Transforming Schools Through Spiritual Leadership:

A Field Experiment

Peggy N. Malone

Louis W. Fry

Tarleton State University – Central Texas

1901 South Clear Creek Rd.

Killeen, TX 76549

254-519-5476

fry@tarleton.edu

Presented at the 2003 national meeting of the Academy of Management, Seattle Washington

Currently under review for publication at The American Educational Research Journal.

2

Transforming Schools Through Spiritual Leadership:

A Field Experiment

Abstract

Spiritual Leadership is a causal leadership model for organizational transformation (OT)

designed to create an intrinsically motivated, learning organization. Spiritual leadership theory

was developed within an intrinsic motivation model that incorporates vision, hope/faith, and

altruistic love, theories of workplace spirituality, and spiritual survival through calling and

membership. The purpose of spiritual leadership is to create vision and value congruence across

the strategic, empowered team, and individual levels and, ultimately, to foster higher levels of

organizational commitment and productivity. The purpose of this paper is to test and validate the

general casual model for spiritual leadership through an experimental design that initially

examined 229 employees from three elementary and one middle school. A one-year longitudinal

field experiment was then conducted with two of the original schools by means of an OT

visioning/ stakeholder analysis intervention performed in one school with another as a control.

Results revealed strong support for the model and the intervention, especially in terms of a

significant increase in organizational commitment. An action agenda for future research and

teacher and school employee training and development leading to increased teacher retention,

organizational commitment and productivity is then offered.

3

The Public School Transformation Challenge

As the public school system is challenged to meet a constantly changing list of

expectations and accountability, communities of learning in which students are able to think,

apply and extend their knowledge are becoming rare. It is in these schools that trust in the

educational process is found from an internal and external perspective. Mier (2000) argues that

the dominant paradigm for public schools, with its excessive reliance on standardized

curriculums and externally imposed standardized testing to measure, sort and rank schools and

children, is powered by a cynical distrust of public education. This is demonstrated through

constrained choices. By not trusting the public school system as a whole, we allow those farthest

removed from the schoolhouse to dictate policy that fundamentally changes the daily interactions

that take place within schools. “Nor do we trust in the extraordinary human penchant for learning

itself” (Mier, 2000). The challenge in today’s educational process is to develop an educational

delivery system model that encompasses the fluid aspects of society which schools encounter,

while producing achievement results certified by the public sector and capitalizing on the human

element of trust.

Modern capitalist democracies increasingly breed isolation, anomie, and discontent

(Hoyle & Slater, 2001). In Alexis de Tocqueville’s “Democracy in America” it is observed that

democracy tends to extremes, producing destructive imbalances in both individuals and

organizations. One of democracy’s principal imbalances has to do with the relationship between

self and others. Over time, democracy undermines our capacity to develop profound connections

with others. Tocqueville was convinced, that as individualism continued to grow, “each man

may be shut up in the solitude of his own heart.” Preoccupied more and more with their own

concerns and successes, Americans would increasingly let the government manage their general

affairs, giving it increasing power. Thus, the trust of community and the abdication of policy to

those not in the schoolhouse evolves. The accountability movement, at least as now being

implemented, also seems to be focusing our attention on things that reinforce the trend toward

more and more individualistic behavior and attitudes (Hoyle & Slater, 2001). Increasing pressure

for higher test scores is found at the local, state and national level. Mandated continuous

improvement and required scores for campus accountability ratings drive the educational system

4

without regard to the needs of students in the formulation of skills and resources critical to

perpetuating a connected, caring, and loving society of people.

Schools must develop a broader foundation for our students to meet the challenges of the

21

st

century. One of the most important tasks for educational leadership is to put altruistic love

at the center of the American educational vision. If we are to redress the imbalances in our

society caused by a growing individualism and mistrust, we must create schools that lay the

foundations for community, that give our children the experiences that will stimulate their desire

to be connected to other human beings in a common enterprise. (Hoyle & Slater, 2001).

Altruistic love, defined here as care, concern and appreciation for both self and others, is the

building block of this foundation. In our scramble to be globally competitive, in the ways that we

are implementing accountability, we are losing sight of this one ingredient that, if given its

proper place, is most likely to help us achieve our goals and reestablish trust in each other.

Caring leaders, it has been observed, “don’t inflict pain, they bear pain.” Schools without

love and happiness are misleading. The teachers are seen talking curriculum alignment and

student learning styles, the administrators are working the halls, the students appear to be on

task, the counselors are busy with students, the building is well maintained, and the athletic

teams are winning. But take a closer look. Are the administrators, counselors, teachers, and

parents sharing ideas about helping all children? Are expectations high for students and staff?

Are smiles frequent and compliments shared liberally? Are conversations positive? (Hoyle &

Slater, 2001). Americans want schools that teach students how to live, share, and serve others in

a world of anger, violence, poverty, and personal turmoil. A model of these standards is possible

through the establishment of trust among all stakeholders in the educational process.

Trust is essential and necessary (but not sufficient) for both altruistic love and effective

and innovative leadership. As America’s educational leaders are faced with the complex task of

educating an increasingly disconnected student population while demonstrating required

benchmarks of growth in achievement data, it is evident that a new direction must be forged.

Today’s successful leaders must combine heart, mind, body, and spirit to achieve new depths of

learning which actively involves all members of the community.

Recently, there has been increasing criticism about worrisome signs of deterioration and

decay throughout the U.S. public education system (Hoyle & Slater, 2001). Especially alarming

is the growing difficulty schools face in filling their annual quota of new recruits and the mass

5

exodus of early and mid-career teachers. The solutions to these problems go beyond issues of

extrinsic motivation such as pay and benefits. Rather it the primary challenge for public school

leaders to establish throughout the ranks the role of intrinsically motivated professional educator

esteemed for educating our children that has traditionally inspired teachers to serve. By

definition, professionals believe their chosen profession is valuable, even essential to society,

and they are proud to be a member of it. A major challenge for public education then is to create

a learning organizational paradigm within which the teacher’s professional commitment is also

translated into organizational commitment and productivity.

In this paper we examine school principals as strategic leaders within the context of a

central Texas school district. The purpose of this research is to determine if there is a relationship

between the qualities of spiritual leadership and teacher organizational commitment and

productivity. Spiritual Leadership is a causal leadership model for organizational transformation

(OT) designed to create an intrinsically motivated, learning organization. Spiritual leadership

theory incorporates intrinsic motivation through vision, hope/faith, and altruistic love, theories of

workplace spirituality, and spiritual survival through calling and membership. The purpose of

spiritual leadership is to create vision and value congruence across the strategic, empowered

team, and individual levels and, ultimately, to foster higher levels of organizational commitment

and productivity. In this paper we test spiritual leadership theory through an experimental design

that initially examined 229 employees from three elementary and one middle school to validate

the general casual model for spiritual leadership. A one-year longitudinal field experiment was

then conducted with two of the original schools by means of an OT visioning/ stakeholder

analysis intervention performed in one school with another as a control. Results revealed strong

support for the model and the intervention, especially in terms of a significant increase in

organizational commitment. Since past research has clearly shown that increased organizational

commitment increases motivation and reduces turnover (Mowday, Porter, and Steers, 1982;

Nyhan, 2000), an action agenda for future research and teacher and school employee training and

development leading to increased teacher retention, organizational commitment and productivity

is offered.

Organizational Transformation Through Spiritual Leadership

Organization transformation (OT), a recent extension of organizational development, seeks to

create massive changes in an organization’s orientation to its environment, vision, goals and

6

strategies, structures, processes, and organizational culture. Its purpose is to affect large-scale,

paradigm shifting change. “An organizational transformation usually results in new paradigms or

models for organizing and performing work. The overall goal of OT is to simultaneously

improve organizational effectiveness and individual well being (French, Bell, and Zawacki,

2000, p. vii).

