Intraparty Factions and Interparty Polarization

By

Collin T. Schumock

Thesis

for the

Degree of Bachelor of Arts

in

Liberal Arts and Sciences

College of Liberal Arts and Sciences

University of Illinois

Urbana-Champaign, Illinois

2017

ii

Table of Contents

Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................ ii

Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1

Literature Review ........................................................................................................................... 2

Why It Matters .................................................................................................................... 2

Other Explanations of Polarization ..................................................................................... 4

What We Know about Intraparty Factions ......................................................................... 6

What We Do Not Know ...................................................................................................... 7

The Model ....................................................................................................................................... 8

The Approach...................................................................................................................... 8

The Set-Up .......................................................................................................................... 9

Assumptions .......................................................................................................... 10

Policy .................................................................................................................... 10

Actors .................................................................................................................... 11

Party-Unanimity Nash Equilibrium (PUNE) .................................................................... 13

The Games ........................................................................................................................ 14

Types of Games to Be Analyzed .......................................................................... 14

Game with Left and Right Parties ......................................................................... 15

Game with Left Party at Median and Right Party ................................................. 19

Game with Left and Right Party on the Same Side of the Median ....................... 22

A Brief Extension: Primary Elections .......................................................................................... 26

Modifications and Assumptions ....................................................................................... 27

Game Where Militants Represent the Median Party Voter .............................................. 28

iii

Game Where Militants Do Not Represent the Median Party Voter ................................. 30

Analysis ........................................................................................................................................ 32

Factions ............................................................................................................................. 32

Polarization ....................................................................................................................... 35

Extension........................................................................................................................... 36

Empirical Implications ...................................................................................................... 37

Limitations and Further Work ...................................................................................................... 37

Limitations ........................................................................................................................ 38

Further Work ..................................................................................................................... 38

Conclusion .................................................................................................................................... 39

References ..................................................................................................................................... 40

1

Introduction

The issue of factions in American political life is almost as old as the Union itself. In fact,

Hamilton and Madison discuss the issue in The Federalist Papers (“The Federalist Papers No.

9”; “The Federalist Papers No. 10”). Modern day party factions are described as “parties” and

“wings.” These subgroups seem to be increasingly competitive within their own parties; for

example, within the Republican controlled house, the Tea Party went head-to-head with Speaker

Boehner, a non-Tea Party Republican. Boehner pushed back on Tea Party attempts to shut down

the government over Planned Parenthood spending. This event would contribute to Boehner’s

resignation of his House seat and speakership in 2015. Another issue becoming increasingly

salient in American politics is that of polarization. Many data show that America has seen an

unchecked growth in polarization since the 1940’s, reaching what some have termed “peak

polarization,” (Drutman, 2016). Koger, Masket and Noel (2009) found that there is no

information sharing between formal Democratic and Republican party organizations and only 15

transfers of information between Republican and Democratic groups out of a possible 518 when

looking at “extended party networks.” They also found factionalization within both the

Democratic and Republican parties, with stronger factions on the GOP side (Koger, Masket and

Noel, 2009). Indeed, polarization and factionalization seem to grow together.

My research agenda is to examine the relationship between sub-party factions and

polarization in order to develop a model that relates the two. Do factions contribute to policy

polarization? And if they do, what is the mechanism by which this occurs?

In his seminal work, An Economic Theory of Democracy, Anthony Downs (1957)

develops a model of political competition and voting based on Harold Hotelling’s (1929)

principle of minimum differentiation. Taken together (and with Duncan Black’s work) we arrive

2

at the median voter theorem which says that a majority rule voting system should lead to the

outcome most preferred by the median voter.

However, contemporary politics forces us to reconsider this outcome. If the median voter

theorem holds, why is there not a single congressional Democrat who is more conservative than

a congressional Republican, and vice-versa? Why have elections consistently become less

competitive? Polarization has led to a less productive political system, marked by gridlock and

brinksmanship. And indeed, party factions have left both the Democratic and Republican Parties

divided and less effective. This research project will offer new insights into polarization,

factions, and their relationship.

Literature Review

Why It Matters

Previous academic work on polarization has centered on what are typically called “mass”

or “elite” explanations—polarization driven either by the mass population or by the elite political

leaders. Other scholars have studied the question in terms of institutional causes versus non-

institutional causes, such as gerrymandering or income inequality, respectively. Still other

scholars have looked at the “type” of polarization. This newest wave of polarization seems to be

primarily issue and ideology based, whereas the polarization of the 1940s and 1950s had little

basis in ideology or issue specific questions (Bafumi & Shapiro 2009).

Studies on the effect of polarization have looked at the impact it has on lawmaking and

the efficiency of the government, as well as the consequences that polarization has on the

economy. Economist Marina Azzimonti constructed a high frequency measure of political

polarization (instead of the biannual measures usually used by political scientists) to study the

economic impact of political polarization. She found that political polarization negatively affects

3

employment, investment and economic output. Indeed, political polarization played a role in

slowing the country’s economic recovery after the great recession (Azzimonti 2013).

Another area where the effects of polarization are seen is in redistricting. Partisan

redistricting, or gerrymandering, can have different effects. Of course, maps may be redrawn to

try to favor one party over the other. However, other more subtle effects may also come about.

Redistricting can lead to instability and uncertainty—these effects may be seen as “good” since

they lead to more competitive elections. However, this instability, according to scholars, can also

make it more difficult for representatives to represent their constituents well. Stable elections

contribute to greater knowledge of constituents’ wishes among representatives, as well as

constituents being better able to hold their representatives accountable (Yoshinaka & Murphy

2011).

Polarization may also lead to gridlock. Indeed, a study carried out using data from 1975-

1998 (before the recent spike in polarization) found that both divided government and

polarization lead to gridlock. Even when government is unified, high levels of polarization can

stall productivity (the current American political experience bears this out), whereas divided but

less polarized government may face less gridlock. The exception to polarization stalling

productivity is when a unified government is veto- and filibuster-proof (Jones 2001).

Importantly, many of these literatures have thought of polarization as what I call a “non-

discriminating” phenomenon, meaning the Democratic and Republican parties have diverging

ideologies and hence polarization has increased. The intraparty/interparty dynamic has largely

been ignored. Indeed, in some ways, the emergence of factions within the Democratic and

Republican parties can almost be thought of as “mini” polarization within the parties. As

differences within the party increase, the interparty dynamic also changes. However, this effect

4

need not be equal. If one party factionalizes substantially while another does not, it seems

reasonable to assume that polarization will increase, even if only one party is driving the change.

Of course, depending on the policy preferences of the different factions, polarization could

actually decrease. Hence, considering the effect of intraparty changes on interparty dynamics

offers new insights into the causes of polarization as well as the effects of factionalization.

Other Explanations of Polarization

Much time and ink has been devoted to studying the phenomenon of polarization in the

United States. Fiorina and Abrams (2008) studied political polarization in the mass American

public. Contrary to typical findings, they argue that the American public has not polarized

significantly and that studies of polarization have been the plagued by “misinterpretations and

misconceptions.” They argue that the American public has undergone sorting within subgroups.

