Determinants of Property Prices in

Hong Kong SAR: Implications for Policy

R. Sean Craig and Changchun Hua

WP/11/277

© International Monetary Fund WP/11/277

IMF Working Paper

Asia and Pacific Department

Determinants of Property Prices in Hong Kong SAR: Implications for Policy

Prepared by R. Sean Craig and Changchun Hua

Authorized for distribution by Nigel Chalk

November 2011

Abstract

This paper uses an econometric model of residential property prices in Hong Kong SAR

t

o assess the effectiveness of alternative policies in slowing the increase in property prices.

T

he rapid rise in property prices is well explained by macroconomic fundamentals; real

GDP per capital, real domestic credit, construction costs, land supply, and the real interest

r

ate. Policy can influence the property market though land supply and prudential and tax

p

olicy, with the latter policies taking the form of a stamp duty on property transactions

and a tighter loan-to-value ratio (LTV) on lending. Land supply is the most effective

p

olicy insturment for restraining property price increases but it operates with a significant

l

ag. The LTV and stamp duty dampen speculative activity that drives up property prices.

W

hile these policies can slow the increase in the short run, they should be guided by their

l

ong run objectives of financial stability and counteracting speculation.

JEL Classification Numbers: R21, R31, R38

Keywords: Property price, Co-Integration, Land Supply, Stamp Duty, Loan-to-Value Ratio

Author’s E-Mail Address: [email protected]; [email protected]

This Working Paper should not be reported as representing the views of the IMF.

The views expressed in this Working Paper are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily

represent those of the IMF or IMF policy. Working Papers describe research in progress by the

author(s) and are published to elicit comments and to further debate.

2

Content Page

I. Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 3

II. Policies to Restrain Residential Property Prices in Hong Kong SAR ........................................ 3

III. An Econometric Model of Property Prices in Hong Kong SAR .............................................. 6

IV. Model Estimation Results ......................................................................................................... 8

V. Explaining the Rapid Rise in Property Prices .......................................................................... 11

VI. Conclusions............................................................................................................................. 11

References ..................................................................................................................................... 14

3

I. INTRODUCTION

This paper uses an econometric model of residential property prices in Hong Kong SAR to

assess the effectiveness of alternative policies in curbing pressures on property prices. The

fundamental drivers of the real property price are real GDP per capital, real domestic credit,

construction costs, land supply, and the real interest rate. Policy can influence the property

market through land supply and interest rates but also prudential and tax policy. The latter

include two instruments that the authorities have recently relied on extensively: a stamp duty on

property transactions; and the loan-to-value (LTV) ratio on bank lending. Since these

instruments are adjusted infrequently, we supplement model estimation with an event-study of

their impact on property market transactions as well as price.

A co-integration estimation methodology is used because tests show that property prices and the

macroeconomic fundamentals are co-integrated. This involves a two stage process where we first

estimate the long run co-integrating relationship among these variables and, second, the short run

dynamic relationship using an error correction equation. In the latter equation we can include the

stationary (i.e. not co-integrated) policy variables – the LTV and stamp duty – to assess their

impact. The model performs well statistically in that the recent, rapid rise in property prices is

well explained by highly supportive macroeconomic fundamentals and the “equilibrium” price

derived from the model tracks the actual price relatively closely.

The estimation results show that real GDP per capita has the strongest long run influence on

property prices followed by land supply, which works with a significant lag. The real interest

rate and an index of construction costs have less strong effects while real domestic credit has the

weakest impact. The LTV ratio and stamp duty both have statistically significant effects on price,

although the latter is very small. These effects are temporary and, thus, can slow, but not

fundamentally alter, the rising trend in property prices.

The results suggest that policy should focus on raising land supply to restrain property price

increases over the long run. However, the significant lag with which it has an effect means that

care is needed to avoid exacerbating the property price cycle. The real interest rate also has a

long run influence on price and may rise with a tightening of liquidity conditions related to

stricter macroprudential policies. The LTV and stamp duty dampen speculative activity that

drives up property prices. While these policies can slow the increase in the short run, they should

be guided by their long run objectives of financial stability and counteracting speculation.

