Sacred Heart University Sacred Heart University

DigitalCommons@SHU DigitalCommons@SHU

WCBT Faculty Publications Jack Welch College of Business & Technology

2012

The Sarbanes Oxley Act's Contribution to Curtailing Corporate The Sarbanes Oxley Act's Contribution to Curtailing Corporate

Bribery Bribery

Karen Cascini

Sacred Heart University

Alan DelFavero

Sacred Heart University

Mario Mililli

Sacred Heart University

Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/wcob_fac

Part of the Business Law, Public Responsibility, and Ethics Commons, Corporate Finance Commons,

and the Finance and Financial Management Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Cascini, K., Delfavero, A., & Mililli, M. (2012). The Sarbanes Oxley Act's contribution to curtailing corporate

bribery.

The Journal of Applied Business Research,

28

(6), 1127-112. doi: 10.19030/jabr.v28i6.7329

This Peer-Reviewed Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Jack Welch College of Business &

Technology at DigitalCommons@SHU. It has been accepted for inclusion in WCBT Faculty Publications by an

authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@SHU. For more information, please contact santoro-

dillond@sacredheart.edu.

The Journal of Applied Business Research – November/December 2012 Volume 28, Number 6

© 2012 The Clute Institute http://www.cluteinstitute.com/ 1127

The Sarbanes Oxley Act’s Contribution

To Curtailing Corporate Bribery

Karen T. Cascini, Ph.D., Sacred Heart University, USA

Alan DelFavero, Sacred Heart University, USA

Mario Mililli, (Graduate Research Assistant), Sacred Heart University, USA

ABSTRACT

In the wake of corporate scandals occurring in the early 2000s, a need for stricter regulation was

deemed necessary by the investors of U.S. public companies. In 2002, the Sarbanes-Oxley Act

(SoX) was created. Accordingly, under the rules of SoX, U.S. corporations were faced with

increased oversight and also needed to substantially improve their internal controls. As

companies began to scrutinize their internal affairs more closely, some businesses detected other

forms of criminal activity occurring internally, such as bribery. Those companies and individuals

found to have committed bribery have violated the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act of 1977

(FCPA). Throughout this paper, a plausible correlation between SoX and a recent increase in

reported violations of the FCPA will be assessed. This possibility is evaluated via a presentation

of cases involving multinational corporations that have been found to have violated the FCPA.

Based on the authors’ research, a pattern does exist between SoX and the enforcement of the

FCPA. Finally, suggestions to modify the punishment for companies found guilty of committing

bribery are also presented.

Keywords: Bribery; FCPA; SEC; Extortion; Corruption; Corporate Corruption; Sarbanes-Oxley Act; Business

Ethics

INTRODUCTION

nce the booming U.S. economy of the 1990s gave way to the lackluster economic conditions of the

2000s, a multitude of financial accounting scandals began to surface. The most notorious of these cases

were Enron, MCI WorldCom, and Tyco. These cases of fraud were eventually exposed and investor

confidence began to unravel. Accordingly, Americans demanded stricter regulations on U.S. corporations.

Consequently, the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SoX) was born in the summer of 2002.

As the 2000s decade progressed, a different breed of corporate scandals began to surface. For example,

companies such as ABB Limited, Daimler Chrysler, El Paso Corporation, General Electric, Halliburton, Lee

Dynamics, Lucent Technologies, and Siemens AG were found guilty of violating U.S. law and consequently, also

rattled shareholders’ trust (Cascini & DelFavero, 2008, p.27). The named businesses were found guilty of

committing bribery, which is rendered illegal under the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act of 1977 (FCPA). The FCPA

is enforced by both the Securities & Exchange Commission (SEC) and the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ).

Though corporate bribery cases existed prior to the creation of SoX, the average number of investigations of FCPA

violations cases more than doubled when compared to the pre-SoX era (Cascini & DelFavero, 2008, p. 22).

Therefore, the following question could be raised: Is there a correlation between the increase in reported FCPA

violations and the creation of SoX?

The purpose of this paper is to examine the current trend in FCPA enforcement and to analyze whether a

relationship does exist between the enactment of SoX and the enhanced application of the FCPA. Recent corporate

violators of the FCPA will be presented. Also, any relevant updates to the aforementioned bribery cases will be

discussed.

O

The Journal of Applied Business Research – November/December 2012 Volume 28, Number 6

1128 http://www.cluteinstitute.com/ © 2012 The Clute Institute

FCPA & SOX OVERVIEW

In response to the public outrage over these accounting scandals occurring around 2001, former Senators

Paul Sarbanes of Maryland and Michael Oxley of Ohio drafted a law that intended to mitigate fraudulent activity

occurring at corporations in the U.S. After deliberations in Congress, the Bill was passed in a 423-3 vote by the

House of Representatives (U.S. House of Representatives, 2002) and by a 99-0 vote by the U.S. Senate (U.S. Senate,

2002). Accordingly, former President George W. Bush signed the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SoX) into law in July 2002.

SoX significantly overhauled the requirements for U.S. corporations with regard to financial accounting, internal

controls, and audits conducted by public accounting firms. Although the Act includes numerous sections, there are

two major sections that the authors will address.

First, Section 302 of SoX creates an environment where executives are considered liable for fraudulent

activity occurring within their corporation. If an executive intentionally conceals fraudulent activity, they are not

only subject to fines, but could face time in prison. CEOs and CFOs must assert that they have thoroughly analyzed

their corporations’ financial statements for representational faithfulness, and to their knowledge, the reported

numbers conform to U.S. Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP). Via a written report, these executives

must avow that they are responsible for assessing the internal controls of the corporation. Also, they must declare

that they have determined the degree of the effectiveness of internal controls and have also created a system where

inadequacies in internal controls are more apparent (Cascini & DelFavero, 2008, p.24).

In addition, corporations must report any deficiencies in internal control to both the public accounting firm

auditing the company’s financial statements and the audit committee. In conjunction, Section 404 of the Act

mandates that executives issue a report which includes their evaluation of internal controls, the manner in which

financial information is disseminated to public, and also the public accounting firm’s opinion of the entity’s internal

controls (Cascini & DelFavero, 2008, p 24/ Ge & McVay, 2005).

While SoX was established to counteract the increases in reported corporate criminal activity, the FCPA

was formed for a highly similar purpose. However, while SoX focuses on holding executives accountable for

“mirage accounting” transpiring within their corporations, the FCPA concentrates on combating bribery. During the

1970s, numerous U.S. corporations were found to have paid bribes to foreign government officials and foreign

corporations in an attempt to clinch business deals (Cascini & DelFavero, 2008, p. 22; Graham & Lam, 2007 p. 61).

The beginnings of the FCPA can be traced back to the fall of 1972. During September of that year,

Lockheed Corporation had made a $2,000,000 contribution to the Japansese Prime Minister in an effort to gain

business advantages. As news of the impending bribery scandal became public, not only was Lockheed Corporation

viewed in a highly negative light, but the Prime Minister was compelled to abdicate his role. Subsequently, in the

U.S., the SEC launched a comprehensive investigation into the practices of numerous U.S. corporations and

determined that approximately 450 other companies were also guilty of bribing foreign officials. Amid discontent

with U.S. business practices abroad, Congress approved the Foreign Corrupts Practices Act in 1977 and thus, the

Act became law (Cascini & DelFavero, 2008, p.22; Graham & Lam, 2007, p.61). The FCPA is enforced by the DOJ

and SEC.

Since the FCPA’s inception in 1977, there have been various addendums to the law. In the Act’s original

state, the law focused on penalizing U.S. businesses that were found guilty of bribing “foreign officials.”

A foreign official “denotes any officer or employee of a foreign government or any department, agency, or

instrumentality thereof, or a public international organization, or any persons acting in an official capacity for or

on behalf of any such government or department, agency or instrumentality, or for on behalf of any such public

international organization (U.S. Fifth Congress, 1998).

While the original statutes of the law still exist, there were significant updates to the Act in both 1988 and

1998. In 1988, the FCPA was modified to allow for employees of U.S. corporations to be held liable for committing

acts of bribery prior to their employer being charged (Cascini & DelFavero, 2008, p.22). For example, if it is proven

that an employee at a business offered a bribe to a foreign official; the employee can be charged under the FCPA

before the entity is charged.

