1

NFHS | www.nfhs.org/hstoday

No matter where you live in this great country, October likely is

one of your favorite months of the year. The heat is winding down

in the South, leaves are falling in the Midwest with the transition of

seasons, snow has yet to accumulate in the Northeast and the West

Coast is as gorgeous as ever.

October is a marquee month in high school sports as well.

Throughout the 50 states and the District of Columbia, on any given

Friday night, there are approximately 7,000 high school football

games involving more than one million student-athletes.

During the week there are cross country meets, volleyball and

soccer matches, and field hockey games. In many of those same

schools, students are involved in the various performing arts activ-

ities such as speech, debate, music and theatre.

More than 11 million students participate in activity programs at

the high school level, and the NFHS has designated October as “Na-

tional High School Activities Month.” In the past, the third week in

October was set aside for “National High School Activities Week,”

but we’ve expanded the celebration to the entire month this year.

And there is much to celebrate. Our cover story on page 12 re-

ports on another record-breaking year in sports participation. Dur-

ing the 2010-11 school year, participation in high school sports

increased for the 22nd consecutive time and produced a record-

breaking total of 7,667,955 participants. And the survey showed

that more than 55 percent of students enrolled in high schools par-

ticipate in athletics.

Outdoor track and field, cross country and the emerging sport

of lacrosse registered significant increases in participation, along

with boys and girls soccer, girls volleyball and boys basketball. Girls

lacrosse increased nine percent from the previous year and cracked

the girls Top 10 listing for the first time.

That great news came on the heels of our feature in the Sep-

tember issue of High School Today which indicated that approxi-

mately 510 million fans attended high school sporting events during

the 2009-10 school year, including 468 million during regular-sea-

son events and 42 million for state association playoff contests.

About two-thirds of those fans (336 million) attended high

school regular-season and playoff games in football and girls and

boys basketball – more than 2½ times the 133 million spectators

who attended events in those sports at the college and professional

levels combined. Girls and boys basketball accounted for 170 mil-

lion fans, while football was close behind at 166 million, with soc-

cer third at 24 million.

Granted, there are many more games played at the high school

level to reach that prodigious figure, but it is a great sign that high

school sports continue to be a big part of communities throughout

our nation. A ticket to a high school sporting event remains one of

the best values for the entertainment dollar.

While these latest surveys on participation and attendance were

extremely encouraging, we know there is much work ahead. With

budget issues forcing many schools to find alternative methods of

funding or cut back on programs, school leaders must continue to

champion the cause for high school athletic and performing arts

programs.

These vital programs provide one of the best bargains in our

community and will continue to do so as long as our nation sup-

ports them as an integral part of the education of our young peo-

ple. These programs teach more than 11 million young people

valuable life skills lessons such as ethics, integrity and healthy

lifestyles.

There is fundamental, empirical evidence that high school ac-

tivity programs provide a successful way in which to create healthy

and successful citizens. Many of these studies are documented in

The Case for High School Activities, which is available on our Web

site at www.nfhs.org.

Although promoting the value of these programs in our nation’s

schools should be a ongoing, year-long event, we encourage you

to go the extra mile this month as we celebrate National High

School Activities Month. Take this opportunity to toot your horn

even louder, to show appreciation to your communities for their

support of your programs, to thank those spectators who support

your activity programs throughout the year, and recognize the

coaches and contest officials who make it all possible.

Thanks for all you do to keep the doors of opportunity open for

the nation’s student-athletes.

NFHS REPORT

BY ROBERT B. GARDNER, NFHS EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, AND RICK WULKOW, NFHS PRESIDENT

Celebrating the Value of High

School Activity Programs

4

High School Today | October 11

EDITORIAL STAFF

Publisher.......................Robert B. Gardner

Editor............................Bruce L. Howard

Assistant Editor .............John C. Gillis

Production.....................Randall D. Orr

Advertising....................Judy Shoemaker

Graphic Designer ...........Kim A. Vogel

Online Editor .................Chris Boone

PUBLICATIONS COMMITTEE

Superintendent..............Darrell Floyd, TX

Principal........................Ralph Holloway, NC

School Boards ...............Jim Vanderlin, IN

State Associations..........Treva Dayton, TX

Media Director ..............Robert Zayas, NM

Performing Arts..............Steffen Parker, VT

Athletic Director ............David Hoch, MD

Athletic Trainer ..............Brian Robinson, IL

Coach ...........................Don Showalter, IA

Legal Counsel................Lee Green, KS

Contest Official..............Tim Christensen, OR

VOLUME 5, NUMBER 2

High School Today, an official publica-

tion of the National Federation of State

High School Assoc ia tions, is published

eight times a year by the NFHS.

EDITORIAL/ADVERTISING OFFICES

National Federation of

State High School Associations

PO Box 690, Indianapolis, Indiana 46206

Telephone 317-972-6900; fax 317.822.5700

SUBSCRIPTION PRICE

One-year subscription is $24.95. Canada add

$3.75 per year surface post age. All other foreign

subscribers, please contact the NFHS office for

shipping rates. Back issues are $3.00 plus actual

postage.

Manuscripts, illustrations and photo graphs may

be submitted by mail or e-mail to Bruce Howard,

editor, PO Box 690, Indianapolis, IN 46206,

<bhoward@nfhs.org>. They will be carefully

considered by the High School Today Publica-

tions Committee, but the publisher cannot be re-

sponsible for loss or damage.

Reproduction of material published in High

School Today is prohibited with out written per-

mission of the NFHS executive director. Views of

the authors do not always reflect the opinion or

policies of the NFHS.

Copyright 2011 by the National Fed eration

of State High School Associa tions. All rights

reserved.

Contents

HighSchool

THE VOICE OF EDUCATION-BASED ATHLETIC AND PERFORMING ARTS ACTIVITIES

TODAY

™

High School Sports Participation Continues Upward Climb:

Participation in high school sports increased for the 22nd consec-

utive year in 2010-11.

COVER STORY

Welcome

We hope you enjoy this publication

and welcome your feedback. You may

contact Bruce Howard, editor of High

School Today, at [email protected].

12

Cover photo provided by Kim Jew Photography, New Mexico.

5

NFHS | www.nfhs.org/hstoday

HST ONLINE

You can access previous issues online

at www.nfhs.org/hstoday

.

DEPARTMENTS

FEATURES

NFHS Report

Quick Hits

Interesting Facts and Information

Legal Issues

Free Speech Rights vs. Student Postings

on Social Media Sites

Performing Arts

In the Limelight: Sustaining a Successful

Theatre Program

Above and Beyond

‘Officials for Kids’ Program Makes the Right Call

Ideas That Work

North Carolina Captain Retreat Program

Teaches Leadership, Communication

In Their Own Words

Female Tackles Daunting Task as Wrestling

Coach at School for Blind

Technology

Meeting Wizard – an Online Scheduling

Program

Sports Medicine

Academic Accommodations After

a Sports-related Concussion

Coach Education

Concussion Course Leading Way for NFHS

Coach Education Program

In the News

Voices of the Nation

1

6

14

18

20

24

28

33

34

36

39

40

18 28

33

ACTIVITY PROGRAMS

Strategies to Generate

Support for Interscholastic

Programs: Administrators

must provide justification for

programs. –Gary Stevens

SPORTS SAFETY

Basketball Buffer Zones:

Accidents Waiting to

Happen: Adequate space,

padding should be available

on basketball courts.

–Todd L. Seidler, Ph.D.

RISK MANAGEMENT

State Associations Defend

New Field Hockey Eyewear

Rule: To reduce potential for

catastrophic injuries, eyewear

is now mandatory in field

hockey. –Eamonn Reynolds

ADMINISTRATION

Creating a Positive

Experience for a Visiting

Team: How the home team

welcomes and treats its

guests is an integral element

of sportsmanship.

–Michael Williams, CMAA and

Michael Duffy, CMAA

16

30

26

22

6

High School Today | October 11

QUICK HITS

Hawkeye State produces

back-to-back record-holders

Twice in two weeks, an Iowa

high school football player tied the

national record for most intercep-

tions returned for a touchdown in a

quarter of an 11-player football

game.

