PARTY FACTIONS AMONG THE VOTERS

Stephen K. Medvic

a*

and Berwood A. Yost

b

Prepared for delivery at the 2021 State of the Parties: 2020 and Beyond Virtual

Conference, November 4 – 5, 2021. The Ray C. Bliss Institute of Applied Politics, The University

of Akron

a

Department of Government, Franklin & Marshall College

b

Center for Opinion Research, Floyd Institute for Public Policy, Franklin & Marshall College

* Corresponding author: stephen.medvic@fandm.edu

1

Party Factions Among the Voters

“A classic issue in studies of party organizations,” Pippa Norris (1995) noted some

twenty-five years ago, “is how we explain party division and ideological conflict” (29). This

long-standing interest among party scholars notwithstanding, the study of party factions has

experienced something of a resurgence in recent years (see, for example, Noel 2016; Hansen,

Hirano, and Snyder 2017; Thomsen 2017; Conger, et al. 2019; Clarke 2020; Blum 2020; and

Masket 2020). Much of that work, as much of the scholarship on factions generally, focuses on

factions among party elites, particularly members of Congress. This study contributes to our

understanding of party factions by exploring factional affiliation among voters. Most partisans

are willing to identify with one of the factions in their party and significant differences exist

between co-partisans who affiliate with different factions in the party.

The Study of Factions

Concern that part of a polity might organize to advance its own interests, rather than

the common good, has a long history. First as “factions” and later as “parties,” these “partial”

entities have long been viewed skeptically. As Bolingbroke famously wrote, “party is a political

evil, and faction is the worst of all parties” (Bolingbroke 1997 [1738], 257).

Attempting to understand the nature of parties perhaps more dispassionately, political

scientists turned their attention to factions in the middle of the twentieth century.

1

In his

analysis of factions in the one-party South, V.O. Key (1949) initially defined a faction as “any

combination, clique, or grouping of voters and political leaders who unite at a particular time in

1

Sartori (1976) resisted the use of the term “faction” to describe party sub-units and maintained that American

political scientists were largely responsible for the adoption of the term, which, to his mind, had been done

“unfelicitously” (72).

2

support of a candidate” (16). He would later use the term, more generally, to refer to an

“informal party-system-within-a-party” (Key 1958, 320).

2

For Austin Ranney and Willmoore

Kendall (1956), if a political party is “a large-scale organization whose purpose is to control the

personnel and policies of the government,” a faction is “an element inside a party whose

purpose is to control the personnel and policies of the party” (126, emphases in original).

Notwithstanding Key’s inclusion of voters in his original conceptualization, most studies

of factions consider them an elite phenomenon. Richard Rose’s (1964) classic treatment is

emblematic. A faction, argued Rose, is “a group of individuals based on representatives in

Parliament who seek to further a broad range of policies through consciously organized political

activity” (37; see also Rose 1974, 313). That is, factions have “membership based in Parliament,

rather than in the civil service or elsewhere” (1964, 37). As we’ll see, studies of American party

factions tend to focus on elected officials and party activists and only rarely on voters.

Conceptualizations of factions commonly point to, among other elements, their

organizational capacity (DiSalvo 2012, 5). Factions are said to have “an organizational

hierarchy” (Key 1958, 320); to be “organized to act collectively” (Zariski 1960, 33); to be “self-

consciously organized as a body” (Rose 1964, 37); to have met “the minimal characteristics of a

rudimentary organization” (Roback and James 1978, 340); and to be “strongly organized

groups” (Panebianco 1988, 38). Nevertheless, some scholars deemphasize factional

organization, or at least organizational forms, and highlight factional activity. Building on Beller

and Belloni’s (1978) conclusion that “what is significant about factions ultimately is their

activity and its consequences – not their structural properties” (448, emphasis in original),

2

Similarly, and more recently, Rachel Blum (2020) describes factions as “miniature parties within parties” (13).

3

Françoise Boucek (2009) argues for recognizing that factionalism is “a dynamic process of

subgroup partitioning” (468, emphasis in original). Factional dynamics, for Boucek, are

“interactions between factions, host parties and voters” (Ibid.).

Of course, it is the purpose of factions, the reason they form and are organized in the

first place, that matters most. Rose (1964) notes that they “seek to further a broad range of

policies” (37); Key (1958) maintains that they have “a recognizable policy orientation” (320);

Zariski (1960) points to “a sense of common identity and common purpose” (33) and to the fact

that they “compete for the acquisition of influence over the principal institutions of intra-party

government, over the formulation of party policy, and over the selection of party leaders and

party nominees for public office” (29); and Polsby (1983) writes that they act “in pursuit of a

common interest” (65). Very often, the common purpose pursued by factions is thought to be

an ideological one. Indeed, ideological contestation is central to DiSalvo’s (2012) definition of

factions as party subunits that have “(1) the ideological consistency, (2) the organizational

capacity, and (3) the temporal durability to (4) undertake significant actions to shift a party’s

agenda priorities and reputation along the Left-Right spectrum” (5).

Studies of factions in American politics typically focus on political elites. For instance, in

his historical analysis of factions, DiSalvo maintains that factions are “networks that are

comprised of officeholders, organizational officers, and outside groups” (26). Noting that there

are, essentially, two types of factions – those that aim to preserve the status quo and those

that want to change it – he identifies at least twelve party factions that have existed (through

2007) since the end of the Civil War (11). The latest of these is the New Democrat faction

(1986-2007). For DiSalvo, these factions have played five roles in American political history:

4

they generate new ideas; influence the presidential nomination process; alter the power

dynamics in Congress; affect a president’s ability to govern; and impact state building (9-10).

