Home Truths:

Implications of Short-

Term Vacation Rentals

on Victoria’s Housing

Market

An Independent Citizen’s White Paper by Victoria Adams

Victoria, B.C.

1/13/2017

Home Truths: Implications of Short-Term Vacation Rentals on Victoria’s Housing Market

2

Table of Contents

Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................................... 4

Chapter 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 6

1.1 Overview .......................................................................................................................................... 6

1.2 Victoria explores options to regulate short-term vacation rentals ................................................. 8

Chapter 2. Situational Analysis .................................................................................................................. 9

2.1 The shifting housing landscape ....................................................................................................... 9

2.2 Victoria’s rental housing market context ...................................................................................... 11

2.3 Beyond the bravado, buildings and beautiful gardens ................................................................. 12

2.4 Airbnb and the “sharing” economy .............................................................................................. 14

Chapter 3. Victoria’s Short-Term Vacation Rental Market and Long-Term Rental Housing Market ..... 16

3.1 Salient features of the short-term vacation rental market in Victoria .......................................... 16

3.2 Victoria’s long-term rental housing market .................................................................................. 25

3.2.1 Population and housing tenure ........................................................................................ 25

3.2.2 Composition and location of the housing stock ............................................................... 29

3.2.3 Vacancy rates, rents, and demand for rental housing ...................................................... 33

3.2.4 The impact of Airbnb units on the secondary rental housing market .............................. 35

3.2.5 Household incomes of renters and owners ...................................................................... 37

3.2.6 Residential building costs and home prices ...................................................................... 38

3.2.7 Housing market changes and the impact of gentrification in James Bay ......................... 39

Chapter 4. Implications of the Expanding Short-Term Vacation Rental Sector

on Victoria’s Tourist Accommodation Market .......................................................................................... 43

4.1 A snapshot of short-term vacation rentals, long-term rentals,

and tourist accommodation in James Bay ..................................................................................... 45

4.2 What’s missing from this picture? ................................................................................................ 49

Home Truths: Implications of Short-Term Vacation Rentals on Victoria’s Housing Market

3

Chapter 5. Conclusions & Housing Policy Implications ........................................................................... 51

5.1 The social effects of increased tourism and the home-sharing economy on Victoria .................. 53

5.2 Grappling with the consequences of short-term vacation rentals ................................................ 54

5.3 Balancing the conflicting interests of home-owners, renters, and hoteliers ................................ 56

5.4 Recommendations and reflections ................................................................................................ 58

Home Truths: Implications of Short-Term Vacation Rentals on Victoria’s Housing Market

4

Executive Summary

Canadian author Yann Martel has characterized his homeland as “the greatest hotel on earth: it

welcomes people from everywhere”.

This is an apt description of why owners of this second-largest piece of real estate in the world are eager

to capitalize on every underutilized room, empty condo suite, or temporarily vacant home they can.

The question is: What happens to a community or indeed an entire country that sees itself as a

convenient impermanent waystation or a speculative real estate opportunity with no lasting

responsibilities attached?

If you’re Mark Zuckerberg, the immensely wealthy founder of Facebook’s 1.7 billion world-wide fan

club, you have the answer: “find a way to change the game so it works for everyone.”And the name of

the game in the 21

st

century is maximizing profit just as it has been for hundreds of years. The name of

the game may have changed, based new business models and technologies, but the game always

promises to deliver perks and premiums for all those willing to pay the price. Let no one forget however,

that like all games, there are winners and losers.

In the last decade, there has been an explosive growth in a new game - the online “home-sharing”

market that connects people seeking short-term lodging with those who wish to rent their property to

leisure or business travelers. These platforms charge a fee for hosting residential listings, managing

bookings and payment, and providing additional services such as insurance. Airbnb, the largest of these

home-sharing platforms, established in 2008, is now a company valued at more than $40 billion, with

more than three million listings worldwide and hosts in 190 countries and 34,000 cities.

In 2015, Airbnb hosts with more than 50,000 listings in Canada, provided accommodation to more than

327,000 guests from across the country and elsewhere. Some 935,000 travelling Canadians also stayed

with Airbnb hosts located in the country and beyond its borders. Airbnb says 85 percent of its global

hosts rent out their primary residences in large cities five or six times a month as a modest way to

supplement their income.

This “disruptive” peer-to-peer technology has changed the travel and accommodation landscape

significantly, increasing competition for large-scale commercial hotel operators and smaller

independently owned bed-and-breakfasts. It has also had a significant impact on the traditional rental

housing market in major urban areas which provide permanent accommodation for workers, families,

and retirees.

What these “home-sharing” ventures often overlook is the potential negative impact on permanent

accommodation availability in cities with affordable rental housing crises. In particular, what goes

unmentioned is the fact that the most significant source of home-sharing revenue for Airbnb, VRBO and

other tourist accommodation platforms comes from absentee multiple listing landlords and real estate

speculators who operate entire units or buildings as unlicensed, unregulated, and untaxed commercial

hotels.

Home Truths: Implications of Short-Term Vacation Rentals on Victoria’s Housing Market

5

The new ‘collaborative consumer’ model espoused by Airbnb and others is based on leveraging the

existing housing market while generating income and retaining profits outside the formal regulatory and

taxation environment. This novel form of enterprise poses a challenge for local governments: (1) how to

address the severe shortage of shelter together with soaring prices of housing and rents in urban areas

and, (2) how to handle effectively and equitably the complex issue of regulating and taxing this new

transnational home-sharing enterprise.

A 2015 study by Chris Gibbs

1

of Ryerson University’s Ted Rogers School of Management and the

hospitality consulting group, HLT Advisory, showed the growth of Airbnb across Canada and its negative

impact on hoteliers particularly in four major cities: Toronto, Ottawa, Calgary and Vancouver. The

author concluded his findings with the recommendation that municipalities carefully consider regulatory

and licensing issues relating to the operation of Airbnb and other similar platforms.

This independent white paper explores the issue of home-sharing, in particular, the potential impact of

Airbnb on the rental housing market British Columbia’s capital city, Victoria. It draws on the timely

research of Karen Sawatzky, a former Victoria resident who has just completed her S.F.U. Master of

Urban Studies thesis, “Short-Term Consequences: Investigating the Nature, Extent and Rental Housing

Implications of Airbnb Listings in Vancouver.” Her thesis also considers the important research findings

of the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives on the impact of Airbnb in Toronto.

2

While this paper does not purport to be authoritative academic study, it nevertheless contemplates,

from a thoughtful citizen’s perspective, the overall changes that are taking place in the urban landscape

with a view to assessing the impact of home-sharing in a popular tourist destination. Today, the City of

Victoria has 955 active Airbnb listings, or one short-term vacation rental listing for every 87 inhabitants,

while the neighbourhood of James Bay has one Airbnb listing for every 60 residents

3

. In addition to

Victoria’s experience with the new lodging model, the author also considers the experience of local

governments expressed by members of the Union of B.C. Municipalities and Tourism Victoria. These

stakeholders try to balance the needs of permanent residents needing affordable, accessible places to

live, while recognizing the need to cater to tourists looking for accommodation be it in hotels and

motels, guest houses and bed-and-breakfasts as well as granny suites and condo units.

This paper provides no definitive answers. It does however create a foundation for citizens, urban

professionals, and decision-makers to discuss issues of home-sharing, the costs and benefits of short-

term rentals to individuals and to the community, and shed light on policy guidelines that may help

develop an appropriate regulatory framework to solve issues related to licensing, compliance, and

enforcement of a burgeoning new sector of the 21

st

century economy.

1

Dr. Chris Gibbs, “Airbnb…& The Impact on the Canadian Hotel Industry”, Ted Rogers School of Hospitality and

Tourism Management, (PowerPoint Presentation), June 2016.

http://www.ryerson.ca/content/dam/tedrogersschool/htm/documents/ResearchInstitute/CDN_Airbnb_Market_R

eport.pdf

2

Zohra Jamasi, Trish Hennessy, Nobody’s Business: Airbnb in Toronto, (Toronto: Canadian Centre for Policy

Alternatives), September 2016.

3

Data based on third-party analytics firm, Airdna (December 1, 2016) and Airbnb (December 31, 2016).

Home Truths: Implications of Short-Term Vacation Rentals on Victoria’s Housing Market

6

Chapter 1. Introduction

1.1 Overview

The City of Victoria is experiencing a significant redevelopment of its existing housing stock, involving

demolition of older single family homes and low-rise wood-frame apartment blocks, particularly in the

downtown core and in the adjacent neighbourhoods of James Bay and Fairfield.

Victoria is now ranked the second least affordable place to live in Canada. The 2016 Demographia

International Housing Affordability Survey indicates that a home in B.C.’s capital city now has a price tag

that is more than 6.9 times the median household income of the area. In their view, a home in this City

is “seriously unaffordable” to many buyers and is certainly well beyond the financial means of most

renters.

