Future U.S. Presidents in Tallinn:

From John Quincy Adams to John F. Kennedy

Much has been written about Senator Hillary Clinton and Senator John McCain's August 2004

visit to Tallinn in anticipation that one of them might become the next President of the United

States. But no matter who wins the upcoming U.S. Presidential elections on November 4,

neither McCain nor Clinton (who also visited Tallinn when she was First Lady in July 1996) has

any chance of becoming the first U.S. President to have visited Tallinn before taking office. That

honor belongs to John Quincy Adams (1767-1848), son of the second U.S. President John

Adams. John Quincy Adams visited Reval in May 1814 before going on to become the sixth U.S.

President in 1825. And even if we would limit ourselves to the independent Republic of Estonia,

then the honor would go to John Fitzgerald Kenney (1917-1963) who visited Tallinn in May

1939 before going on to become the thirty-fifth U.S. President in 1961.

1814: John Quincy Adams Visits Reval

John Quincy Adams

After serving as the junior U.S. Senator from Massachusetts from 1803 to 1808, Adams was

appointed to be the first U.S. Minister to the Russian Empire and presented his credentials to

Tsar Alexander on November 5, 1809. Adams earned his new position thanks to his earlier

experience in the region. From 1780 to 1783 while still in his teens, Adams served as the

secretary and translator for Minster Francis Dana when the unrecognized American Republic

unsuccessfully sought to gain Russian support during its War of Independence (1776-1783)

from Great Britain. After returning in the official capacity of U.S. Minister, Adams would remain

in St. Petersburg until April 1814 when he was put in charge of the U.S. Commission to

negotiate the Treaty of Ghent (1814) which brought about an end to the War of 1812, the new

American Republic's second war with Great Britain.

After his assignment as the U.S. Minister in London to the Court of St. James (1815-1817), the

fifth U.S. President James Monroe appointed Adams to be his Secretary of State. Adams served

as Secretary of State from 1817 to 1825 when he became the sixth U.S. President after the

disputed election of 1824. While Secretary of State, Adams helped draft one of the U.S.

Government's first foreign policy statements that would become known as the Monroe

Doctrine. The Monroe Doctrine stated that European powers should not interfere in the

domestic affairs of the Americas.

While he may have made earlier trips to the Russian imperial province of Esthonia during his

two tenures in St. Petersburg, Adams traveled to Reval by land in the spring of 1814 in order to

deal with a consular management problem. The local U.S. Consular Agent in Reval – a Baltic-

German named Diedrich Rodde – had accused the U.S. Consul in St. Petersburg – Levett Harris

of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania – of corruption. While the War of 1812 meant that no U.S. ships

had made it to Baltic ports for two years, Consul Harris continued to demand a “pension” from

Rodde. This and other charges of corruption eventually prevented Consul Harris from becoming

U.S. Minister to Russia despite – or because of – his long service in Russia.

In 1803, Consul Harris was the first official U.S. representative posted to St. Petersburg, Russia.

He also served several times as the U.S. Chargé d'Affaires during Adams' occasional absences

from post and after the Minister's departure. Adams would later write the following about

Harris: “He made a princely fortune by selling his duty and his office at the most enormous

prices.” Harris was released from public service in 1816 and never called back. He was

embroiled in a variety of different law suits for years to come.

As it happens, Adams kept an extensive diary, detailing the three weeks he spent in Reval from

May 1 to 20 waiting for the ice in the Gulf of Finland to clear – including a failed attempt to

leave the city on May 16. Adams appears to have been charmed by Reval. The May 7 entry in

his diary reads: “I walked entirely around the city, entering at the same gate by which I had

gone out. I was forty seven minutes in completing it, and conclude the circle to be exactly four

wersts, or two and two-thirds miles. There are seven gates at irregular distances from one

another, and empty moat, and a wall flanked with towers. The city is very old, and built in the

Gothic style; the streets narrow and crooked; the buildings generally of brick, and plastered,

and a few of stone. The roofs of the houses are of tiles, and in sharp, steep angles; the ends of

the houses upon the streets. One seems to be transported back to the twelfth century in such

a place."

On May 14, he visited Kadriorg, describing it as “a palace about a mile without the city, built by

Peter the First for his Empress Catherine. The house is small, but the gardens are extensive and

laid out in the fashionable style of that time. There are three bricks at one corner of the house,

painted red, which are said to have been laid by Peter himself. The rest of the house is

plastered. It is the usual residence of the Prince of Oldenburg, the Governor-General of these

provinces. But he is now absent. Round the gardens there is a little village of barracks for a

regiment of soldiers; and on a hill beyond the gardens stands a light-house. There are five

lamps placed in a chamber at the front of which is a door opening upon the gulf; and one lamp

at the door itself. It is the highest land in the neighborhood of Reval, and a fine prospect of the

city, the harbor, the gulf, and country around. We saw a small vessel coming into the harbor,

the first that has appeared this season. The harbor, and the gulf beyond it, are still covered

with ice, but not in very large masses, and it appears that the gulf is navigable.”

