Mission Hospital Charity Care Following HCA’s Acquisition

A Preliminary Report

Mark A. Hall, J.D.

Professor of Law and Public Health

Wake Forest University

mhall@wakehealth.edu

https://hlp.law.wfu.edu/reports-and-issue-briefs/

Wake Forest University

Health Law and Policy Program

January 23, 2024

This preliminary report is one part of a larger study, funded by the Arnold Foundation,

1

examining

what lessons can be learned from the events leading up to, and following, HCA Healthcare’s 2019

purchase of the Mission Health system based in Asheville, North Carolina (NC). Findings from this

portion of the research are being released as a “working draft” in order to give interested parties

a preliminary look at the initial analyses. Comments directed to the author (Prof. Mark Hall)

2

are

welcome. Following revision, a final full report will be issued later this year.

Acknowledgements: Colleagues at Wake Forest University who contributed to this work are

Doug Easterling, Ph.D., Joe Singleton, J.D., and Laura McDuffee.

1

https://www.arnoldventures.org/

2

https://school.wakehealth.edu/faculty/h/mark-a-hall

https://profiles.wakehealth.edu/display/Person/mhall

WORKING DRAFT – SUBJECT TO CHANGE – WORKING DRAFT

1 Wake Forest University, Health Law & Policy Program

BACKGROUND AND SUMMARY

When a for-profit company acquires a nonprofit hospital, a major concern is always what becomes of the

nonprofit’s commitment to charity care. This was certainly the case when it was announced in 2018 that

HCA would purchase Mission Health based in Asheville, NC. One of the core conditions of the Asset

Purchase Agreement (APA) was that HCA would maintain a charity care policy generally equivalent to

what Mission had in place, or to what other large nonprofit hospitals have.

3

Prior to signing that

agreement, Mission assured the public (on a FAQs website it maintained about the sale) that “Joining HCA

Healthcare would not change how Mission approaches … treatment of the uninsured in any way,” and

that “Mission’s charity care would absolutely continue under HCA.”

4

Moreover, HCA claimed, and Mission agreed,

5

that HCA’s standard charity care policy was actually

somewhat more generous than what Mission had at the time. Therefore, when HCA let Mission decide

whether to keep its current charity care policy or switch to HCA’s, Mission’s Board, after analysis, opted

for HCA’s policy. Principally, this is because HCA’s policy covers households up to four times the poverty

level, whereas Mission had covered up to only three times poverty. For instance, in 2024 HCA’s policy

covers a single person earning up to almost $60,000, compared to less than $45,000 income if Mission

had kept its prior policy. For a family of four, the equivalent comparison would be $120,000 rather than

$90,000 household income.

In practice, however, this report finds that genuine charity care has diminished in systematic and extensive

ways following the sale to HCA, with unfortunate effects on access to health care in western North

Carolina. This has occurred as a result of a number of factors, including:

1) non-obvious limitations that make the charity care policy less generous than what was promoted;

2) more cumbersome procedures for approving charity care; and

3) financial policies requiring prepayment that disproportionately affect low-income patients.

As a result, the proportion of patients that Mission Hospital reports as being treated on a charitable basis

dropped substantially, and low-income patients who are uninsured no longer reliably receive care

regardless of their ability to pay.

This report provides a detailed account of how and why Mission Health’s charity care has diminished

following the sale to HCA despite its previous leaders’ contrary expectations. Our intent is to tell a

cautionary tale that will be useful to the other health systems that are considering a sale, especially a sale

from a nonprofit to a for-profit firm.

3

https://searchwnc.files.wordpress.com/2018/09/388077864-mission-health-hca-healthcare-inc-asset-purchase-

agreement-aug-30-2018.pdf

4

https://web.archive.org/web/20180409082221/https://missionhealthforward.org/faqs/

https://web.archive.org/web/20180331010545/https://missionhealthforward.org/faqs

5

On its FAQs website about the proposed sale, Mission said that HCA “has one of the most generous charity care

policies in the industry, even more generous than Mission Health.”

https://web.archive.org/web/20180409082221/https://missionhealthforward.org/faqs/

https://web.archive.org/web/20180331010545/https://missionhealthforward.org/faqs/

WORKING DRAFT – SUBJECT TO CHANGE – WORKING DRAFT

Wake Forest University, Health Law & Policy Program 2

METHODOLOGY

This research is based on extensive document review, analysis of financial data, literature review

(including media reports),

6

and interviews with four dozen “key informants.” These interview sources are

North Carolina professionals, mostly from Asheville and surrounding counties, well placed to have

insightful knowledge about the questions studied. Sixteen are clinicians, sixteen were at some point in

management or on the board at Mission Hospital, six are government officials (former or current), eight

have worked as clinicians or administrators primarily serving low-income uninsured patients in the area,

and five work with health care public policy issues in other ways. (Some interview sources fall into two of

these categories.)

Potential interview sources were identified in a variety of ways including their affiliations with key

institutions,

7

and respondent-driven referrals. Unavoidably, this is somewhat of a “convenience sample”

because a dozen or so who were approached did not respond or agree to participate. However,

recruitment of informed sources continued until reasonable “saturation” was reached, meaning that

substantial new information was no longer emerging. Documentary and interview information was

analyzed using qualitative methods that are standard for this type of research. “Triangulation” is one such

method, by which information from one type of source (interview, documentary, or data) is cross-checked

with information from other types to determine whether either confirmation or inconsistency exists.

CHANGES IN REPORTED CHARITY CARE SERVICE

Mission claims that it provides more charity care under HCA than it did previously.

8

That claim is based on

financial data examined below, but to verify the claim from another data source, we start by examining

data that Mission reports to the state each year on the number of charity patients (measured by various

units of service).

9

Snapshots from 2018 (the last year before HCA) and 2022 (the latest available year)

show a substantial, and in some respects precipitous, drop in charity care services.

Figure 1: Percent of Service Units Classified as Charitable

6

For readability, this report cites publicly available information mainly just by website URL links.

7

To avoid any possible appearance of bias, no sources were identified through the nurse’s union or its

representatives.

8

https://www.independentmonitormhs.com/_files/ugd/9da497_1e9e0db4081a480db68f68596f769e1e.pdf

9

https://info.ncdhhs.gov/dhsr/mfp/data/hospital.html. Mission data appears partially incomplete for the first

three years under HCA, but 2022 data appears to be complete.

WORKING DRAFT – SUBJECT TO CHANGE – WORKING DRAFT

3 Wake Forest University, Health Law & Policy Program

The percentage of hospital days Mission reported as charity dropped by a third (from 3.9% to 2.5%), and

the percentage of outpatient surgeries done as charity fell by almost half (from 4.5% to 2.4%). Stunningly,

the proportion of emergency room visits Mission reported as charity plummeted 86 percent, with a similar

drop of almost 80 percent for charitable visits to outpatient clinics. Overall, Mission reported a 72 percent

drop from (5.8% to 1.6%) in the proportion of its visits or days that were for charity patients.

HCA Mission does not appear to consider these steep declines as being anomalous. In several applications

to the state for “certificate of need” approvals of various services, Mission projects that charity care

service will remain at these reduced levels, equivalent to what it has reported in these initial years under

HCA ownership.

10

UNEXPECTED LIMITATIONS IN HCA’S CHARITY CARE POLICY

This unexpected result arises directly from several critical limitations in HCA’s charity care policy – both

in terms of what it says and how it has been implement. A readily apparent limitation is that HCA’s

policy does not promise to cover any bill less than $1,500.

