SOUTHWEST

BORDER SECURITY

Additional Actions

Needed to Better

Assess Fencing's

Contributions to

Operations and

Provide Guidance for

Identifying Capability

Gaps

Report to Congressional Requesters

February 2017

GAO-17-331

United States Government Accountability Office

United States Government Accountability Office

Highlights of GAO-17-331, a report to

congressional requesters

February 2017

SOUTHWEST BORDER SECURITY

Additional Actions Needed to Better

Assess

Fencing's Contributions to Operations and Provide

Guidance for Identifying Capability Gaps

What GAO Found

Border fencing is intended to benefit border security operations in various ways,

according to officials from the U.S. Border Patrol (Border Patrol), which is within

the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) U.S. Customs and Border

Protection (CBP). For example, according to officials, border fencing supports

Border Patrol agents’ ability to execute essential tasks, such as identifying illicit-

cross border activities. CBP collects data that could help provide insight into how

border fencing contributes to border security operations, including the location of

illegal entries. However, CBP has not developed metrics that systematically use

these, among other data it collects, to assess the contributions of border fencing

to its mission. For example, CBP could potentially use these data to determine

the extent to which border fencing diverts illegal entrants into more rural and

remote environments, and border fencing’s impact, if any, on apprehension rates

over time. Developing metrics to assess the contributions of fencing to border

security operations could better position CBP to make resource allocation

decisions with the best information available to inform competing mission

priorities and investments.

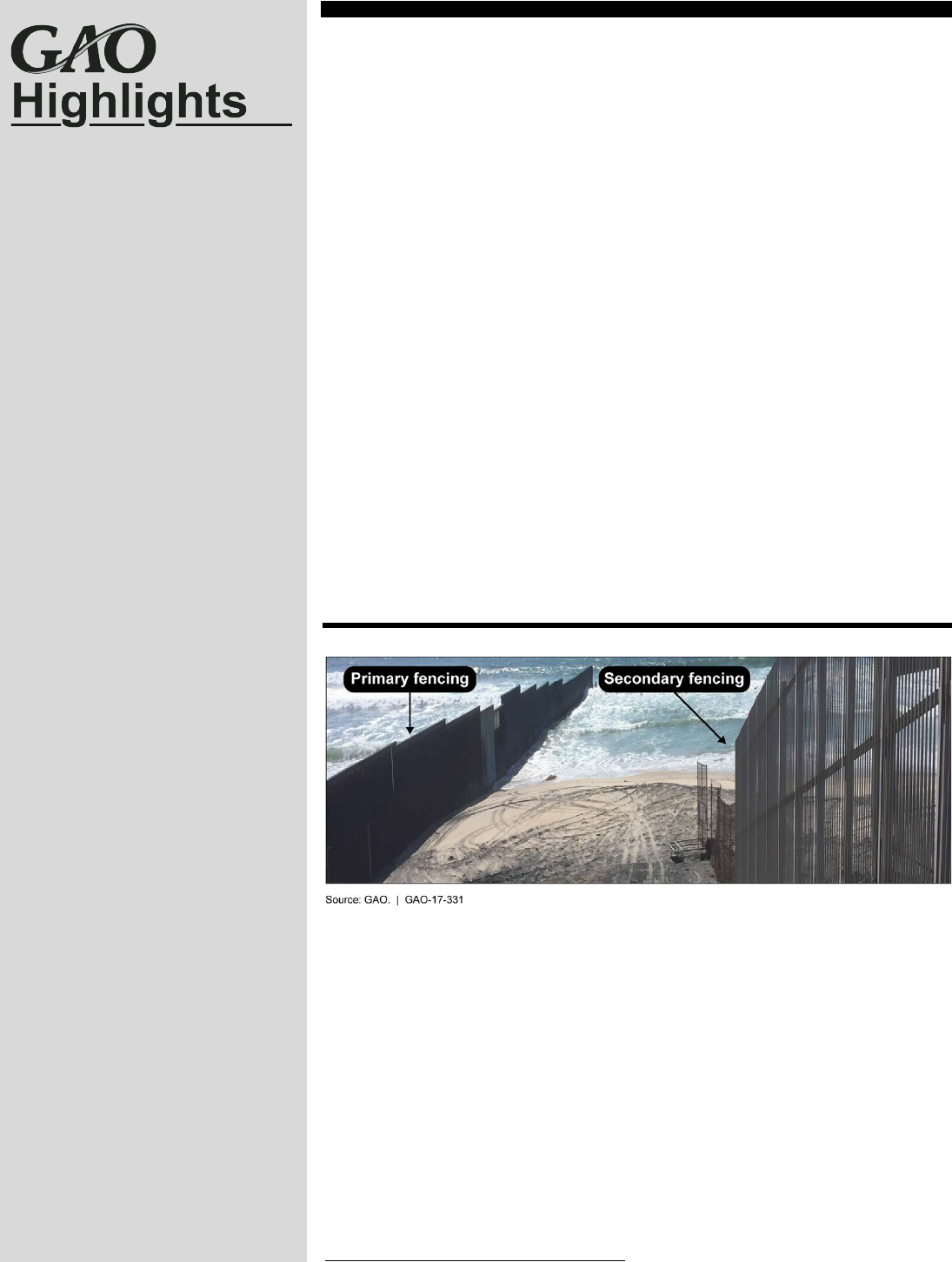

Pedestrian Fencing in San Diego, California, April 2016

CBP is taking a number of steps to sustain tactical infrastructure (TI) along the

southwest border; however, it continues to face certain challenges in maintaining

this infrastructure, such as addressing maintenance of roads owned or operated

by other public and private entities. In 2014, according to Border Patrol officials,

Border Patrol began implementing the Requirements Management Process that

is designed to facilitate planning for funding and deploying TI and other

requirements. Border Patrol headquarters and sector officials told GAO that

Border Patrol lacks adequate guidance for identifying, funding, and deploying TI

needs as part of this process. In addition, officials reported experiencing some

confusion about their roles and responsibilities in this process. Developing

guidance on this process would be consistent with federal internal control

standards and would provide more reasonable assurance that the process is

consistently followed across Border Patrol. This is a public version of a For

Official Use Only—Law Enforcement Sensitive report that GAO issued in

December 2016. Information DHS deemed For Official Use Only—Law

Enforcement Sensitive has been redacted.

