Attitudes Toward Capital Punishment in America:

An Analysis of Survey Data

By

Tenzin Thinley

Faculty Advisor:

Dr. Andrew H. Ziegler, Jr.

Ninth Annual

Center for Research and Creativity

Symposium

Methodist University

Fayetteville, North Carolina

April 1, 2020

ii

Table of Contents

Abstract .......................................................................................................................................... iii

Introduction ......................................................................................................................................1

Literature Review.............................................................................................................................4

Methodology ..................................................................................................................................10

Findings and Analysis ....................................................................................................................20

Implications and Conclusion..........................................................................................................38

Bibliography ..................................................................................................................................41

Author’s Biography .......................................................................................................................44

iii

Abstract

This study used quantitative analysis of survey data to examine the factors that account

for differences in Americans’ attitudes towards capital punishment. A secondary analysis of the

2006 and 2008 General Social Survey was conducted.

The primary findings were that political factors, for example, party affiliation, opinions on

the courts, and confidence in government were much more significant than social and economic

factors. Republicans favor the death penalty more than Democrats, those who have a favorable

opinion towards courts are more willing to support the death penalty, and those who have high

confidence in the government are more willing to support the death penalty. The factors such as

education and religiosity did not have any effect on attitudes toward support for capital

punishment; however, Whites do support capital punishment more than African Americans.

Economic variables, such as income and opinion on the government’s crime spending do not

have that much influence towards support for capital punishment.

As politicians push their agendas, these findings may be useful in recognizing probable

support among voters for the specific issue regarding capital punishment. The common logic

from this research is that Republican executive and legislators will be affirming their support for

capital punishment more than the Democrats, because of the strong support of the Republican

voters toward capital punishment.

1

I. Introduction

According to the report published by Federal Bureau of Justice Statistics, there are

currently 2738 death row inmates in the United States criminal justice system with a total of 48

executions having been carried out between 2017 and 2018 (Office of Justice Programs 2019).

Some Americans believe that 48 executions are low, considering the number of inmates on death

row, with very few actually put to death. Other Americans believe that capital punishment

conflicts with their beliefs, and executing people is still murder and immoral. The topic of capital

punishment is always contentious in American politics. The debate regarding the federal and

state governments’ authority to take an individual's life raises political, constitutional, and

ethical, and financial issues.

From the establishment of the United States, the U.S. Constitution guaranteed both the

federal and states governments the right to set their own criminal penalties. The very first

Congress passed federal laws mandating death the penalty for crimes such as murder and heinous

sexual crimes. Additionally, each of the original states made several other crimes punishable by

death as well.

Politically, two issues surrounding the death penalty are: the weakness of the criminal

justice system that results in a person being wrongly accused of a capital crime, and the data

which show that lower class, colored and poor offenders are more likely to be sentenced to the

death penalty. Many believe that capital punishment is a part of an already flawed criminal

justice system.

Constitutionally, the firm establishment of capital punishment made the death penalty

legal. However, there is a clause in the Eighth Amendment of the Constitution, the phrase ‘cruel

and unusual punishment.’ The Constitution prohibits the government to employ any method that

2

is fundamentally cruel and unusual. Additionally, state constitutions individually include

stipulations that bar the employment of cruel and unusual punishment to its citizens. Historically,

those constitutional clauses were rarely enacted. Additionally, there were no debate or litigation

on this particular subject. This left a big dent on the constitutionality of the death penalty. The

main reason is that the Eighth Amendment requires society to consider the evolving standards of

decency to determine if a specific punishment constitutes as a cruel or unusual punishment. Can

the same standard of 18

th

century statutes that determined the death penalty does not violate the

clause of ‘cruel and unusual’ punishment be applied to the 21

st

century?

Ethical issues regarding death penalty arise when death penalty is viewed as both moral

and immoral. The establishment of the death penalty can be viewed by many as a practice that

society uses to accomplish the greatest equivalence of good over evil. They argue that the

practice of death penalty is moral because it brings deterrence. Deterrence in any case is good for

the society because once individuals know the consequences to such acts, they would hesitate to

commit such acts. On the other hand, society as a collective organization has a moral duty to

protect life. Taking into account that there is a priority of life in society, there exists a less severe

alternative (such as life sentence) that would accomplish the same goal of deterrence.

Financial issues that arise with the death penalty can be played by both sides of the

argument. The economic benefit argument cites that death penalty is a far less costly punishment

for the taxpayers than life imprisonment. On the other hand, financial burden argument cites that

death penalty costs are exorbitantly high. They cite the incarceration and legal costs. In a way,

the death penalty is both an economic burden and an advantage for the concerned public.

Attitudes about capital punishment are difficult to be explained on one such occasion.

The attitude and meaning of capital punishment swings as the political condition changes, the

3

world evolves, and the media alters people’s view of the world. People from all across the

spectrum have powerful feelings of opposite ends regarding death penalty, and this paper will

untie and take into account all those factors and practical foundations for the difference in

attitudes concerning capital punishment.

The research results and findings will be helpful to the policy makers, those working in

the criminal justice system, and the American community at large. They all deserve to know the

factors that give rise to the difference in attitude among Americans concerning the death penalty.

So, when stakeholders, the public, and policy makers make certain decisions regarding death

penalty, or even have a basic conversation about the death penalty; they have as much

information as possible.

This research attempts to make an in-depth analysis of the survey data presented by the

General Social Survey that encapsulates opinion data from the American public, and this

quantitative research paper will also employ empirical methods. This data will answer the

following research question: “What accounts for differences in attitudes among Americans

concerning capital punishment?”

To effectively answer the research question presented above, the paper will be divided

into various sections. First and foremost, the Literature Review will lay down the scope of the

research paper. It will present the limitation of the research paper, and it will justify the research

topic, design, and methodology. After the literature review, a methodology section will be

presented. This section will explain the data of the research and combine it with the formal

theory. Data Findings and Analysis will follow, and then to tie all the research findings up, a

conclusion will be drawn.

4

II. Literature Review

Introduction:

Scholars have argued over the years whether the death penalty should be continued. In

essence, the difference in attitude from the general public about the death penalty comes from

their different interpretation to three major dilemmas concerning the practice of capital

punishment. The first is a practical one: It calls into question the practicality of the death penalty.

The second is a moral dilemma: It calls into question the acceptability of the death penalty as an

ethical way to punish individuals. The third is a political one: It questions the collective society if

they can agree to execute people. Thus, debates over capital punishment have focused primarily

on its moral, practical, and political attributes as a government policy. This section will survey

the literature about the difference in attitudes toward capital punishment. Predictably, the survey

will be organized around two opposite schools of thought: those who favor the death penalty, and

those who do not.

The Death Penalty Should be Present in The Criminal Justice System:

The death penalty is an institution that has been ever present in the American history. The

first view of attitude towards the death penalty focusses that the practice of capital punishment

should be present and continued. The practice of the death penalty, according to some

researchers, should remain that way in the criminal justice system, because it is practical and

moral.

The death penalty is practical according to Gross and Ellsworth (1978), because in a

realistic world, when crimes go up, people look for harsher punishments to bring it down. Death

is ultimate, and people have strong sentiments regarding certain violent crimes that only the

death penalty can do justice to.

