere (Yee, 2006), it must be noted that the sample unit

in this data set is each character and not each player. Furthermore, the game mechan-

ics in WoW encourage creating Level 1 characters for storage or auction house trad-

ing purposes (i.e., “mules”), and this practice also affects the average playing time

of characters. For example, 14% of the sample consisted of Level 1 characters, and

of these, 38% did not advance above Level 1 during the 1-week period.

Nevertheless, comparing the average play times of characters of different levels

does reveal interesting relative differences. For example, we notice that play time tends

to increase by character level (Figure 2). This is probably due to a combination of sev-

eral factors. First of all, casual players may be discouraged to continue leveling and

stop playing. Second, players may increase commitment to playing as they increase in

286 Games and Culture

level. And finally, characters at the higher levels are probably those players who are in

the habit of playing more hours per week than those characters at the lower levels.

Another trend revealed by the graph is the commitment spike right before every

10th level. This begins with the spike at Level 9, the more prominent spikes at Levels

19 and 29, and the very large spike right before Level 40. For example, Level 39 char-

acters were played on average 1,032.43 minutes (N = 510, SD = 1,033.55), whereas

Level 40 characters were played on average 774.62 minutes (N = 952, SD = 877.27)

over the 1-week period. These commitment spikes are probably due to the distribu-

tion of new skills and talents in the game at different levels. There are more new skills

learned at every 10th level, and the talent tree is designed to allow access to a new tier

of talents at every 10th level. The spike right before Level 40 is more dramatic prob-

ably because characters also get access to traveling mounts at Level 40 in addition to

the new set of skills and talents. In other words, players spend more time playing

when they are just about to reach these high-reward levels. These findings are also

congruent with well-known behavioral conditioning principles (Skinner, 1938).

Leveling Time

We also calculated the average amount of time it takes to advance to the next level

from any given level. To calculate these averages, we extracted all leveling events.

Ducheneaut et al. / Building an MMO With Appeal 287

Figure 2

Playing Time by Character Level

A leveling event was defined as the time it took for a character to be observed at a

new level from their previous level. Because part of the first leveling event may have

occurred before the sampling window (i.e., a character was midway to Level 35

before the sampling window), we excluded the first leveling event we observed from

all characters.

In the plot of average leveling time by character level (Figure 3), we can observe

several trends. First, there is a mild step effect throughout. It takes characters less

time to reach an even level and more time to reach an odd level. This effect is again

more pronounced for Level 39 and Level 40. This step effect is probably due to the

distribution of new skills at even levels. Indeed, across all character classes, players

can “upgrade” their character with new abilities (more powerful spells, more dam-

aging melee attacks, etc.) only at even levels. As such, players interested in new con-

tent have more incentive to reach an even level quickly and less incentive to do so

for an odd level. Second, the time it takes to reach the next level increases in a lin-

ear fashion.

Overall, our data indicate that a player’s leveling time can be obtained with the

following equation:

Leveling Time (in minutes) = (Current Level × 14.0) − 44

If we assume that current Level 60s spent these amounts of time while reaching

Level 60, then the average Level 60 character has an accumulated play time of

288 Games and Culture

Figure 3

Average Leveling Time Across Character Levels

15.5 days—a total of 47 8-hour workdays, or roughly 2 full months of workdays

(Figure 4). Given that about 15% of all characters in WoW are Level 60, this means

that about 15% of characters have spent roughly 2 full months of workdays in WoW.

Again, it is hard to extrapolate this to actual players, but these statistics give a sense

of the large amount of time the average player spends in these online environments.

Rate of Advancement

Another measure of advancement is the number of levels a character advances in

a set period of time. This differs from leveling time in several ways. First of all, this

measure gives us a rate of advancement for each character. Because our calculation

of leveling times was an aggregate of leveling events, characters that leveled often

contributed more to the sample than characters who made only one or two levels.

Thus, creating a character-level metric would allow us to sidestep this confound.

And second, efficient leveling times may not be equivalent to a high rate of advance-

ment. After all, just because a character is efficient at leveling does not imply they

want to make 10 levels a week. Thus, characters who are inefficient at leveling may

have a higher rate of advancement than characters who are efficient at leveling.

To create this metric, we looked at the first 10 days and the last 10 days of August

2005 and included only those characters that were observed in both periods. This

was done so that we did not include new characters that started toward the end of the

Ducheneaut et al. / Building an MMO With Appeal 289

Figure 4

Average Accumulated Playing Time Across Character Levels

month—who presumably would have had less time to advance than those characters

that were already there at the beginning of the month. This sampling method yielded

83,020 characters.

We calculated a standardized measure of level advancement as follows. A character’s

raw advancement is simply the number of levels the character has advanced. In this case,

we subtracted the starting level from the ending level (i.e., end of month–beginning of

month). The problem is that over a 1-month period, a 10-level advancement by a

Level 1 character is much less significant than a 10-level advancement by a Level 50

character. In other words, the advancement needs to be qualified by the starting level.

The method we used to standardize character advancement was to calculate the aver-

age (and standard deviation) of advancement for every starting level. In other words,

compared with other characters who also started at Level 10, did this particular char-

acter level faster or slower than the average? We did this by calculating the z score

of advancement for every character based on the average and standard deviation for

their starting level.

There were two large groups of characters that were excluded from this analysis.

First, we excluded all characters who spent more than 90% of their time in a city. We

presumed that these were mules of one kind or another and they would simply intro-

duce too much noise. Namely, 6,393 (or 7%) of the original sample were excluded

this way. Then we excluded all characters who were already Level 60 because by

definition they could not advance anymore. This further excluded 14,408 (or 18.8%)

of the remaining sample. Thus, we ended up with a sample of 62,035 characters.

The means and standard deviations used to calculate the standardized scores men-

tioned earlier were actually derived from this sample so we were making consistent

comparisons.

The plot of average level advancement over the month of August 2005 by the

starting level is presented in Figure 5. It is interesting to note that players move very

quickly through the first 10 levels. The game is designed such that the players expe-

rience rapid progress and frequent rewards during their first play sessions—an

important design strategy to encourage continued play. The rate of progress is then

fairly stable up to Level 50, at which points it drops precipitously. As we discuss

later, by the time players reach this “endgame,” interest in WoW is not driven by

achievement through leveling anymore: Group activities (e.g., high-end raids in

instances to collect powerful items) replace basic quests, and gamers turn to reputa-

tion as a marker of achievement (Taylor, 2003).

