Health and Care Act 2022

Impact assessments summary document and analysis

of additional measures

Published 4 November 2022

2

Contents

1. Introduction ................................................................................................................... 3

2. Policies .......................................................................................................................... 4

3. Interactions between policies ........................................................................................ 6

4. Specific Impact Tests .................................................................................................... 7

5. Post Implementation Review (PIR) ............................................................................... 9

6. Impact assessments of additional measures ............................................................... 10

7. Annex A: Licensing of non-surgical cosmetic procedures: Illustrative examples ......... 69

8. Annex B: Initial assessment of impact and costs for a cosmetic licensing scheme ..... 71

9. Glossary ...................................................................................................................... 76

3

1. Introduction

The Health and Care Act 2022 builds on the proposals brought forward by the NHS following the

publication of the Long-Term Plan. These proposals built on extensive engagement by the NHS

in 2019 and were further developed in the 2021 White Paper Integration and Innovation:

Working Together to Improve Health and Social Care for All. The Act advances on the

collaborative working seen throughout the pandemic, to shape a system which is best placed to

serve the needs of the population.

The core measures in the Act follow three core themes, all of which are integral for helping the

system to recover from the pandemic and transform patient care for decades to come.

Firstly, the Act removes barriers which stop the system from being truly integrated, with different

parts of the NHS working better together, alongside local government, to tackle the nation’s

health inequalities.

Secondly, the Act reduces bureaucracy across the system. DHSC wants to remove barriers

which make sensible decision-making harder and distracts staff from delivering what matters –

the best possible care.

Lastly, DHSC wants to ensure appropriate accountability arrangements are in place so that the

health and care system can be more responsive to both staff and the people who use it.

All of these measures are intended to complement, not distract from, the transformation that is

already taking place across the system. These policies should be seen in the context of those

broader reforms.

Alongside the core measures, there are additional policies to make targeted changes to allow

the government to support the social care system, to improve quality and safety in the NHS, to

grant the flexibility to take public health measures and to implement worldwide reciprocal

healthcare agreements.

These measures will provide a foundation to build upon and our aim is to use legislation to

provide a supportive framework for health and care organisations to continue to pursue

integrated care for service users and taxpayers in a pragmatic manner.

As the health and care system further emerges from the pandemic, these legislative measures

will assist with recovery by bringing organisations together, removing more of the bureaucratic

and legislative barriers between them and enabling the changes and innovations they need to

make.

4

2. Policies

The Health and Care Act legislates for multiple policy objectives and therefore brings forward a

number of different measures. All of the policies where costs and benefits have been identified

have an impact assessment (IA) which discusses the options, rationale, costs and benefits in

detail.

Several of the policies relate to enabling powers in the Act which do not have quantifiable

benefits or costs, as the impact of the policy will ultimately depend upon how the powers are

used. Nevertheless, a qualitative assessment of the potential costs, benefits, risks and

mitigations have been included as part of this package of IAs.

Furthermore, given that there are multiple policies, several of which do not have quantifiable

benefits, it was not deemed appropriate to calculate an overall Net Present Value for the relative

costs and benefits across the entirety of the Act. Rather, if costs and benefits have been

quantified, then an NPV will be included in that policies respective IA and will be considered in

isolation.

Table 1 presents a summary of the IAs published alongside the Act and the individual IA title in

which they have been incorporated. Policies on Health Services Safety Investigations Body

(HSSIB), and, introducing a 2100-0530 watershed on TV and online ban for paid advertising of

food and drink that are High in Fat, Salt and Sugar (HFSS) products, each have their own

standalone document dedicated to that respective policy.