The Journal of Applied Business Research – November/December 2012 Volume 28, Number 6

© 2012 The Clute Institute http://www.cluteinstitute.com/ 1129

In 1998, application of the Act was extended to foreign corporations via the “International Bribery Act.”

This amendment created an environment where it would be illegal for officers and/or employees of foreign

businesses to offer inducements to U.S. businesses (Cascini & DelFavero, 2008, p.22).

Corporations found guilty of violating the provisions of the FCPA face significant penalties. Not only can

the business be fined for millions of dollars, but the executives, if found guilty, can face up to five years of jail time

(Cascini and DelFavero, 2008, p. 23). However, the punishment can vary drastically due to the level of severity of

the crime(s). Throughout the remainder of this paper, examples of corporations violating the FCPA will be

presented. However, it must be noted that the cases of bribery are not limited solely to the following companies.

Primarily, the major, multinational companies will be discussed.

RECENT FCPA VIOLATION CASES

Corporations will break the rules for various reasons. There is one major goal that all corporations strive to

achieve, and that is to increase profitability. Of course, a corporation is expected to behave ethically when boosting

sales and net income. Nonetheless, the ensuing cases demonstrate that some companies will go to great measures to

not only enhance net income, but will also attempt to conceal possible violations of the law. The following

examples include companies in the technology, food & beverage, defense, and retail sectors that were found to have

violated the FCPA. The first case, which involved the multinational conglomerate, General Electric, is presented in

the following section. For a brief summary of all of the bribery cases, see Table 1 below.

Table 1

FCPA Violations Chart

Company Year(s) Crime SOX FCPA / SEC Penalty

Violations Violations

General Electric 2000-2003

Kickback scheme to bribe Iraqi government agencies

N/A B&R, ACP $23.5 m

IBM

1998 - 2003, 2004-

2009

Improper cash payments to government officials in South Korea and China, as

well as giving gifts and paying travel and entertainment expenses

N/A AB, B&R, ACP $10 m

Kraft Foods

Late-2000s

Kraft subsidiary may have offered bribes to Indian government agencies in

exchange for business

N/A NYD NYD

Diageo 2003-2009

Improper payments to government officials in India, Thailand, and South Korea

N/A B&R, ACP $16 m

Tyson Foods 2004-2006

Concealing improper payments by putting veterinarians’ wives on its payroll while

they performed no services for the company

N/A AB, B&R, ACP $5.2 m

Armor Holdings, Inc 2001-2006

Bribery scheme to obtain contracts to supply body armor for use in the United

Nations peacekeeping missions

N/A AB, B&R, ACP $16 m

Avon 2004-2006

Avon employees paid bribes to Chinese government officials and was granted a

license to sell products in the country

N/A NYD NYD

Wal-Mart 2005-Present

Wal-Mart may have paid Mexican officials bribes to be granted the right to expand

business

N/A NYD NYD

FCPA Violation Abbreviations

Anti-Bribery Provison (Sec 30A of SEC Act of 1934) =AB

Books & Record Provision (Sec 13 (b)(2)(A) of SEC Act of 1934) =B&R

Accounting Controls Provisions (Sec 13 (b)(2)(b) of SEC Act of 1934) =ACP

Not Yet Determined, but at least Sec 30A of SEC Act of 1934 if charged = NYD

Technology Sector

General Electric (GE)

In June of 2010, the SEC alleged that two of GE’s subsidiaries (Marquette-Hellige and OEC Medical

Systems AG) and two of GE’s aquirees (Iconics, Inc. and Amersham plc) were embroiled in a bribery plot where

“cash, computer equipment, medical supplies and services” were offered as inducements to the “Iraqi Health

Ministry or the Iraqi Oil Ministry, under the U.N. Oil for Food Program, to win contracts to supply medical

equipment and water purification equipment” (SEC, July 2010).

The Journal of Applied Business Research – November/December 2012 Volume 28, Number 6

1130 http://www.cluteinstitute.com/ © 2012 The Clute Institute

The SEC claimed that Marquette-Hellige offered bribes to the Iraqi Health Ministry to obtain valuable

contracts. The company employed various bribery methods to clinch three lucrative deals. For example, Marquette-

Hellige offered “$1.2 million of goods and services to the Iraqi Health Ministry to obtain two contracts and also

offered $250,000 in a sweetener to obtain the third deal.” In addition, the other subsidiary, OEC-Medical, paid

$870,000 in bribes to secure one contract. However, the fraud was more profound with this subsidiary. In order to

conceal the kickbacks, OEC-Medical created faux transactions which resulted in additional commissions for an

intermediary agent facilitating the “business deals.” These monies were then redirected to the Iraqi government in

the form of bribes. As a result of the corrupt payments, Marquette-Hellige and OEC Medical gained contracts worth

$8.8 million and $2.1 million, respectively (SEC, July 2010).

In addition, during the early 2000s, one of Amersham’s subsidiaries rewarded Iraqi officials with $750,000

in kickbacks for the rights to business contracts. As a result, the bribe generated $5 million in unethical profits.

Also, during roughly the same time period, Iconics paid $795,000 in illegal rewards as well. The SEC alleged that

Iconics sold water treatment equipment to the Iraqi Oil Ministry and accordingly, earned $2.3 million. Nonetheless,

these profits were made as a direct result of committing bribery. Although GE did not have any involvement with

these bribes when they occurred, GE acquired Amersham in 2004 and Iconics in 2005, and thus, assumed

responsibility (SEC July 2010).

In July 2010, the SEC penalized GE with a $23.5 million fine. The penalty was comprised of both a

repayment of the $18.4 million of profits made under the corruption schemes and $5.1 million of other penalties.

According to Cheryl Scarboro, Chief of the SEC’s FCPA Unit, the main issue with GE was that they “failed to

maintain adequate internal controls to prevent the illicit payments by its two subsidiaries….and it failed to record the

true nature of these payments in its accounting records” (SEC, July 2010). In addition, Ms. Scarboro indicated that

a merger or acquisition does not relieve the acquiring firm from responsibility if the acquiree is found to have been

engaged in corrupt business activity (SEC, July 2010). Hence, a company planning to purchase another company

must be certain that the prospective acquiree has abided by the law. If it is later determined that the target company

disobeyed the rules, the acquirer will be held accountable.

IBM

Another example of corporate bribery involved the technology giant International Business Machines

(IBM), which was involved in multiple cases of bribes. In the first case, employees at IBM’s Korean subsidiary

(IBM Korea) “and a majority owned joint venture called LG IBM PC CO. ltd,” offered and paid $207,000 in

kickbacks to South Korean government officials in order to sell goods manufactured by IBM. The kickbacks were

not only limited to cash, but also included the company offering to pay for the entertainment and travel expenses of

these government leaders. According to the SEC, IBM employees would “stuff bags with up to $20,000 in cash” to

effectuate the payment. Reportedly, the scheme transpired from 1998 to 2003 (SEC, March 2011).

In addition, the second scandal occurred within Asia. From approximately 2004 to 2009, in excess of 100

IBM workers at IBM China Investment Company and IBM Global Services “provided gifts, entertainment, and

payment for travel expenses of Chinese government officials.” These gifts consisted of technological gadgets and

equipment (SEC, March 2011). Also, according to the SEC, IBM created “slush-funds” to finance the purchases of

these devices and as well as the payments for the travel expenses (SEC, March 2011, pg. 8).

While IBM didn’t face criminal penalties, in March 2011, the SEC ruled that IBM had violated the books

and records and internal controls provisions of the FCPA. Also the company breached the Securities Act of 1934

with regard to Sections 13(b)(2)(A) for “improperly recording payments in its books and records” and 13(b)(2)(B)

for lacking “adequate internal controls to detect and prevent” (SEC, March 2011). In addition, the SEC claimed that

IBM lacked well-developed internal controls to prevent the fraud from occurring at international subsidiaries to

begin with. Accordingly, IBM settled with the SEC for a $10 million penalty on civil charges.