11

Other limitations, however, are not at all

readily apparent.

Emergent Care Only

Mission’s prior charity care policy

12

applied to all medically recommended services (as do charity care

policies at most other hospitals), but HCA’s policy applies only to “emergent, non-elective” services.

13

The

phrase “emergent, non-elective” uses technical terms of art within the hospital industry whose meaning

is not at all evident, even to many who work in health care. The key contrast is not, as it might appear,

between care that is entirely discretionary versus care that is medically necessary. Instead, the contrast is

between all medically recommended care versus care whose need is especially urgent. The core idea is

that medically necessary care is considered “elective” if it can be scheduled and therefore delayed if need

be, whereas “emergent” care must be done right away.

In one chilling example, a professional who works with low-income patients described someone who had

developed an aneurysm that was at risk of rupturing. Had it ruptured, the patient could have suffered

severe brain injury or even died, but because they were not in immediate distress, HCA Mission refused

charity care.

10

For instance, in a 2023 application for a new PET scanner, it projected that, through at least 2027, 0.8% of

patients served and 0.7% of revenue generated will be on a charity care basis. This projection is based on Mission’s

current or recent level of charity care for similar service.

11

Such bills are covered only at the hospital’s discretion, in unspecified “extenuating circumstances.” Although

Mission’s previous policy did not have this particular limitation, it did impose some graduated partial payment

obligations. However, as noted below, it did not require these payments prior to receiving treatment.

12

https://missionhealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/finassdiscount_policy_04.pdf

13

https://missionhealth.org/financial-services/financial-support/

WORKING DRAFT – SUBJECT TO CHANGE – WORKING DRAFT

Wake Forest University, Health Law & Policy Program 4

Distinguishing Emergent from Medically Necessary Care

One well-documented explanation of this key distinction

14

(from a leading physician-advised

15

consumer information website) explains:

16

"Elective surgery" is the term used for a procedure that can be safely delayed without great risk

to a patient's health, such as cataract surgery. A nonelective (or emergency) surgery is a

procedure that must be performed immediately for lifesaving or damage-preventing reasons,

such as in repairing a brain aneurysm. While both types of surgery are medically important for

a person's health, there are key differences between the two. . . . Simply put, what is not an

emergency is considered to be elective surgery. This means that the procedure can be

scheduled in advance or postponed without compromising the patient’s health and safety.

Contrary to popular belief, the term "elective" does not mean that the surgery is optional or

unimportant; it simply means that the procedure is not quite as time-sensitive as nonelective

surgery. In fact, most elective surgeries are considered to be essential and medically necessary,

whether it's for a major condition (such as a hip replacement) or a more minor one (such as

cataract surgery). Other examples of elective surgeries [include]: Diagnostic surgery, like an

endoscopy; Joint replacement; Kidney stone removal; Carpal tunnel release. ... Examples of

nonelective surgeries include procedures to treat: Cardiac emergencies, such as heart attacks

or cardiac shock; Limb amputation; Brain aneurysm; ... Certain cancers; Abdominal or bowel

blockage.

Researchers estimate that about 90% of surgeries performed in the United States are

considered to be elective, … [and] that nonelective general surgeries represent about 11% of

hospital admissions.

Becker’s Hospital Review, a leading industry news service, reports that “some healthcare professionals

want the public to know exactly how important an ‘elective’ procedure can be,” explaining that elective

“does not describe the acuity of the medical condition or necessity of the procedure. Rather, the use

of ‘elective’ distinguishes those surgeries that are scheduled in advance from emergency surgeries,

such as trauma cases.”

17

According to one physician Becker’s interviewed, “Whether it's pain from a

chronic hernia or the inability to adequately eat because of biliary disease, these [“elective”] issues can

be debilitating." To clarify this understandable confusion, the reporter notes that “physicians are taking

to the web to debunk what can be a misnomer, .... [and] can sometimes be deceiving.”

14

Similar explanations can be found in other sources cited in this section, and in:

https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/what-to-do-when-elective-surgery-is-postponed-202110202620

https://amastyleinsider.com/2013/01/23/emergency-emergent-urgent

https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/treatment-tests-and-therapies/types-of-surgery

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elective_surgery

15

“The website is maintained by 120 health experts, including doctors, trainers, dietitians, specialists, and other

professionals, with the content being reviewed and approved by board-certified physicians.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Verywell

16

https://www.verywellhealth.com/elective-vs-nonelective-surgery-5409504 (with emphases added).

17

https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/hospital-physician-relationships/don-t-let-the-term-elective-fool-you-

physicians-urge-the-public.html. The article quotes one academic physician, for instance, who said “'elective'

surgery doesn't mean optional, it just means it doesn't have to happen right now at 3 a.m. . . . Most cancer and

heart surgeries, for example, are 'elective' in that we can schedule them for Tuesday."

WORKING DRAFT – SUBJECT TO CHANGE – WORKING DRAFT

5 Wake Forest University, Health Law & Policy Program

These term-of-art distinctions are obscured in the Asset Purchase Agreement (APA) that specifies HCA’s

purchase commitments. The APA requires HCA “to provide no less access to necessary medical care

regardless of the ability to pay” than under Mission’s previous charity care policy – using phrasing that at

least suggests – contrary to what HCA’s actual policy provides -- that coverage is intended for medically

necessary care generally.

Due to the obscurity of these technical meanings, both Mission’s board and its managers appear to have

been largely, or almost entirely, unaware of the “emergent-only” limitation in HCA’s charity care policy.

Mission’s existing charity care policy appeared to equate “elective” with “not medically necessary” – a

sensible interpretation, but not the one that governs HCA’s charity policy.

18

Board members who were

interviewed, including some senior members, said that the emergent-only limitation was not given any

attention in deliberations and did not come up in discussions. One reason noted for this lack of awareness

is the relative lack of experience that many Board members had in the hospital industry, which some

former Board members said was a distinctive feature of the 2018 Board that handicapped its deliberations

about the hospital’s sale.

19

Despite the confusion that can be anticipated, Mission’s charity care policy does not explain these critical

distinctions in any way. Initially, Mission did not provide the public any copies of HCA’s policy, despite

repeated requests.

20

After what one source described as “giving them enough hell,” HCA finally posted its

policy, but the posting still does not explain what “elective” care means nor does it draw any attention to

the crucial difference between medically necessary care generally and care that is especially urgent.

21

Instead, HCA appears elsewhere to obscure or deflect attention from this key contrast. In responding to

the NC Attorney General’s inquiry about what exactly HCA’s charity care policy does and doesn’t cover,

Mission’s President contrasted a ruptured appendix, which is covered, with “elective procedures, such as

cosmetic surgery,” which aren’t covered.

22

This fails to acknowledge or even allude to the fact that HCA’s

interpretation of “elective” also excludes a wide swath of medically necessary care that is non-emergent.

The meaning of “elective” hospital care is now apparent, however, due to the COVID-19 pandemic. To

protect patients from infection and cope with surges in critical hospital care, most hospitals cancelled or

postponed all elective care for several months during the COVID crisis, in order to focus on the most

emergent needs. This unprecedented strain on hospitals brought focused attention to how the “elective”

vs. “emergent” concepts apply.

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, the federal government issued guidance that described non-elective

services as those needed to “save a life, manage severe disease, or avoid further harms from an underlying

condition.”

23

In contrast, guidance from the NC Department of Health defined “elective and non-urgent”

as any treatment that could safely be postponed for a month.