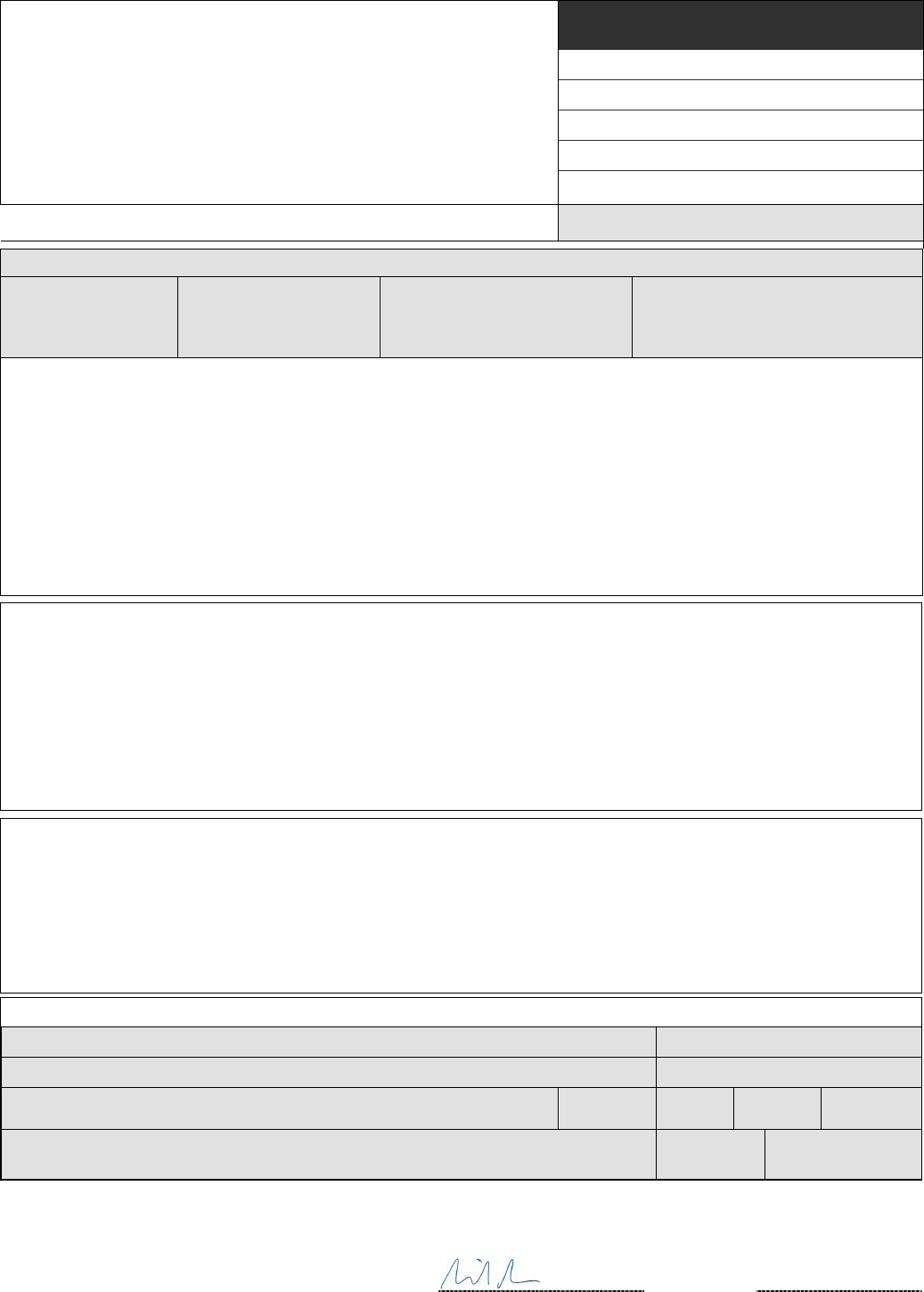

Table 1: Summary of policies and where to find their associated IAs

Policy

Impact assessment

Commercial dealings in organs for transplantation: extra-territorial

offences

Additional measures IA

Eradicating slavery and human trafficking in supply chains

Additional measures IA

Food information for consumers: power to amend retained EU Law

Additional measures IA

Hospital Food Standards

Additional measures IA

Increasing gamete and embryo storage limits to a maximum of 55 years

for all

Additional measures IA

Information about payments to persons in the health care sector,

enforcement and consent

Additional measures IA

Licensing of cosmetic procedures

Additional measures IA

Medical examiners

Additional measures IA

Medicines information systems

Additional measures IA

Powers allowing further products to be centrally stocked and supplied

free of charge to community pharmacies without the need to reimburse

them under the standard NHS arrangements

Additional measures IA

Professional regulation

Additional measures IA

Rest of World reciprocal healthcare

Additional measures IA

Water fluoridation

Additional measures IA

Abolishing Local Education Training Boards

Core IA

Accountability and Transparency of Mental Health Spending

Core IA

NHS England mandate: cancer outcome targets

Core IA

Arm’s-Length Bodies transfer of functions power

Core IA

Care Quality Commission reviews of Integrated Care Systems

Core IA

5

Climate change duties

Core IA

Competition

Core IA

Data sharing

Core IA

Designating Integrated Care Boards as Operators of Essential Services

under NIS Regulation

Core IA

Duty to cooperate

Core IA

Establishing Integrated Care Boards and Integrated Care Partnerships in

law

Core IA

Foundation Trusts capital spend limit

Core IA

Further embedding research in the NHS

Core IA

General power to direct NHS England

Core IA

ICB and NHSE inequalities duty extension

Core IA

Information about inequalities

Core IA

Joint Committees, Collaborative Commissioning and Joint Appointments

Core IA

Merging NHS England and NHS Improvement

Core IA

National Tariff

Core IA

New trusts

Core IA

Provider selection and Choice

Core IA

Public Health power of direction

Core IA

Reconfiguration of services: intervention powers

Core IA

Special Health Authorities Time Limits

Core IA

NHS England Mandate: general (and Better Care Fund)

Core IA

Triple Aim

Core IA

Workforce accountability

Core IA

Adult social care – assurance

Social Care IA

Adult social care – discharge to assess

Social Care IA

Adult social care – provider payments

Social Care IA

Policies with standalone IAs

Virginity Testing Ban

Health Services Safety Investigations Body (HSSIB)

Introducing a 2100-0530 watershed on TV and online ban for paid advertising of food and drink that

are High in Fat, Salt and Sugar (HFSS) products

Hymenoplasty Ban

There are several policies in the Act which include a requirement to consult, to undertake a

review or to produce a report. These policies are: Child safeguarding etc in health and care:

policy about information sharing, and; Review into disputes relating to treatment of critically ill

children. For these policies an impact assessment has not been included as the impact of the

policy will depend upon the outcome of the consultation, its recommendations, and whether or

how they are acted upon, or any commitments to action in the report. An impact assessment will

be undertaken following consultation/publication as appropriate.

Impact assessments on the policies regarding early medical termination of pregnancy and

mandatory training on learning disability and autism are in development and will be published in

due course.

6

3. Interactions between policies

The policies covered in the Act should be seen as mutually reinforcing, rather than policies to be

viewed in isolation. Therefore, there are interdependencies between the Act provisions,

whereby the success of one policy may depend on the impact of another. This is particularly

true of provisions relating to the three principles underlying the Act, which are being put in place

to foster collaboration across the health and care system and are covered in the Core IA.

Potential interdependencies are outlined below, although this list is not exhaustive and further

details can be found in the specific analyses for each policy.

The Triple Aim and Duty to Cooperate provisions make it more likely that other policies covered

in the Act will have a system benefit (e.g. appropriate joint working with ICBs and their system

partners). The benefits derived from these policies will depend on the success of other

measures to deliver beneficial system change. Further detail can be found in the respective

sections in the Core IA.

The Professional Regulation provisions have potential interdependencies with the ALB transfer

function policy, and, with other existing policies related to health and social care. This is

explored in more detail in the Professional Regulation section of the Additional Measures IA.

For the public health measures related to obesity, namely those concerning the advertising of

HFSS foods and Food information for consumers: power to amend retained EU Law, the impact

of these policies on public health may be difficult to disaggregate as they are part of a wider

programme of supporting the public to make better informed choices about their diet.

7

4. Specific Impact Tests

In some cases, the policies included within the Health and Care Act introduce enabling powers,

and so the impacts will not materialise until secondary legislation is finalised and implemented.

Therefore, at secondary legislation stage, more detailed analysis of the finalised policy will be

undertaken, which will also include detailed analysis of specific impacts, such as those on the

justice system, trade and the environment where appropriate.

Equality

The policy measures in the accompanying IAs have undergone a equalities assessments as

appropriate.

Privacy

The powers that enable data to be required from adult social care providers may have an

impact on privacy depending on the form of data required. Any requests that relate to

identifiable information will be subject to existing data protection legislation and individual

privacy tests will be undertaken as appropriate. Similarly, the power to extend NHS Digital’s

(NHSD) powers to enable it to require data from private providers may also have an impact on

privacy and NHSD will ensure that appropriate safeguards are in place.

Justice system

Justice impacts are anticipated for the HSSIB, Medicines Information Systems, Organ

Transplantation, Virginity Testing, Hymenoplasty, Information about payments, Licensing of

Cosmetic Procedures Eradicating slavery and human trafficking in supply chains and

Commercial dealings in organs for transplantation: extra territorial-offenses.

Restrictions on HFSS advertising may result in some enforcement actions reaching the courts,

although this number is expected to be very small.

New burdens for local government

No new burdens on local authorities are anticipated at this stage from the primary legislation.

However, this will be under review as the Government continues to implement these policies

through guidance and secondary legislation. We expect to produce a new burdens assessment

for the Adult Social Care Assurance policies but will continue to keep other areas of the Act

under review.

Competition and innovation

The policy in the Core IA relating to competition intends to change the roles in respect of

competition of the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) and NHS Improvement (Monitor

functions). The policy aims to create a more nuanced approach to certain NHS transactions that

gives greater weight to collaboration. The potential impacts of this on competition are outlined in

the Core IA.

8

The policies relating to provider selection and choice, licensing of cosmetic procedures and

eradicating slavery and human trafficking in supply chains may have impacts on competition at

secondary legislation stage. This will be explored as part of an impact assessment as

appropriate at that point.

Restrictions on HFSS advertising may result in impacts on competition and innovation, which

are explored in this policies standalone IA.

Small and micro business assessment (SaMBA)

The policies related to data sharing, provider selection and choice, medicines information

systems, Licensing of Cosmetic Procedures, information about payments, hospital food

standards, Food information for consumers: power to amend retained EU Law and reciprocal

healthcare arrangements for rest of world countries may have impacts on small or micro

businesses. It is not possible to provide a robust estimate of these costs, or give details of

exemptions, until the relevant powers are used. There is a commitment to examining these

impacts if and when secondary legislation is introduced. Further details are given in the

respective IA sections.

9

5. Post Implementation Review (PIR)

The PIR of the Health and Care Act 2022 is currently being commissioned through an NIHR

Policy Research Programme open-call. DHSC have invited proposals for a single primary

research project to provide evidence on the implementation and impact of the Act.

The primary interest of the PIR is to understand the different ways that Integrated Care Boards

and Integrated Care Partnerships, and system partners (at system, place, and neighbourhood

level) are coming together to design, commission and deliver services, and fulfil their duties,

and the potential impacts. The aim is to capture learning to identify how positive changes may

have been achieved, the obstacles to this (and how these can be avoided), and to disseminate

that learning across the system.

This evaluation will help to spread learning in a timely manner (e.g., learn and disseminate what

works in delivering quality integrated care and support). It will also support Ministers and

policymakers understand how the system is evolving following the legislative changes, how

DHSC can best support ICBs and ICPs in delivering better outcomes and inform future reforms

regarding integrated care.

This evaluation will be a mixed methods and multi-phased study, taking around 2-3 years to

complete. However, research outputs will be produced and shared before completion to be

disseminated with systems, facilitating the sharing of lessons learnt and best practice with

systems.

The PIR will be focused on the policies most directly related to the core themes of the Act of

increasing collaboration, reducing unnecessary bureaucracy and accountability. Policies outside

of this core focus will develop their own PIR plans as appropriate. For example, PIR plans

would be developed if it were decided to exercise particular powers described in the core IA and

additional measures IA. This is because for provisions which include enabling powers, the

details of the final policy will not be finalised until the implementation or secondary legislation

stage. This means that the specific plans for the PIR cannot be finalised until the final form of

the policy, and the specific outcomes it is likely to affect, are known.

