Document Management

and Imaging

TOOLKIT

American Health Information Management Association

Document Management and Imaging Toolkit

2 | AHIMA

Contents

Foreword........................................................................................................................................... 4

Authors and Acknowledgments ..................................................................................................... 4

Introduction—Transition to the EHR using Document Management and Imaging Systems .... 5

Current Landscape and Supporting the EHR ................................................................................ 5

» Today’s Document Management System(s) .........................................................................5

» Using Document Management as the Legal Archive ...........................................................6

» Record Retention and Destruction ...................................................................................... 6

» Disaster and Contingency Planning .....................................................................................7

Document Management Operations and Best Practices ...............................................................8

» Discharge Processing .............................................................................................................8

» Turnaround Time (TAT) ....................................................................................................... 8

» Scanning Preparation ............................................................................................................ 9

» Document Capture ................................................................................................................9

» Productivity Monitoring ...................................................................................................... 10

» Reporting ..............................................................................................................................12

» Staffing During Transition ................................................................................................... 13

System Design Options and Considerations ................................................................................14

» Document Retrieval, Viewing and Distribution.................................................................14

» Workflow ..............................................................................................................................14

» Chart Completion ................................................................................................................ 14

» Integration ............................................................................................................................ 15

Implementation and Leadership .................................................................................................. 15

» Determining the Information Technology Strategy ..........................................................15

» Clinical Systems .................................................................................................................... 15

» Scanning Implementation Options .....................................................................................16

» The Implementation Phase .................................................................................................17

» Implementation Team Roles and Responsibilities ............................................................. 17

» Project Sponsors ................................................................................................................... 17

» Project Charter and Scope ................................................................................................... 18

» Work Plan ............................................................................................................................. 18

Updated 2012

AHIMA | 3

» Conversion Options: Outsourcing ...................................................................................... 18

» Testing ...................................................................................................................................18

» Training................................................................................................................................. 19

» The Post-Implementation Phase ......................................................................................... 20

Case Study: “The EHRs Impact on Staffing and Turnaround Times:

Centralizing the HIM Department in a Multi-Facility Environment” ....................................... 21

Appendices

» A: Best Practices: Preparing and Scanning Documentation .............................................. 25

» B: Document Storage Options and File Size Calculations ................................................. 27

» C: Bar Code Information and Guidelines ........................................................................... 29

» D: Prepping Skill Set ............................................................................................................ 30

» E: Scanning Skill Set ............................................................................................................. 32

» F: Indexing Skill Set .............................................................................................................. 33

» G: Review and Quality Control Skill Set ............................................................................. 36

» H: DMS and EHR Points of Integration Table ................................................................... 38

Copyright ©2012 by the American Health Information Management Association. All rights reserved. Except as permitted

under the Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted,

in any form or by any means, electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission

of the AHIMA, 233 North Michigan Avenue, 21st Floor, Chicago, Illinois, 60601 (https://secure.ahima.org/publications/

reprint/index.aspx).

ISBN: 978-1-58426-394-4

AHIMA Product No.: ONB185012

AHIMA Staff:

Anne Zender, Editorial Director

Claire Blondeau, MBA, Managing Editor

Jessica Block, MA, Assistant Editor

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: This book is sold, as is, without warranty of any kind, either express or

implied. While every precaution has been taken in the preparation of this book, the publisher and author assume

no responsibility for errors or omissions. Neither is any liability assumed for damages resulting from the use of the

information or instructions contained herein. It is further stated that the publisher and author are not responsible for

any damage or loss to your data or your equipment that results directly or indirectly from your use of this book.

The websites listed in this book were current and valid as of the date of publication. However, web addresses and the

information on them may change at any time. The user is encouraged to perform his or her own general web searches

to locate any site addresses listed here that are no longer valid.

CPT® is a registered trademark of the American Medical Association. All other copyrights and trademarks mentioned

in this book are the possession of their respective owners. AHIMA makes no claim of ownership by mentioning

products that contain such marks.

For more information about AHIMA Press publications, including updates, visit www.ahima.org/publications/updates.aspx

American Health Information Management Association

233 North Michigan Avenue, 21st Floor

Chicago, Illinois 60601

ahima.org

Document Management and Imaging Toolkit

4 | AHIMA

Foreword

This toolkit has been developed to advance knowledge and

practice of document management and imaging and its role in

supporting the electronic health record (EHR).

It begins with the current document management and imaging

landscape in supporting the adoption of the EHR, continues

with document imaging operations and best practices, and

concludes with system design options, considerations, imple-

mentation, and leadership. The toolkit includes one case study

and eight appendices where more details, including tables, are

provided to enhance the main content.

Authors

Michelle Charette, RHIA

Kay Davis

Julie A. Dooling, RHIT

Kathy Downing, MA, RHIA, CHP, PMP

James Foster, MHA, RHIA

Jennifer Ingrassia, RHIA

Jamie McDonough, RHIA

Heather Rogers, MBA

Blake Sawyer

Traci Waugh, RHIA

Patrick Williamson

Acknowledgments

Cecelia Backman, MBA, RHIA, CPHQ

Jill S. Clark, MBA, RHIA

Angela Dinh Rose, MHA, RHIA, CHPS

Barry S. Herrin, JD, CHPS, FACHE

Sharon Silvochka, RHIA

Diana Warner, MS, RHIA, CHPS, FAHIMA

Lou Ann Wiedemann, MS, RHIA, FAHIMA, CPEHR

AHIMA e-HIM Work Group on

Electronic Document Management

as a Component of EHR:

Acknowledgements

This toolkit is based on a 2003 practice brief

originally developed by:

Beth Acker, RHIA

Maria A. Barbetta, RHIA

Kathy Downing, RHIA

Michelle Dougherty, RHIA

Deborah Fernandez, RHIA

Beth Friedman, RHIT

Nancy Gerhardstein, RHIT

Darice M. Grzybowski, MA, RHIA, FAHIMA

Beth Hjort, RHIA, CHP

Susan Hull, RHIA

Deborah Kohn, MPH, RHIA, CHE, CPHIMS

Amy Kurutz, RHIA, PMP

Roderick Madamba, RHIA

Therese M. McCarthy, RHIA

Pat McDougal, RHIT

William Kelly McLendon, RHIA

D’Arcy Myjer, PhD

Lori Nobles, RHIA

Jinger Sherrill, RHIA

Patty Thierry Sheridan, MBA, RHIA, FAHIMA

Michelle Wieczorek, RN, RHIT, CPHQ, CPUR

Sarah D. Wills-Dubose, MA, M.Ed., RHIA

Updated 2012

AHIMA | 5

Introduction

Transition to the Electronic Health Record using

Document Management and Imaging Systems

Document management systems (DMSs) continue to play a very

important part in capturing all the documentation needed to

tell the patient’s story. They allow for capture and simultaneous

access to needed documentation and chart completion and

provide a central repository of information. While the use

of paper will continue to decrease over time, document

management systems ultimately will support the electronic

health record (EHR) transition. These systems will manage

paper that continues to flow from the EHR, legacy systems, or

from external entities to ensure processes are fluid for users, and

act as a legal archive.

Assessing, selecting, implementing, and maintaining a DMS is

an investment. Optimizing your investment and leveraging

technology allows for cost savings and increased efficiencies.