Character Abandonment

Our longitudinal data collection method also allowed us to explore the rates of

character abandonment (Figure 6). In a sample of 75,314 characters observed in the first

week of June 2005, 46% were not observed in the first week of July 2005. The lower

level the character, the less likely they were observed again in July. For characters

290 Games and Culture

Ducheneaut et al. / Building an MMO With Appeal 291

Figure 5

Average Level Advancement by Level

Figure 6

Character Abandonment Rate by Character Level

Level 10 and below, 71% were not observed 1 month later. For characters Level 50

and above, only 16% were not observed 1 month later.

This high level of “churn” is not unheard of in MMOs. Industry veterans for

instance mention that only 40% of new subscribers remain in a game for more than

2 months (Mulligan & Patrovsky, 2003). Our numbers seem to corroborate this

information, and overall, it does not seem that WoW is necessarily more “sticky”

than its predecessors. It is also clear that the design of early levels is crucial because

players build up their commitment to the game as the level of their character

increases. Interestingly, the rate of character abandonment by level decreases lin-

early, whereas the design of the game apparently creates three progression stages

(Figure 5: initial fast progress, a fairly lengthy period of linear progress, and finally

slow progress). It would probably be valuable for game designers to experiment

with the interplay between these two curves, with the aim of fine-tuning the reward

structure such that the abandonment rate drops more quickly in the early stage of

the game.

Predictors of Character Abandonment

The character abandonment data allowed us to explore which variables were the

best predictors of character abandonment. From the first week of June, we derived

the following variables: whether the character was in a guild or not, the size of the

guild, the character’s play time, the character’s level, and the amount of time the

character spent in a group. We then ran a multiple regression with character aban-

donment as the dependent variables and the mentioned variables as the predictors.

Our model had an adjusted R

2

of .22 (Table 1). The best predictor of character

abandonment was the character’s level, followed by the character’s play time.

Characters in a guild were significantly less likely to abandon a character than char-

acters not in a guild, but interestingly, as long as a character was in a guild, the size

of the guild was not important. The amount of time a character spent in a group,

although a significant predictor, plays a trivial role when compared with the charac-

ter’s level and play time.

292 Games and Culture

Table 1

Standardized Coefficients of Variables Used in Multiple

Regression of Character Abandonment

Variable Beta tp

Guild size –.00 –1.0 .31

In guild –.09 –21.58 < .001

Play time –.19 –52.17 < .001

Level –.29 –74.07 < .001

Group ratio –.04 –9.71 < .001

Summary: A Fine-Tuned Reward Structure

Although WoW is often portrayed as a more “casual” game than its predecessors

(Kasavin, 2004), it is clear players still invest a significant amount of time in the

game. It is particularly interesting that play time is apparently greatly influenced by

WoW’s rewards structure (alternating levels with and without new skills, “mile-

stone” levels opening up new content such as mounts or talents, and a slow but

steady increase in required play time with each level). Part of WoW’s appeal might

be due to a carefully crafted path of advancement that is reminiscent of behavioral

conditioning principles (Skinner, 1938), where incentives and rewards are distrib-

uted to maximize player commitment. Once players are really invested into the

game, activities switch to a different endgame (Bartle, 2004) where the focus is less

on leveling up and more on accumulating powerful items and accruing reputation

(Taylor, 2003).

WoW is known to have been one of the longest MMOs to develop. Our numbers

show the time that was spent polishing the game’s mechanics might have been a

sound investment: Play time and level being the most significant predictors of char-

acter abandonment, it makes a lot of sense to optimize the game’s advancement

curve to give players the sense of achievement they are looking for and therefore to

keep them playing (and paying) as long as possible. But although WoW refined the

classic MMO formula to great success, we note that player churn remains high, indi-

cating that overall the game remains unattractive in the long run for a large number

of players. An important question then emerges: Has WoW reached an unbreakable

threshold and maximized its attractiveness to players? Or could the game (and

MMOs in general) be improved such that the 46% who leave after a month (and the

end of their free trial) remain longer?

In-Game Demographics: Class, Race, and Genre

As we mentioned earlier, WoW is based on a medieval fantasy universe (elves,

orcs, mages, warriors, etc.) that is now a familiar part of popular culture (Fine,

1983). A very large number of MMOs have used a similar template in the past, and

yet little is known about how these widespread archetypes are used by the players

and how they eventually affect their experience in the game.

To shed more light on this issue we used our census data to explore the popular-

ity of each race and class. In our sample (N = 76,364), Humans and Night Elves are

the most popular races (25% and 23%), far beyond any other, whereas Orcs are the

least popular (7%) (see Figure 7). Moreover the Alliance (the forces of “good” in

WoW) outnumbers the Horde (their “evil” counterpart) 2 to 1. These numbers are

particularly interesting considering that beyond minor race-specific game advan-

tages (e.g., Taurens have a small bonus in herbalism, Humans are slightly better with

swords, etc.), the differences between races are essentially cosmetic (e.g., Night

Ducheneaut et al. / Building an MMO With Appeal 293

Elves are tall, dark, and mysterious; Orcs are stocky, green, and somewhat intimi-

dating with large fangs; etc.; see Figure 8).

The players’ apparent reluctance to play “ugly” and “bad” characters could indi-

cate that despite the anonymity of virtual worlds and their potential for experiment-

ing with different identities (Turkle, 1997), social and cultural norms still shape an

individual’s choices in virtual worlds powerfully. In particular, the more “politically

correct” races and classes are apparently more popular.

The data on class preferences illustrate a different trend (Figure 9). Although the

differences are less pronounced than they are with races, a group of three classes

(Warrior, Hunter, and Rogue) stands out as the most popular. It is interesting to note

that, as we discussed elsewhere (Ducheneaut et al., 2006), these classes tend to be

the most “soloable” in the game—that is, they survive fairly well outside of groups

compared to “weaker” classes like the Priest who are more dependent on the support

of a tank taking hits while they cast spells at a distance.