5

Rankin (1979) reiterates the same conclusion in his assessment and extrapolates that there

exists a strong positive non-linear relationship between the support for capital punishment and

violent crime. Crime, and specifically violent crime, harbors an emotion of anger in the public.

Anger is somehow connected to justice. It is practical to have an institution like the death penalty

that the public can have a legal channel to vent their utmost anger to the objects of anger

(criminal). After all, attitudes regarding the death penalty are not based on rational concerns at

all, but are primarily symbolic attitudes, based on emotions. Thus, death penalty is practical

because it serves the emotional purpose.

Paternoster (1991) examines a Gallup poll that examines the notion of retributivism in

American public and the death penalty. He comes across the same conclusion that the death

penalty is a practical practice because it serves an emotional purpose that no other method could

deliver. In his finding, he found out that many of the persons favor the death penalty because

they believe that those who have committed capital crime deserve to be executed.

The criminal justice system according to some scholars that favor the death penalty, rests

on the proposition that harder punishment are more deterrent than less severe punishment.

Dezhbaksh, Rubin, and Shepherd (2003) argue that the conventional intimidation of capital

punishment has accomplished its stated goal in deterring most coherent people from committing

a criminal act, and that the apprehension of the harsh punishment continues to deter all but those

who cannot be dissuaded by the imposition of any punishment. Their study concludes that capital

punishment has a strong deterrent effect; each capital punishment results, on average, in 18 fewer

murders approximately.

Furthermore, political scholars arguing in favor of the death penalty argue that the death

penalty is morally justifiable. Van Den Haag writes, “There is no other way for society to affirm

6

its moral values than the death penalty. To refuse to punish any capital crime with death, then is

to avow that the negative weight of a crime can never exceed the positive value of the life of the

person who committed it, which is implausible to many American” (1982, 332-333).

Banner (2002) extends the view of Van Den Haag and points that many people support

the death penalty because the death penalty is a moral requirement. The criminal law must

remind citizens of a moral mandate by which humans alone can live, and the only penalty that

can urge this reminder effectively is the death penalty.

Garland, McGowen, and Meranze (2011) argue that the abolition of the death penalty is a

largely undemocratic process. Recent research has shown that the abolition of the death penalty

is often implemented by the political and intellectual elites against the will of the public. Marquis

(2005) argues along the same way. He argues that the abolitionists are supported by wealthy

elites like George Soros and Roderick MacArthur. He writes, “The abolitionists were frustrated

by polling that showed that virtually all groups of Americans supported capital punishment in

some form in some cases” (2005, 501).

The Death Penalty Should be Abolished From The Criminal Justice System:

A second view towards capital punishment emphasizes that this practice should be

abolished. Scholars aligning to this view point out in their literature that the death penalty is

impractical and immoral. Some scholars have stressed the impracticality and characteristics of

the way criminal justice system is actually managed for misdeeds of severe offenses. The section

that follows in this review is intended to represent the arguments against the death penalty.

One of the most revered and influential opponents of the death penalty in the United

States, Alan M. Dershowitz, writes, “The death penalty deters your constitutional right to go to

trial. If people were ever to make a death penalty work efficiently, it would be at the cost of

7

justice” (1989, 330-335). The practice of death penalty makes the criminal justice system lose

credibility as an institution that delivers justice.

Many succeeding studies have modified or extended the claim by Dershowitz (1989).

Works by Bohm (1999) suggests that lapses of justice in capital cases, including erroneous

executions do transpire, and they happen with some regularity and frequency. Regardless of the

judicial determinations to limit convictions of innocent in the first place, they are unavoidable.

The death penalty, to put in simple words, is purely final and irreversible. Ultimately, it leaves no

room for human error, and prohibits the undoing of mistakes by the criminal justice system. Kyle

and Pollitt (1999) state that the concern of innocence has had an overwhelming influence in the

death penalty debate. It swings the debate in favor of eradicating the practice of the death

penalty. The main reason is that the repeated failure in determining the guilt of those on death

row has sharply eroded the public’s confidence in the death penalty.

Stephen B. Bright (1995) is equally invested in the topic concerning the impracticality of

the death penalty, but he focuses on the vulnerability of offenders of color in getting the death

penalty. He argues that racial bias has an increasing effect on who ends up on death row. Overall,

there exists a surprisingly homogenous pattern of racial disparities in death sentencing

throughout the United States.

Bohm (1999) extended this study and points out in his research that poor capital

offenders are also more susceptible towards death penalty than regular capital offenders. In such

scenario, the death penalty is not levied in a proper way. Those on the receiving end of such

punishment are almost always those who are vulnerable because of their income, race, and

minority status.

8

Furthermore, it is also questionable whether or not the practice of capital punishment

deters crime, as it is so often argued. Dieter’s (2007) research with different methodologies and

statistical approaches regarding capital punishment suggests that the death penalty is not a

superior deterrent. As a substitute, life imprisonment without the opportunity of parole seems to

offer as much deterrence or public safety as capital punishment.

Kronenwetter further suggests that “If deterrence is at the heart of the practical debate

over the death penalty, the sanctity of human life should overweigh the practicality” (1993, 22).

Overall, scholars that argue against the death penalty points out that there is no credible

empirical evidence that proves that the death penalty deters crime.

Scholars argue that the death penalty is impractical because it is a financial burden. Bohm

(1999) asserts that while there is a consensus among the public that the death penalty is a less

expensive punishment than life imprisonment, it is not the case for a majority of occasions. It is

relatively uncomplicated to consider the costs of life imprisonment (the costs of everyday needs).

This cost appears deceptively to be higher than trying someone for the death penalty. The main

reason that this cost analysis is deceptive is that it is true only when the death penalty is carried

out quickly. The fundamental thing to know here is that capital cases are complex and take a

long time. Gradess and Davies (2009) conclude that for the past 25 years, in practically all of the

states studied persistently show that the death penalty costs more than life in prison.

Additionally, scholars have argued against the death penalty because it is immoral.

Kronenwetter (1993) and Kyle and Pollitt (1999) point out that when the government rationally

puts a convicted capital offender to death the government is simply committing an additional

murder. On moral basis, both acts, it is contested, involve the premeditation and cold blooded

9

killing of an individual. As a collective society that places so much value in the sanctity of

human life, government is immoral in continuing to execute people.

Scholars further argue that the death penalty should be abolished because it is

unconstitutional. Goldberg and Dershowitz write, “The death penalty is now unconstitutional

under the principles of the Eighth Amendment adumbrated by the Supreme Court” (1970, 1818).

Conclusion:

In order to facilitate the research on the difference of attitudes among the public

regarding the death penalty, two schools of thought have been explained. Those scholars that

favor the death penalty argue that the death penalty is moral, and serves a practical purpose. On

the other hand, scholars who argue the death penalty should be abolished deem the death penalty

as immoral and impractical.

The methodology will be drawn in the next section. It will identify the different variables

associated with this literature. Then, the methodology section will primarily explore the

correlation between those variables.