During the EHR transition, it is important for the health

information management (HIM) professional to become and

stay involved in order to ensure the department’s processes

and integration points to the EHR are incorporated into

the project.

Meaningful use standards (and the accompanying opportunity

to receive federal subsidies) are driving the adoption of EHRs.

With the increased use of EHRs, it is more important than

ever for the information stored outside the EHR to be available

electronically. DMSs are a vital partner in capturing paper so

that information can be incorporated into or accessible from

the EHR.

Current Landscape and

Supporting the EHR

Today’s Document Management Systems

The terms Document Management System (DMS) and

Enterprise-wide Document Management System are frequently

used interchangeably. For the purpose of this toolkit, we will

focus on DMSs used in the HIM department to enable and

support the transition to the EHR. DMS simply refers to the

management of documents, and in this toolkit, we will be

referring to documents electronically captured for inclusion

in the health record.

The DMS is often referred to as the software used primarily

by HIM departments to handle the clinical and administrative

documents pertaining to a patient’s treatment. These are docu-

ments that are either unable to be built for use directly in the

EHR or have not yet been built. These documents are typically

scanned or acquired electronically post-discharge, but may also

be scanned or captured concurrent to the episode of care at

point of service. Other processes pertaining to the DMS include

chart completion, workflow, and release of information (ROI).

DMSs are also used throughout an organization to help reduce

the amount of paper that must be handled and tracked.

Organizations frequently use the same vendor for all their

document management needs, not only in HIM, but also in

areas such as human resources, patient financial services,

purchasing, registration, and the medical staff office, to name

a few, but it is the branching out to other business areas of

the organization that turns the DMS into an enterprise-wide

application.

Even as organizations make significant investments in a wide

range of separate patient-centric systems, there is a continued

need for DMS. DMS enables capture and access for many areas

across the enterprise. Multiple locations exist in the enterprise

where information regarding or influencing patient care can be

stored in the EHR. Although information can be captured and

accessed directly throughout these systems, the EHR is typically

the environment that holds this consolidated information.

The most important reason for acquiring and implementing a

DMS is to capture and manage the organization’s documents,

not to eliminate paper. Documents are organizational assets.

Organizations must respect the necessity and strategic impor-

tance of managing its document assets just like the organiza-

tion’s data, information, and cash assets.

Organizations must properly manage documents; their failure

to do so not only increases liability, but also risks information

loss that can significantly affect patient safety and quality of

care. Accordingly, many organizations are forming governance

committees to identify and establish ownership of information

repositories such as document management systems. When

HIM professionals assume ownership of the information, they

also assume stewardship or accountability for the decisions

made with regard to information management. When new

systems are implemented, integrations and migrations occur

to consolidate data or for decision making when archiving,

retrieving, retaining, or destroying information.

It is critical to incorporate process improvement principles

when working with people, processes, and technology. Until

the time that all internal and external (that is, outside the

organization) documents are captured, indexed, and distribut-

ed electronically to the EHR, technologies such as classification

recognition (such as bar coding, optical character recognition),

point of service scanning, and work flow enhancements will

continue to enhance productivity and help to achieve quality

standards in the DMS.

Document Management and Imaging Toolkit

6 | AHIMA

HIM professionals must be included in the DMS enterprise-

wide strategic plan to ensure that HIM standards of practice

(including regulatory requirements) are met as the organization

is crafting its strategy for years to come. The following questions

that pertain specifically to the HIM department should be con-

sidered as the overall institutional DMS strategy is developed:

» What are the long-term goals for the following HIM processes?

» Defining and maintaining the designated record set (DRS)

and legal health record (LHR)

- Accuracy, integrity, and accessibility of information

- Chart retrieval and viewing

- Document capture

- Chart completion, including electronic signature and

deficiency management

- ROI, including printing and exporting guidelines

- Coding, abstracting, and migrating to ICD-10-CM/PCS

- Transcription

- MPI maintenance

- Storage, retention, and destruction

- Downtime or contingency planning

- HIPAA, Joint Commission, CMS, and other regulatory

compliance

- Document management and information obligations

imposed by health information exchange and accountable

care organizations

» How do these HIM processes relate to clinical systems? For

example, how will verbal order signatures be tracked, who

will track them, and what impact will this have on computer-

ized provider order entry (CPOE) systems?

» How are documents created, generated, and transitioned for

CPOE implementation?

» What are the organizational goals surrounding decentralized

versus centralized scanning?

» How will seamless integration with clinical systems be

achieved?

» What HIM requirements are included in the organization’s

clinical health information systems and how will these be

incorporated into request for proposals (RFPs) and procure-

ment processes?

» What plans are instituted to promote physician and other

clinician acceptance of organization-wide electronic document

management? For example, will DMS functionality require

online medical record access and chart completion?

Using Document Management

as the Legal Archive

The legal health record (LHR) is comprised of those docu-

ments and data elements that a healthcare provider considers

its official record of patient care. The “source of truth” or the

official source system that you will use to respond to requests

for copies of the LHR must be identified and included in an

organization’s LHR definition. During the EHR transition, the

definition will need to be modified as documents move from

being captured in the DMS to being created or captured in the

EHR. There may be dual responsibilities for storing the LHR

where portions of the record are stored in multiple places after

a certain date if you are unable to integrate historical data from

your DMS into your EHR.

With the existence of preliminary and final versions of a

document, as well as original and corrected information, a

healthcare organization must address the management of

document versions. Once documentation has been made

available for patient care, it must be retained, managed, and

incorporated into the LHR whether or not the document

was authenticated. A decision must be made on whether all

versions of a document will be displayed or just the final, who

has access to the various versions of a document, and how the

availability of versions will be flagged in the health record.

Communication with stakeholders is critical when workflow

changes are implemented and a document in the DMS is now

being created and managed in the EHR. As more tools (such as

interfaces, integrations, and workflow) are introduced into the

organization, the processes in place and the flow of information

must be reconsidered to ensure that the process remains efficient

and information remains accurate. The tools available to manage

and access the medical record are changing and, therefore, so

must the approach to working with the new tools. Integration

tools between DMS and the EHR should decrease the amount of

manual work required to manage the health record, resulting in

increased efficiency and accuracy in processes.

For more information on integration, see “Integration” under

“System Design Options.”

Record Retention and Destruction

A provider’s records retention policy establishes how long an

organization should keep documents, the medium in which the

information will be kept, and where the records will be located.

Existing retention schedules will likely need to be updated to

reflect new document groupings when a new DMS is installed.

The record retention schedule is a critical component to plan-

ning a DMS implementation and works in conjunction with

the destruction policy (see below). The length of the retention

Updated 2012

AHIMA | 7

period will determine in part the access, maintenance, and

migration activities that must be factored as part of the imaging

system’s ongoing maintenance and storage costs. Those costs will

continue to accrue for as long as the documents are retained.

All healthcare records, including those stored in a DMS, should

be maintained and disposed of as part of a legally accepted

information and records management policy in order to ensure

their acceptance as legal documents. Policies should include

descriptions of how long information must be maintained and

retained. They should be based on federal requirements and

the statute of limitations for each state, community practice,

and accreditation agency. The principles of retention and

destruction are critical to electronic discovery (e-discovery)

procedures and the use of electronic evidence. Legal counsel

should always be sought when constructing or revising these

policies.