Leaders attempting to initiate and implement organizational transformations face daunting

challenges, especially in gaining wide-spread acceptance of a new and challenging vision and the

need for often drastic and abrupt change of the organization’s culture (Cummins and Worley,

2001; Harvey and Brown, 2001). Although leadership has been a topic of interest for thousands

of years, scientific research in this area was only begun in the twentieth century. While space

limitations on this paper preclude a detailed review of the leadership literature, most definitions

of leadership share the common view that it involves influence among people who desire

significant changes, and that these changes reflect purposes shared by leaders and followers

(Daft, 2001).

There are almost as many definitions of leadership and approaches to leadership as there are

leaders, for our purpose we will use the definition and generic process of leadership developed

by Kouzes and Pozner (1987, 1993, 1999) - leadership is the art of mobilizing others to want to

struggle for shared aspirations. From their perspective leadership entails motivating followers by

creating a vision of a long-term challenging, desirable, compelling and different future. This

vision when combined with a sense of mission of who we are and what we do, establishes the

organization’s culture with its fundamental ethical system and core values. The ethical system

then establishes a moral imperative for right and wrong behavior which, when combined with

organizational goals and strategies, acts as a substitute (Kerr and Jermier, 1977) for traditional

bureaucratic structure (centralization, standardization and formalization) and, when coupled with

a powerful vision, provides the roadmap for the cultural change to the learning organizational

paradigm needed for organizational effectiveness in today’s chaotic organizational environments.

Thus, it is the act of creating a context and culture that influences followers to ardently desire,

mobilize, and struggle for a shared vision that defines the essence of motivating through

leadership.

7

The Learning Organization

A learning organization is one in which its employees are empowered to achieve a clearly

articulated organizational vision. Quality products and services that exceed expectations

characterize learning organizations. This new networked or learning organizational paradigm is

radically different from what has gone before: it is customer/client-obsessed, team-based, flat (in

structure), flexible (in capabilities), diverse (in personnel make-up) and networked (working with

many other organizations in a symbiotic relationship) in alliances with suppliers,

customers/clients and even competitors, and innovative, and global.

According to Peter Senge (1990, p. 3), its most famous proponent, learning organizations:

“…are where people continually expand their capacity to create the results they truly

desire, where new and expansive patterns of thinking are nurtured, where collective

aspiration is set free, and where people are continually learning to learn together.”

The five disciplines of the learning organization include: 1) personal leadership or

mastery, 2) “mental models” or socially constructed images that forms the organization reality

that influence how we understand the world and how we take action, 3) building a shared vision

that fosters genuine commitment rather than compliance so that people seek to excel and learn,

not because they are told to but because they want to, 4) team learning based on a collaborative

decision process that explores hidden assumptions through dialogue and seeks optimum

decisions through consensus. The fifth discipline, systems thinking, integrates the disciplines and

fuses them into a coherent body of theory and practice that enhances and creates synergy among

them.

The employees of learning organizations are characterized by being open and

generous, capable of thinking in-group teams, risk-takers with an innate ability to

motivate others. Furthermore, they must be able to abandon old alliances and establish

new ones, view honest mistakes as necessary to learning and ‘celebrate the noble effort’,

and exhibit a ‘do what it takes’ attitude versus a ‘not my job’ attitude. Its people are

empowered with committed leaders at the strategic, empowered team, and personal levels

that act as coaches in a “learning organization” constantly striving to listen, experiment,

improve, innovate, and create new leaders. For the learning organization, developing,

leading, motivating, organizing, and retaining people to be committed to organization’s

8

vision, goals, and culture is the major challenge in the new - especially organizations

whose primary purpose is to educate our children.

Spiritual Leadership

The purpose of this paper is to sharpen our focus on these issues through the lens of Fry’s

(2003; 2004) recent work on spiritual leadership theory to gain further insight into the nature,

process, and development of school transformation. Spiritual Leadership is a causal leadership

model for organizational transformation designed to create an intrinsically motivated, learning

organization. His theory of spiritual leadership is developed within an intrinsic motivation

model that incorporates vision, hope/faith, and altruistic love, theories of workplace spirituality,

and spiritual survival. The purpose of spiritual leadership is to tap into the fundamental needs of

both leader and follower for spiritual survival through calling and membership, to create vision

and value congruence across the individual, empowered team, and organization levels and,

ultimately, to foster higher levels of organizational commitment and productivity. Operationally,

spiritual leadership comprises the values, attitudes, and behaviors that are necessary to

intrinsically motivate one’s self and others so they have a sense of spiritual survival through

calling and membership (See Table 1 and Figures 2 & 3). This entails (Fry, 2003):

1. Creating a vision wherein leaders and followers experience a sense of calling in

that their life has meaning and makes a difference;

2. Establishing a social/organizational culture based on the values of altruistic love

whereby leaders and followers have a sense of membership, feel understood and

appreciated, and have genuine care, concern, and appreciation for BOTH self and

others.

Fry (2004) extended spiritual leadership theory by exploring the concept of positive

human health and well being through recent developments in workplace spirituality, character

ethics, positive psychology and spiritual leadership. He then argued that these areas provide a

consensus on the values, attitudes, and behaviors necessary for positive human health and well

being (See Table 2). He defined ethical well being as authentically living one’s values, attitudes,

and behavior from the inside out in creating a principled-center congruent with the universal,

consensus values inherent in spiritual leadership theory (Cashman, 1998; Covey, 1991; Fry,

2003). Ethical well-being is then seen as necessary but not sufficient for spiritual well-being

which, in addition to ethical well-being, incorporates transcendence of self in pursuit of a vision/

purpose/mission in service to key stakeholders to satisfy one’s need for spiritual survival through

9

calling and membership. He hypothesized that individuals practicing spiritual leadership at the

personal level will score high on both life satisfaction in terms of joy, peace and serenity and the

Ryff and Singer (2001) dimensions of well being. In other words, they will:

1. Experience greater psychological well being.

2. Have fewer problems related to physical health in terms of allostatic load

(cardiovascular disease, cognitive impairment, declines in physical functioning, and

mortality).

More specifically, they would have a high regard for one’s self and one’s past life, good-quality

relationship with others, a sense that life is purposeful and meaningful, the capacity to effectively

manage one’s surrounding world, the ability to follow inner convictions, and a sense of

continuing growth and self-realization.

To summarize the hypothesized relationships among the variables of the causal

model of spiritual leadership (See Figures 1, 2 and Table 2), “doing what it takes” through faith

in a clear, compelling vision produces a sense of calling - that part of spiritual survival that gives

one a sense of making a difference and therefore that one’s life has meaning. Vision, hope/faith

adds belief, conviction, trust, and action for performance of the work to achieve the vision.

Thus, spiritual leadership proposes that hope/faith in the organization’s vision keeps followers

looking forward to the future and provides the desire and positive expectation that fuels effort

through intrinsic motivation.

Altruistic love is also given from the organization and is received in turn from followers

in pursuit of a common vision that drives out and removes fears associated with worry, anger,

jealousy, selfishness, failure and guilt and gives one a sense of membership – that part of

spiritual survival that gives one an awareness of being understood and appreciated.

Thus, this intrinsic motivation cycle based on vision (performance), altruistic love (reward) and

hope/faith (effort) results in an increase in ones sense of spiritual survival (e.g. calling and

membership) and ultimately positive organizational outcomes such as increased:

1. Organizational commitment – People with a sense of calling and membership will

become attached, loyal to, and want to stay in organizations that have cultures based on

the values of altruistic love, and

2. Productivity and continuous improvement (Fairholm 1998) – People who have

hope/faith in the organization’s vision and who experience calling and membership

will “Do what it takes” in pursuit of the vision to continuously improve and be more

Productive.

10

The initial baseline survey data from two schools will be used as a basis for conducting a

field experiment using an action-planning organizational transformation/ professional

development (OT) change program (Harvey and Brown, 2001). The starting point for setting a

Spiritual Leadership Transformation (SLT) OT change program in motion is the establishment of

a baseline on our SLT variables to set the stage for further change efforts. After further

diagnosing problem areas associated with current employee well being, organizational

commitment and productivity, target issues for improvement are identified through a

vision/stakeholder effectiveness analysis and OD intervention strategies adopted to apply

techniques and technologies for change.