On August 26, Urbandale

(Iowa) High School sophomore

Allen Lazard (left) returned two

interceptions for touchdowns in

the first quarter of Urbandale’s

game with Des Moines (Iowa)

Hoover.

Just one week later on September 2, senior safety Tim Kilfoy

of Davenport (Iowa) Assumption High School did the same

thing against Burlington (Iowa) High School. The 6-1, 190-pound

Kilfoy returned interceptions of 53 and 77 yards for touchdowns in

the second quarter of Assumption’s 42-7 victory.

In the process, Kilfoy etched his name into the NFHS’ National

High School Sports Record Book along with Lazard as national

record-holders in that category. Kilfoy now has 14 interceptions in

his career.

Vaughn ties national record

Hailing from the Show-Me State, Springfield (Missouri) Glen-

dale High School running back Trevor Vaughn has certainly

shown the nation his ability to turn kickoffs into touchdowns.

In Glendale’s season-opening 50-37 home victory over Joplin

(Missouri) High School on September 9, the 5-foot-9, 170-pound

senior returned three kickoffs for touchdowns. He accomplished

that feat on returns of 93, 92 and 68 yards.

In the process, not only did he set the new Missouri single-game

state record, he also tied the national record of three kickoff re-

turns for scores. According

to National Federation of

State High School Associa-

tion’s National High School

Sports Record Book, five

other players had previ-

ously performed that feat.

Glendale also received

four touchdowns from 6-

4, 210-pound senior wide

receiver Cameron Johnson,

who scored three touch-

downs through receptions

and one on an interception

return.

Top High School Performances

Unusual Nicknames

Mayfair Monsoons

Despite its location in sunny, Southern California, Mayfair High School in

Lakewood

, rains on its opponents as the Monsoons. The school, located in

Los Angeles County, uses a tornado as its mascot and continues the meteoro-

logical theme with the name of its newspaper (The Windjammer) and its year-

book (Tradewinds). Notable alumni include the NBA’s Josh Childress and

Alterraun Verner of the Tennessee Titans.

8

High School Today | October 11

Legal Brief

Editor’s Note: This column features an analysis of a landmark court case highlighting a key standard of practice for

scholastic sports programs. This material is provided by Lee Green, an attorney and member of the High School Today

Publications Committee.

Brokaw v. McSorley & Winfield-Mt. UCSD

Iowa Court of Appeals 2008

Facts: A basketball player filed a civil suit for bat-

tery against an opposing player for injuries sustained

from an intentional and malicious elbow to the face

during a game. The suit also alleged negligent super-

vision against the opposing school and its coaches for

encouraging excessively rough play and the use of a

level of violence that violated the rules of basketball.

Issue: Can a sports participant recover damages

from another participant and/or opposing coaches

and schools for injuries sustained during an athletic

contest?

Ruling: Although the “contact sports exception”

shields participants from liability for injuries resulting

from ordinary negligence during a contest, the

exception does not shield participants who

commit intentional or malicious acts or

coaches who encourage the use of excessively

violent techniques. The court found the op-

posing player liable for battery and $23,000 in

damages, but concluded that the coaches

were not liable because they had never en-

couraged the use of violent or illegal tech-

niques.

Standard of Practice: One aspect of the

duty of supervision for athletics personnel is to

coach and monitor players to prevent the use

of excessively violent or illegal techniques that

foreseeably could injure opposing players.

Around the Nation

Question: Has your state legislature mandated a concussion

law and/or education in your state?

9

NFHS | www.nfhs.org/hstoday

BY SHANE MONAGHAN

Despite being born with a congenital heart defect and under-

going open-heart surgery at age three, Lauren Cheney of Indi-

anapolis, Indiana, refused to let those challenges deter her from

her dreams.

After the surgery, Cheney’s medical team encouraged her par-

ents to keep her active and get her involved with sports to keep her

heart strong. Before turning six, she had become a soccer stand-

out. And at age eight, her one and only goal was to become an

Olympic soccer player.

Cheney went to Indianapolis (Indiana) Ben Davis High School,

where she continued her soccer career. Cheney immediately be-

came an asset to the team, receiving Metropolitan Interscholastic

Conference (MIC) All-Conference honors as a freshman. Not only

was Cheney a soccer standout during her four years at Ben Davis,

but she was also a member of the varsity basketball team until her

senior year.

Alongside then-teammates, University of Connecticut mid-

fielder Annie Yi and University of Louisville midfielder Kate Cun-

ningham, Cheney led Ben Davis to its best record in school history,

and also led the team with 35 goals and 15 assists in her senior sea-

son. Ben Davis advanced to the semi-state round of the Indiana

High School Athletic Association 2A state tournament in 2005,

eventually falling to Zionsville (Indiana) High School.

During her career at Ben Davis, Cheney amassed multiple ac-

colades including MIC All-Conference honors in 2003, 2004 and

2005. Cheney was the Indianapolis Star and Metro Player of the

Year in 2004 and the Super Team Player of the Year in 2005. She

was also named both Indiana Girls State Player of the Year and

National Soccer Coaches Association of America National Youth

and High School Player of the Year in 2005.

After her senior season, Cheney graduated midyear from Ben

Davis to train full-time with the United States Under-20 (U-20)

team for the FIFA U-20 Women’s World Cup. Cheney went on to

play at UCLA, where she set school records for points with 173

and game-winning goals with 28. She tied former Bruin Traci

Arkenberg for the school record for career goals with 71. During

Cheney’s four years at UCLA, the Bruins played in four consecutive

NCAA College Cups.

In 2008, Cheney’s Olympic dream was answered as she was

named to the U.S. roster for the 2008 Summer Olympics, where

she appeared in three games as a substitute as the United States

won the Gold Medal.

In January 2010, Cheney was selected with the second overall

pick by the Boston Breakers of Women’s Professional Soccer.

As a member of the United States Women’s National Team in

the 2011 FIFA Women’s World Cup, Cheney scored her first goal

for the U.S. team against North Korea. She scored the first goal

and assisted on the winning goal in the semifinal against France.

The United States eventually lost to Japan in the finals.

Without a doubt, wherever Cheney goes, success is sure to fol-

low. From an open-heart surgery procedure, to her high school ca-

reer and eventually her Olympic success, Cheney is proof of that

dreams really do come true.

Shane Monaghan is a fall intern in the NFHS Publications/Communications and Events

Departments. Monaghan is a graduate of Ball State (Indiana) University, where he

specialized in sports administration.

Lauren Cheney

It All Started Here

10

High School Today | October 11

For the Record

Source: 2011 National High School Sports Record Book. To view the

Record Book, visit the NFHS Web site at www.nfhs.org and select

“Publications” on the home page.

Dano Graves

(Folsom, CA), 2009

Tim Couch

(Hyden Leslie County, KY), 1994

Corey Robinson

(Lone Oak, KY), 2007

Garrett Grayson

(Vancouver Heritage, WA), 2009

Daniel Gonzalez

(Los Angeles Franklin, CA), 1999

Tim Couch

FOOTBALL

Highest Completion

Percentage, Season

75.2%

75.1%

73.7%

73.2%

72.3%

STRING INSTRUMENTS

The Cost

Item Average Price Low High

(A) Violin (Under size) ......................... $450 ..............$99............$800

(B) Violin (Full size) ............................. $900 ..............$99.........$1,700

(C) Viola (Under size)............................ $575 ............$150.........$1,000

(D) Viola (Full size)............................. $1,125 ............$250.........$2,000

Item Average Price Low High

(E) Cello (Under size)......................... $1,425 ............$350.........$2,500

(F) Cello (Full size)............................. $2,000 ............$500.........$3,500

(G) String Bass (Under size) ............... $2,100 ............$700.........$3,500

(H) String Bass (Full size) ................... $3,100 .........$1,200.........$5,000

(I) Harp ............................................. $6,500 .........$3,000.......$10,000

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

H

*These prices serve as approximate costs and are not intended to reflect

any specific manufacturer’s prices.

