Carrie Lou Garberoglio, Jeffrey Levi Palmer,

Stephanie Cawthon, and Adam Sales

NDC

National Deaf Center

on Postsecondary Outcomes

DEAF PEOPLE AND EMPLOYMENT

IN THE UNITED STATES: 2019

This report was developed under a jointly funded grant through the US Department of Education’s Ofce of Special

Education Programs (OSEP) and the Rehabilitation Services Administration (RSA), #HD326D160001. However, the

contents do not necessarily represent the positions or policies of the federal government.

©2019 National Deaf Center on Postsecondary Outcomes

Deaf People and Educational Attainment in the United States: 2019

Licensed under Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0

INTRODUCTION

Employment is one of many possible outcome

measures, but one that is typically used as an

indicator for the ability to live independently, attain

nancial stability, and maintain a quality of life

that is aligned with one’s goals. To meet national

employment goals, federal initiatives, policies, and

funding drive employment training, placement,

and rehabilitation programs across the country.

Despite positive postsecondary enrollment trends

and improvements in legal policies surrounding

access for deaf people, particularly through the

Americans with Disabilities Act, employment

gaps between deaf and hearing people continue

to be signicant. Employment experiences for

deaf people are also qualitatively different than

for hearing people in the United States in terms

of earnings, part-time or full-time employment,

opportunities for advancement over time, and the

likelihood of being self-employed.

This updated report provides a comprehensive

overview of the most current data on employment

trends and trajectories for deaf people in the

United States, serving as a resource for commu-

nity members, advocates, educators, researchers,

and policy makers. Data from the 2017 American

Community Survey (ACS), a national survey con-

ducted by the U.S. Census Bureau, was used in

this report. Data from 2017 reects current trends,

while 2008-2017 data was used to explore how

employment trends have changed over time.

We limited our sample to people aged 25 to 64

years old, or what is typically considered the

“working age” population. People who identied

as having any type of hearing loss were included

in these analyses. Further information about

this dataset and the analyses are shared in the

Methods section of this report.

Key ndings:

• 53% of deaf people were employed in 2017.

• Deaf people are actively looking for work to a

greater extent than hearing people.

• A large percentage of deaf people are not in the

labor force.

• Deaf people who are employed full time report

median earnings that are comparable to hearing

people.

• Employment rates for deaf people have not

increased from 2008 to 2017.

• Educational attainment appears to narrow

employment gaps.

• Deafdisabled people are most likely

to experience pay inequality and

underemployment.

In this report, the term deaf is used in an all-inclusive manner, to include people who may identify as deaf,

deafblind, deafdisabled, hard of hearing, late-deafened, and hearing impaired. NDC recognizes that for

many people, identity is uid and can change over time or with setting. NDC has chosen to use one term,

deaf, with the goal of recognizing experiences that are shared by people from diverse deaf communities

while also honoring their differences.

3

Deaf People and Employment in the United States: 2019

It is necessary to recognize the many

intersecting identities of deaf people when

thinking about employment experiences and

outcomes.

GENERAL EMPLOYMENT DATA

The employment gap between deaf and hearing

people in the United States is a signicant area of

concern. In 2017, only 53.3% of deaf people were

employed, compared to 75.8% of hearing people.

This is an employment gap of 22.5%.

A common assumption is that if 53.3% of

deaf people are employed, 46.7% of deaf people

are unemployed. This is incorrect. The federal

government describes people without a job as

people who are unemployed or not in the labor

force. People who reported being currently,

or recently, looking for work, are counted as

unemployed. People who are not currently

employed, and are not looking for work, are

counted as not in the labor force. This latter

group may include students, parents, caretakers,

or retired people, for example.

Deaf and hearing people have unemployment

rates of 3.8% and 3.4%, respectively. This

difference, while small, is statistically signicant.

This suggests that deaf people are more likely to

be actively looking for work than hearing people.

The largest disparity between deaf and hearing

people, however, is that of labor force involve-

ment. A large number of deaf people (42.9%)

were not in the labor force, compared to 20.8%

of hearing people (Figure 1). We will talk about

this group in more detail later on in this report.