II. P

OLICIES TO RESTRAIN RESIDENTIAL PROPERTY PRICES IN HONG KONG SAR

The surge in housing prices since mid-2009 raised concern about a build-up of risks in the

housing sector, leading the authorities to adopt a number of policy measures to contain them.

These measures fall into three categories: (i) prudential measures, particularly reductions in LTV

limits; (ii) anti-property market speculation measures, such as the special stamp duty tax on

transactions; (iii) increases in land supply policy to boost the number of apartments (Figures 1-2).

4

A tightening of macroprudential policies aimed at strengthening financial stability can also help

contain upward pressure on property prices by raising borrowing costs.

The LTV ratio has long been the most actively used prudential tool to limit the buildup of credit

risk in the property sector (Wong et al., 2011). The Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA)

tightened LTV ratio several times over the last few years. At present, properties valued HK$10

million or above are subject to a 50 percent LTV ratio (Figure 1). A cut in the LTV reduces the

amount of credit available to borrowers with a given level of assets for a down payment, slowing

mortgage lending and property purchases. LTV limits are tighter (i.e. lower) in the luxury market

segment but their impact on price should spillover into the mass market segment. Over time, the

effect is likely to erode, however, as borrowers accumulate more assets.

The stamp duty on residential property transactions aims to curb speculative activities in the

property market. The Government introduced a special stamp duty (SSD) in November 2010 on

residential properties resold within 24 months of purchases in addition to an existing stamp duty

(of 4.25 percent). The SSD tax rate is 15 percent for properties resold within six months but

declines in steps the longer a property is held, falling to zero after 24 months. It raises the cost of

buying properties and then reselling them quickly (a practice called “flipping”), thus encouraging

buyers to hold property for longer. A hike in SSD will reduce transaction volumes, although with

an ambiguous effect on price. The tax-incidence impact could initially push up sales price

although this effect should quickly fade as buyers hold property for longer to avoid the duty.

The impact of the LTV ratio and stamp duty on the property market is assessed first with an

event study methodology, which is practical as they are adjusted infrequently. This facilitates

interpretation of the results from model estimation below. The event study looks at how property

transaction volume and prices change around the date when these policy tools are adjusted.

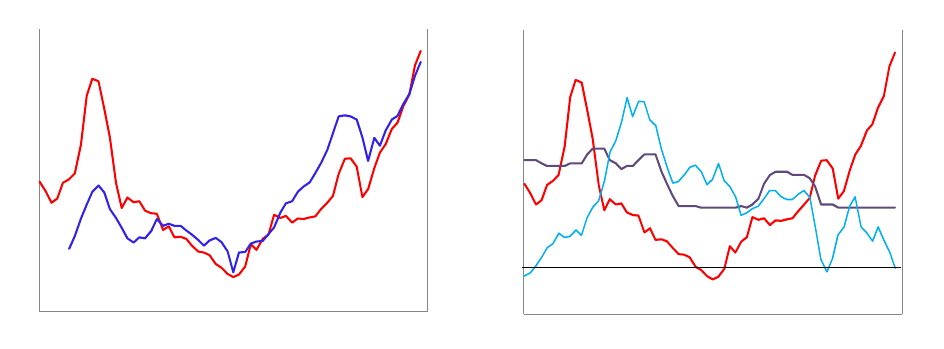

Figure 3(a) shows the average change in these two variables around four dates when reductions

Figure 1: Loan-to-Value and stamp duty rate

Note: The Special Stamp Duty imposed in Nov 2010 is added to

the regular stamp duty rate.

