CJAL * RCLA Gudmestad, Edmonds, Donaldson & Carmichael

Canadian Journal of Applied Linguistics: 23, 1 (2020): 169-191!

169

Near-Native Sociolinguistic Competence in French: Evidence from

Variable Future-Time Expression

Aarnes Gudmestad

Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University

Amanda Edmonds

Université Paul-Valéry Montpellier 3

Bryan Donaldson

University of California, Santa Cruz

Katie Carmichael

Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University

Abstract

This study aims to advance the understanding of sociolinguistic competence among near-

native speakers and to further knowledge about the acquisition of variable structures. We

conduct a quantitative analysis of variable future-time expression in informal conversations

between near-native and native speakers of French. In addition to examining linguistic

constraints that have been investigated in previous research, we build on prior work by

introducing a new factor that enables us to consider the role that formality of the variants

plays in the use of variable future-time expression. We conclude by comparing these new

findings to those for the same dataset and other variable structures (namely, negation and

interrogatives, Donaldson, 2016, 2017) and by advocating for more research that consists of

multiple, complementary analyses of the same dataset.

Résumé

Les objectifs de cette étude sont (a) d’apporter de nouvelles données relatives à la

compétence sociolinguistique parmi des locuteurs non natifs qui ont un niveau très avancé

dans leur langue étrangère et (b) de contribuer à nos connaissances sur l’acquisition des

structures variables. Nous proposons une analyse quantitative de l’expression du futur dans

des conversations informelles entre un locuteur très avancé et un locuteur natif du français.

Afin de comprendre ce cas de variation, nous faisons appel à des facteurs linguistiques qui

ont été identifiés dans des recherches précédentes, et nous proposons un nouveau facteur qui

nous permet d’étudier le rôle joué par la formalité des variantes dans l’expression du futur.

Pour conclure, nous comparons les résultats de cette analyse aux recherches précédentes qui

ont examiné d’autres structures variables dans le même corpus (notamment, la négation et

les interrogatives, Donaldson, 2016, 2017) et nous soulignons l’intérêt et l’importance de

faire de multiples analyses complémentaires d’un seul corpus.

CJAL * RCLA Gudmestad, Edmonds, Donaldson & Carmichael

Canadian Journal of Applied Linguistics: 23, 1 (2020): 169-191!

170

Near-Native Sociolinguistic Competence in French: Evidence from Variable Future-

Time Expression

In the current study we aim to further knowledge about sociolinguistic competence

among additional language users (see The Douglas Fir Group, 2016, for use of the term

additional language). Sociolinguistic competence involves the ability to vary language

according to a range of linguistic and extra-linguistic (namely, social) factors. Variationist

approaches (Labov, 1972) have been used to examine this ability, with scholars in the field

of second language acquisition (SLA) concentrating on how additional language learners

acquire and use variable structures (i.e., linguistic phenomena that are not categorical for

native speakers [NSs]; cf. Geeslin and Long, 2014). Although this research has examined

learners at different proficiency levels, resulting in observations about the developmental

trajectory with numerous variable structures, less is known about how near-native speakers

1

(NNSs) use variable structures. In the current study, we address how NNSs use variable

structures by reporting on a new empirical study of variable use of future-time expression

in French. Our primary goals are to examine the linguistic and sociostylistic constraints that

condition NNSs’ use of future-time expression in French and to compare their variable use

to that of NSs with whom the NNSs have close relationships.

2

As a secondary goal we

briefly compare our results on future-time expression to findings from previous

investigations that have examined how the same group of NNSs uses other variable

structures (Donaldson, 2016, 2017). In so doing, we argue for the importance of multiple,

complementary investigations of a single group of participants for advancing knowledge of

sociolinguistic competence.

Background

In what follows we present two areas of research that are particularly relevant for

the current study, discussing additional language variationist research before offering a

concise overview of future-time expression in French.

Additional language variation

Sociolinguistic variation occurs when two or more forms or variants are used to

convey the same function or meaning and the use of these variants is conditioned by a

range of linguistic and extra-linguistic factors.

3

Such instances of variation have been the

object of study in variationist sociolinguistics, the approach we adopt. Typically, a

quantitative paradigm, variationist sociolinguistics not only documents the frequency with

which each variant occurs, but also offers probabilistic models that identify the linguistic

and extra-linguistic factors that predict the use of a given variant. These statistical models

have enabled researchers to characterize language variation and change among NSs

(Tagliamonte, 2012) and, subsequently, among non-native speakers (Geeslin & Long,

2014).

Preston’s (2000) psycholinguistic model for interlanguage variation provides a

theoretical explanation for additional language acquisition of variation. Reflecting on how

variable structures are affected by social context, linguistic context, and time, Preston

suggests that each (sub)conscious choice among variants – such as elle va (she’s going)

CJAL * RCLA Gudmestad, Edmonds, Donaldson & Carmichael

Canadian Journal of Applied Linguistics: 23, 1 (2020): 169-191!

171

versus elle va aller (she’s going to go) versus elle ira (she will go) – is impacted by

probabilistic rankings at three different levels. Level 1 refers to extra-linguistic factors,

including, among others, gender of the learner (e.g., Mougeon, Nadasdi, & Rehner, 2010)

and interactional norms (e.g., Tarone, 2007), such as style and formality. Level 2 concerns

the linguistic factors that impact variation (e.g., adverbial specification for future-time

expression in French, Nadasdi, Mougeon, & Rehner, 2003), and Level 3 addresses time and

illustrates how the linguistic and social factors that govern variation change over time as

learners move along the developmental trajectory (e.g., Tarone & Liu, 1995). As pointed

out by Tarone (2007), the probabilistic nature of Preston’s (2000) model is consistent with

other usage-based models in SLA (see Ellis, 2012) and allows the researcher to conceive of

extra-linguistic and linguistic factors and time in a single, psycholinguistic model.

Although we examine both Level 1 and Level 2 constraints in the present

investigation, we highlight here one Level 1 issue that we aim to address, namely, the

formality or sociostylistic nature of variants, because it has received less attention than the

well-studied linguistic factors. Following Richards and Schmidt (2010), stylistic variation

refers to “differences in the speech or writing of a person or group of people according to

the situation, the topic, the addressee(s), and the location. Stylistic variation can be

observed in the use of different speech sounds, different words or expressions, or different

sentence structures” (p. 567). Mougeon et al. (2010) describe a continuum of sociostylistic

markedness for variants with five main categories: marked informal variants, mildly

marked informal variants, neutral variants, formal variants, and hyper-formal variants (p. 9-

10). In general, some of the distinguishing characteristics are that formal variants

correspond to prescriptive language rules and are common in written or careful speech,

whereas informal variants diverge from standard language rules and are typical of casual

speech. Neutral variants are similar to formal variants in that they correspond to standard

language rules but differ because they “are not sociostylistically marked … [and] stand as a

default alternative to other marked standard or non-standard variants” (p. 9-10). In their

investigation, Mougeon et al. analyzed the use of numerous variable structures by a group

of instructed, immersion learners of French in Canada and found differences in their use of

variants according to the sociostylistic value of the variant. Specifically, they observed that

immersion learners overused formal variants and underused informal ones. The learners

produced some but not all neutral variants as well (p. 109). The conclusion that instructed

learners tend to overuse formal variants when compared to NSs is supported by other

studies (Regan, Howard, & Lemée, 2009; van Compernolle, 2015), and van Compernolle

has called this aspect of sociolinguistic competence “non-native pragmatic conservatism”

(p. 60).

Less research, however, has examined the role that the formality of variants plays in

the use of variable structures by non-native speakers who are not in an instructional setting.

Thus, we aim to continue this line of inquiry by studying a near-native population living in

the target language environment. Importantly, our participant group has already been

investigated with respect to two other variable structures – interrogatives (Donaldson,

2016) and negation (Donaldson, 2017) – allowing us to consider findings from multiple

variable structures and, consequently, advance the understanding of near-native

sociolinguistic competence for this group of participants. Among other issues, both of these

studies have examined the sociostylistic value of these variable structures’ variants and

whether the NNSs’ use is targetlike. This research draws on informal conversation data

CJAL * RCLA Gudmestad, Edmonds, Donaldson & Carmichael

Canadian Journal of Applied Linguistics: 23, 1 (2020): 169-191!