In fact, WoW’s four healing classes (Shaman, Druid, Paladin, Priest) are all

among the least popular. This lack of popularity is all the more interesting consider-

ing that the presence of healers is one important characteristic setting MMOs apart

from other online genres (e.g., first-person shooters, FPS, or real-time strategy, RTS,

games). Although Blizzard designed these classes such that they can function as well

as possible independently (e.g., Priests are not limited to healing, they also have

offensive spells), it still looks as if support roles are less in favor than others. This could

be a reflection of WoW’s success at attracting players from other, more action-oriented

294 Games and Culture

Figure 7

Character Race Distribution

Ducheneaut et al. / Building an MMO With Appeal 295

Figure 9

Character Class Distribution

Figure 8

An Orc and a Night Elf

Source: World of Warcraft® provided courtesy of Blizzard Entertainment, Inc.

genres: Being less familiar with the notion of a healer, these newcomers might pick

the more offensive classes by default.

Gender-bending is a much discussed aspect of playing online games (Yee, 2005).

Although our bots obviously cannot collect information about each player’s real-life

gender, our census data still allow us to observe the distribution of character gender

across races and classes, revealing interesting divisions.

2

Overall, there is a higher

percentage of female characters on Alliance side than on Horde side (34.4% vs.

24.0%), see Figure 10.

A more fine-grained analysis shows the underlying difference. The top three races

with the most female avatars are Alliance races—Night Elves, Humans, and Gnomes

(Figure 11).

The gender distribution by class is also interesting (Figure 12). Among Priests, there

are almost equal numbers of male and female characters (40.4% vs. 59.6%). On the

other hand, there is a great gender disparity among Shamans (10.2% vs. 89.8%).

The gender distribution by class is interesting in that it seems to reflect stereo-

typical assumptions of those classes. For example, the classes with the highest

female ratio are all healing or cloth-wearing classes. Given that most of WoW’s play-

ers are male (Yee, 2005), this suggests that male players gender-bend at different

rates depending on the class they choose. In other words, male players who play

Priests are more likely to gender-bend than those who play Warriors. Thus, real-

world stereotypes come to shape the demographics of fantasy worlds. The aesthetic

preferences we mentioned earlier in the context of races also seem to be reinforced

when taking in-game gender into account, with players clearly favoring the “sexy”

296 Games and Culture

Figure 10

Gender Distribution by Faction

female Night Elves (source of much derision in the player community, with stories

of male teenagers mesmerized by these characters’ “/dance” animation) to their per-

haps less visually pleasing Dwarven counterparts. As in earlier, text-only environ-

ment, WoW can therefore be a place for “identity tourism” that far from projecting

a balanced view of gender and race instead perpetuates the domination of certain

canons of morale and beauty (Nakamura, 2000).

Ducheneaut et al. / Building an MMO With Appeal 297

Figure 11

Gender Distribution by Race

Figure 12

Gender Distribution by Class

Play Time and Class

We also compared the average weekly play times of different classes (see Figure 13).

The range between most and least weekly play times was about 3 hours, F(8, 76,363) =

39.41, p < .001. Rogues spend about 3 more hours online than Warlocks each week.

Of course, it is difficult to draw any firm conclusion from these differences due

to the lack of data about each player’s motivations. It could be that Rogues are eas-

ier to play and encourage their players to stay longer in the game, or it could be that

“hardcore” players who play longer tend to choose Rogues more than any other

class. Still, these data allow us to explore an important phenomenon in more detail:

“gold farming” (Lee, 2005). A farmer is “a general term for a person who acquires

in-game currency in a MMO through collecting items and money that can be

obtained by continually defeating enemies within the game” (Wikipedia, 2006). This

currency is then often sold for real-world currency such as the U.S. dollar.

Farming is a controversial practice, and our goal here is not to discuss it in depth.

Our data however can help measure the prevalence of the phenomenon. Indeed, our

experience in the game and discussions on Blizzard’s forums indicate that farmers

predominantly choose Rogues. This makes practical sense: Rogues have a “stealth”

ability allowing them to sneak past low-value mobs and go directly for the most

profitable items; they also generate high damage and can run through many mobs

quickly, increasing the player’s chances of getting a valuable “drop.” In parallel,

investigations into the farming business indicate that professional farmers spend a lot

of time in the game, sometime to the extent that a character might be constantly

online and played in shifts by two or more individuals (Lee, 2005).

298 Games and Culture

Figure 13

Average Play Time by Class

In an attempt to identify farmers we isolated characters with the highest play

time. If we focus on the top 99% percentile, we obtain 2,413 characters with the fol-

lowing class distribution (Figure 14). The time cut-off at the 99% mark was 5,532

minutes over a 2-week sample, which amounts to 7 hours online per day.

The trend is even sharper if we only take the top 99.9% percentile of play time

(n = 245). Here the cut-off is 12,637 minutes—that is, a considerable 15 hours per day.

Rogues and Hunters together account for 85% of characters in that range (Figure 15).

The large asymmetries we see here cannot be due entirely to chance and tend to

corroborate the hypothesis that Rogues (and Hunters to a lesser extent) are used

Ducheneaut et al. / Building an MMO With Appeal 299

Figure 14

Distribution of Classes at the 99th Percentile of Play Time

Figure 15

Distribution of Classes at the 99.9th Percentile of Play Time

beyond what even the most hardcore players would do. Focusing on the most

extreme pattern, we find 245 potential farmers across five servers in a 2-week period.

Although the numbers are large, they certainly do not represent the “farmer inva-

sion” that many players fear. Still, there is little doubt a significant farming industry

already exists. If we extrapolate our information to the 107 U.S. servers in operation,

there could be potentially 107 / 5 x 245 = 5,200 farming characters in operation in

the United States alone.

Class Abandonment

Using the measure of character abandonment described earlier, we tabulated aban-

donment rates by class (Figure 16). There were significant differences, F(8, 75,313) =

33.51, p < .001. The analysis showed that Shamans are the class most likely to be aban-

doned (54%), whereas Paladins are least likely to be abandoned (42%).

