Housing Needs

Assessment

and Strategy

Final Report May 16

th

2022

Prepared for the

City of South Portland

Prepared by the team of

Table of Contents

Chapter 1 Current Socio-Economic Landscape of South Portland and Regional Demographic-

Economic Forecast ____________________________________________________________ 5

Introduction ______________________________________________________________________ 5

Socio-Economic Profile of South Portland _______________________________________________ 8

Population Trends – 1990-2020 _______________________________________________________________ 8

Components of Population Change ___________________________________________________________ 10

Households in South Portland _______________________________________________________ 16

Labor Market and Employment Trends in South Portland _________________________________ 19

Labor Force Trends ________________________________________________________________________ 19

Employment Trends _______________________________________________________________________ 19

Regional Employment Structure _____________________________________________________________ 22

Unemployment __________________________________________________________________________ 24

Commuting Patterns ______________________________________________________________________ 24

Trends in Personal and Household Income in South Portland ______________________________ 29

Personal Income __________________________________________________________________________ 29

Median Household Income _________________________________________________________________ 30

Poverty in South Portland __________________________________________________________________ 30

Chapter 2 Housing Supply in South Portland ______________________________________ 32

Chapter 3 Regional Economic and Demographic Forecast ____________________________ 39

Economic and Demographic Forecast for the MSA and the City – 2021-2030 __________________ 39

Overview ________________________________________________________________________________ 39

National and MSA Macroeconomic Forecast ___________________________________________ 44

Historical Economic and Demographic Data and 2021-2030 Forecast ________________________ 49

Chapter 4 Housing Supply and Demand __________________________________________ 53

Introduction _____________________________________________________________________ 53

Housing Unit Supply and Demand Methodology ________________________________________ 53

Housing Unit Baseline Supply _______________________________________________________________ 53

Summary of Additional Unit Adjustments ______________________________________________________ 54

Housing Unit Demand: _____________________________________________________________________ 55

Findings _________________________________________________________________________________ 55

Chapter 5 Analysis of Housing Affordability _______________________________________ 56

Assessment of the Housing Wage for South Portland ____________________________________ 56

Relating Earnings to Housing Affordability:_____________________________________________________ 56

Defining the “Housing Wage” _______________________________________________________________ 56

South Portland Housing Wage Analysis _______________________________________________ 57

South Portland Median Renter Housing Wage __________________________________________________ 57

South Portland Average Owner Housing Wage _______________________________________________ 58

Owner and Renter Affordability Calculation Methods ____________________________________ 60

Overview of Owner Unit Affordability Calculations ______________________________________________ 61

Property Tax Calculations: __________________________________________________________________ 62

Private Mortgage Insurance (PMI) Rate and Down Payment Percentage _____________________________ 63

Owner Utility Expenditures _________________________________________________________________ 63

Mortgage Rate Methodology________________________________________________________________ 64

Mortgage Value Methodology _______________________________________________________________ 64

Median Transactions Price __________________________________________________________________ 65

Overview of Renter Affordability Calculations __________________________________________________ 65

Affordable Unit Gap Analysis ________________________________________________________________ 67

Affordability Forecast 2020-2030 ____________________________________________________ 71

Median Residential Sales Price/Home Value ___________________________________________________ 71

Utilities _________________________________________________________________________________ 71

Property Tax _____________________________________________________________________________ 72

Homeowner Insurance Calculation and Escalation Methodology ___________________________________ 72

Affordability Analysis Forecast for 2025 and 2030 _______________________________________ 73

Housing Unit Gap Analysis __________________________________________________________ 75

Summary of Findings and Conclusions ________________________________________________ 77

The population of the city is aging. ___________________________________________________________ 77

South Portland is a local hub of employment/jobs for the surrounding communities which has historically

driven demand within the city and in surrounding cities and towns. ________________________________ 77

COVID-19 is impacting demand. _____________________________________________________________ 77

Price pressures are expected to persist due to a combination of several factors _______________________ 77

Despite all the efforts that the city had made to build affordable housing, the affordable price gap is getting

worse. __________________________________________________________________________________ 78

Public forum not surprised by the findings. ____________________________________________________ 79

CHAPTER 6 RECOMMENDATIONS

_______________________________________________ 80

INTRODUCTION TO RECOMMENDATIONS ____________________________________________ 80

A NOTE REGARDING SERVING THE “MISSING MIDDLE” HOUSING CATEGORY ______________ 80

A NOTE ON TARGET HOUSING MARKETS _____________________________________________ 81

RECOMMENDATION 1: A REGIONAL SOLUTION ________________________________________ 81

Developing a Regional Allocation Model and Production Targets________________________________ 84

RECOMMENDATION 2: COMPLETE A COMPREHENSIVE REWRITE OF ZONING ORDINANCE ___ 85

RECOMMENDATION 2A: EXPAND ALLOWANCES IN SINGLE FAMILY ZONES _________________ 88

RECOMMENDATION 2B: DENSITY BONUSES __________________________________________ 95

RECOMMENDATION 2C: REMOVE OFF-STREET PARKING REQUIREMENTS _________________ 95

RECOMMENDATION 2D: ALLOW BY-RIGHT ACCESSORY DWELLING UNITS _________________ 97

Encourage ADU construction _______________________________________ Error! Bookmark not defined.

RECOMMENDATION 2F: CREATE COMPACT-NEIGHBORHOODS ___________________________ 98

RECOMMENDATION 2G: ALLOW ALTERNATIVE HOUSING TYPES ________________________ 100

Manufactured Homes ___________________________________________________________________ 100

Over Water Homes ______________________________________________________________________ 101

3-D Printed Housing ____________________________________________________________________ 101

Micro-Units ____________________________________________________________________________ 101

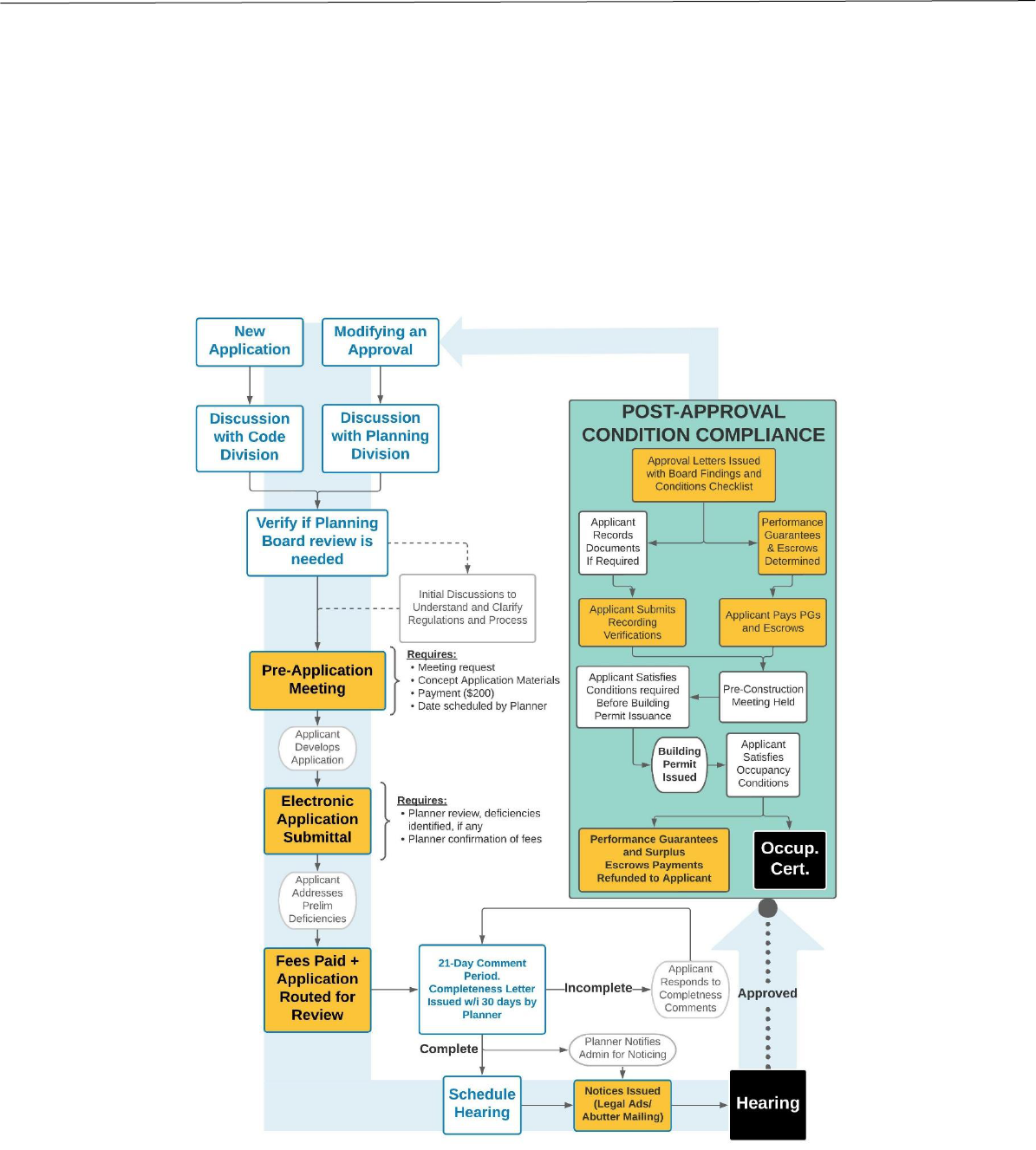

RECOMMENDATION 2H: OVERHAUL THE PERMIT APPROVAL PROCESS ___________________ 102

Create more By-Right Development review processes _________________________________________ 104

RECOMMENDATION 3: CAPITALIZE THE AFFORDABLE HOUSING TRUST FUND _____________ 105

RECOMMENDATION 4: INTERVENTIONS EXCLUSIVE TO RENTER HOUSEHOLDS ___________ 106

RECOMMENDATIONS 4A: STRATEGICALLY EMPLOY TAX INCREMENT FINANCING __________ 106

RECOMMENDATION 4B: HELP IMPROVE CREDIT RATING OF RENTERS ___________________ 107

RECOMMENDATION 4C: ALTERNATIVES TO SECURITY DEPOSIT _________________________ 107

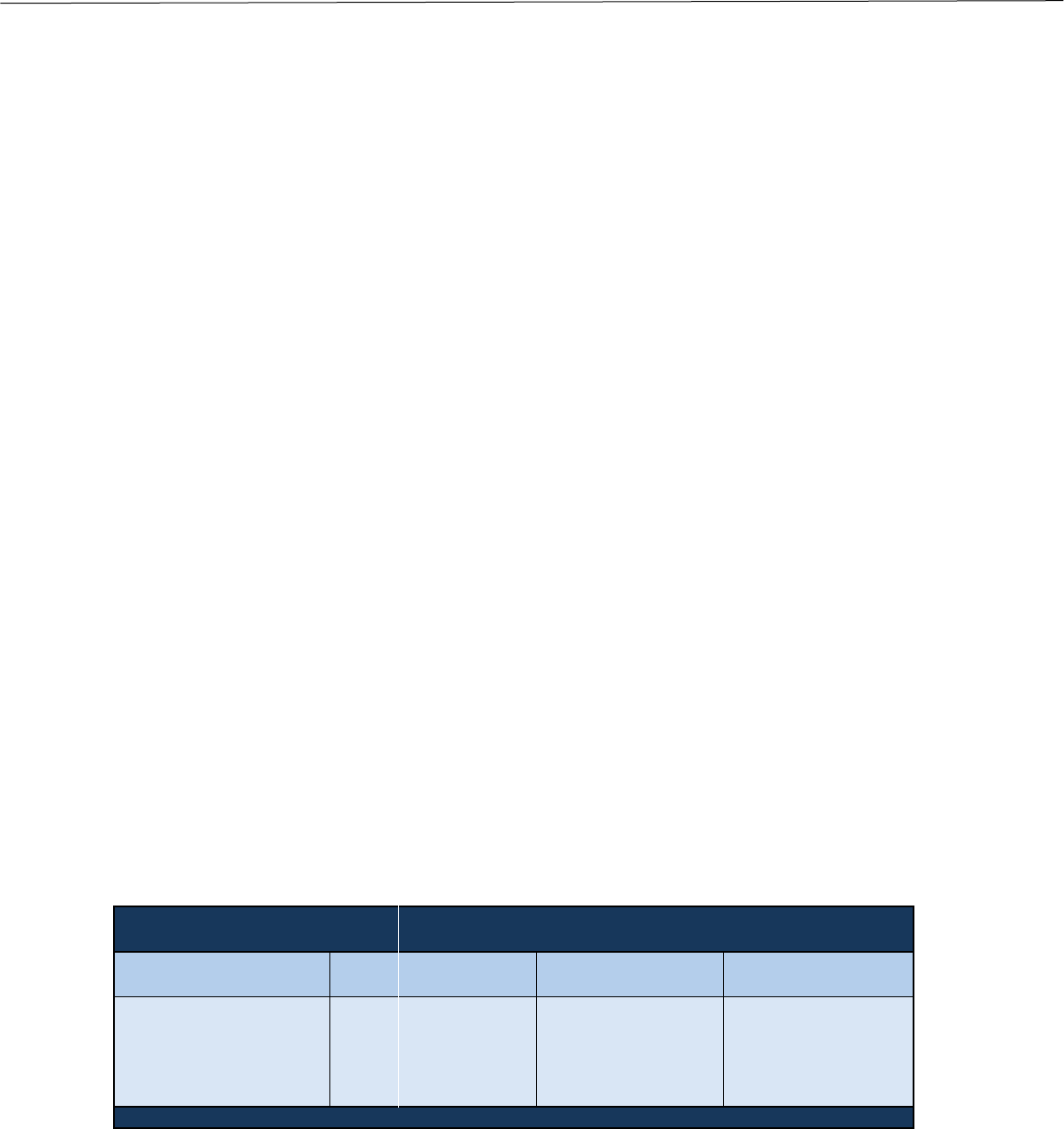

RECOMMENDATIONS MATRIX _____________________________________________________ 108

Housing Needs Assessment and Strategy in South Portland Maine

Page 5 of 108

Chapter 1 CURRENT SOCIO-ECONOMIC LANDSCAPE OF

SOUTH PORTLAND AND REGIONAL DEMOGRAPHIC-

ECONOMIC FORECAST

INTRODUCTION

The City of South Portland is a coastal community in southern Maine of 26,498 people

encompassing an area of 12.07 square miles. The city is often referred to as two cities. The

western half of the city is host to commercial, industrial, and advanced technology developments.

