CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU | MARCH 2022

Credit card late fees

1 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

Table of contents

Table of contents

*

.............................................................................................................1

Executive Summary .........................................................................................................2

1. Introduction ................................................................................................................3

2. Consumer impact ......................................................................................................6

3. Market reliance .........................................................................................................13

4. Conclusion................................................................................................................16

*

Report prepared by Joanna Cohen, Lucas Nathe, László Sándor, Margaret Seikel, and Wei Zhang.

2 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

Executive Summary

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, consumers had steadily been paying more in credit card late

fees each year—peaking at over $14 billion in 2019. Late fees assessed by issuers declined to

about $12 billion in 2020 given record-high payment rates and public and private relief efforts.

Even during the pandemic, late fees accounted for over one-tenth of the $120 billion consumers

pay in credit card interest and fees annually. In 2021, total late fee volume was on the rise again.

CONSUMER IMPACT OF CREDIT CARD LATE FEES

In 2019, a consumer with a major issuer’s credit card was charged a $26 late fee on average for

each late payment—except for each subsequent late fee within six billing cycles of an earlier late

payment. For those, the average fee rose to over $34. Cardholders with subprime and deep

subprime scores are far more likely to incur repeat late fees in a given year than those in higher

credit score tiers. Increased incidence coupled with a more expensive fee for repeat late payment

resulted in the average deep subprime account being charged $138 in late fees in 2019,

compared with $11 for the average superprime account.

Credit card late fees disproportionately burden consumers in low-income and majority-Black

neighborhoods. Late fees are negatively correlated with indicators of upward economic mobility.

Furthermore, these penalty fees can represent a surcharge of 24 percent annualized on top of

assessed interest on unpaid balances—one of multiple financial consequences of a missed

payment.

MARKET RELIANCE ON CREDIT CARD LATE FEES

Late fees account for 99 percent of penalty fees and over half of the credit card market’s total

consumer fees. While the degree to which companies rely on late payment for revenue varies,

late fees represent a larger share of charges for issuers primarily serving consumers with lower

credit scores than for issuers that extend little to no credit to such consumers.

Most smaller banks and credit unions charge a maximum late fee of $25 or less, but almost all of

the largest credit card issuers contract at or near the higher fee amounts that are specified by

regulation. A small but increasing percentage of companies charge no late fees or offer products

with increased flexibility for late payments. Yet, the overall credit card market continues to rely

on late fees disproportionately paid by economically vulnerable consumers.

3 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

1. Introduction

When a consumer does not make at least their minimum payment by a statement due date, a

credit card issuer typically assesses a late fee.

1

These penalties represent both a substantial

financial burden for consumers and a major source of revenue for companies.

ME THODOLOGY

This report leverages three major data sources to explore both the consumer impact of and

industry reliance on credit card late fees:

1. De-identified information that the Federal Reserve Board (Board) collects as part of its

“Y-14M” (Y-14) data collection: the Board collects these account-level data monthly from

bank holding companies that have total consolidated assets exceeding $50 billion.

2

This

sample accounted for just under 70 percent of outstanding balances on consumer credit

cards as of year-end 2020.

3

2. Data provided in response to a series of data filing orders from a diverse group of

specialized issuers: these summary data allow for a broader or more detailed perspective

into certain facets of the market and, where these data supplement Y-14 data, are

collectively called “Y-14+.”

3. The CFPB’s Credit Card Agreement Database: this is an online database available to the

public that contains most credit card agreements available to consumers.

4

1

A minimum payment is the minimum dollar amount that must be paid each month on a credit card. CFPB

previously found that minimum payment formulae varied widely across issuers, both in terms of the amount of the

payment itself as well as the complexity in its calculation and description. See CFPB, The Consumer Credit Card

Market, at 130 to 132 (Dec. 2015) (2015 Report),

http://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201512_cfpb_report-the-

consumer-credit-card-market.pdf. A credit card late fee cannot exceed the value of the minimum payment. 12 C.F.R.

§ 1026.52(b)(2)(i)(A); Comment 52(b)(2)(i)-1.

2

See Bd. of Governors. of the Fed. Rsrv. Sys., Report Forms FR Y-14M,

https://www.federalreserve.gov/apps/reportforms/reportdetail.aspx?sOoYJ+5BzDYnbIw+U9pka3sMtCMopzoV

(last visited Jan. 11, 2022) (for more information on the Y-14M collection).

