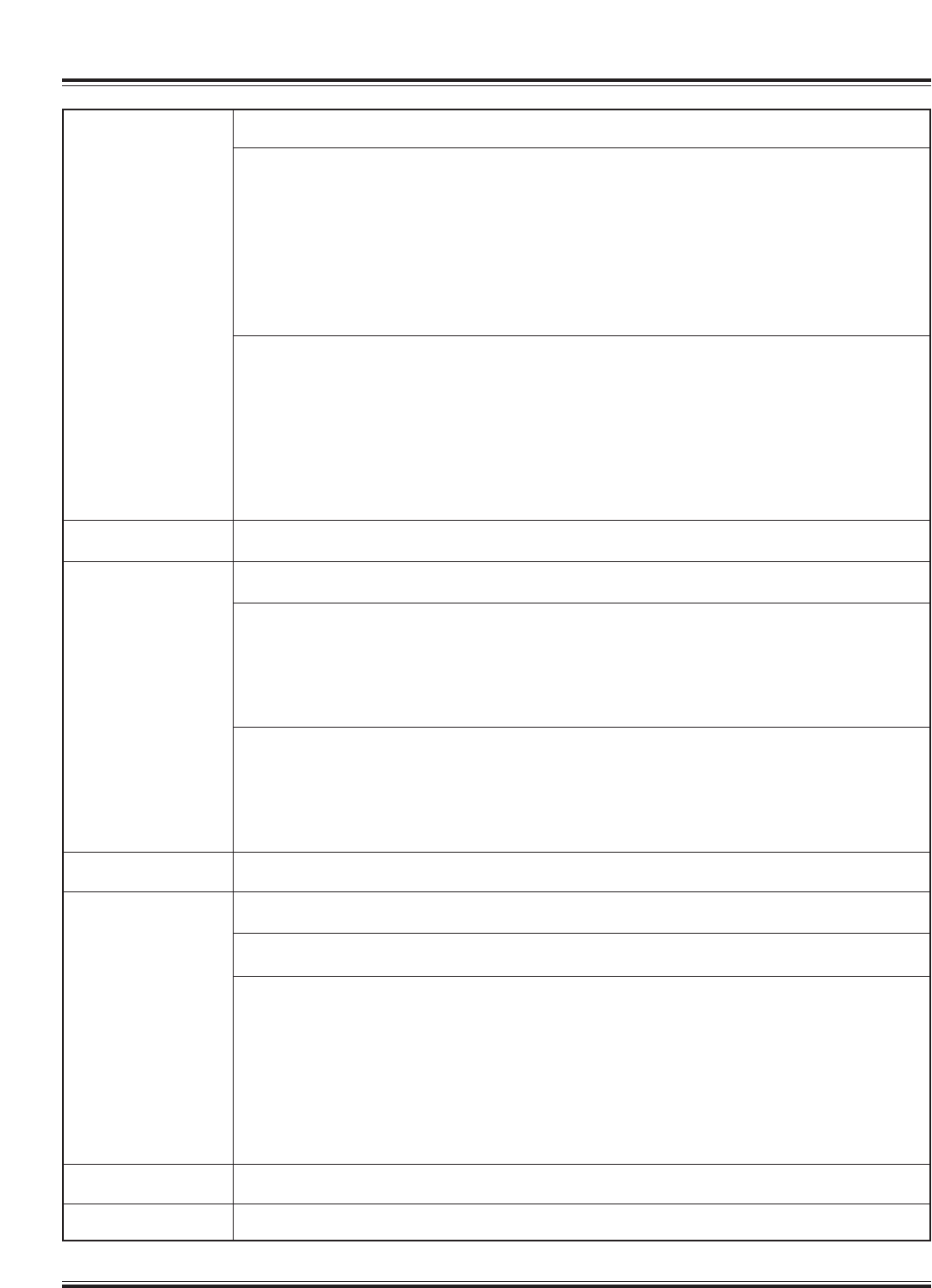

Table of Contents

Volume 34, No. 4, Spring 2009

Asset Protection and Tenancy by the Entirety . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 210

Fred Franke

A thorough discussion of tenancy by the entirety and its asset protection attributes.

A Letter About Investing to a New Foundation Trustee,

with Some Focus on Socially Responsible Investing . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 234

Joel C. Dobris

Sage investment advice provided to private foundation board members.

Business Succession Planning, Profits Interests and § 2701 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 243

Richard B. Robinson

An analysis of use a partnership profits interest in estate planning.

McCord to Holman—Five Years of Value Judgments . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 254

Cynthia A. Duncan, John R. Jones, Jr., and James D. Spratt, Jr.

A detailed examination of expert determination of lack control and lack of marketability

discounts in litigation.

Family Offices: Securities and Commodities Law Issues . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 284

Audrey C. Talley

Securities and commodities law issues affecting the design and implementation of a

family office.

Comparison of the Twelve Domestic Asset Protection Statutes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 293

David G. Shaftel

An up-to-date chart on domestic asset protection trust legislation.

THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF TRUST AND ESTATE COUNSEL

3415 S. Sepulveda Boulevard, Suite 330 • Los Angeles, California 90034 • (310) 398-1888 • Fax: (310) 572-7280 • www.actec.org

Marc A. Chorney, Editor / Charles A. Redd, Associate Editor / Turney Berry, Assistant Editor

34 ACTEC Journal 209 (2009)

JOURNAL

®

34 ACTEC Journal 210 (2009)

Editors’ Synopsis: This article first discusses the

history and development of tenancy by the entirety, a

form of concurrent ownership of property by spouses.

The article then considers state variations of that form

of ownership and treatment with respect to bankruptcy

law and federal tax liens. The article concludes with

recommendations for planning with tenancies by the

entirety. The appendix to the article provides a useful

state by state summary of asset protection aspects of

the form of ownership.

I. The Historic Roots and Development of

Tenancy by the Entirety

And therefore, if an estate in fee be

given to a man and his wife, they are

neither properly joint-tenants, nor

tenants in common: for husband and

wife are considered one person in law,

they cannot take the estate by moi-

eties, but both are seized of the entire-

ty, per tout et non per my; the conse-

quences of which is, that neither the

husband nor the wife can dispose of

any part without the assent of the

other, but the whole must remain to

the survivor.

1

Under Blackstone’s classic formulation, tenancy

by the entirety ownership did not track other forms of

concurrent ownership like joint tenancies or tenancies

in common. Rather, entirety property was ownership

without equal parts or shares (“moieties”). One might

assume that the absence of divisible shares meant that

neither husband nor wife had a separate, alienable

share. One might also assume that if “the whole must

remain to the survivor,” then the alienation of a sepa-

rate interest would defeat the right of each spouse to

the survivorship of the whole.

The classic formulation of the tenancy is rooted

in the theory that husband and wife constitute an

indivisible unit: “An estate by the entireties is an

almost metaphysical concept which developed at the

common law from the Biblical declaration that a man

and his wife are one.”

2

In practice, however, this

metaphysical oneness collided with the restrictions

placed on women, particularly married women, by

the common law:

A species of common-law concurrent

ownership, tenancy by the entireties

developed as part of the English feu-

dal system of land tenures. The exi-

gencies of feudalism demanded that

the functions of ownership be vested

in males presumably capable of bear-

ing arms in war. Women were lightly

regarded legally, especially married

women—whose very identifies, in

most respects, were considered

merged and lost in the personalities of

their husbands. For purposes of prop-

erty and contract, the married woman

was under a complete legal blackout

termed coverture. Man and wife were

one and the one was male.

3

The husband’s dominance at common law was exten-

sive. He, and he alone, had sweeping powers over the

entireties property. He exclusively:

* Copyright 2009 by Fred Franke. All rights reserved. The

author wishes to acknowledge his daughter, Mimi Murray Digby

Franke, Esq., for her generous editorial assistance.

1

WILLIAM BLACKSTONE,COMMENTARIES ON THE LAWS OF

ENGLAND 182 (9th ed. 1783), quoted in Peter M. Carrozzo, Tenan-

cies in Antiquity: A Transformation of Concurrent Ownership for

Modern Relationships, 85 M

ARQ. L. REV. 423, 437 (Winter 2001).

The 9th edition, published posthumously, contained the first discus-

sion of a husband and wife owning an estate by its entirety by

Blackstone. Its editor justified the addition: “The editor judges it

indispensible to preserve the author’s text intire. The alterations

which will be found therein, since the publication of the last edition,

were made by the author himself, as may appear from a corrected

copy in his own handwriting.” Id. at 437 n.154. In his article, Mr.

Carrozzo traces the tenancy by the entirety to as early as the thir-

teenth century and characterizes Blackstone’s description of entities

as “the first modern pronouncement.” Id. at 435-37. For another

description of the evolution of the tenancy by the entirety, see also

John V. Orth, Tenancy by the Entirety: The Strange Career of the

Common-Law Marital Estate, 1997 B.Y.U. L. R

EV. 35 (1997).

2

United States v. Gurley, 415 F.2d 144, 149 (5th Cir. 1969)

(interpreting Florida law).

3

Oval A. Phipps, Tenancy by Entireties, 25 TEMP. L. Q. 24,

24 (1951) (emphasis added).

Asset Protection and Tenancy by the Entirety

by Fred Franke

Annapolis, Maryland*

© 2009 The American College of Trust and Estate Counsel. All Rights Reserved.

34 ACTEC Journal 211 (2009)

(1) had the privilege and power to

occupy the principal and to consume

the income of the entire asset; (2) had

power to manage, control, and exter-

nally dispose of possession and of

income during the marriage; (3) had

the benefit alone of all the assets for the

use as a basis of credit, his possessory

and his contingent survivorship inter-

ests being subject to attachment for his

debts while not for those of the wife;

(4) was alone entitled to represent the

asset or any part thereof in litigation.

