Copyright 2021 Terner Center for Housing Innovation

For more information on the Terner Center, see our website at

www.ternercenter.berkeley.edu

A TERNER CENTER REPORT - FEBRUARY 2021

Strategies to Lower Cost and

Speed Housing Production:

A Case Study of San Francisco’s

833 Bryant Street Project

AUTHOR:

NATHANIEL DECKER, POST-DOCTORAL SCHOLAR

A TERNER CENTER REPORT - FEBRUARY 2021

2

Executive Summary

Across the United States, the high costs

of developing subsidized housing hinders

eorts to address the aordability crisis

of low- and moderate-income families

and provide homes for unhoused individ-

uals. The number of people paying half or

more of their income for housing remains

at historically high levels, and after many

years of decline, homelessness has been

on the rise, particularly in California.

Levels of public subsidy for housing have

not kept pace with these growing needs.

At the same time, higher costs per unit to

build aordable housing mean that states

and localities produce fewer units with

the same amount of subsidy, even as more

people are in need of these units.

While these problems exist across the

U.S., San Francisco is exceptional both in

terms of the need for aordable housing

and the high cost to provide those homes.

Not only has homelessness in San Fran-

cisco worsened in the past ve years, but

the COVID-19 pandemic has put even

more stress on extremely low-income

renters and placed many at greater risk of

becoming unhoused.

Permanent supportive housing (PSH),

where residents are provided with an

apartment in conjunction with a range

of services, is a proven method to reduce

homelessness and has even been shown

to require less public expenditure than

leaving people unhoused. The city of San

Francisco has committed to building more

PSH but is not currently building at the

pace required to meet the need.

A number of factors pose barriers to

building more PSH housing in the city.

Development timelines for aordable

projects in San Francisco have typically

stretched to 6 years or longer and devel-

opment costs have reached $600,000 to

$700,000 per unit. This is a far slower and

more costly process than other dense cities

in high-cost areas, even other high-cost

areas in California. While there is wide-

spread agreement in the public and private

sectors that the length of development

timelines and high price of construction

are problems, they have yet to be addressed

in a comprehensive way.

These challenges have been a focal point

for the Chronic Homelessness Initiative

launched by Tipping Point Community—a

philanthropic organization in the Bay Area.

The goal of the Initiative is to reduce chronic

homelessness by 50 percent between 2017

and 2022. To help meet that goal, Tipping

Point partnered with the San Francisco

Housing Accelerator Fund (HAF) to: (i)

develop a new model for building quality

PSH at lower cost, and (ii) establish a

revolving fund to support multiple proj-

ects and leverage additional funding. They

rst set out to build new housing in under

three years and at a cost of $400,000 or

less per unit. Tipping Point Community

contracted with the HAF to create and

structure the Homes for the Homeless

Fund and lead project investment and

implementation eorts. The Homes for the

Homeless Fund’s rst project, a permanent

supportive housing development currently

under construction at 833 Bryant Street,

is on target to meet those goals, which are

substantially below the cost and timelines

that are typical for San Francisco proj-

ects. The Bryant Street project is funded

in part by the Initiative through the San

Francisco Housing Accelerator Fund with

Mercy Housing acting as the developer. It

is expected to be completed in July 2021.

A TERNER CENTER REPORT - FEBRUARY 2021

3

This brief assesses 833 Bryant’s develop-

ment process to date, with a specic focus

on: (i) understanding how timelines and

costs for 833 Bryant compare to San Fran-

cisco norms, (ii) how the project achieved

projected time and cost savings, and (iii)

what lessons can be taken from this project

for both the public and private sectors. To

inform this analysis, we interviewed the

relevant stakeholders involved with the

project, and we analyzed the nancials of

833 Bryant, a number of comparison proj-

ects, and data on aordable housing devel-

opment costs in the area more generally.

The results of our analysis nd that 833

Bryant is on target to be completed 33

months after land acquisition, and we esti-

mate that the development cost is set to

come in at $382,917 per unit. To put that in

perspective, 833 Bryant is on pace to build

homes, conservatively, about 30 percent

faster and at 25 percent less cost per unit

the similar project.

We determined that the project was able

to achieve these time and cost savings

through a package of four cost eciencies:

1. Committing to dened and ambi-

tious cost and timeline goals.

Tipping Point Community estab-

lished dened and ambitious cost and

timeline goals up front, which led the

development team to innovate in the

nancing and design of the project.

2. Deploying unrestricted capital

to fund many costs during

construction.

833 Bryant beneted from a large pool

of exible funding unrestricted by the

regulations that typically come with

subsidies. This capital came from the

Homes for the Homeless Fund estab-

lished by Tipping Point and HAF. In

contrast to most funding for aordable

housing, which requires detailed paper-

work, or specied returns, these funds

had no terms other than to support the

development of PSH deals done quickly

and at relatively low cost. Further-

more, while it was understood that,

ideally, these funds would be revolved

to support additional developments,

HAF and Tipping Point were willing to

accept the risk that the funds would not

be returned from the project.

3. Receiving approval for the

Streamlined Ministerial

Approval Process under Senate

Bill 35.

This law allowed 833 Bryant to move

through the permitting process much

faster and with less risk.

4. Using o-site construction of

apartment units.

O-site construction of apartment

units at Factory_OS allowed the

project to simultaneously build units

and engage in site work, shortening the

development timeline.

The savings achieved by this package of

eciencies are greater than the sum of its

parts and taken together resulted in a far

more exible and streamlined development

process. The timeline savings of the project

are particularly important. Subsidized

housing often follows a more convoluted

development process than unsubsidized

housing and by streamlining the process,

833 Bryant was able to avoid many of

these direct costs. Faster timelines also

meant locking in lower construction costs.

Between 2008 and 2018, multifamily

construction costs in the region rose by

over 8 percent annually. Timeline savings

are especially important for PSH, as slower

development means unhoused individuals

A TERNER CENTER REPORT - FEBRUARY 2021

4

remain homeless longer. 833 Bryant’s

quick timeline means that 145 homeless

people will be housed months or even

years sooner than if the project had been

developed through the typical processes.

And there are lessons to be learned that

extend beyond PSH projects. 833 Bryant’s

goals of cost and time eciency led the

development team to a new way to produce

aordable units, faster, and for less subsidy.

Their focus on cost and time eciencies is

applicable nationwide, as the scarcity of

aordable housing coupled with limited

subsidy dollars is a major issue across the

country.

Introduction

The cost to develop aordable units has

a major impact on how many low-in-

come people, including those currently

unhoused, can be stably housed. Aord-

ability, especially for low-income renters is

at crisis levels. After many years of declines,

homelessness has been on the rise in the

U.S., particularly in California. Levels of

public subsidy for housing have not kept

pace with this rising need. Higher costs

per unit to build aordable housing mean

that states and localities produce fewer

units with the same amount of subsidy,

even as more people are in need of these

units. While these problems exist across

the U.S., San Francisco is exceptional both

in terms of the need for aordable homes

and the high cost to build them. Even

with new local subsidies coming online to

support aordable housing construction in

the city, the number of new units required

far outstrips available resources.

Tipping Point Community—a Bay Area

philanthropic organization—launched its

Chronic Homelessness Initiative in 2017

with the goal of reducing homelessness

in the region by half in ve years. A key

component of that initiative is to pilot

new ways to develop quality permanently

supportive units in San Francisco in under

three years and at a cost of $400,000 or

less per unit—signicantly faster and

cheaper than is typical for such projects in

the city. The rst development to receive

funds through the program is currently

under construction at 833 Bryant Street

and is scheduled to be completed in July

2021.