There are two ways of interpreting these data. One is to focus on the game

mechanics themselves, which might lead us to think that Shamans are abandoned

because the class is not enjoyable to play, whereas Paladins have a low abandonment

rate because the class is very enjoyable. Another way is to focus on the personality

and motivational differences between players who choose different classes in a

game. This might lead us to wonder whether players who choose Shamans are very

different from those players who choose Paladins. Data from the Daedalus Project

show some of these potential motivational differences (Yee, 2005). For example,

players who choose to play Shamans tend to be significantly more competitive than

300 Games and Culture

Figure 16

Character Abandonment Rate by Class

players who choose to play Paladins. These two sets of data do not make clear the

individual contribution of these two factors, but it must be kept in mind that the cen-

sus data we are exploring is produced by the interaction between game mechanics

and player preferences.

Rate of Advancement by Class

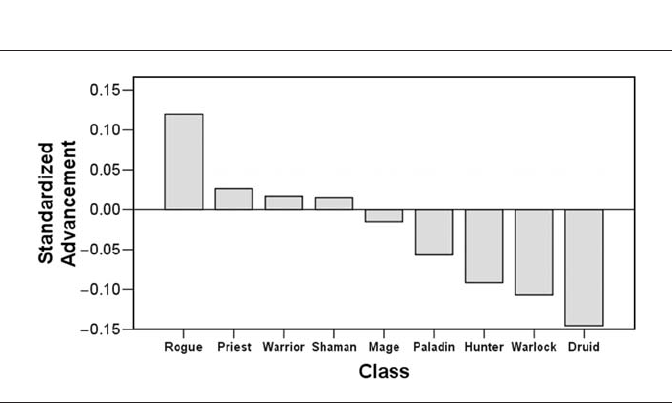

There were also significant differences between rate of advancement among the

different classes, F(8, 62,034) = 42.61, p < .001 (see Figure 17). In particular, Rogues

leveled significantly faster than all other classes (Tukey post hoc test, ps < .001).

But to a certain extent, this conflates level advancement by playing time. For

example, Rogues actually also spend more time playing than most other classes. If

we control for playing time, we get a more precise sense of actual “rate” of leveling

(Figure 18). The huge drop for the Rogue means that most Rogues play more than

other characters and that this is what leads to their higher level advancement, but

once we take their higher playing time into account, they are not the fastest levelers

overall. The actual fastest levelers are Priests, but because they spend less time play-

ing, their actual level gain is less than Rogues.

Again, it is hard to tease out the relative contributions of game mechanics and

player motivations. Note however that two of the fastest leveling classes, Priest and

Shaman, are among the least popular healing category we discussed earlier. If we

hypothesize, as we did earlier, that healing classes are not popular among MMO new-

comers, we would expect these classes to be played by more experienced players and

Ducheneaut et al. / Building an MMO With Appeal 301

Figure 17

Standardized Advancement Rate by Class

therefore to level faster. Our numbers are far from conclusive but tend to support this

possibility.

Rate of Advancement by Race

The race differences were a little more interesting in that the top four races were

the Horde races and the bottom four races were the Alliance races (Figure 19). The

split was surprisingly clean. The split also closely matches data from the Daedalus

Project (Yee, 2005) on motivational differences between players who choose Horde

versus Alliance.

Again, there are differences in playing time among characters of different races.

Notably, Night Elves play just as much as Undead, which is surprising given the

advancement difference. If we plot out the average level advancement controlling for

playing time, we see this difference more clearly (Figure 20).

So the Undead level the most over a month, spend the most time playing, and are

actually also the fastest levelers. Night Elves on the other hand spend almost as much

time playing but are the slowest levelers of all the races. This matches our experi-

ence in the game and conversations we have seen on player forums. New and less

experimented players tend to pick “friendly” races initially: The forces of “good”

portrayed in popular movies like Lord of the Rings, for instance. The Alliance races

“look good” and can be more attractive at first. Conversely, achievement-oriented

MMO players tend to pick the “bad guys,” either because they already tried the other

side and want to experience something new or quite often, explicitly to avoid playing

302 Games and Culture

Figure 18

Standardized Advancement Rate by Class Controlling for Play Time

with noobs

3

(a derogatory term for inexperienced players). Our numbers clearly

show this Horde bias toward achievement.

Coupled with our previous data on class popularity and leveling rates, a picture

emerges reflecting a fairly clean fracture between two player populations in WoW.

Ducheneaut et al. / Building an MMO With Appeal 303

Figure 19

Standardized Advancement Rate by Race

Figure 20

Standardized Advancement Rate by Race Controlling for Play Time

On one hand, a group of newcomers to the genre picks “action-oriented,” solo

classes from the better-looking races of the Alliance (Night Elves, Humans). On the

other hand, a group of more experienced and achievement-oriented players selects

more group-oriented “support” classes from the most “evil” races of the Horde

(Undeads, Orcs). Of course this is clearly an oversimplification: We simply want to

point out two broad trends reflecting the diverse ways in which players relate to their

race and class. The fairly wide number of options available in WoW supports this

differentiation and probably helps attract a broad range of players. We wonder how-

ever if Blizzard intended such a clean cut between the two factions. Indeed, it can

have some negative consequences in terms of game balance. On many servers, for

instance, the Horde/Alliance imbalance seriously limits the number and quality of

matches in the Battlegrounds (arenas where groups of players from each faction col-

lectively battle against each other, leading to valuable rewards; battlegrounds open

up only when a large enough and balanced number of players from each side sign

up for them).

Summary: Redefining the Meaning of Classes, Races, and Gender

The data presented in this section highlight the importance of taking into account

factors that exist outside of the game—player gender, personality, and motivations—

when making sense of data within the game. For example, the differing leveling rates

of classes are not solely based on their effectiveness inside the game. Players select

classes on the basis of their own motivations of play, and the leveling rates we see

closely match how achievement oriented the players are for different classes (Yee,

2005).

Still, it remains possible to use in-game demographic data exclusively to identify

interesting trends. The surprisingly large number of Rogues played almost continu-

ously for instance is probably an indicator of gold farming activities. The clean split

in leveling rates between Horde and Alliance also illustrates how players can easily

self-segregate into groups of fairly homogenous backgrounds and aspirations, poten-

tially leading to game imbalances. And finally, the distribution of races and classes

clearly indicates strong preferences for characters fitting stereotypical canons of

morale and beauty, perpetuating offline norms in virtual environments.