10

III. Methodology

The scholars have cited various reasons about the difference in attitudes toward capital

punishment. This section of the paper will operationalize the research topic and use selected

variables to define the cause and effects. The literature review has specified two schools of

thought regarding the difference in attitudes toward capital punishment: those who favor the

death penalty, and those who oppose it. The literature has assisted in pinpointing the important

variables that can be used when analyzing the research topic. In examining the research question

of “What accounts for differences in attitudes among Americans concerning capital

punishment?” the variables will be further classified into two groups, independent and dependent

variables. This methodology section will ultimately hypothesize the correlation between them.

The independent variables that are expected to reflect the favorability of capital

punishment can be classified into three sets of variables: political, social, and economical. The

political independent variables associated with this study are party affiliation, court’s judicial

performance, trust in government. Social independent variables such as education level, race,

religion, and racial disparities will operationalize the social difference in Americans opinion

regarding the death penalty. On that same note, economical independent variables such as

income level and view on government spending will operationalize the economical difference in

Americans opinions regarding the death penalty. In order to retrieve data for this research paper,

the General Social Survey (GSS) 2008 and 2006 file from Micro Case software (LeRoy 2013)

will be used.

A. Concepts and Variables

In the GSS 2008 file, variable 106) EXECUTE? will be the dependent variable, and in

the GSS 2006 file, variable 107) EXECUTE? will be the dependent variable. Those two identical

11

dependent variables will operationalize the concept of difference in attitudes among Americans

regarding capital punishment. The sample from which this variable derived from, the General

Social Survey (2008) and (2006), consist of a cross-section of respondents that yielded 3559 and

4510 cases respectively. 106) EXECUTE? and 107)EXECUTE? is designed as a survey question

for the respondent as “Do you favor or oppose the death penalty for persons convicted of

murder?” This variable is an ordinal data that has a range for its result as 0 and 1; with 0

representing those who oppose the death penalty, and 1 representing those who favor the death

penalty for persons convicted of murder.

The following paragraph will operationalize the independent variables mentioned earlier

into variables from the GSS file, and conceptually define them. An account of each independent

variable will also be integrated to show the importance of why they were selected for this

research.

Political Variables

1. 56) PARTY-This is an ordinal variable from GSS (2008) which questions the

respondents of their party identification: “Generally speaking, do you usually think of

yourself as a Republican, Democrat, Independent, or what?” The range of the result is 1

to 3; with 1 representing those who identify as democrats, 2 for those who identify as

independents, and 3 representing those who identify as republicans. This variable

measures political concept of party affiliation and tries to understand the stance of

respondents on major political concerns.

2. 108) COURTS?- This is an ordinal variable from GSS (2008) which questions the

respondents of the court’s judicial performance: “In general, do you think the courts in

this area deal too harshly about right, or not harshly enough with criminals?” The range

12

of the result is 1 to 3; with 1 representing those who think the courts in the area deal to

harshly with criminals, 2 for those who think the courts in the area deal about right with

criminals, and 3 representing those who think the courts in the area deal not harshly

enough with criminals. This variable measures the concept of judicial performance,

which indicates the citizens’ opinion on capital punishment sentencing.

3. 146) FED GOV’T?-This is an ordinal variable from GSS (2006) which questions the

respondents of their confidence in the executive branch of the government: “Confidence?

Executive branch of the federal government” The range of the variable is 1 to 3; with 1

representing those who have great deal of confidence in the executive branch of the

federal government, 2 representing those who have only some confidence in the

executive branch of the government and 3 representing those who have hardly any

confidence in the executive branch of the federal government. This variable measures the

concept of trust in the executive government.

Social Variables:

4. 28) EDUCATION-This is an ordinal variable from GSS (2008) which questions the

respondents of their education level: “What is your education level?” The range of the

result is 1 to 3; 1 representing those with no high school degree, 2 representing those with

a high school degree, and 3 representing those with some college education. This variable

measures the concept of education.

5. 32) RACE-This variable has a nominal level of measurement from GSS (2008) that

denotes the race of the respondent by asking the question “Respondent’s Race” The range

of the result is 1 to 3; with 1 representing those who are white, 2 representing those who

13

are black, and 3 representing those who are of other race. This variable measures the

concept of race.

6. 262) RELPERSN-This is an ordinal variable from GSS (2006) that categorizes the

respondent’s religiosity by asking the question “To what extent do you consider yourself

a religious person?” The range for this ordinal variable is 1 to 3; 1 representing those who

consider themselves very religious, 2 representing those who consider themselves

somewhat religious, and 3 representing those who consider themselves not at all

religious. This variable measures the concept of religion.

7. 228) RACE DIF1-This is an nominal variable from GSS (2006) that questions the

respondents on the prevalence of racial discrimination: “On the average (Blacks) have

worse jobs, income, and housing than white people. Do you think these differences

are...A. Mainly due to discrimination?” The range of the results is 1 to 2; with 1

representing those who answered yes, the differences are mainly due to discrimination,

and 2 representing those who answered no, the difference not mainly due to

discrimination. This variable measures the concept of racial disparity.

Economic Variables:

8. 68) CRIME $-This variable has an ordinal level of measurement from GSS (2006) that

questions the respondents of their opinion on government’s spending on crime:

“Spending on halting the rising crime rate” The range of the results is 1 to 3; with 1

representing those who think too little is being spent on halting the rising crime rate, 2

representing those who think right amount is being spent on halting the rising crime rate,

and 3 representing those who think too much is being spent on halting the rising crime

rate. This variable measures the concept of government spending.

14

9. 56) INCOME- This is an ordinal variable from GSS (2006) that categorizes the

respondents based on their income: “Respondent’s family income range” The range of

the result is 1 to 3; with 1 representing those who fall under low income status, 2

representing those who fall under middle income status, and 3 representing those who fall

under high income status. This variable measures the concept of income.

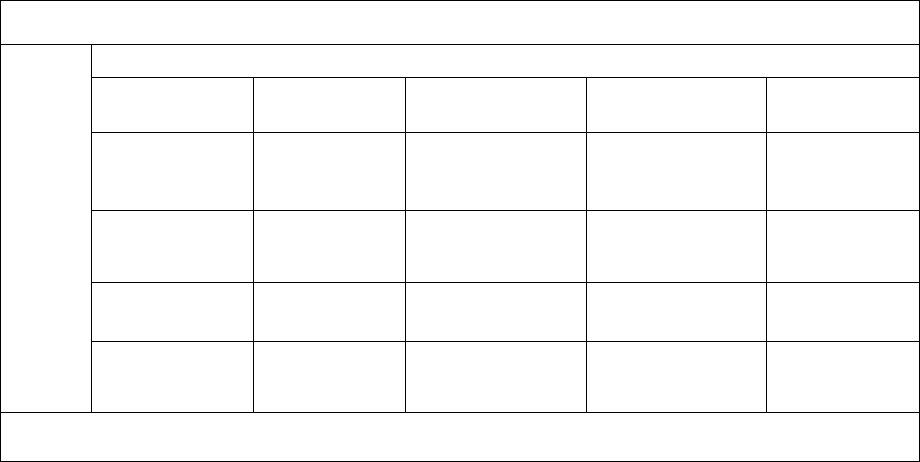

Figure 1 represents all the independent variables to be tested against the corresponding

dependent variable.