The Journal of Applied Business Research – November/December 2012 Volume 28, Number 6

© 2012 The Clute Institute http://www.cluteinstitute.com/ 1131

Food/Beverage Sector

Kraft

While technology companies have been presented thus far, cases of corporate bribery are not limited to that

industry. The following case involves a company in the food and beverage processing sector. In March 2011, the

SEC subpoenaed Kraft Foods for possible FCPA violations in India at a facility operated by Kraft’s subsidiary,

Cadbury. In 2010, Kraft purchased Cadbury, the famous producer of candy, beverages, and other confectionary

foods, for $19 billion (Stone, March 2011). Although Kraft indicated that they believed that Cadbury had solid

ethics, “there appeared to be facts and circumstances warranting further investigation” at one of the company’s

plants in India (Stone, March 2011). The possibility exists that there were “sweeteners” offered to Indian

government agencies and officials by Cadbury’s Indian subsidiary in order for the company to be granted

permission to operate a factory. As of this writing, Kraft is still under investigation, but is fully cooperating with the

SEC (Kraft 2011 Annual Report, February 2012, p.17).

Diageo

Between 2003 and 2009, London-based Diageo plc, the global producer of alcoholic beverages, offered

over $2.7 million in illegal payments to officials in Asia and India. Although Diageo is a British company, its

common stock trades as an American Depository Receipt on the New York Stock Exchange with the ticker symbol

DEO, and thus, is subject to the FCPA and the Securities & Exchange Act of 1934. Similar to the previously

mentioned cases of corruption, Diageo’s main objective was to inflate revenues and profits. According to the SEC,

Diageo disobeyed the FCPA on multiple occasions (SEC, July 2011).

The Associate Director of the SEC’s Division of Enforcement, Scott W. Friestad, stated, “For years,

Diageo’s subsidiaries made hundreds of illicit payments to foreign officials.” With regard to the bribery in India,

the SEC claimed that Diageo generated over $11 million in profits from making “more than $1.7 million in illicit

payments to hundreds of government officials.” These government officers had the direct authority to “purchase

and authorize the sale” of Diageo’s products in the country (SEC, July 2011).

In a separate case, Diageo distributed $600,000 in illegal money to a member of Thailand’s government.

Subsequently, the government official became an advocate for Diageo and persuaded other government officials to

view the company favorably with regard to “pending multi-million dollar tax and custom disputes” (SEC, July

2011). Thus, the payoff helped facilitate advantageous business conditions for the company.

Continuing with the topic of tax advantages, Diageo also disbursed approximately $86,000 to a customs

representative in South Korea. The reward was given to the individual for his participation in a plot to influence the

South Korean government to offer certain tax rebates to Diageo (SEC, July 2011). As further compensation, the

company also funded $100,000 of entertainment and travel expenses for those government and customs officials that

were directly involved in offering the tax benefits (SEC Administrative Proceeding, July 2011).

Nonetheless, the extortion in South Korea was not limited to government and customs officials. According

to the SEC, Diageo offered in excess of $230,000 in illegal cash incentives to officers in the South Korean military.

These “bonuses” were issued to persuade members of the military to purchase Diageo products (SEC Administrative

Proceeding, July 2011).

In July 2011, the SEC charged Diageo for also violating Sections 13(b)(2)(A) and 13(b)(2)(B) of the

Securities Act of 1934. The company agreed to forfeit $16 million, which was comprised of $11 million earned in

corrupt profits as well as prejudgment interest and a financial penalty. The ruling indicated that Diageo didn’t have

effective internal controls in place to detect fraud at the company as well as the subsidiaries. Also, the company was

condemned for not properly accounting for the bribes in their accounting records. Instead, the company disguised

the bribes as normal business expenses, presented them in a confusing and indistinct manner, or ignored the

payments altogether. Consequently, the company has overhauled and strengthened its FCPA compliance program

and eliminated the employees who were involved in the illegal activity (SEC, July 2011).

The Journal of Applied Business Research – November/December 2012 Volume 28, Number 6

1132 http://www.cluteinstitute.com/ © 2012 The Clute Institute

Tyson Foods Inc.

The Mexican subsidiary of Tyson Foods Inc. was accused by the SEC of devising an elaborate bribery

scheme. Tyson, headquartered in Arkansas, is one of the world’s largest suppliers of poultry products. Between

2004 and 2006, Tyson de Mexico made a total of $100,311 in illegal payments to two Mexican government

veterinarians (SEC, February 2011). These veterinarians had the authority to determine whether the poultry being

produced at the two plants in Gomez Palacio, Mexico met health standards established by the Mexican Government.

If approved, the meat can be exported to other consumer nations. Although one may believe that the purpose of a

bribe in this case would be to allow for bad meat to be passed as edible, according to the DOJ, this is not the case.

The main goal of Tyson was to “keep the veterinarians from disrupting the operations of the meat-production

facilities.” Consequently, Tyson made $880,000 in illegal profits (DOJ, February 2011).

Nonetheless, the company went to great measures to conceal the payoffs. For instance, Tyson placed the

wives of the veterinarians on the payroll in an attempt to create the illusion that the extra payments were made for

legitimate purposes. These spouses, however, never worked a day Tyson! This tactic was later reversed as a plant

manager at the Mexican subsidiary “blew-the-whistle” to an accountant of Tyson Foods Inc. in June 2004. Yet, this

charade was not stopped. With the approval of an executive at Tyson International, the wives were removed from

the payroll and the payments were reallocated to one veterinarian in the company’s accounting records. Thus, even

though Tyson Inc. knew of the corruption in Mexico as early as 2004, they failed to report the prohibited activity

until two years later (SEC, February 2011). The company did, however, eventually report their own violations to

the U.S. Government (DOJ, February 2011).

In February 2011, the SEC ruled that Tyson had violated the both the FCPA and “Section 30A (for making

illegal payments to foreign government officials to obtain business),” 13(b)(2)(A), and 13(b)(2)(B) of the Securities

& Exchange Act of 1934. On civil charges, the company was fined in excess of $1.2 million for “violating the anti-

bribery, books and records, and internal controls provisions of the FCPA” along with disobeying the Securities Act.

The fine required disgorgement of the illicit profits made (SEC, February 2011).

In addition, the DOJ fined Tyson over $4 million for conspiring to violate and actually violating the FCPA.

However, this penalty was for criminal violations. In addition to the Mexican subsidiary violating the FCPA, Tyson

International cooperated and attempted to devise new ways to conceal the bribes. As part of the agreement with the

DOJ, Tyson had to also “implement rigorous internal controls, and cooperate fully with the [Justice] Department”

(DOJ, February 2011). According to Robert Khuzami, “Tyson and its subsidiary committed core FCPA violations

by bribing government officials through no-show jobs and phony invoices and [had] a lax system of internal controls

that failed to detect of prevent the misconduct” (SEC, February 2011). Nonetheless, even in cases where companies

eventually turn themselves in for breaching the FCPA, criminal penalties may still be applied.

Defense Sector

Armor Holdings, Inc.

The next example of corporate bribery includes a business in the defense industry. Armor Holdings Inc,

the producer of law enforcement and military safety gear, was fined by the SEC, in July 2011, for also violating the

FCPA. However, Armor is no longer an independent corporation as it was acquired by BAE Systems in July 2007,

and is currently a subsidiary of BAE (DOJ, July 2011). The corruption in this instance was more severe than

previous cases because officers of the United Nations were involved. According to the SEC, Armor Holdings (as a

stand-alone company), between 2001 and 2006, disbursed a total of $222,750 in bribes to an unnamed U.N. official

(SEC, July 2011). However, the kickbacks were not limited to a single event. Based on the SEC’s assertions, the

$222,750 in kickbacks was totaled from 92 illicit payments! (SEC, July 2011).

The SEC argued that the company awarded bribes to a U.N. diplomat who “could help steer business

toward Armor’s U.K. subsidiary” (SEC, July 2011). As a consequence of these prohibited payments, Armor was

awarded two lucrative contracts for supplying the U.N officials with body armor (DOJ, July 2011). Thus, the corrupt

business deal enhanced revenues and net profits for the company by $7.1 million and $1.5 million, respectively

(SEC, July 2011).

The Journal of Applied Business Research – November/December 2012 Volume 28, Number 6

© 2012 The Clute Institute http://www.cluteinstitute.com/ 1133

The SEC ruled that Armor had violated Sections 30A, 13(b)(2)(A), and 13(b)(2)(B) of the Securities Act of

1934, and thus needed to forfeit a total of $5.7 million. The fine was comprised of illegal profits, prejudgment

interest, and civil penalties. The SEC also argued that Armor did not have a thorough internal control system in

effect to detect and halt the fraudulent activity from occurring (SEC, July 2011).