Data sources: HKMA, HK Government, and staff calculations

0

4

8

12

16

20

0.0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.7

0.8

0.9

1.0

1995 1997 1999 2001 2003 2005 2007 2009 2011

Loan-to-value ratio limit (left scale)

Highest marginal stamp duty rate

%Unit

Figure 2: Residential property price and land supply

Data sources: CEIC and staff calculations

0

100

200

300

400

500

600

700

800

900

1,000

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

180

1995 1997 1999 2001 2003 2005 2007 2009

Government land auction (right scale)

Residential property price index

1000 sq m

1999=100

5

in the LTV limits and/or increases in the stamp duty took place (October 2009, April 2010,

August 2010, and November 2010). The study does not look at the LTV and stamp duty

separately since recent changes have often occurred on the same dates. Figure 3(b) shows price

and transactions for just November 2010, which is when the 15 percent SSD was introduced and

the LTV was cut by 10 percentage points. The figures show that residential property price

growth slowed in the month after the policy adjustments but then rebounded. Similarly,

transaction volumes fell for two months after the policy adjustments but then rebounded. In sum,

the event study suggests a short-lived impact on price from these measures.

Land supply is the third main policy variable that the Hong Kong authorities are relying on to

restrain property price increases. Figure 2 suggests the changes in supply affect property price

with a substantial lag. Prices fell early last decade after relatively large increase in supply and

then rose rapidly in 2009-10 after the global financial crisis curbed new supply. The lag reflects

the slow transmission from an increase in land supply to a rise in the number of apartments,

which peaks several years after an increase in supply (Figure 4). Land and apartment supply

produce similar results when used as a variable in the econometric model, but land supply is used

in the final specification because it drives apartment supply and is more directly influenced by

policy given the large share of land that is public. The government recently adopted a more

proactive land policy in which it auctions land on a regular schedule. This older system where

bids from developers trigger release of land from a land bank remains in place but the new policy

reduces the risk that of sharp fall off in new supply, as when developers cut bids in 2008.

Figure 3a: Property price changes and transaction

volume around LTV decreases and / or stamp

duty increases

Note: Vertical line corresponds to four policy change dates.

Data sources: CEIC, and staff calculations

-4.0

-3.0

-2.0

-1.0

0.0

1.0

2.0

3.0

4.0

5.0

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

t-6 t-5 t-4 t-3 t-2 t-1 t t+1 t+2 t+3 t+4 t+5 t+6

Avg. property sales transaction

Avg. property price m/m change (right scale)

HKD bn %

Figure 3b: Property price changes and transaction

volume around Nov. 2010 policy changes

Note: Vertical line corresponds to November 2010.

Data sources: CEIC, and staff calculations

-4.0

-3.0

-2.0

-1.0

0.0

1.0

2.0

3.0

4.0

5.0

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

t-6 t-5 t-4 t-3 t-2 t-1 t t+1 t+2 t+3 t+4 t+5 t+6

Property sales transaction

Property price m/m change (right scale)

HKD bn

November 2010

%

6

III. AN ECONOMETRIC MODEL OF PROPERTY PRICES IN HONG KONG SAR

To assess the impact of alternative policies, we need to control for the fundamental

macroeconomic variables driving property prices using an econometric model. To this end, we

develop a reduced-form model of property prices in which these variables come from underlying

supply and demand models of the property market. The model specification builds on the

literature on Hong Kong SAR’s residential property market (particularly, Ahuja and Porter, 2010;

Chan, Peng, and Fan, 2005; Leung, Chow, and Han, 2008; Lai and Wang, 1999; and Peng, 2002).

These studies either focus on testing for a property price bubble rather than the effect of policies,

or use cross country panel estimation to test for effectiveness, which reduces its applicability to

the Hong Kong situation. The current paper differs from these earlier studies in that it focus

solely on the effectiveness of policies in Hong Kong SAR, and does so using a co integration

framework, which distinguishes long run and short run effects.

Figure 4: Land supply and residential apartment

supply

Data source: CEIC

Figure 5: Residential property price and

building construction cost

Note: GDP per capita is seasonally adjusted.