While Victoria may have been named by Conde Nast Traveler as the seventh best city to visit in the

world, tourism being its second largest industry, there remains an unanswered question: Can the City’s

infrastructure be sustained by hospitality alone? Must the City’s permanent residents and their quality

of life be sacrificed in order to attract the lucrative domestic and off-shore transient tourist trade?

According to Victoria.Citified.ca

4

, the real estate buying frenzy which has seen a soaring market over the

past two years is far from over. One of the top five-busiest months in the city’s real estate history,

reveals that pre-sale prices for new construction and resale homes are hitting new highs as inventory

falls. In other words, the demand for accommodation is outstripping supply in a tight housing market.

The median price for a single-family home in what Mayor Helps calls a “21

st

century world leading city”

5

is now $650,000. As for condos, the benchmark price is $371,300 up 22 percent over November 2015.

With a modest increase in the number of condos 171 versus 159 sold over this time last year, and a

consistently low inventory, it takes on average only 33 days to sell a condo unit now (compared to 62

days in November last year), according to The Condo Group

6

.

Victoria is now the recipient of affluent newcomers: Vancouverites cashing out on homes and buying

condos here, and Prairie retirees seeking a comfortable climate and cozy condos. The city attracts well-

paid civil servants and an increasing segment of high-tech millennials who like to bike or walk to work.

Added to the mix is a small but growing cohort of overseas investors who are seeking a safe place to

park their funds while their children pursue an education in the city.

4

Mike Kozakowski, “One year in, Victoria’s real-estate buying frenzy far from over”, Ctified.ca, November 2, 2016.

http://victoria.citified.ca/news/one-year-in-victorias-real-estate-buying-frenzy-far-from-over/

5

Lisa Helps, “A look back at 2016 with Victoria Mayor Lisa helps”, Victoria News, December 30, 2016, p. A5.

http://www.vicnews.com/news/408809005.html

6

The Condo Group.com, Victoria Real Estate: VREB Releases its November Numbers, December 2, 2016.

Home Truths: Implications of Short-Term Vacation Rentals on Victoria’s Housing Market

7

In this growing capital region economy, we are witnessing increasing income disparities and uneven

distribution of wealth both of which are having a significant impact on the quality of life of residents.

And, as a popular island tourist destination, we are seeing profound impacts on this port city from

millions of tourists flowing through it, in addition to the growing in-migration of financially secure

retirees from the Lower Mainland and elsewhere across the country. Some of the most significant

impacts are felt by tenants who represent 60 per cent of the city’s households. In a tight rental housing

market with a vacancy rate of 0.5 per cent, one can expect to pay an average of a $1,000 a month for a

one-bedroom apartment in Victoria.

7

It is in this context we see the impacts of economic change playing out in the City of Victoria, particularly

in the competitive housing market. There is a growing trend toward infill densification, demolition of

older homes and low-rise apartments, and replacement with multi-storey condo developments in the

downtown area and surrounding neighbourhoods. In this urban environment, there is an increasing

displacement of tenants as property owners convert their units to cater to the rapidly growing and

highly profitable short-term vacation rental (STVR) market rather than the long-term renters (LTRs).

With more than 1,700 rental condos in the downtown area, many condo owners see a business

investment opportunity in renting out entire suites at premium prices to capitalize on the tourist

demand for non-hotel lodgings.

Not surprisingly, the growth of the short-term vacation rental market now referred to as the “alternative

accommodation” market is also having an impact on the existing hotel industry, half of which is located

in the City of Victoria. The general manager of the Inn at Laurel Point in James Bay says that competition

from Airbnb and other short-term rental services, which has grown to 1,000

8

or more units, is now a

threat to the hotel industry in Victoria

9

. To put this in perspective, this new accommodation niche now

represents the equivalent of one-third of the hotel room capacity for the City. (The Downtown and Inner

Harbour is home to 30 hotels with 3,186 rooms.)

The same hotelier pointed out that the STVRs have a distinct advantage over hotels. The Airbnb and

other similar home-sharing units don’t pay the City’s 3 per cent marketing tax on accommodation, the

Province’s 8 per cent room tax, Provincial and Federal Sales Tax or Income Tax. In addition to taking a

bite out of hotel industry revenues, he added that STVRs are now posing an additional concern,

increased pressure on employee housing. Apparently his new assistant manager who recently moved to

Victoria was unable to move into an apartment when the landlord decided instead to list it in on Airbnb.

7

Canada Mortgage and Housing Rental Market Report Victoria CMA, Fall 2016, p.8.

8

Insideairbnb.com http://insideairbnb.com/victoria/ on August 1, 2016 reported 1,691 listings for the Greater

Victoria area while Airdna LLC (US) https://www.airdna.co/city/ca/victoria on December 1, 2016 reported 937

Airbnb active listings for the City of Victoria.

9

Deborah Wilson, “Victoria hotelier calls for fair taxation of Airbnb rentals”, CBC, November 29, 2016.

http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/victoria-airbnb-hotels-taxes-1.3871973?cmp=rss

Home Truths: Implications of Short-Term Vacation Rentals on Victoria’s Housing Market

8

Housing for hotel and resort industry employees is also a significant issue in the tourist town of Tofino,

B.C. which has recently taken steps to regulate Airbnb rentals.

1.2 Victoria explores options to regulate short-term vacation rentals

It is in this context that Victoria City Council received an October 27, 2016 report from staff on Short-

Term Vacation Rentals

10

assessing the impact of short-term vacation rentals on the rental housing pool

with options to regulate Airbnb and other similar short-term vacation rental platforms.

This report included a brief opinion on “Short-Term Vacation Rentals Policy” given by a Vancouver-based

urban planning consultant to the City, several personal testimonials relating the benefits of short-term

rentals to property owners. It is interesting to note that Airbnb has established more than 100 clubs for

hosts and guests globally, with the hope that these active home-sharing “community members” will

become a political force to shape local regulation in its favor.

In addition, the report also narrowed the discussion to four possible options for regulating short-term

vacation rentals and summarized their advantages and disadvantages.

1) Prohibit STVRs throughout the city. (This option was not recommended, without referencing the

experience of several tourist destinations

11

in Florida). Staff’s primary objection is based on the premise

that this option “removes property owners’ existing development entitlements”. There is no

consideration of whether the existence of what some see as ‘pseudo hotels’ in residential

neighborhoods, could lead to disillusionment with local government who may be perceived as

ineffective in protecting the interests of local tax-paying citizens including renters. Note: The City of

Richmond, BC voted on January 10, 2017 to ban short-term rentals, according to The Globe & Mail.

2) Continue to permit STVRs but with limitations.

3) Maintain current development rights in zoning, communicate licensing requirements for data

collection, and prohibit STVRs in affordable housing projects funded by the City.

4) Permit STVRs throughout the city.

Staff recommended option 3 as the best policy option, with a view to continuing to monitor the

situation and discuss it further at a workshop for Council in January 2017.

10

Jonathan Tinney, Director, Sustainable Planning & Community Development, City of Victoria, “Short-

Term Vacation Rentals”. Report to City Council, October 7, 2016.

https://victoria.civicweb.net/FileStorage/D755644EC04447E0876D7DB7C2D22B84-

report%20short%20term%20vacation.PDF

11

Chabeli Herrera, “How $20,000 fines have made Miami Beach an Airbnb battleground”, Miami Herald,

November 27, 2016, http://www.miamiherald.com/news/business/biz-monday/article117332773.html

and Gwen Filosa, “Key West cracking down on vacation rentals”, Miami Herald, May 19, 2016.

http://www.miamiherald.com/news/business/biz-monday/article117332773.html

Home Truths: Implications of Short-Term Vacation Rentals on Victoria’s Housing Market

9

Chapter 2. Situational Analysis

2.1 The shifting housing landscape

The United Nations recognizes housing as a fundamental human right; however, there is no guarantee

of the right to shelter for everyone in Canada. What can be said is that governments at all levels are

committed to improving the quality of life for residents by increasing jobs, the tax base, purchasing

power, diversity as well as availability of goods and services, amenities and infrastructure to serve the

needs of the community. At the foundation of this economic development rationale is the notion that

the ownership of private property will spearhead and sustain the growth of communities together with

the health and well-being of people.

In fact, this “home-ownership” ethos is one of the primary guiding principles to ensure the economic

vitality of British Columbia according to the real estate industry:

“Realtors believe home ownership is the dream of most British Columbians and

deserves a preferred place in our system of values. Home ownership contributes

to community responsibility; civic, economic, business and employment stability;

family security and wellbeing.”

12

It also appears that this thesis of the real estate industry is the rationale behind the City of Victoria’s

housing strategy, particularly with regard to options for regulating short-term vacation rental properties.

The staff report

13

indicates the preferable option is one that “maintains existing property owners’ rights

in the downtown core where transient accommodation use is permitted” and avoids “removing

property owners existing development entitlements.”

