CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU | SEPTEMBER 2023

Tuition Payment Plans

in

Higher Education

Table of contents

Executive summary ..................................................................................2

1. Market overview .................................................................................. 6

1.1 Direct lending by colleges.....................................................................................6

1.1.1 Colleges as lenders................................................................................................. 6

1.1.2 Loan amounts...................................................................................................... 10

1.1.3 Plan terms and number of installments.................................................................. 11

1.1.4 Fee structures .......................................................................................................12

1.1.5 Contract terms......................................................................................................14

1.2 Third-party private installment loans ...............................................................15

2. Consumer risks................................................................................. 17

2.1 Inconsistent disclosures......................................................................................17

2.2 Automatic enrollments and forced use.............................................................20

2.3 High costs related to late payment....................................................................23

2.4 College debt collection practices.......................................................................27

2.5 Waivers of consumer rights...............................................................................29

3. Conclusion........................................................................................ 31

Appendix A: Tuition payment plan dataset methodology and

descriptive statistics .........................................................................32

A.1 Methodology......................................................................................................32

A.1.1 Sample construction............................................................................................... 32

A.1.2 Variables................................................................................................................ 32

A.2 Descriptive statistics .........................................................................................33

Appendix B: Glossary...........................................................................34

CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU 1

Executive summary

Many Americans have their first experiences with lending, debt collection, and credit reporting

while in college. While federal student loans from the U.S. Department of Education and private

financial institutions are the major ways in which students borrow, this report examines a

financial product that is less familiar to many students and families: a tuition payment plan.

Many colleges allow students to pay for postsecondary education in installments using tuition

payment plans. When colleges do so, they allow students to obtain their education now and pay

for it over time; in other words, they become lenders. While tuition payment plans are generally

marketed as alternatives to loans, many tuition payment plans should be understood as at a type

of loan. Typically, these plans allow students to spread the cost of tuition and other educational

expenses across several payments over the course of a single semester or term.

These tuition

payment plans vary and may be paid in as few as two to four installments or in many

installments stretching beyond the length of one year.

Products marketed as tuition payment plans have a wide range of product structures. School-

provided payment plans may be managed by the schools or administered by third-party

payment processors (e.g., Nelnet, Transact, or TouchNet). Typically, tuition payment plans are

interest-free, but colleges (along with the third-party service providers that facilitate payments)

commonly charge enrollment fees, late fees, and returned payment fees.

This report builds on the CFPB’s recent work including a report on deposit and credit products

offered by colleges or in college settings;

1

recent supervisory examinations of institutional

student lenders;

2

publications on buy now, pay later (BNPL) products;

3

and other work on

products offered by trusted intermediaries.

4

The wide variation in terms that are offered by tuition payment plans, and the terminology that

schools use to describe them, may confuse consumers about the nature of the financial

1

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, College Banking and Credit Card Agreements: Annual Report to Congress,

(Oct. 2022), https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/cfpb_college-banki ng-report_2022.pdf.

2

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Supervisory Highlights: Student Loan Servicing Special Edition Issue 27,

Fall 2022, (Sep. 2022), https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/cfpb_student-loan-servicing-s upervis ory-highlights-

special-edition_report_2022-09 .pdf.

3

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Buy Now, Pay Later: Market Trends and Consumer Impacts, (Sep. 2022),

https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/cfpb_buy-now-pay-l ater-market-trends-consumer-

impacts_report_2022-09.pdf.

4

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, (May 2023), Data Point: Pitfalls of Medical Credit Cards and Financing

Plans, https://www.consumerfinance.gov/data-research/research-reports/medical-credit-card s-and-financing-

plans/.

CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU 2

arrangement they are entering into. For instance, some schools market tuition payment plans as

an alternative to student loans.

5

Further, information about fee levels and terms are often

spread across several different documents and/or webpages, which may make it difficult for

consumers to find complete information. Overall, these practices could obscure the nature of the

product, the cost of credit, and what entity owns or services the product.

6

And because tuition

payment plans are often offered to students by their schools after they have already enrolled, the

circumstances might result in a captive market in which students may not be able compare the

products to other options.

To assess the types of installment loan plans that are offered directly by colleges, the CFPB

performed a review of nearly 450 college websites to gather publicly available data on tuition

payment plans and related contracts.

7

In addition to the review of school and program websites

and contracts, the CFPB analyzed consumer complaints, met with industry participants, and

conducted interviews with current consumers.

8

Findings include:

• Almost all colleges offer some sort of tuition payment plan, and millions of

students use this product each year: Existing research suggests that as many as

98 percent of colleges offer tuition payment plans,

9

and the CFPB estimates that up to

3.9 million borrowers might use them each term.

10

5

While some tuitionpayment plans are marketed this way, many tuition payment plans are consideredprivate

student loans under the Truth in Lending Act (TILA), although whether and how different disclosure regulatory

requirements may apply depend on each tuition payment plan’s individual features. See section 2.1. See, e.g., Transact

Holdings Inc., 2022, Payment Plans: An alternative to student loans,

https://transactcampus.com/resources/infographics/request/an-easier-way-to-p roce ss-payment-plans

. Accessed

January 11, 2023.

6

In interviews conducted in March 2023 with current students, the CFPB observed that some students did not

understand that some tuition payment pl ans could be forms of credit, and some did not understand thatthe tuition

payment plan they were using was offered by theirschool and not by the federal government. Others thought that a

tuition payment plan was simply a plan to repay their federal student loan debt.

7

Data collection occurred from December 2022 to April 2023. This report presents new data and analysis to build

upon the analysis conducted for the CFPB’s 2022 college banking report. For more information on that report, see

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, College Banking and Credit Card Agreements: Annual Report to Congress,

(Oct. 2022), https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/cfpb_college-banki ng-report_2022.pdf

.

8

Id.

9

The National Association of College and University Business Officers (NACUBO) estimated that 98 percent of

public and private non-profit col leges offer tuition payment plans. This estimate is based on a survey conducted

between October and December 2019 and included data from 454 public and private nonprofit colleges and

universities. NACUBO, 2019 Student Financial Services Policies and Procedures Report

.

10

CFPB estimates that 20 to 25 percent of students use payment plans at schools that offer them b ased on d i scu ssions

with market participants. Based on this utilization rate estimate, NACUBO’s estimate of the percent of colleges

offering TPPs (see supra note 10), and total undergraduate e nrollment (at schools participating in the Title IVfederal

aid program)data from College Scorecard, the CFPBestimates that 2.9 to 3.9 million students use a payment plan

each term. U.S. Dep’t of Education, (Sep. 14, 2022), College Scorecard, https://collegescorecard.ed.gov/data

. Data

used for this analysis was last updated in September 2022 and reflects enrollment totals from Fall 2020.

CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU 3

• The CFPB observed varied and sometimes inconsistent disclosure of t erms

and conditions: Unlike traditional private education loans, which are subject to a

common set of disclosure requirements stipulated under federal law,

11

disclosures of

tuition payment plan terms and conditions can vary widely. In part, this may be

because the tuition payment plan label can encompass a wide range of product

structures, and the plans may differ with regard to the duration of the contract and the

number of payments required, in addition to other terms, which may impact a school’s

disclosure obligations. In other cases, similarly structured products are disclosed

differently.

• The CFPB observed terms and conditions that may allow automatic

enrollments and forced use: In some cases, borrowers may become enrolled in a

tuition payment plan without knowingly signing up for one or because institutional

disbursement practices of students’ federal student loan funds may create a situation

where a student is unable to meet the school’s tuition deadlines without enrolling in a

payment plan.

12

When these situations occur, the use of the product could lead to fees

and financial difficulties for students.

• Some colleges may impose high costs when students miss payments: Based

on the fees in the tuition payment plans reviewed by the CFPB, the average amount of

a late payment fee is $30. However, it appears that in some cases, late fees can be over

$100 per missed payment, and in other cases, some colleges may charge late and

returned payment fees on the same transaction. The CFPB also observed terms that

may allow colleges to convert no-interest payment plans into interest-bearing loans

when payments are missed.