172

from ten NNSs and ten NSs of Hexagonal French. Donaldson (2016) detailed the full range

of interrogative forms that NNSs and NSs used and compared their communicative

function and how they were used in sociostylistic terms. The results showed that the NNSs

converged toward NS use, both in terms of repertoire and use of formal and informal

variants. Donaldson (2017) also provided evidence of near-nativeness with variable

negation. The preverbal negative particle ne is frequently omitted in informal spoken

French. The results revealed no statistical difference between the NNSs' and NSs' rates of

ne deletion, and the NNSs were sensitive to all of the sociostylistic factors (e.g., topic

seriousness) and most of the linguistic factors (e.g., clause type) that conditioned NSs’ use.

It bears mentioning that for topic seriousness, a factor included in the present investigation

(see Data coding and analysis for further details), both participant groups increased their

retention of ne (the formal variant) in serious topics. Together, these investigations offer

evidence of near-nativeness with the variable use of two grammatical structures that form

part of sociolinguistic competence in French. Furthermore, although instructed learners

tend to exhibit pragmatic conservatism (van Compernolle, 2015) by using formal variants

at a higher rate than NSs (e.g., Mougeon et al., 2010; Regan et al., 2009), Donaldson

(2016) argued, on the basis of these results, that “this type of stylistic infelicity can be

overcome at the near-native level” (p. 496). We seek to ascertain whether this participant

group exhibits near-nativeness with another variable structure – future-time expression.

Future-time expression in French

Future-time expression refers to verb forms that express a temporal reference

posterior to the moment of speaking. The inflectional future (IF), periphrastic future (PF),

and futurate present are the forms most often included in descriptions of future-time

expression in French. The following are examples from the current dataset:

IF: … quelque chose qui terminera ce cycle-là (NNS 10)

‘… something that will finish the cycle’

PF: tu sais pas à quelle heure tu vas terminer tout? (NS 3)

‘you don’t know what time you are going to finish everything?’

Futurate present: je termine à dix heures et demie (NS 5)

‘I finish at 10:30’

Future-time expression in French constitutes an example of morphosyntactic

variation conditioned by various linguistic and extra-linguistic factors (Poplack & Turpin,

1999). In this section we offer a brief overview of sociolinguistic research on future-time

expression in French among NSs, followed by a discussion of studies on non-native

speakers.

NS sociolinguistic research. Sociolinguistic research on future-time expression in

French has centered on Canadian varieties (e.g., Comeau, 2011; Poplack & Dion, 2009;

Wagner & Sankoff, 2011) and to a lesser extent Hexagonal (i.e., French in mainland

France; e.g., Gudmestad, Edmonds, Donaldson, & Carmichael, 2018; Roberts, 2012;

Villeneuve & Comeau, 2016) and Martinican (Roberts, 2016) varieties. We highlight the

independent variables that have been studied in previous research and then focus on the

CJAL * RCLA Gudmestad, Edmonds, Donaldson & Carmichael

Canadian Journal of Applied Linguistics: 23, 1 (2020): 169-191!

173

evidence of the importance of formality in the use of this variable. We conclude the section

with a detailed presentation of the research examining Hexagonal French, the variety

represented in our data.

Numerous factors have been examined in variationist studies on future-time

expression in different varieties of French. Extra-linguistic factors include education level,

age, and gender, and well-studied linguistic factors include temporal distance,

(un)certainty, adverbial specification, sentential polarity, and grammatical person. These

various linguistic factors have been taken both from descriptions of future-time expression

in grammars and from the literature on future-time expression (see Poplack & Dion, 2009).

Temporal distance refers to the distance between the time of speaking and future-time

event. (Un)certainty deals with how certain the speaker is that the future-event will occur.

Adverbial specification identifies whether temporal adverbials accompany future-time

verbs. Sentential polarity distinguishes negated from affirmative sentences, and

grammatical person reflects the person and number of the subject. We continue the

exploration of many of these factors in the current study.

Concerning the construct of sociostylistic variation and formality, two empirical

observations have provided evidence that IF is the formal variant in variable future-time

expression. First, by investigating the linguistic factor of grammatical person of the subject,

research has shown a connection between the IF and the formal second-person pronoun

vous (e.g., Poplack & Turpin, 1999, for Canadian French, and Roberts, 2012, for

Hexagonal French). Second, Blondeau and Labeau (2016) analyzed formal, prepared

language used in oral televised weather forecasts and found that both French and

Québécois weathercasters used the IF more often than the PF, a finding that contrasts with

results from examinations of interview data for these varieties, in which the PF was the

most frequent form. This difference across genres suggests an extra-linguistic,

sociostylistic distinction between the PF and IF, with the IF being the formal variant.

Whereas the IF has been associated with formality, the futurate present and the PF have

been categorized as neutral variants (e.g., Mougeon et al., 2010).

To conclude our discussion of future-time expression in NS French, we present two

variationist studies on future-time expression in Hexagonal French.

4

Roberts (2012)

examined oral interviews collected in the 1980s in the north and south of France. He found

that, as a group, these NSs used the PF more often than the IF and that sentential polarity

was the sole predictive factor. These NSs favoured the PF in affirmative contexts and the

IF in negative contexts. Villeneuve and Comeau (2016) investigated NSs from Vimeu, in

northern France. Their analysis of interview data indicated that, like in Roberts (2012),

participants used the PF more frequently than the IF. The factors predicting use, however,

differed from Roberts’ study. The linguistic factor that conditioned future-time expression

was temporal distance, where proximal contexts favoured the PF and distal contexts

favoured the IF. Education level was the only social factor that impacted use. Participants

without a high school diploma favoured the PF, whereas those who had completed high

school favoured the IF. The differences in results between these two studies not only

demonstrate that additional research is needed in order to better understand variable future-

time expression among NSs of Hexagonal French but also underscore the need, in

additional language research, to identify a NS comparative group that is appropriate for the

additional language speakers under investigation.

CJAL * RCLA Gudmestad, Edmonds, Donaldson & Carmichael

Canadian Journal of Applied Linguistics: 23, 1 (2020): 169-191!

174

SLA research. Turning to SLA research, analyses of future-time expression in

French come from several types of data (e.g., interviews, written contextualized tasks) and

participant groups, though previous studies have generally focused on instructed learners in

various learning contexts (e.g., Ayoun, 2014; Howard, 2012a; Moses, 2002). Four insights

emerge from this body of work.

5

First, with regard to frequency of use of verb forms in

future-time contexts, classroom learners use the IF at higher rates than the PF (e.g.,

Howard, 2012a, 2012b; Moses, 2002), possibly because of the tendency to overuse formal

variants. Immersion experiences, however, lead to lower rates of the formal variant and

higher rates of the neutral variant PF (e.g., Howard, 2012b; Mougeon et al., 2010, see

Regan et al., 2009, for an exception). Second, several previous investigations have

examined many of the same linguistic factors that have been shown to predict NS use and

found differing results across studies (Blondeau, Dion, & Ziliak Michel, 2014; Edmonds &

Gudmestad, 2015; Gudmestad & Edmonds, 2016; Howard, 2012b, Mougeon et al., 2010;

Nadasdi et al., 2003; Regan et al., 2009). For instance, concerning adverbial specification,

the presence of a temporal adverbial favoured the occurrence of the futurate present among

Canadian immersion students (Mougeon et al., 2010; Nadasdi et al., 2003), Irish study-

abroad learners (Regan et al., 2009), adult Anglo-Montrealers (Blondeau et al., 2014),

Level 3 study-abroad learners (Edmonds & Gudmestad, 2015), and study-abroad learners

with high proficiency (Gudmestad & Edmonds, 2016). However, this effect was not found

for all study-abroad and foreign-language classroom learners reported on by Edmonds and

Gudmestad (2015) and Gudmestad and Edmonds (2016). Third, with the exception of

Anglo-Montrealers (Blondeau et al., 2014), no study has shown evidence of learners

becoming fully targetlike with future-time expression. Finally, two investigations have

addressed sociostylistic variation, specifically pertaining to formality. Neither immersion

learners (Nadasdi et al., 2003), nor university learners who had spent an academic year in

France (Regan et al., 2009) favoured the use of the IF with the subject pronoun vous, as has

been reported for certain groups of NSs. Regan et al. (2009) did, however, find that style

formality constrained use. The researchers differentiated between formal and informal style

based on the interview topic and found that the participants favoured the IF with formal

topics and the PF and futurate present with informal topics. This observation suggests that

non-native speakers can develop sensitivity to sociostylistic constraints of variable future-

time expression in French. We aim to build on this existing research by investigating how

another participant population – NNSs – uses variable future-time expression.