Each of these, of course, is fundamentally the result of elite activity.

Members of Congress are the most common subject of studies of American factions.

Measures based on roll call votes (e.g., DW-NOMINATE scores) are often used to identify

differences between factions or to determine factional membership. For instance, using

NOMINATE scores as well as vote scores from Americans for Democratic Action and National

Journal, Medvic (2007) found that in the 106

th

Congress, New Democrats were significantly

more conservative than “traditional” Democrats but significantly less conservative than “Blue

Dog” Democrats. Those with membership in the New Democrat Coalition were also less liberal

on economic policy, but more liberal on foreign policy, than those not in the centrist coalition.

Noel (2016) uses both dimensions of the NOMINATE measure to show that, in 2016,

endorsements of presidential candidates considered to be “ideologues” rather than “regulars”

were more likely to come from Republican members of Congress who are more ideologically

extreme (first NOMINATE dimension) and are “outsiders” (second dimension; 179). Factional

distinctions didn’t appear as clearly among Democratic members of Congress (183). Clarke

(2020) uses NOMINATE scores for members of nine organized factions (five Republican and four

Democratic) in the House between 1995 and 2018 to demonstrate that factions “are eager to

distinguish themselves from their peers” (460). While Democratic factions “occupy distinct

regions of the ideological spectrum,” Republican factions “appear to cluster more heavily on

the right tail of the party’s distribution” (459). And Blum (2020) finds that Republican members

5

of three Tea Party-related House caucuses had more conservative NOMINATE scores than

“establishment” Republicans (85-6).

Additional analysis by Blum reveals differences between Tea Party and establishment

Republicans in terms of co-sponsorship of legislation (90-1) and the policy focus of press

releases (91-7). Clarke (2020) also utilizes press releases from faction leaders to identify

patterns that “closely mirror the branding capacity of each organization” (465). Thomsen

(2017) studied new members of the House and their decisions to join seven House caucuses

(four Republican and three Democratic). She found that “almost all incoming members joined

an ideological faction when they entered office” and that the moderate factions in both parties

attracted fewer members (749).

Candidates have also been the subject of recent work on factions. As part of the 2018

Primary Project at the Brookings Institution, Kamarck and Podkul (2018) used candidate self-

descriptions on campaign websites and a “four-step assignment logic” to assign congressional

candidates from the 2014, 2016, and 2018 election cycles to several factions in each party. For

Republicans, the factions were Business/Establishment, Conservative, Tea Party, and

Libertarian; for Democrats, they were Progressive, Establishment, and Moderate. The purpose

of such assignments was not only to gauge the level of candidate affiliation with each faction

but to determine the primary success rates of the factions. Kamarck and Podkul found that,

among non-incumbent candidates in both parties, establishment candidates performed better

than their more ideological counterparts.

Some studies look for factional activity among party leaders, operatives, activists, and

donors. Noel (2016), for example, determines whether party activists (i.e., those who had done

6

at least two of four political activities or had been a paid staffer, a candidate, or a party official)

fall into the “party regular” - or compromiser, pragmatist, insider or establishment - camp or

the ideologue faction (171). He then examines support for presidential candidates among

activists in 2016 based on the activists’ factional categorization (180 and 184). Masket (2020)

charts patterns of staffing in Democratic presidential campaigns in 2016 and 2020 and finds

“clear signs of persistent factionalism” (183). He also analyzed campaign donation patterns for

Democrats in gubernatorial elections between 2016 and 2017-2018 and the presidential

nomination process in 2016 and 2020. In both instances, Masket finds evidence of factional

behavior among establishment and progressive Democrats (164-81). Similarly, Clarke’s (2020)

examination of the donor base of members of Congress produced results that support the

hypothesis that “Joining a conservative (liberal) faction will lead to a more conservative (liberal)

donor base, conditional on the institutional strength of the faction” (455).

Most of Blum’s (2020) study of the Tea Party is based on interviews with, and

observations of, activists and organizations associated with the movement. In addition, she

surveys delegates to the 2013 convention of the Republican Party of Virginia and finds

significant differences in the attitudes of Tea Party and establishment Republicans. Several

studies focus was on delegates to the parties’ national conventions. Reiter (2004) posits three

types of factions (kaleidoscopic, consensus, and persistent) and analyzes convention roll call

votes for much of the history of the two parties. His results suggest a decided shift in the

middle of the twentieth century toward persistent, or ideological, factionalism (267). More

recently, Conger, et al. (2019) use the 2012 Convention Delegate Study to conduct “a

nonhierarchical cluster analysis of delegates’ group memberships, policy attitudes, and affect

7

toward party constituencies” (1382). Their analysis identifies three factions in each party and

determines the level of party support and pragmatism in party decision-making for all six

factions. Establishment Republicans are most supportive of the GOP and are pragmatic in their

views of party decision-making; Contemporary Conservatives and Libertarians are less

supportive of the GOP and demand ideological purity in the party (1398). In the Democratic

Party, factionalism was not as pronounced, perhaps because the 2012 nomination was not

contested, and all three factions were relatively supportive of the party. However, “All-Purpose

Liberals and Cultural Liberals are motivated more by policy demands than Centrists, and All-

Purpose Liberals are more purist than Centrists” (1399).