While there are no set standards regarding how long the con-

verted records should be maintained, destruction of the paper

should be carried out in accordance with federal and state law

and pursuant to an approved organizational retention schedule

and destruction policy. The destruction policy must be clearly

communicated throughout the organization. AHIMA’s updated

“Retention and Destruction of Health Information” practice

brief will provide additional guidance on record retention stan-

dards and destruction of health information for all healthcare

settings.

Once a paper record has been converted to electronic media,

it is standard practice that the paper is boxed up after it has

been scanned, indexed, and released into the DMS or uploaded

to the EHR. The HIM department should provide adequate,

secure space for the retention of these records while they are

being processed and moved throughout the quality assurance

and corrections process.

Organizations should have processes in place to track complet-

ed records and the ability to run reports listing charts that have

been released to the DMS or EHR within a certain timeframe

to aid in identifying those charts that are eligible for destruc-

tion (for example, a report that shows all records that have

been released more than 90 days from today’s date).

Organizations should have a plan in place to destroy the

paper-based records that have been incorporated into the EHR

as soon as possible. The case can be made for destroying the

paper when users have confidence and trust that the informa-

tion has passed the quality assurance process, was properly

converted and readily available in the DMS.

Disaster and Contingency Planning

Preparing for disaster is a must whether it is a natural disas-

ter such as a flood or earthquake, a man-made disaster such

as theft or terrorism, or an unintended man-made disaster

such as an “error and omission” or fire due to a faulty system.

Developing a business continuity plan (BCP) is the overarch-

ing approach to business recovery; the BCP generally contains

individual plans for restoring departments back to business

quickly after any type of interruption that disrupts normal

healthcare operations.

A downtime or contingency plan focuses on sustaining a busi-

ness function during short interruptions that are not classified

as a disaster. Downtime may be planned or unplanned and

both scenarios must include alternative ways of conducting

business during this time. When creating a contingency plan,

management must consider the following:

» Identify personnel responsible for each portion of the con-

tingency plan, and include a list of duties for the staff when

systems are down. For example, consider redistribution of

workload so that all staff perform document preparation or

other paper-based activities until systems are restored.

» Determine which applications and computer systems the

HIM department relies upon in order to function.

» Identify the criticality of those applications and computer

systems.

» Create temporary work-around procedures that will be

implemented during system interruptions.

» Decide when and how to activate escalation procedures in

order to provide continuous patient care and maintain the

workflow of information for business operations.

» Decide how data captured on paper can be entered into the

DMS once systems have been restored.

» Determine a plan for varying lengths of downtime and how

staffing will be impacted. Consider differences in operations

when down time lasts for less than four hours, four to eight

hours, or more than a full shift.

» Determine a plan to validate system data for accuracy after

the DMS is restored.

For more information on developmental steps of a facility’s

disaster plan relative to the collection and protection of health

information, including a sample contingency plan, see the

updated “Disaster Planning for Health Information” practice

brief.

Document Management and Imaging Toolkit

8 | AHIMA

Document Management Operations

and Best Practices

Discharge Processing

Timely capture of information, whether post-discharge or

after a patient encounter, is critical. Discharge processing is a

fundamental process that ensures timely pick-up and receipt of

health information for scanning. Although this process is not

new to HIM, this process starts the turnaround time clock and

drives the entire document imaging process from beginning

to end or, in the DMS environment, from patient discharge to

availability in the EHR.

The remediation process includes tracking, accounting, and

following up on all discharges (inpatient, outpatient, emergency

department, and physician office, if applicable) to ensure all

information has been received. While HL7 and ADT feeds are

used for various reasons within a DMS, discharge processing

uses HL7 to facilitate remediation.

Organizational teamwork should be strongly encouraged

within this process. For documentation to be readily available

for scanning as soon as possible after the discharge, an inter-

nal policy that outlines expectations is suggested. Consider

the case of a patient returning to the emergency department

(ED) 24 hours following her initial visit and a subsequent visit

to a nursing floor. If the information from the initial visit has

not been completed by the clinician(s) in the ED and sent

for scanning, the patient’s health information is not available

to the healthcare team, which can create a patient safety risk.

Thus, a scramble ensues to find the record and have it scanned

immediately.

The following should be considered when making process

decisions:

» During what shift(s) will the records be picked up?

- A schedule that lists every day of the week with the pickup

location and time should be in place.

- Consideration must be given to heavy discharge times—if

your highest discharge time window is 5 to 7 p.m., then a

9 p.m. pickup may be in order.

- Holiday schedules should be made well in advance with

anticipation of volume uptake due to increase in discharges

prior to the actual holiday.

- Seasonality should also be considered when scheduling

records pickup, especially during flu and peak tourist

season(s).

» How will records be transported?

- If records are created at multiple locations, will a courier be

needed to transport records?

- What security protocols are in place to secure the protected

health information (PHI)?

» Is the scanning flow documented?

- Does your staff know how a chart moves through the

scanning process from beginning to end?

- Does the process consider all retrieval needs such as

coding, chart completion, ROI, audits, and readmissions

as in the example above?

- Do you have a procedure in place for scanner downtime?

- Do you have a procedure for when the paper record is

requested and needs either to be copied or taken out of the

department for patient care?

Turnaround Time

Turnaround time (TAT) starts at patient discharge and ends

when the images are released into the DMS or EHR.

The first step in calculating the desired TAT is to define the

parameters of TAT, such as

» What is the desired TAT to have records available post

discharge?

» Will each patient type or service type have its own TAT goal?

For example, will ED charts be held to a 12-hour TAT while

inpatient discharges are held to a 24-hour TAT?

» Will high dollar charts be processed first if TATs are not being

met?

» Will emergency department document types take priority

over loose sheet document types?

» Will certain discharges be best processed during a particular

shift?

Whether document management is performed in-house or

outsourced, TAT terms can be mutually agreed upon before

implementation begins. These metrics will assist in prioritizing

the chart procedure and can dictate the workflow of each day

starting with the chart collection schedule.

As a general rule, as part of the implementation process, it is

necessary to work with stakeholders such as clinicians, depart-

ment heads, and HIM staff to determine their requirements

and expectations surrounding documentation availability.

For example, ED records may need a faster TAT compared to

inpatient discharge records. The targeted TAT goal is 24 hours;

however, this goal is usually met only following a six-month

adjustment period post-implementation. Meeting TATs on

Updated 2012

AHIMA | 9

a consistent basis requires a “Plan-Do-Check-Act” cycle for

continuous quality improvement. It also requires management

to closely monitor and improve upon all areas of the scanning

process (prepping, scanning, indexing, quality assurance, and

identifying documents that can be computer output to laser

disc [COLD] fed to your DMS).

For more information on TATs, see the case study “The Elec-

tronic Health Record’s Impact on Staffing and Turnaround

Times: Centralizing the HIM Department in a Multi-Facility

Environment.”

Scanning Preparation

Chart preparation is the most time consuming and critical task

in the document imaging process. If the process is performed

correctly and efficiently from the beginning, it could reduce the

time spent manually indexing.

The document preparation process is the equivalent of chart

assembly and loose material sorting in the paper chart environ-

ment. The document preparation process involves grouping,

identifying, and preparing health record documents prior to

scanning so they can be captured efficiently.

Newer intelligent document recognition technologies can ease

the labor burden and quality issues associated with traditional

prepping. This technology can be used to classify document

types and patient demographic information.

Careful consideration must be given to handling “blank sides.”