3

This study reports only aggregate measures and reveals no information about any specific issuer. These issuers

represent a large portion of the market but are not necessarily representative of the portion of the market not

covered by the data the Bureau receives. Results reported from Y-14 data throughout this report should be

interpreted accordingly. See CFPB, The Consumer Credit Card Market, 16 (Sep. 2021) (2021 Report),

https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/cfpb_consumer-credit-card-market-report_2021.pdf

.

4

CFPB, Credit Card Agreement Database (Database), http://www.consumerfinance.gov/credit-cards/agreements.

Agreements in 2020 and 2021 may include omissions due to the Bureau’s previous COVID-19 regulatory fl exibility

statement; see CFPB, Statement on Supervisory and Enforcement Practices Regarding Bureau Information

Collections for Credit Card and Prepaid Account Issuers (Mar. 26, 2020),

https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/cfpb_data-collection-statement_covid-19_2020-03.pdf.

4 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

DEFINITIONS

The Credit Card Accountability, Responsibility, and Disclosure Act of 2009 (“CARD Act”)

required late fees be “reasonable and proportional” and the implementing regulation

(Regulation Z) sets a “safe harbor” for specific fee amounts, which the CFPB adjusts for inflation

annually.

5

The implementing regulation initially established a safe harbor of $25 for a first late

payment and $35 for each subsequent violation within the next six billing cycles. Repeat late

fees are defined as any late fee within six billing cycles of an earlier late fee; first-time late fees

are instances that are not repeat fees.

Y-14 and Y-14+ data include commercially-available credit scores which are then grouped into

five tiers: superprime (720 or greater), prime (660 to 719), near-prime (620 to 659), subprime

(580 to 619), and deep subprime (579 or less).

6

References to “COVID-19” or “pandemic” are used as shorthand for the period of economic crisis

and broad social disruption beginning in 2020. As of this report writing, it remains too soon to

determine the effects of the pandemic on consumer behavior. As such, after discussing unusual

trends in the overall late fee landscape in this section, this report primarily focuses on 2019 data.

LATE FEE LANDSCAPE

Late fees represent over one-tenth of the consumer cost of credit paid to issuers in interest and

fees. This has been true since at least 2015 and remained true in 2020 despite a year-over-year

decline in the total volume of late fees.

7

TABLE 1: TOTAL COST OF CREDIT CARDS TO CONSUMERS (Y-14+)

YEAR LATE FEES TOTAL INTEREST AND FEES LATE FEES SHARE

2018 $13 B $119 B 11%

2019 $14 B $128 B 11%

2020 $12 B $117 B 10%

5

15 U.S.C. § 1665d(a) (2012); 12 C.F.R. § 1026.52(b). Regulation Z requires the Bureau to annually adjust the safe

harbors to reflect changes in the Consumer Price Index. 12 C.F.R. § 1026.52(b)(1)(ii)(D).

6

A little more than half of (credit visible) Americans were in the superprime segment by the end of 2019. A sixth were

deep subprime or prime each, and around 7% were in both the subprime and the near subprime categories.

7

Y-14+

5 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

Monthly late fee volume in May 2020 plummeted over 33 percent from its January high, in

parallel with the unprecedented decline in credit card debt from Q4 2019 to Q2 2020.

8

Economic Impact Payments (EIPs) coincided with the initial decline in late fees across all credit

score tiers, as did the initial issuance of industry fee waivers.

9

However, late fee volume did not

hit its lowest point in recent years until April 2021, in conjunction with the distribution of the

third EIP, after most issuers’ COVID-19 relief programs ended.

10

FIGURE 1: INDEXED MONTHLY LATE FEE VOLUME BY CREDIT SCORE TIER (Y-14)

11

The decline in overall late fee volume in early 2021 was largely driven by a steep decline among

accounts with below-prime scores. Between February 2020 and April 2021 late fee volume for

accounts associated with deep subprime and subprime scores fell 59 percent and 49 percent

respectively, whereas late fee volume for prime and superprime accounts fell by 30 percent and

23 percent. This pattern suggests that changes in payment behavior for consumers with lower

credit scores explain much of the significant reduction in late fee volume.