I

12

High School Today | October 11

articipation in high school sports increased for the 22nd

consecutive school year in 2010-11, according to the an-

nual High School Athletics Participation Survey conducted

by the National Federation of State High School Associations (NFHS).

Based on figures from the 50 state high school athletic/activity

associations, plus the District of Columbia, that are members of

the NFHS, sports participation for the 2010-11 school year reached

another record-breaking total of 7,667,955 participants.

Boys and girls participation figures also reached respective all-

time highs with 4,494,406 boys and 3,173,549 girls participating in

2010-11 – an overall increase of 39,578 participants from 2009-10.

“While the overall increase was not as much as we’ve seen in

the past few years, we are definitely encouraged with these totals

given the financial challenges facing our nation’s high schools,”

said Bob Gardner, NFHS executive director. “The benefits of edu-

cation-based athletics at the high school level are well-documented,

and we encourage communities throughout the nation to keep

these doors of opportunity open.

“Based on the survey, 55.5 percent of students enrolled in high

schools participate in athletics, which emphasizes and reinforces

the idea that high school sports continue to have a significant role

in student involvement in schools across the country.”

Cross country and outdoor track and field gained the most par-

ticipants in boys sports last year, with increases of 7,340 and 7,179,

respectively. Other boys sports with significant jumps were soccer

(6,512), basketball (5,637) and lacrosse (5,013). Three sports with

lower overall participation totals registered large percentage gains

in 2010-11 – fencing (up 38 percent to 2,027 participants),

weightlifting (up 12 percent to 22,161 participants) and badminton

(up 9.4 percent to 4,693 participants).

High School Sports

Participation Continues

Upward Climb

P

COVER STORY

Schools Participants

1. Basketball 17,767 1. Track and Field – Outdoor 475,265

2. Track and Field – Outdoor 16,030 2. Basketball 438,933

3. Volleyball 15,479 3. Volleyball 409,332

4. Softball – Fast Pitch 15,338 4. Softball – Fast Pitch 373,535

5. Cross Country 13,839 5. Soccer 361,556

6. Soccer 11,047 6. Cross Country 204,653

7. Tennis 10,181 7. Tennis 182,074

8. Golf 9,609 8. Swimming and Diving 160,881

9. Swimming and Diving 7,164 9. Competitive Spirit Squads 96,718

10. Competitive Spirit Squads 4,266 10. Lacrosse 74,927

TEN MOST POPULAR GIRLS PROGRAMS

Photo provided by Action Image Photography, Wellsburg, West Virginia.

13

NFHS | www.nfhs.org/hstoday

Among girls sports, the emerging sport of lacrosse led the way

with an additional 6,155 participants – an increase of nine percent

from the previous year. With 74,927 participants nationwide,

lacrosse cracked the girls Top 10 listing for the first time as it moved

past golf (71,764). Outdoor track and field was close behind

lacrosse with an additional 6,088 participants, followed by soccer

(5,440), volleyball (5,347) and cross country (2,685).

Sports with lower overall girls participation totals that registered

the largest percentage gains were wrestling (up 19.8 percent to

7,351 participants), badminton (up 14 percent to 12,083 partici-

pants) and weightlifting (up 11 percent to 8,237 participants).

The top 10 participatory sports for boys remained the same

from 2009-10: Eleven-player football led the way with 1,108,441,

followed by outdoor track and field (579,302), basketball

(545,844), baseball (471,025), soccer (398,351), wrestling

(273,732), cross country (246,948), tennis (161,367), golf

(156,866), and swimming and diving (133,900).

Outdoor track and field was the top sport for girls again last

year with 475,265 participants, followed by basketball (438,933),

volleyball (409,332), fast-pitch softball (373,535), soccer (361,556),

cross country (204,653), tennis (182,074), swimming and diving

(160,881), competitive spirit squads (96,718) and lacrosse (74,927).

Texas and California once again topped the list of participants

by state with 786,626 and 774,767, respectively, followed by New

York (388,527), Illinois (350,144), Ohio (328,430), Pennsylvania

(316,687), Michigan (314,354), New Jersey (255,893), Florida

(245,079) and Minnesota (234,901).

Although the rise in girls participation numbers was not as large

this past year (due, in part, to significant drops in competitive spirit

numbers in two states), the percentage increase rate has more than

doubled the rate for boys during the past 20 years – 63 percent to

31 percent. Twenty years ago, girls constituted 36 percent of the

total number of participants; this past year, that number has

climbed to 41 percent. In Oklahoma, the number of female partic-

ipants actually exceeded the number of boys this past year – 44,112

to 42,694.

The participation survey has been compiled since 1971 by the

NFHS through numbers it receives from its member associations.

The complete 2010-11 High School Athletics Participation Survey

is available on the NFHS Web site at

www.nfhs.org.

Photos provided by 20/20 Photographic, Mt. Pleasant, Michigan.

Schools Participants

1. Basketball 18,150 1. Football – 11-Player 1,108,441

2. Track and Field – Outdoor 15,954 2. Track and Field – Outdoor 579,302

3. Baseball 15,863 3. Basketball 545,844

4. Football – 11-Player 14,279 4. Baseball 471,025

5. Cross Country 14,097 5. Soccer 398,351

6. Golf 13,681 6. Wrestling 273,732

7. Soccer 11,503 7. Cross Country 246,948

8. Wrestling 10,407 8. Tennis 161,367

9. Tennis 9,839 9. Golf 156,866

10. Swimming and Diving 6,899 10. Swimming and Diving 133,900

TEN MOST POPULAR BOYS PROGRAMS

Photo provided by Northwest Sports Photography, Beaverton, Oregon.

14

High School Today | October 11

The Issue

Since the launch of MySpace in 2003, Facebook in 2004, Twitter

in 2006, Google+ in 2011 and their numerous social networking

progeny, schools and athletics programs have been struggling with a

new issue related to codes of conduct for students and student-ath-

letes: the extent of school legal authority over off-campus postings

by students on social media Web sites.

An increasing number of lawsuits are being filed each year by stu-

dents suspended from school or athletics for allegedly inappropriate

postings on such sites, with the plaintiffs asserting that they have pro-

tected First Amendment free speech rights to engage in off-campus,

online speech and that the codes of conduct pursuant to which they

were disciplined were unconstitutionally vague because the policies

did not adequately define prohibited behaviors.

The challenge for schools attempting to develop social media poli-

cies has been the lack of clear legal guidelines regarding school au-

thority to restrict off-campus student speech that takes place via new

technologies. However, during 2011, five social media lawsuits have

been decided by U.S. Courts of Appeal – three in favor of students

and two in favor of schools.

Two of the cases, one decided in favor of a student and one de-

cided in favor of a school, are being appealed to the U.S. Supreme

Court and the confusion created by the conflicting rulings has cre-

ated the type of perfect judicial storm into which the Supreme Court

is likely to intervene in order to create uniformity of law across the

country.

Doninger v. Niehoff

In April, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit ruled in

favor of administrators at Lewis S. Mills High School in Connecticut

who took disciplinary action against a student, Avery Doninger, who

as a protest against the rescheduling of a student council event made

off-campus postings on her blog that referred to school personnel as

“douchebags” and encouraged readers to inundate school personnel

with phone calls and e-mails in order to “piss them off more.” Al-

though Doninger was not suspended from school, she was prohibited

from running for a class office and her supporters were also prohib-

ited from wearing “Team Avery” t-shirts at a school election assem-

bly.

In ruling in favor of school personnel, the Second Circuit relied on

the “substantial disruption” standard established by the U.S. Supreme

Court in the 1969 Tinker v. Des Moines case, stating that Doninger’s

conduct “posed a reasonably foreseeable risk that it would come to

the attention of school authorities and materially and substantially

disrupt the work and discipline of the school.”

The court also relied on the Sixth Circuit’s 2007 decision in Low-

ery v. Euverard upholding the suspension from a high school football

team of players who were actively campaigning to have their coach

fired. The Sixth Circuit used the Tinker substantial disruption standard

in concluding that the players were undermining the authority of their

coach and materially interfering with the orderly operation of the

team.

In July, Doninger filed a petition for a writ of certiorari with the U.S.