View GA O-17-331. For more information,

contact Rebecca Gambler at (202) 512-8777

Why GAO Did This Study

In fiscal years 2013 through 2015,

Border Patrol recorded a total of 2.1

million estimated known illegal entries

between ports of entry along the

southwest border. In an effort to secure

the border between ports of entry, CBP

spent approximately $2.4 billion

between fiscal years 2007 and 2015 to

deploy TI — fencing, gates, roads,

bridges, lighting, and drainage

infrastructure—along the nearly 2,000

mile southwest border.

GAO was asked to review the use of

border fencing along the southwest

border. In this report, GAO examines

(1) border fencing’s intended

contributions to border security

operations and the extent to which

CBP has assessed these contributions

and (2) the extent that CBP has

processes in place to ensure

sustainment and deployment of TI

along the southwest border and

challenges in doing so. GAO reviewed

CBP documentation and data and

interviewed officials in headquarters

and three southwest border locations.

These locations were selected based

on CBP’s extensive investments in TI

in such areas.

What GAO Recommends

GAO recommends that Border Patrol

develop metrics to assess the

contributions of pedestrian and vehicle

fencing to border security along the

southwest border and develop

guidance for its process for identifying,

funding, and deploying TI assets for

border security operations. DHS

concurred with the recommendations.

Page i GAO-17-331 Tactical Infrastructure

Letter 1

Background 7

Fencing Is Intended to Assist Agents in Performing Their Duties,

but Its Contributions to Border Security Operations Have Not

Been Assessed 20

CBP Manages TI Sustainment but Border Patrol Has Not Provided

Guidance on its Process for Identifying and Deploying TI 27

Conclusion 36

Recommendations for Executive Action 37

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation 37

Appendix I Descriptive Analysis of Selected Tactical Infrastructure (TI) and

Estimated Known Illegal Entries in Southwest Border Zones from

Fiscal Years 2013 Through 2015 40

Appendix II Objectives, Scope and Methodology 57

Appendix III Comments from the Department of Homeland Security 65

Appendix IV GAO Contact and Staff Acknowledgments 69

Tables

Table 1: Border Patrol Mission Essential Tasks 15

Table 2: Border Patrol Foundational Operational Capabilities

(FOC) 15

Table 3: Average Cost per Mile of Completed Southwest Border

Fence Replacement Projects, Fiscal Years 2011-2016 34

Figures

Figure 1: Total Miles of Primary Fencing on the Southwest Border,

Fiscal Years 2005 to 2015 9

Figure 2: Selected Designs of Pedestrian Fencing on the

Southwest Border 11

Contents

Page ii GAO-17-331 Tactical Infrastructure

Figure 3: Selected Designs of Vehicle Fencing and Other Tactical

Infrastructure on the Southwest Border 12

Figure 4: Border Patrol Sectors along the Southwest Border and

Border Stations and Zones in the Tucson Sector 14

Figure 5: U.S. Border Patrol’s Requirements Management

Process 17

Figure 6: U.S. Border Patrol’s Capability Gap Analysis Process 19

Figure 7: Select Methods used by Illegal Entrants to Defeat Border

Fencing on the Southwest Border 24

Figure 8: Fence Breach Due To Drive-Through Entry and

Subsequent Repair 30

Figure 9: Legacy Pedestrian Fencing in Sunland Park, New

Mexico, March 2016 31

Figure 10: Legacy Pedestrian Fencing in Sunland Park, New

Mexico, March 2016 32

Page iii GAO-17-331 Tactical Infrastructure

Abbreviations

BPETS Border Patrol Enforcement Tracking System

CBP U.S. Customs and Border Protection

CGAP Capability Gap Analysis Process

CTIMR Comprehensive Tactical Infrastructure Maintenance and

Repair

DHS Department of Homeland Security

EID Enforcement Integrated Database

FM&E Facilities Management and Engineering

FOCs Foundational Operational Capabilities

GPRA Government Performance and Results Act of 1993

IIRIRA Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility

Act of 1996

METs Mission Essential Tasks

ORMD Operational Requirements Management Division

SPA Strategic Planning and Analysis Directorate

TI Tactical Infrastructure

W MS Work Management System

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the

United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety

without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain

copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be

necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.House of Representatives

Page 1 GAO-17-331 Tactical Infrastructure

441 G St. N.W.

Washington, DC 20548

February 16, 2017

Congressional Requesters

In fiscal years 2013 through 2015, U.S. Border Patrol (Border Patrol),

within the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) U.S. Customs and

Border Protection (CBP), recorded a total of 2.1 million estimated known

illegal entries

1

between ports of entry along the southwest border.

2

As the

agency responsible for securing U.S. borders to prevent acts of terrorism

and the unlawful movement of people, illegal drugs, and other contraband

across U.S. borders, CBP spent approximately $2.4 billion between fiscal

years 2007 and 2015 to deploy tactical infrastructure (TI)—fencing, gates,

roads, bridges, lighting, and drainage infrastructure—along the nearly

2,000 mile southwest border.

3

CBP now has the responsibility of

sustaining border TI over its lifetime—including 654 miles of primary

pedestrian and vehicular fencing and approximately 5,000 miles of

roads.

4

In 2009, CBP estimated that it would need to spend more than

$3.5 billion over the next 20 years on TI operations and maintenance to

1

Border Patrol defines estimated illegal entries as the total number of removable aliens

who were apprehended, in addition to the number of entrants who illegally crossed the

border but were not apprehended. We defined these illegal entries as estimated “known”

illegal entries to clarify that the estimates do not include illegal entrants for which Border

Patrol does not have reasonable indications of cross-border illegal activity.

2

Ports of entry are facilities that provide for the controlled entry into or departure from the

United States. Specifically, a port of entry is any officially designated location (seaport,

airport, or land border location) where DHS officers or employees are assigned to clear

passengers and merchandise, collect duties, and enforce customs laws, and where DHS

officers inspect persons entering or applying for admission into, or departing the United

States pursuant to U.S. immigration law.

3

See 6 U.S.C. § 211(a) (establishing CBP within DHS), (c) (enumerating CBP’s duties).

4

Pedestrian fencing is primarily intended to slow down and deter pedestrians from

crossing the border. Vehicle fencing, which is intended to resist vehicles engaged in drug

trafficking and alien smuggling operations, is typically used in rural or isolated locations

that have a low occurrence of illegal pedestrian traffic. In March 2016 we reported that 652

miles of fencing were deployed on the southwest border. See GAO, Southwest Border

Security: Additional Actions Needed to Assess Resource Deployment and Progress,

GAO-16-465T (Washington, D.C.: Mar. 1, 2016). CBP has conducted an in depth review

of geospatial data on fencing and adjusted its estimate of deployed primary border fencing

to 654 miles.