This analysis evaluates the progress of the

Bryant Street project to date, comparing

it to aordable development norms in

the city and to specic newly constructed

PSH projects. The remainder of the report

provides context for the project’s devel-

opment, an overview of methods used to

assess its development timeline and nan-

cials and identies key elements that have

contributed to Bryant Street’s projected

time and cost eciencies. The report

concludes with recommendations for ways

in which other projects—in San Francisco

and beyond—can produce housing rela-

tively quickly and at lower cost, and how

the public sector can change laws and poli-

cies to facilitate the quick, ecient devel-

opment of desperately needed homes for

unhoused individuals.

A TERNER CENTER REPORT - FEBRUARY 2021

5

Background

San Francisco’s Homelessness

Crisis and the Need for Permanent

Supportive Housing

Cost eciency in the production of subsi-

dized housing is essential in the face of

the high levels of need and limited subsidy

funds. The number of people facing dire

housing needs in the U.S. has been at

historically high levels for the past decade.

1

Levels of subsidy, particularly from the

federal government, have not kept pace

with rising need, leaving a larger portion

of extremely low-income families without

access to the housing assistance for which

they are eligible.

2

After many years of

declines, levels of homelessness in the U.S.

began to rise in 2015, driven in part by

growing aordability challenges.

3

California faces especially high aord-

ability pressures and has seen especially

sharp increases in the costs of developing

subsidized housing. Construction costs per

unit for Low-Income Housing Tax Credit

(LIHTC) developments rose 11 percent

in real terms from 2011 to 2015 in Cali-

fornia, even as costs held at in other parts

of the country.

4

Increases in the homeless

population in the state have also outpaced

national trends since 2011, and the number

of people experiencing homelessness in

San Francisco has risen even faster than

the state level, growing more than 40

percent from 2011 to 2019 (Figure 1). In

addition, the population of people expe-

riencing chronic homelessness, dened

by HUD as people who have experienced

homelessness for a year or longer and also

have a disabling condition that prevents

them from securing work or housing, has

risen from 1,977 in 2011 to 3,030 in 2019

(Figure 1).

5

Note that these numbers do

not reect the impacts of the COVID-19

pandemic over the past year, which is

poised to deepen the homelessness crisis.

6

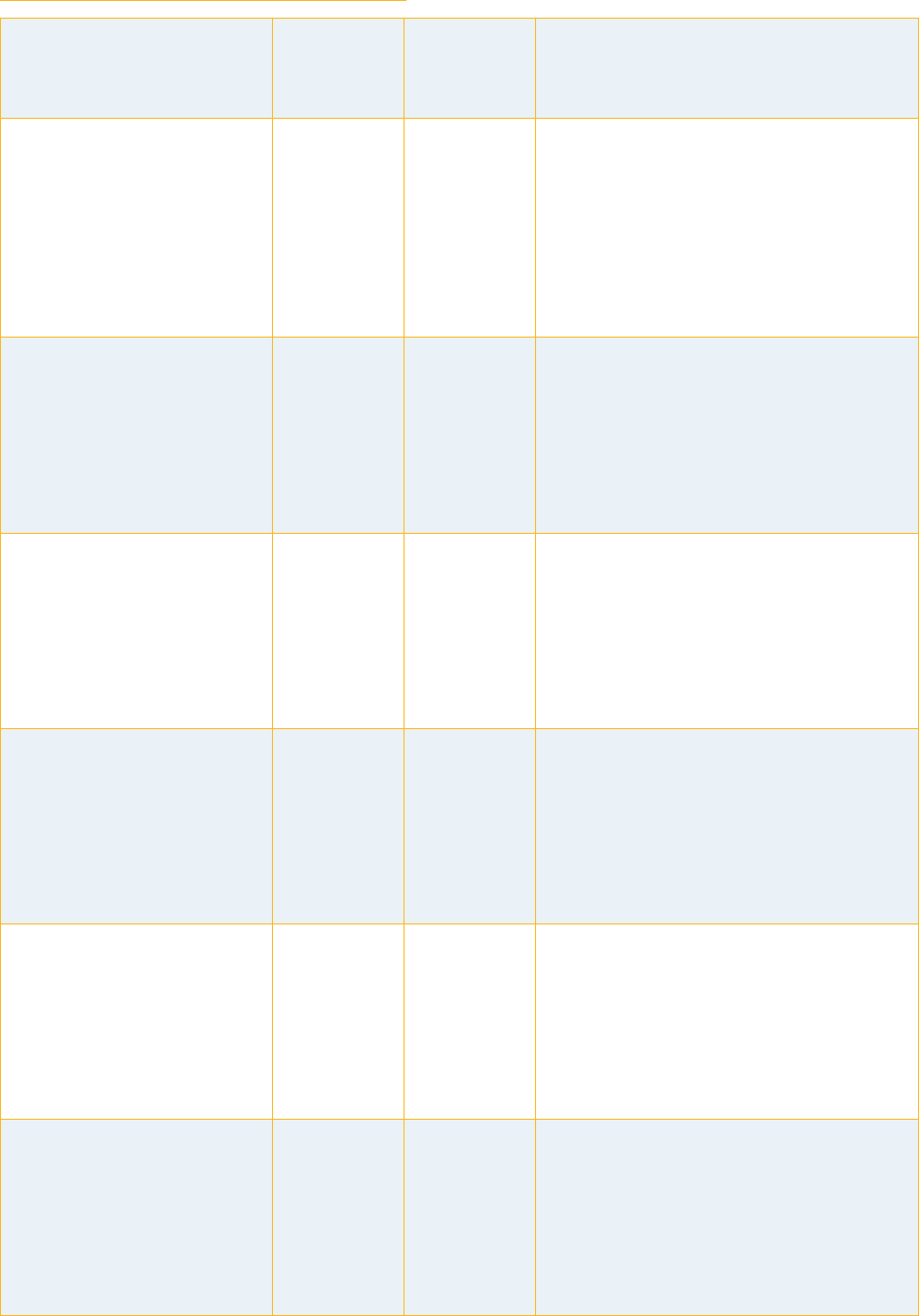

Figure 1: Homelessness in San Francisco

0

2,000

4,000

6,000

8,000

10,000

2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019

Total People Experiencing Homelessness People Experiencing Chronic Homelessness

A TERNER CENTER REPORT - FEBRUARY 2021

6

Permanent supportive housing (PSH) is a

proven solution to homelessness, partic-

ularly for people experiencing chronic

homelessness, a population with rates

of substance abuse and physical and

mental disability that are higher than the

unhoused population in general. Substan-

tial evidence shows that so-called “housing

rst” strategies, where unhoused people

are rst provided with a home and then

oered a range of supportive services,

lead to long-term stability for the chron-

ically homeless and can even result in

less public-sector expenses than leaving

people unhoused.

7

The city has identied

the production of PSH as a priority and

has generated 550 units since 2016, with

hundreds more in the pipeline.

8

However,

the challenges are currently outpacing the

solution. One reason for this is the excep-

tionally slow development timeline to build

units, coupled with the exceptionally high

cost to build new housing, particularly

aordable and supportive housing, in San

Francisco.

9

Piloting a New Approach to

Permanent Supportive Housing

Development: 833 Bryant Street

As part of its Chronic Homelessness

Initiative, Tipping Point was interested in

eective ways to increase and accelerate

the production of new supportive housing.