In addition to making various official calls and witnessing Russia celebrating its victory over

Napoleon, Adams also got a chance to observe the every day life of Esthonia's elite: he went to

the opera and a ball, dined with merchants and played cards with government officials, and

even went to a public bath. On his first Sunday he attended a German-language service at the

Dome Cathedral while the next Sunday he went to another church to hear an Estonian-

language service. Adams also walked all over the city, admiring the view from Toompea several

times: “Towards evening, I walked … to the Dome – a hill upon which stands the castle of the

city, and from which there is a fine prospect of the harbor and gulf, with the neighboring islands

and the country around the city.” His extensive and insightful observations provide a fascinating

window on life in Estonia back in 1814.

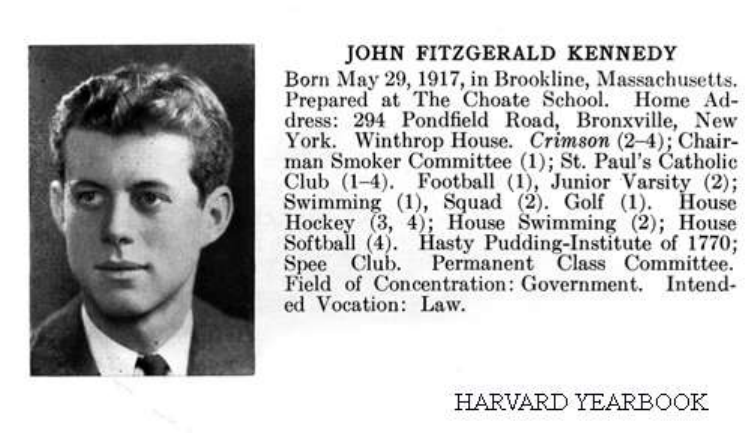

1939: John Fitzgerald Kennedy Visits Tallinn

Exactly 125 years later in May 1939, another American born into a good family near Boston,

Massachusetts visited Estonia. While still an undergraduate student at Harvard College (John

Quincy Adams' alma mater), John Fitzgerald Kennedy took a semester off during his junior year

to spend seven months working and traveling around Europe. His father Joseph P. Kennedy, the

U.S. Ambassador to Great Britain at the time, helped make the arrangements by writing his

colleagues across Europe.

The society pages of major U.S. newspaper were full of the news. On January 24, 1939, the

Christian Science Monitor reported: “Believing that actual working experience in diplomatic

circles abroad will give him the answer as to whether or not he wants to enter Government

service after graduation from college, John F. Kennedy, second son of the United States

Ambassador to the Court of St. James, will leave Harvard next week for American legations of

Paris and London. The younger Kennedy plans to go directly to the Paris legation where he will

spend a month and a half. Then he expects to go to London. He isn't sure yet what he will do.

'You might call me a glorified office boy,' he said.” The New York Times printed a similar story

the same day while the Los Angeles Times followed suit the next.

Next, U.S. newspapers reported on Kennedy's actual departure for Europe. In its “who is who”

list of “Ocean Travelers” of February 25, 1939, the New York Times lists John F. Kennedy right

after the Lord and Lady Kemsley but before other notable fellow passengers including virtuoso

violinist Yehudi Menuhin. Although traveling on a different ship, the same list of travelers also

includes former U.S. Minister to Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania Arthur Bliss Lane who was

returning to his current posting as U.S. Minister to Yugoslavia. The New York Times followed up

the next day with another article: “John F. Kennedy, a son of the United States Ambassador to

Great Britain, sailed yesterday on the Cunard White Star liner Queen Mary. He said that he was

taking a half-year's leave from his studies at Harvard to work in the United States Embassies in

Paris and London. Mr. Kennedy said he would return to Harvard next Fall. He added that he had

'made up his studies' for the last half of his junior year.”

Although some U.S. diplomats welcomed the young Kennedy's visit as was the case with U.S.

Minister to Estonia and Latvia John C. Wiley and his wife Irena, others were much less

enchanted by the young college student who was known to his friends as “Jack.” In his Memoirs

(1967), Minister Wiley's colleague and former Tallinn Vice Consul George F. Kennan wrote: “we

received a telegram [at the U.S. Legation in Prague] from the embassy in London, the sense of

which was that our ambassador there, Mr. Joseph Kennedy, had chosen this time [August 1939]

to send one of his young sons on a fact-finding tour around Europe, and it was up to us to find

means of getting him across the border and through German lines so that he could include in

his itinerary a visit to Prague.”