B. Hypotheses

Political Variables:

Hypothesis 1: Republicans have greater support for capital punishment than Democrats.

Figure 1:

Independent Variables

Dependent Variable

15

Citizens who have a strong political identification are more likely to be aware of the

issues at hand. Those who identify as Republicans are hypothesized to halt any criminal

justice reform that includes stopping the practice of capital punishment.

Hypothesis 2: Those who think courts in the area deal too harshly with criminals are less

likely to support capital punishment than those who think courts in this area are lenient with

criminals.

Robert Bohm (1999) points out in his study that lapses of justice in capital cases,

including erroneous executions do occur, and they happen with regularity and frequency.

People acclimatized to knowledge of this type, and people with negative view of the justice

system think that the courts in this area deal to harsh with criminals, and they will be less

likely to support capital punishment.

Hypothesis 3: People with great deal of confidence in the federal government have greater

support for capital punishment than do people with hardly any trust in the federal

government.

Respondent’s confidence in the government are some good indicators of their opinion on

government’s execution of its policy. Since, capital punishment is one of the government’s

policy to curb violent criminal activity, those with great deal of confidence in the federal

government are hypothesized to have greater support for capital punishment.

Social Variables:

Hypothesis 4: Those with higher education are more likely to oppose the death penalty

Scholars have examined and deduced that attitudes regarding the death penalty are not

based on rational concerns, but primarily emotions (Rankin 1979). More education can

16

always reinforce the rational concerns in a more poignant way and change the perspective of

people. Thus, people who attain higher education are more likely to oppose the death penalty.

Hypothesis 5: Whites have greater support for capital punishment than African Americans.

Cultural differences are more likely to be present in people with different races. With

African Americans perceived as more susceptible to capital sentencing (Bright 1995),

African Americans more likely to oppose the death penalty than the White Americans.

Hypothesis 6: Those who consider themselves very religious are more likely to support

capital punishment.

Old system and traditional value are more likely to be prevalent in religious person. The

social norms of many people are that the death penalty is a moral requirement (Banner 2002).

It deems the death penalty as an enforcer of a moral mandate that people can live by. Those

attitudes are more likely to be seen in a religious person. Thus, people who consider

themselves very religious are more likely to support capital punishment than are people who

don’t consider themselves religious at all.

Hypothesis 7: Those who think racial disparities exist are more likely to oppose the death

penalty than those who think racial disparities do not exist.

Scholars like Stephen B. Bright (1995) have concluded that there exists a surprisingly

homogenous pattern of racial disparities in death sentencing throughout the United States.

With such discovery, this paper will hypothesized that those who think racial disparities

exists are more likely to oppose the death penalty.

17

Economic Variables

Hypothesis 8: Those who oppose more spending on halting the crime rate are more likely to

oppose the death penalty than those who think too little is being spend on halting the crime

rate.

The economic argument cited by scholars have concluded that the death penalty is more

costly than life in prison (Gradess and Davies 2009). This argument may enforce people who

oppose more spending on halting the crime rate to oppose the death penalty to save costs.

Hypothesis 9: Those with a higher income are more likely to support capital punishment.

Cultural differences among the rich and the poor are widening. Scholars such as Bohm

(1999), in his research, found out that those on the receiving end of capital punishment are

almost always those who are vulnerable because of their income. This research facilitates that

those with a lower income are more likely to oppose capital punishment than those with a

higher income.

C. Research Method

This research will be based on the secondary analysis facilitated by GSS 2006 and GSS

2008 file from the MicroCase software. The GSS 2006 and 2008 is based upon surveys that

were done on 4510 and 3559 individuals in the United States that includes questions covering

national spending opinions, recreational drug use, crime and punishment, race relation,

quality of life, and confidence in institutions. The GSS 2006 file includes 888 variables, and

the GSS 2008 file includes 355 variables, amongst which this research paper has singled out

10 to be used for examination. This research paper will be empirical, and employ quantitative

data to answer the research question. The results produced in this research will be analyzed

18

using guidelines outlined in Research Methods in Political Science: An Introduction Using

MicroCase, 8

th

Edition (LeRoy 2013).

The research paper will employ cross tabulations to determine if a relationship between

independent and dependent variable exists or not. The presentation technique will be in the

form of a contingency table. There will be category labels in the contingency table, where the

labels for the categories of the independent variable will be drawn across the top of the table

(column), and the labels for the categories of the dependent variable will be drawn on the left

side of the table (row).

In the analysis, a test of statistical significance will be established. This will determine

the probability that an observed effect would have occurred due to sampling error alone. As

such, the cut-off point for test of statistical significance in this research would be 0.05. The

measure would be denoted as “prob.” In a given case, where the relationship has prob

exceeding the value of 0.05, the relationship will be deemed insignificant.

This relationship will also employ measures of association to determine the strength of

the relationship between the independent and the dependent variable. This research will use

two measures of association: Gamma for analysis that includes two ordinal variables, and

Cramer’s V for analysis that include nominal level of measurement. The probable range of

Cramer’s V and Gamma are same; in which 1.0 indicates a perfect relationship between the

two variables, and 0 indicating no relationship. For numbers ranging between 0 and 1, The

following parameter will be employed to interpret the strength of the measures of association

related to Cramer’s V or Gamma that is in use:

In a relationship, where the value of absolute value of Cramer’s V or Gamma is

under 0.1, the relationship is very weak.

19

In a relationship, where the value of absolute value of Cramer’s V or Gamma is

under 0.19 but above 0.10, the relationship is weak.

In a relationship, where the value of absolute value of Cramer’s V or Gamma is

under 0.20 but above 0.29, the relationship is moderate.

In a relationship, where the value of absolute value of Cramer’s V or Gamma is

above 0.30, the relationship is strong. (LeRoy 2013, 196).

The next section, Findings and Analysis, will survey and explain the preceding

research method.

20

IV. Findings and Analysis

This section of the paper will test and analyze the hypotheses, which were outlined in the

previous section. The hypotheses will be examined with the help of MicroCase software, and the

data from the findings will be explained according to whether it supports the assumptions. The

dependent variable used in this paper will be variable 107) EXECUTE? (GSS 2006) and 106)

EXECUTE? (GSS 2008). It asks respondents: “Do you favor or oppose the death penalty for

persons convicted of murder?” it has two categories for answer; “Oppose” and “Favor.”

“Oppose” category comprises of respondents who oppose capital punishment. Whereas,

“Support” category comprises of respondents who support capital punishment. This is done to

reflect the concept of capital punishment in a clear manner. The dependent variable will then be

tested against independent variables: political affiliation, opinion on courts, confidence in

government, education, race, religiosity, racial disparity, opinion on crime spending, and income.

Each concept has been operationalized as a variable in the previous section, and has been

categorized into three wide categories: political, social, and economical. The data from the cross

tabulation will also be displayed using contingency tables- Table 1 to 9.

An account will be given for using crosstabulations as the presentation technique,

Gamma, and Cramer’s V for measures of association. Based on the data, hypotheses will be

regarded as supported or not supported. These findings will support in answering the research

question of “What accounts for difference in attitude among Americans concerning capital

punishment?”