Supreme Court, but as of mid-September, the Court had not yet an-

nounced whether it will hear her appeal.

J.S. v. Blue Mountain School District

In June, the Third Circuit sitting en banc (all 14 circuit judges par-

ticipating) held that the Blue Mountain School District (BMSD) in Penn-

sylvania violated the free speech rights of a minor, J.S., when it

suspended her from school for creating on her home computer a fake

MySpace profile of her school principal that incorporated profanity

and characterized him as a sex addict and pedophile.

Using Tinker analysis, the court stated that “[her] speech did not

cause a substantial disruption in the school” and the court also con-

cluded that the Supreme Court’s ruling in the 1986 case Bethel School

BY LEE GREEN, J.D.

LEGAL ISSUES

Free Speech Rights vs. Student

Postings on Social Media Sites

15

NFHS | www.nfhs.org/hstoday

District v. Frasier that schools may prohibit “sexually explicit, indecent,

or lewd speech” does not apply to speech that takes place off-cam-

pus.

In July, the BMSD announced that it intends to petition the U.S.

Supreme Court to review the case, but as of mid-September, the dis-

trict’s application for certiorari had not yet been filed with the Court.

Layshock v. Hermitage School District

On the same day as its decision in J.S. v. Blue Mountain School

District, the Third Circuit sitting en banc held that the Hermitage

School District (HSD) in Pennsylvania violated the free speech rights of

a student, Justin Layshock, who had on his grandmother’s home com-

puter created a parody MySpace profile of his school principal, when

it suspended him, transferred him into an alternative education pro-

gram and prohibited him from participating in graduation ceremonies.

The profile contained numerous vulgarities and sexual innuendos and

a picture of the principal taken from the HSD Web site.

The Third Circuit rejected the HSD argument that the student’s

behavior was “on-campus” because of his use of the district Web site

to download the principal’s picture and in ruling for the student stated

“we do not think that the First Amendment can tolerate the School

District stretching its authority into Justin’s grandmother’s home and

reaching Justin while he is sitting at her computer.”

Kowalski v. Berkeley County Schools

On July 27, the Fourth Circuit ruled that the Berkeley County

Schools (BCS) in West Virginia did not violate the free speech rights

of a student, Kara Kowalski, who created a MySpace discussion group

page designed solely as a vehicle for her two dozen “friends” who

joined the page to cyberbully another student, Shay N., through the

use of profane and offensive postings of derogatory comments about

and altered photographs of the target student. Kowalski’s name for

the page, S.A.S.H., was an acronym for “Students Against Shay’s Her-

pes” and doctored photos falsely implied that Shay N. suffered from

the disease.

The BCS found Kowalski in violation of the district’s anti-bullying

policy and suspended her from school for 10 days and extracurricu-

lar activities for 90 days, thus barring her from participating in cheer-

leading and the school’s “Charm Review” club, a finishing school-type

activity for which Kowalski had the previous year been elected

“Charm Queen.”

The Fourth Circuit’s decision upholding the district’s discipline of

Kowalski concluded that bullying, cyberbullying and other forms of

harassment satisfy the Tinker “substantial disruption” standard. De-

spite Kowalski’s argument that off-campus speech is beyond the au-

thority of the school to regulate, the court stated that “when she

used the Internet as the medium, Kowalski indeed pushed her com-

puter’s keys in her home, but she knew that the electronic response

would be, as it in fact was, published beyond her home and could

reasonably be expected to reach the school and impact the school

environment.”

D.J.M. v. Hannibal Public School District

On August 1, the Eighth Circuit ruled that the Hannibal Public

School District (HPSD) in Missouri did not violate the free speech rights

of a student, D.J.M., who used instant-messaging on his home com-

puter to communicate highly derogatory and threatening messages

that he intended to use a gun to kill specific students, including his

older brother, other named individuals, and particular members of

certain groups he hated, including “midgets, fags and Negro bitches.”

Upon learning of D.J.M.’s electronic communications, district per-

sonnel contacted law enforcement and the student was arrested, re-

ferred for psychiatric evaluation and briefly detained in a juvenile

facility. After the HPSD suspended him for the remainder of the school

year, D.J.M. filed suit against the district, asserting that his online mes-

sages had been a joke and that the disciplinary action violated his free

speech rights.

The Eighth Circuit concluded that D.J.M.’s speech was not consti-

tutionally protected because it constituted a “true threat” – “a state-

ment that a reasonable recipient would have interpreted as a serious

expression of intent to cause harm or injury to another.” Although ac-

knowledging that the Supreme Court has not yet addressed the issue

of school authority over student speech that occurs away from school,

the Eighth Circuit commented that the Tinker substantial disruption

should be applied to off-campus speech where school officials “might

reasonably forecast substantial disruption or material interference with

school activities.”

T.V. & M.K. v. Smith-Green Community Schools

On August 10, a U.S. District Court in Indiana ruled that the Smith-

Green Community Schools (SGCS) violated the free speech rights of

two volleyball players when they were suspended from the team and

other extracurricular activities for off-campus postings of profanely

captioned photographs on social media sites depicting themselves at

a slumber party in various states of undress and engaged in sexually

suggestive poses with phallus-shaped lollipops. Although the court

never addressed the issue as to whether the Tinker substantial dis-

ruption standard applies to off-campus speech, the court concluded

that the postings did not create a substantial disruption of the school

or athletics environment. The court also concluded that the SGCS’s

code of conduct for students participating in extracurricular activities

and athletics was unconstitutionally vague and that to be enforce-

able, codes of conduct and social media policies need to be highly

specific with regard to defining prohibited behaviors.

Lee Green is an attorney and a professor at Baker University in Baldwin City, Kansas,

where he teaches courses in sports law, business law and constitutional law. He is a

member of the High School Today Publications Committee. He may be contacted at

16

High School Today | October 11

t a time when school systems are struggling financially to

maintain existing programs, the future of interscholastic

athletics is at a crossroads. Athletic administrators through-

out the nation have been charged by school superintendents to

maintain programs with little or no additional financial support.

Needs-based budgeting has been replaced by a new imperative to do

more with less. Under conditions of economic duress, athletic direc-

tors have been given a simple choice: find alternative methods to

raise money to fund their programs or make drastic cuts to operate

within limited means.

Complicating this scenario is the proliferation of sport alterna-

tives for students. No longer can school athletics lay claim to being

the “only show in town.” Club athletics and recreational activities

are competing with schools for the same participants who have his-

torically populated school teams. In a time when many athletic di-

rectors are reducing the number of contests and limiting travel, club

programs may appear more appealing to elite athletes and those

youngsters seeking exposure to college coaches.

Given these challenges, athletic administrators must take the

lead role in providing support and justification for these programs.

Validating the need for education-based athletics requires the ath-

letic director to assert his/her role as an educational leader. Through

collection and publication of data related to student-athlete per-

formance in the classroom, promotion of the positive publicity gen-

erated by both athletes and coaches, and department procedures

supporting the school’s educational mission, the athletic director

can effectively make the case that school athletics is more than

“extracurricular.”

Athletic administrators should use a variety of strategies to sup-

port the case for their programs. Collecting information related to

how athletics supports a school system’s mission is an essential part

of the process. Even when financial resources are adequate, it is im-

portant to gather statistical and anecdotal data about how athletics

fosters student learning. The following strategies may prove helpful

to an athletic director seeking to make this connection:

Track the educational achievements

of student-athletes

Athletic administrators should make great efforts to track the ac-

ademic accomplishments of student-athletes on a seasonal basis.

Many athletic administrators track the grade-point averages of their

teams and publicly recognize squads that exceed targeted levels. Oth-

ers recognize individual students who maintain honor status as

“scholar-athletes” or who earn all-academic honors at the state or

conference levels. In turn, the names of students receiving these hon-

ors should be reported to the local educational authorities.

Collect attendance data on student-athletes

Peggy Johnson, director of athletics for the Savannah-Chatham

(Georgia) Public Schools, oversees athletic programs involving 35,000

youngsters in seven high schools and 12 middle schools in her sys-

tem. As part of her data collection process, she analyzes information

related to student attendance rates for all students. Johnson observes

that attendance rates for students involved in activities significantly

exceed those of youngsters who are non-participants. She observes

that student-athletes outperform all others in the classroom and are

less likely to drop out of school.