24

Various medical groups and experts issued

18

Appendix A in https://missionhealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/finassdiscount_policy_04.pdf.

19

These sources also speculated that Mission’s management preferred less experienced Board members because

that made them more dependent on management’s explanation of relevant factors and considerations.

20

https://www.citizen-times.com/story/opinion/2020/02/11/hcas-management-mission-health-hospital-cause-

deep-concern/4721205002/

21

https://missionhealth.org/financial-services/financial-support/

22

https://www.independentmonitormhs.com/_files/ugd/9da497_1e9e0db4081a480db68f68596f769e1e.pdf

23

https://www.cms.gov/files/document/covid-elective-surgery-recommendations.pdf

24

https://covid19.ncdhhs.gov/covid-19-elective-surgeries-final-0/open

WORKING DRAFT – SUBJECT TO CHANGE – WORKING DRAFT

Wake Forest University, Health Law & Policy Program 6

additional guidance that provided specific examples of procedures that were, or could be, considered

elective. These included: kidney stone removal, cancer biopsy, hernia repair, hysterectomy, cardiac valve

replacement, joint replacement, orthopedic injury repair, back-pain surgery, early stage surgery for

various treatable cancers, and possibly even scheduled Cesarean deliveries.

25

Consequences of Limiting to Emergent-Only

Clearly, then, “elective” does not mean optional or even unimportant. As one hospital system warned,

“Elective surgeries are vital to a patient’s health and well-being. ... Breast cancer surgery like a

mastectomy is critical to address, even though it might not qualify as an emergency procedure needing to

be done [right away].”

26

A group of international physicians similarly cautioned that “[m]any non-

emergent surgeries, such as for cancer care, may face dire consequences if delayed considerably.”

27

These statements of concern address possibly postponing elective care until normalcy is restored. Under

HCA Mission’s application of the concept, however, care that can be postponed for a limited time is, in

effect, postponed indefinitely. For some patients, that means permanently. For others, it means until a

patient’s condition worsens to the extent it is an emergency, or something close to one. The obvious

concern, of course, is that by the time things get that bad a patient’s chance of recovery is quite possibly

diminished greatly. With cancer, for instance, stage 1 progresses to stage 2 or 3 – which is still not

hopeless, but favorable outcomes become substantially less likely. Similarly, absence of early intervention

for treatable cardiac disease or other major organ dysfunction means a patient’s condition continues to

deteriorate before postpone-able care becomes “emergent.”

Yet other medical conditions would likely never qualify as non-elective because they are chronic

conditions people conceivably can just live with. Examples might include hernia repair, major joint

replacement, serious back pain, debilitating carpal tunnel syndrome, various sports injuries, and the like.

If these do not cross the line from postpone-able to emergent, then many people obviously will be left to

cope indefinitely with considerable pain or serious physician limitations. These are conditions that prevent

people from working and that can cause them to slide into depression or become more susceptible to

substance abuse.

These COVID-specified applications of the elective, non-emergent concept do not necessarily describe

exactly how HCA has chosen to implement its charity care policy, at least so far. It is possible – and indeed

likely – that HCA has chosen, at least sometimes, to be somewhat more generous, perhaps due in part to

the scrutiny its management has received. The experience under COVID illustrates, however, how HCA

might further restrict its charity care policy in the future.

Moreover, the uncertainty about how exactly Mission will draw the elective/emergent line means that

physicians who refer patients for medically necessary charity care no longer have the authority they

previously had to determine what services are important enough to merit this request. As explained by

several sources, each such referral has to go through what one source called “the HCA chain of command.”

25

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7107008/

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9388274/

https://www.adena.org/health-focus-blog/detail/adena-health-focus/2022/11/01/elective-surgeries/

https://www.facs.org/media/wfjhq0jw/guidance_for_triage_of_nonemergent_surgical_procedures.pdf

26

https://www.osfhealthcare.org/blog/what-is-an-elective-surgery/

27

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9388274/

WORKING DRAFT – SUBJECT TO CHANGE – WORKING DRAFT

7 Wake Forest University, Health Law & Policy Program

That uncertainty and delay was said to add greatly to the difficulties, discussed in the next section, in

determining in a timely manner whether or not a particular patient’s specific medical needs are in fact

eligible for charity care.

Determine Charity Status only AFTER Receiving Care

In addition to excluding medically necessary care that is not emergent, HCA has imposed several notable

administrative barriers to receiving charity care that were not present under Mission’s previous policy.

Most significantly, HCA does not readily administer its policy in advance of treatment. Instead, typically –

and by several accounts almost always – Mission now determines charity care eligibility only after a

patient has received treatment. Based on several reports, the determination usually is made once a

patient receives a bill they cannot pay, at which point it’s often the case that Mission has already initiated

a collections process.

Classifying care as charitable only after billing a patient is inconsistent with charity’s widely accepted

meaning, which is to offer care with no intent to charge for it. The American Hospital Association, for

instance, states that “charity care is care for which hospitals never expected to be reimbursed,”

28

and they

elaborate that:

Hospitals typically use a process to identify who can and cannot afford to pay, in advance of billing,

in order to anticipate whether the patient’s care needs to be funded through an alternative

source, such as a charity care fund.

29

Certainly, this is not always done, and other hospitals regularly convert some billed charges to charity

status during a financial assistance process. At HCA Mission, however, post-treatment determination

appears to be the overwhelming norm rather than an exception or fallback to a general pre-treatment

determination practice.

In one sense, determining charity eligibility only after treatment is consistent with HCA’s policy restriction

to emergent care, because much emergent care arises unexpectedly, without an opportunity to

determine financial assistance in advance. But conceivably some emergent care can be anticipated, and

thus should be eligible for determination prior to treatment. Nevertheless, based on many reports this

rarely happens, likely due in large part to the administrative barriers discussed below.

Requiring Multiple Re-applications

Another barrier to charity care arises from how frequently patients must go through the application

process. Unlike Mission’s prior practice, HCA does not normally extend eligibility for charity care beyond

a single episode of treatment. One patient advocate who dealt with HCA’s process explained, for instance,

that if an unlucky (or clumsy) person injures their shoulder in a car accident, then falls down some stairs,

and then slices themselves with a kitchen knife, they would have to fill out the entire charity care

paperwork each time they sought care, even if this all happened in fairly quick succession, requiring them

to “go up the flagpole” of approvals each time.

In sharp contrast, Mission’s practice, like that of similar hospitals, had been to maintain a patient’s

charitable eligibility for six or twelve months, once eligibility was established. Doing that allowed low-

28

https://www.aha.org/system/files/content/00-10/10uncompensatedcare.pdf

29

https://www.aha.org/fact-sheets/2020-01-06-fact-sheet-uncompensated-hospital-care-cost

WORKING DRAFT – SUBJECT TO CHANGE – WORKING DRAFT

Wake Forest University, Health Law & Policy Program 8

income uninsured patients to know they could obtain any necessary follow-up care, or address any newly

emerging medical needs, without having to undergo frequent, repeated re-applications. HCA’s position,

however, was said to be that frequent re-application makes sense because a patient’s eligibility for

Medicaid or subsidized insurance can change from month to month based on various family and financial

circumstances.

A telling indication of the change in Mission’s pre-approval policy and practice for charitable service is a

sharp shift in how Mission classifies the payment status of emergency patients. Based on data Mission

reports each year to the state,

30

in 2018, the last full year prior to HCA’s purchase, Mission classified 17.6

percent of its emergency patients as covered by charity. Under HCA, that plummeted to only 2.4 percent

in 2022.