21

Political Variables

A. Support for Capital Punishment by Party Affiliation

The first hypothesis states that those who are affiliated to Republicans have greater

support for capital punishment than Democrats. This hypothesis is operationalized using the

variable 56) PARTY as an independent variable which poses the question “Generally speaking,

do you usually think of yourself as a Republican, Democrat, Independent, or what? 1) Democrat;

2) Independent; 3) Republican.” This independent variable will be tested against 106)

EXECUTE? as a dependent variable that indicates support toward capital punishment. The two

variables are sourced from the General Social Survey (GSS) 2008.

Table 1 displays the results of the cross tabulation between Support for Capital

Punishment and Party Affiliation. There are three categories listed across the top of the

contingency table, which characterizes the independent variable: respondent’s party affiliation.

The categories are displayed into “Democrat” which represents those who identify as a

Democrat, “Independent” for those who identify as an Independent, and “Republican” for those

who identify as a Republican.

On the left hand side of the table, there are two categories listed which characterizes the

dependent variable: support for capital punishment. Variable 106) EXECUTE? has been drawn

into two categories; “Oppose” and “Favor.” The “Oppose” category comprises of respondents

who answered that they oppose the practice of capital punishment. The “Favor” category

comprises of respondents who answered that they favor the practice of capital punishment.

In doing the cross tabulation, the results produced a statistical significance of prob=0.00.

This value implies that there is 0 chance out of 100 that the relationship does not exist in the

population from which the sample was selected. This figure suggests that the relationship is

22

statistically significant. Since, both the variables are ordinal, Gamma will be employed as the

measure of association to test the strength of the relationship. The Gamma for the association is

0.453, which tells us that the two variables have a strong relationship with each other.

Table 1: Support for Capital Punishment by Party Affiliation

Support for Capital

Punishment

Political Parties

Democrat

Independent

Republican

Missing

Total

Oppose

43.7%

(709)

32.3%

(156)

17.8%

(210)

25

32.7%

1075

Favor

56.3%

(913)

67.7%

(327)

82.2%

(971)

50

67.3%

(2211)

Missing

86

55

48

8

197

Total

100.0%

(1622)

100.0%

(482)

100.0%

(1182)

84

3286

P=0.00 Gamma=0.453

In reference to the distribution of data within Table 1, it is observable that 82.2% of

respondents who identified as a Republican support capital punishment, while only 56.3% of

respondents who identifies as a Democrat support capital punishment. It is evident that there is a

significant pattern to exemplify a contrast from those who identified as a Democrat and

Republican. The data to this cross tabulation clearly supports the hypothesis that Republicans

have greater support for capital punishment than Democrats.

A possible explanation for this finding is that Republicans have clearly stated in their

election manifesto that they will be tough on crime. Tough on crime signifies harsh sentence for

crimes. Thus, those who identified as Republicans, have greater support for capital punishment

than Democrats. This assumption is clearly reflected in the findings of the data.

B. Support for Capital Punishment by Opinion on Courts

23

The second hypothesis states that those who think courts in the area deal too harshly with

criminals are less likely to support capital punishment than those who think courts in this area are

lenient with criminals. This hypothesis is operationalized using the variable 108)COURTS? as

an independent variable which poses the question “In general, do you think the courts in this area

deal too harshly about right, or not harshly enough with criminals? 1) Too Harsh; 2) Right; 3)

Not Enough.” This independent variable will be tested against 106) EXECUTE? as a dependent

variable that indicates support toward capital punishment. The two variables are sourced from

the General Social Survey (GSS) 2008.

Table 2 displays the results of the cross tabulation between Support for Capital

Punishment and Opinion on Courts. There are three categories listed across the top of the

contingency table, which characterizes the independent variable: respondent’s opinion on court’s

handling of criminals. The categories are displayed into “Too Harsh” which represents those who

think courts in the area deals too harsh with criminals, “Right” for those who think courts in the

area deals right with criminals, and “Not Enough” for those who think courts in the area are

lenient with criminals. The left side is the same.

In doing the cross tabulation, the results produced a statistical significance of prob=0.001.

This value implies that there is 1 chance out of 1000 that the relationship does not exist in the

population from which the sample was selected. This figure suggests that the relationship is

statistically significant. Since, both the variables are ordinal, Gamma will be employed as the

measure of association to test the strength of the relationship. The Gamma for the association is

0.129, which tells us that the two variables has a weak relationship with each other.

24

Table 2: Support for Capital Punishment by Opinion on Courts

Support for Capital Punishment

Opinion on Courts Handling of Criminal Cases

Harsh

Right

Not Enough

Missing

Total

Oppose

56.8%

(227)

24.9%

(527)

37.4%

(238)

108

31.5%

(993)

Favor

43.2%

(173)

75.1%

(1590)

62.6%

(397)

101

68.5%

(2160)

Missing

12

112

41

32

197

Total

100.0%

(400)

100.0%

(2117)

100.0%

(635)

241

3153

P=0.001 Gamma= 0.129

Looking into the content of Table 2, it is notable that 56.8% of the respondents who think

courts in the area deal too harshly with criminals oppose capital punishment, while only 37.4%

of those who think courts are not harsh enough with criminals oppose capital punishment.

Clearly, this finding signifies the acceptance of the hypothesis that those who think courts in the

area deals too harsh with criminals are more likely to oppose capital punishment.

This discovery can be attributed to the factor that people who constantly question the

court regarding criminal issue are less likely to believe in the sentencing. We can hypothesize to

see a pattern that people that do not believe in the system itself will not likely support capital

punishment.

The anomaly to analyze here is the “Right” Category which signifies those who think

courts in this area deal about right with criminals. The noticeable number is that they least

oppose the death penalty, and they favor capital punishment more than the other two category.

This can be attributed to the factor that the “Right” category are content with the already

established system of capital punishment. It presents an interesting factor that this paper has not

taken into account that people acclimatized and comfortable with a system will be in favor of

25

established system like capital punishment. This could certainly be the reason for a weak Gamma

in this relationship.

C. Support for Capital Punishment by Confidence in Government

The third hypothesis states that people with great deal of confidence in the federal

government have greater support for capital punishment than do people with hardly any trust in

the federal government. This hypothesis is operationalized using the variable 146) FED GOV’T?

as an independent variable which poses the question “Confidence? Executive branch of the

federal government: 1) Great Deal; 2) Only Some; 3) Hardly Any.” This independent variable

will be tested against 107) EXECUTE? as a dependent variable that indicates support toward

capital punishment. The two variables are sourced from the General Social Survey (GSS) 2006.

Table 3 displays the results of the cross tabulation between Support for Capital

Punishment and Confidence in Government. There are three categories listed across the top of

the contingency table, which characterizes the independent variable: respondent’s confidence in

the federal government. The categories are displayed into “Great Deal” which represents those

who have high confidence in the federal government, “Only Some” for those who have only

some confidence in the federal government, and “Hardly Any” for those who have hardly any

confidence in the federal government. The left side is the same.

In doing the cross tabulation, the results produced a statistical significance of prob=0.00.

