The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S.

Department of Justice and prepared the following final report:

Document Title: Intimate Partner Abuse in Divorce Mediation:

Outcomes from a Long-Term Multi-cultural

Study

Author: Connie J. A. Beck, Ph.D., Michele E. Walsh,

Ph.D., Mindy B. Mechanic, Ph.D., Aurelio Jose

Figueredo, Ph.D., Mei-Kuang Chen, M.A., M.S.

Document No.: 236868

Date Received: December 2011

Award Number: 2007-WG-BX-0028

This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice.

To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally-

funded grant final report available electronically in addition to

traditional paper copies.

Opinions or points of view expressed are those

of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect

the official position or policies of the U.S.

Department of Justice.

Intimate Partner Violence in Mandatory Divorce Mediation

Beck, Walsh, Mechanic, Figueredo & Chen 1 2007-WG-BX-0028

Intimate Partner Abuse in Divorce Mediation

Outcomes from a Long-Term Multi-cultural Study

Connie J. A. Beck, PhD

1

Michele E. Walsh, PhD

2

Mindy B. Mechanic, PhD

3

Aurelio Jose Figueredo, PhD

1

Mei-Kuang Chen, MA, MS

1

1

School of Mind, Brain and Behavior

Department of Psychology

University of Arizona

Tucson, AZ 85721

2

John & Doris Norton School of Family and Consumer Sciences

Frances McClelland Institute for Children, Youth and Families

University of Arizona

Tucson, AZ 85721

3

Department of Psychology

California State University, Fullerton

April, 2011

Revised July, 2011

Intimate Partner Violence in Mandatory Divorce Mediation

Beck, Walsh, Mechanic, Figueredo & Chen 2 2007-WG-BX-0028

National Institutes of Justice, grant number 2007-WG-BX-0028

Acknowledgements

The study was a massive undertaking spanning nearly a decade. There are many people who

were indispensible in making the study possible. We would first like to thank Pima County

Superior Court Judges Karen Adam and Jan Kearney for recognizing the importance of this

study for family law in Pima County, Arizona, providing access to the databases and for their

support and guidance throughout the project. Without their support the project could never have

been completed.

We would next like to thank the current (Grace Hawkins) and former (Fred Mitchell) directors of

the Pima County Family Center of the Conciliation Court. Grace Hawkins was instrumental in

assisting the study by providing research office space, record storage space, access to computers

and court databases and for allowing the research team to spend years collecting data at their

offices. Fred Mitchell continued the work of former director Linda Kerr in identifying the need

for adequate screening for intimate partner abuse at the study site. Dr. Mitchell instituted a policy

requiring use of a written questionnaire screening measure, which became an integral part of the

data. Paul LaFrance, former office manager, identified variables within the mediation case files

and consulted on many aspects of the initial design of the study. Without this long-term support

the project would not have been possible. Thank you to the many mediators and office staff at

the Conciliation Court for answering our questions and providing assistance to us as we collected

the data. It is a rare public agency that welcomes this type of in-depth research and analysis of

their work.

We would also like to thank Sergeant William Briamonte of the Tucson Police Department and

Mr. Frank Gonzalez of the Pima County Sheriff’s office for working closely with the research

team and designing methods for data collection from area law enforcement databases. Our

colleague and friend Dr. Edward Anderson of the University of Texas at Austin provided vital

statistical consulting and conducted the latent class analyses in this study.

There are few studies which can be conducted without the extensive support of students. We

thank the many undergraduate students (Jessica Jorgensen Willis, Fairlee Fabrett, Merredith

Levenson, Stacey Brady, Whitney Kearney, Melissa Rubin, Ryan Davidson; Karey O’Hara

Brewster), Devon Harris and graduate students (Caitilin Taylor, Marieh Tanha and Melissa

Tehee) who contributed to collecting data, abstracting information from court records, coding

and entering data and conducting reliability checks. In particular, a heartfelt thanks to Karey

O’Hara Brewster and Ryan Davidson. Karey served mid-study as lead research keeping the

project organized and training other students in data collection. Ryan served as the lead research

assistant and liaison to the law enforcement agencies and kept the project going in its final

stages.

Thanks are also due to the National Institute of Justice (NIJ) for the financial support of this

project. Funding for mediation research is so difficult to secure yet so important for the lives of

divorcing parents and children, particularly those with intimate partner violence. We thank the

NIJ staff members who have worked with us over the years. Leora Rosen was instrumental in

stewarding us through the grant application and review process. Christine Crossland, Bethany

Intimate Partner Violence in Mandatory Divorce Mediation

Beck, Walsh, Mechanic, Figueredo & Chen 3 2007-WG-BX-0028

Backes and Bernie Auchter have served as program officers. A special thanks to Bernie Auchter

for his helpful suggestions, patience and generosity in providing important opportunities for us to

discuss the issues in this study and to present the research to a broad audience. Thanks are also

extended to the two reviewers of the draft final report. Both provided to us extremely important

comments and insights.

Intimate Partner Violence in Mandatory Divorce Mediation

Beck, Walsh, Mechanic, Figueredo & Chen 4 2007-WG-BX-0028

Abstract

Despite three decades of scholarly research on numerous aspects of divorce mediation,

there is no comprehensive understanding of the short- and long-term outcomes for couples

legally ordered to mediation to resolve custody and parenting time disputes or for those using

free (or low cost) conciliation court mediation services to do so. Even less is known about the

use or effectiveness of court-mandated mediation services among couples alleging intimate

partner abuse (IPA). This study was funded by NIJ to address these gaps in the literature. Using

several archival court and law enforcement databases, we systematically documented actual

percentages of IPA in those participating in mediation, systematically analyzed mediator

practices addressing those IPA cases, and systematically assessed mediation outcomes, divorce

outcomes and post-decree outcomes for IPA cases.

To accomplish this we linked archival data from two court databases and two law

enforcement databases for a large matched sample (N=965) of couples involved in the divorce

process in one court-based mediation program in one jurisdiction. We first linked data produced

in business-as-usual, naturalistic clinical interviews used to screen parents for marital stressors

and IPA to questionnaire data also measuring specific IPA-related behaviors. We then linked this

IPA data to the mediator’s decisions concerning whether to identify a case as having IPA or not,

whether to proceed in mediation or to screen out IPA-identified cases, and whether to provide

special procedural accommodations for IPA-identified cases.

We then linked the IPA and mediator decision data to mediation outcome data from

mediation case files and to outcomes in final divorce decrees and parenting plans found in

Superior Court divorce files. We then linked these pre-divorce and divorce data to post-divorce,

longitudinal data concerning re-litigation of divorce-related issues in Superior Court and

longitudinal data concerning contacts with area law enforcement.

The results of this study provide strong empirical support for previous estimates that most

couples attending divorce mediation report some level of IPA. Mediators accurately identified

many but not all client self-identified cases of IPA. One third of the couples classified as non-

IPA reported at least one incident of threatened and escalated physical violence or sexual

intimidation, coercion or assault. Cases were rarely screened out of mediation (6%) and special

procedural accommodations were most often provided in cases where a parent called the

mediation service requesting the accommodations or reporting concerns about IPA and about

participating in mediation (84%). Calls to area law enforcement and orders of protection were

common (approximately 40% of couples for each category). While mediation agreements that

included restrictions on contact between parents or on parenting were rare, the victims of the

highest level of IPA often left mediation without agreements and returned to court, wherein they

obtained restrictions on contact between parents and/or restrictions on aspects of parenting at a

much higher rate than those appearing in mediation agreements.

Mediators are not judges and therefore, these results are to be expected. It is a rare abuser

who will voluntarily agree to terms that allow less control over contact with the victims and more

structured contact with the couple’s children. The majority of parents in the study returned to

court at some point to re-litigate divorce-related issues (62%); however, a small group of couples

(4.5%) who returned for a tremendous number of hearings (31% of total number of hearings for

all couples in study). The fact that parents reaching agreements are less likely to relitigate

provide significant support for the use of mediation programs.

