Bureau of Justice Statistics

U.S. Department of Justice

Office of Justice Programs

Improving Access to and

Integrity of Criminal

History Records

Achievements of the National Criminal

History Improvement Program

Missing dispositions in criminal history

records

Opportunities for improving background

checks

U.S. Department of Justice

Office of Justice Programs

810 Seventh Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20531

Alberto R. Gonzales

Attorney General

Office of Justice Programs

Partnerships for Safer Communities

Regina B. Schofield

Assistant Attorney General

World Wide Web site:

http//www.ojp.usdoj.gov

Bureau of Justice Statistics

Lawrence A. Greenfeld

Director

World Wide Web site:

http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/bjs

For information contact

National Criminal Justice Reference Service

1-800-851-3420

U.S. Department of Justice

Office of Justice Programs

Bureau of Justice Statistics

Improving Access to

and Integrity of Criminal

History Records

Peter M. Brien

Bureau of Justice Statistics

July 2005, NCJ 200581

U.S. Department of Justice

Office of Justice Programs

Bureau of Justice Statistics

Lawrence A. Greenfeld

Director

Peter M. Brien, Statistical Policy Advisor, BJS, wrote this

report. Todd D. Minton, BJS Statistician, verified the

findings. Tina Dorsey produced the report, and Tom Hester

edited it.

Office of Justice Programs

Partnerships for Safer Communities

Contents

Achievements of the National Criminal History

Improvement Program 1

Missing dispositions in criminal history records 9

Opportunities for improving background checks 19

Appendix I. Identifying prohibited purchasers:

The mentally ill 25

Appendix II. Identifying prohibited purchasers:

Domestic violence misdemeanants and subjects

of restraining orders 33

Appendix III. BJS surveys in the aftermath

of September 11, 2001 39

ii

Improving Access to and Integrity of Criminal History Records

NCHIP overview

The National Criminal History Improve-

ment Program (NCHIP) represents a

close collaboration among the Bureau

of Justice Statistics (BJS), State crimi-

nal justice agencies, and the Federal

Bureau of Investigation (FBI). Since

1995, this collaboration has improved

the nation's public safety by enhancing

and upgrading the States' criminal

history records which are used for

background checks for firearms

purchases, pre-employment checks for

certain sensitive professions, criminal

sentencing decisions, and many other

purposes. The NCHIP program has

facilitated the development of a

national network of State criminal

records which is available to State and

federal law enforcement officials.

The program has provided direct finan-

cial and technical assistance to States

to develop and upgrade their criminal

record information systems — includ-

ing records of protection orders, sex

offender registries, and automated

fingerprint identification. NCHIP has

been instrumental in making these

records accessible on an interstate

basis through FBI administered

systems —

• the National Instant Criminal

Background Check System (NICS)

• the Interstate Identification Index (III)

• the National Protection Order File

• the National Sex Offender Registry

• the Integrated Automated Fingerprint

Identification System (IAFIS).

Since 1995 BJS has awarded nearly

$400 million to States and Territories.

During the period of funding the

number of criminal history records has

increased 29% nationwide, and the

number of automated records available

for immediate use by law enforcement

increased 35%.

As of December 31, 2001, there were

nearly 64.3 million subjects in State

criminal record files, and 89% of these

records were automated.

This highlights section presents an

overview of 11 performance measures

for NCHIP:

• Millions of background checks are

supported by the NICS

• The percentage of State criminal

history records which are automated

has improved

• The number of records that are

shareable through the FBI’s III has

increased

• The number of States participating in

III has increased

• More law enforcement agencies are

reporting arrest information

electronically

• The number of States participating in

the FBI’s IAFIS has increased

• More courts are transmitting

automated dispositions

• Criminal history information process-

ing has become more efficient

• The National Protection Order File

has significantly expanded

• The National Sex Offender Registry

has reached record levels

• NCHIP has established a framework

to assist in Homeland Security.

These measures summarize how

NCHIP has assisted States in improv-

ing criminal history record complete-

ness and automation.

The National Instant Criminal

Background Check System (NICS)

supports millions of background

checks

NCHIP funds have supported State

efforts to conduct rapid and efficient

checks under the NICS. In 2001, the

NICS supported nearly 8 million checks

at the presale stage of firearms

purchases.

Assisted by NCHIP funding, the State

NICS infrastructure made the transition

from an interim system to the current

permanent system. Under the interim

Brady system, the chief law enforce-

ment officer conducted checks.

Currently States operate background

check systems of their own (Point-of-

Contact States or POC States), rely

exclusively on the NICS, or do both.

From the inception of the Brady Act on

March 1, 1994, to December 31, 2001,

nearly 38 million applications for

firearm transfers were subject to

background checks.

Achievements of the National Criminal History Program

Improving Access to and Integrity of Criminal History Records

1

Data sources for measuring

access to and integrity of

criminal history records

Almost a decade before the incep-

tion of NCHIP in fiscal year 1995,

BJS formed a partnership with the

States and the FBI to improve the

accuracy and accessibility of criminal

history records. After passage

of the Brady Act, expanded use of

those records enlarged both BJS'

role as administrator of funds to

improve record systems and BJS'

role as statistical monitor to meas-

ure efficiency and completeness.

The following provided data for this

report:

• Since 1989 BJS has funded the

biennial Survey of Criminal History

Information Systems, conducted by

SEARCH, The National Consortium

for Justice Information and Statistics.

• In 2001 and 2002 BJS initiated

research with the Regional Justice

Information Service (REJIS) and

SEARCH. These collaborations

addressed issues related to the

completeness and accuracy of crimi-

nal history records, mental health

records, restraining orders, and

misdemeanor domestic violence

records.

• Upon passage of the Brady Act

and creation of NCHIP, BJS initiated

the Firearm Inquiry Statistics

program as part of NCHIP. The

program operates through a

cooperative agreement with REJIS.

Of the nearly 8 million checks

conducted in 2001, 98% of applicants

were approved whether the check was

conducted by the State or the FBI

(figure 1).

1

There are two principal ways to evalu-

ate the performance of the background

check system:

• Examine the percentage of appli-

cants for a firearm purchase who were

incorrectly prohibited (Error I)

• Examine the percentage of persons

who were allowed to purchase a

firearm who should have been prohib-

ited from doing so (Error II).

Error I can be measured by calculating

the ratio of successful appellants of a

rejection to the total number of appli-

cants to purchase a firearm. In 2002

there were 9,500 successful appeals of

rejections from among the 7,806,000

applicants that year. This translates

into an error rate of 0.1%.

Error II can be measured by calculating

the ratio of firearm retrievals by law

enforcement to the total number of

applicants to purchase a firearm. In

2002 there were 7,400 retrievals due to

an incorrect sale to a prohibited

purchaser against a total of 7,806,000

applicants. This also translates into an

error rate of approximately 0.1%.

Among the 136,000 applicants rejected

as prohibited purchasers during 2002,

8 in 10 did not appeal the rejection.

Among those who filed an appeal,

almost 6 in 10 rejection decisions were

sustained.

Levels of State criminal record

automation have increased

There have been notable improve-

ments in the automation of State crimi-

nal history records since 1995 (figure

2). As the number of criminal records

has increased in recent years, the

NCHIP program has helped the States

to ensure that levels of automation

remain high. In 2001, 30 States had at

least 90% of their criminal history

records automated, compared to 22

States in 1995.