Few studies examine voters’ factional affiliations and those that do tend to distinguish

factions based on voting behavior. Carmines, Ensley, and Wagner (2016) calculate the

contribution of liberals, conservatives, moderates, libertarians, and populists to each party’s

presidential coalitions in 2012. In the Republican Party, conservatives constituted a majority

(54 percent) of the party’s coalition, followed by libertarians (28 percent; 392). Liberals made

up a plurality (37 percent) of the Democratic coalition, followed by moderates (23 percent) and

populists (20 percent; 393). Hansen, Hirano, and Snyder (2017) examine county-level primary

results for seven statewide offices in four states – Louisiana, Minnesota, North Dakota, and

Wisconsin – throughout much of the twentieth century. Each of their cases was a one-party

state during the period under consideration, which likely amplified the incentives for factional

activity. Their results indicate a clear connection between factional groupings of voters and

factional organizations that were active in each state. “In all four states,” they write, “the most

8

important work the factions did for voters was identification, attaching labels to candidates and

thereby classifying individuals as members of teams” (183).

Several recent studies attempt to explain support for Donald Trump within the

Republican Party. Rapaport, Reilly, and Stone (2020) utilize a YouGov panel survey that

interviewed Republican voters two weeks before the 2016 New Hampshire primary and again in

March of 2018. The authors find three groups of Republicans – those who indicated a

preference for Trump from the beginning of the process (“Always Trump”); those who

preferred a different Republican nominee but indicated they could support Trump in the

general election (“Maybe Trump”); and those who favored a different nominee and could not

support Trump in the general (“Never Trump;” 698-9). The analysis seeks to determine

factional influence on evaluations of Trump, the Republican Party, and the Tea Party, as well as

support for Trump’s border wall. The results indicate

that the factional structure within the Republican Party had shifted by early in Trump’s

presidency from one where the Trump nomination candidacy was substantially

orthogonal to support for the Republican Party, to one where support for the

Republican party was tied more closely not only to evaluations of Trump, but also to his

signature policy and to a potential rival faction defined by support for the Tea Party.

(704-5)

Like Rapaport, Reilly, and Snyder, Barber and Pope (2019) divide Republicans into three

groups based on their support for Trump in the primaries and in the general election. They

then determine the levels of symbolic, operational, and conceptual ideology of the three

groups. Republicans supportive of Trump in both the primaries and the general election were

found to have a high level of symbolic conservatism, a medium level of operational

conservatism, and a low level of conceptual conservatism. Those who supported Trump only

during the general election had high levels of symbolic and operational conservatism and a

9

medium level of conceptual conservatism. “Never Trump” Republicans were low in symbolic

and operational conservatism and had a medium level of conceptual conservatism (732).

In seeking to explain support for Donald Trump during the general election in 2016,

Ekins (2017) finds five unique types of Trump voters – Staunch Conservatives, Free Marketeers,

American Preservationists, Anti-Elites, and the Disengaged. Levels of support for the

Republican Party varies among these groups and “they hold vastly different views on

immigration, American identity, race, economics, and moral traditionalism” as well as “different

perceptions of justice in the political and economic systems” (30).

Drutman (2017) draws on the Voter Study Group’s 2016 VOTER Survey to identify

divisions within both parties based on primary vote choice. He finds more internal division

within the Republican Party than the Democratic Party. Nevertheless, Clinton and Sanders

Democrats were divided on trade, enthusiasm about America and its history, and pessimism

about people like them being “in decline.” “[T]o the extent that the Democratic Party is

divided,” writes Drutman, “these divisions are more about faith in the political system and

general disaffection than they are about issue positions” (18). For Republicans, “Trump’s

biggest enthusiasts within the party are Republicans who hold the most anti-immigrant and

anti-Muslim views, demonstrate the most racial resentment, and are most likely to view Social

Security and Medicare as important” (21).

The analysis that follows also seeks to understand factions among the voters within

each party. However, we rely on voter characteristics, including their demographic

characteristics, political and ideological self-identification, economic assessments, and issue

10

preferences rather than their vote choices to predict self-identified factional affiliation. In

doing so, we believe we offer a unique approach to the study of factions within the electorate.

Methods

The data presented in this paper come from three surveys conducted among 1,521

randomly selected registered voters in the state of Pennsylvania. Survey interviews were

conducted March 1 - 7 (269 Democrats, 236 Republicans, and 82 independents), June 7 - 13

(205 Democrats, 177 Republicans, and 62 independents), and August 9 - 15, 2021 (207

Democrats, 173 Republicans, and 66 independents). The voter samples were obtained from

Marketing Systems Group. All sampled respondents were notified by mail about the survey.

Interviews were completed over the phone and online depending on each respondent's

preference. Survey results were weighted (age, gender, education, geography, and party

registration) using an iterative weighting algorithm to reflect the known distribution of those

characteristics. Estimates for age, geography, and party registration are based on active voters

within the PA Department of State's voter registration data. Gender and education is estimated

using data from the November 2018 CPS Voter Registration Supplement.

3

In each survey, respondents were asked the following series of questions to identify the

party faction to which they most closely identify.

PARTY. Regardless of how you are registered in politics, as of today, do you think of

yourself as a Republican, a Democrat, or an Independent?

4

3

Data downloaded from IPUMS-CPS, University of Minnesota, www.ipums.org, accessed 12/31/2019.

4

The survey also included a question about actual voter registration since all voters in Pennsylvania choose a party

affiliation when they register to vote. Registration and party identification do not correspond perfectly in the state

and party identification, as asked in this question, tends to be a superior indicator of current partisanship in the

state (Yost, 2003).

11

Those who responded "independent" to the PARTY question were asked if they lean toward a

party and, if so, were asked the appropriate faction question. True independents were not

asked a faction question. The faction questions were:

RFact. The Republican Party includes several different wings or factions. In the

Republican Party, for example, there seems to be a faction that embraces Donald

Trump's brand of politics and another that is aligned with a more traditional brand of

Republican politics. Do you think of yourself as a Trump Republican, a traditional

Republican, or something else?