12

However, from this

trough in April to the most recent data from October 2021, late fee volume rose for all credit

score tiers.

13

8

See 2021 Report at 27, supra note 3.

9

See 2021 Report, supra note 3.

10

IRS, Third Economic Impact Payment, https://www.irs.gov/coronavirus/third-economic-impact-payment (last

accessed Feb. 14, 2022). See also 2021 Report, Section 5.5, supra note 3.

11

Indexed to late fee vol

12

See 2021 Report, supra note 3, at Sections 2 and 3 for more information on payment rates during 2020.

13

See 2021 Report at 19, supra note 3.

Mar 2017 Mar 2018 Mar 2019 Mar 2020 Mar 2021

40

60

80

100

120

140

Superprime Prime

Near-prime

Subprime Deep subprime

Overall

6 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

2. Consumer impact

The burden of late fees varies across the United States. In 2019, the average late fee in the credit

card market was $31, but this value differs by card type, credit score, location, and income.

14

Notably, the cost of late fees to impacted consumers is higher than the estimations below, as this

section analyzes late fees per account, not per person.

15

LATE FEES BY CARD TYPE AND CREDIT SCORE

For both general purpose and private label credit card accounts issued by major banks, repeat

late fees are higher than first-time late fees.

16

In 2019, first-time late fees for general purpose

cards averaged $26, while repeat fees were 36 percent higher at $35 on average. Private label

cards had a slightly higher average first-time late fee of $27 while repeat fees were 28 percent

higher, averaging $34. As of 2019, the safe harbor values were $28 and $39, respectively.

17

FIGURE 2: AVERAGE FIRST-TIME AND REPEAT LATE FEE BY CARD TYPE IN 2019 (Y-14)

A small share of accounts in low credit score tiers incur a high proportion of late fees. Subprime

and deep subprime accounts incurred 42 percent of all late fees in 2019 even though only 12

14

See 2021 Report, supra note 3, at 55.

15

For the share of consumers with at least one credit card, the average number of accounts held is between 2 and 5,

depending on credit score tier. See CFPB, The Consumer Credit Card Market, at 35 (Aug. 2019) (2019 Report),

https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/cfpb_consumer-credit-card-market-report_2019.pdf

.

Additionally, some analyses in this section likely underestimate the burden of late fees for accounts with below-

prime scores, as Y-14 data do not include tradelines from subprime specialist issuers with a higher average late fee

of $32 in Y-14+.

16

This report generally refers to “general purpose credit cards” that can transact over a network accepted by a wide

variety of merchants and “private label credit cards” that can only be used at one or few specific merchants.

17

12 C.F.R. § 1026.52(b)(1)(ii); Comment 52(b)(1)(ii)-2.i.H; 83 FR 43503 (Aug. 27, 2018).

$26

$27

$35

$34

General purpose Private label

$0

$5

$10

$15

$20

$25

$30

$35

First time Repeat

7 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

percent of accounts fell into those categories. Meanwhile, the 59 percent of accounts that are

considered superprime incurred only 20 percent of the total late fee volume.