The eastern half of the city includes a community college, a beach area, several parks, one of the

State’s largest marinas, a municipal boat ramp, a maritime museum, and the second busiest oil

depot on the East Coast.

This housing study of both affordable and market rate housing needs is being undertaken at a

very uncertain time for the city, the state, and the nation. This is because it is being undertaken

during a time that includes the first ground war in eastern Europe since World War II, a period

that now includes the highest rates of inflation in four decades, and because it is being undertaken

as the global COVID-19 pandemic has entered its third year. The latter has forced a number of

significant public health measures to be taken which have curtailed economic activity and

distorted the activity of housing markets throughout the country and the northern New England

region. The above developments have combined to produce a number of harshly negative

impacts on the national, state and regional economies. The effects of the pandemic have been

particularly hard on those parts of the economy that rely on person-to-person contact, including

activity in sectors such as: (1) the regional tourism-visitor sector, (2) “bricks-and-mortar” retailing,

eating and drinking places, (3) special events and other gathering venues, (4) certain personal

services providers (e.g. who cannot easily distance themselves from their customers), and (5)

other businesses that rely on the “personal experience” of customers for their revenues and/or

earnings.

The impacts associated with the pandemic, in turn, has resulted in an extraordinary period of

federal fiscal and monetary policy responses, as well as a number of complementary responses

on the state and local government levels, which have helped mitigate the impacts associated with

the pandemic. Those initial economic response policies had unintended economic impacts

(including a rise in inflation) that are now being addressed with additional federal policies designed

to address the rise in inflation and excesses in other over-heated markets—such as housing—in

order to realign demand with supply. The recent strong economic recovery and the large

increases in asset prices were driven at least in part by the extraordinary and coordinated fiscal

and monetary policy response to the pandemic which appears to have overshot the overall decline

in demand and has at least initially resulted in a sharp rise in the economy’s price pressures (at

both the producer level and at the retail level).

Those inflationary pressures and supply-chain disruptions were then made substantially worse

by the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 —which have led to further disruptions in

global supply chains and commodities markets and also led to dramatically increased prices for

key items such as food and energy products.

Housing Needs Assessment and Strategy in South Portland Maine

Page 6 of 108

It is expected that at some point in the future, the effects of this period high uncertainty and

extraordinary policy measures will end and evolve. At that point, the performance of the national

and regional economy and regional housing markets will return to responding to the underlying

economic and financial fundamentals associated with a normally functioning economy and

various commodity markets and the housing market. However, the timing of that future transition

and the exact mechanisms by which that transition will occur are still evolving and some aspects

of the expected transition remain largely unknown. To the extent possible during this unusual

period of “high uncertainty,” this study has strived to differentiate between those factors and

“tastes and preferences” that appear to be more temporary versus permanent in nature.

It is also important to note that the study used a series of long-term forecasts for the national and

regional economy, national financial markets, and for regional demographics and housing

markets in order to guide the study’s estimates of future housing needs. A long-term forecast was

used in this study because it deemphasizes the more transitory, shorter-term and cyclical factors

that can move up and down around the underlying economic and demographic trends. It is those

underlying, longer-term trends that identify and quantify the housing needs of the region and the

city. Those represent the identifiable and quantifiable long-term needs that lend themselves to

actionable policy actions.

The use of long-term forecasts in housing needs assessment studies tend to reduce the impact

shorter-term economic, demographic, and financial developments as well as other forms of

economic and financial “noise” that tend to sling-shot up and down across the longer-term time

horizon. As such, although there may be differences from the longer-term trend line in any given

calendar year due to these shorter- term factors and cyclical events, many times these shorter-

term factors are largely off-set in subsequent years by opposite and substantially equal shorter-

term, cyclical events in the opposite direction over the course of the longer forecast time horizon.

This is especially true for key factors in the housing market pertaining to variables such as

mortgage interest rates, single family house prices, median rents, wage and household income

levels, and costs of building materials for the construction of new housing unit supply,

Periods of more rapid increases in key variables such as interest rates, house prices and rents

can occur in any given year during the longer-term forecast period, typically result in a roughly

equal and opposite period of softness—if not outright declines—in the level of interest rates,

house prices and rents during subsequent years. As such, at the end of the longer-term forecast

period (in this case of this study a 10-year period), the short-term differences from the underlying

trend line largely even out around the long-term trend. The long-term forecast makes allowances

within the longer-term trend for real growth and variations around the trend for such short-term

factors-developments and a certain level of “noise.”

The long-term forecast used in this housing study has been developed using national and regional

economic, financial, demographic, and housing market data and information for the ten-year

forecast period from Moody’s Analytics—a nationally recognized economic forecasting firm, for

the U.S. and the Portland-South Portland ME Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA)

1

—see the map

below. A long-term economic, demographic, financial, and housing market forecast was

developed for the MSA region and city using that national-regional data and information as a

starting point. The forecast period used in this study was long-term in nature (ten years) so that

actionable policies could be developed to focus on the housing needs of the city and region as

1

The Portland-South Portland, ME Metropolitan Statistical Area is composed of Cumberland, Sagadahoc, and York

Counties, with its principal cities of Portland and South Portland, both of which are located within Cumberland

County.

Housing Needs Assessment and Strategy in South Portland Maine

Page 7 of 108

indicated by the assessment of the underlying trends in the economy, demographics, and

financial-housing markets in the city and region.

Figure 1-1 Map of the Region

This report focuses on the identification and quantification of the city’s affordable and market rate

housing needs within the factors and forces that define and affect the South Portland housing

market. This report will present information about and identify gaps in supply and demand for

housing, and propose context-appropriate strategies to address those identified housing gaps.

The report is intended to focus policy and other efforts by the City to those measures that are

most effective in closing housing gaps and addressing housing challenges that the community

faces. The Report and Appendix provide an overview of recent economic and demographic trends

in the city, and present a detailed long-term regional economic and demographic forecast upon

which estimates of the city’s future housing needs are based.

This study also includes recent information on population, households, employment, household

income, commuting patterns, household size, and other important data relative to housing

demand in the city and within the surrounding area. The surrounding area includes: (1)

Cumberland County (“County”), in which the city is located, and (2) the Portland-South Portland

Housing Needs Assessment and Strategy in South Portland Maine

Page 8 of 108

Metropolitan Statistical Area (“MSA”). This long-term forecast builds upon the background of this

regional demographic-economic profile, and the ever-changing and evolving circumstances

regarding the on-going housing market activity in the region and city.

SOCIO-ECONOMIC PROFILE OF SOUTH PORTLAND

Population Trends – 1990-2020

2

Attracting and retaining people to live, work, raise a family, and retire underlies the economic

vitality of any area. Changes in population are almost always associated with changing economic

conditions within the local area. Over the last three decades, the City of South Portland has

experienced moderate population growth. During the 1990s, the City’s population declined by 2.9

percent, in contrast with the rapid growth occurring within the overall MSA at 10.6 percent. From

2000 to 2010, the city resumed growth, with population gains at 6.7 percent versus 5.0 percent

for the MSA. Since 2010, the data indicated that rate of population growth has slowed, punctuated

by an alternating pattern of annual gains and losses, ending in 2020 with 25,950 people. The

recently released 2020 Census data indicates the city had a population of 26,498 as of April 1,

2020, about 2.1 percent higher than the Census Bureau’s mid-year July estimate for 2020.

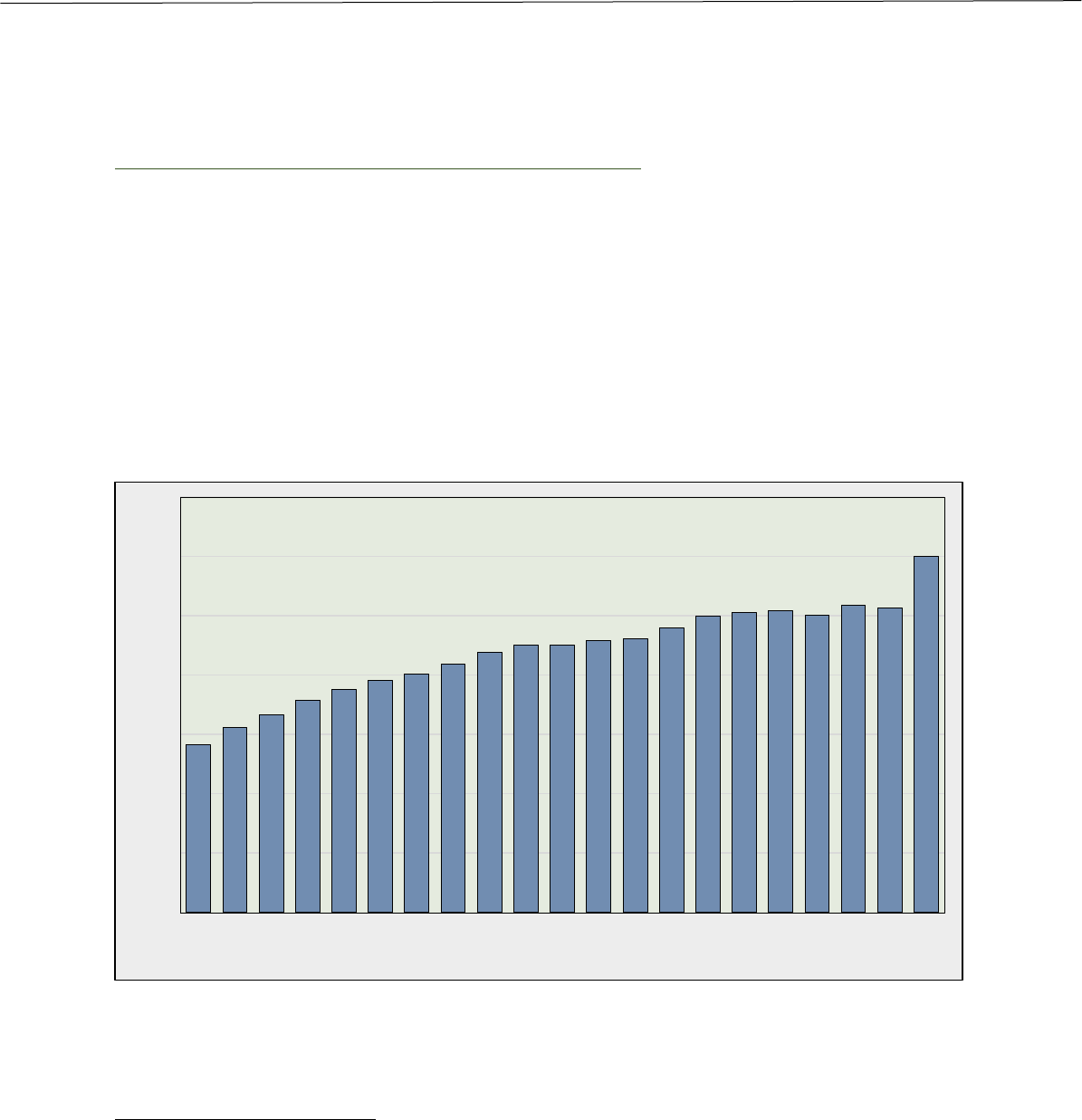

Figure 1-2 Population in the City of South Portland 2000-2020

It is currently unclear whether the results of the 2020 Census are an anomaly caused by the onset

of the COVID pandemic or if there will be upward revisions of the population estimates between

the 2010 and 2020 censuses. In either case, as discussed further in this report, the pace of growth

from 2019 to 2020 is not expected to be maintained over the next 10 years as we move beyond

2

Generally, for most social, demographic, and economic metrics used in this report, 2019 represents the last

historical data release, particularly for the City and its peer communities. Thus, 2020 is the initial year of the forecast

period (2020-2030). There are of course some 2020 exceptions—and are presented (as in population counts) as the

last historical year.