Tipping Point partnered with the San

Francisco Housing Accelerator Fund

(HAF) to develop a concept to increase

the speed of construction and decrease

the cost to build by pairing exible

private funds with long-term sustainable

government funding. After developing a

program model together, Tipping Point

provided $50 million to the HAF to create

the Homes for the Homeless Fund with the

explicit goal of developing PSH faster and at

lower cost than similar projects. The Fund

itself provides a structure that is meant

to encourage speed and cost eciency. Its

mission is to provide aordable housing,

but as a public-private partnership it has

more exibility and can operate more

nimbly than public agencies. This was a

particular advantage for 833 Bryant, as

HAF was able to move quickly to acquire a

promising site that was privately held, thus

avoiding the often-lengthy processes that

accompany the development of publicly-

held sites. While the Fund has acted as a

lender to a number of projects across the

city, this is the rst deal that uses the capital

provided by Tipping Point Community and

where HAF has taken a more active role in

development.

The site at 833 Bryant had originally been

used as surface parking and was zoned

as Service/Arts/Light Industrial. Prior

to acquisition, HAF assembled the devel-

opment team and worked with the City

on a zoning amendment that allowed the

construction of aordable housing on

sites like 833 Bryant. The site was enti-

tled in six months for the construction of

145 units permanent supportive housing

reserved for people who have experienced

chronic homelessness, plus one unit for the

manager.

HAF purchased the site in October

2018 using unrestricted capital that was

provided by Tipping Point and was not

subject to the same requirements or

expectations typically attached to private

or public subsidy sources. HAF also used

these funds to provide a low-cost loan for

predevelopment and initial construction

expenses (including a substantial portion

of the o-site construction). These funds

were partially returned to HAF with the

deployment of a $33,282,714 mortgage,

funded with tax-exempt private activity

A TERNER CENTER REPORT - FEBRUARY 2021

7

bonds. The HAF construction funds will

be fully returned with the deployment of

$21,673,000 in associated LIHTC equity.

10

Further public subsidies come in the form

of an operating lease from the city of $1.4

million per year and a master lease from

the city of $1.9 million per year, with

payments beginning in 2022. Additionally,

HAF is providing subsidy directly to the

deal by providing the site to the city after

a 30-year ground lease, and by providing

development services without compensa-

tion, thus allowing for a lower collected

developer fee than is standard.

Tipping Point and HAF partnered to

launch the rst project, jointly interviewing

and choosing an architect, developer,

contractor, and modular company. Mercy

Housing was chosen to act as developer on

the project. The units are all small studios

of about 260 square feet each, which is

appropriate given that the vast majority

(94 percent) of people experiencing chronic

homelessness in San Francisco are single

adults without children.

11

The units were

constructed o-site by Factory_OS.

Methods

Research for this project consisted of inter-

views with members of the 833 Bryant

development team, analysis of the project’s

nancials and development process, and

comparisons with aggregated development

cost data and the nancials of four specic

developments. The teams at both HAF

and Mercy have many years of experience

developing housing in San Francisco and

were able to describe in detail how the

development of 833 Bryant diered from

other, similar developments.

Establishing whether the project achieved

its cost and development timeline reduc-

tion goals is not a straightforward question

because, in a number of important ways,

833 Bryant is an atypical project. At some

level of detail, every development is unique.

The development process in San Francisco

is unlike the process in even adjacent cities

like Oakland. The specics of development

sites also vary, the costs of labor and mate-

rials change, and the methods of nancing

projects are rarely the same from project

to project. There have been many multi-

family aordable housing projects in the

city of San Francisco in the past few years,

though non-supportive housing projects

rarely have all or nearly all of their units as

studios. Permanent supportive housing is

often 100 percent studios, but 833 Bryant’s

units are notably smaller than typical PSH

in the city.

12

For this reason, we use a few reference

points to measure the project’s cost savings

and reductions in development time-

line. The rst reference point is averaged

costs for subsidized multifamily housing

construction in San Francisco. Data on

construction costs are very limited, and

this portion of the analysis relies on data

on development costs by the Terner Center

(from application materials for 9 percent

LIHTC projects) in California and data

from the San Francisco Mayor’s Oce of

Housing and Community Development

(MOHCD) on multifamily projects they

have recently funded. To account for the

fact that 833 Bryant is 100 percent small

studio units we use cost averages in terms

of costs per residential square foot and

gross square foot, in addition to cost per

unit. Unlike Single Room Occupancy proj-

ects (SROs), 833 Bryant is composed of

full units, with a bathroom and kitchen.

Costs per unit for microunit projects look

low because more units are arranged into

the oor area of the project, whereas costs

per residential square foot appear high

because more expensive facilities like

A TERNER CENTER REPORT - FEBRUARY 2021

8

kitchens and bathrooms are also arranged

into the residential area of the project. It

is unclear whether to expect costs per

gross square foot of 833 Bryant to be high

or low because—though the residential

areas will cost more—833 Bryant is a very

ecient building, with little space neces-

sary for circulation and relatively little

space programmed for non-apartment

uses. Non-apartment uses are common in

aordable development in San Francisco.

We also compare 833 Bryant to four

specic projects: 1064 Mission, Mission

Bay Block 9, Casa de la Misión, and Parcel

O. The rst three are new construction, 100

percent small studio apartment, perma-

nent supportive housing projects in San

Francisco, all of which are currently under

construction. These projects use some, but

not all, of the cost saving measures used in

833 Bryant. The fourth project, Parcel O,

is not similar to 833 Bryant, as it is mostly

family housing, with unit sizes far larger

than 833 Bryant. The project’s fraught

design and development process, however,

provides a useful comparison to the rela-

tively smooth process for 833 Bryant.

Findings

Estimated Cost for 833 Bryant &

Savings Approach

833 Bryant is on pace to achieve a cost of

approximately $382,917 per unit. The total

development cost for the project is about

$100,000 higher per unit, but this gure

does not provide a fair comparison of 833

Bryant’s costs to other projects. Table 1

shows the adjustments we made to the costs

of 833 Bryant and other projects to arrive

at gures that are useful for comparisons.

We exclude acquisition costs because

many aordable projects in the city are

developed on publicly owned land, which

is typically ground leased to the devel-

oper. Furthermore, the cost and timeline

reduction objectives of 833 Bryant are in

many ways separate from the issues of

site acquisition. Policy objectives such as

access to jobs or quality schools or transit,

for example, may justify higher acquisition

costs. Like many PSH developments, 833

Bryant includes a large developer fee, only

a portion of which is actually collected by

Table 1: Adjustments Made to 833 Bryant Project Costs for Comparison

833 Bryant Project Per Unit Per GSF Per RSF

Total Development Cost $68,635,195 $470,104 $1,111 $1,572

- Acquisition Cost $ 8,273,523

- Recontributed Developer Fee $ 5,405,858

+ Reduced Developer Fee $ 950,000

Cost for Comparisons $55,905,814 $382,917 $905 $1,280

A TERNER CENTER REPORT - FEBRUARY 2021

9

the developer, while the rest is recontrib-

uted to the project to boost LIHTC-eligible

costs. In the case of 833 Bryant the collected

developer fee was reduced even further (by

$950,000) relative to a typical PSH devel-

opment. Mercy Housing, as the developer,

agreed to take a reduced fee because HAF

assumed a substantial portion of the devel-

opment work, particularly entitling the site

and leading negotiations of the subsidy

lease with the city. The reduced fee can be

considered a subsidy provided by HAF to

the project and is thus added to the total

development cost. However, 833 Bryant

also includes about $900,000 of interest

and fee costs for the HAF construction

loan, which are costs that are not incurred

in most similar aordable developments,

where construction costs would typically

be supported by MOHCD subsidy. We do

not adjust the cost downward to account

for these interest and fee costs, because at

the moment deal structures like this one—

reliant on unrestricted capital—will need

to support such costs.