Intimate Partner Violence in Mandatory Divorce Mediation

Beck, Walsh, Mechanic, Figueredo & Chen 5 2007-WG-BX-0028

According to reporting by parents in this study, at least some form of IPA occurred in

over 90% of the cases and two thirds of the couples reported that either or both partners utilized

outside agency involvement from police, shelters, courts, or hospitals to handle the IPA. These

figures represent a tremendous amount of IPA in couples mandated to attend mediation. Thus, it

is essential that highly trained mediators who use standardized screening procedures and follow

program policies regarding how to handle IPA cases.

Intimate Partner Violence in Mandatory Divorce Mediation

Beck, Walsh, Mechanic, Figueredo & Chen 6 2007-WG-BX-0028

Table of Contents

Intimate Partner Abuse in Divorce Mediation ................................................................................ 1

Abstract ....................................................................................................................................... 4

Acknowledgements ..................................................................................................................... 2

Table of Contents ........................................................................................................................ 6

List of Figures ............................................................................................................................. 9

List of Tables .............................................................................................................................. 9

Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................... 11

Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 11

Study Goals ............................................................................................................................... 11

Goal 1: Determine whether the mediation program accurately identifies couples with

self-identified IPA and assess whether these cases are treated differently. .......................... 12

Goal 2: Assess whether mediation agreements, divorce decrees and/or parenting plans

include safety measures in cases involving self-reported IPA. ............................................. 12

Goal 3: Assess the frequency with which mediation agreements/divorce decrees are re-

litigated over time. ................................................................................................................ 12

Goal 4: Test a multivariate conceptual model using variables that are hypothesized to

affect mediation, divorce case and post-divorce outcomes (see Cascade Model Figure 16).

12

Study Methods .......................................................................................................................... 12

Results and Conclusions ........................................................................................................... 13

Goal 1: Determine whether the mediation program accurately identifies couples with

self-identified IPA and assess whether these cases are treated differently. .......................... 13

Goal 2: Assess whether mediation agreements, divorce decrees and/or parenting plans

include safety measures in cases involving self-reported IPA. ............................................. 18

Goal 3: Assess the frequency with which mediation agreements/divorce decrees are re-

litigated over time. ................................................................................................................ 21

Goal 4 Results: Test a multivariate conceptual model using variables that are hypothesized

to affect mediation, divorce case and post-divorce outcomes (see Cascade Model Figure 16

............................................................................................................................................... 22

Recommendations for Research, Policy and Practice ............................................................... 28

Limitations ................................................................................................................................ 25

(1) Provide essential training in the dynamics of IPA .................................................... 28

(2) Use a structured, systematic approach to assessment of IPA in mediation .............. 28

(3) Automate screening measures ................................................................................... 29

(4) Assess Mediation special procedures to accommodate victims ............................... 29

(5) Acknowledge the limitations of the mediation process ............................................ 30

(6) Investigate hybrid mediation/arbitration mediation interventions ............................ 30

(7) Encourage legal findings of “domestic violence” in appropriate cases .................... 31

(8) Assess outcomes for children directly and prospectively ......................................... 31

(9) Assess the effectiveness of court-based programs for pre- and post-divorce “frequent

flyers” 32

Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 33

Review of Relevant Research and Background of Study ......................................................... 33

Statement of the Problem. ......................................................................................................... 33

Intimate Partner Violence in Mandatory Divorce Mediation

Beck, Walsh, Mechanic, Figueredo & Chen 7 2007-WG-BX-0028

What is mediation in this context? ........................................................................................ 33

Why did conciliation courts become the main services providers of mandated divorce

mediation? ............................................................................................................................. 35

What is intimate partner violence (IPA)? ............................................................................. 38

Why is mediation often legally mandatory? ......................................................................... 36

Why is mandatory mediation a potential problem for couples with IPA? ............................ 42

What is the prevalence of IPA in couples mandated to mediation? ..................................... 43

What dimensions of IPA are found in couples attending divorce mediation? ...................... 44

What are typologies of IPA and why might they be important in mediation? ..................... 46

What happens when IPA victims are identified in mediation? ............................................. 52

Should victims of IPA be screened out or accommodated? ................................................. 53

What happens when a case has both IPA and child abuse? .................................................. 55

How many people do not have attorneys and what happens in cases without attorneys? .... 58

Is post-separation IPA a problem? ........................................................................................ 60

Is there a risk that victims will mediate agreements that are unsafe? ................................... 62

NIJ Project Goals and Research Questions: .............................................................................. 66

Goal 1: Determine whether the mediation program accurately identifies couples with

self-identified IPA and assess whether these cases are treated differently. .......................... 66

Goal 2: Assess whether mediation agreements, divorce decrees and/or parenting plans

include safety measures in cases involving self-reported IPA. ............................................. 66

Goal 3: Assess the frequency with which mediation agreements/divorce decrees are re-

litigated over time. ................................................................................................................ 66

Goal 4: Test a multivariate conceptual model using variables that are hypothesized to

affect mediation, divorce case and post-divorce outcomes (see Cascade Model Figure 16).

66

Methods......................................................................................................................................... 67

Mediation Process ..................................................................................................................... 72

Participants. ............................................................................................................................... 67

Mediators .................................................................................................................................. 75

Security at Study Site. ........................................................................................................... 75

Mediator Training in Assessing IPA..................................................................................... 75

Data. .......................................................................................................................................... 76

Mediation Data. ..................................................................................................................... 76

Divorce File Data. ................................................................................................................. 80

Area Law Enforcement Data ................................................................................................ 81

Limited Jurisdiction Court Data............................................................................................ 82

Data-Analytic Strategy for Conceptual Model (Cascade Model) ............................................. 82

Marital stressors .................................................................................................................... 84

Interpersonal Abuse (IPA) .................................................................................................... 85

Child Maltreatment ............................................................................................................... 96

Mediator Determination of IPA Present/Absent ................................................................... 96

Mediation Special Procedures ............................................................................................... 97

Mediation Agreements. ......................................................................................................... 97

Orders of Protection. ............................................................................................................. 98

Court Legal Finding of “Domestic Violence.” ..................................................................... 98

Decree Restrictions in Parenting Plans. ................................................................................ 98

Intimate Partner Violence in Mandatory Divorce Mediation

Beck, Walsh, Mechanic, Figueredo & Chen 8 2007-WG-BX-0028

Terms of Parenting Agreements. .......................................................................................... 98

Number of Hearings Post-Decree. ........................................................................................ 99

Post-Decree Calls to the Law Enforcement. ......................................................................... 99

Number of Orders Post-Decree. .......................................................................................... 100

Results ......................................................................................................................................... 101

Statement of results ................................................................................................................. 101

Overview of IPA dimensions in the sample ....................................................................... 101

Goal 1: Determine whether the mediation program accurately identifies couples with

self-identified IPA and assess whether these cases are treated differently. To do so we: . 104

Goal 2: Assess whether mediation agreements, divorce decrees and/or parenting plans

include safety measures in cases involving self-reported IPA. ........................................... 116

Goal 3: Assess the frequency with which mediation agreements/divorce decrees are re-

litigated over time. .............................................................................................................. 124

Goal 4: Test a multivariate conceptual model using variables that are hypothesized to

affect mediation, divorce case and post-divorce outcomes (see Figure 16). ...................... 133

Discussion of the Findings ...................................................................................................... 145

Conclusions and Implications ..................................................................................................... 145

Goal 1: Determine whether the mediation program accurately identifies couples with

self-identified IPA and assess whether these cases are treated differently. ........................ 147

Goal 2: Assess whether mediation agreements, divorce decrees and/or parenting plans

include safety measures in cases involving self-reported IPA. ........................................... 160

Goal 3: Assess the frequency with which mediation agreements/divorce decrees are re-

litigated over time. .............................................................................................................. 169

Goal 4: Test a multivariate conceptual model using variables that are hypothesized to

affect mediation, divorce case and post-divorce outcomes (see Figure 16). ...................... 173

(1) Provide essential training in the dynamics of IPA .................................................. 187

Recommendations for Policy, Practice and Research ............................................................. 187

(2) Use a structured, systematic approach to assessment of IPA in mediation ............ 187

(3) Automate screening measures ................................................................................. 187

