REPORT REVIEWING RESEARCH ON PAYDAY, VEHICLE TITLE, AND HIGH-COST

INSTALLMENT LOANS

May 14, 2019

S. Ilan Guedj, PhD

Bates White Economic Consulting

Report reviewing research on payday, vehicle title, and high-cost installment loans

Page i

Table of contents

I. Summary of research on payday, vehicle title, and high-cost installment loans................................................... 1

II. What are covered loans and how are they used? ............................................................................................... 2

III. Borrowers of covered loans are disproportionately low-income and disproportionately minorities ..................... 6

IV. Lenders of covered loans target communities with a high concentration of minorities .................................... 11

V. Lenders of covered loans charge higher prices in minority neighborhoods ...................................................... 19

VI. Borrowers of covered loans may not understand the loan terms or the risks associated with the loan ........... 22

VII. Access to covered loans can have negative impacts on consumers .............................................................. 26

VIII. Conclusions ................................................................................................................................................... 29

Appendix A. Materials cited................................................................................................................................. A-1

Report reviewing research on payday, vehicle title, and high-cost installment loans

Page ii

List of figures

Figure 1. Payday loan borrowers have substantially lower incomes ....................................................................... 7

Figure 2. Payday loan borrowers are disproportionately African Americans and Hispanics ................................... 9

Figure 3. US armed forces have a disproportionately high concentration of African Americans ........................... 10

Figure 4: Top neighborhood factors explaining payday lender storefront proximity .............................................. 13

Figure 5: Top neighborhood factors explaining payday lender storefront concentration ....................................... 14

Figure 6: Top neighborhood factors explaining bank branch proximity ................................................................. 14

Figure 7: Top neighborhood factors explaining bank branch concentration .......................................................... 15

Figure 8: Percentages of storefront payday and vehicle title loan advertisements with pictures of minorities in

Houston, Texas ..................................................................................................................................................... 18

Figure 9: African Americans pay on average higher rates on mortgages ............................................................. 21

Report reviewing research on payday, vehicle title, and high-cost installment loans

Page 1

I. Summary of research on payday, vehicle title, and high-cost

installment loans

This report summarizes research regarding payday, vehicle title, and high-cost installment loans, with

a particular focus on the predatory nature of such “fringe” financial services in targeting certain

minority demographics. Hereinafter, this report refers to these three categories of loans as “covered

loans.”

1

Research on covered loans reveals the following overarching conclusions:

Consumers of covered loans are disproportionately low income and disproportionately African

American or Hispanic.

Lenders of covered loans geographically target minority consumers and communities with high

concentrations of African American, Hispanic, and low-income households. Several studies

present evidence that lenders of covered loans also utilize marketing schemes to target minorities.

Lenders of covered loans charge higher prices in minority neighborhoods, consistent with race-

based price discrimination. A number of studies also document price discrimination against

minorities in traditional banking and mortgage lending.

Consumers of covered loans may not understand the terms of and the risks of prolonged

indebtedness associated with taking out covered loans. Lenders of covered loans often do not

comply with information disclosure laws and regulations. Borrowers of covered loans tend to

have low financial literacy and be overly optimistic or impatient about their future income.

Access to covered loans can have a negative impact on the readiness and performance of military

personnel and consumers’ financial well-being, ability to prioritize other liabilities and

responsibilities, and overall health.

1

In its 2017 Final Rule, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) referred to payday, vehicle title, and certain

high-cost installment loans as “covered loans.” 12 CFR § 1041 (2017) [hereinafter “2017 Final Rule”] at 54512. In the

finance literature, the term “covered” also refers to the fact that a debt obligation is backed by a pool of assets, e.g.,

covered bonds. See, e.g., Barbara Petitt, Jerald Pinto, Wendy Pirie, and Bob Kopprasch, Fixed Income Analysis, 3rd ed.

(Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2015), 14. In this report, “covered loans” exclusively refer to payday, vehicle title,

and certain high-cost installment loans.

Report reviewing research on payday, vehicle title, and high-cost installment loans

Page 2

II. What are covered loans and how are they used?

The financial services industry has expanded beyond the traditional financial services offered by

regulated financial institutions, such as banks and credit unions. A variety of nontraditional or

“fringe” financial service providers have grown in popularity, providing alternative forms of financial

services to consumers. The prevalence of fringe lending has led to considerable debate in both

academic and regulatory circles. This report focuses on three types of fringe lending: payday loans,

vehicle title loans, and high-cost installment loans, together referred to in this report as “covered

loans.”

2

Payday loans are small, high-cost loans that are typically structured as single-payment, i.e., closed-

end, loans with due dates that coincide with a borrower’s next payday. Because the due dates are

scheduled in this manner, loan terms are typically two weeks. However, the specific loan terms can be

shorter or longer, depending on the borrower’s pay frequency.

3

When taking out a payday loan, borrowers often provide a post-dated personal check or an

authorization to electronically debit their deposit account for the amount due, which is the sum of the

loan amount and the associated fees. Although the check or authorization essentially serve as a form

of security for the loan, borrowers generally return to the store when the loan is due to repay in

person. If a borrower does not return to the store when the loan is due, the lender has the option of

depositing the borrower’s check or initiating an electronic withdrawal from the borrower’s deposit

account.

4

A variant on storefront payday loans that has gained traction in recent years is online

payday loans. Online payday lenders often use the Automated Clearing House system to deposit the

loan amounts directly into borrowers’ checking accounts. To collect payments, lenders submit a

payment request to the borrower’s depository institution through the same system.

5

In both storefront

and online payday lending, typically no credit check or underwriting is involved.

6

Vehicle title loans are a type of loan in which the consumer borrows against the value of his or her

vehicle. The lender takes a security interest in the borrower’s vehicle and determines the loan amount

2

Id.

3

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, “Payday Loans and Deposit Advance Products: A White Paper of Initial Data

Findings” (white paper, Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Apr. 24, 2013), available at

https://www.consumerfinance.gov/data-research/research-reports/white-paper-on-payday-loans-and-deposit-advance-

products/.

4

Id.

5

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, “Online Payday Loan Payments” (white paper, Consumer Financial Protection

Bureau, Apr. 2016), available at https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201604_cfpb_online-payday-loan-payments.pdf.

6

Center for Responsible Lending, “Payday Mayday: Visible and Invisible Payday Lending Defaults” (research paper,

Center for Responsible Lending, Mar. 31, 2015), available at https://www.responsiblelending.org/research-

publication/payday-mayday-visible-and. This paper uses data from multiple publicly available sources.

Report reviewing research on payday, vehicle title, and high-cost installment loans

Page 3

based on the value of the vehicle. Similar to payday loans, vehicle title loans are relatively small but

high-cost loans made by fringe financial service providers. Four key differences distinguish vehicle

title loans from payday loans. First, as opposed to having due dates that coincide with a borrower’s

payday, vehicle title loans are often due in about a month, regardless of the borrower’s pay frequency.

Second, instead of giving the lender a post-dated check or authorization to withdraw payments from a

bank account, a vehicle title borrower provides the lender the title to his or her car, which generally

must be owned free and clear of any liens. Although the borrower retains use of the car while the loan

is outstanding, the lender can repossess and sell the vehicle if payments are not made on time to

satisfy the amount owed. Third, vehicle title borrowers do not need to have an account with a bank or

a credit union. Finally, while payday loans are offered both in store (at physical locations) and online,

vehicle title loans are typically issued at physical locations so the lender can assess the condition of

the vehicle.

7

Many payday and vehicle title lenders offer similar high-cost, closed-end installment loans. These

installment loans are characterized by a payment schedule that consists of either multiple fully

amortizing payments of similar sizes or a series of smaller payments followed by a larger balloon

payment at the end of the loan term. Payday installment loans are offered both in store and online,

while vehicle-title installment loans are generally offered only at storefronts, given the need to assess

the condition of the vehicle.

8

Two common features of covered loans are their high cost and their tendency to induce sustained use

by borrowers. The average cost of a two-week $500 payday loan is $75, which corresponds to an

annual percentage rate (APR) of 391%.

9

A typical vehicle title loan has a term of one month and a

median loan size just under $700, with fees that are equivalent to an APR of around 300%.

10

Installment payday loans are generally larger than single-payment payday loans, with a median size

of $1,000 storefront and $2,400 online and an overall median APR of 248% storefront and 221%

online.

11

Installment vehicle title loans have a median size of $710 and a median APR of 259%.

12

For

comparison, the average APR for all credit card accounts in the United States was 12.89% and

14.22% in 2017 and 2018, respectively.

13

The average APR for credit card accounts that were

7

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, “Single-Payment Vehicle Title Lending” (Consumer Financial Protection

Bureau, May 18, 2016), available at https://www.consumerfinance.gov/data-research/research-reports/single-payment-

vehicle-title-lending/.