DFact. The Democratic Party includes several different wings or factions. In the

Democratic Party, for example, there seems to be a faction that embraces a consistently

progressive brand of politics and another that is aligned with a more pragmatic, centrist

brand of politics. Do you think of yourself as a progressive Democrat, a centrist

Democrat, or something else?

One might reasonably ask whether voters know enough about the factions within each

party to meaningfully affiliate with one of them. Given the amount of media discussion of

factions in recent years, we believe they can.

5

Furthermore, we believe the brief descriptions

of the factions used in our questions give voters enough information to make valid choices, and,

empirically, the consistency of the responses across all three of our surveys suggests that this

approach is reliable.

Results

Among the partisan identifiers included in these surveys, the factional breakdown for

Republicans is Trump Republican 47 percent, Traditional Republican 34 percent, and other

Republican 19 percent. The factional breakdown for Democrats is Centrist Democrat 44

percent, Progressive Democrat 39 percent, and other Democrat 18 percent. The distribution of

5

For just a sample of recent journalistic accounts of factions in the parties, see Bacon (2019), Haberman (2021),

and Olsen (2021).

12

factional choices were relatively consistent for respondents in both parties from survey period

to survey period (see Table 1).

Table 1. Distribution of Respondents by Party Faction and Survey Period

Trump R Traditional R Other R Other D Centrist D Progressive D

(n=303) (n=221) (n=120) (n=99) (n=239) (n=206)

Survey Period

August 95.4 (31.5) 63.4 (28.6) 41.2 (34.5) 32.7 (32.9) 63.6 (26.6) 59.4 (28.9)

June 96.2 (31.7) 57.3 (25.9) 33.3 (27.9) 30.8 (31.0) 67.9 (28.4) 66.7 (32.4)

March 111.6 (36.8) 100.9 (45.5) 44.9 (37.6) 35.9 (36.1) 107.4 (44.9) 79.6 (38.7)

Tables 2 and 3 display the distribution of respondents within each party faction by self-

described ideology, party affiliation, born-again Christian, gender, age, education, race, income,

and rural-urban classification.

13

Table 2. Distribution of Respondents by Party Faction and Selected Demographics, Republicans

Trump R

Traditional R Other R

(n=303)

(n=221) (n=120)

Ideology (%)

Extremely liberal

0.0 (0.0)

0.0 (0.0) 0.8 (0.8)

Liberal

8.3 (3.7)

4.5 (2.8) 1.2 (1.2)

Moderate

29.0 (12.9)

61.8 (38.5) 38.3 (39.0)

conservative

81.8 (36.4)

45.2 (28.2) 31.3 (31.9)

Extremely conservative

94.4 (42.0)

43.8 (27.3) 17.1 (17.4)

DK

11.4 (5.0)

5.2 (3.3) 9.5 (9.7)

Party Affiliation (%)

Strong Republican

193.6 (63.8)

90.1 (40.7) 36.5 (30.5)

Republican

47.2 (15.6)

68.5 (30.9) 18.5 (15.4)

Lean Republican

62.5 (20.6)

62.8 (28.4) 64.5 (54.0)

Independent

0.0 (0.0)

0.0 (0.0) 0.0 (0.0)

Lean Democrat

0.0 (0.0)

0.0 (0.0) 0.0 (0.0)

Democrat

0.0 (0.0)

0.0 (0.0) 0.0 (0.0)

Strong Democrat

0.0 (0.0)

0.0 (0.0) 0.0 (0.0)

DK

0.0 (0.0)

0.0 (0.0) 0.0 (0.0)

Identifies as born-again Christian (%)

Yes

111.1 (37.4)

66.1 (29.9) 28.0 (23.9)

No

178.0 (59.9)

149.5 (67.6) 83.5 (71.2)

DK

8.2 (2.8)

5.4 (2.4) 5.7 (4.9)

Gender (%)

Male

187.9 (62.1)

119.1 (54.1) 80.4 (68.2)

Female

114.8 (37.9)

101.2 (45.9) 37.5 (31.8)

Non-binary

0.0 (0.0)

0.0 (0.0) 0.0 (0.0)

Age (%)

Under 35

22.1 (7.3)

22.1 (10.0) 19.7 (16.5)

35 - 54

103.3 (34.1)

71.2 (32.1) 56.2 (47.0)

Over 55

177.8 (58.6)

128.2 (57.9) 43.6 (36.5)

Educational attainment (%)

HS or less

98.8 (32.6)

51.8 (23.4) 20.6 (17.2)

Some college

127.4 (42.0)

91.5 (41.3) 46.2 (38.7)

College degree

77.0 (25.4)

78.3 (35.3) 52.7 (44.1)

Racial group (%)

Non-white

25.6 (8.5)

16.8 (7.6) 17.1 (14.3)

Income (%)

Less than $35,000

57.4 (22.8)

38.9 (20.8) 8.0 (7.5)

$35 -75,000

90.9 (36.0)

74.3 (39.7) 34.7 (32.3)

Over $75,000

103.9 (41.2)

73.9 (39.5) 64.6 (60.2)

Urban rural classification (%)

Large central metro

24.0 (7.9)

28.7 (12.9) 11.8 (9.9)

Large fringe metro

76.1 (25.1)

55.5 (25.0) 40.1 (33.6)

Medium metro

103.5 (34.1)

70.6 (31.9) 38.3 (32.1)