The Current Study

Our two research questions are formulated with the objectives of contributing new

knowledge on variable future-time expression among NNSs:

1. With what frequency do NNSs of Hexagonal French use the IF, PF, and present

indicative (PI) to express future-time expression in informal, unstructured

conversation?

2. Which linguistic and sociostylistic factors predict NNSs’ use of the IF, PF and PI

in informal, unstructured conversation?

CJAL * RCLA Gudmestad, Edmonds, Donaldson & Carmichael

Canadian Journal of Applied Linguistics: 23, 1 (2020): 169-191!

175

Method

Dataset and participants

This dataset consists of 10 unguided conversations between a NNS and a NS of

French. The conversations, which lasted between 45 and 58 minutes, were recorded in an

informal setting without the presence of a researcher. The participants spoke about any

topic(s) of their choosing. The conversation partners knew each other well (e.g., spouses,

friends), which aided in eliciting informal speech (cf. Donaldson, 2017). The data were

collected mostly in southwest France, though one conversation was collected in Paris. We

argue that this NS group is particularly well-suited as a comparison group because the

NNSs have close relationships with the NSs. The dataset consists of 77,300 words

(excluding non-lexical backchannels, hesitations, etc.) and is balanced quantitatively

between NS and NNS production (5,300 and 5,600 finite clauses, respectively). Donaldson

(2016, 2017, inter alia) demonstrates that that there is no evidence that either participant

group is accommodating to the other.

The ten NNSs, whose first language was English, ranged in age from 26 to 70 years

(M = 44.2). Eight were women and two were men. All were university educated. They

began studying French between the age of 10 and 21 years (M = 13) and had been living in

France for an average of 18 years and seven months (range in years;months: 4;3–47;3).

6

All

NNSs interacted daily with NSs. The ten NSs of Hexagonal French ranged in age from 31

to 65 years (M = 49.5). Seven were women and three were men.

7

All had earned the French

baccalauréat (roughly equivalent to a secondary school diploma), and nine of the ten were

university educated. They were dominant in French but had varying degrees of experience

with other additional languages. In general, the NSs were close in age and education level

to their NNS interlocutor. Each participant completed a replication of Birdsong’s (1992)

grammaticality judgment task, which was used to assess near-nativeness. The results

revealed that the NNSs had achieved near-native grammatical knowledge of French. While

further refinements to measuring near-nativeness are necessary, we note that prior

investigations on these participants have shown them to have nativelike behaviour on a

range of linguistic phenomena (Donaldson, 2016, 2017, inter alia).

All datasets present strengths and limitations. One advantage of this dataset is that it

allows us to contribute knowledge about near-native sociolinguistic competence (cf.

Geeslin & Long, 2014). It also enables us to extend additional language variationist

research on future-time expression to another type of data – informal conversations.

Finally, we feel confident that the sample is representative of the speakers' informal spoken

French, because their interlocutor is someone they know well. However, given the

restricted number of total speakers and the design of the corpus, certain extralinguistic

characteristics, including speaker age, gender, and regional provenance,

!cannot be

investigated. Although these factors may merit additional attention, existing research on

Hexagonal French has found neither age nor gender to be conditioning factors for future-

time expression (Roberts, 2012; Villeneuve & Comeau, 2016). With respect to potential

regional variation, only Villeneuve and Comeau have conducted an analysis of future-time

expression in France that has focused on a single regional variety. Whereas it remains to be

seen whether their findings hold for Hexagonal French more generally, we note that

extensive work by Armstrong and Pooley (2010) shows evidence of leveling of regional

CJAL * RCLA Gudmestad, Edmonds, Donaldson & Carmichael

Canadian Journal of Applied Linguistics: 23, 1 (2020): 169-191!

176

differences in Hexagonal French. Finally, we recognize that time spent abroad may impact

use for the NNSs. We leave these issues to future research.

Data coding and analysis

After the third author and a NS of French had transcribed the conversations, we

coded the transcripts for future-time contexts. We operationalized a future-time context as

any conjugated verb with a temporal reference subsequent to the moment of speaking (cf.

Blondeau et al., 2014). We used contextual information, such as shared knowledge, subject

matter, and temporal expressions to establish futurity. This definition means that the

presence of the PF or IF did not necessarily constitute a future-time context because these

forms can express other functions (e.g., PF can be used to talk about habitual actions not

set to occur in the future, Poplack & Turpin, 1999). To establish reliability in the coding,

two authors coded every transcript independently and then compared their coding. Any

disagreements were resolved with the help of a third author.

After identifying future-time contexts, we coded each case for the dependent

variable and five independent variables. The verb form used in a future-time context was

the dependent variable. We focused on three of the most frequent forms identified in

Edmonds, Gudmestad, and Donaldson (2017): PF, PI, and IF. The IF warranted special

coding considerations because of homophony in the verb system in Hexagonal French.

First, the first-person singular forms of the conditional (je verrais [I would see]) and the IF

(je verrai [I will see]) tend to be homophonous in informal Hexagonal speech. These forms

maintain a spelling difference in the final morpheme, which reflects the fact that in the past

there was a phonetic difference. Although the phonetic distinction can still occur in

contemporary formal speech (e.g., Armstrong & Pooley, 2010; Hansen, 2016), this present-

day homophony in informal speech means that we could not empirically distinguish first-

person singular IF and conditional forms in our oral data. The analysis of the IF thus

excludes first-person singular forms. Another coding decision pertained to present-tense

forms that conveyed futurity. In French most present forms do not contain overt

morphology that signifies its verbal mood. In other words, although some forms have

morphology that marks them as an indicative or subjunctive form (e.g., tu viens

INDIC

versus

tu viennes

SUBJC

[you come]), most present forms are homophonous in the indicative and

subjunctive (e.g., j’étudie [I study] in both moods). In addition to this homophony, there is

also evidence of variation in the use of verbal moods in subordinate clauses (e.g.,

Gudmestad & Edmonds, 2015; Poplack, Lealess, & Dion, 2013). Because of these two

characteristics of present forms, which result in some ambiguity in the mood of many

present forms, we distinguished among three forms in dependent clauses: PI, present

subjunctive, and present ambiguous. Given that there is no evidence of mood variation in

independent clauses, we differentiated between two forms: PI and present ambiguous.

Thus, in the current study, our analysis includes PI forms only, whereas in previous

research, it appears that the futurate present also consisted of present ambiguous forms (see

Gudmestad et al., 2018, for a more detailed discussion of coding decisions).

In terms of independent variables, we investigated two levels of the

psycholinguistic model for interlanguage variation (Preston, 2000), namely Level 2 (four

linguistic factors) and Level 1 (one sociostylistic factor). Because we are examining NNSs

at one point in time, we do not consider Level 3 (time) of the model. The independent

CJAL * RCLA Gudmestad, Edmonds, Donaldson & Carmichael

Canadian Journal of Applied Linguistics: 23, 1 (2020): 169-191!

177

linguistic factors were sentential polarity, (un)certainty, temporal distance, and lexical

temporal indicator (LTI).

8

For sentential polarity, we coded for the presence or absence of a

verbal negator (negative and positive sentences, respectively). (Un)certainty reflected

whether the future-time context was accompanied by an overt expression of (un)certainty

in the same clause as the verb or the immediately previous clause. The categories were: the

presence of a certainty marker (e.g., certainement [certainly]), the presence of an

uncertainty marker (e.g., je sais pas [I don’t know]), and the absence of a marker.

9

With

temporal distance we identified the distance between the future event and the moment of

speaking. The five categories were: greater than one month, less than one month, less than

one week, today, and ambiguous. The final linguistic factor, LTI, investigated temporal

markers signifying futurity that occurred in the same clause as its corresponding verb

form.

10

This variable consisted of three categories: the presence of a time-non-specific LTI

(e.g., plus tard [later]), the presence of a time-specific LTI (e.g., aujourd’hui [today]), and

the absence of a LTI.