Essentially, their argument is that the vast majority of Americans are moderate, while elites drive

polarization. Abramowitz and Saunders (2008) are critical of this hypothesis. They show, using

different data, that in fact only the least politically active members of the public are in the middle

of the political spectrum. According to these authors, politically active members of the public

(and the elite) have definitely polarized.

Another given cause of polarization is the media (which could be argued is an “elite”

explanation of polarization, although not in the typical “political elite” sense). This argument

posits that an increasingly partisan and polarized media has driven the polarization of the

electorate in this country. The story goes that partisan media emerging after the 1970’s has been

able to persuade voters to have more partisan and hence polarized views (Prior 2013). However,

there are some problems with this argument. One counter-argument is that partisan voters existed

prior to the emergence of highly partisan media and that once this media emerged these already

5

partisan viewers were drawn to it. This, then, does not represent the media polarizing voters, but

rather the media changing its coverage to attract more existing viewers. Further, studies have

shown that there are a number of problems in surveys where people self-report their media use.

Indeed, a review of literature on media and polarization found that although media audiences did

migrate when more partisan media became available, research has not supported the idea that

partisan media has led to a more polarized public (Prior 2013).

Other studies have considered alternative causes of polarization. A study on the effect of

gerrymandering found that the practice has little effect on polarization—although the authors did

observe the same sorting effect that Fiorina described (McCarty, Poole & Rosenthal 2009). The

same authors also investigated income inequality as a cause of polarization. Indeed, they found

that relative income is a strong predictor of party identification and increasing income inequality

can help explain polarization (McCarty, Poole & Rosenthal 2003). Finally, another interesting

explanation is that governmental failures can explain polarization. When policies fail, the two

main reactions are either “this policy was doomed to fail, let’s stop it” or “this policy can work,

we just didn’t use a strong enough form.” These opposite reactions lead to a divergence in voter

opinion and hence polarization (Dixit and Weibull 2007).

Taken together the conclusion can be that experts are not entirely sure what causes

polarization. Indeed, it is likely a combination of different groups and mechanisms—if income

inequality is an explanation, then mass driven polarization is likely the mechanism. If

gerrymandering turns out to be a large factor in polarization, then perhaps elite explanations

make more sense. The dynamic between intraparty factions and interparty polarization needs to

be explored further as a cause of polarization. If large, influential party factions can pull the

6

ideological median of a party to the left or right then it makes sense that the factions can be given

as a cause of polarization.

What We Know about Intraparty Factions

Intraparty factions are not new phenomena. Indeed, party factions have existed in the

United States since the development of the Republic (Sin 2014). These factions vary in size and

importance, with certain groups dominating parties at times and multiple groups sharing power at

others. Sin (2014) shows that since 1879, in general, two major intraparty groups have existed in

each party.

Much political science literature has focused on two levels—the individual and the party.

The individual can take the form of anything from a typical voting citizen to a lawmaker in

congress and, in the United States, the party is either the Democratic or the Republican Party.

Between these levels exists the intraparty factions that have, as Roemer (2004) notes, received

comparably much less attention. These factions are made up of individuals and sit within larger

parties. Sin (2014) says that, “Intraparty groups consist of clusters of individuals within a party

who share an ideology and a set of core policy preferences.” DiSalvo (2009) offers the following

definition of factions: “a party subunit that has enough ideological consistency, organizational

capacity, and temporal durability to influence policy making, the party's image, and the

congressional balance of power.” Clearly then, the defining feature of a party faction is a shared

ideology.

DiSalvo’s (2009) work on factions developed not only a good definition and

understanding of how they fit into parties, but also how they shape Congress. He found that

rising or dominant factions (in terms of caucus numbers) attempt to centralize power in congress,

while smaller factions seek to decentralize power. DiSalvo also found that factions offer a way to

7

channel and coordinate the interests of members, empowering them and giving them more clout

than they would have as individuals. Indeed, a different study found that members of intraparty

factions stick together more on ideology than they do with non-factional members of the same

party (Lucas and Deutchman 2009). This allows lawmakers with similar ideological beliefs to

coordinate and vote together on issues, even when those votes are against their own party.

Roemer (1999; 2001; 2004) says that three “types” of factions exist in each party:

reformists, militants and opportunists. Opportunists are interested only in their party winning,

reformists seek to maximize the expected utility of the party and militants are concerned only

with ideology, wanting a policy proposal as close as possible to its ideal point (Roemer 2001).

Roemer (2004) says that these factions within each party bargain over the party’s policy and that

parties compete with each other. This strategic play leads to what Roemer calls a party-unanimity

Nash equilibrium (PUNE). One of the key benefits of Roemer’s model is that it exists in two-

dimensional policy space.

Roemer’s taxonomy of factions is somewhat different from the previous explanations of

factions. Sin and DiSalvo consider factions to be ideologically distinct groups within a party.

Ostensibly, Sin’s and DiSalvo’s factions should want policy outcomes as close to their ideal

point as possible. Roemer’s factions have differing goals that orient their behavior. Opportunists

are office motivated, caring only that their party wins the election. while militants are

ideologically motivated, wanting a policy as close as possible to their party’s average.

Reformists, in a sense, fall in between.

What We Do Not Know

Although we have an idea of how factions and caucuses inside congress affect rule

making and voting, we do not have a great understanding of how factions affect the larger

8

political landscape, particularly in terms of polarization. It is reasonable to think that if factions

can help lawmakers move away from their parties’ position on certain policies, then similar

effects can be seen at the larger level. Further, if members of the general public see themselves

as belonging to certain factions or groups (the Tea Party, for example), then elites can appeal to

these voters and move even further from their party’s platform. With this understanding of how

factions operate within congress, a model of intraparty/interparty dynamics can start to be built.

The Model

The Approach

The approach I use to study polarization is adapted from the literature on political

competition. I extend the concept of equilibria to capture polarized policy. More extreme policies

entering the equilibrium space represents polarization in the sense that policies that are attractive

to a smaller subset of voters become tenable positions for parties to put forth. This, of course, is

notably different from mass polarization where a polarizing public is driving party positions. In

the framework I use, polarization can come about without any change in individual voter

preferences. There are valuable discussions to be had about which way of studying polarization

is the most appropriate. I argue that policy equilibrium is a valuable approach to studying

polarization. Although it might not explain why two neighbors won’t talk to each other due to

party identification, it does illuminate why and which policies are possible in the political arena,

including extremely partisan (and hence, polarized) ones. Indeed, the mere possibility, let alone

implementation, of extreme policy may have an endogenous effect of making the citizenry more

polarized.