Small metro

40.4 (13.3)

25.9 (11.7) 11.9 (9.9)

Micropolitan

36.5 (12.0)

29.0 (13.1) 11.2 (9.4)

Noncore

22.7 (7.5)

11.9 (5.4) 6.1 (5.1)

14

Table 3. Distribution of Respondents by Party Faction and Selected Demographics, Democrats

Other D

Centrist D

Progressive D

(n=99)

(n=239)

(n=206)

Ideology (%)

Extremely liberal

10.9 (14.0)

7.1 (4.3)

44.5 (31.5)

Liberal 14.3

(18.4)

49.5 (29.8)

38.2 (27.0)

Moderate

32.6 (41.8)

97.1 (58.5)

44.4 (31.4)

conservative

10.2 (13.1)

7.4 (4.5)

7.8 (5.5)

Extremely conservative

1.0 (1.3)

0.0 (0.0)

4.2 (3.0)

DK

8.9 (11.4)

4.8 (2.9)

2.3 (1.6)

Party Affiliation (%)

Strong Republican

0.0 (0.0)

0.0 (0.0)

0.0 (0.0)

Republican

0.0 (0.0)

0.0 (0.0)

0.0 (0.0)

Lean Republican

0.0 (0.0)

0.0 (0.0)

0.0 (0.0)

Independent

0.0 (0.0)

0.2 (0.1)

0.0 (0.0)

Lean Democrat

44.5 (44.8)

53.2 (22.3)

57.3 (27.9)

Democrat

17.3 (17.4)

45.4 (19.0)

33.9 (16.5)

Strong Democrat

37.6 (37.9)

140.1 (58.7)

114.4 (55.6)

DK

0.0 (0.0)

0.0 (0.0)

0.0 (0.0)

Identifies as born-again Christian (%)

Yes

17.0 (18.1)

31.9 (13.4)

21.5 (10.6)

No

77.1 (81.9)

201.2 (84.7)

180.8 (88.8)

DK

0.0 (0.0)

4.4 (1.9)

1.4 (0.7)

Gender (%)

Male

36.0 (36.2)

79.6 (33.3)

83.8 (40.9)

Female

63.4 (63.8)

159.3 (66.7)

120.4 (58.7)

Non-binary

0.0 (0.0)

0.0 (0.0)

0.9 (0.4)

Age (%)

Under 35

11.7 (11.7)

17.1 (7.1)

37.3 (18.1)

35 - 54

26.3 (26.5)

64.3 (26.9)

71.5

(34.8)

Over 55

61.5 (61.8)

157.6 (66.0)

96.9 (47.1)

Educational attainment (%)

HS or less

26.2 (26.3)

33.7 (14.1)

31.4 (15.3)

Some college

31.9 (32.1)

60.4 (25.3)

55.7 (27.1)

College degree

41.3 (41.5)

144.8 (60.6)

118.5 (57.6)

Racial group (%)

Non-white

19.1 (19.2)

25.0 (10.5)

51.7 (25.2)

Income (%)

Less than $35,000

31.8 (36.8)

33.8 (16.1)

39.7 (21.0)

$35 -75,000

27.3 (31.6)

57.8 (27.5)

59.8 (31.7)

Over $75,000

27.3 (31.6)

118.9 (56.5)

89.3 (47.3)

Urban rural classification (%)

Large central metro

30.4 (30.8)

56.3 (23.6)

77.7 (37.9)

Large fringe metro

26.6 (26.9)

105.9 (44.3)

57.8 (28.2)

Medium metro

30.2 (30.6)

56.9 (23.8)

42.3 (20.7)

Small metro

5.6 (5.7)

8.4 (3.5)

13.5 (6.6)

Micropolitan

4.6 (4.7)

6.4 (2.7)

11.5 (5.6)

Noncore

1.4 (1.4)

5.0 (2.1)

2.1 (1.0)

We analyze our data with two logistic regression models, one fit to self-identified

Democratic respondents and the other fit to self-identified Republican respondents. These

analyses began with models that incorporated demographic, political, economic, and issue

15

variables to predict the odds of belonging to either the Trump faction of the Republican Party

or the Progressive faction of the Democratic Party.

The full models for members of both parties included veteran status, religious

denomination, being a born-again Christian, age, educational attainment, employment status,

urban-rural classification,

6

labor union membership, race, gender, direction of the United

States, ratings of President Biden, political ideology, need for government action on climate

change, economic optimism, support for gun control, support for abortion rights, and racial

attitudes.

Economic optimism is calculated by summing the responses to evaluations of personal

finances compared to last year and evaluations of expected personal finances next year, and

dividing by two. For each item, those who responded “better off” scored a 1, those who

responded “same” scored 0.5, and those who responded “worse off” were scored 0.

The racial attitudes scale included three items (α = .69) from the FIRE battery (DeSante

and Smith 2020). Respondents were asked to report how much they agreed with each

statement: I am angry that racism exists; white people in the US have certain advantages

because of the color of their skin; and racial problems in the US are rare, isolated situations. A

strongly agree response was scored as 2 points while an agree response counted as 1 point for

all items except for the third question, which was reverse scored. The items were summed and

divided by six to create a score ranging from 0 – 1.

Items that were not significant in these original models were removed to arrive at the

final reported models. The entire set of variables included in these three surveys and a

6

Classification based on Ingram and Franco (2014).

16

comparison of the results for the full models to the final models reported in the next section is

included in the supplemental appendix.

Republican Factions

Table 4 presents logistic regression coefficients for membership in the Trump faction.