Some policies which have standalone IAs, such as the provisions concerning advertising of

foods and drinks which are High in Fat, Salt and Sugar (HFSS), have committed to completing a

PIR. Details of PIR plans are outlined in these standalone IAs.

10

6. Impact assessments of additional

measures

The proceeding section is the impact assessment for several additional policies to support

public health, and quality and safety.

11

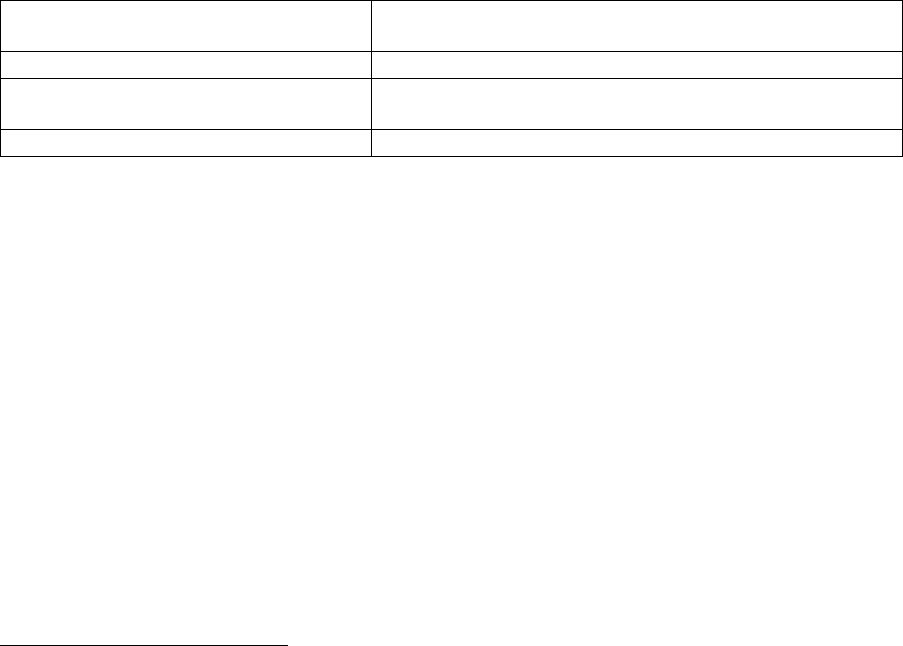

Title: Health and Care Act 2022

IA No: 9570

RPC Reference No: RPC-DHSC-5082(1)

Lead department or agency:

Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC)

Other departments or agencies:

NHS England and NHS Improvement

Impact Assessment (IA)

Date: 27/10/2022

Stage: Final

Source of intervention: Domestic

Type of measure: Primary legislation

Contact for enquiries: Not applicable

Summary: Intervention and Options

RPC Opinion: GREEN

Cost of Preferred (or more likely) Option (in 2019 prices)

Total Net Present

Social Value

Business Net Present

Value

Net cost to business per

year

Business Impact Target Status

Non qualifying provision

Unquantified Unquantified Unquantified

What is the problem under consideration? Why is government action or intervention necessary?

Demographic and social changes have, for a number of years, been changing the shape of the demands on the health

and care system. This Act implements the lessons learned from the evolution of the entire Health and Care System, as

well as the specific experience of responding to an unprecedented public health emergency during the Covid-19

pandemic. The measures considered in this impact assessment are targeted to address specific problems and remove

legislative barriers to allow front line staff and the government to deliver care more efficiently and maximise opportunities

for improvement. This is with the ultimate of aim of supporting the system in helping people to live healthier, more

independent lives for longer.

What are the policy objectives of the action or intervention and the intended effects?

Measures considered in this impact assessment relate most directly to the fourth principle of the Health and Care Act,

which have the aims of supporting social care, public health, and quality and safety. For example, the policies examined

in this impact assessment are targeted changes which will enable government to more effectively support the social care

system, and, implement comprehensive reciprocal healthcare arrangements with Rest of World countries (outside the

European Economic Area and Switzerland). The impact assessments for seven policies relating to the fourth principle

have been collated in this single document as they all entail small or unquantifiable impacts.

What policy options have been considered, including any alternatives to regulation? Please justify preferred

option (further details in Evidence Base)

This IA covers legislative changes developed by the Department of Health and Social Care, working with a breadth of

stakeholders including NHS England & NHS Improvement, and the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and

Communities. Given the complexity of the package of measures, this IA is focussed primarily on the leading options for

each of the policies and specific legislative changes. Impacts are by default compared against a ‘do-nothing’ option,

although in some cases alternative policy options are outlined.

Will the policy be reviewed? It will be reviewed.

If applicable, set review date: Not applicable

Does implementation go beyond minimum EU requirements? N/A

Is this measure likely to impact on international trade and investment? No

Are any of these organisations in scope?

Micro

Yes

Small

Yes

Medium

Yes

Large

Yes

What is the CO

2

equivalent change in greenhouse gas emissions?

(Million tonnes CO

2

equivalent)

Traded:

N/A

Non-traded:

N/A

I have read the Impact Assessment and I am satisfied that, given the available evidence, it represents a

reasonable view of the likely costs, benefits and impact of the leading options.

Signed by the responsible Minister:

Date:

27/10/2022

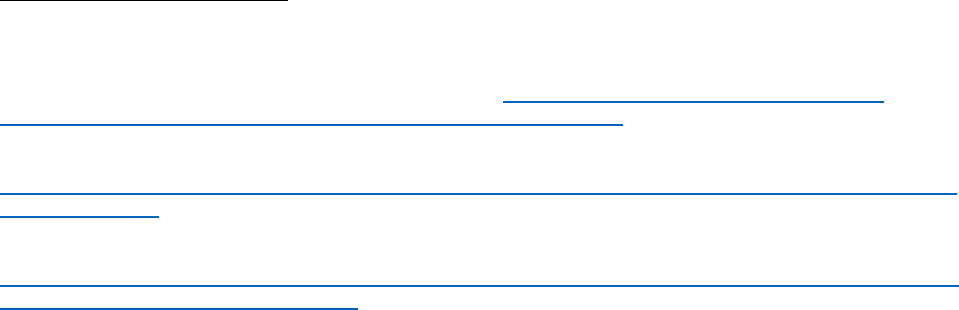

Summary: Analysis & Evidence Policy Option 1

12

Description:

FULL ECONOMIC ASSESSMENT

Price Base

Year N/A

PV Base

Year N/A

Time Period

Years N/A

Net Benefit (Present Value (PV)) (£m)

Low:

N/A

High:

N/A

Best Estimate:

N/A

COSTS (£m)

Total Transition

(Constant Price) Years

Average Annual

(excl. Transition) (Constant Price)

Total Cost

(Present Value)

Low

High

Best Estimate

N/A

N/A

N/A

Description and scale of key monetised costs by ‘main affected groups’

The policies set out in this IA are complex and to a significant extent consist of creating enabling powers which either lead to

practical but limited changes; require secondary legislation or consultation before practical changes can occur; and/or, require

system behavioural change before practical changes come into force. It is not possible to robustly estimate an overall cost

impact by affected groups, but despite this, costs which may be incurred following secondary legislation have been outlined as

best as possible at this stage. The medicines information systems section contains an illustrative example of monetised

impacts if those enabling powers were used. An assessment of impacts on businesses, including small or micro businesses,

and wider impacts such as those on the environment, trade and competition, will be completed where appropriate alongside

secondary legislation.

Other key non-monetised costs by ‘main affected groups’

The policies set out in this IA affect NHS providers, commissioners and arms’ length bodies, as well as local authorities, social

care providers, and independent organisations providing health and care service. However, as many of these provisions

introduce enabling powers, any costs will depend upon how those powers are exercised. If secondary legislation were to be

enacted, then an assessment of costs will be completed at that point if appropriate.