11

The sociostylistic factor was topic seriousness. Although this

variable has not, to our knowledge, been investigated with respect to future-time expression

in French, we examined it because we felt that it was the most appropriate way to explore

formality in the current dataset. This issue has most often been investigated in future-time-

reference research with respect to the verb form favoured with the formal vous, but this

pronoun is rare in our dataset. We considered the concept of style, as operationalized by

Regan et al. (2009) but chose instead the concept of topic seriousness, which was explored

in Donaldson’s (2017) study of negation in these data. This decision has the important

advantage of allowing us to compare findings for the same factor across studies involving

the same participant group. More specifically, serious topics (within an otherwise informal

register) have been linked with greater use of the formal variant of variable negation in

French (e.g., Sankoff & Vincent, 1977), a finding that was also borne out in Donaldson

(2017). Such (usually temporary) stylistic shifts within the context of a given register are

labeled “micro-style variation” by Armstrong (2002, p. 171). As the IF has been described

as a formal future-time verb form (e.g., Mougeon et al., 2010), topic seriousness may

influence its use. Following previous literature (e.g., Fonseca-Greber, 2007; Poplack & St-

Amand, 2007), we coded as serious topics discussions of religion, sermons, moralizing,

education, the discipline of children, meetings, one’s profession, and the legal system. All

other topics were coded as non-serious. A final extra-linguistic factor was participant

group; we conducted separate analyses for the NNSs and NSs.

We began the analysis with a cross-tabulation to determine the frequency of use of

the PF, PI, and IF in future-time contexts. Next, using the statistical software R, we

generated a multinomial logistic regression to identify the independent linguistic variables

that conditioned the use of the verb forms under investigation.

12

This regression analyzes

the PF, PI, and IF in a single model, and, to our knowledge, the current study is the first to

apply this type of statistical analysis to production data for variable future-time expression

in additional language French. It compares one variant of the dependent variable (the

reference point) with the other two variants separately. In the current study the IF is the

reference point and this form is compared to the PF and the PI. We generated separate

multinomial regression models for the NS and NNS data, testing predictors for three future-

time expression forms: IF, PF, and PI. The best model of the data was selected through a

"step-up" procedure in R in which predictors were added to a bare model one at a time.

Then a model comparison was completed through an ANOVA, resulting in the final model

CJAL * RCLA Gudmestad, Edmonds, Donaldson & Carmichael

Canadian Journal of Applied Linguistics: 23, 1 (2020): 169-191!

178

that includes only the predictors that significantly improved the model's ability to predict

the variation observed. The predictors reveal the linguistic and sociostylistic constraints on

the use of the future-time verb forms under investigation and the ways in which they

impact use (i.e., the direction of the effects). To make assessments about targetlike use, we

compare the NS and NNS groups’ frequency of use of the three verb forms and the factors

that condition this use.

Results

The NNSs produced 345 future-time contexts and the NSs produced 308 future-

time contexts. We begin with the frequency of use of the three verb forms under

investigation (Table 1). Descriptively, the largest difference between the two participant

groups is with the IF. The NSs used the IF more frequently than the NNSs (23.1% versus

14.5%, respectively). As concerns the hierarchy of use, the NNSs used the PF most often,

followed by the PI, and, lastly, the IF. The NSs paralleled this use somewhat, though their

use was not dramatically different between the PI and IF.

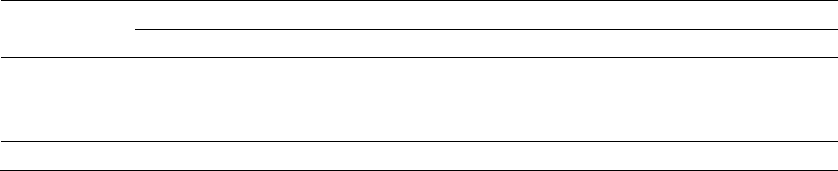

Table 1

Frequency of verb forms

NNSs

NSs

Verb form

#

%

#

%

PF

200

58.0

159

51.6

PI

95

27.5

78

25.3

IF

50

14.5

71

23.1

Total

345

100

308

100

For the second phase of the analysis, we generated a multinomial regression for

each participant group to identify the linguistic and sociostylistic factors that influenced use

of the PF, IF, and PI in future-time contexts. As previously mentioned, this statistical test

compares a reference point of the dependent variable (IF) against the other two forms

independently (PF and PI). Just as with the dependent variable, the test considers a

reference point of an independent variable against the other categories of that variable. The

reference points in the current study are the categories of today (temporal distance), none

(LTI), absence of a negator (polarity), and non-serious (seriousness of topic). For example,

for LTI, instances of future-time reference with no adverbial specification (the reference

point) were compared, separately, to cases where a time-specific LTI was present and to

cases involving a time-non-specific LTI. Although we began the analysis with the inclusion

of a fourth linguistic factor, (un)certainty, we were not able to include this variable in the

regression model due to the low occurrence of (un)certainty markers.

13

The details of the

regression models are available in Tables 2, 3, 4, and 5. In these tables a negative

coefficient means that the likelihood of using the PI or the PF is lower than the IF with a

given factor. Similarly, a positive coefficient means that the likelihood of using the PI or

PF is higher than the IF with a given factor. The p value shows whether the presence of that

predictor significantly predicts the future-time verb form (values less than < 0.05 are

statistically significant).

CJAL * RCLA Gudmestad, Edmonds, Donaldson & Carmichael

Canadian Journal of Applied Linguistics: 23, 1 (2020): 169-191!

179

Tables 2 and 3 illustrate the results of a single multinomial regression model for the

NNSs. The NNS model demonstrates that LTI and topic seriousness, but not temporal

distance or polarity, predicted verb-form use in future-time contexts (see the Appendix for

the distribution of the verb forms according to temporal distance and polarity). Regarding

LTI, the NNSs were more likely to use the PI than the IF in the presence of a time-specific

LTI compared to the absence of a LTI. No significant effects for LTI were observed for the

PF-IF comparison. Moreover, the NNSs were less likely to use the PI and PF compared to

the IF when the discourse topic was serious. In other words, serious topics significantly

predicted the use of the IF.

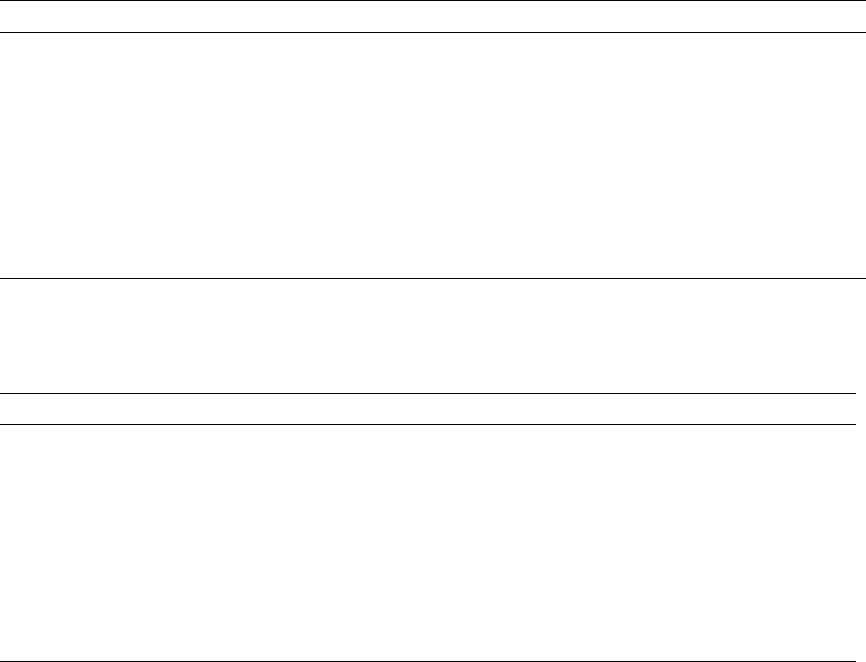

Table 2

Multinomial regression model for NNSs: PF vs IF

Factor

Coefficient

Standard error

p value

LTI

(reference point: none)

time-non-specific

-0.3514

0.5161

0.4959

time-specific

0.2762

0.5331

0.6044

SERIOUS

(reference point: non-serious)

yes

-1.0668

0.3853

0.0056

Note. Significant effects are in bold.