Data sources: CEIC and staff estimation

Property prices and the fundamental driving variables should be co-integrated – and tests

confirm this – making a co-integration estimation methodology necessary. With only one co-

integrating vector identified in testing, we can use the Engle-Granger two step approach. This is

a convenient simplification of Vector Error Correction Model that is possible in the special case

of a unique co-integrating vector. This approach involves estimating, first, the long run co-

integration relationship among fundamental variables; and, second, an error correction model of

the short run influence of these variables on price, where the error correction term – representing

the deviation of the actual price from the long run equilibrium price – is the residual from the co-

integration equation. A key advantage of this approach is that we can assess the impact of

stationary (i.e. not co-integrated) policy variables – the LTV and stamp duty – on price by adding

them to the error correction equation. This allows us to assess the effect of policy variables that

are co-integrated with price and those that are not within the same statistical framework.

0

200

400

600

800

1,000

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

1995 1998 2001 2004 2007 2010

Thousands

Completed residential flat (left scale)

Government land auction

1,000 sq m1,000 units

600

700

800

900

1000

1100

1200

1300

1400

1500

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

180

200

1995 1997 1999 2001 2003 2005 2007 2009 2011

Residential property price index (left scale)

Building work tender price index

1999=100

1970=100

7

The supply side variables derived from a model of property market supply are land supply

(square meters sold at land auctions) and building costs (an index of material and labor costs):

holding other factors constant, land supply (h) is expected to be negatively correlated with

residential property price; while building costs (c) should be positively correlated with the

residential property price (Figure 5) as they put pressure on property developers’ margin which,

in turn, tends to push up price.

Housing demand is affected by GDP per capita, the interest rate (the prime rate), and bank credit.

Higher household income (y) and lower interest rates (r) tend to improve housing affordability,

raising housing demand. Residential property price should be positively correlated with GDP per

capita (Figure 6) and negatively correlated with the interest rate (Figure 7). Finally, domestic

credit (l) is included rather than mortgage credit as it outperforms the latter in model estimation.

This probably reflects the fact that property purchases in Hong Kong SAR have a large cash

component and are less dependent on mortgage credit availability. In this environment, the

interest rate may be a better explanatory variable. Domestic credit works better than mortgage

credit in the model, possibly because it also captures broader liquidity conditions in the financial

system (Figure 8).

Figure 6: Residential property price and GDP per

capita

Note: GDP per capita is seasonally adjusted.

Data source: CEIC and staff estimation

Figure 7: Residential property price and

interest rates (nominal and real)

Data sources: CEIC and staff estimation

40

45

50

55

60

65

70

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

180

200

1995 1997 1999 2001 2003 2005 2007 2009 2011

Residential property price (left scale)

GDP per capita (seasonal adjusted)

1999=100

HK$ 1,000

-4

0

4

8

12

16

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

180

200

1995 1997 1999 2001 2003 2005 2007 2009 2011

Residential property price index (left scale)

Best lending rate

1999=100 % p.a.

Real interest rate

8

The co-integrating equation is specified as a linear relationship between the residential property

price and the above variables:

*

01 2 3 4 5tttmttt

pchyrl

(1)

To allow for the long lag between when land is supplied and completed flats come onto the

market, h enters the equation with m-quarter lag determined by empirical tests. The variable p* is

the “equilibrium” property price as determined by long run fundamentals. Statistical tests find a

single long run co-integrating relationship among

t

p

,

t

c ,

tm

h

,

t

y

,

t

r and

t

l . This makes it

possible to include these variables in an associated error correction model of short-term price

dynamics to which can be added the two stationary policy variables (which are not co-integrated

with the other variable), the loan-to-value ratio (LTV) and stamp duty tax (SDT):

0112 3451 2ttttmttttt

pchyrlLTVSDT

(2)

The error-correction term in this model,

1

*

11

t

tt

p

p

is the error term from equation (1)

lagged one period. This term is the deviation of the actual residential property price from the

long-run equilibrium price estimated in equation (1). The parameter on this term, λ, represents

the speed of adjustment of the property price back to its long run equilibrium value.

IV. MODEL ESTIMATION RESULTS

Equations (1) and (2) are estimated using quarterly data from 1997 to 2011 Q2, with nominal

variables deflated by the CPI for both the overall market and the luxury market. Unit root tests

for all the variables used in the co-integration equation all have one unit root (Annex).