833 Bryant diers from the “business-

as-usual” development of PSH in San

Francisco in a number of ways, but a

package of four cost eciencies have

worked together to result in lower per-unit

costs and a shorter development timeline.

13

Specically, the project partners:

1. Committed to dened and ambi-

tious cost and timeline goals. The

development team was committed

to building quality PSH at a cost of

$400,000 per unit or less and complete

the project within three years. These

goals drove many of the important

decisions in the development process.

2. Deployed unrestricted capital

during construction. Tipping Point

Community provided HAF with capital

whose sole purpose was to develop PSH

faster and at lower cost than is typical.

Tipping Point was willing to accept the

risk of losing some of this capital to

achieve these savings.

3. Received Streamlined Ministe-

rial Approval under SB 35. The

Streamlined Ministerial Approval

Process, signed into law in 2017,

provides an entirely ministerial enti-

tlement process on a xed timeline for

certain aordable housing projects in

some jurisdictions in California, and

allows these projects to avoid delays

caused by CEQA.

4. Used o-site construction. 833

Bryant’s units were constructed o-site

by Factory_OS, a union-staed facility

in Vallejo, CA. O-site construction

allowed the project to simultane-

ously engage in site work and building

construction.

All four innovations work together in 833

Bryant, resulting in a method of develop-

ment that is substantially dierent, not

only from “business-as-usual,” but also

from developments that used only one or

two of these four measures (Table 2). The

sum of savings achieved by this package is

greater than the parts.

A TERNER CENTER REPORT - FEBRUARY 2021

10

833 Bryant’s Package of Cost

Eciencies Is on Target to Bring

Units Online, Conservatively, 30

Percent Faster and at 25 Percent

Lower Cost Per Unit Than Similar

Developments

The three projects that are most similar to

833 Bryant provide the best benchmarks

to estimate how eective the project was

at achieving its cost and timeline reduc-

tion goals. Table 3 summarizes these proj-

ects’ per-unit costs, the average size of the

units, and the scope of the projects, along

with recent LIHTC averages in San Fran-

cisco and the costs of recent MOHCD proj-

ects. 1064 Mission, Mission Bay Block 9,

and Casa de la Misión are very similar to

833 Bryant though Bryant cost between

37 percent to 25 percent less on a per unit

basis. While the residential portion of these

projects are very similar to 833 Bryant,

all of the projects include non-housing

components that are more substantial than

833 Bryant. (833 Bryant includes a very

small retail space.) Non-housing compo-

nents are common in PSH developments

in San Francisco and contribute to higher

per-unit costs. 833 Bryant was acquired

in October of 2018 and is on target to be

nished in July of 2021, for a development

timeline of 33 months, which is fast for

San Francisco. San Francisco is notorious

for the exceptionally long time required to

take projects from acquisition to comple-

tion. The extended timelines are largely

due to public processes, and aordable

projects face even longer delays because

of the additional requirements that come

with public subsidies.

14

On average, multi-

family projects in San Francisco took 76

months, or 6.3 years, from permitting to

completion.

15

(833 Bryant submitted its

permitting application two months after

acquisition, in December 2018.)

16

The comparison projects all took longer to

complete than 833 Bryant, though direct

Table 2: Comparison Projects and the Package of Cost Efficiencies

Defined,

Ambitious Cost

& Time Goals

Unrestricted

Capital During

Construction

Streamlined

Ministerial

Approval

Process

Off-Site

Construction

833 Bryant Yes Yes Yes Yes

1064 Mission Time Goal Only No Yes Yes

Mission Bay Block 9 No No Yes Yes

Casa de la Misión No Yes Yes No

Parcel O No No No No

A TERNER CENTER REPORT - FEBRUARY 2021

11

Table 3: Comparison Projects’ Costs and Scope

$ Per Unit

Average Unit

Size

Scope

833 Bryant $382,917 260 sq. ft.

• 61,800 gross sq. ft.

• 146 units

• 500 sq. ft. retail space

• 2,355 sq. ft. services and office space

• 2,858 sq. ft. community outdoor

space

1064 Mission $509,826 350 sq. ft.

• 175,123 gross sq. ft.

• 258 units

• 20,000 sq. ft. clinic

• 5,400 sq. ft. commercial kitchen &

culinary training center

Mission Bay Block 9 $573,218 330 sq. ft.

• 99,150 gross sq. ft.

• 141 units

• 18,000 sq. ft. landscaped community

garden

Casa de la Misión $611,981 300 sq. ft.

• 25,757 gross sq. ft.

• 45 units

• 1,100 sq. ft. retail

LIHTC San Francisco

Average

16

$639,555

Average unit

sizes are

substantially

larger than

833 Bryant

Varies

Recent MOHCD Average $736,000

Average unit

sizes are

substantially

larger than

833 Bryant

Varies

A TERNER CENTER REPORT - FEBRUARY 2021

12

comparisons are dicult because these

projects followed dierent development

processes (Table 4). 1064 Mission, Mission

Bay Block 9, and Parcel O, for example,

all were developed on public land, which

complicated the acquisition. For these

projects we calculate the timeline starting

from the selection of the developer. We

estimate that 833 Bryant is on track to be

completed at least 30 percent faster than

1064 Mission, which has the next shortest

projected timeline. We consider this to be

a conservative estimate because, though

1064 Mission is larger than 833 Bryant,

it was developed faster than is typical.

1064 Mission moved quickly because of

the federal government’s requirement that

the project be completed and occupied

within three years of the property transfer

agreement.

(We omit Casa de la Misión from the time-

line comparison because of that project’s

especially complex development process.

Mission Neighborhoods Center purchased

the site in 1994. The project went through

various programming ideas until 2012,

when initial renderings for a multifamily

project were drawn up. However, the

developer then spent years working with

the city to get the site into a developable

conguration. Thus, it could reasonably

be said that the development process of

Casa de la Misión took 43 months, starting

from the beginning of the process to get

the site into a developable conguration;

or 8 years, starting from the selection the

developer of the site; or 26 years, starting

from the initial purchase of the site.)

Delays in development not only mean

that those currently in need of housing

need to wait longer to be housed, but they

also increase development costs. Delays

increase costs in a number of ways but

some of the biggest increases come from

rising construction costs. We calculated

that multifamily construction costs in San

Francisco rose 119 percent between 2008

and 2018, for an annualized increase of

over 8 percent.

17

Thus a year’s delay for

a project like 833 Bryant would not only

mean 145 homeless people would remain

on the streets for an additional year, but

also that the same project would cost an

additional $500,000.

A TERNER CENTER REPORT - FEBRUARY 2021

13

Table 4: Development Timelines of Comparison Projects

2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 Timeline

833 Bryant

Acquired

October

Started

construction

March

To be

completed

July

33 months

1064 Mission

Selected

through

Request for

Proposal

(RFP)

February

Site

transferred

from Federal

Government

Started

construction

March

To be

completed

December

47 months

Mission Bay

Block 9

Selected

through RFP

November

Received

approval

through

Office of

Community

Investment

and Infra-

structure

(OCII)

OCII

approvesd

design

Modular

vendor

selected

Started

construction

August

To be

completed

December

49 months

Parcel O

Selected

through RFP

December

Applied for

entitlements

February;

Conditional

Use Permit

filed August

Project

approved

Started

construction

October

Completed

September

57 months

A TERNER CENTER REPORT - FEBRUARY 2021

14

Commitment to Dened Cost and

Time Goals Pushed the Project to

Innovate in Both Financing and

Design

Dened and ambitious cost and timing

targets are not standard in the devel-

opment of aordable housing. Housing

subsidy programs are often structured in

ways that provide no incentive to reduce

development costs. For example, LIHTC

projects have substantial construction

contingencies in their budgets and receive

LIHTC subsidy in proportion to the size

of the contingency (up to a dened limit).

