1

Final Report

NATIONAL INSTITUTES OF HEALTH

Pathways to Prevention Workshop:

The Role of Opioids in the Treatment of Chronic Pain

September 29–30, 2014

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) workshop is co-sponsored by the NIH Office of Disease Prevention (ODP),

the NIH Pain Consortium, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and the National Institute of Neurological

Disorders and Stroke. A multidisciplinary Working Group developed the workshop agenda, and an evidence report

was prepared by an Evidence-based Practice Center through a contract with the Agency for Healthcare Research

and Quality to facilitate the workshop discussion. During the 1½-day workshop, invited experts discussed the body

of evidence, and attendees had opportunities to provide comments during open discussion periods. After weighing

evidence from the evidence report, expert presentations, and public comments, an unbiased, independent panel

prepared this draft report, which identifies research gaps and future research priorities. This draft report was

posted on the ODP website and public comments were accepted for 2 weeks. The final report was then released to

coincide with publication in a peer-review journal.

Introduction

Chronic pain affects an estimated 100 million Americans, or one-third of the U.S. population,

although estimates vary depending upon how pain is defined and assessed. Approximately 25

million people experience moderate to severe chronic pain with significant pain-related activity

limitations and diminished quality of life. In addition to the burden of suffering, pain is the

primary reason Americans are on disability. The societal costs of chronic pain are estimated at

between $560 and $630 billion per year as a result of missed work days and medical expenses.

Although numerous treatments are available for treatment of chronic pain, an estimated 5 to 8

million Americans use opioids for long-term management of chronic pain. Moreover, workshop

speakers presented data from numerous sources that indicate a dramatic increase in opioid

prescriptions and use over the past 20 years. For example, the number of prescriptions for

2

opioids written for pain treatment in 1991 was 76 million; in 2011, this number reached

219 million. This striking increase in opioid prescriptions has paralleled the increase in opioid

overdoses and hospital admissions. In fact, hospital admissions for prescription painkillers have

increased more than fivefold in the last two decades. Yet, evidence also indicates that 40 to 70%

of people with chronic pain are not receiving proper medical treatment, with concerns for both

over- and under-treatment of chronic pain. Together, the prevalence of chronic pain and the

increasing use of opioids have created a “silent epidemic” of distress, disability, and danger to a

large percentage of Americans. The overriding question is whether we, as a nation, are currently

approaching chronic pain in the best possible manner that maximizes effectiveness and

minimizes harm. Several workshop speakers indicated that 80% of all opioid prescriptions

worldwide are written in the United States. This suggests, in part, that other countries have found

different treatments for chronic pain.

On September 29–30, 2014, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) convened a Pathways to

Prevention Workshop: The Role of Opioids in the Treatment of Chronic Pain. Specifically, the

workshop addressed four key questions:

1. What is the long-term effectiveness of opioids?

2. What are the safety and harms of opioids in patients with chronic pain?

3. What are the effects of different opioid management strategies?

4. What is the effectiveness of risk mitigation strategies for opioid treatment?

To answer these questions, the Pacific Northwest Evidence-based Practice Center, under contract

to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, completed a review of the literature related

to these questions. The NIH conducted a 1½-day workshop featuring more than 20 speakers with

3

varied expertise and viewpoints. In addition, audience members expressed many other

experiences and views during the discussion periods.

Context

To understand the dilemma of opioids and chronic pain, the panel felt strongly that an

understanding of underlying contextual factors was crucial. Many workshop presentations

provided information about these contextual factors, including background on the scope of

patient pain and its treatment, the patient’s experience of pain and pain management, the current

public health issues associated with treatment of pain, and the historical context that underlies

the current use and overuse of opioids in the treatment of chronic pain.

As noted in the introduction, pain affects millions of Americans, and the societal costs are high.

For patients, chronic pain is often associated with psychological distress, social disruptions,

disability, and high medical expenses. In addition, with an increase in chronic pain, there has

been a simultaneous rise in opioid use. This use has been associated with pain relief, but also

with an increase in adverse outcomes (e.g., addiction, overdose, insufficient pain relief).

Given the rise in chronic pain syndromes and the poor outcomes associated with opioid

treatment, the panel felt it was fundamental to understand the patient’s perspective. At the

workshop, the panel heard from individuals struggling with chronic pain as well as advocates for

afflicted individuals. The burden of dealing with unremitting pain can be devastating to the

patient’s psychological well-being and can negatively affect a person’s ability to maintain

gainful employment or achieve meaningful advancement professionally. It can affect

relationships with spouses and significant others and may limit engagement with friends and

4

other social activities. The prospect of living a lifetime with pain may induce fear and

demoralization and can lead to diagnoses of anxiety and depression.

Coupled with psychological and social effects are the negative encounters that many individuals

with chronic pain experience with the health care system. Health care providers, often poorly

trained in management of chronic pain, are sometimes quick to label patients as “drug-seeking”

or as “addicts” who overestimate their pain. Some doctors “fire” patients for increasing their

dose or merely for continuing to voice concerns about their pain management. Some patients

have had similarly negative interactions with pharmacists. These experiences may make patients

feel stigmatized, or feel as if others view them as criminals. These experiences may heighten

fears that pain-relieving medications will be “taken away,” leaving the patient in chronic,

disabling pain. In addition, negative perceptions by clinicians can create a rupture in the

therapeutic alliance, which some studies have identified as impeding successful opioid treatment.

For example, cultural factors may influence the treatment a patient receives from health care

providers. White providers tend to underestimate the pain of black patients and perceive them to

be at higher risk than white patients for substance abuse.

Biased media reports on opioids also affect patients. Stories that focus on opioid misuse and

fatalities related to opioid overdose may increase anxiety and fear among some stable, treated

patients that their medications could be tapered or discontinued to “prevent addiction.” For

example, one workshop presentation indicated that a typical news story about opioids was likely

to exclude information about the legitimate prescription use of opioids for pain, focusing instead

on overdose, addiction, and criminal activity.

5

However, the panel also wanted to emphasize what was reflected in numerous presentations at

the workshop: Many patients have been compliant with their prescriptions, and some feel that

their pain is managed adequately to the point of satisfactory quality of life. However, many

patients using opioids long-term continue to have moderate to severe pain and diminished quality

of life. While many physicians feel that opioid treatment can be valuable for some patients,

physicians also feel that patient expectations for pain relief may be unrealistic and that long-term

opioid prescribing can complicate and impair their therapeutic alliance with the patient.

The patient perspective is incredibly important, and yet it is only one aspect of the problem.

Another equally important consideration is how prescription opioids used in the treatment of

chronic pain create public health problems. In other words, although some patients experience

substantial pain relief from prescription opioids and do not suffer adverse effects, these benefits

have to be weighed against problems caused by the vast number of opioids now prescribed.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, there were approximately 17,000

overdose deaths involving opioids in 2011. From 2000 to 2010, the number of admissions for

addiction to prescription opioids increased more than four-fold, to over 160,000 per year.

Different age groups are affected differently. For example, in 2010, one out of eight deaths of

25- to 34-year-olds was opioid-related. There are also collateral deaths from those who have

been prescribed opioids. In a 3-year period (2003 to 2006), more than 9,000 children were

exposed to opioids; this figure is based on data from toxicology centers, and the actual number

may be higher. Of these, nearly all children ingested the opioid (99%), and the ingestion

occurred in the home (92%). A small number of children died (n=8), but 43 children suffered

major effects, and 214 suffered moderate effects. Neonatal narcotic withdrawal also has

6

increased, with an estimated 29,000 infants affected. Both short-term physiological problems as

well as long-term behavioral consequences result from this withdrawal.

There is some concern that opioids are now becoming gateway drugs for heroin use. For

example, one study found that among individuals with a heroin addiction in the 1960s, the most

common first opioid used (the entry drug into heroin) was heroin itself. However, by the year

2000, the most common entry drug to heroin use was a prescription opioid.