This value implies that there is 0 chance out of 100 that the relationship does not exist in the

population from which the sample was selected. This figure suggests that the relationship is

statistically significant. Since, both the variables are ordinal, Gamma will be employed as the

measure of association to test the strength of the relationship. The Gamma for the association is –

0.2, which tells us that the two variables has a moderate relationship with each other.

26

Table 3: Support for Capital Punishment by Confidence in Government

Support for Capital

Punishment

Confidence in Federal Government

Great Deal

Only Some

Hardly Any

Missing

Total

Oppose

25.1%

(75)

29.0%

(248)

37.8%

(267)

280

31.8%

(590)

Favor

74.9%

(223)

71.0%

(605)

62.2%

(440)

677

68.2%

(1268)

Missing

16

46

38

1596

1696

Total

100.0%

(297)

100.0%

(853)

100.0%

(707)

2553

1857

P=0.00 Gamma= 0.2

It is also evident within the distribution of data, the results of the cross tabulation

between confidence in government and capital punishment, supports the hypothesis. For

respondents who say that they have great deal of confidence in the government, 74.9% of them

express support for capital punishment. However, only 62.2% of the respondents who has hardly

any trust in the government support capital punishment. This finding therefore backs the

hypothesis that those with great deal of confidence in the federal government have greater

support for capital punishment than people with hardly any trust in the government.

Greater support for governmental action would lead to more confidence in the

government. As such, if people support governmental action like their capital punishment

sentencing policy and execution, and see the logic behind it, they are more likely to support

capital punishment. This is clearly portrayed by the data in the table.

Social Variables

D. Support for Capital Punishment by Education

The fourth hypothesis states that those with higher education are more likely to oppose

the death penalty. This hypothesis is operationalized using the variable 28) EDUCATION as an

independent variable which poses the question “What is your education level? 1) No High

27

School Degree; 2) High School Degree; 3) College Education.” This independent variable will

be tested against 106) EXECUTE? as a dependent variable that indicates support toward capital

punishment. The two variables are sourced from the General Social Survey (GSS) 2008.

Table 4 displays the results of the cross tabulation between Support for Capital

Punishment and Education Level. There are three categories listed across the top of the

contingency table, which characterizes the independent variable: respondent’s level of education.

The categories are displayed into “No High School Degree” which represents those who have not

graduated from high school, “High School Degree” which represent those who have graduated

from high school, and “College Degree” for those who have college education. The left side is

the same.

In doing the cross tabulation, the results produced a statistical significance of prob=0.476.

This value implies that there is approximately 47 chance out of 100 that the relationship does not

exist in the population from which the sample was selected. This figure suggests that the

relationship is not statistically significant. Since, both the variables are ordinal, Gamma will be

employed as the measure of association to test the strength of the relationship. The Gamma for

the association is 0.024, which tells us that the two variables has too weak relationship with each

other.

Although, the relationship is too weak to consider, and statistically insignificant, we will

still analyze the table accordingly. Examining the table, it is observable that only 34.4% of

respondents who are college educated oppose capital punishment, while 39.8 % of respondents

who are not high school graduated oppose capital punishment, and 24.8% of respondents who

are high school graduate oppose capital punishment. Clearly, this signifies the rejection of the

hypothesis that those with higher education are more likely to oppose capital punishment. On the

28

other side, the opposite hypothesis that those with higher education are more likely to support

capital punishment is also rejected by this finding. It signifies that there is no relationship

between education and capital punishment.

The discovery can be attributed to the analysis of Rankin (1979) that attitudes regarding

the death penalty are not based on rational concerns at all, but are primarily symbolic attitudes,

based on emotions. It clearly supports the fact that there is no real relationship between support

for capital punishment and education.

E. Support for Capital Punishment by Race

The fifth hypothesis proposes that Whites have greater support for capital punishment

than African Americans. In operationalizing the concept of race, variable 32) RACE will be

used. This independent variable is question posed to respondents of their race. In conducting the

cross tabulation for this hypothesis, the independent variable will be tested against 106)

EXECUTE? which operationalizes support for capital punishment. The two variables are sourced

from the General Social Survey (GSS) 2008.

Table 4: Support for Capital Punishment by Education

Support for Capital

Punishment

Level of Education

No High

School Degree

High School

Degree

College

Graduate

Missing

Total

Oppose

39.8%

(219)

24.8%

(223)

34.4%

(657)

2

32.7%

(1098)

Favor

60.2%

(331)

75.2%

(676)

65.6%

(1253)

2

67.3%

(2259)

Missing

35

48

112

2

197

Total

100.0%

(549)

100.0%

(898)

100.0%

(1910)

7

3357

P=0.476 Gamma= 0.024

29

Within Table 5, there are three categories listed across the top of the contingency

table representing the independent variable. The categories are “White,” “Black,” and “Others.”

The left side is the same.

In doing the cross tabulation, the results produced a statistical significance of prob=0.00.

This value implies that there is approximately 0 chance out of 100 that the relationship does not

exist in the population from which the sample was selected. This figure suggests that the

relationship is statistically significant. Since, the independent variable is nominal, while the

dependent variable is ordinal, Cramer’s V will be employed as the measure of association to test

the strength of the relationship. The Cramer’s V for the association is 0.202, which tells us that

the two variables has moderate relationship with each other.

Table 5: Support for Capital Punishment by Race

Support for Capital Punishmen

t

Race

White

Black

Other

Total

Oppose

27.8%

(725)

53.5%

(230)

45.4%

(146)

32.7%

(1100)

Favor

72.2%

(1885)

46.5%

(200)

54.6%

(176)

67.3%

(2261)

Missing

141

29

27

197

Total

100.0%

(2610)

100.0%

(429)

100.0%

(322)

3362

P=0.00 Cramer’s V= 0.202

It is also evident that within the distribution of data, the results of the cross tabulation

between race and support for capital punishment, supports the hypothesis. For respondents who

are white, 72.2% of them express support for capital punishment. However, a lower percentage

of them (46.5%) express support for capital punishment. This finding, therefore, backs up the

hypothesis that Whites have greater support for capital punishment than African Americans.

30

Race has been a strong influence in the criminal justice system especially capital

sentencing. Scholars are Bright (1995) has found in his study that racial bias has an increasing

effect on who ends up on death row. This has been going on for a long time, and African

Americans do have that presumption backed with facts cemented on them, that can be the factor

in African Americans expressing less support for capital punishment than White Americans.

F. Support for Capital Punishment by Religiosity

The sixth hypothesis states that those who consider themselves very religious are more

likely to support capital punishment. This hypothesis is operationalized using the variable 262)

REL PERSN as an independent variable which poses the question “To what extent do you

consider yourself a religious person? 1) Very Religious; 2) Somewhat Religious; 3) Not at all

Religious.” This independent variable will be tested against 107) EXECUTE? as a dependent

variable that indicates support toward capital punishment. The two variables are sourced from

the General Social Survey (GSS) 2006.

Table 6 displays the results of the cross tabulation between Support for Capital

Punishment and Religiosity. There are three categories listed across the top of the contingency

table, which characterizes the independent variable: respondent’s religiosity. The categories are

displayed into “Very Religious” representing those who consider themselves very religious,

“Somewhat Religious” representing those who consider themselves somewhat religious, and

“Not at all Religious” representing those who consider themselves not at all religious. The left

side is the same.