Developers who are on track to not fully

use their construction contingency often

add scope items to the project in order to

use the contingency with the associated

subsidy. Public input processes can also

impede cost eciency. While local resi-

dents may want people experiencing home-

lessness to have homes, the public input

process can result in proposed changes that

push up per-unit costs. The private sector

also doesn’t provide incentives for cost

eciency. There are no major architecture

awards for cost-eective design and devel-

opers are similarly rewarded far more for

splashy but expensive projects than they

are for projects that provide quality units

as quickly as possible and using as little

subsidy as possible. In a world of limited

subsidy this set of incentives means fewer

units, and, in the case of PSH, more people

living in shelters or on the street.

The commitment to these goals drove most

of the important decisions in the nancing

and design of 833 Bryant and resulted in

a nancing structure and development

process that is quite dierent from San

Francisco norms. Early on the team real-

ized that accepting local subsidies during

construction would require compli-

ance with regulations that would make

it impossible to reach the cost and time

goals. This led to the use of unrestricted

capital from Tipping Point and bonds from

the state. Similarly, the major aspects of

the design of the project—from the use of

a single, small-unit design to the number

of units on the site and the site program-

ming—were also driven by the need to

meet the project’s cost and timeline goals.

The nal design of the project is not typical

for PSH in the city. The city’s public agen-

cies have policies that encourage larger

units and higher-cost design items (such

as large windows) based on the theory that

these features will make residents work

harder to maintain their units, resulting

in improved housing stability. The goals

also drove the team to tap existing but

relatively new and non-traditional devel-

opment methods such as the Streamlined

Ministerial Approval Process and o-site

construction.

1064 Mission provides a useful contrast

as that project was also committed to a

dened and ambitious timeline, though

the commitment came from federal dispo-

sition policies. The site of 1064 Mission

was owned by the U.S. Department of

Health and Human Services (HHS). The

property was transferred to the city for $1

on the condition that the new owner would

commit to a deed restriction that all uses

on the site be for the benet of people expe-

riencing homelessness and any improve-

ments be completed within three years of

the transfer agreement. If these terms were

not met HHS could take back the property

and improvements or impose large penalty

payments. This requirement drove much

of the development and resulted in a rela-

tively quick development timeframe.

A TERNER CENTER REPORT - FEBRUARY 2021

15

Unrestricted Capital Deployed

During Construction Brought

Substantial Flexibility and

Streamlining to the Development

Process

Tipping Point provided HAF with $50

million with the primary purpose of

supporting aordable housing develop-

ments to be completed faster and at lower

cost. The secondary purpose was to estab-

lish a revolving fund to support additional,

future deals. There were no other terms.

Tipping Point had no expectation of any

return on its investment and the funders

were comfortable with the risk that funds

would stay in the deals. HAF used these

funds to (i) buy the 833 Bryant property

(these funds were to be returned but will

now stay in the development) and (ii)

make a low-cost loan to Mercy Housing to

support the construction of 833 Bryant.

The interest and fees on the loan cover

HAF’s costs of administering the funds.

Critically, these funds were available early

in the development process, were able to

be put at risk, could be used for a very wide

range of uses, and came with little to no

regulatory baggage.

As noted above, in 833 Bryant, these dollars

are taken out with bonds and tax credits

during the construction and permanent

phases, and with debt service supported

by local subsidies post-construction. HAF

used Tipping Point’s Chronic Homeless-

ness Initiative funds to provide the project

with a $25 million loan to fund all expenses

until bond issuance, and a substantial

portion of expenses until conversion. Upon

origination of the bond-funded construc-

tion loan, approximately $8 million was

returned to HAF, and the remainder will

be returned with the entrance of most of

the tax credit equity at conversion.

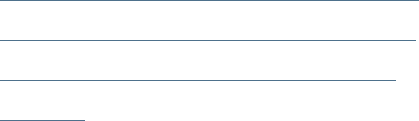

Figure 2: 833 Bryant Capital Stack

$-

$10

$20

$30

$40

$50

$60

$70

Pre-Bond Issuance Construction Phase Permanent Phase

Millions

Deferred Costs

Unrestricted Capital

(HAF Loan)

Recontributed

Developer Fee

Public Subsidy

(LIHTC)

Public Subsidy

(Bonds)

A TERNER CENTER REPORT - FEBRUARY 2021

16

Using these funds to cover extensive devel-

opment expenses before public subsidies

were deployed allowed 833 Bryant to

avoid many compliance review processes

that would have slowed development and

required revisions to the project design,

and also allowed the project to run devel-

opment processes in parallel. Receipt of

public subsidies, particularly local subsidy,

comes with many additional layers of

compliance review, each of which not

only takes time, but also carries the risk

of temporarily halting the development

process entirely.

833 Bryant avoids local subsidies entirely

until after the building is completed. It did

so because the regulations that accom-

pany local subsidy during construction

were deemed incompatible with achieving

the cost and timeline goals. For example,

developments receiving local subsidies

must meet the stipulations of Small Busi-

ness Enterprise (SBE) hiring. The require-

ments are intended to support the local

economy of the city and provide economic

opportunities for local residents. These

rules stipulate that contracts of $10,000 or

more are reviewed for the frequency with

which certied small rms are hired. This

introduces two mechanisms for delay and

increased costs. The rst is that the devel-

opment team is selected based on the lists

of SBEs provided by the city, as opposed

to the capacity of the rm and cost of

their services. Developers have reported

instances where SBEs became over-

whelmed by the demands of the project and

a second rm needed to be contracted to

provide identical services, increasing costs

and slowing development. Even the hiring

of high-capacity SBEs can slow develop-

ment, as services need to be advertised for

a minimum of 30 to 60 days before a rm

may be selected.

The design of the project is also aected

as MOHCD requires designs be reviewed

by the Oce of Disability, Historic

Preservation oce, and the Department

of Energy—to ensure that the project

conforms to green building and stormwater

standards—among other requirements.

The public subsidies that took out the

Tipping Point capital—CalHFA bonds

with associated LITHC—have many layers

of compliance review as well but did not

require any changes to the development

team or design of the project. Even bonds

issued by the city of San Francisco would

have come with a number of regulations

that would have forced changes in the

development team and project design.

Not only does each additional require-

ment come with a new risk of delay, but

the process of applying for public subsi-

dies also means that many parts of putting

projects together need to be put on hold

until subsidies have been awarded. Having

a pool of unrestricted capital allowed 833

Bryant, for example, to not have to wait for

its bond allocation before placing its order

for o-site units. This allowed the project

to begin construction even as it was nego-

tiating its lease with the city of San Fran-

cisco. 1064 Mission, on the other hand, was

tied to a development process that needed

to proceed one step at a time. Transfer

of the site from the federal government,

for example, required that the develop-

ment team show that the project was fully

funded and entitled. Furthermore, 1064

Mission was delayed by 45 days solely

due to documentation requests from the

federal government.

Freed from the additional design require-

ments that come with most housing subsi-

dies, 833 Bryant was designed with the

primary goal of providing quality, cost-e-

cient housing. A sizable portion of the total

A TERNER CENTER REPORT - FEBRUARY 2021

17

savings realized in 833 Bryant arise from

the design of the building, which includes

small units and ecient programming. For

example, the project has very little common

space and the units are stacked vertically

and there is no need for excess circulation

spaces. There is a single oor plan for all

units, allowing the o-site manufacturer

to program one large construction run,

maximizing their production eciency.