4

The husband’s control over the property was a con-

trol over its economic value during his lifetime. This

power did not extend, however, to alienating the sur-

vivorship interest. The tenancy by the entireties was

inseparable from the married unit even though it was

dominated by the husband during his lifetime. This sit-

uation generally continued until the middle of the nine-

teenth century when the women’s rights movement

gained hold.

5

As a consequence, Married Women’s

Property Acts were enacted by the various States.

Married Women’s Property Acts abrogated the

dominance of a husband over his wife’s property, thus

reversing the common law and bringing parity of

property rights to both spouses. These statutes forced

entireties tenancy to be re-examined: “The question

then necessarily arose whether the husband’s powers

and the wife’s disabilities, now abrogated, had been

incidents of the co-tenancy status or merely attributes

of the marital status.”

6

If the dominance/disability matrix was an essential

element of the tenancy, then the various Married

Women’s Property Acts may be seen as being incompat-

ible with, and therefore sweeping away, the tenancy

itself. “This view of the effect of the Married Women’s

Property Act—as abrogating entireties altogether—has

been expressly followed in at least nine states: Alabama,

Colorado, Illinois, Iowa, Maine, Minnesota, New Hamp-

shire, South Carolina, and Wisconsin.”

7

Aside from the position that these acts effectively

abolished tenancy by the entirety, two other general

responses to the Married Women’s Property Acts arose:

(1) to reinterpret the tenancy without the husband’s

dominance and the wife’s disability; or (2) to deny that

the new acts had any impact on the old form of the ten-

ancy. Most states reinterpreted the tenancy by either

prohibiting control or alienation of the property by one

spouse through unilateral action or by giving each

spouse separate rights to control or alienate specific

attributes of the property. The few jurisdictions that

initially took the position that the Married Women’s

Property Acts did not impact the ancient attributes of

tenancy by the entirety have now fallen into line with

those states adopting the tenancy to reflect the equal

rights of married women to exercise property rights.

8

It remains to be seen how entireties will develop in

response to domestic partnership legislation and/or

developing case law recognizing same-sex civil

unions. Entireties requires, of course, marriage as the

“fifth unity” of the tenancy:

[C]ommon law requires five ‘unities’ to

be present: marriage—the joint owners

must be married to each other; title—the

owners must both have title to the prop-

erty; time—they both must have

received title from the same con-

veyance; interest—they must have an

equal interest in the whole property; and

control or possession—they both must

have the right to use the entire property.

9

4

Id. at 25. Although this male control was sweeping, “Eng-

lish equity courts early developed an institution of separate proper-

ty for married women, which somewhat alleviated in specific

instances the harsh results of the common law dominance by the

husband—‘admitting the doctrine that a married woman is capable

of taking real and personally estate to her own separate and exclu-

sive use, and that she has also an incidental power to dispose of it.’”

Id. at 26 quoting J

OSEPH STORY,EQUITY JURISPRUDENCE §§ 1378,

1402 (3d. ed. 1843).

5

See Carrozzo, supra note 2, at 439-40. The Seneca Falls

Declaration, for example, was published in 1848.

6

Phipps, supra note 4, at 28.

7

Id. at 29. Interestingly, England abolished tenancy by the

entirety in 1925 by the Laws of Property Act in 1925. R

ICHARD R.

POWELL,POWELL ON REAL PROPERTY, 52-54 (Michael A. Wolf, ed.

2008). A limited form of entireties tenancy was re-established for

“homestead property” by statute in Illinois after the initial aboli-

tion. See Appendix.

8

Massachusetts, for example, followed the rule that the

“husband was the one” for lifetime control of the entireties proper-

ty until reversed by statute in 1980. See D’Ercole v. D’Ercole, 407

F.Supp. 1377, 1382 (D. Mass. 1976). (“As was conceded [in an

earlier case], the common law concept of tenancy by the entirety is

male oriented. It is true that the only Massachusetts tenancy tai-

lored exclusively for married persons appears to be balanced in

favor of males.”). See also Janet D. Ritsko, Lien Times in Massa-

chusetts: Tenancy by the Entirety after Cor

accio v. Lowell Five

Cents Savings Bank, 30 NEW ENG. L. REV. 85 (1995) for a histori-

cal prospective on the late-developing acknowledgement of equal

property rights for women in Massachusetts. Compare the Com-

ment in the Appendix regarding a similar late statutory reversal of

the male domination of entireties in Michigan.

9

United States v. One Single Family Residence With Out

Buildings Located at 15621 S.W. 209th Ave., Miami, Fla., 894 F.2d

1511, 1514 (11th Cir. 1990) (interpreting Florida law).

34 ACTEC Journal 212 (2009)

Under Vermont’s civil union statute, parties to a

civil union are able “to hold real and personal property

as tenants by the entirety (parties to a civil union meet

the common law unity of person qualification for the

purposes of a tenancy by the entirety).”

10

The New Jer-

sey Tax Court recently held, however, that a valid Ver-

mont civil union did not qualify a New Jersey same-

sex couple to hold New Jersey property by the

entireties.

11

How, or whether, the various states will

accommodate entireties to the changing concepts of

domestic relationships is uncertain. The early

response appears to have similarities with the accom-

modation of the Married Woman’s Property Acts and

entireties a century and one-half ago.

12

II. State Variations

13

Those states reinterpreting tenancy by the entirety

to accommodate the Married Women’s Property Acts

follow one of two basic patterns: (1) re-establishing

the “oneness” of the tenancy so that neither spouse can

act unilaterally; or (2) giving parity to the wife so that

she also can alienate part of the tenancy during her

lifetime. The survivorship element is generally main-

tained, even in the latter model. From an asset protec-

tion viewpoint, these states may be characterized as

either “full bar” jurisdictions or “modified bar” juris-

dictions. In full bar jurisdictions, a creditor of one

spouse does not acquire an attachable interest in the

entireties property. Conversely, in a modified bar

jurisdiction, a creditor of one spouse enjoys some

rights in the entireties property, but those rights must

accommodate the non-debtor spouse’s interest.

Most states retaining the tenancy are full bar juris-

dictions, holding that both spouses must act together

to alienate the property.

14

Hawaii was the last jurisdic-

tion to examine the nature of the tenancy after the

Married Women’s Property Act, and it adopted a full

bar approach in Sawada v. Endo:

The effect of the Married Women’s

Property Acts was to abrogate the

husband’s common law dominance

over the marital estate and to place

the wife on a level of equality with

him as regards the exercise of owner-

ship over the whole estate. The tenan-

cy was and still is predicated upon

the legal unity of husband and wife,

but the Acts converted it into a unity

of equals and not of unequals as at

common law. No longer could the

husband convey, lease, mortgage or

otherwise encumber the property

without her consent. The Acts con-

firmed her right to the use and enjoy-

ment of the whole estate, and all the

privileges that ownership of property

confers, including the right to convey

the property in its entirety, jointly

with her husband, during the mar-

riage relation. They also had the

effect of insulating the wife’s interest

in the estate from the separate debts

of her husband.... Neither husband

nor wife has a separate divisible

interest in the property held by the

entirety that can be conveyed or

reached by execution.

15

The Sawada court held that the husband and wife

could convey their residence to their child free from

the husband’s judgment creditor. After enactment of

the Hawaii Married Women’s Property Act of 1888,

therefore, the husband no longer had separate rights

that could be subject to his sole debts.

Modified bar jurisdictions, on the other hand, per-

mit a degree of creditor attachment of a debtor

spouse’s interest. In Oregon, for example, the tenancy

is viewed as a tenancy in common with an indestruc-

tible right of survivorship. Thus, a creditor will have

an interest in the rents and profits attributable to the

debtor spouse but no right of partition. If the non-

debtor spouse is the survivor, the lien is extinguished.

If the debtor spouse is the survivor, the property can be

sold to satisfy the lien.

16

10

15 VT. STAT. ANN. § 1204(e)(1) (West 2008).

11

Hennefeld v. Township of Montclair, 22 N.J. Tax 166, 188-

90 (2005). This decision was based, in part, on the more restrictive

New Jersey Domestic Partnership Act.

12

For example, Carrozzo, supra note 2, sets out various possi-

ble responses (abolition of the tenancy, altering the fifth unity to

encompass civil unions, modification of the tenancy) which bear a

striking resemblance to the responses of the various states to the

Married Woman’s Property Acts of the late 1800’s. Id. at 455-65.

13

This article’s Appendix includes a comparative chart of

those states that recognize tenancy by the entirety.

14

See Appendix.

15

Sawada v. Endo, 561 P.2d 1291, 1295 (Haw. 1977) (cita-

tions omitted).

16

Brownley v. Lincoln County, 343 P.2d 529, 531 (Or. 1959);

see also Hoyt v. American Traders, Inc., 725 P.2d 336, 337 n. 1 (Or.

1986).

34 ACTEC Journal 213 (2009)

In addition to the full bar/modified bar distinction,

those jurisdictions recognizing tenancy by the entirety

differ as to whether the tenancy may be established for

holding personal property. Most jurisdictions permit

personal property to be held tenants by the entirety:

There has always been a controversy

as to whether entireties doctrines had

any proper application to mere per-

sonal property, which always could be

disposed of absolutely by the husband

[under common law]; but there can be

no doubt that in a majority of the

United States [entireties doctrines]

were early and consistently applied in

appropriate cases to marital co-own-

ership of any types of assets.

17

Interestingly, even in full bar jurisdictions where the

entireties doctrine applies to personal property, the

entireties nature of a joint account is not necessarily

destroyed if one spouse may draw unilaterally from

that account.