The organization must create a plan and involve the technolo-

gy vendor and information technology in the decision making

process:

» Will the DMS capture all pages (front and back)?

» Consideration must be given to if the DMS technology has

the ability to delete blank pages or if staff will be trained on

identifying pages to be deleted?

» Who will have the rights to delete?

» In which phase of the process will this be performed? Will

blank pages be flagged at time of prepping such as page 4

of 4, caught during the QC process or will both teams be

responsible for monitoring and handling blank sides?

» Fee structures with third party vendors must be clearly

defined. It is critical that capture and charge of blank pages

be clearly defined and understood in the contract phase.

For additional information on productivity, see the Productiv-

ity Monitoring section of this toolkit. In addition, for informa-

tion on preparation, capture, and scanning best practices, see

Appendix A, “Best Practices: Preparing and Scanning Docu-

mentation.”

Document Capture

Understanding and managing the capture process is critical.

While document capture may be performed using a variety of

technologies, including scanners, electronic forms, electronic

transactions, cameras, voice, and video. For the purpose of this

toolkit, we will focus on scanning and electronic integrations.

Efficient document scanning can be achieved by utilizing a

centralized approach, a decentralized approach or a blended

or hybrid approach. Healthcare organizations must decide

which capture model will work best in their environment by

evaluating the size and type of organization, staffing, technol-

ogy, and other resources that are available to make the project

a success.

Centralized scanning requires that all documents within an

organization be sent to a central location for document capture

through high-volume scanning technology. Depending upon

the size of the organization, documents may be delivered

internally to the designated scanning location or they may be

delivered via courier.

Decentralized scanning requires small scanners being placed

at patient registration areas, nursing floors, physician office,

outpatient clinic locations, emergency departments, and other

on- or off-site locations. As paper documents are completed,

they can be scanned and indexed immediately or placed in a

queue for indexing later. Decentralized scanning allows more

of the documents to be captured prior to a patient’s discharge

rather than the scanning being done within HIM after dis-

charge. Registration information such as insurance cards and

advance directives can be available immediately for benefit

verification and patient care. Many organizations are using a

blended or hybrid approach to documentation, using central-

ized and decentralized scanning throughout their facilities. For

example, although a hospital may have a centralized scan-

ning location in the HIM department to scan post-discharge,

decentralized (point of care or point of service) scanning may

be used to capture documentation such as a driver’s license and

insurance card at registration that may be needed as the patient

moves through their visit.

Scanner size, speed, and functionality must be thoroughly

investigated before acquisition and implementation to under-

stand how the equipment will handle volume and certain doc-

ument types. It is critical to purchase a scanner that is capable

of handling expected volume particular to the organization’s

needs and scanner speed and functionality are directly related

to productivity. It is also important to know the functionality

of the equipment to evaluate document types for special han-

dling. For example, can the scanner accept scanning of strips

(such as telemetry) up to a certain length? Will the paper need

to be cut in the preparation stage?

Document Management and Imaging Toolkit

10 | AHIMA

When evaluating document capture methods, focusing on

capturing electronic transactions automatically will increase

the volume of capture at the beginning of the project since it

involves less labor. Electronic transactions include faxes, those

documents received via COLD or electronic record manage-

ment (ERM) systems.

It is important to consider data and image storage require-

ments as planning is underway for transition to a DMS. This

is important even if the organization intends to use an EHR

to store the majority of health information because electronic

storage needs for images can be quite large and will grow over

time.

For more information on data storage for scanned images,

refer to Appendix B, “Document Storage Options and File Size

Calculations.”

To enhance the document capture process, consideration

should be given to the following tools:

» Patient labels: Many organizations have policies that require

placement of a patient label on every page to identify the

patient. Data elements include the patient’s name, medical

record number, and other identifiers such as an encounter

number, visit number, etc. This practice follows best practice

and patient safety initiatives.

» Bar coded separator sheets: Many times form redesign takes

months to complete. However, scanning operations may need

to begin before this process is completed. Many systems allow

the use of bar-coded separator sheets for each section of the

record as a precursor to complete forms redesign. Inserted

into a chart during the prepping stage, the separator sheet

contains the bar code for the next group of documents (such

as nurses’ notes, orders, and such). This method requires

more preparation time than bar coded forms, but it can act

as an interim solution with higher accuracy and speed than

could be accomplished by manually indexing each form.

» Forms redesign: One of the goals of forms redesign is to

identify and describe the form characteristics required to

ensure successful form identification when using a DMS.

Complying with bar code design specifications will ensure

the highest level of accuracy when using bar code recogni-

tion software. It also helps to identify form characteristics

required to ensure better accuracy using forms recognition

features of an optical character recognition (OCR) or intel-

ligent character recognition (ICR) engine.

- Key points to consider include the following:

•Eachtypeofformneedsitsownbarcodesothatitcan

be automatically recognized when scanned.

•Formnamesshouldbeuniquetotheformandrecog-

nizable to the people who will be using the forms even

occasionally.

•Anyrequirementsforthetypeofformname,lengthof

name, bar code font, size of font, and such should care-

fully meet the requirements of the DMS and the EHR (if

applicable).

» Bar code types: The best approach to scanning health records

is to use 100 percent bar-coded forms. The longer an organi-

zation waits to incorporate 100 percent bar-coded forms, the

less productive the scanning process will be. Although this is

normally very difficult to achieve at the beginning of a scan-

ning project due to the volume of forms that need bar codes

and the presence of outside documents that are not consis-

tent in appearance, the process of bar coding forms should

begin as soon as possible.

» Code 3 of 9: Most DMSs support the Code 3 of 9 (also

referred to as Code 39) bar code standard (see example in

figure 1.1 below). This is an alphanumeric, self-checking,

variable-length code that employs five black bars and four

white bars to define a character. Furthermore, three of these

bars are wide, and six of these bars are narrow. The wide

bars or spaces are at least two, but preferably three, times

the width of the narrow bars or spaces. When implement-

ing DMS using bar codes, it is important to understand the

bar code specifications, the bar code content, and the issues

related to bar code placement on the form.

Figure 1.1—Sample 3 of 9 bar code

» 2D: In addition to the 3 of 9 bar code standard, additional

types of bar codes are growing in use in the United States

(see example figure 1.2). There has been rapid expansion of

the use of two dimensional (2D) bar codes in advertising and

other commercial settings, and we have begun to see applica-

tions for use in the healthcare environment.

Examples of 2D bar codes include QR codes, which can be

read by a cell phone with the correct application downloaded,

or through the use of Aztec bar codes. The 2D bar code

format has a few benefits over the 3 of 9 format, including

the ability to store a larger amount of data, direct a user to a

website, and enabling sorting or finding a particular form or

page. They also lend themselves to the ability of being used in

a more demanding environment such as in a clinical setting

where they can be used on the wrist or ankle bands for new-

borns. In this setting, the format is better suited to a small

size and curvature of the band when placed on an infant. It

will be important to consider the next generation of bar-

Updated 2012

AHIMA | 11

coding fonts as well as recognition capabilities when selecting

a document management vendor to ensure that needs will be

met as the technology evolves.

Figure 1.2.—Sample 2D bar code

See Appendix C, “Bar Code Information and Guidelines,” for

additional guidance.

Productivity Monitoring

The ability to monitor performance is vitally important when

managing the document imaging process whether the work is

being performed on- or off-site, by the organization’s employees

or by a third party such as a document imaging vendor. Setting

productivity expectations is critical to managing document

imaging, and the following guidance should be taken into

consideration when creating productivity monitoring standards.