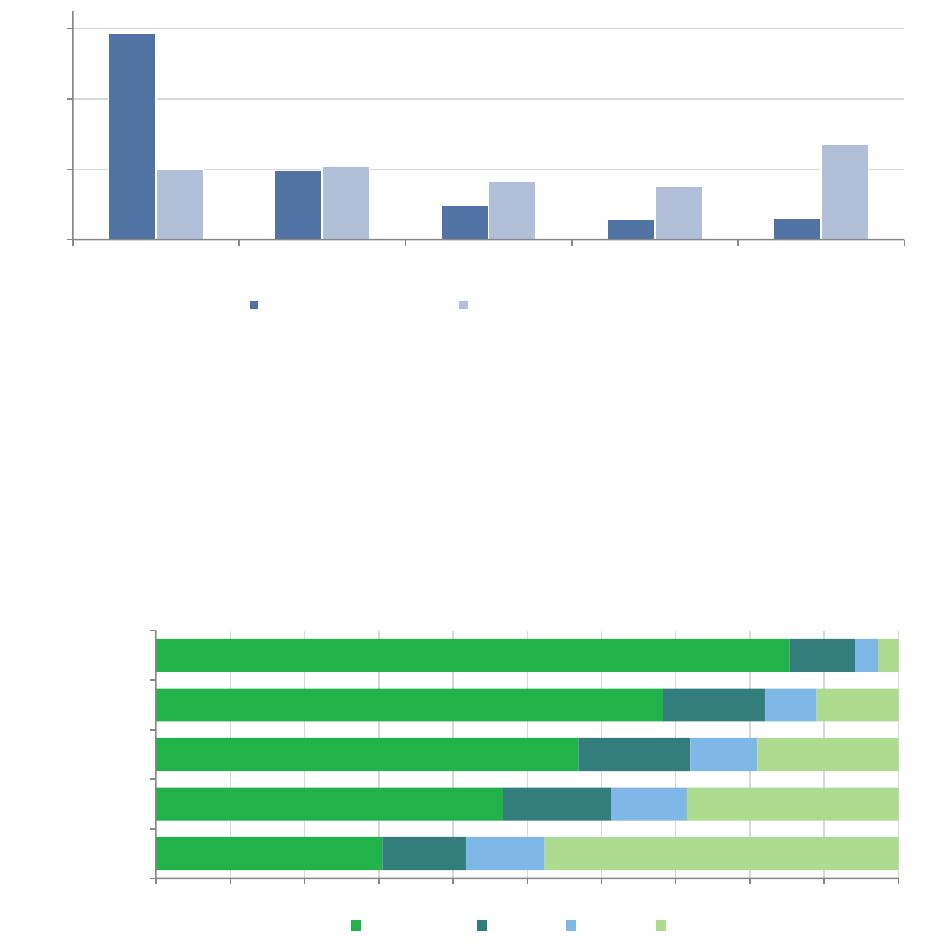

FIGURE 3: SHARE OF ACCOUNTS AND SHARE OF LATE FEE VOLUME IN 2019 (Y-14+)

Accounts in lower credit tiers are significantly more likely to be charged multiple late fees in a

year than accounts in higher tiers. In 2019, 48 percent of deep subprime and 28 percent of

subprime accounts were charged three or more late fees, compared with only 3 percent of

superprime accounts. Conversely, superprime accounts were far more likely to incur no late

fees: 85 percent of superprime accounts were charged no late fees in 2019, compared with only

30 percent of deep subprime accounts.

FIGURE 4: SHARE OF LATE FEE INCIDENCE BY CREDIT SCORE TIER IN 2019 (Y-14)

Both late fees and interest incurred in 2019 as a share of cycle ending balances increase as credit

scores decrease. However, the rise of total annual late fees as a share of balances from above-

prime to below-prime credit score tiers was much higher than that of interest. The average deep

subprime account incurred late fees averaging 11 percent of balances on top of annual interest

59%

20%

10%

6%

6%

20%

21%

17%

15%

27%

Superprime Prime Near-prime Subprime Deep subprime

0%

20%

40%

60%

Share of accounts Share of late fee volume

30

47

57

68

85

11

15

15

14

9

11

10

9

7

3

48

28

19

11

3

Deep subprime

Subprime

Near-prime

Prime

Superprime

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100%

None 1 2 3+

8 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

equaling 21 percent of balances. By contrast, late fees for superprime and prime accounts each

averaged 0.8 percent and 1.3 percent of balances, while the incurred interest in 2019 averaged

10 percent and 17 percent of balances accordingly.

FIGURE 5: AVERAGE ANNUAL LATE FEE VOLUME AND INTEREST AS A SHARE OF AVERAGE CYCLE

ENDING BALANCES BY CREDIT SCORE TIER IN 2019 (Y-14+)

Late fees are in addition to the finance charges incurred for carrying a balance. Around half of

late fees in the superprime segment in 2019 were assessed to customers who were not rolling

over their balances in the month before or after.

18

Inasmuch as their late fee was unexpected or a

costly mistake to pay for using the cards, the coinciding finance charge is a similar burden. In

the subprime or deep subprime segments, almost all late fees are incurred by regularly revolving

customers who missed a payment.

19

For them, a finance charge will be owed in any case and the

main financial consequence of a missed payment is the late fee.

Overall, the average deep subprime account was charged $138 in late fees in 2019, compared

with $11 for the average superprime account.