With regard to violating the FCPA, the Department of Justice penalized the company for $10.29 million.

Also, the DOJ and the SEC mandated that the company establish “rigorous internal controls” and have a strict FCPA

compliance program in place (DOJ, 2011). Overall, the corrupt payments going to U.N. diplomats may be viewed

as worse than bribes being awarded to “typical” foreign officials. U.N. officials are considered to be “peacekeepers”

and should not be involved in illegal activities.

Retail Sector

Avon

Avon Products Inc, in October 2011, disclosed to the public that the SEC had launched an investigation

into possible violations of the FCPA. Via an internal probe, Avon discovered that company employees had made

“questionable payments” worth millions of dollars to foreign officials (Flahardy, October 2011). In June of 2008,

Avon notified the SEC and DOJ that the company’s audit committee was researching plausible FCPA compliance

issues in China and other countries. These investigations focused on “business dealings, directly or indirectly, with

foreign governments and their employees” (Avon 2011 Annual Report, pg. 14). As a result of the investigation,

Avon terminated “four executives suspected of paying bribes to officials in China” (Hurtado, February 2012). In

February 2012, amidst a shareholder class action lawsuit, evidence was presented against Avon. The facts showed

that in a 2005 internal audit report, the company indicated that “hundreds of thousands of dollars” in bribes were

possibly doled out to Chinese officials (Post, February 2012). Shortly thereafter, in 2006, China granted Avon a

license to allow for sales agents to sell products directly to customers. Until this time, Avon was only allowed to

have stores within the nation. The class action lawsuit brought forth by shareholders argued that corrupt employees

had “paid to schedule meetings between the CEO and high-level Chinese government ministers, repeatedly treating

Chinese licensing officials to dinner and karaoke” (Kowitt, April 2012).

Although U.S executives may not have caused the crimes, the argument is that it is their responsibility to

learn of and rectify illegal activities occurring within their business as soon as the corruption occurs (Post, February

2012). Accordingly, in addition to three executives in China being fired, Avon’s CFO, Charles Cramb, was

eliminated from the company in January 2012, on speculation that he had known about the corruption in China for

years. Also, in December 2011, Avon announced that its CEO, Andrea Jung, was stepping down from her role.

However, there was no formal connection between Jung’s resignation and the bribery inquiry (Kowitt, April 2012).

Although the SEC has not decided on a penalty for Avon, the internal FCPA investigation has proved to be

costly for the company. Between 2009 and 2011, Avon has spent in excess of $247 million on its internal

investigations (Henning, March 2012). Thus, while civil and/or criminal penalties can be costly, the investigative

process can substantially reduce profits as well.

Wal-Mart/Wal-Mex

In recent news, Wal-Mart Inc, the largest retailer in the world, has been accused of committing acts of

bribery in Mexico. Allegedly, Wal-Mart’s Mexican operations (called WalMex) may have paid bribes to Mexican

government officials to expand business in the country. In December 2011, Wal-Mart had disclosed to the SEC and

the DOJ that the company had discovered “potential violations” of the FCPA and was conducting an internal

investigation. In April 2012, the New York Times published an article indicating that Wal-Mart executives, as early

as 2005, had learned that kickbacks may have been used to facilitate the torrent expansion of the retail giant

(Bustillo, April 2012, pg. B1).

To complicate matters, the New York Times reported that executives at Wal-Mart headquarters in

Arkansas, “shut down the investigation” when they learned of the plausible bribery scheme (Martin, April 2012).

The Journal of Applied Business Research – November/December 2012 Volume 28, Number 6

1134 http://www.cluteinstitute.com/ © 2012 The Clute Institute

Kevin T. Abikoff, chairman of the anti-corruption practice law-firm Hughes Hubbard & Reed LLP, asserted that if

the DOJ and SEC find Wal-Mart guilty of committing bribery, “the Justice Department will ‘levy as large a fine as

possible.” This can be attributed to the fact that Wal-Mart did not report the possible corruption until years later

(Bustillo, April 2012, pg. B1).

In addition to the SEC and DOJ investigating Wal-Mart, Mexican officials have now launched an

investigation into the business practices at WalMex. In response to the intense pressure, the company has started a

comprehensive internal investigation, and has also “bolstered its training, auditing, and internal controls to ensure

better compliance with laws against bribery” (Martin, April 2012).

If Wal-Mart is found guilty, the fines imposed for disregarding the FCPA has the potential to be one of the

largest of all-time due to the company’s vast global reach. In addition, the company can begin to lose sales as some

individuals may be inclined to give their business to competitors who are perceived as “more ethical.”

ANALYSIS

The aforementioned bribery cases illustrated that all companies offered payoffs in an effort to augment

their profits. In some of the examples, however, the corporation reported their own violations of the FCPA to the

SEC and/or DOJ. The possibility exists that these breaches of the law were detected due to the rigorous internal

control requirements of SoX. In addition, SoX requires that all public companies be faced with tougher regulations

and increased oversight. While corporations certainly violated the FCPA prior to SoX’s inception, the number of

reported bribery cases increased exponentially in recent years. For example, of the 103 SEC FCPA violation cases

reported to the SEC between 1978 and 2011, 90 of them transpired after 2001. Hence, 87% of all reported

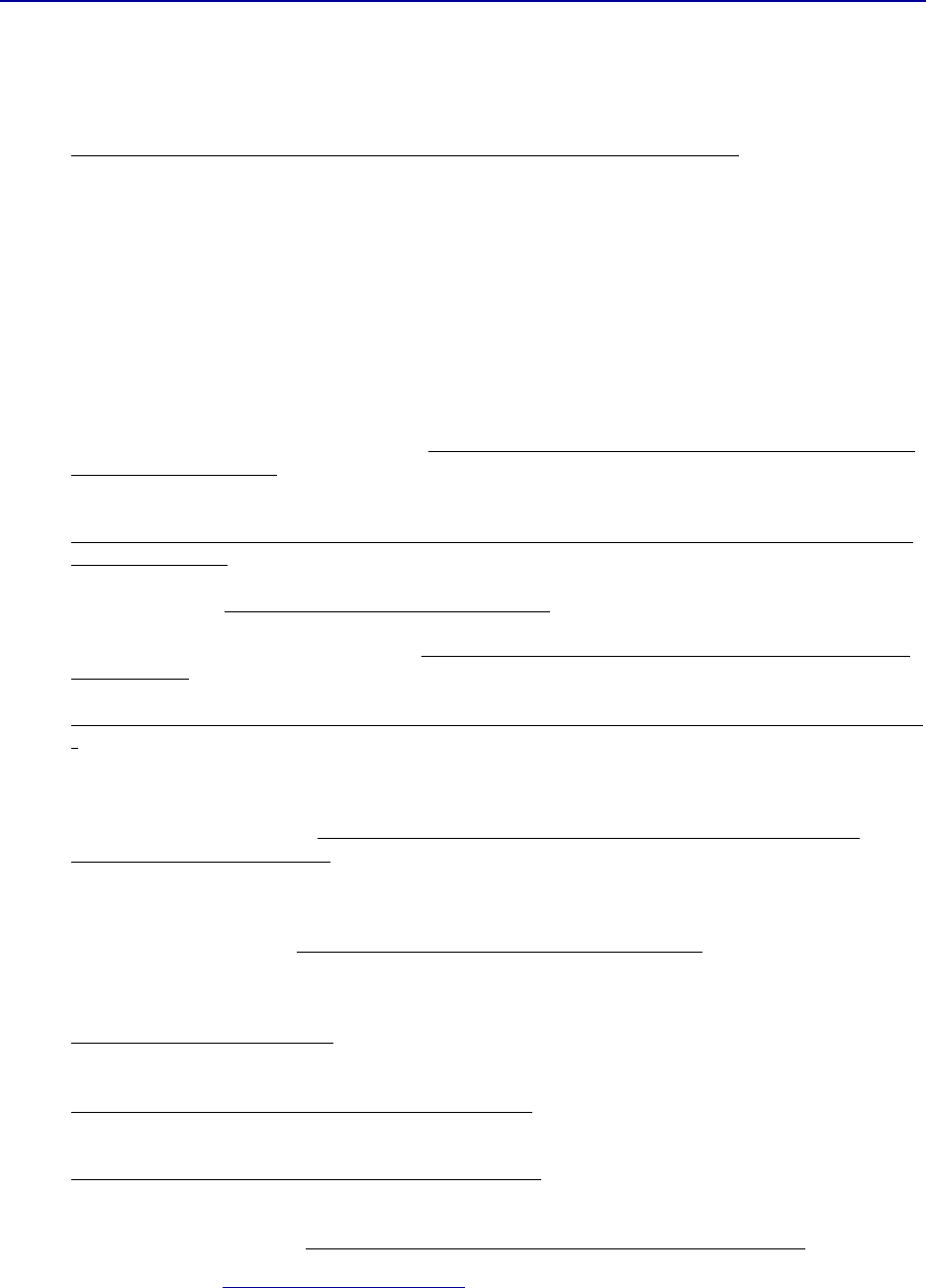

investigations occurred after the creation of SoX (See Chart 1).