Activities

Traveling in Azeroth

The log samples also allowed us to explore how players “consume” the game

content, that is, which areas of the game world they visit and how often they do so.

We began by counting the number of different zones each character had been in over

a period of 1 month. One potential confound we tried to deal with was accidental

304 Games and Culture

zone logging due to flight paths. We did not want to count a zone if a character was

simply flying through that zone when the census was taking place. To resolve this,

we only counted a zone as being unique if a character is seen in that zone for at least

two consecutive census snapshots.

Our data showed that zone count increased gradually over level with noticeable

spikes at Levels 19, 39, and 49. The most noticeable of these spikes occurs at Level 39.

This matches the spike in playing time. Thus, it seems reasonable to hypothesize that

players play harder at these levels and are more likely to spend more time playing as

well as being more willing to move into a larger variety of zones. Because average

zone count correlates highly with time played (r = .81), we replotted the graph con-

trolling for play time to give a better sense of how widely traveled characters are at

different levels (Figure 21). Most of the graph’s features remained the same, with

one important exception: The data showed a sharp drop for Level 60 characters. In

other words, Level 60 characters spend significantly more time playing than lower-

level characters, but if we account for playing times, Level 60 characters actually are

less adventuresome than the average Levels 50 to 59 characters. In fact, the travel

patterns of Level 60 characters approximate those of Levels 43 to 44 characters. This

is probably due to the shift from quests to high-end instances as the latter are located

in a limited number of areas.

Ducheneaut et al. / Building an MMO With Appeal 305

Figure 21

Average Zone Count by Character Level Controlling for Play Time

We also tabulated zone populations. Unsurprisingly, Ironforge and Orgrimmar

(both major trading posts and flight hubs for each faction) were the most populated

zones (Figure 22).

It is interesting to note important differences in the popularity of similar zones,

however, as it probably reflects the impact of their design on player activities.

306 Games and Culture

Figure 22

Average Zone Count

Darnassus, for instance, is also a capital city (for the Night Elves), offering services

that are entirely similar to Orgrimmar and Ironforge (large number of merchants,

trainers, a bank, etc.). Yet it is one of the least visited places in the game, which is

all the more surprising considering Night Elves are the most popular race. Its loca-

tion probably explains this low use: Darnassus is an isolated island in the upper left

corner of Azeroth, connected to the mainland by a single flight point or by an even

slower boat. As such, Darnassus illustrates how players always try to optimize their

play time: A Night Elf faced with a lengthy trip back to Darnassus for training or a

much shorter one to Ironforge will most probably choose the latter. No matter how

beautifully designed a zone is (and Darnassus is beautiful, with a unique “elvish”

aesthetic), players will apparently favor expediency over sightseeing.

In a similar vein, some zones catering to the same level ranges are visited very

unevenly. Stranglethorn Vale or STV (Levels 35 to 45 approximately) is much more

popular than Desolace (same range). Location probably plays a role here again: STV

is connected to other areas by two major flight points and several maritime routes.

The density of game content available is also a probable factor: STV offers a large

number of quests, most grouped in tight areas, which facilitates “grinding” experi-

ence points at an accelerated rate. Finally the Horde and Alliance flight points and

quest areas are tightly packed, which on PvP servers almost guarantees opportuni-

ties for player-to-player combat (and leads to STV being called, among other things,

“Ganklethorn Vale”—being “ganked” is the act of being attacked by players of the

opposing faction, often of higher level, while conducting other activities).

So overall, despite offering a vast world with many opportunities for travel, activ-

ities in WoW appear to be concentrated into a surprisingly small number of areas.

This should not be particularly surprising considering the players’ tendency to opti-

mize their play time. The fact that some zones are restricted to high-level players and

that there are fewer of them than beginners is also an important factor, but it does not

explain all the difference. Our data indicate the crucial importance of carefully

designing an MMO’s transport network: A tough balancing act must be achieved

where players still feel a sense of space and travel yet transportation time is mini-

mized to guarantee maximum accessibility to all areas.

The Endgame: Playing WoW at Level 60

Anecdotally and from some of our earlier data, the game at Level 60 is entirely

different from the game pre-60. Above all, level advancement is no longer the goal,

and most guilds become raid and instance oriented. We wanted to explore this shift

in more depth. To do so, we decided to reuse social network metrics from an earlier

study (Ducheneaut et al., 2006). In particular, we calculated the degree (number of

guildmates played with), centrality (proportion of guildmates played with), and

weight (overall time spent in groups) for each character and found their means

according to their level range.

Ducheneaut et al. / Building an MMO With Appeal 307

The data suggest a sudden shift at 60 rather than a gradual change, Fs(6, 102,242) >

3,700, ps < .001. Figures 23, 24, and 25 are graphs showing the difference for the

three metrics mentioned.

It is quite clear that at Level 60, WoW becomes a much more intensely social

game—an interesting contrast to the earlier stages of the game where a large major-

ity of time is spent alone, as our previous analyses revealed (Ducheneaut et al.,

2006). At Level 60, characters progress not through experience points but through

the acquisition of more and more powerful items (“epic gear”). “Epics” are

“dropped” by creatures in instances that to be defeated require groups of at least 5

but more often 20 or even 40 tightly coordinated players. These high-end raids are

significant undertakings requiring a lot of planning and in-game communication—

the latter being clearly reflected in our social network metrics.

As such, it is clear that WoW is in some sense two games in one. For some play-

ers the game does not really begin until they reach the endgame. The leveling nec-

essary to get there is simply something to be endured and minimized, which goes a

long way toward explaining why so many players do not group and level up quickly

in the early stages of their character’s development (Ducheneaut et al., 2006). Others

make a more leisurely progress through the game and enjoy the early stages of the

game. They might then find the endgame too hardcore (Taylor, 2003) for their taste

and either leave, start a new Level 1 character, or transition to a new play style and

join other “raiders” in high-end instances.