8

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, “Supplemental Findings on Payday, Payday Installment, and Vehicle Title

Loans, and Deposit Advance Products” (Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, June 2, 2016), available at

https://www.consumerfinance.gov/data-research/research-reports/supplemental-findings-payday-payday-installment-

and-vehicle-title-loans-and-deposit-advance-products/.

9

Supra note 3, at 9.

10

Supra note 7, at 6.

11

Supra note 8, at 13.

12

Id.

13

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, “Consumer Credit – G.19,” Apr. 5, 2019, available at

https://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g19/current/.

Report reviewing research on payday, vehicle title, and high-cost installment loans

Page 4

assessed interest was 14.44% and 16.04% in 2017 and 2018, respectively.

14

The average APR for new

car loans from financial companies in 2017 and 2018 was 5.4% and 6.1%, respectively.

15

Payday loans are often advertised as short-term solutions for unexpected expenses such as a medical

emergency or a car repair. However, more than half of payday loan borrowers take out payday loans

to cover a recurring expense, such as “utilities, credit card bills, rent or mortgage payments, or food,”

and less than 20% use payday loans to deal with unexpected expenses.

16

After the initial loan is taken

out, borrowers of payday loans, on average, renew their debt seven times within the year, which is

equivalent to staying indebted for approximately five months.

17

Evidence suggests that the payday

lending business model “depends upon heavy usage—often renewals by borrowers who are unable to

repay upon their next payday—for its profitability.”

18

“In a state with a $15 per $100 rate, an operator

. . . will need a new customer to take out 4 to 5 loans before that customer becomes profitable.”

19

The

financial performance of the payday lending industry is significantly enhanced by the successful

conversion of occasional users into chronic borrowers.

20

Despite the recurrent nature of the products,

“payday loans continue to be packaged as short-term or temporary products.”

21

Similarly, only one-quarter of borrowers use vehicle title loans for unexpected expenses, while half

report using them to pay regular bills.

22

A typical 30-day vehicle title loan is refinanced 8 times.

23

The

annual repossession rate, which is the percentage of vehicle title loans that default and have the

collateralized vehicles repossessed by the lender, is 6%–11%.

24

For comparison, the percentage of

vehicle loans offered by traditional financial service providers that became 90 or more days

delinquent (a precursor to being repossessed) during the period 2010–2017 was around 2%.

25

One-

14

Id.

15

Id.

16

Pew Charitable Trusts, “Payday Lending in America: Who Borrows, Where They Borrow, and Why” (Pew Charitable

Trusts, July 19, 2012), available at https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/reports/2012/07/19/who-

borrows-where-they-borrow-and-why [hereinafter “Pew (2012)”], 5. This study uses survey data collected by the Pew

Charitable Trusts.

17

Id., at 4.

18

Id., at 7.

19

Id., at 7.

20

Michael A. Stegman and Robert Faris, “Payday Lending: A Business Model that Encourages Chronic Borrowing,”

Economic Development Quarterly 17, no. 1 (2003): 8–32 [hereinafter “Stegman and Faris (2003)”]. This paper uses

publicly available data from North Carolina.

21

Supra note 18.

22

Pew Charitable Trusts, “Auto Title Loans: Market practices and borrowers’ experiences” (Pew Charitable Trusts, Mar.

25, 2015), available at https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/reports/2015/03/auto-title-loans, 1. This

study uses both survey data collected by the Pew Charitable Trusts and publicly available data.

23

Center for Responsible Lending, “Car Title Lending: Disregard for Borrowers’ Ability to Repay” (Center for

Responsible Lending, May 13, 2014), available at https://www.responsiblelending.org/research-publication/car-title-

lenders-ignore, 3. This paper uses private data from the car title lending industry.

24

Supra note 22.

25

Federal Reserve Bank of New York, “Quarterly Report on Household Debt and Credit, 2018 Q4,” Feb. 2019, available

at https://www.newyorkfed.org/microeconomics/hhdc.html, 14.

Report reviewing research on payday, vehicle title, and high-cost installment loans

Page 5

third of all vehicle title loan borrowers do not have another working vehicle in their households other

than the vehicle used as collateral to secure the loan.

26

Other segments of the high-cost, short-term credit market exhibit a similar pattern of sustained usage

through frequent renewal. Twenty percent of vehicle title installment loans are refinanced, which

means that a subsequent installment loan was used to repay the loan or was taken out the same day

that the prior loan was repaid, while 37% of payday installment loans are refinanced.

27

26

Supra note 22.

27

Supra note 8.

Report reviewing research on payday, vehicle title, and high-cost installment loans

Page 6

III. Borrowers of covered loans are disproportionately low-

income and disproportionately minorities

A key question in the literature is who uses covered loans. On this question, lenders of covered loans

argue that their customers are primarily middle class.

28

Lenders of covered loans cite a 2001 study by

Gregory Elliehausen and Edward Lawrence that shows that more than half of the consumers of

payday loans have an annual family income between $25,000 and $49,999.

29

The payday lending

industry generally interprets this statistic as showing that their primary consumers are middle class

and thus asserts that payday lending does not take advantage of the poor and underprivileged.

30

Similarly, the auto title lending industry also relies on “questionable data to conclude that its

customers are predominantly middle class.”

31

Todd Zywicki claims that “the typical title loan

customer for [the American Association of Responsible Auto Lenders] members is 44 years old and

has a household income of more than $50,000 per year.”

32

Several studies criticize the findings by Elliehausen and Lawrence.

33

Moreover, a number of studies

show important differences between payday loan borrowers and non-payday loan borrowers along the

dimensions of income, race, and ethnicity. For example, using data from the 2007 Survey of

Consumer Finance, Amanda Logan and Christian Weller find that the average family that took out a

payday loan has substantially lower income, is less likely to have savings, and is less likely to be a

homeowner than the average family without payday loans.

34

Specifically, Logan and Weller find that

28

See, e.g., Nathalie Martin and Ernesto Longa, “High-Interest Loans and Class: Do Payday and Title Loans Really Serve

the Middle Class?” Loyola Consumer Law Review 24, no. 4 (2012): 530 [hereinafter “Martin and Longa (2012)”]. This

study contains a detailed review of the studies on both sides of the “middle class myth” and their own analysis on the

income level of payday loan borrowers in New Mexico using publicly available data. For comparison, Pew (2012) finds

that payday borrowing is concentrated among households with annual income less than $40,000.

29

Gregory Elliehausen and Edward Lawrence, “Payday Advance Credit in America: An Analysis of Customer Demand”

(Credit Research Center, Washington, DC, 2001). This study also finds payday loan borrowers are primarily and

disproportionately young adults (younger than 45), primarily married or living with partner but disproportionately

divorced or separated, primarily and disproportionately either younger than 45 and married with children or at any age

and unmarried with children, and primarily and disproportionately lack of college degree. In addition, disproportionately

low percentages of payday loan borrowers have bank cards compared to the general adult population. This paper uses

private data from a payday lending industry trade group.

30

“It may seem obvious that few middle class people would choose to pay 300% interest or more for a short-term credit

product. Nevertheless, payday and title lenders . . . repeatedly claim that these lenders draw their clientele primarily

from the middle class.” Martin and Longa (2012).

31

Martin and Longa (2012), 532.

32

Todd Zywicki, “Consumer Use and Government Regulation of Title Pledge Lending,” Loyola Consumer Law Review

22, no. 4 (2010): [hereinafter “Zywicki (2010)”] 442. This paper uses data from multiple publicly available sources.

33

See, e.g., Martin and Longa (2012) and John Caskey, “Payday Lending: New Research and the Big Question” (working

paper, Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, 2010) [hereinafter “Caskey (2010)”]. Martin and Longa (2012) point out

the potential response bias in telephone and the low 8% response rate (427 interviewers of the 5,364 sample responded

and finished the telephone survey). Caskey (2010) notes that data from consumer telephone survey are less reliable than

data coming directly from lenders or regulators, as survey data are not corroborated by documentary evidence.

34

Amanda Logan and Christian Weller, “Who Borrows From Payday Lenders? An Analysis of Newly Available Data”

Report reviewing research on payday, vehicle title, and high-cost installment loans

Page 7

the median and mean income of payday loan borrowers was $30,892 and $32,614, respectively, while

individuals who did not take out payday loans have a respective median and mean income of $48,397

and $85,473.

