auth

October 2023 ii

July 2023

USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS), Veterinary Services (VS)

Strategy & Policy ▪ National Preparedness and Incident Coordination

The continued spread of African swine fever (ASF) in Asia and Europe—and the detection in 2021 on the

Caribbean Island of Hispaniola (Dominican Republic and Haiti)—has placed the Western Hemisphere on

high alert. APHIS has since taken several key steps to fortify the United States in the event of an ASF

outbreak. These actions include the establishment of the ASF Protection Zone, increasing existing

surveillance and mitigations in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands, and initiating several new

proactive mitigation and prevention efforts in those territories. Simultaneously, APHIS accelerated ASF

preparedness efforts in virtually all critical areas: expanding ASF active surveillance in both domestic pigs

and feral swine, validating additional diagnostic sample types, increasing laboratory capacity, procuring

equipment for the National Veterinary Stockpile for swine depopulation and disposal, and further

developing numerous ancillary activities.

The updated version of the USDA APHIS ASF Response Plan: The Red Book (July 2023) reflects

knowledge gained from policy discussions and response guidance development, and lessons learned

from Federal/State/Industry exercises. This plan incorporates and supersedes previous versions of the

ASF Response Plan: The Red Book. Additionally, this version incorporates changes made in related

Foreign Animal Disease Preparedness and Response Plan (FAD PReP) materials.

The following list highlights important revisions made to this version of the ASF Response Plan.

Introduces the concept and benefit of the Protection Zone for Puerto Rico and U.S. Virgin Islands.

Acknowledges potential pathways of the ASF virus into the United States, given the Hispaniola

threat.

Includes a brief evaluation of the risk from Ornithodoros spp. tick as a vector in the United States.

Clarifies information included in the description of the persistence of the ASF virus.

Defines the incubation period for exposed individual pigs. Describes the time for lateral spread

and detection within an exposed herd or group.

Reflects an updated case definition.

Emphasizes the role of contact tracing in an epidemiologic investigation.

Addresses and integrates policy from APHIS’ response to the 2022 United States Animal Health

Association (USAHA) ASF resolutions for:

o Authorization for indemnity and depopulation response time;

o ASF detection in domestic pig as a trigger for a 72-Hour National Movement Standstill;

o Resumption of domestic movement options at ‘Hour 73’;

o Adopting standardized guidelines for harvesting establishments;

o Establish national standardized permitting guidance for Control Areas; and

o Restocking requirements in a Control Area.

Introduces the Meat Harvest, Off-site Rendering, and Spray Dried Blood / Plasma Facility Plans.

Introduces and describes the Domestic Pig and Feral Swine Incident Playbooks.

References the U.S. Swine Health Improvement Plan.

Introduces the Certified Swine Sample Collector Program.

Corrects comments made and any errors identified in the prior version. Updates references

throughout, as necessary.

While this ASF Response Plan provides strategic guidance before an outbreak, there will be additional

policy guidance provided during an outbreak on specific response operation activities, particularly for the

unified Incident Command. Please note certain topics, like the availability of an ASF vaccine for swine or

October 2023 iv

specific response guidance in an active outbreak, have rapidly changing statuses. These types of issues

may be referenced briefly in The ASF Response Plan but treated more fully in associated guidance

documents. If ASF is detected, these additional policy guidance documents and information will be

distributed and available at www.aphis.usda.gov/fadprep.

USDA APHIS acknowledges that preparing for and responding to an ASF outbreak is and will be a

complex effort requiring collaboration and cooperation from all stakeholders. USDA APHIS fully

anticipates updates as new capabilities and processes become available. As such, if you have comments

or suggestions on this document, please send an email to [email protected] with the

subject line: “Comments to Updated ASF Response Plan” for consideration and possible incorporation

into future versions.

The FAD PReP mission is to raise awareness, define expectations, and improve capabilities for FAD

preparedness and response. For more information, please go to www.aphis.usda.gov/fadprep or email

Change Log

USDA APHIS ASF Response Plan: The Red Book (July 2023)

Revision (date) Page / Section Change

Rev.1(October25,2023)

1

Correctedmiscellaneoustypographical

andgrammaticalerrorsthroughout

“ 4‐30/4.11.3 2 RemovedreferencetoTable1‐1,incorrect

reference:

(Table 1-1 provides

information on ASFV susceptibility

according to WOAH).

“ 4‐17/Fig.4‐2 3 Removedcomment,irrelevant:

Stamping-out

is not pictured in these figures.

July 2023 iv

Preface

The Foreign Animal Disease Preparedness and Response Plan (FAD PReP)—

African Swine Fever Response Plan: The Red Book (July 2023) provides strategic

guidance for responding to an animal health emergency caused by African swine

fever (ASF) in the United States. Information in this plan may require further

discussion and development with stakeholders.

This ASF Response Plan is under ongoing review. This document is a major

revision of the previous version published in April 2020. The primary additions

and revisions are listed in the above introductory message. Please send questions

or comments to:

National Preparedness and Incident Coordination Center

Veterinary Services

Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service

U.S. Department of Agriculture

E-mail: FAD.PReP[email protected]

While best efforts have been used in developing and preparing the ASF Response

Plan, the U.S. Government, U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the

Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service and other parties, such as employees

and contractors contributing to this document, neither warrant nor assume any

legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of

any information or procedure disclosed. The primary purpose of this ASF

Response Plan is to provide strategic guidance to government officials responding

to an ASF outbreak. It is only posted for public access as a reference.

The ASF Response Plan may refer to links of various other Federal and State

agencies and private organizations. These links are maintained solely for the

user’s information and convenience. If you link to such a site, please be aware

that you are then subject to the policies of that site. In addition, please note that

USDA does not control and cannot guarantee the relevance, timeliness, or

accuracy of these outside materials. Further, the inclusion of links or pointers to

items in hypertext is not intended to reflect their importance, nor is it intended to

constitute approval or endorsement of any views expressed, or products or

services offered, on these outside websites, or the organizations sponsoring the

websites.

Trade names are used solely for the purpose of providing specific information.

Mention of a trade name does not constitute a guarantee or warranty of the

product by USDA or an endorsement over other products not mentioned.

In accordance with Federal civil rights law and USDA civil rights regulations and

Preface

July 2023 v

policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions

participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from

discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity

(including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status,

family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political

beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or

activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs).

Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident.

Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for

program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign

Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA's TARGET

Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal

Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. Additionally, program information may be

made available in languages other than English.

To file a program discrimination complaint, complete the USDA Program

Discrimination Complaint Form, AD-3027, found online at How to File a

Program Discrimination Complaint (www.usda.gov/oascr/how-to-file-a-program-

discrimination-complaint) and at any USDA office or write a letter addressed to

USDA and provide in the letter all of the information requested in the form. To

request a copy of the complaint form, call (866) 632-9992. Submit your

completed form or letter to USDA by: (1) mail: U.S. Department of Agriculture,

Office of the Assistant Secretary for Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue,

SW, Washington, D.C. 20250-9410; (2) fax: (202) 690-7442; or (3) email:

[email protected]. USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer.

July 2023 vi

Contents

Chapter 1 Introduction and ASF Information ............................................ 1-1

1.1 INTRODUCTION TO RESPONSE PLAN ..................................................................... 1-1

1.2 SCOPE OF RESPONSE PLAN ................................................................................. 1-1

1.3 HISTORICAL PRESENCE AND CURRENT ASF SITUATION .......................................... 1-2

1.3.1 Threat of ASF in the United States ....................................................... 1-3

1.3.2 Preparedness Planning ........................................................................ 1-3

1.3.2.1 THE PROTECTION ZONE .................................................................. 1-4

1.3.2.2 SWINE INDUSTRY BACKGROUND ....................................................... 1-4

1.3.2.3 KEY AREAS OF FOCUS FOR PREPAREDNESS ..................................... 1-5

1.3.2.4 NEW PREPAREDNESS INITIATIVES .................................................... 1-6

1.4 NATURE OF THE DISEASE/VIRUS ........................................................................... 1-7

1.4.1 Overview ............................................................................................... 1-7

1.4.2 Introduction & Transmission ................................................................. 1-8

1.4.3 Incubation Period .................................................................................. 1-9

1.4.4 Clinical Signs ...................................................................................... 1-10

1.4.5 Morbidity and Mortality........................................................................ 1-11

1.4.6 Differential Diagnosis .......................................................................... 1-11

1.4.7 Persistence of ASFV........................................................................... 1-11

Chapter 2 Framework for ASF Preparedness and Response .................. 2-1

2.1 FOUNDATION OF PREPAREDNESS AND RESPONSE .................................................. 2-1

2.2 USDA AUTHORITIES ............................................................................................ 2-1

2.2.1 The Animal Health Protection Act, 7 U.S. Code 8301 et seq. ............... 2-1

2.2.2 The Swine Health Protection Act, 7 U.S. Code 3801 et seq. ................ 2-2

2.3 USDA APHIS VS GUIDANCE ............................................................................... 2-3

2.3.1 Procedures and Policy for an ASF Investigation, VS Guidance

12001.4 ................................................................................................ 2-3