Table 3

Multinomial Regression Model for NNSs: PI vs IF

Factor

Coefficient

Standard error

p value

LTI

(reference point: none)

time-non-specific

-0.1344

0.6108

0.8258

time-specific

1.8074

0.5437

0.0009

SERIOUS

(reference point: non-serious)

yes

-2.1395

0.5828

0.0002

Note. Significant effects are in bold.

Turning to the NSs, the regression model revealed that all four factors worked

together to predict the use of the PF, IF, and PI in future-time contexts. The PF-IF

comparison (Table 4) shows that these NSs were less likely to use the PF than the IF when

an event was less than a week away compared to today. There was no significant difference

between these forms and the other categories of temporal distance. The NSs also exhibited

lower odds of using the PF over the IF when a time-non-specific LTI was present

compared to absent, but there was no significant difference with time-specific LTIs. In

terms of polarity, they were less likely to use the PF than the IF when a verbal negator was

CJAL * RCLA Gudmestad, Edmonds, Donaldson & Carmichael

Canadian Journal of Applied Linguistics: 23, 1 (2020): 169-191!

180

present (i.e., negative). There was no significant difference between the IF and PF with

regard to seriousness of topic. Concerning the PI-IF comparison (Table 5), these NSs

showed higher odds of using the PI versus the IF when a time-specific LTI was present

compared to absent. There was no significant difference between time-non-specific LTIs

and the absence of a LTI. For topic seriousness, they were less likely to use the PI

compared to the IF when the topic was serious. The model did not reveal significant

differences between these two verb forms with regard to temporal distance or polarity.

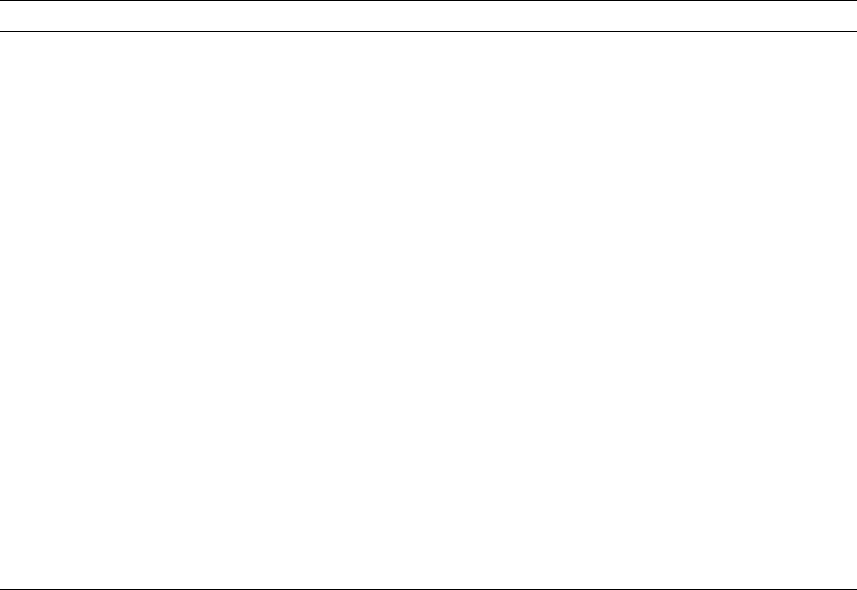

Table 4

Multinomial regression model for NSs: PF vs IF

Factor

Coefficient

Standard error

p value

TEMPORAL DISTANCE

(reference point: today)

less than a week

-1.3543

0.6716

0.0438

less than a month

-0.9975

0.8440

0.2373

greater than a month

-0.0789

0.6735

0.9068

ambiguous

-0.1950

0.6117

0.9068

LTI

(reference point: none)

time-non-specific

-1.8254

0.6486

0.0049

time-specific

0.0876

0.4767

0.8541

POLARITY

(reference point: positive)

negative

-0.8681

0.4042

0.0317

SERIOUS

(reference point: non-serious)

yes

-0.5487

0.4224

0.1940

Note. Significant effects are in bold.

! !

CJAL * RCLA Gudmestad, Edmonds, Donaldson & Carmichael

Canadian Journal of Applied Linguistics: 23, 1 (2020): 169-191!

181

Table 5

Multinomial Regression Model for NSs: PI vs IF

Factor

Coefficient

Standard error

p value

TEMPORAL DISTANCE

(reference point: today)

less than a week

-0.6664

0.7604

0.3808

less than a month

0.4262

0.8664

0.6228

greater than a month

-0.4832

0.8020

0.5468

ambiguous

-0.3408

0.7297

0.6405

LTI

(reference point: none)

time-non-specific

0.1658

0.5662

0.7697

time-specific

1.7871

0.4854

0.0002

POLARITY

(reference point: positive)

negative

-1.0143

0.5813

0.0810

SERIOUS

(reference point: non-serious)

yes

-2.7227

1.1025

0.0135

Note. Significant effects are in bold.

When we compare the linguistic factors in the NNS and NS models, we see that

temporal distance and polarity were influential factors for the NSs, but these factors were

not significant for the NNSs. However, LTI was a significant constraint for both groups.

Although the NNSs did not exhibit the targetlike significant effect for time-non-specific

LTIs in the PF-IF comparison, they were similar to the NSs with the time-specific LTIs and

PI-IF comparison. In terms of the sociostylistic factor of topic seriousness, the NSs were

more likely to use the IF than the PI with serious topics but showed no differences with this

factor for the PF-IF comparison. For the NNSs, however, this effect was significant for the

PI-IF and PF-IF comparisons. Thus, they were nativelike insofar as serious topics

significantly predicted the use of the IF compared to the PI, although their sensitivity to

seriousness was stronger than that of the NSs, as it also constrained the PF-IF comparison.

In general, this analysis revealed a similarity in the hierarchy of verb-form frequency and

differences in the contexts of use of these forms, which appear to demonstrate that this

group of NNSs is not entirely nativelike in their use of the IF, PF, and PI in contexts of

future-time expression.

Discussion

In what follows, we offer answers to the research questions based on the present

investigation’s findings. We also briefly compare the results on future-time expression to

CJAL * RCLA Gudmestad, Edmonds, Donaldson & Carmichael

Canadian Journal of Applied Linguistics: 23, 1 (2020): 169-191!

182

those on interrogatives and negation (Donaldson, 2016, 2017) in order to better understand

the use of variable structures by the same group of NNSs. Then, we turn to a discussion of

the current study’s overarching contributions. Specifically, we elaborate on the

implications of multiple, complementary investigations of a single dataset for advancing

knowledge of SLA in general and sociolinguistic competence in particular.

Main findings

The first research question concerned the NNSs’ frequency of use of the PF, PI, and

IF in future-time contexts and how these rates of use compared to those of the NS

interlocutors. The NNSs used the PF most often, followed by the PI, and, lastly, the IF in

informal conversations. This general frequency pattern is similar to some study-abroad

learners (Howard, 2012b) and to immersion learners (Mougeon et al., 2010; Nadasdi et al.,

2003), who used the PF most often in a semi-guided interview. Furthermore, the results

demonstrated that, for the most part, the NNSs paralleled the NSs’ hierarchy of use. One

final observation concerning frequency pertains to the IF, which has been cited as the

formal verb form for future-time expression (e.g., Mougeon et al., 2010): the NNSs used

this form less often than the NSs. Whereas there is ample evidence in the literature showing

that (especially classroom) learners tend to overuse the formal variant, the pattern in the

current dataset suggests that these NNSs do not exhibit pragmatic conservatism (van

Compernolle, 2015) with future-time expression. This finding is consistent with results

found for interrogative forms and negation with the same group of participants (Donaldson,

2016, 2017) and may be related to the fact that they have many “active commitments”

(Mougeon & Rehner, 2015) to the target language and their community, meaning they are

well integrated into the community and do not consider themselves to be outsiders.