While there are non-apartment uses in the

building, including two small retail spaces

and oces for the supportive services

sta, these uses comprise a relatively small

portion of the total building area.

The design of 1064 Mission is far less cost-

ecient than it could have been because the

use of public subsidies required additional

processes that aected the project’s design.

In many regards 1064 Mission will be very

similar to 833 Bryant: it is permanent

supportive housing composed of 100

percent small studio units developed by

Mercy Housing with o-site construction

by Factory_OS. The project is much larger,

with 256 units, compared to 833 Bryant’s

145. In theory economies of scale might

be expected to result in a lower per-unit

total development cost for 1064 Mission.

However, excluding acquisition costs,

1064 Mission will cost about 25 percent

more. 1064 Mission will cost $509,826 per

unit, relative to $382,917 for 833 Bryant.

Much of this higher cost came from cost-

inecient design decisions that arose due

to design review. For example, the Planning

Department expected the project to have

an active use on the rst oor on Mission

Street. For this reason, the project includes

a large commercial kitchen which will

provide space for a culinary arts training

program for unhoused individuals as well

as building residents. The project also has

a large amount of community space. The

number of units in the project relative to

the size of the site is substantially lower

than 833 Bryant because of community

concerns over the total number of units

in the project. The developers estimate

that an additional 20 units could have

been easily accommodated in the site,

through a combination of making the units

smaller and reprogramming space from

community uses to residential uses. The

studio units in 1064 Mission are about 35

percent larger than the units in 833 Bryant,

measuring 350 square feet compared to

833 Bryant’s 260 square feet.

The design of Mission Bay Block 9 was

made even more cost-inecient than 1064

Mission in large part because of additional

layers of public review. Mission Bay Block 9

will be 140 units of permanent supportive

housing composed of 100 percent studios

developed by BRIDGE Housing and

Community Housing Partnership with

o-site construction by Factory_OS.

The units for this project, however, cost

33 percent more than 833 Bryant, at

$573,218 per unit. The high per-unit

costs were driven in large part because

this supportive housing project contains

relatively little housing. The lot for Mission

Bay Block 9 is about three times the size

of 833 Bryant, but the project will have

fewer units. The dearth of housing on the

site is largely due to design review that was

required because the Oce of Community

Investment and Infrastructure (OCII,

formerly the San Francisco Redevelopment

Authority) provided the land and subsidy.

OCII required that the program for the

site conform to plans passed in the 1990s,

which limited the number of aordable

units on the site. The developers had

initially programmed the site for nearly

twice as many units, with 120 senior units

and 130 units for adults, instead of the

140 total units that were constructed. The

initial design had a height that was in line

A TERNER CENTER REPORT - FEBRUARY 2021

18

with the municipal building across the

street and a traditional courtyard between

the two buildings. Additionally, the project

needed to be approved by the San Francisco

Board of Supervisors. During the public

hearing at the Board, residents voiced

their concern over the number of units in

the project, resulting in further reductions

in the number of units. As a result, over

one-quarter of the site is not housing at all,

but a landscaped community garden.

While unrestricted capital allows for a more

exible design and development process,

deploying capital before traditional public

subsidies requires mitigating the risks to

the capital that is spent. HAF established

a series of fallback plans to ensure that the

private capital put into the project could

be taken out with public subsidies from

bonds and the lease with the city. If the

project had not received a bond allocation,

for example, the team would have partially

replaced these funds with proceeds from

a 501(c)(3) bond issuance. Because these

bonds would not have associated tax credits

the project would still face a $15 million

gap that would have been lled with the

Tipping Point dollars. If the project did not

receive a bond allocation and the city was

unwilling to provide a lease, the program

of the building would shift to mixed-in-

come housing to the maximum rents

allowed under the Streamlined Ministe-

rial Approval Process, which would also

open up a gap to be lled with the Tipping

Point funds. Both of these fallback options

were fully analyzed and discussed with the

development team and funders. However,

the city of San Francisco was highly moti-

vated to support the deal. The development

of new permanent supportive housing for

unhoused individuals was a major priority

of the administration and providing these

units quickly and at relatively low cost

was also supported. Even so, the project

will be partially subsidized with Tipping

Point funds indenitely because the land,

purchased for $8 million, will eventually

be transferred to the city for $1.

Regulatory Streamlining through

the Streamlined Ministerial

Approval Process Removes

Development Risk and Speeds

Development Timeline

The Streamlined Ministerial Approval

Process, passed in 2017, provides a less-

onerous public approvals process on a

set timeline to certain aordable housing

projects in California cities that have been

under-producing housing. Specically, the

law ensures that the review of planning

applications for eligible projects does not

require conditional use permits, and thus

is entirely ministerial. This reduces the

burden to entitle projects and provides a

cap on the amount of time the local govern-

ment has to review and provide a decision

for eligible projects. The act also shields

eligible projects from challenges under

the California Environmental Quality Act

(CEQA), which has been used in the past

to hinder real estate development and has

likely contributed to the state’s housing

aordability crisis.

18

833 Bryant applied

for coverage under the Streamlined Minis-

terial Approval Process in January 2019

and received approval in May.

The swift entitlement process for 833

Bryant, made possible by the Streamlined

Ministerial Approval Process allowed the

project to benet from many cost e-

ciencies. The HAF acquired the site in

October 2018 and submitted its entitle-

ment application in December 2018, and

the project was fully entitled by April 2019.

The application for development, which

included detailed architectural drawings,

A TERNER CENTER REPORT - FEBRUARY 2021

19

was reviewed by the city to ensure compli-

ance with building and zoning codes. The

savings from the Streamlined Ministerial

Approval Process arise in part from the

law’s guarantee of a surety of the entitle-

ments process. Projects need to conform

to a set of rules that are known to the

developer and cannot be changed mid-way

through the development process and

the municipality must approve or deny

the project within 90 days. This allows

the development team to put together

an application that conforms to known

rules. This is not the typical process, and

developments often change their design

substantially based, for example, on citizen

concerns that are raised months or years

after the project rst applied. The dead-

line imposed on cities by the Streamlined

Ministerial Approval Process also ensures

that the back-and-forth between the city

and the developer over what is or is not to

code and granting of waivers and conces-

sions is resolved on a set timetable. The

speed at which 833 Bryant moved through

review cut the direct expenses that come

with more involved reviews (such as the

production of an Environmental Impact

Report), allowed the project to lock-in

construction costs early, and ensured that

the project’s design was established rela-

tively early in the development timeline.

In contrast to the speedy entitlement of

833 Bryant, Parcel O was developed before

the passage of the Streamlined Ministe-

rial Approval Process and suered cost

increases arising from a convoluted devel-

opment process and numerous changes to

the project design. Parcel O is a 108-unit

development in Hayes Valley, with 20

percent of units reserved for formerly

homeless residents. Most of the project

has larger units designed for families, so

while the project has fewer units than 833

Bryant, it is a larger building. Parcel O

required a conditional use permit, which

triggered a study of, among other things,

the shadows that the building would cast.

