1

Good Practice

in Human Rights

Compliant Sexual

Offences Laws in

the Commonwealth

Good Practice in Human Rights

Compliant Sexual Offences Laws

in the Commonwealth

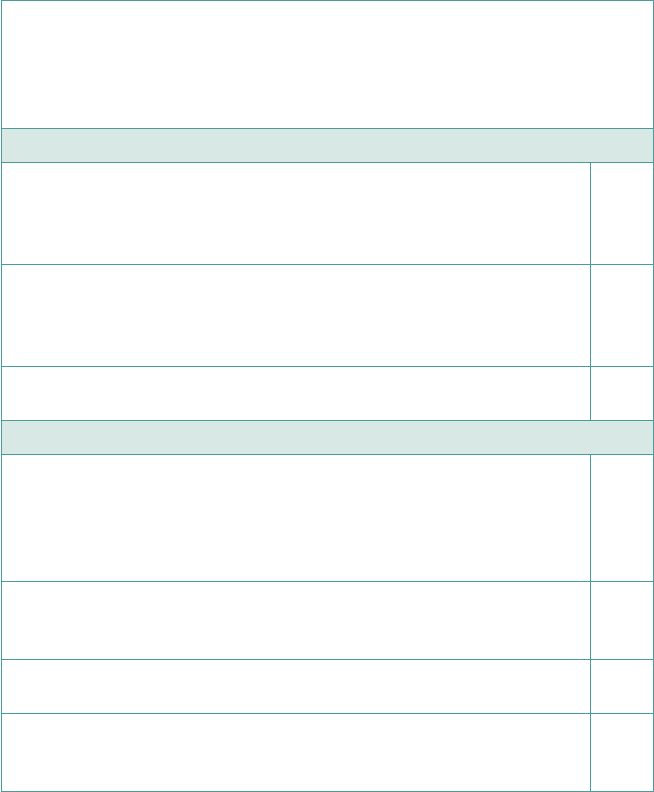

TABLE OF FIGURES I

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS II

NOTE ON AUTHORS III

ABOUT THIS STUDY 1

1. OVERVIEW 1

2. BACKGROUND 3

3. SCOPE 4

4. METHODOLOGY 5

5. STRUCTURE OF THE REPORT 6

PART A: ANALYTICAL FRAMEWORK FOR IDENTIFYING A ‘GOOD PRACTICE’ LAW 8

6. INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS LAW AS THE BENCHMARK 9

Deriving Criteria from International Human Rights Law 10

7. RAPE/SEXUAL ASSAULT LAWS 14

Rape Myths and the Law 15

Progress of Reforms 17

Sources for the Criteria for Good Practice: Rape/Sexual Assault Laws 18

Criteria for Good Practice Rape/Sexual Assault Laws 26

8. SEXUAL OFFENCES AND PEOPLE WITH DISABILITY 34

Disability and Sexual Conduct 34

The Law and People With Disability 37

Sources for the Criteria for Good Practice: Sexual Offences Laws and People with Disability

42

Criteria for Good Practice Sexual Offences Laws in Relation to People with Disability 44

9. CONSENSUAL SAME-SEX SEXUAL ACTIVITY 51

Sources for the Criteria for Good Practice: Consensual Same-Sex Sexual Activity Laws 56

Criteria for Good Practice Consensual Same-Sex Sexual Activity Laws 58

10. AGE OF CONSENT TO SEXUAL ACTIVITY 63

Sources for the Criteria for Good Practice: Age of Consent Laws 63

Criteria for Good Practice Age of Consent Laws 65

Contents

Good Practice in Human Rights Compliant Sexual Offences Laws in the Commonwealth

PART B: CASE STUDIES OF GOOD PRACTICE LAWS 68

11. RAPE/SEXUAL ASSAULT LAWS 69

The Pacific: Fiji 69

Checklist for Fiji’s Rape/Sexual Assault Laws 80

The Pacific: Solomon Islands 88

Checklist for Solomon Islands’ Rape/Sexual Assault Laws 97

Africa: Namibia 103

Checklist for Namibia’s Rape/Sexual Assault Laws 111

Caribbean and the Americas: Guyana 117

Checklist for Guyana’s Rape/Sexual Assault Laws 126

12. SEXUAL OFFENCES AND PEOPLE WITH DISABILITY 132

Africa: Seychelles 132

Checklist for Seychelles’ Laws Dealing with Disability and Sexual Offences 136

13. CONSENSUAL SAME-SEX SEXUAL ACTIVITY 142

The Pacific: Tasmania, Australia 142

Checklist for Tasmania’s Laws on Consensual Same-Sex Sexual Activity 149

Asia: India 152

Checklist for India’s Laws on Consensual Same-Sex Sexual Activity 157

Caribbean and the Americas: Belize 160

Checklist for Belize’s Laws on Consensual Same-Sex Sexual Activity 163

Africa: Seychelles 166

Checklist for Seychelles’ Laws on Consensual Same-Sex Sexual Activity 169

Summary of Decriminalisation in Four other Commonwealth Countries 172

14. AGE OF CONSENT TO SEXUAL ACTIVITY 176

Commonwealth Countries and Consent to Engage in Sexual Activity 176

15. CONCLUSION 180

ANNEXURES 182

1. GLOSSARY OF TERMS 183

2. TIMETABLE OF DECRIMINALISATION OF SAME-SEX SEXUAL ACTIVITY

IN THE COMMONWEALTH 186

Good Practice in Human Rights Compliant Sexual Offences Laws in the Commonwealth

Table of Figures

Figure 1: Myths underlying discriminatory rape/sexual assault laws 15

Figure 2: Examples of positive reforms in the Pacific region 18

Figure 3: Expert treaty bodies call for reform of sexual offences laws 24

Figure 4: Criteria for good practice: Rape/sexual assault laws 27

Figure 5: Models of disability: The medical model and the social model 36

Figure 6: Derogatory language used to describe people with disability in Commonwealth

sexual offences laws 38

Figure 7: Criminalising of consensual sexual activity with people with disability 40

Figure 8: Example of disability-specific sentencing provision 41

Figure 9: Criteria for good practice: Sexual offences and people with disability 45

Figure 10: Decriminalisation of male same-sex sexual activity in Commonwealth global

south nations 52

Figure 11: Criteria for good practice: Consensual same-sex sexual activity 59

Figure 12: Criteria for good practice: Age of consent to sexual activity 65

Figure 13: Case summary – State v Vakadranu (Fiji High Court) – How the law on consent

is applied 72

Figure 14: Case summary – Balelala v State (Fiji Court of Appeal) – The end of the

corroboration rule in Fiji 75

Figure 15: Summary of Fiji’s rape/sexual assault laws 77

Figure 16: Checklist for Fiji’s rape/sexual assault laws 80

Figure 17: Meaning of ‘person in position of trust’ in the Solomon Islands Penal Code 90

Figure 18: Summary of Solomon Islands’ rape/sexual assault laws 93

Figure 19: Checklist for Solomon Islands’ rape/sexual assault laws 97

Figure 20: Summary of Namibia’s rape/sexual assault laws 107

Figure 21: Achieving rape law reform in Namibia 108

Figure 22: Checklist for Namibia’s rape/sexual assault laws 111

Figure 23: Summary of Guyana’s rape/sexual assault laws 123

Figure 24: Checklist for Guyana’s rape/sexual assault laws 126

Figure 25: Seychelles’ rape case involving victim with disability 133

Figure 26: Checklist for Seychelles’ disability and sexual offences laws 136

Figure 27: The effects of criminalisation 143

Figure 28: Decriminalisation in Tasmania 149

Figure 29: Checklist for Tasmania’s laws on consensual same-sex sexual activity 149

Figure 30: Checklist for India’s laws on consensual same-sex sexual activity 157

Figure 31: Checklist for Belize’s laws on consensual same-sex sexual activity 163

Figure 32: Checklist for Seychelles’ laws on consensual same-sex sexual activity 169

i

Acknowledgements

This report has been produced by the Human Dignity Trust on behalf of the

Equality & Justice Alliance, a consortium comprising the Human Dignity Trust,

Kaleidoscope Trust, Sisters For Change and The Royal Commonwealth Society.