The number of States with relatively

low levels of automation (defined as

having less than 70% of records

automated) declined from 13 States in

1995 to 6 States in 2001.

2001 represents the first year in which

more than half of the States (27)

indicated that 100% of their criminal

history records were automated. In

1999, 21 States reported having 100%

automation, as did 18 States in 1995.

2

Improving Access to and Integrity of Criminal History Records

Checks conducted

by NICS

4,248,900

Number of denials

reversed

6,300

Number of denials

appealed

13,500 (18%)

Number of denials

not appealed

61,800 (82%)

Number denied

for purchase

75,200 (2.1%)

Number approved

for purchase

3,481,700 (97.9%)

Number of denials

reversed

3,200

Number of denials

appealed

10,400 (17%)

Number of denials

not appealed

50,300 (83%)

Retrievals due to

erroneous sale

3,400

Retrievals due to

erroneous sale

4,000

Number of firearm

purchase applicants

7,806,000

Checks conducted

by POC's

3,556,900

Number denied

for purchase

60,700 (1.4%)

Number approved

for purchase

4,188,200 (98.6%)

Figure 1

Sources: BJS; Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives; and the NICS Program Office of the FBI

1

This 2% rejection rate is consistent with the

rejection rates from 2001, 2000, 1999, and 1998

and during the interim Brady period from 1994 to

1998.

Number of records shareable

through the FBI's Interstate

Identification Index (III) has

increased

The number of Interstate Identification

Index (III) records maintained by the

States as compared to the records

maintained by the FBI is an important

measure of the decentralized nature of

the background check system. To

ensure that criminal history records are

compatible across all States, record

improvements funded by BJS under

NCHIP are required to conform to FBI

standards for III participation. BJS has

designated State participation in the III

as one of the highest priorities of the

NCHIP program.

From yearend 1993 to April 2003, the

number of State records available for

sharing under the FBI's III nearly

doubled from 25.5 million to 48.5

million. Since 1993 the number of

records available for III has been

increasing at a much faster rate than

the overall number of criminal records.

In 1993 half of all criminal history

records were III accessible, and 70%

were in 2001. It is projected that in

2005, more than three-fourths of all

criminal history records will be accessi-

ble through the III.

At yearend 2001, 22 States had at least

75% of their records accessible

through III, and 15 States had 50% to

74% of their records III accessible

(table above).

Number of States participating

in III has increased

As part of NCHIP's commitment to

achieving full State participation in the

FBI's III system, BJS has used the

NCHIP program to encourage all

States to make their records available

to the FBI and other States. In 1989,

20 States were members of the III

system. The number of participating

States grew to 26 in 1993. As of May

2003, 45 States were participating in III.

The application for NCHIP funds

requires nonparticipating States to

include a discussion of their III status

and a plan for future III participation.

Improving Access to and Integrity of Criminal History Records

3

Figure 2

(less than 70%)

(70-89%)

(90-100%)

1995 1997 1999 2001

0

10

20

30

Low

Med

High

Number of States

States with high, medium, and low levels

of criminal record automation, 1995-2001

High: 90-100% of criminal records automated

Medium: 70-89% of criminal records automated

Low: Less than 70% of criminal records automated

Wyoming

West Virginia

Virginia

South Dakota

South Carolina

North Carolina

Nevada

WisconsinNew Mexico

VermontWashingtonNew Jersey

TexasUtahNebraska

Rhode IslandTennesseeMontana

North DakotaPennsylvaniaMississippi

New HampshireOregonMinnesota

MassachusettsOklahomaMichigan

MaineOhioMaryland

LouisianaNew YorkIowa

KentuckyMissouriIdaho

KansasIndianaGeorgia

HawaiiIllinoisFlorida

District of ColumbiaDelawareColorado

ConnecticutArkansasCalifornia

AlabamaAlaskaArizona

States with less than 50%

of records III-accessible

States with 50-74%

of records III-accessible

States with at least 75%

of records III-accessible

Percentage of criminal history records accessible through the

Interstate Identification Index (III), by State, December 2001

More law enforcement agencies are

reporting arrest information

automatically

State law enforcement agencies have

frequently relied on the NCHIP

program to help them transition from

ink-based fingerprinting systems to

electronic systems. From 1999 to

2003 NCHIP has provided States with

approximately $31 million for Livescan

systems and their participation in the

FBI's automated fingerprint system.

These systems allow fingerprints to be

scanned and instantly transmitted

electronically to criminal justice

agencies throughout the State or

Nation.

Among the 37 States reporting

complete data, the number of arresting

agencies that electronically transmit

arrest information and fingerprints

increased by more than 2,000 from

1997 to 2001 (figure 3). Nationwide,

2,594 agencies electronically submitted

arrest information in 2001, a substantial

increase from 493 agencies in 1997.

An increasing number of States

participate in the FBI's Integrated

Automated Fingerprint Identification

System (IAFIS)

NCHIP funds are available to all States

for the conversion to IAFIS. As of

March 2003, 43 States, the District of

Columbia, and 3 Territories participated

in IAFIS. In fiscal year 2002 NCHIP

distributed over $3.8 million to 19

States and the District of Columbia to

purchase equipment for the automatic

capture and transfer of fingerprint

images.

More courts are transmitting

automated dispositions

Whether the States can maintain

complete and accurate criminal history

records depends heavily on the ability

of the courts to report final dispositions

automatically to the criminal history

repository or court administrator’s

office. For several years NCHIP has

been committed to supporting the

record and case management systems

of State and local courts.

From 1997 to 2001 NCHIP funds

assisted nearly 725 courts to develop

the ability to report final dispositions

automatically (figure 4). As of yearend

2001, over 2,000 courts were reporting

disposition information electronically,

based on 25 States reporting complete

data.

As part of NCHIP's support for capture

of judicial decisions for criminal history

records, participating courts across the

United States have developed the

ability to —

(1) electronically link fingerprints and

other biometric information to disposi-

tions and share this information with

corrections and law enforcement

agencies

(2) provide electronic protection

order/restraining order files that can be

accessed by law enforcement officers

in the field

(3) establish and maintain sex offender

registries

(4) convert juvenile records to the adult

case management system

(5) establish databases of offender-

based information.

4

Improving Access to and Integrity of Criminal History Records

Figure 4

Figure 3

1997 1999 2001

0

500

1,000

1,500

2,000

2,500

3,000

Number of agencies

Estimated number of arresting

agencies reporting dispositions

by automated means, 1997-2001

0

500

1,000

1,500

2,000

2,500

Number of courts

1997 1999

2001

Estimated number of courts

reporting dispositions by

automated means, 1997-2001

Processing criminal history

information becoming more efficient

Since 1995 NCHIP has assisted States

in developing and implementing

integrated criminal history record

systems. Through NCHIP support, new

information technologies have enabled

State criminal justice agencies to share

critical information more efficiently.

The average time required for agencies

to transmit arrest information, final

court dispositions, and prison admis-

sions to criminal history repositories

has declined significantly since 1995

(figure 5). In addition, these reposito-

ries are processing and posting this

information more quickly than in 1995.