20

The higher incidence of late fees for accounts in

lower tiers, combined with higher average charges for repeat fees, drives this disparity. Notably,

these figures alone underplay the significant burden of late fees for consumers, as this section

examines average late fees per account, not per person. Cardholders in the deep subprime score

tier hold, on average, at least two credit cards.

21

If a typical consumer with a deep subprime

18

Y-14.

19

Y-14.

20

Y-14+.

21

See 2019 Report, supra note 15, at 35.

1%

1%

3%

6%

11%

10%

17%

19%

21%

21%

Superprime Prime Near-prime Subprime Deep subprime

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

Late fees Interest

9 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

score incurred the average late fee charges on each card, they would have incurred about $300

in late fees by the end of the year.

LATE FEES BY GEOGRAPHY

In some states, the average credit card accumulated almost $30 in total late fees in 2019, while

in others the average was below $20. Consumers in southern states pay more in average late fees

per account. This can stem from a higher share of accounts paying any late fees in a given month

or a greater number of accounts incurring higher repeat late fees.

22

FIGURE 6: AVERAGE LATE FEES PER ACCOUNT IN 2019 (Y-14)

In 2019 credit card accounts held by consumers living in the United States’ poorest

neighborhoods paid twice as much on average in total late fees than those in the richest areas.

Yet, cardholders in ZIP codes with the highest income per adult still paid $14 on average in total

late fees in 2019 on each credit card they had open.

23

22

Correlations presented in this section may be affected by underlying credit score variation by geography.

23

ZIP-level aggregates on total incomes and number of individuals come from the Statistics of Income of the Internal

Revenue Service. Our chart groups ZIP codes into 35 equal-sized bins (having the same number of accounts in the

Y-14) and plots each bin’s average total amount of late fees per account against the bin’s average income. The line

simply connects these 35 dots, helping with interpolation.

10 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

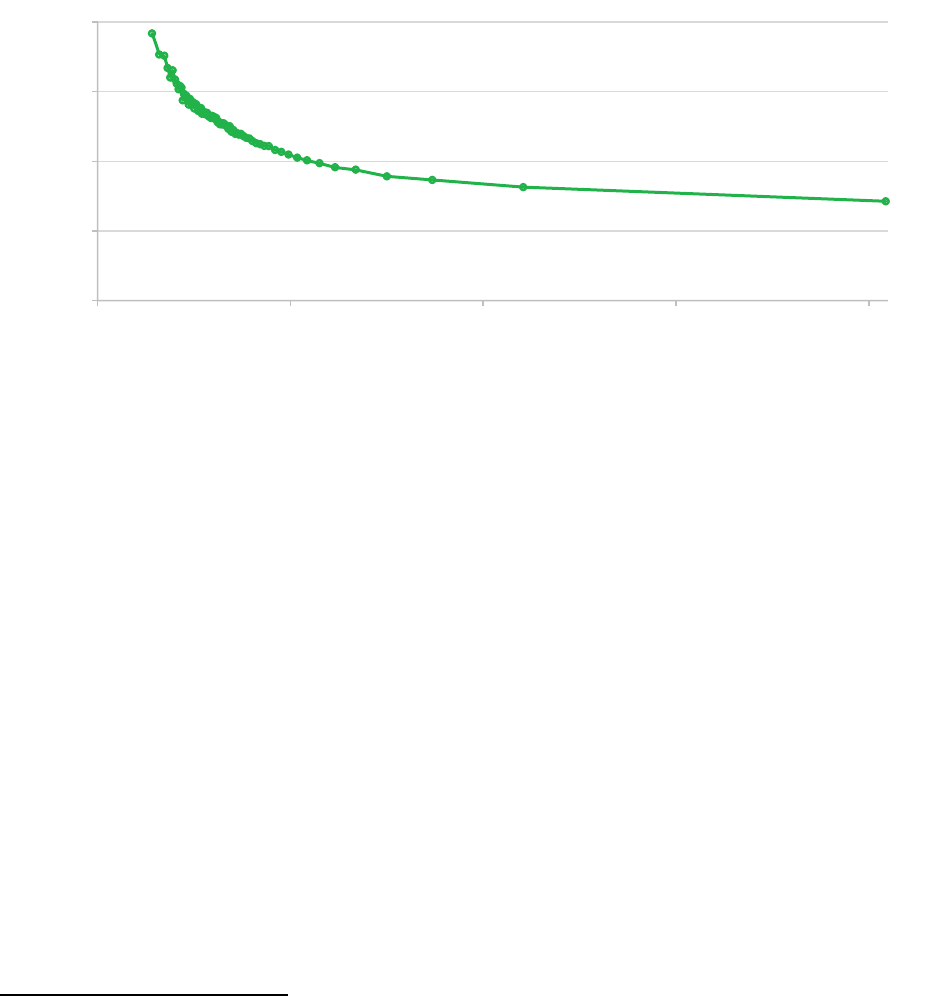

FIGURE 7: AVERAGE LATE FEE AND PER CAPITA INCOME IN 2019 (Y-14, IRS)