31

Table 6: Support for Capital Punishment by Religiosity

Support for Capital

Punishment

Level of Religiosity

Very

Religious

Somewhat

Religious

Not at All

Religious

Missing

Total

Oppose

35.2%

(183)

29.0%

(543)

33.9%

(138)

6

30.9%

(864)

Favor

64.8%

(338)

71.0%

(1325)

66.1%

(269)

12

69.1%

(1932)

Missing

44

119

14

1518

1696

Total

100.0%

(521)

100.0%

(1868)

100.0%

(407)

1537

2796

P=0.445 Gamma= 0.030

In doing the cross tabulation, the results produced a statistical significance of prob=0.445.

This value implies that there is approximately 44 chance out of 100 that the relationship does not

exist in the population from which the sample was selected. This figure suggests that the

relationship is not statistically significant. Since, both the variables are ordinal, Gamma will be

employed as the measure of association to test the strength of the relationship. The Gamma for

the association is 0.030, which tells us that the two variables has a very weak relationship with

each other.

Although, the relationship is too weak to consider, and statistically insignificant, we will

still analyze the table accordingly. It is also observable that within the distribution of data, the

results of the cross tabulation between religiosity and support for capital punishment, rejects the

hypothesis.

For respondents who identify as very religious, 64.8% of them express support for capital

punishment, while respondents who identify as somewhat religious 71.0 % express support for

capital punishment, and respondents who identify as non-religious 66.1 % express support for

32

capital punishment. This finding rejects the hypothesis and makes it clear there is no relationship

between support for capital punishment and religiosity.

The basis to draw this hypothesis was that the main argument for the death penalty was

that capital punishment is a moral requirement. Therefore, it can be presumed that morality and

religiosity can be linked together. Thus people who consider themselves religious would support

capital punishment more than non-religious person. This finding contradicts this presumption.

Thus, morality and religiosity is not linked in this research.

G. Support for Capital Punishment by Racial Disparity

The seventh hypothesis proposes that those who think racial disparities exist are more

likely to oppose the death penalty than those who think racial disparities do not exist. In

operationalizing the concept of racial disparity, variable 228) RACE DIF1 will be used. This

independent variable is question posed to respondents of their opinion on the existence of racial

disparities. In conducting the cross tabulation for this hypothesis, the independent variable will

be tested against 107) EXECUTE? which operationalizes support for capital punishment. The

two variables are sourced from the General Social Survey (GSS) 2006.

Within Table 7, there are three categories listed across the top of the contingency table

representing the independent variable. The categories are “YES,” for those who think racial

disparities exist and “NO”, for those who think racial disparities does not exist at all. On the left

hand side of the table, there is no change.

In doing the cross tabulation, the results produced a statistical significance of prob=0.00.

This value implies that there is approximately 0 chance out of 100 that the relationship does not

exist in the population from which the sample was selected. This figure suggests that the

relationship is statistically significant. Since, the independent variable is nominal, while the

33

dependent variable is ordinal, Cramer’s V will be employed as the measure of association to test

the strength of the relationship. The Cramer’s V for the association is 0.210, which tells us that

the two variables has moderate relationship with each other.

It is also evident that within the distribution of data, the results of the cross tabulation

between race and support for capital punishment, supports the hypothesis. For respondents who

think racial disparities still exist, 43.5% of them oppose capital punishment. However, a lower

percentage of them who think racial disparities does not exist (23.1%) oppose the practice of

capital punishment. This finding, therefore, backs up the hypothesis that those who think racial

disparities exist are more likely to oppose the death penalty than those who think racial

disparities do not exist.

Table 7: Support for Capital Punishment by Racial Disparity

Support for Capital

Punishment

Existence of Racial Disparity in America

Yes

No

Missing

Total

Oppose

43.5%

(263)

23.1%

(270)

336

30.1%

(534)

Favor

56.5%

(342)

76.9%

(899)

703

69.9%

(1241)

Missing

51

72

1573

1696

Total

100.0%

(606)

100.0%

(1170)

2612

1775

P=0.00 Cramer’s V= 0.210

It is also evident that within the distribution of data, the results of the cross tabulation

between race and support for capital punishment, supports the hypothesis. For respondents who

think racial disparities still exist, 43.5% of them oppose capital punishment. However, a lower

percentage of them who think racial disparities does not exist (23.1%) oppose the practice of

capital punishment. This finding, therefore, backs up the hypothesis that those who think racial

34

disparities exist are more likely to oppose the death penalty than those who think racial

disparities do not exist.

This is similar to the independent variable of race, but this dives deeper into people who

think that racial disparities still exist. Scholars like Bohm (1999) and Bright (1995) have

concluded in their study that there exists a surprisingly homogenous pattern of racial disparities

in death sentencing throughout the United States. When individuals get to know such facts and

consider their support for capital punishment, they will be more likely to oppose capital

punishment. Hence, those who think racial disparities exist are more likely to oppose the death

penalty than those who think racial disparities does not exist.

Economic Variables

H. Support for Capital Punishment by Crime Spending Opinion

The eighth hypothesis states that those who oppose more spending on halting the crime

rate are more likely to oppose the death penalty than those who think too little is being spend on

halting the crime rate. This hypothesis is operationalized using the variable 68) CRIME$ as an

independent variable which poses the question “Spending on halting the rising crime rate: 1) Too

Little; 2) Right Amount; 3) Too Much.” This independent variable will be tested against 107)

EXECUTE? as a dependent variable that indicates support toward capital punishment. The two

variables are sourced from the General Social Survey (GSS) 2006.

Table 8 displays the results of the cross tabulation between Support for Capital

Punishment and Crime Spending Opinion. There are three categories listed across the top of the

contingency table, which characterizes the independent variable: respondent’s opinion on

spending regarding halting the crime rate. The categories are displayed into “Too Little being

35

Spent on Crime,” “Right Amount being Spent on Crime,” and “Too Much being Spent on

Crime.” The left side is the same.

In doing the cross tabulation, the results produced a statistical significance of prob=0.001.

This value implies that there is 1 chance out of 1000 that the relationship does not exist in the

population from which the sample was selected. This figure suggests that the relationship is

statistically significant. Since, both the variables are ordinal, Gamma will be employed as the

measure of association to test the strength of the relationship. The Gamma for the association is

0.176, which tells us that the two variables has a weak relationship with each other.

Table 8: Support for Capital Punishment by Crime Spending Opinion

Support for Capital

Punishment

Opinion on Spending Regarding Halting the Crime Rate

Too Little

being Spent

on Crime

Right Amount

being Spent on

Crime

Too Much

being Spent on

Crime

Missing

Total

Oppose

28.0%

(236)

36.1%

(157)

37.5%

(34)

443

31.2%

(427)

Favor

72.0%

(607)

63.9%

(278)

62.5%

(57)

12

68.8%

(942)

Missing

37

28

4

1627

1696

Total

100.0%

(843)

100.0%

(434)

100.0%

(91)

3073

1369

P=0.001 Gamma= 0.176

This relationship is statistically significant but weak. However, we will still analyze the

table accordingly. It is also evident that within the distribution of data, the results of the cross

tabulation between crime spending opinion and support for capital punishment, supports the

hypothesis. For respondents who think too much is being spent on crime, 37.5% of them oppose

capital punishment. However, a lower percentage of them who think too little is being spent on

crime (28.0%) oppose capital punishment. This finding, therefore, backs up the hypothesis that

36

those who oppose more spending on halting the crime rate are more likely to oppose the death

penalty than those who think too little is being spend on halting the crime rate.