4

Deaf People and Employment in the United States: 2019

Figure 1

RATES OF UNEMPLOYMENT, EMPLOYMENT, AND NOT IN THE LABOR FORCE

3.8%

UNEMPLOYED

53.3%

EMPLOYED

42.9%

NOT IN LABOR

FORCE

DEAF

PEOPLE

20.8%

NOT IN LABOR

FORCE

75.8%

EMPLOYED

3.4%

UNEMPLOYED

HEARING

PEOPLE

From 2008 to 2017, employment rates have

increased by a small, yet signicant, amount

for hearing people, but did not increase for

deaf people (Figure 2). The gure shows

employment declines from 2008 to 2010.

These declines may be inuenced by the

economic recession in the United States

occurring at that time. Greater growth in

employment rates for deaf people is needed

in order to narrow the employment gap

between deaf and hearing people, and this

is not happening yet.

5

Deaf People and Employment in the United States: 2019

Figure 2

EMPLOYMENT RATES FROM 2008 TO 2017

DEAF

PEOPLE

HEARING

PEOPLE

2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017

80%

70%

60%

50%

40%

76.6%

55.9%

73.6%

52.7%

72.3%

49.5%

72.4%

49.4%

73%

50.2%

73.4%

50.9%

74.1%

51%

74.6%

51.7%

75.2%

51.9%

75.8%

53.3%

When considering work status, deaf people are

more likely to work part-time than their hearing

counterparts (Figure 3).

Among people who are employed, a higher

percentage of deaf people than hearing people

are self-employed (11.6% vs. 9.8%) or business

owners (4.1% vs. 3.8%). The higher incidence of

self-employment and business ownership may

be an effective strategy to bypass challenges

and biases in the workplace that deaf people are

deeply familiar with.

If deaf people work full-time, they report similar

median annual earnings as their hearing peers,

$50,000 and $49,900, respectively. Half the

population earn more than the median, and

half earn less. However, employment rates

and median annual earnings vary widely within

deaf communities, just as it does in the hearing

population. We will be discussing this in more

detail throughout this report.

6

Deaf People and Employment in the United States: 2019

Figure 3

WORK STATUS

77.4%73.4%

HEARING

PEOPLE

DEAF

PEOPLE

26.6% VS. 22.6%

FULL-TIME FULL-TIME

PART-TIME

DEAF

PEOPLE

$50,000

11.6%

DEAF PEOPLE ARE

SELF-EMPLOYED

4.1%

DEAF PEOPLE

OWN BUSINESSES

HEARING

PEOPLE

$49,900

9.8%

HEARING PEOPLE ARE

SELF-EMPLOYED

3.8%

HEARING PEOPLE

OWN BUSINESSES

7

Deaf People and Employment in the United States: 2019

Close to half (42.9%) of deaf people between

the ages of 25 and 64 are not working or looking

for work. However, not all deaf people participate

in the labor force at similar rates. People

experience different opportunities and barriers

that are related to their intersecting identities,

and that becomes visible when looking at labor

force participation rates across race, gender,

and ethnicity (Figure 4, next page). For example,

61.1% of deaf men versus 50.5% of deaf women

are in the labor force, a statistically signicant

difference. Also, only 44.8% of deaf African

Americans and 43.6% of deaf Native Americans

are in the labor force, compared to 59% of

deaf Whites. Average labor force participation

rates drop by 12.3% for African Americans,

13.5% for Native Americans, and 18.1% for

deafdisabled people.

By far the largest difference between those

deaf people who are and are not in the labor

force is the presence of additional disabilities.

Overall, 75.5% of deaf people without an additional

disability were in the labor force, while only 39%

of deafdisabled people were in the labor force, a

statistically signicant difference.

An understanding of how labor force participation

rates vary within the population of deaf people

can help researchers, policy makers, and

educators design policies and practices that

take those differences into account. Ultimately,

further research is needed to understand why

large numbers of deaf people have opted out of

the labor force.