Speakers at the workshop expressed almost unanimous concern that physicians are unable to

distinguish among individuals who would use opioids for pain management and not develop

problems with misuse, those who would use them for pain management and then become

addicted, and those who request a prescription because of a primary substance use disorder. Only

a minority of those who use opioids for chronic pain become addicted. For example, in one study

of individuals treated for chronic pain, the addiction prevalence, depending on criteria, ranged

from about 14 to 19%.

Finally, there is a major public health concern that opioids are finding their way illicitly into the

public arena. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s 2013 National

Survey on Drug Use and Health found that, among people age 12 and older abusing analgesics,

53% reported receiving them for free from a friend or relative. Only 23.8% received

prescriptions from one or more doctors.

Another key contextual factor the panel considered was a historical perspective. The panel

identified important historical factors related to approval by the U.S. Food and Drug

Administration (FDA) of opioid medications, introduction of new opioid medications

(particularly extended-release formulations), training of prescribers, and health system changes.

7

Different opioids have undergone varying levels of scrutiny by the FDA. All current, extended-

release opioids have been approved for chronic pain based on 12-week adequate and well-

controlled efficacy studies, although there are safety data for extended-release opioids for a year,

in most cases from open-label studies. A number of immediate-release opioids had been on the

market without prior approval; however, in recent years, all of them have received FDA approval

for acute pain.

The introduction of new opioid drugs on the market over the past decade, particularly those with

extended-release formulations, made them attractive to patients and clinicians who perceived

them as safe and effective. As indicated above, there were limited long-term studies on which to

base clinical decisions. Physicians have little training in how to manage chronic pain patients and

did not have to demonstrate knowledge in how to prescribe these medications.

As described below in “Challenges Within the Health Care System,” changes in the health care

system have provided perverse incentives for clinicians to prescribe opioids in the brief amount

of time they have with patients.

Of course, the historical and current context of opioid use and prescription is complicated by the

heterogeneity of the problem. There are many facets of heterogeneity: patients (e.g., age, gender,

race); the pain etiology (e.g., peripheral vs. central pain), diverse clinical presentations that

include various comorbidities; characteristics of the clinical setting (e.g., providers, payment

structures); and the available opioids for prescription (e.g., differential receptor affinities,

pharmacokinetics, potential for drug interactions).

Given these complexities, the panel struggled with striking a balance between two ethical

principles, beneficence and doing no harm, specifically between the clinically indicated

8

prescribing of opioids on the one hand and the desire to prevent inappropriate prescription abuse

and harmful outcomes on the other. These goals should not be mutually exclusive and, in fact,

approaches that attempt to achieve both goals simultaneously are essential to move the field of

chronic pain management forward. However, one of the central struggles the panel grappled with

in making recommendations is the dearth of empirical evidence to support the four key questions

addressed by the Evidence-based Practice Center (EPC) report. Thus, in order to formulate the

recommendations in this report, the panel synthesized both the evidence from the EPC report and

the workshop presentations that focused on clinical experience as well as on smaller trials and

cohort studies (e.g., non-randomized clinical trials).

Clinical Issues

Patient Assessment and Triage

Chronic pain is a complex clinical issue requiring an individualized, multifaceted approach.

Contributing to the complexity is the fact that chronic pain is not limited to a particular disease

state but rather spans a multitude of conditions, with varied etiologies and presentations. Yet,

traditionally, persons living with chronic pain are “lumped” into a single category, and treatment

approaches have been generalized with little evidence to support this practice. In addition,

although pain is a dynamic phenomenon, waxing and waning and changing in nature over time,

it is often viewed and managed with a static approach. For a number of reasons—including lack

of knowledge, practice settings, resource availability, and reimbursement structure—clinicians

are often ill-prepared to diagnose, appropriately assess, treat, and monitor patients with chronic

pain. Based on the evidence report and the workshop presentations, the panel has identified

several clinical management issues worthy of further discussion.

9

First, there must be recognition that patients’ manifestation of and response to pain is varied,

with genetic, cultural, and psychosocial factors all contributing to this variation. Evidence was

presented that clinicians’ response to patients with pain also differs, often due to preconceived

notions and biases based on racial, ethnic, and other sociodemographic stereotypes. The totality

of the data points to the need for an individualized, patient-centered approach based on a

biopsychosocial model as opposed to the biomedical model that is more commonly employed.

Treating pain and reducing suffering do not always equate, and many times patients and

clinicians have disparate ideas about successful outcomes. A more holistic approach to the

management of chronic pain, inclusive of the patients’ perspectives and desired outcomes,

should be the goal.

Patients, providers, and advocates all agree that there is a subset of patients for whom opioids are

an effective treatment method for their chronic pain, and that limiting or denying access to

opioids for these patients can be harmful. It appears that these patients can be safely monitored

using a structured approach, which includes optimization of opioid therapy, management of

adverse effects, and brief follow-up visits at regular intervals. Therefore, recommendations

regarding the clinical use of opioids should avoid disruptive and potentially harmful changes in

patients currently benefiting from this treatment.

This concept—that some patients benefit while others may receive no benefit or in fact may be

harmed—highlights the current challenges of appropriate patient selection. Data are lacking on

accuracy of and effectiveness of risk prediction instruments for identifying patients at highest

risk for the development of adverse outcomes (e.g., overdose, development of an opioid use

disorder). Yet, longitudinal studies have demonstrated risk factors (e.g., substance use disorders,

other comorbid psychiatric illnesses) that are more likely to be associated with these harmful

10

outcomes, and some studies show that patients who are at high risk are most likely to be

prescribed opioids (and higher doses of opioids). Ideally, patients with these risk factors would

be less likely to receive opioids or more likely to receive them in the context of a maximally

structured approach; however, studies of large clinical databases suggest the opposite.

Although the literature to support use of specific risk assessment tools is insufficient, the

consensus appears to be that the approach to the management of chronic pain should be

individualized, based on a comprehensive clinical assessment that is conducted with dignity and

respect and without value judgments or stigmatization of the patient. Based on the workshop

presentations, this initial evaluation would include an appraisal of pain intensity, functional

status, and quality of life, as well as an assessment of known risk factors for potential harm,

including history of substance use disorders and current substance use; presence of mood, stress,

or anxiety disorders; medical comorbidity; and concurrent use of medications with potential

drug-drug interactions. Additionally, there may be a role for the redesign of the electronic health

record to facilitate such an assessment, including integration of meaningful use criteria to

increase its adoption. Finally, incorporating the use of other clinical tools (e.g., prescription drug

monitoring programs) into this assessment, although not well studied, seems to be widely

supported. These factors also can be used to tailor the clinical approach, triaging those screening

at highest risk for harm to more structured and higher intensity monitoring approaches.

Treatment Options

Despite what is commonly done in current clinical practice, there appear to be few data to

support the long-term use of opioids for chronic pain management. Several workshop speakers

stressed the need to use treatment options that include a range of progressive approaches that

11

might initially include nonpharmacological options, such as physical therapy, behavioral therapy,

and/or proven complementary and alternative medicine approaches with demonstrated efficacy,

followed by pharmacological options, including non-opioid pharmacotherapies. The use of and

progression through these treatment modalities would be guided by the patient’s underlying

disease state, pain, and risk profile as well as clinical and functional status and progress.

However, according to a workshop speaker, lack of knowledge or limited availability of these

nonpharmacological modalities and the ready availability of pharmacological options and

associated reimbursement structure appear to steer clinicians towards the use of pharmacological

treatment and, more specifically, opioids.