2.3.2 Animal Health Policy in Relation to Feral Swine ................................... 2-3

2.4 USDA ROLES AND RESPONSIBILITIES OVERVIEW ................................................... 2-4

2.5 USDA APHIS INCIDENT MANAGEMENT ................................................................. 2-4

Contents

July 2023 vii

2.5.1 Incident Management Structure ............................................................ 2-5

2.5.2 Field Organization ................................................................................ 2-5

Chapter 3 ASF Outbreak Response Goals and Strategy ......................... 3-1

3.1 RESPONSE GOALS ............................................................................................... 3-1

3.2 EPIDEMIOLOGICAL PRINCIPLES ............................................................................. 3-1

3.3 CONTROL AND ERADICATION STRATEGIES ............................................................. 3-2

3.3.1 Defining Stamping-Out as a Response Strategy .................................. 3-2

3.3.2 Zones and Areas in Relation to Stamping-Out ..................................... 3-3

3.3.3 Zones and Areas in Relation to Contact Tracing .................................. 3-4

3.3.4 Control and Eradication of ASF in Domestic Pigs ................................. 3-5

3.3.5 Control and Eradication of ASF in Feral Swine ..................................... 3-6

3.4 INITIAL RESPONSE ACTIONS ................................................................................. 3-7

3.4.1 Authorization for Response and Associated Activities .......................... 3-7

3.4.2 Coordinated Public Awareness Campaign ........................................... 3-9

3.4.3 Regulatory Movement Controls .......................................................... 3-10

3.4.4 Initial Critical Activities of an ASF Response ...................................... 3-12

3.5 MOVEMENT CONTROL POST STANDSTILL ............................................................ 3-14

3.6 HOUR 73: RESPONSE OPTIONS FOLLOWING A 72-HOUR NATIONAL MOVEMENT

STANDSTILL ................................................................................................... 3-14

Chapter 4 Specific ASF Response Critical Activities and Tools ............... 4-1

4.1 ETIOLOGY AND ECOLOGY ..................................................................................... 4-1

4.2 LABORATORY DEFINITIONS AND CASE REPORTING ................................................. 4-2

4.2.1 Laboratory Definitions ........................................................................... 4-2

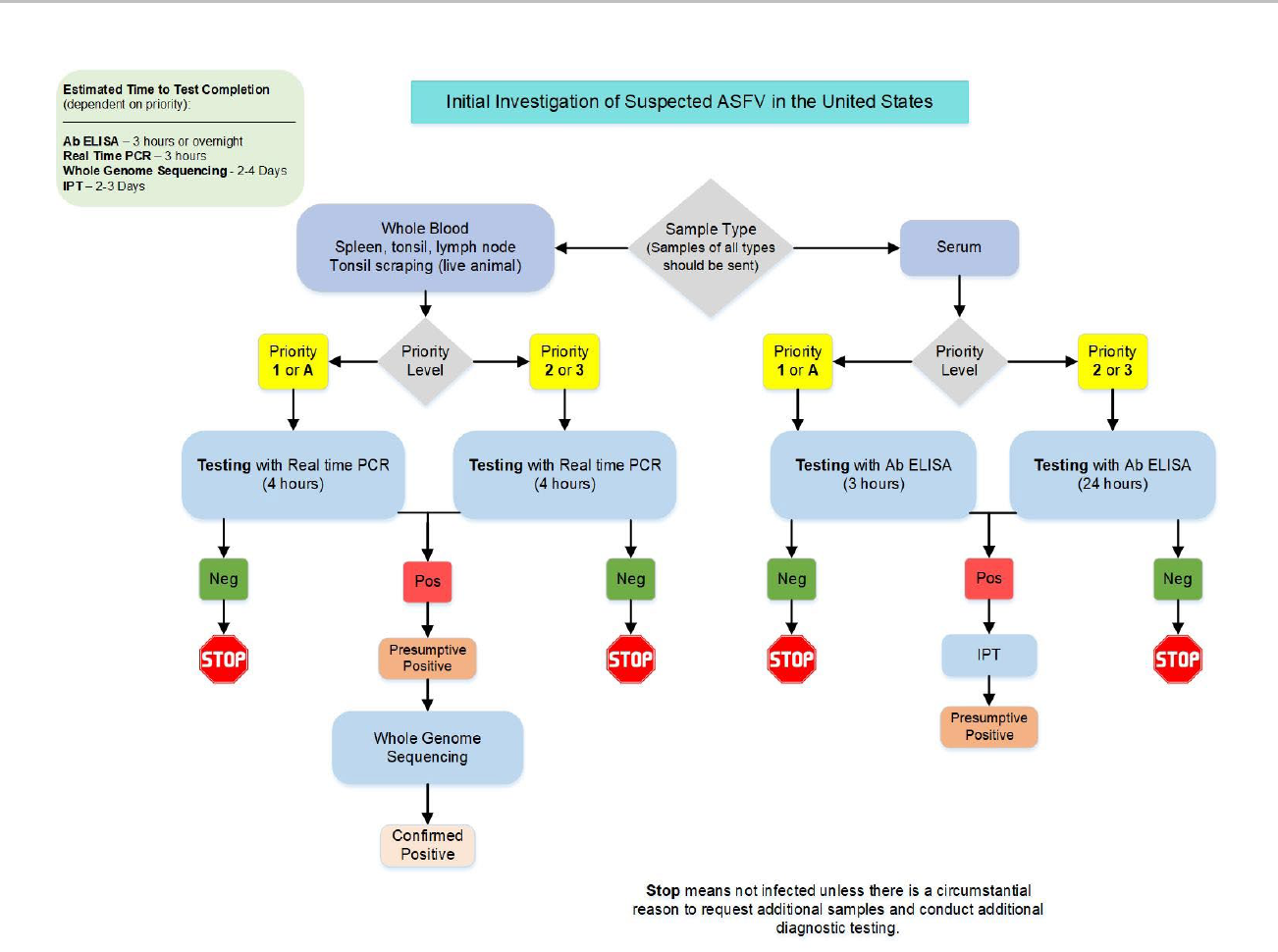

4.3 DIAGNOSTICS ...................................................................................................... 4-3

4.3.1 Sample Collection and Diagnostic Testing ........................................... 4-4

4.3.2 Surge Capacity ..................................................................................... 4-8

4.4 SURVEILLANCE DESIGN ........................................................................................ 4-8

4.4.1 Surveillance Goals and Objectives ....................................................... 4-8

4.4.2 Surveillance Activities Overview ........................................................... 4-9

4.4.3 Passive Surveillance .......................................................................... 4-10

4.4.4 Active Surveillance for Domestic Pigs ................................................ 4-10

4.4.5 Active Surveillance for Feral Swine .................................................... 4-11

Contents

July 2023 viii

4.5 EPIDEMIOLOGY .................................................................................................. 4-11

4.5.1 Zones, Areas, and Premises Designations ......................................... 4-12

4.5.2 Visualizing Zones and Areas for Domestic Pigs & Feral Swine .......... 4-16

4.5.3 Epidemiological Investigation and Contact Tracing ............................ 4-18

4.6 DOMESTIC RESPONSE: QUARANTINE AND MOVEMENT CONTROL ........................... 4-19

4.6.1 Control Area Movement ...................................................................... 4-20

4.7 CONTINUITY OF BUSINESS .................................................................................. 4-22

4.7.1 COB Permits for Live Animal and Semen Movements ....................... 4-22

4.7.1.1 ASF COB PERMIT AND PMIP REQUIREMENTS FOR CONTROL

AREAS ............................................................................................ 4-23

4.8 INFORMATION, REPORTING AND TASK MANAGEMENT ............................................ 4-25

4.8.1 Emergency Management Response System 2.0 (EMRS) .................. 4-25

4.8.2 Reporting ............................................................................................ 4-26

4.8.3 Information Management Systems and Tools .................................... 4-26

4.9 HEALTH & SAFETY AND PERSONAL PROTECTIVE EQUIPMENT ................................ 4-27

4.9.1 Mental Health Concerns ..................................................................... 4-27

4.10 BIOSECURITY .................................................................................................. 4-28

4.11 3D ACTIVITIES ................................................................................................. 4-28