13

These practices can lead to a high cost for late payment

on tuition payment plans.

11

See 12 CFR §§ 1026.46-48; 34 CFR part 601. Generally, private student loan disclosure requirements can cover

arrangements that schools label as “tuition payment plans” if the arrangements meet the definition of “private

education loan” under 12 CFR 1026.46(b)(5). However, there is an exception to those requirements for such plans

that do not charge interest and the term of the extension of credit is one year or less. See id. Even if the exception

applies to a specific tuition payment plan, though, the plan may still be subject to other disclosure requirements for

closed-end credit, as also discussed in Section 2.1.

12

See, e.g., Arizona State University, Tuition and Aid Webpage (accessed Apr. 23, 2023),

https://tuition.asu.edu/billing-finances/payment-plan#we bsp ark-anchor-li nk--19. This website states that “If you

have outstanding charges of $500 or more after the payment deadline, you’ll be automatically enrolled in the ASU

Payment Plan and be billed an ASU Payment Plan fee [of $100 for resident students or $200 for nonresident

students].” See also, e.g., Oklahoma Community College, Bursar Webpage, (accessed Jan. 11, 2023),

https://www.occc.edu/bursar/. This website states that “If you miss your designated due date for an in-full payment, we’ll

automatically place you on a monthly payment plan that lets you pay off your tuition and fees over time. The payment

plan incurs a $25 set-up fee per term.”

13

See, e.g., Franklin University, Tuition Payment Plans & Options Webpage, (accessed Apr. 23, 2023),

https://www.franklin.edu/tuition-financial-aid/payment-options. This website states that “There is a 7 day grace

period for all balances; thereafter past due balances are subject to an 18% APR finance charge.”

CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU 4

• At least one in three colleges reserve the right to withhold transcripts as a

debt collection practice, and students may be subject to other intrusive

forms of debt collection: Once an unpaid balance is sent to collections, the

borrower may become subject to transcript withholding, which under certain

circumstances the CFPB has found to be an abusive act or practice.

14

Additionally, in

some cases, students could risk removal from classes, meal plans, and campus housing

when they miss a payment on a tuition payment plan.

15

In some cases, these

consequences may be more severe than students might face if they used a different

option to cover tuition, such as a federal student loan, a private student loan, or even

general-purpose financial products like credit cards.

16

• Some contracts and agreements purport to waive certain consumer rights:

Some contracts and agreements related to student financial obligations, including

tuition payment plan contracts as well as enrollment and student financial

responsibility agreements, include terms and conditions that purport to waive

consumers’ legal protections or limit how consumers can enforce their rights. In some

cases, important terms and conditions may be included in contracts that are signed

only once when a student initially enrolls in the school and may not be re-disclosed at

the point-of-enrollment for the payment plan.

14

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Supervisory Highlights: Student Loan Servicing Special Edition Issue 27,

Fall 2022, (Sep. 2022), https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/cfpb_student-loan-servicing-s upervis ory-highlights-

special-edition_report_2022-09.pdf, at 8.

15

See, e.g., Rivier University, Payment Policies Webpage, (accessed May 25, 2023),

https://www.rivier.edu/financial-aid/student-resources/payment-policies/. This webpage states that students who

pay late may be subject to a late payment penalty, the accrual of interest on unpaid balances, deactivation of their

campus ID cards, residence hall dismissal, suspension of meal plan, suspension of participation with athletic teams,

and more.

16

The CFPB recommends that students consider federal student loans first and does not recommend that consumers

use credit cards to pay for college. It can be a much more expensive way to finance an education and credi t cards do

not provide the flexible repayment terms or borrower protections offered by federal student loans. See, e.g.,

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Paying for College: Choose a loan that’s right for you, (accessed Aug. 27,

2023), https://www.consumerfinance.gov/paying-for-college/choose-a-student-loan/

.

CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU 5

1. Market overview

This market overview is based on a mixed-methods analysis that uses both quantitative and

qualitative data. The CFPB collected and analyzed publicly available information on tuition

payment plans from nearly 450 college websites during the period from December 2022

through April 2023. The sample used in this report is the same sample of colleges used in the

CFPB’s 2022 college banking report,

17

and all quantitative analysis in this report is based on this

data, unless otherwise noted. To add a qualitative overlay to our data analysis, we also reviewed

consumer complaints submitted to the CFPB and the Department of Education (ED), met with

industry participants, and conducted interviews with consumers using tuition payment plans.

1.1 Direct lending by colleges

While tuition payment plans offered by colleges differ in structure across schools, they tend to

have a number of similar features. This section explores features including average loan

amounts, plan length and number of installments, fee structures, and contract terms.

1.1.1 Colleges as lenders

Many colleges allow students to pay for postsecondary education in installments using tuition

payment plans. When colleges do so, they allow students to obtain their education now and pay

for it over time; in other words, they become lenders.

18

While tuition payment plans are

generally marketed as alternatives to loans, many tuition payment plans should be understood

as at a type of loan. These plans may help students pay tuition out of pocket or bridge the gap

between the financial aid they have been offered and the total cost of attendance. For colleges,

these plans may boost enrollment and generate income.

19

In the 2022-2023 academic year, we found that roughly nine in ten schools in our sample that

participate in the federal student aid program (referred to here as “Title IV” schools) appeared

to offer tuition payment plans to their students, meaning that the school allows the tuition bill to

be deferred and the student to pay the bill in installments.

20

Other estimates, including one

17

Data collection occurred from December 2022 to April 2023. See Appendix A for more information on the

methodology used in this report.

18

See, e.g., 12 U.S.C. § 5481(7).

19

Turner, M.L., “The Payment Plan: Managing and marketing tuition installment plans for the benefit of students,

families, and the institution,” University Business (Oct. 2012).

20

See supra note 18.

CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU 6

based on industry-wide survey data from 2019, suggest that as many as 98 percent of Title-IV

schools offer payment plans.

21

Using this industry estimate and undergraduate enrollment data,

the CFPB estimates that as many 2.9 to 3.9 million students use a payment plan each academic

term.

22

Over 60 percent of the schools offering installment products appear to outsource some functions

to third-party financial service providers.

23

Among this group, three large service providers

appear to administer almost all of the plans: Nelnet, Transact, and TouchNet (Figure 1). These

companies primarily provide software that allows schools to embed tuition payment plan

processing functionality into existing systems such as online “student portals” – and in some

cases, they also provide payment processing services via a partner bank, such as Wells Fargo and

U.S. Bank.

24

In some cases, third-party providers may also offer to fulfill certain compliance

responsibilities on behalf of the university.

25

While some schools provide information to

students about the third parties involved in their tuition payment plans,

26

others may not use

third parties or not disclose these arrangements to students.

27

21

National Association of College and University Business Officers(NACUBO), 2019 Student Financial Services

Policies and Procedures Report, https://www.nacubo.org/research/sfs%20benchmarking%20report, at 7.

22

See supra note 11.

23

This appears to be consistent with NACUBO’s 2019 survey findings (b ased on a survey conducted between October

and December 2019including data from 454 publ ic and private nonprofit col leges and universiti es). See supra note

22.

24

Three out of the four largestservice providers are structured as independent sales organizations, or ISOs (Nelnet),

or subsidiaries of ISOs (TouchNet and Transact). ISOs provide front-end, customized services to a client population

(e.g., payments software to colleges and universities, etc.) and sell their partner bank’s merchant accounts, through

which the client would set up their payment flow. This benefits the partner bank by bringing additional payments

through the bank that can generate revenue (e.g., acquirer mark-up fees or ACH transaction fees). Where TPP third-

party service providers are subsidiaries of ISOs, the third-party provider may not require theschool to use that ISO or

partner bank for payment processing. The other large service provider, Flywire, is not an ISO – and in cases where it

processes payments, it does so via its own merchant account at a bank.