Study 1: Test of Causal Model

Participants and Procedures.

Survey data were collected from a sample of 229 employees in May 2001from three

elementary and one middle school of a central Texas independent school district (See Table 2

for sample demographics). All of the schools (except school 2) were selected for this study by

the district because it was believed they would score high on our spiritual leadership measures.

This represents about a 65 percent response rate from the total population of these schools.

Eighty-five percent of the respondents were teachers or paraprofessional (63% and 22%

respectively). Seventy percent had more than five years experience in their profession. Ninety

percent were female. Sixty-two percent were Caucasian, nineteen percent African American, and

ten percent Hispanic. The researchers administered anonymous questionnaires during regular

school hours. Nonrespondents had schedule conflicts or were not present on campus during

questionnaire administration. Investigation into the nature of nonrespondents gave no reason to

conclude that they differed from respondents. Also, ten percent of the school population were

randomly selected and personally interviewed to complement and validate the questionnaire

results.

Measures.

The three dimensions of spiritual leadership, two dimensions of spiritual survival, and

organizational commitment and productivity were measured using survey questions developed

especially for SLT research. The items were discussed with practitioners concerning their face

11

validity, and have been pretested and validated in other studies and samples (Fry, Vitucci &

Cedillo, 2004a, 2004b). The items measuring affective organizational commitment and

productivity were also developed and validated in earlier research (Nyhan, 2000). In addition, the

survey contained space for open-end comments to the question “ Please identify one or more

issues you feel need more attention.” These were content analyzed to validate the survey findings

to identify issues to be addressed during the visioning process intervention and. The

questionnaire utilized a 1-5 (from strongly disagree to strongly agree) response set. Scale scores

were computed by computing the average of the scale items. A list of items for each scale is

presented in Table 2. Overall means, standard deviations, correlations and the Cronbach’s alpha

for each scale are given in Table 3.

Study 1 Results

Ideally, organizations would want all their employees to agree or strongly agree (have

scale scores above 4) or report high levels for all SLT variables. Since three of the four schools

were chosen because they were felt to be among the best in the district, it was expected that they

would exhibit relatively high levels of spiritual leadership. Using quintiles to discern level of

agreement, results revealed high levels (over 80% agree) of meaning/calling (90.3% agree;

mean=4.48), moderately high (between 60% and 80%) levels of hope/faith (75.3% agree;

mean=4.26) and organizational productivity (66.1% agree; mean=4.03), moderate (between 40%

and 60%) levels of vision (57.3% agree; mean=3.98), altruistic love (56.4% agree; mean=3.84),

membership (57.7% agree; mean=3.83), and moderately low (between 20% and 40%) levels of

organizational commitment (25.6% agree; mean=3.45). A one-way ANOVA revealed only two

significant differences for the seven SLT variables across the four schools. School two

(elementary) reported significantly lower on vision (35.5% mean = 3.59) and Altruistic love

(25.8%; mean = 3.32) than the other schools.

A content analysis of the open-ended comments reinforced the moderate and moderately

low findings for vision and altruistic love/membership. The most often mentioned issues across

schools concerned the need for 1) better staff morale, 2) Equal treatment of all employees, 3)

better communication, 4) More staff praise, and 5) better knowledge of the campus

vision/mission.

12

Test of SLT Causal Model. We used the AMOS 4.0 SEM SPSS program with maximum

likelihood estimation to test the Spiritual Leadership Theory causal model. One of the most

rigorous methodological approaches in testing the validity of factor structures is the use of

confirmatory (i.e. theory driven) factor analysis (CFA) within the framework of structural

equation modeling (Byrne, 2001). Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) is particularly valuable

in inferential data analysis and hypothesis testing. It differs from common and components

(exploratory) factor analysis in that SEM takes a confirmatory approach to multivariate data

analysis; that is, the pattern of interrelationships among the spiritual leadership constructs is

specified a priori and grounded in theory.

SEM is more versatile than most other multivariate techniques because it allows for

simultaneous, multiple dependent relationships between dependent and independent variables.

That is, initially dependent variables can be used as independent variables in subsequent

analyses. For example, in the SLT model calling is a dependent variable for vision but is an

independent variable in its defined relationship with organizational commitment and

productivity. SEM uses two types of variables: latent and manifest. Latent variables are vision,

Altruistic love, hope/faith, calling, membership, organizational commitment and productivity.

The manifest variables are measured by the survey questions associated with each latent variable

(see Table2). The structural model depicts the linkages between the manifest and latent

constructs. In AMOS 4.0 these relationships are depicted graphically as path diagrams and then

converted into structural equations.

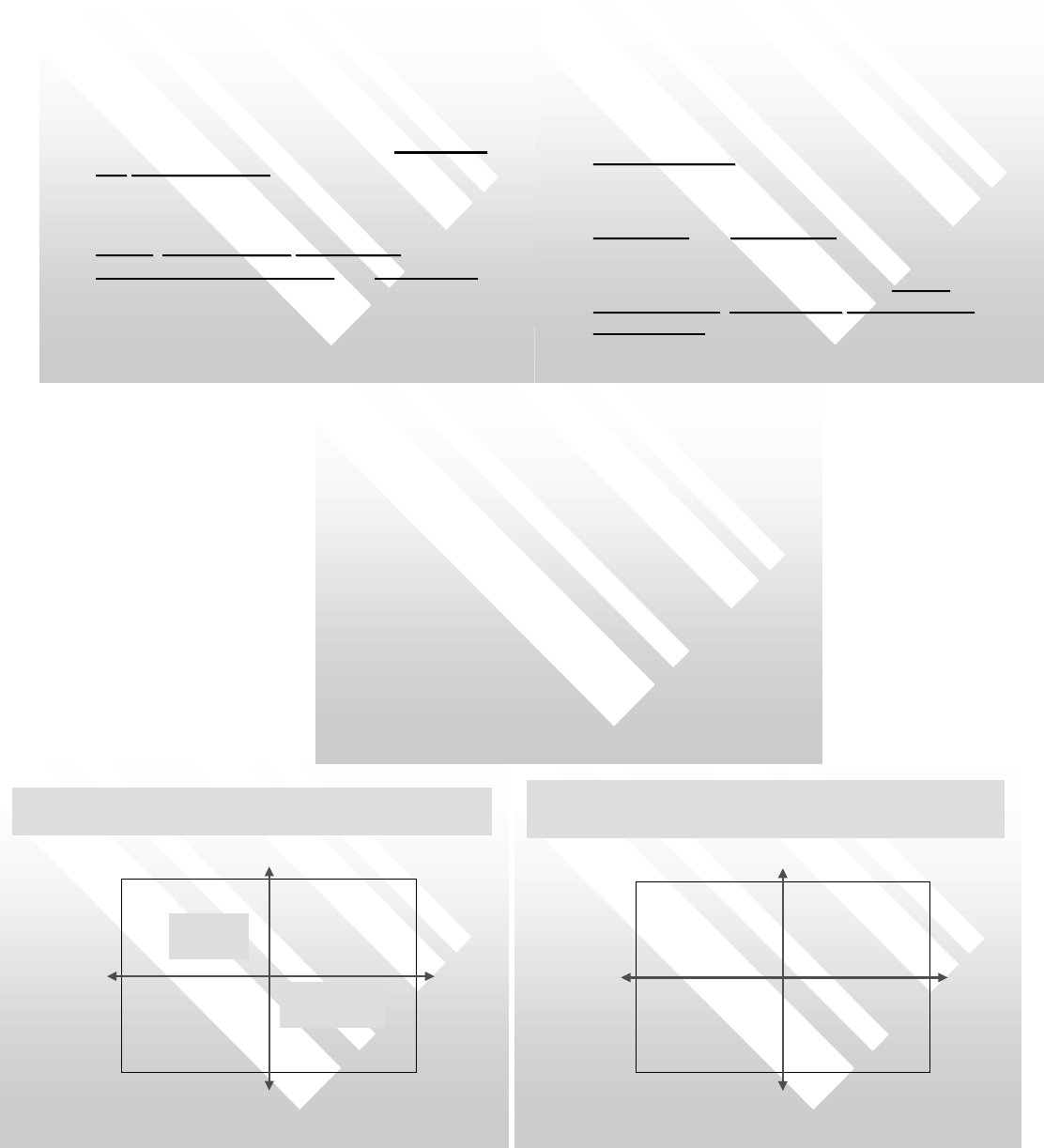

Figure 3 Shows the hypothesized SLT school causal model for this study. This model is