35

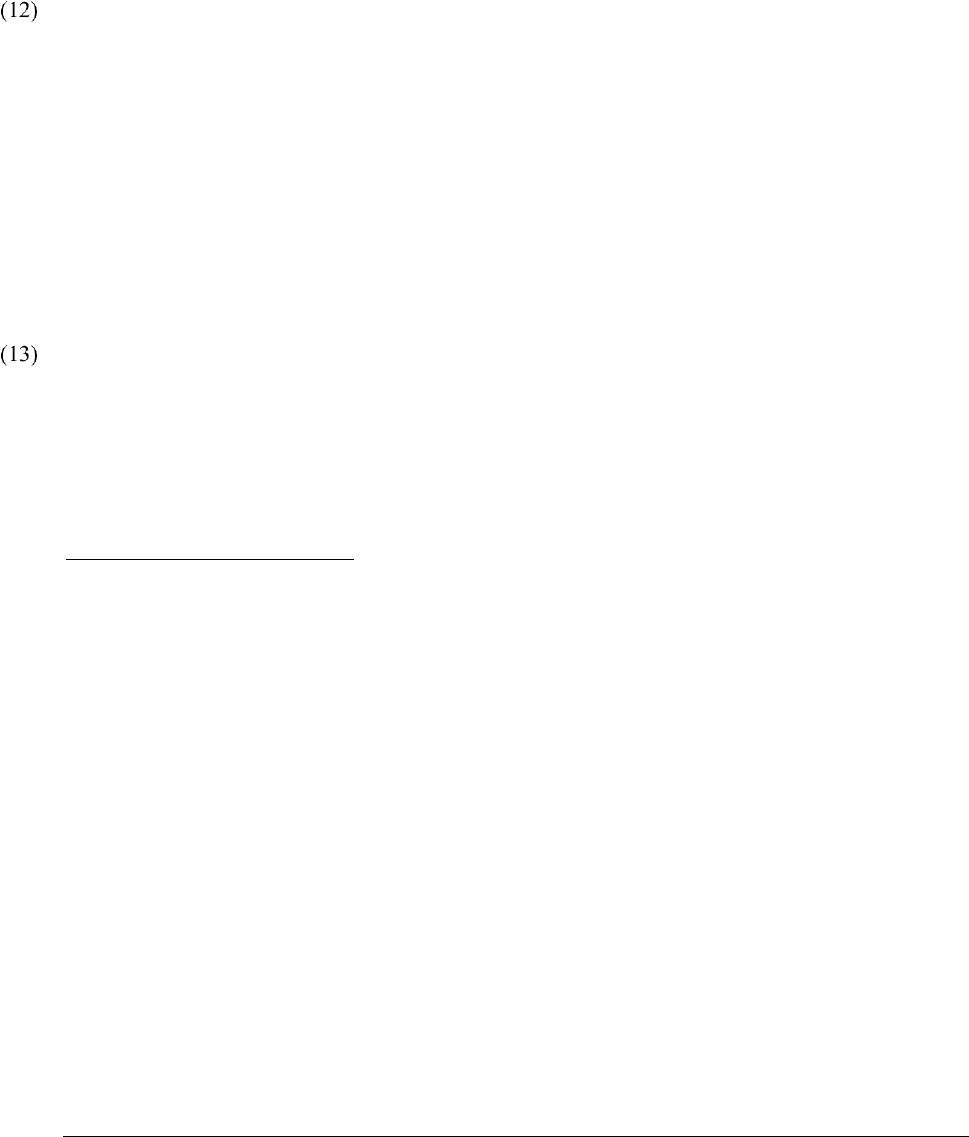

Figure 1 compares the average and median income of payday loan borrowers to non-

payday loan borrowers.

Figure 1. Payday loan borrowers have substantially lower incomes

Source: Logan and Weller (2009).

Several studies find consumers of covered loans to be disproportionately African American

36

and

disproportionately Hispanic.

37

Researchers at the Pew Charitable Trusts utilize a logistic regression

(CAP report, Center for American Progress, Mar. 2009), available at https://cdn.americanprogress.org/wp-

content/uploads/issues/2009/03/pdf/payday_lending.pdf [hereinafter “Logan and Weller (2009)”]. This paper uses

publicly available data from the Federal Reserve.

35

Id., at 8.

36

See, e.g., Pew (2012) and Mary Caplan, Peter Kindle, and Robert Nielsen, “Do We Know What We Think We Know

about Payday Loan Borrowers? Evidence from the Survey of Consumer Finances,” Journal of Sociology & Social

Welfare 44, no. 4 (2017): 19–43 [hereinafter “Caplan et al. (2017)”] on consumers of payday loans. Caplan et al. (2017)

use data from the 2013 Survey of Consumer Finances. See, e.g., Kathryn Fritzdixon, Jim Hawkins, and Paige Marta

Skiba, “Dude Where’s My Car Title? The Law, Behavior, and Economic of Title Lending Markets,” University of

Illinois Law Review, 2014, no. 4: 1014–58 [hereinafter “Fritzdixon et al. (2014)”] on consumers of auto title loans. For

consumers of multiple types of high-cost fringe lending products (including payday loans and vehicle title loans), see

Rob Levy and Joshua Sledge, “A Complex Portrait: An Examination of Small-Dollar Credit Consumers” (CFSI report,

Center for Financial Services Innovation, Aug. 2012), available at

https://www.fdic.gov/news/conferences/consumersymposium/2012/a%20complex%20portrait.pdf [hereinafter “Levy

and Sledge (2012)”]. Fritzdixon et al. (2014) and Levy and Sledge (2012) use survey data collected by the authors. For

the unbanked and underbanked population, see Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, “2015 FDIC National Survey of

Unbanked and Underbanked Households” (FDIC Report, Oct. 20, 2016), available at

https://www.fdic.gov/householdsurvey/2015/2015report.pdf [hereinafter “FDIC (2016)”]; and Federal Deposit Insurance

Corporation, “2017 FDIC National Survey of Unbanked and Underbanked Households” (FDIC report, Oct. 2018),

Report reviewing research on payday, vehicle title, and high-cost installment loans

Page 8

model to evaluate how certain characteristics relate to payday credit usage, while controlling for

factors such as age, gender, education, marital status, paternal status, and income. They find that the

odds of using payday credit are 105% higher for African Americans than for other races and

ethnicities.

38

Mary Caplan and co-authors use the 2013 Survey of Consumer Finance data and regression

techniques to study what borrowers are more likely to use payday loans. They find payday loan

borrowers are more likely to be African American, to lack a college degree, and to live in a home they

do not own. Recipients of social assistance were approximately five times more likely to be payday

loan borrowers than those who did not receive social assistance.

39

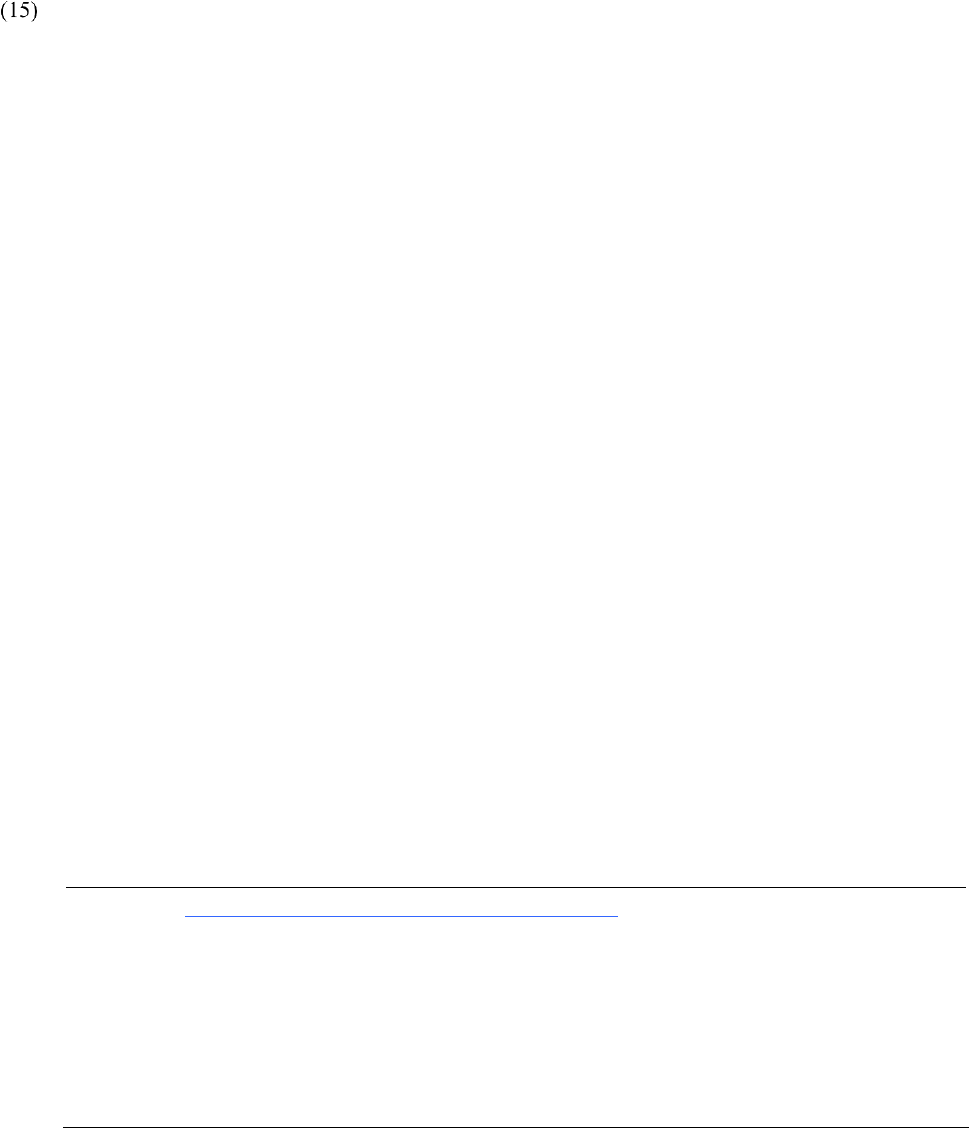

Figure 2 shows that the proportion

of whites among payday loan borrowers is 22 percentage points lower than the proportion of whites

in the general population. By contrast, the proportions of African Americans and Hispanics among

payday loan borrowers are significantly higher than the proportions of the two groups in the general

population (20 percentage points higher for African Americans and 4 percentage points higher for

Hispanics).