25

See supra note 20. See also, e.g., TouchNet, Compliance Webpage, (accessed Aug. 27, 2023),

https://www.touchnet.com/merchant-services/compliance. This website states that “Achieving and maintaining

compliance is a significant undertaking, especially given the size and complexityof today’s campuses and the multiple

payment points, methods, and channels involved. Our U.Commerce software solutions are compliant and built to stay

compliant as standards evolve. By protecting sensitive data, we reduce scope, compliance overhead, and regulatory

paperwork, giving you peace of mind that comes from having a secure, end-to-end compliance solution in place.” See

also, e.g. Nelnet Campus Commerce, Long-Term Payment Plans Webpage, (accessed Aug. 27, 2023),

https://campuscommerce.com/payment-solutions/long-te rm-p ayme nt-p lans/. This website states that “We manage

disclosures so you don’t have to. Maintaining compliance with HEOA and TILA can be costly and time-consuming.

Nelnet relieves this burden from your business office, giving you more time to do what you do best – support student

needs.”

26

See, e.g., Fort State Valley University, Nelnet Payment Plan FAQs, (accessed Apr. 26, 2023),

https://www.fvsu.edu/paymentp lan. See also, e.g., Georgia Southwestern University, Nelnet Payment Plan,

(accessed Apr. 26, 2023), https://www.gsw.edu/student-account/ne lnet-payme nt-plan.

27

Some third-party providers, including TouchNet and Flywire, offer tuition payment plan software as a “white-label”

product, using the col lege’s branding rather than the third-party’s branding. Colleges with these providers may be

more likely to fall into the “No Provider Found / IHE” designation.

CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU 7

FIGURE 1: PROVIDER DISTRIBUTION, FOR SCHOOLS WITH PAYMENT PLANS

Schools were marked as having “No Provider Found / IHE” in cases where the CFPB observed the presence of a

tuition payment plan but could not identify a third-party service provider. In these cases, the school may administer

the plan directly or there may be a service provider that is not publicly identified. The “Small Provider” designation

indicates that a third-party service provider was identified and services two or fewer schools.

Financial relationships between schools and third-party service providers can differ. Schools

typically pay the service provider an annual licensing fee for the use of the software and/or may

also pay fees per transaction if the service provider is involved in the payments flow (Figure 2).

Schools sometimes pay these fees on behalf of their students and other times pass these fees

directly onto the consumers.

28

In some cases, the third-party providers may also receive a

portion of fee revenue, with the school also retaining a portion. The CFPB identified third-party

service providers in its sample that received fee revenue based on enrollment fees,

29

late and

28

Throughout the data collection, the CFPB found that schools typically cover ACH fees but pass along transaction

fees on cards to students.

29

See, e.g., Dutchess Community College, (Apr. 2019), Setting Up a Payment Plan YouTube Tutorial, (accessed Apr.

26, 2023), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K3MGHqLGdmE. This payment plan enrollment tutorial video

noted: “$25 of this [enrollment] fee is retained by Nelnet Campus Commerce for proving the software and support

necessary to administer your plan. The remainder of the fee is remitted to your institution.” See also, e.g., Victor

Valley College, (Jun. 2018), Video Tutorial: How to Set Up Your Payment Plan, (accessed Apr. 26, 2023),

https://www.vvc.edu/fees-refunds.

CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU 8

returned payment fees,

30

and transaction fees.

31

Third-party service providers may also earn

interest on any balances that they hold before remitting to the appropriate school.

32

FIGURE 2: EXAMPLE TUITION PAYMENT PLAN MODEL

30

See, e.g., University of Wisconsin – Stevens Point, Pay My Bill Webpage,

https://www3.uwsp.edu/SFS/Pages/Pay-My-Bill.aspx. This website states that “If you enroll in a payment plan but

you do not mak e i nstallment payments by the due date, you will be sub ject to l ate fees assessed by UW-Stevens Point

and Transact Payments separately.” It also says that if electronic checks are returned, a $25 charge “will be assessed

by Transact Payments [and additionally the payment] by NSF check will be treated as nonpayment of tuition and fees

and a $75.00 administrative fee may be added to your account.”

31

See, e.g., University of Pennsylvania, Penn Payment Plan Webpage, (accessed Apr. 26, 2023),

https://srfs.upenn.edu/billing-payment/penn-payme nt-plan. This website states that: “Our vendor...assesses a 2.85%

convenience fee on credit card payments.”

32

See, e.g., Nelnet, 10-K Annual Report, (Feb. 28, 2023), https://d18rn0p25nwr6d.cloudfront.net/CIK-

0001258602/760b5395-99df-474d-87da-7ba1fc76031d.pdf, at pages 10-11. In 2022, Nelnet reported almost $9.4

million in net interest income on tuition funds held in custody for schools and states that “Nelnet Bank ’s deposits are

interest-beari ng and consist of…intercompany deposits [among other sources].… The intercompany deposits are

deposits from the Company and its subsidiaries…[including] NBS custodial deposits consisting of tuition payments

collected which are subsequently remitted to the appropriate school.”

CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU 9

In certain cases, federal regulations apply when schools recommend financial products to

students, in recognition of the critical role that colleges play as trusted sources of information

for their students.

For instance, when colleges recommend deposit accounts, private student

loans, or credit cards to students, various regulations govern the process to ensure that schools

disclose their financial interests to students.

33

However, these requirements do not apply to all

types of financial products, and some tuition payment plans may fall outside of the scope of

these regulations.

Further, state law can also impact disclosure obligations.

34

1.1.2 Loan amounts

Because colleges and private lenders rarely report publicly on their installment plan portfolios

and because tuition payment plans may be reported differently by different schools, data on

tuition payment plans is limited and the average size of tuition payment plans is unknown.

Available sources of data suggest that the amount students may take on through tuition payment

plans can reach into the thousands of dollars and that the loan amounts can also vary widely.

For instance, the State of California’s Department of Financial Protection & Innovation collects

information from licensed private student loan servicers about state and national retail

installment contract volumes under the state’s Student Loan Servicing Act.

35

According to this

reporting, California’s licensees had over 40,000 retail installment loan contracts in the state

representing almost $215 million outstanding at the end of 2022.

36

Although it is not clear

whether all tuition payment plans reviewed for this report would meet California’s retail

installment loan contract definition, these data indicate that for tuition payment plans meeting

that definition and reported by licensed providers in California, such plans have an average

33

See, e.g., Regulation Z, 12 CFR part 1026, subparts C (regarding closed end credit), F (regarding private student

loans) and G (regarding open-end credit offered to col lege students). See also 34 CFR part 601 (regarding school and

lender requirements for private and federal education loans); id. at 668.164 (disclosures related to certain campus

financial account arrangements). The Truth in Lending Act also prohibits private student loan lenders from directly

or indirectly offering or providing any gift to a school in exchange for any advantage or consideration provided to the

lender related to its private student loan activities and from engaging in revenue sharing with a school. 15 U.S.C.

1650(b).

34

Some states are considering regulations that would explicitly provide that education financing products, including

but not limited to installment contracts, qualify as private student loans under existing state regulations. See note 39.

35

See Cal. Fin. Code § 28100 et seq. The definition of “retail installment contract” is provided at Cal. Civ. Code §

1802.6 (2022). The California Department of Financial Protection and Innovation recently proposed an updated

definition. See, e.g., California Dep’t of Fin. Prot. & Innovation, (Jan. 6, 2023), Proposed Regulations Under the

California Consumer Financial Protection Law, available at

https://dfpi.ca.gov/wp-

content/uploads/sites/337/2023/03/PRO-01-21-TEXT.pdf?emrc=cf5bce.

36

California Department of Financial Protection & Innovation, Annual Report of the Student Loan Ombudsman for

2022, (July 2023), https://dfpi.ca.gov/wp-

content/uploads/sites/337/2023/07/StudentLoanOmbudsman_AnnualReport.pdf, at 26.