nonrecursive in that intrinsic motivation theory has feedback loops (between vision and altruistic

love and from vision to altruistic love to hope/faith and back to vision). For this model to be

identified (Bollen, 1989a) we must specify one of the loop parameters. We chose to specify the

vision altruistic love path common to both loops. A multiple regression analysis was run

on Altruistic love with Hope/Faith and Vision as predictors. The beta for the Vision to Altruistic

love path was .72. This value was then used to gain model identification. Figure 4 gives the

simplified model without the item results using the initial school data. Overall the model shows a

very good fit with the overall chi-square for the hypothesized model using the maximum

likelihood estimation method is 1112.732 (486 d.f; p < .001). The goodness of fit was measured

using three commonly used fit indices: The Bentler-Bonet (1980) normed fit index (NFI), the

13

Bollen (1989b) incremental fit index (IFI), and the comparative fit index (CFI; Bentler, 1990) to

compare the chi-square values of the null and hypothesized models using the degrees of freedom

from both to take into account the impact of sample size. A value greater than .90 is considered

acceptable. All fit indices indicate good to superior fit for this model (Hu & Bentler, 1995;

Mulaik et al., 1989). For this model, the NFI is .961; the IFI is .978; and the CFI is .978.

Parameter estimates reflect the extent of the relationship between manifest and latent

variables. For ease of interpretation the error and scale item parameter estimates are omitted

relative to the standardized path coefficients for the model’s latent variables in Figure 6.

Standardized path coefficients are by the arrows and the variance explained by the model for

each latent variable is given at the above right for each latent variable. As shown in Figure 4, all

standardized path coefficients in the hypothesized causal model are, as SLT predicted,

positive and significant with the explained variances of .80 for organizational commitment

and .29 for productivity.

Common Method Variance Issues

Common method variance (CMV) may be an issue for studies where data for the

independent and dependent variable are obtained from a single source. In order to determine if

the statistical and practical significance of any predictor variables have been influenced by CMV,

Lindell and Whitney (2001) advocate the introduction of a marker variable analysis that allows

for adjustment of observed variable correlations for CMV contamination by a single unmeasured

factor that has an equal effect on all variables. However, marker variable analysis is most

appropriate for research on simple independent- dependent variable relationships. SEM is more

flexible than marker variable analysis because it is capable of testing unrestricted method

variance (UMV) causal mode since SEM allows the error terms to be intercorrelated without

being fixed or constrained as in CMV. The AMOS 4.0 program has a modification indices (MI)

option that allows one to examine all potential error term correlations and determine the changes

in parameter and chi-square values. MI analysis for our data revealed the parameter changes due

to latent variable error correlation to be less than .10. Also, Crampton and Wagner (1994)

demonstrate that CMV effects seem to have been over stated, especially for studies such as this

one that use self assessment of group performance with role and organizational characteristics,

14

job scope, and leader traits. We therefore conclude that there is little impact on our data due to

CMV.

Study 2: Field Experiment

Participants and Procedures

Schools one and two were selected for our field experiment. Both were elementary pre-

kindergarten to third grade schools, were adjacent to on another geographically and have similar

student and parent demographics. School one is larger with approximately 85 to 60 full time

employees relative to school one. The initial and final survey demographics for both schools are

given in Figure 5. No differences in responses to the SLT variables were found within schools

showing that each school spoke as one regard their leaders, spiritual survival, and organizational

outcomes.

Field Experiment Intervention

For our sample, further diagnosing problem areas associated with current organizational

commitment is needed. Then target issues for improvement should be identified and

Organizational Design (OD) strategies adopted to apply techniques and technologies for change.

The starting point for setting a change program in motion is the definition of a total change

strategy. “An OD strategy may be defined as the plan for relating and integrating the different

organizational improvement activities engaged in over a period of time to accomplish objectives

(Harvey and Brown, 2001, p.216).”The overall purpose or objective of the OD change effort is to

develop stronger value congruence across the strategic, empowered team, and individual levels

through stronger linkages among the theory variables (i.e. increase the percentage of respondents

who agree or strongly agree that the Qualities of Spiritual Leadership are significant factors

influencing organizational commitment and productivity in the campus environment

After the initial baseline “snapshot” of the spiritual condition of the organization is

completed, a vision/stakeholder effectiveness analysis intervention is conducted. School One’s

site-based strategic team completed the initial draft. This analysis then becomes the input to a

linking pin process that was repeated at the grade level where it and the initial survey results

become input for top down/bottom up dialogue. Figure 5 gives school 1’s consensus

vision/purpose/mission/statements, the values it views as central to meeting or exceeding key

15

stakeholder expectations, a high power/high importance stakeholder map, and stakeholder

expectations with key issues. Inputs from all areas of the school operation are evident

in the school mission statement. During the creation of the school mission statement the

custodial staff requested that the word “clean” be inserted to accurately depict their contribution

to the environment.

The main issue that was targeted by school one for immediate attention was that of better

leadership/management of its parent stakeholder group. Out of this came several initiatives

including a parent survey, a parent information book for each grade with both student and parent

expectations, and mandatory parent/student orientations by grade at the beginning of the school

year.

Study 2 Results

The final survey was administered in May 2002 to both School One and our control

(School Two). Summaries of our results are given in Figure 6. Figure 6 gives the scale average

for all variables (initial and final in the lower right hand corner) with bar graphs depicting the

dispersion for the seven spiritual leadership variables (SLT) For School One and School Two.

The bar graphs depict the dispersion or range of responses. Scale responses between 1.00 and

2.99 represent Disagree. Neither is the percentage of respondents with an average scale value

between 3-3.99. The Agree percentage represents scale values between 4.00 and 5.00. Ideally,

organizations would want all their employees have high average scale scores (above 4) and

report high (above 80%) percentage levels of agree for all SLT variables. Moderate or low levels

on the theory variables indicate areas for possible intervention.

The most obvious result is that conditions deteriorated dramatically at school Two,

thereby limiting its usefulness as a control for our field experiment. Initially vision and altruistic

love were significantly lower at school 2. The final survey revealed that all seven SLT variables

were significantly lower for school 2. For school two averages on all but altruistic love dropped

significantly from the initial to the final survey. However, Even though not significant, even for

altruistic love, the percentage of respondents agreeing that the organization showed care, concern

and appreciation for them dropped from 24% to 11% while the percent of respondents

disagreeing rose from 29 to 62 percent. Open-ended survey comments and personal

conversations with people familiar with the situation revealed that both leadership and personal

16

issues between the administration and teachers had led to a very intimidating, conflict ridden

environment during the time between the two surveys.

In contrast, School One saw no significant decreases in any of the SLT variables with all

averages on SLT variables above four and with agree responses ranging 67% for productivity to

90% for calling. Altruistic love significantly increased from a 3.9 to 4.5 average level. Most

importantly the average for organizational commitment rose significantly rose from 3.5 to 4.3.

Also the agree percentage dramatically increased from 25% to 78% with the “bubble” and

disagree groups dropping 42% and 11% respectively. This finding is especially encouraging

since past research has clearly shown that increased organizational commitment strengthens

motivation and reduces turnover (Mowday, Porter, and Steers, 1982) – a major an ongoing

problem in our public schools

DISCUSSION

A commitment to excellence and the sustaining impact of the initial work completed in

the spiritual leadership theory at School 1 is evidenced in the 2002-2003 and 2003-2004

Academic Excellence Indicator System report required by Texas Education Code as the

accountability system for public education in Texas. The relationships that have been

established and the ongoing dialogue with all campus stakeholders built a foundation of

appreciative inquiry (Bushe, 1999). The principal at school one stated, “Everything we did as a

campus was a result of the campus mission and values which was a direct result of our work with

the spiritual leadership theory.” (Judy Tyson, personal communication, June 16, 2004).