18

Although the various entireties jurisdictions fol-

low two clear patterns, the variations jurisdiction by

jurisdiction are pronounced enough to require that

estate and/or asset protection planning involving

entireties property be rooted in the law of the appropri-

ate jurisdiction.

19

Given that many clients may own

properties in multiple jurisdictions, the practitioner’s

task can be complicated. In sum, estate and asset pro-

tection planning involving entireties property must be

jurisdiction specific.

III. Tenants by the Entirety and Bankruptcy

Generally, a debtor in bankruptcy can use state

law creditor protection exemptions. As explained by

the Third Circuit Court of Appeals:

The Bankruptcy Code provides two

alternative plans of exemption. Under §

522(b)(2), a debtor may elect the specif-

ic federal exemption listed in § 522(d)

(“federal exemptions”) or, under §

522(b)(3), may choose the exemptions

permitted, inter alia, under state law and

general (non-bankruptcy) federal law

(“general exemptions”).... Debtors may

select either alternative, unless a state

has “opted out” of the federal exemp-

tions category.

20

If the debtor uses the general exemptions, the

entirety property is exempt to the extent permitted by

the non-bankruptcy law; the entireties shield is respect-

ed “to the extent that such [entireties] interest… is

exempt from process under applicable non-bankruptcy

law.”

21

The applicable non-bankruptcy law appears to

be determined by the situs of real estate, not the domi-

cile of the debtor. In In re Holland,

22

for example, the

bankruptcy court used Florida law to fully exempt non-

residential property located in Florida when the

debtor’s home state of Illinois would have denied

exemption because the property was not a homestead.

In full bar states, of course, the property held by

the entireties is immune from process and fully

exempt if only one spouse is the debtor. Where, under

applicable state law, the creditors of one spouse can

reach the property, it is not exempt. The nature of

applicable state law restrictions thus determines the

degree of protection offered in bankruptcy:

“[In Massachusetts] [t]he debtor’s

interest in her [statutory] tenancy-by-

the-entirety is subject to attachment

but not subject to levy or execution at

this time and, so, the debtor’s right to

possession cannot be interfered with

unless and until the property is sold, or

debtor and her present spouse are

divorced, or she survives her spouse,

in which event the trustee will be free

to enforce his interest in the debtor’s

real estate. The trustee has a real albeit

contingent interest in the real estate,

while the debtor has an exemption

limited by the trustee’s expectancy.”

23

17

Phipps, supra note 4, at 25; see also Appendix.

18

See, e.g., Beal Bank, SSB v. Almond & Associates, 780

So.2d 45, 62 (Fla. 2001) (“[T]he ability of one spouse to make an

individual withdrawal from the account does not defeat the unity of

possession so long as the account agreement contains a statement

giving each spouse permission to act for the other.”).

19

Some even argue that the dissimilarities between those

states that continue to recognize entireties are so pronounced that

generalization is impossible. See P

OWELL, supra note 8, at 52-54.

20

In re Brannon, 476 F.3d 170, 174 (3d Cir. 2007). If a state

has opted out, the debtor must use the state exemptions.

21

Bankruptcy Code, 11 U.S.C. § 522(3)(B) (West 2008).

22

366 B.R. 825 (Bankr. N.D. Ill. 2007).

23

The Honorable Alan M. Ahart, The Liability of Property

Exempted in Bankruptcy for Pre-Petition Domestic Support Oblig-

ations After BAPCPA: Debtors Beware, 81 A

M. BANKR. L. J. 233,

243-244 (2007), quoting In re McConchie, 94 B.R. 245, 247

(Bankr. D. Mass. 1988). The discussion of Massachusetts law

involves law as applied to a principal residence.

34 ACTEC Journal 214 (2009)

Similarly, in Rhode Island a tenancy

by the entirety is subject to attach-

ment but not to levy and sale, which

means that a debtor who chooses state

exemptions can exempt entireties

property to the extent that the debtor

remains married or survives the non-

debtor spouse. In Illinois, to the

extent that a judgment creditor has a

judicial lien against a debtor’s contin-

gent interests in tenancy by entirety

property arising out of a judgment

against the debtor, these interests may

not be immune from process and

therefore may not be exempt under §

522(b)(3)(b). Similarly, in Tennessee

because a debtor’s survivorship inter-

est is not immune to execution, it

remains in the bankruptcy estate even

though the debtor’s interest in tenancy

by entirety property is otherwise

exempt under Code § 522(b)(2)(3).

24

Any exemption removes property from the bank-

ruptcy estate: “An exemption is an interest withdrawn

from the estate (and hence from the creditors) for the

benefit of the debtor.”

25

First, however, all property

interests of the debtor come into such an estate,

including a debtor’s interest in property held as a ten-

ant by the entirety.

26

Accordingly, a pre-petition trans-

fer can cause financial disaster. The bankruptcy courts

in a majority of jurisdictions have held that the trustee

can avoid any pre-petition transfer of otherwise

exempt property.

27

The fraudulent conveyance provi-

sion of the Bankruptcy Code

28

permits the debtor’s

interest in otherwise exempt entireties property that

was transferred within two years of a bankruptcy peti-

tion to be returned to the bankruptcy estate. If

returned, the property is likely no longer considered

entireties property.

29

If the debtor is not filing for bankruptcy voluntari-

ly, the debtor is at risk of the creditor forcing involun-

tary bankruptcy within the avoidance period. Involun-

tary bankruptcy unravels an intra-spousal or third

party transfer of entireties property. Involuntary peti-

tioners, however, are not common:

Congress has made it quite difficult

for creditors to bring a successful

involuntary bankruptcy petition....

Courts have been quite reluctant to

grant involuntary bankruptcy peti-

tions, interpreting the already strict

statutory requirements of involuntary

bankruptcy “in a manner which vastly

complicates creditors’ difficulties of

proof and, therefore, increases the

costs and risks associated with seek-

ing bankruptcy relief....” Such deci-

sions have made involuntary bank-

ruptcy virtually useless to creditors

seeking to collect from opportunistic

debtors.

30

Assuming a pre-petition transfer was not made,

entireties property in a full bar jurisdiction will be

exempted if none of the debts are joint debts: “A

debtor’s individual creditors [can] neither levy nor sell

a debtor’s undivided interest in the entireties property

to satisfy debts owed solely by the debtor, because a

24

Id. (citations omitted).

25

Owen v. Owen, 500 U.S. 305, 308 (1991).

26

Brannon, 476 F.3d at 174 (quoting Napotnik v. Equibank &

Parkvale Savings Assoc., 679 F.2d 316, 318 (3d Cir.1982)); In re

Ford, 3 B.R. 559, 568 (Bankr. D. Md. 1980) aff’d, 638 F.2d 14 (4th

Cir. 1981) (“[E]ven property held to be exempt will initially

become property of the estate and will remain in the estate until

such time as the exemption is taken.”).

27

“The majority includes the Fourth, Sixth, Ninth, Tenth

Circuits, lower courts in the Seventh and Eighth Circuits, and

some lower courts in the First, Second, and Eleventh Circuits …

The minority includes some lower courts in the First, Second and

Eleventh Circuits.” Dana Yankowitz, “I Could Have Exempted It

Anyway”: Can a Trustee Avoid a Debtor’s Prepetition Transfer of

Exemptible Property?, 23 E

MORY

B

ANKR

. D

EV

. J. 217, 227 n.54,

55 (2006); see also Thomas E. Ray, Avoidance of Transfers of

Entireties Property—No Harm No Foul?, 25 ABI J., Sept. 2006,

at 12.

28

11 U.S.C. § 548. There are also additional provisions per-

mitting avoidance by the trustee.

29

See 11 U.S.C. § 522(g)(1)(A) (only involuntary transfers

can be exempted); In re Swiontek, 376 B.R. 851, 865 (Bankr.

N.D. Ill. 2007) (“A small number of courts that have analyzed this

issue within the context of property transferred pre-petition out of

a tenancy by the entirety estate, have permitted the trustee to

avoid the transfer and have held that the property does not revert

back into a tenancy by the entirety estate.”); In re Paulding, 370

B.R. 11, 17-20 (Bankr. D. Mass. 2007) (holding that Chapter 7

discharge can be denied when the debtor spouse transfers

entireties property to the non-debtor spouse and then reverses

transfer before filing the petition); In re Goldman, 111 B.R. 230,

233 (Bankr. E.D. Mo. 1990) (“The parties are mistaken when they

assume that the property is conveyed back to the Debtor and his

wife as tenants by the entireties.”); In re Rotunda, 55 B.R. 386,

388 (Bankr. W.D.Pa. 1985).

30

Elijah M. Alper, Opportunistic Informal Bankruptcy: How

BAPCPA May Fail to Make Wealthy Debtors Pay Up, 107 C

OLUM.

L. REV. 1908, 1932 (2007), quoting Lawrence Ponoroff, Involun-

tary Bankruptcy and the Bona Fides of a Bona Fide Dispute,65

I

ND. L.J. 315, 351 (1990) (other citations omitted).

34 ACTEC Journal 215 (2009)

debtor’s interest in tenancy by the entireties property is

exempt from process under [the applicable state

law].”

31

Exemption may be available even if both

spouses file a petition jointly; the determinative factor

is the nature of the debts.

32

However, if the individual debtor-spouse files for

bankruptcy and he or she has a joint debt with the non-

filing spouse, the rule is markedly different. Remem-

ber: entireties property is exempt to the extent that

“such interest … is exempt from process under applic-

able non-bankruptcy law.”

33

If one spouse files for

bankruptcy and there are joint debts, the entireties

property is not exempt to the extent of those joint debts.

