DECEMBER 2018

CHAPTER 2:

Aviation Activity Analysis and Forecast

Chapter 2 - Aviation Activity Analysis and Forecast

2-1

AVIATION ACTIVITY ANALYSIS AND FORECAST

Introduction

This chapter presents an air service market evaluation, an analysis of historical trends, and 20-year forecasts

of commercial and noncommercial aviation activity. Commercial aviation activity includes passenger and all-

cargo service. Noncommercial activity includes general aviation (GA) and military operations. The air service

market study estimates the “True Market” for Reno-Tahoe International Airport (RNO) by evaluating market

trends to explore the potential for air service expansion. The identification of market trends is the result of

analyzing current airline service, assessing airline performance, and comparing RNO with other airports that

provide air service within the region. The analysis of historical trends provides the context for the

development of the forecasts and informs model specifications and assumptions. The forecasts will serve as

the basis for subsequent analyses in the Master Plan, such as the assessment of facility requirements,

demand/capacity analysis, development of a 20-year capital improvement plan, and environmental impact

analysis. The details of the proposed forecasting approaches are described below. The resulting forecasts are

compared with the latest Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) Terminal Area Forecast (TAF) for RNO.

Air Service Market Evaluation

In support of the aviation forecast for RNO, an air service evaluation helped to develop the true market

estimate. The true market estimate gives RNO the most useful information about local passenger travel

patterns relative to commercial airline service. This air service market evaluation comprises a true market

estimate, market performance, and route performance studied for seven of the eight airlines serving

passengers at RNO, listed in Table 2-1 below. Volaris, as a non-domestic provider, is not required to report

commercial passenger activity through U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT).

The air service market evaluation section will briefly describe the methodology and the catchment area used

in the evaluation and will highlight the trends from the collected data through the year ending (YE) June 30,

2016. This section also addresses the service gaps and opportunities presented for RNO, concluding with the

overview of the opportunities for both incumbent and new airlines.

True Market Estimate

The primary objective of this evaluation was to develop

information on the travel patterns of passengers who

live in the area.

The analysis relied on a combination of Airline Reporting

Corporation (ARC) tickets (catchment area and online

travel agencies) and U.S. DOT data, calculating the true

market for the year end (YE) June 30, 2016. This data did

not capture tickets issued directly by airline websites,

and the survey sample consisted of 44,664 tickets, which

is consistent with industry survey standards.

Table 2-1: Airlines Serving Passengers at RNO

Airline

Abbreviation

Alaska

AS

Allegiant

G4

American

AA

Delta

DL

JetBlue

B6

Southwest

WN

United

UA

Volaris

Y4

Chapter 2 - Aviation Activity Analysis and Forecast

2-2

The catchment area is defined as the geographic

area where RNO can reasonably expect to draw

passenger traffic and is representative of the local

market. This is significant because it includes the

population of travelers who ideally should use RNO

based on the drive time. RNO’s primary catchment

area, shown in Figure 2-1, comprises 92 zip codes,

and had a 2016 population of 776,930.

The true market summary is calculated by looking at

the actual passenger use versus the total

passengers eligible to use the airport based on the

catchment area. RNO had a true market of

3,665,693 origin and destination (O&D) passengers,

shown in Table 2-2, which is 5,021 total passengers

daily each way (PDEW), meaning an estimated 279

PDEW use alternate airports.

The overall true market number represents 93

percent domestic travel and seven percent

international travel. RNO retained 94 percent of

total passengers, as shown in Figure 2-2, which

equaled 96 percent of domestic travel, and 75

percent of international retention.

Table 2-2: True Market Summary

Rank Origin Airport

YE 2Q 2016

PAX %

Domestic

1 RNO 3,281,368 96

2 Sacramento (SMF) 80,690 2

3 San Francisco (SFO)

63,133 2

Subtotal 3,425,192 100

International

1 RNO 180,662 75

2 SFO 50,109 21

3 SMF 9,730 4

Subtotal 240,501 100

Domestic and International

1 RNO 3,462,030 94

2 SFO 113,242 3

3 SMF 90,420 3

Total 3,665,693 100

Source: Mead & Hunt, Inc.; YE June 30, 2016

RNO

94%

SFO

3%

SMF

3%

Figure 2-2: True Market Summary

San Francisco International Airport (SFO) &

Sacramento International Airport (SMF)

Figure 2

-

1:

RNO Primary Catchment Area 2016

Chapter 2 - Aviation Activity Analysis and Forecast

2-3

Table 2-3 lists the top 25 domestic destinations. The top five domestic markets included McCarran

International Airport in Las Vegas (LAS), Los Angeles International Airport (LAX), Phoenix Sky Harbor

International Airport (PHX), Seattle-Tacoma International Airport (SEA), and San Diego International Airport

(SAN). Las Vegas was the top market with 435,015 annual passengers or 599 PDEW. Of note, the top 25

markets generate 65 percent of total air travel, and in the analysis, markets with nonstop service tended to

have a higher retention rate than markets without nonstop service.

Table 2-4 lists the top 15 international destinations. These markets were estimated at 240,501 annual

passengers or 329 PDEW. Within these markets, the top three were Los Cabos International Airport (SJD),

Cancun International Airport (CUN), and Vancouver International Airport (YVR). RNO retention rates were

much lower internationally, due in part to the service at RNO primarily being domestic, as well as RNO’s

relative proximity to San Francisco International Airport (SFO) and their significant international service.

Table 2-5 shows the top 50 true markets ranked by destination, illustrates RNO’s O&D passengers to each

destination, and lists RNO’s totals for domestic, international, and all markets within these top 50 including

the retention/diversion estimates for each.

Table 2-3: Top 25 Domestic Destinations

Rank Destination

Origin Airport %

Total

Pax

RNO SMF SFO

1 Las Vegas, NV LAS 99 0 0 435,015

2 Los Angeles, CA LAX 97 1 1 288,235

3 Phoenix, AZ PHX 97 2 1 193,021

4 Seattle-Tacoma, WA SEA 91 6 3 179,347

5 San Diego, CA SAN 99 0 1 160,718

6 Denver, CO DEN 99 1 1 147,844

7 Portland, OR PDX 95 3 1 105,088

8 New York JFK, NY JFK 93 2 4 98,179

9 Dallas-Fort Worth, TX DFW 93 4 3 72,435

10 Salt Lake City, UT SLC 96 3 2 69,243

11 Chicago O’Hare, IL ORD 95 2 4 64,998

12 San Jose, CA SJC 100 0 0 52,012

13 Boston, MA BOS 90 2 7 51,915

14 Minneapolis, MN MSP 96 2 2 47,933

15 Orange County, CA SNA 99 0 1 46,022

16 Orlando, FL MCO 94 4 2 45,255

17 Atlanta, GA ATL 94 4 2 42,560

18 Chicago Midway, IL MDW 99 0 0 42,056

19 Austin, TX AUS 97 1 2 38,094

20 Philadelphia, PA PHL 90 7 3 35,370

21 Baltimore, MD BWI 96 3 1 35,220

22 Washington Reagan, DC DCA 96 2 2 32,943

23 Detroit, MI DTW 97 2 1 32,418

24 Houston Bush, TX IAH 98 1 1 32,351

25 Newark, NJ EWR 89 2 9 30,399

Top 25 Domestic 96 2 2 2,378,670

Total Domestic 96 2 2 3,425,192

Source: Mead & Hunt, Inc.; YE June 30, 2016

Sacramento International Airport (SMF), San Francisco International Airport (SFO)

Chapter 2 - Aviation Activity Analysis and Forecast

2-4

Table 2-4: Top 15 International Destinations

Rank Destination

Origin Airport %

Total

Pax

RNO SFO SMF

1 San Jose del Cabo, Mexico SJD 94 4 2 13,952

2 Cancun, Mexico CUN 87 7 6 13,552

3 Vancouver, Canada YVR 90 6 3 11,244

4 Toronto, Canada YYZ 91 6 3 9,998

5 Mexico City, Mexico MEX 87 4 8 9,553

6 London Heathrow, UK LHR 78 19 3 8,482

7 Puerto Vallarta, Mexico PVR 91 7 3 7,708

8 Guadalajara, Mexico GDL 87 2 11 5,746

9 Manila, Philippines MNL 61 39 0 4,458

10 Calgary, Canada YYC 90 5 5 4,436

11 Montreal, Canada YUL 85 14 1 4,189

12 San Jose, Costa Rica SJO 77 14 9 3,873

13 Frankfurt, Germany FRA 73 26 1 3,868

14 Paris De Gaulle, France CDG 77 22 1 3,815

15 Dublin, Ireland DUB 70 28 2 3,437

Top 15 International 85 12 4 128,080

Total International 75 21 4 240,501

Source: Mead & Hunt, Inc.; YE June 30, 2016

Analysis of Current Airline Service (Market Performance)

This section highlights traffic and capacity trends, revenue and fare trends, and the O&D revenue market

share by airline. The section also highlights regional comparisons for the domestic market based on YE 2Q

2016.

As far as traffic and capacity trends, YE 2Q 2016 year-over-year capacity was up six percent and passengers

were up eight percent, as Figure 2-3 shows. These factors drove a one percentage point increase in load

factor (percent of seats sold), with capacity (total available seats) and passengers (traveling public) trending

positively. As far as revenue and fare trends, origin and destination revenue were increasing with fares

remaining stable, and RNO fares continue to be lower than the U.S. average, as shown in Figure 2-4.