The 2011 National Household Survey (NHS) indicates that housing for 87 per cent of Canadians is

provided through the private market, with than two thirds of households owning their own homes while

31 percent rent. In the province of B.C., 70 percent of households own homes while 30 percent rent.

What is significantly different in the City of Victoria, is that 60 per cent of households (24,820) rent

compared to 40 percent who own their own homes.

Home-ownership in Canada has been consistently subsidized by all levels of government through the tax

system including home-owner grants for improvements such as energy conservation, disability

alterations, etc. From a housing perspective, the introduction of a capital gains tax (with the exception

of a principle residence) and the elimination of investment real estate as a tax shelter for other income

(that resulted in the boom in the construction of apartment buildings prior to 1972) were said to have a

12

The Victoria Real Estate Board http://www.vreb.org/about-vreb/quality-of-life, p. 4.

13

Tinney, City of Victoria Short-Term Vacation Rentals Report, p. 6.

Home Truths: Implications of Short-Term Vacation Rentals on Victoria’s Housing Market

10

profound effect on the housing landscape across the country.

14

Removing the incentives to build rental

accommodation encouraged a market shift towards home ownership in the 1970s, particularly with the

rise in popularity of the fragmented home-ownership model, known as strata title properties or

“condominium” units.

During the early 1980s, with a downturn in the economy, the federal government offered interest free

loans to developers in order to increase jobs in the construction industry and subsidize a small portion

of units for low-income and special needs tenants. Increasingly however, the responsibility for housing

has been devolved from the federal and provincial governments to local governments. This shift in the

allocation of increasingly limited tax dollars onto municipal authorities is now placing ever greater

pressures on taxpayers who must also carry the growing and costly infrastructure upgrades for roads,

bridges, and ports, as well as utility, water, and sewage systems.

The housing market in this country has consistently favored home-owners. Canadian housing policy

researcher, David Hulchanski, points out that Canada’s housing system is comprised of a primary and

secondary group, each with its own distinct and unequal range of government activities and subsidies.

The primary part of the housing system represents the majority of Canadian households including most

home-owners and those tenants who live in the higher end of the market. The secondary housing part

consists of tenants in the lower portion of the rental market and lower-income home-owners in rural

areas.

This dual housing policy recognized by all three levels of government assists home-owners and neglects

tenants. Hulchanski suggests that because Canada has never had a policy of tenure neutrality, i.e.

providing assistance to home-owners and tenants equally, the consequence is that the housing policy

has subsidized home-ownership for the past 45 years.

15

Today’s home-owners in the country, on average have twice the income of tenant households. So, it is

not surprising that housing developers and the municipal authorities, who regulate them, are

committed to supporting the flow of benefits and amenities to wealthier homeowners. These may

include re-writing bylaws such as those in the City of Victoria to encourage urban agriculture revenue-

generating opportunities for property-owners, rain-water rewards to reduce stormwater user fees for

home-owners, segregated off-leash dog walking parks for canine owners who live in private homes as

well as the provision of property tax deferrals for senior home-owners. Few if any of these benefits are

available to tenant households in the City of Victoria, 25 percent of who currently spend more than 50

percent of their before-tax household income on rent plus utilities

16

.

What is apparent in this cursory examination of the rental housing market is the dearth of information

available on the status of renters, particularly their current needs and gaps in services. While Canada

Mortgage and Housing (CMHC) collects rental housing data, it does so in a limited fashion, focusing on

14

The Rental Housing Index, Examining the Rental Housing Market in British Columbia, Hannah M. McDonald, UBC

MSc. Planning Thesis, U.B.C., 2015, p. 5.

15

Ibid., p. 13.

16

Ibid., p. 23

Home Truths: Implications of Short-Term Vacation Rentals on Victoria’s Housing Market

11

larger purpose-built rental structures and the break-down of units by key neighbourhoods. However,

CMHC fails to identify smaller purpose-built rentals: apartments (with fewer than 3 units), rented

single-family dwellings/duplexes/triplexes, rented condos, and secondary suites and accessory garden

suites by neighbourhood or by age of structure. As a consequence, the private sector rental housing

market profile remains incomplete at best, ignoring for the most part smaller non-corporate landlord

properties. These house seasonal tenants, particularly students, 80 percent of whom cannot find

accommodation on campus at the University of Victoria.

2.2 Victoria’s rental housing market context

The months-long presence and plight of homeless people living in tents on the grass outside the B.C.

Law Courts in downtown Victoria in 2016, covered by the local and national media, drew attention in a

profound manner to the unresolved crisis of providing shelter for many of our most vulnerable citizens.

Although raised in a family home in the Lower Mainland, I have spent my entire adult life as a renter in

many towns and cities across Canada. Based on my own experience as a tenant for 17 years in my

father’s birthplace, Victoria, I have witnessed the growing gentrification of my own neighbourhood,

James Bay. I have also seen the growing displacement of hundreds of tenants due to the extensive

refurbishment of high-rise apartments and the demolition of older homes replaced by multi-storey

condominiums, well beyond the ability of many middle-income residents to buy or even to rent.

It is disconcerting to live in a place where home-ownership is an unattainable dream for many young

working families. If city centres are transformed into high-rise “smart” glass towers with high security

systems that welcome only well-heeled tourists accommodated in suites owned by absentee landlords,

whose quality of life does the city really support and sustain?

As housing costs soar, even here in a quaint colonial outpost on the southern tip of Vancouver Island,

tenants, who form the majority of the City’s households, are facing a chronic rental shortage,

exacerbated by consistently low vacancy rates. When not faced with eviction due to condo conversions,

hundreds now are threatened by a growing ‘renoviction’ trend in the City. These factors are also

compounded by sharp increases in rents for upgraded apartment units and luxury-priced condos, and

an increasing trend among landlords to impose costly fixed-end leases to avoid rent controls. Not

surprisingly, this precarious state of affairs weighs heavily upon students, seniors, and moderate income

working people whose only affordable option is renting as opposed to buying a roof over their heads.

As if this were not enough, many new condo owners are now purchasing units as investment properties

in the core area and surrounding neighbourhoods, while owners of single-family “character” home are

building garden flats and converting their secondary suites. This is not being done to accommodate

long-term tenants, but rather short-stay vacationers willing to pay premium prices for places near

tourist attractions. This growing trend by property owners, property managers and corporate housing

investors in major cities around the globe who use online platforms, like Airbnb, VRBO and others to

Home Truths: Implications of Short-Term Vacation Rentals on Victoria’s Housing Market

12

market short-term vacation rentals, is now another factor reshaping the urban housing landscape. This

notion of freedom to use one’s property as an investment vehicle rather than a principal residence has

potential negative consequences for many neighbourhoods by potentially limiting options for non-

homeowners to find appropriate and affordable shelter.

This context has prompted me to ask: What is the extent and nature of Airbnb listings in the City of

Victoria? What are the implications of that information in relation to the rental housing market here

as well as possible regulatory options for short-term vacation rentals in the City.

2.3 Beyond the bravado, buildings, and beautiful gardens

The City of Victoria’s Strategic Plan 2015-2018 states that: “Victoria is a leading edge capital city that

embraces the future and builds on the past ... Victoria is a city that is liveable, affordable, prosperous and

vibrant, where we all work in partnership to create and seize opportunities and get things done.”

17

Prior to the arrival of the European explorers in the late 18

th

century, Victoria was inhabited by the Coast

Salish Nation including the Songhees and Esquimalt indigenous people. In 1841, the Hudson’s Bay

Company established its first trading post. Later a fort and settlement was built, followed by the City’s

development as a port, supply base and outfitting center in the Gold Rush of the 1850’s. Victoria’s

position as a commercial center gradually diminished with the expansion of the trans-Canada railway, as

roads and infrastructure for the province and growing international trading hub of Vancouver emerged

in the early 20

th

century.

The provincial capital, incorporated in 1862, is home to a population of 83,000 and serves a

metropolitan administrative center for a region comprised of 360,000 inhabitants. Greater Victoria’s

population is projected to grow by 4.5 percent every 5 years between 2010 and 2025,

18

while the City’s

population is expected to increase by approximately 20,000, reaching 100,000 by 2041. The most salient

changes in demographics over the next three decades

19

are the proportion of residents over the age of

65 forecast to increase dramatically from 17% to 29% of the total population. A BMO Wealth Study

recently indicated that 15 percent of Canadian baby boomers are planning to retire in Victoria. During

the same time frame, the proportion of children and young adults is anticipated to decline; families are

encouraged to seek accommodation on the booming West Shore or Saanich peninsula rather than in the

city.

Today, the city’s economy is based on providing jobs in government services, health care, and education

and retail services. The City continues to fulfill its traditional role as a pre-eminent tourist destination

and maritime service sector through its naval base and private sector shipyard maintenance work.