LABOR FORCE PARTICIPATION

57.1%

Overall Deaf people

in the labor force

44.8%

Deaf African

Americans in

the labor force

39%

Deafdisabled

people in the

labor force

43.6%

Deaf Native

Americans in

the labor force

8

Deaf People and Employment in the United States: 2019

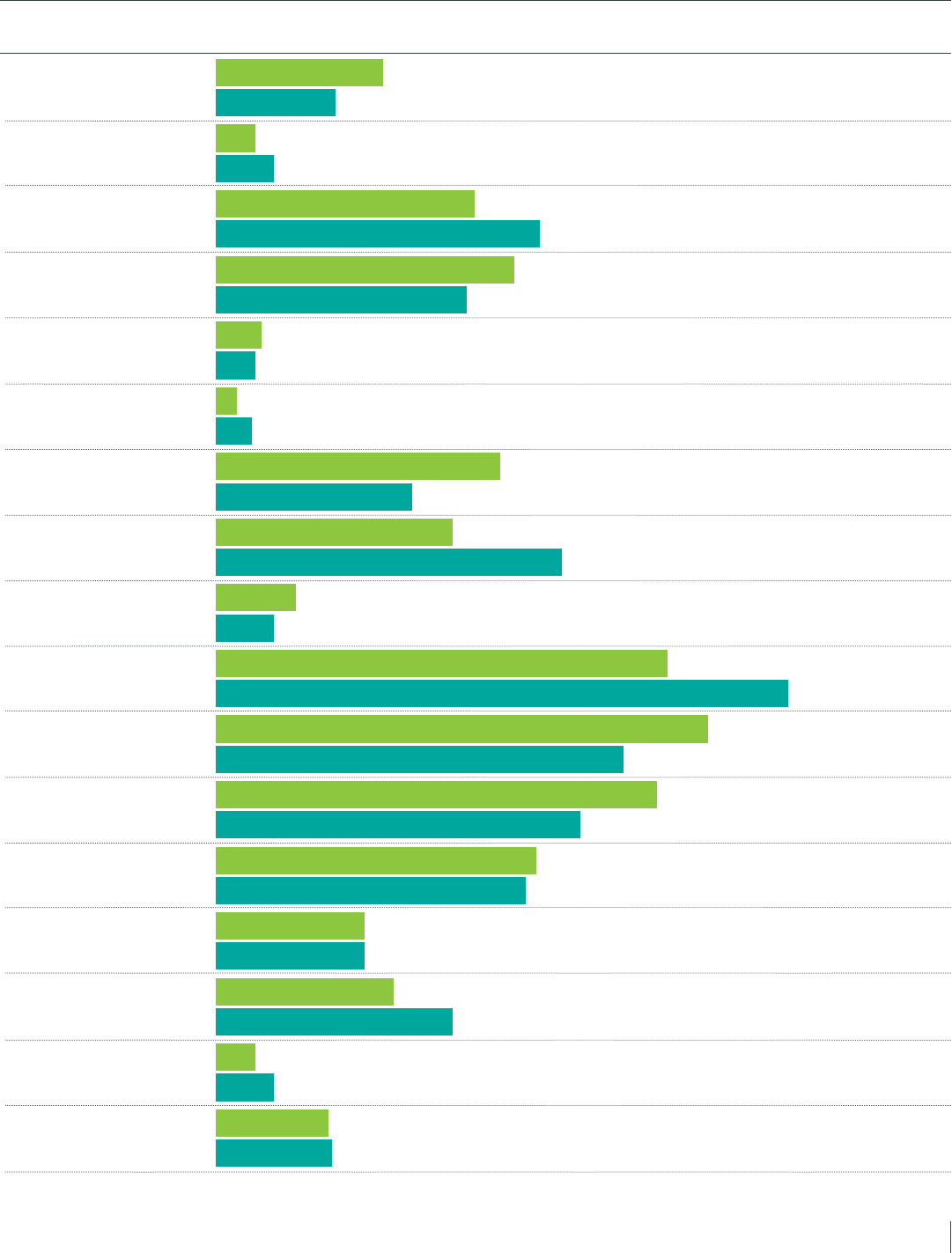

MEN

49.5%

38.9%

61%

34.5%

41%

55.2%

48.7%

56.4%

31.6%

29.1%

43.5%

51.7%

33.8%

20.4%

22.9%

20.2%

18.7%

14.5%

26.8%

WOMEN

DEAFDISABLED

DISABLED

IS A PARENT

WHITE

AFRICAN-AMERICAN

MULTI-RACIAL

NATIVE AMERICAN

VETERAN WITH A SERVICE-RELATED DISABILITY

BETWEEN 55 AND 64 YEARS OLD

Figure 4

PEOPLE NOT IN THE LABOR FORCE

58.6%

DEAF

PEOPLE

HEARING

PEOPLE

9

Deaf People and Employment in the United States: 2019

The largest employment disparities were found

for deafdisabled people. In this dataset, 50% of

the deaf population had some sort of additional

disability, each combination of which results in

unique strengths and challenges. Employment

rates and median annual earnings vary across

type of disability.