BENEFITS (£m)

Total Transition

(Constant Price)

Years

Average Annual

(excl. Transition) (Constant Price)

Total Benefit

(Present Value)

Low

High

Best Estimate

N/A

N/A

N/A

Description and scale of key monetised benefits by ‘main affected groups’

Benefits relating to these policies have not been monetised in this IA as a robust estimation of likely effects is not possible. This

is because the likely effects of, for example, an enabling power will depend upon how those powers are exercised. If

secondary legislation were to be enacted, then an assessment of benefits will be completed at that point if appropriate.

Other key non-monetised benefits by ‘main affected groups’

It is not possible to monetise the benefits of enabling powers, as the specific circumstances under which those powers may be

exercised will influence the potential costs and benefits. If secondary legislation were to be enacted, then an assessment of

benefits will be completed at that point if appropriate. However, examples of potential benefits from the policies in this IA

include reduced bureaucracy, and therefore, reduced burden on policymakers and providers, improved service provision to

patients, and, more informed patients.

Key assumptions/sensitivities/risks Discount rate (%)

N/A

It is difficult to fully determine the impact of these provisions quantitatively. There is a risk associated with any change

programme, even if intended to be limited, that resources are spent on implementing a new system to the detriment of output.

A further risk is that some provisions are enabling measures and do not contain substantive provisions. It is therefore difficult to

assess with any certainty what the impact of the measures will be, as the detail of those final provisions is not currently

available. Any policy that will be implemented using the regulation-making powers provided in these provisions in future will be

required to develop an impact assessment as appropriate.

BUSINESS ASSESSMENT (Option 1)

Direct impact on business (Equivalent Annual) £m: Score for Business Impact Target (qualifying

provisions only) £m: Not a qualifying provision

Costs: N/A

Benefits: N/A

Net: N/A

13

Health and Care Act: Evidence base for impact assessment

Background and overview

The Health and Care Act builds on the experience of previous reforms of the health and care

system, as well as the specific experience of responding to an unprecedented public health

emergency in the Covid-19 pandemic.

The measures considered in this impact assessment are targeted to address specific problems

and remove legislative barriers to allow front line staff and the Government to deliver care more

efficiently and maximise opportunities for improvement.

They are not intended to address all the challenges faced by the health and social care system.

Instead, these measures are targeted changes to allow the Government to support the social care

system, improve quality and safety in the NHS, grant the flexibility to take further public health

measures and to implement worldwide comprehensive reciprocal healthcare agreements.

The Government is undertaking broader reforms to social care and public health which will support

the system in helping people to live healthier, more independent lives for longer. As with the core

provisions impact assessment, many measures covered in this impact assessment will introduce

enabling powers and will require further secondary legislation in order to implement the policy.

Scope of the additional measures impact assessment

There are three guiding themes running through the core policies in the Health and Care Act.

These are: working together and supporting integration; reducing bureaucracy; and ensuring

accountability and enhancing public confidence. Alongside the core measures, there are additional

policies to make targeted changes to allow the Government to improve quality and safety in the

NHS, to grant the flexibility to take public health measures and to implement worldwide

comprehensive reciprocal healthcare agreements.

The 13 policies considered in this impact assessment relate most directly to additional policies to

support public health, and quality and safety. The analyses have been collated in this single

document as they all entail small or unquantifiable impacts. Several other additional

policies, such

as those relating to social care, have standalone IAs due to the size of the potential impact or

because the complexity of the analysis warranted a separate document. Readers should refer to

the impact assessments summary document for direction on where to find analysis on the other

policies in the Health and Care Act.

Post Implementation Review (PIR)

The exact details of the PIR for the

policies analysed in this IA will be set out once the provisions

are used. Please refer to the Impact Assessment Summary Document for further justification.

Summary of the costs, benefits, risks and mitigations of each

policy

This section provides details of each of the proposed changes to support the health and care

system.

14

1. Medicine information systems

Policy summary

Medicines registries provide a valuable resource for assessing and monitoring the safety and

effectiveness of medicines. The Independent Medicines and Medical Devices Safety Review

1

(IMMDSR) in 2020 made specific recommendations on the need for a national antiepileptics

registry. Following this, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) is

seeking regulation making powers to enable NHS Digital to establish and operate UK-wide

medicines information systems in order to ensure that comprehensive national registries can be

established and built in a sustainable way. This will require powers to be conferred on NHS Digital

to enable them to mandate relevant data collection, including from private healthcare providers and

devolved administrations, to build one or more comprehensive medicine information system(s).

The intention is that the information included in these systems will then be made available to the

MHRA to enable it to establish and operate UK-wide registries using existing powers contained in

the Human Medicines Regulations 2012.

This policy

only creates the power to make regulations to establish medicine information systems.

As such while there is no direct cost or impact associated with the clauses in this Act,

consideration as to how the regulations are likely to be laid out and their potential impact through

an illustrative example is appropriate. A more detailed assessment of costs and impacts can be

conducted when the regulations are made and exercised to develop a specific registry.

It is anticipated that, when there exists a need justified on public health grounds, the MHRA will

assess the option of introducing a particular national medicines registry when alternative

approaches to capturing sufficient data are not feasible. The proposal for establishment for a new

registry will be presented to the Commission on Human Medicines (CHM) who would need to issue

a formal registry-specific recommendation subject to the following criteria:

i. There are known risks associated with a medicine that can result in serious adverse health

outcomes and where adherence to effective risk minimisation measures is critical to ensuring

the benefits associated with the medicine outweigh the risks

ii. There is uncertainty about the safety or effectiveness of a medicine in a population in whom

prescribing may occur that means that urgent evidence is required to build the evidence base

on the benefit risk balance and inform the need for, and feasibility of, risk minimisation

measures

The CHM’s final advice on the need for a specific registry will be put to the appropriate authorities

to propose issue of a joint direction for NHS Digital to collect the appropriate information required

by the registry to be captured within the medicine information system.

A core register of all patients prescribed the specific medicine of interest will form the basis of a

bespoke registry. The aim is to use patient-level data already collected within the NHS to form this

core register, which should facilitate complete monitoring of patients prescribed specific medicine

where necessary. Therefore, powers are also sought to ensure that individual patient-level data

can be linked across different national datasets, held by NHS Digital and the devolved

administrations, according to the design specification agreed by the Registry Steering Committee

for a specific registry. The MHRA will work with the NHS to build and maintain these registries.

Rationale for intervention

1

First Do No Harm The report of the Independent Medicines and Medical Devices Safety Review, (2020).

[Online]. Available from: https://www.immdsreview.org.uk/downloads/IMMDSReview_Web.pdf

15

At present, there are no government funded UK wide registries for products that pose potential

health risks to certain patients. Either when a license is first granted for a medicinal product to be

placed on the market, or at a later stage should the need be identified, the MHRA can require a

Marketing Authorisation Holder (MAH) to establish a registry for that specific medicine to, for

example, identify or monitor adverse effects. This is an existing legal power of the MHRA acting as

the UK national competent authority for the regulation of medicine. The requirement for a registry is

defined in the terms of the license granted to the MAH. MAH-led medicine registries have had

mixed success in generating the strength of evidence required to make fully robust regulatory

decisions regarding the safe and effective use of medicine. This is in part because such stand-

alone registries are voluntary for clinicians, and full identification of eligible patients is also often

challenging due to a hesitance on the behalf of clinicians and their patients to enrol as part of an

MAH-sponsored registry due to data confidentiality concerns. Enrolment may also be affected as

registries can place additional burden on healthcare providers (HCPs) to supply data.

Academic led initiatives also exist and have demonstrated the value that evidence generated by

high quality registries can have in supporting regulatory, HCPs, and patient decision making. The

MHRA are increasingly using data from these larger disease registries led by clinical and academic

research groups, although these often have issues with sustainability. In addition, voluntary

participation means data is not comprehensive or representative, rarely including data from private

providers and with regional and clinical speciality variations in terms of coverage. NHS Digital and

the devolved administrations already collate extensive data on the use of medicines in the UK but

there are gaps in this which need to be addressed.

The key justification for this policy is that it will facilitate a better monitoring system of the use,

benefits and risks of medicines, leading to improved evidence bases for regulatory and clinical

decision-making and overall patient safety outcomes. The provisions make this possible. A central

UK wide medicine information system, or systems, run by the NHS, filling existing data gaps and

linking data from different sources will enable the initiation of high-quality inclusive registries

operated independently of industry.