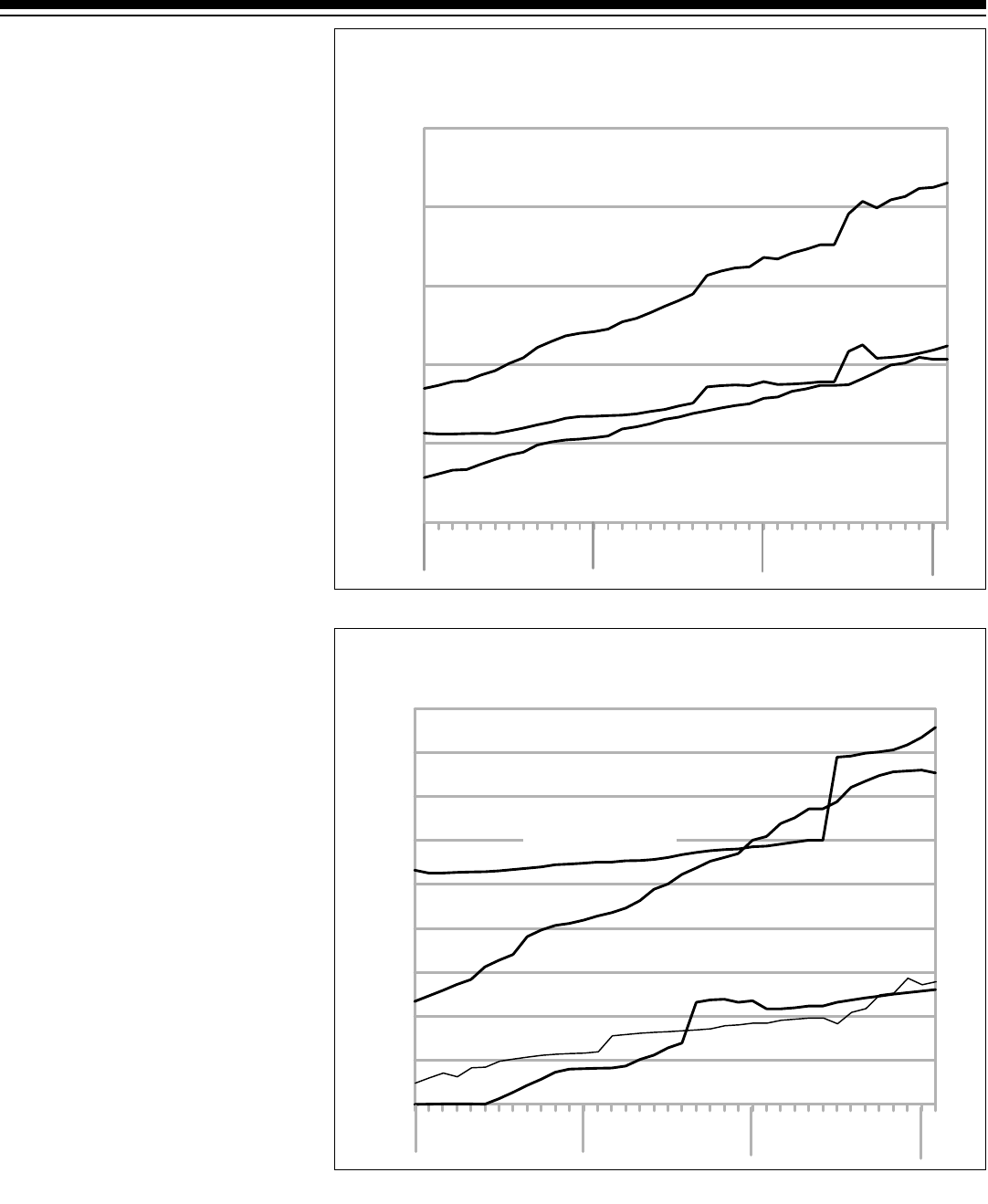

From 1995 to 2001 the average time

between an arrest and the addition of

fingerprints and information about that

arrest to a criminal history record was

cut nearly in half from 45 days to 24

days. The average time required to

receive, process, and add final court

disposition information to a criminal

history record declined more than 30%,

from 68 days to 46 days. In 1995 infor-

mation about an individual's admission

to prison took an average of 94 days to

be received and then posted to a

record. By 2001 this information was

processed 3 times faster, in 31 days.

Despite progress from 1995 to 2001,

not all States have adopted integrated

or automated systems for transferring

criminal history information. In 2001

States were still more likely to transmit

information through the U.S. Postal

Service than by electronic or online

transmissions.

The National Protection Order File

has significantly expanded

A 1994 amendment of the Federal Gun

Control Act made illegal the sale of

firearms to persons subject to a qualify-

ing protection order. A qualifying

protection order meets conditions that

refer to domestic violence. NCHIP has

placed special emphasis on ensuring

that domestic violence-related offenses

and protection orders are included in

criminal records. Funds have been

specifically awarded for development of

State protection order files that are

compatible with the FBI's national file,

NCIC National Protection Order File, to

permit interstate enforcement of

protection orders.

The National Protection Order File, the

fastest growing national set of criminal

history records maintained by the FBI,

has tripled in size since 2000 (figure 6).

On February 3, 2003, the National

Protection Order File held over 750,000

protection orders from 43 States.

Improving Access to and Integrity of Criminal History Records

5

1995 1997 1999 2001

0

20

40

60

80

100

Average number of days for repositories

Prison admission

Court disposition

Arrest information

to receive and process criminal history data

Average number of days required for repositories to receive

and process information, 1995-2001

Figure 5

Figure 6

Number of records

2000 2001 2002 2003

Jan Apr Jul Oct Jan Apr Jul Oct

Jan

Apr Jul Oct Jan

0

200,000

400,000

600,000

800,000

Number of files in the National Protection Order File, 2000-03

The National Sex Offender Registry

has reached record levels

Since 1998, the NCHIP program has

assisted States in establishing sex

offender registries which interface with

the FBI's National Sex Offender Regis-

try. This assistance has enabled State

sex offender registry information to be

obtained and tracked from one jurisdic-

tion to another.

The National Sex Offender Registry

has seen dramatic growth in recent

years, from nearly 50,000 records in

2000 to over 280,000 records in 2003

(figure 7). On February 3, 2003, the

National Sex Offender Registry

contained records from every State, the

District of Columbia, and 3 Territories.

NCHIP helped to create tools for

accomplishing the work of

Homeland Security

A signal contribution of NCHIP has

been to assist the States and the FBI in

construction of a nationwide network of

criminal history and fingerprint

archives. The contents can be

examined for both criminal justice

purposes (for example, presale

firearms checks) and noncriminal

justice purposes, such as employment

security clearances.

In 1992 State repositories held 36.4

million automated criminal history

records, and 4 States relied completely

on paper records. Since 1995 NCHIP

has assisted the States' transition

toward automation, so that in 2001

State repositories held 57.4 million

automated criminal history records.

As of March 1, 2003, there were 48.5

million criminal records that were

shareable through III.

6

Improving Access to and Integrity of Criminal History Records

Jan Apr Jul Oct Jan Apr Jul Oct Jan Apr Jul Oct Jan

0

50,000

100,000

150,000

200,000

250,000

300,000

Number of records

2000 2001 2002 2003

Number of records in the National Sex Offender Registry, 2000-03

Figure 7

Future challenges for NCHIP

With a history of success, the role of

NCHIP has evolved to support the

States in pursuing emerging technolo-

gies and new criminal justice priorities

as identified by Federal and Sate

policymakers.