Letter

Page 2 GAO-17-331 Tactical Infrastructure

sustain these investments and to ensure TI continues to support Border

Patrol’s mission.

5

Our prior work on TI highlighted DHS’s increased investment in TI and the

challenges associated with increased construction and deployment of

fencing on the southwest border. In September 2009, we found that CBP

had not assessed TI’s impact on border security operations or mission

goals and had not measured the effectiveness of TI.

6

Specifically, we

found that CBP had not accounted for the impact of its investment in

border fencing and infrastructure on border security. We recommended

that CBP conduct an evaluation of the impact of TI on effective control of

the border.

7

You requested that we review the use of border fencing along the

southwest border. In this report, we examine (1) border fencing’s intended

contributions to border security operations and the extent to which CBP

has assessed these contributions and (2) the extent that CBP has

processes in place to ensure sustainment

8

and deployment of TI along

the southwest border and challenges in doing so. In addition, in Appendix

5

Cost information is based on CBP’s 2009 Life Cycle Cost Estimate (LCCE) for all TI,

which includes border fencing, roads, lighting, drainage, and vegetation control from 2009

to 2026. CBP officials stated that CPB is currently updating the LCCE and expects to

complete it by the end of fiscal year 2017.

6

GAO, Secure Border Initiative: Technology Deployment Delays Persist and the Impact of

Border Fencing Has Not Been Assessed, GAO-09-896 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 9, 2009).

In response to our recommendation that CBP conduct an evaluation of the im pact of TI,

CBP developed interim metrics, and we closed the recommendation as implemented.

However, in November 2015, CBP reported that it had not completed or implemented

these interim metrics due to funding challenges. We discuss CBP’s efforts to develop

performance measures later in this report.

7

Prior to 2011, DHS used the number of border miles under “operational control”—also

referred to as effective control—as its goal and outcome measure for border security and

to assess resource needs to accomplish this goal. In 2012, Border Patrol transitioned to

achieving a “low risk border” as its goal and uses a variety of data to assess risk,

including: threats of cross-border terrorism, drug smuggling, illegal migration across

locations; integrating border security operations with those of other law enforcement

partners’ and developing rapid response capabilities to deploy the resources appropriate

to changes in threat.

8

For the purposes of this report, sustainment refers to the maintenance, repair, and new

construction of TI.

Page 3 GAO-17-331 Tactical Infrastructure

I we provide analyses of border fencing and total estimated known illegal

entries in each southwest border sector.

9

This report is a public version of the prior sensitive report that we

provided to you in December 2016.

10

DHS deemed some of the

information in the prior report as For Official Use Only—Law Enforcement

Sensitive, which must be protected from public disclosure. Therefore, this

report omits sensitive information on sustainment of TI and our analysis of

Border Patrol data on fencing and enforcement activities. Although the

information in this report is more limited in scope, it addresses the same

questions as the sensitive report. Also, the overall methodology used for

both reports is the same.

11

To examine border fencing’s intended contributions to border security

operations and the extent to which CBP has assessed these

contributions, we analyzed relevant documentation, including Border

Patrol’s State of the Border Risk Methodology, which Border Patrol uses

to assess risk across the southwest border, and documents identifying

CBP mission goals and objectives and related performance measures.

We also reviewed relevant acquisition documents that CBP developed

during the construction of TI across the southwest border. We interviewed

officials from Border Patrol’s Strategic Planning and Analysis (SPA)

Directorate, which is responsible for identifying risk along the southwest

border and the Operational Requirements Management Division (ORMD)

which is responsible for deploying operational requirements, including TI,

to mitigate these risks. During these interviews we focused on the

intended and actual contributions of border fencing in providing Border

Patrol agents with Foundational Operational Capabilities (FOC) and

assisting Border Patrol agents in executing their Mission Essential Tasks

9

Border Patrol divides responsibility for border security operations geographically among

nine sectors, each with its own headquarters. Each sector is further divided into varying

numbers of stations.

10

GAO, Southwest Border Security: Additional Actions Needed to Assess Fencing’s

Contributions to Operations and Provide Guidance for Identifying Capability Gaps,

GAO-17-167SU (Washington D.C.: Dec. 22, 2016).

11

This work was conducted prior to the issuance of the Executive Order related to border

security and immigration enforcement, which the President signed on January 25, 2017.

See Border Security and Immigration Enforcement Improvements, Exec. Order No.

13767, 82 Fed.Reg. 8793 (Jan. 30, 2017).

Page 4 GAO-17-331 Tactical Infrastructure

(MET).

12

For this objective, we also analyzed fence breaches by fence

design. To do this analysis, we obtained pedestrian fence breach data

from Border Patrol Facilities and Tactical Infrastructure (BPFTI) for fiscal

years 2010 through 2015. To assess the reliability of these data, we

reviewed how CBP collects and maintains breach data and found that the

data were sufficiently reliable for the purposes of our report. We then

analyzed the occurrences of breaches in modern compared to legacy

pedestrian fence designs.

13

We also discussed the limitations associated

with border fencing, including the methods employed by illegal entrants in

defeating border fencing, including breaches.

During our meetings with ORMD and SPA, we also focused on CBP’s

efforts to assess border fencing’s contributions to border security

operations, and the perceived challenges involved in conducting such an

assessment. We compared these efforts against criteria established in

our prior work on leading practices for performance management.

14

To

identify border fencing’s intended contributions to border security

operations at the sector level, we visited the El Paso, San Diego, and

Tucson Sectors. We selected these sectors for site visits due to CBP’s

extensive investments in TI in each sector over the years. Combined,

these sectors contain approximately 52 percent of all miles of primary

pedestrian fencing and 80 percent of all miles of vehicle fencing along the

southwest border. During these site visits, we interviewed Border Patrol

sector officials, agents selected by sector officials, and agents assigned

12

Border Patrol defines FOCs as the essential combinations of resources (personnel,

training, equipment, technology, and infrastructure) that provide Border Patrol agents with

the fundamental operational means by which to conduct their Mission Essential Tasks

(METs). Border Patrol defines the METs as a sequential set of discreet or unique tasks in

which Border Patrol agents must be proficient to execute their duties in the furtherance of

border security operations.

13

For the purposes of this report, we refer to any fencing designs used prior to CBP

implementing requirements of the Secure Fence Act of 2006 (Pub. L. No. 109-367, 120

Stat.2638) as “legacy” fencing and any fencing deployed subsequently as “modern”

fencing designs. In addition, all “landing mat” fencing—constructed of army surplus carbon

steel landing mats which were used to create landing s trips during the Vietnam War—is

considered “legacy” fencing design, regardless of when it was constructed.