When we link the ZIP code of a cardholder’s residence to census tracts, we find other signs of the

unequal burden of late fees. Cardholders in tracts where a majority identified themselves as

Black in the 2010 census paid more than $25 in total late fees for each account they held with

major issuers in 2019.

24

Yet it is also notable that the relationship is U-shaped, as cardholders in

areas where a small but non-zero share of the population identified as Black paid the least in

average late fees, less than $20.

FIGURE 8: AVERAGE LATE FEE IN 2019 AND SHARE OF POPULATION IDENTIFYING AS BLACK (Y-14,

CENSUS)

24

Our chart groups the census tracts into 42 equal-sized bins (in terms of number of trade lines in the Y-14) an d p l ots

each bin’s average total amount of late fees per account in 2019 against the bin’s average Black share. The line

merely connects these dots to help with interpolation.

$0

$5

$10

$15

$20

$25

$30

$35

$0 $20K $40K $60K $80K $100K $120K $140K $160K

Late fee per account

Local annual income per adult

$0

$5

$10

$15

$20

$25

$30

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100%

Late fee per account

Share of local population identifying as Black

11 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

Disparities in late fees are also related to broader measures of neighborhood functioning and

economic mobility. In some neighborhoods, more than 30 percent of children born in the early

1980s to poor parents (at the 25

th

percentile of their generation’s income distribution) made it to

the top 20 percent of their own generation by the mid-2010s; cardholders in these areas paid

$16 to $17 dollars in average late fees per credit card in 2019. In areas where only five percent of

similarly poor children rose to the top 20 percent, average late fees per account were more than

$25 per credit card in 2019, indicating lower credit card late fees in locations that foster good

outcomes for children.

25

FIGURE 9: AVERAGE LATE FEE IN 2019 AND INTERGENERATIONAL MOBILITY (Y-14, OPPORTUNITY

INSIGHTS)

As consumers in poorer areas tend to carry smaller balances when they are late on a payment,

the late fee they pay on top of a finance charge is typically a larger cost relative to their average

daily balance.

26

Consumers in the richest areas pay considerably less than one percentage point

more for this form of credit during months in which they incur a late fee (amounting to 8.5

25

Our chart grouped census tracts into 41 equal-sized bins (in terms of number of accounts in the Y-14) and plots the

bin’s average total amount of late fees per account against the bin’s average mobility measure. The line merely

connects these dots and is supposed to help with visual interpolation. Income ranks for parents and children are

both in terms of household income as observed in IRS tax records. For details on the definition and measurement of

the mobility measure, see Chetty et al., “The Opportunity Atlas: Mapping the Childhood Roots of Social Mobility,”

(Jan. 2020), https://opportunityinsights.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/atlas_paper.pdf

.

26

Finance charges are proportional to the average daily balance in the previous cycle, with the annualized APR

determining the ratio of the charge to the balance. Late fees are fixed amounts but could be expressed in similar

ratios, comparing this additional cost of credit to the APR. The issuer here is arguably lending the minimum

payment to cardholders who would have revolved the rest of their balance anyway or they are lending the entire

balance to would-be transactors who pay late. For more information on annual late fee volume and interest as a

percentage of cycle ending balances by credit score tier, see supra Figure 5.

$0

$5

$10

$15

$20

$25

$30

0% 5% 10%

15%

20% 25% 30% 35% 40%

Late fee per account

Share of local children born into 25th percentile reaching the top quintile

12 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

percent in APR terms, which are annualized), while consumers in poor areas pay close to two

percent extra during these months, or 24 percent annualized.