The Human Dignity Trust is very grateful to the individual authors of this report,

Indira Rosenthal, Rodney Croome and Robin Banks. Editorial oversight was

provided by Téa Braun, Director of the Human Dignity Trust, and Grazia

Careccia, Programme Manager of the Human Dignity Trust.

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank Jan Linehan and Anna Arstein-

Kerslake for their expert advice, and Anita Deutchmann, Siane Richardson,

Amelia von Stieglitz, Taylor Bachand, Siobhan Galea and Grace Williams for

their research support.

The authors and the Human Dignity Trust wish to acknowledge and

thank the many individuals who agreed to be interviewed or otherwise

assisted with the research for this project. Their insights, commentary

and experience were invaluable. Regional experts, as well as experts

from civil society and the legal sector, including judges and former

judges, prosecutors, public solicitors, criminal lawyers and government

lawyers from the countries of focus participated in this research.

This report is funded by the UK Government, in support of the commitments

made during the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting 2018.

ii

Good Practice in Human Rights Compliant Sexual Offences Laws in the Commonwealth

Note on Authors

Indira Rosenthal is an Australian lawyer with expertise in the areas of human rights law and

international criminal law focusing on gender-related issues. Formerly a senior lawyer with the

Australian federal government on sex discrimination as well as international law, Indira also has

extensive experience working with non-government organisations. She was Gender and Legal

Adviser with the International Secretariat of Amnesty International and Counsel with Human

Rights Watch’s International Justice Program. As an independent consultant, Indira has worked

on a wide range of human rights and gender research projects, including on law reform, policy

development and capacity building, primarily in the areas of violence against women and girls,

access to justice and international criminal law. In addition to the Trust, Indira has consulted for

the World Health Organisation, UN Women, the UK Government, the Family Court of Australia,

the University of Tasmania and Amnesty International. Indira is an adjunct member of the Faculty

of Law at the University of Tasmania and a member of the Commonwealth Group of Experts on

Reform of Sexual Offences, Hate Crimes and Related Laws to Eliminate Discrimination against

Women and Girls and LGBT People (CWGE).

Rodney Croome has been an advocate for the equal rights of LGBT+ people for over thirty

years. He fronted the campaign to decriminalise homosexuality in Tasmania, Australia in the

1990s. More recently he was one of the nation’s most recognised advocates for marriage

equality. He also played a pivotal role in the drafting and passage of Tasmania’s ground-

breaking anti-discrimination, civil partnership, same-sex parenting, criminal expungement,

and transgender rights legislation. In keeping with his commitment to equality, Rodney has

also worked on ensuring schools, the public service, businesses, and the community more

broadly, are inclusive of LGBT+ people. Rodney grew up on a dairy farm in Tasmania and

has a history degree from the University of Tasmania. He has written numerous articles and

essays on LGBT+ equality, as well as several books. In honour of his work for equality and

inclusion, Rodney was made a Member of the Order of Australia in 2003 and named

Tasmanian Australian of the Year in 2015.

Robin Banks holds a Bachelor of Laws from the University of New South Wales (NSW).

In 2000 she was admitted to practice as a barrister and solicitor in the Supreme Court of

NSW and the High Court of Australia. Robin grew up in Tasmania and has worked in

government at the Canadian Human Rights Commission, in the private legal and consulting

sector (as a lawyer and Senior Associate at Henry Davis York in Sydney, and as a Director

of Equality Building, a Tasmanian Company set up to advise on accessibility and inclusion)

and in not-for-profit organisations (including as CEO of the Public Interest Advocacy Centre,

Australia’s largest public interest law centre, Director of the Public Interest Law Clearing

House, the NSW scheme for pro bono legal work, and as Co-ordinator of the NSW Disability

Discrimination Legal Centre). Robin was Tasmania’s Anti-Discrimination Commissioner from

2010 to 2017. Robin has been involved in a broad range of human rights advocacy activities

and campaigns, and has a strong background in disability and LGBT+ rights in particular.

Robin is currently a PhD candidate at the University of Tasmania researching potential reforms

to discrimination law. She is also a member of the CWGE.

iii

1

About this Study

1. Overview

1.1 The purpose of this study is to inform, inspire and aid reform of discriminatory

and harmful laws on sexual offences in member states of the Commonwealth.

The study will assist Commonwealth countries that are seeking to reform their

sexual offences laws by providing models of ‘good practice’ laws from other

Commonwealth countries across all regions of the world. While this report is

not a technical or legislative drafting guide, it provides technical support and

encouragement for countries that are beginning the process of undertaking the

necessary legislative reform to bring certain categories of sexual offences laws

into compliance with international human rights law for the better protection of

their citizens and societies.

1.2 The focus of the report is on four areas of sexual offences laws, namely rape/

sexual assault, age of consent for sexual conduct, treatment of consensual

same-sex sexual activity between adults, and sexual offences in relation to

people with disability.

1.3 Outdated and discriminatory laws in these areas, many of which originate in

colonial-era penal codes, continue to operate in many member states of the

Commonwealth. For example, in many countries the rape/sexual assault laws

continue to:

discriminate on the basis of sex, gender, sexual orientation, gender identity

or disability,

permit rape/sexual assault in marriage,

require corroboration by a third party,

exclude oral rape, anal rape, and rape/sexual assault with objects, and/or

exclude rape/sexual assault of men and boys.

1.4 Laws prescribing the age of consent for sexual conduct which differentiate

between people on the basis of their sex, gender, sexual orientation or gender

identity are also prevalent. These laws add to the harmful effects of discriminatory

sexual offences provisions and perpetuate discrimination and violence against

women and girls, and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and other gender

non-conforming (LGBT+

1

) people.

1.5 Many countries also criminalise consensual sexual activity with people with

disability. While the motivation for these laws may be to protect people with

disability from sexual abuse and exploitation, the blanket criminalisation is

Good Practice in Human Rights Compliant Sexual Offences Laws in the Commonwealth

paternalistic, and denies people with disability enjoyment of their fundamental

human rights, including to legal autonomy and freedom from discrimination.

Some laws also still contain derogatory colonial-era language, such as ‘imbecile’

or ‘idiot’ in referring to people with disability.

1.6 Nearly half of the 72 jurisdictions in the world that still criminalise consensual

same-sex sexual activity between adults in private are members of the

Commonwealth (34 countries plus the New Zealand associate jurisdiction of

the Cook Islands), most of which inherited these Victorian-era laws from British

colonial powers.

1.7 Discriminatory sexual offences laws continue to cause untold harm in all

aspects of the lives of those individuals affected by them. They are at odds

with international and regional human rights norms, as well as most national

constitutions. They undermine the enjoyment of a wide range of human rights,

and perpetuate violence, stigma and discrimination. They particularly affect

women, children, LGBT+ people, people with disability, and other marginalised

groups, such as First Nations

2

peoples. They also undermine the health and

prosperity of entire societies. For example, the United Nations has called rape a

global ‘pandemic’,

3

and human rights compliant rape laws are critical to properly

preventing, punishing and protecting against it. Many married women in many

countries around the world are wholly unprotected from sexual violence in their

own homes, and have little or no control over their own sexual and reproductive

health. Laws that criminalise LGBT+ people put them outside the protection of the

law, fostering a climate of fear and stigma in which discrimination, exclusion,

harassment, and physical and sexual violence are commonplace. People with

disability continue to be denied legal autonomy by laws that assume a lack of

ability to consent to and enjoy sexual activity.

The law is an important means available to a society to demonstrate that

certain behaviours are unacceptable, and to hold [violators] to account.