40

available at https://www.fdic.gov/householdsurvey/2017/2017report.pdf [hereinafter “FDIC (2018)”]. Both FDIC

(2016) and FDIC (2018) use publicly available data from the FDIC.

37

See, e.g., Fritzdixon et al. (2014) on consumers of auto title loans, Levy and Sledge (2012) on consumers of multiple

types of high-cost fringe lending products (including payday loans and vehicle title loans), and FDIC (2016) and FDIC

(2018) on the unbanked and underbanked population.

38

Pew (2012), 9.

39

Caplan et al. (2017).

40

Id., at 32.

Report reviewing research on payday, vehicle title, and high-cost installment loans

Page 9

Figure 2. Payday loan borrowers are disproportionately African Americans and Hispanics

Source: Caplan et al. (2017).

Michael Stegman and Robert Faris find that, in North Carolina, lower-income African American

families are more than twice as likely to have taken out a payday loan as non-Hispanic white

families.

41

Contrary to the authors’ expectation, Hispanic families are less likely to take out payday

loans than non-Hispanic white families, potentially due to a higher tendency to use pawnshops among

Hispanic families in North Carolina.

42

Kathryn Fritzdixon and co-authors conducted a survey in 2012 of 450 vehicle title borrowers in three

states (Texas, Idaho, and Georgia). Comparing the racial composition of vehicle title borrowers with

statewide figures, they find that, in two of the three states, vehicle title consumers are

disproportionately African American (Texas and Georgia) and disproportionately Hispanic (Idaho

and Georgia).

43

Rob Levy and Joshua Sledge find a disproportionately high concentration of African Americans and

Hispanics among consumers of “small-dollar credits,” a generic term encompassing payday loans,

vehicle title loans, installment loans, pawn loans, and direct deposit loans.

44

41

Stegman and Faris (2003).

42

Id., at 17.

43

Fritzdixon et al. (2014).

44

Levy and Sledge (2012).

Report reviewing research on payday, vehicle title, and high-cost installment loans

Page 10

Moreover, researchers find that military personnel are also more likely to take out payday loans. An

internal study conducted by the Department of Defense (DOD) estimates that “military members are

twice as likely as civilians to be a payday borrower.”

45

Steven Graves and Christopher Peterson point

out in their 2005 study that the US armed forces have a disproportionately high concentration of

African Americans.

46

Figure 3 shows that the proportion of African Americans in the enlisted military

personnel is much higher than in the civilian population.

Figure 3. US armed forces have a disproportionately high concentration of African Americans

Source: Population Representation in the Military Services, Fiscal Year 2017, Table B-17.

45

US Department of Defense, “Report on Predatory Lending Practices Directed at Members of the Armed Forces and

Their Dependents” (DOD report, Aug. 9, 2006), available at

http://archive.defense.gov/pubs/pdfs/report_to_congress_final.pdf, 13. This report uses survey data collected by the US

Department of Defense.

46

Steven Graves and Christopher Peterson, “Predatory Lending and the Military: The Law and Geography of ‘Payday’

Loans in Military Towns,” Ohio State Law Journal 66, no. 4 (2005): 653–832. This paper uses data from multiple

publicly available sources.

Report reviewing research on payday, vehicle title, and high-cost installment loans

Page 11

IV. Lenders of covered loans target communities with a high

concentration of minorities

Studies using geographic locations of lenders of covered loans in several states find evidence that the

numbers of lenders of covered loans are higher in communities with high concentrations of low-

income individuals/households,

47

African Americans,

48

Hispanics,

49

immigrants,

50

and others less

likely to speak English.

51

In addition, communities in which a high concentration of residents are

younger,

52

elderly,

53

undereducated,

54

and receive public assistance

55

also appear to have significantly

more storefront locations and a higher density of lenders of covered loans.

47

See, e.g., Steven Graves, “Landscapes of Predation, Landscapes of Neglect: A Location Analysis of Payday Lenders and

Banks,” The Professional Geographer 55, no. 3 (2003): 303–17 [hereinafter “Graves (2003)”]; William Apgar and

Christopher Herbert, “Subprime Lending and Alternative Financial Service Providers: A Literature Review and

Empirical Analysis” (US Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Policy Development and Research

paper, 2006), available at https://www.huduser.gov/Publications/pdf/sublending.pdf [hereinafter “Apgar and Herbert

(2006)”]; Alice Gallmeyer and Wade Roberts, “Payday Lenders and Economically Distressed Communities: A Spatial

Analysis of Financial Predation,” Social Science Journal 46 (2009): 521–38 [hereinafter “Gallmeyer and Roberts

(2009)”]; and Martin and Longa (2012) on locations of payday lenders. Similar results are found in studies on other

types of high-cost fringe lenders. See Matt Fellowes and Mia Mabanta, “Banking on Wealth: America’s New Retail

Banking Infrastructure and Its Wealth-Building Potential” (Brookings Institution, Jan. 22, 2008), available at

https://www.brookings.edu/research/banking-on-wealth-americas-new-retail-banking-infrastructure-and-its-wealth-

building-potential/ on locations of payday lenders and pawnshops. All of these studies use publicly available data.

48

See, e.g., Graves (2003); Matt Burkey and Scott Simkins, “Factors Affecting the Location of Payday Lending and

Traditional Banking Services in North Carolina,” Review of Regional Studies 34, no. 2 (2004): 191–205 [hereinafter

“Burkey and Simkins (2004)”]; Uriah King, Wei Li, Delvin Davis, and Keith Ernst, “Race Matters: The Concentration

of Payday Lenders in African-American Neighborhoods in North Carolina” (Center for Responsible Lending, Mar. 22,

2005), available at https://www.responsiblelending.org/research-publication/race-matters-concentration-payday-lenders-

african-american-neighborhoods-0 [hereinafter “King et al. (2005)”]; Wei Li, Leslie Parrish, Keith Ernst, and Delvin

Davis, “Predatory Profile: The Role of Race and Ethnicity in the Location of Payday Lenders in California” (Center for

Responsible Lending, Mar. 26, 2009), available at https://www.responsiblelending.org/research-publication/predatory-

profiling [hereinafter “Li et al. (2009)”]; and Delvin Davis, “Mile High Money: Payday Stores Target Colorado

Communities of Color” (Center for Responsible Lending, Feb. 2018) [hereinafter “Davis (2018)”] on locations of

payday lenders. Similar results are found in studies on other types of high-cost fringe lenders. See, e.g., Robin Prager,

“Determinants of the Locations of Payday Lenders, Pawnshops and Check-Cashing Outlets” (working paper 2009-33,

Finance and Economics Discussion Series, Federal Reserve Board, 2009) [hereinafter “Prager (2009)”] on locations of

payday lenders, pawnshops, and check cashers; and Kenneth Temkin and Noah Sawyer, “Analysis of Alternative

Financial Service Providers” (research report, The Urban Institute, Feb. 18, 2004), available at

https://www.urban.org/research/publication/analysis-alternative-financial-service-providers [hereinafter “Temkin and

Sawyer (2004)”] on locations of multiple types of high-cost fringe lenders (including payday and vehicle title lenders) in

several geographic regions. King et al. (2005) use data collected by authors. Prager (2009) uses publicly available data

from the Federal Reserve. Burkey and Simkins (2004), Temkin and Sawyer (2004), Li et al. (2009), and Davis (2018)

use multiple publicly available data sources.