In May, 2003 the Texas Assessment of Academic Skills (TAKS) for School one revealed

that 100 % of the Hispanic population at the school passed both the reading and math portion of

the test. The Hispanic population accounted for 15.4% of the student population. The White

population, which constituted 30.6% of the population, has a pass rate of 100% also in the areas

of reading and math. African American students comprised 48.2% of the school population and

posted a pass rate of 95.3 % on the math test. The pass rate for African American students in the

area of reading was 90.2% of the students. These areas indicate a very high level of content

mastery. An area of needed growth for 2002-2003 is Economically Disadvantaged students with

66.2% of the students passing the reading and math tests.

In May, 2004 the standards for passing the TAKS test increased, and the results for

School 1 continued to be strong. No major changes in ethnic distribution of the student

17

population occurred from testing cycles 2003 to 2004. In math the pass rate for Hispanic student

group was 97%, White student group 100%, and African American student group 88%. Reading

scores were 90% or above in all three ethnic groups. A very large increase was achieved in

Economically Disadvantaged students with 88% passing the math test and 99% passing the

reading test.

This accountability data continues to suggest that the time and energy invested in the

spiritual leadership theory, articulation of the campus mission, values and stakeholder

expectations, coupled with the dynamic campus action plan to address parent stakeholder issues

is the direction that campuses should move toward to meet the continuous societal challenges

placed on our schools and to regain the trust of the public. The role of the campus principal is

pivotal in this process for implementation of the spiritual leadership paradigm. It is through

spiritual leadership that we will be able to respond to all persons involved in the school

community regardless of their role.

It is the principal that is the pivotal point for communication and decision-making in the

school campus. The establishment of trust is facilitated from the principal. Trust can be viewed

from both an internal and external organizational perspective (Nyhan, 2000). Commitment to an

organization is built through trust. In today’s society our school districts operate from a top down

model of communication and decision-making often negating the pivotal role of the campus

principal. This must end in order to meet the challenges of the 21

st

century. The development of

a trusted educational delivery system that produces the required achievement results is critical to

the perpetuation of a democratic society. Spiritual leadership is a mechanism for establishing a

trusted educational system. Through Spiritual Leadership the components of vision, hope/faith,

and altruistic love impact organizational commitment and productivity internally and externally

throughout all levels of the organization. This process is regenerative while building a

foundation for continuous improvement individually and collectively.

CONCLUSION

This study should be expanded to capitalize on the promise of a sustained approach to

improvement in today’s arena of constrained fiscal resources and increased demand for

excellence in education. Of particular interest is in our findings is the moderately high level of

“neither” for organizational commitment. “Neither” responses can be view as being on the fence

or “bubble” in that they have the potential of being moved to the “Agree” category if

18

organizational development interventions are initiated and successful. It appears that our

vision/stakeholder effectiveness analysis intervention holds great promise in this regard. Since

past research has clearly shown that increased organizational commitment strengthens

motivation and reduces turnover (Mowday, Porter, and Steers, 1982), spiritual leadership theory

and its initial vision/stakeholder effectiveness process as an appreciative inquiry intervention

holds promise as an action agenda for future school research and organizational development and

transformation. As a next step, a study of thirty or more schools selected on the basis of high and

low test scores to test for differences in spiritual leadership seems called for.

The visioning process used here leading to increased teacher motivation, performance,

organizational commitment and ultimately teacher retention is based on appreciative inquiry

which, like Spiritual Leadership, focuses on identifying and addressing key stakeholder issues,

discovering what works well, why it works well, and how success can be extended throughout

the organization. Thus, it is both the vision and the process for developing this vision that creates

the energy to drive change throughout the organization (Bushe, 1999; Johnson and Leavitt,

2001). Appreciative Inquiry is premised on three basic assumptions. The first critical assumption

is that organizations are responsive to positive thought and positive knowledge. A second key

assumption is that it is both the image of the future, and the process for creating that image that

creates the energy to drive change throughout the organization. By engaging employees in a

dialogue about what works well based on their own experiences, employees notice that there is

much that works reasonably well already allowing change to be possible. Lastly, Appreciative

Inquiry is based on a belief in the power of affirmations; if people can envision what they want,

there is a better chance of it happening. Traditional approaches to problem solving are, by

definition, a way of seeing the world as a glass half empty. The Appreciative Inquiry is an

alternative process to bring about organizational change by looking at the glass as half full. This

approach is suited to organizations that seek to be collaborative, inclusive, and genuinely caring

for both the people within the organization and those they serve. By using an Appreciative

Inquiry approach, organizations can discover, understand, and learn from success, while creating

new images for the future (Leavitt and Johnson, 2001).

Research on several fronts must be conducted to establish the validity of spiritual

leadership theory as a foundation for an action agenda for organizational transformation. First,

the conceptual distinction between spiritual leadership theory variables and other leadership

19

theories and constructs must be refined. To date, these to have been confounded under such

constructs as encouraging the heart, stewardship, charisma, emotional intelligence,

transformational, authentic, and servant leadership. Second, research is just beginning on the

qualities spiritual leadership detailed in Table 1, especially as it relates to the values of spiritual

leadership. Value based leaders articulate a vision of a better future to energize extraordinary

follower motivation, commitment and performance by appealing to subordinates’ values,

enhancing their self efficacy, and making their self-worth contingent on their contribution to the

leaders’ mission and the collective vision (House and Shamir, 1993). Empirical evidence from

over 50 studies demonstrates that value based leader behavior has powerful effects on follower

motivation and work unit performance, with effect sizes generally above .50 (Bass and Aviolo,

1994; House & Shamir, 1993). Our results support this general finding, signaling the need for

more research in this area. Third, although our control group did not remain in control, the fact

that our spiritual leadership measure picked up the precipitous decline in all study variables for

school 2 - as confirmed in follow-up interviews - lends support for the discriminate validity of

our measures.

Fourth, Fry’s (2004) extension of spiritual leadership theory for psychological well-being

and positive human health should be tested for faculty and staff in schools. He defined ethical

well-being as authentically living one’s values, attitudes, and behavior from the inside-out in

creating a principled-center congruent with the universal, consensus values inherent in spiritual

leadership. Ethical well-being is then seen as necessary but not sufficient for spiritual well-being

which, in addition to ethical well-being, incorporates transcendence of self in pursuit of a vision/

purpose/mission in service to key stakeholders to satisfy one’s need for spiritual survival through

calling and membership. Therefore, it is hypothesized that individuals practicing and

experiencing spiritual leadership at the personal level will score high on both life satisfaction in

terms of joy, peace and serenity and the Ryff and Singer (2001) dimensions of well-being

discussed earlier. In other words, they will:

1. Experience greater psychological well-being in terms having a high regard for one’s

self and one’s past life, good-quality relationships with others, a sense that life is

purposeful and meaningful, the capacity to effectively manage one’s surrounding

world, the ability to follow inner convictions, and a sense of continuing growth and

self-realization.

20

2. Have fewer problems related to physical health in terms of allostatic load

(cardiovascular disease, cognitive impairment, declines in physical

functioning, and mortality).

Finally, the general issues relating to workplace spirituality research outlined by

Giacalone, Jurkiewicz, and Fry (2004) need to be explored and resolved for schools.

Building on the charge in The Handbook of Workplace Spirituality and Organizational

Performance that a scientific, data-based approach to workplace spirituality was

warranted and necessary, they identified three critical issues to be addressed: levels of

conceptual analysis, conceptual distinctions and measurement foci, and clarification of

the relationship between criterion variables. Giacalone et. al. (2004) argue that spiritual

leadership theory holds promise as a workplace spirituality paradigm in this regard. Our

study provides initial support for this promise, not only in regard to the critical issues

they raise but also in terms of the reconciliation of human well-being with performance

excellence through vision, hope/faith, and altruistic love.