Chapter 2 - Aviation Activity Analysis and Forecast

2-5

Table 2-5: Top 50 Domestic Destinations

Rank Destination

RNO O&D

Passengers

Retention %

Diverting Pax

Total PAX

SFO

SMF

1

Las Vegas, NV

LAS

432,402

99

1,900

713

435,015

2

Los Angeles, CA

LAX

280,401

97

3,590

4,243

288,235

3

Phoenix, AZ

PHX

187,274

97

2,612

3,135

193,021

4

Seattle

-

Tacoma, WA

SEA

161,860

90

5,106

12,381

179,347

5

San Diego, CA

SAN 159,121 99 925 672 160,718

6

Denver, CO

DEN

145,942

99

1,122

779

147,844

7

Portland, OR

PDX 99,595 95 1,630 3,863 105,088

8

New York JFK, NY

JFK

91,199

93

4,653

2,327

98,179

9

Dallas

-

Fort Worth, TX

DFW 67,031 93 2,252 3,152 72,435

10

Salt Lake City, UT

SLC

66,057

95

1,136

2,050

69,243

11

Chicago O’Hare, IL

ORD 61,384 94 2,409 1,205 64,998

12

San Jose, CA

SJC

52,012

100

0

0

52,012

13

Boston, MA

BOS

46,462

89

4,240

1,213

51,915

14

Minneapolis, MN

MSP 45,898 96 1,035 1,000 47,933

15

Orange County, CA

SNA

45,347

99

450

225

46,022

16

Orlando, FL

MCO 42,361 94 1,109 1,785 45,255

17

Atlanta, GA

ATL

40,071

94

783

1,705

42,560

18

Chicago Midway, IL

MDW 41,831 99 104 121 42,056

19

Austin, TX

AUS

36,915

97

646

533

38,094

20

Philadelphia, PA

PHL 31,542 89 1,268 2,559 35,370

21

Baltimore, MD

BWI

33,591

95

391

1,238

35,220

22

Washington Reagan, DC

DCA

31,672

96

694

576

32,943

23

Detroit, MI

DTW

31,420

97

426

571

32,418

24

Houston Bush, TX

IAH

31,714

98

182

455

32,351

25

Newark, NJ

EWR 26,522 87 3,064 813 30,399

26

Houston

Hobby

, TX

HOU

28,233

100

0

0

28,233

27

San Antonio, TX

SAT

27,681

99

222

74

27,977

28

Honolulu, HI

HNL

23,034

85

1,430

2,528

26,993

29

St. Louis, MO

STL

25,224

94

607

1,040

26,871

30

Nashville, TN

BNA

25,596

96

0

1,131

26,727

31

Tampa, FL

TPA

25,466

96

81

867

26,413

32

Kansas City, MO

MCI

25,608

98

160

337

26,105

33

Ontario, CA

ONT

24,624

99

88

184

24,896

34

San Francisco, CA

SFO

24,762

100

0

0

24,762

35

Fort

Lauderdale, FL

FLL

21,252

90

1,888

595

23,735

36

Washington

Dulles

, DC

IAD

21,352

93

806

708

22,866

37

Charlotte

-

Douglas, NC

CLT

22,102

97

218

464

22,784

38

Spokane, WA

GEG

22,243

98

69

379

22,691

39

Dallas

Love

, TX

DAL

22,397

100

47

59

22,503

40

New Orleans, LA

MSY

20,615

97

333

255

21,203

41

Albuquerque, NM

ABQ

20,029

97

139

417

20,585

42

Raleigh/Durham, NC

RDU

18,272

91

860

940

20,072

43

Kahului, HI

OGG

16,234

83

960

2,448

19,641

44

Burbank, CA

BUR

18,661

99

72

72

18,805

45

Indianapolis, IN

IND

17,577

97

422

89

18,087

46

Anchorage, AK

ANC

15,538

89

402

1,608

17,549

47

Boise, ID

BOI

17,502

100

0

0

17,502

48

Milwaukee, WI

MKE

16,597

96

409

273

17,279

49

Tucson, AZ

TUS

16,877

99

163

0

17,040

50

New York

LaGuardia

, NY

LGA

15,874

97

182

301

16,357

Total Domestic

3,281,368

96

63,133

80,690

3,425,192

Total International

180,662

75

50,109

9,730

240,501

Total All Markets

3,462,030

94

113,242

90,420

3,665,693

Source: Mead & Hunt, Inc.; YE June, 30 2016

Passengers daily each way (PDEW)

Chapter 2 - Aviation Activity Analysis and Forecast

2-6

Figure 2-3: Traffic and Capacity Trends

Source: Diio Mi T-100 Seats/Onboards 12-month non-directional, one-way rolling average; LF=RPMs/ASMs

Figure 2-4: Revenue and Fare Trends

Source: Diio Mi (total O&D passengers and revenue)

2,668,208

2,177,286

1,921,145

1,716,122

75%

81%

30

38

45

53

60

68

75

83

90

1,000,000

1,250,000

1,500,000

1,750,000

2,000,000

2,250,000

2,500,000

2,750,000

3,000,000

2012 2013 2014 2015 2016

Load factor %

Capacity / Passengers

Capacity Passengers Load Factor

$587.9M

$624.1M

$171

$188

$199

$200

$120

$140

$160

$180

$200

$220

$240

$260

$400

$450

$500

$550

$600

$650

Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2

2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016

O&D Average Fare ($)

O&D Revenue

Millions

RNO YE O&D Revenue RNO YE Avg Fare US YE Avg Fare

Chapter 2 - Aviation Activity Analysis and Forecast

2-7

Table 2-6 compares RNO with the other airports serving domestic markets in the region through YE June 30,

2016. RNO ranked 14

th

largest in the FAA West Region, which includes California, Arizona, Hawaii, and

Nevada, based on number of total passengers. RNO’s passenger and revenue growth outpaced the FAA West

Region. RNO’s fares increased one percent in contrast with fares for the region decreasing by four percent.

The decrease in RNO’s yield was similar to the regional average decline. This apparent contradiction is due to

passengers flying slightly longer distances during this period, and the fare being calculated as an average over

the distance traveled, or the fare divided by the miles traveled.

Table 2-6: Regional Comparisons – Domestic Only, YE June 30, 2016

Rank

Airport Passengers

Revenue

(000s)

Average

Fare

Average

Yield

YOY Change

Pax

Rev

Fare

Yield

1 Los Angeles, CA LAX 20,038,447 $3,700,815

$185 11.8¢ 10% 1% (8%) (8%)

2 Las Vegas, NV LAS 16,131,908 $2,262,677

$140 11.5¢ 9% 1% (7%) (8%)

3 San Francisco, CA SFO 14,192,653 $2,939,966

$207 13.0¢ 6% 3% (3%) (1%)

4 Phoenix, AZ PHX 11,738,283 $1,918,896

$163 13.8¢ 7% 4% (3%) (3%)

5 San Diego, CA SAN

8,605,799 $1,481,202

$172 12.9¢ 5% 2% (3%) (4%)

6 Honolulu, HI HNL

5,327,405 $1,264,101

$237 11.5¢ 1% 3% 2% 1%

7 Oakland, CA OAK

4,960,227 $703,289

$142 14.3¢ 7% 8% 1% (3%)

8 Orange County, CA

SNA

4,658,694 $781,818

$168 15.7¢ 8% 3% (4%) (4%)

9 San Jose, CA SJC 4,474,656 $730,609

$163 15.4¢ 6% 5% (1%) (2%)

10 Sacramento, CA SMF

4,301,125 $734,181

$171 15.4¢ 6% 5% (1%) (3%)

11 Kahului, HI OGG

2,444,215 $566,981

$232 12.0¢ 5% 5% 0% (2%)

12 Burbank, CA BUR

1,953,575 $270,457

$138 20.4¢ 2% 3% 1% 0%

13 Ontario, CA ONT

1,947,692 $325,178

$167 16.5¢ 1% 1% 0% (2%)

14 Reno, NV RNO

1,572,969 $271,505

$173 15.6¢ 7% 8% 1% (3%)

15 Tucson, AZ TUS 1,401,825 $267,431

$191 16.3¢ (2%) (1%) 0% (1%)

16 Lihue, HI LIH 1,292,657 $294,079

$227 12.6¢ 3% 3% 0% (1%)

17 Kona, HI KOA

1,216,952 $286,008

$235 12.9¢ 4% 3% 0% (4%)

18 Long Beach, CA LGB 1,177,654 $134,287

$114 13.3¢ (3%) (9%) (7%) (2%)

19 Palm Springs, CA PSP 723,044 $141,923

$196 15.8¢ 0% (1%) (1%) (1%)

20 Phoenix Mesa, AZ AZA 663,302 $54,114

$82 8.0¢ 5% (3%) (8%) (8%)

21 Hilo/Hawaii, HI ITO 602,981 $76,121

$126 19.0¢ 1% 2% 0% (3%)

22 Fresno, CA FAT 567,801 $120,385

$212 18.0¢ 1% 2% 1% 4%

23 Santa Barbara, CA SBA 277,457 $67,899

$245 19.0¢ (3%) (1%) 1% 0%

24 Monterey, CA MRY

177,080 $34,789

$196 18.7¢ 6% 0% (6%) (2%)

25 Santa Rosa, CA STS 138,960 $19,037

$137 24.3¢ 23% 22% (1%) (1%)

Total/Average

111,654,107

$19,712,744

$177

13.0¢

6%

2%

(4%)

(4%)

Source: Diio Mi – YE June 30, 2016

Chapter 2 - Aviation Activity Analysis and Forecast

2-8

Regional Air Service Comparison (Route Performance)

The route performance section covers the load factor trends, revenue per available seat mile (RASM)

performance, and RASM trends. Overall, thirteen markets had declining load factors for the second quarter

of 2016 compared to the second quarter of 2015, with only six markets showing improvement. RNO load

factors for the same period declined one percentage point driven by a seven percent increase in capacity.