One area of clinical importance the panel reviewed was the notion that pain type could influence

pain management. Data were presented on three distinct pain mechanisms: (1) peripheral

nociceptive—caused by tissue damage or inflammation, (2) peripheral neuropathic—damage or

dysfunction of peripheral nerves, and (3) centralized—characterized by a disturbance in the

processing of pain by the brain and spinal cord. Individuals with more peripheral/nociceptive

types of pain (e.g., acute pain due to injury, rheumatoid arthritis, cancer pain) may respond better

to opioid analgesics. In contrast, those with central pain syndromes—exemplified by

fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome, temporal-mandibular joint disease and tension

headache—do not respond as well to opioids, as to centrally acting neuroactive compounds

(e.g., certain antidepressant medications, anticonvulsants). In particular, there is strong evidence

for non-opioid interventions in treatment of fibromyalgia, one of the most common conditions

presenting in primary care and pain clinics. In fact, the workshop presented interesting

preliminary evidence that if an initial evaluation for pain demonstrated even a few signs of

fibromyalgia (not meeting criteria for the full syndrome), the patient was at risk for poor

12

response to opioids and a worse long-term course of pain. In addition, speakers presented

evidence that nearly all chronic pain may have a centralized component, and it was suggested

that opioids may promote progression from acute nociceptive pain to chronic centralized pain.

However, several speakers and audience members cautioned against making blanket statements

about who is or is not likely to benefit from opioids, again highlighting the importance of

individualized patient assessment and management. The health care system would benefit from

additional research on these different mechanisms of pain and the optimal approaches for each,

including the value of individualized versus general approaches; identifying risk factors for

patients most likely to develop chronic pain after an acute or subacute pain syndrome, and ways

to mitigate or reduce the risk of transitioning to a chronic pain syndrome.

Clinical Management

There is little evidence to guide clinicians once they have made the decision to initiate opioids

for chronic pain therapy. Data on selection of specific agents based on opioid characteristics,

dosing strategies, and titration or tapering of opioids are insufficient to guide current clinical

practice. Discussed during the workshop was the concept of opioid rotation, in which a clinician

transitions a patient from an existing opioid regimen to another with the goal of improving

therapeutic outcomes. However, this approach has not been formally evaluated. The use of

equianalgesic tables (opioid conversion tables), which provide a list of equianalgesic doses of

various opioids to guide clinicians in determining doses for converting from one opioid to

another, was an issue of particular concern. The equianalgesic dose is a construct based on

estimates of relative opioid potency. A multitude of these opioid conversion tables are available

in both the peer-reviewed and non-peer-reviewed literature, and speakers noted the lack of

consistency between the tables. Many of the studies to determine these equianalgesic doses were

13

conducted in a sample of the study population and using data points that may not generalize to

patients presenting with chronic pain. The FDA has begun including data obtained from drug

trials and post-marketing studies in package inserts to aid clinicians in switching between

opioids, but it appears that many clinicians and pharmacists are not aware of this. Furthermore,

although three known classes of opioid receptors—mu (μ), kappa (κ), and delta (Δ)—have been

identified, multiple receptor subtypes within each of these classes can alter the effect of opioids

based on receptor subtype binding. This led to a discussion between workshop speakers of the

concept of incomplete cross-tolerance, in which providers may need to reduce the dose by 25 to

30% when converting between one opioid and another. Because of its longer half-life,

methadone may require a larger reduction (up to 90%); in fact, some speakers argued that

methadone should be excluded from these tables and suggested that the use of these tables may

have led to harm and should not be broadly used. There was a call for the development of

validated and patient-specific types of equianalgesic tables. It was also noted that the majority of

clinicians receive little to no education on use of these tables and on converting from one opioid

regimen to another; this should be a focus of future clinical education and clinical decision

support efforts.

Determination and Assessment of Outcomes

Several workshop speakers noted that patient assessments should be ongoing, including both

positive and negative outcomes. The range of items on such assessments might include pain

intensity and pain frequency, using both a short time reference as well as a longer timeframe for

comparative purposes, functional status including impact on functions of daily living; quality of

life; depression; anxiety; potential misuse or abuse of opioid medications; potential adverse

medical effects of opioids; and other measures that mimic those items obtained during the initial

14

clinical risk profiling. These frequent reassessments should guide maintenance or modification of

the current treatment regimen, and patients who are failing to meet the mutually agreed upon

clinical outcomes should be considered for discontinuation of opioid therapy. Although there

appeared to be consensus among speakers on the need for an “exit strategy,” there was less

consensus and very few data on how one should be implemented.

Adverse Events and Side Effects

In addition to the very real risk of development of an opioid use disorder, chronic administration

of opioids are associated with other adverse effects, including increased risk of falls and

fractures, hypogonadism with resultant sexual dysfunction, and, in at least two studies, increased

risk of myocardial infarction. These factors are important to the discussion of risks versus

benefits with patients, and realistic expectations regarding adverse events and side effects from

various treatment options may need to be explained to patients as well as relatives and home care

providers. New patient communication options may be of value for the patients or relatives to

discuss evolving concerns. Adverse events and side effects might be monitored regularly and

reported to the clinician between regularly scheduled visits using web or other communication

channels.

Risk Mitigation Strategies

As with much of the other data on opioid use for chronic pain, data are limited on the efficacy of

various risk mitigation strategies, including patient agreements, urine drug screening, and pill

counts. Some speakers expressed concern as to the effectiveness of patient agreements as few

data are available to support their use. However, the use of patient agreements and other care

support mechanisms might be an option as part of a comprehensive care management plan and

15

might be reinforced without the use of judgmental perspectives that could impact the relationship

between patient and provider. Naloxone, which traditionally has been used to reverse heroin

overdose, was highlighted as a potential risk mitigation strategy for patients who are prescribed

opioids for chronic pain. Guided by the premise that these are risky drugs as opposed to risky

patients, a workshop speaker suggested that naloxone might be provided to patients at the same

time as the original prescription for the opioid and that this might provide an opportunity for

additional patient education. Other speakers were more cautious about using this strategy for all

patients, yet were willing to consider that it might be explored from an individual patient risk-

benefit perspective.

Reducing the Next Generation of Chronic Opioid Users

Speakers stated that a multidisciplinary team approach that emulates the functions of a

multidisciplinary pain clinic would be desirable, given the prior history of success of such

models in treating the whole person and not merely the pain condition, which may not be a

simple, single entity. As noted above, different types of pain—peripheral nocioceptive,

peripheral neuropathic, and centralized pain—appear to have different profiles of response to

such treatments. Furthermore, the use of a more effective chronic disease care model may have

implications for reducing the potential of a new generation of chronic opioid users as the

continued first-line use of opioids for chronic pain treatment is generally suboptimal and has the

potential for addiction. Although the team composition may vary, members might include the

primary care provider, case or care managers, nurses, pharmacists, psychologists, psychiatrists,

social workers, and other pain specialists. However, the current health care financial incentives

do not appear to bode well for the re-initiation of such an approach (see below for a more

detailed discussion of this point). Finally, one simple approach the panel considered to decrease

16

the conversion of acute users to chronic users was to advise those prescribing opioid medications

for the treatment of acute pain (e.g., in the post-operative setting or for an injury) to prescribe

fewer pills to be taken over a shorter but clinically reasonable timeframe, as there is some

evidence that higher numbers of pills initially prescribed is related to risk of chronicity of use.

Challenges Within the Health Care System

A major influence on opioid prescribing is the evolution of the larger health care system and the

current state of primary care. The panel heard reports of major problems with the current health

care system, including:

Poor support for team-based care and specialty pain clinics

Over-burdened primary care providers

A lack of knowledge and decision support for chronic pain management

Financial misalignment favoring the use of medications

Fragmentation of care across different providers.