21

References

Bass, B. M., & Avolio, B. J. (1994). Improving organizational effectiveness through

transformational leadership. Thousand Oaks California: Sage.

Bentler, P.M. (1990). “Comparative fit indexes in structural models.” Psychological

Bulletin, 107, 238-246.

Bentler, P. M. and Bonett, D. G. (1980). “Significance tests and goodness of fit in the

analysis of covariance structures.” Psychological Bulletin, 88, 588-606.

Bollen, K.A. (1989a). Structural Equations with Latent Variables. New York: Wiley.

Bollen, K.A. (1989b). “A new incremental fit index for general structure equation

models.” Sociological Methods and Research, 14, 155-163.

Bushe, G. R. (1999). “Advances in Apreciative inquiry as an organization development

Intervention.” Organization Development Journal. 17,2, 61-68.

Byrne, B.M. (2001). “Structural equation modeling with AMOS, EQS, and LISREL:

Comparative approaches to testing for the factorial validity of a measuring

instrument.” International Journal of Testing, 1, 55-86.

Cashman, K. (1998). Leadership from the inside out. Provo, UT: Executive Excellence

Publishing.

Covey, S.R. (1991). Principle-centered leadership. New York: Fireside/Simon &

Schuster.

Crampton, S. M. & Wagner III, J. A. (1994). “Percept-percept inflation in

microorganizational research: An investigation of prevalence and effect.” Journal of

Applied Psychology. 79,1, 67-76.

Cummins, T.G. & Worley, C.G. (2001). Organizational development and change. (7

th

edition). South-Western College Publishing.

Daft, R. L. (2001). The leadership experience. Fort Worth: Harcourt College Publishers.

de Tocqueville, A. (1969). Democracy in America. Garden City, NY: Anchor

Books.

Fairholm, G.W. (1998a). Perspectives on leadership: From the science of management

to its spiritual heart. Westport, CT: Preager.

22

French, W. L., Bell, C. B. & Zawacki, R. A. (2000). Organziational Development and

Transformation. Boston: Irwin-McGraw-Hill.

Fry, L. W. (2003). “Toward a theory of spiritual leadership.” The Leadership Quarterly, 14, 693-

727.

Fry, L. W. (2004). “Toward a theory of ethical and spiritual well-being and corporate social

responsibility through spiritual leadership.” Forthcoming in Giacalone, R.A. and Jurkiewicz,

C.L., (Eds). Positive Psychology in Business Ethics and Corporate Responsibility.

Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing. http://www.tarleton.edu/~fry/SLT&Ethics.rtf

Fry L.W. & Vitucci S. & Cedillo, M. (2004a). “Transforming the Army through spiritual

leadership.” Paper presented at the March, 2004 meeting of The International Academy of

Business Disciplines, San Antonio, Texas. Also accepted pending revision for publication.

(Spring 2005). The Leadership Quarterly’s Special Issue on Spiritual Leadership.

http://www.tarleton.edu/~fry/resources.html

Fry, L.W. & Vitucci, S. and Cedillo. M. (2004b). “Transforming city government through

spiritual leadership.” Working paper. http://www.tarleton.edu/~fry/resources.html

Giacalone, R.A. & Jurkiewicz, C.L. (2003). “Toward a science of workplace spirituality.”

In R.A. Giacalone, & C.L. Jurkiewicz (Eds.), Handbook of workplace spirituality and

organizational performance (pp. 3-28). New York: M.E. Sharp.

Giacalone, R.A., Jurkiewicz, C.L., and Fry, L.W. (2004). “From Advocacy to

The Next Steps in Workplace Spirituality Research.” In R. Paloutzian, Ed.,

Handbook of Psychology and Religion. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Harvey, D. & Brown, D. (2001). An experimental approach to organizational

development. (6

th

Edition). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

House, R. J., & Shamir, B. (1993). “Toward the integration of transformational,

charismatic, and visionary theories.” In M. Chemmers & R. Ayman (Eds.)

Leadership theory and research: Perspectives and directions. (pp. 81-107).

Orlando Fl: Academic Press.

Hoyle, J. R. & Slater, R.O. (2001). “Love, happiness, and America’s schools: The role of

educational leadership in the 21

st

century.” Phi Delta Kappan. 82, 790-794.

Hu, L.T. & Bentler, P.M. (1995). “Evaluating model fit.” In R.H. Hoyle (Ed.), Structural

Equation modeling: Concepts, issues and applications, 76-99. Thousand Oaks, CA:

23

Sage.

Johnson, G. & Leavitt, W. (2001). “Building on success: Transforming organizations

through appreciative inquiry.” Public Personnel Management. 30, 1 129-136.

Kerr, S. & Jermier, J. M. (1977). “Substitutes for leadership: Their meaning and

measurement.” Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 22, 375-403.

Kouzes, J. M. & Pozner, B. Z. (1993). Credibility. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass

Publishers.

Kouzes, J. M. & Pozner, B. Z. (1999). Encouraging The Heart. San Francisco: Jossey-

Bass Publishers.

Kouzes, J. M. & Pozner, B. Z. (1987). The Leadership Challenge. San: Francisco: Jossey-

Bass Publishers.

Lindell, M. K. & Whitney, D. J. (2001). “Accounting for common method variance in

cross-sectional research designs.” Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 1, 114-121.

Mier, D. (2002). In Schools We Trust: Creating Communities of Learning in an Era of

Testing and Standardization. Great Malvern, Worcestershire: Beacon Books.

Mowday, R., Porter, L. W. & Steers, R. M. (1982). Employee-Organization Linkages.

New York: Academic Press.

Muliak, S.A., James, L.R., Alstine, J.V., Bennet, N., Ling, S. & Stillwell, C.D. (1989).

“Evaluation of Goodness of fit for Structural Equation Models” Psychological

Bulletin, 105, 430-445.

Nyhan, R. C. (2000). “Changing the paradigm: Trust and its role in public sector

organizations.” American Review of Public Administration, 30(1). 87-109.

Ryff, C.D. & Singer, B. (2001). “From social structure to biology: Integrative science in

pursuit of human health and well-being.” Handbook of Positive Psychology. C.R.

Snyder and S.J. Lopez. Oxford: University Press..

Senge, P. M. (1990). The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning

Organization. New York: Doubleday Books, Incorporated.

Spreitzer, G. (1996). “Social structural characteristics of psychological empowerment.”

Academy of Management Journal, 39, 2, 483-504.

24

Figure 1. Causal model of spiritual leadership

Effort

(Hope/Faith)

Works

Calling

Make a Difference

Life Has Meaning

Organizational Commitment

Productivity

Performance

(Vision)

Membership

Be Understood

Be Appreciated

Reward

(Altruistic

Love)

L

eader Values, Attitudes &

B

ehaviors

Follower Needs for

S

piritual Survival

Organizational Outcomes

25

Table 2. Qualities of spiritual leadership

Vision Altruistic Love Hope/Faith

Broad Appeal to Key Stakeholders

Trust/Loyalty

Endurance

Defines the Destination and Journey Forgiveness/Acceptance/

Gratitude

Perseverance

Reflects High Ideals Integrity Do What It Takes

Encourages Hope/Faith Honesty Stretch Goals

Establishes Standard of Excellence Courage Expectation of Reward/Victory

Humility Excellence

Kindness

Compassion

Patience/Meekness/

Endurance

TABLE 2

Survey Questions

Vision – describes the organization’s journey and why we are taking it; defines who we are

and what we do.

1. I understand and am committed to my organization’s vision. ____

2. My workgroup has a vision statement that brings out the best in me. ____

3. My organization’s vision inspires my best performance. ____

4. I have faith in my organization’s vision for its employees. ____

5. My organization’s vision is clear and compelling to me. ____

Hope/Faith- the assurance of things hoped for, the conviction that the organization’s

vision/ purpose/ mission will be fulfilled.