Demonstrated by the above graphical representation, the number FCPA enforcement actions grew

substantially in the post-SoX era. The number of reported violations between 2002/2003 and 2004/2005 doubled,

while between 2004/2005 and 2006/2007, there was a 225% increase. Although enforcement actions have “leveled

off” since 2006/2007, they remain at an elevated level. Therefore, the following question could be raised: Is the

stark increase in enforcement actions due to SoX?

Although the jump in activity can be coincidental, the authors believe otherwise. Prior to 2002, the number

of enforcement actions was paltry when compared to post-2001. Therefore, the authors find that a clear pattern

exists between the creation of SoX and the enhanced enforcement of the FCPA. This development can be attributed

to the internal control requirements and the strict oversight that SoX requires. Thus, as companies are forced to

thoroughly evaluate every facet of their business, they are finding their violations and reporting them to the

4

1

8

4

8

26

22

30

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

1978-'85

'86-'93

'94-2001

'02 & '03

'04 & '05

'06 & '07

'08 & '09

'10 & '11

# of Enforcement Actions

Years

FCPA Enforcement Actions

Source: SEC Enforcement Actions: FCPA Cases (http://www.sec.gov/spotlight/fcpa/fcpa-cases.shtml)

Chart 1

The Journal of Applied Business Research – November/December 2012 Volume 28, Number 6

© 2012 The Clute Institute http://www.cluteinstitute.com/ 1135

appropriate authorities. In addition, as the SEC and DOJ have become more aware of bribery, they are more

actively investigating corporations.

CONCLUSION

While most of the companies presented above were not found to be repeat offenders of the FCPA, there are

chronic violators as well (See Appendix A). Fortunately, the level of FCPA enforcement by the SEC and the DOJ

has reached record levels. In the opinion of the authors, the creation of SoX has had a direct impact on the

enforcement of the FCPA. Based on the authors’ research, approximately 87% of FCPA enforcement cases reported

by the SEC, between 1978 and 2011, occurred after the inception of SoX in 2002. This can be attributed to SoX’s

requirements for strict oversight and greater internal control.

Nonetheless, companies may be compelled to violate the FCPA if the possible benefits exceed the costs.

In nearly all of the examples presented above (and in Appendix A), the companies surrendered illegal profits made

along with a small fine. However, as these penalties are rather small in comparison to corporation’s total sales, there

exists the distinct possibility that the number of actual bribery cases is vastly understated. While the level of FCPA

enforcement has increased dramatically, there may be many other companies that proceed with corrupt activity and

are never caught. Therefore, the authors propose the following question: “How large must a fine be to stop

companies from participating in unethical behavior?”

While the monetary penalties assessed were significant, the fines were small in comparison to a

corporation’s total revenue. With the exception of the Siemens (See Appendix A), the fines were “only” in the

millions. However, if the law was modified to cause the costs of bribery to exceed the benefits by a much greater

margin, then the level of corruption might begin to decline.

The authors propose that instead of companies disgorging profits made (along with other relatively small

fines), a percentage of total revenue fine should apply. This percentage should be based on the severity of the crime.

Thus, criminal violations should be assessed a higher percentage than civil violations. For example, Tyson Inc. paid

approximately $5 million in penalties. However, if the proposed percentage of revenue fine was assessed at a mere

1%, Tyson’s total bill (using 2011 revenue) would have been over $332 million! In nearly all of the cases, the fine,

as a percentage of revenue, was miniscule (See Table 2 below for fines as a percentage of revenue for the above

companies. For those companies listed in the appendix, see Table 3). Certainly, the cost of committing bribery

exceeds the benefit, in this case, if the proposed rule was in effect.

Company Revenue $ %

GE 147.3 B 0.0160%

IBM 106.9 B 0.0094%

Kraft 49.2 B NYD

Diageo Liquor 13.2 B 0.1212%

Tyson Foods 32.2 B 0.0161%

Armor Holdings 2.36 B 0.6737%

Avon 11.3 B NYD

Wal-Mart

443.8 B

NYD

FCPA Violation Fines as a % of Revenue

2011

2012

NYD

NYD

NYD

2010

2011

2011

16 M

5.2 M

2006

15.9 M

Year

FCPA Payment $

2011

10 M

2011

23.5 M

Table 2

The Journal of Applied Business Research – November/December 2012 Volume 28, Number 6

1136 http://www.cluteinstitute.com/ © 2012 The Clute Institute

In addition, it’s recommended that these companies create a system that is conducive to being more socially

responsible. For example, the proposed percentage of revenue fine could be used to aid the economy, as these

monies could be allocated to college scholarship funds. In addition, the penalties could be applied to other projects

such as, improving the infrastructure in the U.S., researching new clean technologies for energy, or used for

additional philanthropic purposes. Thus, money going directly to society might be more beneficial to the economy

as a whole. However, there must be oversight here as well to make sure that the funds go to the appropriate parties.

As presented above, companies that are striving to gain and/or retain business will go to extreme measures

to bolster their income. While the enforcement of the FCPA is heading in the right direction, there needs to be other

measures made to significantly reduce bribery. Besides the percentage of revenue fine, increased publicity and

public embarrassment may also be effective tools in mitigating crime. Nonetheless, SoX should not only be

regarded as helpful to the FCPA, but an essential factor in the FCPA’s application. In conclusion, ethical business

practices are critical if a thriving economy is to exist. Thus, without ethics, there is no trust in business.

AUTHOR INFORMATION

Karen Cascini has been a professor of Accounting for twenty years at the John F. Welch College of Business,

Sacred Heart University in Fairfield, Connecticut. She teaches advanced accounting courses to undergraduate

students and international accounting in the MBA program. Dr. Cascini received her Ph.D. from the University of

Connecticut and is a licensed certified public accountant in the state of Connecticut. Her research interests include

international and financial accounting and accounting ethics. She has traveled extensively presenting papers and

teaching accounting topics to an international audience. She is widely published and her work appears in such

journals as the Journal of International Financial Management and Accounting (JIFMA), The CPA Journal, The

Journal of Business Case Studies to name a few. Dr. Cascini can be contacted at cascinik@sacredheart.edu

(Corresponding author)

Alan DelFavero is currently an adjunct accounting instructor at the John F. Welch College of Business, Sacred

Heart University in Fairfield, Connecticut. He teaches introductory financial and managerial accounting courses and

intermediate accounting. In 2006, DelFavero graduated summa cum laude from the Welch College of Business with

a finance major and an accounting minor. While immediately pursing his MBA, he worked as Dr. Karen Cascini’s

graduate research assistant for the academic year 2007/2008. DelFavero earned a gold medal, in 2008, for achieving

a 3.97 GPA, the highest in his graduating class. He is also a member of three national honors societies, and has had

other published works appearing in The Journal of Business & Economics Research and The Journal of Applied

Business Research. E-mail: A-DelFavero@sacredheart.edu

Mario Mililli is currently an MBA graduate research assistant for Dr. Karen Cascini at the John F. Welch College of

Business, Sacred Heart University in Fairfield, Connecticut and will start his accounting career at KPMG in the fall

of 2012. He has completed his bachelor’s degree in accounting and is currently sitting for the CPA exam.