Pain is a multidimensional problem ranging from discomfort to agony and affecting physical,

emotional, and cognitive function as well as interpersonal relationships and social roles. As with

other chronic conditions, chronic pain management requires a more comprehensive

biopsychosocial model of care. Therefore, best practice models for chronic pain management

require a multidisciplinary approach similar to that recommended for other chronic complex

illnesses such as depression, dementia, eating disorders, or diabetes. Research demonstrates that

these conditions can be managed successfully using an interdisciplinary team-based approach to

care (e.g., medicine, psychology, nursing, pharmacy, social work). Early efforts to manage pain

in the late 20th century were based on similar effective models of interdisciplinary,

17

comprehensive, and individualized care. Unfortunately, as health care systems evolved and

increasingly implemented and maintained only those interventions that were declared to be

revenue-generating, team-based approaches to care for pain were largely abandoned.

Instead, management of chronic pain has been largely relegated to the primary care providers

working in health systems not designed or equipped for chronic pain management. Moreover,

expectations for primary care providers increasingly evolved towards productivity-based metrics,

with more tasks expected to be completed within a 10- to 20-minute office visit. Primary care

providers often face competing clinical priorities in patients with chronic pain because these

patients often have multi-morbidity and polypharmacy. Administrative responsibilities also

compete for the provider’s time. For example, growing requirements for documentation in the

electronic health record are consuming a larger portion of the office visit. Hence, time-

consuming but important clinical tasks—such as conducting multidimensional assessments,

developing personalized care plans, and counseling—have given way to care processes that can

be accomplished more quickly and with fewer resources, such as prescription writing and

referrals. In the case of pain management, which often takes substantial face-to-face time,

quicker alternatives have become the default option. As a result, providers often prescribe

opioids for pain even when, for any given patient, the pain might be treated more safely and

effectively with other modalities.

Primary care providers are charged with relieving pain as a professional obligation and a

fundamental goal of health care. However, these providers have often received little specific

training in chronic pain management or in the use and management of opioids. This may be

particularly true for those providers who were trained before newer formulations of opioids or

other alternatives were available. As the systematic review clearly reveals, these providers do not

18

have access to evidence-based dosing schedules, adjustment and switching rules, or tapering and

stopping rules to guide pain management. Even if primary care providers had the requisite

knowledge, skill, and intent, they often do not have access to the resources needed to manage

pain according to current guidelines. This is often true because alternative first-line treatment

strategies are not available. For example, most practices do not have access to experts in pain

management, including specialty pain clinics, or access to the alternative approaches to pain

management (e.g., physical therapy, cognitive and behavioral approaches, acupuncture, yoga,

meditation, other complementary and alternative medicine). Therefore, clinicians provide a

prescription for opioids because they and their patients feel it is the only or the most expedient

alternative. Once the decision to initiate opioids has been made, patients and providers lack

practical tools to monitor the outcomes of chronic pain management. For example, simple

monitoring tools (e.g., the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 for depression) assist in the diagnosis

and management of depression. Although widely available, pain rating scales alone are not

comprehensive enough to measure the adequacy of pain control on important dimensions such as

quality of life, function, and employment.

Payment structures and incentives also represent an important system-level facilitator for

excessive opioid use. Fee-for-service payment traditionally has not focused on the outcomes of

care valued by patients, but rather on the processes of medical care. Current reimbursement for

evaluation and management may be inadequate to reflect the time and team-based approaches

needed for integrative treatment. In some instances, payment structures place barriers to non-

opioid therapy, such as formulary restrictions that require evidence of failure of multiple

therapies before covering non-opioid alternatives (e.g., pregabalin). Other payment structures,

such as tiered coverage systems, keep non-opioid alternatives as second- or third-line options

19

rather than placing them more appropriately as first-line therapy. Other incentives encourage

prescribing opioids for several months at a time rather than for a shorter term or using lower-

volume prescriptions, because providers are instructed that patient and administrative costs are

lower, and that convenience is improved with longer-duration and larger-volume prescriptions.

The panel heard reports that this apparently benign incentive actually may lead to an increased

risk of opioid dependence or other adverse events, including harm through nonmedical uses.

Moreover, current reimbursement policies do not provide payment for some of the health

professionals who are needed to provide best-practice pain management (e.g., pharmacists, care

coordinators) and others may be reimbursed insufficiently (e.g., for only a single visit). In health

systems that are primarily fee-for-services, there may be incentives to generate short-term

revenue, whereas in capitated systems, where physicians receive a set amount for each enrolled

person per given period of time, there may be greater incentive to invest in upfront resources

(e.g., team-based care) if they can prevent downstream utilization (e.g., hospitalization). Given

the current vagaries of payment structures, perhaps it is not surprising that providers and patients

chose opioids more often than is clinically appropriate and more often than guidelines suggest.

Finally, fragmentation of care across multiple providers and sites of care often leads to patients

receiving prescriptions from multiple providers. This may lead not only to inappropriate

prescribing of opioids but also to inappropriate prescribing of unsafe combinations of drugs such

as opioids and benzodiazepines. Up to 25% of patients who have chronic pain receive their

medications in the emergency department, often effectively bypassing the primary care system.

Patients with chronic pain may see multiple specialists with relevant expertise in chronic pain

(e.g., neurologists, orthopedists, rheumatologists, psychiatrists), but these specialists may often

prescribe opioids without the knowledge of primary care providers. The specialists may focus on

20

pain in isolation and may not recognize or consider the patient’s comorbid conditions,

concomitant medications, or goals of care. Patients may actively “shop” for providers (within or

across health care systems or state lines) to find a provider who is willing to prescribe opioids.

The panel heard recommendations that there is a clear need to address these system-level

problems. Chief among these recommendations is the need to develop, evaluate, and implement

new models of care for chronic pain management. To accomplish this fundamental goal, research

must address health care aims and thus assess the costs and benefits to individuals and

populations. Moving to team-based care is unlikely to happen without restructuring

reimbursement systems, building patient-centered clinical information systems, expanding the

roles and responsibilities of health care professionals beyond the physician, and conducting new

basic research on which patients require which care in which settings.

Methods and Measurement

Reliable and valid clinical and research methods are essential as the medical field seeks to

understand best practices for chronic pain management. The EPC report found few long-term

(more than 1 year) studies of opioid treatment, and those identified in the literature were

typically of poor quality (see Summary of Findings Table). It is particularly difficult to

extrapolate from studies examining the effects of opioids on acute pain to chronic pain. The

panel identified methodological problems related to definitions, measurement, and research

design.

Definitions. One of the central definitional problems is defining acute versus chronic pain.

Various durations are used to define chronic pain, including “lasting more than 3 months” or

“lasting more than 6 months” or a time-based definition that is somewhat arbitrary. For example,

21

the American Academy of Pain Medicine suggests that chronic pain is best defined as pain that

does not remit in the expected amount of time. This is clearly an individualized pain assessment

and, although it may be useful to the individual clinician, does not provide a standard definition

that could be used for research purposes. The panel suggested that detectable changes in brain

function occur as pain moves from acute to chronic states; however, although this may provide a

more precise, functional definition of pain, it is unrealistic to expect that most research will

incorporate neuroimaging modalities.

Unclear definitions also impair the understanding of the types of pain that patients experience.

Many research studies compare patients with cancer-derived and non-cancer-derived pain. This

dichotomy is clearly insufficient, as neither cancer pain nor non-cancer pain are homogeneous, in

large part because individual differences in sensory processing and augmented pain affect

perception and reporting of pain. In other words, chronic pain is heterogeneous and complex. As

mentioned previously, one workshop presentation classified pain by its source: peripheral

(nociceptive) pain, peripheral (non-nociceptive) pain, and centralized. Although this rubric may

be useful for considerations of acute pain, chronic pain should not be partitioned into mutually

exclusive, discrete categories. This definitional problem affects diagnosis, treatment, and drug

regulation.