17

City of Victoria Strategic Plan 2015-2018, Amended February 2016, p. 1.

18

Mayor’s Task Force on Economic Development and Prosperity, p. 29.

19

City of Victoria, Official Community Plan – July 2012 (Updated June 23, 2016), p. 21.

Home Truths: Implications of Short-Term Vacation Rentals on Victoria’s Housing Market

13

However, the thrust of new economic initiatives is based on diversification through the expansion of a

its preeminent high-tech industry comprised of more than 800 firms with 23,000 employees generating

an annual revenue in excess of $3.5 billion dollars.

20

Today more than 39 percent of the total income in the region depends on public sector employment,

whereas tourism accounts for six percent of the regional income. Non-employment sources of income

such as pensions, investments, and government transfer payments account for slightly more than one-

third of Greater Victoria’s total income.

The “City of Gardens”, boasts of more than 1,000 hanging flower baskets in summer, offering residents

and more than 4 million visitors annually a taste of its temperate climate, based on more than 2,000

hours of sunshine and 66 cm of rainfall yearly. Among its assets are: Victorian heritage architecture, a

scenic Inner Harbour cityscape, natural green spaces including the venerable Beacon Hill Park, numerous

walking and bike paths, not to mention its historic museum and other cultural amenities that invite both

residents and visitors from afar to enjoy them.

The most pressing urban issues facing the City are those related to land management and development,

significant infrastructure upgrades and transportation network redesign. But more importantly, one of

the critical questions is how to accommodate the anticipated growth in population and changes in the

regional economy over the next several decades. This is no small matter when the city and region are

facing major natural hazards such as earthquakes, wind and storm surges, as well as climate change—

which represent a significant threat to life and property. Little attention has however been paid as to

how to mitigate such risks while furiously expanding high-priced residential development in the core.

Without a serious emergency plan for the City, or a long-term development plan (taking into

consideration high-risk areas and extensive reconstruction following a major disaster re ports, roads,

bridges, utilities and underground services)—citizens and tourists alike would be left to fend for

themselves.

Victoria’s economy has traditionally relied on public administration jobs but these may be curtailed

during long-term slow growth periods, while the tourism sector faces numerable challenges: a strong

Canadian dollar, demanding cross-border security, higher energy costs associated with an island location

and increased competition from the dozen surrounding regional municipalities offering greater supplies

of commercial and industrial land and major retail expansion opportunities.

The most noticeable test, however, will be felt in the capacity of the City to integrate new ground-

oriented housing under the existing zoning structure in a well-built environment. This is also

compounded by the question of how to accommodate high to medium densities in the core area and

housing within the neighbourhoods that is more affordable, and development in village areas that also

supports shops, services and amenities within walking distance of households.

20

Viatec http://www.viatec.ca/cpages/about

Home Truths: Implications of Short-Term Vacation Rentals on Victoria’s Housing Market

14

Few purpose-built apartments have been constructed over the past four decades. As a consequence, the

market for condominiums, new multi-storey buildings and those converted to condos in high-rise

apartment blocks (particularly in the downtown urban core areas) has increased the competition for

both potential homeowners and real estate investors. Meanwhile, the older rental housing stock (built

prior to 1971) is deteriorating or reaching the end of its life cycle and will eventually need to be

replaced.

With the cost of land and construction in urban areas increasing significantly over the past decade, and

growing servicing costs, municipal governments are expanding their tax base primarily through higher

density, premium-priced multi-storey condominium properties. The growing trend toward

neighbourhood gentrification poses a dilemma. Can affordable rental housing units be built in cities to

fulfill the growing demand for 1) workforce housing, and 2) accommodation for many seniors on fixed

incomes or those with special needs living on modest incomes. There is however a growing divide

among home-owners and tenants when it comes to quality of housing in the city. While new housing

units conform to the new seismic building codes, the old rental housing stock may be receiving a

premium makeover but they are not being upgraded to seismic standards. After a major earthquake, it

will be rental properties that will sustain the burden of catastrophic loss, and it will be tenants who will

be obliged to live without shelter on the streets.

2.4 Airbnb and the “sharing” economy

The fast-growing “sharing” economy is emerging as a disruptive force reshaping the economy in

transportation (Uber and Lyft ride-sharing/delivery services, or Google’s driverless cars), online retail

platforms such as Amazon, social-media information sharing platforms like Facebook and Twitter, or

shared travel accommodation platforms such as Airbnb, VRBO, and HomeAway.

Airbnb, one of the brightest stars of the ‘sharing economy,’ was established in 2008 after their American

founders rented out an airbed in their spare room in San Francisco to bring in some extra cash. Almost

ten million ‘shared’ lodgings listings later, this $40 billion (US) home-sharing digital platform now does

business in 190 plus countries and 34,000 cities— soundly trouncing the business valuations of their

main competition, hotel chains like Hilton, Marriott, and Hyatt, while operating with limited regulation

or oversight.

21, 22,

And, while many celebrate the arrival of juggernaut Airbnb on the urban landscape,

(the largest lodging company in the world, with more than 3.1 million rooms), some see the heart of

their cities imploding, like the people of Paris, France.

23

21

Matt Egan, “Hilton: We’re not scared of Airbnb”, CNN, October 28, 2015

http://money.cnn.com/2015/10/28/investing/airbnb-hilton-hotels/

22

Brian Solomon, “Airbnb Raising More Cash at $30 Billion Valuation”, Forbes.com, Sept. 22, 2016.

http://www.forbes.com/sites/briansolomon/2016/09/22/airbnb-fundraising-850-million-30-billion-

valuation/#540496eb66f2

23

Alison Griswold, “Paris is blaming Airbnb for population declines in the heart of the city”, Quartz, Jan. 5, 2017.

Home Truths: Implications of Short-Term Vacation Rentals on Victoria’s Housing Market

15

This year the company will have booked $12.3 billion

24

in rentals all over the globe, while the number of

guests is expected to soar to a half-billion by 2025 according to the investment firm Cowen & Company.

Billed as an alternative accommodation service, this privately held company that does not disclose its

revenue or losses, reportedly reached $900 million in revenue in 2015.

This is remarkable for a “gig economy” company, almost a decade old that offers a digital platform

linking home-owners looking to rent out surplus space with travellers seeking a local, non-hotel

experience. Not your average home-sharing short-term sub-letting business, the Airbnb model

promotes and facilitates a variety of financial services including insurance-like products to hosts and

guests, while maintaining centralized control of all listings. In return, Airbnb takes a 3 percent

commission (before fees and taxes) from home-owner “hosts” while “guests” pay Airbnb an additional

service charge of approximately 6-12 percent on all bookings.

The company makes a number of claims concerning its positive impacts on the quality of life in cities

whose “people-to-people platform ...by the people and for the people that was created during the Great

Recession to help people around the world use what is typically their greatest expense, their home, to

generate supplemental income.”

In November 2015, Airbnb launched its “community compact” as a first step in establishing relationships

with the cities in which it does business. The purpose of such a commitment is to “work with our

community [of hosts] to help prevent short-term rentals from impacting the availability and cost of

permanent housing for city residents”.

It is precisely this underlying pledge to its home-sharing partners which is at the heart of whether this

business model serves only homeowners and short-term vacation renters at the expense of long-term

local tenants. Slee (2015)

25

argues that while the “sharing” economy allows its members “access” to the

use of a variety of assets such as cars, power tools, talents of others and homes (whose owners are

members of a self-regulated network) linked to each other by way of a peer-to-peer platform, the

business model is a form of unregulated monopoly to maximize profits for the platform owners,

intermediaries and retailers.

These alleged benign on-demand home-sharing platforms do more than disrupt the economies of

expensive hotel chains. They foster a new form of privileged consumption, and market ‘lifestyle as a

service’. Locals will find themselves expelled from their homes to satisfy the self-serving needs of short-

term property owners catering to an influx of tourists. This will lead to a precarious, unsustainable state

of affairs for all cultures and subcultures. As contradictions sharpen, politicians and citizens alike will be

asked to choose sides; however, this matter is never addressed in the new STVR policy for the city.

24

Katrina Brooker, “Airbnb’s Ambitious Second Act Will Take It Way Beyond Couch-Surfing”, Vanity Fair, November

2016, http://www.vanityfair.com/news/2016/11/airbnb-brian-chesky

25

Tom Slee, What’s Your’s is Mine – Against the Sharing Economy (OrBooks, January 1, 2015)

Home Truths: Implications of Short-Term Vacation Rentals on Victoria’s Housing Market

16

Chapter 3. Victoria’s Short-Term Vacation Rental Market

and the Long-Term Rental Housing Market

3.1 Salient features of the short-term vacation rental market in Victoria

The City of Victoria Staff Report, October 7, 2016 to Council on “Short Term Vacation Rentals”

26

contains

a selection of testimonials from local residents extolling the benefits of this new tourism industry in

town. These remarks focus, among other things on, ”12 Reasons to support Airbnb and the home-

sharing economy”. These include everything from:

assisting new home-buyers entering the housing market to pay off their mortgages,

creating new service jobs as housekeepers, part-time maintenance contractors,

relieving shortages in hotel space, and

helping visitors stay in large family mansions that “might be sold, or bulldozed and replaced

(often by foreign owners).