23,324

23,618

23,830

24,073

24,263

24,406

24,508

24,682

24,875

25,012

25,002

25,075

25,108

25,289

25,498

25,558

25,587

25,507

25,677

25,632

26,498

20,500

21,500

22,500

23,500

24,500

25,500

26,500

27,500

Census

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

Census

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

Census

2020

Source: U.S. Census Bureau

Housing Needs Assessment and Strategy in South Portland Maine

Page 9 of 108

the heightened health concerns surrounding the pandemic, the housing market continues to

tighten, and interest rates rise.

From the 2010 to 2020 Census, many of the fastest growing communities within Cumberland

County ringed Portland and South Portland; particularly Scarborough (+17 percent), Gorham

(+11.9 percent), Westbrook City (+16.6 percent), Falmouth (+11.3 percent), Cumberland (+17.5

percent), and North Yarmouth (+14.2 percent). Only two Cumberland County communities lost

population between the 2010 and 2020 Census, Casco (-2.6 percent) and Harrison (-10.4

percent).

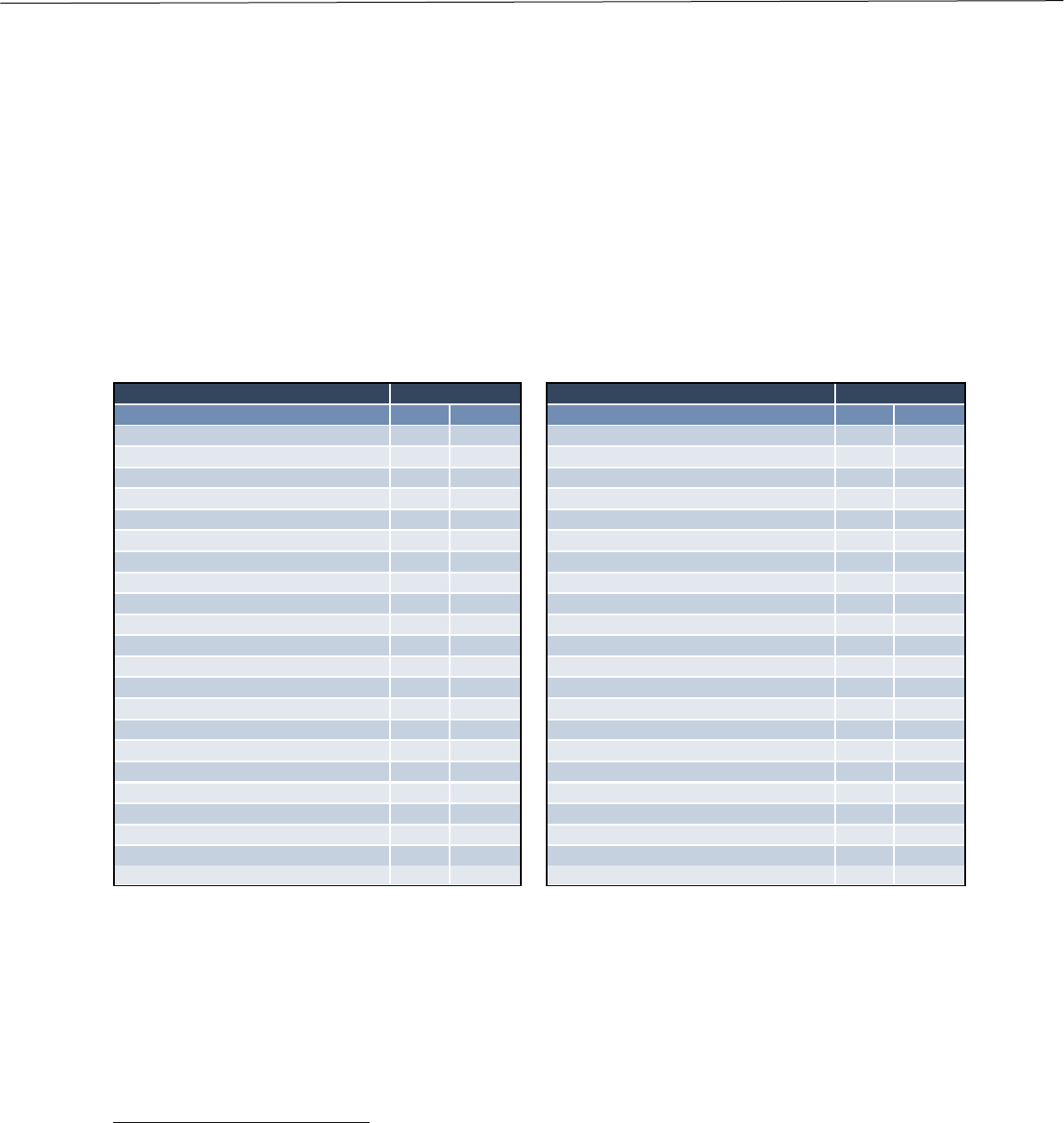

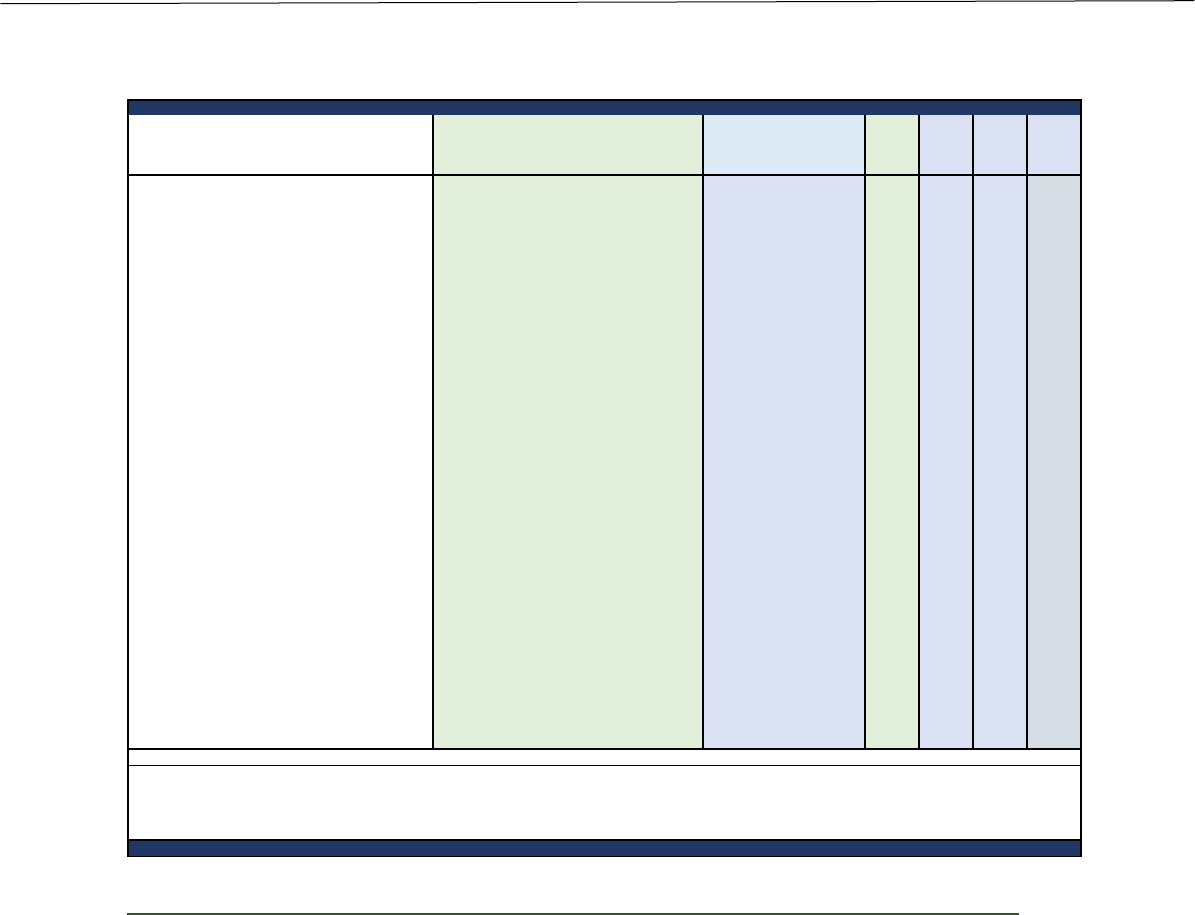

Table 1:1 Population in the City of South Portland 1990 – 2020

Year

South Portland

Portland City

Cumberland County

Portland-So. Portland MSA

1990 Census

24,070

63,125

243,135

441,257

1991

23,923

63,414

244,084

443,863

1992

23,767

62,572

243,852

444,096

1993

23,674

62,274

244,620

445,567

1994

23,807

62,257

246,705

448,325

1995

23,766

62,005

247,792

450,840

1996

23,815

62,067

249,745

455,850

1997

23,843

61,938

251,740

460,748

1998

23,875

61,918

254,041

464,621

1999

23,903

61,967

256,098

469,696

2000 Census

23,324

64,249

265,612

487,568

2001

23,618

64,710

268,391

495,164

2002

23,830

65,033

270,533

500,412

2003

24,073

65,444

273,041

505,379

2004

24,263

65,702

274,920

508,446

2005

24,406

65,834

276,275

510,275

2006

24,508

65,818

277,084

510,656

2007

24,682

66,030

278,781

512,237

2008

24,875

66,289

280,681

514,405

2009

25,012

66,402

281,969

514,878

2010 Census

25,002

66,194

281,674

514,098

2011

25,075

66,193

282,753

516,159

2012

25,108

66,239

283,742

517,816

2013

25,289

66,425

285,681

520,251

2014

25,498

66,876

288,274

524,338

2015

25,558

66,873

289,704

526,248

2016

25,587

66,992

291,522

529,477

2017

25,507

66,739

292,549

532,557

2018

25,677

66,567

294,363

536,225

2019

25,632

66,455

296,052

540,087

2020 Census

26,498

68,408

303,069

551,740

1990-2000 Change

-746

1,124

22,477

46,311

2000-2010 Change

1,678

1,945

16,062

26,530

2010-2020 Change

1,496

2,214

21,395

37,642

1990-2020 Change

2,428

5,283

59,934

110,483

1990-2000 % Change

-3.1%

1.8%

9.2%

10.5%

2000-2010 % Change

7.2%

3.0%

6.0%

5.4%

2010-2020 % Change

6.0%

3.3%

7.6%

7.3%

1990-2020 % Change

10.1%

8.4%

24.7%

25.0%

Source: U.S. Census Bureau

Prepared by Economic & Policy Resources

South Portland’s racial demographics are similar to the County and the MSA, though somewhat

more diverse. South Portland’s population is mostly White-alone (82.9 percent) with the next

Housing Needs Assessment and Strategy in South Portland Maine

Page 10 of 108

largest group being Black or African American (5.8 percent). The city has a greater proportion of

Black or African America, Asian, and Hispanic or Latino than the County and MSA. However, the

City and MSA differ significantly from the national averages. While the U.S. population is majority

White-alone, the South Portland and MSA populations are made up of 20 to 30 percentage points

more White-alone residents than the U.S. as a whole. Every other racial group is a significantly

larger proportion of the population in the U.S. than in the City or MSA.

Table 1:2 Population by Race

South

Portland

Portland

Cumberland

County

Portland-So.