Finally, definitions are important when considering how to measure outcomes. Pain relief is a

major focus of treatment and research. However, it is difficult to quantify pain. The typically

used 0–10 pain scale provides an overall sense of pain, but not an assessment of individual

components related to pain. For example, recent work on the concept of “fibromyalgianess” (the

tendency to respond to illness and psychosocial stress with fatigue, widespread pain, general

increase in symptoms, and similar factors) identifies at least three components to chronic pain

22

that are important to measure: chronic pain or irritation in specific body regions, somatic

symptoms (e.g., fatigue, sleep, mood, memory), and sensitivity to sensory stimuli.

Measurement. Research also suffers from significant measurement problems. Risk screening

instruments would help clinicians implement better risk management strategies. Many speakers

at the workshop indicated that the field does not have good risk assessment tools. The EPC

report found that standardized tools lacked sufficient sensitivity and specificity to make them

clinically useful. In large part, the problem with screening is that it is not clear what risk factors

should be measured or whether it is feasible or sensible to screen for risk. Some speakers

indicated that clinicians should assume that all patients are at risk and not use valuable resources

(including clinician time) to screen.

Finally, patient outcomes (typically measured in an ongoing manner) are important. Numerous

speakers indicated that the primary goal for researchers and clinicians may be the reduction in

patient pain; however, patients may be more interested in improving quality of life, rather than

absolute pain reduction. Functional behavior related to pain also needs to be assessed.

The most important aspect of measuring patient outcomes is to acknowledge that they are

determined by multiple factors and therefore will need to be multidimensional in scope. Key

components of a thorough assessment of patient outcomes would include measures of pain,

psychopathology, quality of life, social factors (e.g., days worked), safety, and adverse outcomes.

Research Design. The panel reviewed several presentations related to study design. Based on

the EPC report, there is a clear need for well-designed longitudinal studies of effectiveness and

safety of long-term opioid use in the management of chronic pain; this is an immediate concern.

Such studies—both because of their length and the heterogeneity of factors to be accounted for—

23

would need to be large and would therefore be expensive. In addition, it is not clear from a

practical standpoint that patients with chronic pain would be willing to be randomized to

placebo, nonpharmacological treatments, or non-opioid medications. The workshop speakers

also proposed an alternative design, which involved accepting patients on long-term treatment

into a study and randomizing them to maintenance versus tapering of the opioid. However,

speakers noted similar practical issues around recruitment of individuals willing to have their

medication tapered. Pragmatic designs (with some flexibility in the treatments used) could help

bypass some of the challenges with conducting long-term randomized control trials.

With these limitations, workshop speakers suggested other types of longitudinal studies; for

example, an approach using a small cohort study was seen as a more feasible option. Also from a

feasibility standpoint, the use of the electronic health record to track pain and markers of

improvement as well as adverse outcomes and side effects may provide the best data on large

populations. In addition, some speakers noted limitations of FDA-mandated post-marketing

surveillance studies by pharmaceutical companies, but also saw this as an opportunity to gain

valuable information in this area.

Another design issue considered by the panel related to how best to account for heterogeneity

across patients, medications, and outcomes. Novel design and statistical approaches may be

needed to manage this complexity. For example, ecological designs that embrace heterogeneity

and help to understand diversity among patients and to identify key subgroups that may respond

differently to various treatments should be considered. This methodology often incorporates

novel statistical methods (e.g., latent class and profile analyses).

24

The panel also noted several specific research issues that merit further exploration. These include

the following:

1. Better understanding is needed of the window between effective dose and dose at which

side effects and adverse outcomes occur. These may include studies on how this window

is defined and assessed as well as the drug-related, genetic, and other patient-related

factors that might affect the targeted dose range.

2. In adverse outcomes research, it is important to determine how best to model more

immediate versus longer-term side effects based on the length of exposure to opioids. The

notion was presented that some poor outcomes (e.g., falls) might occur soon after

initiation of treatment, whereas others (e.g., hypogonadism) might be more associated

with longer-term exposure. Future studies will need to encompass this time-varying

aspect of certain adverse effects and poor outcomes.

3. Few studies have looked at genetic predictors of response and poor outcomes. There are

several promising areas and specific loci for genetic research in this area, including a

panel of gene variants related to cytochrome P450 metabolism (e.g., examining outcomes

in people who are slow, intermediate, or fast drug metabolizers), receptor target single

nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) as well as SNPs related to indirect modulation

(e.g., COMT, the gene coding for catechol-O-mehtyltransferase), the drug transporter

(e.g., ABCB1), and other polymorphisms derived from genome-wide association studies

(e.g., rs2952768).

Incorporation of biological approaches will be important to gaining a better understanding of the

etiology of chronic pain and the mechanisms involved in opiate response and poor outcomes.

25

Greater incorporation of functional imaging studies of pain, as well as clinical neuroscience

findings about salient psychological factors, hold promise for identifying patients who would

best respond to opioids versus other pharmacological or nonpharmacological modalities. Finally,

future studies might examine the utility of variables such as evoked pain sensitivity and

endogenous opioid activity.

Implementation science may be useful to address some of the clinical and practice issues. For

example, research on how to bring prescription monitoring systems into an electronic health

record may be particularly important. Finding ways to incorporate pharmacists and nurses in care

groups is also essential. A final example includes research into the cost-effectiveness of chronic

pain management teams, particularly given potential incentives for providing high quality of care

(e.g., pay for performance).

Complementary Efforts

As the medical community looks for ways to increase available options to control pain and

suffering, many complementary groups are at work. A 2011 report by the Institute of Medicine,

Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and

Research, has sparked efforts from various agencies to partner in addressing this issue.

The NIH Pain Consortium has selected 12 health professional schools as Centers of Excellence

in Pain Education (CoEPEs). The CoEPEs will act as hubs for the development, evaluation, and

distribution of pain management curriculum resources for medical, dental, nursing, and

pharmacy schools to enhance and improve how health care professionals are taught about pain

and its treatment.

26

The Stanford-NIH Pain Registry, now called the National Collaborative Health Outcomes

Information Registry (CHOIR) system, provides clinicians with valuable information regarding

treatment outcomes. This platform collects outcome data on large numbers of patients suffering

from chronic pain.

The Interagency Pain Research Coordinating Committee is a federal advisory committee charged

with coordination of all pain research efforts across all federal agencies. The ultimate goal of the

committee is to advance the fundamental understanding of pain and to improve pain-related

treatment strategies.

The FDA has recognized that extended-release and long-acting opioids are associated with

serious risks. The FDA is now requiring additional studies and clinical trials to assess these risks,

which include misuse, abuse, hyperalgesia, addiction, overdose, and death.

Many professional societies have taken a stance on the use of opioids for chronic pain. The

American Academy of Neurology recently published a position paper on non-cancer pain.

Initiatives such as the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation’s “Choosing Wisely”

are underway.