49

See, e.g., King et al. (2005), Apgar and Herbert (2006), Li et al. (2009), and Davis (2018) on locations of payday

lenders. Similar results are found in studies on other types of high-cost fringe lenders. See, e.g., Temkin and Sawyer

(2004) on locations of multiple types of high-cost fringe lenders (including payday and vehicle title lenders) in several

geographic regions, and Jane Cover, Amy Fuhrman Spring, and Rachel Garshick Kleit, “Minorities on the Margins? The

Spatial Organization of Fringe Banking Services,” Journal of Urban Affairs 33, no. 3 (2011) on locations of payday

lenders, check cashers, and pawnbrokers. This paper uses data from multiple publicly available sources.

50

See Apgar and Herbert (2006).

51

See Burkey and Simkins (2004).

52

Id.

Report reviewing research on payday, vehicle title, and high-cost installment loans

Page 12

Mark Burkey and Scott Simkins study the location of banks and payday lenders in North Carolina and

find that areas with higher numbers of payday lenders have a higher concentration of African

American and Hispanic residents, as well as people who are less educated, are recent immigrants, and

receive public assistance. In a regression analysis, they find that even after controlling for income,

“urban-ness,” income inequality, and education, race is still a significant factor in determining the

number of payday lenders in a ZIP code tabulation area. In particular, they find that a 1% increase in

the population of African Americans would increase the number of payday lenders by 1% and reduce

the number of banks by 1%. A similar effect is found for increases in the Hispanic population,

although it is not statistically significant.

56

Uriah King and co-authors find similar results in a study of payday lenders in North Carolina at the

census tracts level.

57

The top fifth of census tracts by proportion of African Americans had more than

four times as many storefront payday lenders per capita as the bottom fifth of census tracts, even after

controlling for the effects of income and other variables. The concentration of payday lending stores

increases as the concentration of African Americans increases.

58

Wei Li and co-authors perform regression analyses to identify the top neighborhood factors that

determine the locations of storefront payday lenders in California after controlling for economic

differences.

59

They examine (1) the proximity of payday lenders, defined as the distance from the

center of a geographic region, i.e. census block group,

60

to the nearest payday lender, and (2) the

concentration of payday lenders around the census block group.

As shown in Figure 4 and Figure 5, the authors find that the population of African Americans and

Latinos explains more than 50% of the proximity and concentration of storefront payday lenders. This

means that more than half of the variation in the proximity and concentration of payday storefronts is

driven by the differences in the proportion of African Americans and Latinos in a given census block

53

See Gallmeyer and Roberts (2009).

54

See, e.g., Burkey and Simkins (2004), Apgar and Herbert (2006), and Prager (2009).

55

See, e.g., Burkey and Simkins (2004), Apgar and Herbert (2006), and Caplan et al. (2017).

56

Burkey and Simkins (2004).

57

Census tracts are small, relatively permanent statistical subdivisions of a county or equivalent entity and generally have

a population between 1,200 and 8,000 people, with an optimum size of 4,000 people. See United States Census Bureau,

“Glossary,” United States Census Bureau, available at https://www.census.gov/glossary/.

58

King et al. (2005).

59

Li et al. (2009).

60

Census blocks are statistical areas bounded by visible features, such as streets, roads, streams, and railroad tracks, and

by nonvisible boundaries, such as selected property lines and city, township, school district, and county limits and short

line-of-sight extensions of streets and roads. A cluster of blocks within the same census tract that have the same first

digit of their four-digit census block number consists a census block group. Census block groups are generally defined

to contain between 600 and 3,000 people, and are used to present data and control block numbering. United States

Census Bureau, “Glossary,” United States Census Bureau, available at https://www.census.gov/glossary/.

Report reviewing research on payday, vehicle title, and high-cost installment loans

Page 13

group. In contrast, education attainment and household income explain only 14% and 5%,

respectively, of payday lender proximity.

For comparison purpose, Figure 6 and Figure 7 show that the biggest neighborhood factors explaining

the proximity and concentration of bank branches are the number of retail employees and percentage

of homeowners, respectively. Race and ethnicity are not among the top factors in determining the

locations of bank branches.

Figure 4: Top neighborhood factors explaining payday lender storefront proximity

Source: Li et al. (2009).

Report reviewing research on payday, vehicle title, and high-cost installment loans

Page 14

Figure 5: Top neighborhood factors explaining payday lender storefront concentration

Source: Li et al. (2009).

Figure 6: Top neighborhood factors explaining bank branch proximity

Source: Li et al. (2009).

Report reviewing research on payday, vehicle title, and high-cost installment loans

Page 15

Figure 7: Top neighborhood factors explaining bank branch concentration

Source: Li et al. (2009).

Robin Prager studies nationwide data and finds that payday lenders are more concentrated in areas

where a large percentage of the population is African American. The paper also finds evidence that

payday lenders target areas where a higher proportion of the population has no or low credit scores.

Similar to Stegman and Faris’ finding, Prager does not find a higher concentration of payday lenders

in communities with a higher percentage of Hispanic residents.

61

James Barth and co-authors study the numbers of payday lenders in different states, and analyze how

the numbers of payday lenders relate to state-level demographic, financial, and educational

characteristics. Using regression techniques, their results show that states with higher percentages of

African Americans have significantly more payday lenders, even after controlling for financial and

educational characteristics.

62

Delvin Davis studies the locations of payday lenders in Colorado using 2016 state license data from

the Colorado Department of Law. The study finds that census tracts in Colorado with over 50%

African American and Latino populations are about twice as likely to have a payday store as all other

61

Prager (2009).

62

James Barth, Jitka Hilliard, and John Jahera, “Banks and Payday Lenders: Friends or Foes?” International Advances in

Economic Research 21, no. 2 (2015): 139–53. This paper uses data from multiple publicly available sources.

Report reviewing research on payday, vehicle title, and high-cost installment loans

Page 16

areas and seven times more likely to have a payday loan store than predominately white areas (below

10% African American and Latino population).

63

Similar results are also found in Florida.

64

Graves and Peterson show that, in 19 of the 20 states they studied, payday lenders were located in the

counties and ZIP codes adjacent to military bases in significantly greater numbers and densities than

other areas.

65

Graves and Peterson contend,

Some would argue that the neighborhoods [they] have examined near bases suffer

from poverty, have large minority populations, or high population densities, but this

is not the case. [They] have found most military neighborhoods to be relatively

prosperous, not particularly crowded, and generally unremarkable from a

demographic standpoint. Indeed, in several instances, such as Oceanside, California,

the neighborhood adjacent to the military base is affluent and without a large

minority population.

66

As mentioned earlier, the US armed forces have a disproportionately high concentration of African

Americans, and an academic study has found that the closure of Fort Ritchie Army Garrison reduced

demographic diversity, in particular the population of African Americans in nearby communities in

Cascade, Maryland dropped following the closure.

67

Following this study, the DOD conducted an internal study on the prevalence of payday lending to

military personnel and found that “predatory lending undermines military readiness, harms the morale

of troops and their families, and adds to the cost of fielding an all[-]volunteer fighting force.”

68

These

studies led to the legislation of a federal cap on loan rates to military members and their families

(36% APR, effective October 1, 2007).

69

63

Davis (2018).

64

Brandon Coleman and Delvin Davis, “Perfect Storm: Payday Lenders Harm Florida Consumers Despite State Law”

(policy brief, Center for Responsible Lending, Mar. 2016), available at

http://www.responsiblelending.org/sites/default/files/nodes/files/research-

publication/crl_perfect_storm_florida_mar2016.pdf. This paper uses data collected from the Florida Office of Financial

Regulation.

65

Supra note 46.

66

Id., at 825.

67

See Office of the Under Secretary of Defense, Personnel and Readiness, “Population Representation in the Military

Services: Fiscal Year 2017 Report,” Table B-17 (population report, US Department of Defense, 2017), available at

http://cna7.cna.org/PopRep/2017/appendixb/b_17.html; and Meridith Hill Thanner, “Military Base Closure Effects on a

Community: The Case of Fort Ritchie Army Garrison and Cascade, Maryland” (PhD dissertation, University of

Maryland, College Park, 2006), 152. This paper uses data from the US Census Bureau and data collected by the author.

68

Supra note 45, at 9.

69

Scott Carrell and Jonathan Zinman, “In Harm’s Way? Payday Loan Access and Military Personnel Performance,”

Review of Financial Studies 27, no. 9 (2014): 2805–40 [hereinafter “Carrell and Zinman (2014)”] at 2806. This paper

uses data from multiple publicly available sources.

Report reviewing research on payday, vehicle title, and high-cost installment loans

Page 17

Although many studies show that lenders of covered loans geographically target minority

communities, some studies show inconclusive results. For example, Neil Bhutta finds that

neighborhood racial composition has little influence on payday lender store locations, conditional on

income, wealth, and demographic characteristics.

70

Creola Johnson explains that another way lenders of covered loans target minorities is through

marketing. “These lenders attract minority borrowers through the use of minority celebrities and

community leaders because many of these prospective borrowers are more likely to obtain a

predatory loan when it is marketed by someone considered trustworthy in their communities.”