The odds of identifying as a member of the Trump faction are lower for those who do not

identify as born-again Christian, who are college graduates, and who do not identify as

“extremely” conservative. The largest coefficients associated with membership in the Trump

faction are for racial attitudes and economic optimism—those in the Trump faction are less

concerned about racism and are less optimistic about their economic circumstances, all else

being equal.

7

Table 4. Logistic Regression for Trump Faction, Republicans

Variable

Estimate

(Std. Error)

Born again Christian (No) -0.588

***

(-0.969, -0.207)

Some college education -0.214

(-0.693, 0.265)

College graduate -0.607

***

(-1.062, -0.153)

Racial attitudes -1.632

***

(-2.342, -0.922)

Economic Optimism -1.082

***

(-1.783, -0.382)

Conservative ideology Less Conservative or moderate -0.806

***

(-1.242, -0.369)

Conservative ideology Undefined -0.254

(-0.722, 0.213)

Constant 2.050

***

(1.451, 2.649)

Observations 593

Log Likelihood -365.1

Akaike Inf. Crit. 746.2

Area under the ROC curve 0.71

7

Economic optimism is calculated by summing the responses to evaluations of personal finances compared to last

year and evaluations of expected personal finances next year, and dividing by two. For each item, those who

responded “better off” scored a 1, those who responded “same” scored 0.5, and those who responded “worse off”

were scored 0.

17

Democratic Factions

Table 5 presents logistic regression coefficients for membership in the Progressive

faction. The odds of identifying as a member of the Progressive faction are higher for union

members, those less than 35 years of age, non-whites, those who “definitely” want more state

action on climate change, those who believe abortion should “always” be legal, those with

more economic optimism, and those who identify as extremely liberal.

Table 5. Logistic Regression for Progressive Faction, Democrats

Variable

Estimate

(Std. Error)

Member of labor union (No) -0.435

*

(-0.883, 0.013)

Age 35-54 -0.431

(-1.297, 0.436)

Age over 55 -1.045

**

(-1.859, -0.231)

Non-white 0.976

***

(0.389, 1.563)

Catholic 0.333

(-0.258, 0.924)

Other or unaffiliated religion 0.312

(-0.180, 0.803)

More state action on climate Yes probably -0.914

***

(-1.535, -0.293)

More state action on climate No probably not 0.523

(-0.809, 1.855)

More state action on climate No not at all -0.459

(-2.887, 1.969)

Abortion support sometimes legal -0.405

*

(-0.817, 0.008)

Abortion support never legal -0.125

(-1.282, 1.031)

Economic Optimism 0.796

*

(-0.137, 1.729)

Liberal ideology Less liberal or moderate -1.674

***

(-2.300, -1.047)

Liberal ideology Undefined -1.184

***

(-1.807, -0.560)

Constant 1.287

**

(0.051, 2.522)

Observations 551

Log Likelihood -307.852

Akaike Inf. Crit. 645.704

Area under the ROC Curve 0.737

18

Additional Analyses: Support for Democracy, Democracy in Practice, Christian Nationalism,

Operational Ideology

In addition to the items included in our logit models, some of our surveys included

scales that provide additional though limited data on characteristics that some have suggested

might drive membership in these factions. This section examines the factional differences on

four different scales. Details about the construction of these items can be found in the

supplemental appendix.

Support for Democracy in Principle and in Practice

We sought to determine respondents’ level of support for the principles of democracy

and their assessment of how democracy is working in practice. With respect to the principles of

democracy, we asked if all citizens deserve an equal say in how our government runs; if a leader

may sometimes need to break the rules to get things done; if there should be NO barriers to

voting in our country; if citizens should be allowed to say whatever they think even if their

views are unpopular; and if it is important to have established rights that protect defendants in

civil and criminal trials, including the presumption of innocence. On a ten-point scale, where

ten represents strong agreement with all five democratic principles and five represents

agreeing “somewhat” with each principle, the average score was 7.1. At the same time, most

voters in the state do not believe that American democracy is working as it should in practice.

To gauge how respondents think American democracy is working in practice, we asked if

citizens think the decisions of federal judges are fair and impartial; if the actions of the US

House and Senate represent the collective will of the American people; if elections in the

United States are free and fair; if the federal government is corrupt; and if the federal

19

government’s operations are open and transparent. The average score on the democracy-in-

practice questions was 2.4, which means that respondents disagreed with statements

describing a well-functioning democracy. Both Republicans and Democrats support democratic

principles (with scores of 6.6 and 7.5, respectively) and both are likely to disagree that

American democracy is working well (1.8 and 3.1, respectively). But, Republican scores on both

scales are significantly lower than Democratic scores.

The essential difference between the party factions is in their assessments of American

democracy in practice. Trump Republicans (average score of 1.1) are much less likely than

Traditional Republicans (2.4) to agree with all five statements that the American system is

working (see Figure 1). The bottom line is that, while all respondents tend to think that the

system isn’t working as we’d expect it to, Trump Republicans are especially likely to hold that

perspective. The differences among Democrats are not as stark; the differences in these groups’

ratings of democratic ideals and democracy in practice do not differ.

20

Figure 1. Democratic Principles and Practice Scale Scores by Party Factions

Christian Nationalism

Respondents were asked to report how much they agreed with four statements related

to Christian nationalist beliefs: the Founding Fathers intended the United States to be a

Christian nation; the Founding Fathers were evangelical Christians; the United States’ founding

documents are based on biblical principles; and America's power in the world is dependent on

its obedience to God. A strongly agree response was scored as 2 points while an agree response

counted as 1 point for all items. The items were summed and divided by four to create a score

ranging from 0 – 2.