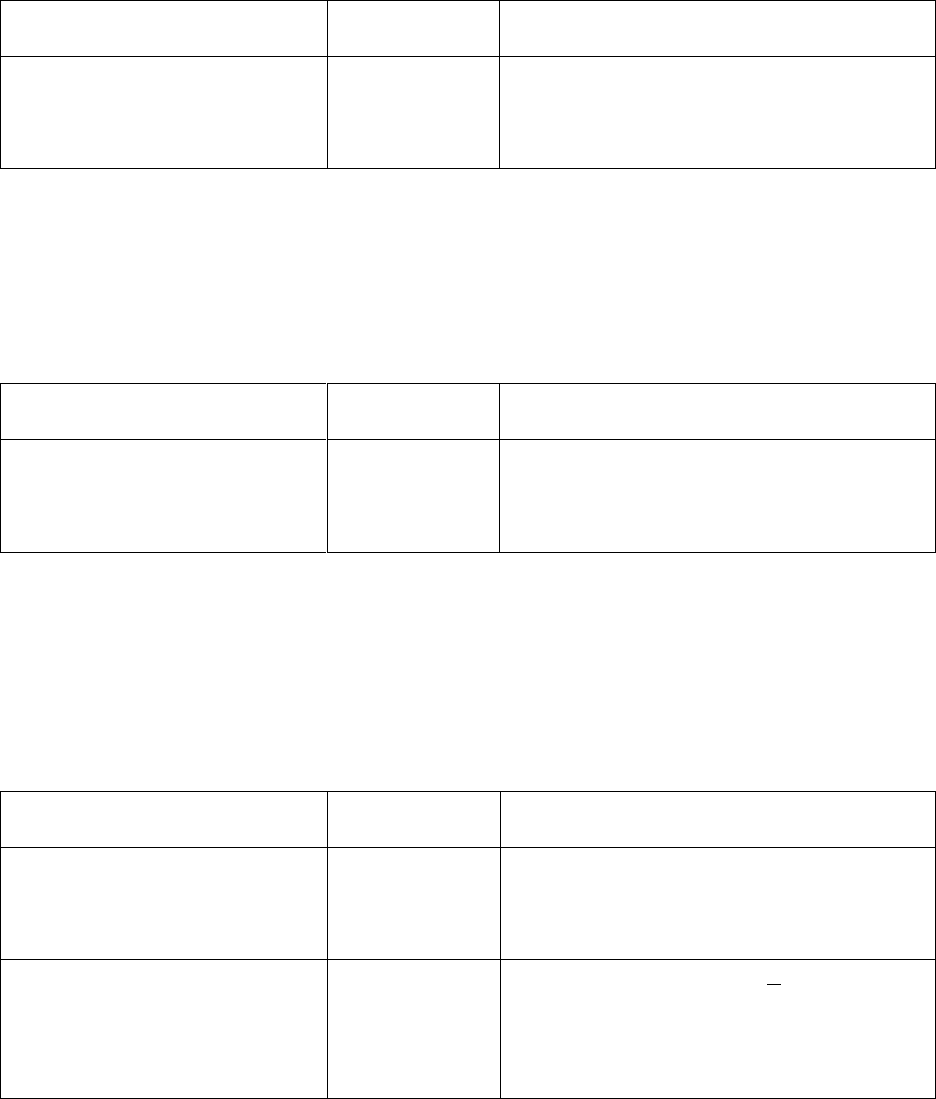

Summary of EPC Report Findings

1. Effectiveness and comparative effectiveness

a. In patients with chronic pain, what is the effectiveness of long-term opioid therapy for long-

term (>1 year) outcomes related to pain, function, and quality of life?

27

Key Question

Strength of

Evidence

Conclusion

Pain, function, quality of life

Insufficient

No study of opioid therapy versus placebo

or no opioid therapy evaluated long-term

(>1 year) outcomes related to pain,

function, or quality of

life.

2. Harms and adverse events

a. In patients with chronic pain, what are the risks of opioids versus placebo or no opioid on

(1) opioid abuse, addiction, and related outcomes; (2) overdose; and (3) other harms?

Key Question

Strength of

Evidence

Conclusion

Abuse, addiction

Low

No randomized trial was evaluated. One

retrospective cohort study found prescribed

long-term opioid use was associated with

significantly increased risk of abuse or

dependence versus no opioid use.

Abuse, addiction

Insufficient

In 10 uncontrolled studies, estimates of

opioid abuse, addiction, and related

outcomes varied substantially even after

stratification by clinic

setting.

Overdose

Low

Current opioid use was associated with

increased risk of any overdose events

(adjusted HR 5.2, 95% CI 2.1 to 12) and

serious overdose events (adjusted HR 8.4,

95% CI 2.5 to 28) versus current nonuse.

Fractures

Low

Opioid use was associated with increased

risk of fracture in one cohort study

(adjusted HR 1.28, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.64)

and one case-control study (adjusted OR

1.27, 95% CI 1.21 to 1.33).

Myocardial infarction

Low

Current opioid use was associated with

increased risk of myocardial infarction

versus nonuse (adjusted OR 1.28, 95% CI

1.19 to 1.37 and incidence rate ratio 2.66,

95% CI 2.30 to 3.08).

Endocrine

Low

Long-term opioid use was associated with

increased risk of use of medications for

erectile dysfunction or testosterone

replacement versus nonuse (adjusted OR

1.5, 95% CI 1.1 to 1.9).

28

b. How do harms vary depending on the dose of opioids used?

Key Question

Strength of

Evidence

Conclusion

Abuse, addiction

Low

One retrospective cohort study found

higher doses of long-term opioid therapy

associated with increased risk of opioid

abuse or dependence than lower doses.

Compared to no opioid prescription, the

adjusted odds ratios were 15 (95% CI 10 to

21) for 1-36 MED/day, 29 (95% CI 20 to

41) for 36-120 MED/day, and 122 (95%

CI 73 to 205) for ≥120 MED/day.

Overdose

Low

Versus 1 to 19 mg MED/day, one cohort

study found an adjusted HR for an

overdose event of 1.44 (95% CI 0.57 to

3.62) for 20 to 49 mg MED/day and 11.18

(95% CI 4.80 to 26.03) at >100 mg

MED/day; one case-control study found an

adjusted OR for an opioid-related death of

1.32 (95% CI 0.94 to 1.84) for 20 to 49 mg

MED/day and 2.88 (95% CI 1.79 to 4.63)

at ≥200 mg MED/day.

Fracture

Low

Risk of fracture increased from an adjusted

HR of 1.20 (95% CI 0.92 to 1.56) at 1 to

<20 mg MED/day to 2.00 (95% CI 1.24 to

3.24) at ≥50 mg MED/day; the trend was

of borderline statistical significance.

Myocardial infarction

Low

Relative to a cumulative dose of 0 to 1350

mg MED over 90 days, the incidence rate

ratio for myocardial infarction for 1350 to

<2700 mg was 1.21 (95% CI 1.02 to 1.45),

for 2700 to <8100 mg was 1.42 (95% CI

1.21 to 1.67), for 8100 to <18,000 mg was

1.89 (95% CI 1.54 to 2.33), and for

>18,000 mg was 1.73 (95% CI 1.32 to

2.26).

Motor vehicle accidents

Low

No association was found between opioid

dose and risk of motor vehicle accidents.

Endocrine

Low

Relative to 0 to <20 mg MED/day, the

adjusted OR for daily opioid dose of ≥120

mg MED/day for use of medications for

erectile dysfunction or testosterone

replacement was 1.6 (95% CI 1.0 to 2.4).

29

3. Dosing strategies

a. In patients with chronic pain, what is the comparative effectiveness of different methods for

initiating and titrating opioids for outcomes and risk?

Key Question

Strength of

Evidence

Conclusion

Pain

Insufficient

Evidence from three trials on effects of

titration with immediate-release versus

sustained-release opioids reported

inconsistent results on outcomes related to

pain.

c. In patients with chronic pain, what is the comparative effectiveness of different long-acting

opioids on outcomes related to pain, function, and quality of life as well as the risk of overdose,

addiction, abuse, or misuse?

Key Question

Strength of

Evidence

Conclusion

Pain and function

Low

No difference was found between various

long-acting opioids.

Assessment of risk of overdose,

addiction, abuse, or misuse

Insufficient

No studies were designed to assess risk of

overdose, addiction, abuse, or misuse.

Overdose (as indicated by all-

cause mortality)

Low

One cohort study found methadone to be

associated with lower all-cause mortality

risk than sustained-release morphine in a

propensity-

adjusted analysis.

Abuse and related outcomes

Insufficient

One cohort study found some differences

between long-acting opioids in rates of

adverse outcomes related to abuse, but

outcomes were nonspecific for opioid-

related adverse events, precluding reliable

conclusions.

30

f. In patients with chronic pain on long-term opioid therapy, what is the comparative

effectiveness of dose escalation versus dose maintenance or use of dose thresholds on outcomes

related to pain, function, and quality of life?