14

GAO, Managing for Results: Enhancing Agency Use of Performance Information for

Management Decision Making, GAO-05-927 (Washington, D.C.: September 2009).

Page 5 GAO-17-331 Tactical Infrastructure

to various stations and zones within each sector.

15

Our interviews in each

sector focused on agents’ perspectives on border fencing’s specific

contributions to border security within each sector as well as the extent to

which border fencing has provided Border Patrol agents with the

capabilities border fencing was intended to provide, and the extent to

which border fencing assists Border Patrol agents in executing their

METs. We also collected information on other perceived benefits of

border fencing, including agent safety, as well as perceived limitations of

border fencing. While the information we obtained from our site visits

cannot be generalized to all Border Patrol sectors, it provided us with

insights about border fencing’s contribution to border security operations.

To determine the extent that CBP has processes in place to ensure

sustainment and deployment of TI along the southwest border and

challenges in doing so, we reviewed relevant documentation and

interviewed headquarters officials from CBP. Documents we reviewed

included contracts, which CBP uses to maintain and repair all TI assets

across the southwest border. To assess how CBP manages the

deployment of TI across the southwest border, we reviewed relevant

documentation from ORMD, which is responsible for executing Border

Patrol’s requirements management process and deploying TI, among

other assets, along the southwest border. These documents included

Border Patrol’s Capability Gap Analysis Process (CGAP) and the various

outputs of this process. We compared these documents against criteria

outlined in Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government.

16

We also interviewed officials from BPFTI, which is responsible for

sustaining TI along the southwest border, and ORMD. Our interviews with

BPFTI officials focused on the program’s contracts and work plans,

oversight of contractors, the system that BPFTI uses to track and oversee

all TI related maintenance and repair work, and any challenges BPFTI or

contractors may face in sustaining TI along the southwest border. Our

interview with ORMD focused on Border Patrol’s process for identifying TI

requirements in each sector, prioritizing TI requirements across all nine

southwest border sectors, and allocating resources and deploying TI

15

Border Patrol has divided the southwest border into nine sectors. Each southwest

border sector is divided into varying numbers of stations, with agents assigned to patrol

defined geographic areas, or zones, within each station. Of these, zones that touch the

international border are known as border zones, while zones that do not touch the

international border are known as interior zones.

16

GAO, Standards for Internal Control in the Federal Government, GAO-14-704G

(Washington, D.C.: Sept. 2014).

Page 6 GAO-17-331 Tactical Infrastructure

solutions. During our site visits, we interviewed relevant BPFTI and

Border Patrol officials responsible for overseeing the sustainment of TI in

the sector. In these meetings, we discussed past and ongoing TI

projects–-including fence replacement projects and other major repairs-–

as well as any challenges the sectors face in sustaining the TI deployed

there. We also toured each sector’s TI inventory, which include

pedestrian and vehicle fencing, gates, roads, bridges, grates, and lighting.

In the El Paso and Tucson sectors, we visited segments of legacy

pedestrian fencing slated for replacement with more modern pedestrian

fencing.

To analyze the location of estimated illegal entries in conjunction with

border fencing, we obtained Border Patrol data on estimated known

illegal entries in border zones within each of the nine sectors along the

southwest border for fiscal years 2013 through 2015.

17

We also obtained

data on the location of CBP’s 654 miles of primary border fencing, by

fencing type, and design in each sector, and combined these two data

sets. Through this analysis, we were able to identify the (1) total

estimated known illegal entries, (2) estimated turn backs and got aways,

(3) estimated drive throughs and (4) apprehension rates for estimated

illegal entries in southwest border zones with border fencing, by fence

type, design, and zone coverage,

18

and in southwest border zones

without border fencing. We then used these data to create data tables for

each sector that visually display the results of our analysis. We assessed

the reliability of these data by interviewing knowledgeable CBP officials

on the limitations of these data and digital testing of these data. To

17

We obtained apprehension data for fiscal years 2013 through 2015 from the

Enforcement Integrated Database —a DHS-shared common database repository for

several DHS law enforcement and homeland security applications. We obtained data on

entrants who illegally crossed the border but were not apprehended either because they

crossed back to Mexico—”turn backs”—or continued traveling to the U.S. interior and

Border Patrol was no longer actively pursuing them—”got aways”—from the Border Patrol

Enforcement Tracking System. We obtained data on border crossings by motor vehicles—

”drive throughs” —from the same database. (The individuals involved in a “drive through”

are counted among apprehensions, turn backs, or got aways if agents are able to

ascertain the number of individuals in the vehicle.) Apprehension, turn back, and got away

data for fiscal years 2013 through 2015 were queried (i.e., obtained from relevant

databases) as of February 2016. We selected these data for fiscal years 2013 through

2015 because beginning fiscal year 2013, Border Patrol standardized how it collects and

records got aways and turn backs, which improved the reliability of these data.

18

For the purposes of this document, the term “zone coverage” refers to the extent to

which the border miles of a border zone are fenced. In our analysis, we classified border

zone coverage as follows: complete (100 percent) border fence coverage, partial border

fence coverage, or no border fence coverage.

Page 7 GAO-17-331 Tactical Infrastructure

assess the reliability of the sector fence data we collected, we reviewed

the data for any inconsistencies in fence mileage in each sector, by type

and design. As a result of our data reliability assessment, we determined

that both CBP’s estimated known illegal entry data and sector fence data

were sufficiently reliable for our intended use. For more information on

our scope and methodology for the sector data tables, see Appendix I.

Appendix II provides further details on our scope and methodology.

We conducted this performance audit from October 2015 to February

2017 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing

standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to

obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for

our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe

that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings

and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

The Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA)

of 1996, as amended, states that the Secretary of Homeland Security

shall take actions, as necessary, to install physical barriers and roads in

the vicinity of the border to deter illegal crossings in areas of high illegal

entry.

19

As originally enacted, IIRIRA also required the completion of a

triple-layer fence and road improvements along 14 miles of border near

San Diego, where Border Patrol had begun installing fence in the

1990s.

20

The Secure Fence Act of 2006 amended IIRIRA to require DHS

to construct at least two layers of reinforced fencing as well as physical

barriers, roads, lighting, cameras, and sensors on certain segments of the

southwest border in California, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas.

21

Subsequently, the DHS Appropriations Act, 2008, rewrote the border

19

Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA) of 1996. Pub. L.

No. 104-208, div. C, tit. I, subtit. A, § 102(a), 110 Stat. 3009, 3009-554 (classified, as

amended at 8 U.S.C. § 1103 note).