10 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

installment loan size of roughly $5,300.

37

However, this data point is limited because it relies on

data submitted only by private education loan servicers licensed in the State of California about

relationships with consumers in the state. It also excludes installment contracts that are serviced

by non-licensed providers such as public schools, products that may not fit the definition of

retail installment loan under California law, and contracts not reported by licensees.

38

Other estimates, based on data sources assessing all debts students owe to their institutions—of

which tuition payment plans can be considered one type—suggest that the average amount could

also include relatively low balances. According to the most recent National Postsecondary

Student Aid Survey, institutional loans received (by students who received that type of loan)

ranged from $10 to almost $37,000 (with an average amount just over $4,000).

39

Another

estimate based on institutional debts at select colleges in California suggests that average

institutional debts could be significantly lower (around $525), but these data sources may not

include tuition payment plans and thus may not reflect balances owed on these products.

40

1.1.3 Plan terms and number of installments

Almost all payment plans observed by the CFPB are structured to cover a student’s tuition and

other expenses for a single academic term (e.g., semester or quarter) and typically require

borrowers to pay off their outstanding balance in three to six installments.

41

Installments are

typically equal in size, with the exception of the first payment, which generally also includes the

full enrollment fee. Installment amounts also automatically adjust throughout a student’s term

37

This calculation takes the dollars outstanding in the retail installment contract portfolio ($214,195,000) and

divides by the total number of borrower relationships (40,238) to arrive at an average loan amount of $5,323.

38

See State of California, Dep’t of Financial Protection & Innovation, Directory of Student Loan Servicers Licensed

and Non-Licensed (covered) by the Department of Financial Protection and Innovation, (accessed Apr. 23, 2023),

https://dfpi.ca.gov/student-loan-servicer-licensees/.

39

U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, National Postsecondary Student Aid

Study: 2020 Undergraduate Students (NPSAS:UG). Institutional loan amount (INLNAMT) represents the total

amount of institutional loans (funded by the educational institution) that were received during the 2019-2020

academic year. Weight used in frequency: WTA000. The range of loan amounts received was $10 to $36,981 and the

average amount receive was $4,006.57.

40

Institutional loan data provided by a subset of public universities in California concluded that a total of almost

375,000 students in California took on institutional debt annually in the amount of $195 million, meaning that the

average institutional loan size in that sample was roughly $525 per student per year. However, it is not clear how the

schools in this dataset define andtracks institutional loans in their data and, thus, the inclusion of tuiti on p ayme n t

plans in the totals may varyor may exclude payment plans altogether. Thus,this data is of limited use for the purpose

of understanding average TPP loan amounts.

For more information, see: Eaton, C., Glater, J.; Hamilton, L.; &

Jiménez, D., (Apr. 1, 2022), Creditor Colleges: Canceling Debts that Surged during COVID-19 for Low-Income

Students, available at https://ssrn.com/abstract=4072193. Data used for this estimate reflect institutional debts

accrued in the 2020-2021 academic year.

41

The number of installments a student pays can vary both within a school and across schools. The number of

payments is influenced by the length of the academic term, when the student enrolls in the plan, the due date for the

full tuition payment, and the payment frequency (e.g., every two weeks, monthl y).

11 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

if they receive additional financial aid or incur additional expenses. Although most tuition

payment plans cover an academic term, schools have varying start dates and due dates, which

can result in different plan durations.

42

1.1.4 Fee structures

Based on the observed sample, typical plans include three types of fees: enrollment or set-up

fees, late fees, and returned payment fees (which do not include any separate insufficient funds

fee charged by the student’s financial institution). These fees are prevalent (Table 1). For

example, 89 percent of the plans the CFPB identified publicly disclosed an enrollment fee and

80 percent of observed payment plans disclosed charging a late fee and/or a returned payment

fee.

43

Typically, students also pay transaction fees if they pay using a credit or debit card, which

is a common practice on many types of consumer payments.

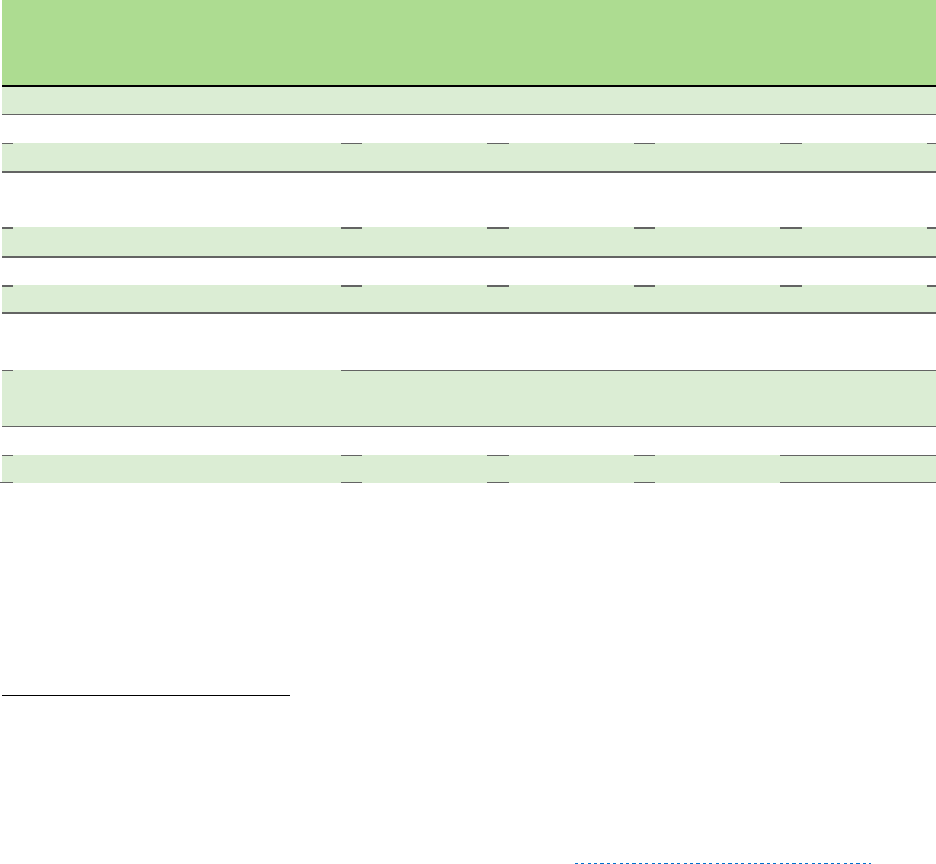

TABLE 1: TUITION PAYMENT PLAN FEE OVERVIEW

44

Fee Type Description

Share of Plans

with Fee Type

Disclosed

Median /

Average

Enrollment or

Set-Up Fees

Charged to student for each plan they

enroll in, typically per academic term; may

be disclosed as finance charges

89% $30 / $37

Returned

Payment Fee

Charged if payment is returned due to

insuf ficient funds or for any other reason

60% $30 / $29

Late Fee

Charged if a student misses a payment

deadline

44% $30 / $46

Schools often have the ability to set fee amounts, which are sometimes split with third-party

service providers. In cases where the school and third-party service provider split fees, the third-

party service provider often sets a baseline fee that the school can add onto. While schools

42

At all colleges where the CFPB identified a TPP offering(n=400), the CFPB observed 377 colleges(94 percent) at

which publicly disclosed TPP terms aligned with academic terms such as semesters or quarters, 7 colleges (2 percent)

with a TPP option up to 12 months, and 16 colleges where duration could not be found (4 percent).