RASM trends for Alaska Airlines, Allegiant Airlines, American Airlines, Delta, and JetBlue Airlines show mixed

results for the second quarter, with six markets improving and five markets having decreasing RASMs. The

most significant changes were positive on Alaska Airlines route to San Jose (SJC) and Delta Airlines route to

Minneapolis (MSP) increasing 17-19 percent year over year (YOY). For Southwest and United Airlines, overall

second quarter RASMs were down one percent YOY; however, results were mixed with seven markets

improving and three markets having decreasing RASMs.

Air Service Assessment (Service Gaps and Opportunities)

During the evaluation, gaps in commercial service emerged that present strong opportunities for RNO. This

section of the report documents the findings of the data collection and analysis in terms of existing airlines,

nonstop service, and air service opportunities for both incumbent and new airlines. As Figure 2-5 shows, as

of 2016 RNO has eight airlines (the seven domestic carriers and international carrier Volaris) providing

service to 22 destinations.

Figure 2-5: RNO Airline Service Destination Map

Chapter 2 - Aviation Activity Analysis and Forecast

2-9

Table 2-7 ranks RNO’s top 25 destinations and PDEWs by destination, as well as the average flights and seats

per week, and the market load factor those numbers represent. Several items are worth noting. Airlines as of

YE June 30, 2016, include Alaska, Allegiant, American, Delta, JetBlue, Southwest, United and Volaris. Potential

new entrants for domestic air service include two growing airlines: Frontier, which previously stopped service

in August 2007, and Spirit. Large local markets without nonstop service include: Logan International Airport

(BOS) with 71 PDEW, Minneapolis-St. Paul International Airport (MSP) to year-round with 66 PDEW, Orlando

International Airport (MCO) with 62 PDEW, Austin-Bergstrom International Airport (AUS) with 52 PDEW,

Philadelphia International Airport (PHL) with 49 PDEW, Baltimore-Washington International Airport (BWI)

with 48 PDEW, Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport (DCA) with 45 PDEW, Detroit Metropolitan

Airport (DTW) with 44 PDEW, and Newark Liberty International Airport (EWR) with 42 PDEW. United Airlines

George Bush Intercontinental Airport (IAH) is a market in need of additional frequency due to high load

factors and strong unit revenue. In March 2017, RNO offered nonstop service to 16 of the top 25 destinations

with 395 weekly departures on 48,510 weekly seats.

Table 2-7: Top 25 Destinations by PDEW

Rank Destination PDEW

Average / Week

Market LF

Flights Seats

1 Las Vegas, NV LAS 595.9 69 10,123 76.1

2 Los Angeles, CA LAX 394.8 56 5,397 70.0

3 Phoenix, AZ PHX 264.4 35 4,786 78.2

4 Seattle-Tacoma, WA SEA 245.7 27 2,052 81.2

5 San Diego, CA SAN 220.2 13 1,859 74.2

6

Denver, CO DEN 202.5 28 3,877 86.3

7 Portland, OR PDX 144.0 20 1,520 79.3

8 New York JFK, NY JFK 134.5 7 1,050 86.0

9 Dallas-Fort Worth, TX DFW 99.2 14 2,240 82.1

10 Salt Lake City, UT SLC 94.9 26 3,627 81.9

11 Chicago O’Hare, IL ORD 89.0 7 1,120 80.7

12 San Jose, CA SJC 71.2 13 988 64.4

13 Boston, MA BOS 71.1 0 0 N/A

14 Minneapolis, MN MSP 65.7 0 0 92.4

15 Orange County, CA SNA 63.0 7 532 80.4

16 Orlando, FL MCO 62.0 0 0 N/A

17 Atlanta, GA ATL 58.3 1 180 N/A

18 Chicago Midway, IL MDW 57.6 4 668 92.0

19 Austin, TX AUS 52.2 0 0 N/A

20 Philadelphia, PA PHL 48.5 0 0 N/A

21 Baltimore, MD BWI 48.2 0 0 N/A

22 Washington Reagan, DC DCA 45.1 0 0 N/A

23 Detroit, MI DTW 44.4 0 0 N/A

24 Houston Bush, TX IAH 44.3 2 152 94.3

25 Newark, NJ EWR 41.6 0 0 N/A

Source: Mead & Hunt, Inc. YE June 30, 2016; March 2017 schedules and YE October 2016 LFs

Chapter 2 - Aviation Activity Analysis and Forecast

2-10

RNO has a relatively high retention rate and supports the catchment area population of more than 750,000.

Based on the air service market trends derived from this study, March 2017 capacity is expected to be up 19

percent YOY, which indicates RNO is experiencing significant growth mainly driven by increases from all

incumbent airlines except American and Volaris Airlines. Carriers that have increased their schedule may be

cautious about further expansion if the scheduled capacity is unfilled and will likely want to see that extra

capacity sold and used at reasonable levels before expanding again in the near term.

RNO has service to all its top 10 markets including to John F. Kennedy International Airport (JFK) in New York,

which began in June 2015. While New York nonstop service exists, United Airlines’ service to EWR or

Washington Dulles International Airport (IAD) are options given the large regional local market sizes with no

nonstop service. While DCA may be the preferred airport for Washington D.C. area, IAD or BWI would offer

significantly more potential international connections.

Additional nonstop service to eastern markets such as BOS, DTW, MCO and PHL should be explored along

with continuing to meet with airlines not serving RNO as of the time of this study, such as Frontier Airlines

and Spirit Airlines. Eastern destinations could be more challenging to attract and retain service, as they

require a greater cost investment by the airlines due to the longer distances being flown. These costs make

the economics of the routes more challenging to sustain.

Incumbent Airline Opportunities

Overall, when including domestic and international travelers, Southwest Airlines was the largest carrier at

RNO at YE June 30, 2016. Southwest Airlines carried about 1.5 million passengers, ahead of American Airlines

with 735,000 passengers, United Airlines with 415,000, Alaska Airlines with 396,000, Delta with 247,000,

JetBlue with 82,000, and Volaris and Allegiant each carrying approximately 35,000 annual onboard

passengers to and from RNO. Load factors for all airlines averaged 81 percent with United Airlines and

JetBlue averaging 86 percent, and Volaris averaging the lowest at 73 percent. Overall industry load factors in

the mid-80s still leaves some room for passenger growth on the current schedule, especially for Alaska

Airlines and Southwest Airlines with their percent of seats sold just under 80 percent.

Trends point to Alaska Airlines’ overall March capacity being up 17 percent YOY. However, the merger with

Virgin-America may offer opportunities for additional expansion beyond John Wayne Airport (SNA) in Orange

County to markets such as SFO and SAN as they work through their combined networks. With Allegiant’s

year-round service to just LAS at the time of this study, opportunities for new markets such as AUS exist. AUS

is a top 20 market without nonstop service. Due to the nonstop service already provided from RNO to both

PHX and SAN, service to Phoenix-Mesa Gateway Airport (AZA) or SAN would present challenges. For example,

Allegiant may be reluctant to serve another market with direct competition even though they serve LAS in

conjunction with Southwest Airlines today.

Chapter 2 - Aviation Activity Analysis and Forecast

2-11

Expanding Delta’s presence beyond Salt Lake City International Airport (SLC) is another viable option to

explore as both Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport (ATL) and MSP have had less than daily

service and both are a top 20 market without daily nonstop service. Even though United Airline’s capacity is

trending upward 16 percent, they are running high load factors in the RNO market. As a result, additional

frequencies to IAH or nonstops to additional eastern markets like Chicago O’Hare International Airport

(ORD), IAD or EWR could be considered. Southwest has added the greatest number of seats YOY in the RNO

market expanding into Dallas Love Field (DAL) and Oakland International Airport (OAK); therefore, Southwest

may want to give the new service time to ramp up before expanding further. With the addition of Long

Beach Airport (LGB), JetBlue has doubled its capacity from the RNO market and may also want to give the

service time to prove itself. Volaris flies to Guadalajara International Airport (GDL) three times per week and

has generated load factors above 80 percent in certain months. Volaris could look to expand to additional

destinations such as CUN or Mexico City International Airport (MEX).

New Airline Opportunities

Several airlines do not currently operate at RNO and are potential operators of new service. These include

Frontier Airlines, Spirit Airlines, and some low cost international carriers such as WOW Air that continue to

grow and expand their footprint across the U.S. To attract these potential airlines, RNO would need to

experience either local market growth and/or target a hub that could provide connections beyond the target

city to be economically viable. Canadian carriers like WestJet are an example of this scenario.

Other airline opportunities may arise, such as pro-rate flying on regional airlines like SkyWest Airlines, or

scheduled charter service on evolving carriers like Air Florida, Falcon Air Express, Omni Air, Miami Air

International, or Sun Country. Previous attempts at attracting international service to London were

successful by working with key stakeholders though the Customs and Border Protection (CBP) staffing issues

will need to be examined. Targeting tour operators such as Thomas Cook, Apple Vacations, or Vacation

Express can be another way to expand international service.

Air Service Market Evaluation Summary

With more than 775,000 people in the RNO primary catchment area, a true market of 3.67 million O & D

travelers translates to 93 percent domestic travel, and seven percent, international. RNO retains 94 percent

within the top 25 markets, which generate 65 percent of total air travel.