REFERENCES

1. ABB, Inc. (2010). ABB resolves Foreign Corrupt Practice Act Issued and Will Pay a Total of $58.3

million. Retrieved April 1, 2012, from

http://www.abb.com/cawp/seitp202/b7aa479846d0fe19c12577ae0017bfa0.aspx

2. Avon, Inc. (2012). Avon 2011 Annual Report, 14. Retrieved April 25, 2012, from

http://investor.avoncompany .com/phoenixzhtml?c=90402&p=irol-reportsannual

3. Boyle, Matthew. (February 28, 2011). Kraft Gets Subpoena From SEC Concerning Indian Investigation.

Retrieved April 25, 2012 from Bloomberg News website: http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2011-02-

28/kraft-gets-subpoena-from-sec-concerning-fcpa-probe.html

4. Bray, Chad. (December 14, 2011). U.S. Charges Ex-Siemens Executives in Alleged Bribery Scheme. Wall

Street Journal.

5. Bustillo, Miguel. (April 23, 2012). “Wal-Mart Faces Risk in Mexican Bribe Probe.” Wall Street Journal.

p.B1.

The Journal of Applied Business Research – November/December 2012 Volume 28, Number 6

© 2012 The Clute Institute http://www.cluteinstitute.com/ 1137

6. Cascini, Karen, and DelFavero, Alan. (October 2008). An Assessment of the Impact of the Sarbanes-Oxley

Act on the Investigating Violations for the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act. Journal of Business &

Economics Research, 6, 21-31

7. Censky, Annalyn. (April 1, 2010). Mercedes Maker Settles Bribe Case for $185 million. Retrieved April

17, 2012, from CNNMoney website:

http://money.cnn.com/2010/04/01/news/international/daimler_settlemen t/index.htm

8. Clanton, Brett. (2007, July 23). “KBR, Halliburton Get Boost After Breakup: KBR Setting Fast Pace;

Halliburton Also Seeing Gains.” Knight Rider Tribune Business News. p.1.

9. Crawford, David and Esterl, Michael. (2007, November 16). Siemens Ruling Details Bribery Across the

Globe. Wall Street Journal.

10. Ewing, Jack and Javers, Eamon. (2007, November 26). Siemens Braces for a Slap from Uncle Sam.

Business Week, 78.

11. Flarhardy, Cathleen. (October 2011). “SEC Investigates Avon for FCPA Violations.” Inside Counsel.

12. Ge, Weili and McVay, Sarah. (September 2005). The Disclosure of Material Weaknesses in Internal

Control after the Sarbanes-Oxley Act. Accounting Horizons, 19,.3,137-158

13. Grace, Kelly. (2009, February 12). Halliburton, KBR to Pay Record Fine. Wall Street Journal. p. B2.

14. Graham, John and Lam, N. Mark. (2207). China Now. New York, NY: McGraw Hill.

15. Henning, Peter. (March 5, 2012). The Mounting Costs of Internal Investigations. Retrieved April 25, 2012

from New York Times Deal Book website: http://dealbook.nytimes.com/2012/03/05/the-mounting-costs-

of-internal-investigations/

16. Hurtado, Patricia. (February 13, 2012). Avon Produces Said to Be Focus of U.S. Grand Jury Probe of

Chinese Bribery. Retrieved April 25, 2012 from Bloomberg News website:

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2012-02-13/avon-products-said-to-be-probed-by-u-s-grand-jury-tied-to-

bribery-claims.html

17. Katz, David. (November 8, 2004). Bribes and the Balance Sheet. Retrieved on April 8, 2012 from the

CFO.com website: http://www.cfo.com/article.cfm/3370117

18. Kowitt, Beth. (April 11, 2012). Avon: The Rise and Fall of a Beauty Icon. Retrieved April 25, 2012 from

the CNNMoney/Fortune Magazine website: http://management.fortune.cnn.com/2012/04/11/avon-andrea-

jung-downfall/

19. Kraft Foods. (February 27, 2012). Kraft 2011 Annual Report. p. 17. Retrieved April 25, 2012 from

http://www.kraftfoodscompany.com/SiteCollectionDocuments/pdf/investor/KraftFoods_10K_20120227.pd

f

20. LaCroix, Kevin. (2007, April 2). Foreign Corrupt Practices Act: A ‘70s Revival and Growing D&O Risk.

National Underwriter, P&C 111, 13.

21. Martin, Andrew. (April 24, 2012). Wal-Mart Vows to Fix Its Controls. Retrieved April 28, 2012 from the

The New York Times website: http://www.nytimes.com/2012 /04/25 /business/ wal-mart-says-it-is-

tightening-internal-controls.html

22. Post, Ashley. (2012, February). Grand Jury Hears Avon Case. Inside Counsel.

23. Stone, David. (2011, March). Kraft Subpoenaed over 2010 Takeover of Cadbury. Food Magazine.

24. Taub, Stephen. (October 16, 2006). SEC Settles Bribery Charges with Statoil. Retrieved April 10, 2012

from the CFO.com website: http://www.cfo.com/article.cfm/8047389?f=related (Accessed April, 10,

2012).

25. University of Cincinnati, College of Law. Securities Lawyer’s Deskbook. (Section 30A-Prohibited Foreign

Trade Practices by Issuers). Retrieved April 12, 2012 from University of Cincinnati website:

http://taft.law.uc.edu/CCL/34Act

26. U.S. Department of Justice. (July 13, 2011). Armor Holdings Agrees to Pay $10.2 Million Criminal Penalty

to Resolve Violations of the FCPA. Washington, DC: Retrieved April 27, 2012 from the DOJ website:

http://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/2011/July/11-crm-911.html

27. U.S. Department of Justice. (April 1, 2012). Daimler AG and Three Subsidiaries Resolve Foreign Corrupt

Practices Act Investigation and Agree. Washington, DC: Retrieved April 10, 2012 from DOJ website:

http://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/2010/April/10-crm-360.html

28. U.S. Department of Justice. (February 11, 2009). Kellogg Brown & Root LLC Pleads Guilty to Foreign

Bribery Charges and Agrees to Pay $402 Million Criminal Fine. Washington, DC: Retrieved April 12,

2012 from the DOJ website: http://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/2009/February/09-crm-112.html

The Journal of Applied Business Research – November/December 2012 Volume 28, Number 6

1138 http://www.cluteinstitute.com/ © 2012 The Clute Institute

29. U.S. Department of Justice. (February 10, 2011). Tyson Foods Inc. Agrees to Pay $4 Million Criminal

Penalty to Resolve Foreign Bribery Allegations. Washington, DC: Retrieved April 29, 2012 from the DOJ

website: http://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/2011/February/11-crm-171.html

30. U.S. District Court- Southern District of Texas- Houston Division. (February 11, 2009). SEC vs.

Halliburton Company & KBR, Inc. Washington, DC: Retrieved April 12, 2012, from the SEC website:

http://www.sec.gov/litigation/complaints/2009/comp20897.pdf

31. U.S. Securities & Exchange Commission. (July 27, 2011). Administrative Proceeding: File No. 3-14490.”

Accounting & Auditing Enforcement. Release no. 3307. pgs. 1-2. Washington, DC: Retrieved April 29,

2012 from the SEC website: http://www.sec.gov/litigation/admin/2011/34-64978.pdf

32. U.S. Securities & Exchange Commission. (March 18, 2011). IBM to Pay $10 Million in Settled For FCPA

Enforcement Action. Accounting & Auditing Release No. 3254. Washington, DC: Retrieved April 18,

2012 from SEC website: http://www.sec.gov/litigation/litreleases /2011/lr21889.htm

33. U.S. Securities & Exchange Commission. (July 13, 2011). SEC Charges Armor Holdings, Inc. With FCPA

Violations in Connection With Sales to the United Nations. Washington, DC: Retrieved April 27, 2012,

from the SEC website: http://www.sec.gov/news/press/2011/2011-146.htm

34. U.S. Securities & Exchange Commission. (April 1, 2010). SEC Charges Daimler AG with Global Bribery.

Washington, DC: Retrieved April 10, 2012 from the SEC website:

http://www.sec.gov/news/press/2010/2010-51.htm

35. U.S. Securities & Exchange Commission. (July 27, 2010). SEC Charges General Electric and Two

Subsidiaries with FCPA Violations. Washington, DC: Retrieved April 17, 2012 from the SEC website:

http://www.sec.gov/news/press/2010/2010-133.htm

36. U.S. Securities & Exchange Commission. (July 27, 2011). SEC Charges Liquor Giant Diageo with FCPA

Violations. Washington, DC: Retrieved April 29, 2012, from the SEC website:

http://www.sec.gov/news/press/2011/2011-158.htm

37. U.S. Securities & Exchange Commission. (February 10, 2011). SEC Charges Tyson Foods with FCPA

Violations. Washington, DC: Retrieved April 29, 2012, from the SEC website:

http://www.sec.gov/news/press/2011/2011-42.htm

38. U.S. Securities & Exchange Commission. SEC Enforcement Actions: FCPA Cases. Washington D.C.:

Retrieved May 4, 2012, from the SEC website: http://www.sec.gov/spotlight/fcpa/fcpa-cases.shtml