According to the administrators of

NCHIP, there exist areas of opportunity

where Federal resources will continue

to be needed. Discussed in greater

detail in the following pages, these

future challenges for NCHIP include:

Updating relevant mental health

records — BJS has conducted

surveys to examine the status of

mental health records among the

States. Analysis of responses can help

to determine how NCHIP can further

enable States to make the information

in mental health records available for

background checks.

Improving access to records for

domestic violence misdemeanor

convictions — Since 1996, when

Congress added conviction for a

domestic violence misdemeanor to the

list of Federal firearm prohibitors,

NCHIP has worked with the States to

improve access to these records;

however, significant challenges remain.

Recent BJS surveys examined the

persistent impediments to accessing

these criminal records.

Ensuring that court disposition

reporting systems are automated —

All court disposition information should

be transmitted electronically using

established technologies. The automa-

tion of court dispositions will provide

complete and accurate information

electronically to Federal and State

criminal justice officials.

Encouraging prosecutors to

complete criminal history records

by reporting their declinations to

prosecute — When prosecutors

decline to prosecute arrestees,

frequently the declinations are not

added to the criminal records. Checks

of these records require significant

effort to discover whether the arrested

individual was prosecuted.

Converting older paper records into

an electronic format — Many State

criminal history record holdings contain

older records on paper. Full automation

awaits the entering of these records

into the system.

Linking criminal history transactions

with NIBRS incident reports — This

linkage allows criminal history records

to reflect a wealth of detailed informa-

tion concerning the nature and charac-

teristics of criminal incidents. Incident-

based information allows for better

informed decisions regarding criminal

punishment, crime control strategies,

and policy analysis.

Developing a uniform national crimi-

nal history format for RAP sheets —

Because of variation in criminal history

record formats among the States, the

interstate exchange and interpretation

of criminal history information are

unnecessarily complicated. The devel-

opment and adoption of a uniform

format for RAP sheets will make crimi-

nal history information more easily

understood across jurisdictions.

Continuing to address privacy and

confidentiality issues as they relate

to non-criminal justice background

checks — The Prosecutorial

Remedies and Other Tools to end the

Exploitation of Children Today Act of

2003 or PROTECT Act contains provi-

sions that will make it easier for private

organizations that work with children,

the elderly, or the disabled to conduct

background checks on volunteers.

The PROTECT Act established a pilot

program that permits volunteer organi-

zations to submit 100,000 requests for

background checks to Federal authori-

ties. States will want to ensure that

privacy and confidentiality protections

are respected as non-criminal justice

background checks become more

prevalent.

Improving Access to and Integrity of Criminal History Records

7

NCHIP goals

NCHIP remains committed to its

responsibility to provide Federal assis-

tance to State criminal justice record

systems. That bedrock commitment

remains as the program addresses

these challenges:

• Identify how NCHIP can be more

effective in promoting the use of State

mental health records during

background checks

• Create initiatives to remove impedi-

ments to the availability of conviction

records for domestic violence

misdemeanors

• Continue NCHIP efforts to introduce

technology into all courtrooms so that

disposition records will be transmitted

electronically to criminal history record

repositories

• Develop procedures to encourage

prosecutors to promptly report declina-

tions to the repositories

• Continue NCHIP's encouragement

of States to remove backlogs of paper

records

• Support the development and

adoption of a uniform RAP sheet

• Work with States to ensure that

privacy and confidentiality protections

are respected as background checks

for noncriminal justice purposes

become more prevalent.

In a 2001 survey, half the States

reported that from 10% to over 50% of

the arrests recorded in State databases

had no final disposition indicating how

the arrest was resolved. These arrests

that lack dispositions, known as “open”

or “naked” arrests, create substantial

problems for time-sensitive background

checks because conducting the neces-

sary research to complete the record is

often time consuming, labor intensive,

and costly.

BJS examined the scope of missing

dispositions as reported by the States

in a 2001 survey. Factors that contrib-

ute to missing dispositions include the

following:

• poor communication among the

courts, law enforcement, and correc-

tions agencies in providing final dispo-

sition information to the State reposi-

tory

• reliance on the mail and manual

research rather than on electronic

communication

• repository delays in posting disposi-

tion information to a criminal record

• persistent backlogs of criminal justice

records in criminal history repositories

• failure of States to audit their data-

bases to ensure record completeness

• varying definitions of “missing

dispositions” among States

• inconsistent procedures among

States for handling missing

dispositions.

Missing dispositions or “open

arrests” an extensive problem

In a 2001 survey, State repository

directors were asked what percentage

of arrests in their databases had final

dispositions recorded. Six States

reported that 90% or more of their

arrests had corresponding final disposi-

tions. Twenty-three States reported that

between 50% and 89% of arrests had

dispositions. In nine States less than

half of the arrests had final dispositions

recorded in the databases. Twelve

States and the District of Columbia

could not estimate the percentage of

arrests with dispositions.

The repository directors also reported

the percentage of arrests occurring

within the last 5 years (“recent arrests”)

that contained final dispositions. Eight

States reported that 90% or more of

their recent arrests had final disposi-

tions attached. Twenty States reported

that between 50% and 89% of recent

arrests had dispositions. In 12 States

less than half of the recent arrests in

their database had final dispositions

recorded. Ten States and the District

of Columbia could not estimate the

percentage of recent arrests with

dispositions.

Another measure of the missing dispo-

sition problem is the number of final

court dispositions in State files that can

not be linked to arrest or charging infor-

mation. In 2001, 14 States estimated

the number of unlinked court disposi-

tions. These States reported a total of

704,300 final court dispositions on file

that could not be linked to arrest or

charging information, an average of

over 50,000 unlinked dispositions per

State.

While 14 States estimated the

number

of unlinked final court dispositions, 16

States estimated the

percentage

of

final court dispositions in their files that

could not be linked to an arrest. Minne-

sota and Indiana reported that half of

their final court dispositions could not

be linked to arrest or charging informa-

tion. Wisconsin, Kansas, and Pennsyl-

vania reported that between 30% and

40% of their final court dispositions

were unlinked. In Michigan and

Nebraska a quarter of their final court

dispositions had no link to arrest or

charging information. The remaining

nine States (Georgia, Maryland,

Montana, Nevada, New York, South

Carolina, South Dakota, Utah, and

Virginia) reported that 10% or fewer of

their final court dispositions contained

no arrest or charging information.

Poor interagency communication

contributes to missing dispositions

Interagency communication can be

evaluated in three ways:

(1) by the number of days required for

the court, law enforcement agency, or

corrections agency to report disposition

information to the repository

(2) by the extent to which criminal

justice agencies rely on manual

systems rather than electronic systems

to transmit disposition information and

research missing dispositions

(3) by whether all criminal justice

agencies are fully aware of their report-

ing requirements.

Missing dispositions in criminal history records

Improving Access to and Integrity of Criminal History Records

9

Disposition data took over a week on

average to reach repositories

A leading reason why final dispositions

are not adequately linked to their

associated arrests is delay by the

courts, law enforcement, and correc-

tions agencies in reporting disposition

information to repositories (figure 8).

Another important reason, processing

delays by the repository, is described

more fully in a following section.

Court disposition information

required

3 weeks on average

On average in 2001, it took 21 days for

final court dispositions to reach the

State criminal history repository.

2

The

time required for repositories to receive

disposition information ranged from 1

day or less in six States to 80 days in

North Dakota. Repositories in most of

the reporting jurisdictions (21) received

final court disposition information within

15 days.

