MANAGING FOR RESULTS:

The Performance Management Playbook for

Federal Awarding Agencies

April 2020

VERSION I

The practices in the PM Playbook are shared informally for the purpose of peer to peer technical assistance, stakeholder engagement, and

dialogue. This document is not official OMB guidance, and is not intended for audit purposes. Implementation of the practices discussed may

differ by agency and applicable legal authority.

April 27, 2020 Page 1

Executive Summary

In coordination with the Chief Financial Officers Council (CFOC) and the Performance

Improvement Council (PIC), the President’s Management Agenda (PMA) Cross Agency Priority

(CAP) Goal, Result-Oriented Accountability for Grants, Performance Workgroup is proud to

release version I of the “Managing for Results: The Performance Management Playbook for

Federal Awarding Agencies (PM Playbook).

Playbook Purpose. The purpose of the PM Playbook is to provide Federal awarding agencies

with promising practices for increasing their emphasis on analyzing program and project results

as well as individual award recipient performance, while maintaining, and where possible

minimizing, compliance efforts. Some ideas in the PM Playbook are reflected in the proposed

revisions to Title 2 of the Code of Federal Regulations (2 CFR) for Grants and Agreements. As a

playbook, this document is not Office of Management and Budget (OMB) guidance but a

resource for Federal awarding agencies as they continue efforts to improve the design and

implementation of Federal financial assistance programs for awards. This first version of the PM

Playbook is released with the intent to engage stakeholders on practices and principles for

improving performance to help shape the Federal strategy in this area and to influence future

revisions to 2 CFR. Importantly, the PM Playbook represents the Federal government’s shift in a

direction toward performance and focusing on results. Subsequent versions of the PM Playbook

will be released as organizational learning occurs in implementing the practices and concepts

outline in the document.

Shifting the Grants Management Paradigm. Federal awarding agencies are encouraged to

begin to make a paradigm shift in grants management from one heavy on compliance to a more

balanced approach that includes establishing measurable program and project goals and

analyzing data to improve results. This effort supports the President’s Management Agenda

(PMA), which seeks to improve the ability of agencies to “deliver mission outcomes, provide

excellent service, and effectively steward taxpayer dollars on behalf of the American people.”

1

To track and achieve these priorities, the PMA leverages Cross-Agency Priority (CAP) Goals,

including the Results-Oriented Accountability for Grants CAP Goal (Grants CAP Goal). The

purpose of the Grants CAP Goal is to “maximize the value of grant funding by applying a risk-

based, data-driven framework that balances compliance requirements with demonstrating

successful results.”

2

Strategy for Getting There. The Grants CAP goal has four strategies, including one dedicated

to “achieving program and project goals and objectives.” The objective of this strategy is to

demonstrate advancement toward or achievement of program goals and objectives by focusing

1

The President’s Management Agenda website: https://www.performance.gov/PMA/PMA.html

2

The President’s Management Agenda, Results-Oriented Accountability for Grants website:

https://www.performance.gov/CAP/grants/

The practices in the PM Playbook are shared informally for the purpose of peer to peer technical assistance, stakeholder engagement, and

dialogue. This document is not official OMB guidance, and is not intended for audit purposes. Implementation of the practices discussed may

differ by agency and applicable legal authority.

April 27, 2020 Page 2

on developing processes and tools to help Federal awarding entities improve their ability to

monitor program and project performance, improve award recipient performance, and ultimately

demonstrate to the American taxpayer that they are receiving value for funds spent on grant

programs. The PM Playbook is a product of that effort. An interagency workgroup is charged

with achieving the goals of this strategy, including the development of the PM Playbook.

3

The

intended audience for the PM Playbook is Federal awarding agencies that provide Federal

financial assistance (grants and/or cooperative agreements) to non-Federal entities. While

Federal statutes require compliance activities to be upheld, awarding agencies’ focus on

compliance often overshadows the importance of examining performance results on a recurring

basis during the grant period of performance and immediately after awards are completed.

Agencies often have difficulty showing that Federal dollars are spent wisely and that those

dollars have the intended impact and produce value to the taxpayer. See Figure 1: Balancing

compliance and performance to achieve results.

Figure 1: Shifting the balance from compliance toward performance to achieve results

4

To assess program impact, agencies are encouraged to establish clear program goals and

objectives, and measure both project and individual award recipient progress against them.

Applied in the context of Federal financial assistance awards, the practices identified in this

playbook are informed by and complement the work of the Performance Improvement Council

(PIC), which has focused on institutionalizing performance management as a key management

discipline and capability more broadly within the Federal government following enactment of the

Government Performance and Results Modernization Act (GPRA). The PM Playbook is one of

several recent administration efforts to modernize the Federal grants management process by

strengthening the Federal agency approach to performance. Some of these additional efforts

include, but are not limited to: the Grants Management Federal Integrated Business Framework

3

An interagency work group representing nearly 20 Federal agencies designed the PM Playbook.

4

Figure developed by authors of the PM Playbook.

The practices in the PM Playbook are shared informally for the purpose of peer to peer technical assistance, stakeholder engagement, and

dialogue. This document is not official OMB guidance, and is not intended for audit purposes. Implementation of the practices discussed may

differ by agency and applicable legal authority.

April 27, 2020 Page 3

(FIBF), the Reducing Federal Administrative Burdens on Research Report, the Performance

Improvement Council’s Goal Playbook, and proposed revisions to the “Uniform Administrative

Requirements, Cost Principles, and Audit Requirements” in Title 2 of the Code of Federal

Regulations, Chapter 200 (2 CFR 200).

5678

As part of on-going efforts to continue the dialogue on this topic and develop future iterations of

this work, the Grants CAP Goal Performance Workgroup is looking to hear from stakeholders at

[email protected]OP.Gov with any comments, suggestions, and examples of success to be

considered in future iterations of the PM Playbook.

5

The Federal Integrated Business Framework (FIBF): https://ussm.gsa.gov/fibf/

6

Reducing Federal Administrative Burdens on Research Report: https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-

content/uploads/2018/05/Reducing-Federal-Administrative-and-Regulatory-Burdens-on-Research.pdf

7

Performance Improvement Council’s Goal Playbook: https://www.pic.gov/goalplaybook/

8

Federal Register Notice for the Proposed Revisions to Title 2 of the Code of Federal Regulations:

https://s3.amazonaws.com/public-inspection.federalregister.gov/2019-28524.pdf

The practices in the PM Playbook are shared informally for the purpose of peer to peer technical assistance, stakeholder engagement, and

dialogue. This document is not official OMB guidance, and is not intended for audit purposes. Implementation of the practices discussed may

differ by agency and applicable legal authority.

April 27, 2020 Page 4

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I. Introduction ...........................................................................................................................6

Definitions ...............................................................................................................................7

Federal Laws and Regulations ............................................................................................... 10

II. Performance Management Basics ..................................................................................... 11

Programmatic Performance Management Principles .............................................................. 11

Risk Management and Performance Management .................................................................. 14

The Federal Grants Lifecycle ................................................................................................. 16

III. The Performance Management Approach for Grants .................................................... 17

Phase 1: Program Administration........................................................................................... 19

Program Design Steps ........................................................................................................ 23

Notice of Funding Opportunity (NOFO) ............................................................................ 27

Performance Management Requirements ........................................................................... 30

Phase 2: Pre-Award Management .......................................................................................... 32

Selection Criteria for Making Awards ................................................................................ 32

Phase 3: Award Management ................................................................................................ 34

Risk Assessment and Special Conditions............................................................................ 34

Federal Award and Performance Reporting ........................................................................ 35

Issuing Awards .................................................................................................................. 36

Phase 4: Post-Award Management and Closeout ................................................................... 36

Award Recipient Performance Monitoring and Assessment................................................ 37

Award Closeout ................................................................................................................. 39

Phase 5: Program Oversight ................................................................................................... 41

Analysis of Program and Project Results ............................................................................ 42

Dissemination of Lessons Learned ..................................................................................... 44

Program Evaluation............................................................................................................ 44

Federal Evidence Building ................................................................................................. 45

IV. Maintaining a Results-Oriented Culture ......................................................................... 45

The practices in the PM Playbook are shared informally for the purpose of peer to peer technical assistance, stakeholder engagement, and

dialogue. This document is not official OMB guidance, and is not intended for audit purposes. Implementation of the practices discussed may

differ by agency and applicable legal authority.

April 27, 2020 Page 5

V. Conclusion .......................................................................................................................... 50

VI. Appendices ........................................................................................................................ 52

Appendix A. Glossary of Terms ............................................................................................ 52

Appendix B. Key Stakeholders .............................................................................................. 57

Appendix C. Federal Laws and Regulations ........................................................................... 59

VII. Agency Acknowledgements ............................................................................................. 65

The practices in the PM Playbook are shared informally for the purpose of peer to peer technical assistance, stakeholder engagement, and

dialogue. This document is not official OMB guidance, and is not intended for audit purposes. Implementation of the practices discussed may

differ by agency and applicable legal authority.

April 27, 2020 Page 6

I. Introduction

The primary purpose of the Performance Management Playbook (PM Playbook) is to provide

Federal awarding agencies with promising performance practices for examining larger program

and project goals and subsequent results as well as individual award recipient performance. To

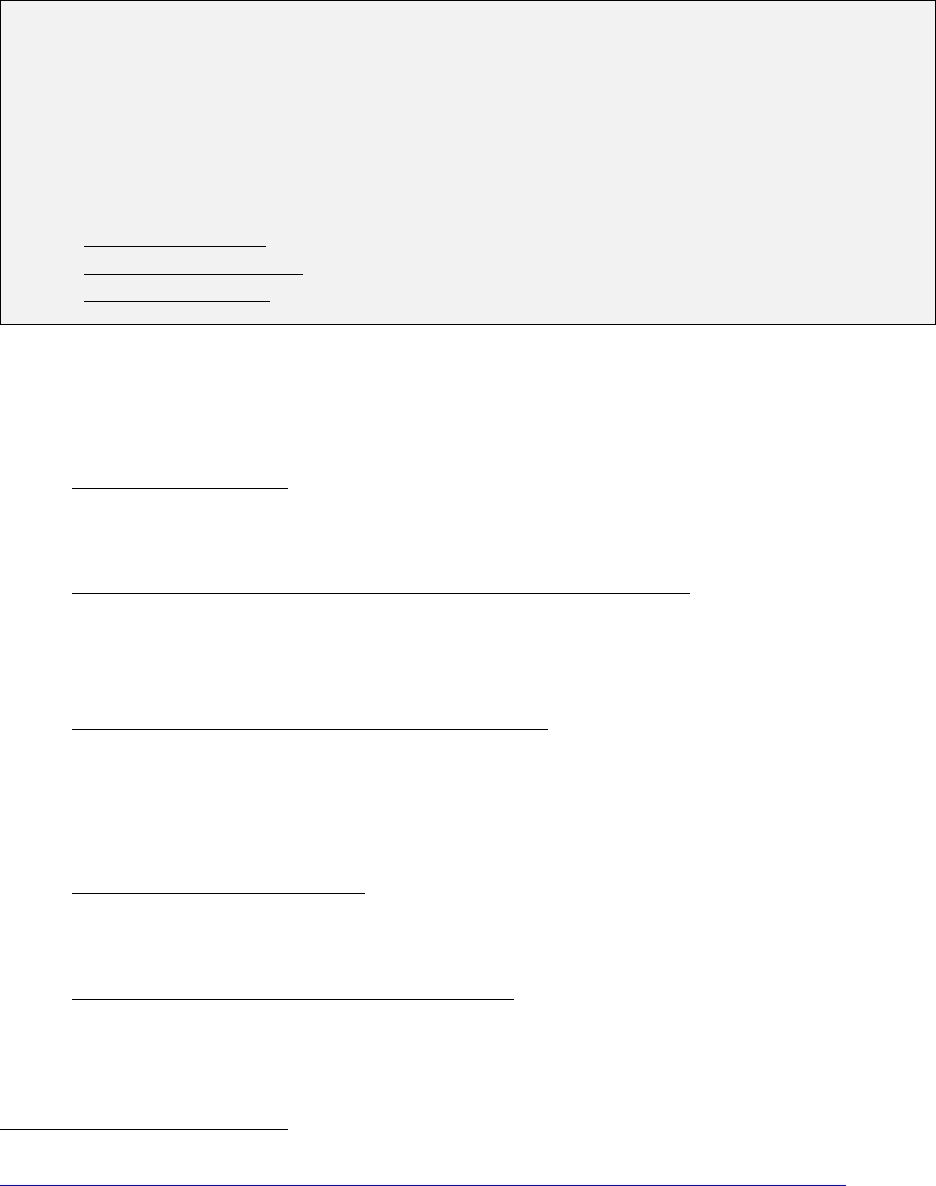

this end, the PM Playbook breaks down performance management into three distinct, yet

connected, levels of activity. These activities take place at the program (i.e., assistance listing),

project (i.e., Notice of Funding Opportunity (NOFO)), and sub-project (i.e.; award recipient)

levels.

9

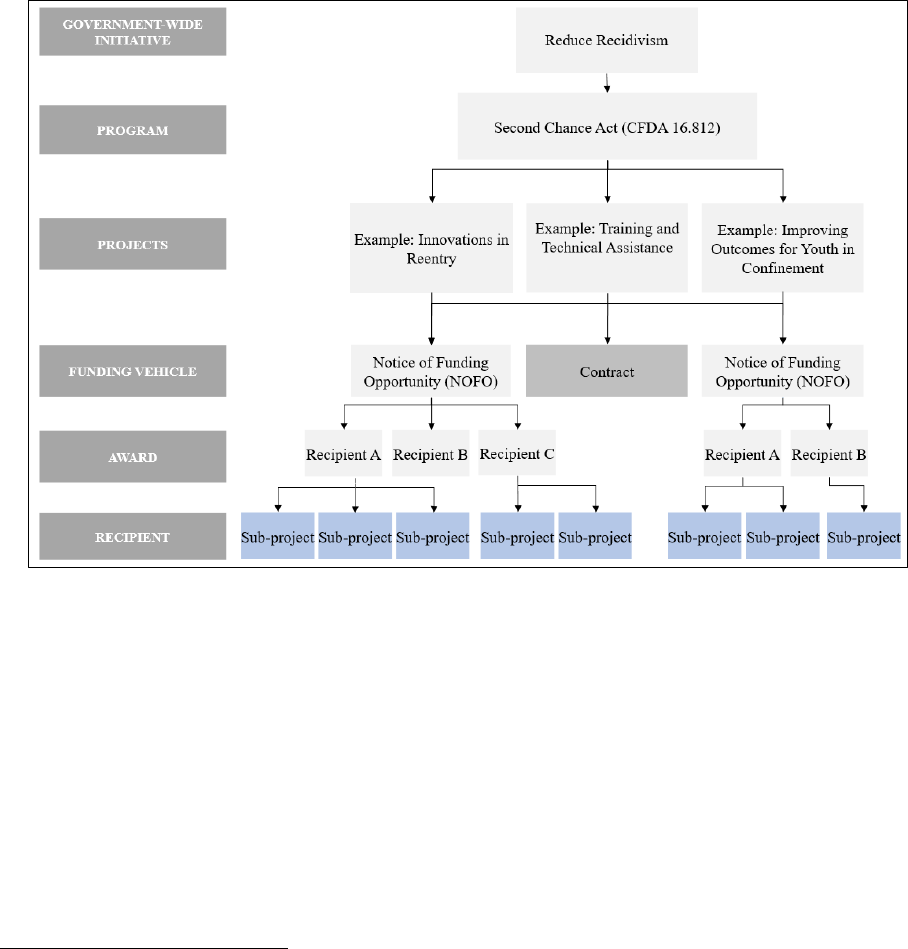

See Figure 2 below for an illustration of the three levels of performance activities. While

some Federal agencies may use other terms for these same activities, the PM Playbook uses

program, project, and sub-project throughout the document to avoid confusion over terminology.

Figure 2: Performance Activity Levels

10

The PM Playbook promotes a common understanding of performance management practices and

processes for Federal awarding agencies and is a resource for leaders and others who want to

strengthen their agency’s approach to performance by focusing on program, project, and sub-

project goals, objectives, and results.

11

9

The term sub-project refers to the activities that an award recipient plans to accomplish with the award.

10

Figure developed by authors of the PM Playbook.

11

Most often, performance is assessed within the award period. However, at times evaluations may examine award

recipient and/or program performance after the award period has ended.

The practices in the PM Playbook are shared informally for the purpose of peer to peer technical assistance, stakeholder engagement, and

dialogue. This document is not official OMB guidance, and is not intended for audit purposes. Implementation of the practices discussed may

differ by agency and applicable legal authority.

April 27, 2020 Page 7

Program goals and their intended results, however, differ by type of Federal program. For

example, criminal justice programs may focus on specific goals such as reducing crime; basic

scientific research programs may focus on expanding knowledge and/or promoting new

discoveries; and infrastructure programs may fund specific building or transportation projects.

With this in mind, the PM Playbook highlights how practices may differ depending on the types

of awards an agency oversees (such as service delivery, science/research, or infrastructure).

I.A. Definitions

The PM Playbook contains a Glossary of Terms in the Appendix, which align with the standard

language and definitions in 2 CFR Part 200 and OMB Circular A-11 (2019 version), Preparation,

Submission, and Execution of the Budget (A-11 (2019)). Federal agencies often use different

terms and phrases to describe the same activities or processes. For example, different agencies

use “Funding Opportunity,” “Funding Opportunity Announcement,” “Notice of Funding

Opportunity Announcement” (NOFO), and/or “solicitation” to refer to guidance documents with

programmatic information and instructions for applicants on how to apply for awards. For

consistency and clarity, the PM Playbook uses NOFO since this is the phrase used in 2 CFR 200.

A NOFO is “any paper or electronic issuance that an agency uses to announce a funding

opportunity.”

12

OMB defines performance management as the “use of goals, measurement, evaluation, analysis

and data-driven reviews to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of agency operations.”

13

The PM Playbook references a more granular level and uses the phrase “performance

management” to refer to program and project results as well as award recipient performance.

14

While Federal agencies can be recipients of Federal awards, for the purposes of the PM

Playbook, the phrase “award recipient” refers to non-Federal entities (NFE) that receive Federal

financial assistance.

15

In addition, the term “program” throughout this playbook refers to all Federal awards assigned a

single assistance listing number in the System for Award Management (SAM), which was

formerly the Catalogue of Federal Domestic Assistance (CFDA).

16

2 CFR 200 requires

assistance listings to have unique titles and be clearly aligned with the program’s authorization

12

The definition described above is found in 2 CFR §25.200. In 2 CFR §200.1, NOFO is further defined as a

“formal announcement of the availability of Federal funding through a financial assistance program from a Federal

awarding agency.”

13

OMB Circular A-11 (2019 version) Part 6, Section 200, p23: https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-

content/uploads/2018/06/a11.pdf

14

This phrase is not to be confused with human resources or employee performance.

15

2 CFR §200.1 defines a non-Federal entity as a “state, local government, Indian Tribe, Institution of Higher

Education, or non-profit organization that carries out a Federal award as a recipient or sub recipient.”

16

Beta.SAM.gov describes an assistance listing as a program designed to “provide assistance to the American public

in the form of projects, services, and activities, which support a broad range of programs—such as education, health

care, research, infrastructure, economic development and other programs.”

The practices in the PM Playbook are shared informally for the purpose of peer to peer technical assistance, stakeholder engagement, and

dialogue. This document is not official OMB guidance, and is not intended for audit purposes. Implementation of the practices discussed may

differ by agency and applicable legal authority.

April 27, 2020 Page 8

and Congressional intent. To clarify further, a program (assistance listing) may have one or more

associated projects.

17

The PM Playbook uses the term “project” to refer to the activities escribed in individual NOFOs.

For example, each year the Department of Justice (DOJ) Second Chance Act (SCA) program

(i.e., assistance listing) has multiple NOFOs, which provide funding for projects that fall under

the SCA authorization. The goals and objectives of each project are associated with the larger

program.

18

See Figure 3 for an illustration on how a government-wide initiative flows down to a

program, projects, funding vehicle, award, and recipient for the DOJ SCA example.

17

It is important to note that the activity codes used for the Federal budget program inventory (see OMB Circular A-

11 Part 6 (2019 version)), are not the same as the assistance listing number. In June 2019, OMB issued updated

guidance to agencies on further implementation of the GPRAMA 2010 requirement for a Federal Program

Inventory, to leverage program activity(ies), as defined in 31 U.S.C 1115(h)(11), for implementation of the program

reporting requirements. Agencies’ consideration of how these Program Activities link to budget, performance, and

other information will transform the reporting framework to enable improved decision-making, accountability, and

transparency of the Federal Government. The current links between the Program Activity and the CFDA can be a

one-to-one, a one-to-many, or a many-to-one relationship. These linkages can be explored on USASpending.gov.

More information can be found in A-11, Part 6, (2019 version).

18

Please note, in some instances a NOFO may be aligned with more than one program (assistance listing).

The practices in the PM Playbook are shared informally for the purpose of peer to peer technical assistance, stakeholder engagement, and

dialogue. This document is not official OMB guidance, and is not intended for audit purposes. Implementation of the practices discussed may

differ by agency and applicable legal authority.

April 27, 2020 Page 9

Figure 3: DOJ SCA Example: Program, Project, Funding Vehicle, Award and Recipient

Relationships

19

20

19

The Second Chance Act (SCA) supports state, local, and tribal governments and nonprofit organizations in their

work to reduce recidivism and improve outcomes for people returning from state and federal prisons, local jails, and

juvenile facilities. https://csgjusticecenter.org/nrrc/projects/second-chance-act/

20

Figure developed by authors of the PM Playbook an illustrative example. Actual projects and funding vehicles

many vary.

The practices in the PM Playbook are shared informally for the purpose of peer to peer technical assistance, stakeholder engagement, and

dialogue. This document is not official OMB guidance, and is not intended for audit purposes. Implementation of the practices discussed may

differ by agency and applicable legal authority.

April 27, 2020 Page 10

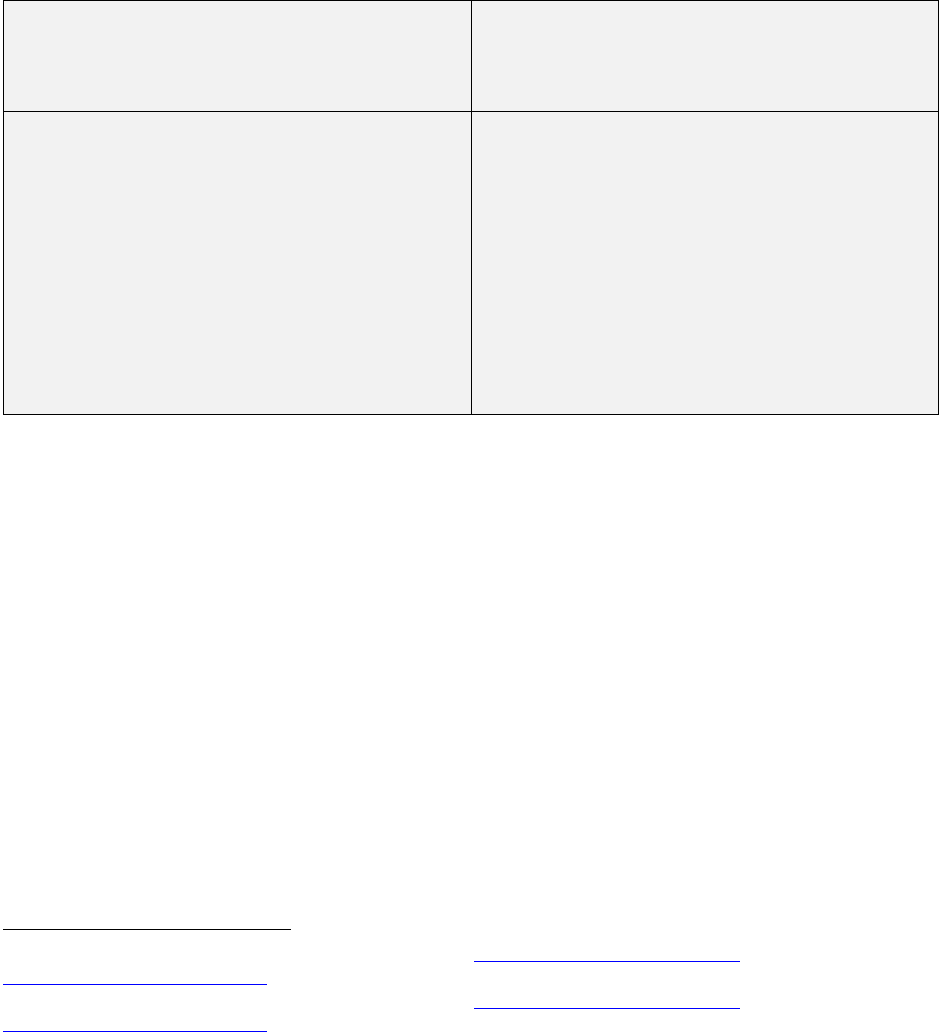

Other key definitions to keep in mind when reviewing the PM Playbook are output and outcome.

Table 1: Output and Outcome Measures Defined

2122

Output

Quantity of products or services delivered by

a program, such as the number of inspections

completed or the number of people trained.

Outcome

The desired results of a program. For

example, an outcome of a nation-wide

program aimed to prevent the transmission of

HIV infection might be a lower rate of new

HIV infections in the United States. Agencies

are strongly encouraged to set outcome-

focused performance goals to ensure they

apply the full range of tools at their disposal

to improve outcomes and find lower cost

ways to deliver.

I.B. Federal Laws and Regulations

Several statutes and regulations underpin performance management in the 21

st

century. Some of

the Federal laws and regulations that the PM Playbook aligns with are listed below.

23

Many of

these Federal laws and regulations are related in that they promote the same objectives outlined

in the PMA: to increase transparency, accountability, and results-oriented decision-making. They

also promote a risk-based approach to making awards, establishing clear goals and objectives to

show progress toward achieving results, and showing the taxpayer what they are receiving for

the funding spent on grant programs. See Appendix D for more information on each of the

Federal laws and regulations.

• Federal Grant and Cooperative Agreement Act of 1977

• Chief Financial Officers Act of 1990

• Clinger-Cohen Act of 1996 (previously the Information Technology Management

Reform Act)

• Federal Funding Accountability and Transparency Act (FFATA) of 2006

• Government Performance and Results Modernization Act of 2010

• Digital Accountability and Transparency Act (DATA) of 2014

21

OMB Circular A-11 (version 2019) Part 6, Section 200: https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-

content/uploads/2018/06/a11.pdf

22

OMB Circular A-11 (version 2019) Part 6, Section 200: https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-

content/uploads/2018/06/a11.pdf

23

Agencies may implement the tools and promising practices in the PM Playbook in support of their authorizations

and appropriations as established by Congress.

The practices in the PM Playbook are shared informally for the purpose of peer to peer technical assistance, stakeholder engagement, and

dialogue. This document is not official OMB guidance, and is not intended for audit purposes. Implementation of the practices discussed may

differ by agency and applicable legal authority.

April 27, 2020 Page 11

• Program Management Improvement Accountability Act (PMIAA) of 2016

• American Competitiveness and Innovation Act (AICA) of 2017

• Foundations for Evidence-Based Policymaking Act of 2018

o The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) M-19-23, “Phase 1

Implementation of the Foundations for Evidence-Based Policymaking Act of

2018: Learning Agendas, Personnel, and Planning Guidance” and M-20-12,

“Phase 4 Implementation of the Foundations for Evidence-Based

Policymaking Act of 2018: Program Evaluation Standards and Practices”

• Grant Reporting Efficiency and Agreements Transparency (GREAT) Act of 2019

• OMB Circular A-123, “Management’s Responsibility for Enterprise Risk

Management and Internal Control”

• OMB Circular A-11, Part 6, (2019 version), “The Federal Performance Framework

for Improving Program and Service Delivery”

• Code of Federal Regulations (CFR), Title 2 “Grants and Agreements,” Part 200

“Uniform Administrative Requirements, Cost Principles, and Audit Requirements for

Federal Awards” (Developed 2013, Revised 2020)

II. Performance Management Basics

As a reference guide Federal agencies may use in the context of financial assistance awards, the

PM Playbook focuses on strengthening the Federal government’s approach to performance

management by encouraging Federal awarding agencies to set measurable program and project

goals and objectives, and to use relevant data to measure both program and project results and

award recipient performance. While there is no one “right” path to improve performance

management practices, this section provides an overview of how performance management may

fit into larger agency processes as well as the grants lifecycle. This section is not all-inclusive but

rather highlights significant issues that agency leaders and their program, policy, grant, and

performance managers should consider at all three levels of performance activity: program,

project, and sub-project.

II.A. Programmatic Performance Management Principles

The PM Playbook promotes several important principles that are necessary to successfully

implement a performance management framework within an awarding agency. While there are

other important principles, such as transparency and accountability that awarding agencies may

consider, the four principles listed below are essential to changing and/or strengthening Federal

awarding agency approaches to program, project, and sub-project performance.

1. Leadership Support is Critical to Success

2. Performance Management is Everyone’s Responsibility

3. Data Informed Decision-Making Improves Results

4. Continuous Improvement is Crucial to Achieving Results

1. Leadership Support is Critical to Success

The practices in the PM Playbook are shared informally for the purpose of peer to peer technical assistance, stakeholder engagement, and

dialogue. This document is not official OMB guidance, and is not intended for audit purposes. Implementation of the practices discussed may

differ by agency and applicable legal authority.

April 27, 2020 Page 12

Performance management processes are most successful when leaders champion them.

Leaders at all levels of an agency should participate in clearly defining program goals and

objectives (in relation to statutes, appropriations, and agency priorities). Leaders should

communicate program goals and objectives to grant managers and other relevant employees

so that they can align project (i.e., NOFO) goals and objectives to them.

Promising Practice - Leadership Support

Leadership support at the U.S. Department of State (State Department) has been integral to

the success of the agency’s Managing for Results:

Program Design and Performance

Management Toolkit.

24

The State Department implemented the toolkit as a manual for its

bureaus, offices, and posts to use to assess the degree to which their programs and projects

were successful in advancing long-term strategic plan goals and achieving short-term results.

The toolkit describes the major steps of program design and can be us

ed to design new

programs and/or evaluate whether programs are o

n track to meet their intended goals.

Several leaders championed the initial use of the toolkit and due to leadership’s continued

backing, the toolkit remains in wide-use throughout the State Department.

2. Performance Management is Everyone’s Responsibility

Everyone involved in the grants management lifecycle plays an important role in achieving

effective results. Federal employees in awarding agencies are encouraged to understand and

participate in the performance management activities related to their programs. Grant

managers, performance analysts, program managers, and others should be involved in the

entire program design and implementation process so that clear, measurable program goals

and performance measures are established and tracked through each associated project, as

applicable. Agency policies should provide clear guidance on the performance management

roles and responsibilities within the organization.

24

The Department of State’s “Program Design and Performance Management (PD/PM) Toolkit” provides an

extensive overview of how Federal agencies can achieve their strategic goals by following strong program design

and performance management practices. See

https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Program-Design-

and-Performance-Management-Toolkit.pdf

The practices in the PM Playbook are shared informally for the purpose of peer to peer technical assistance, stakeholder engagement, and

dialogue. This document is not official OMB guidance, and is not intended for audit purposes. Implementation of the practices discussed may

differ by agency and applicable legal authority.

April 27, 2020 Page 13

Promising Practice – Clear Lines of Responsibility

The Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) Office of Grants provides

Department-wide leadership on grants policy and evaluation, and maintains HHS’ Grants

Policy Administration Manual (GPAM). GPAM describes the roles and responsibilities of

several grant management positions, including the grants management officer (GMO), the

grants management specialist (GMS), and the project officer/program official (PO). While

the PO has the main responsibility for program design, NOFO development, and

monitoring program and project performance, the PO works closely with both the GMO

and GMS throughout the grants lifecycle.

3. Data Informed Decision-Making Improves Results

Data are critical to making informed decisions and improving results. Agencies use data to

assess whether and to what degree they are successful in meeting their strategic plan goals by

looking at program and project results. Agencies realize the benefits of collecting and

analyzing performance data (i.e., historical, prospective, and current) about programs and

projects when that information is used to make decisions about improving program and

project results.

Promising Practice - Data-Informed Risk Decision-Making

The National Aeronautics and Space Agency (NASA) developed the NASA Risked-

Informed Decision-Making (RIDM) Handbook to address the importance of assessing risk

as part of the analysis of alternatives within a deliberative, data-informed decision-making

process.

25

Although it was written primarily for program and project requirements-setting

decisions, its principles are applicable to all decision-making under conditions of

uncertainty, where each alternative brings with it its own risks. RIDM is an intentional

process that uses a diverse set of performance measures, in addition to other data to inform

decision-making. NASA manages its high-level objectives through agency strategic goals,

which cascade through the NASA organizational hierarchy as explicitly established and

stated objectives and performance requirements for each unit. Organizational unit

managers use RIDM to understand the risk implications of their decisions on these

objectives and to ensure that the risks to which their decisions expose the unit are within

their risk acceptance authorities.

26

This process ensures that program and project risk

exposures are understood, formally accepted, and consistent with risk tolerances at all

levels of the NASA organizational hierarchy.

25

The NASA Risk-Informed Decision-Making Handbook:

https://ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi.ntrs.nasa.gov/20100021361.pdf

26

NASA Risk Management Directive:

https://nodis3.gsfc.nasa.gov/npg_img/N_PR_8000_004B_/N_PR_8000_004B_.pdf

The practices in the PM Playbook are shared informally for the purpose of peer to peer technical assistance, stakeholder engagement, and

dialogue. This document is not official OMB guidance, and is not intended for audit purposes. Implementation of the practices discussed may

differ by agency and applicable legal authority.

April 27, 2020 Page 14

4. Continuous Improvement is Crucial to Achieving Results

Performance management does not exist in a vacuum. When awarding agencies analyze

performance data, such as performance measures and evaluation findings consistently

throughout the grant lifecycle, they can use what they learn to improve program and project

results and award recipient performance. A continuous process of analyzing data and

providing technical assistance to improve programs and projects can also help Federal

awarding agencies better implement their missions, achieve their strategic plan goals, and

improve program results.

Promising Practice - Continuous Improvement

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Office of Continuous Improvement

(OCI) coordinates the agency-wide implementation of the EPA Lean Management System

(ELMS).

27

EPA uses ELMS, which is based on Lean process improvement principles and

tools to help set ambitious and achievable targets for their programs, measure results, and

improve processes by bridging gaps between targets and results. ELMS uses regularly

updated performance and workflow data to make improvements and monitor progress

toward achieving EPA’s Strategic Plan targets.

II.B. Risk Management and Performance Management

Risk management is important to consider for performance management. As noted in the

“Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) for the U.S. Federal Government (2016) Playbook,”

Federal agencies should assess risk as part of their strategic planning, budget formulation and

execution, and grants management activities.

28

ERM promotes cross-agency discussion of risks

and coordination of risk mitigation. These discussions promote better performance management

strategies, as grants, program, and performance management are often separate agency functions.

While ERM practices take place at the agency level, grant managers and others assess risk at the

award recipient level.

29

Risk management is also a critical component of an agency’s

performance management framework because it helps identify risks that may affect advancement

toward or the achievement of a project or sub-project’s goals and objectives. Typically,

integrating risk management for grants begins in the program administration and pre-award

27

The EPA Office of Continuous Improvement: https://www.epa.gov/aboutepa/about-office-continuous-

improvement-oci

28

The ERM Playbook helps government agencies meet the requirements of the Office of Management and Budget

Circular (OMB) A-123. The ERM Playbook provides high-level key concepts for consideration when establishing a

comprehensive and effective ERM program.

See https://cfo.gov/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/FINAL-ERM-

Playbook.pdf .

29

OMB Circular A-123 and Title 2 of the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR).

The practices in the PM Playbook are shared informally for the purpose of peer to peer technical assistance, stakeholder engagement, and

dialogue. This document is not official OMB guidance, and is not intended for audit purposes. Implementation of the practices discussed may

differ by agency and applicable legal authority.

April 27, 2020 Page 15

phases of the grants lifecycle; and staff with responsibility over grant programs and grant

performance assess and manage risks during the entire process. Further, integrating risk

management practices after an award is made can assist Federal managers determine an

appropriate level of project oversight to monitor award recipient progress.

As noted in OMB Circular A-123, risk assessment is a component of internal control and an

integral part of agency internal control processes.

30

Grant managers and others assess and

monitor risk as part of their award management activities, and work to document as well as

improve internal control processes. Thus, the PM Playbook notes that there are areas of

intersection with both ERM and award recipient risk where opportunities and threats are

important to recognize.

31

Promising Practice - Assessing Risk

The Department of Education (ED) developed Risk Management Tools to assist employees

involved in implementing agency award programs with mitigating risk throughout the grants

lifecycle.

32

These tools include: 1) Grant Training Courses, including on internal controls; 2)

States’ Risk Management Practices, Tools, and Resources; 3) An Internal Controls Technical

Assistance Presentation; and 4) a Risk Management Project Management Presentation. ED’s

grant managers and others have found these tools helpful in assessing and implementing award

oversight activities.

30

OMB Circular A-123: https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/whitehouse.gov/files/omb/memoranda/2016/m-16-

17.pdf

31

Federal Integrated Business Framework (FIBF): https://ussm.gsa.gov/fibf-gm/

32

Department of Education Risk Management Tools: https://www2.ed.gov/fund/grant/about/risk-management-

tools.html?src=grants-page

The practices in the PM Playbook are shared informally for the purpose of peer to peer technical assistance, stakeholder engagement, and

dialogue. This document is not official OMB guidance, and is not intended for audit purposes. Implementation of the practices discussed may

differ by agency and applicable legal authority.

April 27, 2020 Page 16

II.C. The Federal Grants Lifecycle

The PM Playbook follows a similar grants lifecycle structure as the Federal Integrated Business

Framework (FIBF) for Grants Management.

33

The PM Playbook strongly emphasizes program

design in Phase I of the grants lifecycle, which also mirrors proposed revisions to 2 CFR 200,

which includes a new provision on program design.

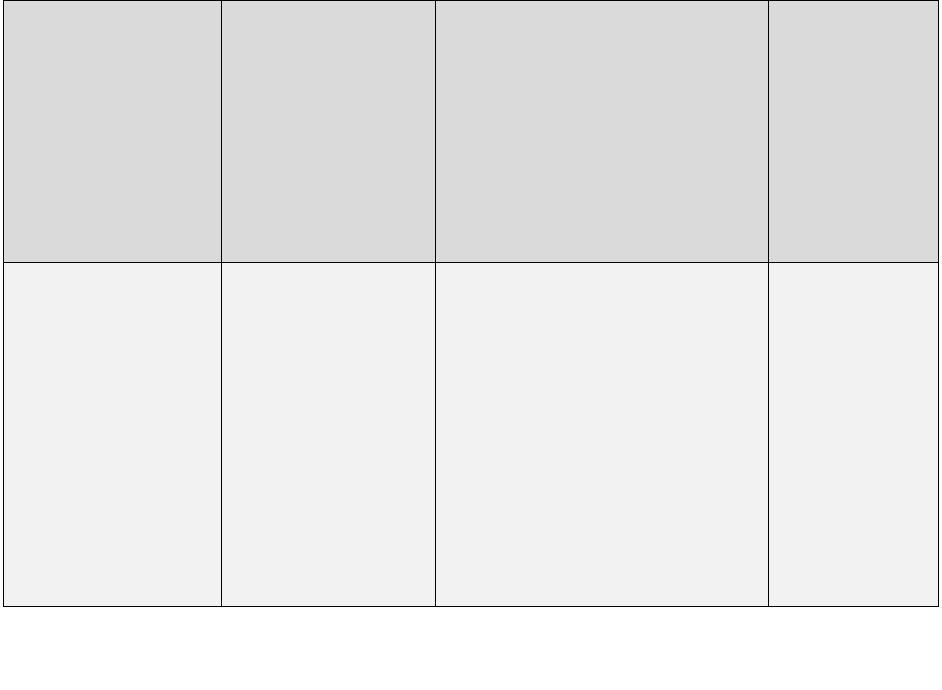

Table 2: At a Glance: Performance Management as Part of the Grants Lifecycle

34

Grant Phase

Description

Performance Activities

Activity Level

Phase 1: Program

Administration

Define the problem

to be solved and

the desired long-

term program

results, develop

NOFOs at the

project level, and

create merit review

process standards.

Conduct program-planning

activities; and establish program

goals, objectives, and

performance measures.

Link project goals to the larger

program, establish award

recipient responsibilities for

reporting performance

indicators, develop risk

reduction strategies, assess past

performance, and identify

independent sources of data

when appropriate.

1) Program

2) Project

Grant Phase

Description

Performance Activities

Activity Level

Phase 2: Pre-Award

Management

(See also 2 CFR 200

Subpart C—Pre-Federal

Award Requirements

and Contents of Federal

Awards)

Review

applications and

select recipients.

Notify approved

applicants of award

selection.

Evaluate and document

application eligibility and merit.

Evaluate and document

applicant risk based on past

performance, as applicable.

2) Project

3) Sub-project

Phase 3: Award

Management

(See also 2 CFR 200

Subpart C—Pre-Federal

Award Requirements

and Contents of Federal

Awards)

Award recipient

notification

Issue award notifications,

including special conditions to

address award recipient risks

and reporting on performance

3) Sub-project

33

Federal Integrated Business Framework (FIBF): https://ussm.gsa.gov/fibf-gm/ .

34

Table developed by authors of the PM Playbook.

The practices in the PM Playbook are shared informally for the purpose of peer to peer technical assistance, stakeholder engagement, and

dialogue. This document is not official OMB guidance, and is not intended for audit purposes. Implementation of the practices discussed may

differ by agency and applicable legal authority.

April 27, 2020 Page 17

Phase 4: Post-

Award Management

and Closeout

(See also 2 CFR 200

Subpart D—Post

Federal Award

Requirements)

Monitor and assess

award recipient

financial and

performance data.

Perform grant

closeout activities

Document and analyze award

recipient performance data,

notify award recipient of

concerns about performance,

and document corrective

actions, when needed. Review

and resolve audit findings, and

update recipient risk

assessments based on results.

3) Sub-Project

Phase 5: Program

Oversight

(See also 2 CFR 200

Subpart F—Audit

Requirements)

Program and

project-level

analysis and review

Report on program and project

level performance data and

related projects, including

whether the program and/or

project made progress toward

their goals and objectives;

utilize results to improve

projects in the next funding

cycle; develop and disseminate

lessons learned and promising

practices; and conduct

evaluations

1) Program

2) Project

The PM Playbook discuss these five phases in detail in Section III below:

III. The Performance Management Approach for Grants

The PM Playbook outlines a performance management approach for grants that aligns with the

FIBF and emphasizes the importance of the program design phase. While GPRAMA and OMB

Circular A-11 provide guidance to agencies on requirements related to strategic and performance

planning, reporting, and goal setting in an organizational context, there are fewer Federally

mandated policies and tools on program design, NOFO development, and performance

management for Federal awards. The PM Playbook addresses this gap by providing details on

promising practices used by Federal agencies at each of the five phases of the grants lifecycle

highlighted below.

During the grants lifecycle, Federal awarding agencies focus on both compliance and

performance activities. Most often, these activities are combined when grant managers and

others monitor award recipients. Too often, however, Federal awarding agencies do not clearly

distinguish between these types of activities. As a result, Federal awarding agencies may request

only compliance related measures in the NOFO, rather than both compliance and performance

The practices in the PM Playbook are shared informally for the purpose of peer to peer technical assistance, stakeholder engagement, and

dialogue. This document is not official OMB guidance, and is not intended for audit purposes. Implementation of the practices discussed may

differ by agency and applicable legal authority.

April 27, 2020 Page 18

related measures. Per 2 CFR Part 200, recipient must be informed of all reporting requirements,

including performance requirements, within NOFOs.

It is necessary to distinguish between these activities to ensure that 1) individual award recipients

comply with programmatic, financial, and performance requirements; and 2) program and

project results are advanced or successfully achieved based on their goals and objectives.

To assist in lessening this confusion, the PM playbook provides the following definitions:

Compliance Activities

35

: Compliance activities are the administrative, financial, audit, and

program requirements described in the NOFO and are used for recipient oversight and

monitoring, which conform with the Federal rules and regulations on reporting in 2 CFR Part

200. The primary purpose of compliance activities is to document that funds are spent in

accordance with the terms of the Federal award, including accomplishing the intended sub-

project purpose. Compliance activities take place at the sub-project (or individual award

recipient) level and include:

• Ensuring the timely expenditure of funds

• Preventing fraud, waste, and abuse

• Financial reporting

• Identifying the technical assistance needs of the award recipient

Performance Activities

36

: Performance activities include both performance measurement

(outputs and outcomes) and program/project evaluations. Evaluations may also include studies to

answer specific questions about how well an intervention is achieving its outcomes and why.

Many programs and projects entail a range of interventions in addition to other activities. For

example, specific interventions for a rural grant program might include an evaluation of different

types of intervention models.

• Performance measurement: Reporting on a program or project's progress toward and

accomplishment of its goals with performance indicators.

• Program/project evaluations: Conducting studies to answer specific questions about how

well a program or project is achieving its outcomes and why.

The intent of performance activities are to focus on assessing higher-level program and project

outcomes and results. The ideal and preferred performance measures are outcomes; however, for

some programs it may be difficult to collect outcome measures during the period of performance.

In these instances, agencies may need to collect output measures to monitor performance. These

35

Developed by the authors of the PM Playbook.

36

Developed by the authors of the PM Playbook.

The practices in the PM Playbook are shared informally for the purpose of peer to peer technical assistance, stakeholder engagement, and

dialogue. This document is not official OMB guidance, and is not intended for audit purposes. Implementation of the practices discussed may

differ by agency and applicable legal authority.

April 27, 2020 Page 19

output measures should be meaningful and consistent with the theory of change, maturity model,

or logic model documented during the program design phase described below. (See Table 1:

Output and Outcome Measures Defined). Examples of output measures include the number of

single parents that received home visits during the period of performance of an award or how

much of an infrastructure project was completed in a given timeframe. Examples of outcome

measures includes determining whether the single parent that received the home visit received

assistance that helped to improve their quality of life, or the percent reduction in substance abuse

relapse rates, or reduction of average commute time in a given metropolitan area.

See Figure 4: Compliance Activities versus Performance Activities.

37

III. A. Phase 1: Program Administration

38

The grants lifecycle begins with the enactment of an authorizing statute, which prompts an

agency to set-up and design the administration of the grant program, which focuses on planning

and creating assistance listings and related projects (i.e., NOFOs). Sound program design is an

essential component of performance management and program administration. Ideally, program

design takes place before an agency drafts related projects. This enables Federal agency

leadership and employees to codify program goals, objectives, and intended results before

specifying the goals and objectives of specific projects in a NOFO.

37

Figure developed by authors of the PM Playbook.

38

Refer to the OMB Uniform Guidance (2 CFR 200) for additional information: https://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-

bin/retrieveECFR?gp=&SID=c5f8c20480c04403862fca0bcaf78a74&mc=true&n=pt2.1.200&r=PART&ty=HTML#

_top

The practices in the PM Playbook are shared informally for the purpose of peer to peer technical assistance, stakeholder engagement, and

dialogue. This document is not official OMB guidance, and is not intended for audit purposes. Implementation of the practices discussed may

differ by agency and applicable legal authority.

April 27, 2020 Page 20

Program design begins with aligning program goals and objectives with Congressional intent as

stated in the program authorization and appropriations bill language. The program goals and

objectives should also be aligned with Federal agency leadership priorities, strategic plans and

priority goals. A well-designed program has clear goals and objectives that facilitate the delivery

of meaningful results, whether a new scientific discovery, positive impact on citizen’s daily life,

or improvement of the Nation’s infrastructure. Well-designed programs also represent a critical

component of an agency’s implementation strategies and efforts that contribute to and support

the longer-term outcomes of an agency’s strategic plan.

Program Design is Critical to Achieving Results

Program design occurs before a project is developed and described in a NOFO. Ideally, an

agency first designs the program (or assistance listing), including specifying goals, objectives,

and intended results, before developing one or more projects (NOFOs) under the program.

Consider the following metaphor: In some instances, a program is like an aircraft carrier, and

the projects are like the planes onboard the ship. The carrier has macro-level, mission goals

and each plane carries out micro-level goals and objectives based on their specific

assignments.

Agencies may also use program design principles when developing projects. In fact, the steps for

project development are the same as program development with the addition of steps: 1) aligning

the goals and objectives of the project back to those of the larger program; and 2) including

project-specific performance indicators in the NOFO. Thus, program design activities may occur

at both the program and project levels.

39

39

The PM Playbook authors note that performance requirements may vary by type of Federal financial assistance.

Formula awards are noncompetitive and based on a predetermined formula. They are governed by statutes or

Congressional appropriations acts that specify what factors are used to determine eligibility, how the funds will be

allocated among eligible recipients, the method by which an applicant must demonstrate its eligibility for funding,

and sometimes even performance reporting requirements. Discretionary awards, however, are typically provided

through a competitive process. They also are awarded based on legislative and regulatory requirements, but agencies

typically have more discretion over specifying program and performance requirements for award recipients.

The practices in the PM Playbook are shared informally for the purpose of peer to peer technical assistance, stakeholder engagement, and

dialogue. This document is not official OMB guidance, and is not intended for audit purposes. Implementation of the practices discussed may

differ by agency and applicable legal authority.

April 27, 2020 Page 21

Table 3: Program/Project Design - Activity Levels

40

Level 1: Program

Federal awarding agencies establish program

goals, objectives, and intended results that

align with appropriations, which are described

for each assistance listing on beta.sam.gov.

Level 2: Project

Federal awarding agencies establish project

goals, objectives, and intended results (that

align with the larger program), which are

described in a NOFO.

The steps involved in program and project design take place before agencies write NOFOs and

include:

1. Developing a problem statement with complexity awareness.

41

2. Identifying goals and objectives.

3. Developing a theory of change, maturity model, and/or logic model depicting the

program or project’s structure.

42

4. Developing performance indicators, as appropriate, to measure the program and/or

project results, which may include independently available sources of data.

5. Identifying stakeholders that may benefit from promising practices, discoveries, or

expanded knowledge.

6. Research existing programs that address similar problems for information on previous

challenges and successes.

7. Develop an evaluation strategy (See Section IV.E.3 on Evaluations for more

information).

40

Table developed by authors of the PM Playbook.

41

The phrase “complexity awareness” is often used in research but is applicable in many situations. Complexity-

awareness acknowledges the prevalence and importance of non-linear, unpredictable interrelationships, non-linear

causality and emergent properties that may impact a problem.

42

See glossary for definitions of these phrases.

The practices in the PM Playbook are shared informally for the purpose of peer to peer technical assistance, stakeholder engagement, and

dialogue. This document is not official OMB guidance, and is not intended for audit purposes. Implementation of the practices discussed may

differ by agency and applicable legal authority.

April 27, 2020 Page 22

Promising Practice - Program and Project Design, Monitoring, and Evaluation Policy

In 2017, the Department of State issued a “Program and Project Design, Monitoring, and

Evaluation Policy” to establish clear links from its strategic plan goals, to achieve those goals

through key programs and projects, and to collect data on whether these efforts were working

as intended. The policy clearly defines the terms program and project as follows:

Program: A set of activities, processes, aimed at achieving a goal or objective that is

typically implemented by several parties over a specified period of time and may cut

across sectors, themes, and/or geographic areas.

Project: A set of activities intended to achieve a defined product, service, or result with

specified resources within a set schedule. Multiple projects often make up the portfolio

of a program and support achieving a goal or objective.

According to the State Department, program and project design work serves as a foundation

for the collection and validation of performance monitoring data, confirming alignment to

strategic objectives, and purposeful evaluative and learning questions. The State Department

developed guidance and a plan for implementing the policy. This plan included coordination

with bureaus and offices throughout the agency to complete program and project design steps

for their major lines of effort.

Bureaus that could integrate sound program design, monitoring, and evaluation practices did

so either with:

• A well-resourced effort with strong leadership buy-in, or

• With a bureau champion who was able to convince colleagues that well-

documented program designs, monitoring plans, and progress reviews could

improve the efficiency and efficacy of their work and their ability to answer

questions from stakeholders.

Implementation brought additional benefits, including broader collaboration among bureaus

and missions and greater connectivity among the sources of information on planning,

budgeting, managing and evaluating projects and programs.

The practices in the PM Playbook are shared informally for the purpose of peer to peer technical assistance, stakeholder engagement, and

dialogue. This document is not official OMB guidance, and is not intended for audit purposes. Implementation of the practices discussed may

differ by agency and applicable legal authority.

April 27, 2020 Page 23

III.A.1 Program Design Steps

As noted previously, Federal agencies can focus on program design at both the assistance listing

and the project level. Federal agencies often design programs with multiple projects. While the

steps outlined below focus on programs, the same steps can be applied to project development.

Step 1. Develop a problem statement. Program design begins with understanding

Congressional intent in authorizing and appropriations language, the priorities of agency

leadership, and/or the lessons learned from previous programs and projects. This understanding

informs the purpose of a program and/or project and guides its design.

43

Align Program Purpose with Authorization Language

The Department of Transportation’s Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA)

mission is to improve commercial motor vehicle (CMV) carrier and driver safety through the

administration of Federal award programs. The purpose of FMSCA’s Motor Carrier and

Safety Assistance Program (MSCAP) is to reduce CMV-involved crashes, fatalities, and

injuries through consistent, uniform, and effective CMV safety programs (assistance listing

#20.218), which is consistent with the program’s authorization under the Safe, Accountable,

Flexible, Efficient Transportation Equity Act.

44

After the intent of the program is understood, a problem statement is developed. The problem

statement clearly defines the nature and extent of the problem to be addressed. Agencies may

develop problem (or need) statements by conducting a situational analysis or needs assessment,

which may include internal and external stakeholder engagement. This involves a systematic

gathering and analysis of data and information relevant to the program the problem seeks to

address and identifying priorities, concerns, and perspectives of those with an interest in the

problem or addressed need. During this step, evidence is gathered (if available) to help inform

the successful ways to advance or achieve the program’s goals. If it is unclear if evidence exists

on the program, the program should consult with the agency evaluation officer (EO) or chief data

officer (CDO). The data and evidence gathered will help to inform both program and project

development.

43

As noted previously, the PM Playbook begins the program design process at the assistance listing level (not at the

project or NOFO level). However, using the “program design” process at the NOFO level can be extremely useful,

especially when new programs and their corresponding projects are developed.

44

Pub. L. No.109–59, § 4107(b), 119 Stat. 1144, 1720 (2005), amended by SAFETEA-LU Technical Corrections

Act of 2008, Pub. L. 110-244, 122 Stat. 1572 (2008).

The practices in the PM Playbook are shared informally for the purpose of peer to peer technical assistance, stakeholder engagement, and

dialogue. This document is not official OMB guidance, and is not intended for audit purposes. Implementation of the practices discussed may

differ by agency and applicable legal authority.

April 27, 2020 Page 24

Promising Practice – Consultation with Experts to Improve Program Design

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s (NASA) Science Mission Directorate

(SMD) uses NASA's Strategic Goals and Objectives and the high-level objectives that flow

from them as one of four components to its research grant program design activities. In turn,

the high-level objectives are derived from “Decadal Surveys” created by the National

Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine every ten years and reviewed every five

years — reports summarizing the state of the art of SMD’s four science foci (Heliophysics,

Earth Science, Planetary Science, and Astrophysics) and containing recommendations for

future work.

45

The NASA Advisory Council’s Science Committee, a high-level standing committee of

the NASA Advisory Council (NAC), supports the advisory needs of the NASA Administrator,

SMD, and other NASA Mission Directorates. The NAC’s Science Committee is the third

design component. This committee provides input to NASA’s Earth and Space science-related

discretionary research grant programs, large flight missions, NASA facilities, etc.

Finally, the SMD contracts with the Space Studies Board (SSB) at the National Academies of

Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine to engage the Nation’s science expert stakeholders to

identify and prioritize leading-edge scientific questions and the observations required to

answer them as the fourth component. The SSB’s evidence-based consensus studies examine

key questions posed by NASA and other U.S. government agencies.

SMD integrates these design practices to create an evidence-based feedback system. For

example, Decadal Surveys inform the NASA’s strategic and SMD science plan production and

allow grant programs to be kept up to date rather than be completely reliant on agency

produced program goals and objectives.

Step 2. Identify goals and objectives. Goals establish the direction and focus of a program and

serve as the foundation for developing program objectives. They are broad statements about what

should happen because of the program, although the program may not achieve the long-term

result(s) within the period of performance for the program. When establishing program goal(s),

state the goal(s) clearly, avoid vague statements that lack criteria for evaluating program

effectiveness, and phrase the goal(s) in terms of the change the program should advance and/or

achieve, rather than as an activity or summary of the services or products the program will

provide.

Objectives are the intermediate effects or results the program can achieve towards advancing

program goal(s). They are statements of the condition(s) or state(s) the program expects to

achieve or affect within the timeframe and resources of the program. High-quality objectives

45

See NASA’s example to Improve Program Design at https://science.nasa.gov/about-us/science-strategy.

The practices in the PM Playbook are shared informally for the purpose of peer to peer technical assistance, stakeholder engagement, and

dialogue. This document is not official OMB guidance, and is not intended for audit purposes. Implementation of the practices discussed may

differ by agency and applicable legal authority.

April 27, 2020 Page 25

often incorporate SMART principles: Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-

bound.

46

SMART objectives help to identify elements of the evaluation plan and performance

management framework, including performance indicators and data collection criteria. Program

objectives often serve as the starting point for developing projects and drafting the related

NOFOs. While there is no one right way to design programs and related projects, agencies

cannot assess program and project success if their goals and objective are not clearly stated from

the beginning.

Step 3. Develop a theory of change, maturity model, or logic model depicting the program's

structure. Logic models, maturity models, and theories of change are the building blocks for

developing programs. They may be used individually or together. For example, a theory of

change defines a cause-and-effect relationship between a specific intervention, or service

activity, and an intended outcome.

47

A theory of change explains how and why a program is

expected to produce a desired result. A theory of change also can be used to summarize why

changes in a logic model are expected to occur, and logic models can be used to show a

summary of the underlying theory.

48

A maturity model is a tool that is used to assess the effectiveness of a program. The maturity

model is also used to determine the capabilities that are needed to improve performance. While

maturity models are often used as a project management tool, they also can help to assess a

program and/or project’s need for improvement.

49

Logic models describe how programs are linked to the results the program is expected to

advance or achieve. Logic models are intended to identify problems (in the problem statement),

name desired results (in the goals and objectives) and develop strategies for achieving results.

Outcomes are the primary changes that are expected to occur as a result of the program or

project’s activities, and are linked to the program or project goals and objectives.

50

Logic models provide a visual representation of the causal relationships between a sequence of

related events, connecting the need for a planned program or project with desired results. Logic

models identify strategic elements (e.g., inputs, outputs, activities, and outcomes) and their

relationships. This also includes statements about the assumptions and external risks that may

influence success or present challenges.

46

For more information on SMART goals: https://hr.wayne.edu/leads/phase1/smart-objectives

47

More information about Theory of Change: https://www.nationalservice.gov/resources/performance-

measurement/theory-change

48

More information about Theory of Change: https://www.theoryofchange.org/what-is-theory-of-change/

49

https://www.pmi.org/learning/library/maturity-model-implementation-case-study-8882

50

See glossary for definition of “outcome.”

The practices in the PM Playbook are shared informally for the purpose of peer to peer technical assistance, stakeholder engagement, and

dialogue. This document is not official OMB guidance, and is not intended for audit purposes. Implementation of the practices discussed may

differ by agency and applicable legal authority.

April 27, 2020 Page 26

Logic models also include program activities. These are proposed approaches to produce results

that meet the stated goals and objectives. A clear description of program activities provides the

basis for developing procedures for program implementation and measures to monitor

progress/status.

A well-built logic model is a powerful communications tool. Logic models show what a program

is doing (activities) and what the program plans to advance or achieve (goals and outcomes).

Logic models also communicate how a program is relevant (needs statement) and its intended

impact (outcomes). Agencies also may create cascading logic models, where the program

(assistance listing) logic model informs the development of logic models for individual projects

(NOFOs).

Promising Practice – Establishment of Program Design Process

The Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA), in the Department of Justice’s Office of Justice

Programs, developed an extensive program design process to assist its grant, performance, and

policy managers in developing goals and objectives, deliverables, logic models, and

performance indicators. The process includes a program design manual, which provides

information on how to facilitate the process and worksheets for creating program statements,

including a theory of change; logic models; and performance indicators. BJA’s program

design process has been successful in helping employees work toward a common

understanding of a program’s purpose, goals, objectives, and intended results. The process has

also helped employees develop projects (NOFOs) that align with the goals and objectives of

the larger program. The same process has been used to develop better projects and design

NOFOs.

Step 4. Develop performance indicators to measure program and/or project

accomplishments. Performance indicators should provide strategic and relevant information that

answer agency leadership and stakeholders’ questions. They should measure the results of the

actions that help to advance or achieve the program’s goals and objectives. While there is no

specific formula for developing performance indicators, characteristics of effective indicators

include the following:

Reflect results, not the activities used to produce results

Relate directly to a goal

Are based on measurable data

Are practical and easily understood by all

Are accepted and have owners

51

51

A performance indicator owner is the person responsible for the process that the indicator is assessing.

The practices in the PM Playbook are shared informally for the purpose of peer to peer technical assistance, stakeholder engagement, and

dialogue. This document is not official OMB guidance, and is not intended for audit purposes. Implementation of the practices discussed may

differ by agency and applicable legal authority.

April 27, 2020 Page 27

Step 5: Identify stakeholders that may benefit from any promising practices, discoveries, or

expanded knowledge.

Involving stakeholders early in the process helps establish buy-in before the project begins. It is

also important to build strong, ongoing partnerships with stakeholders that are in some way

seeking the same outcome to determine what may be missing from the program design.

Step 6: Research existing programs that address similar problems for information on

previous challenges and successes.

Program design can be much improved by researching challenges and successes of similar

programs. One possible source to research these challenges and successes is an agency

evaluation clearinghouse. See section III.E.2, Dissemination of Lessons Learned for an example

of the Department of Education’s “What Works Clearinghouse.” This clearinghouse was

designed with the goal to provide educators with the information that they need to make

evidence-based decisions.

Step 7: Develop an evaluation strategy

When designing a program, an evaluation plan may also be developed at the Program Design

phase. See Section III.E.3 Evaluation for more information.

III.A.2 Notice of Funding Opportunity (NOFO)

Per Appendix I, Full Text of the Notices of Funding Opportunity, of the OMB Uniform

Guidance located at 2 CFR 200, the pre-award phase includes: 1) developing NOFOs; 2)

establishing performance requirements for award recipients; and 3) establishing the merit review

process and criteria for ranking applicants.

The practices in the PM Playbook are shared informally for the purpose of peer to peer technical assistance, stakeholder engagement, and

dialogue. This document is not official OMB guidance, and is not intended for audit purposes. Implementation of the practices discussed may

differ by agency and applicable legal authority.

April 27, 2020 Page 28

Note on Terminology – What is a sub-project?

NOFO’s may use terms like “initiative,” “program,” or “project” to refer to the activities that an

award recipient plans to accomplish with their award. To avoid confusion, the PM Playbook

uses the phrase “sub-project” to refer to these activities. As noted previously, the PM Playbook

uses the term “project” to refer to the activities specified in a NOFO. See Figure 1: DOJ SCA

Example: Program, Project, Funding Vehicle and Recipient Relationships

III.B.1. Notice of Funding Opportunity (NOFO) (2 CFR 200, Appendix I)

The pre-award phase begins with reviewing a program’s goals and objectives as well as its logic

or maturity model. At this point, an agency may decide to fund one or more projects (NOFOs)

under the larger program. When developing NOFOs, grant managers and others should align the

goals, objectives, and performance indicators of the proposed project directly back to the larger

goals of the program. Agency leadership should review the program goals, objectives, activities,

and outcomes to determine which specific areas and/or activities the NOFOs will address. As

noted earlier, NOFO development is a project activity (level 2), and may mirror the process used

for developing a program.

Projects are funded through a NOFO

The process of developing a NOFO begins with aligning the goals and objectives of the

project funded in a NOFO with the larger goals of the program developed during the program

design process. NOFOs often have similar but more specific goals and objectives that

align with the activities and outcomes captured in the program logic model. For example,

the Department of Justice’s Second Chance Act (SCA) program has broader goals than those

for the SCA Comprehensive Community-based Adult Reentry Program.

SCA program (assistance listing) goal: Reduce recidivism

SCA Comprehensive Community-based Adult Reentry project (NOFO) sub-goal:

Increase the availability of reentry services with comprehensive case management

plans that directly address criminal behaviors.

The purpose of the NOFO should seek to contribute to advancing and/or achieving the

overarching program goal as well as the project’s goals and objectives. Ideally, a project

addresses one or more of the program’s objectives (which are the means by which the program

goal(s) is/are advanced or achieved). During NOFO development, Federal programs develop

clear instructions on the types of performance indicators that award recipients must develop and

report on for their project. This process may include requiring potential award recipients to

include proposed target numbers as the baseline data for key performance indicators in their

applications. As each program’s objectives have their own set of performance indicators, the

project should include the subset of indicators and data collection criteria associated with the

program objective. A NOFO may include program as well as project specific indicators, and

The practices in the PM Playbook are shared informally for the purpose of peer to peer technical assistance, stakeholder engagement, and

dialogue. This document is not official OMB guidance, and is not intended for audit purposes. Implementation of the practices discussed may

differ by agency and applicable legal authority.

April 27, 2020 Page 29

should include a description of requirements needed to monitor compliance and outcomes for

assessing program results.

Appendix 1 of 2 CFR 200 - Full Text of Notice of Funding Opportunity

52

2 CFR 200 requires that all NOFO’s include the following sections:

A. Program Description

The program description may be as long as needed to adequately communicate to

potential applicants the areas in which funding may be provided. This section includes

many items, including the communication of indicators of successful projects.

B. Federal Award Information

Information contained in this section helps the applicant make an informed decision about

whether to submit a proposal.

C. Eligibility Information

Considerations or factors that determine applicant or application eligibility are included