(4) Assess Mediation special procedures to accommodate victims ............................. 188

(5) Acknowledge the limitations of the mediation process .......................................... 189

(6) Investigate hybrid mediation/arbitration mediation interventions .......................... 189

(7) Encourage legal findings of “domestic violence” in appropriate cases .................. 190

(8) Assess outcomes for children directly and prospectively ....................................... 190

(9) Assess the effectiveness of court-based programs for pre- and post-divorce “frequent

flyers” 190

Limitations of the research. ..................................................................................................... 192

References ................................................................................................................................... 196

Implications for Future Research. ........................................................................................... 195

Dissemination of Research Findings .......................................................................................... 209

Publications ............................................................................................................................. 209

Publications in Progress and Submitted .................................................................................. 209

Attachments ................................................................................................................................ 213

Attachment A: Mediation Case File Data ............................................................................... 214

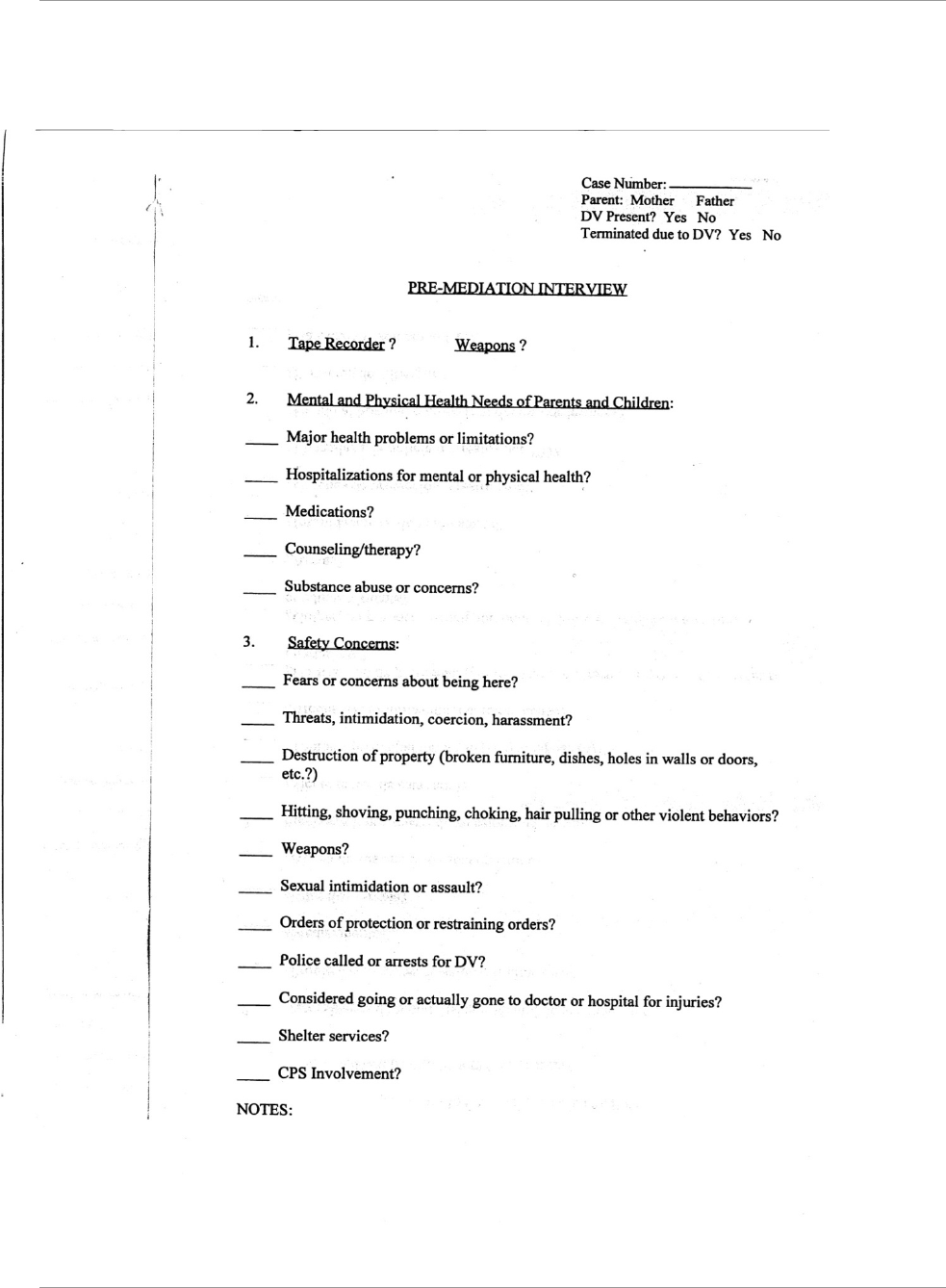

Attachment B: Premediation Interview Form (PMI) ............................................................ 229

Attachment C: Relationship Behavior Rating Scale (RBRS) ............................................... 229

Intimate Partner Violence in Mandatory Divorce Mediation

Beck, Walsh, Mechanic, Figueredo & Chen 9 2007-WG-BX-0028

Attachment D: Superior Court Divorce File Data ................................................................. 231

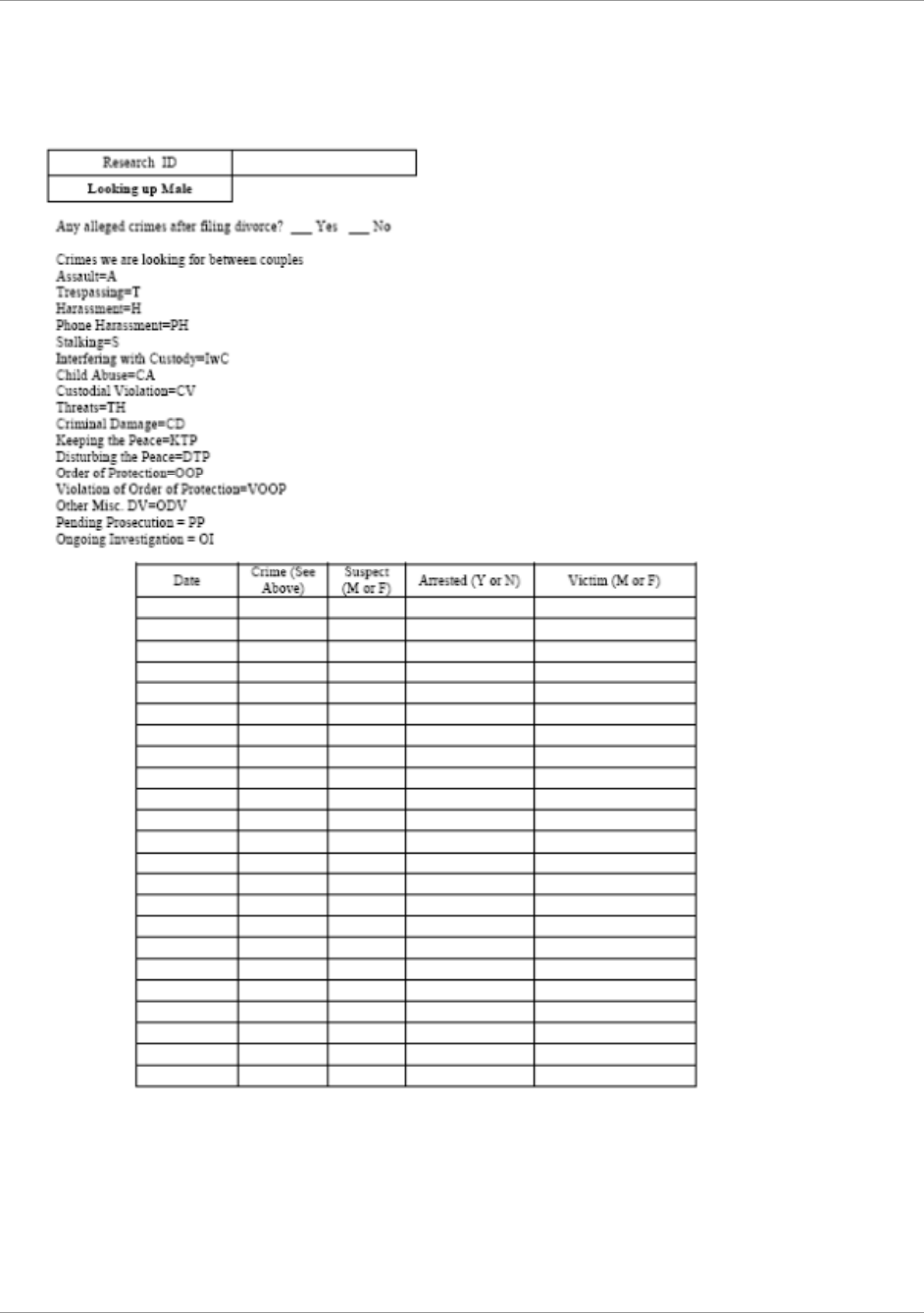

Attachment E: Data Collection Sheet for Law Enforcement Database .................................. 237