In terms of market performance, based on YE June 30, 2016, capacity, passengers, and load factor improved

YOY and were trending positively. RNO fares were lower than the U.S. average and were stable while O&D

airline revenue was increasing, with Southwest Airlines and American Airlines leading in revenue share at

RNO. RNO passenger and revenue growth outpaced other airports within the West region. This appears to

contradict the reported results in the bullets below, but it is important to keep in mind that RASMs are the

metric used to analyze route performance. RASMs combine the average fare and load factor, which leads to

the seeming contradiction.

Chapter 2 - Aviation Activity Analysis and Forecast

2-12

In terms of route performance, the bullets below summarize the results for the airlines serving passengers at

RNO:

Alaska (AS): RNO had above average RASM at SNA/Portland International Airport (PDX)/San Jose

International Airport (SJC)/SEA, but below average at Boise Airport (BOI) – SJC, although the RASM

experienced strong YOY improvement.

Allegiant (G4): RNO had above average RASM at LAS.

American (AA): RNO had below average RASM at ORD/Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport

(DFW)/PHX, and average at LAX.

Delta (DL): RNO had below average RASM at SLC – MSP, but operated seasonally on Saturdays only and

ran high load factors.

JetBlue (B6): RNO had below average RASM at JFK, where service began June 2015. LGB was not

analyzed due to service starting September 2016.

Southwest (WN): RNO had average RASM at LAS/LAX/SAN, and below average at Chicago Midway

International Airport (MDW)/PHX/Denver International Airport (DEN)/OAK. Service to OAK began June

2016.

United (UA): RNO had above average RASM at IAH/SFO, average at LAX, and below average at DEN.

Appendix F provides additional information regarding route performance for each of the airlines currently

serving RNO.

Chapter 2 - Aviation Activity Analysis and Forecast

2-13

Commercial Passenger Traffic

This section discusses the historical trends in commercial passenger traffic at RNO and presents forecasts for

the 20-year period ending in 2036. The analysis of historical trends sets the context for model specifications

and assumptions used in forecast development.

Historical Enplanement Trends

Enplanement History Since 1990

In 2016 RNO posted its second consecutive year of growth in commercial passenger traffic, seeing 6.4

percent in growth of total passengers (enplaned and deplaned). Passenger enplanements increased 6.2

percent to 1.82 million, surpassing the previous year’s increase of 3.9 percent, as shown in Figure 2-6. These

increases ended seven consecutive years of decreases that began in 2008, when the U.S. economy entered a

recession. The increases also halted an overall downward trend since 1997 when enplanements reached an

all-time peak level of 3.34 million at the height of Reno Air’s hub operations at RNO.

Figure 2-6: RNO’s Enplanement Trends since 1990

Sources: U.S. BTS T-100 data for 1990-2008, RTAA records for 2009-2016, and Unison Consulting, Inc.

Chapter 2 - Aviation Activity Analysis and Forecast

2-14

From 1990 through 1997, RNO experienced an unprecedented growth in enplanements with the expansion

of low-fare service by Reno Air and Southwest Airlines amid a long-running U.S. economic expansion.

Southwest Airlines began service in 1990 and rapidly ramped up its operations, gaining the largest airline

share of RNO enplanements by 1996.

Reno Air, a start-up low-fare carrier, began service in 1992 with RNO as its home base and main network hub.

Reno Air expanded operations quickly and competed closely with Southwest Airlines, besting Southwest in

1997 for the largest market share at RNO.

A pivotal change occurred in 1993 when Reno Air entered an alliance with American Airlines to handle

American’s regional traffic. In 1999, American Airlines acquired Reno Air, which flew its last flight in August

that year. At the time of the acquisition, American intended to use Reno Air to expand its network, but plans

changed following the 2001 U.S. economic recession and terrorist attacks. Financial pressures led American

to dispose of Reno Air’s entire fleet to reduce capacity and dismantle Reno Air’s network including the RNO

hub. These actions downgraded RNO to a secondary airport in American’s route system.

During the same period, RNO, along with other U.S. airports, faced weak air travel demand from the

economic recession, security concerns after the terrorist attacks, and a decrease in short-haul air travel due

to the new stringent security measures. After peaking in 1997, enplanements at RNO decreased in five

consecutive years through 2002.

In 2003, the trend reversed and annual enplanements at RNO increased in three consecutive years. During

the same period, jet fuel prices began to rise, and the U.S. economy began to slow again, ultimately entering

another recession in 2008-2009, which has come to be known as the Great Recession. This was the longest

and deepest post-World War II recession.

Airlines responded by cutting domestic seat capacity, cutting service on less profitable routes, increasing load

factors, transferring routes between mainline and regional service, retiring old aircraft, changing pricing

structures, and implementing various cost-cutting measures. Mounting financial pressures led to airline

bankruptcies and a consolidation wave that has left the industry with only four major airlines controlling 80

percent of the U.S. market. The Great Recession dampened air travel demand in leisure markets like Reno

more than in other markets with large business centers. Airline capacity cuts, which continued long after the

end of the Great Recession, hurt smaller airports like RNO more than larger airports.

As a result of these factors, passenger traffic at RNO decreased to 1.65 million enplanements in 2014, the

lowest level in 26 years. The growth in the past two years increased enplanements by 10.3 percent, to 1.82

million in 2016, about the same as the level in 1992, the second full year of Southwest’s operations at RNO

and the year Reno Air started service. The enplanement level in 2016 was slightly more than one half of the

all-time peak level in 1997 and more than two-thirds of the highest level reached just before the Great

Recession.

The growth in RNO enplanements in the past two years can be attributed to two positive trends: the regional

economic recovery is finally gaining momentum, and airlines are beginning to add capacity. At RNO, all

airlines increased scheduled seats over the two-year period, with Alaska Airlines adding the largest number

of seats. RNO also gained two new airlines, JetBlue and Volaris, and JetBlue added the second largest number

of seats.

Chapter 2 - Aviation Activity Analysis and Forecast

2-15

Comparison of RNO and U.S. Enplanement Trends since 2002

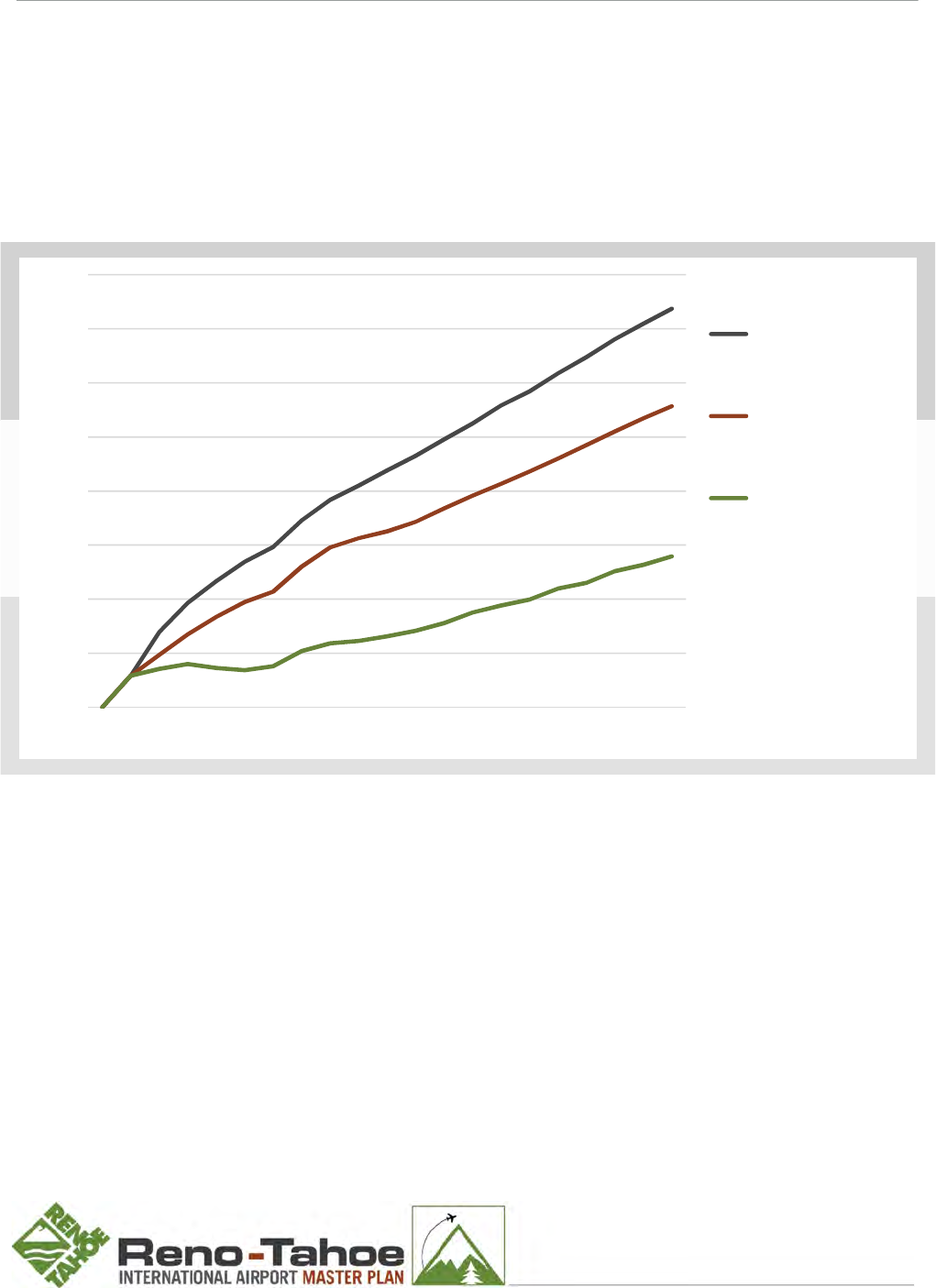

Figure 2-7 compares the enplanement growth trends at RNO with the national trends since 2002. Through

2005, RNO was outperforming the nation in enplanement growth. By 2005, RNO’s enplanements had grown

22 percent from 2002, while U.S. total enplanements had grown only 19 percent. In 2006, RNO began to fall

behind as enplanements began to decrease, while total U.S. enplanements continued to increase through

2007.