Other Airbnb supporters highlight the “nurturing community” virtues of the Airbnb experience for

visiting grandparents who can stay nearby their families in neigbhourhoods, as well as offering respite

places for hospital patients, home-stay locations for visiting students and as “affordable getaways after

exams”. They go further by suggesting that by sharing secondary suites in homeowner-occupied houses

and making connections with guests near and far, hosts can make an income that allows them to keep

their homes and make a valuable contribution to local economy without any measurable negative

impact on the existing rental stock in Victoria.

Apparently the Airbnb data shared by these supporters revealed that 539 hosts earned an average of

$5,700 annually for 49 days worth of tourist accommodation, generating more than $3 million in

revenue for the hosts and additional guest expenditures of $5,128,000 for the local economy.

However, what these testimonials didn’t say is that if these tourists came to Victoria, they would have

spent their money on a host of goods and services whether or not they stayed in Airbnb units or in a

hotel. Furthermore, where is the evidence to assert that a tourist in Victoria is worth more than a

permanent resident? Tenants pay rent, buy groceries and other goods and services, pay income taxes,

property taxes and utility fees. Airbnb tourists pay no lodging taxes, no sales tax - in fact, many receive

GST rebates on their expenditures if they live outside of Canada.

Whatever one may think of the ‘home-sharing’ philosophy, the ever expanding mission of Airbnb is not

only to become the premier if not global leader in the home-rental business but also a travel

26

Liza Rogers, Community Connector & Consultant attachments and testimonials regarding support for Airbnb

enterprises and the home sharing economy in Jonathan Tinney’s, Short-Term Vacation Rentals Report, City of

Victoria, October 7, 2016.

Home Truths: Implications of Short-Term Vacation Rentals on Victoria’s Housing Market

17

entertainment and activity broker to sell all sorts of services such as guided tours, musical outings, as

well as transportation services which could put Airbnb in direct competition with other gig economy

transport companies like Uber, Lyft and Google.

While there are no doubt many benefits that hosts derive from operating Airbnb rooms, suites, and

entire homes, there is a growing body of anecdotal evidence that many of these alternative rental

accommodations are located in the same areas that have a higher proportion of rental housing stock in

the core areas and surrounding neighbourhoods. In an environment of soaring land values and

premium-priced high-density multi-storey private developments in popular seaside tourist destinations

(e.g. Victoria, Vancouver, San Francisco, Barcelona, or Venice), and skyrocketing rents due to a dwindling

supply of affordable rental housing stock, long-term tenants (LTRs) are facing displacement pressure

from new condo-dwelling investors and corporate Airbnb operators in these areas.

Enterprising property owners are seeking ever more profitable ways to maximize their return on their

investment by converting affordable housing to unlicensed online hotels. The short-term vacation rental

model, promoted by companies like Airbnb, poses serious questions as to whether long-term tenant

needs are being sacrificed in favor of a city that expands its tax base by rewarding home-owners. Those

without security of housing tenure are increasingly sent to the periphery of cities if not the hinterlands,

where even less rental housing stock is available.

They City of Victoria’s short-term vacation rental (STVR) market, (approaching almost 1,000 units) is

approximately 15 percent the size of the Vancouver market.

Table 1 - Growth of Airbnb Active Listings in Victoria 2008-2016

2008 1 2013 133

2010 5 2014 256

2011 22 2015 535

2012 62 2016 938

Source: Airdna LLC (US) https://www.airdna.co/city/ca/victoria - December, 2016.

Victoria has seen the spectacular growth of Airbnb units since the founding of the company in 2008.

Particularly since 2012, the number of Airbnb listings has grown 15 fold consistent with a sharp increase

multi-storey condominium construction projects in the downtown core and VicWest as well as mid-rise

condos in James Bay.

Why do landlords prefer Airbnb guests to long-term tenants? Owners maintain flexibility and control in

deciding who, when, what length of time, and how much to charge the occupant. They are not governed

by any rent controls or tenancy legislation nor are they subject to any taxation or health and safety

Home Truths: Implications of Short-Term Vacation Rentals on Victoria’s Housing Market

18

licensing requirements. Furthermore, payment is upfront and guaranteed by the booking platform;

reviews are given for both prospective tenants and landlords, and through Airbnb’s liability insurance

option, any damage and repair costs related to guests are covered up to a value of one million dollars.

A Report to Council by the City of Victoria’s Economic Development Office, dated October 16, 2014,

27

indicated a recommendation by staff to “continue strategic discussions with Airbnb towards a possible

working partnership to address the core areas of concern.”

This report summarized a few salient Airbnb statistics underlining the importance of this new revenue

generating segment of the market benefitting homeowners with implications for the tourism industry.

Apparently after Airbnb announced its first partnership with Portland, Oregon, the City of Victoria

contacted the company “to express an interest for Victoria to be a partner in Canada”.

In 2014, it was reported that more than 1,019 hosts used Airbnb since 2008, of whom 354 had active

listings in 2014 serving 7,336 guests (April 2013-March2014), equivalent to 30,017 guest nights with an

average length of stay of 4.1 days. The staff report further reported that “the demographic using this

site is just the type of visitor we want in our downtown.”

The report also highlighted the City’s “core areas of concern” in order to:

“adapt and evolve as and where necessary the wording of our relevant zoning and bylaws

covering the needs of those home owners providing their homes for short term rentals through

sites such as Airbnb”;

“working to ensure a more even playing field for short-term accommodations by evolving

towards a fair taxation approach (i.e. applying something similar to the hotel tax for Airbnb

listings)”;

“working to ensure that Airbnb listings are available for emergency accommodations if required

in the event of a disaster”;

“shared promotion of the city and neigbourhoods and local businesses as a leading tourist

destination”.

In 2016, the City of Victoria adopted amendments to the Zoning Regulation Bylaw to reduce parking

requirements for secondary suites. It also revised regulations for such suites “to develop and implement

programs and events to assist homeowners who may be interested in adding a new secondary suite—or

legalizing an existing secondary suite—to understand the benefits and possibilities associated with

secondary suites, and the requirements that must be met to establish them.”

28

27

Sage J. Baker, Economic Development, City of Victoria, Memo to Council: “Update re possible partnership with

Airbnb”, October 16, 2014.

28

Jonathan Tinney, Director, Sustainable Planning & Community Development, City of Victoria, Memo to Council

Re: Secondary Suites – Part I Regulatory Changes, October 28, 2016, p. 1.

Home Truths: Implications of Short-Term Vacation Rentals on Victoria’s Housing Market

19

While these changes were made ostensibly to increase the number of livable, safe and affordable

secondary suites as a rental option in the City, the thrust of this initiative was to offer developers a

“proven way of adding gentle densification to neighbourhoods” as well as “improving affordability for

homeowners by increasing their buying power at time of purchase, and offsetting mortgage costs

through the course of ownership”.

This newly minted regulatory change simply means the City will not only allow homeowners to enhance

the value of their property but also offer them a new income stream by legalizing the rental of

secondary suites. The highest rate of return these days is a short-term vacation rental (the average

being $118/night in Victoria versus the average long-term rental of $33/night).

In the absence of a housing inventory for Victoria or the Capital region, there are no statistics on the

actual number of secondary and garden suites in the city. Time will tell whether these changes in bylaws

will house more long-term renters in a market with 0.5 vacancy rate or whether they will simply

enhance the income of home-owners at the expense of tenants. It also remains to be seen whether

supporting online platforms that support the independent travelling public is simply a way of facilitating

high-profit short-term rentals for landlords in urban centres while doing little to contain rising rents and

protect dwindling rental housing stock.

The City may have expressed its concerns about the growing presence of an alternative accommodation

industry; clearly, it has a keen interest in facilitating the growth of its residential tax base. Civic

politicians have many expectations to meet. These include satisfying the complex needs of real estate

development interests, a growing number of personal and commercial home-sharing enterprises, as

well as promoting its traditional hospitality industry partners.

Many of the Airbnb listing photos and descriptions reveal they are located primarily in recently

constructed premium priced high-rise condos with panoramic views of the Inner Harbour and the U.S.

Olympic peninsula. Still others are located in larger “character” homes with self-contained suites or

accessory garden cottages in the city’s upscale neighbourhoods of James Bay, Fairfield and Fernwood.

These patterns in the Victoria market reflect similar Airbnb results world-wide, where their lodging

portfolio is comprised of two-thirds full-time entire units (almost half of which are condo or apartment-

like accommodation) and the remainder are rented as private rooms.