I follow John Roemer’s work on party factions and political competition very closely,

particularly his book Political Competition: Theory and Applications (2001). In this book (and

9

earlier work), Roemer develops a new equilibrium concept called party-unanimity Nash

equilibrium (PUNE). Roemer developed this equilibrium concept in order to escape the

nonexistence of normal Downsian or Wittman equilibrium in multiple dimensions and with

uncertainty. The PUNE framework introduces sub-party factions to the model and allows for the

existence of equilibria even in the multidimensional/uncertainty game. Roemer (2001, 145)

states that “Researchers have responded to the nonexistence of Nash equilibrium in pure

strategies in the multidimensional game in five ways: The mixed-strategy approach, the

sequential game approach, the institutional approach, the uncovered set approach, [and] the

cycling approach.” Roemer goes on to explain why each of these approaches is unsatisfactory for

studying political competition. Indeed, I agree with his assertion that, if we believe elections are

simultaneous move games, none of the above approaches is satisfactory.

Although the PUNE concept was not designed for unidimensional games of certainty

(where Downsian and Wittman equilibria do exist), it certainly still “works” and thus I adopt the

concept. Since the game with factions better represents the reality of how parties are structured,

this concept should provide outcomes more similar to what is actually seen in U.S. politics. The

unidimensional game is just a simplification of the -dimensional game, where is one.

The Set-Up

The set-up of my model closely follows a number of examples given by Roemer (2001,

chaps. 1 and 8). His focus, again, is multidimensional games (although he considers some

unidimensional games) while mine is in one dimension. I leave the game quite general, although

I will make a few specifications in order to clarify the exposition. Thus, while much of the model

looks like Roemer’s (2001), there are a few variations for clarity. This game represents parties

competing on a policy issue where the distribution of voter types is known. To make the game

10

clearer I choose the policy issue to be a proportional tax rate and the voter types to be their

wages. Hence, the game is only made less general in the sense that the policy space (taxation) is

bounded from to and voter types (wages) are bounded from to infinity. I assume also that

this tax rate is the only issue that voters care about (this is the unidimensionality) and that voters

have single-peaked preferences over the tax policy.

Assumptions.

Altogether, I assume the following. Two parties, (where is the Right Party

and is the Left Party) have payoffs as a function of any number of things including their

probability of winning the election, the policy put into place and/or the policy their party plays. I

assume also a unidimensional policy space, over which voters have single-peaked preference

orderings. Finally, I assume certainty. That is, I assume that the parties know the distribution of

voter preferences (given by a probability function ) perfectly.

Policy.

Again, the policy over which the two parties are competing is a proportional tax rate.

Since the tax rate can neither be lower than 0%, nor greater than 100%, is the policy

space (unfortunately this makes for a confusing policy space, spatially). The tax collected per

person is simply a product of the tax rate, , and that person’s wage, . If we call the mean of the

population wages, , then it can be shown that that the average tax revenue per person is .

Namely, integrating over the wages gives the desired result,

(c.f. Ortuño Ortín and Roemer 2000, 8).

11

Actors.

The first actor in this game is the voter. Voters have direct utility functions that capture

their utility from both a private good () and a public good (). This utility function is

(c.f. Ortuño Ortín and Roemer 2000, 8). The private good in this case is an individual’s wage, .

Assuming that the government distributes the tax revenue equally in the form of the public good,

then . Hence, the voter’s indirect utility function is

which I will assume is continuous (c.f. Ortuño Ortín and Roemer 2000, 8; Roemer 2001, 18).

Now, the voter’s ideal policy (

, indexed for this voter’s wage) can be solved for by taking a

partial derivative with respect to and setting it equal to , and taking the minimum of this value

and 1 (since the tax rate cannot be greater than 100%), which yields,

(c.f. Roemer 2001, 14).

1

Other key groups of actors in this game are the factions. These are the factions that

Roemer (2001, chap. 8) lays out. The first faction is the “opportunists.” The members of this

faction are the same characters that appear in Downs’ An Economic Theory of Democracy

(1951). Their only concern is maximizing the probability that their party wins. They are solely

1

To further illustrate, consider an example given in Roemer 2001 (24-25) and assume the public good is a simple

redistribution of the tax income. Then,

and

for those with wages less than the mean

( ) and

for those with a wage greater than the mean ( ). Since in all real economies the median

wage () is less than the mean (i.e. ) a tax rate of unity will always prevail in this example (or the party

proposing the tax rate closest to unity will win). For this reason, I do not follow this example through the rest of the

way, in order to allow for more interesting cases.

12

interested in winning office and they have no concern for policy. Let

be a pair of policies

proposed by party one and party two and

be another pair of different policies. Then, for

opportunists,

,

where

is the probability party one wins playing

against

and

is the

probability party one wins playing

versus

(and vice-versa for party two) (Roemer 2001,

148).

Again, continuing to follow Roemer, the second faction is the “reformists.” These are the

characters of Wittman’s “Parties as Utility Maximizers” (1973) and “Candidate Motivation: A

Synthesis of Alternative Theories” (1983). The members of this faction care only about the

policy ultimately implemented by the winning party; the election/holding office is simply a

means to a policy end. Of course, to get to that end, the party does need to win the election.

Hence, the reformists maximize the party’s expected utility and for two different policy pairs,

(Roemer 2001, 148).

The third and final faction is that of the “militants.” This faction will be the most

important in the games and modifications presented shortly. The militant group is only interested

in the policy their party proposes. That is, they do not care about winning office (as the

opportunists do) or the policy actually enacted by the winning party (as the reformists do).

Militants can be thought of as hardliners or purists; their utility comes entirely from a “pure”

policy proposal from their party. Roemer (2001, 148) says that militants are “interested in

publicity.” The party adopting their ideal policy position acts as a sort of advertisement for that

13

ideological position. The idea is that putting forth this policy can convince some voters to shift

their preferences towards that of the militants. Since militants care only about their own party’s

position, the other party’s proposed policy has no bearing on their preference ordering, and hence

(Roemer 2001, 148). It is hard to say what exactly is meant when a faction is referred to outside

this framework. For example, is the Freedom Caucus a Republican reformist or militant faction?

I would argue that their behavior makes them appear closer to a militant faction than a reformist

faction, but arguments could be made either way. Ultimately, most examples of real-life factions

will likely have a mix of strains of the different types listed above.

A party then, is simply a composition of the three factions. The party composition can be

altered depending on which model is examined. For example, a game where the parties are made

up only of opportunists is the typical Downsian game and a game where the parties are made up

only of the reformists is a Wittman game. In these cases, the parties simply take on the functions

given above. In the game with factions, the parties do not have a single function, but rather, take

into account the different factions in order to create an ordering over policies. So, a party is said

to (weakly) prefer

to

if and only if all factions weakly prefer

to

(and for strict preference, at least one faction must strictly prefer

to

; Roemer

2001, 149). Due to this construction, the parties’ preference orderings (call

where indexes

the parties) will be incomplete. There will be many policy pairs where two factions prefer one

policy, while the other faction prefers the other policy (Roemer 2001, 149).