Productivity monitoring starts with being able to adequately

measure processes. Charts vary greatly in size and image

count, so assigning a number of charts to a staff member who

prepares them is not an accurate measurement. Many organi-

zations use inches or weight to measure for performance and

whether manual entry or computer entry into the document

management system is used, a procedure should be in place

outlining the process and recording of numbers.

With the understanding that every organization has differ-

ent documentation practices, internal processes, approaches

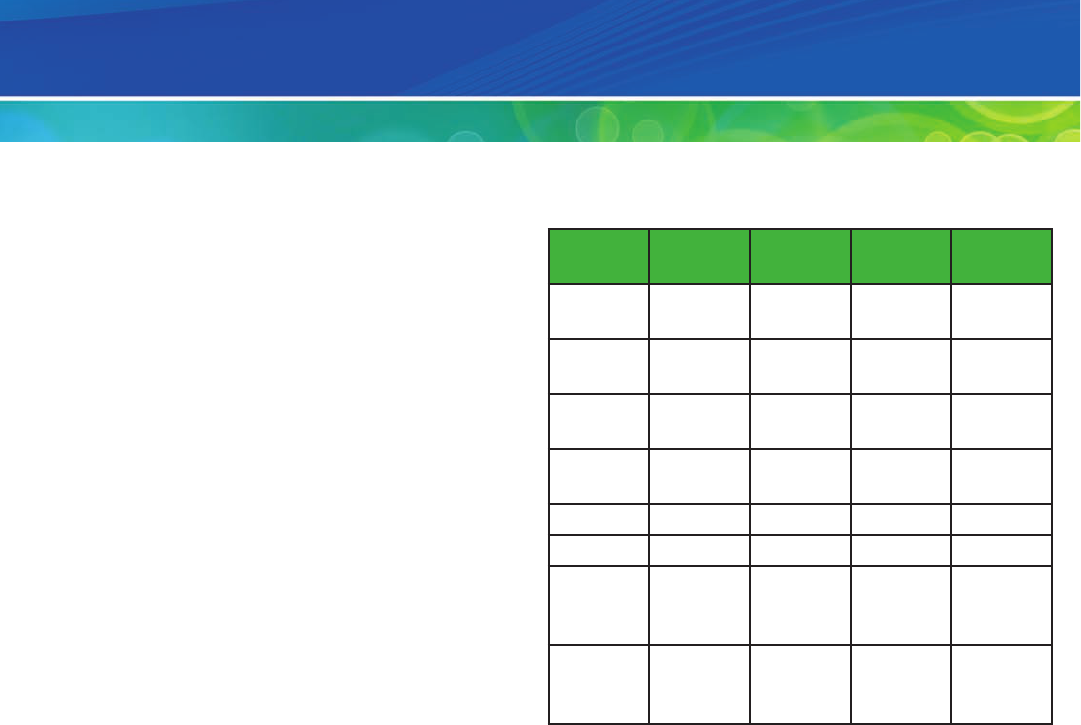

to technology, and strategic goals, the following (figure 1.3)

recommendations are provided as a “general rule” to assist

with creating departmental or organizational standards. The

figure shows each production step from preparation to index-

ing with corresponding initial rates (typically during the first

six months following implementation) and final rates (those

rates at the highest end of the proposed goal). Rates below

are shown as images per hour (IPH) per person. They have

been shown to be typically observed for each process. To avoid

backlog situations, the prepping and indexing rates should

be closely coordinated. Prepping will typically be faster than

indexing in the beginning, which is why the initial rates listed

below show prep at a higher rate when compared to index-

ing. Managers should adjust staffing in these areas to meet

anticipated volumes and scanning throughput. Also, these

rates take into account that these tasks are the sole focus of the

staff member during this monitoring time when the volume is

maximized.

Figure 1.3 — Sample production rates

It is also very important to recognize that scanner metrics vary

depending upon the size and speed of the scanner. For example,

larger scanners used for volume scanning operate much

faster than a desktop scanner used to capture driver’s licenses,

advanced directives, and such. Standards should be tailored

to the type and speed of the scanner being used. For example,

a scanner that captures 2,500 images per hour would have a

maximum capture rate for volume or batch scanning.

Indexing programs can also vary depending upon the steps

involved in the process. The number of required fields and

processes will affect productivity.

Quality control (QC) should be included in every step of

the document imaging process, from receipt to release into

the DMS or EHR. A comprehensive and well-executed QC

program will help to create trust in record integrity for all users

of the health record, and it is an important component to the

overall success of the document imaging program. The goal of

the quality program is to achieve the highest level of accuracy

through index verification and scan quality.

The following should be considered when creating QC policy

and procedures:

» Consider overall organizational strategic goals when framing

DMS expectations and results.

» During prepping, QC measures may include whether or not

primary documents are included:

- Are documents in order according to specific prepping

guidelines set forth by the organization?

- Are missing information or documents present?

- Are flags or notes used properly to identify missing parts of

the chart?

» Image quality, as well as content legibility, should be reviewed

while identifying and validating data elements as defined by

the general business rules set forth by the organization:

- All pages should be oriented to the correct reading position.

Rotate any images that appear to be upside down or

sideways.

Document Management and Imaging Toolkit

12 | AHIMA

- Patient information on all pages must be verified with

accurate indexing to the patient, account, and document

types levels. One task may include matching the identify-

ing number (such as account number or medical record

number) and patient name on the bar code to the remaining

pages in the batch.

- Delete any blank pages without information as well as bleed

through pages. For more on blank sides, see section titled

“scanning preparation” contained within this document.

- A process should be in place to remediate the number of

physical images scanned to the number of images captured

in the software.

» While some organizations prefer to conduct QA reviews on

100 percent of scanned documents, others use a hybrid

approach including random sampling or a certain percentage

of documents to ensure accurate document capture. This

approach should be determined by each organization based

on what is right for its particular situation, taking risk,

staffing, and budget into consideration.

» Note: Some DMS solutions contain the ability to monitor the

entire scanning process (from prep to release) in real-time

and are able to provide quality reporting post scanning such

as number of imaged captures, number of blank pages, and

such.

Quality Point System

Staff can be evaluated using a quality point system in conjunc-

tion with metrics and number of errors. Depending on the

severity of an error, the employee would be assessed a certain

amount of points within a review period. Errors such as mixed

accounts or patients, missing images or pages, overlapping

pages, or poor-quality images could be considered a critical

or severe error while blank pages, unnecessary images, skewed

images, or an incorrect document type could be considered a

low-impact error. One formula that is used to measure quality

is the percentage of actual errors as compared to the total re-

cords processed divided by the total cost of operations (includ-

ing staff, hardware, software, furniture, space, maintenance,

supplies, and such). This figure is then divided by the time it

takes from receipt of the record to the time it is released into

the EHR. The result is typically are double digit numbers where

the higher value indicates better performance.

1

All quality pro-

grams should be reviewed by human resources and approved

by senior management prior to implementation.

Reporting

Communication through reporting is a vital component to

managing a DMS. It is important to work with the DMS

vendor to understand the system’s reporting capabilities and

to be able to differentiate between the various types of reports

(standard, ad hoc and custom) and to determine whether the

organization will incur additional costs as a result of any

custom reports. Prior to implementation, discussing reporting

options and capabilities with the organization’s DMS

vendor will help ensure the necessary reports will be

available at go-live.