71

Payday lenders also target communities of color by hiring minority employees in key positions, such

as store managers or loan officers, to “enable them to easily build rapport within the targeted

community of color.”

72

Johnson notes the example of William Harrod, a whistleblower who testified

to persuade the city council of Washington, D.C., to pass legislation to help curb payday lending.

Johnson notes, “Harrod testified that he was told by management to go to low-income apartment

buildings that were known to be predominantly black and offer the building managers referral fees if

their residents signed up for Check ‘n Go’s payday loans.”

73

Similarly, a former store manager,

Michael Donovan, testified that “[w]e seek out low-income African-American and Latino

neighborhoods [in Washington, D.C.,] because we know that this is where our most profitable client

base is located.”

74

Jim Hawkins reviews payday and vehicle title loan advertisements in Houston, Texas, between

September and October 2014. Hawkins finds that the percentages of pictures with minorities in

storefront and online advertisements in Texas outnumbered the percentage of minorities in the general

population in Texas, and even outnumbered the percentage of minorities among actual users of

payday loans and vehicle title loans. Figure 8 shows the percentages of storefront advertisements with

pictures of minorities in Houston, Texas.

75

70

Neil Bhutta, “Payday Loans and Consumer Financial Health,” Journal of Banking and Finance 47 (2014) [hereinafter

“Bhutta (2014)”]. This study uses data from the Census Bureau and the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

71

Creola Johnson, “The Magic of Group Identity: How Predatory Lenders Use Minorities to Target Communities of

Color,” Georgetown Journal on Poverty Law & Policy, 17, no. 2 (2010): 169. This study uses data from multiple

publicly available sources.

72

Id., at 174.

73

Id., at 175. See also William Harrod, Store Manager, Check ‘n Go, Statement at the Ohio Coalition of Responsible

Lending’s D.C. press conference, Sept. 12, 2007, available at https://kyresponsiblelending.wordpress.com/the-press-

editorials-articles-etc/harrod-testimony-against-check-n-go/. (“We didn’t restrict our marketing to businesses in the

District [of Columbia][,] [w]e went into Maryland, to College Park, Landover, Laurel, Bowie—always to areas with a

high percentage of black customers.”).

74

Michael Donovan, Director of Operations, Check ‘n Go, Statement at the Ohio Coalition of Responsible Lending’s D.C.

press conference, Sept. 12, 2007, available at https://kyresponsiblelending.wordpress.com/the-press-editorials-articles-

etc/statement-of-michael-donovan/.

75

Jim Hawkins, “Are Bigger Companies Better for Low-Income Borrowers? Evidence from Payday and Title Loan

Advertisements,” Journal of Law, Economics, and Policy 303, no. 11 (2015): 325. This paper uses data collected by the

author.

Report reviewing research on payday, vehicle title, and high-cost installment loans

Page 18

Figure 8: Percentages of storefront payday and vehicle title loan advertisements with pictures of

minorities in Houston, Texas

Source: Hawkins (2015).

Report reviewing research on payday, vehicle title, and high-cost installment loans

Page 19

V. Lenders of covered loans charge higher prices in minority

neighborhoods

There is evidence that lenders of covered loans charge higher prices in minority neighborhoods and

near military bases. Robert DeYoung and Ronnie Phillips study the prices of 35,098 payday loans

that originated in Colorado between 2000 and 2006 and find that higher concentrations of African

Americans and Hispanics are associated with small price increases.

76

Quantitatively, the results suggest that a 10% increase in the African American population in a local

market increases the probability of a loan reaching the state rate cap by 1.52% and increases the price

of a loan not yet capped by $0.40. Alternatively, a 10% increase in the Hispanic population in a local

market increases the probability of a loan reaching the state rate cap by about 1% and the price of a

loan not yet capped by $0.28.

77

The authors point out that these results are consistent with payday lenders charging higher rates for

borrowers who have fewer other options to meet their financial needs (i.e., third-degree price

discrimination) but that they are also “consistent with race-based price discrimination.”

78

They also

find that payday loan stores located within a 10-mile radius of military bases charged higher prices on

average: these loans were 2.22% more likely to be priced at the state rate cap and, when priced below

the cap, were priced $0.69 more expensive.

79

Although rates on payday loans in neighborhoods with higher concentrations of African Americans

are higher in the study discussed above, there is evidence that profitability per payday loan does not

significantly differ across geographic locations with different demographics. Mark Flannery and

Katherine Samolyk find that, after adjusting for dollar loan volume, neither the income level nor the

proportion of African Americans in the neighborhoods where stores are located has significant effects

on loan losses, total operating costs, or profitability. Their analysis also does not indicate that repeat

borrowers are more profitable than infrequent borrowers are on a per loan basis. However, the study

emphasizes that high-frequency borrowers do generate profits by contributing to loan volume.

80

Several studies also document price discrimination against minorities in traditional banking and

mortgage lending. Such discrimination manifests itself in higher costs for African Americans,

76

Robert DeYoung and Ronnie Phillips, “Payday Loan Pricing” (working paper, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City,

2009). This study uses data from the Colorado Office of the Attorney General.

77

Id., at 21.

78

Id.

79

Id., at 21–22.

80

Mark Flannery and Katherine Samolyk, “Payday Lending: Do the Costs Justify the Price?” (working paper no. 2005-09,

FDIC Center for Financial Research, 2005). This study uses proprietary, store-level data provided by two payday firms

operating in 22 states.

Report reviewing research on payday, vehicle title, and high-cost installment loans

Page 20

Hispanics, and minorities in general to open and maintain a bank account or to take out a mortgage,

as well as in lower quality of financial services, such as a lower response rate to inquiries and a higher

incidence of mis-selling, fraud, and poor customer service by retail banks.

81

According the 2017 FDIC Survey of Unbanked or Underbanked Households, the unbanked and

underbanked rates were higher among African American and Hispanic households than among white

households. The survey shows that the top reasons people choose not to use banking services offered

by banks are that (1) they do not have enough money to maintain bank accounts and (2) they do not

trust banks.

82

Kevin Connor and Matthew Skomarovsky find from SEC filings that major banks

provided financing to lenders of covered loans through various credit agreements, including revolving

lines of credit and term loans, which lenders of covered loans rely on to fund their operations.

83

As shown in Figure 9, in a 2015 study Ping Cheng and co-authors analyze data from the Survey of

Consumer Finances and find that African Americans, on average, pay a higher interest rate on

mortgages than the general population does. Further regression analyses find that, even after

controlling for a variety of mortgage and borrower characteristics, African American borrowers pay

on average 29 basis points

84

more than comparable white borrowers do, a difference that is both

statistically and economically significant.

85

81

See, e.g., Harold Black, Robert Schweitzer and Lewis Mandell, “Discrimination in Mortgage Lending,” American

Economic Review 68, no. 2 (1978): 186–91, which uses data from the FDIC; Andra Ghent, Ruben Hernandez-Murillo,

and Michael Owyang, “Differences in Subprime Loan Pricing Across Races and Neighborhoods” (working paper,

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, 2014), which uses data from the Federal Reserve; Patrick Bayer, Fernando Ferreira,

and Stephen Ross, “Race, Ethnicity, and High-Cost Mortgage Lending” (working paper, Human Capital and Economic

Opportunity Global Working Group, 2014), which uses data from multiple public and private sources; Ping Cheng,

Zhenguo Lin, and Yingchun Liu, “Racial Discrepancy in Mortgage Interest Rates,” Journal of Real Estate Finance and

Economics 51, no. 1 (2015) [hereinafter “Cheng et al. (2015)”], which uses data from the Survey of Consumer Finances;

Andrew Hanson, Zackary Hawley, Hal Martin, and Bo Liu, “Discrimination in Mortgage Lending: Evidence from a

Correspondence Experiment,” Journal of Urban Economics 92 (2016): 48–65, which uses data from a correspondence

experiment conducted by the authors; Taylor Begley and Amiyatosh Purnanandam, “Color and Credit: Race,

Regulation, and the Quality of Financial Services” (SSRN working paper, 2018), available at

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2939923, which uses data from the CFPB; Andreas Fuster, Paul

Goldsmith-Pinkham, Tarun Ramadorai, and Ansgar Walther, “Predictably Unequal? The Effects of Machine Learning

on Credit Markets” (SSRN working paper, 2018), available at

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3072038, which uses both publicly available and private mortgage

data; Robert Bartlett, Adair Morse, Richard Stanton, and Nancy Wallace, “Consumer-Lending Discrimination in the Era

of FinTech” (working paper, UC Berkeley, Oct. 2018), available at

https://faculty.haas.berkeley.edu/morse/research/papers/discrim.pdf, which uses data from multiple publicly available

sources; and Jacob Faber and Terri Friedline, “The Racialized Costs of Banking,” New America, June 21, 2018,

available at https://www.newamerica.org/family-centered-social-policy/reports/racialized-costs-banking, which uses

data from multiple publicly available sources and proprietary business listing data.