Party-Unanimity Nash Equilibrium (PUNE)

The concept of a “party-unanimity Nash equilibrium” (PUNE) will be vitally important to

the games presented in the next section and so I define the concept. The definition of a PUNE for

14

a pair of policies

is that the policy pair be a Nash equilibrium for the game with

and

and . In other words

(read: Party 1 prefers

to

) and

where (Roemer 2001, 149). Essentially, a policy pair satisfies the PUNE

criteria if (and only if) neither party can unanimously agree to alter its proposal, holding the

other party’s proposal fixed. To deviate from a given policy pair, one party’s factions must be at

least indifferent between the old policy and the deviation, and one faction must prefer the

deviation (again, holding the other party’s proposal fixed). If this condition holds, then (and only

then) will the party deviate, and hence the previous policy pair was not a PUNE (Roemer 2001,

149).

The Games

With the preliminaries now in place, different games with varying factions can be

examined using the PUNE concept. In this section, I set up a few different games (where parties

are arrayed in different spatial manners) and I find different equilibria. I also examine what

happens when different factional groups emerge within a party in the different games.

Types of Games to Be Analyzed.

For each individual game, I will solve for three different specifications. First, I will find

the Downs equilibrium, which is the game where both parties are made up only of opportunists,

and thus,

and

.

The Downs equilibrium will appear as a red diamond in the figures. The second specification I

will solve for is the Wittman game. This is the game where parties are made up only of

reformists, and thus,

15

and

.

Wittman equilibria will appear as a green square. Where there is a continuum of Wittman

equilibria, a green line will connect the endpoints. Finally, I will consider the game where there

are intraparty factions. In this game I will solve for the PUNEs (recall, parties do not have

preference functions, but rather incomplete preference relations). PUNEs will always be a

continuum in the unidimensional case. The continuum’s endpoints will be denoted with a purple

circle, and the rest of the continuum will be connected with a line.

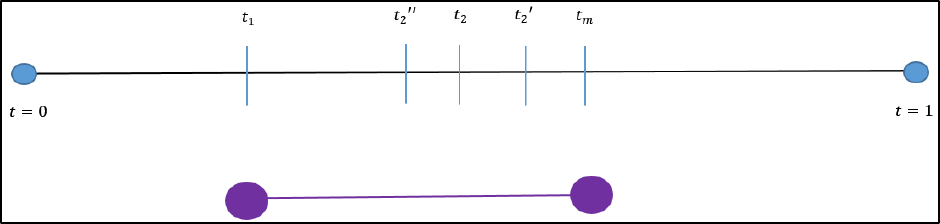

Game with Left and Right Parties.

The first scenario I consider is the most common of games, a game with a Left Party and

a Right Party. In this game, one party prefers policies left of the median (or represents voters

who prefer policies left of the median) and one party prefers policies right of the median (or

represents voters who prefer policies right of the median). Recalling that the policy space under

consideration is that of taxation, the Left Party actually sits to the right of the median spatially

(tax policies closer to unity) while the Right Party sits to the left of the median spatially (tax

policies closer to zero). Denote the median voter’s preferred policy

and the ideal policy for

the Right Party by

and the ideal policy for the Left Party by

. This “ideal policy” can either

be thought of as simply a policy that the party agrees is its ideal point, or, this point can be

thought of as being endogenously chosen by the members of that party (the median voter within

16

the Right Party has an ideal point of

). Thus,

describes the spatial ordering of the

preferences. This scenario looks as such:

Consider first the game with only opportunists. Again, this is the Downs game, where

parties compete only to win office. The well-known result is that both parties will propose the

median voter’s ideal policy. With the assumption that the indirect utility function of the voters is

continuous and single peaked and with an assumption that no voter is indifferent between two

non-identical policies this result can be proved (see Roemer 2001, 21-22) Neither party can

profitably deviate, as an deviation right or left will result in the party going from winning with

a probability to a

probability of winning. Thus,

is the Nash equilibrium and the

winning policy in this game.

Next, consider the game with only reformists. This is the Wittman game. In the

unidimensional game with certainty, where both parties are comprised only of reformists, the

result is again a Nash equilibrium at

. This can be proved if the assumptions used in the

Downs game hold and the additional assumptions of monotonicity of preferences and that the

fraction of voters whose ideal policy is less than some is continuous and strictly increasing on

(Roemer 2001, 29). With these reasonable assumptions, it can again be shown that (

is

the Nash equilibrium (see Roemer 2001, 30-33). The intuition behind this result is

straightforward. Suppose the Right Party is to the right of the median and the Left Party is to the

left of the median such that

. Then both parties win with their favorite policy

one-half of the time and the other party wins and gets their policy the other half of the time. But,

17

an deviation towards the median for any party would result in their probability of winning

going to one, and they would get their favorite policy (plus or less ) 100% of the time. Thus,

these small shifts towards the median are profitable deviations until both parties reach the

median.

And, finally, the game with three factions. It turns out that given the unanimous structure

of PUNE, the equilibria are somewhat uninteresting. Call

the policy preferred by the Right

Party’s factions and

the policy preferred by the Left Party’s militants. The PUNEs for this

game are simply the continuum from

to

. This is because, for all policies between

and

the Right Party’s militant factions have preferences opposed to the opportunists and reformists.

The militants constantly want the party to move further to the right on policy (to the left

spatially) towards their ideal point while the opportunists and reformists want the party to move

to the center to maximize the party’s chances of winning. This exact same conflict of preferences

exists in the Left Party and hence the policies between

and

are in the continuum of

equilibria. The Downs equilibrium, Wittman equilibrium and PUNE set are shown below (recall,

the Downs equilibrium is a red diamond, the Wittman equilibrium is a green square and the

PUNE set is a line showing the continuum with purple circle endpoints):

Now consider only the game with all three factions. What will happen if a new faction

emerges in either party? Well, first, since the opportunist and reformist factions have identical

ideal policies of

, a new opportunist or reformist faction for either party will have no effect on

18

the PUNEs and these new factions will be indistinguishable from the other

opportunists/reformists. A new militant faction, however, is more interesting. For clarity, I show

only the effect of one party’s militants changing, although the intuition holds for both parties.

First, consider the emergence of a new, more extreme militant faction in the Right Party. This

group’s ideal policy is

, while the old militant faction’s ideal policy remains at

. The new

continuum is the solid line, while the old continuum is the dashed line:

The PUNEs in this game are the same whether the old militants (at

) continue to exist

or not. The diagram without the

militants looks the same as the above figure except without

the vertical tick mark denoting the

militants’ ideal policy.

Now consider the emergence of a more moderate militant faction in the Right Party.

Again, this new faction has an ideal policy denoted by

. In this case, it does in fact matter if

the old militant faction at

continues to exist. If the old

militant faction itself moves to

(and so it is not really a “new” faction, but rather the old faction with new preferences) or

dissolves after the emergence of a new militant faction at

, then the PUNE set changes. If the

old militant faction continues to exist at

then the PUNE set does not change. The PUNE set

where the old faction no longer exists is represented with a solid line, while the PUNE set where

the old faction continues to exist is represented with a dashed line:

19

Game with Left Party at Median and Right Party.