39. U.S. Securities & Exchange Commission. (March 22, 2010). United States Securities & Exchange

Commission vs. Daimler AG. p. 2. Washington, DC: Retrieved April 10, 2012, from the SEC website:

http://www.sec.gov/litigation/complaints/2010/comp-pr2010-51.pdf

40. U.S. Securities & Exchange Commission. U.S. Securities & Exchange Commission vs. International

Business Machines Corporation: Complaint. p. 8. Washington, DC: Retrieved April 17, 2012, from the

SEC website: http://www.sec.gov/litigation/complaints/2011/comp21889.pdf

41. U.S. Senate. (2002). U.S. Senate Roll Call Votes 107

th

Congress- 2

nd

Session. Vote Summary.

Washington, DC: Retrieved March 27, 2012, from the U.S. Senate website:

http://www.senate.gov/legislative/LIS/roll_call_lists/roll_call_vote_cfm.cfm?congress=107&session=2&vo

te=00192

42. U.S. House of Representatives. “Final Vote Results for Roll Call 348” (Bill Title: Corporate and Auditing

Accountability & Responsibility Act). Washington, DC: Retrieved March 27, 2012, from the U.S. House

of Representatives website: http://clerk.house.gov/evs/2002/roll348.xml

43. United States of America Fifth Congress. (January 27, 1998). 1998 Amendments International Anti-Bribery

and Fair Competition Act of 1998. Washington, DC: Retrieved May, 4, 2012, from

http://www.justice.gov/criminal/ fraud/fcpa/docs/antibribe.pdf

The Journal of Applied Business Research – November/December 2012 Volume 28, Number 6

© 2012 The Clute Institute http://www.cluteinstitute.com/ 1139

APPENDIX A

This appendix serves as an update to cases involving companies that were previously in the news for

violating the FCPA. Although some of these companies were accused of committing bribery in the late-2000s, their

cases remained unsolved for years. The following presents any conclusions to those previously unfinished cases and

also discusses those companies that are regarded as “repeat violators.”

ABB, Ltd.

ABB Ltd, a Zurich, Switzerland-based energy company, was found guilty under the statutes of the FCPA

for their subsidiaries paying over $1 billion “in bribes to officials in Nigeria, Angola, and Kazakhstan between 1998

and 2003,” (Katz, 2004) in an effort to win rights to contracts to energy projects. In one of those cases, an ABB

manager in Angola (a country in Southern Africa), “doled out $21,600 in a brown paper bag to five officials of a

government owned oil company” (Katz, 2004). While this bribe is miniscule in comparison to the $1.1 billion paid

to secure business deals, it illustrates the great lengths the company went to secure business in foreign countries.

Although ABB was cooperative with a federal investigation by the SEC and the DOJ, the company was fined a total

of $16.4 million for their illegal acts (Cascini & DelFavero, 2008, p. 26).

As of September 30, 2010, the ABB case has been concluded. The SEC and the DOJ again fined ABB Inc.

and ABB Ltd. a total of $58.3 million. In this case, penalties were assessed with specific regard to ABB’s Network

Management business, located in Sugar Land, TX, which made “payments” to secure contracts in Mexico. Contracts

derived from these payments existed between 1997 and 2005. In addition, the corporation was found guilty for

bribes committed by its subsidiaries under the “U.N. Oil for Food Program in Iraq between 2000 and 2004” (ABB

Inc, 2010).

The company pled guilty “on one count of conspiracy to violate the FCPA and another count of violating

the anti-bribery provisions of the Act.” Nonetheless, as of September 2010, the company announced that it

implemented a “global comprehensive compliance and integrity program.” According to ABB, the DOJ proposed

that ABB’s compliance program may become “a benchmark for the industry” (ABB, 2010).

However, it must be noted that the company has been recognized by the DOJ and SEC for its extreme

willingness to cooperate with the authorities. Accordingly, the SEC and DOJ has allowed for ABB to conduct a

“review of its internal [compliance] processes,” as opposed to having a review performed by an external party

(ABB, 2010).

Nonetheless, the company is committed to move forward from this nearly 15-year period of

insubordination. According to Diane de Saint Victor, (ABB’s Head of Legal & Integrity, General Counsel &

Company Secretary), “ABB is committed to fostering a culture where integrity is woven into the fabric of

everything [they] do….[They] regularly evaluate [their] culture of integrity, and will continue raising the bar

relentlessly” (ABB, 2010).

While the conclusion to ABB’s cases didn’t occur until 2010, there is no evidence that the company has

committed any further acts of bribery since 2005. Millions of dollars of fines and years of scrutiny have forced the

company to develop a vision that includes honest business practices as a goal.

The Journal of Applied Business Research – November/December 2012 Volume 28, Number 6

1140 http://www.cluteinstitute.com/ © 2012 The Clute Institute

Company Revenue $ %

ABB Ltd 38 B NYD

Daimler AG $143.8 B* 0.6467%

Halliburton 24.8 B 2.3347%

Siemens AG 102.8 B 2.0428%

*Daimler's 2011 revenue is based on €106.54 x $1.35 average exchange rate for 2011

2.1 B

FCPA Violation Fines as a % of Revenue

2011

2011

2011

2011

Year

FCPA Payment $

NYD

93M

579 M

Table 3

Daimler AG (formerly Daimler-Chrysler)

In March 2006, Daimler AG, headquartered in Stuttgart, Baden-Wuttemberg, Germany, divulged to the

public that multiple employees made “improper payments’ in [various] foreign jurisdictions” (Cascini & DelFavero,

2008, p. 26) (Taub, 2006). Although Damiler AG is not technically a U.S. corporation, the company’s stock trades

in the United States as an American Depository Receipt. According to the SEC complaint, between 1998 and 2008,

Daimler AG and its subsidiaries “paid at total of at least $56 million in bribes to foreign government officials to

secure business in at least 22 countries in Asia, Africa, Eastern Europe, and the Middle East.” Daimler engaged in

these illegal transactions in excess of 200 times! Overall, the SEC asserted that that the company made over $90

million in illegal profits via the “tainted sales transactions” (SEC, April 2010).

According to Robert Khuzami, Director of the SEC’s Division of Enforcement, payment of illegal bribes

by Daimler was a “standard business practice.” In addition, Cheryl Scarboro, Chief of the SEC’s FCPA Unit,

indicated that the level of corruption at Daimler was widespread. The illegal activity involved multiple departments

including “sales, finance, legal, and internal audit” (SEC, April 2010).

With regard to specific subsidiaries, Mercedes-Benz Russia SAO (formerly DaimlerChrysler Automotive

Russia) (SAO), and The Export and Trade Finance GmbH (GmbH means a limited liability company) pleaded guilty

for violating the FCPA. For example, the Russian subsidiary admitted that they made illegal kickbacks to “Russian

federal and municipal officials to secure contracts.” The subsidiary confessed that they obtained the funds to be

used as bribes by overcharging their customers and remitting the superfluous monies to government officials. On the

other hand, the German subsidiary acknowledged that they offered bribes to government officials in Croatia to

“secure the sale of 210 fire trucks.” The DOJ ruling mandated that the Russian subsidiary pay fines of $27.26

million, while the German subsidiary paid a penalty of $29.12 million (DOJ, April 2010).

A third subsidiary was involved in the bribery scheme as well. Daimler North East Asia Ltd. (formerly

known as DaimlerChrylser China Ltd.) admitted that they offered payoffs to Chinese officials in the form of

commissions and/or gifts in an effort to secure the sale of vehicles to Chinese government clients. The DOJ did not

assign a monetary penalty in this case, but mandated that the corporation enter into a “deferred prosecution

agreement,” which required that Daimler AG establish an FCPA compliance program and have an “independent

compliance monitor for a three-year period” to monitor the program (DOJ, April 2010).