Portland MSA

United States

Population of one race:

92.9%

92.1%

93.4%

93.9%

77.2%

White alone

82.9%

78.0%

86.5%

89.0%

57.8%

Black or African American alone

5.8%

10.1%

3.9%

2.5%

12.1%

American Indian and Alaska Native alone

0.2%

0.2%

0.2%

0.3%

0.7%

Asian alone

3.4%

3.2%

2.4%

1.8%

5.9%

Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander alone

0.1%

0.0%

0.0%

0.0%

0.2%

Some other race alone

0.5%

0.5%

0.4%

0.4%

0.5%

Two or more races:

3.7%

4.1%

3.9%

3.9%

4.1%

Hispanic or Latino

3.4%

3.9%

2.6%

2.3%

18.7%

Total:

100.0%

100.0%

100.0%

100.0%

100.0%

Source: 2020 Census Redistricting Data

Prepared by Economic & Policy Resources

Components of Population Change

An area's population can change in two ways. There is net natural change—the balance of births

minus deaths—and net migration, the balance of persons moving into and out of an area. During

the 1990s, Cumberland County

3

saw a larger share of its population growth from net natural

change but that trend began to shift in the 2000s. Since 2010, 93% of the region’s population

growth was from net in-migration with net natural change turning negative (i.e., more deaths than

births) in 2019 and 2020 (See Figure 1-3).

The recent declining trend in natural population change is largely attributable to the age profile of

the county, affecting both birth and death rates. As an area’s population grows older, most of its

population ages out of childbearing years and eventually into higher mortality age groups. Thus,

without new household formation and replacement population via net migration, the number of

deaths will eventually outnumber new births in the region. The birth rate (i.e., number of births per

1,000 residents) in the Portland-South Portland MSA peaked back in 1990 at 15.04. Since then,

the birth rate has steadily declined to its current low of 8.84.

3

The U.S. Census Bureau reports annual net migration population for counties as part of their annual population

release.

Housing Needs Assessment and Strategy in South Portland Maine

Page 11 of 108

Figure 1-3 Components of Population Change, Cumberland County

South Portland’s median age (41.9 years) is very similar to Cumberland County which represents

one of the youngest counties in the state (42.2 years), with the City of Portland being notably

younger (36.8 years). In the Portland-South Portland MSA, York (45.2 years) and Sagadahoc

(46.9 years) Counties are the oldest compared to the State median of 44.6 years. Maine is the

oldest state in the nation (See Figure 1-4).

The aging population in the region is a result of age cohorts shifting between 2000 and 2019.

These broad age cohorts are:

0-19 years: Infants to prospective new workforce entrants and college-age populations.

20-44 years: New household formers, new entrants to the workforce, and workers in their

prime employment years;

45-64 years: Maturing persons, workers with accumulated skills and experience; and

65 years and older: Principally retirees.

In 2000, over a quarter of the City’s population was in the youngest age cohort of 0-19 years.

Since the early 2000s, this cohort has declined in both relative and absolute numbers. Similarly,

school enrollments (Kindergarten through Grade 12) have declined throughout the region. Since

2012 public school enrollment in South Portland has declined by 6.4 percent (198 students), a

slightly greater decline than the MSA at -5.5 percent (3,977 students) and greater than

Cumberland County at -2.4 percent (943 students).

7,756

6,231

1,213

5,789

7,503

15,596

13,545

13,734

16,809

-

2,000

4,000

6,000

8,000

10,000

12,000

14,000

16,000

18,000

1990-2000 2000-2010 2010-2020

Natural Change Net Migration Net Population Change

Source: U.S. Census Bureau

Housing Needs Assessment and Strategy in South Portland Maine

Page 12 of 108

Figure 1-4 Median Age 2019

The population share of the 20-44 years cohort has also declined since the 1990s and appears

to have aged into the 45-64 age group. Most households form and most entrants into the

workforce are from this age cohort. Since 2000, the share to people ages 45-64 has shown the

largest growth, increasing from 23.1 percent of the population to 29.5 percent.

The aging population of the region can readily be seen in the broad age cohorts of 45-64 years

and 65 years and older, which combined currently make up just under 50% of the region’s total

population (up from 37% in 2000). Each city and town has its own unique population age structure

with each of the four major age cohorts growing or shrinking at different rates.

4

Portland and

South Portland, in particular, have an age structure that resembles an expanding older population,

with low birth rates, a growing elderly class, and younger age cohorts shrinking. The MSA is

experiencing similar trends to the Portland/South Portland experience.

There is a smaller share of those aged 65+ (16.7 %) in South Portland, compared to 18.9% within

the MSA. Many within the 65+ age cohort are “retirees;” this group has grown in both absolute

and relative terms between 2000 and 2019. As the general population continues to age, the

elderly will constitute an increasing share of the region’s population base, making the "graying” of

the MSA (as well as the City of South Portland) a significant socio-economic development

phenomenon (Table 1:4).

4

Age structures are typically called population pyramids. Through a simple graph, this population pyramid conveys

a complex social narrative of population through its shape. While each place has its own unique age structures, there

are three prototypical shapes: expansive (generally, young and growing, characterized by a typical “pyramid” shape

of a broader base with younger age cohorts and a narrow top of elder age cohorts); constrictive (generally, elderly

and shrinking, with an inverted shape tapering at the bottom); and stationary (generally, little or no population

growth, with a rectangular shape).

41.9

36.8

42.2

45.2

46.9

43.7

44.6

38.1

0

10

20

30

40

50

South Portland Portland Cumberland

County

York County Sagadahoc

County

Portland-So.

Portland MSA

Maine United States

Source: American Community Survey

Housing Needs Assessment and Strategy in South Portland Maine

Page 13 of 108

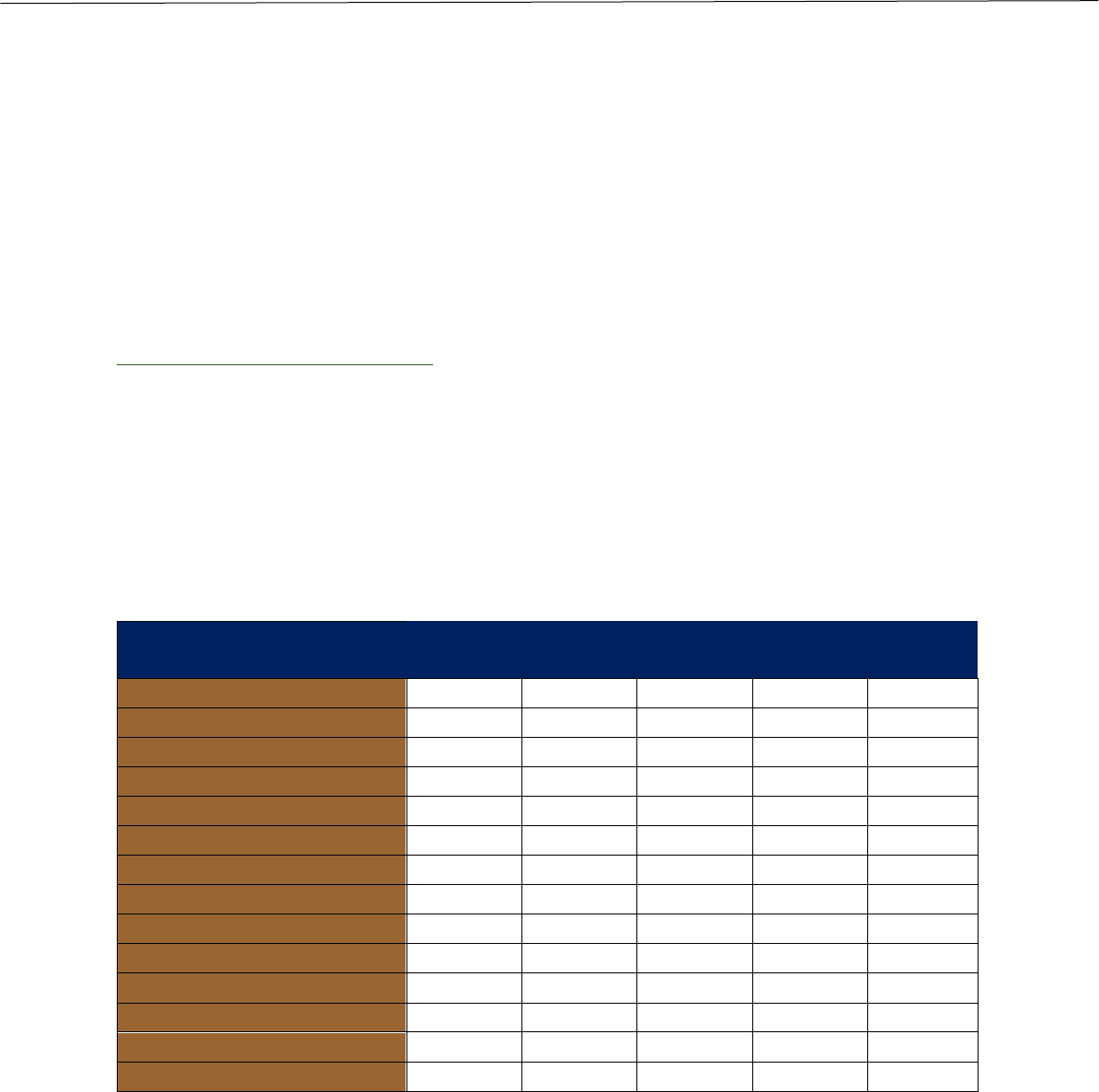

Table 1:3 School Enrollments

Table 1:4 Population by Age Cohorts in South Portland, Portland, Cumberland County, and

Portland-South Portland MSA 2000, 2010, 2019

Geography

Age Cohorts

2000

2010

2019

2000 (%)

2010 (%)

2019 (%)

South

Portland

Ages 0-19

5,982

6,190

5,474

25.6%

24.8%

21.4%

Ages 20-44

8,542

8,428

8,279

36.6%

33.7%

32.4%

Ages 45-64

5,399

6,976

7,527

23.1%

27.9%

29.5%

Working-Age (20-64)

13,941

15,404

15,806

59.8%

61.6%

61.9%

Ages 65+

3,401

3,408

4,268

14.6%

13.6%

16.7%

Portland

City

0-19

14,496

13,756

11,588

22.6%

20.8%

17.4%

20-44

27,622

26,999

28,588

43.0%

40.8%

42.9%

45-64

13,222

17,102

16,593

20.6%

25.8%

24.9%

65+

8,909

8,337

9,826

13.9%

12.6%

14.8%

Cumberland

County

0-19

72,406

70,326

62,598

27.3%

25.0%

21.4%

20-44

95,133

87,089

93,254

35.8%

30.9%

31.9%

45-64

62,749

84,102

84,322

23.6%

29.9%

28.8%

65+

35,324

40,157

52,133

13.3%

14.3%

17.8%

Portland-

South

Portland

MSA

0-19

134,596

127,669

113,140

27.6%

24.8%

21.3%

20-44

170,148

152,139

161,258

34.9%

29.6%

30.3%

45-64

117,737

157,992

157,191

24.1%

30.7%

29.5%

65+

65,087

76,298

100,486

13.3%

14.8%

18.9%

Source: U.S. Census Bureau

Prepared by Economic & Policy Resources

School Year

South

Portland

Cumberland

County

Sagadahoc

County

York

County

Portland- So.