A Framework to Underpin Action to Prevent Violence Against Women, UN Women, 2015

1.8 A country’s laws, if they are non-discriminatory and enforced consistently and

fairly, can play a vital role in protecting people equally, deterring people from

committing offences, providing redress for those affected by violations, and

eliminating stigma and abuse of vulnerable or marginalised groups. They can

also protect and guarantee fundamental human rights, and encourage shifts in

attitude and behaviour at a societal and cultural level. On the other hand, if

laws are discriminatory or unfair, either on paper or in their application, they

can cause harm to individuals, communities and whole societies, as well as to

the rule of law itself. For example, a discriminatory rape law will deter victims/

survivors from coming forward and reporting the crime. Discriminatory rules of

evidence can re-traumatise victims/survivors and deny them access to justice

while the perpetrator is not held to account. Differential treatment of different

3

victims/survivors of sexual abuse can send a signal that some people are less

worthy of equal protection, leaving them more exposed to abuse.

1.9 Several countries in the Commonwealth have updated their sexual offence laws

to remove their discriminatory impact and language, for example, defining rape/

sexual assault in gender-neutral terms, eliminating marital rape exemptions,

applying consent-based (rather than act-based or personal characteristic-

based) legal frameworks for sexual activity, and equalising the age of consent

regardless of sex, gender or sexual orientation. These are the laws highlighted

in this study.

1.10 Reform of (largely) colonial-era sexual offence laws has been a slow and

incremental process around the Commonwealth, and is not yet complete in most

countries. The laws assessed as good practice models for the purposes of this

study meet fundamental criteria based on international human rights standards.

However, they may not be perfect, and there are often different options for

human rights compliant sexual offences laws, which is why we refer to ‘good

practice’ laws rather than ‘best practice’ laws.

1.11 This study uses international human rights law as the benchmark for assessing

a law, and describes the international legal norms relevant to sexual offences.

The rationale used in this report for applying international human rights law is

explained below.

2. Background

2.1 This research was commissioned by the Human Dignity Trust (the Trust), as

part of its work with the Equality & Justice Alliance

4

—a two-year programme

announced by the UK Government at the April 2018 Commonwealth Heads of

Government Meeting (CHOGM) in London by UK Prime Minister Theresa May.

5

In offering UK support for Commonwealth governments that want to reform

discriminatory laws, the Prime Minister said:

Across the world, discriminatory laws made many years ago continue to affect

the lives of many people, criminalising same-sex relations and failing to protect

women and girls. I am all too aware that these laws were often put in place

by my own country. They were wrong then, and they are wrong now. […] I

deeply regret both the fact that such laws were introduced, and the legacy of

discrimination, violence and even death that persists today.

As a family of nations, we must respect one another’s cultures and traditions.

But we must do so in a manner consistent with our common value of equality,

a value that is clearly stated in the Commonwealth charter. […]

[T]he UK stands ready to support any Commonwealth member wanting to

reform outdated legislation that makes […] discrimination possible.

6

Good Practice in Human Rights Compliant Sexual Offences Laws in the Commonwealth

2.2 A core focus of the two-year programme is support for reform of colonial-era

sexual offences laws that discriminate against women and girls and LGBT+ people,

among others. As part of that support, the Trust—with the assistance of experts

from around the Commonwealth—is producing research and information designed

to inform, inspire and assist Commonwealth governments that are considering

embarking on reform of such laws. The research is Commonwealth-focused,

enabling member states to learn from other countries in the Commonwealth that

have already successfully undertaken reforms.

2.3 This research complements other independent research that the Trust is

undertaking, including a series of practical in-depth case studies on the process

of sexual offences law reform in various Commonwealth countries, which will be

available on the Trust’s website as they are completed.

7

3. Scope

3.1 The focus of this study is on good practice legislation in the following four main

areas of law:

1. rape/sexual assault,

8

2. age of consent for sexual conduct,

3. treatment of consensual same-sex sexual activity between adults, and

4. sexual offences in relation to people with disability.

3.2

We consider a representative sample of sexual offences laws from Commonwealth

jurisdictions across each of the Commonwealth’s five regions: Africa, Asia,

Caribbean and the Americas, Europe, and the Pacific. Where appropriate, the

study also considers relevant common law developments. Sample good practice

laws from the following jurisdictions are included in this study:

Tasmania (Australia)

Belize

Canada

England and Wales

Fiji

Guyana

India

Namibia

Seychelles

Solomon Islands

South Africa

3.3

This report does not purport to be a comprehensive survey of every good practice

law on sexual offences in the Commonwealth. There will be examples of good

5

practice sexual offences laws in other Commonwealth countries not covered in

this report. Equally, there are certain categories of sexual offences laws that are

outside the scope of this report and are therefore not covered. For example,

this report does not address laws criminalising sex work/prostitution; this is a

major area of study in its own right. Similarly, we do not consider adultery laws,

though discriminatory framing of such laws still exists in some Commonwealth

countries. Incest laws and domestic/family violence laws are not covered in

detail, while laws criminalising LGBT+ public advocacy or cultural expression,

and affectional, sexual or gender identity expression in public (for example,

under public decency laws) are also outside the scope of this study.

3.4

It is important to emphasise that laws, no matter how “good” they may be from a

legal and human rights perspective, will not be effective without implementation

and a range of complementary and interdependent legislative and non-legislative

measures, including:

supportive and complementary policies in areas such as health, social

welfare and policing;

ongoing training of the justice, law enforcement, health, child protection

and social support sectors;

the provision of sufficient financial and human resources for law

enforcement and implementation, including for the court system;

measures for effective and equal access to the formal justice system,

including access to appropriate and affordable legal representation;

an integrated data collection programme on the various kinds of victims

and perpetrators of crime and the impact of the laws; and

support for a broad-spectrum approach to increase legal literacy and

address discriminatory attitudes and practices at the community level.

3.5

These critical measures are outside the scope of this report, which focuses on

the law itself as a structural imperative from which other measures can and

must flow.

4. Methodology

4.1

The research for this study was conducted through literature and legislation

reviews and interviews with key stakeholders in the representative sample

countries. Desk-based research focused on specific sexual offences laws, a

literature search to identify baseline good practice standards for sexual offence

legislation, and identification of international and regional legal standards on

sexual offences in:

international and regional treaties;

commentary from treaty bodies;

state practice;

Good Practice in Human Rights Compliant Sexual Offences Laws in the Commonwealth

international policy statements (such as the Beijing Platform for Action and

the Yogyakarta Principles and Yogyakarta plus10 Principles);

9

and

expert guidance on human rights compliant sexual offences legislation

(such as the UN Handbook on Legislation for Violence Against Women

2010 (the UN Handbook)).

10

4.2

A series of interviews with key stakeholders provided critical technical and

contextual information, focusing particularly on rape/sexual assault and

the decriminalisation of consensual same-sex sexual activity. The interviews

were semi-structured and took place via telephone or Skype. We interviewed

people from three primary cohorts: (1) government, including the justice sector;

(2) academic, legal and other experts; and (3) civil society.

4.3

Criminal legislation dealing with sexual conduct and people with disability

11

is

an important topic that is often overlooked when considering reform of sexual

offences laws. Outdated and paternalistic attitudes to people with disability

remain widespread. Our research on this topic focused on the scholarship and

did not include interviews. However, we see this as a crucial area for further,

dedicated research and law reform advocacy.

5. Structure of the report

5.1

The report is divided into two parts. Part A describes and explains the criteria

used in this study to assess if a particular law is a good practice law based on

its human rights compliance. Part B sets out case studies of good practice laws

drawn from across the Commonwealth’s five regions. The country case studies

include a brief description of the current law, and how reforms changed the

previous outdated law. Where information was available, we have also included

a summary of the law reform process and an overview of the extent to which the

law is being implemented and enforced, highlighting any challenges to effective

implementation or enforcement. Charts for each country case study show how

the law measures up against the benchmark criteria for a good practice law in

that area.