20

IIRIRA § 102(b), 110 Stat. at 3009-554 to -555.

21

See Pub. L. No. 109-367, § 3, 120 Stat. 2638, 2638-2639. Under the Secure Fence Act

of 2006, the Secretary of Homeland Security is to achieve and maintain operational

control over the borders of the United States through surveillance activities and physical

infrastructure enhancements to prevent unlawful entry by aliens and facilitate CBP’s

access to the borders. See id. § 2, 120 Stat. at 2638 (classified at 8 U.S.C. § 1701 note).

Background

TI along the Southwest

Border

Page 8 GAO-17-331 Tactical Infrastructure

fencing requirements section of IIRIRA to require that DHS construct not

less than 700 miles of reinforced fencing along the southwest border

where fencing would be most practical and effective, and to provide for

the installation of additional physical barriers, roads, lighting, cameras,

and sensors to gain operational control of the southwest border.

22

GAO

has ongoing work on roads used by Border Patrol and plans to complete

this work in 2017.

From fiscal years 2005 through 2015, CBP increased the total miles of

primary border fencing on the southwest border from 119 miles to 654

miles—including 354 miles of primary pedestrian fencing and 300 miles of

primary vehicle fencing. With 654 miles of primary fencing currently

deployed, CBP officials have stated that CBP is in compliance with its

legal requirements for the construction of southwest border fencing based

on the substantial discretion provided to the Secretary of Homeland

Security to determine the appropriate placement of fencing.

23

Figure 1

shows the increase in the total miles of primary fencing on the southwest

border from fiscal years 2005 to 2015.

22

IIRIRA § 102(b), 110 Stat. at 3009-554 to -555, as amended by Pub. L. No. 110-161,

div. E, tit. V, § 564(a)(2)(B)(ii), 121 Stat. 1844, 2090-91 (2007) (classified at 8 U.S.C. §

1103 note). IIRIRA § 102(b), as amended, also gives the Secretary of Homeland Security

discretion to install TI in particular locations along the border, as deemed appropriate. Id.

23

See 8 U.S.C. § 1103 note (notwithstanding fencing requirements, DHS is not required to

install fencing or other resources in a particular location along the border, if the Secretary

of Homeland Security determines that the use or placement of such resources is not the

most appropriate means to achieve and maintain operational control over the border at

that location). See also United States v. Arizona, No. 2:10-cv-10-01413-SRB, Order

Granting Government’s Motion to Dismiss Counterclaims (D. Ariz. Oct. 21, 2011).

Page 9 GAO-17-331 Tactical Infrastructure

Figure 1: Total Miles of Primary Fencing on the Southwest Border, Fiscal Years

2005 to 2015

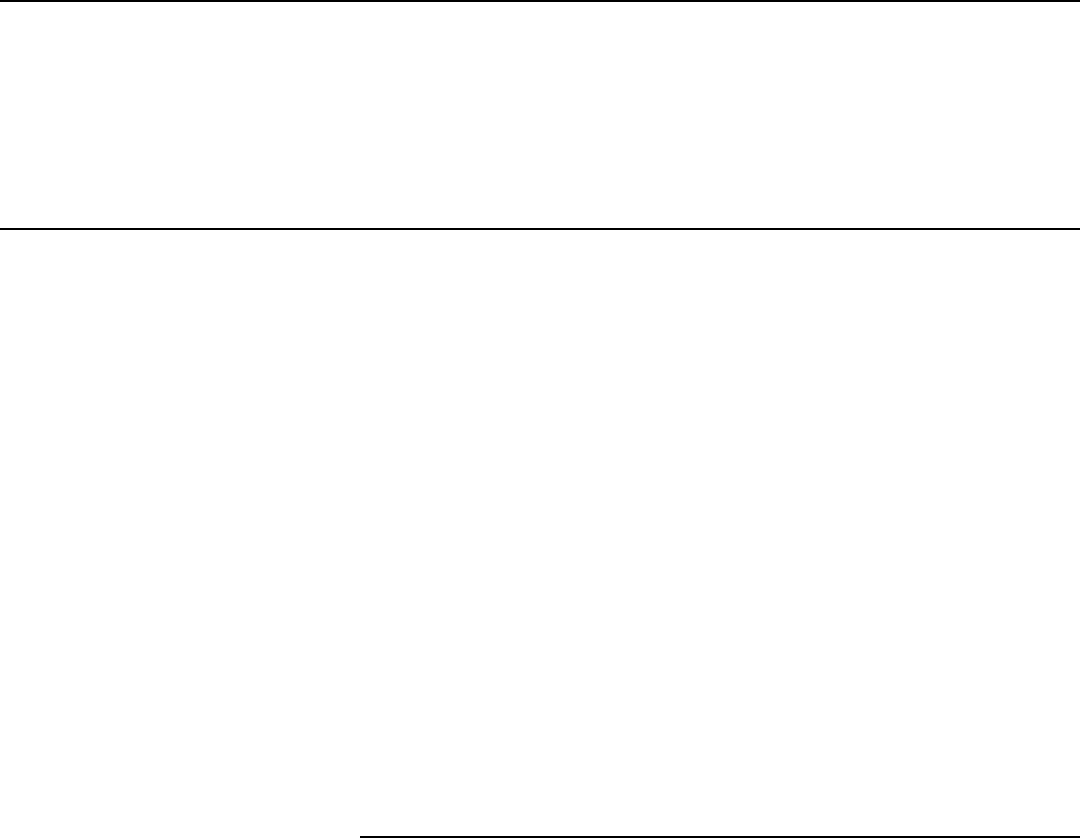

CBP used various fencing designs to construct the 654 miles of primary

pedestrian and vehicle border fencing including, for example, bollard, wire

mesh, and chain link style fencing designs. Border fencing designs have

developed over time from legacy designs used prior to CBP implementing

requirements of the Secure Fence Act of 2006, to subsequent modern

designs. In addition to the 654 miles of primary fencing, CBP has also

deployed additional layers of pedestrian fencing behind the primary

border fencing, including 37 miles of secondary fencing and 14 miles of

tertiary fencing.

24

CBP has also deployed other types of TI along the

southwest border with various purposes. For example, lighting along the

border is designed to further deter illegal activities. Roads and bridges

provide Border Patrol agents access to the border to interdict and

24

The first layer of fencing, the primary fence, may include both pedestrian and vehicle

fencing and is the first fence encountered when moving north from the border; the

secondary fence, located behind the primary fence, consists solely of pedestrian fencing;

and the third layer, or tertiary fence, is primarily used to delineate property lines rather

than deter illegal entries.