The second game changes the placement of the parties slightly. In this game, the Left

Party sits exactly at the median (or, in the game with factions, the left’s militants are at exactly

the median) while the Right Party sits to the right (left spatially) of the median. So, in this

version,

, which looks like:

Starting again with the Downs/opportunist game, the Nash equilibrium is found to be the

median (and the Left Party’s ideal point). Recalling the assumptions made in the first (Left-

Right) game, this result can be shown true. The exact same logic holds. Each party is composed

only of opportunist factions, and hence each party cares only about maximizing their probability

of winning, which means playing the median voter’s ideal policy point, and winning office (with

policy

) with a one-half chance.

The Wittman/reformist game’s equilibrium, however, differs from the result found in the

Left-Right game. One assumption necessary to obtain a unique Wittman equilibrium is having

(Roemer 2001, 29). Since in this game

the condition of

does not

hold. Since both parties know the distribution of voter preferences, they know that when this

20

game is played

unless

; so,

will always win. In theory,

the Right Party could play any policy because its utility will be

regardless.

Therefore, the policy pairs that can be played are, theoretically, the entire policy space, but

will always win. It seems reasonable to assume that, at the very least, the Right Party will not

play a policy to the left of

. It seems though, that the Right Party is more likely to play either

(its ideal policy) or

(the winning policy).

The game with factions allows us to escape this odd result. The PUNEs will span from

to

. This narrows the policies played by the Right Party from all of them to a more

reasonable continuum. The presence of the militant faction in the Right Party will eliminate tax

rates less than

from being proposed. The Right Party’s opportunists prefer

be played and

thus the policies in the region between

and

may be proposed. All of the Left Party’s

factions actually agree on playing

since this is the ideal policy for the militants and the

reformists, and results in the highest probability of winning, satisfying the opportunists. The

Downs equilibrium, Wittman equilibrium and PUNEs are shown below (recall, the Downs

equilibrium is a red diamond, the Wittman equilibria appear as a green dotted line while the

green squares represent the Right Party’s and Left Party’s ideal polices and the PUNEs are

purple circles at the endpoints with a line showing the continuum. The winning policies for the

Wittman and PUNE are circled):

21

If new factions emerge, the result is very similar to that of the Left-Right game. If a new,

more radical militant group forms in the Right Party, then the PUNE space will expand further to

the right (left spatially). Again, this “emergence” could be either the existing militant group

becoming more radical, or an entirely new group forming while the old militants remain. In

either case, the PUNE set expands in the same way. Call again the new militant faction’s ideal

policy

, I depict the new PUNE space with a solid line in the figure below, while the original

PUNE set exists in the space of the dashed line:

The emergence of a more moderate militant faction in the Right Party leads to exactly the

same situation as before. If this new militant faction coincides with either the dissolution of the

old, more extreme militant faction, or the moving of the old militant faction to the new group’s

position, then the PUNE space shrinks (the solid line case in the figure). If, on the other hand, the

old (more rightist) militant faction continues to exist then the new, more moderate militant

faction has no effect on the PUNE set (the dashed line):

22

The case with the deviation of the Left Party’s factions is much more interesting. In the

first case, if they deviate to the left (spatially to the right) then the game breaks down into the

Left-Right game. Additionally, the known outcome/winning policy (namely,

no longer

exists. Of course, all policy pairs within the PUNE set continue to potentially be proposed. This

scenario looks as such, with the original scenario having a solid line and the version where a

more radical Left militant group emerges taking the dashed line:

Finally, there is the case where the Left Party’s militants deviate to the right (spatially

left) of the median. I omit depicting or discussing this case in a separate diagram as it will be the

last and final game set-up discussed in this section.

Game with Left and Right Party on the Same Side of the Median.

The last game has both the Left Party and Right Party sitting on the same side of the

median. This is not how one normally thinks of parties being arrayed. The normal depiction is

the Left-Right game where parties sit on either side of the median and argue for their ideological

position. Recalling footnote one, however, this set-up makes sense for certain policies. As is

worked through in the footnote, if the public good is a simple redistribution of the tax, and the

median wage is less than the average wage, then the winning policy should always be a tax rate

of unity (entire redistribution of wealth). However, consider that the Right Party represents the

super wealthy and the Left Party represents merely the wealthy. In this case, both parties would

propose tax rates less than the median voter’s preferred tax rate! This is as far as I will follow

23

this example here (I want to leave open the possibility of voters who favor tax rates higher than

the median voter, and this example does not allow for this), but it is a good illustration of how

this arrangement of parties could come about. This arrangement (where

) is depicted

below.

For one last time, the Downs/opportunist equilibrium again resides at the median voter’s

preferred policy. Recalling the assumptions and logic of the previous games with only the office-

seeking players, this result can again be shown true. Playing the median voter’s favorite policy

will result in a one-half chance of winning, while playing any other policy gives no chance of

winning office.

The Wittman/reformist equilibrium is more interesting in this set-up than the previous

game where the Left Party was at the median. Since the Left Party’s ideal policy is closer to the

Right Party’s ideal policy than the median voter’s preferred policy, the Right Party will not play

anything to the right (spatially left) of the Left Party’s ideal policy. Thus, the condition where

any policy being played by the Right Party in equilibrium is avoided. The Right Party cannot do

any better than the Left Party’s ideal policy and can only do worse if it plays a policy more leftist

than that of the Left Party. The Left Party cannot do any better than to simply propose its ideal

policy. Hence, the Wittman equilibria is bounded between and

and policy

will always

be the enacted policy (the Left Party will win with probability one if the Right Party plays

anything else, or the Right Party can simply play

as well and each party wins with probability

one-half, but

is enacted regardless).

24

Lastly, the game with all three factions. The PUNE set for this game is interesting.

Although both parties’ factions prefer tax rates lower than the median voter’s ideal policy, all

policies up to the median voter’s ideal point are included in the PUNE set. This is because of the

presence of opportunists. The PUNE concept does cut off any rates less than

, unlike the

Wittman game, because the opportunist and militant factions of the Right Party prefer

while

the reformists are indifferent. In this game, there is no policy that will be enacted for sure.

Instead, whichever policy is proposed that is closest to the median will win, but there is no

guarantee that either party will, for instance, propose

. The Downs equilibrium, Wittman

equilibrium and PUNE set are shown below (recall, the Downs equilibrium is a red diamond, the

Wittman equilibria appear as a green dotted line while the green squares represent the Right

Party’s and Left Party’s ideal polices and the PUNE set are purple circles at the endpoints with a

line showing the continuum. The winning policy for the Wittman equilibria is circled):

The shifting of factions in this game looks the same as in the previous games. If the Right

Party has a new, more extreme faction emerge (whether the old faction becomes more extreme or

an entirely new group forms) the PUNE set will expand closer to . The new faction’s policy

25

is

and the new PUNE set is represented with the solid line, the old equilibria are represented

with a dashed line:

The emergence of a new, more moderate militant faction in the Right Party (again with a

policy of

) results in the same shifts as before. If the old militant faction shifts to this new

position, or if the old militant faction dissolves after the new faction emerges, then the PUNE

space shrinks. If the old militant faction continues to exist at its old position then the PUNE set

does not change. Below, the PUNE set where the old militant factions shift or dissolve are given

with the solid line, while the PUNE set when the old militant faction stays at its

position is

given with the dashed line:

26

The Left Party is a different situation. In the Left Party, the “most extreme” (in terms of

leftist policy) faction is the opportunists. Moreover, since the Right Party prefers policies to the

right of the Left Party’s militants, new Left militants will actually not shift the PUNE space. I

show both of these “cases” in the figure below with

being the new, more leftist faction and

being a new Left Party militant faction with more rightist policies. In either case the PUNE

set does not change.