Johnson presents this information to her school board each year

as part of her rationale for maintaining programs, and her efforts

have yielded impressive results. Johnson’s budgets have actually in-

creased by more than 33 percent each year. “This is a bargain price

for what you get for each dollar,” Johnson observes. “ [As a result]

school boards recognize we cannot cut athletics.”

Collect cost-per-pupil data to demonstrate

the efficiency of your operation

Efficiency is a hallmark of a good athletic director. In today’s eco-

nomic climate, athletic administrators assume the responsibility of

Strategies to Generate

Support for Interscholastic

Programs

BY GARY STEVENS

A

17

NFHS | www.nfhs.org/hstoday

demonstrating that each dollar raised through public funding, par-

ticipation fees, game admissions or concession sales is utilized in a re-

sponsible manner. Costs associated with each sport should be

tabulated and calculated on a cost-per-pupil basis. Delivering pro-

grams at the same or reduced costs on a yearly basis will demon-

strate to district leadership that the athletic program is operating in

an efficient manner. When circumstances such as purchasing nec-

essary safety equipment or unanticipated expenses dictate a cost in-

crease, these changes should be documented in writing.

Document honors earned by student-athletes

Non-statistical data can help the athletic administrator make the

case for a school’s program as well. The publicity generated by stu-

dent-athletes who are recognized in the print and electronic media

is positive for the school as a whole. Athletic administrators should

document and archive all honors earned by participants in their pro-

grams and file reports as needed. This information should be promi-

nently documented on the school’s athletic Web site and updated

regularly as necessary. For purposes of fairness, inclusion and Title IX

compliance, all activities should be displayed equitably.

Document and publicize community service activities

conducted by interscholastic athletic teams

Interscholastic athletic programs offer a myriad of learning expe-

riences for participants. School athletic teams enrich the life of their

communities in many ways. When adopting a charity, volunteering

at a soup kitchen or officiating a youth basketball game, student-

athletes learn the importance of service to others. Athletic adminis-

trators should document these types of service projects and publicize

them to key decision-makers in the school system. Illustrating that

community service is as ingrained in the culture of the athletic pro-

gram as is competition provides a strong argument that athletics is

an indispensable part of the overall educational program.

Minimize the loss of academic time when scheduling

Supporting a school’s educational purposes requires the athletic

director to schedule events responsibly. Classroom teachers become

frustrated when students involved in athletics miss class time to par-

ticipate in an athletic event. Whenever possible, game times should

be scheduled so that bus departures occur after the dismissal bell.

There are occasions when daylight considerations or state-man-

dated playoff games necessitate mid-afternoon start times and early

dismissals for student-athletes. When those circumstances arise, the

athletic director should communicate the names of all affected stu-

dent-athletes in a timely manner and support teachers’ academic ex-

pectations. When early departures are the exception, not the custom,

and athletic administrators communicate all pertinent in-

formation, classroom teachers are generally supportive.

Collect feedback from alumni to demonstrate

how athletics has positively impacted their

lives

Graduates of the school are some of the most ardent

supporters of athletics. An athletic administrator should

initiate and maintain contact with alumni and collect in-

formation as to how participation in interscholastic sports

impacted them personally and professionally. Anecdotal

data about how the educational values instilled through

competition have shaped the experiences of graduates

can be used as a justification for maintaining programs,

even when budgets are lean. Given that many alumni

may still reside in the community and pay taxes, these

individuals may become important allies during chal-

lenging times.

Of course, there is no guarantee that any or all of these strategies

will work under all circumstances. A community experiencing wide-

spread unemployment or a major taxpayer revolt will create prevail-

ing winds that will be difficult for the athletic director to navigate.

What is certain, however, is that interscholastic athletics is com-

peting with a host of other programs for limited financial dollars. It

is incumbent upon every athletic director to understand and articu-

late the role that school sports programs play in the educational

process and to support that stance with clear data. The fruit of one’s

labor in collecting measures of how school sports have impacted stu-

dent success in the classroom and later life may be the preservation

of the interscholastic athletic experience for future generations of

youngsters to enjoy.

Gary Stevens, CMAA, is the athletic administrator at Thornton Academy in Saco,

Maine.

18

High School Today | October 11

East Carteret High School, located in Beaufort, North Carolina,

is a 1A school in the eastern part of the state. Approximately one-

fifth of the students are consistently involved in the annual musi-

cal production or enrolled in theatre arts. Community members

and feeder students enthusiastically anticipate what has become a

local fixture.

There are many aspects to building and sustaining a successful

theatre program, and the following suggestions should be helpful

as schools develop these kinds of performing arts programs:

• Be willing to spend money. Licensing costs, script pur-

chase/rental, building supplies, costumes, snacks for actors,

water for backstage, printing costs and supplements for

adults/staff not paid all add to the cost of pulling off major

shows. Don’t be afraid to spend some money for a quality and

worthwhile production.

• Find the best ways to raise money. Whether through

fundraising, donation drives or fees, be prepared to supplement

your budget. Offering ads in your program can be a great in-

centive for local businesses to donate. Charging a flat fee for

participation in theatre should be a last resort. A donation drive

will help students learn valuable communication skills and gen-

erate a vested interest from your community.

• Schedule one big “blockbuster.” One big musical or family

show can support the rest of your program for the school year.

• Run for two consecutive weekends. Following a successful

opening weekend, word of mouth will generate interest for the

remaining shows. You also get more life out of sets, costumes

and other purchased/rented materials.

• Ask for help. Don’t be afraid to let your faculty, community

members and especially your parents know you need help and

appreciate their talents. A successful program cannot be run by

one or two people, no matter how hard-working and dedicated.

• Accept help. Even if it means giving up a little control. See

above.

• Have open auditions. Have a least one large production that

is open to everyone. The lack of requirements and preset ex-

pectations will encourage more students to give theatre a

chance.

• Find a spot for everyone. If a student has the nerve to audi-

tion and the determination to come to rehearsals, find a spot for

that student in your cast or crew. These are the students who

will be the backbone of your program because they “want” it

and are willing to work for it.

• Know your audience. For your large, “money-making” pro-

ductions, know what your community will pay to see. Know the

script rating. Don’t advertise a PG-13 or R script to your area

families.

• Do not skimp on sets. You can go with the minimum, but put

as much effort and attention to detail into them as you would

your multi-level revolving pieces. Poorly designed, constructed or

painted sets can ruin an otherwise strong performance.

• Reuse and recycle. Last year’s sets can be taken apart and re-

built. Wood is expensive, as are wheels, hinges, etc. Find a place

on campus or a local storage company that will work a deal to

store your materials.

• Put any extra money back into your program. Set a goal to

end the season with as much money in your account as you

started. Any extra should be set aside for improvements to your

equipment or additions to your prop closet.

• Put your money into sound. If you can’t hear the actors or

singers, it doesn’t matter how good they are. Invest in a good

wireless system and keep your equipment in good shape.

• Do as much “in house” as possible. From printing your pro-

grams, to making your costumes, props and sets, it is usually

more cost-effective to do it yourself.

• Leave safety to the experts. Unless you have the technical

skill, find the parents who are electricians and contractors. Leave

the big stuff, such as flying rigs, to experts.

• Make your tickets affordable. Set a price that will not ex-

clude members of your community. Offer reserved seats at a

high price for a one-third of your seating and general admission

for the remaining seats. Consider breaking down pricing for

In the Limelight: Sustaining

a Successful Theatre Program

BY JENNIFER GREEN

PERFORMING ARTS

19

NFHS | www.nfhs.org/hstoday

general admission with students/children getting in for less.

Lower ticket prices may lead to repeat visits to your longer run-

ning performances. Consider free admissions and donations for

smaller productions (especially one-night events.)

• Give back to your community. Pursue partnerships with local

events or charities. Costumed actors can liven up almost any

event.

• Set high expectations. The expectations of the director and

other adults will become the expectations of the actors, crew

and business team. Expect perfection. Don’t let actors be seen

in costume before the show or during an intermission. Don’t

allow gum or food in acting areas. Don’t settle for “good

enough.”