43

The CFPB found 354 out of 400 payment plans publicly disclosed that they charged an enrollment fee. For the

remaining 43 plans, no publicly available information on an enrollment fee could be found (meaning that some of

these plans could charge enrollment fees). The CFPB added the 237 colleges that publicly disclose charging a returned

payment fee and the 174 colleges that p ublicly disclose charging a l ate fee and divided b y the total numb er of colleges

with publicly disclosed TPPs (n=400) to arrive at a total of 80 percent of colleges charging a late fee, a returned

payment fee, or both. One provider (Nelnet) automatically drafts students accounts on pre-set dates, so returned

payment fees may function as late fees in certain cases.

44

CFPB analysis of information provided on college websites. For more information about the methodology, see

Appendix A.

12 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

primarily set late fees, returned payment fees are often set by the third-party service provider. In

most cases, these fees are fixed sums and in other cases they are based on a percentage of a

borrower’s outstanding balance.

The median amount for flat fees was $30 each for enrollment fees, returned payment fees, and

late payment fees. However, the CFPB observed instances of much higher fees such as

enrollment fees as high as $200 on a plan offered directly by a school

45

and late payment fees as

high as $300 for a single instance of late payment. In other cases, late fees are expressed as a

percentage amount,

46

and the CFPB saw examples where schools may impose APR finance

charges of up to 18 percent

47

to past due balances.

FIGURE 3: ENROLLMENT, RETURNED PAYMENT, AND LATE FEE DISTRIBUTIONS

48

45

See, e.g., Arizona State University, Tuition and Aid Webpage (accessed Apr. 23, 2023),

https://tuition.asu.edu/billing-fi nances/payment-p lan#websp ark-anchor-li nk--19. This website states the “ASU

Payment Plan fee” is $100 for resident students and $200 for nonresident students.

46

See, e.g., Ferris State University, Student Account Payment Options and Due Dates, (accessed Jul. 21, 2023),

https://www.ferris.edu/administration/businessoffice/payments.htm. This website states that “Accounts are subject

to a 2% late fee for each missed payment.””

47

See, e.g., Franklin University, Payment Options Webpage, (accessed Jul. 21, 2023),

https://www.franklin.edu/tuition-financial-aid/payment-options. This website states that “There is a 7 day grace

period for all balances; thereafter past due balances are subject to an 18% APR finance charge.”

48

The CFPB’s analysis tracked fees across different colleges. This figure reports results at all colleges where tuition

payment plan flat fee amounts were publicly available. If multiple fee amounts were reported, the CFPB selected the

maximum (n=344 for enrollment fees, n=221 for returned payment fee, and n=125 for late fees).

13 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

1.1.5 Contract terms

Typically, colleges require students to sign contracts at the point of enrollment in order to

establish that students agree at the point of registration to pay for tuition, fees, and other

associated costs.

49

Colleges sometimes embed terms related to the payment of tuition and fees

into college enrollment documents that students are required to sign, some of which they may

sign before the term begins – such as registration agreements

50

and student financial

responsibility agreements.

51

The frequency at which schools present these types of contracts to

students varies and can be as infrequent as once at time of enrollment.

52

These enrollment documents govern tuition non-payment and may also govern late payment

and nonpayment of tuition payment plans”

53

In many cases, borrowers also sign contracts

provided at the point-of-enrollment in the tuition payment plan.

54

In some cases, provisions

about the consequences of late payments are not disclosed when students enter into the tuition

payment plan, which could lead to consumer confusion, and the presentation of consequential

contract terms in separate agreements could make it more difficult for consumers to students to

understand the product.

49

NACUBO and Fl ywire, Best Practices for Student Financial Responsibility Agreements: Advisory Report 21-02,

(2021), https://www.nacubo.org/Publications/Advisories/AR-21-02-Best-Practices-For-Student-Financi al -

Responsibility-Agreements, at 1 and 5.

50

See, e.g., Prairie View A&M University, Fee Payment Plans Webpage, (accessed Apr. 23, 2023),

https://www.pvamu.edu/fmsv/treasury-services/payments/fee-payment-p lans/. This webpage states that “All

students must accept the promise to pay payment agreement through Panthertracks that is presented at the time of

online registration[, which states that] ‘I agree that if I have not paid 100% of my current tuition, fees, and charges by

the last business day before the first class day, that PVAMU has my permission to automatically enroll me in the

installment method for payment of my current tuition….’”

51

NACUBO and Fl ywire, 2021. See also, e.g., Northwest Missouri State University, Statement of Financial

Responsibility, (May 15, 2023), https://www.nwmissouri.edu/studentaccounts/PDF/Statement-of-Financial-

Responsibili ty.p d f. This statement discloses terms related to transcript and registration holds, debt collection, and

credit reporting. See also, e.g., University of Rhode Island, University of Rhode Island Student Financial

Responsibilities Agreement, (accessed Aug. 27, 2023), https://web.uri.edu/tuition-billing/university-of-rhode-

island-student-financi al-responsibilities-agreement/.

52

Nati onal Association of College and University Business Officers (NACUBO), 2019 Student Financial Services

Policies and Procedures Report, https://www.nacubo.org/research/sfs%20benchmarking%20report, at 21.

53

NACUBO and Flywire 2021, at 3. “A student financial responsibility agreement provides relevant information about

official institutional policies to students and contractually binds them to these policies. It is intended to properly

disclose and set the contractual parameters between the creditor and consumer for the duration of the contractual

relationship and to outline the relevant remedies available if there is a material breach of the terms…. NACUBO

recommends use of a comprehensive student financial responsibility agreement as a student service best practice, to

clearly outline the creditor/consumer rel ationship, to protect the school, and to comprehensively disclosure student

obligations…. [The] legal goal [is] a clear contract that binds the student to the most current policies of the institution

and covers all the amounts that become due and owing during a student’s tenure with the institution.”

54

See, e.g., Bowling Green State University, BGSU – How to enroll in the Installment Payment Plan Video Tutorial,

(accessed May 24, 2023), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rj_Aohy2Oa8&t=78s.

14 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

Contract terms and conditions can vary widely. The CFPB identified instances of the following

terms and conditions in agreements that appear to govern the use of tuition payment plans:

Waivers of consumer rights: In some cases, tuition payment plan contracts require

students to waive their right to participate in any class action or representative lawsuit

and to only seek remediation through mandatory arbitration.

55

Balance acceleration and changes: In some cases, a student’s entire balance could

be accelerated if they miss a single payment.

56

In other cases, late payments may convert

a no-interest installment plan into an interest-bearing loan.

57

Transcript and registration holds: If a student has outstanding debt (i.e., from

missing a scheduled payment), some schools may place the student on an academic hold,

barring them from attending classes or withholding their official transcript or diploma.

58

Debt collection and credit reporting: Some colleges send the student’s outstanding

obligations to a debt collector and report the debt to a credit bureau. In these cases, the

school typically adds any fees associated with debt collection to the student’s bill.

59

1.2 Third-party private installment loans

The CFPB recognizes that other installment loan options are offered by third-party private

lenders that are not colleges. However, because these products are not offered directly by

colleges, they are outside of the scope of this report.

55

See, e.g., Valencia College, Nelnet Business Solutions Terms & Conditions, (accessed Jan. 31, 2023),

https://valenciacol lege.edu/students/business-office/tuition-installment-plan/nelnet-ter ms.p hp .

56

See, e.g., Thomas Jefferson School of Law, Student Handbook, (accessed May 24, 2023),

https://www.tjsl.edu/sites/default/files/student_handbook_jd_program_-_ca l s_-_january_23_2022.pdf, at 55.

This handbook states that “If [a student fails] to make any payment on time, the entire unpaid balance including

service charges, plus any applicable penalty charges may, at the sole option of the School, become immediately due

and payable.”

57

See, e.g., Franklin University, Tuition Payment Plans & Options Webpage, (accessed Apr. 23, 2023),

https://www.franklin.edu/tuition-financial-aid/payment-options. This website states that “There is a 7 day grace

period for all balances; thereafter past due balances are subject to an 18% APRfinance charge.”