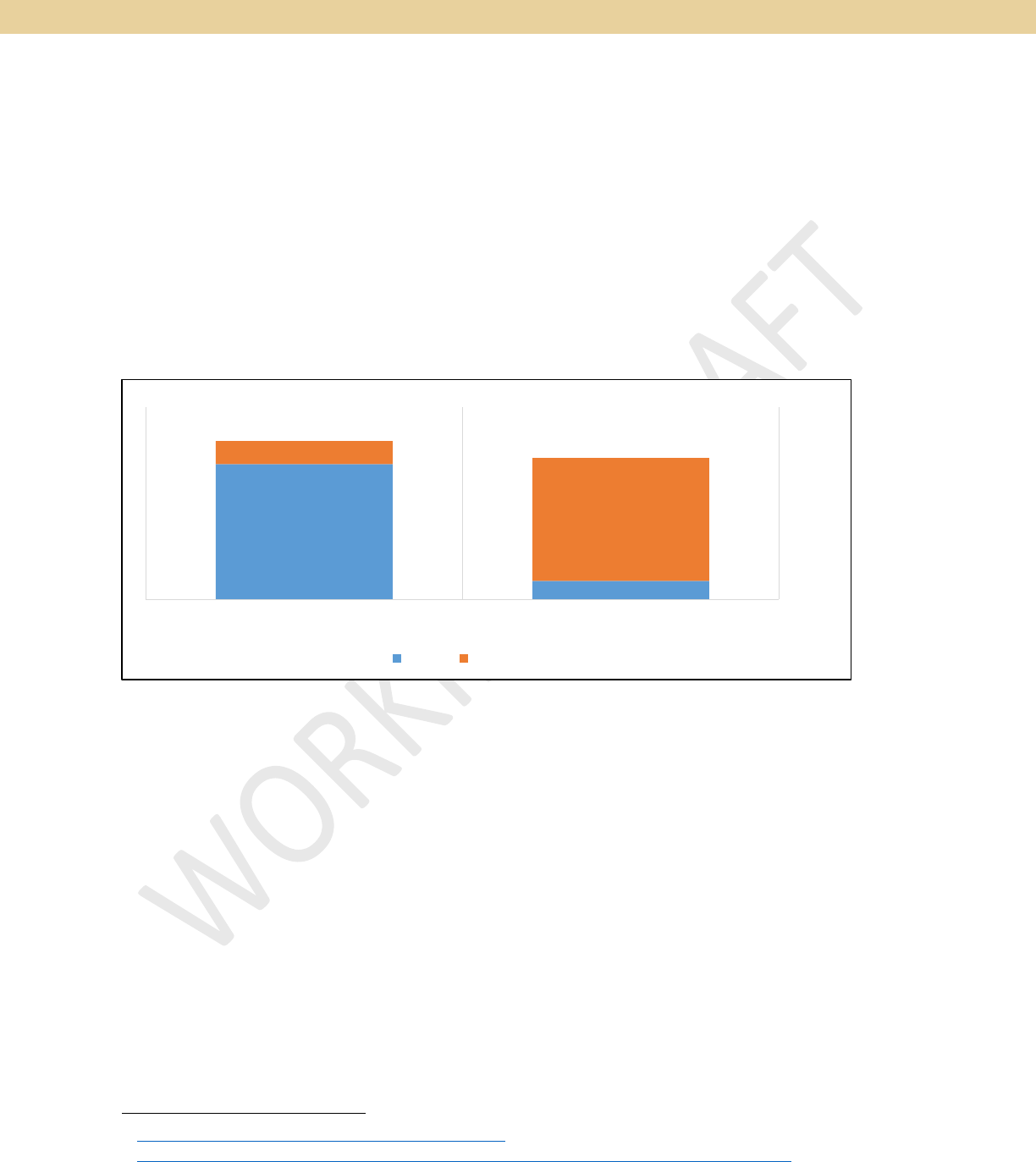

Figure 2: Charity Status of Emergency Patients Before and After HCA's Acquisition

Mission reported in 2018 that three percent or less of emergency patients were “self-pay” (i.e., non-

charitable and without insurance), but under HCA that percentage shot up to 16 percent (for 2022). Likely,

the proportion of emergency patients that are low income and uninsured did not change substantially,

and certainly not this dramatically. However, prior to HCA, Mission had previously screened many of those

patients as eligible for charity care and so continued to recognize them as such when they sought

emergency care. That continuity of status did not continue for most patients, however, under HCA.

Frequent re-application would be more palatable if the process were not laborious, but under HCA it

reportedly is, as discussed below. Several aspects of Mission’s policy facilitated or expedited the

application process, such as presuming eligibility based on enrollment in other social service programs,

and accepting attestations of income if tax forms or pay stubs were not readily available. In contrast,

HCA’s practice under its policy was described as, and seen to be,

31

much more exacting in the

documentation required. As one patient vented at a public meeting, qualifying for charity care used

to be “a piece of cake” but now “it's a terrible, terrible thing [that] now I've got to jump through

30

https://info.ncdhhs.gov/dhsr/mfp/data/hospital.html

31

https://missionhealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/508_Mission-Health-Website-FAA.pdf

Charity, 18%

Charity, 2%

Self-pay, 3%

Self-pay, 16%

PRI OR T O HC A (2018) UNDER HC A (2022 )

Charity Self-pay

WORKING DRAFT – SUBJECT TO CHANGE – WORKING DRAFT

9 Wake Forest University, Health Law & Policy Program

seven hoops and wonder, Am I going to be lucky or not?” Because of this, the patient said they

have basically stopped trying to quality because “I'd rather die in peace.”

Requiring Advance Deposits Regardless of Ability to Pay

Insisting that low-income patients pay a deposit prior to treatment is another HCA Mission policy

inconsistent with the concept of charity and normal charity care practice. Prior to HCA’s purchase, when

Mission was asked whether HCA can “refuse to treat patients who do not pay for treatment upfront,”

Mission answered (on a FAQs website): “Absolutely not.”

32

That has not turned out to be the case,

however. Instead, according to multiple reports from professionals with hands-on experience, HCA

Mission regularly refuses care to charity-eligible patients who cannot pay a substantial deposit prior to

treatment. This is also confirmed by patients’ own descriptions of their experience, collected in the

Appendix. These multiple sources indicate that, repeatedly, patients eligible for charity care who were

scheduled for needed service had their appointments cancelled for failing to pay an advance deposit.

One source, for instance, described a surgeon who noticed that scheduled surgeries were being cancelled

without any notice to them. After inquiring, they learned that HCA Mission called patients the day before

a surgery, or sometimes just the evening before, to ask for pre-payment, and, if that was not received,

HCA Mission cancelled the surgery without any notice to or consultation with the physician. Another

clinician likewise said they discovered this practice only after inquiring, which explained why “a ridiculous

number” of people were not showing up for scheduled service. A third source explained that cancelling

service without notice to the referring clinician could easily result in a patient who needs critical care, such

as cancer treatment, not receiving it without the referring clinician having any reason to know.

Some of these examples are not restricted to charity care, but other sources recounted similar

experiences with charity patients specifically, noting in the words of one that this was “happening left and

right.” (See also the Appendix below.) They also noted that the HCA personnel asking for a deposit were

not inquiring whether the patient was, or might be, eligible for charity status. When clinicians do learn

this happens, one reported that it took “frantic calls” and another said they had to “fight back” to get

situations straightened out, especially when the treatment was critically needed.