4.11.1 Mass Depopulation and Euthanasia ................................................. 4-28

4.11.2 Disposal ............................................................................................ 4-29

4.11.3 Cleaning and Disinfection/Virus Elimination ..................................... 4-30

4.11.4 National Veterinary Stockpile Operations ......................................... 4-30

4.12 APHIS WILDLIFE SERVICES ............................................................................. 4-31

4.12.1 Feral Swine Management ................................................................. 4-31

4.12.2 Vectors ............................................................................................. 4-33

4.13 INDEMNITY AND COMPENSATION ....................................................................... 4-33

4.13.1 Authority ........................................................................................... 4-33

4.13.2 Procedures ....................................................................................... 4-34

4.14 ANIMAL WELFARE ............................................................................................ 4-34

4.15 VACCINATION .................................................................................................. 4-34

Chapter 5 Recovery ................................................................................. 5-1

5.1 CRITERIA FOR PROOF OF FREEDOM ...................................................................... 5-1

5.2 WOAH TERRESTRIAL ANIMAL HEALTH CODE ........................................................ 5-1

Contents

July 2023 ix

5.2.1 Article 15.1.4 Country or Zone Free from ASF ..................................... 5-1

5.2.2 Article 15.1.7 Recovery of Free Status ................................................. 5-2

5.3 RESTOCKING ....................................................................................................... 5-3

Figures

Figure 3-1. Example of Zones and Areas in Relation to Stamping-Out................... 3-4

Figure 3-2. Example of Contact Tracing in an ASF Outbreak ................................. 3-4

Figure 3-3. Initial Critical Activities of an ASF Response ...................................... 3-13

Figure 4-1. Diagnostic Test Flow for Initial Investigation of ASF in the United

States ................................................................................................................ 4-7

Figure 4-2. Examples of Zones, Areas, and Premises for Domestic Pigs and

Feral Swine in an ASF Outbreak Response .................................................... 4-17

Tables

Table 1-1. Clinical Signs Caused by the Different Forms of ASF .......................... 1-10

Table 1-2. Resistance of ASFV to Physical and Chemical Action ......................... 1-12

Table 4-1. Sample Collection for Diagnostic Testing .............................................. 4-5

Table 4-2. Diagnostic Tests Performed for ASFV at NVSL-FADDL ........................ 4-6

Table 4-3. Summary of ASF Premises Designations for Domestic Pig

Production Premises ....................................................................................... 4-12

Table 4-4. Summary of ASF Zone and Area Designations ................................... 4-13

Table 4-5. Minimum Size of Zones and Areas ...................................................... 4-13

Table 4-6. Factors to Consider in Determining Control Area Size for ASF ........... 4-14

Table 4-7. Movement Controls: Permit Types during an FAD Incident ................. 4-21

Appendicies

Appendix A Glossary

Appendix B Example Overview Emergency Management Response System

2.0 Workflow

Appendix C Abbreviations

Appendix D Selected References and Resources

July 2023 1-1

Chapter 1

Introduction and ASF Information

1.1 INTRODUCTION TO RESPONSE PLAN

Due to the potential threat of African swine fever (ASF) in the United States from

ongoing transmission throughout East Asia, parts of Europe and the Caribbean

Island of Hispaniola (Dominican Republic and Haiti), this ASF Response Plan:

The Red Book is updated as of July 2023. This version supersedes the previous

version of the African Swine Fever Response Plan. The objectives of this plan are

to identify the (1) policies and strategies needed to respond to an ASF outbreak in

swine and (2) capabilities and critical activities that are involved in responding to

that outbreak and (3) the timeframes for these activities. In an outbreak situation,

these critical activities are under the authority of a unified State and Federal

Incident Command per the National Incident Management System (NIMS).

This ASF Response Plan provides current information on ASF and its relevance to

the United States. It does not replace existing regional, State, Tribal, local, or

industry preparedness and response plans relating to ASF. Regional, State, Tribal,

local and industry plans should be aimed at more specific issues in an ASF

response. In particular, States should develop response plans focused on the

specific characteristics of the State and the State’s swine industry. Industry should

develop response plans focused on the specific characteristics of their commercial

operations and business practices.

1.2 SCOPE OF RESPONSE PLAN

This ASF Response Plan provides strategic guidance for the U.S. Department of

Agriculture (USDA) and the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service

(APHIS) and responders at all levels in the event of an ASF outbreak occurring in

domestic or feral swine.

This document does not cover, in detail, incident coordination or general foreign

animal disease (FAD) response. For more information on these aspects, please

refer to the APHIS Foreign Animal Disease Framework: Roles and Coordination

(FAD PReP Manual 1-0) and the APHIS Foreign Animal Disease Framework:

Response Strategies (FAD PReP Manual 2-0). These documents cover general

roles and responsibilities as well as general FAD response strategies, respectively.

These documents and other Foreign Animal Disease Preparedness and Response

Plan (FAD PReP) materials are available here:

https://www.aphis.usda.gov/fadprep.

Introduction and ASF Information

July 2023 1-2

Additionally, this document does not provide in detail every response policy or

response procedure for an outbreak. (e.g., specific virus elimination guidance,

stamping-out policies, indemnity processes, etc.), or address international

movement (export) considerations/ requirements. Past experience demonstrates

this type of information is more effectively communicated as distinct, short,

concise documents or information published on the FAD PReP website that can

be distributed and updated rapidly. There will be additional policy guidance

provided during an outbreak on specific response operation activities. In the event

of an ASF outbreak in the United States, these policy guidance documents and

updates will be posted on the ASF FAD PReP website.

1.3 HISTORICAL PRESENCE AND CURRENT ASF

SITUATION

ASF—first described in Kenya in the 1920s—is a contagious hemorrhagic disease

of wild/feral and domestic pigs. It is often characterized by high morbidity and

mortality rates. There is no effective treatment for ASF-infected swine, and

vaccine candidates are still being researched and evaluated. ASF is a notifiable

disease to the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH), which began

collecting data on ASF in 2005. The disease does not pose a risk to human health

or food safety.

ASF is currently widespread and endemic in sub-Saharan Africa, parts of West

Africa, and the island of Sardinia. Beginning in 2007, ASF was confirmed in

several East European countries, then it started appearing in European Union

countries in 2014. The year 2018 brought the emergence of the virus in China.

Not only does ASF continue to spread in the Europe, Asia, and the Pacific

regions—both in domestic pigs and wild boars—the virus is also difficult to

eradicate. Some successes have been reported. The Czech Republic eradicated

ASF after a 2018 outbreak, only to see its return a few years later. Belgium

eradicated ASF in 2020; Spain and Portugal in the mid-1990s; Hispaniola

following outbreaks from 1977–1980.

In 2021, ASF was again detected in the Western Hemisphere on the Caribbean

Island of Hispaniola (Dominican Republic and Haiti). As a consequence of this

detection, the USDA established a Protection Zone (PZ) for the United States

Territory of Puerto Rico (PR) and U.S. Virgin Islands (USVI). The PZ is

consistent with the WOAH Terrestrial Code Chapter 4.4, Zoning and

Compartmentalization.

ASF has never been reported in the United States, Canada, Australia, or New

Zealand.

Int

roduction and ASF Information

July 2023 1-3

1.3.1 Threat of ASF in the United States

ASF is a critical threat to the United States due to the recent global spread,

millions of susceptible swine in the United States, including feral swine, and the

potential for severe economic impacts – estimated at several billion dollars.

Although significant and promising advances were recently made in developing

an ASF vaccine, there is still no commercially available, effective vaccine

approved for emergency use in the United States. This makes prevention of

disease entry critically important, and thorough preparation for an emergency

response is vital.

In March 2019, USDA APHIS conducted the following ASF threat assessments:

all of which are available online under Animal Disease Information for Swine:

o A qualitative assessment of the likelihood of ASF virus entry to the United

States.

1

o A non-animal origin feed ingredient risk evaluation framework.

2

o A literature review of non-animal origin feed ingredients and the

transmission of viral pathogens of swine.

3

Among the findings of these evaluations is international travel and trade pose a

substantial risk for viral incursion into the country. Illegal entry of swine products

and byproducts presents the largest potential pathway for entry of ASF virus

(ASFV) into the United States.

1.3.2 Preparedness Planning

With the continued expansion of ASF throughout Asia, Europe, and most recently

Hispaniola in the Western Hemisphere APHIS preparedness efforts remain a

priority. USDA continues to work closely with other Federal and State agencies,

the swine industry, producers, and international partners to prepare for and

prevent an occurrence in North America. Since 2018, USDA has participated in a

series of tri-lateral (Canada, Mexico, and the United States) ASF Forums and

initiated an ASF-specific exercise program to coordinate efforts. Preparedness and

response exercises help ensure our Nation’s readiness and provides an ideal, no-

fault learning environment to discuss, practice, and implement plans, procedures,

1

APHIS CEAH. (2019, March). Qualitative assessment of the likelihood of African Swine

Fever Virus entry to the United States: entry assessment. Risk Assessment Team. Retrieved from

https://www.aphis.usda.gov/animal_health/downloads/animal_diseases/swine/asf-entry.pdf

.