In 2008-2009, the U.S. economy entered the Great Recession, and enplanements decreased nationwide. RNO

suffered proportionally larger decreases in enplanements. After the Recession ended in 2009, U.S. total

enplanements grew steadily each year and surpassed their pre-recession level in 2014. By 2016, U.S. total

enplanements had grown to 138 percent of their level in 2002.

RNO experienced the opposite as enplanements continued to decrease through 2014. RNO reversed the

trend in 2015 and has tracked national growth trends since then. Despite growing more than 10 percent over

the past two years, however, RNO’s enplanements remained well below pre-recession levels. In 2016, RNO

enplanements were still only at 83 percent of the 2002 level. As Figure 2-8 shows, RNO’s share of total U.S.

enplanements decreased from 0.3 percent before the recession to 0.2 percent after the recession.

Figure 2-7: RNO and U.S. Enplanements – Cumulative Growth Since 2002

Sources: RTAA records for RNO enplanements, U.S. Bureau of Transportation Statistics T-100 Market Data for U.S. total

enplanements, and Unison Consulting, Inc. The data labels show cumulative growth through 2016.

Chapter 2 - Aviation Activity Analysis and Forecast

2-16

Figure 2-8: RNO’s Share (%) of U.S. Total Enplanements

Sources: RTAA records for RNO enplanements, U.S. Bureau of Transportation Statistics T-100 Market Data for U.S. total

enplanements, and Unison Consulting, Inc.

The following factors explain the divergence of RNO’s enplanement growth trends from the national

enplanement growth trends:

Divergent economic trends: Compared to the U.S. economy, the regional economy declined more sharply

during the 2008-2009 recession and continued to decline through 2013, four years into the national

economic recovery and expansion, as shown in Figure 2-9.

Divergent employment trends: The nonfarm employment level in the Reno-Carson City-Fernley

combined statistical area (Reno CSA) fell more sharply during the recession and began to recover a year

later than the U.S. nonfarm employment level, as shown in Figure 2-10.

Divergent trends in available airline seats: U.S. airlines cut system-wide domestic seat capacity during the

recession and kept capacity flat through 2014. RNO suffered deeper cuts, which continued through 2014,

as shown in Figure 2-11.

Chapter 2 - Aviation Activity Analysis and Forecast

2-17

Figure 2-9: Comparison of the Reno CSA and U.S. Overall Economic Growth Trends

GDP – Gross Domestic Product

Sources: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Moody’s Analytics, and Unison Consulting, Inc.

Figure 2-10: Comparison of the Reno CSA and U.S. Employment Growth Trends

Sources: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Moody’s Analytics, and Unison Consulting, Inc.

Chapter 2 - Aviation Activity Analysis and Forecast

2-18

Figure 2-11: Comparison of Trends in Available Seats at RNO and Nationwide

(U.S. Carriers, Domestic Segment Only)

Sources: U.S. Bureau of Transportation Statistics T-100 Domestic Segment Data on Available Seats and Unison Consulting, Inc.

Monthly Enplanement Trends

A seasonal pattern in enplanements is typical at most airports as it is at RNO, as shown in Figure 2-12. During

the year, enplanements at RNO typically reach their highest level in July, the peak of summer leisure travel.

They typically reach their lowest level in November, before the winter ski season, except in 2015 when

enplanements were lowest in February and in 2016 when enplanements were lowest in January.

Figure 2-12: Monthly Enplanement Trends at RNO

Sources: RTAA records and Unison Consulting, Inc.

110

120

130

140

150

160

170

180

Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec

Enplanements (Thousand)

2012 2013 2014 2015 2016

Chapter 2 - Aviation Activity Analysis and Forecast

2-19

Enplanement Trends by Airline from 2009

Figure 2-13 shows RNO’s enplanement trends by airline since 2009, the year during which the Great

Recession ended in June. RNO’s enplanements continued to decrease until the past two years and, by 2016,

were still down 3.1 percent from 2009. Southwest Airlines, RNO’s largest passenger carrier, was responsible

for much of the decrease, especially in short haul flights. United and Delta also posted decreases from 2009

to 2016. The increases in enplanements by American, Alaska, and other airlines, especially newcomer

JetBlue, offset some of the decreases in enplanements by Southwest, United, and Delta. In 2014, total

enplanements reached their lowest level for the period, which was also the lowest level in 26 years. Since

2014, total enplanements have been increasing, with all the airlines posting net increases between 2014 and

2016.

Southwest Airlines remains the largest passenger carrier at RNO, with a 43 percent share of total

enplanements in 2016, as shown in Figure 2-14. However, this share decreased from 54 percent in 2009,

which allowed other airlines to increase market shares. American Airlines, including US Airways’

enplanements, increased its enplanement share from 16 to 21 percent; Alaska Airlines, from 8 to 12 percent;

and new entrants JetBlue, Volaris, and Allegiant gained a combined share of 6 percent in 2016. During the

same period, United's market share decreased slightly from 13 to 12 percent, and Delta maintained its

market share of 7 percent.

America West merged with US Airways prior to 2009, and US Airways merged with American Airlines in 2013.

The charts in Figure 2-14 and Figure 2-15 show the combined enplanements of US Airways and American

Airlines, which grew in share from 2009 to 2016.

Chapter 2 - Aviation Activity Analysis and Forecast

2-20

Figure 2-13: RNO Enplanements by Airline

Sources: RTAA records and Unison Consulting, Inc.

1. The bottom chart showing enplanement growth trends for individual airlines does not show the “Others” category. Subtotal

enplanements by this category of airlines quadrupled from 2009 to 2016 because of the entry of JetBlue, Volaris, and Allegiant into

RNO.

2. The numbers for American Airlines include the combined traffic of American Airlines, US Airways, and their regional affiliates,

before and after the merger. American Airlines and US Airways merged in 2013, and the US Airways brand was retired in 2015.

3. The numbers for United Airlines include Continental Airlines’ traffic prior to their merger in 2011.

Chapter 2 - Aviation Activity Analysis and Forecast

2-21

Figure 2-14: Airline Shares of RNO Enplanements

Sources: RTAA records and Unison Consulting, Inc.

The recent wave of consolidation prompted airlines to renew efforts to streamline operations and optimize

networks, cut overall system capacity, and shift their focus away from protecting market share to achieving

profitability. In the process, they moved flights from smaller markets like RNO to larger markets where they

could gain scale and network economies and make higher profits.

In addition, three specific developments likely contributed to the decrease in Southwest Airlines’ activity at

RNO: the repeal of the Wright Amendment, Southwest Airlines’ acquisition of AirTran Airways, and the

conditions for the U.S. Department of Justice’s approval of the American Airlines-US Airways merger. The

repeal of the Wright Amendment lifted restrictions at Southwest Airlines’ home base, Dallas Love Field (DAL),

on one-stop through service effective October 2007 and on nonstop service effective October 2014, allowing

Southwest to increase flights at DAL. The acquisition of AirTran Airways in May 2013 opened international

markets for Southwest. With the merger of American Airlines and US Airways, Southwest gained access to

gates at DCA, La Guardia Airport (LGA), and BOS that American Airlines and US Airways had to give up as a

condition to the approval of the merger. Due to a finite number of aircraft, Southwest’s expansion at these

airports was made possible by decreasing flights at other airports, including RNO.

54%

43%

16%

21%

13%

12%

8%

12%

7%

7%

1%

6%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016

Percentage

Others

Delta

Alaska

United

American

Southwest

Chapter 2 - Aviation Activity Analysis and Forecast

2-22

Composition of Passenger Traffic at RNO

RNO’s passenger traffic consists largely of O&D traffic, as shown in Figure 2-15, which was estimated to

account for 90 percent of total enplanements in 2015. In 1997, at the height of Reno Air’s hub operations at

RNO, O&D traffic accounted for about 76 percent. RNO’s passenger traffic also consisted entirely of domestic

passengers, until Volaris began the RNO-GDL service in December 2014. By 2016, Volaris enplaned more than

20,000 passengers, capturing a 1 percent share.

Figure 2-15: Enplanements – O&D and Connecting Traffic Shares

Sources: RTAA records, U.S. Bureau of Transportation Statistics T-100 Market Data, U.S. Bureau of Transportation Statistics DB1B

O&D Market Data accessed through Data Base Products, Inc., and Unison Consulting, Inc.

Top 20 O&D Markets

Figure 2-16 shows RNO’s top 20 O&D airport markets. Las Vegas McCarran International Airport tops the list

with a 13.4 percent share, followed by LAX with 8.2 percent, and Phoenix Sky Harbor International Airport

with 5.3 percent.