The Left Party’s militants shifting only “matters” if they shift as far as the median (in

which case the game changes to the game with a Right Party and a Left Party at the median) or if

they shift beyond the median to the left (in which case the game reverts to the Left-Right game).

A Brief Extension: Primary Elections

I present now a brief extension of the factional game—a version where both parties first

have primary elections before moving into a general election. To my knowledge, neither Roemer

nor any other researcher has extended the PUNE/factional model to primary elections. Two

preliminary approaches are presented in this section, and then the framework of what might be a

more satisfactory (and realistic) approach is presented in the “further work” section. The first

stage is an election amongst the candidates (and factions) to determine who will represent the

party. The second stage of the game is competition between the parties (and their factions) in the

general election. Now, this set-up likely only works when we consider that there are, for

27

example, many elections for House seats. When these primaries are aggregated, all of the

factions will be present in the greater “competition” between the two parties in the general

election (not in any one election, but in the bigger picture as a whole). This framework might not

fit as well for the Presidential election, however, because only one candidate wins from each

party and so the factional type is “decided” after the primary. However, even the Presidential

election might fit this model, because prior to the primaries there is competition between parties

on which policies are the best for the country.

Modifications and Assumptions

Regardless, I proceed to present the extension. Assume now that the set of voters the

Right Party represents have a median voter with ideal point

and the set of voters the Left

Party represents have a median voter with ideal point

. Assume further that

(where

is the median of the entire set of voters) and thus these are primaries before the Left-

Right game presented above. This arrangement is presented below:

For the primary game, I drop the reformists so that the competition is only between the

opportunists and reformists (an explanation for why is provided in footnote two on page 29; a

possible way of proceeding without dropping any factions is presented in the “further work”

section). Let the policy the opportunists play in the primary be

(where for the Right

and Left Parties, respectively), and the policy the militants play be

. The factions are also

28

allowed to change their played policies between the primary and general election (a potential

version where this is not the case is presented in “further work”).

I also make a slight modification to the opportunists’ utility functions. For the

opportunists, their utility function in the primary becomes:

(note that the index should be the same for all of the above as factions in the same party are

competing against each other in the primary election) while their utility function in the general

election remains the same as before. Therefore, in the primary, the opportunists play a policy that

maximizes their probability of winning the primary election and then in the general election they

play a policy that maximizes their party’s chances of winning the general election.

The militants’ utility function is essentially the same thing, although technically it is

written as:

(again taking the same indexes) while their utility function in the general election remains the

same as before. The militants, unlike the opportunists, will play the same policy in the primary

and general elections. (The only case where the opportunists would play the same policy in the

primary and general election with these changed utility functions is when

.)

Game Where Militants Represent the Median Party Voter

In the first of the two versions of this primary-general game I situate the militant factions

so that their ideal point is the same as the party’s median voter (they could also represent the

average party member, as Roemer 2004, 17 discusses). In response, the opportunists will also

play the party’s median voter’s ideal point and both candidates/factions will win the primary

election with probability one-half. The arrangement is shown below, where the policy played by

29

the opportunists in the primary is a gold triangle and the policy played by the militants is a green

star

2

:

If a new faction emerges in either party and it is located at any point either than

or

it will lose the primary for sure. If the new faction it located at

or

then it is not actually

any different from the existing

militants and

opportunists. I do not consider here the case

where the militant faction shifts (and so has an ideal policy other than the party median voter’s)

but I present that as an entire separate case in the proceeding subsection.

Since the factions in both parties win with a one-half chance each, there are four possible

outcomes: the Right Party’s militants win and the Left Party’s militants win, the Right Party’s

militants win and the Left Party’s opportunists win, the Right Party’s opportunists win and the

Left Party’s militants win or the Right Party’s opportunists win and the Left Party’s opportunists

win. Instead of presenting all of these cases in separate figures, I present them all in one below.

The PUNEs for the Right Party militants vs. Left Party militants, Right Party militants vs. Left

Party opportunists, Right Party opportunists vs. Left Party militants and Left Party opportunists

2

Here we can see why it is necessary to drop the reformists. Imagine that the reformists existed in this game, and

that their utility function also adjusted as the opportunists’ does in order to maximize the expected value of the party

first in the primary election and then in the general election. Then, in order to implement the policy that will

maximize the expected value of the party, they must also maximize their probability of winning. This results in the

reformists and opportunists “sandwiching” the militants on either side of

in order to increase their chances of

winning. In this game with all three factions, the militants will never win the primary election.

30

vs. Right Party opportunists are all presented below as purple circles, with the winning policy (if

there is one) circled:

If the opportunists win the primary, they subsequently move to the population median

voter, winning if they face a militant or winning with a one-half probability if facing another

opportunist. If the militant faction wins the primary, they win with a one-half chance in the

general election if they face a militant faction from the other party in the general election and

lose for sure if they face an opportunist faction from the other party.

Now, this is for only one election. If we can think of “aggregating” these individual

elections into the larger political competition between the two parties, then we can arrive back at

the Left-Right game picture of before. Recall that I disposed of the possibility of militants

moving from the party’s median voter. This deviation would result in the game next depicted.

Game Where Militants Do Not Represent the Median Party Voter

If the militants do not represent the median party voter (or originally do but deviate away

from the median party voter) then the opportunists win in all primaries and the general election

breaks down into the Downs/opportunist game where the median voter theorem is the result.

Consider that the rightist militants locate themselves at a point more right than the median Right

31

Party member (

) and the leftist militants locate themselves at a point more left than the

median Left Party member (

). Then the game looks as such:

The result of this game is that the opportunists win the primary with a probability of one.

In the case of the Right Party, the opportunists can locate themselves at any point to the left

(right spatially) of

such that

(and the same with the Left Party but in the

opposite direction). This means that, depending how extreme the militant group is, the

opportunists can locate themselves closer to the moderate side of the party median voter ( away

from the point where their probability of winning drops to one-half). This is important if things

like credibility and accusations of “flip-flopping” matter in the general election. Call the point

the point away from where the probability of opportunists winning in the primary drops

from one to one-half. The policies played look as such, with the opportunists playing any policy

within the continuum denote by the gold line with gold triangle endpoints and the militants

playing the green star:

32

Therefore, it is clear that the opportunists will always win (note that the opportunists play

a policy at least a shade more moderate than the militants do in order to ensure victory). This

leads to a general election between opportunist factions from both parties and the median voter

result, which simply looks as so (the purple circle is the PUNE/Downs equilibrium):

Of course, this game would be more interesting if factions were not allowed to move their

policy positions between the primary and general elections. If this were the case then we would

see both the Left and Right Parties playing something other than the median voter’s preferred

policy, even though the opportunists won the primary election in both cases. And, this idea of

committing to one policy position is indeed quite interesting and might match what is seen in the

real world better. I explore this extension in the “further work section.”