Portland MSA

2012

3,110

39,306

5,249

27,937

72,492

2013

3,122

39,231

5,204

27,641

72,076

2014

3,101

39,249

5,099

27,380

71,728

2015

3,095

39,435

5,010

26,947

71,392

2016

3,088

39,312

4,897

26,817

71,026

2017

3,035

39,180

4,887

26,566

70,633

2018

2,980

39,232

4,796

26,618

70,646

2019

2,979

39,318

4,831

26,517

70,666

2020

2,963

39,534

4,790

26,545

70,869

2021

2,912

38,363

4,648

25,504

68,515

2012-2021 Change

-198

-943

-601

-2,433

-3,977

2012-2021 % Change

-6.4%

-2.4%

-11.4%

-8.7%

-5.5%

Source: Maine Department of Education

Prepared by Economic & Policy Resources

Housing Needs Assessment and Strategy in South Portland Maine

Page 14 of 108

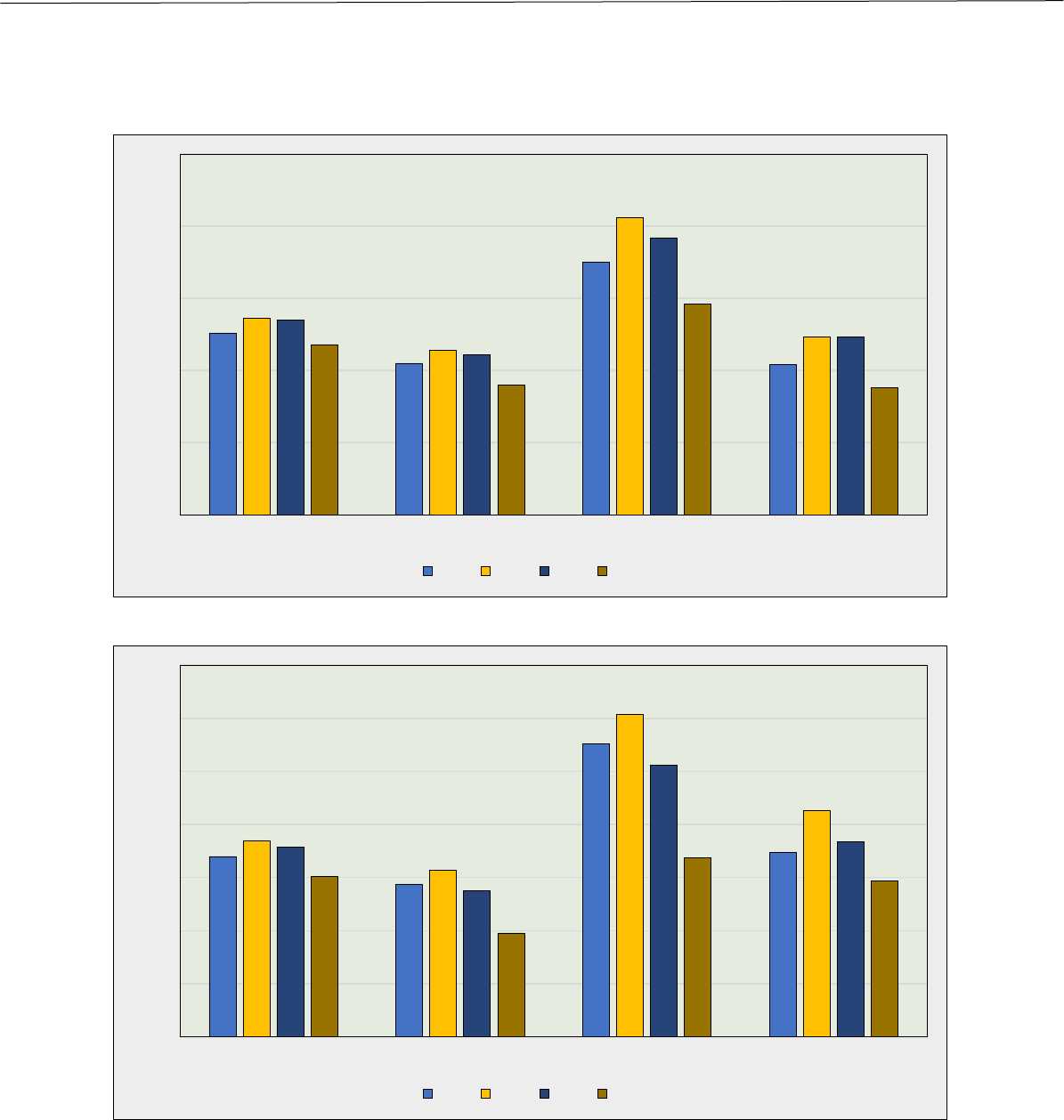

Figure 1-5 Population Share by Age Cohort, City of South Portland 2000-2019

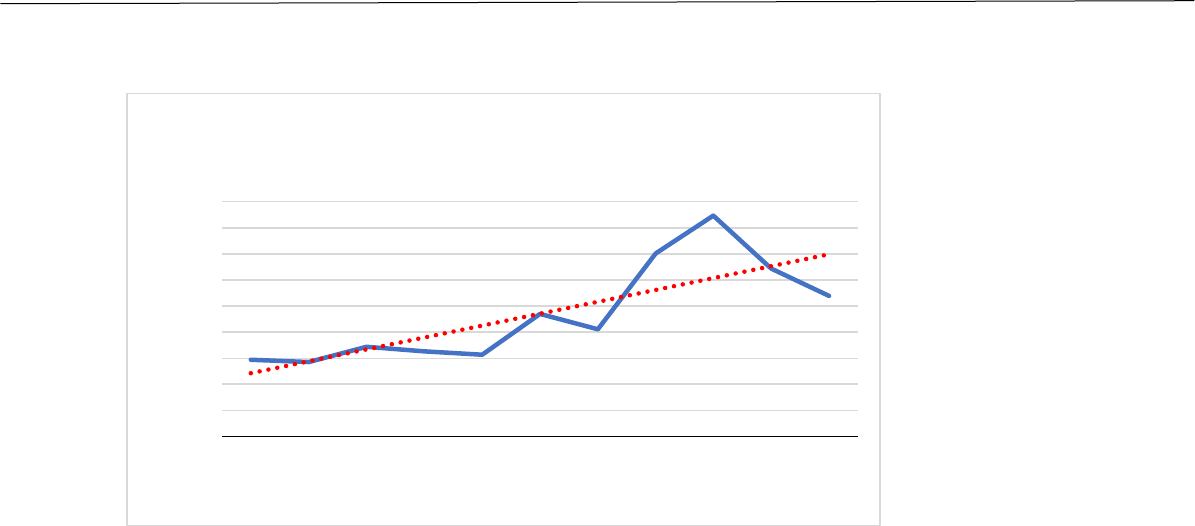

As noted earlier, a region’s or city’s population can change due to net natural change (births minus

deaths); and net migration (persons moving in versus out). For South Portland, natural increase

played an important role in population change in earlier decades. Net in-migration has become a

greater influence since the early 2000s.

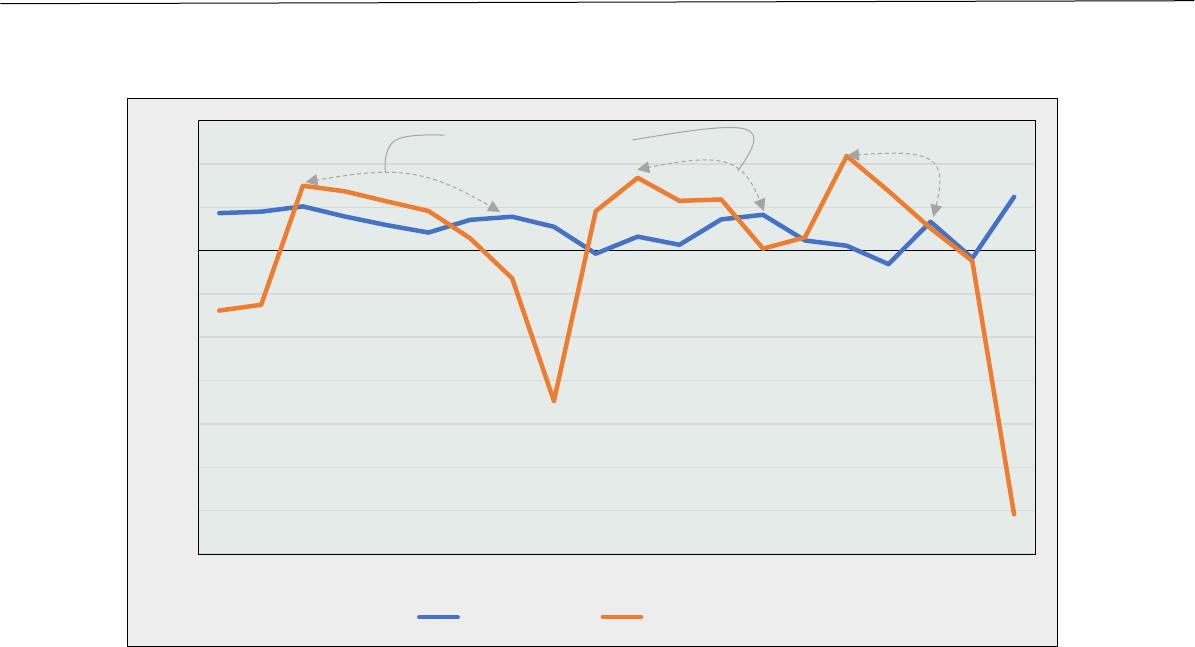

Net in-migration is generally related to local economic performance. Though the phenomenon is

somewhat muted compared to past regional economic cycles, people continue to follow jobs. In

general, as job prospects increase within an area, people will migrate to that area from elsewhere,

attracted by the likelihood of employment. Such migrants, however, tend to arrive well after

economic expansion is under way; thus, a region’s population growth will tend to lag behind its

employment growth (Figure 1-6).

14.6%

13.6%

16.7%

23.1%

27.9%

29.5%

36.6%

33.7%

32.4%

25.6%

24.8%

21.4%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

2000 (%) 2010 (%) 2019 (%)

Ages 65+ Ages 45-64 Ages 20-44 Ages 0-19

Housing Needs Assessment and Strategy in South Portland Maine

Page 15 of 108

Figure 1-6 Annual Percent Change in Population and Employment in South Portland, 2000-

2020

-7.0%

-6.0%

-5.0%

-4.0%

-3.0%

-2.0%

-1.0%

0.0%

1.0%

2.0%

3.0%

2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020

Net Population Net Employment

Source: U.S. Census Bureau and

Bureau of Labor Statistics

Examples of employment

growth leading ahead of future

population increases

Housing Needs Assessment and Strategy in South Portland Maine

Page 16 of 108

HOUSEHOLDS IN SOUTH PORTLAND

Significant demographic determinants in housing demand are new formations of households and

household size. Looking back at the past two decades, household changes have mainly reflected

the maturing of the “baby boom” population. Baby boomers are generally defined as those

persons who were born between 1946 and 1964–a period of time when the nation experienced

strong population growth rates following the end of World War II. The oldest “baby boomers” are

today in their late-sixties to mid-seventies, and the youngest nearing their mid-fifties. Therefore,

the majority of this population group has already formed independent households—a factor that

is very important to housing markets.

Table 1:5 Households in South Portland, 2000-2020 (Census Years)

Municipality / Region

2000

Census

2010

Census

2020

Census

2000-2010 Change

2010-2020 Change

(#)

(%)

(#)

(%)

South Portland

10,047

10,877

11,793

830

8.3%

916

8.4%

Cumberland County

107,989

117,339

128,100

9,350

8.7%

10,761

9.2%

Sagadahoc County

14,117

15,088

16,136

971

6.9%

1,048

6.9%

York County

74,563

81,009

88,924

6,446

8.6%

7,915

9.8%

Portland-So. Portland MSA

196,669

213,436

233,160

16,767

8.5%

19,724

9.2%

Source: U.S. Census Bureau

Prepared by Economic & Policy Resources

The post-“baby boom” population–which is smaller than the baby boom population–is now in the

prime age categories for forming new households. An overall slowdown in the rate of new

household formations because of the aging of the “baby boomer” segment of the population is a

demographic trend that is expected to continue to dominate in the entire United States over the

next decade. This well-known demographic dynamic will therefore affect the level and nature of

housing demand in South Portland over the next decade as well.

Figure 1-7 Owner/Renter Occupied Units by Age of Householder in South Portland, 2019

14%

42%

61%

65%

68%

70%

82%

73%

51%

86%

58%

39%

35%

32%

30%

18%

27%

49%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

Householder

15 to 24 years

Householder

25 to 34 years

Householder

35 to 44 years

Householder

45 to 54 years

Householder

55 to 59 years

Householder

60 to 64 years

Householder

65 to 74 years

Householder

75 to 84 years

Householder

85 years and

over

Owner-Occupied Renter-Occupied

Housing Needs Assessment and Strategy in South Portland Maine

Page 17 of 108

Off-setting the decline in housing demand caused by the aging “baby boom” population is the

trend towards decreasing household size. There are fewer persons per household today than in

the past in owner occupied units. Renter occupied units are countering this trend by increasing in

average household size by about 22% over the last decade. This shift could be explained by an

increasing share of renters aged 35-64 years, the prime age for raising children. Similarly, there

is a growing share of homeowners aged 65 to 84 years which typically have fewer people per

household. However, since there are more owner-occupied units than rental unit in the city, the

net effect is a decrease in average household size in the city. The most obvious implication for

housing demand from this net effect over time is that more housing units will be required to house

each increment of both the existing population and any population growth in the city over the next

decade versus what was the case over the last twenty to thirty years.

Figure 1-8 Owner and Renter Households Size, 2000, 2010 and 2019

Over the past two decades, the number of owner-occupied units has slowly increased within the

city from 6,467 units in 2000 to 6,885 units in 2019. Renter occupied units have fluctuated from

3,580 units in 2000, increasing to 4,245 units in 2010 and then declining slightly to 3,971 renter-

occupied units in 2019. Some of this fluctuation, particularly around the 2010 Census, may be

explained by the shifting housing needs before, during, and after the Great Recession (2007-

2009) when many owner-occupied houses were foreclosed upon increasing the number of rental

units, as well as the increasing number of vacant units

5

within the City, increasing from 302 units

2000 to 850 units in 2019.

5

A housing unit is vacant if no one is living in it at the time the survey is taken. Vacant units can include

seasonal/second homes, new owner/rental units that are not yet occupied, or units being held off the market for

repairs, settlement of an estate, and/or for other personal reasons.