1. I have faith in my organization and I am willing to “do whatever it takes” to

insure that it accomplishes its mission. ____

2. I persevere and exert extra effort to help my organization succeed because I

have faith in what it stands for. ____

3. I always do my best in my work because I have faith in my organization and

its leaders. ____

4. I set challenging goals for my work because I have faith in my organization

and want us to succeed. ____

5. I demonstrate my faith in my organization and its mission by doing everything

I can to help us succeed. ____

Altruistic Love - a sense of wholeness, harmony, and well-being produced through care,

concern, and appreciation for both self and others.

1. My organization really cares about its people. ____

2. My organization is kind and considerate toward its workers, and when

they are suffering, wants to do something about it. ____

3. The leaders in my organization “walk the walk” as well as “talk the talk”. ____

4. My organization is trustworthy and loyal to its employees. ____

5. My organization does not punish honest mistakes. ____

6. The leaders in my organization are honest and without false pride. ____

7. The leaders in my organization have the courage to stand up

for their people. ____

Meaning/Calling -

a sense that one’s life has meaning and makes a difference.

1. The work I do is very important to me. ____

2. My job activities are personally meaningful to me. ____

3. The work I do is meaningful to me. ____

4. The work I do makes a difference in people’s lives. ____

27

Membership - a sense that one is understood and appreciated.

1. I feel my organization understands my concerns. ____

2. I feel my organization appreciates me, and my work. ____

3. I feel highly regarded by my leadership. ____

4. I feel I am valued as a person in my job. ____

5. I feel my organization demonstrates respect for me, and my work. ____

Organizational Commitment - the degree of loyalty or attachment to the organization.

1. I do not feel like “part of the family” in this organization. ____

2. I would be very happy to spend the rest of my career with this organization. ____

3. I talk up this organization to my friends as a great place to work for. ____

4. I really feel as if my organization’s problems are my own. ____

Productivity - efficiency in producing results, benefits, or profits.

1. Everyone is busy in my department/grade; there is little idle time. ____

2. In my department, work quality is a high priority for all workers. ____

3. In my department, everyone gives his/her best efforts. ____

28

TABLE 3

Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations Among Study 1 Variables

a

Variable Mean s.d 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7.

1. Vision 3.98 0.72

.89

2. Altruistic Love 3.84 0.84 .72

.93

3. Hope/Faith 4.26 0.61 .79 .69

.86

4. Meaning/Calling 4.48 0.56 .58 .40 .61

.86

5. Membership 3.83 0.90 .70 .82 .65 .38

.93

6. Organizational

Commitment

3.45 0.58 .54 .49 .52 .27 .44

.70

7. Productivity 4.03 0.82 .47 .41 .44 .38 .41 .28

.79

a

n = 229; All correlations are significant at p < .01. Scale reliabilities are on the diagonal in

boldface

29

Figure 2. Spiritual leadership as intrinsic motivation through hope/faith, and altruistic love

Empowered

Teams

Make a difference

Life has meaning

Organizational Commitment

&&

Productivity

Strategic

Leaders

Be Understood

Be Appreciated

Team

Members

Effort/Works

• Endurance

• Perseverance

• Do What It

Takes

•

Stretch Goals

Learning

Oii

• Broad Appeal to

Stakeholders

•

Defines the Destination

&

Journey

•

Reflects High

Id l

•

Encourages

H/Fih

• Establishes Standard o

f

Excellence

Reward

•Trust/Loyalty

• Forgiveness/Acceptance/

Gratitude

• Integrity

• Honesty

• Courage

• Humility

• Kindness

• Empathy/Compassion

• Patience/Meekness/

Endurance

VISION/MISSION

VALUES OF

ALTRUISTIC LOVE

CALLING

MEMBERSHIP

HOPE/FAITH

• Excellence

0

hope/faith

HF2

0,

e3

HF1

0,

e2

HF3

0,

e20

1

HF5

0,

e5

1

HF4

0,

e4

1

1

0

vision

VIS2

0,

e7

1

VIS1

0,

e6

1

VIS3

0,

e8

1

VIS5

0,

e10

1

VIS4

0,

e9

1

1

0

altruistic

love

0,

e12

0,

e1

1

0,

e11

1

A

L6

0,

e18

1

A

L7

0,

e19

1

A

L

5

0,

e17

1

A

L4

0,

e16

1

A

L3

0,

e15

1

A

L2

0,

e14

1

A

L1

0,

e13

1

0

meaning/

calling

0

membership

MEM5

0,

e26

MEM4

0,

e25

MEM3

0,

e24

MEM2

0,

e23

MEM1

0,

e22

1

1

1

1

1

1

0,

e21

1

0,

e38

MC1

0,

e28

1

1

MC2

0,

e29

1

MC3

0,

e30

1

MC4

0,

e31

1

0

org

commitment

0,

e32

OC1

0,

e34

OC2

0,

e35

OC3

0,

e36

1

OC4

0,

e37

1

1

1

0

productivity

0,

e27

1

PRO3

0,

e41

1

PRO2

0,

e40

1

PRO1

0,

e39

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

0.72

1

1

FIGURE 3

Proposed

School Causal

Model

32

0.48

Hope/Faith

0.6

Altruistic Love

0.41

Meaning/

Calling

0.87

Membership

0.29

Productivity

0.79

Vision

0.80

Organizational

Commitment

0.64

0.68

0.47

0.24

0.30

0.75

0.33

FIGURE 4

Test of School Causal Model

Standardizes Estimates

Chi-Square = 1112.732 (486 df)

p=.000

NFI=.961

IFI=978

CFI=.978

0.56

0.16

0.93

Table 2

VALUES of HOPE/FAITH, and ALTRUISTIC LOVE

1. TRUST/LOYALITY - In my chosen relationships, I am faithful and have faith in

and rely on the character, ability, strength and truth of others.

2. FORGIVENESS/ACCEPTANCE/GRATITUDE – I suffer not the burden of failed

expectations, gossip, jealousy, hatred, or revenge. Instead, I choose the power of

forgiveness through acceptance and gratitude. This frees me from the evils of self-

will, judging others, resentment, self-pity, and anger and gives me serenity, joy and

peace.

3. INTEGRITY – I walk the walk as well as talk the talk. I say what I do and do what I

say.

4. HONESTY – I seek truth and rejoice in it and base my actions on it.

5. COURAGE –I have the firmness of mind and will, as well as the mental and moral

strength, to maintain my morale and prevail in the face of extreme difficulty,

opposition, threat, danger, hardship, and fear.

6. HUMILTY –I am modest, courteous, and without false pride. I am not jealous, rude

or arrogant. I do not brag.

7. KINDNESS – I am warm-hearted, considerate, humane and sympathetic to the

feelings and needs of others.

8. EMPATHY/COMPASSION - I read and understand the feelings of others. When

others are suffering, I understand and want to do something about it.

9. PATIENCE/MEEKNESS/ ENDURANCE - I bear trials and/or pain calmly and

without complaint. I persist in or remain constant to any purpose, idea, or task in the

face of obstacles or discouragement. I pursue steadily any project or course I begin. I

never quit in spite of counter influences, opposition, discouragement, suffering or

misfortune.

10. EXCELLENCE - I do my best and recognize, rejoice in, and celebrate the noble

efforts of my fellows.

11. FUN - Enjoyment, playfulness, and activity must exist in order to stimulate minds

and bring happiness to one’s place of work. I therefore view my daily activities and

work as not to be dreaded yet, instead, as reasons for smiling and having a terrific day

in serving others.

FIGURE 5

FIELD EXPERIMENT INTERVENTION

VISION/STAKEHOLDER EFFECTIVENESS ANALYSIS

5/16/2004

Vision/Stakeholder

Effectiveness Analysis

School 1

12/25/02

Vision

To educate all children, without

exception, to become

successful citizens ready for the

world.

Motto:

We Light the Lamp Within

12/25/02

Purpose

to provide healthy experiences

that foster emotional, social,

physical, and academic growth

of the whole child.