The average time required for final

court disposition information to reach

the repository steadily decreased from

36 days in 1997 and 33 days in 1999.

In 2001 final court dispositions reached

the repository 14 days faster on

average than they did in 1995; how-

ever, as six States have demonstrated,

the average time for submission could

be 1 day rather than 21 days.

Arrest information

required 11 days

on average

In 2001, as in 1999, arrest data and

fingerprints took 11 days on average to

be received by State repositories. The

time required to receive arrest informa-

tion ranged from 1 day or less in five

States and the District of Columbia to

169 days in Mississippi. In 22 States

and the District of Columbia, reposito-

ries received arrest information within 7

days.

In 1995 and 1997 transmission of

arrest information to the repository took

an average of 13 days and 14 days,

respectively.

3

Corrections information

required

9 days on average

In 2001 an average of 9 days elapsed

between a prison admission and the

receipt of that information by the State

repository. The time required for

repositories to receive prison admis-

sions ranged from 1 day or less in nine

States to 60 days in North Carolina.

Repositories in just over half of the

reporting jurisdictions (17) received

prison admission information in 7 days

or less.

In 2001 the average prison admission

reached the repository 5 times faster

than in 1995, when 45 days were

required. In 1997 and 1999 prison

admissions reached the repository

in 16 days on average.

4

Prosecutor declinations often did not

reach repositories

In 2001, 12 States were able to

estimate the number of prosecutor

declinations — decisions to drop or

modify charges — sent to the reposi-

tory in the prior year. Thirty-two States

indicated that State law or policy

required that prosecutorial declinations

be transmitted to criminal history

repositories.

Local prosecutors often fail to report

declinations to State record reposito-

ries. In 2001 five States indicated that

all prosecutorial declinations were

transmitted to the repository. In 1999

three States, and in 1997 six States,

reported that all prosecutors’ declina-

tions were transmitted to the

repository.

BJS, with the American Prosecutors

Research Institute, is scheduling a

survey to delineate more clearly the

processes by which disposition infor-

mation reaches or fails to reach a

repository. The study will examine the

following: whether statute, regulation,

office practice, or some other authority

10

Improving Access to and Integrity of Criminal History Records

Figure 8

0

0

00

0

0

0

0

0

00

0

1995 1997 1999 2001

0

10

20

30

40

50

Final court dispositions

Arrest information

Average number of days required for repositories

to receive criminal history information, 1995-2001

Number of days

Prison admissions

4

The average number of days for prison admis-

sion information to reach repositories was based

on 1995-2001 data from a cohort of 25 States.

3

The average number of days for arrest informa-

tion to reach repositories was based on 1995-

2001 data from a cohort of 40 States and the

District of Columbia.

2

The average number of days for final court

disposition information to reach the repository

was based on 1995-2001 data from a cohort of

28 States.

governs the transmission of declination

information by prosecutors; what

penalties (if any) exist for noncompli-

ance; the average time from declina-

tion to the notification of the repository;

and the impediments that exist in

reporting declinations promptly to the

repository.

Postal services used instead of

electronic communication

Trial courts provide most of the infor-

mation about final dispositions. Crimi-

nal history repositories in the 47 States

and the District of Columbia receive

final disposition information from trial

courts or the State court administra-

tor's office. Fifteen of those reposito-

ries receive all the information through

the Postal Service; 14 repositories

receive part of that information by mail.

Thirty-five States request final disposi-

tion information from prosecutors. In

16 States the repositories receive all

information from prosecutors by post;

in 12 States, part of that information.

Twenty-six States request law enforce-

ment agencies to report information on

final dispositions to the repository. In

13 States law enforcement agencies

rely entirely on the Postal Service; in

11 States, partially.

Repositories receive final disposition

information from appellate courts or

court administrators in 28 States. More

than half of these States (15) rely on

the Postal Service for delivery of all this

information; five rely on the Postal

Service for some of the information.

Manual systems used to research

missing dispositions

A 2001 BJS survey revealed that while

researching criminal records with

missing dispositions, agencies in 46

States rely on manual procedures.

Most of these States (34 of the 46) use

only manual systems to locate missing

final dispositions. Only Colorado,

Michigan, Pennsylvania, and South

Dakota fully utilize automated means

to obtain missing final dispositions.

Agencies unaware of their

reporting requirements

In certain States the criminal history

repository does not capture final dispo-

sition information because the

agencies responsible for providing this

information are not aware of all report-

ing requirements. Other States report

that courts and law enforcement

agencies are maintaining incomplete

or inaccurate statistics on final case

dispositions.

Arrest and corrections information

does not always reach repositories

The transmission of arrest and correc-

tions information to the repository is

not required by law or policy in all

States.

In 39 States and the District of Colum-

bia, there are policies to provide the

repository with data on the admission

or release of felons from State prison.

In 26 States and the District of Colum-

bia, there are policies to give the

repository information on the admis-

sion or release of a felon from a local

jail.

Thirty-one States and the District of

Columbia have policies to provide

probation information to the repository,

and 30 States and the District of

Columbia have policies to provide

parole information.

If an arrestee is not charged with a

crime after the fingerprints are submit-

ted to the repository, 19 States

indicated that State law does not

require that the repository be notified

of the failure to charge the arrestee.

Criminal history repositories face

challenges in processing records

Recent BJS surveys have suggested

that criminal history repositories are

encountering several problems includ-

ing significant backlogs, older records

that have no dispositions, and infre-

quent audits to ensure accuracy of

records.

The backlogs faced by criminal history

repositories can be measured in two

ways:

(1) by the length of time between the

repository’s receipt of information and

when that information is entered into a

record

(2) by the number of forms that await

entry into the record.

By both measures, State repositories

face significant challenges that must

be met to improve the NICS

background check process.

Improving Access to and Integrity of Criminal History Records

11

Overall average processing times by

repositories decreased

,

1995-2001

Separate from the issues whether the

repositories receive final court disposi-

tions, arrest information, or correctional

information, and whether the received

information is recent, is how well a

repository processes information it

does receive. Many State repositories

are unable to quickly process critical

information and include it in the record,

despite progress in recent years

(figure 9).

Final court dispositions

— Repositories

took an average of 25 days to process

final court disposition information and

post it to a criminal record in 2001.

The time required to post court disposi-

tion information ranged from 1 day or

less in 12 States to 330 days in

Washington. The majority of respond-

ing jurisdictions (23) entered these

data in 10 days or less.

Average processing time has

decreased since 1995 and 1997 when

repositories took 33 and 34 days,

respectively, to post final court disposi-

tions. In 1999 an average of 24 days

was required.

5

Prison admission information

— In

2001 an average of 22 days elapsed

between the repository’s receipt of

prison admission information and the

posting of that information to the

record. The time required to post

prison admission information ranged

from 1 day or less in nine States to 90

days in Illinois. The majority of

responding jurisdictions (21) enter

these data in 10 days or less.

The average number of days required

to post prison admission information

has declined significantly in recent

years. In 2001 repositories processed

and posted prison admission informa-

tion in nearly half the time required in

1999, when the process took an

average of 43 days. The average

processing time for prison admissions

in 2001 was considerably shorter than

in 1995 and 1997 when processing

took 49 days and 29 days,

respectively.

6

Arrest information

— Repositories took

an average of 13 days to post arrest

information to a criminal record in

2001. Eleven State repositories posted

arrest information in 1 day or less.