Johansen’s system co-integration test finds one long-run co-integrating relationship exists for

these variables.

Figure 8: Residential property price and

domestic credit

Data source: CEIC

120

0

160

0

200

0

240

0

280

0

320

0

360

0

400

0

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

180

200

1995 1997 1999 2001 2003 2005 2007 2009 2011

Residential property price index (left scale)

Domestic credit

1999=100 HK$ bn

9

Table 1: Estimation Results of Co-Integration Model for Residential Property Prices

Dependent variable:

Log(real property price)

Overall Market

Beta (t-stat)

Luxury market

Beta (t-stat)

Constant

5.342***

(3.085)

6.872***

(4.055)

Real interest rate

-0.016**

(-2.331)

-0.027***

(-3.627)

Log( real GDP per capita)

1.492***

(6.510)

2.370***

(10.916)

Log(real domestic credit)

0.245**

(2.660)

-0.132

(-1.316)

Log(real construction cost index)

0.479***

(7.336)

0.262***

(3.976)

Log (Land supply) with 5-quarter lag

-0.800***

(-7.336)

-0.828***

(-8.142)

Adjusted-R

2

0.966 0.980

DW-Statistic

1.577 1.538

Obs.

56 (1997Q3-2011Q2) 56 (1997Q3-2011Q2)

Notes: (1) Relationships are estimated using dynamic least squares (DOLS) method with two lags heteroskedasticity-

autocorrelation consistent (HAC) standard errors.

(2) *** 1% significance, ** 5% significance, * 10% significance.

Estimation results for the co-integration equation (Table 1) are shown for the overall and

luxury market segments. Unit root tests for the error terms of these two co-integration equations

show that they have no unit root. All variables have the correct signs and are statistically

significant at the 1% or 5% level, except for domestic credit in the luxury market equation. The

variables are in natural logs and, thus, are elasticities that can be directly compared, except the

real interest rate. Results for the overall market imply: (i) a one percent rise in real GDP per

capita raise real residential property price by around 1.5 percent; (ii) a one percent rise in real

domestic credit increases real residential property price by 0.2 percent (but the effect in the

luxury market is zero, reflecting less reliance on credit in this segment); (iii) a one percent

increase in real building cost push up real residential property price by around 0.5 percent; (iv) a

one percent increase in land supply drives real residential property prices down by 0.8 percent;

and (v) a one percentage point hike in real interest rate reduces real residential property price by

around 1.5 percent.

Estimation results for the error correction equation (Table 2) are shown for the overall and

luxury market segments. Dummy variables were added for September 2008, when Lehmann

Brothers failed, and the SARS episode in Hong Kong SAR. The results show that a

one percentage point increase in the real GDP growth rate raises real property price inflation by

2.3 percentage points; but that the real interest rate, land supply, building costs and real domestic

credit do not have statistically significant short run effects on property prices. The latter may

reflect the long lags and relatively indirect transmission channels (i.e. through the mortgage

market) for these variables that limit their short run effects.

10

Both the LTV and the stamp duty have statistically significant effects on real property prices but

the latter is so small as to be immaterial. The LTV does slow the property price inflation with a

10 percentage point cut in the LTV temporarily slowing inflation by 6.4 percentage points.

1

The

small effect of the stamp duty may reflect its ambiguous effect on price. A tax-incidence effect

could initially push up property prices while the fall in transactions would tend to depress price.

Both effects should fade quickly as buyers hold property for longer to avoid the duty.

Nevertheless, the tax can still achieve in its objective of driving speculators out of the market by

encouraging buyers to hold their properties for a longer periods.