Analysis

Now, with a very complete picture of the various games, equilibrium possibilities and the

effects of changing militant positions, a number of observations may be made about factions and

polarization. Taken together, some empirical implications may also be made.

Factions

The first and perhaps most obvious observation that can be made regarding factions is

that they do, in fact, matter. In every version of the game, the PUNEs provided a different set of

potential policy pairs that could be proposed when compared with the Downs and Wittman

games. Indeed, only in the “Game with Left Party at Median and Right Party” did the faction

33

game produce a sure policy winner. And even in this game, the Right Party could propose any

number of policies in equilibrium. Factional games (and PUNE) allow us to escape the idea that

both parties will play the same policy (namely, the median’s preferred policy) in equilibrium.

The Wittman game also produces a similarly unsatisfactory result in the Left-Right game (both

parties playing the median) which factions and PUNE again allows us to escape. Certainly, the

large continuum that is seen in the faction game is not entirely desirable (a problem that does not

exist in multidimensional games with uncertainty, see Roemer 2001) but it seems to be a closer

reflection of reality than both parties proposing the same policies.

Factions and PUNE also seem to provide for more realistic results in the other two game

structures (Left Party at median and both parties on one side of the median). The Wittman

equilibria in the “Left Party at the Median with a Right Party” is particularly unsatisfying as, in

equilibrium, the Right Party can play any policy in the policy space since it knows the Left Party

will win regardless. PUNE and factions confine the policy pairs to a more reasonable space, and

eliminate the possibility of the Right Party playing a policy to the left of the Left Party. In the

game where the parties are on the same side of the median, factions expand the Wittman

equilibrium out to the median, while eliminating policies more rightist than the Right Party’s

militants’ ideal point. The PUNEs end up being the same as the game where the Left Party is at

the median, with the exception that there is not a “guaranteed policy winner.” In the game where

the Left Party is at the median, the median policy will win for sure, while in the game where both

parties are on one side of the median a number of different policies may win (although it is

known that the policy closest to the median in the policy pair will win).

Something can also be said about the “importance” of individual factions. Generally,

within each party, only two factions “matter” (see also Roemer 2001, 150). In all cases except

34

the case where one party is at the median (in which case all of the party’s factions have the same

ideal point), the two factions that matter within the party are the militants and the opportunists.

The militants “pull” their party in their ideological direction while the opportunists “pull” the

party towards the median. This dynamic is what produces the large continuum of equilibria. In

the case where there are multiple militant groups within a party it was shown that only the “most

extreme” (i.e. furthest left militant group in the Left Party and furthest right in the Right Party)

matters insofar as these militants are the one setting the endpoints of the PUNEs. This result also

fits nicely with Sin’s (2014) finding that two major intraparty groups have existed in each U.S.

national party since 1879.

One final thing can be said about factions before moving on to polarization and that is

that factional strength (likely) matters. Given the way that the PUNE concept is constructed

(requiring unanimity among the factions), there has been no discussion of factional strength in

this study. Roemer (2001, 152) acknowledges that this is a criticism of the PUNE concept and

explains how PUNE can be used as a bargaining concept (Roemer 2001, 155-158). Without

going into this explanation, it is simple to think through why factional strength matters. Consider

for example if the militant faction is strong within a party while the others are weak. The

unanimity idea probably does not fit as well in this case. It makes sense to think that the policy

the party proposes will be closer to the militant’s ideal point (and the reverse is true when the

opportunist or reformist (in the Left-Right game) is strongest). However, when factions have

relatively equal strengths within the party, then the PUNE concept likely fits the policies that

may be proposed much better. If factions are equally strong within a party, it should be expected

that the party would play some policy within the PUNE space (as opposed to playing no policy

and receiving the payoff of the other party’s policy by default).

35

Polarization

Returning to the polarization piece it is clear that factions increase polarization if we

think of polarization as more extreme (further from the median) policy proposals. In the Left-

Right game, factions expand the policies that may be proposed (and win) significantly. The

Downs and Wittman game show that only the median policy will be played and win, while the

factional game includes all policies from the Right Party militants’ ideal point to the Left Party

militants’ ideal point.

In the game where one party is at the median, the winning policy is not polarized (in the

sense that the median policy will win in the Downs, Wittman and faction game) but there is

polarization in the policies that may be proposed. Translating to real life, this might look like one

party proposing radical, “polarized,” policies, even if these policies will never win.

Finally, in the game where both parties are on one side of the median, factions have the

interesting effect of making more moderate policies possible equilibria. In the game then, where

both parties are on the same side of the median, the polarizing effect of factions is somewhat

ambiguous. Compared to the Downs game, factions do result in polarization, while compared to

the Wittman game the effect is, in fact, ambiguous. The factions eliminate the possibility of

policies to the right of the Right Party being proposed, while opening up the possibility of

policies closer to the median than the Left Party being proposed. If polarization is thought of

slightly differently (the distance of proposed policies from the median voter’s ideal point) then

factions actually reduce polarization in this game compared to the Wittman game, as policies

closer to the median enter the PUNE set.

36

Extension

A separate, brief analysis of the extension (with primaries) yields a few interesting

results. The first falls out of the presentation of the two games—with the militants at the party

median and the militants not at the party median. Anytime the militants played something other

than the party median they lost. This does not necessarily mean that militants must play the party

median (as nothing in their utility function says that they care about winning) but it does seem

like the formulation where the militants play the median party member’s ideal policy makes the

most sense.

In this case, (where the militants are located at each of the party medians, respectively) a

more interesting general election results, namely, a general election that is not always between

only opportunists. When the militants represent the party’s median voter, the militants and

opportunists each win with probability one-half, leading to four different general election

permutations. If these elections are “aggregated” into party competition as a whole, then the

result looks like that of the Left-Right game.

What does this say about polarization? Well, in the case where the militants locate at the

party’s median voter it says essentially the same thing as the above section on polarization—in

the Left-Right game, factions increase polarization. Even in the individual elections (not

“aggregating” them into a general idea of competition) a general election between two primary-

winning militant factions leads to a policy polarized general election. If militants do not locate

themselves at the median, and factions are allowed to change their policy from the primary to the

general election, then a primary election with extreme policy proposals is seen while the general

election becomes much more moderate. If, however, factions are not allowed to move between

37

the primary and general election then polarized policy is seen in the general election, but not to

the extent of the polarization in the normal Left-Right game.

Empirical Implications

Taken together, the above analysis leads to some empirical implications. The predictable

effects of, for example, the emergence of a more extreme militant group, allow some more

generalized claims to be made. I list some implications below.

1. If factions are equally strong, then polarization will be at its highest.

a. If the militant factions are the strongest in each party, then polarization will be as

high as the case where factions are equally strong.

b. In general, if factions are weak, then polarization will be lower.