76%

90%

24%

10%

1997 2015

0.0

0.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

3.5

4.0

1997 1999 2001 2003 2005 2007 2009 2011 2013 2015

Enplanements (Million)

Connecting

O&D

Chapter 2 - Aviation Activity Analysis and Forecast

2-23

Figure 2-16: RNO’s Top 20 O&D Airport Markets

Airport Code

Share of RNO O&D

Passengers

Las Vegas McCarran International Airport, NV LAS 13.4%

Los Angeles International Airport, CA LAX 8.2%

Phoenix Sky Harbor International, AZ PHX 5.3%

Seattle/Tacoma International Airport, WA SEA 4.7%

San Diego International Airport, CA SAN 4.7%

Denver International Airport, CO DEN 4.2%

Portland International Airport, OR PDX 3.1%

John F Kennedy International Airport, NY

1

JFK 2.7%

Salt Lake City International Airport, UT SLC 2.1%

Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport, TX DFW 1.9%

Chicago O' Hare International Airport, IL ORD 1.8%

Orange County John Wayne Airport, CA SNA 1.7%

San José International Airport, CA SJC 1.6%

Minneapolis-St Paul International Airport, MN MSP 1.5%

Orlando International Airport, FL MCO 1.4%

Boston Logan International Airport, MA BOS 1.4%

Atlanta Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport, GA ATL 1.3%

Chicago Midway International Airport, IL MDW 1.2%

Austin-Bergstrom International Airport, TX AUS 1.2%

Baltimore/Washington International Airport, MD BWI 1.0%

Sources: U.S. Bureau of Transportation Statistics DB1B O&D Market Data accessed through Data Base Products, Inc., Bing Maps,

and Unison Consulting, Inc.

1. RNO O&D passengers using Newark Liberty International Airport (EWR) and La Guardia Airport (LGA) combined account for

another 1.3%.

Chapter 2 - Aviation Activity Analysis and Forecast

2-24

Historical Trends in Scheduled Passenger Airline Service

The following figures show the trends in scheduled passenger airline service at RNO:

Scheduled seats from 2004 (Figure 2-17)

Scheduled seats by major carriers from 2004 (Figure 2-18)

Scheduled flights from 2004 (Figure 2-19)

Fleet mix and average seats per flight in 2004 and 2016 (Figure 2-20)

Number of nonstop destinations served from RNO from 2004 (Figure 2-21)

Scheduled service by airline from 2012 (Figure 2-22)

Seats provide the best measure for airline service capacity. Since 2004, scheduled seats at RNO have

decreased by about 40 percent, as shown in Figure 2-17. Southwest Airlines, RNO’s largest passenger carrier,

was responsible for much of the decrease, but all the other major carriers also contributed. Unfavorable

economic conditions, airline industry consolidation, and airline capacity rationalization explain the overall

decrease in airline industry capacity, which fell disproportionately on RNO and other small hub airports.

Southwest experienced other milestones such as regulatory changes, acquisition of AirTran Airways, and

requisite access to more gates at other airports as a condition of the 2013 merger. These milestones allowed

Southwest to expand elsewhere, made possible by cutting capacity at RNO and other airports, due to the

limited number of aircraft available for use and the lack of crew to fly them. Additionally, heightened

economic uncertainty during the Great Recession and the subsequent slow recovery made it unwise for

Southwest (and other airlines) to incur large capital costs by buying new aircraft. In fact, one of the strategies

that was key to airlines’ survival during the years of the recession was to retire inefficient aircraft, defer

deliveries of aircraft on order, and hold off on new aircraft orders.

Figure 2-19 shows how mergers have affected scheduled seats by major airlines at RNO. Of all the mergers

since 2004, the America West-US Airways merger in 2005 and the Continental-United merger in 2010 clearly

caused decreases in the combined seats of those airlines at RNO.

Chapter 2 - Aviation Activity Analysis and Forecast

2-25

Figure 2-17: Trends in Scheduled Seats at RNO from 2004

Sources: Diio Mi Schedule data from RTAA and Unison Consulting, Inc.

Figure 2-18: Trends in Scheduled Seats of Major Airlines at RNO from 2004

Sources: Diio Mi Schedule data from RTAA and Unison Consulting, Inc.

Chapter 2 - Aviation Activity Analysis and Forecast

2-26

Scheduled flights have decreased as much as scheduled seats, as Figure 2-19 shows.

Figure 2-19: Trends in Scheduled Flights at RNO from 2004

Sources: Diio Mi Schedule data from RTAA and Unison Consulting, Inc.

The mix of aircraft serving RNO has also changed, as shown in Figure 2-20. The proportion of narrow body jet

aircraft decreased from 81 percent in 2004 to 63 percent in 2016, as the proportion of smaller aircraft,

namely regional jet and turboprop aircraft, increased from 19 percent in 2004 to 37 percent in 2016. As a

result, the average number of seats on each flight decreased slightly from 120 in 2004 to 118 in 2016. Within

the narrow-body jet fleet, however, airlines have been adding seats to existing aircraft, so that the average

seat capacity on each narrow-body jet aircraft has increased. Within the regional jet and turboprop fleet, the

smaller 50-seat aircraft have been replaced with larger aircraft, so that the average seat capacity in this

equipment group has also increased.

Chapter 2 - Aviation Activity Analysis and Forecast

2-27

Figure 2-20: Fleet Mix and Average Seats per Flight

Sources: Diio Mi Schedule data from RTAA and Unison Consulting, Inc.

The number of airport destinations served nonstop from RNO, shown in Figure 2-21, increased to 22 in 2016

from a low of 17 in 2010-2014. In 2004-2009, the number of airport destinations had reached a high of 23.

Figure 2-21: Number of Airport Destinations with Nonstop Flights from RNO

Sources: Diio Mi Schedule data from RTAA and Unison Consulting, Inc.

Chapter 2 - Aviation Activity Analysis and Forecast

2-28

Figure 2-22 shows the trends in scheduled service originating from RNO by airline over the last five years.

Southwest still accounts for the most number of seats and flights offered at RNO, although its average daily

scheduled seats decreased from 3,800 in 2012 to 2,800 in 2016, and its average daily flights decreased from

28 in 2012 to 20 in 2016. American Airlines follows in second position, increasing its average daily scheduled

seats from 1,000 in 2012 to 1,200 in 2016 while maintaining 11 flights per day on average. For the entire

airport, scheduled seats decreased from 6,400 per day in 2012 to 6,300 per day in 2016 and scheduled flights

decreased from 56 per day in 2012 to 54 per day in 2016, on average.

Figure 2-22: Trends in Scheduled Outbound Service by Airline from RNO from 2012

Sources: OAG Schedules Analyzer and Unison Consulting, Inc.

Chapter 2 - Aviation Activity Analysis and Forecast

2-29

Landings and Landed Weight

The trends in number of aircraft landings and landed weight by commercial passenger airlines reflect the

same declining trend through 2014 and the beginning of recovery in 2015 and 2016 observed by

enplanements, shown in Figure 2-23. Southwest Airlines accounts for the largest shares of landings and

landed weight, and American Airlines accounts for the second largest shares.

Figure 2-23: Trends in Landings and Landed Weight by Airline from RNO from 2012

Sources: OAG Schedules Analyzer and Unison Consulting, Inc.

Chapter 2 - Aviation Activity Analysis and Forecast

2-30

Commercial Passenger Aircraft Operations by Month and Time of Day

Figure 2-24 shows the monthly distribution of commercial passenger aircraft operations at RNO, based on

airline flight schedules for 2015-2017. The peak month is July, with an average of 9.3 percent of annual

operations taking place during this month. Figure 2-25 shows the hourly distribution of operations during the

average day in July, also based on airline flight schedules for 2015-2017. Arrivals and departures are

distributed differently throughout the day. The peak hour for aircraft departures is from 6 to 6:59 a.m.; 13.1

percent of daily departures take place during this hour. The peak hour for aircraft arrivals is from 11 to 11:59

p.m.; nine percent of daily arrivals take place during this hour. The peak hour for total aircraft operations

(departures and arrivals) is from 9 to 9:59 a.m.; or 7.5 percent of total daily operations take place during this

hour.

Figure 2-24: Monthly Distribution of Commercial Passenger Aircraft Operations

Sources: OAG Schedules Analyzer and Unison Consulting, Inc. The distribution is based on scheduled flights for 2015-2017.

Jul, 9.3%

6%

7%

8%

9%

10%

11%

12%

Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec

Share of Annual Operations

Chapter 2 - Aviation Activity Analysis and Forecast

2-31

Figure 2-25: Peak Month Average Day Distribution of Commercial Passenger Aircraft Operations

Sources: OAG Schedules Analyzer and Unison Consulting, Inc. The distributions are based on scheduled flights for July in 2015-2017.

Forecast Commercial Passenger Traffic

Methodology

The approach to forecasting commercial passenger aviation activity uses the following modeling techniques:

Hybrid forecasting framework

Multivariate time series regression analysis

Scenario forecasting

Forecast risk analysis using Monte Carlo simulation

Arrivals, 9.0%

Departures,

13.1%

Total Operations,

7.5%

0%

2%

4%

6%

8%

10%

12%

14%

Percentage of Operations

Time of Day

Arrivals Departures Total Operations

Chapter 2 - Aviation Activity Analysis and Forecast

2-32

The models use data from various sources, including the following:

Reno-Tahoe Airport Authority

Airline flight schedules

Airline websites and annual reports

Online airline fleet data sources

U.S. Bureau of Transportation Statistics databases and publications

Federal Aviation Administration databases and publications

U.S. Bureau of Census

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis

Moody’s Analytics

2015-2019 Northern Nevada Regional Growth Study prepared by the Economic Planning Indicator

Committee (EPIC).