2

Table 2: Estimation Results of Error Correction Model for Residential Property Prices

Dependent variable:

∆ Log(real property price)

Overall Market

Beta (t-stat)

Luxury market

Beta (t-stat)

Constant

-0.427***

(-3.780)

-0.446***

(-3.063)

Error correction term (1-quarter lag)

-0.662***

(-3.359)

-0.550*

(-1.877)

∆ Real interest rate

-0.007

(-1.322)

-0.004

(-0.665)

∆ Log( real GDP per capita)

2.267***

(4.291)

2.615***

(4.133)

∆ Log(real domestic credit)

0.143

(0.736)

0.201

(0.944)

∆ Log(real construction cost index)

0.256*

(2.009)

0.215

(1.422)

∆ Log (Land supply) with 5-quarter lag

-0.342

(-0.811)

-0.364

(-0.817)

LTV

0.641***

(3.673)

0.678***

(3.082)

SDT

0.006***

(3.312)

0.005**

(2.206)

D03

-0.063*

(-1.884)

-0.062*

(-1.956)

D08

0.069**

(2.427)

0.056*

(1.887)

Adjusted-R

2

0.432 0.407

AIC

-2.846 -2.758

Obs.

55 (1997Q4-2011Q2) 55 (1997Q4-2011Q2)

Notes: (1) Relationships are estimated using ordinary least squares (OLS) method with heteroskedasticity-autocorrelation

consistent (HAC) standard errors.

(2) Stamp duty (SDT) appears not statistically significant on the sample of (1997Q4-2010Q4) for both overall and luxury

residential property markets.

(3) *** 1% significance, ** 5% significance, * 10% significance.

1

Multiples lags for the LTV and stamp duty do not significantly alter the estimation results in Table 2.

2

Evidence for this interpretation comes from the fact that the SSD did sharply reduce residential property confirmor

transactions. These are when a buyer re-sells the flat to a sub-purchaser before the legal completion of the original

sale. It serves as an indicator of speculative activity in the market. Residential confirmor transaction declined by

around 80% from 229 cases in November 2010 to 49 cases in May 2011.

11

V. EXPLAINING THE RAPID RISE IN PROPERTY PRICES

The model finds that the recent rapid rise in property prices is well explained by highly favorable

macroeconomic fundamentals. A deviation of the actual price from the long run equilibrium

price that is statistically “large”—two standard deviations—can be interpreted as evidence of a

bubble. However, Figure 9 shows that the actual price stays within the two standard deviation

band.

3

Moreover, this gap between actual and equilibrium prices is closed quickly, with the

error-correction term coefficient correcting around two-third of the deviation between the actual

and long-run equilibrium property prices within one quarter. Overall, the model suggests that the

rapid rise in property prices happened because fundamental variables turned highly supportive

with negative real interest rates, a limited supply of new apartment, and rapid real GDP and

domestic credit growth. This suggests that policy should focus on restraining these fundamental

drivers of property prices.

Figure 9a: Actual and forecast real

residential property prices

Source: Staff estimations

Figure 9b: Actual and equilibrium

residential property prices: luxury market

Source: Staff estimations

VI. C

ONCLUSIONS

The Real GDP per capita has the strongest long run influences on property prices followed by

land supply, which works with a significant lag, the real interest rate, real construction costs, and

real domestic credit, which has the weakest impact. This suggests that policy should focus on

raising land supply to restrain property price increases over the long run. However, the

significant lag with which it has an effect means that care is needed to avoid exacerbating the

3

This is the case when an ex-post forecast is used to assess the robustness of the model (not shown): the model is

estimated through 2010 Q2 and the model forecast is compared to the actual over 2010 Q2 to 2011 Q2. The actual

price remains within the forecast two-standard deviation band over this horizon consistent with parameter stability.

3.8

4.0

4.2

4.4

4.6

4.8

5.0

5.2

3.8

4.0

4.2

4.4

4.6

4.8

5.0

5.2

1997Q2 1999Q2 2001Q2 2003Q2 2005Q2 2007Q2 2009Q2 2011Q2

Actual real residential property price (log)

Equilibrium real residential property price (log)

2 standard deviation band

4.0

4.2

4.4

4.6

4.8

5.0

5.2

5.4

4.0

4.2

4.4

4.6

4.8

5.0

5.2

5.4

1997Q2 1999Q2 2001Q2 2003Q2 2005Q2 2007Q2 2009Q2 2011Q2

Actual real residential property price (log)

Equilibrium real residential property price (log)

2 standard deviation band

12

property price cycle. The real interest rate also has a long run influence on price and may rise

with a tightening of liquidity conditions resulting from more restrictive macroprudential policies.