Kennan continues: “We were furious. Joe Kennedy was not exactly known as a friend of the

career [U.S. foreign] service, and many of us, from what we had heard about him, cordially

reciprocated this lack of enthusiasm. His son had no official status and was, in our eyes,

obviously an upstart and an ignoramus. The idea that there was anything he could learn or

report about conditions in Europe which we did not already know and had not already reported

seemed (and not without reason) wholly absurd. That busy people should have their time taken

up by arranging his tour struck us as outrageous. With that polite but weary punctiliousness

that characterizes diplomatic officials required to busy themselves with pesky compatriots who

insist on visiting places where they have no business to be, I arranged to get him through

German lines, had him escorted to Prague, saw to it that he was shown what he wanted to see,

expedited his departure, then, with a feeling of 'that's that,' washed my hands of him – as I

thought.”

Kennan's Memoirs are wonderful in that they are filled with the insights of an older man

commenting on the arrogant youth he once was. After he had served as the U.S. Ambassador to

Yugoslavia from 1961 to 1963 at President Kennedy's request, Kennan goes on to write: “Had

anyone said to me then that the young man in question would some day be the President of

the United States and that I, in the capacity of chief of a diplomatic mission, would be his

humble and admiring servant, I would have thought that either my informant or I had taken

leave of our senses. It was one of the great lessons of life when memory of the episode

returned to me as I sat one day in my Belgrade office, many years later, and the truth suddenly

and horribly dawned. By such blows, usually much too late in life, is the ego gradually cut down

to size.”

At Home With the Wileys in Riga and Tallinn

Unlike Kennan, U.S. Minister John C. Wiley and his wife Irena took an immediate liking to the

young Kennedy as soon as he arrived in Riga and made him their house guest. In her memoirs

Around the Globe in 20 Years (1962), Irena Wiley – a gifted sculptor – writes: "Jack, then a

youngster, visited us in Riga while I was doing an altar of St. Therese of Lisieux, my favorite

saint. The altar consisted of small panels depicting the life of the saint. In one of these an angel

leans over her, while she is writing the book that made her beloved even by non-Catholics. I

needed a model for the angel, and Jack with his curly hair and his youthful serenity of

expression was literally God-sent. He sat for me, patiently, and is rewarded by having the

privilege of being the only American President with his likeness in the Vatican, where the altar

is now."

The Wileys also arranged for the young Kennedy to visit Estonia in mid-May. Minister Wiley and

his wife Irena traveled to Tallinn on May 19 after crossing the border in Valga in order to be

there for young Kennedy's arrival. Kennedy showed up three days later on May 22 at the Tallinn

airport on a Polish airplane with the call sign SP-BGK. While the flight originated in Warsaw, the

plane usually made stopovers in Riga and Köningsberg. During his short two-day stay in Tallinn,

Kennedy most likely would have been the Wileys' house guest as he was in Riga. This means he

would have stayed at their residence at Vabaduse väljak no. 7 – the present day home of the

Tallinn City Government. Unfortunately, Kennedy did not keep a diary of his 1939 European

tour and no Estonian newspaper of the day realized the potential importance of the Wileys'

young house guest. The only people who recorded Kennedy's visit to Estonia were the Estonian

Border Guards who first noted his arrival and then his departure from the country on May 24,

1939 through the Narva border crossing. A Soviet diplomatic courier was the only other person

to leave Estonia via Narva that day. Both men were headed to Soviet Russia, the next country

on Kennedy's European tour.

In addition to visiting Estonia, Latvia, the Soviet Union, England, France, Nazi Germany, and

Czechoslovakia, Kennedy's stops that summer also included Lithuania, Poland, Hungary,

Romania, Turkey, Egypt, and Palestine. In Europe to witness the start of World War II when Nazi

Germany invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, young Kennedy received a thorough political

education that summer. He made his way back to the United States safely on September 21

aboard Pan American's Dixie Clipper airliner. The next day the New York Times published a

photo of the smiling Kennedy and reported: “John Kennedy, 22-year-old son of Joseph P.

Kennedy, United States Ambassador to Great Britain, was among the [Dixie Clipper's]

passengers. Mr. Kennedy, who traveled on a diplomatic passport, had been helping his father.

He is returning to Harvard to enter his senior year.”

To fulfill his 1940 graduation requirements for Harvard, Kennedy wrote his senior thesis on

Great Britain's appeasement of Nazi Germany in Munich, based largely on the information he

gathered during his 1939 European tour. At the encouragement of his father, Kennedy would

convert his thesis into a bestselling book called Why England Slept (1940). After becoming an

accidental war hero in the South Pacific during World War II after his torpedo boat – the PT-109

– was hit by a Japanese destroyer, Kennedy would go on to become a U.S. Congressman from

Boston in 1946 and then the junior U.S. Senator from Massachusetts in 1952. Kennedy went on

to win the 1960 U.S. Presidential election. He served in office from January 20, 1961 until his

assassination on November 22, 1963.

During his short two-day stay in Tallinn, Kennedy stayed at the Wiley's residence at Vabaduse

väljak 7 - the present day home of the Tallinn City Government. (Photo from the Estonian Film

Archives)