27

FIGURE 10: LATE FEE SHARE OF AVERAGE DAILY BALANCE, BY PER CAPITA INCOME, IN 2019 (Y-14, IRS)

27

Our chart bins ZIP codes into 80 equal-sized bins (in terms of number of trade lines in the Y-14) and plots each

bin’s weighted average of the ratio of the total amount of late fees over balances per account against the bin’s

average total income per adult. The line merely connects these dots to help with visual interpolation. ZIP-level

aggregates on total incomes and number of individuals come from the Statistics of Income of the Internal Revenue

Service.

0.0%

0.5%

1.0%

1.5%

2.0%

$0 $50K $100K $150K $200K

Late fee as a share of balance

Local annual income per adult

13 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

3. Market reliance

Even though late fees account for over 10 percent of total fees and interest collected annually

industry-wide, individual issuers’ revenue from credit card late fees varies. In the wake of the

CARD Act, late fees represent 99 percent of penalty fee volume on credit cards, as overlimit fees

are now practically nonexistent and fees for returned payments account for a negligible share.

28

For general purpose cards, late fees represented 45 percent of total consumer fees assessed in

2019 and seven percent of total interest and fees;

29

for private label cards in that same year, late

fees made up the overwhelming majority—91 percent—of all consumer fees and 25 percent of

total interest and fees.

30

Interchange fees paid by merchants are not included in the calculation

of total consumer fees, although they may indirectly affect consumers.

While private label and subprime specialist issuers represent a minority of accounts in the credit

card market, these issuers collect a disproportionate share of total late fee volume. Reliance on

late fees varies by the type of credit cards offered to consumers.

FIGURE 11: SHARE OF ACCOUNTS AND SHARE OF LATE FEE VOLUME BY ISSUER TYPE IN 2019 (Y-14+)

31

28

Y-14+; Credit Card Accountability Responsibility and Disclosure Act of 2009, Public Law 111-24, 123 Stat. 1734

(2009); CFPB, The Consumer Credit Card Market, at 96 and 97 (Dec. 2017) (2017 Report),

https://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/documents/cfpb_consumer-credit-card-market-report_2017.pdf

.

29

Total consumer fees include late fees, overlimit fees, non-sufficient funds (NSF) fees, cash advance fees, annual

fees, debt suspension fees, balance transfer fees, and other fees.

30

See 2021 report, supra note 3, at 53.

31

Y-14+ data provided in response to a series of data filing orders from a diverse group of specialized issuers

suppl ement the Y-14 for general purpose and private label accounts. All subprime specialist data are from these data

filing orders and do not include accounts represented in the Y-14.

63%

33%

4%

43%

46%

12%

General purpose mass market Private label Subprime specialist

0%

20%

40%

60%

Share of accounts Share of late fee volume

14 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

The share of late fees for individual issuers ranged from a minimum of four percent to a

maximum of 31 percent of total consumer charges in 2019. Among issuers there is a strong

correlation between reliance on late fees and concentration of subprime accounts. Late fees

account for a greater share of charges for issuers who service a higher percentage of subprime

accounts at almost 20 percent of total interest and fees. Conversely, late fees account for a

smaller share of about seven percent of total interest and fees for issuers whose cardholders

have higher average credit scores. Yet, the industry as a whole continues to rely on late fees as a

source of revenue.

TABLE 2: DISTRIBUTION OF ISSUERS IN Y-14+ SAMPLE BY SUBPRIME CONCENTRATION AND LATE FEE

CHARGES (Y-14+)

32

BELOW AVERAGE SHARE OF

SUBPRIME ACCOUNTS

ABOVE AVERAGE SHARE OF

SUBPRIME ACCOUNTS

BELOW AVERAGE SHARE OF

LATE FEE CHARGES

56% 6%

ABOVE AVERAGE SHARE OF

LATE FEE CHARGES

0% 38%

All but two of the top 20 issuers by outstanding balances contracted a maximum late fee at or

near the safe harbor amount of $40 in 2020.

33

However, the most common maximum late fee

charged in agreements submitted to the CFPB was $25, as driven by the practices of smaller

banks and credit unions not in the top 20 issuers by asset size.

34

32

Average share of late fee charges is 10 percent of total interest and fees. Average share of subprime accounts is 10

percent of total accounts.