The second research question investigated which factors predicted NNSs’ use of the

IF, PF, and PI in future-time contexts and how these predictive factors compared to those

of the NSs. We found that the linguistic factor of LTI and the sociostylistic factor of topic

seriousness were included in the NNS model. The NNSs were less likely to use the IF,

versus the PI, when a time-specific LTI was present. Additionally, they were more likely to

use the IF, compared to the PF or PI, when the discourse topic was serious. These results

differ from previous variationist work on future-time expression in additional language

French among study-abroad learners in which the occurrence of future-time verb forms was

constrained by a range of linguistic factors such as temporal distance, LTI, and polarity

(Gudmestad & Edmonds, 2016; Regan et al., 2009), but they are similar to Nadasdi et al.

(2003), who found that adverbial specification (i.e., LTI) was the sole linguistic predictor

for immersion learners. Differences among these investigations in terms of data types and

French proficiency, however, make it difficult to draw conclusions about these divergent

findings. In contrast to the NNSs, the NSs exhibited significant effects for the three

independent linguistic variables included in the multinomial regression: temporal distance,

polarity, and LTI. Topic seriousness was included in the regression model but, unlike the

NNSs, a significant effect was found for the PI-IF comparison only. The NSs’ preference

for the IF compared to the PI with serious topics corroborates the claim that the IF is a

formal variant (cf. Mougeon et al., 2010; Roberts, 2012).

Considering both predictive models together, the findings indicated that, despite

having converged toward a NS target for negation and interrogatives (as discussed in

CJAL * RCLA Gudmestad, Edmonds, Donaldson & Carmichael

Canadian Journal of Applied Linguistics: 23, 1 (2020): 169-191!

183

Additional language variation), these NNSs exhibited some differences from the NS group

with variable future-time expression, insofar as two linguistic factors that significantly

influenced NS use were not included in the NNS model. Moreover, we found that the

NNSs were more constrained by topic seriousness than the NSs because this factor

conditioned their use of not only the PI-IF comparison, but also the PF-IF distinction. The

results for this factor suggest that the NNSs have made a stronger association between the

IF and formality than the NSs. Perhaps worth noting as well is that the findings for the

NNS regression model appear to indicate that these NNSs are sensitive to style and

characteristics of discourse, more so than linguistic factors – at least with regard to the

constraints under investigation. This observation stems from the results that two of the

linguistic factors under investigation (polarity and temporal distance) did not impact their

use of future-time verb forms, that LTI was significant for the PI-IF comparison only, and

that topic serious constrained use for both comparisons (i.e., all verb forms under

investigation). Whereas research has shown that stylistic variation is an acquisitional

challenge for non-native speakers (e.g., Sax, 2003), this group of NNSs is sensitive to a

subtle indicator of style – topic seriousness – in their use of variable future-time

expression.

Overarching contributions to SLA

Rich, multifaceted analyses of a single group of non-native speakers have become

more feasible, thanks in part to researchers who have made additional language corpora

publicly available, allowing for many different researchers to work on the same dataset

(e.g., Granger, 2009; MacWhinney, 2000; Mitchell, Tracy-Ventura, & McManus, 2017).

This trend stands to improve the generalizability of findings, which can be difficult to

achieve when scholars are faced with making comparisons across investigations with

diverse research designs. We agree with the need for a multifaceted approach to SLA

research and argue that it is essential for furthering the understanding of additional

languages in general and of near-native sociolinguistic competence more specifically. In

the case of the current dataset, these informal, unguided conversations have been used to

investigate multiple variable structures. We are thus able to articulate our new findings on

future-time expression with the existing research on these speakers, resulting in a more

nuanced characterization of near-native sociolinguistic competence in informal French than

would otherwise be possible. Specifically, although these NNSs’ use of interrogative forms

and negation were largely targetlike (Donaldson, 2016, 2017), they exhibited various

patterns in their use of the PF, IF, and PI in future-time contexts that differed from the

patterns of the NS group. Thus, this comparison of findings from different linguistic

phenomena and the same participant population enables us to see that these NNSs have

exhibited differing outcomes for these variable structures, and, consequently, leads to a

follow-up question: why have these NNSs converged with NSs to a larger degree with

interrogatives and negation than future-time expression? While a complete answer to this

question is beyond the scope of the current investigation, we offer a preliminary reflection

on the question of varying outcomes of variable structures that emerged from our

comparison of the current study, Donaldson (2016), and Donaldson (2017). Ultimately, our

hope is to encourage more analyses of a single participant pool that aim to contribute to the

understanding of sociolinguistic competence.

14

CJAL * RCLA Gudmestad, Edmonds, Donaldson & Carmichael

Canadian Journal of Applied Linguistics: 23, 1 (2020): 169-191!

184

We focus our reflection on differing outcomes of variable structures on the

formality of the variants. As mentioned in the Background section, sociolinguistic research

has classified different variants on the basis of their level of formality (e.g., Mougeon et al.,

2010) and variationist research has suggested that this feature plays a role in additional

language development. In particular, instructed learners tend to use formal variants at

higher rates than informal or neutral variants (e.g., Howard, 2012a; Kanwit, Geeslin, &

Fafulas, 2015; Mougeon et al., 2010), showing evidence of non-native pragmatic

conservatism (van Compernolle, 2015). Moreover, Kanwit et al. (2015), in their study of

three variable morphosyntactic structures among study-abroad learners in Mexico and

Spain, hypothesized that the level of consciousness with regard to whether variants carry

stigma or prestige among NSs likely impacts the input learners receive, which in turn could

influence acquisition. Although what is meant by “level of consciousness” remains to be

operationalized clearly, this observation seems to suggest in part that the salience of a

variant’s formality may impact additional language development (see Gass, Spinner, &

Behney, 2018, for recent research on salience, and Billieaz & Buson, 2013, for a discussion

of perceived formality of different variable features in Hexagonal French).

Concerning the variable structures at hand, each has a formal variant: ne retention

(negation), interrogative inversion (interrogative forms), and the IF (future-time

expression) (Armstrong, 2001; Mougeon et al., 2010). Despite this similarity, research on

the NNSs under investigation reveals differing outcomes with regard to targetlike use for

these forms and the variable structures as a whole. It will be recalled that these NNSs

appeared to be more targetlike with negation and interrogative forms than the future-time

expression. One possible hypothesis for the varying outcomes with these three variable

structures may have to do with the relative degree of formality of the variants. For instance,

although it may be the case that many variable structures have a formal variant, the level of

formality expressed when a speaker opts for the IF may be relatively lower than that of ne

retention and interrogative inversion, which may communicate a comparatively high level

of formality (see Mougeon et al., who rank variants along a continuum in terms of

formality, with five different levels of (in)formality). If true, this observation could

essentially mean that the stakes are higher for NNSs who have not mastered a variable

structure whose variants diverge notably in terms of formality (such as negation and

interrogatives) than for a variable structure whose variants show less divergence (i.e.,

future-time expression). In other words, consequences associated with non-nativelike use

of variable structures may vary from one structure to the next. This may be because the use

of a less formal variant (such as the PF or PI) in formal contexts may be less stigmatized

than the use of informal variants for the other two variable structures (cf. Kanwit et al.,

2015). Another possibility is that these three formal variants may be similar in their level of

formality, but that IF is a less salient indicator of formality than ne retention and

interrogative inversion, so NNSs could be less aware of this sociostylistic feature (see

Billiez & Buson, 2013). It may also be, however, that the degree to which NNSs feel

integrated into the target community and the extent to which they share the values of

formality present in the community (cf. Mougeon & Rehner, 2015) impact whether the

salience of the formality level of variants plays a role in differing outcomes among variable

structures.

In sum, by comparing the current study’s results on future-time expression to those

on negation and interrogatives, we were able to make a new observation about this group of

CJAL * RCLA Gudmestad, Edmonds, Donaldson & Carmichael

Canadian Journal of Applied Linguistics: 23, 1 (2020): 169-191!

185

NNSs’ sociolinguistic competence: at least with regard to specific linguistic and

sociostylistic constraints, they appeared to be less nativelike with future-time expression

than the other variable structures under investigation. We believe that this observation is

valuable, and we also hope to have shown that multiple, complementary analyses of the

same dataset offer great potential for furthering knowledge about near-native

sociolinguistic competence. While our preliminary reflection on the level of formality of

variants is not a generalizable conclusion, it is a hypothesis that emerged from multifaceted

analyses of a single dataset. Finally, we wish to stress that, although we have focused on

formality, complementary analyses have the potential to be beneficial for furthering

knowledge of other explanatory factors at play in the development of sociolinguistic

competence.