Only 35% of deafdisabled people reported being

employed in 2017 compared to 71.9% of deaf

people without disabilities, an employment

gap of 36.9%. Among deaf people who worked in

2017, more deafdisabled people work part-time

than deaf people without additional disabilities

(33.4% vs. 23.2%).

Among the deafdisabled population, employment

rates differ greatly by disability type. Deafblind

people report the highest employment rates,

while deaf people that may need additional

support with independent living skills and self

care report the lowest employment rates.

Deaf people with any type of additional disability

earn $4,000 less per year, on average, than their

deaf peers without an additional disability

(Table 1). Some groups of deafdisabled people

experience far greater earning disparities, earning

as much as $10,000 less than deaf people without

additional disabilities. Recall that median annual

earnings were calculated only from people who

were working full-time. Thus, these data points

about earnings do not reect the number of

deafdisabled people who are not working full time.

In these analyses, we were limited to the

disability categories that are used by the U.S.

Census, which does not recognize group identity

preferences or differences within broad disability

categories. The U.S. Census focuses on functional

abilities, and does not attend to more complex

issues surrounding identity. This is a limitation

of this dataset. However, at a minimum, it is

necessary to recognize that deafdisabled people

are more likely to experience wage inequality and

underemployment.

Table 1

EMPLOYMENT RATES AND EARNINGS BY ADDITIONAL DISABILITY STATUS

ADDITIONAL DISABILITY STATUS MEDIAN SALARY EMPLOYMENT RATES

Deaf + no additional disabilities $50,000 71.9%

Deaf + ambulatory disability $44,000 23.7%

Deafblind $43,700 34.6%

Deaf + cognitive disability $42,000 27.2%

Deaf + independent living difculty $40,000 19.9%

Deaf + self care difculty $42,000 20.7%

EMPLOYMENT AMONG DEAFDISABLED PEOPLE

10

Deaf People and Employment in the United States: 2019

The intersections of race, ethnicity, and gender

are important factors to consider when thinking

about employment experiences and outcomes

for deaf people. In this report, the data for Pacic

Islanders, Native Americans, and people of other

races and multiple races are drawn from very

small samples, which may not be reective of real

population data. Data from these groups should

be interpreted cautiously (Figure 5, next page).

Overall, disparities between men and women

are similar in the deaf and hearing populations.

The employment gap between men and women

is 11.8% among hearing people and 10.6% among

deaf people. Gender gaps in employment are not

signicantly different between deaf and hearing

people. However, the wage gap is signicantly

larger for deaf women. Deaf women earn 77 cents

for each dollar that deaf men earn, while hearing

women earn 83 cents for each dollar that hearing

men earn (Figure 6, next page).

Race and ethnicity affects employment

opportunities and experiences for all people in

the United States, deaf or hearing. As in the

general population, deaf people who are white

or Asian report higher income and employment

rates. Lower employment rates are reported by

Native American and African American deaf and

hearing people.

When exploring the intersection of gender with

race and ethnicity, we see that income and

employment rates vary widely. For example, for

each dollar a white deaf person earns, a Latinx

deaf woman earns 64 cents and an Asian woman

earns 90 cents. In general, some of the lowest

income and employment rates are found among

Pacic Islanders and Native American deaf

women. For the most part, employment and

income trends are similar for hearing and deaf

people across race, ethnicity, and gender.

However, the gender gap in employment between

men and women seems to be narrower for deaf

people than for hearing people of these races

and ethnicities: Asians, Latinxs, whites, and

other races.

EMPLOYMENT EXPERIENCES BY RACE, ETHNICITY, AND GENDER

(continued on page 11)