List of Figures

Figure 1: Case Flow Chart

Figure 2: Latent Classes and Mean of Continuous Measure of IPA

Figure 3: Latent Classes and Mean of Continuous Measure of IPA --No Coercive Controlling

Behaviors Included in Continuous Measure of IPA

Figure 4: Cases Identified by Mediator as IPA Present/Absent.

Figure 5: Reports of at Least One Incident of Either Threats of and/or Escalated Physical

Violence or Sexual Intimidation/Coercion/Assault in the Preceding 12 Months by

Mediator Identified/Not Identified IPV

Figure 6: T-scores for Client-Reported IPA by Whether IPA was identified by the Mediator

Figure 7: Relationship Among Calls to Law Enforcement at Different Time Periods

Figure 8: Orders of Protection by Client- or Mediator-Identified IPA

Figure 9: Mediation Accommodations Reported IPA

Figure 10: Mediation Agreement Type by T-score Mean of IPA

Figure 11: Legal Finding of Domestic Violence and Reported IPA

Figure 12: Custody Awards in Divorce Decrees by Reported IPA

Figure 13: Percentage of Post-Decree Hearings by Outcome of Mediation

Figure 14: Percentage of Post-Decree Orders by Outcome of Mediation

Figure 15: Percentage of Post-Decree Stipulations by Outcome of Mediation

Figure 16: Cascade Model

List of Tables

Table 1: Participant Demographics

Table 2: Constructs, Measured Variables, and Data Sources for Cascade Model

Table 3: Reliability Estimates for IPA Categories

Table 4: Correlations of Standardized IPA Subtypes and IPA Common Factor Score

Table 5: Raw Means and Standard Deviations of IPA reports by IPA Subscales

Table 6: Calls to Law Enforcement.

Table 7: Time Periods for Calls to Law Enforcement

Table 8: Correlation of Calls to Law Enforcement with Client-Reported IPA

Table 9: Average Calls to Law Enforcement by Whether the Mediator Identified IPA

Table 10: Orders or Protection by Mediator-Identified IPA

Table 11: Comparisons of Mediation Agreement by IPA T-Score

Table 12: Restrictions Placed on Parents or Parenting by Terms of Agreement

Table 13: Parenting Agreements: Physical and Legal Custody

Table 14: Frequencies of Decree Restrictions by Type

Table 15: Post-decree hearings, orders and stipulations

Intimate Partner Violence in Mandatory Divorce Mediation

Beck, Walsh, Mechanic, Figueredo & Chen 10 2007-WG-BX-0028

Table 16: Mean Differences among Post-Decree Hearings and Orders by Mediator-Identified

IPA

Intimate Partner Violence in Mandatory Divorce Mediation

Beck, Walsh, Mechanic, Figueredo & Chen 11 2007-WG-BX-0028

Executive Summary

Introduction

Mediation became popular in the United States in the 1980s as an alternative to the

typical dual attorney, adversarial model of negotiating custody and parenting time issues divorce

cases. It quickly gained tremendous popularity and now exists in some form (legally mandated,

at judicial discretion, or voluntary) in nearly every state in the United States as well as in Britain,

Canada and Australia.

There have been three decades of scholarly research on numerous aspects of divorce

mediation; however there remains no comprehensive understanding of the short- and long-term

outcomes for couples who are legally ordered to mediation and who use court-connected

programs to do so. In the case of couples alleging intimate partner abuse (IPA), even less is

known (Beck & Sales, 2001; Salem, 2009). This study was funded by NIJ to investigate a

naturalistic (as opposed to tightly controlled experimental) process and systematically document

actual percentages of IPA in mediation; to systematically analyze mediator practices addressing

IPA cases; and to assess mediation outcomes, divorce outcomes and post-decree outcomes for

both IPA and non-IPA cases.

Study Goals

The overall goal of this study was to enhance the effectiveness of screening and

management of cases with IPA by providing empirical data concerning outcomes in these cases

to public policy-makers within state legislatures, court systems, mediation programs and

professional organizations. Results of this study can be used to design targeted research to

answer specific questions arising from the study and to begin developing policies and practices

Intimate Partner Violence in Mandatory Divorce Mediation

Beck, Walsh, Mechanic, Figueredo & Chen 12 2007-WG-BX-0028

that will enhance the short- and long-term safety of IPA victims and their violence-exposed

children. The specific study goals were:

Goal 1: Determine whether the mediation program accurately identifies couples with

self-identified IPA and assess whether these cases are treated differently.

Goal 2: Assess whether mediation agreements, divorce decrees and/or parenting plans

include safety measures in cases involving self-reported IPA.

Goal 3: Assess the frequency with which mediation agreements/divorce decrees are re-

litigated over time.

Goal 4: Test a multivariate conceptual model using variables that are hypothesized to

affect mediation, divorce case and post-divorce outcomes (see Cascade Model Figure 16).

Study Methods

To accomplish these goals we conducted a study in Pima County, Arizona which linked

archival data from two court databases and two law enforcement databases for a large matched

sample (N=965) of couples involved in the divorce process. We first linked data produced in the

naturalistic clinical interviews used to screen parents for marital stressors and IPA in custody and

parenting time (i.e., weekly visitation, holidays and vacations) mediation to questionnaire data

also measuring specific IPA-related behaviors. We then linked this IPA data to the mediator’s

decisions concerning (1) whether to identify a case as having IPA or not; (2) whether to proceed

in mediation or to screen out IPA-identified cases; and (3) whether to provide special procedural

accommodations for IPA-identified cases.

We then linked the IPA data and mediator decision data to mediation outcome data from

in mediation case files and to outcomes in final divorce decrees and parenting plans found in

Superior Court divorce files. We then linked these pre-divorce and divorce data to post-divorce,

longitudinal data concerning re-litigation of divorce-related issues in Superior Court and

longitudinal data concerning contacts with area law enforcement.

Intimate Partner Violence in Mandatory Divorce Mediation

Beck, Walsh, Mechanic, Figueredo & Chen 13 2007-WG-BX-0028

Based on previous work concerning IPA screening in mediation (Administrative Office

of the Courts [California], 2010, Ellis, 2006; Ellis & Stuckless, 2008; Newmark et al., 1995;

Pearson, 1997), we believe that mediation screening for IPA at the study site far exceeds the

standard for mediator screening practices employed in most jurisdictions. Screening at this site

included both a semi-structured clinical interview with each parent individually and a 41-item

behaviorally specific questionnaire covering a wide range of IPA-related behaviors. Therefore,

this study represents a “best case scenario” for screening practices and responding to IPA in the

mediation context at the time the study was conducted and likely currently as well.

Results and Conclusions

Goal 1: Determine whether the mediation program accurately identifies couples with

self-identified IPA and assess whether these cases are treated differently.

To put the findings regarding accurate identification by mediators in perspective, we first

assessed the total percentage and types of IPA reported in the sample and important demographic

differences between fathers and mothers.