58

See, e.g., Bethel University, Holds & Student Billing Policies, (accessed May 24, 2023),

https://www.bethel.edu/business-office/student-billing-policies. This website states that “When payments have not

been received by the appropriate due date, a hold will be placed on your account” and links to additional information

about registration and transcript holds.

59

See, e.g., Salisbury College, Penalties for Late Payment and Non Payment Webpage, (accessed Feb. 1, 2023),

https://www.salisbury.edu/administration/administration-and-finance-offices/financial-services/accounts-receivable-cashiers-

office/payment-penalties.aspx. See also, e.g., Chicago State University, Payment Deadlines & Plans Webpage, (accessed

Apr. 23, 2023), https://www.csu.edu/financialoperations/bursar/payment_deadlines.htm.

15 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

States and consumer advocates have noted that these types of installment products may be

prevalent among non-accredited programs and have raised concerns about the growth of

installment lending enabling students to attend high-cost non-accredited and/or low-quality

programs, including those offered by buy now pay later (BNPL) providers (who traditionally

have provided installment lending in the retail space).

60

For example, a 2022 report highlighted

that BNPL providers such as PayPal, Affirm, Klarna, Sezzle, Shop Pay, Uplift, and Zip have

partnered with bootcamp programs to offer education installment loans.

61

The CFPB recently

estimated, based on newly-available data, that private sector lending for education by BNPL

lenders increased by 1,028 percent between 2019 and 2021, indicating rapid growth in recent

years.

62

Other third-party private lenders for education include Meratas, Climb Credit, TFC

Tuition Financing,

63

and Meritize.

60

State Attorneys General of Illinois et al., Comment Letter on Notice and Request for Comment Regarding the

CFPB’s Inquiry Into Buy-Now-Pay-Later Providers, Docket No. CFPB-2022-0002 (Mar. 25, 2022),

https://www.regulations.gov/comment/CFPB-2022-0002-0025.

61

See, e.g., Student Borrower Protection Center, (Mar. 2022), Point of Fail: How a Flood of “Buy Now, Pay Later”

Student Debt is Putting Millions at Risk, https://protectborrowers.org/wp-

content/uploads/2022/03/SBPC_BNPL.pdf.

62

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, (Sep. 2022), Buy Now, Pat Later: Market Trends and Consumer Impacts,

https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/cfpb_buy-now-pay-l ater-market-trends-consumer-

impacts_report_2022-09.pdf. This report specifies that the “Services” vertical, which includes education (alongside

insurance, pet care, services, and subscription fees), represented only 2.6 percent of total BNPL loan volume in 2021

[and that] In 2021, the five lenders surveyed [by the CFPB] originated $59.8 million in BNPL loans to retailers in the

Education sub-vertical.”

63

See, e.g., Circle of Love Academy, Student Information Webpage (accessed Apr. 25, 2023),

https://circleofloveacademy.com/student-information. This website states that “To get started with TFC Tuiti on

Financing, you simply contact your management team and ask them to help you set up a payment plan that works for

you.” See also, e.g., The Academy of Pet Careers, TFC Tuition Loans Webpage, (accessed Apr. 25, 2023),

https://www.theacademyofpetcareers.com/loan-application/. This website states that “The APC is partnered with

TFC Tuition to provide our students with customized payment plans designed for success after graduation.”

16 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

2. Consumer risks

The CFPB’s research has identified several features of tuition payment plan products offered by

colleges that may pose consumer risks. These include inconsistent product definitions and

disclosures, hidden or non-elective enrollments, high costs related to late payment, potentially

deleterious debt collection practices, and waivers of consumer rights.

2.1 Inconsistent disclosures

The wide variation in terms that are offered by tuition payment plans, and the terminology that

schools use to describe them, may confuse consumers about the nature of the financial

arrangement they are entering into. For instance, some schools market tuition payment plans as

an alternative to student loans.

64

Others describe very similar no-interest products as loans

(Table 2).

65

Further, information about fee levels and terms are often spread across several

different documents and/or webpages, which may make it difficult for consumers to find

complete information. Overall, these practices could obscure the nature of the product, the cost

of credit, and what entity owns or services the product.

66

And because tuition payment plans are

often offered to students by their schools after they have already enrolled, the circumstances

might result in a captive market in some situations in which students may not be able compare

the products to other options.

64

While tu iti on p ayme nt p lans are generally mark eted this way, many tuition payment plans are in fact private

student loans under TILA, generally as non-Title IV loans issued for postsecondary educational expenses to a

borrower that does not include an extension of credit under an open-end consumer credit plan, a reverse mortgage

transaction, a residential mortgage transaction, or other real-estate or dwelling secured loan. See 15 U.S.C.

1650(a)(8). And, depending on their structure, some maystill be closed-end credit under Regulation Z, at 12 CFR part

1026. Specifically, Regulation Z excludes tuition payment plans from its definition of “private education loan” if no

interest is applied and the term of the extension of credit is one year or less. 12 CFR 1026.46(b)(5)(iv)(B). As a result,

such tuition payment plans are not required to comply with Regulation Z’s private education loan disclosure and

timing requirements. However, suchtuition payment plansmight stil l be considered closed-end credit – and colleges

offering the plans may be considered creditors – under Regulation Z and be subject to the regulation’s general

advertising, disclosure, and timing requirements that apply to closed-end credit. This could be the case, for example,

if a tuition payment plan has more than four installments or is subject to a finance charge, which may mean that the

school is a creditor subject to the disclosure and timing requirements for closed-end credit under Regulation Z. See 12

CFR §§ 1026.2(a)(17), 1026.17, 1026.18, and 1026.24.

65

See, e.g., Transact Holdings Inc., 2022, Payment Plans: An alternative to student loans,

https://transactcampus.com/resources/infographics/request/an-easier-way-to-p roce ss-payment-plans. Accessed

January 11, 2023.

66

In interviews conducted in March 2023 with current students, the CFPB observed that some students did not

understand that some tuition payment plans could be forms of credit, and some did not understand thatthe tuition

payment plan they were using was offered by theirschool and not by the federal government. Others thought that a

tuition payment plan was simply a plan to repay their federal student loan debt.

17 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

Key differences in tuition payment plan descriptions observed by the CFPB include (Table 2):

Whether a non-interest-bearing payment plan was called a loan;

67

Whether product costs and fees were publicly disclosed on college websites;

Whether the cost of credit was clearly disclosed and whether fees were treated as finance

charges. Across schools, similar products were found to have inconsistent APR

disclosures;

68

and

Whether the TILA requirements for closed-end credit advertising under Regulation Z are

being applied.

69

TABLE 2: TUITION PAYMENT PLAN PRODUCT DESCRIPTION EXAMPLES

Institution Product Description

Georgia Southwestern “This is not a loan program. You have no debt, there are no interest or

f inance charges and there is no credit check.” State University

70

“The enrollment fee is considered a finance charge … To make it easy for

consumers to compare this cost to other forms of credit, Transact provides

the equivalent annual percentage rate (APR) … Maximum APR limits may

be subject to applicable state usury laws.”

Harford Community

C

ollege

71

“These services and benefits constitute educational loans or benefits

Colorado Mesa

extended to me to finance my education [and] may not be discharged in

University

72

bankruptcy.”

These inconsistencies in product definitions and disclosures could make it difficult for students

to understand the true cost of credit, compared to other education financing options. While

67

This is further complicated b y the exampl es of interest-bearing private loan products being advertised as “payment

plans.”

68

See 12 CFR 1026.4 (regarding finance charges) and 1026.24 (regarding closed-end credit advertising

requirements).

69

This report does not comment on the applicability of these requirements for any specific tu i tion p ayme nt plan

because such a determinationwould be fact-specific and is outside of the scope of this report and the information

reviewed.

70

Georgia Southwestern State University, Nelnet Payment Plan Webpage, (accessed Feb. 15, 2023),

https://www.gsw.edu/student-account/nelnet-payme nt-plan.