The hybrid forecasting framework incorporates both supply and demand considerations. The forecast for the

first year is supply-driven, based primarily on published airline flight schedules for up to one year ahead.

Airlines plan their schedules based on passenger bookings, and the schedules therefore reflect near-term

market demand. The schedules also establish the baseline data on commercial aircraft operations and fleet

mix.

Beyond the first year, forecasts are demand-driven. Market demand factors drive growth in enplanements.

Forecast enplanement levels, in turn, determine the number of aircraft operations and corresponding landed

weight, along with assumptions regarding trends in boarding load factors and changes in aircraft fleet mix.

Multivariate time series regression analysis links enplanement growth to trends in market demand drivers.

This type of analysis combines elements of multiple regression and time series regression methods. This

econometric modeling technique provides the ability to incorporate many explanatory variables, quantify the

contribution of each explanatory variable to aviation activity trends, and account for time trends and any

serial correlation in time series data. The model estimation process using the least squares method is

designed to minimize forecast errors. Using two-stage least squares (TSLS) estimation method also addresses

the potential endogeneity of real passenger yield, one of the key drivers of passenger traffic.

The regression model specification for RNO passenger traffic is based on the underlying theory of consumer

demand and the dynamics of traffic growth at RNO. The regression coefficients that measure contributions of

market demand drivers (explanatory variables) to RNO enplanement growth trends are estimated using

historical annual and quarterly data from 1990, controlling for the effects of any structural changes in air

service and extra-ordinary events like the 2001 terrorist attacks. The estimated regression coefficients are

then used to generate forecasts of RNO enplanements based on projected trends for the model explanatory

variables.

Chapter 2 - Aviation Activity Analysis and Forecast

2-33

Since American Airlines ended the former Reno Air’s hub operations at RNO in 2001, connecting traffic has

decreased, increasing the O&D traffic share to 90 percent of total enplanements. For the regression model of

passenger traffic, O&D enplanements serve as the dependent variable, effectively controlling for the

significant fluctuation in enplanement levels due to connecting traffic.

The key explanatory variables (independent variables) in the regression model of passenger traffic are as

follows:

Economic trends: The regression model includes two economic indicators: the real per capita gross

domestic product (GDP) for the Reno-Carson City-Fernley, NV, CSA to indicate regional economic trends,

and the U.S. unemployment rate to indicate national economic trends.

1

The regression coefficient

estimates for these variables confirm their expected effects on RNO enplanement trends. Holding all

other factors constant, growth in regional real per capita GDP and decreases in U.S. unemployment rate,

indicating overall national economic growth, promote growth in RNO enplanements. Conversely,

economic downturns and increases in unemployment decrease RNO enplanements.

Airline yield trends: Consumer demand is inversely related to price. Demand increases when price

decreases and decreases when price increases, if all other things are equal. The regression model

estimation results confirm this relationship strongly applies to RNO passenger traffic. The regression

model uses the average real passenger yield at RNO as the indicator for the price of air travel. Passenger

yield, which is the average revenue per passenger mile, is a better price indicator than the average fare,

because it controls for trip distance.

2

Figures 2-26, 2-27, 2-28, and 2-29 show the projections of the most likely trends in the key demand drivers:

Regional economic trends: The regional real per capita GDP decreased sharply during the last recession.

Altogether it decreased for eight years straight through 2013. The regional economy began to turn

around in 2014 and has since grown steadily along with the national economy, albeit at the same slow

pace. According to economic forecasts by Moody’s Analytics, the regional real per capita GDP will

continue growing at an average pace of 1.3 percent annually over the 20-year forecast period, 2017-

2036. Moody’s Analytics’ economic forecasts anticipate some cyclicality in the medium term, showing a

mild acceleration of growth in the regional economy over the next three years—consistent with the

forecast in EPIC’s Northern Nevada Regional Growth Study for 2015-2019—before growth slows again.

The long-term forecast, however, does not anticipate any deep downturns in the regional economy like

the one experienced during the Great Recession.

1

These two economic indicators proved to be better predictors of RNO enplanement trends than the other economic

indicators tested: aggregate and per capita personal income in the Reno-Carson City-Fernley, NV, CSA; nonfarm

employment in the Reno-Carson City-Fernley, NV, CSA; and U.S. nonfarm employment. Population at the CSA level was

also tested as an explanatory variable.

2

Airline yield may not be totally independent of passenger traffic levels. The use of TSLS corrects for the potential

endogeneity of airline yield. With TSLS, the model estimation is done in two stages. In the first stage, airline yield is

regressed on the following independent variables: nonfarm employment in the Reno CSA, real per capita GDP in the

Reno CSA, U.S. unemployment rate, real jet fuel price, the variables that control for the changes in air service by Reno

Air and Southwest airlines, and the variables that capture post-9/11 structural changes.

Chapter 2 - Aviation Activity Analysis and Forecast

2-34

National economic trends: Reflecting improving national economic conditions, the U.S. unemployment

rate has been declining steadily from a peak level of 9.6 percent reached in 2010. The 4.9 percent U.S.

unemployment rate in 2016 reflects a national economy near full employment. According to Moody’s

Analytics’ economic forecast, the U.S. unemployment rate will continue to decline for another three

years before rising again, but it will not rise to levels reached during the Great Recession. It will rise to 5.4

percent in 2022 and then taper at 4.9 percent.

Airline yield trends: The average real passenger yield at RNO had been on a long-term decreasing trend

through 2004. Then it began to increase in 2005 and continued increasing through 2014—Southwest

Airlines was cutting capacity at RNO during this period. In the past two years, the average real passenger

yield at RNO has been decreasing again. For the master plan forecast, the average real passenger yield at

RNO is set to follow FAA’s projected trend for U.S. mainline air carriers. It will remain essentially flat over

the first 10 years of the forecast period and then decrease very slightly over the following 10 years. See

footnote 2 on the previous page.

Figure 2-26: Historical and Projected Trends in Reno CSA Real Per Capita GDP

Sources: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Moody’s Analytics, and Unison Consulting, Inc.

Figure 2-27: Historical and Projected Trends in U.S. Unemployment Rate

Sources: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Moody’s Analytics, and Unison Consulting, Inc.

43,739

45,325

58,149

0

10,000

20,000

30,000

40,000

50,000

60,000

70,000

1990

1992

1994

1996

1998

2000

2002

2004

2006

2008

2010

2012

2014

2016

2018

2020

2022

2024

2026

2028

2030

2032

2034

2036

Historical Forecast

Real Per Capita GDP in the Reno-Carson City-Fernley, NV, CSA (2009 $)

5.6%

4.9%

4.9%

0%

2%

4%

6%

8%

10%

12%

1990

1993

1995

1997

1999

2001

2003

2005

2007

2009

2011

2013

2015

2017

2019

2021

2023

2025

2027

2029

2031

2033

2035

Historical Forecast

U.S. Unemployment Rate

Chapter 2 - Aviation Activity Analysis and Forecast

2-35

Figure 2-28: Historical and Projected Trends in RNO Real Passenger Yield

Sources: U.S. Bureau of Transportation Statistics DB1B, Federal Aviation Administration, and Unison Consulting, Inc.

Figure 2-29: Historical and Projected Annual Change in Key Market Demand Drivers

Sources: U.S. Bureau of Transportation Statistics DB1B for historical data on RNO real passenger yield; Federal Aviation Administration for projected

trend in real passenger yield; U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis of historical real per capita GDP in the Reno-Carson City-Fernley, NV, CSA; U.S. Bureau

of Labor Statistics for historical U.S. unemployment rate; Moody’s Analytics for projected real per capita GDP in the Reno-Carson City-Fernley, NV,

CSA; and projected U.S. unemployment rate, and Unison Consulting, Inc., for analysis.

0.24

0.15

0.13

0.00

0.05

0.10

0.15

0.20

0.25

1990

1992

1994

1996

1998

2000

2002

2004

2006

2008

2010

2012

2014

2016

2018

2020

2022

2024

2026

2028

2030

2032

2034

2036

Historical Forecast

RNO Real Passenger Yield (2009 $)

-2.4%

-0.6%

1.0%

1.0%

4.9%

4.9%

-15%

-10%

-5%

0%

5%

10%

15%

Historical Projected

Change in RNO real passenger yield

Change in real per capita GDP in the Reno-Carson City-Fernley, NV, CSA

U.S. unemployment rate

Chapter 2 - Aviation Activity Analysis and Forecast

2-36

Since 1990, RNO has gone through significant changes in airline service, particularly from Reno Air, which

operated at RNO from 1992 to 1999, and from Southwest Airlines, which has operated at RNO since 1990. To

account for the effects of these changes, the regression model includes the following variables:

Number of nonstop destinations served by Reno Air, as a percentage of total nonstop destinations served

from RNO.

Number of nonstop destinations served by Southwest Airlines, as a percentage of total nonstop

destinations served from RNO.

The regression model also includes an explanatory variable to account for the adverse effects of the terrorist

attacks in 2001 and the subsequent structural changes in the travel market and the airline industry. The

terrorist attacks had profound effects on the airline industry and airports, including RNO. They caused a

sharp decrease in enplanements following the attacks in 2001 and the following year. They prompted more

stringent security screening processes at airports that caused lasting changes in the demand for air travel.

They set in motion various other structural changes in the airline industry. To curb financial losses following

the terrorist attacks, American Airlines disposed of the Reno Air fleet it acquired in 1999, dismantled Reno

Air’s network, and closed the RNO connecting hub.