The existence of joint debt permits the trustee to

sell the entireties property under the Bankruptcy Code,

section 363(h).

34

The power of sale permits the trustee

to use the entireties property’s equity to satisfy the

joint creditors.

35

To the extent that entireties property

exceeds the joint debt in value, however, such equity

continues to be exempt.

36

In modified bar jurisdictions that permit creditor

attachment of one debtor-spouse’s interest, the proper-

ty may be in jeopardy of sale. The Code’s power-of-

sale provision gives the co-tenant who has not filed for

bankruptcy procedural rights to object.

37

Typically, if

the creditor would not be prejudiced, courts will not

permit sale of entireties property.

38

IV. Drye and Craft: Federal Tax Liens Trump

State-law Rights

A. A Close Look at Drye and Craft

In Drye v. United States,

39

a unanimous U.S.

Supreme Court held that federal tax liens against an

heir attached to the inheritance regardless of any dis-

claimer filed by the heir. Drye later became the basis

for United States v. Craft,

40

where the Court breached

an entireties interest to satisfy a federal tax lien levied

against one of the spouses.

Drye resolved the question of whether dis-

claiming an inheritance under state law prevents feder-

al tax liens from attaching to that interest. In Drye,an

insolvent heir validly disclaimed his inheritance under

Arkansas state law.

41

The Government argued that,

because a lien is imposed on any and all “property” or

“rights to property” belonging to the taxpayer to satis-

fy tax debts owed, it was entitled to a lien on the heir’s

inheritance, disclaimer notwithstanding.

42

In deciding the controversy, the Court looked

“initially to state law to determine what rights the tax-

payer has in the property the Government seeks to

reach, then to federal law to determine whether the

taxpayer’s state-delineated rights qualify as “property”

or “rights to property” within the compass of the fed-

eral tax lien legislation.”

43

Justice Ginsburg expound-

ed upon this “division of competence” between state

and federal law: state law determines whether the tax-

payer has a legally protected property right; federal

law determines whether a lien can attach.

44

She used

two telling examples, both dealing with insurance, to

make her point. In the first situation, the taxpayer’s

right to the cash surrender value was exposed to the

federal tax lien because the taxpayer (but not his ordi-

nary creditors) could compel payment of the cash sur-

render value.

45

That right to the cash surrender value

was “property” or a “right to property” created under

state law. For federal tax lien purposes, the taxpayer’s

right to receive that value meant that the tax lien

attached regardless of the state law that shielded the

cash surrender value from creditors’ liens. In the other

31

In re Greathouse, 295 B.R. 562, 564 (Bankr. D. Md. 2003)

(quoting In re Bell-Breslin, 283 B.R. 834, 837 (Bankr. D. Md.

2002)).

32

Bunker v. Peyton, 312 F.3d 145, 152 (4th Cir. 2002).

33

11 U.S.C. § 522(3)(B).

34

See 11 U.S.C. § 363(h).

35

Greathouse, 295 B.R. at 565.

36

In re Maloney, 146 B.R. 168, 171-72 (Bankr. W.D. Pa. 1992).

Allowing the debtor-spouse’s share of the entireties property to be

available to joint creditors only once that interest becomes subject to §

363(h) has been criticized. See, e.g., Lawrence Kalevich, Some

Thoughts on Entireties in Bankruptcy, 60 A

M

. B

ANKR

. L. J. 141 (1986)

(arguing that the debtor-spouses’ entire interest in the entireties prop-

erty should be generally available for creditors). Some courts have

applied the excess funds to individual creditors. Steven Chaneles, Ten-

ancy by the Entireties: Has the Bankruptcy Court Found a Chink in

the Armor?, 71 F

LA

. B. J., Feb. 1997, at 22, 24 & n.16.

37

See In re Wickham, 127 B.R. 9, 10-11 (Bankr. E.D. Va. 1990).

38

See In re Monzon, 214 B.R. 38, 48 (Bankr. S.D. Fla. 1997)

(“[A] single oversecured joint debt will not trigger administration

of [the entireties property]. However, the presence of an unsecured

or undersecured joint debt will subject entireties property to

administration by a Trustee…”); Gary Norton, Sales and Co-own-

ers: Cautionary Tales from the Cases, 24 ABI J., Nov. 2005, at 22

(discussing the balancing test employed by the courts in determin-

ing whether to permit a sale under § 363(h)). In one case high-

lighted in Norton’s article, In re Marks, the court found that §

363(h) could not apply without eviscerating the entire notion of a

tenancy by the entirety. No. Civ. A. 00-524, 2001 WL 868667, at

*3 (E.D. Pa. June 14, 2001). Other cases have been less protective

of the notion of entireties or of the non-filing spouse.

39

528 U.S. 49 (1999).

40

535 U.S. 274 (2002).

41

See 528 U.S. at 52.

42

Internal Revenue Code (“I.R.C.”), 26 U.S.C. § 6321(West

2008); see also id. at 54.

43

Id. at 58.

44

Id. at 58-59.

45

Id., discussing United States v. Bess, 357 U.S. 51, 56-57

(1958).

34 ACTEC Journal 216 (2009)

situation (the death benefit), the tax lien did not attach

because the taxpayer did not have access to those

funds: “By contrast, we also concluded, again as a

matter of federal law, that no federal tax lien could

attached to policy proceeds unavailable to the insured

in his lifetime.”

46

In Drye, the heir had a “valuable, transferable,

legally protected” property right to the inheritance at

the time of his mother’s death.

47

Rather than personal-

ly take this interest, the heir chose to channel his inter-

est to close family members through the act of dis-

claiming. The state law “relation back” which pro-

duces the creditor protection does not inhibit the fed-

eral taxing authority:

In sum, in determining whether a fed-

eral taxpayer’s state-law rights consti-

tute “property” or “rights to property,”

“the important consideration is the

breadth of the control the taxpayer

could exercise over the property.”

Drye had the unqualified right to

receive the entire value of his mother’s

estate (less administrative expenses)...

or to channel that value to his daugh-

ter. The control rein he held under

state law, we hold, rendered the inher-

itance “property” or “rights to proper-

ty” belonging to him within the mean-

ing of [the IRC], and hence subject to

the federal tax liens that sparked this

controversy.

48

The pivotal factor was the heir’s control over effective

enjoyment of the inheritance:

The disclaiming heir or devisee, in

contrast [to someone merely declin-

ing an offered inter vivos gift], does

not restore the status quo, for the

decedent cannot be revived. Thus the

heir inevitably exercises dominion

over the property. He determines who

will receive the property—himself if

he does not disclaim, a known other if

he does. This power to channel the

estate’s assets warrants the conclusion

that Drye held “property” or a “right

to property” subject to the Govern-

ment’s liens.

49

Craft held that property held as tenants by the

entirety is subject to a federal tax lien against one

spouse. Craft may be seen as an extension of Drye

but, unlike Drye, it was a split decision with Justices

Stevens, Scalia and Thomas dissenting. According to

Justice O’Connor’s opinion for the Court, whether the

lien attaches to one spouse’s interest in an entireties

tenancy is ultimately a question of federal law. In ana-

lyzing this question, the Court followed the Drye

approach: it looked first to state law to determine what

rights a taxpayer had in the specific property the gov-

ernment sought; then it decided whether the taxpayer’s

rights qualified as property or rights to property under

federal law.

50

Justice O’Connor concluded that the

debtor-taxpayer had a sufficient number of presently-

existing “sticks” in the “bundle” comprising the ten-

ants by the entirety property right to give rise to an

attachable interest.

51

Among others, these rights

included rights of possession, of income, and of sale

proceeds if the non-debtor spouse agreed to the sale.

52

Blackstone’s legal fiction, ingrained by state law, that

neither tenant had an interest separable from the other

did not control the scope of the federal tax lien: “[I]f

neither of them had a property interest in the entireties

property, who did? This result not only seems absurd,

but would also allow spouses to shield their property

from federal taxation by classifying it as entireties

property, facilitating abuse of the federal tax system.”

53

Justices Stevens, Scalia and Thomas dissent-

ed. Justice Thomas objected to what he saw as a fed-

eralization of the law governing rights to property:

Before today, no one disputed that the

IRS, by operation of § 6321, steps

into the taxpayer’s shoes, and has the

same rights as the taxpayer in proper-

ty or rights to property subject to the

46

Id.

47

Id. at 60.

48

Id. at 61, quoting Morgan v. Commissioner, 309 U.S. 78, 83

(1940) (other citations omitted).

49

Id. at 61, citing Adam J. Hirsch, The Problem of the Insol-

vent Heir, 74 CORNELL L. REV. 587, 607-608 (1989). Two ACTEC

Academic Fellows are cited in Drye: Adam Hirsch and Jeffrey Pen-

nell. Adam Hirsch is cited generally to support the Court’s holding

(as seen above). Jeffrey Pennell is quoted for the basic proposition

that a “qualified” disclaimer under I.R.C. § 2518 does not preclude

the federal tax lien from attaching because the statute only applies

for gift or estate transfer tax purposes. See id. at 57 n.3.

50

535 U.S. at 278.

51

Id. at 285.

52

Id. at 282, 283.

53

Id. at 286.

34 ACTEC Journal 217 (2009)

lien. I would not expand the nature of

the legal interest the taxpayer has in

the property beyond those interests

recognized under state law.

54

Justice Scalia added:

[A] State’s decision to treat the mari-

tal partnership as a separate legal enti-

ty, whose property cannot be encum-

bered by the debts of its individual

members, is no more novel and no

more “artificial” than a State’s deci-

sion to treat the commercial partner-

ship as a separate legal entity, whose

property cannot be encumbered by

the debts of its individual members.