71

Harford Community College, Payment Plan Webpage, (accessed Feb. 15, 2023),

https://www.harford.edu/admissions/tuition/payment-plan.php;

72

Colorado Mesa University, Student Financial Responsibility Agreement, (accessed Feb. 15, 2023),

https://www.coloradomesa.edu/student-accounts/documents/financial-responsibility-agreement.pdf.

18 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

some schools provide sample TILA disclosures, others do not. And when TILA disclosures are

provided, rates can vary widely based on plan details such as the size of the enrollment fee.

73

Despite rarely charging interest, tuition payment plans are still a form of credit that may subject

consumers to various fees. The cost of credit can vary widely based on the terms of the specific

plan, the amount financed, and the size of the enrollment fee. Some tuition payment plans have

relatively low costs of credit (around 2 percent APR).

74

Other payment plans that are used to

finance smaller amounts, charge higher than median fees, and/or plans that compel repayment

over shorter durations can lead to relatively high APRs: The CFPB estimates that some plans,

under certain circumstances (e.g. for students who borrow small amounts and pay high

enrollment fees) could have annual percentage rates up to 237 percent.

75

In addition to inconsistent terms and disclosures among tuition payment plans, students may

face further risk because some schools and bootcamps use terms similar to those used in tuition

payment plans, like “payment plans”

76

and “financing plans”

77

to describe private, interest-

73

For example, some schools offer sample annual percentage rate (APR) disclosures in videos or documents that

provide instructions for students who are interested in enrolling in a tuition payment plan. The CFPB observed

sample rates as low as zero percent and as high as 182 percent. See, e.g., University of Texas at Tyler, Enroll in a

Payment Plan How-to Video, (accessed May 25, 2023),

https://www.uttyler.edu/enroll/tutorial-library/payment-

plan/. See also, e.g., Baton Rouge Community College, How to Make a Payment Tutorial, (accessed May 25, 2023),

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1QRNMcVY1qpbQk zf1JRgqCqrOEKCAEYVUY3aQxryfTpg/edit, at 16.

74

CFPB analysis using the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council’s (FFIEC) APR Tool,

https://www.ffiec.gov/examtools/FFIEC-Calculators/APR/#/accountdata. This analysis models APRs for tuition

payment plans with a semester term (defined as three months) that are paid with four payments (with the first

payment made at the time of consummation and the finance charge incurred on the first payment), assuming that

payments were due monthly. The plan that resulted in an APR of 2 percent assumed a finance charge of $30 and a

loan amount of roughly $5,500. See Section 1.1.2 for additional detail on and about the sources and limitations of

these tuition payment plan average loan amount estimates.

75

CFPB analysis using the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council’s (FFIEC) APR Tool,

https://www.ffiec.gov/examtools/FFIEC-Calculators/APR/#/accountdata. This analysis models APRs for tuition

payment plans with a semester term (defined as three months) that are paid with four payments (with the first

payment made at the time of consummation and the finance charge incurred on the first payment), assuming that

payments were due monthly. The plan that resulted in an APR of 237 percent was modeled to include the highest

observed enrollment fee of $200 and a small amount financedof $525. The highest observed enrollment fee on a

tuition payment plan offered by a college was $200 at Arizona State University. See Section 1.1.2 for additional detail

on and about the sources and limitations of these tuition payment plan average loan amount estimates. See also, e.g.,

Carter, C., (2022), “Predatory Installment Lending in the States: How Well Do the States Protect Consumers Against

High-Cost Installment Loans?,” National Consumer Law Center,

https://www.nclc.org/resources/predatory-

installment-lending-in-the-sta tes-2022/ (describing state interest rate caps and noting a median 39.5% APR limit for

$500, six-month installment loans and a 32% APR limit for $2,000, two-year installment loans in 2022). See also 10

U.S.C. § 987(b) and 32 CFR 232.4(b) (setting 36 percent limit for military annual percentage rates (MAPRs)). We do

not comment in this report as to the applicability of any state interest rate or MAPR limits to the tuition payment

plans reviewed.

76

See, e.g., Aviation Institute of Maintenance – Atlanta, (Jun. 2022), A Guide to Our Financial Aid Programs and

Consumer Information, https://aviationmaintenance.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/FA-Guide-for-Stu den ts-

07132022.pdf, at 10. This guide states that “We may be able to provide interest bearing monthly payment plans for

students who are not eligible for other financial aid plans or sufficient financial aid.”

77

See, e.g., San Joaquin Valley College, Financial Aid at San Joaquin Valley College Webpage, (accessed Apr. 25,

2023), https://www.sjvc.edu/guides/financial-aid/.

19 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

bearing education loans. This overlap in terminology could lead to consumer confusion about

the nature of the product. For instance, one boot camp program’s “deferred tuition” option

(structured as a 12.5 percent interest rate loan with an additional 5 percent origination fee) was

advertised using the slogan “learn now, pay later,” which may lead borrowers to wrongly believe

the product is structured like a typical no-interest BNPL loan or tuition payment plan.

78

2.2 Automatic enrollments and forced use

In some cases, borrowers may become enrolled in a tuition payment plan without knowingly

signing up for one or because institutional Title IV disbursement practices leave students

without viable alternatives. Sometimes, students do not receive their federal financial aid

disbursements in time to meet their school’s tuition payment deadlines, due to a delay or

differences between disbursement dates and tuition payment deadlines. In other cases, students

may withdraw from school and may be on the hook to repay the school for all or some of a

previously disbursed financial aid award such as a Pell Grant, the amount of which has been

based on the student’s enrollment for the full academic term. When this occurs, the use of

tuition payment plans may lead to the accumulation of fees (such as enrollment fees and late

fees).

Enrollment due to financial aid delays

In the CFPB’s review of complaints submitted to the Department of Education, we observed that

several students indicated in complaints that they felt they had no option but to enroll in tuition

payment plans, most often in cases where their tuition due date did not line up with their federal

financial aid disbursement date. For instance, one school states on its website that students who

don’t know if they are getting financial aid yet or who think it will come at some point during the

academic term should enroll in a payment plan.

79

In an unrelated complaint from a student, a

Pell Grant recipient called the Department of Education’s Office of Federal Student Aid (FSA)

about processing delays related to her disbursement and said that she was told by her school

that if she did not sign up for a payment plan she would be dropped from classes.

80

Another student complained about the high cost of the tuition payment plan offered by their

school and stated that:

78

See, e.g., Bloom Institute of Technology, Deferred Tuition Webpage, (accessed Apr. 25, 2023),

https://www.bloomtech.com/tuition/deferred-tuition.

79

Lane Community College, College Account Payment Plans Frequently Asked Questions, (accessed Apr. 25, 2023),

https://inside.lanecc.edu/sites/default/files/collfin/ways-to-pay-faq.pdf.

80

Complaint submitted to the U.S. Department of Education, Office of Federal Student Aid on August 10, 2021.

20 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

[My institution’s] inability to process student’s financial aid in a timely

manner [forces] students and parents to sign up for [a] payment plan which is

more expensive…. I feel that if it is the school that cannot process financial aid or deal

with the amount of students then the students should not have to pay for their mistakes….

The school’s financial aid practices should be investigated.

81

In another example, a student at a large public university complained to ED that they were

enrolled in a tuition payment plan due to a disbursement delay:

Due to system issues that delayed receiving my aid by weeks [at my school

and despite being told by several financial aid representatives] that I wouldn’t

be enrolled in the payment plan…I was charged this fee and enrolled into the

plan [emphasis added]. Additionally, I’m entering the 3

rd

week of classes for the semester

and still haven’t received my student loans…. I filled out any additional tasks required

promptly – often that same day…. I have to use the remainder of the student loans for

textbooks, housing, and other related educational expenses. This delay by them has cost me

extra fees, stress, and grief.

The student received their financial aid disbursement three days after they submitted the

complaint.