29

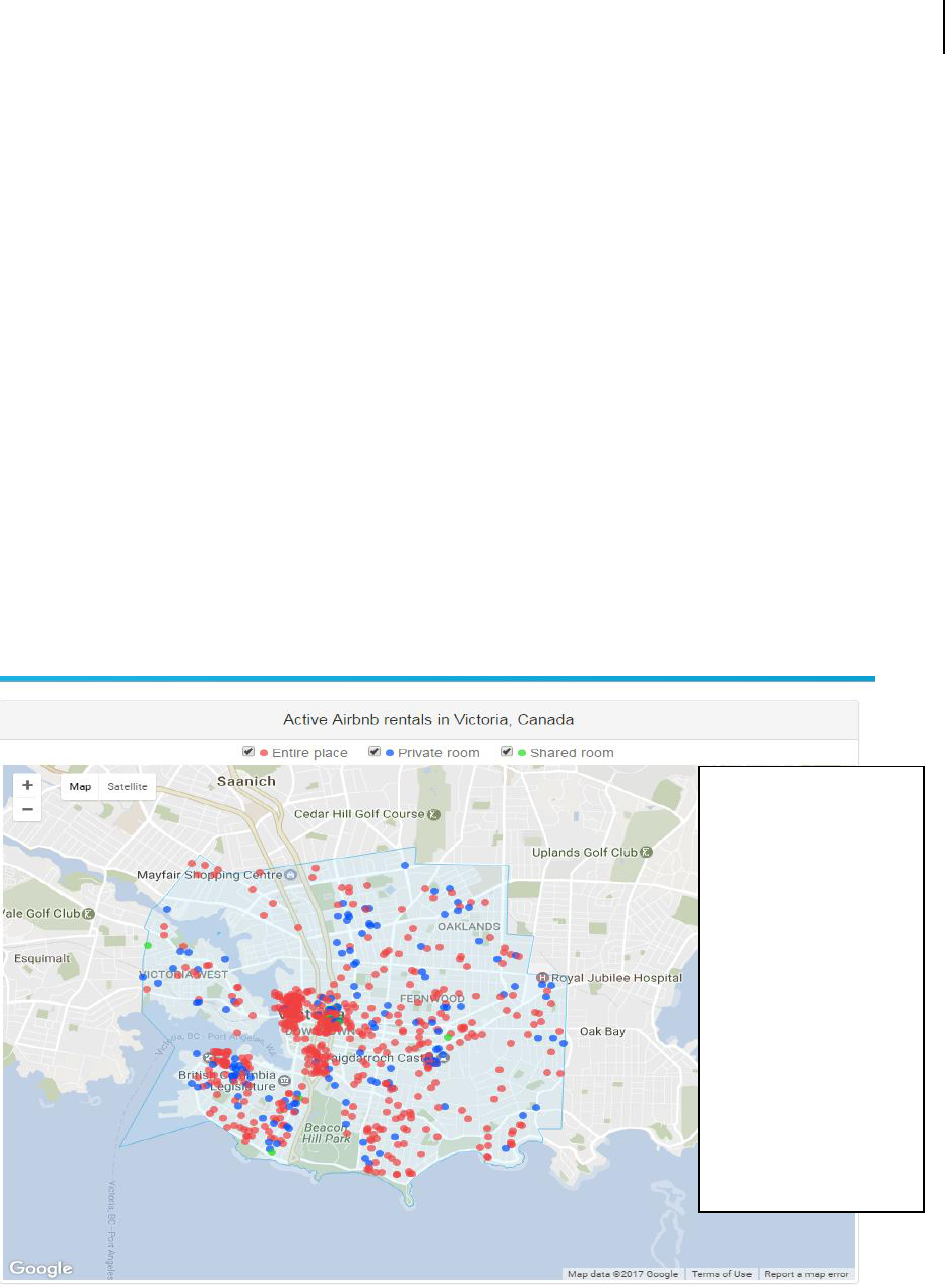

While modest growth in new housing units has occurred in many of Victoria’s neighbourhoods with the

exception of the Downtown core, Harris Green, and VicWest (2006-2011), the largest concentrations of

Airbnb units has occurred in neighbourhoods with the highest proportion of rental units: Downtown,

Harris Green, Fairfield and James Bay. (See Table 2 below.)

29

Ethan Wolff-Mann, “The Big Reason why Airbnb terrifies the hotel industry”, Yahoo Finance, Jan. 5, 2017.

http://finance.yahoo.com/news/airbnb-dwarfs-hotels-in-room-availability-162135372.html

Home Truths: Implications of Short-Term Vacation Rentals on Victoria’s Housing Market

20

Table 2 - City of Victoria Neighbourhood Analysis of Airbnb listings versus Total Number of

Housing Units, % Change in Number of Housing Units 2006-2011, and Housing Tenure

No. %Airbnb

Airbnb Entire

Listings Listings/

(Ave. % Multiple Total No. % Change (%) Units

Price Units Housing Housing Units Rented

Neighbourhood per night) Listings Units 2006-2011 Owned

Burnside Gorge 10 ($120) 90/0 2,795 1 1,755 (63%)

1,040 (37%)

Downtown 134 ($127) 87/40 1,425 68 1,040 (73%)

385 (27%)

Fairfield 85 ($117) 75/31 6,780 1 3,735 (55%)

3.045 (45%)

Fernwood 66 ($ 97) 71/70 4,840 -2 3,095 (64%)

1,750 (36%)

Gonzales 22 ($120) 73/41 1,710 1 500 (29%)

1,205 (71%)

Harris Green 15 ($108) 87/20 1,350 11 875 (65%)

475 (35%)

Hillside-Quadra 28 ($ 81) 50/14 3,685 -1 2,205 (60%)

1,475 (40%)

James Bay 123 ($141) 75/58 6,695 0 4,645 (69%)

2.045 (31%)

Jubilee 22 ($101) 73/41 2,945 -1 1,780 (60%)

1,165 (40%)

North Park 32 ($ 88) 69/28 2,120 1 1,640 (77%)

480 (23%)

Home Truths: Implications of Short-Term Vacation Rentals on Victoria’s Housing Market

21

Oaklands 24 ($ 94) 67/29 3,115 1 1,315 (42%)

1,800 (58%)

Rockland 34 ($139) 53/47 1,830 -2 1,025 (56%)

805 (44%)

Victoria West 45 ($117) 71/40 3,675 16 1,860 (51%)

1,815 (49%)

TOTAL 640 ($118) 74/41 42,995 3 25,475 (59%)

City of Victoria 17,485 (41%)

Sources:

Murray Cox, InsideAirbnb.com – Victoria Airbnb listings, August, 1, 2016

Statistics Canada 2011 National Household Survey (City of Victoria website)

This data reveals that neighbourhoods with the highest proportion of rental units, also have the highest

Airbnb rates per night (with the highest proportion of entire units in either newly built condos

downtown and neighbourhoods within walking distance of the core area or in large character homes

situated in Rockland).

As the Table 3 below indicates, there are several noticeable differences between the Victoria and

Vancouver Airbnb statistics provided by Murray Cox (insideairbnb.com):

higher proportion of Airbnb units in Victoria are for “entire homes”;

higher proportion of multiple listings in Victoria (indicating they are likely to be operating as

commercial enterprises as opposed to mortgage helpers);

higher percentage occupancy, longer stays, and higher estimated monthly income for Airbnb

hosts in Victoria.

Home Truths: Implications of Short-Term Vacation Rentals on Victoria’s Housing Market

22

Table 3 - Vancouver & Victoria Comparative Airbnb Statistics – 2015/16

Area Total % Entire % Occupancy Price/ Est. Mthly. % Multiple

Listings Homes (days occup.) Night Income Listings

CRD 1,691 66.6 31 (114) $124 $1,041 40

Victoria 640 74.4 38 (139) $118 $1,277 40.5

James Bay 123 74.8 35 (126) $141 $1,328 57.7

Downtown 134 87.3 45 (165) $127 $1,681 39.6

Vancouver 4,728 67.2 24 ( 87) $127 $ 844 33.3

Downtown 999 80.9 32 (116) $157 $1,386 42.6

West End 593 70.3 26 ( 98) $118 $ 832 28.3

Kitsilano 567 71.8 20 ( 72) $140 $ 745 25.6

Sources:

Inside AirBnB – Vancouver (neighbourhoods) published Dec. 3, 2015 -

http://insideairbnb.com/vancouver/

Inside AirBnB - Capital Regional District and City of Victoria (neighbourhoods), published Aug. 1, 2016 -

http://insideairbnb.com/victoria/

What both Victoria and Vancouver Airbnb listings show is that the majority of listings are for “entire

homes”. Many of these units are rented for more than 100 days per year (consistent with other

metropolitan areas where Airbnb operates), suggesting that the owners are not using these units as

their primary residences. Furthermore, the largest concentration of the home-sharing listings is in the

downtown core and contiguous neighbourhoods that are in close proximity to major tourist attractions,

entertainment, and restaurants.