We wondered however how many of the Level 60 characters really manage to

organize and participate in these complex high-end raids. Indeed, Blizzard has

openly focused a great part of their ongoing design efforts on adding more high-end

308 Games and Culture

Figure 23

Average Degree by Level Range

instances, and some have criticized them for favoring hardcore players over their

more casual counterpart. This debate is neither new nor specific to WoW and reflects

the difficulty of designing a game appealing to a wide audience. To shed more light

on the issue, we tried to assess how many characters participated in high-end con-

tent such as Molten Core or Zul’Gurub.

In the month of January, we tracked 223,043 characters. Of these, 11,098 (5%)

spent time in high-level raid content. The majority of these were Level 60 (as

Ducheneaut et al. / Building an MMO With Appeal 309

Figure 24

Average Centrality by Level Range

Figure 25

Average Connection Weights by Level Range

expected)—99.4%. The remainder were levels 56 to 59 (0.06%). Of all the Level

60s, 30% have spent time in raid content. On average, characters who spent time in

raid content spent 310 minutes (about 5 hours) over the month of January in raid

content.

Pushing our analyses further, we also note that of those who spent any time in raid

content, 28% spent less than an hour in it. In other words, only 72% of these char-

acters spent more than an hour in raid content. Thus, 3.6% of all observed charac-

ters spent more than an hour in raid content over the month of January.

These numbers might appear quite low at first, and they tend to substantiate crit-

icisms we mentioned earlier: namely, that a disproportionate share of design effort

is spent on content consumed by a tiny minority of players. However, we have to

bear in mind that the 3.6% of the population we identified are most probably among

the most “die-hard” players. As in any online community (Kim, 2000), this core

player base is probably the most vocal and quite influential: They attract new play-

ers through word of mouth and often act as “glue” between their more casual coun-

terparts. From a marketing standpoint, it therefore makes sense to keep them as

happy as possible. But on the other hand, it also shows, like some of our earlier

analyses in this article, that WoW is less casual than claimed: The game is clearly

designed to steer players toward more and more hardcore activities requiring a lot

of time and effort. In this, WoW is not different from any of its predecessors in

the genre.

Server Differences: The Impact of Open PvP

Player-versus-player combat is notoriously hard to design for a MMO (Bartle,

2004), but Blizzard embraced it right from the beginning. A large number of servers

are open PvP (players can be attacked almost at will in most of the game’s areas).

Even in player-versus-environment or role-playing servers, players have the option

to turn on a PvP flag signaling their willingness to fight with other players. All

servers also feature Battlegrounds (Warsong Gulch, Arathi Basin, and Alterac

Valley) where players can sign up for large-scale faction warfare.

We wanted to explore whether open PvP environments strongly differ from their

alternatives. The observed difference was largely driven by the PvP server,

F(2, 140,843) = 171.69, p < .001. Characters on PvP servers played about an hour

more (~70 minutes) over a 1-week period than characters from the RP and the two

PvE servers we observed, ps < .001. The average character play time in this sample

was 11.2 hours, about a 10% difference of the mean (Figure 26).

Although one might expect that characters on PvP servers could be more inclined to

be in a guild (for safety in numbers, etc.), the data did not bear this out. Overall, guild

involvement rates were comparable across server types and level ranges (Figure 27).

We might have also expected that guilds on PvP servers would be larger in general

given the demands on survival. This also did not bear out with the data. We created a

310 Games and Culture

list of every guild that was observed and the total number of unique characters

observed to have that guild tag. There were significant differences, F(2, 140,842) =

1221.22, p < .001, but it was between the RP server and the other two server types,

p < .05 (Figure 28).

Still, characters on the PvP server were observed to be in a group more often than

characters not on PvP servers, F(2, 140,842) = 202.49, p < .001. Overall, the differ-

ence was about 30% versus 25%. The increased grouping ratio seems to be reflected

across all 60 levels (Figure 29).

Messages on forums seemed to suggest that it was harder and took longer to level on

PvP servers than on non-PvP servers. Although we did find a significant difference,

F(2, 149,231) = 501.31, p < .001, it was almost in the opposite direction. Controlling

for character level, characters on the PvP server leveled faster (M = 189.78, SE = .63)

than characters on PvE (M = 219.65, SE = .64) or RP servers (M = 211.74, SE = .84),

ps < .001 (Table 2). In fact, perhaps the need to level is more salient on PvP servers than

non-PvP servers and outweighs the difficulty of leveling: After all, it is only at Level 60

that the probability of being outmatched by an opponent of higher level is reduced to 0.

Summary: Designing Content for All Player Types

Our data on player activities revealed several interesting trends. First, Azeroth is

an unevenly traveled world. The density of content yielding “fast xp” and the game’s

transportation network both steer players to a few popular areas. Second, WoW is

really two games in one: A player’s experience shifts dramatically once they reach

Level 60. Much more coordination and group play are required to tackle the difficult

Ducheneaut et al. / Building an MMO With Appeal 311

Figure 26

Differences in Play Time Across Servers

Note: PvE = player versus environment; RP = role-playing; PvP = player versus player.

high-end instances. In fact, it seems only a tiny fraction of players ever get to access

this content. Ultimately, WoW is therefore a hardcore game, much like its predecessors

in the genre. Its success has probably more to do with the smooth gameplay it offers

in the early stages of a character’s life than the inclusion of more casual gamers.

WoW is also one of the first MMOs to embrace PvP on a large scale, and the

impacts of this decision are surprisingly limited. Our data indicate players on PvP

312 Games and Culture

Figure 27

Percentage of Guilded Characters Across Server Types and Level Ranges

Figure 28

Average Guild Size Across Server Types

Note: PvE = player versus environment; RP = role-playing; PvP = player versus player.

Note: PvE = player versus environment; RP = role-playing; PvP = player versus player.

servers might be a bit more achievement oriented than others. Most interestingly,

PvP combat apparently encourages players to group more and play more, suggest-

ing that shared adversity might be a positive force in the social life of a MMO if it

is correctly implemented.