55

Drye turned on a determination of whether Mr.

Drye could unilaterally elect to receive what would

otherwise be a property right. A single co-tenant by the

entireties, of course, is not in an analogous position

because one co-tenant does not unilaterally control the

enjoyment of that property right. Justice Thomas

argued that federal tax liens should only be attachable

to rights that a taxpayer actually personally possesses:

That the Grand Rapids property does

not belong to Mr. Craft under Michi-

gan law does not end the inquiry,

however, since the federal tax lien

attaches not only to “property” but

also to any “rights to property”

belonging to the taxpayer. While the

Court concludes that a laundry list of

“rights to property” belonged to Mr.

Craft as a tenant by the entirety, it

does not suggest that the tax lien

attached to any of these particular

rights. Instead, the Court gathers

these rights together and opines that

there were sufficient sticks to form a

bundle, so that “respondent’s hus-

band’s interest in the entireties prop-

erty constituted ‘property’ or ‘rights

to property’ for the purposes of the

federal tax lien statute.

But the Court’s “sticks in a bundle”

metaphor collapses precisely because

of the distinction expressly drawn by

the statute, which distinguishes

between “property” and “rights to

property.” The Court refrains from

ever stating whether this case involves

“property” or “rights to property”

even though § 6321 specifically pro-

vides that the federal tax lien attaches

to “property” and “rights to property”

“belonging to” the delinquent taxpay-

er, and not to an imprecise construct

of individual rights in the estate suffi-

cient to constitute “property” or

“rights to property” for the purposes

of the lien.

Rather than adopt the majority’s

approach, I would ask specifically, as

the statute does, whether Mr. Craft

had any particular “rights to property”

to which the federal tax lien could

attach. He did not. Such “rights to

property” that have been subject to

the § 6321 lien are valuable and

“pecuniary,” i.e., they can be attached,

and levied upon or sold by the Gov-

ernment. With such rights subject to

lien, the taxpayer’s interest has ripen

into a present estate of some form and

is more than a mere expectancy, and

thus the taxpayer has an apparent

right to channel that value to another.

In contrast, a tenant in a tenancy by

the entirety not only lacks a present

divisible vested interest in the proper-

ty and control with respect to the sale,

encumbrance, and transfer of the

property, but also does not possess the

ability to devise any portion of the

property because it is subject to the

other’s indestructible right of sur-

vivorship. This latter fact makes the

property significantly different from

community property, where each

spouse has a present one-half vested

interest in the whole, which may be

devised by will or otherwise to a per-

son other than the spouse.

56

B. The Craft Aftermath

That the tax lien attaches to the debtor-tax

payer’s entireties interest does not sever the tenancy

54

Id. at 291-92 (quotations and citations omitted).

55

Id. at 289.

56

Id. at 294-98 (quotations and citations omitted).

34 ACTEC Journal 218 (2009)

automatically. It permits the Internal Revenue Service

(“IRS”) to either (i) administratively seize and sell the

taxpayer’s interest or (ii) foreclose the federal tax lien

against the entireties property. The administrative

option is problematic for the IRS:

Because of the nature of the entireties

property, it would be difficult to

gauge what market there would be for

the taxpayer’s interest in the property.

The amount of any bid would in all

likelihood be depressed to the extent

that the prospective purchaser, given

the rights of survivorship, would take

the risk that the taxpayer may not out-

live his or her spouse. In addition, a

prospective purchaser would not

know with any certainty if, how, and

to the extent to which the rights

acquired in an administrative sale

could be enforced … Levying on cash

and cash equivalents held as entireties

property does not present the same

impediments as seizing and selling

entireties property.

57

The most likely lien enforcement procedure is

foreclosure.

58

Foreclosure is supervised by a court

under Internal Revenue Code (“IRC”) section 7403 and

any individual with an interest in the property must be

joined and given an opportunity to be heard. The court

may order sale of the whole property and then distribute

the sale’s proceeds as it sees fit, considering the parties’

interests and that of the Government.

59

The value of

each spouse’s interest is an issue of fact. This exchange

from Craft’s oral argument is illustrative:

Question (by the Court): “But in your

review, you always value the taxpay-

er’s interest at 50 percent?”

Answer (by Mr. Jones): “No, I think

in the Rodgers—well, if the proper-

ty’s been sold, yes. If the property

hasn’t been sold, and we’re talking

about in a foreclosure context, I

believe the Rodgers court goes

through the example of the varying

life expectancies of the two tenants,

and which one—and I believe what

the Court in Rodgers said was that

each of them should be treated as if

they have a life estate plus a right of

survivorship, and the Court explains

how that could well—I think in the

facts of Rodgers resulted in only 10

percent of the proceeds being applied

to the husband’s interest and 90 per-

cent being retained on behalf of the

spouse, but—”

60

Craft did not address specifically how the

debtor spouse’s interest should be valued. Rodgers,

the case referenced above, involved the judicial sale to

enforce federal tax liens against a homestead property

where a non-debtor spouse also held an interest.

61

In

that case, the court ran calculations “only for the sake

of illustration” that assumed the protected interest was

the same as a life estate interest. Based upon calcula-

tions of the terminated interest (the life interest)

amount, a substantial part of the sales proceeds should

be allocated to the non-debtor spouse (89% for a 50

year old). This “illustration,” of course, focused on

fully compensating the non-delinquent spouse for his

or her potential loss without regard to a full valuation

of the delinquent spouse’s property interest.

Courts have not followed the Rodgers

approach when applying Craft. A few courts have

endorsed the use of comparable life expectancies.

62

Most courts, however, simply split the proceeds in

half. In Popky v. United States,

63

the Third Circuit

Court of Appeals relied upon the equal rights each

spouse has to the “bundle of sticks” that constitutes

entireties property to support a fifty percent-fifty per-

cent split. It also relied upon “sound policy” for such

an approach to valuation, finding that “an equal valua-

tion is far simpler and less speculative” than the valua-

tion based on life expectancies.

64

By its terms, Craft is limited to federal tax

cases. To quote one case, “Craft gives no indication

57

I.R.S. Notice 2003-60, 2003-39 I.R.B. (Sept. 29, 2003),

available at http://www.irs.gov/irb/2003-39_IRB/ar13.html.

58

See Steve R. Johnson, Why Craft Isn’t Scary, 37 REAL PROP.

P

ROB. & TR. J. 439, 473-77 (2002).

59

I.R.C. § 7403(c).

60

Transcript of Craft Oral Argument 15. “Rodgers” refers to

United States v. Rodgers, 649 F.2d 1117 (5th Cir. 1981), rev’d, 461

U.S. 677 (1983) and Ingram v. Dallas Dep’t of Hous. & Urban

Rehab, 649 F.2d 1128 (5th Cir. 1981), vacated, 461 U.S. 677

(1983).

61

461 U.S. at 698-99.

62

See In re Murray, 318 B.R. 211, 214 (Bankr. M.D. Fla.

2004).

63

419 F.3d 242, 245 (3d. Cir. 2005).

64

See also In re Estate of Johnson, 355 F. Supp.2d 866, 870

(E.D. Mich. 2004); In re Gallivan, 312 B.R. 662, 666 (Bankr. W.D.

Mo. 2004).

34 ACTEC Journal 219 (2009)

that the reasoning therein should be extended beyond

federal tax law.”

65

Although section 544 of the Bank-

ruptcy Code accords a trustee the rights and powers of

a hypothetical “creditor that extends credit to the

debtor at the time of the commencement of the case,”

66

courts have declined to extend such rights and powers

to a trustee based on the Government being such a

hypothetical creditor.

67

In refusing to extend Craft,

courts reject empowering bankruptcy trustees to use

the Bankruptcy Code’s “strong arm clause” to get at

entireties property in non-tax cases. Craft has been

extended, however, to fines and forfeitures arising

from federal criminal cases: “Although Craft only

dealt with tax liens, Congress has unequivocally stated

that criminal fines are to be treated in the same fashion

as federal tax liabilities.”

68

If the federal tax lien is not acted upon, and one

spouse dies, the property goes to the survivor either free

of the lien or not, depending on who is the survivor:

When a taxpayer dies, the surviving

non-liable spouse takes the property

unencumbered by the federal tax lien.

When a non-liable spouse predeceas-

es the taxpayer, the property ceases to

be held in a tenancy by the entirety,

the taxpayer takes the entire property

in fee simple, and the federal tax lien

attaches to the entire property.

69

In Craft, the property was quitclaimed to the

non-debtor spouse after the debtor spouse incurred the

tax lien. The lower courts held that no fraudulent con-

veyance was involved because no lien could attach.

This point was not preserved on appeal. Justice

O’Connor makes clear, however, that this issue will be

present in future entireties tenancy cases involving fed-

eral tax liens: “Since the District Court’s judgment was

based on the notion that, because the federal tax lien

could not attach to the property, transferring it could

not constitute an attempt to evade the Government

creditor, in future cases the fraudulent conveyance

question will no doubt be answered differently.”

70

V. Planning in Full Bar Jurisdictions:

Post Judgment Transfers and/or Disclaimers

in Full Bar Jurisdictions

Generally, except in Craft situations, the full bar

jurisdictions permit a debtor spouse to convey the

entirety property to the non-debtor spouse or for both

spouses to transfer the property to third persons without

running afoul of the fraudulent conveyance statute.

71

The planning implication is obvious: Married individu-

als with exposure to liability should hold as much of

their property as possible by the entireties.

72

Once lia-

bility against one spouse is triggered, the at-risk spouse

may transfer the property to the non-debtor spouse.