A case can be made that those who are offering “entire homes” to travellers as opposed to long-term

tenants are now fuelling a growing Airbnb sub-economy comprised of third-party property management

companies. The purpose of these intermediaries is to help absentee owner “hosts” maximize their

return on their assets by offering “guests”, concierge and security services as well as housekeeping and

personal transportation and guide services.

Home Truths: Implications of Short-Term Vacation Rentals on Victoria’s Housing Market

23

While it is true that over 80 per cent of Airbnb hosts in Victoria offer single listings, as is shown in Table

4 below, the most lucrative segment of the short-term rental business (now euphemistically called a

“home-sharing club”), comes from multiple listings. These are property owners or management firms

offering two to five or more listings with higher-occupancy rates than single unit owners. These

commercial interests, representing real estate developers or investment firms, often purchase multiple

units in large residential strata title complexes are now operating flexible accommodation enterprises

that rival the existing lodging industry. They have little incentive to serve the housing needs of long-term

tenants.

Table 4 - A Profile of City of Victoria Airbnb Active Listings, December 2016

Total Number of Airbnb Active Listings (Dec/16): 937

337 in Downtown (36%); 140 in James Bay (15%)

(49%) other neighbourhoods

Total Number of Airbnb Hosts: 647

532 hosts – single listing (82%)

115 multiple listing hosts (18%)

o 73 hosts – 2 listings

o 18 hosts – 3 listings

o 10 hosts – 4 listings

o 14 hosts – 5+ listings

694 listings (74%) are available for rent 4-12 months a year

243 listings (26%) are rented 4-12 months a year

Total Number of Airbnb Listings

Victoria (August 2015-August 2016) 955

Source: Airdna LLC (US) https://www.airdna.co/city/ca/victoria - December, 2016.

According to the documentation provided in the Staff Report to Council in the Fall of 2016 on Short-term

Vacation Rentals

30

, 539 hosts in 2015 hosted 16,070 guests (more than double 2013-14), typically about

49 days during the year for an average stay of 3.5 days generating an annual income of $5,7000 for a

typical host. This is however only a partial picture of the Airbnb “sharing” economy in Victoria.

Using the December 2016 Airdna statistics (based on 937 active listings) and a nightly average price of

$125 for units in Victoria, the smaller multiple listing hosts generated more than $10 million for their

owners, while the single unit hosts representing more than 80 percent of the owners generated slightly

30

Tinney, City of Victoria Short-Term Vacation Rentals Report, Attachment 2, October 7. 2016.

Home Truths: Implications of Short-Term Vacation Rentals on Victoria’s Housing Market

24

more than half of that total. In other words, this novel home-sharing industry is putting more than $15

million annually into the pockets of homeowners, yet it remains untaxed and unregulated.

What these short-term vacation rental statistics show is that in the traditionally low-season for the

hospitality industry, in December 2016, there were 937 Airbnb listings and 410 Vacation Rentals By

Owner (VRBO)—i.e. a minimum of 1,347 home-sharing listings for the City of Victoria.

On December 29, 2016, the Airbnb website indicated 300+ listings for Victoria, showing an average

nightly rate of $125 for shared rooms and entire units, and an average of $129 per night for entire units.

In the upscale neighbourhood of James Bay, there were 180 listings with an average nightly rate of $137.

More significant is the fact that 76% of these Airbnb listings were for entire units that garnered an

average nightly premium of $159.00.

The most lucrative Airbnb units are those operated as multiple long-term vacation rental listings. These

“hosts” do not reside on the premises and operate these units as commercial accommodation

enterprises through a property management or real estate development company. These multiple

listing owners represent more than 20% of all listings that generate almost 70% of the revenue,

estimated to be more than $10 million annually for the City of Victoria market.

It remains to be seen whether those engaging in enterprising home-sharing activities (i.e. homeowners

and online peer-to-peer accommodation platforms like Airbnb and VRBO) are willing to “share” both the

benefits and the burdens of taxation and regulation like other sectors of the economy.

Home Truths: Implications of Short-Term Vacation Rentals on Victoria’s Housing Market

25

3.2 Victoria’s long-term rental housing market

3.2.1 Population and housing tenure

The City of Victoria, with a population of 80,017 as of the 2011 census

31

is the 14

th

largest city in British

Columbia and the capital of the province.

It represents 22.2 percent of the Capital Regional District population of 359,991, occupying only 2.9

percent (19.47 sq. km.) of the region’s land base. The proportion of the city’s population to the region

has dropped only slightly since the turn of the millennium when it registered 22.8 percent (74,125).

The second largest muncipality by population in the region after Saanich, Victoria has population density

of 4,109 per sq. km., and a growth rate of 2.5 percent, lower than the region’s (4.3 percent).

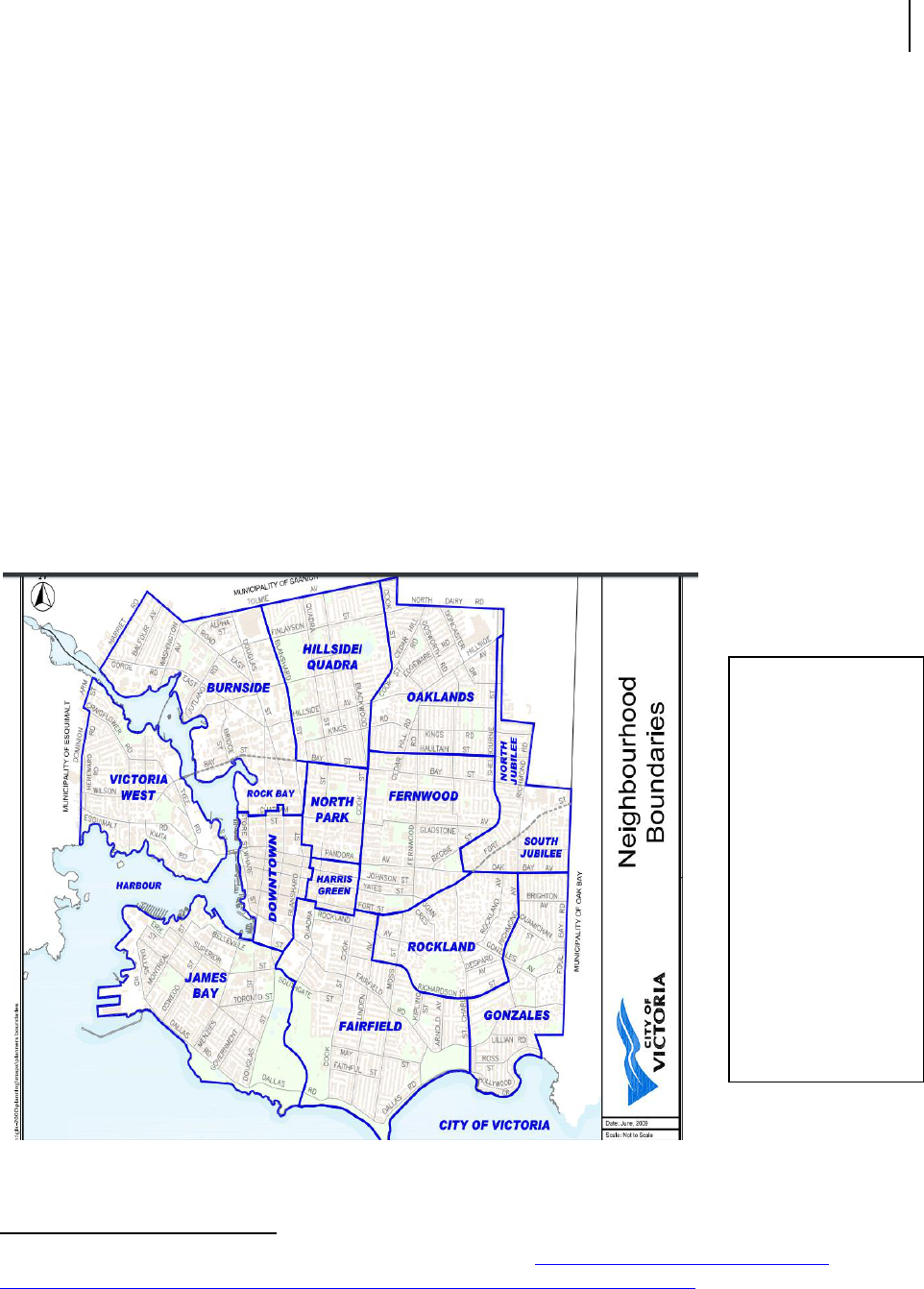

The boundaries of Victoria’s 12 neighbourhoods provide bearings for situating the population, and

residential dwellings, and hotel zones within the city (see Figure 1 below).