2. If a new, more extreme militant faction emerges, then polarization will increase.

3. If a new, less extreme militant faction emerges, then a decrease in polarization will only

follow if the old militant faction no longer exists (if it dissolves or shifts to the new less

extreme position).

4. In the case of a primary election, if a shift in policy is seen after a primary, then the

dominant/winning faction of the party is likely the opportunists.

Limitations and Further Work

There are a number of limitations with the model and games presented here. These

limitations are important to recognize as they have implications for the analysis of factions and

polarization, as well as the empirical predictions. Much of the further work that can be done on

this topic would involve eliminating some of these limitations.

38

Limitations

The first and most obvious limitation of this study is the specification of a unidimensional

game with certainty. The idea that voters care only about one issue and that parties know voters’

preferences perfectly is, of course, unrealistic. In reality, many issues are relevant to voters and

there is always some uncertainty about voters including both their preferences and whether or not

they will vote. A second limitation of this study is the lack of any idea of factional strength.

Although some basic ideas of how factional strength may matter were presented in the analysis, a

more rigorous treatment of this issue would be beneficial.

Further Work

Indeed, many of the above limitations have already been addressed. Roemer (2001 and

others) presents the case of multidimensional policy spaces and uncertainty. Roemer (2001) also

considers games where the parties have endogenous policies of the voters’ preferences whom

they represent. What hasn’t been done, to my knowledge, is to extend these models further to

consider issues of polarization and the effects of the emergence of new factional groups. Roemer

also addresses the issue of factional strength, but this topic could be extended by considering the

implications factional strength has on polarization and how emerging/dissolving factions can

shift the policy space and polarization.

Another area of further work that would be fruitful is a tightening of the extension

presented on primary elections. Ideally, the need to drop the reformists would be overcome and

new utility functions that capture both the primary and general elections could be built for the

opportunists and reformists (the militants by construction do not care about winning).

Additionally, restricting or eliminating a faction’s ability to move after the primary is probably a

39

better representation of real life and incorporates the disutility that a candidate receives from

“flip-flopping” and not committing to a policy position.

Conclusion

This paper has studied the relationship between intraparty factions and polarization. A

model of party competition with factions and an equilibrium concept called PUNE (both of

which are due to Roemer) were used to investigate various unidimensional games with certainty

where parties and factions have varying preferences. I extended Roemer’s work by presenting

basic spatial models to show how factions change the equilibrium space in comparison to Downs

and Wittman models. Specifically, I showed how new militant factions can expand or contract

the PUNE space. I then developed a brief and novel extension of the model to primary elections,

showing how factions interact with multi-stage competition. Office motivated factions (and their

candidates) will switch positions between the primary and general elections if they can, while

militants will not. Next, I analyzed my findings and, using a policy-based concept of polarization

related how factions (and changes in factions) can effect polarization. The emergence of more

extreme militant groups will widen the PUNE space while the emergence of more moderate

militant groups will only shrink the PUNE space if the old militant faction dissolves or moves to

the new militant’s point. This expanding of the PUNE space can be thought of as an increase in

polarization, while the shrinking can be thought of as a decrease in polarization (compared to the

original levels). In either case, the game with factions had greater levels of polarization than the

game without. If individual elections can be “aggregated” to construct a larger picture of

interparty competition, then the result from the primary game has the same implications as the

Left-Right game in terms of polarization. Finally, I noted limitations to this study and future

work that may be done.

40

References

Abramowitz, Alan I., and Kyle L. Saunders. 2008. “Is Polarization a Myth?” The Journal of

Politics 70(2): 542–55.

Azzimonti, Marina. 2013. The Political Polarization Index. Federal Reserve Bank of

Philadelphia. http://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:fip:fedpwp:13-41.

Bafumi, Joseph, and Robert Y. Shapiro. 2009. “A New Partisan Voter.” The Journal of Politics

71(1): 1–24.

DiSalvo, Daniel. 2009. “Party Factions in Congress.” In Congress & the Presidency, Taylor &

Francis, 27–57.

Dixit, Avinash K., and Jörgen W. Weibull. 2007. “Political Polarization.” Proceedings of the

National Academy of Sciences 104(18): 7351–56.

Downs, Anthony. 1957. An Economic Theory of Democracy. New York: Harper.

Drutman, Lee. 2016. “American Politics Has Reached Peak Polarization.” Vox.

http://www.vox.com/polyarchy/2016/3/24/11298808/american-politics-peak-polarization

(April 30, 2017).

Fiorina, Morris P., and Samuel J. Abrams. 2008. “Political Polarization in the American Public.”

Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 11: 563–88.

Hotelling, Harold. 1929. “Stability in Competition.” The Economic Journal 39(153): 41–57.

Jones, David R. 2001. “Party Polarization and Legislative Gridlock.” Political Research

Quarterly 54(1): 125–41.

Koger, Gregory, Seth Masket, and Hans Noel. 2010. “Cooperative Party Factions in American

Politics.” American Politics Research 38(1): 33–53.

41

Lucas, DeWayne, and Iva Ellen Deutchman. 2009. “Five Factions, Two Parties: Caucus

Membership in the House of Representatives, 1994–2002.” In Congress & the

Presidency, Taylor & Francis, 58–79.

McCarty, Nolan, Keith T. Poole, and Howard Rosenthal. 2009. “Does Gerrymandering Cause

Polarization?” American Journal of Political Science 53(3): 666–80.

Ortuño Ortín, Ignacio, and John E. Roemer. 2000. Endogenous Party Formation And The Effect

Of Income Distribution On Policy. Instituto Valenciano de Investigaciones Económicas,

S.A. (Ivie). https://ideas.repec.org/p/ivi/wpasad/2000-06.html.

Prior, Markus. 2013. “Media and Political Polarization.” Annual Review of Political Science 16:

101–27.

Roemer, John E. 1999. “The Democratic Political Economy of Progressive Income Taxation.”

Econometrica 67(1): 1–19.

———. 2001. Political Competition: Theory and Applications. Cambridge: Harvard University

Press. https://books.google.com.na/books?id=fe_kVqYn4xQC.

———. 2004. “Modeling Party Competition in General Elections.” Cowles Foundation

Discussion Paper No. 1488. SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=614548.

Sin, Gisela. 2014. Separation of Powers and Legislative Organization: The President, the

Senate, and Political Parties in the Making of House Rules. New York: Cambridge

University Press.

“The Federalist Papers No. 9.” 1998. http://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/fed09.asp (May 5,

2017).

“The Federalist Papers No. 10.” 1998. http://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/fed10.asp (May 5,

2017).

Wittman, Donald A. 1973. “Parties as Utility Maximizers.” The American Political Science

Review 67(2): 490–98.

42

———. 1983. “Candidate Motivation: A Synthesis of Alternative Theories.” The American

Political Science Review 77(1): 142–57.

Yoshinaka, Antoine, and Chad Murphy. 2011. “The Paradox of Redistricting: How Partisan

Mapmakers Foster Competition but Disrupt Representation.” Political Research

Quarterly 64(2): 435–47.