2

APHIS CEAH. (2019, March). Non-animal origin feed ingredient risk evaluation

framework: scoping. Risk Assessment Team. Retrieved from

https://www.aphis.usda.gov/animal_health/downloads/animal_diseases/swine/nofi-scope.pdf

.

3

APHIS CEAH. (2019, March). Literature Review: Non-animal Origin Feed Ingredients and

the Transmission of Viral Pathogens of Swine. Risk Assessment Team. Retrieved from

https://www.aphis.usda.gov/animal_health/downloads/animal_diseases/swine/non-anim

al-origin-

feed-ingredients-transmission-of-viral-pathogens.pdf.

Int

roduction and ASF Information

July 2023 1-4

and processes in advance of an actual event. The 2021 detection of the ASFV in

the Western Hemisphere created yet another sense of urgency.

1.3.2.1 THE PROTECTION ZONE

As a consequence of the September 2021 detection of ASF in Hispaniola, the

USDA established a PZ for the U.S. territories of PR and USVI in the Caribbean.

The PZ is designed to minimize risk and allow the continental United States

(CONUS) to maintain its free status if an ASF outbreak were to occur in the PZ.

International standards require, and the U.S. implemented, biosecurity and

sanitary measures in the PZ. APHIS VS also intensified movement control,

animal identification, and animal traceability to ensure that animals in the PZ are

clearly distinguishable from other populations. Additionally, APHIS VS

implemented increased surveillance in the PZ and the rest of the country,

including surveillance of wildlife.

One aspect of the Federal Order (FO) establishing the PZ was the suspension of

interstate movement of all live swine, swine germplasm, and the placement of

restrictions and transit permit requirements on swine products, and swine

byproducts from PR and USVI. To support this, APHIS Plant Protection and

Quarantine (PPQ) leveraged the predeparture program to screen passengers and

small parcel cargo moving from PR and USVI to CONUS for prohibited swine

products. PPQ has also engaged express couriers and the United States Postal

Service to establish a joint program to inspect mail for prohibited animal and

plant products destined for CONUS.

The newly established PZ can be added to the longstanding, interlocking

safeguards USDA has instituted through its regulatory authorities to prevent ASF

from entering the country.

1.3.2.2 SWINE INDUSTRY BACKGROUND

Although the U.S. may glean lessons from Europe and Asia with regard to ASF

preparedness, our domestic pig sector and feral swine populations are distinct

from those regions and require unique planning and approaches.

According to USDA’s National Agriculture Statistical Service, most (70%) of the

swine operations in the U.S. are small hobby operations, with 25 or fewer swine

on the premises. However, greater than 90% of the swine inventory were located

on hog operations with more than 2,000 head of swine. The States of Iowa, North

Carolina, Minnesota, Illinois, Indiana, Nebraska, Missouri, Ohio, Oklahoma, and

Kansas accounted for nearly 87 percent of all pigs in the U.S. inventory.

An estimated one million swine are being transported in trucks daily to various

locations, including slaughter and further production and approximately 500,000

hogs are slaughtered each day.

Int

roduction and ASF Information

July 2023 1-5

1.3.2.3 KEY AREAS OF FOCUS FOR PREPAREDNESS

APHIS continues to work in earnest with states and the swine industry to develop

and refine plans in case of a U.S. ASF outbreak. Through this collaborative

planning process, we are able to better understand the factors specific to the U.S.

swine industry that may pose response challenges.

1.3.2.3.1 Site Biosecurity

Biosecurity is key to preventing disease introduction and spread. Biosecurity

includes the use of certain management practices to prevent the introduction of

new disease and the spread of existing disease on swine operations. Examples of

these practices include limiting opportunities for feral swine and domestic pigs to

mingle; cleaning and disinfecting all equipment and vehicles entering or leaving a

production site; and controlling human and vehicle entry between and within

operations. Producers are responsible for developing and adhering to site-specific

biosecurity plans to protect their own investments. Zoos and wildlife parks with

exotic swine species are responsible for developing and adhering to their

biosecurity plans.

Guidance and best practices are available through industry-led efforts such as the

Secure Pork Supply (SPS) Plan and U.S. Swine Health Improvement Plan (US

SHIP).

1.3.2.3.2 Truck Sanitation

Various diseases, including porcine epidemic diarrhea virus, certain strains of

Senecavirus A, and other endemic diseases have been able to spread among the

U.S. swine herd within months of introduction. Among the factors scientific

studies attribute rapid disease spread to is the practice of transporting hogs in

vehicles that are not cleaned and disinfected between loads. Locations of concern

include all swine points of concentration, including slaughter plants, feed mills,

and other collection points that contaminated vehicles may frequent and track

virus.

1.3.2.3.3 Swine Traceability

In the event of an ASF disease outbreak on the U.S. mainland, trading partners

will need to accept U.S. measures for traceability of swine commodities (live pigs

and pork products) before engagement in regionalization or zoning agreements

and resuming exports.

Early in 2022, the U.S. swine industry identified traceability as a priority for ASF

preparedness. USDA APHIS is collaborating with stakeholders to develop a new

framework for swine traceability. The agency is also open to non-regulatory

options for activities that may be implemented sooner than the Federal

rulemaking process allows.

Int

roduction and ASF Information

July 2023 1-6

1.3.2.4 NEW PREPAREDNESS INITIATIVES

1.3.2.4.1 U.S. Swine Health Improvement Program

An APHIS-funded pilot project promoting certification of healthy swine herds

called the US SHIP is underway. The US SHIP program is intended to target ASF

and classical swine fever through the creation of standards focusing on

biosecurity, traceability, and surveillance principles. Currently, technical advisory

committees comprised of U.S. pork industry subject matter experts are further

developing technical standards necessary for “safeguarding, certifying, and

bettering the health of U.S. swine.” Pork producers and packing facilities in

participating States that meet specified program requirements can enroll in the

pilot program on a voluntary basis. As of early 2023, 32 States are active in the

US SHIP program, including the top-producing swine States; and more than 50%

of the United States’ swine inventory is enrolled in the program with over 9000

participants. Industry has maintained a strong interest in seeing the program

established as an official USDA program through the rulemaking process. As the

pilot progresses, APHIS continues to assess the potential for making that

transition.

For additional details and status of the US SHIP program, see

https://www.usswinehealthimprovementplan.com.

1.3.2.4.2 National Standardized Permitting Guidance for Control Areas

The swine industry identified the need for the development of consistent national

criteria for intrastate and interstate swine movements from Control Areas in

advance of an ASF outbreak. USDA APHIS collaborated with the USAHA Swine

Committee to establish the biosecurity, surveillance and testing requirements for

permitted movements. The resulting permitting guidance for various types of

swine movements within, into, and out of a Control Area are available on the ASF

FAD PReP website.

1.3.2.4.3 ASF Meat Harvest, Rendering, and Spray Dried Blood / Plasma Facility

Response Plans

The ASF Meat Harvest Facility Response Plans were created to address response

needs unique to harvest establishments and related industries during an ASF

outbreak. These plans were developed in coordination with APHIS and the North

American Meat Institute (NAMI)-led Slaughter Plant Working Group (SPWG)

with participation from various Federal, State, and industry partners.

The culmination of the SPWG’s efforts were the development of three ASF

response plans to target specific scenarios for: 1) Meat Harvest Facilities in the

Free Area with a Contact Premises status, 2) Meat Harvest Facilities located

within a Control Area that do not have an Infected Premises status, and finally 3)

Meat Harvest Facilities with an Infected/Positive premises status when ASF

Int

roduction and ASF Information

July 2023 1-7

presumptive or confirmed positive swine have been detected at the facility. Each

of these templates are intended to serve as a response guide for harvest facilities

during an ASF response.

Further, in collaboration with the North American Renderers’ Association and

North American Spray Dried Blood & Plasma Producers, the SPWG created two

additional ASF Response plans specific to Off-Site Rendering and Spray Dried

Blood / Plasma facilities.

These plans are a critical industry resource for implementing biosecurity practices

aimed at preventing or recovering from an onsite ASF infection. They provide

virus elimination standards following an ASF detection onsite and outline

biosecurity practices to ensure continuity of business for these facility types. To

find these templates, please go to the ASF FAD PReP website.

1.4 NATURE OF THE DISEASE/VIRUS

This is a brief introduction to ASFV, which is a complex virus with variable

clinical presentations. Further detail can be found in the FAD PReP ASF SOP:

Overview of Etiology and Ecology.

1.4.1 Overview

ASFV belongs to the Asfivirus genus of the Asfarviridae family and is an

enveloped virus with a double-stranded DNA genome. ASFV is unique, as it is

the only known arthropod-borne DNA virus. Currently, there is no vaccine

approved for emergency use in the United States.