12/26/2002

Mission

School One’s empowered team of skilled

teachers and staff, with the meaningful

involvement of parents and community

partners, educates students in a safe,

clean, caring, and fun environment that

celebrates the noble effort.

12/26/2002

Values

These values reflect how we seek to relate to

students, parents, teachers, school staff, District,

School Board, and community partners

Compassion – Serving and accepting

others to become successful citizens ready

for the world.

Integrity – Conducting ourselves in an

ethical and respectful manner.

5/16/2004

Values Continued

Excellence – Meeting the needs and striving

to exceed the expectations of those we serve

through continuous innovation and

improvement.

Courage – The willingness to test/explore

unproven or established solutions and face

challenges

Fun – Instilling the joy of learning and

celebrating creativity and accomplishments.

35

12/26/2002

Values Continued

Excellence – Meeting the needs and striving

to exceed the expectations of those we serve

through continuous innovation and

improvement.

Courage – The willingness to test/explore

unproven or established solutions and face

challenges

Fun – Instilling the joy of learning and

celebrating creativity and accomplishments.

5/16/2004

Stakeholders/Power/Importance

4. Low Power/High

Importance

Students,

Community

Partners

3. Low Power/Low

Importance

2. High Power/High

Importance

Parents

Teachers

Staff

1. High Power/Low

Importance

KISD

12/25/02

Elementary School

Stakeholder Map

Elementary

Students

Teachers

School Staff

Community

Partners

KISD

Parents

12/25/02

Stakeholder Effectiveness

Criteria

Students- Learning as fun. Caring teachers and

staff, good school supplies and equipment, fun after

school programs, and a clean and safe environment.

Parents- Quality education, qualified and caring

teachers, well-equipped learning environment, clean

and safe environment. Feel welcome. Individual

attention .

Issues: Need more information from them (e.g.

Attitude survey, Computer literate versus non)

12/25/02

Teachers- Parental training and support,

better disciplined parents and students,

uninterrupted teaching time, time for

interaction and collaboration, resources

for changing curriculum , administrative

support in setting priorities, adequate

equipment and supplies, and a safe

environment.

5/16/2004

Issues:

1.What we’re doing is not enough.

2. Lack of Celebration and cross-grade collaboration.

3. Focus on negative, not positive.

4. Kindergarten – involve in scheduling aides.

5. Specialists – feel isolated ( no e-mail).

6. Ist Grade – no time for interaction or team collaboration.

7. Better parent feedback on TEKS Report Categories not

measurable.

8. Input on evaluation of Administration/Staff (360

Feedback).

9. Need CIS and other help with parent orientation,

parenting skills, health and nutrition, counseling, and

after school tutoring.

36

FIGURE 6

FIELD EXPERIMENT RESULTS

Demographics

Demographics

Sample size:

Sample size:

•

•

N

N

-

-

89

89

•

•

School 1

School 1

–

–

57/60

57/60

•

•

School 2

School 2

–

–

31/29

31/29

•

•

Administration

Administration

–

–

9/1

9/1

•

•

Teachers

Teachers

–

–

28/22

28/22

•

•

Paraprofessionals

Paraprofessionals

–

–

7/4

7/4

•

•

Custodians

Custodians

–

–

5/0

5/0

•

•

Cafeteria

Cafeteria

–

–

8/1

8/1

Demographics

Demographics

Continued

Continued

Average Experience:

Average Experience:

•

•

School 1

School 1

–

–

9.16

9.16

•

•

School 2

School 2

–

–

8.67

8.67

Ethnicity:

Ethnicity:

•

•

Caucasian

Caucasian

–

–

40/16

40/16

•

•

African

African

-

-

American

American

–

–

14/8

14/8

•

•

Hispanic

Hispanic

–

–

5/1

5/1

•

•

Other

Other

–

–

1/1

1/1

Age:

Age:

•

•

21

21

-

-

30 years

30 years

–

–

19/9

19/9

•

•

31

31

-

-

40 years

40 years

–

–

18/9

18/9

•

•

41

41

-

-

50 years

50 years

–

–

15/4

15/4

•

•

51

51

-

-

65 years

65 years

–

–

11/5

11/5

Demographics

Demographics

Continued

Continued

Income:

Income:

•

•

Under $20,000

Under $20,000

–

–

18/0

18/0

•

•

$21,000

$21,000

-

-

$30,000

$30,000

–

–

2/3

2/3

•

•

$31,000

$31,000

-

-

$40,000

$40,000

-

-

6/17

6/17

•

•

$41,000

$41,000

-

-

$50,000

$50,000

–

–

9/5

9/5

•

•

Over $50,000

Over $50,000

–

–

3/2

3/2

Education:

Education:

•

•

Less than HS

Less than HS

–

–

3/0

3/0

•

•

HS or GED

HS or GED

–

–

8/1

8/1

•

•

Some College

Some College

–

–

10/2

10/2

•

•

College Grad

College Grad

–

–

36/23

36/23

37

Vision School 1

Vision School 1

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

Initial Final

Disagree Neither Agree

Disagree Neither Agree

%

%

Averages 1/2

Averages 1/2

4.2/4.3

4.2/4.3

Vision School 2

Vision School 2

0

10

20

30

40

50

Initial Final

Disagree Neither Agree

Disagree Neither Agree

%

%

Averages 1/2

Averages 1/2

3.6/2.8*

3.6/2.8*

Altruistic Love

Altruistic Love

School 1

School 1

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

Initial Final

%

%

Disagree Neither Agree

Disagree Neither Agree

Averages 1/2

Averages 1/2

3.9/4.4*

3.9/4.4*

Altruistic Love

Altruistic Love

School 2

School 2

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

Initial Final

%

%

Disagree Neither Agree

Disagree Neither Agree

Averages 1/2

Averages 1/2

3.3/3.1

3.3/3.1

Hope/Faith

Hope/Faith

School 1

School 1

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

Initial Final

%

%

Disagree Neither Agree

Disagree Neither Agree

Averages1/2

Averages1/2

4.6/4.2

4.6/4.2

Hope/Faith

Hope/Faith

School 2

School 2

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

Initial Final

%

%

Disagree Neither Agree

Disagree Neither Agree

Averages1/2

Averages1/2

4.0/2.8*

4.0/2.8*

38

Meaning/Calling

Meaning/Calling

School 1

School 1

0

20

40

60

80

100

Initial Final

%

%

Disagree Neither Agree

Disagree Neither Agree

Averages1/2

Averages1/2

4.7/4.5

4.7/4.5

Meaning/Calling

Meaning/Calling

School 2

School 2

0

20

40

60

80

100

Initial Final

%

%

Disagree Neither Agree

Disagree Neither Agree

Averages1/2

Averages1/2

4.5/3.8*

4.5/3.8*

Membership

Membership

School 1

School 1

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

Initial Final

%

%

Disagree Neither Agree

Disagree Neither Agree

Averages1/2

Averages1/2

3.9/4.2

3.9/4.2

Membership

Membership

School 2

School 2

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

Initial Final

0.0

0.0

%

%

Disagree Neither Agree

Disagree Neither Agree

Averages1/2

Averages1/2

3.5/2.3*

3.5/2.3*

39

Organizational Commitment

Organizational Commitment

School 1

School 1

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

Initial Final

%

%

Disagree Neither Agree

Disagree Neither Agree

Averages1/2

Averages1/2

3.5/4.3*

3.5/4.3*

Organizational Commitment

Organizational Commitment

School 2

School 2

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

MARLBORO1 MARLBORO2

%

%

Disagree Neither Agree

Disagree Neither Agree

Averages1/2

Averages1/2

3.4/2.7*

3.4/2.7*

Organizational Productivity

Organizational Productivity

School 1

School 1

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

Initial Final

%

%

Disagree Neither Agree

Disagree Neither Agree

Averages1/2

Averages1/2

4.2/4.2

4.2/4.2

Organizational Productivity

Organizational Productivity