Financing the death penalty was a big empirical argument used against capital

punishment. Scholars such as Gradess and Davies (2009) have concluded that for the past 25

years, in practically all of the states studied persistently show that the death penalty costs more

than life in prison. In such scenario, people who think too much is being spent on crime are

logically bound to oppose the death penalty. The distribution of data within the table fits within

that narrative.

I. Support for Capital Punishment by Income

The ninth hypothesis states that those with a higher income are more likely to

support capital punishment. This hypothesis is operationalized using the variable 56)INCOME as

an independent variable which poses the question “Respondent’s family income range 1) Low;

2) Middle; 3) High.” This independent variable will be tested against 106) EXECUTE? as a

dependent variable that indicates support toward capital punishment. The two variables are

sourced from the General Social Survey (GSS) 2008.

Table 9 displays the results of the cross tabulation between Support for Capital

Punishment and Income. There are three categories listed across the top of the contingency table,

which characterizes the independent variable: respondent’s opinion on court’s handling of

criminals. The categories are displayed into “Low” which represents those who fall under low

income category, “Middle” for those who fall under middle income category, and “High” for

those who fall under high income category. The left side is the same.

In doing the cross tabulation, the results produced a statistical significance of prob=0.00.

This value implies that there is 0 chance out of 100 that the relationship does not exist in the

37

population from which the sample was selected. This figure suggests that the relationship is

statistically significant. Since, both the variables are ordinal, Gamma will be employed as the

measure of association to test the strength of the relationship. The Gamma for the association is

0.135, which tells us that the two variables has a weak relationship with each other.

Table 9: Support for Capital Punishment by Income

Support for Capital Punishment

Income Category

Low

Middle

High

Missing

Total

Oppose

38.6%

(267)

33.2%

(312)

29.3%

(467)

55

32.4%

(1046)

Favor

61.4%

(425)

66.8%

(626)

70.7%

(1127)

83

67.6%

(2178)

Missing

38

35

107

17

197

Total

100.0%

(691)

100.0%

(938)

100.0%

(1594)

155

3224

P=0.00 Gamma= 0.135

The data in this table demonstrates that 70% of the respondents with high income express

support for capital punishment, while 61.4% of the respondents with low income express support

for capital punishment. This small but significant difference in the two categories demonstrates

that the finding supports the hypothesis that those with higher income are more likely to support

capital punishment.

Income plays a role in making a difference toward support for capital punishment.

Although it is not a significant contribution, it should not, nevertheless, be taken away from the

discussion. Bohm (1999) reiterates that those with low income are more susceptible to be

sentenced the death penalty than those with high income. In such scenario, those with high

income would have less qualms about the death penalty than those with low income. Thus,

people with high income are more likely to support capital punishment.

38

The next section. Implications and Conclusion, will dive deeper into the proven

contributing factors toward the support for capital punishment, and will answer the research

question.

Implications and Conclusion

The goal of this paper was to point out important factors toward the support for capital

punishment in determining the research question: “What accounts for differences in attitudes

among Americans concerning capital punishment?” There are ongoing debates about capital

punishment, and there is room for changes in ideologies and mindset toward both for and anti-

capital punishment. It is not a black and white situation at this age because one cannot just

determine capital punishment as right or wrong. Furthermore, it is not just rational facts that

people take into account, but several other determinations that people take into account while

determining capital punishment as right or wrong. To identify these factors, these variables were

divided into three sub-categories: Political, Social, and Economic.

The Findings and Analysis section shows that people who affiliate themselves with

Republicans, those with a favorable opinion of courts, those who have high confidence in the

government, those who are white, and those who think racial disparities do not exist are more

likely to support capital punishment than others. The cross tabulations for the stated independent

variables yielded a strong relationship and a significant data distribution pattern within the

contingency table. The sub-category that expresses the greatest support for capital punishment is

political, which includes party affiliation as a variable that yielded the strongest relationship in

this research.

Party Affiliation has the greatest effect on support for capital punishment. Republicans

have greater support for capital punishment than Democrats. The main reason behind this is the

39

party ideology. Republican party manifesto clearly states their support for capital punishment,

and the states’ right to enact capital punishment sentencing (Republicans 2016). While

Democratic party manifesto states their disdain for capital punishment (Democrats 2016)..

Therefore, candidates in the Republican party can use this information and favor the death

penalty to procure more votes and cement their conservatism. While candidates in the

Democratic party may shift their policy toward the death penalty by not striking down the death

penalty completely, but working to make it more fair and efficient. The second option for the

Democrats is to shift the majority’s public opinion on the death penalty by educating the public

of the research done by Bohm(1999) and Kronenwetter (1993), and to put more effort into social

movements that oppose capital punishment.

Another strong factor within the political category that contributes significantly to the

support for capital punishment is people’s confidence in the government. The future of the status

of capital punishment depends on people’s confidence in the government. If the government is to

maintain high confidence within its citizenry, the institution of capital punishment will be

favored for the foreseeable future.

There are certain variables in this research that have generated unexpected results, which

proves to something more radical regarding people’s attitude towards capital punishment, which

this paper argues should not be neglected completely. Some cross tabulations generated a low

value for the test of statistical significance, and a high value for measures of association that

deem those variables as too weak to consider. However, after the analysis of data, it points the

variables to another direction which could be useful for future political scholars researching in

this field. Two examples of such cross tabulations for independent variables are religion and

education.

40

Religion, yielded an insignificant relationship. The factor of religiosity showed no

difference in the support of capital punishment. This can be due to the fact that religiosity may

not play a significant role in deciding support for capital punishment but a different variable that

focusses on the specific religion of the respondents could yield a significant relationship.

Therefore, what is needed for better understanding between religion and support for capital

punishment would be current data that measures the specific religion in a more efficient manner.

Education, surprisingly in this research yielded almost an insignificant relationship. The

factor of whether an individual with more education or less education showed essentially no

difference in the support of capital punishment. This points to a fact that rational fact comes

second to emotional value when a person makes a political decision. This new finding could

build up into good research where political scholars can study the relationship between political

choice and emotional value toward issues.

This research paper has found numerous factors that attribute to support capital

punishment, but it is not all exhaustive. With the findings regarding race and racial disparities,

there is a need to focus on more profound research within American political institutions to

determine whether discrimination in capital punishment sentencing is still occurring. Research

about capital punishment is a continuous one, and new and improved data will clarify the factors

that shape American’s attitude towards capital punishment.

In determining American’s attitude towards capital punishment, political variables are the most

significant. However, more research is recommended here as well to examine all of the

implications and explanations in these segments of factors that influence support for capital

punishment.

41

Bibliography:

Banner, Stuart. 2002. The Death Penalty: An American History. Cambridge, Massachusetts:

Harvard University Press.