There are 24 different genotypes and 8 serogroups of ASFV. Infection with ASFV

presents in four different clinical forms (peracute, acute, subacute, and chronic),

which are based on strain virulence, immune status, clinical signs, and gross

lesions.

Susceptible species include all members of the pig family (Suidae): domesticated

swine, feral swine, European wild boar, warthogs, bush pigs, and giant forest

hogs. While susceptible, warthogs and bush pigs are resistant to signs of clinical

disease. Some members of the Suidae family native to the Americas, such as

peccaries (Tayassu spp.), are believed to be resistant to infection.

4

4

Based on historical information, see Dardiri, A.H., Yedloutschnig, R.J., & Taylor, W.D.

(1969). Clinical and serologic response of American white-collared peccaries to African swine

fever, foot-and-mouth disease, vesicular stomatitis, vesicular exanthema of swine, hog cholera,

and rinderpest viruses. Proc Annual Meeting U.S. Animal Health Assoc. 73, 437–52.

Int

roduction and ASF Information

July 2023 1-8

1.4.2 Introduction & Transmission

There are three primary modes of transmission for ASFV: direct contact, indirect

contact (fomites), and vector-borne. Direct pig-to-pig transmission occurs when

infected pigs come into contact with susceptible pigs through contact with

infectious blood, swine germplasm, excretions and secretions (e.g., saliva,

respiratory secretions, urine and feces), or pig carcasses. There is lack of evidence

that an infected pig can become a carrier and shed ASFV without showing clinical

signs.

5,6

Indirect transmission can occur through contaminated pig products or

fomites. ASFV can survive for months in pork meat, fat, and skin, and serve as a

route of transmission, e.g., through the practice of “garbage-feeding” where swine

become infected when fed contaminated food waste that has not been cooked

appropriately to inactivate the virus. Potential transmission has experimentally

been demonstrated through contaminated feed. It is also possible that ASFV can

be transmitted mechanically. A 2018 study found that, while ingested ASFV-

spiked stable flies could infect some pigs, it is unlikely that ingestion of blood-fed

flies is a common route for transmission of ASFV between wild boars or between

pigs within a stable.

7

Soft ticks (Ornithodoros spp.) are competent vectors for ASFV transmission,

passing the virus to swine hosts when taking their blood meal. In sub-Saharan

Africa, ASF is maintained through the sylvatic cycle—recurring transfer between

bushpigs, warthogs, and giant forest hogs of Africa and Ornithodoros species

ticks that live in their wallows and burrows. These pigs are inapparently infected

and act as reservoir hosts for ASFV.

8

Infected ticks are also able to transmit

ASFV to other ticks (sexual), to their offspring (transovarial), and/or from one life

cycle to another (transstadial). However, even where the sylvatic cycle exists in

East and Central African countries, the majority of ASF outbreaks are not

associated with ticks or wild suids.

9

ASFV has been shown to persist in some Ornithodoros species for more than 5

years.

10

While some Ornithodoros species are present in the United States, it is

5

Guinat, C., Gogin, A., Blome, S., Keil, G., Pollin, R., Pfeiffer, D.U., and Dixon, L. (2016).

Transmission routes of African swine fever virus to domestic pigs: current knowledge and future

research directions. Veterinary Record.178, 262-267. Doi: 10.1136/vr.103593.

6

Karl Ståhl, K., Sternberg-Lewerin, S., Blome, S., Viltrop, A., Penrith, M., Chenais, W.

(2019). Lack of evidence for long term carriers of African swine fever virus - a systematic review,

Virus Research, Vol 272.

7

Olesen, A.S., Lohse, L., Hansen, M.F., Boklund, A., Halasa, T., Belsham, G.J., … Bodker,

R. (2018). Infection of pigs with African swine fever virus via ingestion of stable flies (Stomoxys

calcitrans). Transboundary and Emerging Diseases. 65, 1152–1157. Doi: 10.1111/tbed.12918.

8

WOAH. (2021). African Swine Fever. Technical Disease Card.

https://www.woah.org/app/uploads/2021/03/oie-african-swine-fever-technical-disease-card.pdf

9

Sánchez-Vizcaíno JM, Mur L, Bastos AD, Penrith ML. New insights into the role of ticks in

African swine fever epidemiology. Rev Sci Tech. 2015 Aug;34(2):503-11.

10

Sanchez-Vizcaino, J.M., Mur, L., Martinez-Lopez, B. (2012). African Swine Fever: An

Epidemiological Update. Transboundary and Emerging Diseases. 59(Suppl. 1), 27–35.

Intr

oduction and ASF Information

July 2023 1-9

unlikely they would play a significant role in transmission given the absence of a

primary wild suid reservoir host population to maintain a sylvatic cycle. Wild

boar populations have been implicated in sustained transmission of ASFV,

particularly in parts of the European Union.

11

There has only been one outbreak in

Europe where the O. erraticus tick, an Ornithodoros species not found in the

United States, played a role in viral transmission among outdoor swine farms on

the Iberian Peninsula.

12

However, Ornithodoros species of ticks do not appear to

be critical to the maintenance of ASFV in European wild boar populations.

Importantly, ticks did not play a role in ASFV transmission despite the presence

of O. puertorincensis in Haiti and the Dominican Republic during an ASF

outbreak that lasted from 1978 to 1983.

13

Ornithodoros ticks are discussed in

Section 4.12.2.

In other areas of the world, ASFV has been introduced and transmitted by illegal

movement of infected swine and contaminated products (and their contact with

naïve swine).

1.4.3 Incubation Period

The incubation period varies by exposure dose, route of transmission, and viral

strain ranging from 3–21 days. The WOAH Terrestrial Animal Health Code states

that the incubation period in Sus scrofa (domestic and wild swine) is 15 days.

14

A

shorter incubation period (3-4 days) is typically observed with the acute form of

disease.

When considering the incubation period for ASF, it is important to consider both

the incubation period for ASF virus in an individual pig exposed (generally 2 – 7

days

15,16

), as well as the time to detect ASF in a group or herd of pigs with respect

to clinical signs. Since ASF infection in pigs can resemble other common pig

diseases and transmission is slow within a herd, early detection through clinical

11

European Food Safety Authority. (2018). Epidemiological analyses of African swine fever

in the European Union. European Food Safety Authority Journal. 16(11), 5494.

12

Sanchez-Vizcaino, J.M., Mur, L., Martinez-Lopez, B. (2012). African Swine Fever: An

Epidemiological Update. Transboundary and Emerging Diseases. 59(Suppl. 1), 27–35.

13

Brown, V. and Bevins, S. (2018). A review of African swine fever and the potential for

introduction into the United States and the possibility of subsequent establishment in feral swine

and native ticks. Front. Vet. Sci., 06. Vol 5.

14

WOAH. (2022). Article 15.1.1. Terrestrial Animal Health Code.

https://www.woah.org/en/what-we-do/s

tandards/codes-and-manuals/terrestrial-code-online

access/?id=169&L=1&htmfile=chapitre_asf.htm.

15

Malladi S, Ssematimba A, Bonney PJ, St Charles KM, Boyer T, Goldsmith T, Walz E,

Cardona CJ, Culhane MR. Predicting the time to detect moderately virulent African swine fever

virus in finisher swine herds using a stochastic disease transmission model. BMC Vet Res. 2022

Mar 2;18(1):84. doi: 10.1186/s12917-022-03188-6.

16

Guinat, C., Porphyre, T., Gogin, A., Dixon, L., Pfeiffer, D. U., & Gubbins, S. (2018).

Inferring within-herd transmission parameters for African swine fever virus using mortality data

from outbreaks in the Russian Federation. Transboundary and emerging diseases, 65(2), e264–

e271. https://doi.org/10.1111/tbed.12748.

Int

roduction and ASF Information

July 2023 1-10

signs or passive surveillance can take an extended period of time (>20 days

17

) for

groups or herds of pigs.

1.4.4 Clinical Signs

Clinical signs vary by virus strain and disease form caused by the virus (peracute,

acute, subacute, and chronic). In swine affected with the peracute form of ASF,

death is often the first indication of disease. Swine affected with the acute form

may develop fever (105–107.6°F/40.5–42°C), anorexia, listlessness, cyanosis,

incoordination, increased pulse and respiratory rate, leukopenia, and

thrombocytopenia (at 48–72 hours), vomiting, diarrhea, and abortion in pregnant

sows.

Swine affected with subacute forms of ASF present with less intense, but similar

clinical signs including slight fever, reduced appetite, and depression. Abortion in

pregnant sows is also possible. Swine infected with the chronic form of the virus

typically exhibit appetite loss, transient low fever, respiratory signs, necrosis of

the skin, chronic skin ulcers, and swelling of the joints. They also can experience

recurring episodes of disease, which could eventually lead to death.