5.2

It is important to note that the country case studies are based on laws that are

publicly available online. To the extent possible, we have verified that the laws

referred to are the most up-to-date. It is also important to note that the country

case studies do not purport to be comprehensive analyses of a country’s laws.

5.3

The report also contains the following annexures:

1. Glossary

2. Timeline of decriminalisation in the Commonwealth.

7

1 The authors adopt the term ‘LGBT+’ throughout this report, as it is the most inclusive term to encom-

pass people of every sexual orientation and gender identity, including people who do not identify

with any gender, however described or named.

2 First Nations peoples are sometimes referred to as ‘Indigenous’ or ‘Aboriginal’ peoples.

3 Ban Ki Moon, ‘Remarks on the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Wom-

en’ (Speech delivered at the UN Headquarters, New York, 25 November 2014) <https://www.

un.org/sg/en/content/sg/speeches/2014-11-25/remarks-international-day-elimination-vio-

lence-against-women> (last accessed March 2019).

4 The other organisations of the Alliance are the Kaleidoscope Trust, The Royal Commonwealth Soci-

ety, and Sisters for Change.

5 The Human Dignity Trust (2019) <http://www.humandignitytrust.org/pages/NEWS/News?News-

ArticleID=578> (last accessed March 2019).

6 The Hon Theresa May, UK Prime Minister, ‘Speech’ (Speech delivered to the Commonwealth Joint

Forum Plenary, UK, 17 April 2018) <https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/pm-speaks-at-

the-commonwealth-joint-forum-plenary-17-april-2018> (last accessed March 2019).

7 The Human Dignity Trust (2019) Resources <https://www.humandignitytrust.org/hdt-resources/>

(last accessed March 2019).

8 In this report, we use the term ‘rape/sexual assault’ when referring to non-consensual physical

assaults of a sexual nature.

9 Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women, GA Res 48/104, UN GAOR, 48

th

sess,

85

th

plen mtg, Agenda Item 111, UN Doc A/RES/48/104 (20 December 1993). Another impor-

tant policy statement for example is the Beijing Platform for Action, adopted at the Fourth World

Conference on Women in Beijing in 1995, Report of the Fourth World Conference on Women,

Beijing, China, 4-15 September 1995. About the Yogyakarta Principles (2016) < http://yogyakar-

taprinciples.org/principles-en/about-the-yogyakarta-principles/> (last accessed May 2019), and

Yogyakarta Principles plus 10 (2016) < https://yogyakartaprinciples.org/principles-en/yp10/>

(last accessed May 2019).

10 UN Women, Handbook for Legislation on Violence against Women (2012) (UN Handbook)

<http://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2012/12/handbook-for-legisla-

tion-on-violence-against-women> (last accessed March 2019).

11 The United Nations, in the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disability (see n20 for full

details), adopts terminology that puts the person first, i.e., people, persons or person with dis-

ability or disabilities. This ‘person first’ approach is reflected within the Commonwealth in, for

example, Australian, Canadian, Indian and Rwandan disability rights advocacy. An alternative

terminology, based on similar underpinning principles, is ‘disabled person’ or ‘disabled persons’

or ‘disabled people’. This approach is reflected within the Commonwealth in, for example, Eng-

land, New Zealand and Fiji. This report adopts the UN terminology of ‘person …’, ‘persons …’

or ‘people with disability’.

Good Practice in Human Rights Compliant Sexual Offences Laws in the Commonwealth

Part A: Analytical Framework for Identifying a ‘Good Practice’ Law

Part A describes the general principles applied to assessing whether a law is a ‘good practice’

law from a human rights perspective. The Part covers general criteria and criteria specific to

each of the four areas of law addressed in the report. Each section on specific criteria contains

a summary list of the relevant criteria, and briefly explains the international law sources of these.

These criteria are then used in the country case studies in Part B.

Part A describes the general principles applied to assessing

whether a law is a ‘good practice’ law from a human

rights perspective. The Part covers general criteria and

criteria specific to each of the four areas of law addressed

in the report. Each section on specific criteria contains a

summary list of the relevant criteria, and briefly explains the

international law sources of these. These criteria are then

used in the country case studies in Part B.

Part A:

Analytical Framework

for Identifying

a ‘Good Practice’ Law

9

6. International human rights law

asthe benchmark

6.1 The analysis of laws as good practice models in this report is based on a set of

benchmark criteria drawn from international human rights law.

12

International

human rights law provides a clear and binding prescription for legislating

effectively on sexual offences, and includes protections that must be addressed

in each area of law. These include guarantees of:

equality before the law and equal protection of the law,

freedom from discrimination in the enjoyment of all fundamental rights,

respect for human dignity,

protection of bodily integrity, including freedom from torture and cruel,

inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment,

protection of children from abuse and exploitation, and

the rights of people with disability.

6.2 All countries, including members of the Commonwealth, are bound under

international law to respect, protect and fulfil these rights for their citizens,

either as states parties to the international and regional treaties in which these

norms are set out, or under customary international law.

13

This obligation

includes taking legislative and other measures to guarantee these rights and

freedoms. For example, the International Covenant on Civil and Political

Rights (ICCPR)

14

states:

Where not already provided for by existing legislative or other measures,

each State Party to the present Covenant undertakes to take the necessary

steps, in accordance with its constitutional processes and with the provisions

of the present Covenant, to adopt such laws or other measures as may be

necessary to give effect to the rights recognized in the present Covenant.

15

This same requirement can be found in all international and regional human

rights treaties.

16

6.3 The underlying fundamental principles applied to laws in this study are derived

from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) as subsequently

detailed in the following human rights treaties:

Good Practice in Human Rights Compliant Sexual Offences Laws in the Commonwealth

United Nations

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR),

International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR),

17

Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination Against

Women (CEDAW),

18

Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC),

19

Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD).

20

Regional

African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR),

21

The Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the

Rights of Women in Africa (Maputo Protocol),

22

American Convention on Human Rights (ACHR),

23

Inter-American Convention on the Prevention, Punishment, and Eradication

of Violence against Women (Convention of Belém do Pará),

24

and

Council of Europe, Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence

Against Women and Domestic Violence (Istanbul Convention).

25

Deriving criteria from international human rights law

6.4 Human rights treaties use the language of ‘obligations’ on states parties, and

of the ‘rights’ of individuals to be protected, respected and fulfilled by states. It

is possible to derive from these obligations and rights a set of benchmarks that

states must meet in their laws (and policies) relating to sexual offences.

6.5 Treaty body committees, regional human rights courts and national courts have

elaborated on and clarified the scope and meaning of many treaty principles.

Expert agencies at the UN and at the regional level have further distilled this

guidance into practical advice, including model legislation, on how to make

human rights compliant laws in some areas, such as on rape/sexual assault.

26

This guidance has also informed the criteria used to assess the sexual offence

laws in this report.

6.6 Underscoring each of the criteria identified in this study are the fundamental

human rights principles of substantive equality and respect for the inherent

dignity of every person. These principles are the foundation of human rights,

and are expressed in all human rights treaties. For a law to be assessed as a

good practice law, it must adhere to these core principles.

11

6.7 It follows that sexual offences laws must be non-discriminatory, must protect

an individual from harm, and must respect their personal agency and bodily

integrity. Where laws create criminal offences, they should appropriately

balance the competing interests of the rights of an accused person to a fair trial

with the rights of a complainant.

CORE PRINCIPLES FOR A GOOD PRACTICE SEXUAL OFFENCES LAW

Respects human dignity

Ensures substantive equality

Does not discriminate

Protects personal agency & bodily integrity

6.8 The next section identifies and describes the human rights-based criteria necessary

for a good practice law in each of the areas of law covered in this report.