82

Another similar complaint from a Pell Grant recipient at a community college stated that:

[Every] semester I try to take classes [at my school], they try to force me into

setting up [a] payment plan to pay out of pocket when my [Pell Grant] has not

been issued. I then had to drop several classes due to the fact that I couldn’t afford the

next payment and my [Pell Grant] never came.

FSA advised this student to work with the school to pay any balance owed.

83

Another similar complaint from a Pell Grant recipient at a community college stated that:

I have received the Pell Grant, but my school doesn’t seem to be dispersing

[sic] any payments to me. They put me on a payment plan, and I had to pay

about $800 out of pocket. I looks like they are going to make me pay another $800 out

of pocket in the next couple of weeks (money that I don’t have)…. They just keep telling me

81

Complaint submitted to the U.S. Department of Education, Office of Federal Student Aid on August 22, 2018.

82

Complaint submitted to the U.S. Department of Education, Office of Federal Student Aid on August 31, 2022.

83

Complaint submitted to the U.S. Department of Education, Office of Federal Student Aid on February22, 2019.

21 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

that things are “processing.” I suspect I am not the only student who is having this problem

here. I don’t know what to do anymore.

The student asked FSA to help them receive their full disbursement to help them avoid making

future out-of-pocket payments and wanted a refund for their prior payment. After researching

the student’s situation, FSA concluded that the student’s institution has a practice of disbursing

the Pell Grant in multiple payments, which is in compliance with federal regulations.

84

Enrollment due to withdrawal from classes

The CFPB observed that some schools may enroll students in tuition payment plans

automatically if they miss a tuition payment deadline.

85

In other cases, students who withdraw

from school after the school’s tuition refund deadline has passed may have their previously

disbursed Pell Grant, other federal student financial aid, or federal student loan disbursement

revoked and converted into a balance or debt owed to the school. When this occurs, some

schools may automatically convert this financial obligation into a tuition payment plan

(sometimes called a past-due payment plan).

86

This practice has been highlighted as one that

may have a disproportionate impact on low-income students who withdraw from school due to

emergencies such as family needs or health crises.

87

These automatic enrollment and forced use practices may present harms to students by adding

fees to the cost of attending school or by compelling out-of-pockets payments during the school

year.

84

Complaint submitted to the U.S. Department of Education, Office of Federal Student Aid on September 5, 2019.

Under the Department’s regulations, an institution may pay a student Federal Pell Grant funds at such times and in

such installments as it determines will best meet the student’s needs. 34 CFR 690.76(a).

85

See, e.g., Arizona State University, Tuition and Aid Webpage (accessed Apr. 23, 2023),

https://tuition.asu.edu/billing-finances/payment-plan#we bsp ark-anchor-li nk--19. This website states that “If you

have outstanding charges of $500 or more after the payment deadline, you’ll be automatically enrolled in the ASU

Payment Plan and be billed an ASU Payment Plan fee [of $100 for resident students or $200 for nonresident

students].” See also, e.g., Oklahoma Community College, Bursar Webpage, (accessed Jan. 11, 2023),

https://www.occc.edu/bursar/. This website states that “If you miss your designated due date for an in-full payment, we’ll

automatically place you on a monthly payment plan that lets you payoff your tuition and fees over time. The payment

plan incurs a $25 set-up fee per term.”

86

See 34 CFR 668.22; U.S. Dep’t of Education, Office of Federal Student Aid, Return of Title IV Funds (R2T4),

(accessed Feb. 2, 2023), https://fsapartners.ed.gov/knowledge-center/library/functional-

area/Return%20of%20Title%20IV%20Funds%20%28R2T4%29#:~:text=R2T4%20refers%20to%20the%20calculation,which%2

0the%20recipient%20began%20attendance. See also, e.g., Eaton, C., Glater, J.; Hamilton, L.; & Jiménez, D., (Apr. 1,

2022), Creditor Colleges: Canceling Debts that Surged during COVID-19 for Low-Income Students, available at

https://ssrn.com/abstract=4072193.

87

Eaton, C., Glater, J.; Hamilton, L.; & Jiménez, D., (Apr. 1, 2022), Creditor Colleges: Canceling Debts that Surged

during COVID-19 for Low-Income Students, available at https://ssrn.com/abstract=4072193.

22 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

2.3 High costs related to late payment

If students fall behind on their payments, they are typically assessed late fees, and may

sometimes also be subject to a returned payment fee if their automatic payment was declined.

Even students who miss just one payment may be subject to balance acceleration, where the

entire balance of the loan becomes due in full, or may have their non-interest-bearing loan

converted into an interest-bearing loan.

88

These practices can impose high costs on students

who make late payments.

89

The CFPB found that four out of five plans publicly disclose that they impose late fees, returned

payment fees, or both.

90

Median returned payment and late fees were both $30 and the average

fees were of $29 and $47 respectively.

91

However, a 2019 industry survey established that,

among a different sample of schools charging late fees, the average maximum late fee was

almost $110.

92

The CFPB observed 19 plans that had late fees of $100 or more.

93

In addition, almost 30 of the schools researched by the CFPB, representing 18 percent of the

total sample, imposed late payment penalties that were calculated as percentages of outstanding

88

See, e.g., Franklin University, Tuition Payment Plans & Options Webpage, (accessed Apr. 23, 2023),

https://www.franklin.edu/tuition-financial-aid/payment-options. This website states that “There is a 7 day grace

period for all balances; thereafter past due balances are subject to an 18% APR finance charge.”

89

Industry groups estimate that an average of 32 percent of current and former students had unpaid balances owed

to their colleges at the end of FY20. See National Association of College and University Business Officers, 2021

Student Financial Services Benchmarking Report, at 3. This report i s b ased on survey responses col lected between

2017 and 2021 and this data point is based on 2021 survey responses from hundreds of participating institutions. This

report also states that in FY20, approximately 4 percent of student accounts were placed into internal or external

collections, but this percentage includes only students who were “enrolled in credit-earning courses” and thus is

unlikely to include students who were dropped from courses due to non-p a yme nt.

90

To determine this, the CFPB added the 237 colleges that publicly disclose charging a returned payment fee and the

174 colleges that publicly disclose charging a late fee, then subtracted the 93 colleges that publicly disclose charging

both fees – and divide by the total number of col leges with publicly disclosed TPPs (n=400). More colleges may

charge late and returned payment fees but may not disclose them publicly (i.e., col leges may include them in point-of-

sale disclosures to students).

91

In many cases, the fees observed by the CFPB were higher than comparable fees charged on other consumer

products such as credit cards. In the credit card context, TILA section 149, requires, among other things, that the

amount of any penalty fee with respect to a credit card account under an open-end consumer credit plan in

connection with any omission with respect to, or violation of, the cardholder agreement, including any late p ayme nt

fee or any other penalty fee or charge, must be “reasonable and proportional” to such omission or violation. 15 USC

1665d(a). The Bureau issued a proposed rule on credit card late fees pursuant to this provision on March 29, 2023

and is currently reviewing comments. 88 FR 18906

92

National Association of College and University Business Officers, 2019 Student Financial Services Policies and

Procedures Report, at 9. This average amount is based on responses from 454 schools and refers to the maximum, or

“capped,” late fee that those schools charge in their late fee policy for undergraduates (see page 42 of the NACUBO

report for exact survey language).

93

See, e.g., The Ohio State University, Pay Tuition and Fees Webpage, (accessed Apr. 23, 2023),

https://busfin.osu.edu/bursar/paytuition. This webpage discloses that “Failure to pay by the due date listed for each

installment may result in late fees being assessed to your account [of] up to $300 for the first installment [and] $25

per installment for subsequent installments.”

23 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

balances,

94

with the average amount being nearly 11 percent.

95

In one case, after a seven-day

grace period, one school imposed an 18 percent APR finance charge, which was the highest APR

observed.

96

One student complained about fees on their payment plan and stated that:

My [loan and grants] are dispersing in October [and] these are enough to cover the coming