When evaluating reporting, the following should be considered:

» It may be necessary to compare the new DMS system to a

previous DMS system to understand which reports should be

retained and which are no longer needed.

» How are reports generated? Can they be produced within the

DMS application, or are they produced external to the

application?

» If reports are generated external to the application, what

platform is used to generate reports? Is extra software or

hardware needed?

» What kind of reports can be produced? Is an internal report

writer needed?

» How often will reports be generated, and can they be auto-

matically scheduled?

» It is important to predefine “pages” versus “images” when

evaluating the report data. While one person may think that

a page consists of only one side, another may consider a page

as two sides. Often, “images” is used where one image equals

one side of the page.

Reporting is usually accomplished through the routine

reporting of information in status reports to key individuals

and groups. The following reports should be evaluated as the

organization implements DMS routine reporting:

Quality Reports: To measure quality output within all

functions according to the organization’s needs

» Breakdown by problem categories (such as mixed accounts,

mixed document, or poor image quality)

» Breakdown by error severity

» Breakdown by patient/service type

» Missing primary documents

» Overall quality with drill-down ability to the document

imaging specialist (employee) for each step of the process

Productivity Reports: To measure productivity in all

functions according to the organization’s needs

» Turnaround time (TAT)

- High level (entire TAT for all functions including prep, scan,

Updated 2012

AHIMA | 13

index, and QC)

- Specific charts or specific document type (such as loose) to

track increase or decrease in certain areas relating to EHR

implementation

- Each stage of the scan process (prep, scan, index, and QC)

- All with drill-down ability to measure the individual

document imaging specialist (employee)

- Criteria could include the following: User ID, total pages,

total documents, pages per hour, documents per hour,

average pages per batch and total hours spent performing

the task. Reports can be generated for scanning as well as

for indexing.

» Patient/service type

Operations: To assist in managing the day-to-day operations

of document imaging

» Managing discharge list

» Courier tracking

» Quality feedback

» Chart tracking

» Change request

» Destruction notification

Research: Reports to assist in finding a specific chart in the

scanning process

» By account number

» By medical record number

» By scan batch

» By box

Reporting from DMS document capture system: Reports that

may be available specifically from the scanning

application (usually separate from the DMS)

» Scanning productivity results

» Index productivity results

» TAT of each system

Staffing During Transition

For most organizations, the EHR transition will happen in

phases. The impact on staffing and operations must be consid-

ered, and skill sets need to be assessed throughout the process

to ensure the transition is successful.

Staffing concerns for document imaging can be different from

other HIM roles. All job descriptions will need to be reviewed

and revised to reflect new skill set(s). Like all HIM professionals,

the ideal candidate should be able to maintain accuracy, focus

on attention to detail, and uphold confidentiality, but an imag-

ing specialist also needs to be able to adapt to a production-

based environment, which requires an increased ability to

remain astutely focused, work independently, and not be easily

distracted. When recruiting for document imaging specialists,

reference appendices D, E, F, and G to identify appropriate skill

set and job description criteria in the following areas: Prepping,

scanning, indexing, review, and quality control.

Skill sets should be time-tested during the interview process to

evaluate how the candidate would perform in a high-production

environment. The ability to remain focused amid high levels of

activity and noise distractions is critical to the success of

the process.

Cross training is recommended for ensuring continuity of

operations in the event of a short-staffing circumstance as

well as for discovering whether others possess special talent or

interest in certain aspects of the operation. For information on

one organization’s experience with a DMS implementation in

a multi-facility environment, please refer to the attached case

interview, “The EHR’s Impact on Staffing and Turnaround

Times: Centralizing the HIM Department in a Multi-Facility

Environment.”

In addition, figure 1.3 is a scenario showing how to calculate

the number of staff needed. The scenario assumes the depart-

ment is capturing 3,500,000 images per year. The calculation is

(images per year)/(images per hour) × 2080 to get the number

of full-time equivalents (FTEs). It is very important to keep

in mind that the initial rates and images per hour (IPH) will

vary depending upon equipment and manufacturer. Before

determining these rates, consultation with the organization’s

scanning vendor is highly recommended.

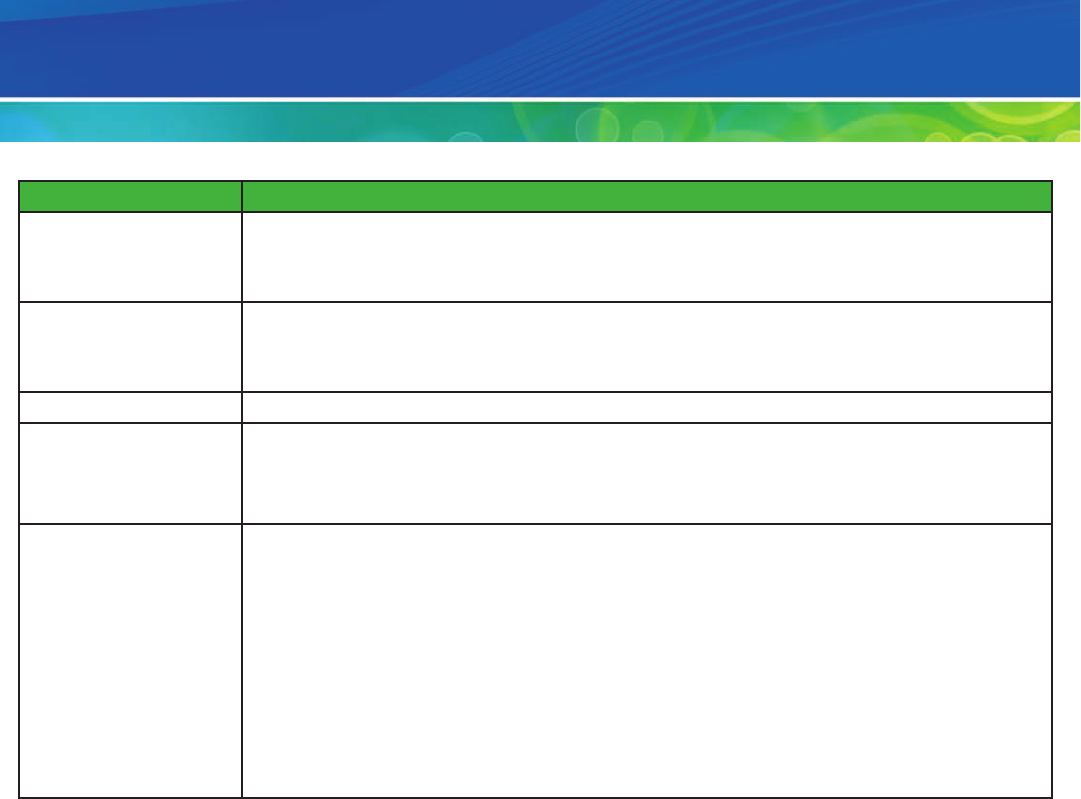

Figure 1.4 Excerpt from “Document Management and Imaging Best

Practices to Manage Hybrid Records” Preconvention Workshop, 2011

AHIMA Convention Proceedings

Document Management and Imaging Toolkit

14 | AHIMA

System Design Options

and Considerations

DMSs include tools to assist in the transition to the EHR and

enhance integration. Document retrieval, viewing, distribution

and workflow, including chart completion, are all important

components to consider when attempting to leverage current

technology to boost EHR adoption. In addition, integration is

critical to achieving seamless EHR integration.