After 2001, aviation fuel prices began to rise, reaching record levels by 2008. The rise in fuel costs aggravated

financial pressures in the airline industry, prompting airlines to change business models, cut costs, cut

capacity, and consolidate through mergers. These are changes that affect RNO to this day. Preliminary

specifications of the regression model included aviation fuel prices as an explanatory variable. It was

excluded in the final model because its coefficient was statistically insignificant. Fuel prices as an explanatory

variable also did not add to the model’s overall predictive power, likely because the effects are already

captured by the other explanatory variables, such as the economic indicators, airline passenger yield, and the

variable accounting for structural changes since the terrorist attacks in 2001.

The regression model was estimated twice, using annual data and quarterly data. This approach resulted in

similar measures for the contribution of each of the market drivers to RNO passenger traffic trends,

producing similar forecasts for RNO passenger traffic growth. The measured contributions (coefficient

estimates) of all the explanatory variables are consistent with theory and expectations. They are all

statistically significant. That means they show strong evidence that they really influence passenger traffic

trends. The regression model has an adjusted R-squared of 0.96, meaning that the model and all its

explanatory variables explain 96 percent of variations in RNO O&D enplanements, which account for 90

percent of total enplanements.

The model coefficient estimates measuring the contributions of market drivers to growth in RNO’s

enplanements, along with projections of trends in the key market demand drivers, produce the forecast

growth in enplanements beyond the first year of the forecast period. Recognizing uncertainty in the future

trends of key market drivers, alternative forecasts were developed using Monte Carlo simulation. A

comprehensive approach to forecast risk analysis Monte Carlo simulation uses probability distributions and

random sampling techniques for assigning future values to the key explanatory variables of the regression

model. The simulation, involving 5,000 iterations, produced a wide range of possible scenarios for future

enplanement growth and corresponding percentile rankings. Percentiles provide an indication of the

likelihood of each of the forecast scenarios.

Chapter 2 - Aviation Activity Analysis and Forecast

2-37

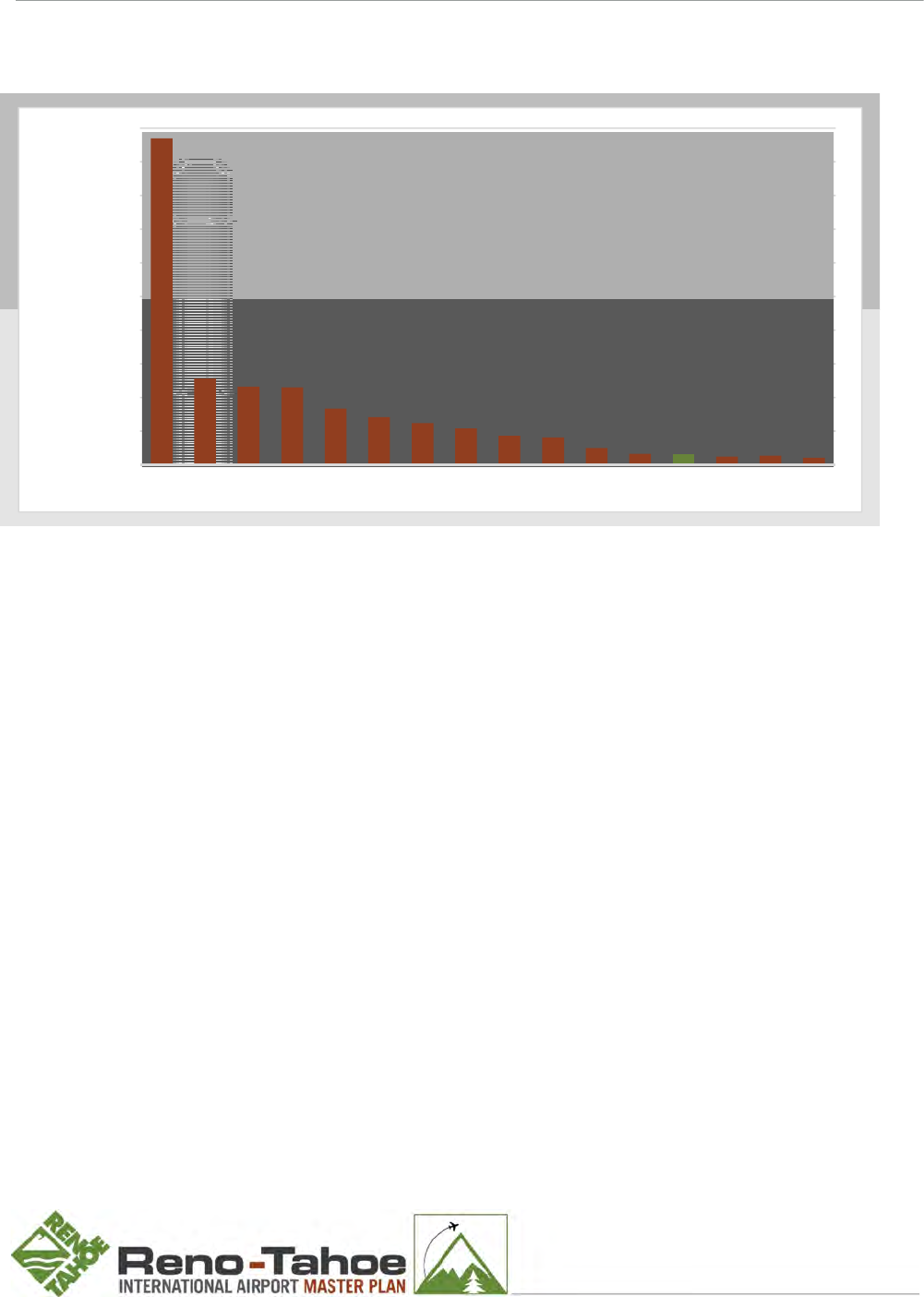

Figure 2-30 shows the range of forecast enplanements, which include select Monte Carlo simulation results

and the recommended Master Plan forecast. Figure 2-31 also shows a high growth forecast, a low growth

forecast, and the FAA TAF for comparison. The Master Plan forecast is based on the following scenario:

Organic growth: Organic growth in RNO enplanements would proceed as determined by the following

factors: (1) the growth in scheduled seat capacity at RNO in 2017, and (2) the most likely trends for the

key market demand drivers (i.e. regional economy, national economy, and passenger yield).

Aggressive air service development: RTAA’s air service development efforts would increase RNO’s

market capture rate to 100 percent by 2022, from the current market capture rate of 94 percent for

domestic traffic and 75 percent for international traffic estimated by the True Market Study.

The resulting forecast annual enplanements are within no more than 2 percent of the forecast annual

enplanements under the FAA TAF. They are closest to the 60-percentile result in 2018, the 65-percentile

results in 2019 and in 2030-2036, the 70-percentile results in 2020 and in 2026-2029, and the 70-percentile

results in 2021-2025. Under the Master Plan forecast, RNO’s share of forecast U.S. enplanements (FAA’s

March 2016 Aerospace Forecasts) would remain under 0.25 percent, meaning that RNO would remain a

small hub, except in 2024. RNO’s enplanements would approach their pre-recession peak level of 2.67 million

by 2032.

The high growth forecast is based on the following assumptions:

Organic growth: Organic growth in RNO enplanements would follow the 75-percentile growth rates,

largely driven by more favorable regional and national economic conditions than projected for the

Master Plan forecast.

Aggressive air service development: In addition to organic growth, aggressive air service development

efforts would increase RNO’s market capture rate to 100 percent by 2021.

Under the high growth forecast, annual enplanements are closest to the 95 percentiles in 2017-2023, 90

percentiles in 2024-2030, and 85 percentiles in 2031-2036. They are higher than the TAF by no more than 10

percent through 2036. RNO’s share of total U.S. enplanements would increase to at least 0.25 percent,

qualifying as a medium hub, by 2019. RNO’s enplanements would reach their pre-recession peak level of 2.67

million by 2027.

The 25-percentile result is recommended for a low growth scenario that can be used as a conservative basis

for financial analysis. Forecast annual enplanements are lower than the TAF by no more than 8 percent

through 2020, 15 percent through 2029, and 19 percent through 2036.

Chapter 2 - Aviation Activity Analysis and Forecast

2-38

Figure 2-30: Historical and Forecast Total Enplanements

Sources: RTAA for historical data, FAA for the TAF, and Unison Consulting, Inc. for the base regression and Monte Carlo simulation

forecasts.

1.4

1.6

1.8

2.0

2.2

2.4

2.6

2.8

3.0

3.2

3.4

3.6

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

2021

2022

2023

2024

2025

2026

2027

2028

2029

2030

2031

2032

2033

2034

2035

2036

Historical

Forecast

Enplanements

(Millions)

95%ile

90%ile

High

85%ile

80%ile

75%ile

70%ile

65%ile

60%ile

55%ile

TAF CY

Base

50%ile

45%ile

40%ile

35%ile

30%ile

25%ile

20%ile

15%ile

10%ile

5%ile

Chapter 2 - Aviation Activity Analysis and Forecast

2-39

Table 2-8 shows the forecast enplanements for the Master Plan forecast, low growth, and high growth

scenarios. Table 2-9 shows the corresponding forecast passenger aircraft landings, and Table 2-10 shows the

corresponding forecast passenger aircraft landed weight.

Table 2-8: Forecast Enplanements

Scenario

Enplanements (Thousand)

Compound Annual Growth

Rate

Actual

Forecast

Forecast

Master Plan (MP) Forecast

2016

2021

2026

2036

2016

-

2021

2021

-

2026

2026

-

2036

Domestic

1,803

2,

150

2,

385