21

Republicans (mean = 0.91) are more likely than Democrats (mean = 0.39) to believe in

Christian Nationalist ideals, but members of the Trump faction are much more likely than other

Republicans to believe that the United States is a Christian nation (see Figure 2). Trump

Republicans are more likely than Traditional Republicans and all Democratic factions to believe

in Christian Nationalist ideals. Democrats do not differ from each other on these beliefs.

Figure 2. Christian Nationalism Scale Scores by Party Factions

22

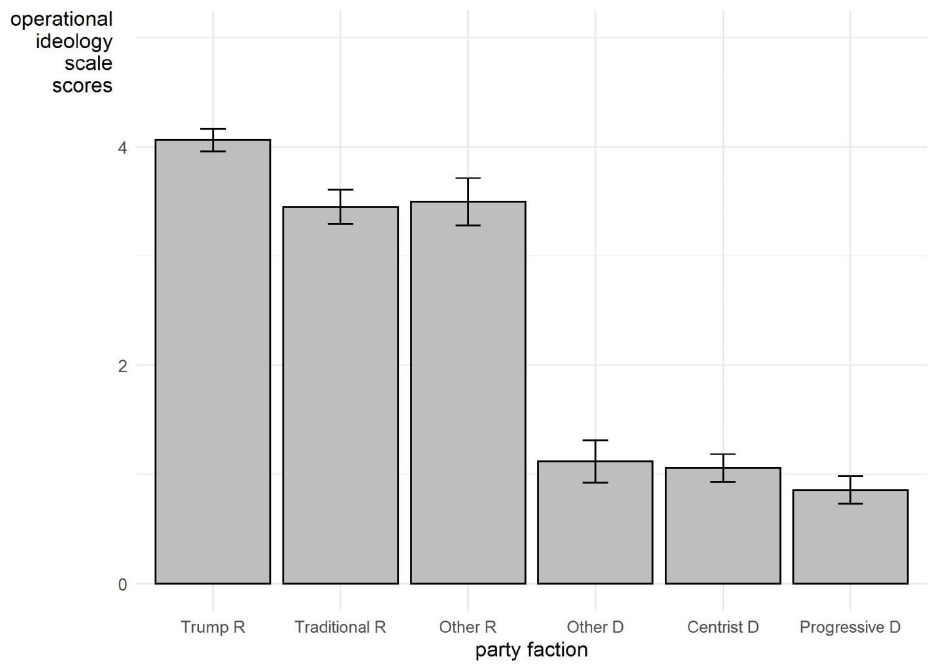

Operational Ideology

The operational ideology scale included five items that asked respondents to choose

which of two statements best reflected their personal views (see supplemental appendix for

question wording). Responses that reflected a conservative perspective were scored as 1 point

and the total scale score could range from 0 – 5. The operational ideology scale confirms the

findings from the logistic regression analysis that the Trump faction of the Republican Party is

the most conservative of all the partisan factions and that these individuals are more

conservative than other Republicans (see Figure 3). The ideological liberalism among

Democrats are not significantly different.

23

Figure 3. Operational Ideology Scale Scores by Party Factions

Discussion

This paper has explored voters’ sense of where they fit within their own parties using

designations that are commonly discussed in contemporary media coverage and political

discourse. Based on analyses of an assortment of data, we find that each party has at least

three discernable intra-party segments and that these segments are defined by a cluster of

ideological, demographic and policy attributes.

We should not be surprised that a system that fundamentally relies on just two major

parties has discernable factions within each. What we find noteworthy is that the factional

distinctions are strongly ideological within both parties, but that attributes beyond ideology

24

help to further differentiate the factions within each party. For Republicans, religion, economic

assessments, and attitudes about race produce the major points of division, while for

Democrats it is age, race, and policy preferences for government action on climate change and

abortion rights that amplify ideological differences.

Additional research is, of course, necessary to fully understand the factional affiliations

of the electorate. In addition to the items included in our logit models, we captured limited

data on characteristics that some have suggested might drive membership in these factions as

well. We found that some of these items, particularly support for Christian Nationalist ideals

among Republicans, would be worthy of additional work. Obviously, it would also be useful to

ask our faction affiliation questions to a national sample of voters. And, finally, we hope to

undertake further analyses of the characteristics of those voters in both parties who did not

affiliate with a faction and, instead, selected the “other” category.

One of the limitations of this work is that it is a product of the current political moment.

Undoubtedly, the labels given to these factions will change and the core groups will reconfigure

themselves in response to signals from political elites and the fusion of broader political and

cultural issues. This makes it particularly necessary to chart the feedback loops between elites

and voters that should continually reshape these self-defined factional affiliations.

25

Bibliography

Bacon, Perry, Jr. 2019. “The Six Wings of the Democratic Party.” FiveThirtyEight.com, March 11,

https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/the-six-wings-of-the-democratic-party/ (accessed October

20, 2021).

Barber, Michael and Jeremy C. Pope. 2019. “Conservatism in the Era of Trump.” Perspectives

on Politics 17: 719-36.

Beller, Dennis C. and Frank P. Belloni. 1978. “Party and Faction: Modes of Political

Competition.” In Frank P. Belloni and Dennis C. Beller, eds. Faction Politics: Political Parties and

Factionalism in Comparative Perspective. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-Clio Press.

Blum, Rachel M. 2020. How the Tea party Captured the GOP: Insurgent Factions in American

Politics. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Bolingbroke. 1997 [1738]. Bolingbroke: Political Writings. David Armitage, ed. New York:

Cambridge University Press.