Other policy options considered

This IA only presents the option to introduce statutory powers to enable NHS Digital to establish a

medicines information system. This system will enable MHRA to set up a comprehensive UK wide

registry for a product when CHM considers the criteria for such a registry is met. The baseline

status quo option involves the MHRA setting up registries without a medicine information system –

either by requiring MAHs to set up voluntary registries or trying to develop UK wide registries

without powers to mandate data collection.

Option 0 - Business as usual (Do nothing)

In the counterfactual, the MHRA would continue using existing powers to set up registries but

without statutory medicine information systems to support them. This could be through the

licensing process where MAHs could be asked to set up and maintain registries for specific

products or, for example, as is the case with antiepileptics, a national registry is being set up to

address an urgent safety concern as recommended by the IMMDSR, but this is reliant upon

existing data feeds and voluntary provision of additional data. Currently, there are gaps in data

from prescriptions in private practice and from the devolved administrations as well as a lack of

detail on clinical aspects that are vital in order for the registry to meet its objectives. This option

was not deemed feasible because the lack of robust, objective and comprehensive evidence poses

high risks for patients. Without a robust and complete medicine information system building a

comprehensive medicine registry, including all patients prescribed that medicine, independent from

industry, which can be necessary if public confidence is to be maintained, gaps in the data would

still remain meaning that the registry would not be able to support safe and effective use of

medicines in all patients.

16

Key impacts

There are no impacts resulting directly from this primary legislation as it only seeks the power to

make regulations to establish medicine information systems when the need for a registry is

identified.

If this power was exercised and a registry were to be set up utilising the medicine information

system, requirements would be placed on NHS Digital and potentially the devolved administrations

to capture and process the required data. Where individual health information for a medicine

information system is required from healthcare providers within Scotland or Wales it would be

collected via an intermediary organisation within those territories, unless an exception applies,

rather than, for example, collected directly from healthcare providers. The information would then

be shared onwards with NHS Digital. It is not considered that there will be an additional cost to the

provider of the data when an intermediary organisation is used as we expect that similar or the

same processes for providing the data straight to NHS Digital would be used. There may be small

costs for the intermediary organisation, likely to be a public body, in collecting this data, though it is

expected that this would be minimal as these bodies would already have infrastructure in place to

routinely collect, holds and process data in relation to medicines and health. In establishing each

new registry MHRA and NHS digital would work with the intermediary body or colleagues in Wales

or Scotland to identify who data is needed from and the best route for collection to minimise burden

and cost.

Costs of setting up and running a registry benefiting from a medicines information system are

unlikely to be very different from one that does not use a medicines information system. This is

because the design of a registry, and hence the requirements in terms of the types and volume of

data that would need to be captured, would be determined based on the scientific and regulatory

need which would be the same regardless of whether the regulations made based on the powers

being sought were in place. The purpose of the medicine information systems provisions is to

enable the appropriate authority to make regulations allowing them to direct the Information Centre

to collect the required data and to give the Information Centre a power to require provision of that

data from the relevant data holders. Regulations will also lay out the legal basis for collating and

sharing this data. The technology and supporting governance and documentation required to

deliver a medicines registry designed to meet its scientific and regulatory objectives would be the

same regardless of if it being underpinned by a medicines information system or not. However, the

potential benefits are likely to be greater as the powers provided to require submission of the

requested data will increase participation by HCPs and the availability of more comprehensive and

timely information. This added information would likely address risks to patient health and the

benefits would potentially extend to all patients treated with the medicine.

The provisions will enable NHS Digital to establish and operate UK-wide medicine information

system(s), the information from which will then be available to MHRA to establish comprehensive

national registries.

A figure for the Equivalent Annual Net Direct Cost to Business (EANDCB) has not been possible to

estimate as these provisions are enabling powers. The costs with regards to data provision are

largely expected to fall to the NHS and other public organisations. However, dependent on the

scope of a specific registry data may be sought from private HCPs for example, the potential

impact of data collection on business will depend upon the medicines of interest, remit, scope and

duration of the registry and hence the volume and complexity of the data that needs to be made

available to the information system. Therefore, at this stage it is not possible to estimate what the

potential cost on business may be. Any additional costs to HCPs from contributing to a medicine

registry would be examined as part of the business case process.

Furthermore, and for this same reason, a full small and micro businesses assessment (SaMBA)

has not been completed as part of the IA for the primary legislation. This can be included in future

17

assessments when the design of a specific registry, and therefore its impact on SMBs and other

potential data holders, is clearer. For context, in 2012 approximately 53% of NHS consultants

undertook some private practice, with an estimated 3,000 working entirely in the private sector

2

.

There are an estimated 515 private hospitals offering health care services in the UK, which are a

mixture of for-profit and non-profit. There are no comprehensive public data on the total number of

patients treated in private hospitals, but of the 285 hospitals that submitted data in 2017, 735,522

patients received treatment. By comparison, more than 8.5 million nonurgent patients were treated

by the NHS that year

3

. Again in 2012, an estimated 3% of GP consultations were private (~7

million consultations) although this may have increased since. Any impact on SMBs would be

around their need to submit data to the information system. This data would only consist of

information that they should already be capturing and recording as part of good clinical and

healthcare delivery practice to support individual patient management and safety. We believe there

may be two key categories of costs: i) familiarisation and training costs and ii) costs associated

with the data collection and submission processes. It is plausible that these costs may impact small

providers with less IT capacity more disproportionately. However, by working with the NHS to

deliver systems that integrate with local systems and capture the data into the information system

efficiently we can reduce the burden on businesses

. As described earlier, the number and types of

HCPs expected to contribute to an information system for a new medicine(s) will be unknown until

details of the needs for that medicine are finalised. It is therefore not yet possible to state whether

these businesses will be disproportionately affected or whether an exemption would be

appropriate. Again, potential costs to small and micro businesses will be considered as part of the

individual business case processes. There are no anticipated impacts on competition or

international trade.

There are potential impacts on the justice system. In particular, with regards to clauses on new

offences related to information disclosure from the medicine information system(s) and potential

identification in a specific registry of cases suitable for compensation. A Justice impact test to fully

assess the impacts will be completed in conjunction with the Ministry of Justice.

Indicative estimates of costs and benefits of a national registry

This analysis is an illustrative example as the provision relates to delegated powers to make

regulations about the establishment and operation of medicine information systems rather than the

actual establishment of specific registries. It examines the potential impacts of the use of this

power to enable NHS Digital to establish an information system, or systems to support a specific

registry. The overall aim would be to provide data from the system to MHRA to set up and maintain

such a national registry, using MHRA’s existing pharmacovigilance powers. The intention is to

provide an initial high-level assessment of the impact that the use of this power could have in the

future. This mirrors the approach used to assess the set-up of national registries for medical

devices in the MMD Act 2021 Impact Assessment

4

.

Each individual registry is likely to vary in design (size and function) as the specific risks relating to

the specific product are likely to be different and as a result so are the potential impacts. To

highlight this point, we present cost estimates using data from three existing registries that vary

significantly scope and size (Sodium Valproate

5

, National Joint Registry, Breast and Cosmetic

implants).

2

The Kings Fund, ‘The UK private health market’, 2014. [Online]. Available from:

https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/media/commission-appendix-uk-private-health-market.pdf

3

The private healthcare information network, ‘Annual report 2016-17’, 2017. [Online]. Available from:

https://apicms.phin.org.uk/Content/Resource/158-PHIN_AR_2016-17.pdf

4

Medicines and Medical Devices Bill - IA No: 9556 - 2020

5

https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/mi-medicines-in-pregnancy-

registry/valproate-use-in-females-aged-0-to-54-in-england-april-2018-to-september-2020

18

Also presented are potential benefits of a national medicines’ registry using the England-only

Sodium Valproate registry example. Estimates of benefits must be treated with caution as they are

based on data available so far from the valproate example which is still being developed. These

are for illustrative purposes only. Specific costs and benefits of individual registries must be

considered as part of the business case process.