Staff Shortage and Inadequate Training

Compounding these various difficulties is HCA Mission’s substantial staffing turnover and cutbacks

[described in a forthcoming report]. By all accounts, these staffing issues have made it much more difficult

than before to determine charity care eligibility at Mission. Multiple sources described, in sometimes

colorful or salty terms, the frustration felt when they repeatedly were unable to reach HCA staff with

knowledge and authority to address charity care issues. One clinician said that it takes “hours of time”

just to get approval for a single routine visit or procedure. Other clinicians or patient navigators referred

to HCA’s “impenetrable systems” and “obtuse” application process that imposed a “huge onus of

paperwork.” They also bemoaned the absence of any “peer to peer” contact and several noted having to

remain on hold for very extended periods of time. The Appendix below provides additional accounts.

32

https://web.archive.org/web/20180409082221/https://missionhealthforward.org/faqs/

WORKING DRAFT – SUBJECT TO CHANGE – WORKING DRAFT

Wake Forest University, Health Law & Policy Program 10

Adding to these burdens, following HCA’s acquisition Mission Hospital declined, for nearly four years, to

make its actual charity care application readily available to the public and the medical community.

33

That

refusal caused a great deal of confusion and uncertainty about what was required to receive assistance,

even among internal hospital staff.

34

HCA Mission eventually posted the policy only after sustained

advocacy pressure.

35

Finally, exacerbating all of this is the difficulty multiple sources noted in knowing what exactly to say once

an HCA person does respond. Although HCA told these sources that it trains its relevant staff on its charity

care policy, interview sources said they did “not find this to be true.”

36

Their experience was that it took

a “constant battle” of communication to address a situation, after which HCA personnel would change

and they would have to “start all over again.”

The experience of several knowledgeable sources was that HCA’s staff usually do not raise the possibility

of charity care on their own. Instead, “you have to know to ask” and you have to know exactly “the right

lingo” to use in in order to make any headway in assisting a patient.

37

As one source summarized, “you

have to know the right people, the right wording, and the right contact information” of who to talk to,

and so “no normal person would ever know how” how to navigate the process.

Net Effects: Emergency Service Only

This poorly designed approach to arranging charity care has caused a great deal of frustration and even

anger, for both the general public

38

and for many in the medical community. The Appendix below provides

excerpted examples, all of which resonate with accounts heard during interviews for this study. One key

informant who previously had gathered pertinent information to better understand the charity care

problems under HCA, said that they “didn’t get one example of this [new charity care policy] working.”

Several others, with extensive experience, stressed that this has all been “a huge change” from how

charity care worked prior to HCA. Before, they “never had a problem” and could “always get care” when

needed, but that now trying to do the same is a “nightmare.”

As a result, several professionals said they have “mostly stopped trying” for charity care approval at HCA,

unless the service needed is not available elsewhere. Even for potentially eligible patients who have

received a bill from Mission, several professionals said they no longer advise patients to apply for charity

care because the effort is too frustrating and futile. One clinician tells their patients needing hospital care

33

https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/finance/hca-owned-system-yet-to-make-charity-care-application-

public-despite-push-from-advocates

https://www.citizen-times.com/story/opinion/2020/02/11/hcas-management-mission-health-hospital-cause-

deep-concern/4721205002/

34

One source recounted that an HCA employee told them: “There have been several versions of the policy; people

don’t know what it is. There’s no education. None of us know how to implement it.”

35

https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/finance/patient-advocacy-leads-north-carolina-hospital-to-post-

charity-care-application-online.html

36

One source recounted that an HCA employee told them: “There have been several versions of the policy; people

don’t know what it is. There’s no education. None of us know how to implement it.”

37

For instance, one clinician said that the magic word needed to reconsider an initial refusal was to request an

“escalation.”

38

https://www.citizen-times.com/story/news/local/2020/05/24/hca-missions-charity-care-letter-stein-has-info-

asheville-wnc/3107646001/

https://www.independentmonitormhs.com/_files/ugd/9da497_2d9f430241b7453b8160b1ff7a7ddfec.pdf

WORKING DRAFT – SUBJECT TO CHANGE – WORKING DRAFT

11 Wake Forest University, Health Law & Policy Program

to just “cross your fingers and wait for Medicaid expansion,” but in the meantime, “I’ll just manage the

symptoms as best I can.” Another says he and colleagues “have have resorted to using the ER to get

our patients the care they need for things that could have been managed [outside] the ER.” Yet

another, who said they still have not been able to get one of their patients qualified under HCA, instead

sends their patients who need charity care to other institutions.

Other sources noted that diverting charity care to other hospitals is thought to be a common HCA strategy.

Elsewhere, HCA hospitals usually are near enough to other hospitals that erecting charity care barriers

does not create as much of a problem or draw as much attention. Mission, however, was said to be

distinctive because it is “a prepackaged monopoly.” In western NC, other hospitals often are too far away

or do not offer the necessary service. That is why one source said this change in charity policy has been

“so devastating to our community.”

At HCA Mission the only workable way to obtain “necessary medical care regardless of the ability to pay”

(as specified in the Asset Purchase Agreement and as promised in its 2011 Certificate of Need application)

appears to be through the emergency room. Reflecting that reality, multiple sources noted that, to receive

charity care, patients effectively have to, as one put it, “wait until the issue flares up enough to go to the

emergency room.” In the emergency department, all care is presumed, at least initially, to be emergent,

and federal law requires at least stabilizing care regardless of the ability to pay. Patients will still be billed

for this care, but once they receive a bill they can then apply for charity write-off, which usually is a lengthy

and cumbersome process.

This pathway for charity care can meet a limited set of needs – mainly for unexpected medical

emergencies – but this narrow pathway does not reasonably accommodate those who need to arrange in

advance for care, even for very critical care. Sources explained that, in effect, in such predicaments

western North Carolinians are best advised to go unannounced to Mission’s emergency room (ER). As

discussed [in a forthcoming section], however, its ER is often chaotic and massively overcrowded,

requiring patients to suffer through delays extending many hours and sometimes days. Due to wanting to

avoid that ER experience if at all possible, physicians interviewed said that many people who need charity

care simply wait until their condition worsens, to the point that it truly is an emergency.

CONFUSING REPORTS OF FINANCIAL ASSISTANCE AMOUNTS

Considering the significant substantive limitations and administrative hurdles described so far, one would

expect HCA to report providing much less charity care than Mission previously did, but that is not

consistently the case. On the one hand, the earlier discussion shows (in Figure 1) that there has been a

substantial, and in some respects precipitous, drop in charity care services.

39

Equivalent drops are not

seen, however, when measured in reported dollar value rather than in numbers of patients. Using data

Mission submits each year to the federal government, HCA claims that Mission Hospital now provides

substantially more financial assistance than prior to the purchase, amounting to $300 million a year.

That sum vastly overstates the true value, however, because it is based on discounts from list-price

charges. Mission, like most hospitals, sets its list-price charges many multiples higher than its costs, and

39

This sharp drop is also confirmed by a certificate of need application HCA Mission filed with the state in 2019, in

which it reported that the proportion of hospital services for charity patients (measured by gross revenues)

dropped in half (from 3.1% to 1.4%) between 2018 and 2019.

WORKING DRAFT – SUBJECT TO CHANGE – WORKING DRAFT

Wake Forest University, Health Law & Policy Program 12

many multiples higher than it typically receives in actual payments. In fact, almost no patient actually pays

full charges (other than for fairly miniscule bills). Accordingly, the standard practice (endorsed by the

American Hospital Association) is to report charity care in terms of hospital costs rather than charges that

are discounted or written-off.