Document Retrieval, Viewing, and Distribution

Retrieving documents will depend on how a DMS is deployed.

In some cases it could be through the organization’s intranet,

the Internet, an application on the desktop, or within the

clinical system. Ideally, access is simple and does not require

the user to jump back and forth between systems.

Methods of viewing and retrieving documents should be

provided on-site in designated work areas or throughout the

organization. Remote viewing should be provided to authorized

users in particular to support viewing of documents from

physicians’ offices, remote completion of records, and remote

coding or other job functions that may work virtually. Basic

and advanced search methods should include filters and the

appropriate security measures to track access and to limit

access on a need-to-know basis.

Distribution of information must be managed by the organiza-

tion and should include the following options:

» Online viewing only for authorized users

» Online viewing and printing (generally only provided to

HIM staff to support release of information functions)

» Automatically fax for authorized users including scheduled

distribution (for example, carbon copies of ED notes to

the referring physician, scheduled at certain day(s) and/or

time(s))

In addition, it should be noted that if a vendor hosts or retains

the images or stores the record for the organization, it is a

business associate, and the organization would need to execute

a business associate agreement (BAA) that is compliant with

the new HITECH rules.

Workflow

Workflow is a critical component of a DMS because it enables

electronic routing and concurrent processing. Many tasks

traditionally performed within the HIM department now can

be performed remotely within the healthcare facility. Workflow

rules identify how documents tied to the tasks can be assigned,

routed, activated, and managed through these rules and

directed to a staff member for disposition. For example, when

the status of dictation changes from dictate to transcribe to

sign to signed, a chart completion workflow rule will automati-

cally update the status of the deficiency system without human

intervention and simultaneously send a request for dictation or

review and signature to the physician’s inbox.

Coding is another critical HIM workflow in that it enables

records to be distributed to coders’ work queues. Coders are

then able to perform their work using the EHR instead of the

paper record. They should be able to route records to supervi-

sors for coding questions, to physicians for coding query, or

to auditors for prebill review. Coding from the imaged record

or clinical system creates new opportunities to meet bill hold

requirements, manage space, and recruit coders.

The HIM department’s workflow changes significantly with the

implementation of a DMS. In the implementation phase, HIM

departments should articulate workflow assumptions, identify

changes, and make decisions regarding which process(es) to

implement.

Chart Completion

When converting from paper to electronic records, the chart

analysis and chart completion processes change. With chart

analysis, staff analyze records online instead of using the paper

charts. One of the largest workflows in a document manage-

ment system is most often chart completion, and within

this workflow is the ability to electronically edit (annotate a

scanned image), sign, add an addendum, and flag or tag defi-

cient documents to electronically allocate a deficiency to the

appropriate provider(s).

Electronic signature capability should exist for both scanned

documents and text documents that are interfaced. Workflow

rules can direct unsigned documents (scanned notes and dic-

tated reports) to a physician’s work queue either in the EHR or

the DMS where they can be signed, edited, or an updated with

an addendum. Updating documents and securing signatures

electronically automates the record completion process with

little human intervention.

Where in the workflow electronic signatures are captured

and where finalized documents will reside is a fundamental

decision that needs to be made when implementing the DMS

and transitioning to the EHR. For example, if the majority of

the facility’s documentation resides in the EHR with a robust

workflow, the organization may decide to capture and index

documents in the DMS with an upload into the EHR, where

that workflow is used to complete the record. However, on the

other hand, if the majority of the documentation is interfaced

and completed in the DMS, the organization may decide to

use the DMS to capture, index, complete, and store the health

record. For more information on the legal archive, see “Using

Document Management as the Legal Archive.”

Updated 2012

AHIMA | 15

As with all functions, policies, and procedures related to the

DMS will provide consistent guidance to all employees within

the organization. Policies and procedures should be reviewed

to ensure consistency with laws and guidelines established by

federal, state, regulatory, and accreditation (if applicable)

agencies. Administrative leadership, HIM, information

technology, information security, quality assurance, and

clinical staff should be included in the process of developing

enterprise DMS policies and procedures. The HIM department

will need to develop policies and procedures specific to the

document management system. The following are areas where

specific policy and procedures unique to DMS will need special

attention and guidance:

» Corrections: Policies and procedures should identify how

and by whom correction can be made. Business rules may

determine who can access and correct unsigned documents.

Organizations should develop guidelines for changes made to

signed and unsigned documents.

For example, if a document is changed or corrected, typically the

copy with the error is removed from view within the DMS.

However, a copy of the original document must be available

particularly if it was viewable and relied on by clinicians. It

is important that all staff are aware that these documents are

available if needed. Workflow should be evaluated for ensur-

ing corrected documents are redirected to the source of where

the initial incorrect document was created or received.

•Retraction, reassignment, resequencing: These terms have

different meanings and their corresponding action may differ.

Therefore, it is best to define these terms.

- Retraction A retraction is the action of correcting information

that was incorrect, invalid or made in error, and preventing its

display or hiding the entry or documentation from further

general views. However, the original information is available

in the previous version. An annotation should be viewable

to the clinical staff so that the retracted document can be

consulted if needed.

- Resequencing involves moving a document from one location

to another within the same episode of care, (e.g. a progress

note that was linked to the wrong date). No annotation of

this action is necessary.

- Reassignment (synonymous with misfiles) The process of

moving one or more documents from one episode of care to

another episode of care within the same patient record, (e.g.

the history and physical posted to the incorrect episode). An

annotation should be viewable to the clinical staff so that

the reassigned document can be consulted if needed.

3

Integration

Organizations have discovered that a DMS is a critical compo-

nent when transitioning to the EHR. DMS allows providers of

all sizes to move to an electronic record with minimal impact

on clinical areas. As federal regulations such as The Health

Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health

Act (HITECH) push for digitized information, document

management and imaging can be a stepping stone or used in

conjunction with the best-of-breed systems that create an EHR.

For this reason, integration points are recommended in any

Request for Information (RFI) or Request for Proposal (RFP)

issued related to acquisition of DMS technology.

There are important technical considerations when evaluating

integration points between the DMS and the EHR. Refer to the

table in Appendix H, “Document Imaging and EHR Points of

Integration,” for high-level considerations that organizations

can use to coordinate an implementation plan or an ongoing

maintenance plan for DMS and EHR system configurations.

Implementation and Leadership

Regardless of the industry’s progress on the path to the EHR,

most healthcare organizations continue to utilize paper-based

health information. Doing so results in a hybrid health record

that is partially computer-generated and partially paper-based.

The goal of a DMS is not only to manage paper, but also to

manage all of the organization’s documents (computer-gener-

ated and paper-based).

The following are best practices detailing the key steps in

implementing a DMS.

Determining the Information Technology Strategy

AHIMA recommends that HIM computer systems comple-

ment the organization’s EHR and clinical decision support

systems that are acquired and installed in the healthcare orga-

nization. For this reason, asking questions about integration is

critical to the strategy discussion.

Clinical Systems

Clinical health information systems are used by care providers

to document the care provided to patients (such as computer-

ized physician order entry [CPOE] systems and clinical docu-

mentation systems). HIM professionals typically focus on how

to automate the familiar chart components, such as physician

progress notes, nurses’ notes, graphics, and ancillary notes.