Costs

MHRA and NHS Digital – set up and running costs

MHRA would be responsible for establishing and running national registries, bringing in relevant

partners as required. This could be through a Registry Steering Committee to provide operational

support and clinical guidance, and oversight of the project’s set up, running, and translation of its

findings. There are likely to be both one off set up and ongoing opportunity costs of MHRA staff

time spent on these activities. It is not anticipated that there will be additional costs to Marketing

Authorisation Holders.

NHS Digital would collect the data needed for all medicine registries from various sources and hold

this in an information system. Data from the information system would be provided to the MHRA to

establish and operate/run medicine specific registries.

Table 1 outlines the cost of setting up three different medicines registries. The table demonstrates

that depending on specific circumstances such as size and scope, set up and running costs can

vary substantially. Similarly, the benefits of the registry may be expected to scale up according to

the size and scope of the registry, as for example a greater number of patients or treatments may

be covered, thus benefitting a larger patient population.

Table1: Indicative set up and running costs of national registries per annum

National registry example

Potential annual costs to MHRA and NHS Digital

(Set up / annual running cost)

Sodium Valproate

£1.014m / £183,000 (estimated)

Breast and Cosmetic Implant

registry

£83,000 / £183,000

National Joint Registry

£1.8m / £4.1m

Sodium Valproate - method to calculate set up and running costs

Based on the Sodium Valproate example, it is estimated that roughly that about 0.5 FTE hours of a

SEO, G6 and SCS costing approximately £164,000 in MHRA staff resources could be spent on a

registry annually

6

. This is an estimated average with likely slightly higher costs in the first 2-3

years, due to the need for more senior staff involvement while the registry is being developed,

balanced by slightly lower costs once it is established.

Total NHS Digital potential staff and non-staff costs on Sodium Valproate is estimated at about

£950,000per annum

based upon the costs for the delivery of the second phase of development

planned for 2021/22. This amounts to a potential total set up of £1.014million annually for the

Sodium Valproate registry. However, this estimate must be treated as indicative only as the

majority of the cost is to develop the registry and once established running costs will be

substantially lower. Beyond the initial set up which is likely to last 2-3 years, maintenance costs

could be estimated to be similar to the BCIR as described below given the comparative size. For

reference, the first year costs for NHS Digital were substantially lower at approximately £20,000.

6

Based on average salary data from MHRA Finance

19

National Joint Registry (NJR) and Breast and Cosmetic Implant registry (BCIR) - method

to calculate set up and running costs

The potential costs to NHS Digital below have been taken from the Medicines and Medical Devices

Bill IA June 2020

7

. The estimates are based on data from the National Joint Registry (NJR) and

Breast and Cosmetic Implant registry (BCIR). The size, scope and amount of activity undertaken

i.e. amount of information collected and how it is used would impact costs. The below is therefore

an indicative range of costs.

One off set up costs:

The MMD IA estimates that a large-scale registry such as the NJR (with over 225,000 procedures

reported to it in 2018) could require an initial set up cost of £1.8m. The BCIR (with just under

15,600 operations reported over a year July 2018-June2019) could involve set up costs of about

£83,000. The costs are likely to cover any IT systems set up, and staff resources to design the

registry and publish guidance for participating providers.

Ongoing costs:

The MMD IA reports ongoing costs of £4.1m per annum for the NJR and £183,000 per annum for

BCIR. Ongoing costs are likely to cover – auditing data collected, analysing and reporting on safety

alerts, communicating with HCPs, researchers, government and the public, IT systems

development as registry evolves.

Administrative costs to NHS and private healthcare providers

It will be mandatory for all HCPs to contribute to an information system. This could involve clinical

staff time spent on undergoing training on the new registry and on an ongoing basis, recording the

data. Some providers may already be providing this data voluntarily to existing MAH registries and

for them the additional costs are unlikely to be significant. The number of HCPs this will impact is

unknown as it will depend on each specific registry and the prescribing trends of each medicine. In

general, HCPs can refer to GPs, private and state hospitals but could also include nurses,

midwives, pharmacists for some registries. However, it is unlikely that the overall costs to HCPs

will be high, as most of the data required are likely to already be collected by HCPs as part of

clinical management.

In the case of Sodium Valproate, women should have annual appointments with a neurologist who

should review their treatment and ensure patients complete a signed annual risk acknowledgement

form (ARAF), which is part of the Pregnancy Prevention Plan. There are currently estimated to be

625 consultant neurologists

8

in England who might review a woman’s valproate treatment. Given

that they already have to undertake regular reviews with patients on their Sodium Valproate use,

the inclusion of an ARAF on the registry is unlikely to increase administrative burdens.

Benefits

More informed patients and greater public confidence in the health system:

Patients can directly report on safety issues and may be more informed on the risks and benefits of

their medicines. This is likely to enable patients to take more informed decisions about their health.

Improved regulatory system:

7

Medicines and Medical Devices Bill - IA No: 9556 - 2020

8

Association of British Neurologists, Neurology Workforce Survey, 2020. [Online]. Available from:

https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.theabn.org/resource/collection/219B4A48-4D25-4726-97AA-

0EB6090769BE/2020_ABN_Neurology_Workforce_Survey_2018-19_28_Jan_2020.pdf

20

Information from medicine information systems will support the establishment of national registries.

This would allow the MHRA to use registries to more widely support safe use of a medicine

through inclusion of it in regulatory information and prescribing guidelines, and to take swift

informed regulatory action, as it is likely to receive timely and more complete data on risks

associated with the specific medicines.

Improved service provision to patients:

Information from a medicine information system and the resulting medicines registry should allow

HCPs to analyse reports on data to evaluate outcomes. HCPs could recall/amend patient

treatment if necessary and offer more efficient and effective services.

Avoided patient harm:

Most importantly, information from medicine information systems and the resulting medicines

registry is likely to give healthcare professionals timely access to more complete information –

including at the individual patient level. This would enable them to take rapid action and avert

potential risks to patient health from adverse effects.

Illustrative example – avoided patient harm from Sodium Valproate registry:

Currently the Sodium Valproate registry, which is the basis of the planned antiepileptics

registry is not mandatory and coverage may not be comprehensive, particularly for women

treated in the private sector. One of the aims of introducing a comprehensive mandatory

Sodium Valproate registry is to increase coverage which should in turn further accelerate

the decline in prescribing and reduce the number of exposed pregnancies. Reducing the

number of exposed pregnancies was a key aim of the 2018 Pregnancy Prevention Plan

(2018). The proposed power would enable NHS Digital to collect data, subject to a

Direction, from private prescribers and from devolved administrations, which would then be

provided to MHRA to establish a comprehensive valproate/anti-epileptic drugs registry.

Therefore, the data illustrated below is a useful example of the possible impact of

enactment of the proposed enabling power.