73

In

Watterson v. Edgerly,

74

for example, a husband had a

judgment lien filed against him but not against his wife.

The husband transferred his interest in their entirety

property to his wife for no consideration.

75

The wife

thereupon signed a will containing a testamentary

spendthrift trust for the benefit of her husband, and died

shortly thereafter.

76

The Maryland Court of Special

Appeals upheld the conveyance of the real estate

despite the judgment lien against the husband:

When, as here, a husband and wife

hold title as tenants by the entireties,

the judgment creditor of the husband

or of the wife has no lien against the

property held as entireties, and no

standing to complain of a conveyance

which prevents the property from

falling into his grasp.

77

65

In re Ryan, 282 B.R. 742, 750 (Bankr. D.R.I. 2002); see

also Musolina v. Sinnreich, 391 F.3d 1295, 1298 (11th Cir. 2004);

In re Kelly, 289 B.R. 38, 43-44 (Bankr. D. Del. 2003).

66

11 U.S.C. § 544(a)(1).

67

Schlossberg v. Barney, 380 F.3d 174, 180-82 (4th Cir.

2004); In re Greathouse, 295 B.R. 562, 565-67 (Bankr. D. Md.

2003).

68

In re Hutchins, 306 B.R. 82, 91 (Bankr. D. Vt. 2004) (drug

trafficking); see also United States v. Fleet, 498 F.3d 1225 (11th

Cir. Fla. 2007) (wire fraud, money laundering, etc.); United States

v. Godwin, 446 F. Supp. 2d 425 (E.D.N.C. 2006) (embezzlement

from federally insured bank). In Maryland, by contrast, the court

has refused to permit the sale of a truck used in drug trafficking

when the vehicle was held tenants by the entirety. This was under

the state forfeiture statute and it was pre-Craft. Maryland v. One

1984 Toyota Truck, 533 A.2d 659 (Md. 1987).

69

I.R.S. Notice 2003-60.

70

Craft, 535 U.S. at 289 (citations omitted).

71

See Martin J. McMahon, Annotation, Validity and Effect of

One Spouse’s Conveyance to Other Spouse of Interest in Property

Held as Estate by the Entireties, 18 A.L.R. 23, § 8 (5th ed. 1994).

72

Individuals who typically have liability exposure include

physicians, lawyers, public accountants, and business executives

with Sarbanes-Oxley exposure.

73

See above, however, for the danger of making such a con-

veyance before the filing of a voluntary or involuntary petition in

bankruptcy.

74

388 A.2d 934 (Md. 1978).

75

Id. at 937.

76

Id.

77

Id. at 939 (citation omitted); see also Donvito v. Criswell,

439 N.E.2d 467, 473-74 (Ohio 1982); L&M Gas Co. v. Leggett,

161 S.E.2d 23, 27-28 (N.C. 1968).

34 ACTEC Journal 220 (2009)

This technique is not restricted to intra-spousal

transfers. In Sawada v. Endo,

78

a judgment was ren-

dered against a husband for an automobile tort. He and

his wife conveyed their entireties property to their chil-

dren. The Supreme Court of Hawaii found that the

conveyance could not be a fraudulent one because the

creditors had no attachable interest.

79

Thus, as illustrated above, as long as bankruptcy

can be postponed or avoided, transferring an entireties

tenancy with only a single debtor-spouse can move the

property free of the debt. This is clearly an important

benefit of the entireties form of ownership. From an

asset protection point of view, entireties ownership is a

valuable tool that ought to be preserved.

Using the flexibility afforded by the Internal Rev-

enue Code section 2518, an estate plan can be crafted

anticipating that a qualified disclaimer will be used by

a surviving spouse to fund a credit shelter or qualified

terminable interest property (“QTIP”) trust.

80

Under

the Internal Revenue Service’s 1997 regulations, dis-

claimer of the “survivorship interest” in entirety prop-

erty is permitted within nine months of death (not the

creation of the interest).

81

This provides an opportuni-

ty to preserve the asset protection qualities of entireties

without unduly compromising estate planning.

82

A creditor problem may exist at the first spouse’s

death. If the debtor spouse predeceases the non-debtor

spouse, no action is necessary to have the property

pass to the survivor lien free if the property is held as

entireties. If the debtor spouse survives, however, a

disclaimer may be useful to avoid the lien on that

spouse’s portion of the entirety property.

Other than for federal tax liens, a disclaimer is typ-

ically not a transfer for fraudulent conveyance purpos-

es in most jurisdictions.

83

As explained by one state’s

highest court:

A review of the jurisprudence of other

states shows that it is the majority view

that a renunciation under the applica-

ble state probate code is not treated as

a fraudulent transfer of assets under

the UFTA [Uniform Fraudulent Trans-

fers Act], and creditors of the person

making a renunciation cannot claim

any rights to the renounced property in

the absence of an express statutory

provision to the contrary.

84

In Pauw v. Agee,

85

a federal district court permitted a

debtor to disclaim his inheritance but then rent the

property back from his brother who received the prop-

erty through operation of the disclaimer: “This view

[that a disclaimer will defeat the judgment against the

debtor-disclaimant] corresponds with the majority

view that a creditor cannot prevent a debtor from dis-

claiming an inheritance.”

86

New York also follows the

majority rule. In Estate of Oot,

87

the court upheld the

78

561 P.2d 1291 (Haw. 1977). This case is quoted at length

above in section II on state variations.

79

Id. at 1295-97.

80

I.R.C. § 2518(b)(4).

81

I.R.S. Treas. Reg. § 25.2518-2(c)(4)(i) (West 2008). A spe-

cial rule, however, applies to joint bank accounts between spouses

“if a transferor may unilaterally regain the transferor’s own contri-

butions without the consent of the other cotenant…”. Id. at

(c)(4)(iii). For such joint tenancies, the surviving joint tenant may

not disclaim any portion of the account attributable to considera-

tion furnished by that surviving joint tenant. As noted in Section II

on state variations, above, a joint account subject to the order of

either spouse may nevertheless be an entireties account. Presum-

ably such an account would fail the definition of “joint account”

contained in these regulations.

82

To backstop the plan, each spouse should create a durable

power of attorney authorizing another person to disclaim on his or

her behalf in the case that he or she is incompetent at the time of

their spouse’s death. Also, of course, the trust receiving the dis-

claimed property cannot permit a power of appointment to the dis-

claiming spouse. The retention of entireties property until the

death of one spouse necessarily involves a high degree of trust

between spouses; each spouse must be certain that the survivor will

trigger the creditor shelter or QTIP trust if appropriate. Increasing-

ly estate plans are being designed to give the surviving spouse such

control over his or her destiny. See Jeffrey N. Pennell, Estate Plan-

ning for the Next Generation(s) of Clients: It’s Not Your Father’s

Buick, Anymore, 34 ACTEC J., S

UMMER 2008, at 2; see also Henry

M. Ordower, Trusting Our Partners: An Essay on Resetting the

Estate Planning Defaults for an Adult World, 31 REAL PROP. PROB.

& TR. J. 313 (1996).

83

Neither the 2002 Uniform Disclaimer Property Interest Act

(“UDPIA”) nor the earlier uniform acts directly address the issue

of a disclaimer by an insolvent disclaimant. All of the uniform acts

relied on the law of each jurisdiction to sort out the issue. See

Adam J. Hirsch, Revisions In Need of Revising: The Uniform Dis-

claimer of Property Interests Act, 29 FLA. ST. U.L. REV. 109

(2001). Separate considerations are also involved in Medicaid

planning. See U

NIF. DISCLAIMER OF PROP. INTERESTS ACT § 13 cmt

(amended 2006). Nothing in the general discussion herein on dis-

claimers is meant to address Medicaid planning issues.

84

Essen v. Gilmore, 607 N.W.2d 829, 835 (Neb. 2000). For a

summary of the treatment of disclaimers in other states, see also

In re Bright, 241 B.R. 664, 671-72 (B.A.P. 9th Cir. 1999) (uphold-

ing a pre-petition disclaimer). In contrast, post-petition dis-

claimers will not work. In re Schmidt, 362 B.R. 318 (Bankr. W.D.

Tex. 2007).

85

No. 2:98-2318-23, 2000 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 22323 (D.S.C.

2000).

86

Id. at *19.

87

408 N.Y.S.2d 303 (1978).

34 ACTEC Journal 221 (2009)

renunciation of a legacy regardless of the dis-

claimant’s creditors’ claims: “It is with no small

degree of reluctance that the court arrives at this deci-

sion. However, until the legislature in its wisdom pro-

vides some statutory vehicle for protecting creditors

against frustration of their claims, unfortunate results

may again occur.”

88

A minority of states hold that a disclaimer is a

fraudulent transfer. Pennsylvania courts, for example,

have held a disclaimer to be a fraudulent transfer.

“While a solvent legatee may freely renounce and

refuse a gift or legacy, an insolvent legatee may not do

so since his renunciation would constitute a fraudulent

conveyance, void as to creditors under section 4 of the

Uniform Fraudulent Conveyance Act of May 21,

1921.”

89

Several states have statutes that prohibit dis-

claimers by insolvent heirs. Disclaimers are prohibited

in Florida, for example, when “the disclaimant is insol-

vent when the disclaimer becomes irrevocable.”

90

The 2002 rendition of the Uniform Disclaimer of

Property Interests Act (“UDPIA”) bars disclaimers if,

before the disclaimer becomes effective, the dis-

claimant “voluntarily assigns, conveys, encumbers,

pledges or transfers the interest sought to be dis-

claimed.”