In the past, clinical health information systems were created by

clinicians for clinicians with little thought about their impact

on HIM and other healthcare organization processes that work

in the background to support caregivers, such as the creation

Document Management and Imaging Toolkit

16 | AHIMA

and maintenance of the legal record and revenue collection.

Today’s newer generation systems include these supporting

process requirements. For example, many of these systems

include the document imaging technology component of a

DMS because supporting the process requirement of scanning

paper-based documents remains useful until all physician,

nursing, and ancillary documentation is captured in a digital

format at every healthcare organization.

Scanning Implementation Options

Scanning is one type of technology that can be used in a DMS.

It can be implemented as a stand-alone departmental solution

or one that integrates with existing clinical applications. Often

stand-alone solutions are installed in one or two departments

such as HIM or billing, solving problems inherent in the access,

movement, and storage of paper documents.

However, stand-alone scanning systems require implementers

to consider how they will interact with clinical systems. These

systems often stand on their own, with little connection with

other systems except to receive data through interfaces. If an

HIM department chooses this option, access to authorized

users outside of HIM should be provided in a manner that

does not require users to leave the clinical system to view

information in the DMS.

Several clinical vendors now include scanning as a component

of their clinical health information systems, thereby achieving

greater integration with clinical applications than their stand-

alone counterparts. It is becoming more common for clinical

vendors to include the breadth of required HIM functionality,

including scanning as a critical component.

The decision to purchase a scanning component as a stand-

alone system or to purchase it as part of a clinical system

should be based on where an organization is on the path to the

EHR. It should also be based on the functionality provided by

clinical vendors versus stand-alone scanning vendors.

If an organization decides to outsource its scanning to a docu-

ment management vendor, technology choices and the integra-

tion with the EHR are very important to the overall success of

the effort.

Planning Steps/Checklist: Once it is determined that the

document management implementation is moving forward,

the detailed planning steps must begin. To ensure a full return

on investment, it is important to complete each step with ad-

equate time for planning.

In addition, remember to include the appropriate stakeholders

(users, influencers, key decision makers, and such) in the plan-

ning process. Also include key players on the EHR task force,

and create a list of others who need to make a decision in the

planning component.

There are 11 key steps in the planning process:

1. Assembly: Ensure the record is in optimal physical order

for efficient processing for records to be scanned.

2. Types of records: Determine where each record type is

stored and how reconciliation (check in and account for

each chart, including outpatients’) will occur on a daily

basis

3. Forms inventory/format: Create inventory with a sample

of each form considering redesign needs.

4. Loose or late reports: Determine policy on receipt of loose

reports, adding in order or filing in back of chart, and codi-

fying once entered into system.

5. Physical layout of equipment: Determine workflow in

HIM department and consider the physical environment

for scanning equipment and staff.

6. Analysis, deficiency, and electronic signature process:

Ensure that the medical record is complete and that entries

are timely according to established rules and regulations.

7. Paper retention and destruction: Determine disposal

procedure for paper documents after scanning.

8. Communications: Ensure that all stakeholders receive

critical information about the new system and its impact.

9. Quality assurance: After documents are scanned, establish

indexing and quality control. Indexing is performed to

assign document names and encounter numbers to each

document. It is recommended that quality be performed

on 100 percent of images to review the quality of scanned

images. In addition to this initial quality control, ongoing

quality monitoring should be performed on a random basis.

10. Policy and procedures: Develop new policies and proce-

dures. Adapt existing policies to new processes related to

changes in workflow, access, storage and retention, and

such.

11. Legal considerations: The information stored is the entity’s

business record (in healthcare, the legal record). A plan to

house this information on media other than paper must be

scrutinized by legal counsel to ensure that the technology

being considered can comply with federal and state laws,

requirements for licensure, and credentialing, along with

operational needs and that it is consistent with existing

policies and procedures. There should also be a risk man-

agement component of the analysis to ensure that there

will be no compromise to patient care and that documents

required for lawsuits remain available. This latter consid-

eration may impact an organization’s decision on how to

proceed with storage and retrieval of documents already

scanned into the DMS.

Updated 2012

AHIMA | 17

The Implementation Phase

In the implementation phase, the real work begins. Establishing

a project management team, solidifying work plans and creat-

ing a management reporting methodology for the implementa-

tion will be accomplished during this phase. Workflow will be

redesigned and decisions will be made based on input from the

HIM department and the vendor’s project management team.

During the process, many workflows and schematics will be

designed and redesigned. Finally, the implementation phase

will include testing, training, and the system going live.

Project Management: A strong project management team and

plan will help ensure a smooth and successful transition to a

DMS. This section provides resources and guidance that are

typically involved in managing a DMS implementation. Please

note that this list may vary by vendor or by organization. How-

ever, it is critical that the organization receive commitments

from the vendor(s) that their implementation team members

will support the go-live timeline.

Implementation Team Roles and Responsibilities

Vendor Roles and Responsibilities

» Project manager: Manages overall project and the vendor

project team focusing on scope, time, cost, risk, and quality.

Works closely with the enterprise project manager through-

out the duration of the project.

» Application consultant: Provides expertise in configuring

the software product to meet the needs of the enterprise, in

addition to providing the enterprise with support to determine

how the product will work best within the organization.

» Programmers: Provide expertise in coding the software

product to meet the needs of the enterprise.

» Integration analysts: Provides expertise in developing inter-

faces and conversions to meet the needs of the project. In

addition, provides expertise on the database level requirements.

» System engineers: Provides expertise on replacing and

setting up the software.

Organization’s Roles and Responsibilities

» The project manager manages overall project and the en-

terprise project team focusing on scope, time, cost, risk, and

quality. The project manager works closely with the vendor

project manager throughout the duration of the project.

» The enterprise analyst is responsible for data collection,

coding and configuring tables, documenting end-user

functions, and analyzing system reports.

» Functional area managers are representatives from the de-

partments or areas that will be using the system. They

provide area-specific knowledge and are responsible for

providing input to work processes, test plans, staff training,

and policies and procedures.

» The steering committee is comprised of executive-level

representatives from various enterprise departments who

have a stake in the project. The project manager should be a

member of this committee.

» The interface analyst performs data collection, coding or

configuration, and testing for interfaces and also develops

technical specifications and test plans for interfaces.

» The network administrator evaluates and facilitates the

network level activities required by the project.

» The server administrator installs database-related software,

monitors system operations, and performs system mainte-

nance.

» The system administrator manages installation of hardware

and software required by the project.

» The desktop administrator is responsible for workstation

rollout required by the project.

» Super users provide application support to end users during

and after activation.

» Training resources (training coordinator, trainers) manage

the training process by determining training needs,

developing training plans and classes, and performing

end-user training.

Project Sponsors

Because the implementation of DMS and its components are

far-reaching in terms of organizational impact, involved and

committed sponsorship of the project is critical to successful

implementation. The sponsors of the project are the visible

champions and organizational spokespersons for the project.

The importance of their role as key communicators to the senior

leadership team and clinicians cannot be underestimated.

Project sponsorship should come from within the senior

leadership of the HIM, information technology, finance, and

clinical departments. Sponsors typically have a vested interest

in the achievement of the goals set forth in the project charter.

Because the goals of a DMS project typically range from the

tactical (such as enabling the medical record to be concurrently