The LTV ratio and stamp duty both have statistically significant effects on price, although the

latter is very small. These effects are temporary, and, thus, can slow, but not fundamentally alter,

the rising trend in property prices. The LTV and stamp duty dampen speculative activity that

drives up property prices. While these policies can slow the increase in the short run, they should

be guided by their long run objectives of financial stability and counteracting speculation,

respectively. Finally, the analysis suggests that the recent, rapid rise in property prices is well

explained by highly supportive macroeconomic fundamentals with the “equilibrium” price

derived from the model tracking the actual price quite closely.

13

Annex Table 1: Descriptive Statistics

Real

property

price index

Real interest

rate

(% pa)

Real GDP

per capita

(HK$1,000)

Real tender

price index

A

ccumulative

land supply

(1000 sq m)

Real

domestic

credit

(HK$ bn)

Mean

99.586 5.575 49.787 848.231 2154.989 1972.386

Median

94.512 5.665 47.456 808.217 2417.630 1869.152

Maximum

157.631 14.366 65.787 1286.750 3026.203 3295.911

Minimum

59.300 -0.795 37.727 667.729 143.853 1509.486

Std. Dev.

25.139 3.779 7.959 148.995 721.776 403.767

Skewness

0.589 0.467 0.345 0.947 -1.332 1.877

Kurtosis

2.665 2.726 1.717 3.104 4.087 6.156

Jarque-Bera

4.125 2.609 5.399 9.893 22.771 62.129

Observations

66 66 61 66 66 62

Note: Nominal data are deflated by CPI at the quarter.

Data sources: CEIC and Hong Kong Building Department

Annex Table 2: Unit root Test Result (ADF-test)

(c, t, L) Level First difference I(k)

Log(real property price index)

(c, t, 1) -0.675 -5.664*** I(1)

Real interest rate

(c, t, 1) -2.247 -5.425*** I(1)

Log(real GDP per capita)

(c, t, 1) -1.792 -5.826*** I(1)

Log(building work tender price

index)

(c, t, 1) -1.698 -6.044*** I(1)

Log(land supply)

(0, 0, 3) 0.953 -31.673*** I(1)

Log(real domestic credit)

(0, 0, 5) 1.081 -2. 740*** I(1)

Notes: (1) Null hypothesis: variable has a unit root. Lags in the test are automatically selected.

(2) *** 1% significance

14

REFERENCES

Ahuja, A., and N. Porter, 2010, “Are House Prices Rising Too Fast in Hong Kong SAR?” IMF

Working Paper WP/10/273, (December).

Chan, N., W. Peng, and K. Fan, 2005, “A Graphical Framework for Monitoring the Property

Market in Hong Kong,” HKMA Quarterly Bulletin, (March).

Crowe, C., G. Dell'Ariccia, D. Igan, and P. Rabanal, 2011, “Policies for Macrofinancial Stability:

Options to Deal with Real-Estate Booms,” IMF Staff Discussion Note SDN/11/02,

(February).

Lai, N., and K. Wang, 1999, “Land-Supply Restrictions, Developer Strategies and Housing

Policies: The Case in Hong Kong,” International Real Estate Review, 2:1, pp.143-59.

Lung, F., K. Chow, and G. Han, 2008, “Long-Term and Short-Term Determinants of Property

Prices in Hong Kong,” HKMA Working Paper 15/2008, (October).

Peng, W., 2002, “What Drives Property Prices in Hong Kong?” HKMA Quarterly Bulletin,

(August).

Wong, E., T. Fong, K.-F. Li, and H. Choi, 2011, “Loan-to-Value Ratio as A Macro-prudential

Tool: Hong Kong’s Experience and Cross-Country Evidence,” HKMA Working Paper

01/2011, (February).