For each dollar a white deaf man earns …

an Asian deaf

man earns

an African

American deaf

man earns

an Asian

deaf woman

earns

a white

deaf woman

earns

a Latinx

deaf man

earns

an African

American

deaf woman

earns

a Native

American

deaf woman

earns

a Latinx

deaf woman

earns

90¢ 81¢

81¢

74¢

72¢ 63¢ 59¢ 58¢

11

Deaf People and Employment in the United States: 2019

MEN

MEN

MEN

MEN

MEN

MEN

MEN

MEN

MEN

WOMEN

WOMEN

WOMEN

WOMEN

WOMEN

WOMEN

WOMEN

WOMEN

WOMEN

OVERALL

WHITE

AFRICAN-AMERICAN

NATIVE AMERICAN

ASIAN

PACIFIC ISLANDER

HISPANIC / LATINX

MULTI-RACIAL

OTHER RACE

MEN

MEN

MEN

MEN

MEN

MEN

MEN

MEN

MEN

WOMEN

WOMEN

WOMEN

WOMEN

WOMEN

WOMEN

WOMEN

WOMEN

WOMEN

OVERALL

WHITE

AFRICAN-AMERICAN

NATIVE AMERICAN

ASIAN

PACIFIC ISLANDER

HISPANIC / LATINX

MULTI-RACIAL

OTHER RACE

Figure 5

EMPLOYMENT RATES

BY RACE, ETHNICITY, AND GENDER

Figure 6

MEDIAN EARNINGS

BY RACE, ETHNICITY, AND GENDER

53.3%75.8%

$50,000$49,900

81.9

57.3

55.8

59.3

49.5

38.7

39.3

55.7

43.1

52.7

45.1

48.8

74.4

75.1

75.2

73.7

76.3

62

40.2

36.9

46.3

59

51.8

60.1

19.1

59.1

43.2

49.8

39.7

51

45.6

28

72.1

70.5

64.8

59.5

85.8

68.1

80.1

67.6

85.2

65.1

79.8

70.7

82.7

67

71.2

71.7

75.8%

77.1

82.6

46.770.1

53.3% $50,000

$50,000

$40,000

$53,000

$40,000

$39,000$45,000

$50,000

$38,800 $40,000

$35,400

$50,000$41,000

$50,000 $44,617

$39,000

$60,000

$52,000

$40,000

$55,000

$41,000

$45,000

$52,000

$50,000

$38,200

$40,000

$32,100

$47,700

$30,500

$57,400

$25,100

$37,300

$45,000

$32,500

$35,000

$52,000

$60,000

$47,000

$40,000

$37,000

$42,000

$35,000

$70,000

$53,000

$45,000

$38,000

$32,000

$55,000

$44,200

$48,900

$40,000

$36,000

$43,000

$49,900

100 $70,0000 0

HEARING

PEOPLE

DEAF

PEOPLE

HEARING

PEOPLE

DEAF

PEOPLE

12

Deaf People and Employment in the United States: 2019

Employment experiences are closely tied to

people’s level of educational attainment.

Employment rates of deaf people increase as

their educational attainment increases, from

31.7% for those who did not complete a high

school education, to 74.4% for those with a

masters’ degree. This increase in employment

rates is also found in the general population.

However, the employment gap between hearing

and deaf people narrows as educational

attainment increases (Figure 7). The largest

employment gap between deaf and hearing

people is found in people who did not complete

high school education (26.3%), and the smallest

employment gap is found among people with a

master’s (12%) or a bachelor’s degree (12.8%).

For deaf people with college degrees, the eld

of those degrees plays a meaningful role in

their employment possibilities. Deaf people

with degrees in the following elds: computers,

mathematics, and statistics, liberal arts/history,

and the arts, had the highest employment rates,

of over 75%. The least-employed elds were

psychology and multidisciplinary studies, with

employment rates around 60%.

Hearing people with degrees in the sciences,

communications, and business, had the

highest employment rates, of over 85%. The

least-employed degrees include education,

literature/languages and the arts, with employ-

ment rates around 80%. As you might expect, the

most-employed and least-employed degrees are

not the same for deaf and hearing people.

EDUCATIONAL ATTAINMENT AND EMPLOYMENT

Figure 7

EMPLOYMENT BY EDUCATION LEVEL

LESS THAN

HIGH SCHOOL

HIGH SCHOOL

DIPLOMA / GED

SOME

COLLEGE

ASSOCIATE’S

DEGREE

BACHELOR’S

DEGREE

MASTER’S

DEGREE

PH.D.,

J.D. OR M.D.

58%

70.2%

75.7%

80.1%

83.3%

86.4%

90.1%

31.7%

48.6%

56%

63.9%

70.5%

74.4%

72.4%

DEAF

PEOPLE

HEARING

PEOPLE

100%

80%

60%

40%

20%

26.3% gap

21.6%

19.7%

16.2%

12.8%

12%

17.7%

(continued on page 13)

13

Deaf People and Employment in the United States: 2019

Median annual earnings vary widely, depending

on eld of degree and level of educational

attainment. Deaf people’s median annual

earnings increase as their educational attainment

increases, just as in the general population

(Figure 8). This may indicate that once deaf

people have obtained specialized degrees and full

time employment, they have the same earning

power as hearing people. Again, recall that these

data points exclude people who are not working

full time, or those who have left the labor force.