40

Measured in terms of costs, though, HCA Mission still appears to be doing well. For the five years prior to

the purchase (2014-2018), Mission reported that 3.3% of its total patient care costs counted as charity

care. For the first four years following the sale (2019-2022), HCA reported that this figure increased to

4.3%. That report poses a puzzling discrepancy between the drop in units of charity care service

documented above and the increase in dollar value of financial assistance. Understanding that

discrepancy requires a more nuanced understanding of what constitutes charity care versus other forms

of financial assistance.

Multiple Forms of “Financial Assistance”

Hospitals classify uncollected charges as either charity, bad debt, or general “uncompensated care.”

Reflecting these differences, Mission has not just one financial assistance policy, but four.

41

Mission’s

classic charity care policy, which can write off charges entirely, applies to patients up to twice the poverty

level. Its “expanded” charity care policy, which applies to patients up to four times poverty (essentially

middle class), charges patients but caps charges for any given episode of care at 3-to-4 percent of

household income.

42

Mission also has a “liability protection” plan, which it does not appear to regard as a “charity” policy.

Liability protection offers discounts (of unstated size) to people even with insurance if they incur a large

bill that insurance does not cover. Mission has not made details of this plan publicly available,

43

but it

states that it applies to households up to 10 times the poverty level (which would be upper middle class).

Finally, Mission has an “uninsured discount policy,” which applies without regard to income. For people

who pay out of pocket (i.e., without using insurance), this policy simply discounts charges by a remarkable

83 percent on average, but only if patients pay in full at the time of treatment (or commit to a monthly

payment plan). Essentially, then, this is a prompt pay discount. As such, it is simply a pricing policy rather

than a financial assistance policy. The eye-catching size of this discount reflects the extent to which HCA

routinely marks up list-price charges over amounts it actually expects to collect from most patients.

These multiple layers of possible financial assistance make it difficult to draw apples-to-apples

comparisons between pre-HCA Mission versus Mission under HCA. Stated another way, these multiple

policies make it more likely that any such comparison is more apples-with-oranges.

An example of this inherent slipperiness is HCA’s April 2020 response to the Attorney General’s official

inquiry about charity care. Prompted by widespread complaints about changes in HCA’s charity care policy

40

https://www.aha.org/fact-sheets/2020-01-06-fact-sheet-uncompensated-hospital-care-cost

41

https://missionhealth.org/financial-services/financial-support/

42

Apparently, patients are required to pay up to that amount for each treatment episode, even if there are several

in a row.

43

In response to the Attorney General’s request, Mission provided HCA’s liability protection plan for ambulatory

surgery centers rather than for its hospital. https://avlwatchdog.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Mission-

charity-care-responses-3.pdf. For people with bills over $10,000, that policy offers discounts ranging from 50

percent down to 20 percent for households up to five times poverty.

WORKING DRAFT – SUBJECT TO CHANGE – WORKING DRAFT

13 Wake Forest University, Health Law & Policy Program

and practice, the Attorney General asked Mission for “utilization rates for financial assistance policies”

before and after HCA’s acquisition.

44

HCA Mission responded that, for the 12 months prior to HCA,

“Mission Health provided financial assistance to 72,741 patients under the legacy Mission Health charity

care policy” (emphasis added).

45

HCA then stated that, in comparison, in the 12 months following its

acquisition “HCA provided financial assistance to 92,652 patients under its current financial assistance

programs, including the Charity Care Policy, Uninsured Discount Program and the [Liability Protection]

Program ....” In other words, HCA expressly (but subtly, without the emphases shown) compared pre-

purchase “apples” with post-purchase “oranges.”

HCA gave no indication of how much of the purported increase in financial assistance was due to inclusion

of the additional, non-charitable, programs. Also, although HCA presumably had the relevant data, it did

not include in the pre-HCA assistance count any of the patients Mission previously assisted under its

similar discount and liability protection programs. In other words, HCA ducked, and appears to have

obfuscated, this aspect of the Attorney General’s direct request for a clean before-and-after comparison.

46

Charity Care vs Uncompensated Care

Understanding these distinctions helps to reveal one key way that HCA has been able to show increased

charity care: As shown below, HCA has shifted more of the care that is uncompensated to “charity care”

status. These exhibits show changes in reported costs of charity care, as well as costs for other forms of

uncompensated care, using data Mission submits each year to the federal government.

47

To maintain consistency in how these data are reported, and to average out some yearly variations, this

comparison aggregates the five years prior to HCA’s acquisition, and the first four years under HCA.

48

TABLE 1. Changes in Costs of Charity Care and Uncompensated Care Following HCA’s Acquisition

Charity as % of

Total Care Costs

Uncomp. Care as %

of Total Care

Charity as % of

Uncomp. Care

Prior to HCA

(2014-2018)

3.3%

5.1%

65%

Under HCA

(2019-2022)

4.3%

5.1%

88%

Comparing those before-and-after time spans, Mission reported that an identical 5.1 percent of total

patient care was uncompensated. However, a greater proportion of that uncompensated care was charity

44

https://www.independentmonitormhs.com/_files/ugd/9da497_2d9f430241b7453b8160b1ff7a7ddfec.pdf

45

https://avlwatchdog.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Mission-charity-care-responses-3.pdf

46

HCA’s response was similarly mismatched for the dollar value of financial assistance. For pre-HCA, Mission

reported only charity care amounts. But, for post-HCA, it primarily reported all of its financial assistance programs

combined. It did, however, break out the separate amounts in a footnote, such that it was possible, with some

careful study, to make at least a partial apples-to-apples charity comparison (but based only on list-price charges

rather than on costs).

47

https://www.cms.gov/data-research/statistics-trends-and-reports/cost-reports/hospital-2552-2010-form

https://tool.nashp.org/

48

Due to differences in calendar year versus fiscal year reporting, the pre-HCA period is 5.3 years, compared with

3.7 years post-HCA.

WORKING DRAFT – SUBJECT TO CHANGE – WORKING DRAFT

Wake Forest University, Health Law & Policy Program 14

care under HCA, however, than was the case before HCA took over.

49

Prior to HCA, 35 percent of Mission’s

uncompensated care was not charitable whereas HCA reports that only 12 percent has been non-

charitable.