18

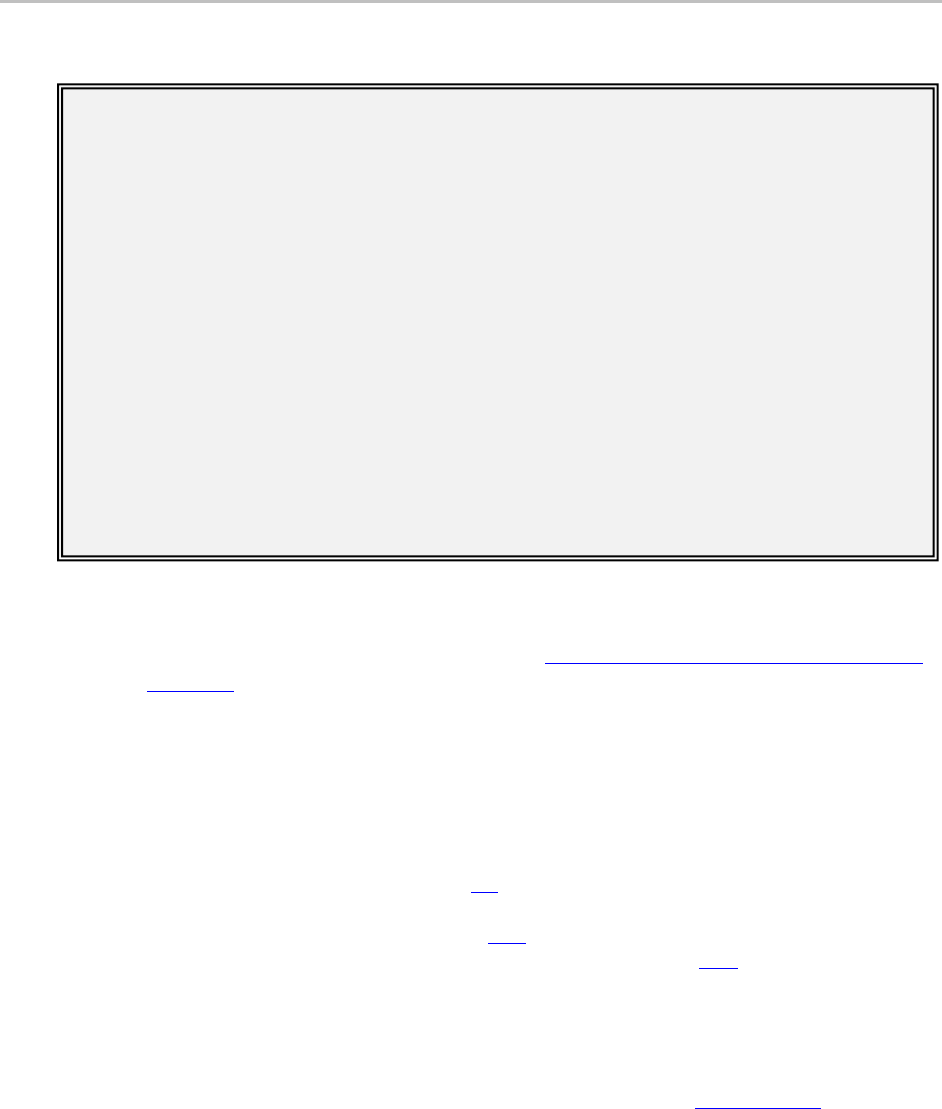

Table 1-1

summarizes these signs.

Table 1-1. Clinical Signs Caused by the Different Forms of ASF

17

Ssematimba A, Malladi S, Bonney PJ, St Charles KM, Boyer TC, Goldsmith T, Cardona

CJ, Corzo CA, Culhane MR. African swine fever detection and transmission estimates using

homogeneous versus heterogeneous model formulation in stochastic simulations within pig

premises. Open Vet J. 2022 Nov-Dec;12(6):787-796. doi: 10.5455/OVJ.2022.v12.i6.2.

18

Petrov, A. et al. (2018). No evidence for long-term carrier status of pigs after African swine

fever virus infection. Transboundary and Emerging Diseases. 65(5), 1318–1328.

Peracute

Acute

Subacute

Chronic

Virulence of

strain

High

High

Moderate to low

Low

Immune

status

Death before

seroconversion

Many die before seroconversion

Seropositive

Seropositive

Clinical signs

Often found

moribund or

dead

Febrile (40.5°C–41.5°C), leukopenia,

anorexia, blood in feces, reluctant to

move, abortion in sows, erythemic

skin progressing to cyanosis near

death

Variable but typically similar

to, though less severe than,

acute ASF

Mild fever for 2–3 weeks;

pregnant sows may abort;

reddened then dark,

raised, dry, and necrotic

skin lesions, especially

over pressure points

Gross

lesions

Death occurs

before distinct

lesions form

Spleen enlarged (up to 3 times

normal), dark and friable; multiple

hemorrhages of internal organs,

especially kidneys and heart;

hemorrhagic lymph nodes; edema of

gall bladder and lungs; congestion of

meninges and choroid plexus

Lesions are similar but milder

than acute ASF; spleen may

be 1.5 times normal size;

lymph nodes enlarge but only

mildly hemorrhagic; few

petechia on kidneys

Fibrinous pleuritis, pleural

adhesions, caseous

pneumonia, hyperplastic

lymphoreticular tissues,

nonseptic fibrinous

pericarditis, necrotic skin

lesions

Adapted from: Kleiboeker, S.B. (2002). Swine fever: Classical swine fever and African swine fever. Vet Clin Food Anim 18, 431–451.

Int

roduction and ASF Information

July 2023 1-11

1.4.5 Morbidity and Mortality

For all forms of the disease, morbidity rates are very high. Mortality rates vary by

form. For the peracute form, mortality can reach 100 percent and occur in the

absence of any clinical signs within 7–10 days after exposure to the virus. The

acute form is also associated with mortality rates that approach 100 percent, often

with death occurring within 6–13 days post inoculation. The mortality rate for the

subacute form is dependent on the age of the affected populations; younger pigs

have higher rates (70–80 percent), while older pigs experience significantly lower

rates (less than 20 percent). For those affected by the chronic form of ASF,

mortality is typically low.

1.4.6 Differential Diagnosis

Detection of ASF upon introduction is complex, due to its current clinical

presentations throughout the world and resemblance to various production

diseases present within the United States. When considering a potential diagnosis

of ASF in the United States, the following diseases should also be included in the

differential diagnosis:

19

Classical swine fever,

Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome,

Erysipelas,

Salmonellosis,

Aujeszky’s disease (or pseudorabies) in younger swine,

Pasteurellosis, and

Other septicemic conditions.

1.4.7 Persistence of ASFV

ASFV is a very resilient virus that can withstand low temperatures, fluctuations in

pH, and remain viable for long periods in tissues and bodily fluids. Table 1-2

provides a breakdown of ASFV resistance to physical and chemical action based

on the WOAH ASF Disease Card. These factors must be considered when

determining appropriate response strategies, including disinfection

20

techniques.

19

WOAH. (2021). African Swine Fever. Technical Disease Card.

https://www.woah.org/app/uploads/2021/03/oie-african-swine-fever-technical-disease-card.pdf.

20

www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/ourfocus/animalhealth/emergency-management/CT_disinfectants

Int

roduction and ASF Information

July 2023 1-12

Table 1-2. Resistance of ASFV to Physical and Chemical Action

Source: WOAH Technical Disease Card for African Swine Fever, 2021.

Action Resistance

Temperature

Highly resistant to low temperatures. Heat inactivated by 56°C

or 132.8°F/70 minutes; 60°C or 140°F/20 minutes. This

WOAH guidance must be adapted and validated for field

conditions where use of these temperatures may not be

feasible.

pH

Inactivated by pH < 3.9 or > 11.5 in serum-free medium.

Serum increases the resistance of the virus, e.g., at pH

13.4—resistance lasts up to 21 hours without serum, and 7

days with serum.

Chemicals/disinfectants Susceptible to ether and chloroform. Inactivated by 8/1000

sodium hydroxide (30 minutes), hypochlorites— between 0.03

percent and 0.5 percent chlorine (30 minutes), 3/1000

formalin (30 minutes), 3 percent ortho-phenylphenol (30

minutes) and iodine compounds. Note: disinfectant activity

may vary depending on the pH, time of storage and organic

content.

Survival Remains viable for long periods in blood, feces, and tissues;

especially infected uncooked or undercooked pork products.

Can multiply in vectors (Ornithodoros sp.).

October 2023

2-1

Chapter 2

Framework for ASF Preparedness and

Response

2.1 FOUNDATION OF PREPAREDNESS AND RESPONSE

FAD PReP, including this ASF-specific plan, provides information and specific

guidance on response requirements for an outbreak in the United States. FAD PReP

documents are consistent with emergency preparedness and response principles

found in the National Response Framework (NRF) and in the NIMS.