Earnings also vary by eld of degree. Deaf people

with degrees in STEM elds reported median

annual earnings between $75,000 and $93,500,

while deaf people with degrees in multidisciplinary

elds, art, education, psychology, literature and

languages reported median annual earnings

between $50,400 and $56,000.

Figure 8

MEDIAN ANNUAL EARNINGS BY EDUCATIONAL ATTAINMENT

LESS THAN

HIGH SCHOOL

HIGH SCHOOL

DIPLOMA / GED

SOME

COLLEGE

ASSOCIATE’S

DEGREE

BACHELOR’S

DEGREE

MASTER’S

DEGREE

PH.D.,

J.D. OR M.D.

$33,000

40,000

47,400

50,000

63,000

$30,000

36,500

42,000

46,000

62,000

80,000

100,000

80,000

98,000

DEAF

PEOPLE

HEARING

PEOPLE

$100K

80

60

40

20

14

Deaf People and Employment in the United States: 2019

People in the United States work in a wide range of elds, and the most

common elds of work appear to be different for hearing and deaf people.

The most common occupational eld for hearing people is the medical industry,

with 13.8% of hearing people employed in this eld; while the least common

eld is in extraction, with 0.6% of hearing people employed in this eld. On the

other hand, for deaf people, the most common eld is manufacturing, with

15.7% of deaf people employed in this eld, and the least common eld is

extraction, with 1.0% of deaf people working in this eld (Figure 9, next page).

EMPLOYMENT RATES ACROSS OCCUPATIONAL FIELDS

HEARING

PEOPLE

DEAF

PEOPLE

Top 5 Occupations

1

2

3

4

5

REGISTERED

NURSES

ELEMENTARY AND MIDDLE

SCHOOL TEACHERS

RETAIL

SUPERVISORS

RETAIL

SUPERVISORS

JANITORS AND

BUILDING CLEANERS

DELIVERY TRUCK

DRIVERS

MANAGERS

DELIVERY TRUCK

DRIVERS

MANAGERS

REGISTERED

NURSES

3.7% 3.8%

3.5% 2.5%

2.4% 2.4%

2.0% 2.4%

1.6% 2.3%

(continued on page 15)

15

Deaf People and Employment in the United States: 2019

Figure 9

EMPLOYMENT RATES ACROSS OCCUPATIONAL FIELDS

AGRICULTURE

ACCOMMODATIONS AND

FOOD SERVICES

CONSTRUCTION

EDUCATION

ENTERTAINMENT

EXTRACTION

(e.g. oil and gas)

FINANCE

GOVERNMENT, MILITARY,

ADMINISTRATION

INFORMATION SERVICES

MANUFACTURING

MEDICAL

PROFESSIONAL SERVICES

RETAIL

SERVICE INDUSTRY

TRANSPORTATION

UTILITIES

WHOLESALE

1.1%

4.6%

0.6%

1.0%

7.8%

5.4%

6.5%

2.2%

1.6%

1.1%

1.6%

12.4%

15.7%

13.8%

11.2%

12.1%

10.0%

8.8%

8.5%

4.1%

4.1%

6.5%

4.9%

3.1%

3.2%

9.5%

1.6%

3.3%

7.1%

8.9%

1.5%

1.2%

8.2%

6.9%

20%10%5% 15%0

16

Deaf People and Employment in the United States: 2019

HEARING

PEOPLE

DEAF

PEOPLE

Figure 10

EARNINGS BY AGE

AGE

0

$60,000

$40,000

$20,000

30 40 50 60

EARNINGS

Although the ages of 25-64 are considered

“working age,” according to common federal

guidelines, employment rates and earnings

change across the lifespan. For deaf and hearing

people alike, earnings increase as people age

(Figure 10). However, there are some differences

in these earnings gains across time for deaf and

hearing people. First, the median earnings for deaf

people demonstrates much more within-group

variation, which is expected to the smaller sample

size. Although, this data point could also indicate

that there is greater income instability for deaf

people in the United States. Second, earnings

gains over time are signicantly stronger for

hearing people

than for deaf people. Earnings are more

strongly correlated with age for hearing people,

(Spearman’s ρ=0.14), than for deaf people,

at (Spearman’s ρ=0.11). This may indicate that

earnings gains related to age and experience are

weaker for deaf people than for hearing people.