Figure 1 – Boundaries of Victoria’s 12 Neighbourhoods

Source: City of Victoria website

31

Focus on Geography Series, 2011 Census, Subdivision Victoria CY - https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-

recensement/2011/as-sa/fogs-spg/Facts-csd-eng.cfm?LANG=Eng&GK=CSD&GC=5917034

City of Victoria

Permanent Rental

Housing and Short-

Term Vacation

Rentals found in all

neighbourhoods

but concentrated

in Downtown &

James Bay which

are also the

primary Hotel

Zones.

Home Truths: Implications of Short-Term Vacation Rentals on Victoria’s Housing Market

26

The 2011 Census reveals that the age group 0-14 years (7,285) accounted for 9.1% of Victoria’s

population, while the working age population 15-64 (58, 025) represented 72.5%, with the largest

cohort being those aged 25-29. Almost 15,000 seniors – those aged 65 plus accounted for 18.4% of the

population, almost 4% higher than the national average. The median age of Victorians is 41.9, which has

increased slightly from 41.6 in 2006.

Of the 42,960 households residing in the City in 2011, approximately 34% lived in family units (with or

without children). However the largest segment of Victoria households 21,070, were single-person

households representing 49% of all households, a considerably higher proportion than live-alone

households in B.C. (28.3%), and Canada (27.6%).

As Table 5 below indicates, the two most populous neighbourhoods in the city are Fairfield (11,650), and

James Bay (11,240), (both of which lie adjacent to the Downtown core sharing access to Beacon Hill Park

and views of the Inner and Outer Harbour) and comprise almost 30 percent of the City’s population.

Table 5 - City of Victoria 2011 Population by Neighbourhood

Neighbourhood

2011

Percent

Burnside

5,860

7.3%

Downtown

2,740

3.4%

Fairfield

11,650

14.6%

Fernwood

9,425

11.8%

Gonzales

4,175

5.2%

Harris Green

1,870

2.3%

Hillside Quadra

7,245

9.1%

James Bay

11,240

14.0%

Jubilee

5,240

6.5%

North Park

3,050

3.8%

Oaklands

6,825

8.5%

Rockland

3,490

4.4%

Victoria West

6,805

8.5%

Total

80,015

100.00

Source: Statistics Canada Census 2011

According to the City of Victoria’s 2012 Official Community Plan, it is anticipated that over the next three

decades “at least 20,000 new residents and associated housing growth is shared across the city in the

following approximate proportions: 50% in the Urban Core; 40% in or within close walking distance of

Town centres and Large Urban Villages; and 10% in Small Urban Villages and the remainder of the

residential areas.”

32

32

City of Victoria, 2012 Official Community Plan, p. 34.

Home Truths: Implications of Short-Term Vacation Rentals on Victoria’s Housing Market

27

As seen in the map below, the Urban Core area (peach through burnt umber/red hues), includes a

significant portion of Victoria West, Downtown, Harris Green, part of North Park, and the Inner Harbour

side of James Bay. This is also the area that has seen the highest concentration of new condo

construction and Airbnb growth in the City of Victoria since 2012.

Source: City of Victoria, 2012 Official Community Plan, p. 36

The City of Victoria reported in 2015

33

that of the new housing development units applied for from 2012

to 2015, 64% were located within the Urban Core, while 21% were located in or within walking distance

of a Town Centre or Large Urban Village, 15% were located in a Small Urban Village or the remainder of

the residential areas. In 2015 alone over 80% of the new development occurred within the Urban Core.

33

City of Victoria, Official Community Plan Annual Review 2015, p. 12.

Home Truths: Implications of Short-Term Vacation Rentals on Victoria’s Housing Market

28

This is the high-growth, high-density condo development target area, as well as where one also finds a

concentration of premium-priced short-term vacation rental units.

It is anticipated that Victoria will accommodate a minimum of 20% of the region’s cumulative new

housing units over the next three decades, while the urban Core is expected to accommodate a

minimum of 10 percent of the region’s cumulative new housing units to 2041. In 2015, Victoria had

accommodated 51% of the region’s new housing units (total new units = 1,986), while the Urban Core

had accommodated 22% (436 units)

34

.

Despite the rising cost of housing during the last three decades, the trend of ownership in Victoria has

been increasing from 34% in 1986 and 1981, 37% in 1996, 37.5% in 2001, 40.5% in 2006 and 41% in

2011. Tenants currently represent 59% of all Victoria occupied dwellings, which is the highest proportion

in of all municipalities and towns in the Capital Regional District which has an average 34%.

As Table 6 indicates the neighbourhoods with the highest proportion of rental units are in the Urban

Core (including Downtown, Harris Green, and North Park), as well as Fairfield, Fernwood, and James Bay.

Table 6 - City of Victoria 2011 Housing Tenure by Neighbourhood

Neighbourhood

Total Units 2011

Rented Units (Percent)

Burnside

2,795

1,755 (63%)

Downtown

1,425

1,040 (73%)

Fairfield

6,780

3,735 (55%)

Fernwood

4,840

3,095 (64%)

Gonzales

1,710

500 (29%)

Harris Green

1,350

875 (65%)

Hillside Quadra

3,685

2,205 (60%)

James Bay

6,695

4,645 (69%)

Jubilee

2,945

1,780 (60%)

North Park

2,120

1,640 (77%)

Oaklands

3,115

1,315 (42%)

Rockland

1,830

1,025 (56%)

Victoria West

3,675

1,860 (51%)

Total

42,955

25,475 (59%)

Source: Statistics Canada 2011 National Household Survey

Tenants are being squeezed in terms of a dwindling housing stock, vacancy rates below 1 per cent, and

consistently high rents. And, it is long-term tenants who are also facing the impact of a growing “Airbnb

effect”. In fact, alternative short-term lodging is now seen as a more profitable business opportunity

than providing long-term accommodation to the majority of the population: working households and

modest income seniors who live side by side with tourists in nearby Airbnb units, licensed bed and

breakfast, and hotels.

34

City of Victoria, Official Community Plan Annual Review 2015, p. 14.

Home Truths: Implications of Short-Term Vacation Rentals on Victoria’s Housing Market

29

3.2.2 Composition and location of the housing stock

As of the 2011 Census, there were 42,955 private dwellings in Victoria’s 12 neighbourhoods with a

modest growth of 3 percent in the city’s overall housing stock since 2006. Approximately 70 percent of

the City’s housing stock was built prior to 1981, with half of that construction occurring prior to 1961.

Little new housing stock has been added to the City, only 4,995 units (12%) between 1981 and 1990,

with a slower rate of increase (10%) in the period 1991 and the turn of the century when 4,240 units

were added. The years 2001-2011 saw a further decline to 8% in new construction, with only 3,550 units

added to the housing stock.

Figure 2 below reveals that apartments account for the majority of Victoria’s housing stock, with slightly

more than 50% comprising low-rise multi-family rental accommodation with approximately 17 percent

representing more than five storey apartment complexes.

Source: Statistics Canada Statistics Canada Census 2011

What these statistics do not reveal is the fact that in 2016, the City of Victoria lost 158 housing units in

its apartment pool, while 289 units were added to the condo rental pool, and more than 400 units of

accessory housing were added to the Greater Victoria housing stock.

What is often overlooked is the fact that between 2015 and 2016, Airbnb, a growing competitor in the

rental housing market, leveraged an additional 403 units from the existing City of Victoria housing

inventory to satisfy the needs of vacationers.

Figure 2 - City of Victoria - 2011

Percentage of Housing By Type

Single/Semi-Detached

House (18.3%)

Town/Row House

(5.2%)

Apartments (76.5%) ,

51 % of which are

fewer than 5 storeys

Home Truths: Implications of Short-Term Vacation Rentals on Victoria’s Housing Market

30

The table below presents a snapshot of the rental housing type in the Victoria Market, in 2010 and 2016.

Table 7 - City of Victoria Rental Housing Market Breakdown, 2010 and 2016

Housing Type

2010

2016

Change

Apartment

Bachelor

2,161

2,268

+107

1 Bedroom

9,378

9,615

+237

2 Bedroom

4,111

4,238

+127

3 Bedroom

175

189

+ 14

Total

15,825

16,310

+485

Condominium

All rented units

2,506

3,195

+689

Other Secondary

Rentals

Single Detached

Semi-Det., Row, Duplex

Other Secondary Suites

5,400

1

6,000

2

+600

Total

23,731

25,195

1,774

Source: Canada Mortgage and Housing, Victoria CMA Rental Housing Market Reports, 2010-1016

1,2

Estimated number of Victoria households living in rental houses, secondary and garden suites based on Victoria

households representing 28% of the total Victoria CMA households identified in the CMHC Rental Housing Market

Reports 2012 and 2016.

Purpose-built apartments represent about 65% of the private rental accommodation market, rented

condominiums - 13% of the market, with the remaining 24% representing secondary rentals in houses