• Advertise. Get to know the public relations person in your

county or district. Send e-mails and invitations to other

schools/faculties to promote your event. Invite local newspapers

or TV reporters to a dress rehearsal. Help promote your charity

involvement with posters, flyers or in-school news shows and/or

announcements.

• Offer discounts. Offer free, opening-night admission to fac-

ulty and staff in your district. Many schools start their runs on a

Thursday night to get the “jitters” out before the weekend. Free

tickets for faculty/staff will help fill your seats with an apprecia-

tive audience.

• Schedule preview shows. No matter the size, length or run of

your show, it’s always helpful for you and your actors to pre-

view some or even all of your show to a small audience willing

to provide constructive feedback.

• Put academics first. Never forget that academics come before

any extracurricular drama programs or events. Know how your

students are performing in the classroom as well as in the the-

atre. Encourage them to bring homework to rehearsal. There is

often spare time to knock out some homework. Also, encour-

age them to form study groups within the cast.

• Be willing to share your students. Depending on the size of

your school and the interests of your cast and crew, very few of

them will be involved only in theatre. Drama students are also

student-athletes, student government leaders, club members

and academic scholars. Finding a way to share and work to-

gether as a school is vital to the success of everyone involved.

• Thrift costumes. Thrift your costumes whenever possible. Tak-

ing a full day to drive from thrift store to thrift store – cast meas-

urements in hand – can save hundreds of dollars in costumes.

At the end of the run, keep the costumes, sell them to your sen-

timental cast members or donate them to the thrift store or

other local charity organization.

• Have a costume/prop room. Space permitting, keep all of

your old costumes, props, shoes, wigs, etc. A fully-stocked cos-

tume room can carry you through smaller productions without

having to make, rent or buy more costumes. For repeat per-

formances such as annual holiday-themed events, you will have

your costumes and accessories available from year to year.

• Keep good records. Good financial records will help you make

the most of your money, and being able to re-order hard-to-

find theatrical items will save time and money over the years.

• Have fun. If you and – more importantly – your students are

having fun, and your audiences are entertained, you have a suc-

cessful theatre program.

In her sixth year as the drama director and eighth year as an English teacher at East

Carteret High School in Beaufort, North Carolina, Jennifer Green is responsible for

teaching all theatre classes, directing the school musical and advising the Thespian

Society. With the help of her husband, Tim, a middle school math teacher and former

engineer, and choral instructor Shannon Ehlers, Green designs and builds the sets for

annual productions and helps her students continually give back to their community

through annual charity events.

20

High School Today | October 11

The job of a high school contest offi-

cial is not exactly easy. It is an avocation

where the noble recognition deserved for

overseeing a well-regulated athletic con-

test is almost always trumped by the crit-

icism and heckling of fans after a single

missed call or judgment on the field.

But few will argue the call that a

Michigan officials organization is making

to ensure that the future of children’s

health care is in good hands for years to

come.

The team is called “Officials For Kids,”

a group of mid-Michigan officials who are

dedicated to improving children’s health care at every Children’s Mir-

acle Network Hospital in the state of Michigan. The program was

founded in 2003 by Ken Sudall, the owner of Go Green Auto Glass

and a retired umpire who got the idea after developing a commu-

nity service relationship with Sparrow Hospital in the Lansing area.

“When I opened my company, we wanted to get involved in the

community, so we chose Sparrow Hospital’s children’s ward,” Sudall

said. “I soon became aware of its Coaches and Athletes program,

and I realized that you can’t have an athletic contest without

coaches, athletes and the third part being officials. So that’s where

I got the idea for Officials For Kids.”

Sudall began promoting his organization by parking cars at the

state basketball tournaments and a local festival called “Common

Ground.” With help from the Michigan High School Athletic Asso-

ciation (MHSAA), Sudall was soon able to promote his program on

a much larger scale, as the Officials For Kids name has now spread

to officials associations in Detroit, Flint and Grand Rapids.

The program’s most recent fundraising effort is an idea known

as “Give-A-Game,” a charitable project that the Lansing and Grand

Rapids associations have adopted that designates the first Thursday

in May as a day when all baseball and softball umpires donate game

fees to their local hospitals.

“We get a tremendous response whenever we do this,” Sudall

said. “We are part of this community and we want people to know

that we are willing to give back.”

But the giving does not stop there. MHSAA Communications

Director John Johnson said that while the Lansing and Grand Rapids

officials associations were the first to promote the Give-A-Game

trend, Flint, Detroit and other surrounding areas all have their own

unique ways of contributing. In Flint, an activities camp was held

for kids who are at high risk for obesity, while in Detroit, a group

launched a “Referees For Reading” program in which referees visit

hospitals and read to children.

“There is a lot of good stuff going on,” Johnson said. “I know

in Grand Rapids they also held an activities camp for visually im-

paired children where they get to do bike-riding, horse-riding and

things like that. The West Michigan Officials Association also did a

Give-A-Game night with football. It’s very fun stuff.”

Sudall said that there are approximately 13,000 registered offi-

cials in the state, all of whom who have participated in his program

in some way.

“All of them have participated at some point in time, but our

goal is to get all of them participating at the same time,” Sudall

said. “We have a group of umpires who have done the Give-A-

‘Officials for Kids’ Program

Makes the Right Call

BY EAMONN REYNOLDS

ABOVE AND BEYOND

21

NFHS | www.nfhs.org/hstoday

Game for years now, but our goal is to have the associations across

the state step up as well.”

For such a novel idea, the results have been nothing but positive.

According to Sudall, the various methods of contribution by Officials

For Kids have raised between $300,000 and $400,000, and the

Lansing-area officials continue to generate $15,000 to $20,000 an-

nually through their respective programs.

“We’re only a small part of the overall success,” Sudall said.

“We’re the blue-collar part. We’re the nickels and dimes.”

Johnson added that the only thing more important than the suc-

cessful fundraising is the constructive feedback he has seen and

heard from officials, parents and schools, emphasizing that keeping

the program local has been imperative.

“The buy-in from everyone has been huge, especially when they

hear that this is something that is going back to a place that’s local,”

Johnson said. “Schools are more than happy to be involved, and

the people are happy to give because this is money that is staying

right here and is going exactly where it says it’s going to go.”

While Johnson said that he is not aware of such a program in

other areas outside of Michigan, he knows that there has been

some interest and that other states are inquiring about introducing

similar ideas.

“There has been some interest and I know it’s been talked about

in officials circles beyond the state of Michigan,” Johnson said. “But

this is something that people should want to be affiliated with. It’s

one of those things where it’s such a feel-good concept that you

can’t not want to step up and join.”

Sudall said that for the upcoming year, Officials For Kids will

work toward four specific goals. By the end of 2012, the organiza-

tion hopes to have all 13,000 registered Michigan officials pledge

$100 annually, institute a dedicated “Give-A-Game Day” per sport,

have every approved association in the state create a plan for in-

volvement and develop an approach to reach out to the other non-

registered sports officials in the state.

So far, the ruling on the field indicates that the program is on the

right track.

“All people really know about officials is he or she blew that

call,” Sudall said. “So, at least for the two hours during these games

or in the time they spend helping kids, we hope people will gain a

respect for all of our officials involved. Our overall goal is to let peo-

ple know that we stand for more than just the calls we make.”

Eamonn Reynolds was the summer intern in the NFHS Publications/Communications

Department and is a senior at Ohio University majoring in journalism and public rela-

tions.

22

High School Today | October 11

uring basketball practice in 2001,

14-year-old Katie Patrick went to

take a charge, fell backwards and

hit her head on the unpadded metal wall of

the gym, less than 4 feet from the end line.

Patrick sustained a traumatic brain injury

and later filed suit against the coaches, ath-

letic director and school district, settling for

a significant amount.

In order to provide a reasonably safe en-

vironment, most sport and recreational ac-

tivities require a certain amount of space

between the activity area and any obstruc-

tions such as walls, benches and equipment.

This space is commonly referred to as a

buffer zone or safety zone.