2.43

1.98

2.37

2.03

2.35

2.20

0.00

0.50

1.00

1.50

2.00

2.50

3.00

Owner HH Size Renter HH Size

2000 2010 2019

Housing Needs Assessment and Strategy in South Portland Maine

Page 18 of 108

Figure 1-9 Owner-Occupied, Renter- Occupied and Vacant Units in South Portland, 2000, 2010,

2019

6,467

6,632

6,885

3,580

4,245

3,971

302

607

850

0

1,000

2,000

3,000

4,000

5,000

6,000

7,000

8,000

2000 2010 2019

Owner-Occupied Renter-Occupied Vacant

Housing Needs Assessment and Strategy in South Portland Maine

Page 19 of 108

LABOR MARKET AND EMPLOYMENT TRENDS IN SOUTH PORTLAND

Labor Force Trends

The City’s labor force

6

has generally tracked closely with the national business cycle expansion

and contraction, though in a more muted fashion. After declining slightly in the early 1990s, the

City’s labor force grew by roughly 12 percent to 13,691 people in 2000. From then on, the City’s

labor force has grown slowly, moved up and down with the business cycles and reached a peak

in 2018 with 14,804 people. After a very slight decline in 2019, the labor force contracted by 2.5%

in 2020 as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic to 14,353 people (versus a contraction of 1.7% for

the nation Figure 1-10).

Figure 1-10 Labor Force in South Portland, 1990-2020

Employment Trends

In the 1990s, total employment

7

in the city has fluctuated significantly but ended the period

stronger than it started. There was relatively little change in employment from 2000 through 2015,

with employment peaking in 2018 with 14,897 workers. Employment in the City—as throughout

the nation due to the COVID-19 pandemic—took a marked hit in 2020 with the number of wage

and salary workers dropping to 13,762 (down 7.6 percent from 2018).

6

The labor force refers to those persons employed or seeking employment (unemployed) within a geographic area.

Employment in this case is not a measure of the number of jobs within the city but a measure of the number of

people within the city who have reported through a survey of households in the city that they hold at least one job.

7

Total employment used in this report is consistent with the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) series of full- and

part-time employment. In addition to wage and salary employment BEA includes employment of proprietors, as well

as farm workers and military.

13,150

12,894

12,243

13,093

13,263

13,691

13,432

13,845

14,159

14,206

14,219

14,495

14,475

14,583

14,804

14,353

-

2,000

4,000

6,000

8,000

10,000

12,000

14,000

16,000

1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 2006 2008 2010 2012 2014 2016 2018 2020

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

Housing Needs Assessment and Strategy in South Portland Maine

Page 20 of 108

Historically, the majority of employment in the city have been salary- and wage-earning rather

than proprietors. Since 1990 the share of proprietors in South Portland has remained relatively

stable at roughly 6 percent, with most of the employment growth from the 1990s through 2000s

generated by wage-earning jobs.

Figure 1-11 Total Employment in South Portland, 1990-2020

This pattern was mirrored within the sectors of the regional economy. Natural resources and

mining, construction, and manufacturing (i.e., goods-producing) sectors all experienced

noticeable contractions between 2010 and 2019 as a percentage of total employment, declining

by 0.3 percentage points, 1.5 percentage points, and 1.3 percentage points, respectively. During

the same period, the leisure and hospitality sector’s share of total employment expanded by 4.8

percentage points, and retail trade expanded by 1.1 percentage points ( Figure 1-11).

12,340

11,804

13,013

13,186

13,163

13,116

12,887

849

812

895

905

911

934

875

0

2,000

4,000

6,000

8,000

10,000

12,000

14,000

1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015 2020

Salary and Wage Workers Proprietors

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, EPR

Housing Needs Assessment and Strategy in South Portland Maine

Page 21 of 108

Figure 1-12 Employment by Sector in South Portland: 2010, 2015, and 2019

2.9%

1.8%

2.2%

3.7%

5.0%

4.6%

7.7%

10.9%

12.4%

29.5%

25.3%

29.7%

11.8%

14.5%

10.2%

9.6%

8.6%

8.7%

2.6%

2.8%

3.3%

4.3%

2.6%

4.5%

11.9%

14.5%

13.0%

3.0%

1.8%

1.3%

7.8%

7.2%

6.5%

4.8%

3.9%

3.3%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

2010 2015 2019

Natural Resources

and Mining

Construction

Manufacturing

Wholesale trade

Retail trade

Transportation and

Utilities

Information

Financial Activities

Professional and

Business Services

Education and Health

Services

Leisure and

Hospitality

Other Services

PublicAdministration

Housing Needs Assessment and Strategy in South Portland Maine

Page 22 of 108

Regional Employment Structure

In economic terms, a region’s employment base is defined as that employment among firms

whose products or services are sold to markets outside of the region, thereby capturing new

income for the area. Those customers may be in other parts of the state, in other states, or in

foreign countries. Regional economic theory holds that selling to a non-local customer brings

income into a region and qualifies that firm as part of the local economic base. Businesses that

sell to local customers, such as other businesses or households, are called non-basic businesses.

Services provided to markets outside the region and services provided to visitors coming in from

outside the region also qualify as basic industries in capturing streams of new revenue.

Basic employment is that share of a regional industry’s employment that corresponds to the

industry’s output sold outside the region. Estimates of basic employment among the regional

industries was based on an indirect measure of specialization called location quotient analysis.

Location quotients are simply measures of economic specialization; here comparing the share of

total employment in a particular industrial grouping in the region with the share it represents in

the nation. The quotient for any industry or sector is determined by dividing its share of the region

employment by its share of national employment. The idea behind this measure is that a region

that is highly specialized in a given sector is exporting a portion of that good or service. In contrast,

a less developed industry sector implies that the region is importing goods and services to meet

local demand in that sector.

A location quotient is computed in the following manner:

LQ

E E

E E

i

ic c

is s

/

/

where:

LQ

i

is the location quotient for sector i;

E E

ic c

/

is the percent of regional employment in sector i; and

E E

is s

/

is the percent of national employment in sector I.

Essentially, location quotients indicate an industry sector’s self-sufficiency and export orientation.

A quotient of 1.0 means that the region has the same proportion of its employment in sector i as

the nation. In other words, the region just meets local consumption requirements through local

production of the specified good or service. If the location quotient is less than 1.0, the region is

not producing enough to meet local needs, meaning that local residents and businesses need to

import some goods or services to meet production or consumption requirements. This analysis

can become a key indicator of sectors to focus on among local economic developers that are

seeking to implement an import substitution strategy for growth. If the location quotient is greater

than 1.0, the area has a larger proportion of its employment in sector i than does the nation, and

is considered “specialized” in that sector. The excess proportion is assumed to be for export

purposes and may represent an economic competitive “edge” for the region.

Housing Needs Assessment and Strategy in South Portland Maine

Page 23 of 108

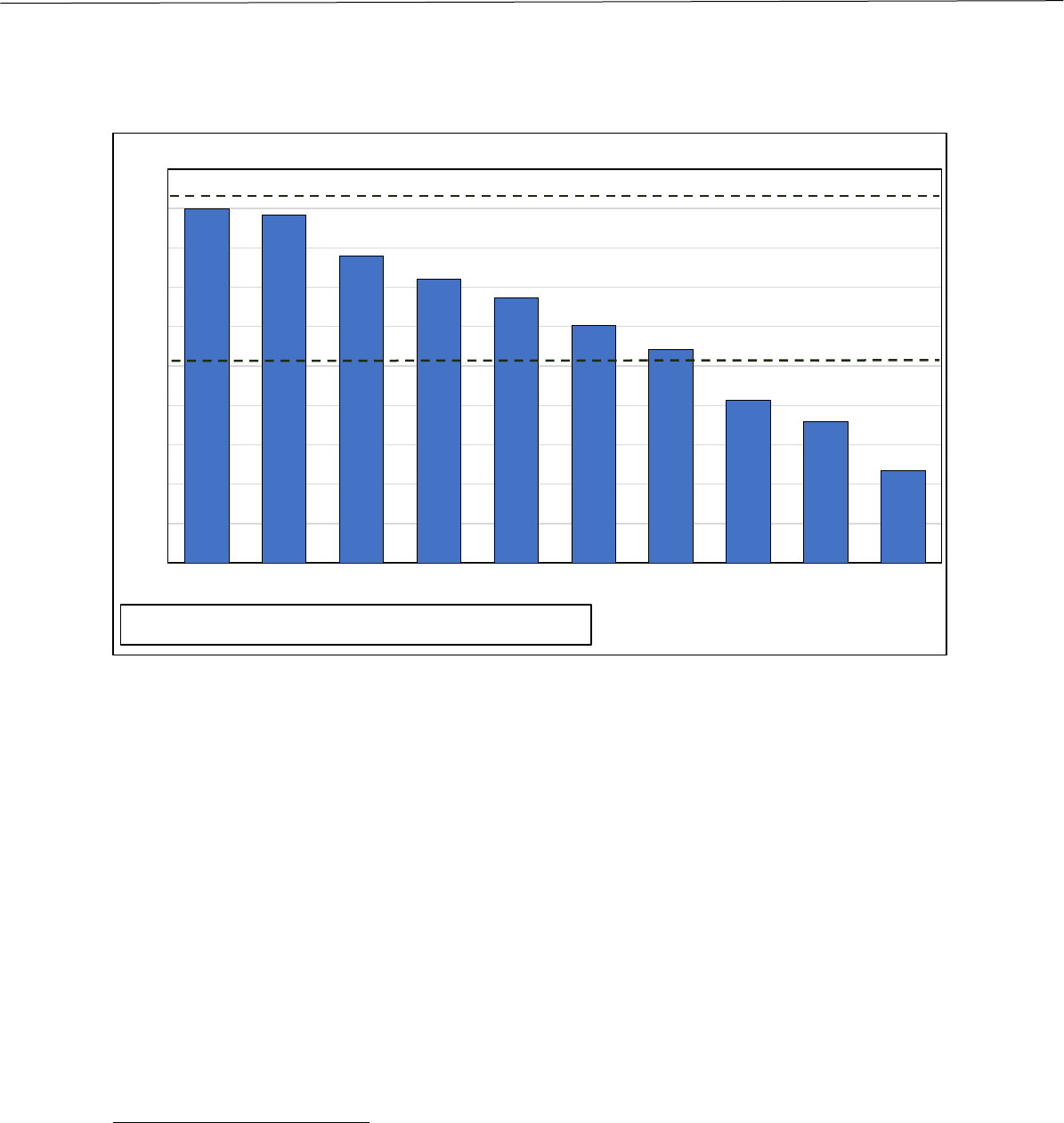

Figure 1-13 Economic Specialization of South Portland, 2010 and 2019

The location quotient helps identify a region's export sectors. Implicitly, this notion contends that

a regional economy depends upon the vigor of its export industries. Other economic sectors in

the region in turn support these export-oriented industries by providing needed supplies and

services. As export industries grow, then linked local sectors will in turn expand.

More recently, this technique has been utilized to help identify local industry clusters (composed

of leading companies and their respective supply chains). Any exporting industry, identified

through location quotient analysis, might be a strong candidate for further development and can

serve as the core of an industry cluster for the region. An industry cluster is a concentration of

related industries and associated institutions with overlapping knowledge, skills, inputs, demand,

and/or other economic linkages. An industry cluster tends to encourage the location of other

supporting businesses, along with the persons-households with complementary skill sets (i.e. to

staff the other companies that may be needed to supply-support the export-based facilities of the

cluster) in order to facilitate the development of a sustainable competitive advantage that

underpins sustainable future job growth for the region’s industry cluster as a whole. This, in turn,

can lead to increased demand for housing within the impacted region related to this growth.

Economic snapshots of South Portland are provided for 2000 and 2019. Currently, the regional

industries of importance include Information, Financial Activity, Education and Health Services,

0.30

0.67

0.71

0.97

1.04

0.85

1.09

1.37

1.13

1.34

0.86

0.75

0.60

0.14

0.50

0.65

0.52

1.16

0.83

1.64

1.32

0.88

1.29

1.29

0.95

0.47

0.00 0.20 0.40 0.60 0.80 1.00 1.20 1.40 1.60 1.80

Natural Resources and Mining

Construction

Manufacturing

Wholesale trade

Retail trade

Transportation and Utilities

Information

Financial Activities

Professional and Business Services

Education and Health Services

Leisure and Hospitality

Other Services

PublicAdministration

2010 2019

Source: American Community Survey

Housing Needs Assessment and Strategy in South Portland Maine

Page 24 of 108

and Leisure and Hospitality. Each of these industries have location quotients exceeding 1.2,

underscoring economic specialization (Figure 1-13).

Unemployment

Unemployment is a significant indicator of the vitality of a region’s economy. As noted earlier, the

labor force consists of two groups: those who are working; and those who are seeking work.

Those who are not working but are actively looking for work constitute the unemployed.