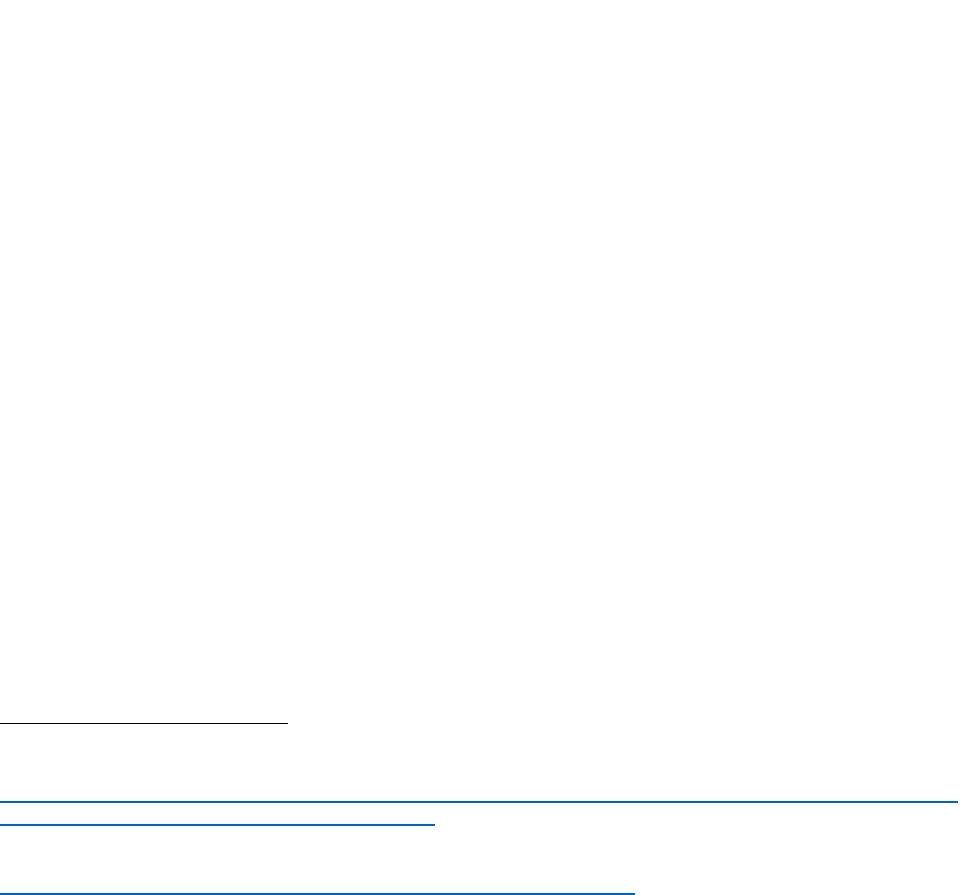

Figure 1 presents data published by the NHS Business Services Authority on the number of

women aged 14-45 in England prescribed Sodium Valproate over time. Figure 1 shows that

in the two years prior to the introduction of the PPP prescribing in women aged 14-45 was

falling by approximately 15%. Following the PPP, prescribing fell approximately by an

additional 10%.

21

Figure 1: The number of female patients aged 14-45 prescribed valproate over time

before and after introduction of the Pregnancy Prevention Plan

The first retrospective data from the non-mandatory Sodium Valproate registry suggest that

between April 2018 and Sept 2020, 181 pregnancies have been exposed to Sodium

Valproate (or approximately 70 per year). One hypothesis is that if a mandatory

comprehensive drug registry were in place, some of these exposures may have been

avoided as there would be more complete data on adherence by prescribers to best

prescribing practices and implementation of the Pregnancy Prevention Programme. Using

an arbitrary assumption of a further 20% reduction in the exposure to Sodium Valproate

following the introduction of a mandatory registry, it is estimated that this would reduce the

number of pregnancies exposed by a further 11 in the year September 2020-21.

Net benefits of the Sodium Valproate registry

This simple analysis examines what Quality Adjusted Life Year (QALY) gains are required

to compensate for the cost of setting up and running the Sodium Valproate registry. The

estimated cost for setting up and running the registry in the second year is £1.014million.

The best estimate for the value society places on a QALY is £60,000

9

. Therefore, it is

estimated that approximately 16.9 QALYs would have to be generated per annum through

development to account for the initial annual cost of the registry. If a 20% reduction in

exposure is achieved this would equate to 1.5 QALY per exposed pregnancy avoided.

However, in future years this would be lower at approximately 3 QALYS generated per

annum and a 0.3 QALY per exposed pregnancy avoided. Given valproate exposure during

pregnancy is associated with an approximately 50% risk of severe and lifelong physical and

neurological disorders this threshold would be reached. This demonstrates that with a very

modest reduction in exposure, only limited QALY gains are required for the net benefits of

the registry to break-even once the initial set up is complete.

9

HM Treasury: The Green Book: appraisal and evaluation in central government, (2020). [Online]. Available

from:

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-green-book-appraisal-and-evaluation-in-central-

governent

0

5,000

10,000

15,000

20,000

25,000

Number prescribed valproate Pre-PPP estimated trend

Introduction

of PPP

22

Avoided costs to NHS from compensation / litigation and additional treatment:

Through early identification of risks and reducing scope for error (outlined above), harm to patients

could be prevented. This might in turn avoid potential claims and litigation costs against the NHS.

Costs to NHS of providing additional treatment to affected patients could also be avoided

10

.

Risks and Mitigations

The purpose of a medicine registry is to generate evidence. This evidence will be used by MHRA

and other organisations to inform regulations and guidance and to drive changes in clinical

practice. However, the economic benefits will only be fully realised if those changes actually

happen, and patient safety is improved. MHRA have an established role in leading within this area.

This is highlighted in the MHRA 2018-2023 Corporate plan

11

and the 2020/21 Business plan

12

,

which lay out the strategy to reshape post-market vigilance to run proactive life-cycle monitoring, of

which this policy is a component, and to increase MHRA influence on clinical practice through

further engagement with patients and key strategic healthcare partners.

2. Professional regulation

Policy summary

The powers in this Act form part of a wider programme to create a more flexible and proportionate

professional regulatory framework that is better able to protect patients and the public. These

powers will make it easier to ensure that professions protected in law are the right ones and that

the level of regulatory oversight is proportionate to the risks to the public.

Section 60 of the Health Act 1999 already provides powers to make changes to the professional

regulatory landscape through secondary legislation. The Act widens the scope of section 60 and

will enable us, where necessary, to make further changes in secondary legislation to ensure the

professional regulation system delivers public protection in a modern and effective way, and,

ensure professions are regulated in the most appropriate manner.

The new powers enable:

i. the abolition of an individual health and care professional regulatory body where the

professions concerned have been deregulated or are being regulated by another body;

ii. the removal of health care professions from regulation where regulation is no longer

required for the protection of the public;

iii. the delegation of certain functions to other regulatory bodies through legislation (which

was previously prohibited); and

iv. the regulation of groups of workers concerned with physical or mental health of

individuals, whether or not they are generally regarded as a profession i.e. senior

managers and leaders.

10

The literature review carried out by NICE estimates the percentage of hospital admissions due to ADRs in

the UK to be 6-7%. Of these ADRs, it is estimated that 1.6-3.7% were to be preventable. One review

estimated that the overall impact of ADRs in England was 4 out of 100 hospital bed stays with an equivalent

cost of about £380 million a year to the NHS in England.

https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/adverse-drug-

reactions/background-information/health-financial-implications-of-adrs/

11

Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), ‘Corporate plan 2018-23’, 2018. [Online].

Available from:

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/702075/C

orporate_Plan.pdf

12

Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), ‘Business plan 2021-21’, 2020. [Online].

Available from:

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/889864/M

HRA_Business_Plan_2020_to_2021.pdf

23

The use of these additional powers will be subject to public consultation and the resulting

secondary legislation would be subject to the affirmative Parliamentary process. DHSC will work

with the regulatory bodies, the Professional Standards Authority and devolved administrations on

provisions to make further improvements to professional regulation through secondary legislation

in line with the other uses of the delegated powers in Section 60, Government will undertake wider

stakeholder engagement including with patient safety groups and the public prior to bringing

forward any legislation using the new powers.

The measures form part of a broader programme to modernise the regulatory system for health

and care professional in the UK. The programme is commencing with legislation that will reform the

legal framework for the General Medical Council and introduce two new professions, anaesthesia

associates and physician associates, into regulation by means of an Order in Council using powers

in the Health Act 1999. This will be followed by further legislation to extend these changes to all

regulated professions. The powers in the Act complement this transition to a modern and effective

professional regulatory system, by making it easier to deliver a reduction in the number of

healthcare professional regulators and make other changes which are being considered as part of

this work.

Rationale for intervention

The UK model of professional regulation for healthcare professionals has become increasingly

rigid and complex and needs to change to better protect patients, support the provision of health

services, and help the workforce better meet current and future challenges.

In 2017, the four UK governments consulted on high-level principles for reform of professional

regulation and set out their five objectives, to:

• improve the protection of the public from the risk of harm from poor professional practice;

• support the development of a flexible workforce that is better able to meet the challenges

of delivering healthcare in the future;

• deal with concerns about the performance of professionals in a more proportionate and

responsive fashion;

• provide greater support to regulated professionals in delivering high quality care; and

• increase the efficiency of the system.