Conclusion

The gameplay metrics we analyzed in this article allowed us to paint a broad pic-

ture of gaming activities in WoW. Basic in-game demographic information, such as

Ducheneaut et al. / Building an MMO With Appeal 313

Table 2

Leveling Time Across Sever Types (Dependent Variable: Level Time Mean)

Level

Server Type 1 to 10 11 to 20 21 to 30 31 to 40 41 to 50 51 to 60 Total

Player-versus-environment 64 221 397 585 834 1,073 227

(medium)

Role-playing (high) 59 218 381 580 853 1,099 225

Player-versus-environment 55 190 327 523 703 945 231

(high)

Player-versus player-(high) 53 190 348 550 752 991 240

Total 53 190 348 550 752 991 240

Figure 29

Average Group Ratio Across Server Types

Note: PvE = player versus environment; RP = role-playing; PvP = player versus player.

the population for a class or race, can reveal important forces at work that ultimately

affect a player’s experience. Our data also reveal some of the potential factors behind

WoW’s success and others that may threaten the game’s appeal in the long run.

Above all, it appears WoW’s players are not much more casual than in other

MMOs. WoW still requires a significant time commitment, which apparently 6 mil-

lion subscribers are willing to make. The attractiveness of the game could have a lot

to do with its fine-tuned incentives and rewards structure, reminiscent of behavioral

conditioning. Although many earlier MMOs were criticized for requiring long,

repetitive grinding sessions (often in groups) early in the game to progress, WoW

seems instead to have been optimized such that players experience more of a “flow”

experience (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990), with challenges increasing gradually and

rewards always in sight. As noted virtual worlds designer Raph Koster (2005) pro-

posed, “fun is a process.” And indeed, with WoW’s mechanics being almost entirely

identical to predecessors like EverQuest, it is quite probable that a difference in

process is at the root of WoW’s spectacular growth.

Our data also point at other potential factors contributing to WoW’s wide appeal. In

particular, it is quite probable that WoW managed to attract gamers from competing

online genres (e.g., first-person shooters and real-time strategy games) and even from

offline alternatives (especially medieval fantasy, single-player games). Before launch-

ing WoW, Blizzard already had a strong reputation for building high-quality games

(e.g., Diablo, a single-player medieval fantasy game, and the Warcraft RTS series), and

part of their fan base could easily have migrated to their new MMO on the strength of

this reputation alone. Looking at the relative distribution of classes in the game, it is

also clear that a very large number of players favor the most action-oriented arche-

types. By making these classes accessible and enjoyable to play with or without a

group, Blizzard probably managed to break the MMORPG mold and tapped into the

FPS, RTS, and single-player gaming populations. Our metrics also indicate that

Blizzard managed to integrate PvP into the core mechanics of the game without unbal-

ancing it. The opportunity to compete against other human players instead of com-

puter-controlled monsters probably reinforced WoW’s attractiveness to FPS players.

But WoW returns to a well-known MMORPG formula in the late stages of a

player’s progression. WoW’s endgame centers on large-scale raids requiring intense

coordination between a large number of players (up to 40). These can be incredibly

time-consuming: Beyond the 3- to 4-hour time commitment for the raid itself, count-

less hours must be spent beforehand to prepare for the run (e.g., to acquire items pro-

viding increased protection against each instance’s “boss”). Our social network

metrics clearly show how this need for increased coordination translates into more

frequent social contacts between the players. Although this may sound desirable at

first, it is important to keep in mind that most WoW players progress through the

game alone (Ducheneaut et al., 2006), and the sudden switch to large-scale groups

could be jarring. If, as we hypothesized earlier, many of WoW’s players migrated

314 Games and Culture

from other game genres where group experiences are generally “lightweight” (e.g., in

an RTS, simply sign in and play against a human opponent right away), the problem

would be reinforced. Symptoms of this disconnect could already be visible. As we

described, only a small fraction (30%) of all Level 60 characters manage to access

high-end content. This coupled with the high churn rate we observed indicate that

WoW suffers from the same retention problems as its predecessors (Mulligan &

Patrovsky, 2003). Although a steady stream of “newbies” coming from competing

game genres is currently sustaining an explosive growth, the situation could devolve

dramatically should this supply of newcomers be exhausted. Of course, it could also

be that this market is growing fast enough that WoW will never have to face this issue.

Our analyses have also shed some light on basic player preferences in MMOs. In

particular, the balance between populations of each class, race, and gender reveals

some interesting aesthetic and moral preferences. For instance, a very large majority

of players prefer playing races that conform to highly stereotypical canons of

beauty (e.g., the tall, lean, and often scantily clad female night elves). They also pre-

fer the “good” side (the Alliance) to their “evil” counterpart (the Horde) 2 to 1—even

though these differences are simply cosmetic, and Blizzard explicitly designed each

faction such that both could be morally ambiguous, and heroes could be found on

each side. Some characters from the Horde, for instance, are far from evil. The

Taurens are peaceful nature lovers, and many of their quests involve preserving

nature and animals. The Orcs are trying to overcome their past as tools of evil and

are consequently concerned about behaving with honor and doing the right thing. In

Orgrimmar (the Orcs’ capital), there is an orphanage just like there is in Stormwind

(the Humans’ capital). By contrast, some of the Alliance quests involve murder and

extortion. But despite these backstories (to which perhaps few players really pay

attention), players overwhelmingly prefer siding with the stereotypical “good.”

This imbalance becomes all the more interesting when rates of advancement are

compared across factions. Indeed, Horde players apparently progress faster through

the game. Coupled with survey data (Yee, 2005) and conversations with WoW play-

ers, a common pattern emerges. It seems as if players (and in particular, MMO new-

comers) tend to choose the “good” side for their first experience with the game. As

they gain more experience however (or as they join with experience from a previous

MMO), they migrate to the “bad” side to segregate themselves from newbies. It is

interesting to see how experienced gamers consciously use the unattractiveness of

the Horde as a barrier to entry into their world. It is also quite probable that Blizzard

did not anticipate such segregation, and it highlights the ever-changing and complex

interplay between a world’s design and its players’ choices.

There is of course much more to say about WoW. The contributors to this special

issue investigate a wide range of topics that we hope will benefit from the background

information we provided in this article. In the meantime, we plan to continue our data

collection effort to help scholars and practitioners understand MMOs from the inside.