8

Figure 1-14 Annual Unemployment Rate in South Portland and Portland-So Portland MSA, 2000-

2020

The unemployment rate in the Portland-South Portland MSA has been consistently higher—

between 0.1 to 0.8 percentage points—than the city’s unemployment rate over the past 20 years.

By 2019, the city and MSA had largely recovered from the “Great Recession,” with the

unemployment rate reaching new record lows. In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic-induced

recession saw the unemployment rates jump to 5.3% in the MSA and 5.7% in the city, reversing

the long trend of lower unemployment within the city. Preliminary data for the first few months of

2021 indicate that the city is also recovering more quickly than the MSA as a whole (Figure 1-14).

Commuting Patterns

Commuting/worker flows throughout the day include (1) internal movements—city residents

traveling to in-city workplaces; and (2) external movements, composed of either city residents

commuting to workplaces located outside of the city, or nonresidents commuting to workplaces in

the city. The table below, which presents the most recent available commuting behavior data

(2018) of residents and workers in the city, indicates that the city is a net importer of workers. In

8

Discouraged workers, defined as those no longer active in looking for work, are not included in the official labor

force numbers.

2.3%

2.5%

3.0%

3.3%

3.1%

3.5%

3.3%

3.3%

4.0%

6.7%

6.6%

6.0%

5.8%

5.2%

4.5%

3.4%

2.8%

2.6%

2.4%

2.2%

5.7%

2.5%

3.0%

3.7%

4.1%

3.6%

3.9%

3.7%

3.7%

4.4%

7.2%

7.3%

6.6%

6.1%

5.8%

4.7%

3.6%

3.1%

2.8%

2.6%

2.3%

5.3%

0.0%

1.0%

2.0%

3.0%

4.0%

5.0%

6.0%

7.0%

8.0%

2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020

South Portland city, ME Portland-So. Portland MSA

Housing Needs Assessment and Strategy in South Portland Maine

Page 25 of 108

2018,

9

there were about 10,312 city residents holding jobs outside of the city—primarily in

Portland, Scarborough, and Westbrook, while the city’s employers imported 21,314 non-resident

workers from surrounding communities.

The commuter data shows that residents of the city travel a much shorter distance to work, with

76.6 percent travelling less than 10 miles and only 13.7 percent traveling farther than 25 miles. In

contrast, only 46.0 percent of workers in South Portland travel less than 10 miles to get to work

and 27.5 percent traveling farther than 25 miles. Interstate 95 and 295 play a vital role in

connecting residents of other cities and towns with employment opportunities in the city. Interstate

95 runs south-to-north from Portsmouth, NH through Portland and South Portland and on through

Augusta and Bangor before ending at the Houlton-Woodstock border crossing with Canada.

Interstate 295 is an auxiliary interstate highway running from Scarborough along the Maine coast,

bypassing Lewiston and Auburn, and reconnecting with Interstate 95 just south of Augusta.

Table 1:6 Commuting Patterns in South Portland, Primary Jobs

10

2018

Where Workers in South Portland Live

2018

Where Residents of South Portland Work

2018

Municipality

Count

Share

Municipality

Count

Share

Portland city (Cumberland, ME)

3,293

13.54%

Portland city (Cumberland, ME)

4,878

37.25%

South Portland city (Cumberland, ME)

2,782

11.44%

South Portland city (Cumberland, ME)

2,782

21.25%

Scarborough town (Cumberland, ME)

1,269

5.22%

Scarborough town (Cumberland, ME)

951

7.26%

Westbrook city (Cumberland, ME)

1,181

4.86%

Westbrook city (Cumberland, ME)

738

5.64%

Gorham town (Cumberland, ME)

998

4.10%

Falmouth town (Cumberland, ME)

279

2.13%

Saco city (York, ME)

909

3.74%

Biddeford city (York, ME)

268

2.05%

Windham town (Cumberland, ME)

864

3.55%

Gorham town (Cumberland, ME)

189

1.44%

Biddeford city (York, ME)

737

3.03%

Cape Elizabeth town (Cumberland, ME)

172

1.31%

Buxton town (York, ME)

517

2.13%

Saco city (York, ME)

169

1.29%

Cape Elizabeth town (Cumberland, ME)

499

2.05%

Lewiston city (Androscoggin, ME)

161

1.23%

Falmouth town (Cumberland, ME)

481

1.98%

Augusta city (Kennebec, ME)

157

1.20%

Old Orchard Beach town (York, ME)

462

1.90%

Brunswick town (Cumberland, ME)

148

1.13%

Standish town (Cumberland, ME)

443

1.82%

Yarmouth town (Cumberland, ME)

142

1.08%

Gray town (Cumberland, ME)

343

1.41%

Freeport town (Cumberland, ME)

134

1.02%

Lewiston city (Androscoggin, ME)

339

1.39%

Windham town (Cumberland, ME)

124

0.95%

Sanford city (York, ME)

309

1.27%

Auburn city (Androscoggin, ME)

116

0.89%

Cumberland town (Cumberland, ME)

268

1.10%

Bangor city (Penobscot, ME)

110

0.84%

Waterboro town (York, ME)

268

1.10%

Kennebunk town (York, ME)

69

0.53%

Brunswick town (Cumberland, ME)

266

1.09%

Cumberland town (Cumberland, ME)

62

0.47%

Yarmouth town (Cumberland, ME)

257

1.06%

Sanford city (York, ME)

51

0.39%

All Other Cities/Towns

7,829

32.20%

All Other Cities/Towns

1,394

10.65%

Total

24,314

100.00%

Total

13,094

100.00%

9

Most current year of available data.

10

A primary job is the highest paying job for an individual worker for the year. The count of primary jobs is the same

as the count of workers.

Housing Needs Assessment and Strategy in South Portland Maine

Page 26 of 108

Figure 1-15 Distance and Direction of Workers in South Portland to their home (left) and of

Residents in South Portland to their work

Housing Needs Assessment and Strategy in South Portland Maine

Page 27 of 108

Figure 1-16 Where Residents of South Portland Work, 2018

Housing Needs Assessment and Strategy in South Portland Maine

Page 28 of 108

Figure 1-17 Where Workers in South Portland Live, 2018

This data shows that the city is a regional hub of employment, drawing many residents from the

surrounding towns to the city for work. These commuters may seek to shorten their commuting

time and expenses by living closer to their place of work and are traditionally the likeliest sources

of demand for housing within the city. The prevalence of remote working has increased due to

the COVID pandemic—but it does not yet appear to be a dominant feature of the labor market

even though it has likely grown significantly in recent years.

Anecdotal evidence from the focus groups discussed below indicates that many of those

purchasing newly-constructed, single-family homes were taking advantage of working remotely

for employers that were actually physically located in larger cities in southern New England and

are seeking the amenities and charms of a smaller city—like South Portland—to live in. It is

unclear as of the time of this report how long remote working will remain an available option for

workers currently residing in the city as the risks of the COVID pandemic have begun to recently

diminish. It is a labor market factor of potential importance as a source of additional housing

demand in the city that deserves to be watched—as acceptance of this type of remote work

arrangement potentially increases over the next decade as the importance of physical proximity

to one’s workplace potentially declines over the next decade.

Housing Needs Assessment and Strategy in South Portland Maine

Page 29 of 108

TRENDS IN PERSONAL AND HOUSEHOLD INCOME IN SOUTH PORTLAND

Personal Income

Employment measures only tell part of the economic story of a region. Personal income in South

Portland, the most broad-based measure of general purchasing power available at the local level,

amounted to over $1.57 billion in 2019. When measured in current dollars, Cumberland County's

total personal income more than doubled between 2000 and 2019. However, when measured in

constant 2012 dollars to adjust for inflation, the entire increase over the 19-year period amounted

to only 52 percent.

11

Personal income consists of three major components: 1) net earnings for labor services; 2)

property incomes; and 3) transfer receipts as detailed below. Net labor earnings ($991 million),

which accounted for 63.2 percent of the City’s total personal income in 2019, can be considered

payment for current labor services. Net earnings include wage and salary disbursements,

proprietors' income, and other labor income which are mostly employer contributions to private

pension and welfare funds. The contributions that individuals make to social insurance programs

(e.g., Social Security taxes) are excluded from net earnings.

The remaining non-labor portion ($577 million or 36.8 percent) of the City’s personal income was

split between dividends, interest, and rent (which is also called property income) and transfer

receipts. Wages and proprietor income are the return to productive labor, while dividends, interest

and rent are the return to fixed assets like stocks, bonds, and rental property. Property incomes

($339 million) account for 21.6 percent of the City’s income; above the MSA and national average.

Transfer receipts, the other portion of non-labor income, accounts for 15.2 percent of the City’s

personal income ($238 million); compared to the national share of 16.8 percent. Transfer receipts

are referred to as "unearned income," such as receipts from the government to people (and non-

profit institutions) for reasons other than labor services. Some people might think “welfare

payments” when hearing transfer receipts. However, “welfare” only accounts for about 5 percent

of transfer receipts in Cumberland County in 2019, with unemployment insurance benefits adding

just 0.6 percent. Transfers receipts are composed of the following leading categories: retirement

benefits (38.0 percent), medical benefits (44.5 percent), veterans benefit payments (4.2 percent),

federal assistance for education and training programs for individuals (5.3 percent), and

government payments to nonprofit institutions business payments to individuals (2.2 percent).

Retirement benefits and medical payments amount to over four-fifths of all transfer payments for

City residents. Together with the about 21 percent of personal income coming from dividends,

rent and interest, transfer receipts represents 33 percent of the regional economy. Put another

way, if one focused only on jobs and the money they bring in, one-third of the economy would be

ignored.

11

The U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis reports personal income data in current dollars--the basis of the value or

purchasing power of the dollar during the year in which the incomes are received. To remove the effects of inflation

and allow for direct comparison of personal income in terms of an approximation of real purchasing power over

time, constant dollar or real estimates of personal income are computed using the Implicit Price Deflator for personal

consumption expenditures (2012 = 1.00).

Housing Needs Assessment and Strategy in South Portland Maine

Page 30 of 108

Figure 1-18 Personal Income in South Portland ($Thousands), 2000-2019

Median Household Income

Median household income in the city was $69,290 in 2019, growing by $18,224 (in current dollars)

over the previous nine years. For resident homeowners, median household income in 2019 was

$87,435, while renters’ median household income was $47,101. In the nine years since 2010,

owners’ median household income has grown by $25,782 while renters’ median household

income has grown by a relatively modest $12,999. This represents a significant difference in

economic conditions and related opportunities experienced between owner and renter

households.

Table 1:7 Median Household Income of South Portland and Peer Communities, 1999, 2010 and

2019

Region/Municipality

1999

2010

2019

Annual Growth Rate

1999-2010

2010-2019

South Portland City

$42,770

$51,066

$69,290

1.6%

3.4%

Portland City

$35,650

$44,422

$60,467

2.0%

3.5%

Cumberland County

$44,048

$55,658

$73,072

2.1%

3.1%

Sagadahoc County

$41,908

$55,486

$63,694

2.6%

1.5%

York County

$43,630

$55,008

$67,830

2.1%

2.4%

Maine

$37,240

$46,933

$57,918

2.1%

2.4%

United States

$41,994

$51,914

$62,843

1.9%

2.1%

Source: U.S. Census Bureau and American Community Survey

Poverty in South Portland

Poverty levels in a community can be an indicator of the housing need for low-income households

within a community. Statistics indicate that 2019 poverty levels for all individuals range from a low

of 8.8 percent within the South Portland, compared to 14.6 percent in Portland and 11.8 percent

$-

$200,000

$400,000

$600,000

$800,000

$1,000,000

$1,200,000

$1,400,000

$1,600,000

$1,800,000

2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019

Net Earnings by Place of Residence Dividends, Interest, and Rent Personal Current Transfer Receipts

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, EPR

Housing Needs Assessment and Strategy in South Portland Maine

Page 31 of 108

for the State of Maine. Compared to all individuals, a greater share of children (under 18 years

old) is below the poverty line however, 14.7% within the city compared to 15.1% statewide.