Good Practice in Human Rights Compliant Sexual Offences Laws in the Commonwealth

12 International human rights law is dynamic and evolving, and the standards for the protection of

rights, as well as the content of those rights, has developed over time. In our analysis of national laws

for this study, we have applied the most up-to-date articulations and interpretation of international

human rights norms and standards.

13 For example, the prohibition of gender-based violence; Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination

Against Women, General Recommendation No. 35 on violence against women, updating

general recommendation 19, 67

th

sess, UN Doc CEDAW/C/GC/35 (26 July 2017) <https://

tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/treatybodyexternal/Download.aspx?symbolno=CEDAW/C/

GC/35&Lang=en> (last accessed March 2019).

14 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, opened for signature 19 December 1966,

GA Res 2200A (XXI), 999 UNTS 171, UN Doc A/6316 (1966) (entered into force 23 March

1976). <https://treaties.un.org/Pages/ViewDetails.aspx?chapter=4&clang=_en&mtdsg_no=IV-

4&src=IND>. Forty-two Commonwealth countries have ratified or acceded to the ICCPR, with a

further four having signed but not yet ratified. This represents 87% of Commonwealth countries

having adopted the full suite of states party obligations.

15 Ibid art 2.2.

16 For example, Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW),

opened for signature 1 March 1980, 1249 UNTS 13, (entered into force 3 September 1981) art 2

<https://treaties.un.org/Pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=IND&mtdsg_no=IV-8&chapter=4&lang=en>.

Fifty-two Commonwealth countries have ratified or acceded to CEDAW. This represents 98% of

Commonwealth countries having adopted the full suite of states party obligations; Convention on

the Rights of the Child (CRC), opened for signature 1 March 1980, 1577 UNTS 3, (entered into

force 2 September 1990) art 4 <https://treaties.un.org/pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=IND&mtdsg_

no=IV-11&chapter=4&lang=en>. Fifty-three Commonwealth countries have ratified or acceded to the

CRC. This represents 100% of Commonwealth countries having adopted the full suite of states party

obligations; American Convention on Human Rights, art 2.

17 International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), opened for signature

16 December 1966, GA Res 2200A (XXI), 993 UNTS 3, UN Doc A/6316 (1966) (entered into

force 3 January 1976) <https://treaties.un.org/pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=IND&mtdsg_no=IV-

3&chapter=4&clang=_en>. Thirty-nine Commonwealth countries have ratified or acceded to the

ICESCR. This represents 74% of Commonwealth countries having adopted the full suite of states

party obligations.

18 CEDAW, above n16, art 1.

19 CRC, above n16.

20 Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), opened for signature 30 March 2007,

2515 UNTS 3, (entered into force 3 May 2008) <https://treaties.un.org/Pages/ViewDetails.

aspx?src=TREATY&mtdsg_no=IV-15&chapter=4&lang=_en&clang=_en>. Forty-six Commonwealth

countries have ratified or acceded to the CRPD. This represents 87% of Commonwealth countries

having adopted the full suite of states party obligations.

21 Organization of African Unity (OAU), African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (Banjul

Charter) 27 June 1981, CAB/LEG/67/3 rev 5, 21 ILM 58 (1982) <https://www.refworld.org/

docid/3ae6b3630.html> (last accessed March 2019).

22 African Union, Protocol to the African Charter on Human and People’s Rights on the Rights of Women

in Africa, (Maputo Protocol) 11 July 2003 <https://www.refworld.org/docid/3f4b139d4.

html> (last accessed March 2019).

23 Organization of American States (OAS), American Convention on Human Rights (Pact of San

José), Costa Rica, 22 November 1969 <https://www.refworld.org/docid/3ae6b36510.html>

(last accessed March 2019).

24 Organization of American States (OAS), Inter-American Convention on the Prevention, Punishment

and Eradication of Violence against Women (Convention of Belém do Pará) 9 June

1994 <https://www.refworld.org/docid/3ae6b38b1c.html> (last accessed March 2019).

13

25 Council of Europe, Council of Europe Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence against

Women and Domestic Violence, November 2014, ISBN 978-92-871-7990-6 <https://www.ref-

world.org/docid/548165c94.html> (last accessed March 2019).

26 For example, UN Handbook, above n10; UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), Model

Strategies and Practical Measures for the Elimination of Violence Against Women in the Field

of Crime Prevention and Criminal Justice (1999) <http://www.unodc.org/documents/justice-and-

prison-reform/crimeprevention/Model_Strategies_and_Practical_Measures_on_the_Elimination_

of_Violence_against_Women_in_the_Field_of_CP_and_CJ.pdf> (last accessed March 2019);

Southern Africa Development Community (SADC) Parliamentary Forum, Model Law on Eradicating

Child Marriage and Protecting Children Already in Marriage (2016) <https://www.girlsnotbrides.

org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/MODEL-LAW-ON-ERADICATING-CHILD-MARRIAGE-AND-

PROTECTING-CHILDREN-ALREADY-IN-MARRIAGE.pdf> (last accessed March 2019).

Good Practice in Human Rights Compliant Sexual Offences Laws in the Commonwealth

7. Rape/sexual assault laws

TERMINOLOGY

In this report, we use the term rape/sexual assault when referring

to non-consensual physical assaults of a sexual nature. This includes the

crime of sexual penetration (however slight) that is commonly referred to as

‘rape’, unlawful ‘sexual intercourse’, or ‘carnal knowledge’. Other terms

used elsewhere may include ‘offences against modesty’ or, in the case of

sexual offences against children, the crime of ‘defilement’ (often limited

to girls). It also includes other sexual assault that is not penetrative, such

as ‘indecent assaults’, for example, non-consensual touching of a sexual

nature, or forcing a person to watch a sexual act.

In the majority of jurisdictions in the Commonwealth, there are separate

offences for rape and other forms of sexual assault that do not involve any

penetration. However, a small number of jurisdictions have one offence

of ‘sexual assault’ which contains offences of varying degrees of severity.

In these jurisdictions, rape is one form of sexual assault, e.g., Canada.

27

7.1 The United Nations has called violence against women and girls, which includes

rape and sexual assault:

28

a global pandemic that destroys lives, fractures communities and holds back

development. It is not confined to any region, political system, culture or

social class. It is present at every level of every society in the world. It happens

in peacetime and becomes worse during conflict.

29

7.2 Any person of any age, from infants to the elderly, may find themselves the victim

of rape/sexual assault. However, rape/sexual assault predominantly affects

women and girls. Global estimates by the World Health Organisation (WHO)

indicate that about a third (35%) of women worldwide have experienced

physical violence, including sexual violence, from their partners or other family

members in their lifetime.

30

Certain women and girls face heightened risk of

sexual violence, including First Nations women, LGBT+ women, women who are

homeless, and sex workers. Women (and other people) with disability also face

an increased risk of rape/sexual assault and other forms of violence. Members

of these groups are also less likely to have effective or equal access to justice, to

medical and psychosocial health services, or to other social supports.

31

7.3 Violence against women and girls is a systematic violation of fundamental

human rights and an ongoing form of gender-based discrimination.

32

It is also a

significant social and economic problem everywhere, holding back development

in all sectors,

33

and a serious but preventable public health issue—the WHO has

declared it to be a ‘leading worldwide health problem in every region of the

world’.

34

Its elimination is an explicit Sustainable Development Goal.

35

15

7.4 Men and boys can also be victims of rape/sexual assault. A major oversight

of many sexual offences laws in the Commonwealth is that rape/sexual assault

provisions do not capture male rape. Instead, it must be prosecuted under

‘buggery’ laws or similar, which carry different maximum sentences and different

evidentiary burdens. This type of regime fails to protect people from rape and

sexual abuse equally, regardless of their sex or gender.

Rape myths and the law

7.5 The primary causes of rape/sexual assault and other forms of violence against

women and girls are gender inequality and discrimination, as well as harmful

cultural and social beliefs and practices.

36

While the past half century has seen

significant reforms to rape and sexual assault laws in many countries, others

retain archaic laws that reflect inequality and perpetuate false, discriminatory

and damaging myths about rape and about victims/survivors and perpetrators.