82

FDIC (2018), 3–4.

83

Kevin Connor and Matthew Skomarovsky, “The Predators’ Creditors: How the Biggest Banks are Bankrolling the

Payday Loan Industry,” Public Accountability Initiative, Sept. 4, 2010, available at https://public-

accountability.org/report/the-predators-creditors/. This paper uses data from multiple publicly available sources.

84

Basis point is a unit of measurement for interest rates, yields, and other percentages in finance. A basis point is one-

hundredth of 1%, or 0.01%, or 0.0001. See, e.g., Bruce Tuckman, Fixed Income Securities, Tools for Today’s Markets,

2nd ed. (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2002), 50.

85

Cheng et al. (2015), 112.

Report reviewing research on payday, vehicle title, and high-cost installment loans

Page 21

Figure 9: African Americans pay on average higher rates on mortgages

Source: Cheng et al. (2015).

Report reviewing research on payday, vehicle title, and high-cost installment loans

Page 22

VI. Borrowers of covered loans may not understand the loan

terms or the risks associated with the loan

A number of studies show that borrowers of covered loans may not understand the loan terms and the

risks of prolonged indebtedness associated with taking out a covered loan. These studies show that

lenders of covered loans often do not comply with information disclosure laws and regulations, or

that borrowers of covered loans tend to have low financial literacy and be overly optimistic or

impatient about their future income.

Annamaria Lusardi and Olivia Mitchell find that financial illiteracy is widespread among younger

(under age 35), older (older than age 65), and less-educated populations. In particular, African

Americans and Hispanics display the lowest level of financial literacy among racial and ethnic

groups. Individuals who are financially illiterate are less likely to make long-term plans and

accumulate wealth.

86

Jim Hawkins reviews pictures of payday and title loan advertisements in Houston, Texas, between

September and October 2014, and he finds that many lenders did not comply with Texas regulations.

Texas regulations require payday lending storefronts to disclose (1) the name and address of the

Texas Office of Consumer Credit Commissioner, (2) the notice that loans are intended to be short

term, and (3) the rate schedule and three to five examples of common loans. Hawkins finds that 20%–

30% of payday websites and 10%–40% of storefront payday advertisements do not comply with those

regulations.

87

In a 2016 study, Hawkins finds evidence of behavioral market failure in the advertisements of prices.

Many credit products have teaser periods, that is, an initial period in a loan during which the interest

rates are set at a lower level than the rates applicable for the remaining period of the loan.

88

Hawkins

finds that more than 15% of payday and title loan storefronts advertise loans with teaser rates, and

that more than 17% of payday and title loan websites advertise loans with teaser rates.

89

He argues

that the prevalence of teaser rates in payday and title loan advertisements indicates that borrowers are

overly optimistic and impatient.

90

The study also indicates that payday and title lenders tailor their

86

See Annamaria Lusardi and Olivia Mitchell, “Financial Literacy and Planning: Implications for Retirement Wellbeing”

(NBER Working Paper 17078, Cambridge, MA, 2011); Annamaria Lusardi and Olivia Mitchell, “Financial Literacy and

Retirement Planning in the United States,” Journal of Pension Economics and Finance 10, no. 4 (2011): 509–25; and

Annamaria Lusardi and Peter Tufano, “Debt Literacy, Financial Experiences, and Over-Indebtedness,” Journal of

Pension Economics and Finance 14, no. 4 (2015): 332–68. These papers use survey data collected by the authors.

87

Supra note 75, at 311–12.

88

See, e.g., Brian P. Lancaster, Glenn M. Schultz, and Frank J. Fabozzi, Structured Products and Related Credit

Derivatives: A Comprehensive Guide for Investors (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2008), 81–83.

89

Jim Hawkins, “Using Advertisements to Diagnose Behavioral Market Failure in the Payday Lending Market,” Wake

Forest Law Review 59 (2016): 71. This paper uses advertising data collected by the author.

90

Id., at 91.

Report reviewing research on payday, vehicle title, and high-cost installment loans

Page 23

advertisements to appeal to overly optimistic and impatient borrowers. If borrowers were rational, the

majority would have taken advantage of the cheap teaser rate and repaid at the end of the teaser

period. However, most consumers do not pay off their loans quickly.

In a different survey study, Ronald Mann finds that about 60% of borrowers are able to predict

accurately the length of their indebtedness after taking out a payday loan.

91

However, based on the

prevalence of teaser rates, Hawkins concludes that

[e]ven if Mann is correct that some borrowers can accurately guess how long they

will keep out their loans, teaser rates lack a rational choice explanation. [Assuming

Mann is correct, the teaser periods] are short-term price cuts for borrowers who

believe they will have the product long term. [This adds] another layer of evidence

that firms believe that at least some borrowers are overly optimistic or overly fixated

on initial pricing and will be enticed into taking out loans and keeping them out for

longer periods of time. The presence and prevalence of teaser rates indicate that some

payday and title lending borrowers are not acting rationally.

92

Marianne Bertrand and Adair Morse conduct a field experiment and a phone survey and find evidence

that borrowers may have chosen payday loans based on incomplete or miscomprehended information.

The field experiment finds that showing comparisons between the accumulated fees associated with

repeated payday borrowing versus the comparable cost of credit card debt is most effective in

reducing the usage of payday borrowing. A one-time intervention (providing information on the

accumulation of fees to a consumer) reduces the probability of taking out a payday loan during the

following four months by about 11%.

93

In its 2017 Final Rule, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) notes the result from this

field experiment and states that the disclosures of risks and costs of reborrowing have “a marginal

91

Ronald Mann, “Assessing the Optimism of Payday Loan Borrowers,” Supreme Court Economic Review 21, no. 1

(2015): 105–32. The survey was conducted with the cooperation of a single payday lender making loans in five states

and was administered at a limited number of locations. In this survey, participants were asked: “We’d like to understand

more about your overall financial picture. How long do you think it will be before you have saved enough money to go

an entire pay period without borrowing from this lender? If you aren’t sure, please give your best estimate.” The survey

result shows that (1) 57% of borrowers are generally accurate (within a 14-day window) in their predictions, (2) 40%

borrowers anticipated they would continue their borrowing after its original due date, and (3) borrowers were about as

likely to overestimate their times in debt as they were to underestimate them. In its 2017 Final Rule, the CFPB reviewed

the data that Mann studied and concluded that “the data … provide strong evidence that these borrowers who experience

long periods of indebtedness did not anticipate those experiences[,] . . . that even short-term borrowers do not fully

expect the outcomes they realize[,] . . . and that regardless of whether borrowers experienced short or long durations of

indebtedness, they did not systematically predict their outcomes with any sort of accuracy or precision.” See 2017 Final

Rule, at 54816–17.

92

Supra note 89, at 92.

93

Marianne Bertrand and Adair Morse, “Information Disclosure, Cognitive Biases, and Payday Borrowing,” Journal of

Finance 66, no. 6 (2011): 1865–93 [hereinafter “Bertrand and Morse (2011)”]. This paper uses survey data collected by

the authors in conjunction with payday lending stores.

Report reviewing research on payday, vehicle title, and high-cost installment loans

Page 24

effect on the total volume of payday borrowing.”

94

Adding to this study, the CFPB analyzes similar

disclosures implemented by the State of Texas and finds “a reduction in loan volume of 13 percent

after the disclosure requirement went into effect, relative to the loan volume changes for the study

period in comparison States.”

95

However, the CFPB’s analysis shows that “the probability of re-

borrowing on a payday loan declined by only approximately two percent once the disclosure was put

in place.”

96

The CFPB concludes in its 2017 Final Rule that disclosure requirements have limited

effects and that “the core harms to consumers in this credit market remain even after a disclosure

regime is put in place.”

97

In addition, Bertrand and Morse conduct a follow-up phone survey with consenting participants of the

experiment to ask questions concerning how individual borrowers understand the terms and the

finance of their borrowing. They ask participants three questions:

1. “To the best of your knowledge, what is the annual percentage rate, or APR, on the typical

payday loan in your area?”

2. “To the best of your knowledge, how much does it cost in fees to borrow $300 for three months

from a typical payday lender in your area?”

3. “What’s your best guess of how long it takes the average person to pay back in full a $300

payday loan? Please answer in weeks.”

The survey results reveal that many borrowers think the annual APR is the dollar cost per hundred

they borrow, and that most borrowers answer that the total cost of a three-month payday loan is the

fee associated with one loan cycle. The mean answer to the debt duration question is about five to

six weeks, but the most common answer is one cycle (two weeks). While the authors note the low

response rate of the phone survey, they emphasize that the results provide general information on the

relevance of cognitive miscomprehension of payday loan borrowers.