The SEC also indicated that the company had a fairly elaborate bribery scheme. For instance, Daimler AG

would offer “artificial discounts or rebates on sales contracts.” Instead of the company passing through these savings

to the customer (the government purchaser), Daimler re-directed the reported “money saved” to a foreign

government official. This type of process can be viewed as a bribe in disguise (SEC, April 2010).

In addition, Daimler AG was also involved in the U.N.’s Oil for Food program in Iraq. The company

admitted that they paid illegal kickbacks to Iraqi government officials in an effort to bolster vehicle sales (DOJ,

April 2010). Between 2001 and 2003, the company made “direct and indirect sales of motor vehicles and spare

parts under the U.N.’s Oil for Food Program.” Daimler admitted that during this time, they made payments to Iraqi

The Journal of Applied Business Research – November/December 2012 Volume 28, Number 6

© 2012 The Clute Institute http://www.cluteinstitute.com/ 1141

ministers in excess of $6 million (SEC, April 2010, p.2). Yet again, another corporation has taken advantage of the

U.N. Oil for Food Program and misused it to unethically enhance profitability.

With regard to the FCPA, the Department of Justice mandated that the corporation and its subsidiaries pay

over $93 million in penalties for violating “the books and records provisions of the FCPA and for conspiracy to

violate these provisions” (DOJ, April 2010).

In April 2010, the SEC also settled with the company for the civil violations for the Securities Act of 1934.

Thus, the settlement forced the company to “disgorge $91.4 million” in profits which was earned under illegal

pretenses. Under the Securities Act of 1934, the company was found to have violated Section 30A. In addition, the

company violated Section 13(b)(2)(A) and Section 13(b)(2)(B) of the Act (SEC, April 2010).

Shortly after the SEC and DOJ rulings, Dr. Dieter Zetsche, Chairman of Daimler AG, stated that the

executives and employees have “learned a lot” from the bribery scandals and “will continue do to everything [they]

can to maintain the highest compliance standards” (Censky, April 2010). Although the depth of the corruption at

Daimler AG was much greater than the author’s initially thought, the corporate culture at the conglomerate appears

to be finally moving in the right direction.

Halliburton

In an attempt to seek “favorable tax treatment for a liquefied natural gas facility,” Halliburton admitted that

one of the company’s acquirees may have “bribed Nigerian officials” (Katz, November 2004). The acquiree,

Kellogg Brown & Root (KBR), was accused of committing bribes between 1994 and 2004, and thus, was granted

permission by the Nigerian government to build a natural gas facility. The cash value of these construction contracts

was worth $6 billion (U.S. District Court-Southern District of Texas, 2009). Halliburton spun-off KBR in April

2007 (Clanton, 2007, pg. 1).

The SEC complained that KBR’s bribery scheme began as early as 1994, where company executives

considered the payment of bribes to the Nigerian government essential in order to be awarded business. The

company orchestrated the bribery plan by creating faux contracts with “two agents, one based in the United

Kingdom and one based in Japan.” The purpose of these agents was to hide the bribes and to redirect the funds to

the designated Nigerian officials. In total, the bribes paid by these “agents” amounted to $180 million (SEC,

February 2009).

In addition, the SEC criticized Halliburton for not having adequate internal controls to detect and avoid the

bribery from occurring. As a result of the entity concealing the bribes, the company’s records were rendered to be

flawed (SEC, February 2009). Accordingly, in February 2009, the SEC ordered KBR & Halliburton to repay the

$177 million in profits produced by the Nigerian bribes. The company was found to have violated Section 30A,

13(b)(5) and Rule 13b2-1 of the Securities and Exchange Act of 1934 (SEC, February 2009), which mandates that

companies cannot illegally influence a foreign official and must maintain accurate records (University of Cincinnati,

College of Law). The SEC also mandated that the company implement an FCPA compliance program and have an

independent monitor oversee the program (SEC, February 2009).

With regard to the FCPA, the DOJ criminally charged Kellogg Brown & Root LLC on “one count of

conspiring to violate the FCPA and four counts of violating the anti-bribery provisions of the FCPA.” The penalty

imposed by the DOJ amounted to $402 million (SEC, February 2009).

Nonetheless, although these crimes were committed by KBR, Halliburton agreed to pay for any fines

imposed by the SEC and/or DOJ as part of Halliburton and KBR’s spin-off agreement in 2006. The combined

settlement of $579 million was considered to be the largest payout for a FCPA violation in history (Grace, February

2009, pg B2). Accordingly, with regard to the Halliburton/KBR settlement, SEC Chairman Mary Schapiro released

the following statement: “Any company that seeks to put greed ahead of the law by making illegal payments to win

business should beware that we are working vigorously across borders to detect and punish illicit conduct” (DOJ,

February 2009).

The Journal of Applied Business Research – November/December 2012 Volume 28, Number 6

1142 http://www.cluteinstitute.com/ © 2012 The Clute Institute

This comment by Mary Schapiro’s and the mammoth fines imposed by the SEC and DOJ illustrates a much

more aggressive environment for corporate wrongdoers. Since this 2009 ruling, there have not been any further

reports of bribery occurring at either Halliburton or KBR.

Siemens AG

Siemens AG, the maker of electrical engineering and other electronic products, was accused of offering

bribes to Nigerian telecommunications ministers. The corporation had a major goal of securing highly lucrative

contracts for telecommunications equipment. Siemens committed bribery 77 times and paid a total of €12 million to

obtain these contracts (Cascini & DelFavero, 2008, pg. 29) (Crawford & Esterl, 2007, p A1).

However, the corruption at Siemens was much more widespread than had been originally believed. In

2008, the SEC purported that Siemens had paid bribes to obtain contracts in Mexico, Bangladesh, Israel, Iraq,

Argentina, Vietnam, Venezuela, China, and Russia. For example, Siemens was awarded the right to “design and

construct metro lines, power plants, refineries, and telecommunications networks,” as a result of the kickbacks

(SEC, December 2008).

Similar to the aforementioned FCPA violators, Siemens had devised a sophisticated technique to conceal

the bribe payments to foreign parties. The SEC alleged that the company made of over $1.7 billion in bribes and

“used numerous slush-funds, off-books accounts maintained at unconsolidated entities and a system of business

consultants and intermediaries to facilitate the corrupt payments. “ In other cases, the company was accused of

filling suitcases with cash and sending the luggage abroad to a foreign official (SEC, December 2008). In October

2007, the German courts had initially ruled that Siemens pay $290 million in penalties for the bribery scheme. At

the time, the company also spent over $500 million to establish a system to evaluate, detect, and prevent a corrupt

bribery system from occurring within the company (Ewing & Javers, 2007, p. 78). However, these costs would later

prove to only be the beginning of what would be very costly fines.

As a result of the unprecedented degree of corruption at Siemens, on December 15, 2008, the SEC ruled

that the multinational conglomerate had violated Sections 30A, 13(b)(2)(A), and 13(b)(2)(B) of the Securities and

Exchange Act of 1934. Accordingly, the SEC mandated that the company pay back $350 million of illegal profits

(SEC, December 2008). In addition, the DOJ slapped Siemens with a $450 million fine for criminally violating the

FCPA. The company was also required to pay an additional $569 million to the Officer of the Prosecutor General in

Munich, Germany (SEC, December 2008). Not only was the $800 million payout in fines to the U.S. Government a

record dollar amount for violating the FCPA, but in the aggregate (which includes the $500 million spent on an

internal investigation system in 2007), the bribery plot cost Siemens $2.1 billion!

Although the settlement for the corporation was determined by the end of 2008, it was not until December

2011, that the fate of six former executives of Siemens was decided. These six executives and two middlemen of

Siemens had paid over $100 million in kickbacks during the late 1990s to the Argentine government. The goal of

these illicit payments was to obtain a $1 billion contract to produce national identification cards for all citizens of the

country. The eight individuals were found guilty of “conspiring to violate the FCPA and the wire fraud statute,

engaging in money laundering, and committing wire-fraud.” The unique aspect to this particular ruling is that one

of these eight individuals found guilty was also a board member of the Argentinean division of Siemens. To date,

Siemens is the only case where a board member of a Fortune Global 50 company was found to have disobeyed the

FCPA (Bray, December 2011).