A tremendous amount of IPA was reported by both parents in mediation. From the

data obtained in screening interviews with each parent individually, mediators identified 59%

(N=569) cases as having IPA. Analyzing data from the 41-item IPA screening questionnaire of

behaviorally-specific questions assessing a range of IPA-related behaviors that occurred in the

past 12 months, responses were categorized into the following subscale dimensions:

psychological abuse, coercive controlling behaviors, physical abuse, threatened and escalated

physical violence, and sexual intimidation/coercion/assault. Analysis of this client self-reported

data indicated that: 97% of both mothers and fathers reported at least one incident of

psychological abuse, coercive controlling behaviors; 58% of the mothers and 54% of the fathers

Intimate Partner Violence in Mandatory Divorce Mediation

Beck, Walsh, Mechanic, Figueredo & Chen 14 2007-WG-BX-0028

reported at least one incident of physical abuse; 62% of the mothers and 50% of the fathers

reported at least one incident of threatened and escalated physical violence; 56% of the mothers

and 30% of the fathers reported at least one incident of sexual intimidation/coercion/assault.

There were statistically significant differences between mothers’ and fathers’ reports on all

subscale dimensions with mothers reporting higher levels, except on the physical abuse (lower

levels of pushing and shoving) dimension where there was no difference between the parents’

reports.

Important disparities exist in incomes between divorcing parents. Upon entering

mediation, the mothers’ incomes in this study were approximately half of the fathers’ incomes.

One potential interpretation of this finding is that that mediation about custody and child support

is not an “even playing field” for both parties even before the issue of abuse is raised. This

marked sex difference in income graphically illustrates a highly gendered pattern in child care

and the patterns reflected in custody arrangements following separation. These patterns are often

inaccurately attributed to “gender bias” against men as opposed to reflecting the patterns

established in the family prior to divorce.

IPA does not end at separation and divorce. An important finding that is well

supported by the extant research on separation and divorce is that for some couples IPA did not

stop at separation or divorce. For a minority of couples, calls to police, orders of protection, and

court hearings regarding IPA were reported after separation and after the divorce was finalized.

Again, it is important that any agreements between the couples address the risk of continued

IPA.

An analysis of couple-level IPA data produced a five class typology; four classes

represented a clear victim and perpetrator.

Intimate Partner Violence in Mandatory Divorce Mediation

Beck, Walsh, Mechanic, Figueredo & Chen 15 2007-WG-BX-0028

With the assistance of our colleague Dr. Edward Anderson from the University of Texas

at Austin, we investigated whether the data in this study would produce couple-level types of

IPA similar to those proposed in by Kelly and Johnson (2008) for this population. Extremely

simple definitions of Kelly and Johnson’s typology are as follows:

1. Coercive Controlling Violence (male perpetrated battering of female partner)

2. Violent Resistance (female partner resisting a coercive controlling male perpetrator)

3. Situational Couple Violence (symmetric low level physical abuse)

4. Separation-Instigated Violence (no prior history; either partner perpetrating)

5. Mutual Violent Control (both partners perpetrate coercive controlling violence)

Because the data in this study was extant archival court records, the long-term patterns of

IPA within couples could not be determined. Therefore, the categories of violent resistance and

separation-instigated violence were not able to be adequately assessed. We conducted a latent

class analysis of the 41-item, behaviorally specific questionnaire data using a pooled mother and

father mean (as opposed to gender-specific means) so that unit weights were equivalent across

parents. This analysis produced five types. Keeping with the definitions above and beginning

with the group reporting the lowest levels of IPA to the highest levels of IPA, the types were as

follows:

1. Mutually low (or no) IPA.

2. Lower Level Coercive Controlling Violence—father perpetrator (mother reports)

3. Coercive Controlling Violence—mother perpetrator (father reports)

4. Coercive Controlling Violence—father perpetrator (mother reports)

5. Mutual Violent Control—(father perpetrator (mother reports); mother perpetrator

(father reports).

A detailed explanation of these types is provided within the text of the report.

Mediators identified many, but not all, client self-identified cases of IPA. Mediators

used clinical judgment to sort cases and did not designate every case that reports any level of

IPA as one with IPA. However, there were a small number of cases that were classified as high

Intimate Partner Violence in Mandatory Divorce Mediation

Beck, Walsh, Mechanic, Figueredo & Chen 16 2007-WG-BX-0028

level IPA that were not identified by the mediators as such. One third of the couples classified as

non-IPA by the mediator reported at least one incident of threatened and escalated violence or

sexual intimidation/coercion/assault. For those fathers and mothers completing the behaviorally

specific questionnaire and combining all dimensions for a total score for each parent, 49 mothers

(n=887; 6%) and 37 (n=866; 4%) fathers reported victimization that was frequent and/or severe

enough to categorize their abuse as two standard deviations above the sample mean. Mediators

classified as IPA all of these cases as having IPA except six mother victim cases and two father

victim cases. Basing classification of cases on a nonsystematic, semi-structured clinical

interview data may not be the most effective method of assessing IPA. Research is mixed

concerning whether people find it easier to report IPA behavior in face-to-face interviews or on

written questionnaires. For the present, a prudent method may be to use both methods.

Even using both methods of assessment, mediators must be well trained in identifying

IPA to be in a position to make very difficult, nuanced decisions concerning proceeding,

accommodating or screening cases out of mediation.

Cases are rarely screened out of mediation. Seven percent of cases were screened out

of mediation. There was a statistically significant difference in mother but not father total IPA

scores of those screened out and those that remained in mediation. For those parents with IPA

scores two standard deviations above the mean, 25% of the mothers and 9% of the fathers were

screened out.

Mediators must strike a delicate balance between empowering parents to represent their

own interests in mediation sessions and determining the best method of protecting victims and

violence-exposed children. The choice is simple if the victim does not want to proceed; the

decision becomes more complex if the victim wants to move ahead. Allowing a victim a chance

Intimate Partner Violence in Mandatory Divorce Mediation

Beck, Walsh, Mechanic, Figueredo & Chen 17 2007-WG-BX-0028

to proceed gives the victim a safe forum to have a voice with her or his abuser and provides the

mediator a chance to observe the dynamics of the couple and to evaluate the fairness of the

process. And, screening cases out of mediation immediately after the individual interview may

be risky. The mediator terminating mediation after the initial session may better protect victims

than screening them out initially.

Special mediation procedures (safety accommodations) were provided most often

for parents who telephoned the mediation service expressing safety concerns or requesting

accommodations. Accommodations to the mediation procedure included: parents required to

leave at separate times; security escort to car; separate waiting rooms; screening on different

days; shuttle mediation, and an experienced team of mediators. Approximately 19% of the

couples were provided at least one of these procedural accommodations. Accommodations were

provided for couples with higher levels of IPA; however, fewer than half of the couples reporting

IPA at levels two standard deviations above the mean were provided accommodations.

Mediators were more likely to provide accommodations if they had identified IPA present (28%)

versus absent (6%). Mediators were statistically significantly more likely to provide

accommodations or to screen the couple out if a parent phoned the mediation service ahead of

time with concerns about mediating or requesting accommodations (84%; N=31).

There are important issues in considering these findings. First, screening for IPA was

ongoing throughout the mediation and if it appeared accommodations were in order they were

provided. Second, the data concerning accommodations likely represents a serious underestimate

of actual accommodations provided. There was no systematic documentation of accommodations

for the study site kept in mediation case files. And third, advocates working with victims

involved in the divorce process should remind their clients to telephone the mediation service if

Intimate Partner Violence in Mandatory Divorce Mediation

Beck, Walsh, Mechanic, Figueredo & Chen 18 2007-WG-BX-0028

they have concerns about mediating. Mediators in this study were extremely responsive to these

calls. However, even without calls, accommodations were consistently provided.

Calls to area law enforcement and orders of protection are common. Couples in the

study entered mediation between May, 1998 and October, 2000 and data was collected from area

law enforcement for these cases beginning two years prior to filing for divorce up February,

2007. In nearly 40% of couples, at least one parent telephoned area law enforcement at least once

during the study period. The range in the number of calls was 0-21. In addition, 42% of the

couples in the study reported receiving an order of protection at some point in the relationship.

There were high levels of agreement between parents concerning whether law enforcement had

been called, whether arrests had been made or whether orders of protection were in place at the

time. Those couples with the highest number of calls to law enforcement fell into the mediator

IPA-identified group as did those couples with orders of protection.