98

In its 2017 Final Rule, the CFPB makes three points regarding the phone survey results. First, due to

the way the question was asked, it is “difficult to be certain that some survey respondents did not

conflate the time during which the loans are outstanding with the contract term of individual loans.”

99

Second, “[p]eople’s beliefs about their own re-borrowing behavior could also vary from their beliefs

about average borrowing behavior by others.”

100

Finally, “[t]his study also did not specifically

94

2017 Final Rule, at 54852.

95

Id., at 54577.

96

Id., at 54577–626.

97

Id., at 54578.

98

Bertrand and Morse (2011): 1876–78.

99

2017 Final Rule, at 54568.

100

Id.

Report reviewing research on payday, vehicle title, and high-cost installment loans

Page 25

distinguish other borrowers from the subset of borrowers who end up in extended loan sequences.”

101

The CFPB concludes in the 2017 Final Rule that this survey is “only informative about how accurate

borrowers’ predictions are about the average.”

102

101

Id.

102

Id.

Report reviewing research on payday, vehicle title, and high-cost installment loans

Page 26

VII. Access to covered loans can have negative impacts on

consumers

In addition to the risk of prolonged indebtedness that consumers may not be fully aware of, studies

have shown that, in general, access to covered loans can be associated with many negative outcomes.

Negative effects from access to payday loans on military personnel include reduced readiness and

performance.

103

Scott Carrell and Jonathan Zinman track the performance of enlisted Air Force

personnel and their assignments to bases in different states with various level of access to payday

lending. They find that the job performance and retention of airmen declines with payday loan access,

and severely poor readiness increases.

104

Negative outcomes for civilian borrowers of covered loans include increased financial fragility and

borrower delinquency, inability to pay important bills and prioritize other liabilities (e.g., child

support payments), and the loss of transportation due to vehicle repossession.

105

Sumit Agarwal and

co-authors study the relationship between successful applications for payday loans and defaults on

credit cards in the following year. Even after controlling for variables capturing concurrent and

historical individual credit standing, the usage of payday loans still predicts nearly a doubling in the

probability of being 90 days past due on credit card debt during the following year.

106

103

See, e.g., Carrell and Zinman (2014).

104

Carrell and Zinman (2014).

105

See, e.g., Sumit Agarwal, Paige Marta Skiba, and Jeremy Tobacman, “Payday Loans and Credit Cards: New Liquidity

and Credit Scoring Puzzles?” American Economic Review: Papers and Proceedings 99, no. 3 (2009) [hereinafter

“Agarwal et al. (2009)”], which uses data from a large payday lender; Bart Wilson, David Findlay, James Meehan,

Charissa Wellford, Karl Schurter, “An Experimental Analysis of the Demand for Payday Loans,” B.E. Journal of

Economic Analysis and Policy 10 (2010) [hereinafter “Wilson et al. (2010)”], which uses experimental data collected by

the authors, on the negative effect of extensive usage of payday loans; Brian Melzer, “The Real Costs of Credit Access:

Evidence from the Payday Lending Market,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 126 (2011): 517–55 [hereinafter “Melzer

(2011)”], which uses data from multiple publicly available sources; Dennis Campbell, Asis Martinez-Jerez, and Peter

Tufano, “Bouncing Out of the Banking System: An Empirical Analysis of Involuntary Bank Account Closures,” Journal

of Banking and Finance 36, no. 4 (2012): 1224–35, which uses data from multiple publicly available sources; Nathalie

Martin and Ozymandias Adams, “Grand Theft Auto Loans: Repossession and Demographic Realities in Title Lending”

(working paper, University of New Mexico School of Law Legal Studies Research Paper Series, 2012), which uses data

from multiple publicly available sources; Jean Ann Fox, Tom Feltner, Delvin Davis, and Uriah King, “Driven to

Disaster: Car-Title Lending and Its Impact on Consumers” (Center for Responsible Lending, Feb. 28, 2013), available

at https://www.responsiblelending.org/research-publication/driven-disaster, which uses private data from a payday

lender as well as data from multiple state-level regulators; Brian Melzer, “Spillovers from Costly Credit,” Review of

Financial Studies 31, no. 9 (2018): 3568–94, which uses data from multiple publicly available data sources; Paige Marta

Skiba and Jeremy Tobacman, “Do Payday Loans Cause Bankruptcy?” (working paper, Vanderbilt Law and Economics

Research Papers, Nashville, TN, 2011), which uses private data from a payday lender; and John Gathergood, Benedict

Guttman-Kenney, and Stefan Hunt, “How Do Payday Loans Affect Borrowers? Evidence from the U.K. Market,”

Review of Financial Studies 32, no. 2 (2019), which uses publicly available data from the UK.

106

Agarwal et al. (2009).

Report reviewing research on payday, vehicle title, and high-cost installment loans

Page 27

Brian Melzer utilizes the exogenous variation in the travel distance for consumers from a state that

prohibits payday loans to payday stores across state borders to gauge the impact of having access to

payday lending. The study finds that having access to payday credit (less than 25 miles of travel to a

payday-allowing state) increases the likelihood of family hardship by 5 percentage points relative to

areas without payday credit access. The likelihood of postponing health care also increases by 4.5

percentage points in areas with access to payday credit relative to areas without.

107

Suparna Bhaskaran, with the cooperation of three community organizations, conducts a survey with

771 women to identify women’s experience in subprime home mortgages loans, payday loans, and

student loans.

108

According to the survey response, when asked about the ways that high-cost debt is

affecting their personal life and their family, 47% responded that they were unable to save money,

20% responded that they could not afford health care, 19% responded that they had to delay

purchasing a car, and 18% responded that they had difficulty affording adequate food.

109

When asked

about their experience after taking out high-cost debt, 25% responded that their credit score went

down.

110

Studies find that access to covered loans also has negative implications on consumer wellness.

111

Elizabeth Sweet and co-authors find that usage of fringe loans is associated with poor health

conditions such as high blood pressure and anxiety.

112

Jaeyoon Lee finds that gaining access to payday loans significantly increases the number of suicide

attempts by about 10% (equivalent to 5.2 additional attempts per 100,000 people), potentially due to

mental health deterioration from financial distress.

113

The increase is particularly high for African

107

Melzer (2011).

108

Suparna Bhaskaran, “Pinklining—How Wall Street’s Predatory Products Pillage Women’s Wealth, Opportunities, and

Futures,” New Jersey Communities United, ACCE Institute, and ISAIAH, June 2016, available at

https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/acceinstitute/pages/100/attachments/original/1466121052/acce_pinklining_VIE

W.pdf?1466121052. See the report for more details on the New Jersey Communities United, ACCE Institute, and

ISAIAH.

109

Id., at 24. The author notes that the “intent [of the survey] was not to achieve a random or representative sample, but to

reach and survey women in the communities where these organizations work, and identify women’s experiences and

overall trends.”

110

Id., at 25.

111

See, e.g., Elizabeth Sweet, Christopher Kuzawa, and Thomas McDade, “Short-Term Lending: Payday Loans as Risk

Factors for Anxiety, Inflammation and Poor Health,” SSM-Population Health 5 (2018): 114–21 [hereinafter “Sweet et

al. (2018)”]; Jerzy Eisenberg-Guyot, Caislin Firth, Marieka Klawitter, and Anjum Hajat, “From Payday Loans to

Pawnshops: Fringe Banking, the Unbanked, and Health,” Health Affairs 37, no. 3 (2018): 429–37 [hereinafter

“Eisenberg-Guyot et al. (2018)”]; and Jaeyoon Lee, “Credit Access and Household Well-Being: Evidence from Payday

Lending” (working paper, Fudan University, 2019) [hereinafter “Lee (2019)”]. Sweet et al. (2018) use data collected by

the authors. Eisenberg-Guyot et al. (2018) and Lee (2019) use data from multiple publicly available sources.

112

Sweet et al. (2018).

113

Lee (2019), 39.

Report reviewing research on payday, vehicle title, and high-cost installment loans

Page 28

Americans younger than 65—gaining access to payday loans increases suicide attempts by 15.5%

(equivalent to 7.1 additional attempts per 100,000 people).

114

Jerzy Eisenberg-Guyot and co-authors found that fringe borrowing, defined as usage of payday,

pawn, or car-title loans, is associated with a 38% higher prevalence of poor or fair health and that

being unbanked is associated with a 17% higher prevalence or poor or fair health.

115

Their study

states, “[E]xpanding social welfare programs and labor protections could potentially address the root

causes of the use of fringe services and advance health equity.”

116

Indeed, Heidi Allen and co-authors,

as an example, find that the early Medicaid expansion in California was associated with an 11%

reduction in the number of payday loans taken out each month, as well as a reduced number of unique

borrowers and amount of payday loan debt.

117

Last, a few studies find payday lending to be associated with several neutral outcomes, such as having

little to zero immediate effect on consumers’ credit scores and other measures of financial well-being,

and insignificant changes in bankruptcy filings.

118