The consultation Promoting professionalism, reforming regulation included questions relating to the

provisions in the Act. The link to the consultation can be found here

. The consultation set out the

proposals that were welcomed by key stakeholders, including professional organisations,

regulators and employers. The link to the consultation response can be found

here.

The consultation response also highlighted the case for broader changes to the regulatory

landscape including reducing the number of regulators. The Secretary of State for Health and

Social Care further committed to reviewing the number of health and care professional regulators

in the November 2020 Busting Bureaucracy policy paper and DHSC has commissioned an

independent review, led by KPMG, who submitted their report at the end of last year and which we

are now considering.

A further consultation Regulating healthcare professionals, protecting the public was published in

May 2021 which sets out reform proposals for all of the regulators. The implementation process

will start with changes to the General Medical Council’s legislation and the other regulators will

follow. A response to the consultation will be published in the next few months.

24

The Government has also consulted on the criteria for determining when statutory regulation of a

healthcare profession is appropriate. The consultation, Healthcare regulation: deciding when

statutory regulation is appropriate, ran from January to March 2022. While the Government

believes that there is no immediate case to change the groups that are regulated, the consultation

sought views on the proposed criteria to make decisions on which professions should be regulated;

whether there are regulated professions that no longer require statutory regulation; and whether

there are unregulated professions that should be brought into statutory regulation. The

consultation responses are currently being considered and a response will be published in due

course.

Additional wider reforms have also been considered such as the government response to the Law

Commission’s review of UK law relating to the regulation of healthcare professionals, and, the

recent review of the fit and proper persons test (further details are included in the fourth power

below).

The powers in the Act are:

i) the abolition of an individual health and care professional regulatory body where the

professions concerned have been deregulated or are being regulated by another body

There is the inevitable duplication in having nine regulatory bodies (10 including Social Work

England) that perform similar functions in relation to different professions. A reduction in the

number of regulators would deliver public protection in a more consistent way, while also delivering

financial and efficiency savings. Powers under section 60 already allow for the creation of new

regulators through secondary legislation. However, similar powers are not currently available to

close a regulator, and this can only be done via primary legislation.

This change would enable Parliament to use secondary legislation to abolish a regulator where its

regulatory functions have been merged or subsumed into another body or bodies, or where the

professions that it regulates have been removed from regulation.

The July 2019 Government response to the Promoting professionalism, reforming regulation

consultation set out the Government’s intention to consider reducing the number of regulators. The

Secretary of State for Health and Social Care further committed to reviewing the number of health

and care professional regulators in the November 2020

Busting Bureaucracy policy paper and

DHSC has commissioned an independent review, led by KPMG, who submitted their report at the

end of last year and which we are now considering. Use of these powers would be subject to

consultation and the affirmative parliamentary procedure.

ii) the removal of health care professions from regulation where regulation is no longer

required for the protection of the public

Statutory regulation should only be used where it is necessary for public protection. The level of

regulatory oversight for each profession should be proportionate to the activity carried out and the

risks to patients, service users and the public.

The landscape of the health and social care workforce is not static, meaning that the risks to the

public will change over time as practices, technology and roles develop. While statutory regulation

may be necessary now for a certain profession, over time the risk profile may change, such that

statutory regulation is no longer necessary. Clearly, in order to protect the public, professionals

such as doctors, nurses, dentists and paramedics will always be subject to statutory regulation.

The Government has recently consulted on the criteria for determining when statutory regulation of

a healthcare profession is appropriate. While the Government believes that there is no immediate

case to change the groups that are regulated, the consultation sought views on the proposed

25

criteria to make decisions on which professions should be regulated; whether there are regulated

professions that no longer require statutory regulation; and whether there are unregulated

professions that should be brought into statutory regulation. The consultation responses are

currently being considered and a response will be published in due course.

A provision to enable the removal of a profession from statutory regulation through secondary

legislation will make it easier to ensure that the protections and regulatory barriers that are in place

remain proportionate for all health and care professions. Any use of these powers would be

subject to consultation and parliamentary approval using the affirmative procedure.

iii) the delegation of certain functions to other regulatory bodies through legislation (which

was previously prohibited)

Currently, there are legal restrictions in place which limit the functions that professional regulators

can delegate to another body. This prohibits regulators from delegating the functions of the

keeping of a register of persons permitted to practise; determining standards of education and

training for admission to practice; giving advice about standards of conduct and performance; and

administering procedures relating to misconduct and unfitness to practise.

The removal of these restrictions would enable further collaboration in how regulation is delivered,

which could drive up quality, reduce costs and provide greater consistency. This would enable a

single regulator to take on the role of providing a regulatory function, such as the holding of a

register, the assessment of international applicants or the adjudication process for fitness to

practice, across some or all regulators. This will help to deliver public protection in a more

consistent fashion and may also increase efficiency. Where a function is delegated, a regulator

would retain responsibility for that function.

iv) the regulation of groups of workers concerned with physical or mental health of

individuals, whether or not they are generally regarded as a profession i.e. senior

managers and leaders

While the definition of those groups which can be included in regulation using the powers in

Section 60 of the Health Act 1999 is broad in relation to healthcare professionals, the proposed

changes allows for the regulation of groups of workers concerned with physical or mental health of

individuals, whether or not they are generally regarded as a profession, to be regulated. .For

example, those in senior management and leadership roles and other groups of workers are within

the scope of future regulation.

The 2019 Kark review of the fit and proper persons test recommended putting in place stronger

measures to ensure that NHS senior managers and leaders have the right skills, behaviours and

competencies. While it stopped short of recommending full statutory regulation, NHS

England/Improvement is currently considering how best to take forward the recommendations.

Extending the scope of professions who can be regulated using the powers in Section 60 of the

Health Act 1999 would provide additional flexibility to extend statutory regulation to, for example

NHS managers and leaders in the future, if further measures are needed.

Other policy options considered

Option 0 - Business as usual (Do nothing)

Not being able to expand the scope of Section 60 of the Health Act 1999 will restrict the extent of

reform can be made. Proposals are currently being developed using the powers available to

reform professional regulation in the areas of fitness to practise, governance and operating

26

framework, and the registration and education and training functions. However, the aim is to go

further to modernise professional regulation and the new powers will support this.

Option 1 - Seek fewer powers

If fewer powers were established through the Act, then it would be expected that primary legislation

would be pursued for the remaining powers in the near future. This is because all of the powers

proposed are expected to be required as part of our reform programme. This will delay completion

of our reform programme.

Costs

These provisions seek new powers to be taken forward through secondary legislation. There are

therefore no costs associated with these powers coming into force. An impact assessment which

calculates associated costs will be completed if the powers are put into effect.

Benefits

As mentioned above, these provisions seek new powers to be taken forward through secondary

legislation. Therefore, the benefits from all provisions are indirect and depend on the actions of the

Secretary of State. The potential benefits of these enabling powers, if put into effect through

secondary legislation, are outlined in the Rationale for Intervention section. An impact assessment

which calculates associated benefits will be completed if the powers are put into effect.

Important note

We are currently engaging with the devolved administrations, Treasury, Cabinet Office,

Department for Education and the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy

regarding the reform proposals.

3. Medical examiners

Policy summary

This policy allows NHS bodies in England and Welsh NHS bodies in Wales to appoint medical

examiners instead of local authorities and local health board respectively. This is so that medical

examiners employed in the NHS system will have access to information in the sensitive and urgent

timescales required to register a death. The following paragraphs of the policy summary section

set out the steps taken in the development of this policy.

The Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) has developed policy over the past several

years which aims to provide a reformed system for certifying non-coronial deaths which improves

the quality and accuracy of Medical Certificate of Cause of Deaths (MCCDs) and provides

adequate scrutiny to identify and deter criminal activity or poor practice. The legal framework of this

system is set out in Part 1 of the Coroners and Justice Act 2009, but remains uncommenced at this

time, save for sections 18 and 21 as set out below.

As part of this work, DHSC ran a consultation from March to June 2016 seeking views on the detail

of the operation of the proposed reforms to the death certification process and draft regulations

setting out the system within which the services would operate. The consultation document

proposed the introduction of a unified system of scrutiny by independent medical examiners,

hosted by local authorities, of all deaths in England and Wales that are not investigated by a