Oklahoma took 180 days — the

longest time period of any State. Most

States (27) posted arrest data in 7

days or less.

In 2001 repositories posted arrest

information to a criminal record in less

than half the time required in 1995,

when the process took an average of

32 days.

7

In 1997 and 1999 State

repositories took an average of 31

days and 28 days, respectively, to

process arrest information and post it

to a record.

12

Improving Access to and Integrity of Criminal History Records

Figure 9

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

1995 1997 1999 2001

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

Final court dispositions

Arrest information

Average number of days required for repositories

to post information to a record, 1995-2001

Number of days

Prison admissions

5

The average number of days required for

repositories to process and post final court

dispositions to a record was based on 1995-

2001 data from a cohort of 32 States and the

District of Columbia.

6

The average number of days required for

repositories to process and post prison admis-

sion information to a record was based on 1995-

2001 data from a cohort of 28 States.

7

The average number of days required for

repositories to process and post arrest infor-

mation to a record was based on 1995-2001

data from a cohort of 41 States and the District

of Columbia.

Repository backlogs exceed

2.5 million records

In 2001 most States reported that they

were encountering backlogs in entering

certain criminal history information into

State criminal databases. Twenty-six

States reported a backlog in entering

arrest and fingerprint information; 27

States had a backlog of court disposi-

tion forms; and 12 States had a

backlog of custody supervision reports.

Repositories in States that could

estimate the size of their backlogs in

2001 reported that 2.5 million records

of arrest, disposition, and custody

information were unprocessed or only

partially processed (figure 10). The

backlog comprised over 2 million court

disposition forms, 350,000 fingerprint

cards, and 130,000 custody supervi-

sion reports.

In 2001 State repository backlogs were

smaller in all three categories of infor-

mation than they were in 1995.

Compared to 1997, however, the total

backlog increased 50% in 2001. Most

of the increase after 1997 was

attributable to unprocessed court

disposition forms, increasing from

940,000 in 1997 to approximately 2

million in 2001. The number of unproc-

essed custody supervision reports

nearly tripled from 1997 to 2001 from

46,500 to 134,000. From 1997 to 2001,

the backlog of unprocessed fingerprint

cards was cut in half from 710,000 to

354,000.

The composition of State criminal

record backlogs remained unchanged

in recent years. Since 1995 court

disposition forms have comprised the

majority of State criminal record

backlogs, followed by arrest fingerprint

cards and custody supervision reports.

Because not all States can estimate

the size of their repository backlogs,

the true number of unprocessed or

partially processed criminal justice

records is likely to be higher than the

estimates reported here.

Older records on paper or microfilm

account for large portion of “open

arrests”

Many State criminal history records

contain arrests from several years ago

for which no final disposition was

reported. At the request of BJS, the

FBI drew a sample of NICS checks

that could not be completed instantly

due to the presence of “open arrests."

More than 75% of the arrests from this

sample were from 1984 or earlier.

Audits of criminal history records

remain infrequent

In 2001, 23 State criminal history

repository directors reported that their

databases had not been audited for

completeness in the prior 5 years. An

audit would have told them how

accurate and complete were the crimi-

nal histories in their holdings. Over half

of those States (13) reported that they

had not planned or scheduled a data

quality audit to occur within the next 3

years. Overall, 24 States did not plan

to perform a data quality audit within 3

years of the survey.

Of the 27 States with completed audits

after 1995, changes were made to

improve data quality as a result of 22

of these audits.

Improving Access to and Integrity of Criminal History Records

13

Figure 10

State repository backlog, by type of record, 1995-2001

1995 1997 1999 2001

0

500,000

1,000,000

1,500,000

2,000,000

2,500,000

Number of records

Custody supervision reports

Fingerprint cards

Court disposition forms

National standards can help assure

complete criminal history records

The problem of missing dispositions

in State criminal history records is

perpetuated in part because there is no

national consensus on how a missing

disposition is defined, measured, or

researched by State agencies.

Improvements in criminal history

records have fallen short of earlier BJS

efforts to establish voluntary reporting

standards.

8

The presence of a national

standard on the time required for final

court disposition information to reach

the repository would encourage better

performance by States that currently

process this information more slowly.

National standards are lacking on the

following five issues concerning crimi-

nal history record completeness.

States define "missing dispositions"

differently

States' definitions of an “open” arrest

or “missing disposition” vary. It is diffi-

cult to accurately identify missing

dispositions and obtain a national

estimate of the extent of the problem

because the term has different

meanings in different States.

Most States (34) and the District of

Columbia consider any arrest event or

charge without a disposition to be a

“missing disposition,” while 16 States

require a certain amount of time to

pass before an arrest event or charge

is officially considered a missing dispo-

sition.

Ten States reported that they define a

missing disposition as an arrest that is

not being actively prosecuted. These

10 States rely on a variety of methods

to determine that an arrest is not being

actively prosecuted, including notifica-

tion by the prosecutor or court, search-

ing court records, and regular audits of

records.

States are divided as to whether they

measure a missing final disposition by

using an arrest event or an arrest

charge. An event has one or more

charges. Twenty-one States measure

a final disposition by an arrest event;

17 States identify it by an arrest

charge; and 10 States and the District

of Columbia measure a missing final

disposition by both an arrest event and

an arrest charge.

There are also two exceptions to the

basic information used to determine

whether a disposition is missing.

Vermont uses arraignments rather

than arrests, and Pennsylvania does

not specify any particular event to

measure a missing disposition.

States require long delays before

designating a disposition as “missing

”

Sixteen State repositories require that

time elapse before a disposition is

officially considered to be missing.

If the subject of a background check

has been convicted of a disqualifying

offense and the conviction is not

included in the record, in certain States

months will pass before the record is

designated as having a missing dispo-

sition. During those months the subject

will not be prohibited from purchasing a

firearm because the NICS check will

not reveal the disqualifying conviction.

Of the 16 States that require a certain

amount of time to pass before an

arrest event or charge will be officially

considered to have a missing disposi-

tion. Two States require that more than

1 year must pass before a record

without a disposition is officially

declared to have a missing disposition

(Connecticut and Washington). In

seven States an entire year must

elapse before a disposition is consid-

ered missing (Alaska, Indiana, Kansas,

Michigan, Missouri, South Carolina,

and Virginia). In three States a disposi-

tion is not counted as missing until

more than 6 months have passed

(Arizona, Maine, and New York). The

remaining four States use another

time interval.

State procedures for handling missing

dispositions differ

When State repositories receive new

disposition information that cannot be

linked to an arrest charge or event,

States follow varying policies.

From July 1, 2000, to July 1, 2001,

45 States and the District of Columbia

reported receiving final court disposi-

tions that could not be linked to arrest

information in the criminal history

record. When final court dispositions

could not be linked to an arrest, 27

States did not enter the unlinked infor-

mation. Eight States created a

“dummy” arrest segment with the infor-

mation from the court disposition

record, and three States entered the

court information without any linkage to

a prior arrest segment. The remaining

12 States and the District of Columbia

followed other procedures.

In that same 1-year period, 34 State

repositories received information from

corrections agencies that could not be

linked to arrest information in the crimi-

nal history record. When States

received correctional information for

which there was no underlying court

information, 25 States imputed a

conviction for the record. Nineteen

States and the District of Columbia

reported that they did not enter a

conviction on the record based on

information from corrections agencies.