It is a possibility that deaf people have fewer

opportunities for promotion and raises over

time, as the research literature would have us

expect. Another possibility is that a cohort effect

is at play, where younger deaf people have more

advantages than older deaf people and are more

competitive in the workforce.

EMPLOYMENT ACROSS THE LIFESPAN

17

Deaf People and Employment in the United States: 2019

AGE

0

25

50

75

100

30 40 50 60

PERCENTAGE EMPLOYED

Figure 11

EMPLOYMENT BY AGE

HEARING

PEOPLE

DEAF

PEOPLE

18

Deaf People and Employment in the United States: 2019

The data for this project were taken from the

Public Use Microdata Sample (PUMS) of the

2017 American Community Survey (ACS), con-

ducted by the United States census. The PUMS

provides a condential subset of the ACS for

the public to analyze and these data were made

available in September of 2018. The ACS is a

legally mandated questionnaire sent to a random

sample of addresses of homes and group

quarters in the US. The questionnaire includes

questions about both housing units and their

individual occupants. The PUMS dataset includes

survey weights, designed to produce estimates

that generalize to U.S. people, along with a set

of replicate weights used to estimate sampling

error. These weights account for the complex

probability sample design as well as for non-

response. Although the census bureau goes to

great lengths to minimize non-sampling error,

it is impossible to fully eliminate, so estimates

should be interpreted with care. More information

can be found at http://www.census.gov/

programs-surveys/acs/about.html.

The sample of interest in these analyses was non-

institutionalized people between the ages of 25

and 64. Recall that the U.S. Census collects data

on functional limitations and not disability or

identity labels. The disability categories used in

the ACS ask respondents to report if they have

any serious difculty in the following areas: a)

hearing, b) vision, c) cognitive (remembering, con-

centrating, and making decisions), d) ambulatory

(walking or climbing stairs), e) self-care (bathing

or dressing), and f) independent living (doing

errands alone such as visiting a doctor’s ofce or

shopping). Survey respondents who stated that

they were deaf, or had serious difculty hearing,

were used to represent the deaf population in

these analyses. More than 37,700 deaf people

were in the nal sample. The comparison group

was those who did not report having any hearing

difculties, what we label as hearing people. For

the most part, the data for the group of hearing

people are largely comparable to data for the

general population. But for comparison purposes,

this analysis focuses on people in the general

population that did not report any type of difculty

hearing, which allows for an understanding of

what employment experiences may be unique to

the deaf population, and what may not be.

METHODS

Median annual earnings were calculated from

full-time employed people, dened as those who

worked at least 50 weeks in the past 12 months,

at least 35 hours per week. Data from more than

15,000 deaf people were used to report median

annual earnings. Median annual earnings are

rounded off to the nearest hundred.

Occupational categories from the North American

Industry Classication System (NAICS) was used

to generate the categories for elds of work, with

minor modications, largely following abbrevi-

ations in the PUMS data dictionary. Two new

categories were generated: “management of com-

panies and enterprises,” “professional, scientic,

and technical services,” and “administrative and

support and waste management and remediation

services” were combined under “professional

services” while “nance and insurance” and “real

estate, rental, and leasing” were combined under

“nance.” The NAICS category “Health Care and

Social Assistance” was divided into two new

categories, “Health Care” and “Social Assistance.”

More information about these categories can be

found at census.gov/eos/www/naics.

The descriptive statistics in this report are all

corrected by the person-level survey weights

provided by the census. When numbers are com-

pared to each other in this report, we used a t-test,

with standard errors calculated using provided

survey replicate weights, to determine if difference

in the numbers were due to statistical noise.

These statistical tests are purely descriptive in

nature, and we do not intend to suggest that any

of the associations described are causal in nature.

As such, we did not correct for any other variables

in providing these descriptive statistics.

The R syntax for all the statistical estimates in the

paper can be accessed at https://github.com/

nationalDeafCenter/attainmentAndEmployment.

THIS REPORT MAY BE CITED AS:

Garberoglio, C.L., Palmer, J.L., Cawthon, S., & Sales, A. (2019). Deaf People and Employment in the United States: 2019.

Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, Ofce of Special Education Programs, National Deaf Center on

Postsecondary Outcomes.

NDC

National Deaf Center

on Postsecondary Outcomes