Key Question

Strength of

Evidence

Conclusion

Pain, function, withdrawal due

to opioid misuse

Low

No difference was found between more

liberal dose escalation versus maintenance

of current doses in pain, function, or risk of

withdrawal due to opioid misuse, but there

was limited separation in opioid doses

between groups (52 vs. 40 mg MED/day at

the end of the trial).

h. In patients on long-term opioid therapy, what is the comparative effectiveness of different

strategies for treating acute exacerbations of chronic pain on outcomes related to pain, function,

and quality of life?

Key Question

Strength of

Evidence

Conclusion

Pain

Moderate

Two randomized trials found buccal

fentanyl more effective than placebo for

treating acute exacerbations of pain, and

three randomized trials found buccal

fentanyl or intranasal fentanyl more

effective than oral opioids for treating

acute exacerbations of pain in patients on

long-term opioid therapy.

31

i. In patients on long-term opioid therapy, what are the effects of decreasing opioid doses or

tapering off opioids versus continuation of opioids on outcomes related to pain, function, quality

of life, and withdrawal?

Key Question

Strength of

Evidence

Conclusion

Pain, function

Insufficient

Abrupt cessation of morphine was

associated with increased pain and

decreased function

compared to

continuation of morphine.

j. In patients on long-term opioid therapy, what is the comparative effectiveness of different

tapering protocols and strategies on measures related to pain, function, quality of life, withdrawal

symptoms, and likelihood of opioid cessation?

Key Question

Strength of

Evidence

Conclusion

Opioid abstinence

Insufficient

No clear differences were found between

different methods for opioid

discontinuation or tapering in likelihood

of

opioid abstinence after 3 to 6 months.

4. Risk assessment and risk mitigation strategies

a. In patients with chronic pain being considered for long-term opioid therapy, what is the

accuracy of instruments for predicting risk of

opioid overdose, addiction, abuse, or misuse?

Key Question

Strength of

Evidence

Conclusion

Diagnostic accuracy: Opioid

Risk Tool

Insufficient

Based on a cutoff of >4, three studies (all

poor quality) reported very inconsistent

estimates of diagnostic accuracy,

precluding reliable conclusions.

Diagnostic accuracy: Screening

and Opioid Assessment for

Patients with Pain (SOAPP)

version 1

Low

Based on a cutoff score of >8, sensitivity

was 0.68 and specificity of 0.38 in one

study, for a PLR of 1.11 and NLR of 0.83.

Based on a cutoff score of >6, sensitivity

was 0.73 in one study.

32

b. In patients with chronic pain, what is the effectiveness of use of risk prediction instruments on

outcomes related to overdose,

addiction, abuse, or misuse?

Key Question

Strength of

Evidence

Conclusion

Outcomes related to abuse

Insufficient

No study evaluated the effectiveness of

risk prediction instruments for reducing

outcomes

related to overdose, addiction,

abuse, or misuse.

Abbreviations: CI=confidence interval, HR=hazard ratio, MED=morphine equivalent dose,

mg=milligrams, NLR=negative likelihood ratio, OR=odds ratio, PLR=positive likelihood ratio

As can be seen in the above table, the EPC found a paucity of studies on the long-term (more

than 1 year) outcomes of opioid treatment for chronic pain, and those identified in the literature

were typically of poor quality. Further, there are insufficient data to guide appropriate patient

assessment, opioid selection, dosing strategies, or risk mitigation. This underscores the need for

high-quality research that focuses on establishing the appropriateness of long-term opioid

treatment for the management of chronic pain. After listening to workshop speakers and

audience members and examining the limited availability of studies on long-term opioid

treatment, the panel makes the following recommendations:

1. Federal and non-federal agencies should sponsor research to identify which types of pain,

specific diseases, and patients are most likely to benefit and incur harm from opioids.

Such studies could use a range of study approaches and could include demographic,

psychological, socio-cultural, ecological, and biological characterizations of patients in

combinations with clear and accepted definitions of chronic pain and well-characterized

records for opioid and other pain medications.

33

2. Federal and non-federal agencies should sponsor the development and evaluation of

multidisciplinary pain interventions, including cost-benefit analyses and identification of

barriers to dissemination.

3. Federal and non-federal agencies should sponsor research to develop and validate

research measurement tools for identification of patient risk and outcomes (including

benefit and harm) related to long-term opioid use that can be adapted for clinical settings.

4. Electronic health record vendors and health systems should incorporate decision support

for pain management and facilitate export of clinical data to be combined with data from

other health systems to better identify patients who benefit from or are harmed by opioid

use.

5. Researchers on the effectiveness and harm of opioids should consider alternative designs

(e.g., N of 1 trials, qualitative studies, implementation science, secondary analysis, Phase

1 and 2 design) in addition to randomized clinical trials.

6. Federal and non-federal agencies should sponsor research on risk identification and

mitigation strategies, including drug monitoring, prior to widespread integration of these

into clinical care. This research should also assess how policy initiatives impact

patient/public health outcomes.

7. Federal and non-federal agencies and health care systems should sponsor research and

quality improvement efforts to facilitate evidence-based decision-making at every step of

the clinical decision process.

8. In the absence of definitive evidence, clinicians and health care systems should follow

current guidelines by professional societies about which patients and which types of pain

34

should be treated with opioids, and about how best to monitor patients and mitigate risk

for harm.

9. NIH or other federal agencies should sponsor conferences to promote harmonization of

guidelines of professional organizations to facilitate their implementation more

consistently in clinical care.

Summary

The rise in the number of Americans with chronic pain and the concurrent increase in the use of

opioids to treat this pain have created a situation where large numbers of Americans are

receiving suboptimal care. Patients who are in pain are often denied the most effective

comprehensive treatments; conversely, many patients are inappropriately prescribed medications

that may be ineffective and potentially harmful. At the root of the problem is the inadequate

knowledge about the best approaches to treat various types of pain, balancing the effectiveness

with the potential for harm, as well as a dysfunctional health care delivery system that

encourages clinicians to prescribe the easiest rather than the best approach for addressing pain.

The EPC report identified few studies that were able to answer the key questions, suggesting the

dire need for research on the effectiveness and safety of opioids as well as optimal management

and risk mitigation strategies. What was particularly striking to the panel was the realization that

there is insufficient evidence for every clinical decision that a provider needs to make regarding

the use of opioids for chronic pain, leaving the provider to rely on his or her own clinical

experience.

35

Because of the inherent difficulties of studying pain and the large number of patients already

receiving opioids, new research designs and analytic methods will be needed to adequately

answer the important clinical and research questions.

Until the needed research is conducted, health care delivery systems and clinicians must rely on

the existing evidence as well as guidelines issued by professional societies, which need to be

continually updated and harmonized to reflect recent research evidence and changes in expert

opinion. Systems of care must facilitate the implementation of these guidelines rather than

relying solely on individual clinicians, who are often overburdened and have insufficient

resources.

Clearly, there are some patients for whom opioids are the best treatment for their chronic pain.

However, for many more, there are likely to be more effective approaches. The challenge is to

identify the conditions in patients for which opioid use is most appropriate, the regimens that are

optimal, the alternatives for those who are unlikely to benefit from opioids, and the best

approach to ensuring that every patient’s individual needs are met by a patient-centered health

care system. For the more than 100 million Americans living with chronic pain, meeting this

challenge cannot wait.

National Institutes of Health Office of Disease Prevention

Pathways to Prevention Workshop:

The Role of Opioids in the Treatment of Chronic Pain

September 29 – 30, 2014

Panelists

36

David B. Reuben, M.D., Panel Chairperson

Chief

Division of Geriatrics

Director

Multicampus Program in Geriatric Medicine and

Gerontology

Professor of Medicine

Division of Geriatrics

David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of

California, Los Angeles

Anika A. H. Alvanzo, M.D., M.S.