37

These myths cause harm and undermine the criminal justice system. They prevent

or deter people from reporting rape/sexual assault, they expose survivors to re-

traumatisation, they shield perpetrators from justice, and they restrict or prevent

access to justice for victims/survivors.

38

They exist only to blame the victim/

survivor for what has happened, and give excuses to the perpetrator for their

actions and behaviour.

7.6 Some of the most enduring and pervasive rape myths underlying many rape/

sexual assault laws follow:

FIGURE 1: Myths underlying discriminatory rape/sexual assault laws

Women lie about rape

This myth is the basis for the common law ‘fresh-complaint’ doctrine (or the ‘hue

and cry’ rule), as well as the ‘corroboration rule’.

The fresh-complaint doctrine allows a negative inference to be drawn from

evidence that the victim delayed reporting the rape. The rule has its origins in

18

th

century England.

By the beginning of the eighteenth century, a failure to complain immediately [of

sexual assault] had evolved into a presumption of fabrication on the part of the

rape complainant. Since the rule was based on ‘the belief that a rape complainant

could only be believed if she could demonstrate she had publicly denounced the

perpetrator, rape complainants became a special category of witness whose

credibility could be boosted by evidence of recent complaint’.

39

The rule on corroboration, which is an exception to the hearsay rule, requires

a third party to corroborate the complaint of the rape/sexual assault victim/

survivor, who, as a woman, cannot be trusted.

Good Practice in Human Rights Compliant Sexual Offences Laws in the Commonwealth

[…] human experience has shown that in these courts girls and women do sometimes

tell an entirely false story which is very easy to fabricate, but extremely difficult to

refute. Such stories are fabricated for all sorts of reasons, which I need not now

enumerate, and sometimes for no reason at all.

40

The corroboration rule was abolished in the UK by the Privy Council in R v Gilbert [2002],

with the Privy Council deciding that warnings in sexual offences cases are a matter of

discretion for the judge based on the particular facts of the case.

Both common law rules are discriminatory, since they are not applicable in other

criminal cases, and because they assume it is natural for a woman to confide in

someone immediately following a sexual assault. If she fails to do so, the only

rational explanation is that she was lying and that no offence has been committed.

41

‘Chaste’ or ‘nice’ women cannot be raped,

or rape is the victim/survivor’s fault

This is one of the most pervasive rape myths. It is reflected in rules of evidence that,

for example, allow the defence to question the character or reputation of the victim,

including her sexual reputation, allow an inference of consent of the victim to be

drawn from evidence of prior sexual conduct by the victim, from the clothing the

victim was wearing at the time of the attack, her behaviour at the time of the assault,

such as whether she was drunk, or her reaction during and after the assault.

Husbands can’t rape their wives

The ‘marital rape immunity’ is very common in Commonwealth jurisdictions.

It exempts husbands who rape their wives from criminal liability on the false

assumption that wives cannot be raped because they are the property of their

husbands and consented upon marriage to all sexual acts with him. Even where

rape law reform has occurred, some countries, including as recently as 2006, have

chosen to retain this exception in breach of international human rights law.

42

[…] the husband cannot be guilty of a rape committed by himself upon his lawful

wife, for by their mutual consent and contract the wife hath given up herself in this

kind unto her husband which she cannot retract.

43

Much of the scholarship on marital rape immunity attributes the immunity to this

remark in 1736 by the British judge and jurist Sir Matthew Hale. In his view, it was

legally impossible to rape one’s own wife as she had consented to every act of

sex, for all time, as part of her agreement to marry. It was this irrevocable consent

that has been used as justification for immunity for rape in marriage. Unfortunately,

this became part of the common law that the UK exported around the world to its

colonies and remains in use in many countries.

44

It was overturned in English law

in 1992 by the House of Lords in R v R [1992] 1 AC 599.

Only women and girls can be raped

It is still common in the Commonwealth for rape to be conceived in law (and in

common understanding) as a crime that can only be committed by a male against

17

a female. This is reflected in the language used, as well as in the definition of the

crime in many countries, that rape is sexual intercourse or conduct involving only

the penetration of a vagina by a penis. This excludes rape of men and boys, as well

as other forms of sexual assault involving non-consensual/forced penetration of a

sexual nature, such as oral rape or rape with objects.

Rape is always accompanied by violence,

so there will always be visible injuries

People often submit to an unwanted sexual act because they are afraid of being hurt

or killed, the perpetrator threatens someone else, the perpetrator is in a position of

authority or trust, such as a family member, religious leader or teacher, or for many

other reasons. Women may be in an ongoing coercive and controlling environment

with an abusive intimate partner.

Mere submission or acquiescence to the sexual activity is not consent. Consent must

be a free, voluntary, active and ongoing agreement to the sexual activity. There

are no ‘correct’ ways to react to a sexual assault, although there remain many

discriminatory assumptions prevalent in the law and its practice.

Lesbian and bisexual women can be ‘cured’

by having forced sex with a man

In some Commonwealth countries, lesbian and bisexual women are subjected to

rape, often at the hands or under the direction of their own family members, in an

attempt to ‘cure’ their homosexuality in the mistaken belief that it is something that

can be altered, to teach them a lesson that homosexuality is not acceptable, and/

or to control women’s sexuality and maintain gender hierarchies.

7.7 Each of these rape myths, and the many others not listed here, support cultures in

which violence against women and girls, including LGBT+ women and women

with disability, is endemic, and impunity for rape and sexual assault is the norm.

They cause further harm to victims/survivors, their families and ultimately their

communities while failing to protect fundamental rights.

Progress of reforms

7.8 Despite sometimes significant progressive reforms, these and other discriminatory

myths about rape/sexual assault continue to undermine accountability, because

even when they have been explicitly rejected in the law itself, they can

persist in the minds of law enforcement officers, prosecutors, jurors, judges

and magistrates, the public, the media, perpetrators, and victims/survivors

themselves. In recognition of this, there has been a lot of work done developing

policies, operating procedures and training for law enforcement and justice

sector actors (e.g., judges, magistrates, prosecutors, voluntary court support

workers) in relation to sexual violence at the national and regional levels.

45

Good Practice in Human Rights Compliant Sexual Offences Laws in the Commonwealth

FIGURE 2: Examples of positive reforms in the Pacific region

Positive reforms in the Pacific region

Some Commonwealth jurisdictions in the Pacific—for example, Fiji, Papua New

Guinea (PNG) and Solomon Islands—have made significant reforms to their sexual

assault offences in recent years, including removing the marital rape exemption.

46

Important changes have also been made to rules for legal proceedings and

evidence, which has improved court processes for complainants. In particular:

the corroboration rule has been abolished in the Cook Islands, Fiji

and Solomon Islands, and partially abolished in Kiribati;

consent must be proved by the defendant rather than disproved by

the complainant, such as in Fiji;

submission of the complainant does not imply consent;

in some jurisdictions, special court arrangements are made for vulnerable

complainants giving evidence, such as in Solomon Islands and Fiji.

47

(See country case studies on Fiji and the Solomon Islands in Part B of this report.)

Sources for the criteria for good practice:

Rape/sexual assault laws

Over the past two decades, violence against women has come to be

understood as a form of discrimination and a violation of women’s human

rights. Violence against women, and the obligation to enact laws to

address violence against women, is now the subject of a comprehensive

legal and policy framework at the international and regional levels.

48

7.9 The general criteria of equality and non-discrimination set out above are the

foundation for good practice laws on rape/sexual assault. Most countries

guarantee these foundational rights in their national constitutions. At the same

time, international and regional human rights laws elaborate on how these

guarantees are to be implemented at the national level in relation to rape/

sexual assault.

7.10 Reflecting the reality that rape/sexual assault disproportionately affects women

and girls, the obligation on countries to legislate effectively, and to take other

measures to prevent and punish rape/sexual assault in particular, is most often

articulated in international law specifically addressing women’s human rights.

However, the detailed norms they establish apply regardless of the sex or gender

of a victim/survivor. The principal treaties on women’s human rights are:

19

International – CEDAW

7.11 Under Article 3, CEDAW requires states parties to take:

all appropriate measures, including legislation, to ensure the full development

and advancement of women, for the purpose of guaranteeing them the

exercise and enjoyment of human rights and fundamental freedoms on a

basis of equality with men.

7.12 CEDAW does not define violence against women and girls. However, the

CEDAW Committee has confirmed that it constitutes unlawful discrimination

under the treaty, including in its General Recommendation 19 on violence

against women,

49

and General Recommendation 35, which updated General

Recommendation 19.

50

Therefore, states parties to CEDAW have a legal

obligation to prevent and respond to all forms of violence against women,

including sexual violence, and to provide remedies to victims/survivors.

Americas – Convention of Belém do Pará:

7.13 This was the first international treaty directed solely at the elimination of

violence against women. Established by the Organisation of American States,

it sets out the right of women to live a life free of violence, and that violence

against women, including rape, constitutes a violation of their human rights and

fundamental freedoms.

7.14 Articles 1 and 2 define violence against women as ‘any act or conduct, based

on gender, which causes death or physical, sexual or psychological harm or

suffering to women, whether in the public or the private sphere’.

7.15 It contains detailed provisions requiring member states to enact laws, including:

to prevent, punish and eradicate violence against women;

to require the perpetrator to refrain from harassing, intimidating or

threatening the woman or using any method that harms or endangers her

life or integrity, or damages her property;

to amend or repeal existing laws, regulations, legal and customary

practices that sustain the persistence and tolerance of violence against

women;

to establish fair and effective legal procedures for victims/survivors, such

as protective measures, a timely hearing, and effective access to such

procedures; and

to establish the necessary legal and administrative mechanisms to ensure

that women subjected to violence have effective access to restitution,

reparations, or other just and effective remedies.

Good Practice in Human Rights Compliant Sexual Offences Laws in the Commonwealth

Africa – Maputo Protocol:

7.16 The Maputo Protocol seeks to address the human rights violations for which

women and girls are uniquely or disproportionately targeted. It addresses

violence against women in many of its provisions. For example, article 1

defines ‘violence against women’ as including all harmful physical, sexual,

psychological, and economic acts, as well as the ‘imposition of arbitrary

restrictions on or deprivation of fundamental freedoms in private or public life in

peace time and during armed conflict or war’.

7.17 It also requires member states to enact and enforce laws:

to prohibit all forms of violence against women, including unwanted or

forced sex, whether the violence takes place in private or public;

to prevent, punish and eradicate all forms of violence against women;

to provide adequate budgetary and other resources for the implementation

and monitoring of actions aimed at preventing and eradicating violence

against women; and

to specifically address rape and other violence against women seeking

asylum, older women, and women with disability.

Council of Europe – Istanbul Convention:

7.18 This is the most recent treaty on violence against women and girls, established

under the Council of Europe, and is an important benchmark for ‘good practice’

rape laws.

51

7.19 Article 3 defines ‘violence against women’ as ‘a violation of human rights and a

form of discrimination against women’ and includes all harmful acts of physical,

sexual, psychological or economic gender-based violence, including threats

of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in

public or in private.

7.20 It specifies all the areas in which member countries must make and implement

laws on violence against women, including the following:

elements for sexual violence offences:

Article 36 – Sexual violence, including rape

(1) Parties shall take the necessary legislative or other measures to ensure

that the following intentional conducts are criminalised:

(a) engaging in non-consensual vaginal, anal or oral penetration of

a sexual nature of the body of another person with any bodily part

or object;

(b) engaging in other non-consensual acts of a sexual nature with

a person;

(c) causing another person to engage in non-consensual acts of

a sexual nature with a third person.

21

(2) Consent must be given voluntarily as the result of the person’s free will

assessed in the context of the surrounding circumstances.

(3) Parties shall take the necessary legislative or other measures to ensure

that the provisions of paragraph 1 also apply to acts committed against

former or current spouses or partners as recognised by internal law.

excluding culture, custom, religion, tradition or “honour” as justifications

for violence:

Article 42 - Unacceptable justifications for crimes, including crimes committed

in the name of so-called “honour”

(1) Parties shall take the necessary legislative or other measures to ensure

that, in criminal proceedings initiated following the commission of any

of the acts of violence covered by the scope of this Convention, culture,

custom, religion, tradition or so-called “honour” shall not be regarded

as justification for such acts. This covers, in particular, claims that the

victim has transgressed cultural, religious, social or traditional norms or

customs of appropriate behaviour.

criminalising rape (and other violence), regardless of the relationship

between the perpetrator and victim/survivor, including in marriage and

marriage-like relationships:

Article 43 – Application of criminal offences

The offences established in accordance with this Convention shall apply

irrespective of the nature of the relationship between victim and perpetrator.

penalties:

Article 45 – Sanctions and measures

(1) Parties shall take the necessary legislative or other measures to ensure

that the offences established in accordance with this Convention are

punishable by effective, proportionate and dissuasive sanctions, taking

into account their seriousness. These sanctions shall include, where

appropriate, sentences involving the deprivation of liberty which can

give rise to extradition.

Article 46 – Aggravating circumstances

Parties shall take the necessary legislative or other measures to ensure that

the following circumstances, insofar as they do not already form part of

the constituent elements of the offence, may, in conformity with the relevant

provisions of internal law, be taken into consideration as aggravating

circumstances in the determination of the sentence in relation to the offences

established in accordance with this Convention:

(a) the offence was committed against a former or current spouse or

partner as recognised by internal law, by a member of the family, a

person cohabiting with the victim or a person having abused her or

his authority;

Good Practice in Human Rights Compliant Sexual Offences Laws in the Commonwealth

(b) the offence, or related offences, were committed repeatedly;

(c) the offence was committed against a person made vulnerable by

particular circumstances;

(d) the offence was committed against or in the presence of a child;

(e) the offence was committed by two or more people acting together;

(f) the offence was preceded or accompanied by extreme levels of

violence;

(g) the offence was committed with the use or threat of a weapon;

(h) the offence resulted in severe physical or psychological harm for the

victim;

(i) the perpetrator had previously been convicted of offences of

a similar nature.

excluding mandatory mediation or conciliation:

Article 48 – Prohibition of mandatory alternative dispute resolution processes

or sentencing

(1) Parties shall take the necessary legislative or other measures to prohibit

mandatory alternative dispute resolution processes, including mediation

and conciliation, in relation to all forms of violence covered by the scope

of this Convention.

limiting the admissibility of evidence of prior sexual conduct of the victim/

survivor:

Article 54 – Investigations and evidence

Parties shall take the necessary legislative or other measures to ensure that, in

any civil or criminal proceedings, evidence relating to the sexual history and

conduct of the victim shall be permitted only when it is relevant and necessary.

requiring protection of the rights and interests of victims, including their

special needs as witnesses, at all stages of investigations and judicial

proceedings:

Article 56 – Measures of protection

(1) Parties shall take the necessary legislative or other measures to protect the

rights and interests of victims, including their special needs as witnesses,

at all stages of investigations and judicial proceedings, in particular by:

(a) providing for their protection, [and] their families […] from

intimidation, retaliation and repeat victimisation;

(b) ensuring that victims are informed […] when the perpetrator

escapes or is released temporarily or definitively;

(c) informing them […] of their rights and the services at their disposal

and the follow-up given to their complaint, the charges, the general

progress of the investigation or proceedings, and their role therein,

as well as the outcome of their case;

23

(d) enabling victims […] to be heard, to supply evidence and have

their views, needs and concerns presented, directly or through an

intermediary, and considered;

(e) providing victims with appropriate support services so that their

rights and interests are duly presented and taken into account;

(f) ensuring that measures may be adopted to protect the privacy […]

of the victim;

(g) ensuring that contact between victims and perpetrators within court

and law enforcement agency premises is avoided where possible;

(h) providing victims with independent and competent interpreters when

victims are parties to proceedings or when they are supplying evidence;

(i) enabling victims to testify […] without being present or at least

without the presence of the alleged perpetrator, notably through the

use of appropriate communication technologies, where available.