Numerous participants have been seri-

ously or catastrophically injured, and some

have died, by running into walls and other

obstructions that are close to the court (Steinbach, 2004). Buffer-

zone accidents are one of the most common causes of serious in-

juries related to basketball. As a result of many of these injuries,

lawsuits were filed claiming that teachers, coaches, school boards

and other service providers were negligent in the conduct of their

programs.

A recent analysis of lawsuits that claim negligence in the con-

duct of sport and physical activity programs (Dougherty, 2006) re-

vealed that the lack of a sufficient buffer zone was alleged to have

been the primary cause of injury in 67 percent of basketball law-

suits. Buffer-zone injuries occur from time to time, but because

these injuries typically receive only local coverage, many people un-

derestimate the potential for such incidents in their gym.

Oriana Bruno was chasing a loose ball during high school bas-

ketball practice, accidently stepped on the ball and was propelled

headfirst into the concrete wall less than 6 feet from the end line,

sustaining traumatic brain and shoulder injuries. The wall was par-

tially padded, extending 9 feet on either side

of the center line of the court, but Oriana

hit the wall a couple of feet beyond the

padding. The Brunos later filed suit against

the school, settling for a significant amount.

In 1997, eighth-grader Lamar Pope was

playing basketball during open gym. The

cross-courts were being used when Lamar

tripped on another boy’s feet and went

head-first into the gym wall less than 5 feet

from the end line. Lamar was unresponsive

for several days, and passed away when he

was removed from life support.

Many current basketball facilities were

built with inadequate buffer zones, pre-

senting a dangerous condition from the day

they opened. Architects often do not un-

derstand the importance of designing courts

that incorporate adequate buffer zones and

wall padding. Even as athletes continue to become bigger, stronger

and faster, little is being done to protect them as they leave the

court out of control.

The following are recommendations regarding

basketball buffer zones:

1. Rule 1-2-1 of the National Federation of State High School

Associations Basketball Rules Book says “there shall be at

least 3 feet (and preferably 10 feet) of unobstructed space

outside boundaries.” In addition, Table 1-1 (Supplement to

Basketball Court) states the following: “If possible, building

plans should provide for a court with ideal measurements as

stated in Rule 1-1, ample out-of-bounds area and necessary

seating space. A long court permits use of two crosswise

courts for practice and informal games.”

2. The American Alliance for Health, Physical Education, Recre-

ation and Dance (AAHPERD) recommends at least 10 feet of

Basketball Buffer Zones:

Accidents Waiting to Happen

BY TODD L. SEIDLER, PH.D.

D

23

NFHS | www.nfhs.org/hstoday

clear

space

beyond the

end lines with

a very minimum

of 6 feet with full wall

padding (Sawyer, 2009).

It also specifies at least 6

feet along the sidelines. All new

basketball courts should be

planned and constructed with ade-

quate buffer zones in mind. Remember,

sidelines for the main court sometimes become the end lines

for the cross-courts and many of the previous injuries oc-

curred on the cross-courts. Those playing on cross-courts

are no less entitled to a safe environment.

3. For existing courts with inadequate buffer zones, pad the

walls. The American Society for Testing and Materials

(ASTM) recently released standards for wall pads. When pur-

chasing wall pads, specify that they meet or exceed the

ASTM standard. With courts that have a buffer zone of less

than 3 or 4 feet, investigate the possibility of re-striping the

court and moving the baskets in, thereby increasing the

buffer zone. It is better to have a court that’s a little short

than a kid with a serious injury – or worse.

4. The gym walls should be padded the entire width of the

court, from no more than 4 inches off the floor to a height

of at least 6 feet. Ideally, the gym walls should be com-

pletely padded (wall to wall). The reason for padding wall to

wall is that, in most gyms, many activities take place other

than basketball. If a physical education class is playing Ulti-

mate or the softball team is running sprints, the lines for the

basketball courts may be meaningless, but the wall is just as

hard.

5. Keep the buffer zone clear of obstructions such as benches,

tables, chairs, spectators, etc. A bench

or other object too close to the court be-

comes a hazard for someone out of control.

Inadequate buffer zones and wall pads present

a foreseeable risk of injury and many such injuries con-

tinue to occur across the country each year. Act now to

possibly save one of your students from a preventable, poten-

tially serious or catastrophic injury. Providing adequate buffer zones

and padding is good risk management.

References and Suggested Reading

Appenzeller, H. (2005). Risk management in sport: Issues and

strategies. (2nd ed.). Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press.

ASTM International. (2005). F2440-04: Standard specification for

indoor wall/feature padding. In ASTM book of standards. (vol. 15-07).

West Conshohocken,PA: Author.

Dougherty, N. (2006). Negligence claims in the 21st century: Who’s

suing whom and why? Safety Notebook, AAPAR, 11(7), 2.

Dougherty, N. & Seidler, T. (2007). Injuries in the buffer zone: A se-

rious risk-management problem. Journal of Physical Education Recre-

ation and Dance, 78(2), 4-7.

Fried, G. B. (1999). Safe at first. Durham, NC: Carolina Academic

Press.

Sawyer, T. (2009). Facility planning and design for health, physical

activity, recreation and sport. (12th ed.). Champaign, IL: Sagamore.

Seidler, T. (2005). Conducting a facility risk review. In Appenzeller,

H. Risk management in sport: Issues and strategies. (Second Ed., pp.

317-328). Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press.

Seidler, T. (2006). Planning and designing safe facilities. Journal of

Physical Education Recreation and Dance, 77(5), 32-37, 44.

Seidler, T. & Martin, N. (2008). Safety of basketball buffer zones:

Perceptions of sport risk management experts. Presented at 2008 Sport

and Recreation Law Association Conference. Myrtle Beach, SC.

Steinbach, P. (2004). Sudden impact. Athletic Business, 28(3), 51-

58.

Steinbach, P. (2006). Zone offense. Athletic Business, 30(4), 75-77.

Todd R. Seidler, Ph.D., is professor of sport administration at the University of New