Assistant Professor of Medicine

Medical Director

Substance Use Disorders Consultation

Service

Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

Baltimore, Maryland

Takamaru Ashikaga, Ph.D.

Director

Biometry Facility

College of Medicine

University of Vermont

Burlington, Vermont

G. Anne Bogat, Ph.D.

Professor

Department of Psychology

Michigan State University

East Lansing, Michigan

Christopher M. Callahan, M.D.

Professor of Medicine

Cornelius and Yvonne Pettinga Professor

Indiana University (IU) School of Medicine

Director and Research Scientist

IU Center for Aging Research

Research Scientist

Regenstrief Institute, Inc.

Indianapolis, Indiana

Victoria Ruffing, R.N., CCRC

Director of Patient Education

Director of Nursing

Johns Hopkins University Arthritis Center

Johns Hopkins School of Medicine

Adjunct Faculty

Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing

Baltimore, Maryland

David C. Steffens, M.D., M.H.S.

Professor and Chair

Department of Psychiatry

University of Connecticut Health Center

Farmington, Connecticut

37

Speakers

Jane C. Ballantyne, M.D.

Professor, Retired

Department of Anesthesiology and Pain

Medicine

University of Washington

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Stephen Bruehl, Ph.D.

Professor

Department of Anesthesiology

Vanderbilt University School of Medicine

Nashville, Tennessee

Roger Chou, M.D., FACP

Director

Pacific Northwest Evidence-based Practice

Center

Professor of Medicine

Department of Medical Informatics &

Clinical Epidemiology

Oregon Health & Science University

Portland, Oregon

Myra Christopher, L.H.D. (Hon.)

Kathleen M. Foley Chair for Pain and

Palliative Care

Center for Practical Bioethics

Kansas City, Missouri

Daniel J. Clauw, M.D.

Professor of Anesthesiology, Medicine and

Psychiatry

Director

Chronic Pain and Fatigue Research Center

University of Michigan Medical Center

Ann Arbor, Michigan

Phillip O. Coffin, M.D., M.I.A.

Director of Substance Use Research

HIV Prevention Section

San Francisco Department of Public Health

San Francisco, California

Wilson M. Compton, M.D., M.P.E.

Deputy Director

National Institute on Drug Abuse

National Institutes of Health

Bethesda, Maryland

Edward C. Covington, M.D.

Director

Neurological Center for Pain

Cleveland Clinic

Cleveland, Ohio

Ricardo A. Cruciani, M.D., Ph.D.

Director

Center for Comprehensive Pain

Management and Palliative Care

Capital Institute for Neuroscience

Capital Health Medical Center

Hopewell, New Jersey

Tracy W. Gaudet, M.D.

Director

Office of Patient Centered Care and Cultural

Transformation

Veterans Health Administration

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs

Washington, DC

Joseph T. Hanlon, Pharm.D., M.S.

Professor

Division of Geriatrics/Gerontology

Department of Medicine

University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

38

Nathaniel P. Katz, M.D., M.S.

President and Chief Executive Officer

Analgesic Solutions

Adjunct Assistant Professor of Anesthesia

Tufts University School of Medicine

Natick, Massachusetts

Erin E. Krebs, M.D., M.P.H.

Core Investigator

Center for Chronic Disease Outcomes

Research

Medical Director

Women Veterans Comprehensive Health

Center

Minneapolis Veterans Administration

Associate Professor

Department of Medicine

University of Minnesota

Minneapolis, Minnesota

Story C. Landis, Ph.D.

Director

National Institute of Neurological Disorders

and Stroke

National Institutes of Health

Bethesda, Maryland

Jane C. Maxwell, Ph.D.

Senior Research Scientist

Addiction Research Institute

The University of Texas at Austin School of

Social Work

Austin, Texas

David M. Murray, Ph.D.

Associate Director for Prevention

Director

Office of Disease Prevention

Division of Program Coordination,

Planning, and Strategic Initiatives

Office of the Director

National Institutes of Health

Bethesda, Maryland

Steven D. Passik, Ph.D.

Vice President

Clinical Research and Advocacy

Millenium Research Institute

Millennium Laboratories

San Diego, California

Russell K. Portenoy, M.D.

Chief Medical Officer

Metropolitan Jewish Health System (MJHS)

Hospice and Palliative Care

Director

MJHS Institute for Innovation in Palliative

Care

Professor of Neurology

Albert Einstein College of Medicine

New York, New York

David B. Reuben, M.D.

Chief

Division of Geriatrics

Director

Multicampus Program in Geriatric Medicine

and Gerontology

Professor of Medicine

Division of Geriatrics

David Geffen School of Medicine at the

University of California, Los Angeles

Los Angeles, California

Wendy B. Smith, Ph.D., M.A., BCB

Senior Scientific Advisor for Research

Development and Outreach

Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences

Research

Office of the Director

National Institutes of Health

Bethesda, Maryland

David J. Tauben, M.D.

Clinical Associate Professor

Department of Medicine

Chief (Interim)

Division of Pain Medicine

Medical Director

Center for Pain Relief

University of Washington

Seattle, Washington

39

David A. Thomas, Ph.D.

Deputy Director

Division of Clinical Neurosciences and

Behavioral Research

National Institute on Drug Abuse

National Institutes of Health

Bethesda, Maryland

Judith Turner, Ph.D.

Professor

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral

Sciences

University of Washington

Seattle, Washington

Nora D. Volkow, M.D.

Director

National Institute on Drug Abuse

National Institutes of Health

Bethesda, Maryland

Sharon Walsh, Ph.D.

Professor of Behavioral Sciences,

Psychiatry, Pharmacology, and

Pharmaceutical Sciences

Director

Center on Drug and Alcohol Research

University of Kentucky College of Medicine

Lexington, Kentucky

Working Group Planning Meeting for the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Pathways to

Prevention Workshop:

Effectiveness and Risks of Long-Term Opioid Treatment of Chronic Pain

August 28–29, 2013

Working Group

40

Chairpersons: David A. Thomas, Ph.D.

Deputy Director

Division of Clinical Neurosciences and Behavioral Research

National Institute on Drug Abuse

National Institutes of Health

Richard A. Denisco, M.D., Ph.D.

Services Research Branch

National Institute on Drug Abuse

National Institutes of Health

Caroline Acker, Ph.D.

Associate Professor and Head

Department of History

Carnegie Mellon University

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Jane C. Ballantyne, M.D.

Professor, Retired

Department of Anesthesiology and Pain

Medicine

University of Washington

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Wen G. Chen, Ph.D.

Program Director

Sensory and Motor Disorders of Aging

Behavioral and Systems Neuroscience

Branch

Division of Neuroscience

National Institute on Aging

National Institutes of Health

Bethesda, Maryland

Edward C. Covington, M.D.

Director

Neurological Center for Pain

Cleveland Clinic

Cleveland, Ohio

Jody Engel, M.A., R.D.

Director of Communications

Office of Disease Prevention

Division of Program Coordination,

Planning, and Strategic Initiatives

Office of the Director

National Institutes of Health

Bethesda, Maryland

Roger B. Fillingim, Ph.D.

Professor

University of Florida College of Dentistry

Director

University of Florida Pain Research and

Intervention Center of Excellence

Gainesville, Florida

Joseph T. Hanlon, Pharm.D., M.S.

Professor of Medicine and

Health Scientist

Division of Geriatric Medicine

University of Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Working Group Planning Meeting for the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Pathways to

Prevention Workshop:

Effectiveness and Risks of Long-Term Opioid Treatment of Chronic Pain

August 28–29, 2013

Working Group

41

Christopher M. Jones, Pharm.D., M.P.H.

Lieutinent Commander, U.S. Public Health

Service

Team Lead

Prescription Drug Overdose Team

Division of Unintentional Injury Prevention

National Center for Injury Prevention and

Control

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention