SE ARCHING FOR

SUSTAINABILITY

FOREST POLICIES, SMALLHOLDERS,

AND THE TRANS-AMAZON H IGHWAY

It is a powerful and disturbing image: loggers driving roads deep into the forest

to remove a few mahogany trees, with slash-and-burn settlers following closely

on their heels. However, it no longer captures the whole picture of logging in the

Brazilian Amazon. So, then, what is the role of logging in the impoverishment or

potential conservation of the Amazon rainforest? The answer to this question is

deceptively complex: To achieve a sustainable future in Amazon forestry, policy-

makers and stakeholders must understand the physical, economic and political

dimensions of competing land use options and economic interests. They must pro-

vide effective governance for multiple agendas that require individual oversight.

For simplicity’s sake, suppose that forest governance can be approached from

two angles: a preservation approach in which the land is tucked away, never to

be used again; and a “use-it-or-lose-it” approach in which a well-managed forest

by Eirivelthon Lima, Frank Merry, Daniel Nepstad, Gregory Amacher,

Cláudia Azevedo-Ramos, Paul Lefebvre, and Felipe Resque Jr.

This article was published in the January/February 2006 issue

of Environment. Volume 48, Number 1, pages 26–38.

© Heldref Publications, 2006. http://www.heldref.org/env.php

SUSTAINABILITY

AND THE TRANS-AMAZON H IGHWAY

© DYLAN GARCIA—PETER ARNOLD, INC.

28 ENVI RON M ENT VOLU ME 48 N U M BE R 1

estate becomes part of a sustainable eco-

nomic development scenario and com-

petes successfully with other land use

options. In fact, 28 percent of the Brazil-

ian Amazon is already listed as some form

of park, or as a protected or indigenous

area.

1

But what of the forest without

protection, found mainly on private lands

or on as-yet undesignated government

lands? For many, selective logging of

these forests is a form of forest impover-

ishment that is only slightly less devastat-

ing than forest clear-cutting.

2

For others,

the selective harvest of timber is the best

way to make the long-term protection of

standing forests economically and politi-

cally viable.

3

Opponents base their argument on two

points: The long-term selective logging

of primary tropical forest is financially

impracticable, and selective logging is

the first step in a vicious cycle of degra-

dation that includes settlement and land

clearing.

4

Advocates say that selective

logging, when done well (called “reduced

impact logging”), is renewable, economi-

cally viable, and may provide an impor-

tant stream of revenue for government and

private landowners that would encourage

the maintenance of forest cover.

5

These

proponents contend that if tropical forestry

is to compete successfully with other land

use options and essentially push back

against the encroaching line of deforesta-

tion, some conditions must be met: the

removal of subsidies to other land use

options; the breakdown of barriers to

entry, such as complex forest management

plans; the dissemination of information

on forestry to all potential market par-

ticipants; and the elimination of perverse

incentives for deforestation—in particular

the establishment of land titles through

clearing to demonstrate active use. Fur-

thermore, if forestry is deemed the least

cost approach to maintaining forest cover

outside parks and protected areas, then

subsidies to forest management activities

might also be appropriate.

There are vast forested areas in the Bra-

zilian Amazon located outside parks and

protected areas, and a multitude of land-

owners, including state and federal gov-

ernments, are controlling that forest. As a

result, policies to manage forest resources

must necessarily be comprehensive, flexi-

ble, and appropriate to varying conditions

and agents. The Brazilian government has

recently identified, and is now beginning

to implement, a strategy of timber conces-

sions that should help to corral some part

of the industry into a controlled region.

This should make it easier to monitor and

will hopefully reduce illegal logging. The

policy, however, mostly ignores the sticky

issue of forestry on private land, which,

although complex, could provide the

engine for sustainable economic develop-

ment among the disenfranchised settlers

of the Amazon frontiers. The settlers may

straggle onto the frontier individually,

but they eventually form communities,

control large areas of land, and become

an increasingly important component of

the timber industry.

A major economic corridor in the

Brazilian Amazon—the Trans-Amazon

Highway—illustrates how logging can

be transformed from a force driving for-

est impoverishment to one driving forest

conservation, and how this transition, in

turn, carries important potential benefits

for the semi-subsistence farmers who live

along this corridor. To fully describe this

transformation, it is necessary to place it

in light of the history and current context

of the timber industry of the Amazon, and

with the understanding that the complex-

ity inherent in the largest and most diverse

tropical forest in the world makes forest

governance a mighty task.

A Brief History of the

Amazon Timber Industry

Understanding logging along the Trans-

Amazon Highway depends upon the his-

torical context of the timber industry

in the Amazon, which can be roughly

divided into three periods (see Figure 1

on page 29).

6

The early production period

lasted from the 1950s to the early 1970s

and was followed by a transition or boom

period, which lasted from the mid 1970s

Timber will always be one of the Amazon’s most important exports. Will the industry

have a sustainable future for loggers as well as smallholders?

© ADRIAN ARBIB—CORBIS

JAN UARY/ FEB RUARY 2006 ENVI RON M ENT 29

to the late 1980s. A third period, indus-

try consolidation and migration to new

frontiers, started in the early 1990s but is

now coming to an end. The current timber

industry is in such disarray from political

mismanagement that in October 2005 the

federal police temporarily suspended the

transport of all logs from the Amazon.

Early Days

(1950s to mid-1970s)

In the 1950s, the island region of

the Amazon delta in the state of Pará

was the center of the wood industry in

the Amazon. Through the 1960s, there

were three large plywood mills and six

large sawmills that controlled produc-

tion. With no connection to the large

domestic markets of southeastern Brazil

and the dependence on fluvial transport

to access raw materials and deliver prod-

ucts, these mills produced only for the

export market. Limited shipping capacity

and irregular delivery schedules hindered

sales to ports in northeastern Brazil,

which could be reached by ship along

the Atlantic coast. The primary source of

raw material was smallscale landowners

who sold logs along the banks of rivers.

The environmental impact of logging

was minimal, as timber extraction was

an integrated part of diverse smallscale

family farming systems on the Amazon

River floodplain. The two popular tree

species harvested were Virola (Virola

surinamensis) for plywood and Andiroba

(Carapa guianensis) for sawnwood (the

first stage of the log processing sequence

in which logs are cut into boards, but

not planed).

In the early and mid-1970s, a number

of smaller sawmills began to appear in

the island region and farther up along the

upper Amazon River. Into the mid-1970s,

the Amazon remained disconnected from

domestic markets but the export market

flourished. Estimated log consumption

was in the region of 2.5 million cubic

meters per year—all harvested by axe.

Early reports on timber production in

the Brazilian Amazon suggest this was

a period of poor market access, poor

quality of laborers, obsolete equipment,

insufficient knowledge of local tree spe-

cies, and scarce information on prices

and markets for products.

7

Transition Period

(Late 1970s to Early 1990s)

A period of dramatic transition in the

timber sector began in the late 1970s

to early 1980s. Several highways were

completed to link the Amazon to domes-

tic southeastern and northeastern Brazil-

ian markets. The states of Rondônia,

Mato Grosso, and Pará became connected

through the BR364, BR163, and BR010

highways. Large public investment pro-

grams for the construction of dams, hydro-

power plants, a railroad for the Carajás

mining program, and the settlement of

migrants from southern and northeastern

Brazil changed the interfluvial forests of

the Amazon, passively protected until that

time by their inaccessibility.

Figure 1. Logging the Amazon

SOURCE: Woods Hole Research Center, with data from Instituto

Brasiliera de Geografia e Estatistica, Instituto Socioambiental, Instituto

de Pesquisa Ambiental da Amazônia, Universidade de Minas Gerais.

NOTE: The area along the Amazon River was first logged during the

1950s to 1970s. During the 1980s and 1990s, improved infrastructure

and government policies encouraged logging on the “old” frontier, which

mirrors the so-called “arc of deforestation.” As the stock declined on the

old frontiers, firms have migrated west along the roads into the new

frontiers. The map also shows the coverage of parks and protected areas

of all types in the Amazon, including newly created parks.

Atlantic

Ocean

Pacifi c

Ocean

Protected area

New forest reserve

Potential new reserve

Island region

Old frontier

New frontier

30 ENVI RON M ENT VOLU ME 48 N U M BE R 1

Deforestation during this time was

largely a response to government actions

that either directly promoted or enabled

land conversion from forests to other

uses. The number and size of sawmills

increased in response to the inexpensive

primary resource and newly accessible

markets, growing local demand, and the

availability of cheap labor. Mechanization

of harvesting, transport, and processing

also contributed to the growth of sawn-

wood output.

By the early 1980s, Paragominas (a

city in Pará) became the most important

mill center in the Amazon, producing

mostly for the domestic market. The state

of Mato Grosso also produced lumber

for the domestic market, with important

logging centers appearing in the towns of

Sinop and Alta Floresta. Meanwhile, the

island region continued to produce for the

export market. In all, the transition period

during the 1970s and mid-to-late 1980s

was a turning point in the timber industry

of the Brazilian Amazon.

Consolidation and Migration

(mid-1990s to 2000s)

After the transition period, another (less

dramatic) period of consolidation and

expansion ensued along old and new log-

ging frontiers.

8

Old frontiers can now be

found in eastern Pará (Paragominas and

Tailandia) and in northern Mato Grosso

(Sinop). In these areas, virgin forests have

become increasingly scarce, and the log-

ging industry became more diverse and

efficient. The more inefficient logging

firms exited the market, and those that

remained became vertically integrated in

an effort to capture value added in down-

stream processing.

Access to the old frontiers is gener-

ally good given the high density of paved

roads. In contrast, new frontiers are char-

acterized by a rapid inflow of mills and

producers from the old frontier, poor

government regulation, and high transport

costs. The notable new logging frontier is

in western Pará along the northern sec-

tion of the Santarém-Cuiaba Highway,

the BR163.

The Industry Today

The current volume of wood produced

in the Legal Amazon is between 20 and

30 million cubic meters, of which more

than 50 percent is sold in the domestic

Brazilian market.

9

Prior to 2003, legal

timber harvest was possible through the

preparation of a forest management plan

submitted to the government agency and

approved with a temporary land title. All

that was required by IBAMA, the Brazil-

ian government environmental agency,

was proof that a firm or individual had

initiated a land legalization process with

Brazilian land titling institutions such as

the Institute of Colonization and Agrar-

ian Reform (INCRA).

10

Generally, land

titling procedures took years, and they

did not always result in legalization. By

the time the land titling institution had

made its decision, the harvest was already

complete and the loggers had moved on to

the next native forest stocks.

In 2003, the Brazilian government abrupt-

ly decided that management plans could no

longer be approved on lands where prop-

erty rights were not well established. That

year, nearly all forest management plans

were rejected.

11

The government, however,

did not have an alternative readily available

for the nearly 2,500 logging companies

based in the Amazon, and an unintended

side effect of the policy has been that

more companies now simply operate ille-

gally in such areas. Conflicts, protests, and

widespread unregistered logging are now

the norm.

To solve the problem of legalizing

timber harvest and controlling the timber

industry, the Brazilian government has

proposed implementing forest concessions

on public lands.

12

While this approach has

some merit, and indeed has been debated

extensively in the Brazilian public arena,

large concessions controlled by a few

companies may not be the best economic

option in the regions where smallholders

and other private landowners, including a

large number of migrant settlers, are the

predominant land users.

13

The Case of the

Trans-Amazon Highway

For two weeks in August 2003, the

Trans-Amazon Highway was impassable:

Angry loggers had blocked the road,

Sawmill technology in the Amazon (such as the bandsaw shown here) has not changed

much since the 1950s. Efficiency is between 30 and 40 percent yield from log to boards.

© IPAM

JAN UARY/ FEB RUARY 2006 ENVI RON M ENT 31

stopping traffic to protest a government-

imposed timber shortage. A similar dis-

play occurred outside the town of San-

tarém, Pará, in January 2005 and recently

on the BR163 Highway in western Pará.

Tragically, access to timber was also one

of the underlying reasons for the murder

of Sister Dorothy Stang in the munici-

pality of Anapú.

14

Timber scarcity is a

startling concept for the Amazon. How is

it that a resource so apparently abundant

can be the root cause of violent conflicts

and protests?

15

The answer lies partially

in the sudden requirement by the Bra-

zilian government that loggers provide

proper legal documentation for land rights

in areas where logs are extracted. But

who owns the forests and logs along this

frontier highway?

Built by General Emílio Garrastazu

Médici (president of Brazil from 1969–

1974), the main part of the Trans-Amazon

Highway stretches approximately 1,000

kilometers from the town of Marabá to

Itaituba on the banks of the Tapajós

River.

16

The highway is largely unpaved

and virtually impassable for four months

of the year during the rainy season. Home-

steaders are usually allocated demarcated

lots of 100 hectares apiece (approxi-

mately 250 acres) and then often battle

the elements and wealthy land speculators

to continue occupying the land.

17

Still,

migration to the region is relentless, as

a constant stream of formal and infor-

mal land control followed early coloniza-

tion projects in the late 1970s.

18

INCRA,

the federal land settlement agency, has

formally settled approximately 30,000

families and an unknown number of

informal squatters.

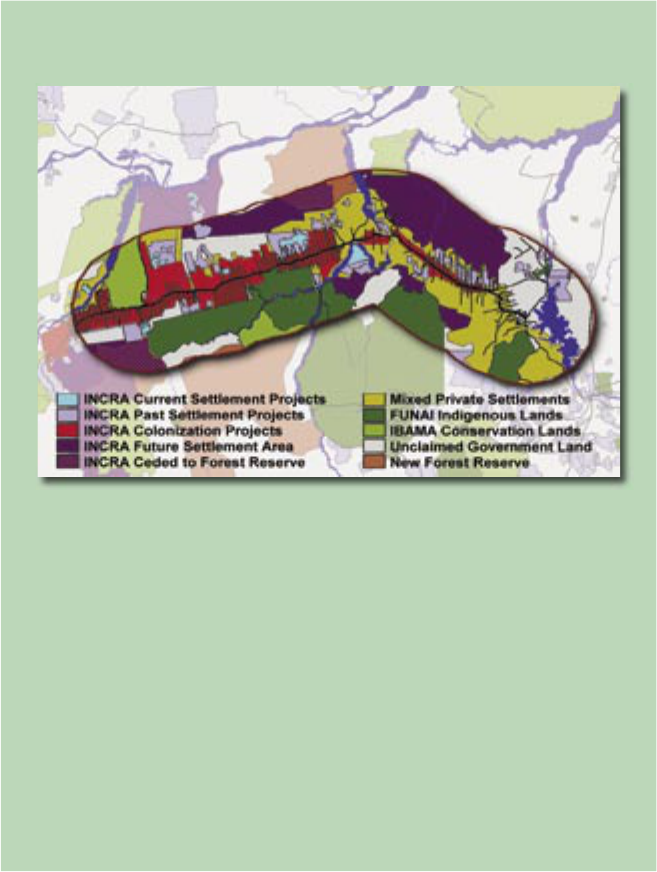

While it is commonly accepted that

smallholders control vast areas of land

along the Trans-Amazon Highway, the

exact quantity of land is debatable. This

question is taken up under the auspices

of the Green Highways Project, an inter-

national multi-institutional project, led by

the Brazilian nongovernmental organiza-

tion Instituto de Pesquisa Ambiental da

Amazônia (IPAM, Amazon Institute of

Environmental Research) with the sup-

port of the Massachusetts-based Woods

Hole Research Center (WHRC) (see Fig-

ure 2 on this page).

19

An area 100 kilo-

meters (km) on either side of the Trans-

Amazon Highway from the municipality

of Itupiranga to Placas was mapped using

satellite imagery and secondary data from

Brazilian government sources. Land dis-

tribution was mapped and deforestation

measured using 30-meter spatial resolu-

tion satellite images and secondary data

from INCRA and the Brazilian Institute of

Geography and Statistics (IBGE).

20

Imag-

es were classified into forest and non-

forest classes by supervised classification

and visual interpretation.

21

The objective

was to identify where smallholders are

located and where they will be located in

the future.

Of the total 15.7 million hectares locat-

ed within this buffer, 7.9 million are

under the control of or are promised to

smallholders. Of the total area within the

100-km study area, the land distribution

is: 1.1 percent in demarcated settlements,

5.4 percent in current settlements, 11.4

percent as squatters (posseiros), 13.2 per-

cent in old colonization projects, and 19.5

percent destined for future settlements

by INCRA. Four percent of the land is in

conservation areas, 7.6 percent in infor-

mal medium and large-scale land hold-

ings, 15.4 percent in indigenous reserves,

Figure 2. The Trans-Amazon Highway

NOTE: Built in the 1970s, the highway stretches more than 3,000 km

through the Amazon forest. It is mostly dirt and virtually impassable for

much of the wet season (January to June). The study area, a 100-km zone

between the towns of Marabá and Itaituba, is shown in the shaded region.

The area in green is the “Legal Amazon” of Brazil.

SOURCE: Woods Hole Research Center.

Atlantic

Ocean

Pacifi c

Ocean

32 ENVI RON M ENT VOLU ME 48 N U M BE R 1

and a final 21.2 percent is unclaimed gov-

ernment land.

22

The number of smallhold-

ers currently residing in the 100-km zone

was estimated by summing the area with

active settlements, which includes current

settlements, colonization, and squatters,

and then dividing by an 82.6- hectare

average lot size from survey results (see

below), giving a total area of approxi-

mately 4.7 million hectares held by 57,000

smallholder families (see Figures 3 and 4

on this page and page 33).

Given the observed distribution of

smallholders from the spatial analysis, the

next logical question for the Green High-

ways Project was whether these agents

could potentially supply the timber indus-

try with wood. Demand for timber in the

area is strong; the demand for logs on

the Trans-Amazon Highway more than

doubled over 12 years, increasing from

roughly 340,000 cubic meters in 1990 to

approximately 840,000 cubic meters in

2002. To determine whether smallholders

can provide this quantity it is important to

first estimate the growing stock potential

of the forest held by smallholders, assum-

ing that smallholders will in fact sell wood

(this assumption will be revisited below).

Using conservative (high) deforestation

assumptions (for example, a range of 60

percent deforested for old colonization

areas to 15 percent deforested for INCRA

land allocated to future settlement) and a

conservative stand volume of ten cubic

meters per hectare, forest stock in active

settlement areas is estimated to be 25.8

million cubic meters.

23

Using a harvest

cycle of 30 years, this would give a sus-

tained harvest volume of approximately

860,000 cubic meters, which matches cur-

rent demand. At an estimated stumpage

price of 10 Reais (R$10) per cubic meter

of standing trees (approximately US$3.33

per cubic meter), this volume would gen-

erate R$8.6 million per year.

24

To put this

in perspective, if the smallholder forests

within current settlements were used to

their full potential right now, and the

benefits distributed evenly to every fam-

ily (recall there are an estimated 57,000),

each smallholder household could receive

R$150 per year—a large sum given the

discussion below.

Assuming that smallholders will even-

tually settle in areas set aside by INCRA,

there will be an estimated forest stock of

52.6 million cubic meters, which could

render a sustainable harvest of approxi-

mately 1.7 million cubic meters per year,

more than double the current regional

demand. Thus, there appears to be suf-

ficient potential forest stock to meet the

demand, and a tremendous opportunity

for a redistribution of wealth to the poor,

should smallholders have an unham-

pered market to sell wood

(see Table 1 on

page 34).

25

However, one needs to ask if these

estimates based upon government census

data are consistent with data on the

ground. To answer this question we make

use of data generated from a recent com-

prehensive socioeconomic survey of

smallholders along the Trans-Amazon

Highway. Between June and December

2003, a total of nearly 3,000 families were

Figure 3. Land distribution map

NOTE: The spatial distribution of colonization and other formal settlements

is based on information collected from the Brazilian government and analy-

sis of satellite imagery. The main government land use agencies present in

the region are INCRA

a

(land settlement), IBAMA

b

(environmental control)

and FUNAI

c

(indigenous areas).

a

Brazil’s Instituto Nacional de Colonização e Reforma Agrária manages

colonization and agrarian reform.

b

The Instituto Brasileiro do Meio Ambiente e dos Recursos Naturais

Renováveis focuses on the environment and renewable natural resources.

c

The Fundação Nacional do Indio protects the rights of indigenous

Brazilians.

SOURCE: Woods Hole Research Center and Instituto de Pesquisa

Ambiental da Amazônia, with data from INCRA, IBAMA, and Instituto

Brasiliera de Geografia e Estatistica.

JAN UARY/ FEB RUARY 2006 ENVI RON M ENT 33

interviewed, of which 2,441 lived within

the 100-km zone shown in Figure 1.

26

In the survey, smallholders were asked

about their forest production, and socio-

economic data were collected. The results

add to the discussion above, showing

that 26 percent had sold wood, and those

sales had occurred largely within the last

5 years. There had been only one sale per

lot. Ninety-six percent of the smallholders

sold standing trees, and the average num-

ber of trees sold was 20 per smallholder,

which corresponds to a harvest rate of

approximately 1 tree per 5 hectares and,

assuming an average volume of 5 cubic

meters of log per tree, an average sale

volume of 100 cubic meters. The average

total sale value was R$173, which cor-

responds to R$8.65 per tree or R$1.73 per

cubic meter.

27

Comparing these observations with

the results from the geo-spatial analysis

above, based on timber produced through

legal deforestation and harvest of legal

forest reserves (the area of smallholder

land prohibited from clearing for crops),

smallholders are selling approximately

1 cubic meter per hectare, and only 26

percent of them actually sell wood. At this

harvest volume, it would take the harvest

from 10,000 families per year—about 18

percent of the estimated total smallholder

families—to sustain current demand from

the area industry at current prices. This

amounts to a harvest volume that is only

4 percent of current estimates for Amazon

timber production from other studies. At

a harvest intensity of 10 cubic meters

per hectare, this participation requirement

would be drastically reduced to only 1,000

families per year (which represents 1.8

percent of all families). This level of par-

ticipation could be easily achieved without

undue change in the smallholder system

by subcontracting the timber industry to

do much of the technical work associ-

ated with logging. The production of logs

is dramatically low on smallholder lots

because smallholders have limited knowl-

edge of the forest potential and limited

access to the financial resources required

to manage the forests. This barrier can

be overcome with a partnership between

smallholders and the timber industry. For

the successful implementation of such a

partnership, however, it will be important

for smallholders to understand the logging

process and have adequate access to pro-

duction information so that they can main-

tain a check on their industrial partners.

Holding Back the Tide

of Smallholder Forestry

From the perspective of community

foresters, the current ideal is that individ-

uals within the communities must work

collectively and must control the entire

chain of production through to sales of

the final product. Formal interaction with

the timber industry is anathema. Also,

there is still the idea that forest manage-

ment must happen in large, undisturbed,

contiguous tracts of forests. This closely

held and restrictive view has undermined

the potential of community forestry in the

Amazon. The reality is that there are more

than 500,000 settlement families in the

Brazilian Amazon who work individually

or in community associations and who

specialize (though perhaps not yet effi-

ciently) in the supply of standing timber

by working closely with logging compa-

nies (see Figure 5 on page 35).

However, most of the community-

based forestry operations have two key

Figure 4. Land-use change

NOTE: Land use change within a 100-kilometer buffer of the Trans-Amazon

Highway, showing large areas of available forest. The land cover map was

produced from nine co-registered Landsat TM/ETM+ images (228-63, 227-

63, 224-63, 226-63, 225-63, 225-62, 226-62, 227-62, 224-62). The ima-

ges were classified into water, cloud, cloud/shades, forest and non-forest.

SOURCE: Woods Hole Research Center and Instituto de Pesquisa

Ambiental da Amazônia.

34 ENVI RON M ENT VOLU ME 48 N U M BE R 1

problems. First, when dealing with small-

holders on an individual basis, the log-

gers hold all the cards. They have more

information about the species and value

of timber, and they exploit the immedi-

ate financial needs of cash-poor small-

holders. Second, logging on smallholder

lots is legal only under two premises:

smallholders have deforestation licenses

that allow the clearing of 3 hectares per

year and the sale of 60 cubic meters per

year (up to 20 percent of the land area

owned), or they may have the option to

develop a forest management plan that

must be approved by IBAMA. Of the

sales registered in the surveys, 26 percent

came from deforestation permits, and a

startling 79 percent came from the “legal

reserve” on each plot.

28

Because no for-

mal forest management plans have been

developed for these smallholder systems,

this would imply that nearly 80 percent of

log sales from smallholders are currently

illegal by government rules; in addi-

tion, few smallholders get legal defores-

tation permits. Why are there no formal

plans? A forest management plan requires

that the landowner hold legal title, and

although 95 percent of smallholders sur-

veyed claimed to be the landowner, we

found only 26 percent held formal title;

a statistic supported by previous research

in the region.

29

This lack of coordination

between agencies and resource users is a

major barrier to overcoming illegal log-

ging within smallholder systems and to

the integration of smallholders into the

formal timber market.

Small-Farm Family Forestry

in the Amazon

Coordination between ministries is not

an impossible task, however. For exam-

ple, IBAMA, INCRA, and the Ministry

of Public Works of the town of Santarém

(in Pará) operating with limited resourc-

es but in partnership with loggers and

smallholders, found a creative solution

to this problem in the form of an equi-

table partnership between industry and

smallholders. In this case, the community

associations subcontract the loggers to

plan and implement harvesting, while the

government ministries have the responsi-

bility of expediting title and management

approval. The land is owned individually,

and management plans are done for each

private 100-hectare lot, but the nego-

tiations are between the logger and the

community association. The community

can demand higher prices by selling as a

group, and the logger is assured of a long-

term supply of timber. As a result, legal

forest operations are taking place and

smallholders are capturing a fair share of

the benefits from the timber harvest on

their land (see the box on page 37).

30

However, changes in government per-

sonnel and extreme inefficiency (the proj-

ect industry coordinator has had man-

agement plans under review at IBAMA

for more than a year) has made even

this promising partnership tenuous. These

types of projects are in danger of failing

because government oversight is ineffi-

cient, inadequate, corrupt, and contradic-

Table 1. Timber potential from smallholder lots on the Trans-Amazon Highway

Smallholders

Total area

(hectares (ha))

Percent

land

area

Forest

cover

(percent)

Total forest

area (ha)

Timber stock

(m

3

)

Potential

timber flow

(m

3

/year)

Future settlement

projects

3,055,000 19.5 85 2,596,000 25,965,000 865,000

Colonization projects 2,063,000 13.2 40 825,000 8,252,000 275,000

Informal settlement 1,792,000 11.4 60 1,075,000 10,750,000 358,000

INCRA settlements 852,000 5.4 80 682,000 6,815,000 227,000

Demarcated settlements 169,000 1.1 50 85,000 847,000 28,000

Total smallholders

7,931,000 50.6 — 5,263,000 52,629,000 1,753,000

NOTE: INCRA is Brazil’s National Institute of Colonization and Agrarian Reform. The entire buffer area is 15,643,000 ha.

The area not occupied by smallholders is comprised of unclaimed government land (21.2 percent), indigenous land (15.4

percent), medium and large informal settlement (7.6 percent), and conservation units (4.2 percent).

SOURCE: Instituto de Pesquisa Ambiental da Amazônia (the Amazon Institute of Environmental Research).

JAN UARY/ FEB RUARY 2006 ENVI RON M ENT 35

tory.

31

There may be a partial solution to

be found in timber concessions, but even

with successful concessions, the large-

scale problems of illegal logging will not

disappear. Indeed, the problems of illegal

logging will never be solved if IBAMA

cannot control the industry or support

it effectively, but there is no indication

so far that IBAMA can do it alone. It is

reasonable to assume, however, that the

economic benefits of timber production

on their private landholdings will stimu-

late smallholders to manage their forests

and help control illegal activities.

What Does the Future Hold?

What do the results of the Green High-

ways Project have to say about the issue of

loggers and forest policies? As mentioned

above, the main thrust of the new forest

policy centers around timber concessions

on public lands with some allowances

given to communities. This is an effective

program for a portion of the industry, but

there are two problems with the idea. First,

the evidence presented above indicates

that this approach is inadequate for some

major economic corridors where there are

many smallholders, such as in the case

of the region surrounding the Trans-

Amazon Highway; of the 80 percent of

land available for harvest (for example,

excluding conservation units and indig-

enous areas), the Green Highways Project

shows that 64 percent is under the con-

trol of, or is promised to, smallholders.

Second, it also shows that forestry is

highly underutilized in these smallholder

systems. This and the fact that there are

more than 500,000 families settled in the

Amazon region mean these results imply

a very large economic loss to Brazilian

society from not capturing a potential

timber supply that would almost do away

with the need for timber concessions on

public lands.

Further, by excluding smallholders

from access to the timber industry through

current management plan requirements,

smallholders are denied what could

amount to a substantial and vital source

of economic development. In some settle-

ments, research has shown that the value

of a single harvest can equal more than

15 years of agricultural production.

32

And

finally, even if only some portion of the

demand for logs is met by concessions

harvesting on public government lands,

it may have a negative socioeconomic

impact on the potential for small farm

forestry by depressing overall prices.

To promote sustainable forestry, the

evidence indicates that the government

has to realistically deal with land titling,

facilitate institutional coordination,

and commit to stopping illegal logging

through better enforcement. Invariably,

the causes of policy failure and poor

governance are related to corruption and

political auction of important positions in

government institutions. An intricate net

of political obligation, to the detriment

of technical decisions, is commonplace,

and even those individuals fiercely com-

mitted to their tasks (and there are many)

struggle to make quality strategies a real-

ity. A lack of efficiency in government

agencies, whether through poor coordina-

tion or delays, increases transaction costs

and makes formal forest management dif-

ficult. Also, by neglecting secure property

rights, or making these difficult and costly

to obtain, the government inadvertently

creates incentives for smallholders and

loggers to engage in illegal logging.

Figure 5. Patterns of smallholder settlement

NOTE: This image of the Trans-Amazon highway in western Pará shows the

typical herringbone pattern of smallholder settlement. The highway meets

BR163 (Santarém-Cuiabá highway) on the far left of the image. The feeder

roads are 5 km apart and can stretch more than 50 km into the forest. The

typical smallholder lot is 400 by 2,500 meters, so that two can fit between

the feeder roads.

SOURCE: Woods Hole Research Center.

36 ENVI RON M ENT VOLU ME 48 N U M BE R 1

Forest management projects on small-

holder settlement lots in the Brazilian

Amazon will, if widely adopted, help

move the region toward equitable for-

est-based economic development and a

peaceful resolution to the problems now

facing migrant families. This is not the

only solution for the Amazon, but it

is a step forward and one well within

the reach of the current administration.

Without change, however, we can expect

further illegal degradation of the forest

and a continuing struggle for economic

development and social justice on the

Amazon frontier.

Eirivelthon Lima is an associate researcher at the Insti-

tuto de Pesquisa Ambiental da Amazônia (IPAM, the

Amazon Institute of Environmental Research), head-

quartered in Belém, Pará, Brazil, and doctoral student

in Forest Economics at the Virginia Polytechnic Institute

and State University (Virginia Tech). Frank Merry is an

associate researcher at IPAM, research fellow in envi-

ronmental studies at Dartmouth College, and visiting

assistant scientist at the Woods Hole Research Center

(WHRC). Daniel Nepstad is a senior researcher at IPAM

and senior scientist at WHRC. Gregory Amacher is an

associate professor of forest economics at Virginia Tech

and associate researcher at IPAM. Cláudia Azevedo-

Ramos is a senior reseacher at IPAM. Paul Lefebvre is

a senior research associate at WHRC. Felipe Resque Jr.

is a GIS technician at IPAM. We gratefully acknowl-

edge funding from (in alphabetical order) the European

Union; the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation; the

William and Flora Hewlett Foundation; NASA Large

Scale Biosphere and Atmosphere Project; the National

Science Foundation; and the United States Agency for

International Development–Brazil program.

NOTES

1. This approach has been plied very successfully

by large conservation organizations, in particular Con-

servation International, which solicits funds to buy up

biodiversity “hot-spots.” For an analysis of the effects

of parks and protected areas on fires in the Amazon, see

D. Nepstad et al., “Inhibition of Amazon Deforestation

and Fire by Parks and Indigenous Reserves,” Conserva-

tion Biology, In press, expected publication February

2006.

2. I. Bowles, R. E. Rice, R. A. Mittermeier, and G.

A. B. da Fonseca, “Logging On in the Rain Forests,” Sci-

ence, 4 September 1998, 1453–58; R. Rice, C. Sugal, and

I. Bowles, Sustainable Forest Management: A Review of

the Current Conventional Wisdom. (Washington, DC:

Conservation International, 1998); R. Rice, R. Gullison,

and J. Reid, “Can Sustainable Management Save Tropi-

cal Forests?” Scientific American, April 1997, 34–39.

3. D. Pearce, F. E. Putz, and J. Vanclay, “Sustain-

able Forestry in the Tropics: Panacea or Folly?” Forest

Ecology and Management 172, no. 2 (2003): 229–247;

M. Verissimo, A. Cochrane, and C. Sousa Jr., “National

Forests in the Amazon,” Science, 30 August 2002, 1478;

F. E. Putz, K. H. Redford, J. G. Robinson, R. Fimbel,

and G. Blate, Biodiversity Conservation in the Context

of Tropical Forest Management (Washington, DC: Bio-

diversity Studies, The World Bank, 2000), http://world-

bank.org/biodiversity.

4. G. Asner, et al., “Selective Logging in the Ama-

zon,” Science, 21 October 2005: 480–481. The Asner

study claimed that the selective logging of the Amazon

is far more widespread than previously thought. The

authors suggest that the source of logs in the Amazon is

not slash-and-burn deforestation—those logs are simply

burned—but conventional poor-quality selective logging

and that this is the first step in the economic and ecologi-

cal degradation of the forest. According to the data, this

Forest management models that can con-

tribute to the social, environmental, and

economic development of smallholders

and traditional populations have been

the subject of many recent initiatives in

the Amazon. The “Forest Families” pro-

gram [in Santarém] works with a spe-

cific relationship that appears to be very

common but little studied: smallholders

and the timber industry. It is interesting

to note some of the fundamental char-

acteristics around which the program

is built: the relationship between the

smallholder and the industry already

exists; its foundation is market-based; its

actors are well-defined; and [it] is based

on uncommonly strong legal and ethical

rigor. The last characteristic alone makes

one pay attention.

One can question whether this is

community forest management or not.

A pertinent doubt, but, in the end, there

exists a forest and its resources and a

people organized, or organizing, in com-

munities. In fact, the smallholders are

not directly managing their forests: they

delegate this activity to a subcontractor

and his team. And when they delegate

they relinquish some personal control of

the forest. However, they exercise their

rights to the forest in a free manner, in

a negotiation process that strengthens

the local organization, generates collec-

tive responsibility, creates a commonly

used infrastructure, provides income

and, most importantly, gives value to

the standing forest. All of which are the

principles that underlie community for-

est management.

It is possible to imagine a scenario

in which they should manage their own

forests in accordance with their capac-

ity, limitation, abilities, and interests.

Perhaps this will happen one day. But

for right now, the reality is different. No

better and no worse, this is just different

than many other community forest man-

agement initiatives where the local resi-

dents play the role of managers. The fact

is that they, the owners, are who should

say whether this is how it should be.

And they seem to be making this [deci-

sion] in an informed way, understand-

ing their limitations, and identifying

opportunities. It is interesting to observe

a community and its people (in this case

Santo Antonio) started barely two years

ago by families of different origin, who

until this point never knew each other,

but who already have solid development

plans and a growing autonomy in the

formulation of local projects, rather than

just hope of better days.

I believe that one of the principal

contributions that this program can lend

to the discussion of local forest manage-

ment is to define criteria and indicators

of a healthy and egalitarian relationship

between smallholders and the timber

industry. To get there, some challenges

that deserve more attention are:

• Improving local knowledge of

good forest management practices.

• Identifying the impact of timber

harvest on the supply of hunting and

non-timber forest products.

• Analyzing the socioeconomic

impact of the timber income on the

smallholder systems.

SOURCE: André da Silva Dias, Executive Man-

ager, Fundação Floresta Tropical, December 2003.

This box was translated from the Portuguese by

Frank Merry and first published in a report by Insti-

tuto de Pesquisa Ambiental da Amazônia (IPAM)

for the International Institute for Environment and

Development (IIED) as part of the IIED Power

Tools Initiative: Sharpening Policy Tools for Mar-

ginalized Managers of Natural Resources. F. Merry,

E. Lima, G. Amacher, O. Almeida, A. Alves, and

M. Guimares, Overcoming Marginalization in the

Brazilian Amazon Through Community Associa-

tion: Case Studies of Forests and Fisheries, (Edin-

burgh, UK, 2004). It is reprinted with permission.

ANDRÉ DA SILVA DIAS REFLECTS ON THE FOREST FAMILIES PROGRAM

JAN UARY/ FEB RUARY 2006 ENVI RON M ENT 37

is more widely practiced and perhaps more damaging

than previously thought.

5. Forest management and reduced impact logging

(FM-RIL) guidelines are available from many sources:

the Suriname Agricultural Training Center (CELOS);

the International Tropical Timber Organization (ITTO);

the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United

Nations (FAO); the Institute of Humans and the Envi-

ronment of the Amazon (IMAZON); and the Fundação

Floresta Tropical (FFT, Tropical Forest Foundation). In

addition, field models in Brazil demonstrate the improve-

ments of FM-RIL practices over conventional selective

logging. See the FFT website at http://www.fft.org.br

and click “Research.” There have been several studies

on the economic benefits of reduced impact logging and

comparisons with “conventional” selective logging. For

a few examples see: S. Armstrong and C. J. Inglis, “RIL

For Real: Introducing Reduced Impact Logging Tech-

niques into a Commercial Forestry Operation in Guy-

ana,” International Forestry Review 2, (2000): 264–72;

F. Boltz, D. R. Carter, T. P. Holmes, and R. Perreira Jr.,

“Financial Returns Under Uncertainty for Conventional

and Reduced-Impact Logging in Permanent Production

Forests of the Brazilian Amazon,” Ecological Economics

39 (2001): 387–98; P. Barreto, P. Amaral, E. Vidal, and

C. Uhl, “Costs and Benefits of Forest Management for

Timber Production in Eastern Amazonia,” Forest Ecol-

ogy and Management 108, no. 1 (1998): 9–26; and T. P.

Holmes et al., Financial Costs and Benefits of Reduced

Impact Logging Relative to Conventional Logging in

the Eastern Amazon (Washington, DC: Tropical Forest

Foundation, 1999).

6. Thanks to Johan Zweede of the Instituto Florestal

Tropical in Belém, Brazil, and Benno Pokorny of the

University of Freiburg, Germany, for valuable comments

on the history and context of the timber industry.

7. For an excellent review, see I. Sholtz, Overexploi-

tation or Sustainable Management: Action Patterns of

the Tropical Timber Industry: The Case of Pará, Brazil,

1960–1997 (London: Frank Cass Publishers, 2001).

8. By definition the term “frontier,” when applied to

forests, implies the point at which new logging occurs.

It is, however, common in the literature of logging in the

Amazon to differentiate frontiers by age. This is done

partially out of custom, but also because logging on all

“frontiers” is relatively new; even old frontiers are less

than 30 years old.

9. The “Legal Amazon” is a geo-political defini-

tion of the Amazon region in Brazil and comprises the

states of Amapá, Amazonas, Acre, Maranhão, Mato

Grosso, Pará, Rondônia, and Tocantins. The volume

of sawnwood destined for export is different across

frontiers. More than 60 percent of logs from new fron-

tiers are destined for the export market, whereas on the

intermediate and old frontiers, that level dips to 50 and

15 percent, respectively, according to F. Merry et al.,

“Industrial Development on Logging Frontiers in the

Brazilian Amazon,” International Journal of Sustain-

able Development, in review. For a recent discussion of

production volumes, see G. Asner et al., note 4 above.

10. The Instituto Brasileiro do Meio Ambiente e

dos Recursos Naturais Renováveis (http://www.ibama

.gov.br) is the Brazilian government’s environmental

agency responsible for the forest sector and all issues

of environmental control in the country. The federal

land-titling agency is the Institute of Colonization and

Agrarian Reform (INCRA). For more information, see

http://www.incra.gov.br. Each state also has a local

agency.

11. The forest management process includes a formal

management plan that essentially states that the company

intends to harvest in a given area (with accompanying

maps and documentation) and subsequently an annual

operating plan that delivers the details of each year’s

harvest operation. The term “forest management plan”

includes both of these components of logging.

12. For more information on forest concessions, see

A. Veríssimo, M. A. Cochrane, and C. Sousa Jr., National

Forests in the Amazon,” Science, 30 August 2002,

1478.

13. The forest concessions issue has long been debat-

ed in the scientific literature. Both sides of the argument

for Brazil can be explored in F. D. Merry et al., “A

Risky Forest Policy in the Amazon?” Science, 21 March

2003, 1843 and in F. D. Merry et al., “Some Doubts

About Concessions in Brazil,” Tropical Forestry Update

13, no. 3 (2003): 7–9 (see http://www.itto.or.jp/live/

contents/download/tfu/TFU.2003.03.English.pdf). See

also F. D. Merry and G. S. Amacher, “Forest Taxes, Tim-

ber Concessions, and Policy Choices in the Amazon,”

Journal of Sustainable Forestry 20, no. 2 (2005): 15–44;

and Veríssimo, Cochrane, and Sousa, note 12 above. For

earlier discussion on concessions see J. A. Gray, Forestry

Revenue Systems in Developing Countries, FAO Forestry

Paper 43 (Rome, 1983); R. Repetto and M. Gillis, eds.,

Public Policies and the Misuse of Forest Resources,

(Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1988); J.

R. Vincent, “The Tropical Timber Trade and Sustainable

Development,” Science, 19 June, 1992, 1651–1655; and

J. A. Gray, “Underpricing and Overexploitation of Tropi-

cal Forests: Forest Pricing in the Management, Conser-

vation and Preservation of Tropical Forests,” Journal

of Sustainable Forestry 4, no. 1/2 (1997): 75–97. The

Ministry of Environment has created a new law on public

forest management (Law 4776/05), which was approved

by Brazil’s Chamber of Representatives in July, is still

awaiting the vote of the Senate. This law would create

the national forest service, the forest development fund,

and would regulate timber harvest on public lands. Three

kinds of harvest are sought for production forests: direct

government management of conservation units (such as

national forests); local community use (such as extrac-

tive reserves); and forest concessions.

14. Dorothy Stang, a 73-year-old nun from Dayton,

Ohio, a practitioner of liberation theology, and an ardent

supporter of local settlers, was assassinated in broad

daylight in February 2005 in a remote farm commu-

nity near her home of 25 years in Anapú on the Trans-

Amazon Highway. Her battle for equal rights for the

poor, including legal land and resource ownership,

brought her in direct conflict with loggers and ranch-

ers. Her death triggered an avalanche of government

response. Two thousand soldiers were sent to the region

to crack down on illegal loggers and land speculators,

and five million hectares of forest (an area the size of

Costa Rica) were designated as parks and reserves in

what may be the world’s single greatest act of tropical

rainforest conservation.

15. The estimate of forest stock for the Amazon is

approximately 60 billion cubic meters. There are varying

estimates of the flow from the forest: The IBGE, which

is the government institute of geography and statistics

(http://ibge.gov.br), estimates log demand in the north of

Brazil to be about 17 million cubic meters; IBAMA, the

environmental regulation agency of Brazil, estimates it

to be around 25 million; and IMAZON, a local nongov-

ernmental research organization, estimates it at about 24

million—down from 28 million in 1999.

16. The entire Trans-Amazon Highway runs approxi-

mately 3,300 kilometers, connecting the state of Tocan-

tins to the state of Acre near the Peruvian border. Con-

tinuing westward from Itaituba to the town of Humaitá

(a stretch which lies to the west of the Tapajós River) is

virtually uninhabited, but may be the future frontier on

which this story is replayed some years hence.

17. For an excellent discussion on property rights,

violence and settlement on the Trans-Amazon Highway

see L. J. Alston, G. D. Libecap, and B. Mueller, Titles,

Conflict, and Land Use: The Development of Prop-

erty Rights and Land Reform on the Brazilian Amazon

Frontier (Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press,

1999); and L. G. Alston, G. D. Libecap, and B. Mueller,

“Land Reform Policies, the Sources of Violent Conflict

in the Brazilian Amazon,” Journal of Environmental

Economics and Management 39, no. 2 (2000): 162–

188.

18. For more discussion of smallholder settlement

in new and old settlements and the roles of community

associations in economic development in migrant settle-

ments see F. Merry and D. J. Macqueen, Collective Mar-

ket Engagement (Edinburgh, International Institute for

Directional felling, as shown here as part of a reduced impact logging program in the

Tapajós National Forest, near Santarém, can reduce damage and help in the search for

sustainability.

© PETER ESSICK/AURORA—GETTY IMAGES

38 ENVI RON M ENT VOLU ME 48 N U M BE R 1

Environment and Development, 2004), http://www.iied

.org/docs/flu/PT7_collective_market_engagement.pdf.

19. Other institutions working on the Trans-Amazon

Highway within the Green Highways Project are the

Fundação Viver, Produzir e Preservar (FVPP) and the

Instituto Floresta Tropical (IFT).

20. The principal source of government statistics

for Brazil is the Brazilian Institute of Geography and

Statistics (Instituto Brasiliero de Geografia e Estatistica,

IBGE). Their website can be accessed at http://www.ibge

.gov.br.

21. A supervised classification is a procedure for

identifying spectrally similar areas on an image by pin-

pointing training sites of known targets and then extrapo-

lating those spectral signatures to other areas of unknown

targets. The signatures are quantitative measures of the

spectral properties at one or several wavelength intervals.

These measures include class maximum, minimum, mean

and covariance matrix values. Training areas, usually

small and discrete compared to the full image, are identi-

fied through visual interpretation and used to “train” the

classification algorithm to recognize land cover classes

based on their spectral signatures, as found in the image.

The training areas for any one land cover class need to

fully represent the variability of that class within the

image.

22. The total area for squatters was 19 percent of the

buffer zone, of which local extension agents estimated

60 percent to be smallholders. The remaining 40 percent

were said to be medium- and large-size holdings.

23. The evidence also indicated that only one percent

of the buffer area is currently deforested, so these esti-

mates could be considered very conservative for defores-

tation.

24. The price of R$10 is based on a conservative

estimate of a formal logging contract between smallhold-

ers and the industry near the town of Santarém and the

example of a forest concession (3-year cutting contract)

in the Tapajós national forest—an ITTO project run by

IBAMA—where the average stumpage fee for three price

categories in 2003 was R$11.73. The exchange rate for the

period of the survey was approximately R$3 per US$1,

but is now at R$2.2 per US$1. For further commentary

on the timber markets of Brazil, see A. Veríssimo and R.

Smeraldi, Acertando O Alvo: Consumo da Madeira no

Mercado Interno Brasileiro a Promocao da Certificacao

Florestal (Finding the Target: Consumption of Wood

in the Brazilian Domestic Market and the Promotion of

Forest Certification) and M. Lentini, A. Verissimo, and L.

Sobral, Fatos Florestais da Amazônia (Forest Facts of the

Amazon) (Belém, Brazil: Imazon, 2003); E. Lima, and F.

Merry, “Views of Brazilian Producers—Increasing and

Sustaining Exports,” in D. Macqueen, ed., Growing Tim-

ber Exports: The Brazilian Tropical Timber Industry and

International Markets (London: IIED, 2003), 82–102.

25. For an economic model of smallholder decision-

making, production, and labor allocation, see F. D. Merry

and G. S. Amacher, “Emerging Smallholder Forest Man-

agement Contracts in the Brazilian Amazon: Labor Sup-

ply and Productivity Effects,” Environment and Develop-

ment Economics. Invited to revise and resubmit, expected

publication 2006.

26. The preliminary results of the survey were pre-

sented in seminars to the smallholders in June 2004. Fur-

ther details of this survey are available from the authors.

27. In comparison, the estimated price for logs at the

mill gate in 2002 on the Trans-Amazon was R$58 per

cubic meter, and an unadjusted five-year average price

for logs from 1998 to 2002 was R$39 per cubic meter,

but this is before accounting for harvest costs—which for

intermediate frontiers such as the Trans-Amazon can run

between 30 and 40 Reais per cubic meter and transporta-

tion costs; transport distances can run as far as 80 or 90

kilometers from log deck to mill.

28. The legal reserve (Reserva Legal) of a smallholder

lot, or for that matter any private land holding in the

Brazilian Amazon, is 80 percent of the total land area.

This “reserve” area can only be used for forestry with

approved forest management plans or the collection of

non-timber forest products.

29. Alston, Libecap, and Mueller, note 17 above. Only

11 percent of land owners hold formal title. In our survey,

individuals were asked whether they held “definitive

title,” not formal records.

30. This example is well documented. See D. Nepstad

et al., “Managing the Amazon Timber Industry,” Conser-

vation Biology 18, no. 2 (2004): 575–577; D. Nepstad

et al., “Governing the Amazon Timber Industry,” in D.

Zarin, J. R. R. Alavalapati, F. E. Putz, and M. Schmink,

eds., Working Forests in the American Tropics: Conser-

vation through Sustainable Management? (New York:

Columbia University Press, 2004), 388–414.

31. Another example is the project Safra Legal (Legal

Harvest) on the Trans-Amazon Highway. The objective

of this project was to make use of the legal deforestation

options available to smallholders. The idea of this project

came from the forest management projects near Santarém

and presented a wonderful alternative to smallholders

who would have simply burned the trees where they

planned to conduct agricultural activities. The project,

however, has recently become embroiled in scandal as a

conduit of illegal logging, see L. Coutinho, “More Petista

Mud in the Ibama,” VEJA, 15 June 2005, 70. The prob-

lems behind the Safra Legal program were also described

in L. Rohter, “Loggers, Scorning the Law, Ravage the

Amazon Jungle,” The New York Times, 16 October 2005.

These articles illustrate the far-reaching negative effects

of corrupt government on the sustainable management of

natural resources.

32. F. Merry et al., “Collective Action Without Collec-

tive Ownership: the Role of Formal Logging Contracts in

Community Associations on the Brazilian Amazon Fron-

tier,” International Forestry Review, in review. Drafts

available from the authors.