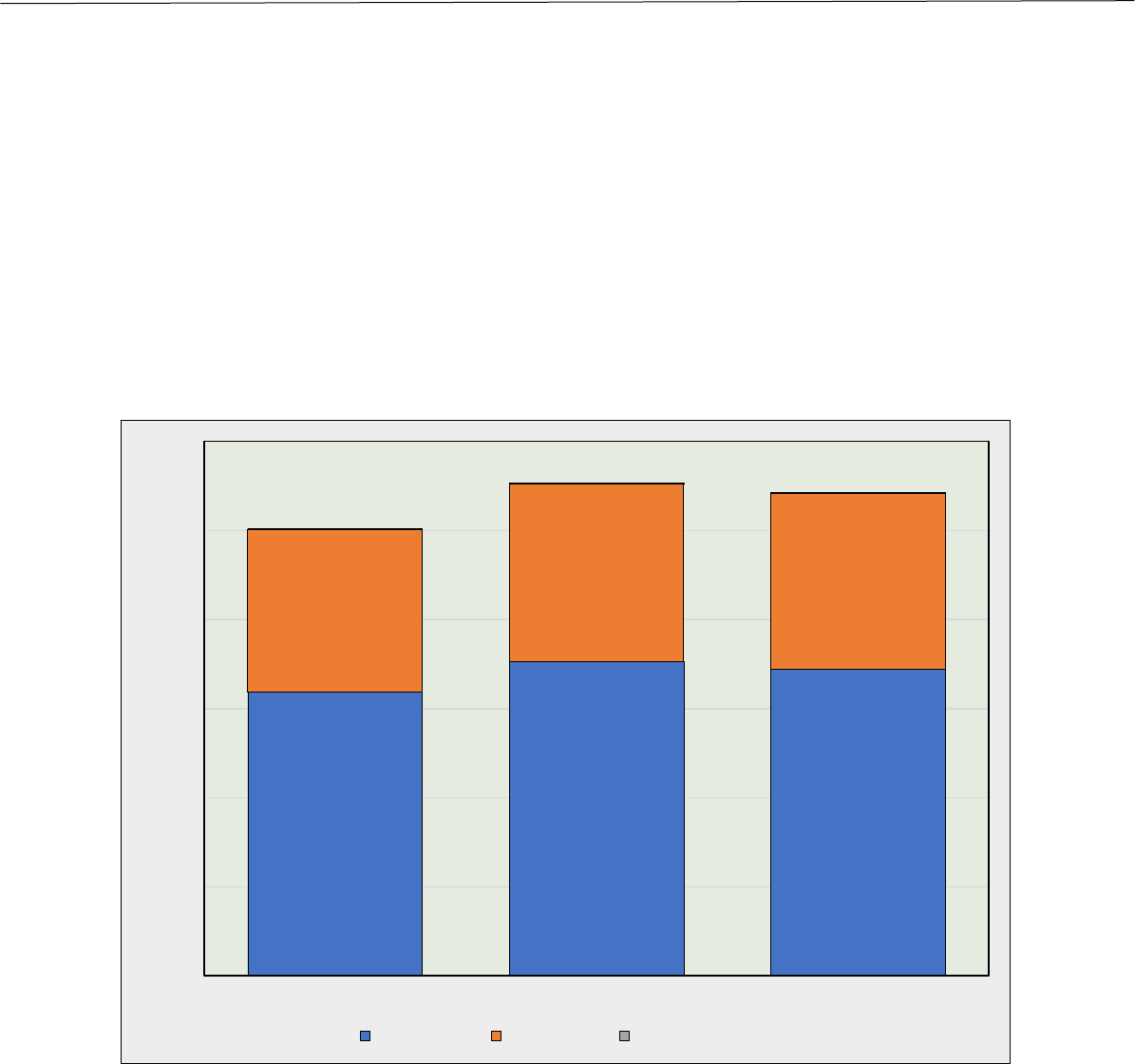

Figure1-19 People below the Poverty Level, 2010, 2013, 2016, and 2019

Figure 1-20 Children below the Poverty Level, 2010, 2013, 2016, and 2019

12.6%

10.5%

17.5%

10.4%

13.6%

11.4%

20.6%

12.3%

13.5%

11.1%

19.2%

12.3%

11.8%

9.0%

14.6%

8.8%

0.0%

5.0%

10.0%

15.0%

20.0%

25.0%

Maine Cumberland Portland South Portland

2010 2013 2016 2019

Source: American Community Survey

17.0%

14.4%

27.6%

17.4%

18.5%

15.7%

30.4%

21.3%

17.9%

13.8%

25.6%

18.4%

15.1%

9.8%

16.9%

14.7%

0.0%

5.0%

10.0%

15.0%

20.0%

25.0%

30.0%

35.0%

Maine Cumberland Portland South Portland

2010 2013 2016 2019

Source: American Community Survey

Housing Needs Assessment and Strategy in South Portland Maine

Page 32 of 108

Chapter 2 HOUSING SUPPLY IN SOUTH PORTLAND

Turning to the housing supply for the city and the county, the majority (63 percent) of housing

units within the city has historically been single-family units, however the share of single-family

units in South Portland compared to neighboring communities other than Portland is smaller,

indicating a more densified housing mix is available in the city. Only the City of Portland has a

lower percentage of single-family units as a share of the housing stock than South Portland, with

just 41 percent of its units in this category in 2019.

Over the past 19 years, the number of single- and multi-family units that have been added in the

city has roughly maintained the share of each housing type. As of the 2019, there were

approximately 6,884 single-family units along with 3,953 multi-family units and only 19 mobile

home/other units (Figure 2-1).

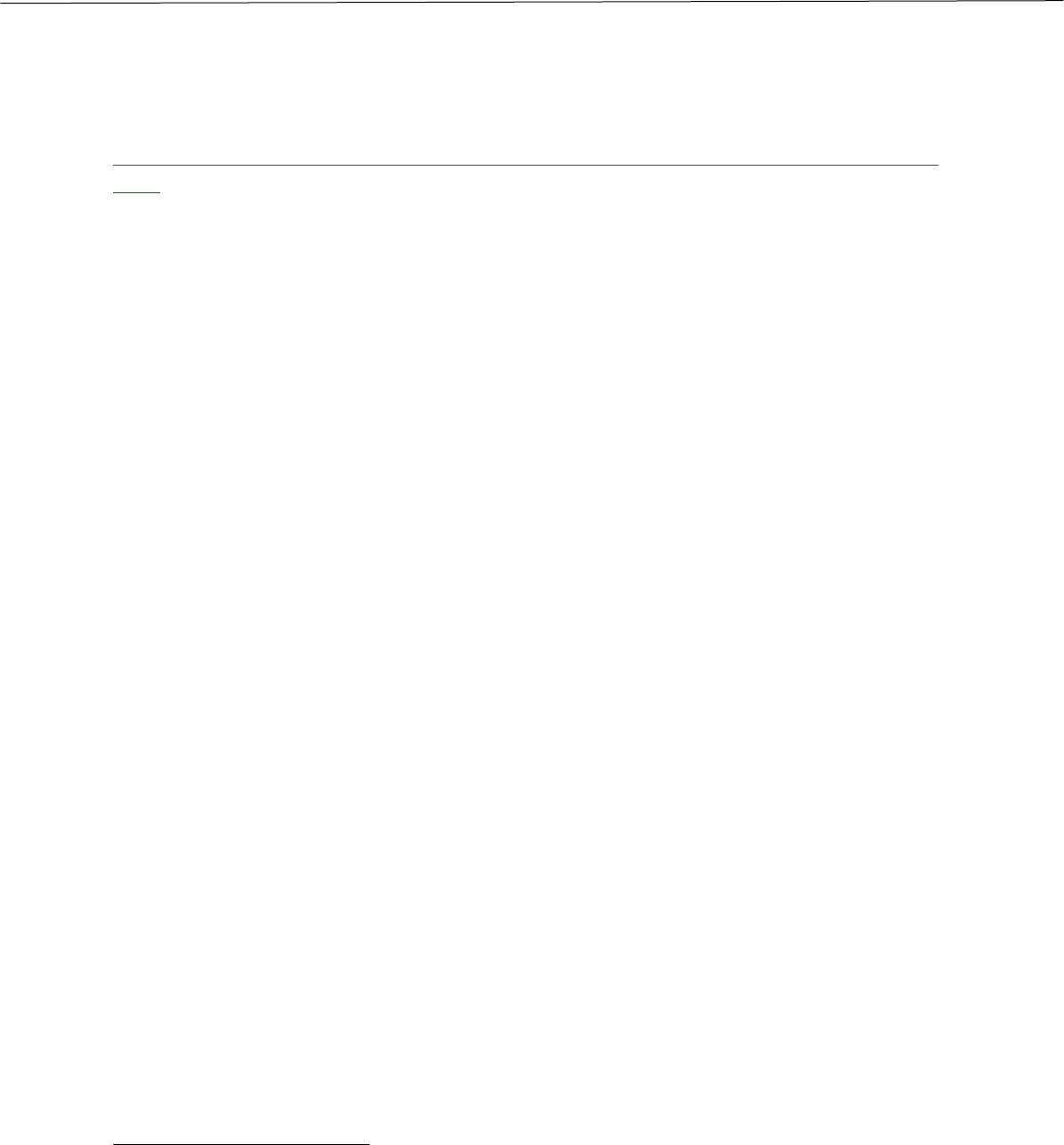

Figure 2-1 Housing Supply in South Portland in 2000, 2010, and 2019

Since 2000, there has been a slow conversion of single-family units from owner-occupied units to

renter-occupied units, and an increasing share of owner-occupied multi-family units (i.e., condos).

In 2000, 91.4 percent of single-family units were owner-occupied, declining to 86.7 percent in

2019. Similarly, in 2000 only 17.0 percent of owner-occupied unites were multi-family but that

share increased to 22.7 percent in 2019. This trend has quickened in just the last five years which

may indicate the relative affordability or availability of multi-family units as opposed to single family

units.

63.4%

63.4%

63.4%

36.5%

36.4%

36.4%

0.2%

0.2%

0.2%

-

2,000

4,000

6,000

8,000

10,000

12,000

2000 2010 2019

Single Family Multi-Family Mobile Home-Other

Housing Needs Assessment and Strategy in South Portland Maine

Page 33 of 108

Figure 2-2 Owner/Renter Single and Multi-Family Units in South Portland in 2000, 2010, and

2019

Building permit data can be a leading indicator of housing supply. Since the early 2000s, there

has been a marked reduction in the number of single-family building permits issued within the

city, peaking in 2003 with 127 units and declining to just 18 and 15 units in 2019 and 2020,

respectively. Multi-family unit permits are more sporadic but have increased notably in recent

years with permits for 204 units in 2019 and 260 units in 2020 (Figure 2-3) owing at least in part

to efforts from the City to expand affordable and low income housing. It can take several years

from the time permits are issued to when the housing units become available in the housing supply

or housing unit inventory. As a result, the city is very likely still feeling the “squeeze” of too few

new housing units added to the city’s housing unit inventory over the last decade, exhibited by

sharply escalating home prices.

Figure 2-4 shows the monthly sales volume and 12-month moving average of residential

properties (excluding condominium sales) in South Portland from January 2005 through

September 2021 based on South Portland’s Vision Government Solutions sales database. This

chart also shows significant seasonality in the housing market which is typical of most housing

markets in the northeast. To reduce confusion related to seasonal changes, a 12-month moving

average is included in Figure 2-3. Residential property sales peaked in 2006 at roughly 34 sales

per month before falling to 15 sales per month following the great recession. From 2012 to 2015

the number of transactions slowly increased and leveled off at 25 sales per month until January

of 2020. As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, sales volume initial decreased slightly during the

first half of 2020 but then rebounded in late 2020 and early 2021 to a level similar to that of 2006.

91.4%

5,822

90.8%

6,399

86.7%

5,967

17.0%

623

15.3%

612

22.7%

899

8.6%

545

9.2%

649

13.3%

917

83.0%

3,041

84.7%

3,394

77.3%

3,054

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

2000 2010 2019 2000 2010 2019

Single Family Multi-Family

Owner Occupied Renter Occupied

Housing Needs Assessment and Strategy in South Portland Maine

Page 34 of 108

Figure 2-3 Building Permits in South Portland in 2000-2020

Figure 2-4 Monthly Sales Volume of Residential Properties (and 12-Month Moving Average),

2005-September 2021

74

34

71

127

60

88

70

41

34

32 32

17

21

26

31

27

13

40

22

18

15

148

2

114

117

57

2

42

52

19

8

26

96

204

260

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020

Single Family Units Multi-Family Units

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

Jan-05

Aug-05

Mar-06

Oct-06

May-07

Dec-07

Jul-08

Feb-09

Sep-09

Apr-10

Nov-10

Jun-11

Jan-12

Aug-12

Mar-13

Oct-13

May-14

Dec-14

Jul-15

Feb-16

Sep-16

Apr-17

Nov-17

Jun-18

Jan-19

Aug-19

Mar-20

Oct-20

May-21

Housing Needs Assessment and Strategy in South Portland Maine

Page 35 of 108

Among owner-occupied units, the housing types or styles associated with sales have not varied

greatly since 2005. Over the last five years most residential property sales have been either

Capes (36.0 percent), Two Story (33.8 percent), or One Story (17.6 percent) structures; Raised

Ranches (4.5 percent), Bungalows (3.1 percent), and various Family Flats, Split-Levels,

Conventional, Family Duplexes, and Modern/Contemporary structures account for the remainder.

In contrast to the existing housing unit supply, new residential construction is overwhelmingly two-