Ducheneaut et al. / Building an MMO With Appeal 315

Notes

1. Because of World of Warcraft’s (WoW’s) similarities with earlier massively multiplayer online role-

playing games (MMORPGs), veteran players have imported many cultural practices that originated in

these earlier environments. The most noticeable is the large MMORPG lingo used to describe roles and

activities in the game world. We will define the most important notions in this introduction so that we can

use the player’s terminology unchanged in later parts of this article.

2. The gender of characters is not one of the variables that can be retrieved via the “/who” command.

The server does store this information of course, but it is only accessible by client-side interface if the

character is within targetable range. In an attempt to gather information about the gender of characters,

we placed our census bots in central city locations. The bots cycle through their most recent census data

and try to target everyone in that list. Characters who are found then have their gender noted. The gender

information thus accumulates over time. Our data set from October had a gender identification rate of

32.1%, and it is these data we are using here.

3. See this thread on Daedalus, for instance: http://www.nickyee.com/daedalus/archives/001366.php

References

Bartle, R. (2004). Designing virtual worlds. Indianapolis, IN: New Riders Publishing.

Blizzard. (2006). Customer base reaches 6 million players worldwide as Blizzard Entertainment® pre-

pares its award-winning MMORPG for continued growth in Europe. Retrieved July 27, 2006, from

http://www.blizzard.com/press/060228.shtml

Brown, B., & Bell, M. (2004). CSCW at play: “There” as a collaborative virtual environment. In

Proceedings of CSCW’04 (pp. 350-359). New York: ACM.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. New York: HarperCollins.

Ducheneaut, N., & Moore, R. J. (2004). The social side of gaming: A study of interaction patterns in a

massively multiplayer online game. In Proceedings of the ACM conference on Computer-Supported

Cooperative Work (CSCW2004) (pp. 360-369). New York: ACM.

Ducheneaut, N., & Moore, R. J. (2005). More than just “XP”: Learning social skills in massively multi-

player online games. Interactive Technology and Smart Education, 2, 89-100.

Ducheneaut, N., Yee, N., Nickell, E., & Moore, R. J. (2006). “Alone together?” Exploring the social

dynamics of massively multiplayer online games. In Proceedings of the ACM conference on Human

Factors in Computing Systems (CHI 2006) (pp. 407-416). New York: ACM.

Fine, G. A. (1983). Shared fantasy: Role-playing games as social worlds. Chicago: University of Chicago

Press.

Kasavin, G. (2004). World of Warcraft. Retrieved August 8, 2005, from http://www.gamespot.com/pc/rpg/

worldofwarcraft/review.html

Kim, A. J. (2000). Community building on the Web. Berkeley, CA: Peachpit Press.

Koster, R. (2005). A theory of fun for game design. Scottsdale, AZ: Paraglyph Press.

Lee, J. (2005). Wage slaves [Electronic version]. 1UP.com. Retrieved July 27, 2006, from http://www.1up

.com/do/feature?cId=3141815

Mulligan, J., & Patrovsky, B. (2003). Developing online games: An insider’s guide. Indianapolis, IN: New

Riders Publishing.

Nakamura, L. (2000). Race in/for cyberspace: Identity tourism on the Internet. In D. Bell (Ed.), The

cybercultures reader (pp. 226-235). New York: Routledge.

Schubert, D. (2005, October). What Vegas can teach MMO designers (and how to take a design lesson

from almost anywhere). Speech presented at Austin Games Conference, Austin, TX.

Seay, A. F., Jerome, W. J., Lee, K. S., & Kraut, R. E. (2004). Project Massive: A study of online gaming

communities. In Proceedings of CHI 2004 (pp. 1421-1424). New York: ACM.

316 Games and Culture

Skinner, B. F. (1938). The behavior of organisms. Norwalk, CT: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Taylor, T. L. (2003). Power gamers just want to have fun? Instrumental play in a MMOG. In Proceedings

of the 1st Digra conference: Level Up (pp. 300-311). Utrecht, the Netherlands: University of Utrecht,

the Netherlands.

Taylor, T. L., & Jakobsson, M. (in press). The Sopranos meets EverQuest: Socialization processes in mas-

sively multiuser games. In E. Hayot & T. Wesp (Eds.), The EverQuest reader. London: Wallflower

Press.

Turkle, S. (1997). Life on the screen: Identity in the age of the Internet. New York: Touchstone Books.

Wikipedia. (2006). Gold farming [Electronic version]. Retrieved March 31, 2006, from http://en.wikipedia

.org/wiki/Gold_farming

Williams, D., Ducheneaut, N., Xiong, L., Zhang, Y., Yee, N., & Nickell, E. (2006). From tree house to

barracks: The social life of guilds in World of Warcraft. Games and Culture, 1 (4), 338-361.

Woodcock, B. (2005). An analysis of MMOG subscription growth—Version 18.0. Retrieved July 12,

2005, from http://pw1.netcom.com/~sirbruce/Subscriptions.html

Yee, N. (2001). The Norrathian Scrolls: A study of EverQuest (Version 2.5). Retrieved October 7, 2003,

from http://www.nickyee.com/eqt/report.html

Yee, N. (2005). The Daedalus Gateway. Retrieved August 17, 2005, from http://www.nickyee.com/daedalus

Yee, N. (2006). The demographics, motivations and derived experiences of users of massively-multiuser

online graphical environments. PRESENCE: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments, 15, 309-329.

Nicolas Ducheneaut is a research scientist in the Computing Science Laboratory at the Palo Alto

Research Center (PARC). His research interests include the sociology of online communities, computer-

supported cooperative work, and human-computer interaction. His research is based on a combination of

qualitative methods (ethnography) with quantitative data collection and analysis (i.e., data mining and

social network analysis).

Nick Yee is a PhD student in the Department of Communication at Stanford University. His research

focuses on social interaction and self-representation in immersive virtual reality and online games.

Eric Nickell is a researcher in PARC’s Computing Science Lab, probing how data harvested from multi-

player virtual worlds can help us understand their social nature.

Robert J. Moore is a sociologist in the Computing Science Laboratory at PARC. He specializes in the

microanalysis of social interaction and practice in virtual worlds and in real life. In the area of online

game research, he examines the mechanics of avatar-mediated interaction, virtual public spaces, and

player practice through screen-capture video analysis and virtual ethnography.

Ducheneaut et al. / Building an MMO With Appeal 317