Data concerning calls to area law enforcement also likely represent a serious

underestimate of the actual calls made by the couples. Data was collected from the two law

enforcement agencies serving the location directly surrounding the study site. Any calls placed to

agencies beyond these were not included. In addition, only calls placed within the limited study

period were counted.

Goal 2: Assess whether mediation agreements, divorce decrees and/or parenting plans

include safety measures in cases involving self-reported IPA.

Levels of reported IPA influenced whether couple were likely to reach agreements.

In mediation, 56% of the couples reached a full agreement on all issues (legal decision-making

custody; physical custody and residential arrangements, holiday and vacation schedules); 22%

reached a partial agreements, and 22% failed to reach an agreement. Those couples who failed to

Intimate Partner Violence in Mandatory Divorce Mediation

Beck, Walsh, Mechanic, Figueredo & Chen 19 2007-WG-BX-0028

reach agreement had the highest levels of reported IPA, followed by those that reached partial

agreements. Those who reached full agreement reported the lowest IPA scores.

Mediation agreements and divorce decrees rarely have restrictions on parenting

(e.g., supervised parenting time) or on contact between parents (e.g., written contact only).

Of the couples who reached any kind of mediation agreement (partial or full) in mediation, 6%

included some type of restriction on contact between parents or restriction on parenting. Cases

that had restrictions reported higher levels of IPA. However, for those cases with the highest

levels of IPA reported (two standard deviations above the mean) there were no restrictions

placed on 9 cases (out of 19 cases identified in that range). In terms of decrees, 12% contained

restrictions. Cases with restrictions in place tended to have higher levels of reported IPA. In

addition, a greater percentage of cases at the highest levels of IPA (two standard deviations or

higher) had restrictions, as compared to those at the lower levels.

While restrictions in mediation agreements were rare, it appears that victims with the

highest levels of IPA are typically leaving mediation without agreements. These couples returned

to court and obtained restrictions at a much higher rate than those found in couples who reached

mediation agreements. There are two important issues that relate to restrictions. First, it is

important for mediators, advocates and lawyers working with victims to remind victims that, in

most jurisdictions, they are required to attend the orientation screening sessions and negotiate in

good faith, but they are not required to reach an agreement in mediation. And second, the

limitations of the mediation process must understood and acknowledged. Mediators are not

judges and cannot require abusers agree to or abide by restrictions on contact between parents or

restrictions on parenting even if it would be in the best interests of the children to do so. If the

goal is having appropriate restrictions in mediation agreements for couples with IPA then use of

Intimate Partner Violence in Mandatory Divorce Mediation

Beck, Walsh, Mechanic, Figueredo & Chen 20 2007-WG-BX-0028

other processes are likely necessary, such as a hybrid mediation/arbitration intervention which

provides the arbitrator with legal authority and control over the terms of agreements.

Investigations of hybrid mediation/arbitration interventions have been conducted over the

past two decades (Colon, Moon, & Yee Ng, 2002; Loschelder, & Trotschel, 2010;

McGullicuddy, Welton, & Pruitt, 1987; Ross, Brantmeier, & Ciriacks, 2002). The essential

elements of these interventions are that clients to a mediation attempt to mediate an agreement. If

the they do not reach an agreement, the mediator then becomes an arbitrator and issues a binding

decision (med/arb(same)) or the mediators steps aside and a new person becomes the arbitrator

and issues a binding decision (med/arb(diff)). These models were empirically investigated in a

community mediation center (McGillicuddy et al., 1987). When compared to traditional

mediation (if no agreement clients return to court) and med/arb(diff), mediation clients in the

med/arb(same) condition engaged in more problem solving and were less hostile and

competitive. The important aspect of these interventions in the high-IPA divorce mediation

context is that if a couple is determined to have IPA in the relationship and the abuser will not

agree to safety precautions in the mediation agreement, the arbitrator has the authority to issue a

binding decision which includes these terms. Prior to adoption of these models it is extremely

important that they be carefully empirically investigated and that the safety of victims in the

short- and long-term are the uppermost consideration.

Legal findings of “domestic violence” were rare. Only 2% of the cases in the sample

had a formal legal finding labeled domestic violence in the divorce file. Couples with a legal

finding of domestic violence reported higher overall IPA scores compared to those who did not

have the legal finding. However, among couples reporting the highest levels of IPA (greater than

two standard deviations above the mean), only five couples had this finding. Because it is

Intimate Partner Violence in Mandatory Divorce Mediation

Beck, Walsh, Mechanic, Figueredo & Chen 21 2007-WG-BX-0028

necessary for there to be a clear victim and perpetrator, none of the seven couples who reported

high mutual IPA received a legal finding of domestic violence. It is unclear why this legal

remedy is not being used more frequently. It could be because the evidence required to meet the

legal burden is too difficult to obtain or is too risky for the victims to pursue.

The most common parenting agreement in divorce decrees, regardless of reported

level of IPA, was mother as the primary physical custodian with joint legal custody.

Mothers were awarded primary custody (physical and/or legal) in 70% of the cases; fathers were

awarded primary custody in 9% of the cases and joint custody was awarded in 21% of the cases.

In comparing decree outcomes for those who reached full agreement in mediation to those who

failed to reach agreement in mediation, mothers in full agreement cases were awarded primary

custody in 69% (full agreement) versus 71% (no agreement ) cases. Fathers were awarded

primary custody in 8% (full agreement) versus 11% (no agreement) cases. Joint custody was

awarded in 23% (full agreement) versus 18% (no agreement) cases. The lowest level of reported

IPA was found in joint custody cases.

Interestingly, those couples falling in the Mutually Violent Control type for which

decrees were entered (N=26), mothers were awarded primary custody in 22 cases (85%); joint

custody was awarded in three cases (11%); and, fathers were awarded primary physical custody

and/or legal custody in one case (4%).

Goal 3: Assess the frequency with which mediation agreements/divorce decrees are

re-litigated over time.

The majority of parents return to court to re-litigate divorce issues; however, there

is a small subset of “frequent flyers.” Sixty-two percent of the couples returned to court for at

least one hearing after the divorce was finalized. The range in the number of hearings was 0-31

Intimate Partner Violence in Mandatory Divorce Mediation

Beck, Walsh, Mechanic, Figueredo & Chen 22 2007-WG-BX-0028

hearings. Approximately half of those couples who did return returned between 1-5 times (52%).

There was a subset of couples (4.5%; N=31 who accounted for 31% of the total number of

hearings requested in the sample. In the last decade, court-based programs have been developed

targeting this group of couples. It is important that continued efforts to validate the effectiveness

of these programs be supported.

Parents reaching agreement in mediation are significantly less significantly likely to

re-litigate divorce-related issues post-divorce. Those couples who reached full agreement in

mediation were significantly less likely to return to court to re-litigate aspects of their divorce.

This finding is particularly important for policy-makers considering whether to develop (or fund)

mediation programs. In this study, well-trained mediators were given a wide latitude to provide

the number of sessions necessary for couples to successfully negotiate an agreement, thus using

fewer court resources post-divorce.

Goal 4 Results: Test a multivariate conceptual model using variables that are

hypothesized to affect mediation, divorce case and post-divorce outcomes (see Cascade

Model Figure 16

To better understand the dynamic nature of the divorce process and the many interrelated

variables, we used a multivariate analytic approach. We began by aggregating theoretically

relevant constructs across an entire system to guide our inquiry into those that lead to outcomes

associated with mediation, the divorce and the post-divorce legal processes. We then created a

theoretically-specified causal order for the constructs and then ran a series of multiple regression

models in the context of a Cascade Model (Figure 16). Specific hypotheses were tested relating

to the relationship between the constructs, which were categorized into three temporally related

sets of variables. The first set included variables that occurred prior to mediation (marital

Intimate Partner Violence in Mandatory Divorce Mediation

Beck, Walsh, Mechanic, Figueredo & Chen 23 2007-WG-BX-0028

stressors, father and mother perpetrated coercive controlling behaviors and IPA); the next set of

variables was those that occurred as a result of mediation (mediator identification of IPA,

mediator providing special procedures/accommodations, and whether an agreement was

reached); the third set of variables included those that occurred as a result of the final divorce

(court finding of IPA, restrictions in decree on the abusing parent, order of protection, child

maltreatment and custody decree favoring mothers). The final set of variables related to post-

decree outcomes that were possible after the divorce process (post decree hearings, orders and

calls to law enforcement). Selected findings that extend findings noted above will be reviewed

below as the model.

Decades of research have documented the emotional chaos and financial hardship

experienced by families going through a divorce. Results indicate that marital stress influenced

mothers’ and fathers’ perpetration of IPA; however, it also influences fathers’ use of IPA and

court orders placing restrictions on contact between parents and on parenting in divorce decrees.

Marital stressors negatively influenced custody agreements favoring mothers. Although the

majority of mothers are awarded primary legal and/or physical custody, when mothers’ marital

stressors are higher, the courts appear to respond by more frequently awarding fathers custody.

IPA is defined as the mean unit weighted total scores for reported physical abuse,

threatened and escalated physical violence; sexual intimidation/coercion/ assault. IPA

influenced many constructs in the model. Fathers’ and mothers’ perpetration of IPA influenced

the mediator’s identification of a case as having IPA; however, beyond these relationships,

mothers’ and fathers’ IPA influenced downstream constructs in different ways.

When fathers’ perpetrate higher levels of IPA, the couple is less likely to reach an

agreement in mediation, and .there is a significantly greater chance that an order of protection

Intimate Partner Violence in Mandatory Divorce Mediation

Beck, Walsh, Mechanic, Figueredo & Chen 24 2007-WG-BX-0028

will be issued. There is also a greater chance that restrictions will be included in divorce decrees

and that custody agreements will favor mothers. When mothers perpetrate higher levels of IPA,

courts are more likely to issue a legal finding of domestic violence in the case, and there will

likely an order of protection and child maltreatment reports in the case. It appears that in mother-

perpetrator cases, fathers take the legal step of obtaining a legal finding of domestic violence and

orders of protection for himself and the children.

Child maltreatment also emerged with interesting relationships to mothers’ perpetration

of coercive controlling behaviors, IPA, divorce and post-divorce outcomes. It appears that when

mothers’ perpetration of coercive controlling behaviors is higher fewer reports of child

maltreatment are made. However, mothers’ perpetration of IPA is associated with high reports of

child maltreatment. The chance for a custody award favoring the mother is then significantly

reduced and there are more frequent post-divorce calls to law enforcement.

Coercive Controlling Behaviors emerged as an important influence on downstream

divorce and post-divorce constructs both directly and indirectly through IPA total scores. In a

prior analysis of this data we hypothesized, and then confirmed using structural equations

modeling, that control is the motivator for other dimensions of IPA (Tanha et al., 2009). In other

words, when coercive controlling behaviors fail to control the other parent, physical dimensions

of IPA (physical abuse, threatened and escalated physical violence; sexual

intimidation/coercion/ assault) are then enlisted. Thus, it appears that when mothers’ and fathers’

attempts to control the other parent failed, both tended to escalate into other, more severe forms

of IPA.

However, looking at the relationships of coercive controlling behaviors to other

important variables, the use of coercive controlling behaviors by mothers against fathers

Intimate Partner Violence in Mandatory Divorce Mediation

Beck, Walsh, Mechanic, Figueredo & Chen 25 2007-WG-BX-0028

additionally influenced other constructs in the model. The higher the levels of mothers’ coercive

controlling behaviors, the lower the chance of a child maltreatment report, order of protection or

an agreement in mediation.

In summary, one reason for conflicting findings with respect to screening,

documentation, triage, and monitoring of IPA cases in mediation in the literature is likely the

lack of consensus on how to identify IPA; what to do about it when it is detected; and agency

policy differences on how to handle IPA cases. The results of this study provide strong

empirical support for previous estimates that most couples attending divorce mediation report

some level of IPA. Given that couples mandated to mediation are there precisely because they

cannot agree on significant aspects of the divorce, this result was expected. Few mothers and

fathers reported no IPA of any kind (only four couples reported that there were no incidents of

any sort of IPA in the preceding 12 months prior to mediation). The parents reported at least

some form of IPA occurred in over 90% of the cases and two thirds of the couples reported that

either or both partners utilized outside agency involvement from police, shelters, courts, or

hospitals to handle the IPA. These figures represent a tremendous amount of IPA in couples

mandated to attend mediation and that the level was likely more serious that “common couple

violence” identified in previous national random sample surveys (Kelly & Johnson, 2008).

Limitations

Archival data from court records and area law enforcement records are an unobtrusive

and efficient means of gathering important data. There are, however, limitations to using these

type of official records to collect data. The most important limitation is that the data available is

limited to what the records contain. Records are often incomplete, files can be misplaced and

documents intended for inclusion in the files can be lost or misfiled. The quality of the records is

Intimate Partner Violence in Mandatory Divorce Mediation

Beck, Walsh, Mechanic, Figueredo & Chen 26 2007-WG-BX-0028

not under the control of the researcher (Jewkes, 2008). Access to the records can be limited and

refusal to allow access or provide certain portions of the data can occur. More specific to this

study, these data are from only divorcing couples who had disputes about custody and/or

parenting time of their children from one jurisdiction and one court-sponsored, free mediation

program. There is no way to empirically identify which couples chose this program over private,

fee-for-service mediator or mediation program. It is likely that those couples with the most

disposable income did so. Because this is a study specifically of divorcing couples with children

referred to mediation and not all divorcing couples, couples without children and/or those

couples with children but who were able to work out agreements concerning custody and/or

parenting time were also not included in this study. Because of the specifics of this sample, there

are limits to the generalizability of the findings.

It is important to note several issues relevant to the screening procedure and the use of the

screening forms by the mediators. The semi-structured interview data used in this study represent

the individual determinations by mediators as to what seemed important enough to note in order

for them to determine the best course of action for the case. In addition, the behaviorally-specific

questionnaire included in the file (the RBRS) assessed IPA in the prior 12 months only. Thus, the

RBRS did not capture the full extent of IPA that may have existed in the entire relationship nor

did it document ongoing IPA ongoing in the relationship. The RBRS also did not assess for who

the primary or predominant aggressor was or the relationship context in which any of these

behaviors occurred. Thus, whether the acts were self-defense or abusive/violent acts cannot be

distinguished. Future research needs to include structured, standardized, comprehensive

assessment measures of IPA in addition to in-depth interviews with the clients to gain a full

understanding of the the specific context and impact of the violence in the family. It is extremely

Intimate Partner Violence in Mandatory Divorce Mediation

Beck, Walsh, Mechanic, Figueredo & Chen 27 2007-WG-BX-0028

important for future research that a clear picture of the history of IPA in the relationship can be

understood and the victim and abuser can be correctly identified so that the court system can

respond appropriately to protect the victim and the violence-exposed children.

As noted above, the data in this study concerning accommodations provided to couples in

mediation is likely a serious underestimates of the actual number of accommodations provided.

This study was a naturalistic evaluation of one county’s practices therefore data used in this

study was not designed for specifically research purposes but instead to conduct day-to-day

operations in the mediation program. While some accommodations provided clients were

documented, not all of the accommodations were clearly documented in the files. There has been

two decades of scholarly discussion of the possibility of special procedures used in mediation to

accommodate couples with IPA, but there has yet been no systematic empirical research

investigating what accommodations are provided and when they are provided and why they are

provided. This study represents one of the first attempts to document the use of special

accommodations for couples with IPA. Future prospective research is needed which carefully

defines special procedures/accommodations, assigns couples to specific accommodations based

on hypothesized needs, then documents defined outcomes associated with the couples in the

different accommodation groups (Ellis, 2008). This research would be helpful in understanding

how accommodations affect case processing and case outcomes.

Data in this study concerning law enforcement is also likely a serious underestimate of all

the calls placed to law enforcement by couples in the study. Because only local area law

enforcement (police and sheriff) calls were gathered in this study, calls placed to jurisdictions

outside the local area were not captured.

Intimate Partner Violence in Mandatory Divorce Mediation

Beck, Walsh, Mechanic, Figueredo & Chen 28 2007-WG-BX-0028

Despite the limitations of this naturalistic study, these data are unprecedented in the field

of divorce mediation research. To date, virtually all of the published samples used to study

mediation included small samples, limited data, or low response rates (Beck & Sales, 2001). In

this study, the sample included all parents (N=965 couples) who were disputing custody and

parenting time issues in a pending divorce and were mandated by a local court rule to attend

mediation during the targeted period and did so for a first-time mediation through a court-

sponsored, free mediation program.

Recommendations for Research, Policy and Practice

(1) Provide essential training in the dynamics of IPA

Mediators, judges and court staff working directly with potential victims of IPA need to

be well trained in the dynamics of IPA and how it may manifest the context of a divorce.

(2) Use a structured, systematic approach to assessment of IPA in mediation

Using a structured, systematic, multi-method approach is likely to be considerably more

effective than using only a semi-structured clinical interview in reducing the rate of false

negatives in the IPA screening process. We are strongly recommending that mediators adopt a

standardized approach to administration of both semi-structured clinical interviews and

standardized questionnaires and ask all questions about IPA of all parents.

Mediation practitioners, scholars and violence experts also need to work together to

continue developing a more reliable, valid, approach to screening for all dimensions of IPA in

mediation including stalking. Because coercive controlling behaviors were important indicators

separate from the other dimensions of IPA, continued focus on developing adequate screening

measures for both mothers and fathers is needed.

Intimate Partner Violence in Mandatory Divorce Mediation

Beck, Walsh, Mechanic, Figueredo & Chen 29 2007-WG-BX-0028

(3) Automate screening measures

Development of an automated version of a comprehensive IPA screening measure that

quickly combines data from both members of a couple for mediator review and decision-making

is critical for an accurate assessment of IPA. Although assessment can be automated relatively

easily, the complex decisions mediators must make for a particular couple in determining

whether to move forward with mediation or not, or to provide an accommodation or not, requires

careful thought and analysis of the benefits and risks in consultation with the reported victim.

(4) Assess Mediation special procedures to accommodate victims

Prospective research using systematic and structured assessment of IPA which clearly

documents the reasons for dispositions of cases with documented IPA histories is needed so that

effective policies to screen clients out or provide accommodations can be developed. An

accommodation which might be helpful to empirically investigate for reported victims of IPA

wishing to continue in mediation is for mediators to pre-arrange with the victim a sign (e.g., hand

signal or word) that the victim can use in the event the she or he feels unsafe or afraid. If used the

mediator will know to stop and possibly caucus with the parents individually to insure the victim

wishes to continue. Some abusers convey threats only the victim will understand and it is

important for a victim to be able to signal a mediator when this occurs. Perhaps researchers

working with practitioners can design a study where mediators are included in developing a

standardized set of accommodation practices along with hypotheses that identify which

accommodations are best implemented in cases involving different types of IPA. Carefully

defined and collected outcomes can then measure the effectiveness of the accommodations

provided, thereby empirically investigating if the process can be improved and appropriate

accommodations instituted across cases.

Intimate Partner Violence in Mandatory Divorce Mediation

Beck, Walsh, Mechanic, Figueredo & Chen 30 2007-WG-BX-0028

Mediation program personnel, lawyers and advocates working with potential victims

should strongly encourage clients who are concerned about IPA or who want specific

accommodations in the mediation process to call and request such accommodations or express

concerns about mediating.

(5) Acknowledge the limitations of the mediation process

Mediators are not judges and cannot order that certain conditions to be included in

agreements (such as protections for children or restrictions on contact between parents) or that

the conditions be followed even if such requirements would be in the best interests of the

children or the adults. In the majority of jurisdictions across the United States, mediators instead

facilitate negotiations between parents and each parent has a right to decide what they will and

will not agree to. If both parents do not agree to a specific condition, it will not be included in

any resulting agreement. If parents do not agree on any issues then no parenting agreement will

result. Holding mediators and mediation programs responsible for parenting agreements, freely

negotiated between the parties, that do not include safety precautions flies in the face of what

mediation in this and many other jurisdictions are designed to accomplish. If a mediator believes

that one of the parties cannot adequately represent their interests or the agreement negotiated

between the parents will not be in the best interests of the child[ren] is terminate mediation, the

resource the mediator has is to terminate mediation without an agreement. This decision is

difficult, complex and must be made carefully and in consultation with the party having trouble

representing her or his interests.

(6) Investigate hybrid mediation/arbitration mediation interventions

If policy-makers wish to ensure that couples with IPA negotiate mediation agreements

which include safety restrictions, they must consider empirically investigating a separate process

Intimate Partner Violence in Mandatory Divorce Mediation

Beck, Walsh, Mechanic, Figueredo & Chen 31 2007-WG-BX-0028

for these couples. The hybrid mediation/arbitration intervention may be particularly important to

empirically investigate with pro se couples with high IPA. Currently, victims without legal

representation who are unable to negotiate safe parenting plans in mediation currently must

return to court and present her or his case to the judge.

(7) Encourage legal findings of “domestic violence” in appropriate cases

The results of this study indicate that a parent with a specific legal finding of domestic

violence in their case is more likely to have safety restrictions on contact between abuser and

victim and on parenting (e.g., orders of protection; orders restricting method of contact between

parents; neutral exchanges of the children at a specific public location, a family member’s home,

or a judicially approved service provider) in the divorce decrees. Lawyers, advocates for victims

and mediators should carefully consider, in consultation with victims, recommending that

victims obtain court orders with legal findings of domestic violence. This legal finding also

provides important information to subsequent judges assigned to the case.

(8) Assess outcomes for children directly and prospectively

Children are often caught in the cross-fire of parental IPA and so the co-occurrence of

IPA with child maltreatment is high. Broader assessment and evaluation of child maltreatment

and IPA (looking beyond physical forms of both) is essential to truly understand if mediation or

any other court program is benefitting children. Psychological abuse can be just as devastating as

other forms of abuse (Coker, Smith, Bethea, King, & McKeown, 2000; O’Leary, 1999; Stark,

2007; Theran, Sullivan, Bogat, & Stewart, 2006). Because virtually all cases in the study

involved some form of psychological abuse, mediators should pay particular attention to

assisting the parents to understand and remediate the impact of such abuse on the members of the

family, particularly the children.

Intimate Partner Violence in Mandatory Divorce Mediation

Beck, Walsh, Mechanic, Figueredo & Chen 32 2007-WG-BX-0028

(9) Assess the effectiveness of court-based programs for pre- and post-divorce

“frequent flyers”

A small group of families were found to require a tremendous number of court hearings

post-divorce. As a result, parenting coordinator programs are developing rapidly across the

United States with very little empirical basis of support. Courts need to empirically evaluate the

effectiveness of court-based parenting coordinator and case management processes to determine

whether these programs are having the desired benefits for families.

Intimate Partner Violence in Mandatory Divorce Mediation

Beck, Walsh, Mechanic, Figueredo & Chen 33 2007-WG-BX-0028

Introduction

Statement of the Problem.

Despite three decades of research on numerous aspects of divorce mediation, there is still

no comprehensive understanding of the short- and long-term outcomes for families legally

ordered to mediation to resolve custody and parenting time disputes and who use the free (or low

cost) conciliation court mediation services to do so. This is particularly true for those families

alleging intimate partner abuse (IPA) (Beck & Sales, 2001; Salem, 2009). In 2007, the National

Institute of Justice funded this project to fill this gap in understanding.

Review of Relevant Research and Background of Study

What is mediation in this context?

Mediation is defined as a task-oriented, time-limited, alternative dispute resolution

process (Folberg, 1982). It is important to remember that mediation does not refer to just one

process. The practice can vary along several important dimensions (Beck & Sales, 2001). For

example, models of mediation can vary significantly in terms of the mediators’ role. Mediators

can be either neutral facilitators of a process or can be active participants who, if the parties do

not reach an agreement, can make recommendations to courts regarding specific terms of

agreements. The means by which cases are referred to mediation can vary from a court merely

mentioning that mediation is a possibility to a legal mandate requiring that all cases involving a