Conclusion

The current study has provided new knowledge about sociolinguistic competence in

additional language French by conducting a variationist analysis of the use of the IF, PF,

and PI to express futurity in informal conversations between NNSs and NSs. The findings

for the NNSs revealed both nativelike and non-native like patterns of use in terms of the

frequency of occurrence of the forms and the constraints that condition their use. We also

investigated a new sociostylistic factor in the investigation of future-time reference in

French – topic seriousness – and found that it conditioned use for NNSs and NSs.

Moreover, by comparing the current study’s findings to those of other examinations of

variation from the same dataset (Donaldson, 2016, 2017), we have offered important

contributions to SLA. The present investigation, in conjunction with Donaldson (2016,

2017), serves as an example of research that has conducted multifaceted analyses of the

same dataset and has shown that these types of analyses are important for further

developing a comprehensive understanding of near-native sociolinguistic competence. We

advocate, furthermore, that multiple, complementary analyses of a single participant group

are essential for advancing the understanding of additional language acquisition more

generally.

Correspondence should be addressed to Aarnes Gudmestad.

Email: [email protected]

Notes

1

We use this abbreviation to refer exclusively to near-native speakers, not non-native

speakers more generally. We recognize that near-nativeness is complex and operationalize

near-native in a way which is consistent with how other scholars have used this term (e.g.,

Bartning, Forsberg, & Hancock, 2009; Birdsong, 1992; Birdsong & Molis, 2001; Coppieters,

1987).

2

We do not use the terms ‘native-speaker norm/target’ and ‘NSs’ to refer to a monolingual

target. Instead, we use them generally to refer to individuals who have been exposed to the

target language since birth and who have had varying degrees of exposure to additional

languages.

!

CJAL * RCLA Gudmestad, Edmonds, Donaldson & Carmichael

Canadian Journal of Applied Linguistics: 23, 1 (2020): 169-191!

186

!

!

3

Due to space constraints, see Geeslin & Long (2014) for a discussion on the evaluation of

linguistic variables and the difference between same-meaning and same-function variation

(p. 31).

4

In Gudmestad et al. (2018) we investigated 12 NSs of Hexagonal French, 10 of whom we

examine in the current study. Since the focus of this previous investigation was on the role

of the present indicative in future-time contexts, we do not discuss it here.

5

Most of this research has adopted a sociolinguistic perspective (see Ayoun, 2014, and

Moses, 2002, for exceptions). Although there is work on different data types, the results do

not show a clear divergence by task type.

6

The size of the participant pool prevents us from being able to investigate the role of

intensity of contact with NSs (Blondeau et al., 2014). We leave this issue to future

research.

7

Since most of the participants are women, it may be that the current study’s findings

reflect women’s speech. Whether there are gender differences for future-time reference and

this population is left to future research.

8

Given the homophony between the conditional and IF in the first-person singular and the

fact that vous was very infrequent in the dataset, we did not include grammatical person in

the analysis.

9

Our operationalization of this factor diverges from Wagner and Sankoff (2011) because

quand ‘when’ and si ‘if’ statements were so infrequent that we were not able to examine

them as separate categories.

10

See Gudmestad et al. (2018) for a discussion of this variable and an operationalization of

LTI that goes beyond the clause level.

11

Although some researchers have called this factor adverbial specification, we use the

term LTI in order to make the distinction between morphological marking of futurity on

verbs and other (mostly lexical) marking of futurity. LTI includes the latter only. Our use

of LTI is also consistent with our previous work on this dataset (Edmonds et al., 2017 and

Gudmestad et al., 2018).

12

We recognize that it has become increasingly common in applied linguistics to generate

mixed-effects models with fixed effects and a random effect for participant. However,

although it is possible to run mixed-effects models in R, the dependent variable must be

binary. At the time we analyzed the data, R did support mixed-effects models when the

dependent variable is multinomial, which is the case in the current study. Nevertheless, we

compared the results reported here to a set of Bonferroni-corrected binary regression models

including participant as a random effect. These models revealed similar results to those found

with the two multinomial models.

CJAL * RCLA Gudmestad, Edmonds, Donaldson & Carmichael

Canadian Journal of Applied Linguistics: 23, 1 (2020): 169-191!

187

!

13

The NNSs used 34 certainty markers, 19 uncertainty markers, and 292 cases without an

(un)certainty marker. The NSs produced 24 certainty markers, 11 uncertainty markers, and

273 contexts without an (un)certainty marker.

14

See Mougeon et al. (2010), Howard (2012a), and Kanwit et al. (2015) for other research

that has investigated multiple variable structures with the same participant pool.

References

Armstrong, N. R. (2001). Social and stylistic variation in spoken French: A comparative

approach. Philadelphia/Amsterdam: John Benjamins. doi: 10.1075/impact.8

Armstrong, N. (2002). Variable deletion of French ne: A cross-stylistic perspective.

Language Sciences, 24, 153–173. doi: 10.1016/s0388-0001(01)00015-8

Armstrong, N., & Pooley, T. (2010). Social and linguistic change in European

French. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. doi: 10.1057/9780230281714_1

Ayoun, D. (2014). The acquisition of future temporality by L2 French learners. Journal of

French Language Studies, 24, 181-202. doi: 10.1017/s0959269513000185

Bartning, I., Forsberg, F., & Hancock, V. (2009). Resources and obstacles in very advanced

L2 French: Formulaic language, information structure and morphosyntax. Eurosla

Yearbook, 9, 185-211. doi: doi.org/10.1075/eurosla.9.10bar

Billiez, J., & Buson, L. (2013). Perspectives diglossique et variationnelle –

Complémentarité ou incompatibilité? Quelques éclairages sociolinguistiques.

Journal of French Language Studies, 23(1), 135-149. doi:10.1017/

S0959269512000397

Birdsong, D. (1992). Ultimate attainment in second language acquisition. Language, 68,

706-755. doi: 10.2307/416851

Birdsong, D., & Molis, M. (2001). On the evidence for maturational constraints in second

language acquisition. Journal of Memory and Language, 44, 235-249. doi:

10.1006/jmla.2000.2750

Blondeau, H., Dion, N., & Ziliak Michel, Z. (2014). Future temporal reference in the

bilingual repertoire of Anglo-Montrealers: A twin variable. International Journal of

Bilingualism, 18(6), 674-692. doi: 10.1177/1367006912471090

Blondeau, H., & Labeau, E. (2016). La référence temporelle au futur dans les bulletins

météo en France et au Québec : regard variationniste sur l’oral préparé. Canadian

Journal of Linguistics, 61(3), 240-258. doi: 10.1353/cjl.2016.0023

Comeau, P. D. (2011). A window on the past, a move toward the future: Sociolinguistic and

formal perspectives on variation in Acadian French. Doctoral dissertation, York

University.

Coppieters, R. (1987). Competence differences between native and near-native speakers.

Language, 63, 544-573. doi: 10.2307/415005

Donaldson, B. (2016). Aspects of interrogative use in near-native French: Form, function,

and register. Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism, 6, 467-503. doi:

10.1075/lab.14024.don

CJAL * RCLA Gudmestad, Edmonds, Donaldson & Carmichael

Canadian Journal of Applied Linguistics: 23, 1 (2020): 169-191!

188

Donaldson, B. (2017). Negation in near-native French: Variation and sociolinguistic

competence. Language Learning, 67, 141-170. doi: 10.1111/lang.12201 !!

The Douglas Fir Group. (2016). A transdisciplinary framework for SLA in a multilingual

word. The Modern Language Journal, 100(Supplement 2016), 19-47. doi:

10.1111/modl.12301

Edmonds, A., & Gudmestad, A. (2015). What the present can tell us about the future: A

variationist analysis of future-time expression in native and non-native French.

Language, Interaction and Acquisition, 6(1), 15-41. doi:10.1075/lia.6.1.01edm

Edmonds, A., Gudmestad, A., & Donaldson, B. (2017). A concept-oriented analysis of

future-time reference in native and near-native Hexagonal French. Journal of

French Language Studies, 27(3), 381-404. doi:10.1017/s0959269516000259

Ellis, N. C. (2012). Frequency-base accounts of second language acquisition. In S. M. Gass

& A. Mackey (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of second language acquisition (pp.