As mentioned early in Chapter 1, this document does not provide, in detail, general

incident coordination and FAD response. For more information on aspects

discussed in Chapter 2, please refer to the APHIS Foreign Animal Disease

Framework: Roles and Coordination (FAD PReP Manual 1-0) and the APHIS

Foreign Animal Disease Framework: Response Strategies (FAD PReP Manual 2-0).

2.2 USDA AUTHORITIES

2.2.1 The Animal Health Protection Act, 7 U.S. Code 8301

et seq.

The Animal Health Protection Act (AHPA), 7 U.S. Code 8301 et seq., authorizes

the Secretary of Agriculture to restrict the importation, entry, or further movement

in the United States or order the destruction or removal of animals and related

conveyances and facilities to prevent the introduction or dissemination of

livestock pests or diseases. It authorizes related activities with respect to

exportation, interstate movement, cooperative agreements, enforcement and

penalties, seizure, quarantine, and disease and pest eradication. The Act also

authorizes the Secretary to establish a veterinary accreditation program and enter

into reimbursable fee agreements for pre-clearance abroad of animals or articles

for movement into the United States.

Section 421 of the Homeland Security Act, 6 U.S. Code 231 transfers to the

Secretary of Homeland Security certain agricultural import and entry inspection

functions under the AHPA, including the authority to enforce the prohibitions or

restrictions imposed by USDA.

Additionally, the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) gives the APHIS

Administrator authority to determine the existence of disease and the authority to

Fram

ework for ASF Preparedness and Response

July 2023 2-2

prevent the spread of disease through the destruction and/or disinfection of

animals, eggs, and materials as appropriate. As such, it also authorizes APHIS to

appraise and indemnify animals and materials destroyed, provided certain

conditions are met; these conditions include complying with quarantines, adhering

to proper biosecurity protocols, and accurately designating payments between

contract growers and owners of animals (9 CFR 53).

2.2.1.1 EXTRAORDINARY EMERGENCY

The AHPA also authorizes the Secretary of Agriculture—after notice to review

and consultation with certain State or Tribal officials—to declare that an

extraordinary emergency exists because of the presence of a pest or disease of

livestock and because this presence threatens the livestock of the United States (7

U.S. Code 8306). This provides the Secretary with additional authority to hold,

seize, treat, apply other remedial actions to destroy (including preventively

slaughter) or otherwise dispose of any animal, article, facility, or means of

conveyance; and prohibit or restrict the movement or use within a State, or any

portion of a State, of any animal or article, means of conveyance, or facility. Per

this same section (7 U.S. Code 8306(d)(1)), the Secretary is required to

compensate the owner of any animal, article, facility, or means of conveyance the

Secretary requires to be destroyed unless certain conditions are met (these

exceptions are listed in 7 U.S. Code 8306(d)(3). If the owner fails to comply with

such an order, the Secretary may take similar action and recover from the owner

the costs of such action (7 U.S. Code 8306(c)).

The written declaration of Extraordinary Emergency lists specific activities

USDA plans to bring to the State(s). It is not used as a high-handed usurpation of

State authority; rather, it can support the State where its authorities are unclear. In

an ASF outbreak, USDA will consider declaring an Extraordinary Emergency to

allow States to enforce a 72-hour National Movement Standstill of live swine.

Another use may be to readily access and conduct response activities on lands

where feral swine are known or suspected to be infected with ASF; especially in

States which have a patchwork of laws administered through multiple agencies or

departments—Agriculture, Fish & Wildlife, Natural Resources, Game, etc.

Additionally, the federal authority to access private properties with feral swine

may be needed, and the declaration could be written to include that.

2.2.2 The Swine Health Protection Act, 7 U.S. Code 3801 et

seq.

The Swine Health Protection Act (SHPA), 7 U.S. Code 3801 et seq., authorizes

the Secretary of Agriculture in cooperation with States and other jurisdictions to

regulate the treatment and feeding of garbage to swine. Untreated garbage serves

as media where numerous infectious diseases, such as ASF, could be transmitted

via improperly treated garbage. The SHPA and regulations found in 9 CFR 166

contain provisions that prohibit persons from feeding waste unless properly

Framewor

k for ASF Preparedness and Response

July 2023 2-3

treated to kill disease organisms. Those who feed waste are required to hold a

valid license except under certain circumstances outlined in 9 CFR 166. In

addition, § 166.2(c) states that these regulations shall not be construed to repeal or

supersede State law that prohibit the feeding of garbage to swine.

2.3 USDA APHIS VS GUIDANCE

2.3.1 Procedures and Policy for an ASF Investigation, VS

Guidance 12001.4

21

VS Guidance Document 12001.4: Procedures and Policy for Investigation of

Potential FAD/EDI provides guidance for the investigation of potential

FAD/emerging disease incidents. There is also a FAD PReP Ready Reference

Guide on VS Guidance 12001.4 to assist responders during the initial disease

investigation.

2.3.2 Animal Health Policy in Relation to Feral Swine

When APHIS policy supports eradication of an infectious agent/disease/vector,

APHIS VS will seek measures, through 1) movement and testing requirements; 2)

herd plans; and 3) emergency response plans to keep feral swine and domestic

pigs apart and to eradicate ASF from potential reservoirs when eradication is

deemed technically feasible. If eradication is not technically feasible at the time,

measures must be taken to keep these potential reservoirs (feral swine) separate

from domestic pigs. APHIS Wildlife Services (WS) will monitor feral swine for

ASF by testing serum and whole blood samples collected in conjunction with

routine activities to reduce crop damage. As sick and dead feral swine are located

due to non-traumatic events (e.g., disease starvation, old age) APHIS VS will test

for ASF by viral antigen through FAD investigations. APHIS WS will collaborate

with the Area Veterinarian in Charge (AVIC) and State Animal Health Official

(SAHO) to initiate related FAD investigations. Consistent surveillance and

monitoring activities through APHIS VS’ Swine Hemorrhagic Fevers Integrated

Surveillance Plan will increase the likelihood of early detection for ASF by

rapidly locating and testing sick and dead feral swine.

APHIS recognizes that depending on the State(s), the authority and responsibility

for managing feral swine may vary. Primary authority may either be under fish

and wildlife management agencies, agriculture agencies, or there is no clear

authority designated. However, VS has statutory authority under the AHPA to

implement disease control and/or eradication actions for wildlife and feral swine

under certain conditions.

Should wildlife or feral swine be affected by the control and eradication measures

proposed by the Secretary of Agriculture, the Secretary will consult with the

State agency having authority for protection and management of such wildlife.

21

12

001.4 refers to the latest sequential version as of the published date of this response plan.

Fram

ework for ASF Preparedness and Response

July 2023 2-4

2.4 USDA ROLES AND RESPONSIBILITIES OVERVIEW

Understanding the roles and responsibilities of Federal departments or agencies

involved in responding to a FAD incident helps with the effectiveness of a

coordinated emergency response. USDA APHIS responds to animal and

agricultural health issues under USDA statutory authority and is the primary

agency responsible for coordinating response efforts to assist State and local

governments, farmer's associations and similar organizations during an FAD

incident affecting domestic livestock or poultry in accordance with 7 CFR

371.4(b)(5). Incidents will be handled in cooperation with States, Tribes, and

local governments.

Federal response to the detection of an FAD such as ASF is based on the response

structure of NIMS as outlined in the NRF, which defines Federal departmental

responsibilities for sector-specific responses. During an ASF outbreak, the USDA

may request Federal-to-Federal (FFS)

22

support from other Federal departments

and agencies.

If the President declares an emergency or major disaster, or if the Secretary of

Agriculture requests the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) lead

coordination, the Secretary of Homeland Security and DHS assume the lead for

coordinating Federal resources. USDA maintains the lead of overall incident

management. If an ASF outbreak occurs in the United States, the planning

assumption is that the Secretary of Agriculture will declare an extraordinary

emergency.

2.5 USDA APHIS INCIDENT MANAGEMENT

In an ASF incident or outbreak, USDA APHIS provides National Incident

Management Teams (NIMT), coordinates the incident response, manages public

messages, and takes measures to control and eradicate ASF. It is critical that

effective and efficient whole community situation management and clear

communication pathways are employed for a successful response effort.

Synchronized management and organizational structure support control and

eradication actions taken during an ASF outbreak. Accordingly, APHIS employs

NIMS and the Incident Command System (ICS) organizational structures to

manage an ASF response. ICS is designed to enable efficient and effective

domestic incident management by integrating facilities, equipment, personnel,

procedures, and communications operating within a common organizational

structure.

22

FFS refers to the circumstance in which a Federal department or agency requests Federal

resource support under the NRF that is not addressed by the Stafford Act or another mechanism.