Boucek, Françoise. 2009. “Rethinking Factionalism: Typologies, Intra-Party Dynamics and

Three Faces of Factionalism.” Party Politics 15: 455-85.

Carmines, Edward G., Michael J. Ensley, and Michael W. Wagner. 2016. “Ideological

Heterogeneity and the Rise of Donald Trump.” The Forum 14: 385-97.

Clarke, Andrew J. 2020. “Party Sub-Brands and American Party Factions.” American Journal of

Political Science 64: 452-70.

Conger, Kimberly H., Rosalyn Cooperman, Gregory Shufeldt, Geoffrey C. Layman, Kerem Ozan

Kalkan, John C. Green, and Richard Herrera. 2019. “Group Commitment Among U.S. Party

Factions: A Perspective from Democratic and Republican National Convention Delegates.”

American Politics Research 47: 1376-1408.

DeSante, Christopher D. and Candis Watts Smith. 2020. “Fear, Institutional Racism, and

Empathy: The Underlying Dimensions of Whites’ Racial Attitudes.” PS: Political Science &

Politics 53: 639-45.

DiSalvo, Daniel. 2012. Engines of Change: Party Factions in American Politics, 1868-2010. New

York: Oxford University Press.

Drutman, Lee. 2017. “Political Divisions in 2016 and Beyond: Tensions Between and Within the

Two Parties.” The Democracy Fund Voter Study Group,

https://www.voterstudygroup.org/publication/political-divisions-in-2016-and-beyond (last

accessed July 25, 2021).

26

Ekins, Emily. 2017. “The Five Types of Trump Voters: Who They Are and What They Believe.”

The Democracy Fund Voter Study Group, https://www.voterstudygroup.org/publication/the-

five-types-trump-voters (last accessed August 11, 2021).

Haberman, Maggie. 2021. “A survey of Republicans shows 5 factions have emerged after

Trump’s presidency.” The New York Times, March 12.

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/12/us/politics/republican-factions-.html (accessed October

20, 2021).

Hansen, John Mark, Shigeo Hirano, and James M. Snyder Jr. 2017. “Parties within Parties:

Parties, Factions, and Coordinated Politics, 1900-1980.” In Alan S. Gerber and Eric Schickler,

eds., Governing in a Polarized Age: Elections, Parties, and Political Representation in America.

New York: Cambridge University Press.

Ingram, DD and SJ Franco. 2014. “NCHS Urban-Rural Classification Scheme for Counties.” 166.

Vital Health Stat. Vol. 2. National Center for Health Statistics.

Kamarck, Elaine and Alexander R. Podkul. 2018. “The 2018 Primaries Project: What are the

internal divisions within each party?” The Brookings Institution,

https://www.brookings.edu/research/the-2018-primaries-project-what-are-the-internal-

divisions-within-each-party/ (last accessed September 20, 2021).

Key, V.O, Jr. 1949. Southern Politics in State and Nation. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Key, V.O., Jr. 1958. Politics, Parties, and Pressure Groups, 4

th

ed. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell

Company.

Masket, Seth. 2020. Learning from Loss: The Democrats, 2016-2020. New York: Cambridge

University Press.

Medvic, Stephen K. 2007. “Old Democrats in New Clothing? An Ideological Analysis of a

Democratic Party Faction.” Party Politics 13: 587-609.

Noel, Hans. 2016. “Ideological Factions in the Republican and Democratic Parties.” ANNALS of

the American Academy of Political and Social Science 667: 166-188.

Norris, Pippa. 1995. “May’s Law of Curvilinear Disparity Revisited: Leaders, Officers, Members

and Voters in British Political Parties.” Party Politics 1: 29-47.

Olsen, Henry. 2021. “The GOP has five factions now. They all see a different future for their

party.” The Washington Post, July 26.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2021/07/26/gop-has-five-factions-now-they-all-

see-different-future-their-party/ (accessed October 20, 2021).

27

Panebianco, Angelo. 1988. Political Parties: Organization & Power. New York: Cambridge

University Press.

Polsby, Nelson W. 1983. Consequences of Party Reform. New York: Oxford University Press.

Ranney, Austin and Willmoore Kendall. 1956. Democracy and the American Party System. New

York: Harcourt, Brace and Company.

Rapoport, Ronald B., Jack Reilly, and Walter J. Stone. 2020. “It’s Trump’s Party and I’ll Cry if I

Want To.” The Forum 17: 693-709.

Reiter, Howard L. 2004. “Factional Persistence Within Parties in the United States.” Party

Politics 10: 251-71.

Roback, Thomas H. and Judson L. James. 1978. “Party Factions in the United States.” In Frank P.

Belloni and Dennis C. Beller, eds. Faction Politics: Political Parties and Factionalism in

Comparative Perspective. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-Clio Press.

Rose, Richard. 1964. “Parties, Factions and Tendencies in Britain.” Political Studies 12: 33-46.

Rose, Richard. 1974. The Problem of Party Government. New York: Penguin Books.

Sartori, Giovanni. 1976. Parties and Party Systems: A Framework for Analysis, Volume 1. New

York: Cambridge University Press.

Thomsen, Danielle M. 2017. “Joining Patterns Across Party Factions in the US Congress.” The

Forum 15: 741-51.

Yost, B.A. 2003. “Disappearing Democrats: Rethinking Partisanship Within Pennsylvania’s

Electorate.” Commonwealth 12: 77 – 86.

Zariski, Raphael. 1960. “Party Factions and Comparative Politics: Some Preliminary

Observations.” Midwest Journal of Political Science 4: 27-51.