91

Earlier versions of the uniform acts had

similar language barring disclaimers after an encum-

brance but without the “voluntary” element. Interpret-

ing a disclaimer act without the “voluntarily” aspect,

one state court barred a disclaimer when the dis-

claimant was subject to a prior lien. After deciding

that the act’s encumbrance provision trumped its

“relation back”

92

provision, the Alabama Supreme

Court held that a creditor’s lien against the disclaimant

rendered the disclaimer ineffective.

93

The court

focused on the heir’s direct interest in estate property:

When John Thomas Bigham died

intestate on June 25, 1984, the legal

title to a one-half interest in his real

property vested eo instante in Bobby

Bigham; however, it vested subject to

the statutory power of the administra-

trix to take possession of it and obtain

an order to have it sold for payment of

the debts of his father’s estate.

94

In Pennington, a judgment creditor had perfected her

lien against all of the disclaimant’s property before the

disclaimant’s father died; therefore, the lien acted as an

encumbrance of the disclaimant’s share. Under the cir-

cumstances of that case, a disclaimer after the attach-

ment of the lien constituted a fraudulent conveyance.

95

Similarly, In re Kalt’s Estate,

96

the California

Supreme Court found a disclaimer to violate the fraud-

ulent conveyance act. Kalt’s Estate is important

because it served as the basis of many other decisions

constituting the minority view. California, however,

subsequently legislatively reversed Kalt’s Estate:

The few states which appear to follow

the minority view that a disclaimer can

constitute a fraudulent conveyance

base their holdings on the California

case of In re Kalt’s Estate…The hold-

ing of In re Kalt’s Estate,however,

was overruled by the California legis-

lature when it enacted a statute provid-

ing specifically that a disclaimer is not

a fraudulent transfer. See Cal. Prob.

Code § 283 (West 1991).

97

In sum, given the variations among the states, no

universal default planning rule can be applied. Never-

theless, in full bar states that do not treat a disclaimer

as a fraudulent conveyance, preserving, or indeed cre-

ating, entireties ownership coupled with estate plan-

ning to be triggered by a disclaimer at the first death,

should become a default recommendation.

88

Id. at 306.

89

Est. of Centrella, 20 Pa. D.&C.2d 486, 490 (1960) (cita-

tions omitted).

90

FLA. STAT. ANN. 739.402(2)(d) (West 2008); see also MINN.

STAT. ANN. § 525.532(6) (West 2008).

91

UNIF. DISCLAIMER OF PROP. INTERESTS ACT § 13(b)(2).

92

The “relation back” doctrine of earlier versions of the

UDPIA has been replaced in the new Act. “The disclaimer takes

effect as of the time the instrument creating the interest becomes

irrevocable, or, if the interest arose under the law of intestate suc-

cession, as of the time of the intestate’s death.” U

NIF. DISCLAIMER

OF

PROP. INTERESTS ACT § 6(b)(1). The Comment to that section

states: “This Act continues the effect of the relation back doctrine,

not by using the specific words, but by directly stating what the

relation back doctrine has been interpreted to mean.” The term

“relation back” is used in the Article as short-hand for the revised

section.

93

Pennington v. Bigham, 512 So.2d 1344 (Ala. 1987).

94

Id. at 1345-46.

95

Id. at 1347. The 2002 amendments to the UDPIA, of

course, adds “voluntary” to the list of actions barring a disclaimer.

This addition “reflects the numerous cases holding that only

actions by the disclaimant taken after the right to disclaim has

arisen will act as a bar.” U

NIF. DISCLAIMER OF PROP. INTERESTS ACT

§ 13 cmt. Maryland, for example, adopted this provision of the

UDPIA and added that “Creditors of the disclaimant have no inter-

est in the property disclaimed.” M

D. CODE ANN., EST. & TRUSTS §

9-202(f)(2) (West 2008).

96

108 P.2d 401 (Cal. 1940).

97

Pauw, 2000 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 22323 at *20.