Page 10 GAO-17-331 Tactical Infrastructure

apprehend illegal entrants as well as supporting the maintenance and

construction of TI. Drainage systems and grates facilitate the

maintenance of roads and fences and can provide additional border

security. See figures 2 and 3 for examples of selected fencing types and

designs as well as other types of TI deployed at the border.

Page 11 GAO-17-331 Tactical Infrastructure

Figure 2: Selected Designs of Pedestrian Fencing on the Southwest Border

Note: For the purposes of this report, w e refer to any fencing constructed prior to Customs and

Border Protection implementing requirements of the Secure Fence Act of 2006 as “legacy” fencing

designs and any fencing deployed subsequently as having “modern” fencing designs. In addition, all

“landing mat” fencing—constructed of army surplus carbon steel landing mats w hich w ere used to

Page 12 GAO-17-331 Tactical Infrastructure

create landing strips during the Vietnam War—is considered “legacy” fencing, regardless of w hen it

w as constructed.

Figure 3: Selected Designs of Vehicle Fencing and Other Tactical Infrastructure on the Southwest Border

Page 13 GAO-17-331 Tactical Infrastructure

Note: For the purposes of this report, w e refer to any fencing constructed prior to Customs and

Border Protection implementing requirements of the Secure Fence Act of 2006 as “legacy” fencing

designs and any fencing deployed subsequently as having “modern” fencing designs.

Border Patrol, within CBP, is the federal agency with primary

responsibility for securing the national borders by detecting, interdicting,

and disrupting illegal cross-border activities between the designated U.S.

land border ports of entry.

25

To secure the nearly 2,000 mile southwest

border, Border Patrol divides responsibility for border security operations

geographically among nine sectors, as shown in figure 4. Each sector has

its own headquarters and is further divided into varying numbers of

stations, with agents assigned to patrol defined geographic areas, or

zones, within each station. According to Border Patrol officials, zones

allow sectors to more effectively analyze border conditions, including

terrain, when planning how to deploy agents. Zone dimensions are largely

determined by geography and topographical features, and zone size can

vary significantly.

25

See 6 U.S.C. § 211(e) (establishing and listing duties of U.S. Border Patrol within CBP).

Border Patrol Operations

along the Southwest

Border

Page 14 GAO-17-331 Tactical Infrastructure

Figure 4: Border Patrol Sectors along the Southwest Border and Border Stations and Zones in the Tucson Sector

Within each sector, station, and zone, Border Patrol agents’ primary

mission is to prevent terrorists and terrorist weapons from entering the

United States, and to detect, interdict, and apprehend those who attempt

to enter illegally or smuggle any person or contraband across the nation’s

borders. To accomplish this mission, Border Patrol agents must be

proficient in a sequential set of “Mission Essential Tasks” (METs) in order

to execute their duties in the furtherance of border security operations

(see table 1).

Page 15 GAO-17-331 Tactical Infrastructure

Table 1: Border Patrol Mission Essential Tasks

Predict

To anticipate and target illegal traffic actions prior to illegal entry

Detect

To discover the presence of a possible item of interest or suspected contraband

Identify

To determine whether an item of interest is human, animal, conveyance, or unknown

Classify

To determine the level of threat, risk, and/or intent of item of interest

Track

To follow the progress or movements of an item of interest

Respond

To dispatch or employ law enforcement resources to address a potential incursion

Resolve

To take final action, whether legal, administrative, or otherwise; capture data, and process information

Source: U .S. Border Patrol. | GAO-17-331

To assist agents in executing their METs, Border Patrol deploys various

resources, including surveillance technology and TI, to sectors, stations,

and zones. Each of these resources provides agents with the essential

operational capabilities necessary to execute each MET. Border Patrol

defines these capabilities as “Foundational Operational Capabilities”

(FOC) (see table 2).

Table 2: Border Patrol Foundational Operational Capabilities (FOC)

Impedance and Denial

Capability to impede border incursions and deny the threat’s use of terrain to their advantage in

conducting illegal activities or acts of terrorism.

Operational Mobility

Capability to gain and maintain access to Border Patrol areas of responsibility and rapidly move

Border Patrol resources at any time.

Domain Awareness/ Persistent

Surveillance

Ability to continuously detect, identify, classify, and track all border incursions in targeted areas

at all times.

Logistics and Manpower/ Support

and Sustainment

Ability to maintain, mature, refine, and integrate various capabilities to meet Border Patrol

mission and statutory requirements.

Command, Control,

Communications, and Coordination

Capability to effectively use and coordinate Border Patrol resources during operations.

Intelligence and Counter-

intelligence

Capability to produce and disseminate timely, well-formulated, and actionable intelligence

concerning border security threats and prevent threat organizations from gathering intelligence

against Border Patrol.

Security Partnerships

Capability to harness the political, social, economic, information, infrastructure, and technology

assets of the border area to enhance national security.

Source: U .S. Border Patrol. | GAO-17-331

Note: FOCs are current as of May 2016. At the time of our review , Border Patrol of ficials told us they

w ere in the process of updating the FOCs.

According to Border Patrol officials, TI facilitates the capabilities for

“impedance and denial” and “operational mobility.” Border fencing,

including pedestrian and vehicle fencing, is intended to facilitate the

“impedance and denial” FOC by diverting and delaying illegal entries.

Page 16 GAO-17-331 Tactical Infrastructure

Patrol roads and bridges are intended to facilitate the “operational

mobility” FOC by enabling agents to efficiently traverse their areas of

responsibility. Other resources that Border Patrol deploys, including

surveillance technology, facilitate domain awareness, and do so by

providing persistent surveillance capabilities along the border. According

to Border Patrol officials, agents require the appropriate combination of

resources in each sector, station, and zone to facilitate each FOC and

ensure agents can successfully execute their METs. Due to variations in

terrain and local population density, among other factors, the appropriate

combination of these resources may vary across sectors, stations, and

zones.

To assess cross-border threats, Border Patrol collects and analyzes data

on the number and types of entrants who illegally cross the southwest

border between the land border ports of entry. These data include

estimates of the total number of directly or indirectly observed—or

“known”—illegal entries by sector, station, and zone. Estimated known

illegal entries consist of the total number of illegal entrants who were

apprehended, in addition to the number of entrants who illegally crossed

the border but were not apprehended—”turn backs” and “got aways.”

26

Border Patrol also collects data on the number of vehicles that illegally

cross the border, known as “drive throughs”.