50

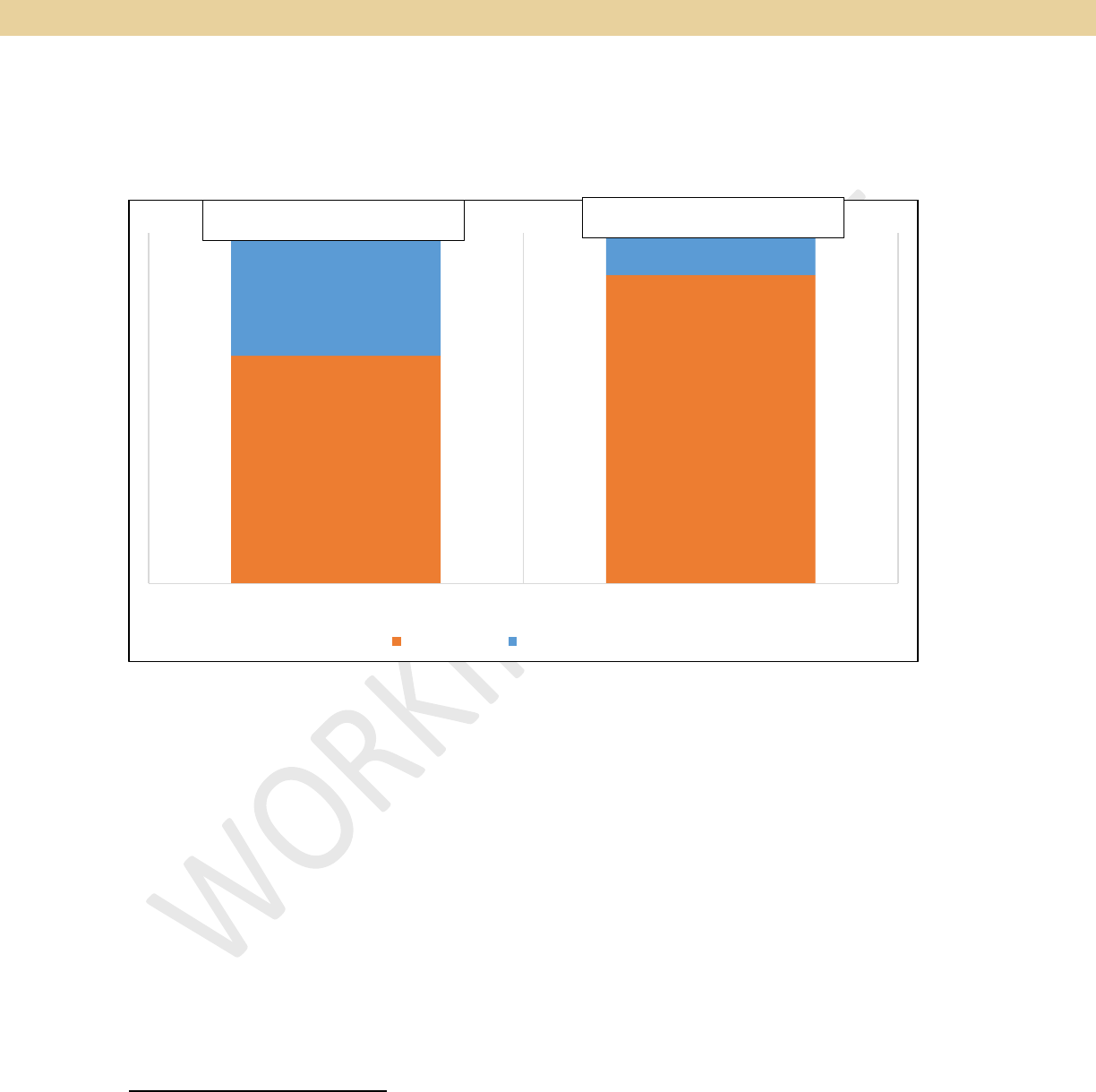

Figure 3: Reported Uncompensated Care Costs Before and After HCA Acquisition

This sizeable shift in distribution between charitable and non-charitable uncompensated care occurred

immediately upon HCA’s acquisition. Prior to the sale, Mission reported that about half of its

uncompensated care was charitable, in both the 4 months pre-sale and in the year prior to that. But, the

charitable proportion Mission reported shot up to almost 90 percent in the immediate 8 months following

HCA’s acquisition. The shift’s size and suddenness indicates this was an accounting change rather than a

change in actual composition of patients being served.

This pattern, coupled with problems discussed above in coverage and administration of Mission’s financial

assistance policies, strongly suggests that Mission has not in fact increased service to low-income patients

without adequate insurance. Measured by federal data on financial value, such service appears to be at a

similar level under HCA as before. In effect, Mission’s revised financial assistance policies have shifted

reporting of much uncompensated care from bad debt to reported charity, despite the fact, discussed

above, that much of this service may not in fact be offered regardless of a patient’s ability to pay.

In contrast, measured by state data (Figure 1), charitable service has dropped noticeably under HCA. It is

not at all clear why these two different indicators differ. Possibly, the two different reporting systems

49

A similar pattern can also be seen in the state’s service-quantity data, reported above, which show a much

greater drop in service to uninsured patients in outpatient clinics than for hospital patients.

50

Similarly, in its 2022 application to the state for a certificate need to add 67 hospital beds, HCA Mission

projected that it would provide over five times more in charity care than it would write off in bad debt (measured

by charges). Stated another way, HCA Mission projected that 85 percent of its total uncompensated care would be

in the form of charity care.

Charity Care, 65%

Charity Care, 88%

Other

Uncompensated, 35%

Other

Uncompensated, 12%

PRI OR T O HC A (2014 -2018) UNDER HC A (2019 -2022)

Charity Care Other Uncompensated

Total Uncompensated Care

Total Uncompensated Care

WORKING DRAFT – SUBJECT TO CHANGE – WORKING DRAFT

15 Wake Forest University, Health Law & Policy Program

have different criteria for classifying charity. It is also possible that some of HCA’s reported amounts are

not fully accurate.

51

As an example of one or the other of these two possibilities: In a 2019 “certificate of

need” application to the state to add 67 more beds, HCA Mission reported that the proportion of hospital

services for charity patients (measured by gross revenues) dropped in half (from 3.1% to 1.4%) between

2018 and 2019 – which is only about half the level it reported to the federal government. In any event, it

is clear that low-income uninsured patients do not have the same ability under HCA as they did previously

to receive non-emergency care regardless of the ability to pay.

SUMMING UP

During deliberations over the hospital’s sale, Mission’s Board became convinced that HCA’s charity care

policy is more generous than what Mission then had in place. Mission’s executives also assured the public

that HCA’s purchase would not diminish the hospital’s charity care commitment. Neither of these

representations turned out to be accurate.

These expectations were based on the appearance that, although HCA’s policy does not readily apply to

bills less than $1,500, HCA’s policy reaches higher incomes than did Mission’s previous policy. That

appearance, however, masks the reality that, in several ways, HCA constrains the availability of non-

emergency care regardless of the ability to pay. These constraints arise from both substantive limitations

in HCA’s policy and from barriers created by how the policy has been implemented. Primarily:

1. The policy does not apply to all medically necessary care, but instead only to treatment with such

urgency that it cannot be postponed.

2. HCA typically applies its policy only after eligible patients receive treatment, and HCA usually

requires eligible patients to pay a substantial deposit prior to treatment.

3. Various administrative barriers make it exceedingly difficult for qualified patients to obtain, and

maintain, a determination of eligibility on an ongoing basis, and the same barriers appear to

greatly hamper receiving charity care on an isolated, episodic basis.

It is curious, however, that available data does not consistently reflect these realities. Data from the state

in fact shows a substantial drop in patients treated on a charity basis. Data that HCA Mission reports to

the federal Medicare program, however, shows the opposite – that the value of charity care has increased.

A quite plausible explanation for this discrepancy is that HCA has changed how Mission classifies

uncompensated care. Rather than regarding many uncollected bills as bad debt, or regarding discounted

prices as normal market pricing decisions, HCA appears to use its generous-sounding financial assistance

policy to shift a good portion of these uncollected amounts over to the charitable side of its ledgers.

Regardless of whether, or to what extent, this somewhat speculative impression is accurate, it does

appear clear that, apart from its emergency room,

52

HCA Mission no longer treats a substantial number

of low-income patients as true charity cases, that is, regardless of their ability to pay and without an intent

to collect substantial payment.

51

One source who worked closely with a substantial number of low-income uninsured patients noted that, when

they asked HCA Mission for data about their provision of charity care, they “found lots of errors.”