The study revealed that the building would

cast a small shadow on a nearby play-

ground for approximately one hour a day,

one month out of the year. The project was

redesigned to eliminate the shadow, but

the redesign resulted in the loss of four

units. The developer could have petitioned

against the loss of the units, but this would

have required producing a focused EIR,

as the shadow was considered to be an

impact important enough to be covered by

CEQA. The delay that the production of a

focused EIR would have caused the project

was decided to be more detrimental to the

project than the redesigned loss of four

units. The project was also delayed by six

months due to MOHCD’s request that the

developer delay their application to Cali-

fornia’s Tax Credit Allocation Committee

(TCAC) until MOHCD could review bids

for the project, and the requirement that

the Board of Supervisors approve funding

for the project. The earliest the project

could go to the Board for approval was

August, but the Board of Supervisors is

on recess in August. The collective impact

of these delays increased costs by at least

$500,000. An additional $500,000 in

costs were added because the Mayor’s

Oce of Disability, having misclassied a

portion of the building during plan review,

determined after the project was completed

that a portion of the building was a means

of egress that needed to be accessible per

ADA requirements. This required demol-

ishing a portion of the newly constructed

building and re-building it to a dierent

design. The project also relied on cap-and-

trade dollars, which required a fully enti-

tled project to include an archaeological

review. This review added $300,000 in

direct costs to the project.

A TERNER CENTER REPORT - FEBRUARY 2021

20

O-Site Construction Allows

Development Processes to Run in

Parallel

The units for 833 Bryant were constructed

o-site at Factory_OS, a union-staed

facility located on a decommissioned naval

base in Vallejo, CA. Research suggests that

o-site construction has the potential to

provide meaningful cost and time savings

over traditional stick-built construction.

19

For 833 Bryant, the greatest eciencies

from o-site construction were realized

in conjunction with the quick entitlements

process made possible by using exible

capital before deploying public subsidies

and from the development process under

the Streamlined Ministerial Approval

Process. 833 Bryant was able to lock-in the

design of the project relatively early, which

took advantage of the cost eciencies

made possible with modular construction.

Modular construction can achieve greater

cost eciencies by allowing the construc-

tion of the building simultaneously with

or in advance of site work. The relatively

swift nalization of design and comple-

tion of entitlements allowed the developer

to direct Factory_OS to begin producing

units in January 2020, though bonds for

the project were not issued until August.

Thus, the package of cost eciencies for

833 Bryant allowed the project to avoid 7

months of construction cost ination and

interest carry. The contract for the units

was approximately $9.5 million, which,

assuming 8 percent annual hard cost

ination and the bond rate of 2.82 percent

would be $440,000 in avoided cost ina-

tion and $160,000 in interest payments for

a total savings of about $600,000.

Casa de la Misión provides a useful compar-

ison to 833 Bryant, as Casa de la Misión

also received the Streamlined Ministerial

Approval Process designation and was

funded without construction subsidies

from the city. But Casa de la Misión diers

in that it was constructed entirely on-site.

Casa de la Misión is substantially smaller

than 833 Bryant, with 45 studio units and

approximately 1,100 square feet of street-

level commercial space. The studios are

only slightly larger than 833 Bryant’s at

about 300 square feet, relative to Bryant’s

260. Excluding acquisition costs Casa de la

Misión will cost approximately 50 percent

more on a per-unit basis, or $612,000 per

unit, relative to approximately $382,917

for Bryant. Most of these cost dierences

are driven by the ecient design of 833

Bryant, though 833 Bryant is also slightly

less costly on a gross square foot basis

(about 3 percent less costly). The gross

square foot cost savings are somewhat

attenuated by the smaller units of 833

Bryant, which would be expected to result

in higher savings per square foot, all else

being equal.

The direct cost and time savings that come

from o-site construction at 833 Bryant are

real, but the o-site construction industry

is not fully established, which adds risks

and blunts the even greater savings that

o-site construction could potentially

achieve. This construction method is still

not standard, which requires assembling a

development team (particularly architects

and contractors) that have prior experi-

ence with o-site construction. O-site

construction allows for economies of scale

that exceed stick-built construction, but

these benets are most fully realized with

large orders of single unit types. If each

production run is limited to units that are

custom-designed for a specic project,

savings from economies of scale will be

limited. Production runs of units that are

used in multiple projects could unlock

further savings but requires coordination

A TERNER CENTER REPORT - FEBRUARY 2021

21

across projects that is rarely seen today.

Construction timeline savings from o-site

mostly arise from the ability to construct

units at the same time as site work is being

completed. This requires that the design of

the project be nalized early, which can be

dicult in a lengthy entitlement process

when the design may be required to change

unexpectedly, and that the unit construc-

tion costs be funded early, which can be a

challenge with existing subsidy programs.

Conclusion

Though not yet complete, 833 Bryant is on

track to provide substantial cost and time-

line savings relative to similar projects in

San Francisco. These savings are made

possible through a package of cost ecien-

cies that allow the project to follow a devel-

opment process that is more exible and

lower risk in some ways (although comes

with risk for the unrestricted capital) and

allows the development to be oriented

around the production of quality units at

relatively low cost to a much greater extent

than is typical. The development provides

lessons for the future development of

aordable housing, particularly perma-

nent supportive housing, in a few ways.

First, it provides a model for development,

mostly by showing the potential of unre-

stricted capital. 1064 Mission and Mission

Bay Block 9 are two of many projects that

use the Streamlined Ministerial Approval

Process and o-site construction, but 833

Bryant shows that the savings that these

two measures can achieve can be substan-

tially magnied with the kind of funding

that Tipping Point provided. The source

of funding is far less important than its

terms. In the case of 833 Bryant, the unre-

stricted funding substantially changed the

development process because the funds (i)

were fully available early in the develop-

ment process, (ii) could be put up at risk,

(iii) could be applied to a very wide range

of uses, and (iv) came with little to no regu-

latory requirements.

Much of the risk, however, was not that the

funds would be “wasted,” but instead that

they would remain in the deal, much as

traditional subsidy does. For example, the

acquisition of 833 Bryant was funded with

Tipping Point capital that was initially

expected to be returned to HAF through

lease payments from the city. However, the

budget crunch caused by the COVID-19

pandemic resulted in cuts to these planned

payments. Now these funds will stay

with the deal indenitely, much as tradi-

tional subsidy would, instead of being

revolved into other development proj-

ects. Creative structuring of unrestricted

capital, however, can help ameliorate these

risks. HAF structured their support to 833

Bryant primarily as loans priced to cover

HAF’s costs. If preservation of capital was

a higher priority, other structures, such as

overcollateralization, could be used to deal

with the risks of loss of capital over time.

833 Bryant also provides insight into the

impacts of policies and funding programs

that pose hindrances to the timely and

cost-eective development of aord-

able housing, particularly permanent

supportive housing. For example, much

of the savings that 833 Bryant achieved

came from bypassing the required devel-

opment processes to entitle and fund

aordable housing. Stakeholders inter-

viewed for this project were, for the most

part, supportive of the larger goals of these

additional process requirements, such as

the preservation of archaeological assets,

community engagement, and creating a

lively streetscape. The onerousness and

risk to the housing project, however, was

deemed disproportionate to the benet

A TERNER CENTER REPORT - FEBRUARY 2021

22

coming from advancing these goals. A

shadow occasionally cast on a playground

is a negative impact, but hardly seems

proportionate to the loss of four aordable

homes.

Similarly, the design processes typical for

aordable housing in the city often favor

a mix of uses, such as the inclusion of the

clinic and culinary training center in 1064

Mission and the large community garden

in Mission Bay Block 9. A mix of uses at

the project level, particularly when they

support the local residents, including the

tenants, can be a substantial benet. But

additional uses increase the cost of the

project and the timeline for the devel-

opment. These non-apartment uses also

frequently use the same sources of subsidy

as residential uses. For example, every

source of subsidy for 1064 Mission can be

applied to residential uses. The additional

costs and time associated with the devel-

opment of non-residential uses in PSH

projects should be weighed against the

fewer units produced with each project and

units being built later. San Francisco is by

no means unique in this regard, and most

cities that have a substantial number of

people experiencing chronic homelessness

could likely provide more homes if they

re-balanced the goal of having mixed-use

developments with the goal of housing the

unhoused.