From fiscal year 2007 to 2015, CBP spent approximately $2.4 billion on TI

on the southwestern border—about 95 percent, or $2.3 billion was spent

on constructing pedestrian and vehicle fencing.

27

In addition, CBP officials

reported that TI operations and maintenance requirements totaled

approximately $450 million during this same period. We reported in 2009

that the average cost per mile for primary pedestrian fencing was $6.5

million and $1.8 million per mile for vehicular fencing; according to CBP’s

26

Border Patrol began mandating the collection of longitude and latitude coordinates for all

apprehensions in May 2009, and in September 2012, Border Patrol standardized the

collection of turn back and got away data.

27

CBP officials stated CBP did not track funding for acquisition and sustainment for border

fencing prior to implementation of the Secure Fence Act of 2006.

Costs of Acquiring,

Constructing, and

Sustaining TI

Page 17 GAO-17-331 Tactical Infrastructure

2016 rough order of magnitude estimate, these averages remain the

same.

28

CBP estimates that the cost for secondary fencing is approximately $4.2

million per mile but CBP officials identified several limitations of this

estimate. First, due to their limited experience in constructing secondary

fencing, CBP officials noted that they have not constructed sufficient

secondary fencing to use historic costs to estimate an average cost per

mile of the fencing. Currently, around 37 miles, or six percent of the total

654 miles of primary fencing, are backed up by secondary pedestrian

fencing. In addition, CBP officials stated that constructing secondary

fencing in a location with existing primary fencing may result in additional

costs not accounted for in their estimates, such as land acquisition,

removing existing structures, and utility relocations.

According to Border Patrol officials, in 2014, Border Patrol began

implementing the Requirements Management Process. This new process

is designed to facilitate planning in order to fund and deploy TI and other

operational requirements, such as surveillance technology for border

security operations. The Requirements Management Process consists of

six steps as shown in figure 5.

Figure 5: U.S. Border Patrol’s Requirements Management Process

• The initial step requires Border Patrol to identify mission priorities and

goals by analyzing relevant strategic DHS, CBP, and Border Patrol

goals, missions, and objectives from applicable guidance and policies.

In this initial step, the state of the threat is also assessed.

28

GAO-09-896. Cost per mile estimates for primary and secondary fence construction

includes labor, construction and supply chain, planning/oversight, environmental planning,

design, and real estate planning, but does not include the cost of real estate acquisition

including litigation costs, environmental mitigation costs, unforeseen site conditions,

relocation of utilities, removal or retirement of existing structures, and market fluctuations

(e.g. increased fuel costs, labor, raw materials) as well as any other costs not explicitly

stated as included in the estimate.

Border Patrol’s

Requirements

Management Process

Page 18 GAO-17-331 Tactical Infrastructure

• The second step is Mission Analysis. This step is designed to assess

the delta between Border Patrol’s capabilities against currently known

and anticipated threats in order to determine capability gaps in Border

Patrol mission essential tasks. Border Patrol Agents are encouraged

to participate in this step by recommending potential solutions—such

as tactical infrastructure or technology—to mitigate capability gaps.

• The third step—Planning—involves, among other things, determining

potential requirements that may address the identified capability gaps

for funding consideration. To conduct this step, Border Patrol officials

examine the identified capability gaps in detail and determine courses

of action and initial capability requirements. These initial capability

requirements are documented in a sector-specific Initial Requirements

Document.

• The fourth step—Execution—involves Border Patrol executing

courses of action. Border Patrol officials stated that courses of action

are recommended options for Border Patrol commanders and

executives to select and implement. Once implemented, these options

are expected to resolve identified capability gaps in operations,

according to Border Patrol officials.

• The fifth and sixth steps of the process—Assessment and Lifecycle

Management—involve implementing and monitoring solutions to

determine the ability of the requirement to resolve capability gaps and

sectors providing feedback on how the solutions affect border security

operations.

The initial activity to complete step two of the Requirements Management

Process is the Capabilities Gap Analysis Process (CGAP). The CGAP is

intended to identify each station’s capability gaps by determining the

difference between a station’s baseline capabilities and a station’s

required set of capabilities needed to perform mission essential tasks.

The identified shortfall in required capability is a capability gap.

After identifying capability gaps, Border Patrol agents assigned to each

sector are to identify potential solutions to solve or mitigate each gap. For

example, in 2015, as part of the CGAP, agents identified additional

maintenance and repair as a solution where patrol roads were in poor

condition and negatively affected agents’ ability to respond and resolve

illicit activity. Other solutions to capability gaps may include adjustments

to the technologies or personnel deployed in a specific area. For fiscal

year 2015, Border Patrol conducted the CGAP and identified potential

solutions in all nine southwest sectors, according to Border Patrol

officials. Identified solutions and their corresponding capability gaps are to

Page 19 GAO-17-331 Tactical Infrastructure

be documented in Station Capability Gaps Analysis Reports. Figure 6

outlines the steps of the CGAP, and describes an example using the

steps of the CGAP to identify a capability gap and solution.

Figure 6: U.S. Border Patrol’s Capability Gap Analysis Process

Border Patrol officials stated that sectors may request additional TI and

other requirements for border security operations to address capability

gaps not included in the documented CGAP. Officials stated that

additional capability gaps may be identified by sectors or stations during

the course of border security operations that were not captured at the

time a station conducted the process. Border Patrol officials stated that

when stations identify these capability gaps and a need exists for a

requirement to address the capability gap, the station is required to

submit documentation to Border Patrol Headquarters in order for the

requirement to be approved, funded, and subsequently deployed.

According to Border Patrol officials, this documentation should include (1)

the identified capability gap and (2) the new or additional TI or other

requirement and how it addresses the identified capability gap.

Page 20 GAO-17-331 Tactical Infrastructure

According to CBP officials, pedestrian and vehicle fencing have benefited

border security operations in various ways as intended, by (1) supporting

Border Patrol agents’ ability to execute essential tasks; (2) improving

agent safety; and (3) reducing vehicle incursions.

Supporting Agents’ Ability to Execute Mission Essential Tasks.

According to Border Patrol officials, pedestrian fencing is intended to

divert illegal entrants–which include migrants and criminal organizations

that engage in illicit cross-border activities–to areas of the border where

agents can execute their METs and interdict illicit-cross border activities

more effectively.