When information from corrections

agencies cannot be linked to an arrest,

the information is not entered into the

14

Improving Access to and Integrity of Criminal History Records

8

Recommended Voluntary Standards for Improv-

ing the Quality of Criminal History Record Infor-

mation (56 FR 5849).

system in 14 States and the District of

Columbia. Six States create a

"dummy" arrest segment with the

correctional information, and 15 States

enter the correctional information

without any linkage to a prior arrest

segment.

From July 1, 2000, to July 1, 2001, 32

State repositories received information

from final prosecutor dispositions that

could not be linked to arrest informa-

tion in the criminal history record.

When prosecutor information could not

be linked to an arrest, 24 States and

the District of Columbia did not enter

the unlinked information. Six States

created a "dummy" arrest segment

with the unlinked prosecutor informa-

tion, and two States entered the prose-

cutor information without any linkage to

a prior arrest segment.

Common identifiers absent in criminal

history records

The States use a wide variety of identi-

fiers to link disposition information with

the arrest or charging information, and

no single identifier is used by all 50

States.

Forty States and the District of Colum-

bia link dispositions by using a unique

arrest event identifier; 28 States and

the District of Columbia use a unique

tracking number for an individual

suspect; 22 States and the District of

Columbia link dispositions by using the

arrestee’s name; and 16 States and

the District of Columbia link disposi-

tions by using a name and a reporting

agency case number. Certain States

use other identifiers, such as arrest

date, date of birth, or Social Security

number of the arrestee, court docket

number, or charge number.

None of the States require positive

identification that would occur with a

biometric identifier like fingerprints.

Many States unable to link final dispo-

sitions to specific charges

Disposition information in a criminal

record is often not linked to specific

charges or counts. In 33 States and

the District of Columbia, the method

used by the repository to link disposit-

ion information to the arrest/charge

information allows the link to be made

to specific charges or counts, an arrest

cycle. State criminal history record

systems can be compared only with

difficulty if some systems are apprecia-

bly more sophisticated and complete

than others. Dispositions should be

linked to specific charges in all States.

Accurate linkage of dispositions to

criminal records results from proper

use by courts of relevant arrest trans-

action numbers and the courts’ direct

submission of a livescan with the

associated disposition of the arrest.

Courts have indicated a growing inter-

est in utilizing NCHIP funds to

purchase livescan equipment.

BJS sponsors National Evaluation

of NCHIP

In response to the Attorney General’s

June 2001 directive, BJS commis-

sioned a 3-year evaluation of the

National Criminal History Improvement

Program (NCHIP). The two purposes

of the evaluation were —

(1) to measure the performance of

State criminal history records systems

(2) to identify improvement activities

that would be most effective in improv-

ing record completeness.

The evaluation ensured that the

NCHIP grant program more efficiently

addressed strengths and weaknesses

of State criminal history record

systems. Future NCHIP grants will be

targeted to the specific record system

deficiencies identified for each State.

Improving Access to and Integrity of Criminal History Records

15

The Records Quality Index (RQI) to

measure NCHIP performance

In 2001 BJS began development of a

new criminal records performance

measurement system. The system will

better guide NCHIP provision of funds

and technical assistance to the States.

The records quality index (RQI)

collects and summarizes performance

measures that objectively assess the

relative capabilities of each State's

criminal history record system. The

RQI assigns a system an overall rating

based on a wide variety of perform-

ance measures directly related to

NCHIP objectives.

A State’s RQI can be compared to the

RQI of other States to determine the

relative strength of the State's criminal

history record system. The RQI will

also allow for more specific analysis,

permitting BJS to track the progress of

a State by the score received on each

of its performance measures.

The overall RQI a State receives can

be compared to a national average to

express whether the overall efficiency

of the State's criminal history record

system meets, exceeds, or is below

the impartial summary of all States.

After complete data are received, the

RQI will become an invaluable tool for

identifying the strengths and

weaknesses of each State's criminal

history record system. Using RQI infor-

mation, NCHIP will target funds to

activities that will most significantly

improve a State's RQI, thereby improv-

ing national background check

systems more directly and quickly.

As of March 2004, 34 States have

completed all RQI data submissions.

Another 10 States have made partial

submissions and have demonstrated

substantial progress toward supplying

all RQI data.

Elements of the RQI offer distinct

vantage points

The evaluation for the RQI will break

down a State's criminal history record

system into a wide variety of perform-

ance measures that describe the

system's components, overall

structure, and efficiency.

One measure of the efficiency of a

State criminal history record system is

the average time that elapses before

an arrest report is posted to the crimi-

nal history repository. Other ways a

system's utility can also be assessed

are by the percentage of arrest records

that are linked to dispositions and by

whether State's criminal justice

agencies and the State's judicial

system use common identifiers.

A State will receive a high score on

one component of the RQI if all of its

criminal history records are automated

and will receive a high score on

another component if law enforcement

agencies are connected to the courts

electronically.

The RQI consists of three sets of

performance measures:

input

measures, process measures,

and

outcome measures.

Input measures

describe the compo-

nents of a record system, including the

following: State laws requiring the

fingerprinting of prisoners and trans-

mission of the fingerprints to the State

repository; use of unique tracking

numbers in the records for individual

subjects; and requirements that prose-

cutors submit declinations to the

repository.

Process measures

reflect system

performance, including the following:

procedures followed by the repository

when a link can not be made between

a disposition and an arrest; strategies

employed to ensure accuracy of arrest

data, fingerprints, and final court dispo-

sitions received at the repository; the

average time between the occurrence

of a final felony court disposition and

the entry of data into the criminal

history database; and the automation

and auditing of certain procedures.

Outcome measures

reflect the impact

of the State's system and whether the

records are accessible and complete.

Outcome measures include the follow-

ing: the percentage of dispositions that

cannot be linked to an arrest; the

number of III records available;

backlogs in entering information into

the database; and repository notifica-

tion of prosecutor declinations.

16

Improving Access to and Integrity of Criminal History Records

Criminal histories integrated with

NIBRS reveal key crime factors

The National Incident-Based Reporting

System (NIBRS) appreciably advances

efforts to learn important details about

crimes in the United States. Beyond

the summary counts of eight offenses

presently collected for the FBI Uniform

Crime Reports (UCR), NIBRS repre-

sents a more sophisticated data collec-

tion system. NIBRS enables State and

local jurisdictions to capture detailed

offense, offender, victim, property, and

arrest information concerning each

crime incident. NIBRS goals are —

• to enhance the quantity, quality, and

timeliness of crime data collected by

law enforcement

• to improve the methodology used in

compiling, analyzing, auditing, and

publishing collected crime statistics.

The broader scope of offense and

offender characteristics also permits

the development of policy-relevant

findings. These findings can describe

the nature and characteristics of

crimes such as gun assaults, domestic

violence, hate crimes, and crimes

against children. Through NIBRS, law

enforcement officials, analysts, and the

public can better understand trends in

more types of crime and in the amount

of harm to victims.

Jurisdictions that have incident-level

reporting systems are more capable of

using crime data for strategic planning,

tactical crime analysis, and manpower

deployment. This ability should result in

more effective use of limited resources

and better crime control strategies.