33

This analysis only represents the maximum late fee found in all agreement submissions by a given issuer. Due to

limitations with the credit card agreement database, the CFPB cannot report what percentage of products or

consumers are covered by the late fee provisions submitted by a given issuer. Additionally, as many issuers emp loy

language in their agreements listing that fees for late payments are “up to” a given value, this analysis does not

explore variation in the first-time late fee. For listings of top credit card issuers by credit card loans, see Rica Dela

Cruz and Ronamil Portes, “Banks see credit card loans rise YOY in Q3 as spending further accelerates,” S&P Global

Mark et Intel ligence (Nov. 2021),

https://www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/news-insights/latest-news-

headlines/banks-see-credit-card-loans-rise-yoy-in-q3-as-spending-further-accelerates-67760858.

34

This analysis does not capture variation in issuer penalty pricing for first-time late payment and excludes practices

where an issuer may choose to waive a late fee for a given consumer. See e.g., Discover, “Discover Launches Game-

Changing New ‘It’ Credit Card” (Jan. 2013),

https://investorrelations.discover.com/newsroom/press-

releases/press-rele a se -details/2013/Di scover-Launches-Game-Chan gi ng-New-It-Credit-Card/default.aspx.

15 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

FIGURE 12: MAXIMUM LATE FEES IN CREDIT CARD AGREEMENTS BY ISSUER TYPE IN Q4 2020 (QCCA)

A handful of issuers currently offer credit card products with no late fees. For example, Citibank

has offered the Citi Simplicity card since 2011.

35

A newer entrant, the Petal 2 “Cash Back, No

Fees” card, first issued in 2018, does not charge late fees and is marketed to consumers with no

or limited credit.

36

Starting in 2019, consumers with an iPhone could apply for the no-fee Apple

card, issued by Goldman Sachs, and many did.

37

As of 2020, the product had over six-million

users, and Goldman Sachs’ credit card loans exceeded $6 billion in Q3 2021.

38

Together, these

examples may indicate a small but growing trend towards issuers offering products with no or

limited fees for late payment; yet, credit cards without late fees remain the exception, not the

rule.

35

Citigroup, “Citi Simplicity® Says Goodbye to Frustration of Late Fees in New Advertising Campaign” (May 2013),

https://www.citigroup.com/citi/news/2013/130514a.htm#:~:text=First%20introduced%20in%20July%202011,No

%20Late%20Fees.

36

Petal, “Petal 2,” https://www.petalcard.com/petal-2 (last accessed Feb. 2022); PYMNTS, “Petal Debuts No-Fee

Credit Card for Underserved” (Oct. 2018), https://www.pymnts.com/news/payment-methods/2018/petal-no-fee-

credit-card-startup/.

37

Apple, “Introducing Apple Card, a new kind of credit card created by Apple” (Mar. 2019),

https://www.apple.com/newsroom/2019/03/introducing-ap pl e-card-a-new-kind-of-credit-card-created-by-apple/

.

38

Ron Shevlin, “Apple Card Grows to 6.4 Million Cardholders Thanks to Women,” Forbes (May 2021),

https://www.forbes.com/sites/ronshevlin/2021/05/04/apple-card-grows-to-64-million-card holde rs-thanks-to-

women/?sh=1131c55b2f57; Dela Cruz and Portes, supra note 33.

8

30

42

54

232

46

74

80

2

$0-$5 $6-$10 $11-$15 $16-$20 $21-$25 $26-$30 $31-$35 $36-$40 Over $40

0

50

100

150

200

Banks (excluding top 20 issuers)

Credit unions Top 20 issuers

16 CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION BUREAU

4. Conclusion

This report shows the credit card market continues to rely on late fees that negatively affect

millions of consumers. For some households, late fees are a costly mistake for payments that

may only be a day or two late; for others, they are a significant added hardship during a time of

financial precarity. For credit card companies, especially private label and subprime specialist

issuers, late fees continue to bolster their bottom line.

During the pandemic, many families received a temporary reprieve from the burden of credit

card late fees. Yet in spring 2022, as widespread public and private relief efforts have largely

ended, late fee volume is on a path to return to 2019 levels. This report documents that most of

the largest issuers set penalty fees at or near the maximum level eligible for safe harbor

treatment under current regulation, a limit annually adjusted for inflation. As limits increase,

late fees’ impact on consumers will likely remain substantial unless something in the credit card

market changes.