Fram

ework for ASF Preparedness and Response

July 2023 2-5

Details for implementing ASF response activities for domestic pig and feral swine

in the field will be available on the ASF FAD PReP website.

2.5.1 Incident Management Structure

The APHIS Administrator is the Federal executive responsible for implementing

APHIS policy during an ASF outbreak; the Administrator is supported by the

APHIS Management Team (AMT) and the Emergency Preparedness Committee

(EPC).

During any significant APHIS-led emergency response, the lead Program Area

Deputy Administrator or Associate Deputy Administrator(s), and/or Director of

the Emergency, Management, Safety, and Security Division (EMSSD) (who is

also the Chair of the APHIS EPC) are authorized to approach the APHIS Office

of the Administrator (OA) to recommend that an APHIS Multiagency

Coordination (MAC) group be stood up to support ongoing response. Many of the

MAC functions may be delegated to the VS Deputy Administrator (VSDA), who

is the Chief Veterinary Officer (CVO) of the United States. The VSDA is

supported by the VS Executive Team (VSET) to coordinate policy.

An APHIS National Incident Coordination Group (ICG), led by an Incident

Coordinator and a Deputy Incident Coordinator, is immediately established to

oversee the functions and response activities associated with the incident. This

ICG is flexible and scalable to the size and scope of the incident and works

closely with unified Incident Command (IC) field personnel, in a unified Incident

Management Team (IMT). The ICG also coordinates with any MAC Group that is

established at the APHIS or USDA level, based on the specific incident. For

example, in the 2022-2023 Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza outbreak in the

United States, the APHIS MAC Group was formed due to the size, scope, and

impact of the incident.

In addition to policy and incident coordination, the APHIS Administrator, AMT,

the VSDA, and VSET communicate, collaborate, and coordinate with relevant

industry associations, the National Assembly of State Animal Health Officials and

National Association of State Departments of Agriculture, public health agencies

(Federal and State), and other partners in a whole community approach.

2.5.2 Field Organization

At the beginning of an incident, the SAHO or designee, and the VS AVIC, or

designee, initially serve as Co-Incident Commanders in a unified IC Structure.

The AVIC will be relieved when a State and/or APHIS IMT is stood up, and an

Incident Command Post (ICP) is established. In a large ASF incident, there may

be multiple ICPs and full VS NIMTs may not be dispatched to each location; to-

date, VS has five standing NIMTs. In any situation, ICPs will remain a unified

State-Federal IC organizational structure.

Fram

ework for ASF Preparedness and Response

July 2023 2-6

If the outbreak involves more than one incident, more than one IC is likely to be

established. An Area Command (AC) may also be established. In this case,

individual Incident Commanders responsible for potentially multiple unified

IMTs would report to the AC. AC organizational structures may not be

established or appropriate in all incidents; in many cases, the ICG will perform

the same functions as an AC. For more information on a single incident and

multiple incident coordination along with a full NIMT configurations, see APHIS

Foreign Animal Disease Framework: Roles and Coordination (FAD PReP

Manual 1-0).

July 2023 3-1

Chapter 3

ASF Outbreak Response Goals and Strategy

3.1 RESPONSE GOALS

The APHIS goals of an ASF response are to (1) detect, control, and contain ASF

in swine as quickly as possible; (2) eradicate ASF using strategies that seek to

stabilize animal agriculture, the food supply, the economy, and to protect public

health and the environment; and (3) provide science- and risk-based approaches

and systems to facilitate continuity of business (COB) for non-infected animals

and non-contaminated animal products.

Achieving these three goals will allow individual livestock facilities, States,

Tribes, regions, and industries to resume normal production as quickly as

possible. They will also allow the United States to regain ASF-free status without

the response effort causing more disruption and damage than the outbreak itself.

3.2 EPIDEMIOLOGICAL PRINCIPLES

The control and eradication of ASF in swine is based on four epidemiological

principles:

1. Prevent contact between ASFV and swine. This is accomplished

through:

a. quarantine of infected swine and movement controls in the Control

Area (Infected Zone [IZ] + Buffer Zone [BZ]),

b. aggressive contact tracing of the Infected Premises, including

premises epidemiologically-linked through a network relationship,

where appropriate, and

c. enhanced biosecurity procedures that include preventing contact

between feral swine and domestic pigs.

2. Stop the production of ASFV by infected or exposed swine. This is

accomplished by mass depopulation (and disposal) of infected and

potentially infected swine; prioritization may increase effectiveness.

3. Prevent the transmission of ASFV by vectors.

4. Prevent ASFV from becoming established in feral swine populations.

AS

F Outbreak Response Goals and Strategy

July 2023 3-2

3.3 CONTROL AND ERADICATION STRATEGIES

The United States’ control and eradication strategy for ASF in swine is based on

international standards and USDA APHIS FAD PReP response standards.

1. Quarantine Infected Premises.

2. Establish Control Areas (movement controls) around Infected Premises.

3. Conduct aggressive contact tracing of Infected Premises, including premises

epi-linked through a network relationship, where appropriate.

4. Conduct stamping-out to eradicate ASF virus.

5. Conduct surveillance in Control Areas and Free Areas.

6. Implement enhanced biosecurity.

7. Consider vaccination; however, there is currently no vaccine approved for

emergency use in the United States for ASFV in swine.

APHIS acknowledges there may be significant challenges in controlling and

eradicating ASF, depending on the outbreak (e.g., if feral swine are infected). In

any instance, movement control measures are critical since ASF is easily spread

by infected swine and contaminated fomites. It is essential movement controls are

science- and risk-based to minimize disruption to normal business and to facilitate

the appropriate allocation of incident resources. To assist in doing so, contact

tracing will be emphasized in addition to the standard Control Area movement

controls. Contact Premises outside of the Control Area will be aggressively

investigated in order to rapidly detect new cases.

3.3.1 Defining Stamping-Out as a Response Strategy

For ASF, stamping-out is the depopulation of clinically affected swine and, as

appropriate, swine exposed to the virus. Depopulation and disposal of Infected

Premises or Pigs must be conducted in a biosecure manner to prevent further

disease spread. Box 3-1 lists the key elements of stamping-out. Further detail on

Depopulation, Disposal, and Decontamination (3D) activities are discussed in

Section 4.11.

ASF O

utbreak Response Goals and Strategy

October 2023 3-3

Box 3-1. ASF Stamping-Out Strategy

3.3.1.1 WOAH DEFINITION OF STAMPING-OUT

“Stamping-out” is defined in the WOAH Terrestrial Animal Health Code (2022)

Glossary, as:

a policy designed to eliminate an outbreak by carrying out under the

authority of the Veterinary Authority the following: (a) the killing of the

animals which are affected and those suspected of being affected in the

herd or flock and, where appropriate, those in other herds or flocks which

have been exposed to infection by direct animal to animal contact, or by

indirect contact with the causal pathogenic agent; animals should be killed

in accordance with Chapter 7.6

; (b) the disposal of carcasses and, where

relevant, animal products by rendering, burning or burial, or by any other

method described in Chapter 4.13; (c) the cleansing and disinfection of

establishments through procedures defined in Chapter 4.14.

3.3.2 Zones and Areas in Relation to Stamping-Out

Figure 3-1 illustrates an example of a stamping-out strategy where an Infected

Premises or an infected feral swine are depopulated. See Section 4.5.1 for further

information on zones and areas for an ASF outbreak response.

Stamping-Out Critical Goals

• After the identification of an Infected Premises or Pig, all infected swine will be

depopulated in the safest

and most humane way possible.

• As a general goal, APHIS recommends that depopulation and disposal activities be

completed as soon as possible after approval for indemnity payment. That said,

identifying a specific depopulation response time goal is not an absolute requirement.

• Assessing possible depopulation and disposal of swine on any farm location will require

proper planning and resources to ensure health and safety of the owner, grower and

responders, and proper planning and resources will be needed to ensure animal welfare.

In some cases, other swine, such as those on Contact Premises, may also be

depopulated.

• To be most effective in stopping disease transmission, it may be necessary to prioritize

depopulation (of premises or even within a single premises) based on clinical signs and

epidemiological information.

• Public concerns about stamping-out require a well-planned and proactive public

relations liaison campaign.

• Care should be taken to consider the mental health implications for owners and

responders.

AS

F Outbreak Response Goals and Strategy

July 2023 3-4

Figure 3-1. Example of Zones and Areas in Relation to Stamping-Out

3.3.3 Zones and Areas in Relation to Contact Tracing

Figure 3-2 illustrates an example of an epidemiologic network where contact

tracing from the first Infected Premises (IP1) identified an epidemiologically-

linked Contact Premises outside of the initial Control Area. This additional

Infected Premises (IP2) triggered a new Control Area that led to additional

Contact Premises. All high-risk direct Contact Premises that are traced from/to an