193-210). London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203808184.ch12

Fonseca-Greber, B. B. (2007). The emergence of emphatic ‘ne’ in conversational Swiss

French. Journal of French Language Studies, 17, 249–275. doi:

10.1017/s0959269507002992

Gass, S. M., Spinner, P., & Behney, J. (Eds.) (2018). Salience in second language

acquisition. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315399027

Geeslin, K., & Long, A. Y. (2014). Sociolinguistics and second language acquisition:

Learning to use language in context. London: Routledge. doi:

10.4324/9780203117835

Granger, S. (2009). The contribution of learner corpora to second language acquisition and

foreign language teaching: A critical evaluation. In K. Aijmer (Ed.), Corpora and

Language Teaching (pp. 13-32). Philadelphia/Amsterdam: John Benjamins. doi:

10.1075/scl.33.04gra

Gudmestad, A., & Edmonds, A. (2015). Categorical and variable mood distinction in

Hexagonal French: Factors characterising use for native and non-native speakers.

Canadian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 18(1), 107-131.

Gudmestad, A., & Edmonds, A. (2016). Variable future-time reference in French: A

comparison of learners in a study-abroad and a foreign-language context. Canadian

Journal of Linguistics, 61, 259-285. doi: 10.1353/cjl.2016.0024

Gudmestad, A., Edmonds, A., Donaldson, B., & Carmichael, K. (2018). On the role of the

present indicative in variable future-time reference in Hexagonal French. Canadian

Journal of Linguistics, 63, 42-69. doi: 10.1017/cnj.2017.41

Hansen, A. B. (2016). French in Paris (Ile-de-France): A speaker from the 14th

arrondissement. In S. Detey, J. Durand, B. Lake, & C. Lyche (Eds.), Varieties of

spoken French (pp. 123-136). New York: Oxford University Press. doi:

10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199573714.003.0009

Howard, M. (2012a). The advanced learner’s sociolinguistic profile: On issues of

individual differences, second language exposure conditions, and type of

sociolinguistic variable. The Modern Language Journal, 96, 20–33. doi:

10.1111/j.1540-4781.2012.01293.x

Howard, M. (2012b). From tense and aspect to modality: The acquisition of future,

conditional and subjunctive morphology in L2 French. A preliminary study.

Cahiers Chronos, 24, 201-223. doi: 10.1163/9789401207188_011

CJAL * RCLA Gudmestad, Edmonds, Donaldson & Carmichael

Canadian Journal of Applied Linguistics: 23, 1 (2020): 169-191!

189

Kanwit, M., Geeslin, K. L., & Fafulas, S. (2015). Study abroad and the SLA of variable

structures: A look at the present perfect, the copula contrast, and the present

progressive in Mexico and Spain. Probus, 27(2), 307-348. doi: 10.1515/probus-

2015-0004

Labov, W. (1972). Sociolinguistic patterns. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

MacWhinney, B. (2000). The CHILDES Project: Tools for analyzing talk. Third Edition.

Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Mitchell, R., Tracy-Ventura, N., & McManus, K. (2017). Anglophone students abroad:

Identity, social relationships, and language learning. London: Routledge. doi:

10.4324/9781315194851

Moses, J. (2002). The development of future expression in English-speaking learners of

French. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Indiana University.

Mougeon, R., Nadasdi, T., & Rehner, K. (2010). The sociolinguistic competence of French

immersion students. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters. doi:

10.21832/9781847692405

Mougeon, F., & Rehner, K. (2015). Engagement portraits and (socio)linguistic

performance: A transversal and longitudinal study of advanced L2 learners. Studies

in Second Language Acquisition, 37, 425-456. doi: 10.1017/s0272263114000369

Nadasdi, T., Mougeon, R., & Rehner, K. (2003). Emploi du ‘futur’ dans le français parlé

des élèves d’immersion française. Journal of French Language Studies, 13, 195-

219. doi: 10.1017/s0959269503001108

Poplack, S., & Dion, N. (2009). Prescription vs. praxis: The evolution of future temporal

reference in French. Language, 85, 557-587. doi: 10.1353/lan.0.0149

Poplack, S., & St-Amand, A. (2007). A real-time window on 19th-century vernacular

French: The Récits du français québécois d’autrefois. Language in Society, 36,

707–734. doi: 10.1017/s0047404507070662

Poplack, S., Lealess, A. and Dion, N. (2013). The evolving grammar of the French

subjunctive. Probus, 25, 139-195. doi: 10.1515/probus-2013-000

Poplack, S., & Turpin, D. (1999). Does the futur have a future in (Canadian) French?

Probus, 11, 133-164. doi: 10.1515/prbs.1999.11.1.133

Preston, D. (2000). Three kinds of sociolinguistics and SLA: A psycholinguistic

perspective. In B. Swierzbin, F. Morris, M. Anderson, C. Klee, & E. Tarone (Eds.),

Social and cognitive factors in second language acquisition: Selected proceedings

of the 1999 Second Language Research Forum (pp. 3-30). Somerville, MA:

Cascadilla.

Regan, V., Howard, M., & Lemée, I. (2009). The acquisition of sociolinguistic competence

in a study abroad context. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters. doi:

10.1111/j.1467-9841.2010.00447_7.x

Richards, J. C., & Schmidt, R. (2010). Longman dictionary of language teaching and

applied linguistics. 4

th

ed. Harlow, England: Longman. doi:

10.4324/9781315833835

Roberts, N. S. (2012). Future temporal reference in Hexagonal French. University of

Pennsylvania working papers in linguistics, 18, 97-106.

Roberts, N. S. (2016). The future of Martinique French: The role of random effects on the

variable expression of futurity. Canadian Journal of Linguistics, 61(3), 286-313.

doi: 10.1017/cnj.2016.29

CJAL * RCLA Gudmestad, Edmonds, Donaldson & Carmichael

Canadian Journal of Applied Linguistics: 23, 1 (2020): 169-191!

190

Sankoff, G., & Vincent, D. (1977). L’emploi productif du ne dans le français parlé à

Montréal. Le français moderne, 45, 243–254.

Sax, K. J. (2003). Acquisition of stylistic variation in American learners of French.

Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Indiana University, Bloomington.

Tagliamonte, S. A. (2012). Variationist sociolinguistics: Change, observation,

interpretation. New York: Wiley-Blackwell. doi: 10.1016/j.pragma.2012.04.006

Tarone, E. (2007). Sociolinguistic approaches to second language acquisition research –

1997-2007. Modern Language Journal, 91, 837-848. doi: 10.1111/j.0026-

7902.2007.00672.x

Tarone, E., & Liu, G. Q. (1995). Situational context, variation and second-language

acquisition theory. In G. Cook & B. Seidlhofer (Eds.), Principles and practice in

the study of language and learning: A Festschrift for H. G. Widdowson (pp. 107-

124). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

van Compernolle, R. A. (2015). Native and non-native perceptions of appropriateness

in the French second-person pronoun system. Journal of French Language Studies,

25, 45–64. doi:10.1017/s0959269513000471

Villeneuve, A., & Comeau, P. (2016). Breaking down temporal distance in a Continental

French variety: Future temporal reference in Vimeu. Canadian Journal of

Linguistics, 61(3), 314-336. doi: 10.1017/cnj.2016.30

Wagner, S. E., & Sankoff, G. (2011). Age-grading in the Montreal French inflected future.

Language Variation and Change, 23, 275-131. doi: 10.1017/s0954394511000111

CJAL * RCLA Gudmestad, Edmonds, Donaldson & Carmichael

Canadian Journal of Applied Linguistics: 23, 1 (2020): 169-191!

191

Appendix

Table A1

Distribution of verb forms according to temporal distance for NNSs

Temporal distance

IF

PF

PI

Total

#

%

#

%

#

%

Today

0

0

34

75.6

11

24.4

45

Less than a week

5

8.6

23

39.7

30

51.7

58

Less than a month

4

10.5

11

28.9

23

60.5

38

Greater than a month

13

20.0

33

50.8

19

29.2

65

Ambiguous

28

20.1

99

71.2

12

8.6

139

Table A2

Distribution of verb forms according polarity for NNSs

Polarity

IF

PF

PI

Total

#

%

#

%

#

%

Negative

6

19.4

20

64.5

5

16.1

31

Positive

44

14.0

180

57.3

90

28.7

314