(2) A child victim and child witness of violence against women and domestic

violence shall be afforded, where appropriate, special protection

measures taking into account the best interests of the child.

Asia/Pacic

7.21 Neither Asia nor the Pacific has a regional human rights or women’s human rights

treaty. However, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) has adopted

the Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women in the ASEAN

Region (2004),

52

which does not specifically reference rape/sexual assault but

provides non-binding guidance to ASEAN countries on taking legislative and

other measures to address violence against women and girls in general. ASEAN

countries report back to the annual Leaders’ Meeting on their progress.

7.22 In the Pacific region, the Pacific Leaders Gender Equality Declaration 2012 calls

on countries in the region:

to incorporate CEDAW into national law,

to ‘[e]nact and implement legislation regarding sexual and gender-based

violence to protect women from violence’,

to ‘impose appropriate penalties for perpetrators of violence’, and

to ‘[i]mplement […] essential services (protection, health, counselling,

legal) for women and girls who are survivors of violence’.

53

7.23 In 2017, the 13th Triennial Conference of Pacific Women and 6th Meeting of

Ministers for Women in the Pacific agreed on a new Pacific Platform for Action

on Gender Equality and Women’s Rights (2018–2030).

54

The Pacific Platform

for Action has four pillars, one of which is specifically directed at ensuring

that ‘policies and legislation for the promotion of gender equality and women’s

human rights are adopted and strengthened’. It also adds to the Pacific Leaders

Gender Equality Declaration 2012 by calling on states to address ‘social norms

and dynamics that perpetuate violence against women and girls’.

55

Good Practice in Human Rights Compliant Sexual Offences Laws in the Commonwealth

Other sources

7.24 Other UN and regional human rights treaties also protect against sexual

violence, for example, as unlawful discrimination, or as a violation of the right

not to be subjected to torture or other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment.

These include the ICCPR, CAT, CRC, CRPD, ACHPR, ACHR and, in the context

of armed conflict, the 1949 Geneva Conventions and Additional Protocols.

FIGURE 3: Expert treaty bodies call for reform of sexual offences laws

Expert treaty bodies call for reform of sexual offences laws

The CEDAW Committee has addressed reform of national laws on sexual violence

in many countries, including, for example, confirming that exemptions of spouses

from rape laws, so-called ‘marital rape exemptions’, are inconsistent with states’

legal obligations under CEDAW.

For example, in its concluding observations on Kenya’s 7

th

Periodic Report under

CEDAW in 2011, the Committee urged Kenya to:

give attention, as a priority, to combating violence against women and girls and

adopting comprehensive measures to address such violence, in accordance with

its general recommendation No. 19 […] [and] to expeditiously [reform its Sexual

Offences Act] to criminalise marital rape and other provisions.

56

Kenya reported that this provision would be amended, but no amendment had

been made at the time of writing.

57

How to make a good practice rape/sexual assault law

7.25 As mentioned above in the general discussion on human rights law, commentary

from the UN and regional human rights bodies provides important advice on the

scope and meaning of the rights in the treaties and specific guidance to states on

how to protect and fulfil those rights.

58

For example, the CEDAW Committee has

issued two General Recommendations (GR) on violence against women, GR 19

in 1992 and GR 35 in 2017.

In GR 19, the CEDAW Committee stated that:

Gender-based violence is a form of discrimination that seriously inhibits

women’s ability to enjoy rights and freedoms on a basis of equality with men.

59

7.26 The Committee also defined discrimination as including sexual harm and

other forms of gender-based violence, and advised that gender-based

violence impairs or prevents women from enjoying their human rights and

fundamental freedoms.

60

25

7.27 In GR 35, which updated GR 19, the Committee stated that the prohibition of

gender-based violence against women has evolved into a principle of customary

international law,

61

obliging all countries, whether they have ratified CEDAW

or not, to take all legal and other measures necessary to provide effective

protection of women against gender-based violence, including effective legal

measures and penal sanctions, civil remedies, and compensatory provisions.

7.28 In addressing the legislative measures that states should take, the Committee

said that they should, among other things:

Ensure that sexual assault, including rape is characterised as a crime

against women’s right to personal security and their physical, sexual and

psychological integrity. Ensure that the definition of sexual crimes, including

marital and acquaintance/date rape is based on lack of freely given consent,

and takes account of coercive circumstances. Any time limitations, where

they exist, should prioritise the interests of the victims/survivors and give

consideration to circumstances hindering their capacity to report the violence

suffered to competent services/authorities.

62

7.29 Some UN and regional human rights organisations have taken the treaty-based

and customary international norms, as well as the recommendations, advice

and decisions of the treaty bodies, to provide road maps for legislative reform.

These practical guides describe the specific elements that legislation addressing

violence against women must contain to be effective. Of relevance to this study

is the UN Handbook,

63

which includes detailed elements that a human rights

compliant sexual assault (or rape) law must include. These elements are reflected

in the criteria used in this study.

7.30 At the regional level, the 2017 Guidelines on Combating Sexual Violence and its

Consequences in Africa (the Niamey Guidelines),

64

adopted by the African

Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, is also relevant; as is the Pacific

Island Forum Sexual Offences Model Provisions 2010 (the Pacific Model

Law), which prescribes two distinct categories of laws on sexual offences:

a penetrative offence is described as a sexual violation. Incest is a sexual

violation and will be prosecuted as rape;

a non-penetrative sexual offence is described as sexual assault.

65

7.31 Both regional guidelines draw on the UN Handbook. The African Commission

has urged all member states of the African Union to incorporate the Niamey

Guidelines into their domestic legislation and to ‘ensure their effective and

rapid implementation’.

66

Good Practice in Human Rights Compliant Sexual Offences Laws in the Commonwealth

Criteria for a good practice rape/sexual assault law

7.32 Nine broad criteria for good practice rape/sexual assault laws have been

identified from these international legal sources and guidelines. These represent

baseline standards, covering:

the definition of the crime and its scope;

the definition of consent to sexual conduct;

defences;

penalties; and

rules of procedure and evidence.

7.33 They also include how the crime should be categorised, as well as monitoring

implementation of the law and collecting and publishing data on rape from all

parts of the justice sector. Monitoring and data collection are critical to ensuring

that the law is implemented properly, that government policy related to sexual

violence is targeted and effective, and for transparency, which is critical for

public trust in, and understanding of, legal and judicial systems.

27

FIGURE 4: Criteria for good practice: Rape/sexual assault laws

1. Equality and non-discrimination

a. Inclusive: The definition of every sexual assault crime should not exclude

anyone. This includes rape, sexual assault, indecent assault, specific sexual

offences against children (e.g., defilement and statutory rape offences),

gross indecency, and offences against modesty.

b. Gender-neutral: The crimes should be gender-neutral. Any person,

regardless of sex or gender, age, sexual orientation or gender identity, or

any other characteristic may be the victim/target of rape/sexual assault.

The definitions should not exclude any potential victim/survivor, and all

victims/survivors should have equal protection.

c. No exception for rape/sexual assault in marriage: The law

should clearly state that there is no exception for rape/sexual assault in civil,

customary or religious marriages, or marriage-like relationships. Exemptions

or immunity for rape in marriage are inconsistent with international law

under the ICCPR, CEDAW and CRC.

d. No time limits: Prosecutions for rape/sexual assault should not be statute

barred, regardless of the length of time between the alleged offence and

the reporting of it to police.

2. Definition of the crimes should not exclude any relevant conduct