52

And, even in the emergency setting, HCA appears to bill low-income uninsured patients for care without first

determining if they might be eligible for charity status.

WORKING DRAFT – SUBJECT TO CHANGE – WORKING DRAFT

Wake Forest University, Health Law & Policy Program 16

APPENDIX

Excerpts Addressing Charity Care from Transcripts of Community Meetings in 2020 Held by the

“Independent Monitor”

53

Prepayment Issues

I work [as a physician] at … a federally qualified health center, so we see people who are on a

sliding scale, … who have very little money. ... We used to be able to work with Mission. I mean

anything, you talk about a hospitalization that was tens of thousands of dollars to do a test that

was a few hundred dollars and they would get a discount that would make it affordable,

sometimes it would be basically free. I had a patient that very much needed a CT scan recently,

and fine, you get a discount, … $1,300 was going to be her portion of this discounted rate, 25%

of a CT scan. Now again, anyone who's been in medicine, a normal CT scan was not, I'm sorry,

what's the math, $5,000 before [HCA], that was not the normal cost of a CT scan before. And not

only that, she was humiliated when she went to get it. “Didn't they tell you that you were going

to need to pay this?” So, most people, myself included at times, are not going to be able to pull

$1,300 out of their bank account, especially somebody who's needing charity cares on a sliding

scale. So, this charity care is not happening, and if that was a service they were promising, it's not

effectively happening.

I'm actually a practice manager of a medical office here in town…. We call for stat CT, stat

ultrasounds, [it] takes 10 days if they're uninsured. They're asking patients, "Oh, do you have

$5,000 to pay upfront?" No, they don't. We are sending all of our services pretty much to [non-

Mission hospitals] for any of those outpatient radiology services just to avoid the hassle.

I worked for a primary care clinic in the area. We are a federally qualified health center, which

means that we see uninsured folks regardless of their ability to pay …. We were informed that

[charity] care would remain accessible through the Mission Health System. So prior to the HCA

transition, if we referred a patient to any Mission associated facility and they were under 200%

of the federal poverty guideline as well as several other things, they could have their services

covered at 100% of costs, which meant if I sent someone to Mission Neurology … for a specialist

consult, that could then be applied for the charity care program to have that covered. After HCA,

that slowly got it phased out and now our patients are required to pay 20% of the cost of every

visit upfront. Now when you serve a population that is uninsured and is earning low to no income,

often these can be $100 to $200 for a specialist visit which means we have resorted to using the

ER to get our patients the care they need for things that could have been managed [outside] the

ER. It could be as simple as we see someone for suspected pneumonia and we want an X Ray but

now we can't send them to Mission Imaging, because Mission Imaging is going to ask them for

$120 before they even provide the procedure. We have to send them to the ER, which clogs up

the ER and prevents people with actual urgent care need from getting the care they need

53

https://www.independentmonitormhs.com/archive-1.

WORKING DRAFT – SUBJECT TO CHANGE – WORKING DRAFT

17 Wake Forest University, Health Law & Policy Program

My wife and I own a small business. We're homeowners, we're not chronic deadbeats, we simply

were priced out of the healthcare market in 2010. So, we had to turn to Mission and the charity

care they were providing. Now, they said nothing was going to change and that is not our

experience. … I had gone to the doctor, she wanted me to go over to the hospital to have a test.

The scheduler called me up and asked me for $200 upfront that I had to pay right then, which I

did not have. I explained to her we had been on charity care and she said that was no longer an

option. I had to come up with $200. Then she looked and said okay since you don't have

insurance, I could cut it down to around $100. Same problem, I don't have $100 [so] I can't do

charity care. I had to go around for three months with the people, the caseworkers to help me

out. I was told they no longer have charity care to help me with. So now it's been six months, I

didn't have that test taken, so I guess I'm out of luck. What am I going to do? If there's something

wrong, I [won't] know about it. It seems to be nowhere else for me to turn. … When HCA took it

over, everything [about charity care] changed. The caseworkers told me there's no charity care.

The people, the scheduler for Mission said that there was no charity care. That's the message

they gave me. So, I do not know where to turn to. … The reason they're saying [the CC policy] is

better, it used to be I think 200% of the poverty level. Now it's 400%. Well, that is better but it's

not if you don't have the hundred dollars or whatever you need to do it, it's nonexistent.

Administration Issues

[From a low-income primary care clinic]: When you have someone who doesn't have an address

or is constantly moving around or people that are unstably housed and being kicked out of where

they're being housed, they can often miss the deadline for this paperwork and then they're

deferred for six months from reapplying. Which means, if we want a diabetic with early stage

kidney disease to see a nephrologist and they get denied for this program, we have to wait six

months to send them, at which point they get worse, and maybe they get so worse at that point

we have to send them to the ER for further care. So, … I really wish someone would look into this

charity care program because it has made primary care very difficult to do for a really vulnerable

population.

[Before HCA’s purchase,] we were fortunate to have [help] from Mission financial assistance. …

[W]e were lucky enough to … [have] up to 70% discount on any bill. And if I remember correctly,

it was a piece of cake to get it. You had to fill out a few papers, so forth, but it wasn't a big deal.

But since HCA's taken [over] as a profit outfit, why would they make it easy for a person to get

financial assistance when they can make it hard for them. … [I was] assured that HCA was going

to keep financial assistance. Well, they kept it all right. They keep it in their pocket. It doesn't

take a rocket scientist to figure out if they make it hard enough, the people aren't going to get it,

and they'd make more money. Real simple. I'd rather die in peace. I understand. But I think it's a

terrible, terrible thing. … I used to wave a flag for Mission, but now I've got to jump through seven

hoops and wonder, "Am I going to be lucky or not?" …. So … my main thing is that from nothing

to seven hoops to get financial assistance, it's criminal. It is, pardon my French, damn criminal.

I have been involved with the charity care [policy as a patient]. … Five times [in 2019 I] called the

office, the numbers. They told me that during the transition, it is no longer the way it used to be

WORKING DRAFT – SUBJECT TO CHANGE – WORKING DRAFT

Wake Forest University, Health Law & Policy Program 18

where all the bills are under just your name. You have to do each one individual. I was also told

that it takes up to six months for them to get the information from [Blue Cross] ... even though I

already got it, the information of what they paid. Then, they would mail it to me. The first three

phone calls I had made to them, they had the wrong address. I had it corrected for three times,

but that's not why I didn't get it. Finally, they told me they’re way behind with all this transition.

Just wait six months. Okay. I've been waiting six months. In the meantime, I had to have x-rays

and MRIs and a doctor to look over all that. I have $6700 deductible that I am now getting

collection people [telling] me that I owe this money, and charity care just wants me to sit around

and wait for them to mail me a form. They had to fill out one for each bill when they finally hear

from Blue Cross. This all started last year in the spring. I've got not one [form] from them. Not

one. I don't call them anymore. I just don't know what to do.

General

I've worked for Mission Hospitals for eight years at Mission …. I'm a behavioral health specialist.

I've always been very proud of the charity care program that Mission provided. It was amazing.

People in the ICU going home with no insurance and not having their lives taken away from them

for the bills. It covered so many people. Practically I was being covered as a behavioral health

person under charity care for many of my patients. When HCA took over, … [t]hey will get a 20%

discount on $150 bill if they see me. And these are people who are uninsured, fall in that gap of

the Medicaid expansion and have no insurance and then they end up … inpatient if they're not

getting care. And so, I just want to say that I have seen that change.