34 ACTEC Journal 222 (2009)

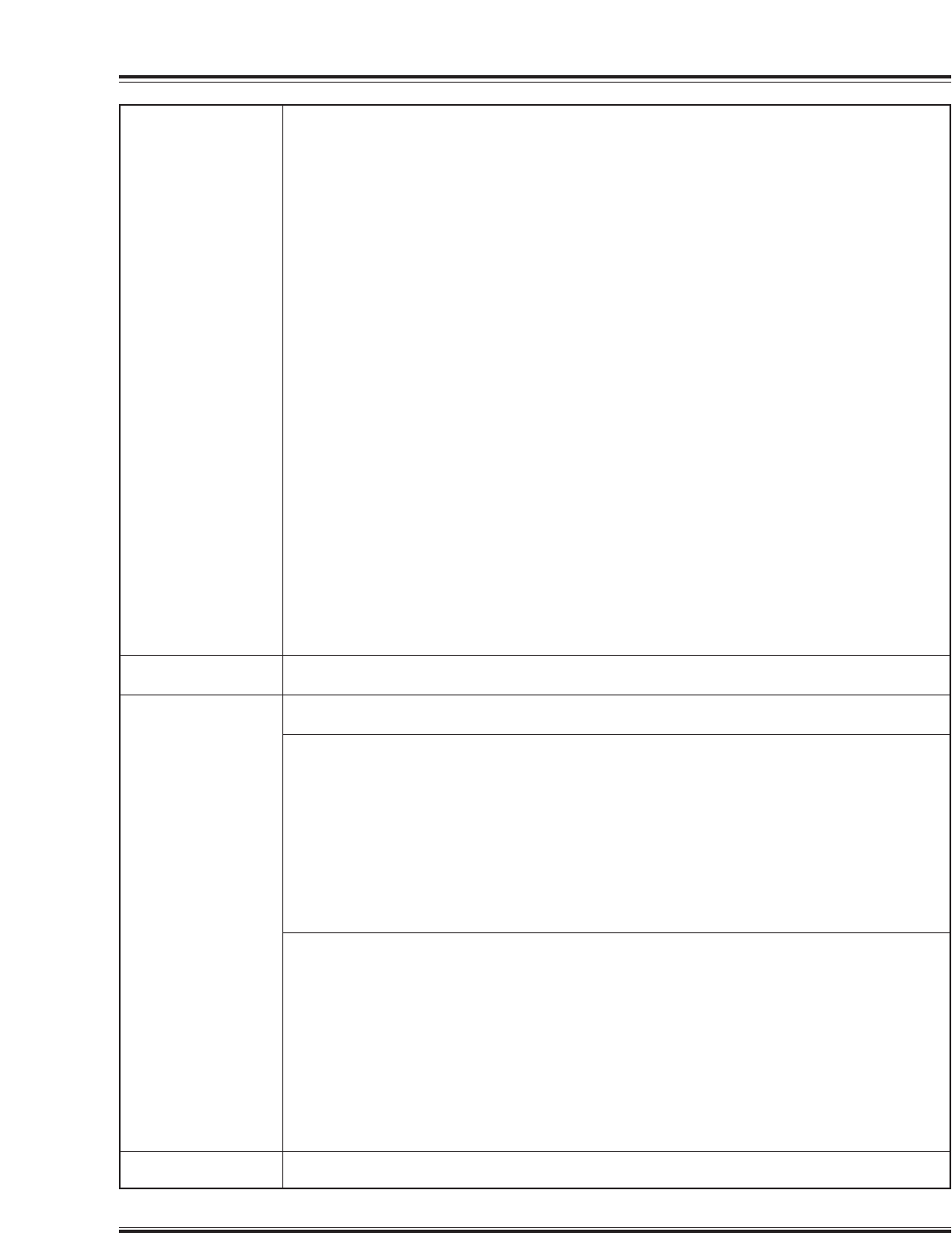

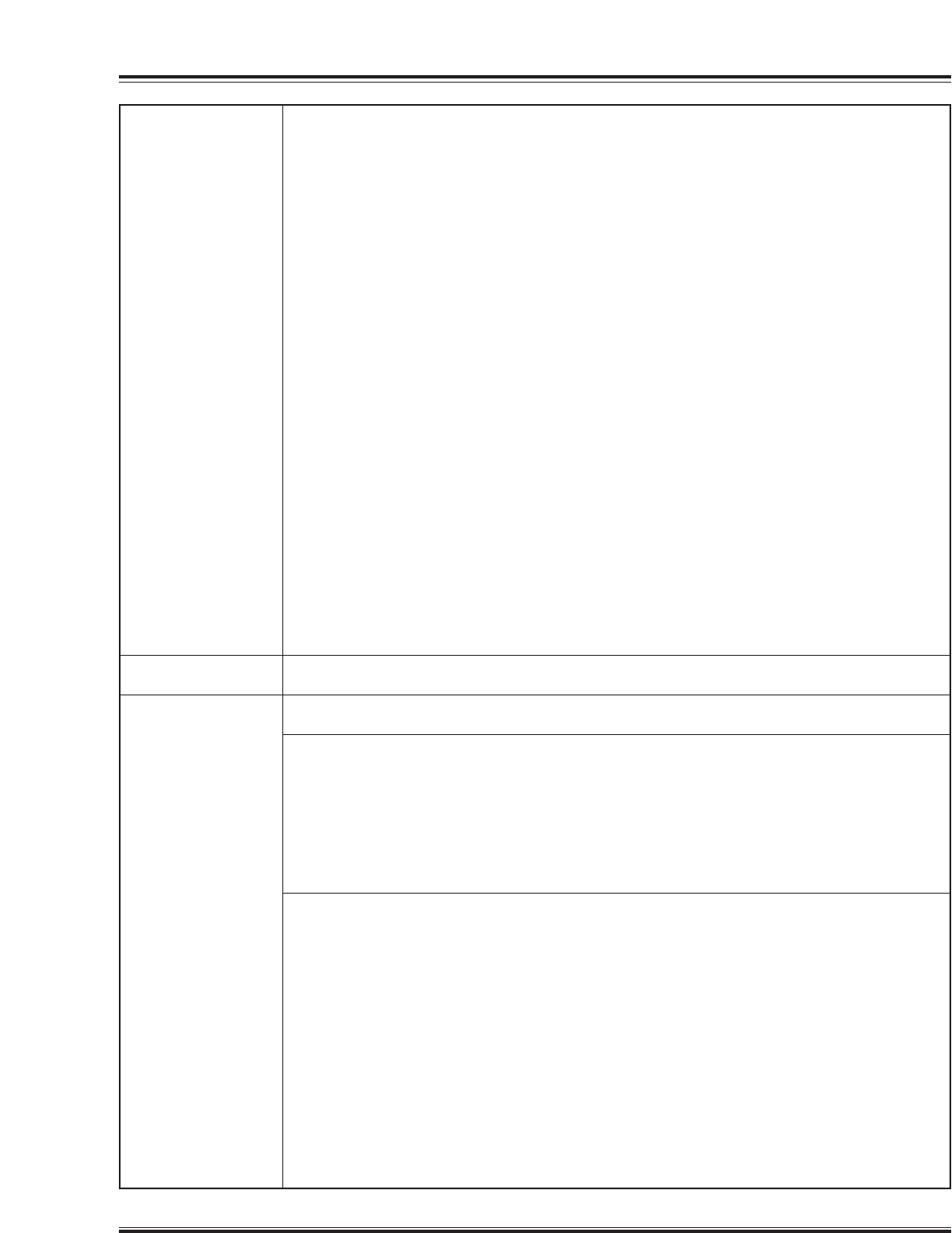

Alaska Type of Bar: Modified.

Effect of Judgment Creditor of One Spouse: Levy and sale permitted. Partition may be

forced.

Type of Property: Real and personal property. Alaska Stat. § 34.15.140 recognizes ten-

ants by the entirety in real property. See Faulk v. Est. of Haskins, 714 P.2d 354 (Alaska

1986), recognizing tenants in the entirety in personal property.

Comment: Alaska Stat. § 09.38.100(a) provides that a creditor of one spouse “may obtain

a levy on and sale of the interest” of the debtor spouse. The creditor may force partition

or severance of the non-debtor spouse’s interest. This is subject, however, to other

exemptions such as the homestead exemption. Alaska Sta. §§ 09.38.100(a)-(b).

Arkansas Type of Bar: Modified.

Effect of Judgment Creditor of One Spouse: Creditor may execute but may not defeat

non-debtor spouse’s right of survivorship interest. Creditor gets one-half of rents and

profits but cannot displace non-debtor spouse.

Type of Property: Real and personal property. “[O]nce property, whether personal or real

is placed in the names of persons who are husband and wife, without specifying the man-

ner in which they take, there is a presumption that they own the property as tenants by the

entireties …” Sieb’s Hatcheries, Inc. v. Lindley, 111 F.Supp. 705, 716 (W.D. Ark. 1953).

Ark. Code § 23-47-204 lists entireties as one of the accounts banks shall offer under the

multiple party account rules.

Comment: “Execution against a spouse’s interest in a tenancy by the entirety has long

been permitted even though partition has not. [Earlier cases have] affirmed the principle

that property owned as husband and wife as tenants by the entirety may be sold under

execution to satisfy a judgment against the husband, subject to the wife’s right of sur-

vivorship … [A] purchaser of the interest of one tenant by the entirety cannot oust the

other tenant from possession, and can only claim one-half of the rents and profits. The

remaining tenant is not only entitled to possession plus one-half of the rents and profits,

but the right of survivorship is not destroyed or in anywise affected.” Morris v. Solesbee,

892 S.W.2d 281, 282 (Ark. Ct. App. 1995) (citations omitted).

Delaware Type of Bar: Full.

Effect of Judgment Creditor of One Spouse: Not subject to attachment.

Type of Property: Real and personal property. See Rigby v. Rigby, 88 A.2d 126 (Del. Ch.

1952), on cattle, and Widder v. Leeds, 317 A.2d 32 (Del. Ch. 1974), on partnership inter-

est. “It has likewise been held that, in the absence of proof to the contrary, a joint bank

account opened in the conjunctive form in the name of a husband and wife may create a

tenancy by the entireties, and this status is not altered by the fact that either may withdraw

the funds therefrom.” Widder, 317 A.2d at 35 (citations omitted).

Comment: Delaware courts have stated, at various times, that a judgment against one

spouse does not create a lien on entireties property under Delaware law: “It is settled in

APPENDIX

Asset Protection Variations Among Jurisdictions Recognizing Tenancy by the Entirety

34 ACTEC Journal 223 (2009)

Delaware that a creditor of one spouse, such as Ms. Johnson, may not place a lien on real

property held as tenants by the entireties. See Steigler v. Insurance Co. of North America,

384 A.2d 398 (1978) ( “interest of neither [husband nor wife] can be sold, attached or

liened ‘except by [their] joint act’”); Citizens Savings Bank, Inc. for the Use of Govatos v.

Astrin, 61 A.2d 419 (1948)… so the creditors of one spouse cannot reach the interest the

debtor holds in the estate.” Johnson v. Smith, No. Civ. A. 13585, 1994 WL 643131, *2

(Del. Ch. Oct. 31, 1994).

In Mitchell v. Wilmington Trust Co., 449 A.2d 1055 (Del. Ch. 1982), aff’d 461 A.2d 696

(Del. 1983), a husband obtained a mortgage from a bank by fraudulently bringing a

woman to execute loan settlement documents that, in fact, was not his wife. The court

held that the forgery failed to operate to bind the tenant by entirety property. Before the

wife received notice of the forgery, the husband transferred the title to the wife as a mar-

ital settlement. The transfer was not held a fraudulent transfer because the wife lacked

knowledge of the fraudulent transfer (being then unaware of the purported lien) and paid

valid consideration (the release of her husband’s marital obligations). The court held that

the bank acquired an inchoate lien in the property which became extinguished upon the

husband’s transfer of the property to his wife without knowledge and for valid considera-

tion. Given that no lien attaches in any event, there should have been no reason for the

court to reach the fraudulent conveyance aspect of the case. In Wilmington Savings Fund

Society v. Kaczmarczyk, No. Civ. A. 1769-N, 2007 WL 704937 (Del. Ch. March 1, 2007),

the Chancery Court found that a post-judgment transfer by the debtor husband to his non-

debtor wife violated the fraudulent conveyance act. As opposed to Mitchell, the Kacz-

marczyk court held that the transfer, while purportedly made pursuant to the divorce dis-

cussions, did not include fair consideration because the parties reconciled. Arguably, nei-

ther case should have involved an examination of the fraudulent conveyance statute.

These cases necessarily raise a cautionary note as to whether a lien attaches.

District of Columbia Type of Bar: Full.

Effect of Judgment Creditor of One Spouse: Not subject to attachment.

Type of Property: Real and personal property. See Morrison v. Potter, 764 A.2d 234

(D.C. 2000), where a joint checking account was presumed to be held by tenants by the

entirety despite the right, under the account agreement, of either spouse to withdraw:

“[C]ourts have not interpreted the unilateral right of a spouse to withdraw funds as an

alienation of the marital property. Instead, ‘[w]here a deposit is made payable to either

spouse, agency or authority exists by implication … Indeed, with respect to a joint bank

account held by a husband and wife, each spouse acts as the other spouse’s agent, and

both have properly consented to the other spouse’s withdrawals in advance, thus satisfy-

ing the non-alienation requirement of a tenancy by the entireties” (citations omitted).

Comment: In Est. of Wall, 440 F.2d 215 (D.C. 1971), the husband died holding a tenant

by the entirety interest in a fund. The husband’s creditors unsuccessfully sought the

estate’s “interest” in the fund: “[T]he full complement of common law characteristics

of co-tenancy by the entireties is preserved. A unilaterally indestructible right of sur-

vivorship, an inability of one spouse to alienate his interest, and, importantly for this

case, a broad immunity from claims of separate creditors remain among its vital inci-

dents.” Id. at 219. In American Wholesale Corp. v. Aronstein, 10 F.2d 991 (1926), the

husband’s transfer of his interest in entireties property to his wife was held not to be a

fraudulent conveyance because the entireties property was not subject to a lien by his

judgment creditors.

Florida Type of Bar: Full.

Delaware

continued

34 ACTEC Journal 224 (2009)

Florida continued Effect of Judgment Creditor of One Spouse: No attachment.

Type of Property: Real and personal property. See Beal Bank, SSB v. Almand & Assoc.,

780 So.2d 45 (Fla. 2001), announcing a presumption in favor of entireties of joint bank

account unless the signature card specifically disclaims a tenancy by the entireties: “[A]s

we have explained, the ability of one spouse to make an individual withdrawal from the

account does not defeat the unity of possession so long as the account agreement contains

a statement giving each spouse permission to act for the other.” This presumption, that

jointly owned property held by a married couple is entireties, is rebuttable. In re Hinton,

378 B.R. 371 (Bankr. M.D. Fla. 2007).

Comment: In Passalino v. Protective Group Securities, 886 So.2d 295 (Fla. 2004), hus-

band and wife owned rental property as tenants by the entirety. They sold the property and

the proceeds were held by their attorney intended as a deposit on another tenants by the

entirety property. The fund retained its tenant by the entirety characteristics and was not

subject to the judgment solely against the husband. In Hunt v. Covington, 200 So. 76 (Fla.

1941), the Florida Supreme Court described the attributes of tenant by the entirety: “It is