The Streamlined Ministerial Approval

Process provides a model for speeding the

development process for aordable housing

in specic situations. A similar approach

might benet the development of PSH in

San Francisco, given the dire need. Design

and process requirements that come with

development and funding sources could

be streamlined for the development of

PSH projects. The Streamlined Ministerial

Approval Process itself could be improved,

as the application for approval under the

law requires a site permit application,

which in jurisdictions like San Francisco,

is a very substantial package. Lessening

the design review requirements by liber-

alizing waivers and concessions could also

be considered.

Finally, the case of 833 Bryant highlights

the eciency gains that are possible when

aordable development stakeholders, in

both the private and public sectors, are

focused primarily on providing decent-

quality housing as quickly as they can for

as many families as they can. The stake-

holders for 833 Bryant shared this goal

and were able to work together to achieve

substantial cost and time savings. It is not

common for the stakeholders of aord-

able developments to commit to dened

time and cost goals and there are powerful

incentives to add design elements that

increase costs and extend the develop-

ment timeline. Incorporating dened and

meaningful cost and time goals into the

process of developing aordable housing,

either through subsidy programs or

through other means, could be a means of

bringing cost discipline to housing produc-

tion and making the best use of scarce

subsidy dollars. Across the country the

lack of aordable housing remains a far

more pressing problem than the quality

of aordable housing that is built. A focus

on producing quality housing speedily and

controlling costs will result in more fami-

lies being stably housed with the limited

subsidies available.

ENDNOTES

1. Watson, N. E., et al. (2020). “Worst Case Housing Needs:

2019 Report To Congress.” Worst Case Housing Needs. Retrieved

from:https://www.huduser.gov/portal/publications/worst-case-

housing-needs-2020.html.

2. CBPP. (2019).“Federal Rental Assistance Fact Sheets.” Center on

Budget and Policy Priorities. Retrieved from:https://www.cbpp.org/

research/housing/federal-rental-assistance-fact-sheets.

3. U.S. HUD. (2020). “CoC Homeless Populations and Subpopu-

lations Reports.” Retrieved from:https://www.hudexchange.info/

programs/coc/coc-homeless-populations-and-subpopulations-re-

ports/?lter_Year=<er_Scope=NatlTerrDC<er_State=<er_

CoC=&program=CoC&group=PopSub.

4. GAO. (2018).“Low-Income Housing Tax Credit: Improved Data

and Oversight Would Strengthen Cost Assessment and Fraud Risk

Management.” U.S. Government Accountability Oce. Retrieved

from: https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-18-637.

5. Applied Survey Research. (2020). “San Francisco Homeless

Count & Survey Comprehensive Report 2019.” San Francisco Home-

less Point-in-Time Count & Survey.

6. Leifheit, K., et al. (2020). “Expiring Eviction Moratoriums and

COVID-19 Incidence and Mortality.” SSRN Scholarly Paper,Social

Science Research Network. Retrieved from:https://doi.org/10.2139/

ssrn.3739576.

7. Woodhall-Melnik, J. & Dunn, J. (2016). “A Systematic Review of

Outcomes Associated with Participation in Housing First Programs,”

Housing Studies 31, no. 3: 287–304, https://doi.org/10.1080/026

73037.2015.1080816; Bamberger, J. & Dobbins, S. (2014). “Long-

Term Cost Eectiveness of Placing Homeless Seniors in Permanent

Supportive Housing.” Community Development Investment Center

Working Paper (San Francisco, CA: Center for Community Develop-

ment Investments, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco). Retrieved

from:https://www.frbsf.org/community-development/publications/

working-papers/2014/july/long-term-cost-effectiveness-home-

less-seniors-permanent-supportive-housing/.

8. San Francisco Planning. (2020).“San Francisco’s Community

Stabilization | Homelessness Prevention and Supportive Housing.”

Retrieved from:https://projects.sfplanning.org/community-stabiliza-

tion/homelessness-prevention-and-supportive-housing.htm.

9. Goggin, B. (2018). “Measuring the Housing Permitting Process

in San Francisco.” Terner Center for Housing Innovation (Blog).

Retrieved from:https://ternercenter.berkeley.edu/blog/measuring-

the-housing-permitting-process-in-san-francisco; Reid, C. (2020).

“The Costs of Aordable Housing Production: Insights from Califor-

nia’s 9 Percent Low-Income Housing Tax Credit Program.” Terner

Center for Housing Innovation. Retrieved from: https://ternercenter.

berkeley.edu/research-and-policy/development-costs-lihtc-9-per-

cent-california/.

10. Additionally, $5,405,858 of developer fee is recontributed to

the project for a total development cost of $60.4 million, exclusive of

acquisition costs.

11. Applied Survey Research. (2019). “San Francisco Homeless

Count & Survey Comprehensive Report 2019.”

12. The units in 833 Bryant are 260 square feet, which is above the

220 square foot minimum for new construction in San Francisco and

much larger than units in single-room occupancy (SRO) develop-

ments. As of 2011 a limited number of units of 150 to 220 can be built.

However, units of less than 300 square feet size are rarely built as new

aordable housing in the city.

13. This package of cost eciencies are not the only innovations

at play at 833 Bryant. HAF’s acquisition of the site, for example,

represents a dierent approach to nding sites for aordable housing

than are typically used in San Francisco. However, this brief focuses

on cost and timeline savings, which the project intended to achieve

largely though this package of four approaches.

14. Reid, C. & Raetz, H. (2018). “Practitioners Weigh in on Drivers of

Rising Housing Construction Costs in San Francisco.” Terner Center

for Housing Innovation. Retrieved from: http://ternercenter.berkeley.

edu/uploads/San_Francisco_Construction_Cost_Brief_-_Terner_

Center_January_2018.pdf.

15. Brian Goggin, “Measuring the Housing Permitting Process in San

Francisco,” Terner Center Blog (blog), July 24, 2018, https://terner-

center.berkeley.edu/blog/measuring-the-housing-permitting-pro-

cess-in-san-francisco.

16. Reid, C. (2020). “The Costs of Aordable Housing Production:

Insights from California’s 9 Percent Low-Income Housing Tax Credit

Program.” Terner Center for Housing Innovation. Retrieved from:

https://ternercenter.berkeley.edu/research-and-policy/develop-

ment-costs-lihtc-9-percent-california/.

17. Raetz, H. et al. (2020). “The Hard Costs of Construction: Recent

Trends in Labor and Materials Costs for Apartment Buildings in

California.” Terner Center for Housing Innovation. Retrieved from:

https://ternercenter.berkeley.edu/hard-construction-costs-apart-

ments-california.

18. Barbour, E. & Teitz, M. (2005). “CEQA Reform: Issues and

Options.” Public Policy Institute of California. Retrieved from: http://

www.ppic.org/publication/ceqa-reform-issues-and-options/.

19. Reid, C. (2020). “The Costs of Aordable Housing Production:

Insights from California’s 9 Percent Low-Income Housing Tax Credit

Program.” Terner Center for Housing Innovation. Retrieved from:

https://ternercenter.berkeley.edu/research-and-policy/develop-

ment-costs-lihtc-9-percent-california/.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to extend our thanks to Tipping Point Community who

provided nancial support for this project. We would like to thank

the San Francisco Housing Accelerator Fund and Mercy Housing for

providing data and thoughtful feedback.