Mexico in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

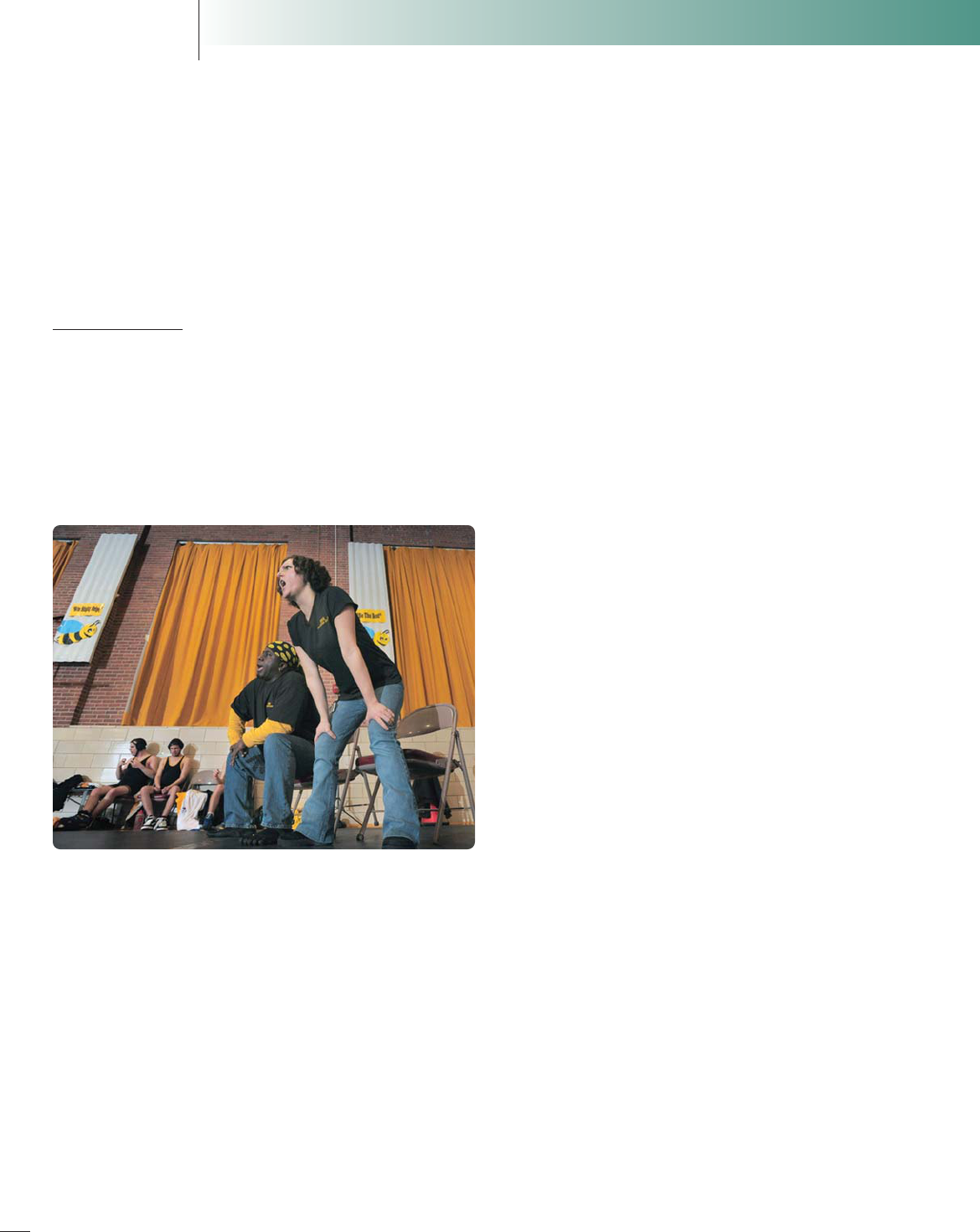

The “C” emblem on an athlete’s chest conveys the same mes-

sage to his or her teammates as what it stands for: Captain. Such

a role signifies leadership, sportsmanship and, above all, character

– three qualities that separate great young men and women from

the middle of the pack. In North Carolina, high school athletic pro-

grams across the state are not only striving to provide their stu-

dent-athletes with these tools to succeed, they are watching them

bloom firsthand in their communities.

Every spring, the North Carolina High School Athletic Associa-

tion (NCHSAA) hosts its Coaches and Captain Retreat in Raleigh, a

weekend leadership-development program that brings together

student-athletes, coaches and parents from high schools through-

out the state. The goal of the program is to train those student-ath-

letes who are team captains – or have potential leadership skills to

be captains – and teach them effective ways to communicate in a

leadership role.

“The curriculum is designed to teach them what their respon-

sibilities are as team leaders,” said Mark Dreibelbis, NCHSAA as-

sistant commissioner for student services and supervisor of officials.

“The teaching then goes on to prepare them to go back and make

a difference.”

The program has been funded by the North Carolina legislature

for the past 16 years, and is a part of the NCHSAA’s Student Serv-

ices department. According to Dreibelbis, every school is allowed to

participate in the weekend retreat and is responsible for submitting

the names of all student-athletes, coaches and parents who plan on

attending. Once they arrive, the student-athletes are separated into

groups with other student-athletes from different schools.

“They learn to interact with one another through a range of

different projects,” Dreibelbis said. “The projects deal with issues

in their own schools, such as sportsmanship, bullying and hazing,

and community service.”

After a day-and-a-half of group planning and decision-making,

each school must develop an action plan – an initiative Dreibelbis

24

High School Today | October 11

North Carolina Captain Retreat Program

Teaches Leadership, Communication

BY EAMONN REYNOLDS

IDEAS THAT WORK

“The teaching then goes on

to prepare them to go back

and make a difference.”

25

NFHS | www.nfhs.org/hstoday

said must include a school-based project, a public-service an-

nouncement and a community project. When students implement

their action plans into their schools, the NCHSAA helps provide

funding for school activities.

“Everything they do ties back into our main objectives for the

program,” Dreibelbis said. “Our objectives are to define leadership

qualities in a team captain, identify key issues affecting student-

athletes, teach them to communicate effectively with other stu-

dents and adults, and to understand how they can use their

influence to prevent problems and promote healthy lifestyles.”

The success of the retreat is indisputable. In fact, Dreibelbis

noted that this past year, the program’s message about sports-

manship and positive behavior reached 17,693 students and

908,495 adults, as recorded by the NCHSAA.

“We want them to address problems they are witnessing in

their schools,” Dreibelbis said. “These numbers represent pro-

gramming and persons who received the programming through

the myriad of projects and programs coordinated by our Coach

and Captain teams and members.”

While the emphasis of the retreat is specifically geared toward

the growth of the student-athletes, Drebelbis said that the real suc-

cess of the program actually comes from the parents who partici-

pate.

“With the parents being there, they really help in terms of tak-

ing this back to the communities and schools,” Dreibelbis said.

“They don’t just do it for their team; they do it for their communi-

ties and their kids’ schools.”

Dreibelbis sees the retreat as a hands-on, interactive program

that will continue to attract more and more schools in years to

come. He said that while nearly all of the schools return after par-

ticipating in the retreat, he receives requests from new schools

every year looking to join in the experience.

“We try to empower the student-athletes,” Dreibelbis said.

“We tell them, ‘you can make the difference.’ As athletes and team

captains, so much is expected of them, so our program gives them

the knowledge and confidence to actually go out and make that

difference. That’s the beauty of it.”

Eamonn Reynolds was the summer intern in the NFHS Publications/Communications

Department and is a senior at Ohio University majoring in journalism and public rela-

tions.

Since 1987

ds

rd

Quality

Custo

m A

war

ds

26

High School Today | October 11

ith the start of the high school field hockey season,

one noticeable change has occurred in the 14 states

that sponsor the sport. All players throughout the na-

tion are now required to wear protective eyewear on the field dur-

ing competition.

The National Federation of State High School Associations

(NFHS) Board of Directors voted at its April meeting in Indianapo-

lis to mandate the use of protective eyewear that meets the current

American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) standard for

field hockey. Acting on a recommendation from the NFHS Sports

Medicine Advisory Committee, the Board agreed that the potential

risk of injury warranted the requirement of protective eyewear for

the 64,000 student-athletes involved in the sport.

“While serious eye injuries in field hockey at the high school

level are rare, the NFHS Board of Directors has concluded that an

eyewear requirement is the right step,” said Elliot Hopkins, NFHS

director of educational services and field hockey rules editor.

For sports similar to field hockey, mandatory eye and face pro-

tection is the undisputed norm. Girls and boys lacrosse and ice

hockey all require helmets, facemasks or goggles to be worn at all

times. Ultimately, the Board’s goal is to minimize risk for players, an

initiative that Hopkins is certain the rule will accomplish.

“In field hockey, not too many people associate the sport with

face or eye injuries,” Hopkins said. “However, that really only ap-

plies to those athletes who play the sport at a much higher level.

In high school, these are amateur athletes, so the risk for injury is

significantly greater.”

Since the passage of the rule in April, some coaches and play-

ers have voiced their disapproval, believing that eyewear will affect

players’ peripheral vision and reduce the quality of their perform-

ance. Some individuals believe that eyewear also takes away from

the traditional aspects of the sport.

Although the eyewear mandate is now in place for all high

schools nationally, five states (Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts,

Rhode Island and Vermont) previously passed rules on their own to

require protective eyewear. Maine Principals’ Association (MPA) As-

sistant Director Mike Burnham believes that it was necessary to

make the rule a national standard.

“It is my feeling that if a rule such as the mandatory wearing of

eyewear promotes student safety and may save an athlete’s eye,

then it is a rule worth having in place at the national level,” Burn-

ham said.

NFHS official field hockey rules previously allowed – but did not

require – the wearing of eyewear that meets the current ASTM

State Associations Defend

New Field Hockey Eyewear Rule

BY EAMONN REYNOLDS

Photo provided by Bob Russell, Maryland.

W

27

NFHS | www.nfhs.org/hstoday

standard. Tom Mezzanotte, executive director of the Rhode Island

Interscholastic League, said that states must always put safety of

the student-athletes first in any sport, even when it comes to rules