Incident-level data, such as NIBRS,

provide detailed information on the

contingencies of a crime, including

victim characteristics and conse-

quences for victims. Such data, when

linked to criminal records, would

permit a background check to deter-

mine whether elements of the offense

meet specific prohibitions for firearm

transfer or other factors of concern.

Incident reports would contain the

victim’s characteristics, the victim/

offender relationship, and the

offender’s use of a firearm — estab-

lishing whether the victim was a child

or whether the offense involved

domestic violence.

The FBI and BJS have been active in

assisting the States in meeting the

NIBRS standards and becoming certi-

fied for NIBRS data submission. In

2001 BJS distributed $13 million to 26

States through the NIBRS Implementa-

tion Program to develop and operate

NIBRS-compatible systems.

As of August 2003, 24 States had their

State UCR programs approved by the

NIBRS Certification Board, according

to the FBI's NIBRS Implementation

Coordinator (map). Twelve States were

testing their systems to determine if

they will soon meet certification

standards. Nine States were develop-

ing a NIBRS system, and six (Alaska,

Georgia, Florida, Mississippi, Nevada,

and Wyoming) had no formal plans to

provide NIBRS data to the FBI.

Improving Access to and Integrity of Criminal History Records

17

Source: FBI, Criminal Justice Information Services Division, Program Support Section,

Greg Swanson, NIBRS Implementation Coordinator.

NIBRS certified

Testing NIBRS

Developing NIBRS

No formal plans regarding NIBRS

NIBRS Status of the States, August 2003

Since 1995 NCHIP has operated under

a broad mandate to improve public

safety by enhancing the quality,

completeness, and accessibility of the

Nation's criminal history record infor-

mation systems. NCHIP has funded

State and local initiatives designed to

improve criminal records and to allow

these records to be used for criminal

justice and authorized noncriminal

justice purposes. Achievements of

NCHIP were highlighted on pages 1 to

6.

A BJS review of the NCHIP program

has concluded that the program’s

resources must be more aggressively

targeted toward bringing the States into

compliance with the Brady Act's provi-

sions. NCHIP must also become fully

responsive to evolving needs for more

extensive and thorough background

checks to protect homeland security.

To reflect these NCHIP management

objectives, five recommended action

items are to be incorporated into

NCHIP:

• obtaining the full participation of the

States in the FBI's Interstate Identifica-

tion Index (III)

• improving State contributions to the

FBI's national databases of prohibited

purchasers

• formally establishing a National

Technical Assistance Center supported

by BJS

• promoting the adoption of a uniform

RAP sheet to standardize records

among the States

• periodic BJS surveys of State criminal

record holdings.

Action item 1: Obtain full State

participation in the FBI's Interstate

Identification Index (III)

Serving as the backbone of the NICS

system, the Interstate Identification

Index (III) is a decentralized index-

pointer system maintained by the FBI

for exchanging criminal history records.

The III connects the FBI’s computer-

ized files with State-level computerized

files. The III contains personal identifi-

ers for more than 48 million offenders.

Federal, State, and local criminal

justice agencies may access it to deter-

mine whether an individual has a crimi-

nal record anywhere in the country.

The III's "pointer" specifies the Federal

or State source that maintains any

relevant record(s). Once a hit is made

against the Index, the subject's data

are automatically retrieved from each

repository and forwarded to the

requesting agency. The FBI estimates

that the III database contains 94% of

the records checked by the NICS;

therefore, it is critical that all States

enter full partnership and contribute

their identifiers for inclusion in III.

States generally enter participation in

the III system in two phases, defined by

the nature of the records that they

agree to provide. For the second

phase, that of full participation, a State

agrees to make its III-indexed records

available to Federal and State agencies

for both criminal justice and noncrimi-

nal justice purposes.

In the second phase the FBI ceases to

maintain duplicate criminal records for

persons arrested and prosecuted in

fully participating States. All users of

criminal history records — for criminal

justice purposes as well as authorized

noncriminal justice purposes — will

obtain records directly from States'

central computerized files or from the

FBI for Federal records.

Fully participating States must meet

minimum standards that relate to

several factors, including the complete-

ness and maintenance of the records,

the presence of fingerprints for each

record, and procedures to respond to

record requests. At yearend 2001 a

quarter or more of the criminal history

records in a majority of States could

not meet those standards.

Opportunities for improving background checks

Improving Access to and Integrity of Criminal History Records

19

States with low, medium, and high levels of III-accessible records, yearend 2002

Fewer than 50% of criminal history records are accessible through III

50% to 74% of criminal history records are accessible through III

75% or more of criminal history records are accessible through III

Fewer than 50% of criminal history records are accessible through III

50% to 74% of criminal history records are accessible through III

75% or more of criminal history records are accessible through III

Figure 12

At the end of 2002, 22 States had at

least 75% of their records accessible

through III (map). Thirteen States and

the District of Columbia had less than

half of their records accessible through

III. The States and the Federal Govern-

ment will benefit in several ways when

all States become full III participants.

First, the duplicate maintenance of

criminal history records by the States

and the FBI will be eliminated, resulting

in significant cost savings. No longer

will States have to submit to the FBI

fingerprints and charge/disposition data

for all felony and serious misdemeanor

arrests. Instead, States will submit only

fingerprints and textual identification

data for each person's first arrest to

update the III and the National Finger-

print File (NFF). No longer will the FBI

keep records on State offenders and

process fingerprint cards for all State

arrests. Instead, the FBI will maintain

the III, the NFF, and full criminal

records of Federal offenders.

Second, records made available on an

interstate basis will be more complete

for both criminal justice and noncrimi-

nal justice purposes, including the

screening of applicants for certain

sensitive positions. State repository

records are more current than FBI files.

In addition, many States maintain

misdemeanor records that have not

been submitted to the FBI. These

records will become available through

the III system for NICS and other

authorized uses.

Third, certain noncriminal justice users

will enjoy faster response times

because they will be receiving

electronic responses rather than

mailed record responses from the FBI.

These noncriminal justice users may

also benefit from increased efficiency

at the State level resulting from

increased automation and system

improvements preceding III

participation.

Action item 2: Encourage States to

contribute records to the national

databases of persons prohibited

from purchasing firearms: the NICS

Index and National Crime Informa-

tion Center files

A background check for a firearm

transfer involves the use of records

available through the III and two other

databases maintained by the FBI:

(1) the NICS Prohibited Persons Index

(NICS Index), containing records of

persons prohibited by the Gun Control

Act to purchase a firearm — those

dishonorably discharged from the

armed services, persons who have

renounced U.S. citizenship, mental

defectives, controlled substance

abusers, and illegal/unlawful aliens

(2) the National Crime Information

Center (NCIC) Files, containing records

on sex offenders, wanted persons,

convicted persons on supervised

release, and subjects of protective/

restraining orders.

FBI statistics show that States have

contributed infrequently to the NICS

Index and NCIC databases. Protection

of U.S. residents depends on these

databases of prohibited purchasers

being complete and current.

The NICS Index

The NICS Index is divided into six

databases of persons disqualified

under Federal law from receiving

firearms:

(1) the Denied Persons File

(2) the Mental Defectives/Commit-

ments File

(3) the Controlled Substance Abusers

File

(4) the Illegal/Unlawful Aliens File

(5) the Citizenship Renunciates File

(6) the Dishonorable Discharges File.

State law enforcement officials contrib-

ute to only the first four of the six

databases. In the following summary a

State is listed as having contributed to

a database as of February 1, 2003,