29

Border Patrol officials told us that populated urban

environments offer an advantageous setting for illegal entrants because

they require only seconds to minutes to blend in with the local U.S.

community after crossing the border. By constructing pedestrian fencing

in more populated urban environments, Border Patrol officials stated that

DHS intended to divert illicit cross-border activities into more remote or

rural environments, where illegal entrants may require hours or days to

reach the nearest U.S. community. For example, Border Patrol officials in

the San Diego sector told us that from 1994 to present, pedestrian

fencing, along with investments in manpower and surveillance

technology, assisted in diverting a large share of illicit cross-border

activity away from the densely populated urban areas near San Diego

and into more rural and remote environments east of the city. Officials

told us that these rural and remote environments east of San Diego

provide an advantage to agents assigned there since they have more

29

For the purposes of this report, illicit cross-border activity refers to any activity in which

people or goods, such as narcotics, money, or weapons, illegally enter the United States.

Fencing Is Intended

to Assist Agents in

Performing Their

Duties, but Its

Contributions to

Border Security

Operations Have Not

Been Assessed

CBP Has Identified the

Intended Benefits of

Pedestrian and Vehicle

Fencing to Border Security

Operations

Page 21 GAO-17-331 Tactical Infrastructure

time to detect, identify, classify, track, respond and resolve the illicit

cross-border activities that occur there. Similarly, Border Patrol officials in

the Tucson sector told us that bollard pedestrian fencing in urban areas

has helped divert much of the illicit cross-border activities that occurred

there into more rural and remote environments where agents are better

able to interdict these activities.

Agents assigned to the Nogales station—within the Tucson sector—told

us that bollard pedestrian fencing has helped divert illicit cross-border

activities away from the City of Nogales and into more rural and remote

areas.

In addition to diverting illicit cross-border activities into more rural and

remote environments, pedestrian fencing is intended to serve as a

physical barrier that impedes and slows the progress of illegal entrants

who attempt to cross the border, and in doing so, provides Border Patrol

agents assigned to these areas additional time and opportunities to

execute their METs, which include detecting, responding, and resolving

illicit cross-border activities. Border Patrol agents in the El Paso sector

told us that pedestrian fencing deployed in the sector’s urban border

environments has assisted in improving agents’ ability to execute their

METs, resulting in higher apprehension rates in these areas. These

agents told us that urban border environments, such as the border

between downtown El Paso from Ciudad Juarez, offer an ideal crossing

point for illegal entrants because they can quickly blend in with the local

U.S population, reach a safe house, or obtain transportation after

crossing the border. However, these agents told us that the primary,

secondary, and tertiary pedestrian fencing that separate downtown El

Paso and Ciudad Juarez have been effective in slowing the progress of

illegal entrants who attempt to cross in this area and providing agents

with additional time to detect, respond, and resolve the illicit cross-border

activities that occur there.

Improving Agent Safety. Border Patrol officials we spoke with in the El

Paso, Tucson, and San Diego sectors stated that modern pedestrian

fencing, including bollard style fencing, improves agent safety during

operations. Specifically, San Diego sector officials told us that modern

style pedestrian fencing reduces illegal entrants’ ability to stage mass

crossings, which can overwhelm agents and jeopardize agents’ safety.

According to Border Patrol officials in the Tucson sector, bollard fencing

has helped reduce agent assaults because this fencing provides agents

with a clear line of sight into Mexico and makes it more difficult for illegal

entrants to ambush agents. These officials told us that older fence

Page 22 GAO-17-331 Tactical Infrastructure

designs, including landing mat fencing, obstruct agents’ line of sight into

Mexico and provided illegal entrants and other individuals in Mexico with

cover and the ability to conceal their location along the border. They

explained that individuals on the Mexican side of the border would

regularly use the landing mat fence to launch surprise assaults on agents

by hurling projectiles, including rocks, from behind it. Border Patrol

officials reported that after replacing legacy landing mat fencing with

bollard pedestrian fencing in the Nogales station, ambushes and assaults

declined. Specifically, Border Patrol officials told us they recorded 376

assaults on agents in the Nogales station in 2010 and 2011, two years

prior to constructing modern bollard pedestrian fencing. In 2012 and

2013, two years following construction, assaults on agents in the Nogales

station dropped to 71, a decline of 81 percent.

Reducing Illicit Vehicular Border Incursions. Vehicle fencing is

intended to serve as a physical barrier that slows and prevents vehicles

engaged in drug trafficking and human smuggling operations from

crossing the border, also known as drive throughs. Vehicle fencing is

typically deployed in more rural and remote environments where criminal

organizations engaged in trafficking and smuggling are more likely to use

vehicles to shorten the time they are at risk of being encountered by

Border Patrol agents. Border Patrol officials in the El Paso and Tucson

sectors told us that they experienced significant decreases in drive

throughs following the deployment of vehicle fencing. Officials in the

Tucson sector reported that vehicle fencing deployed improved Border

Patrol agents’ ability to impede and deny the entry of large amounts of

illegal narcotics transported by motorized vehicles. Officials reported that

rural land tracts within the sector provided criminal organizations with

large areas to traffic narcotics and engage in other illicit cross-border

activities. Border Patrol officials reported that after deploying vehicle

fencing in these areas, drive throughs dropped by an average of 73

percent. Although Tucson sector officials stated vehicle fencing has been

effective in slowing and prohibiting drive throughs, vehicle fencing is not

designed to slow or deter illegal entrants from entering or smuggling

contraband into the United States on foot.

In addition to citing the benefits of pedestrian and vehicle fencing, Border

Patrol officials and agents also identified the various methods used by

illegal entrants to exploit border fencing’s limitations in their attempts to

defeat it. Agents we spoke with in the El Paso and Tucson sectors

explained that one of the most common methods employed by illegal

entrants involves cutting openings, or breaches, in pedestrian and vehicle

Border Patrol Agents

Identified Various

Limitations with Border

Fencing

Page 23 GAO-17-331 Tactical Infrastructure

fencing. Once breached, illegal entrants can cross through the fence or

smuggle people and contraband into the United States. Between fiscal

years 2010 and 2015, CBP recorded a total of 9,287 breaches in

pedestrian fencing. According to our analysis of these data, illegal

entrants breached legacy pedestrian fencing at an average rate of 82

breaches per fence mile, compared to an average of 14 breaches per

fence mile of modern pedestrian fencing.

30

Agents we spoke with in the El Paso sector explained that creating

breaches in legacy pedestrian fencing requires less effort compared to

modern designs, and can be done using bolt or pipe cutters. In addition,

these agents also described observing illegal entrants cutting and

dragging sections of vehicle fencing off the border and illegally entering

the United States in vehicles. Agents we spoke with in the Tucson sector

also told us that while pedestrian fencing is generally easier to breach,

they have also observed breaches in more modern fence designs,

including bollard fence, which agents stated were cut using portable

power tools.

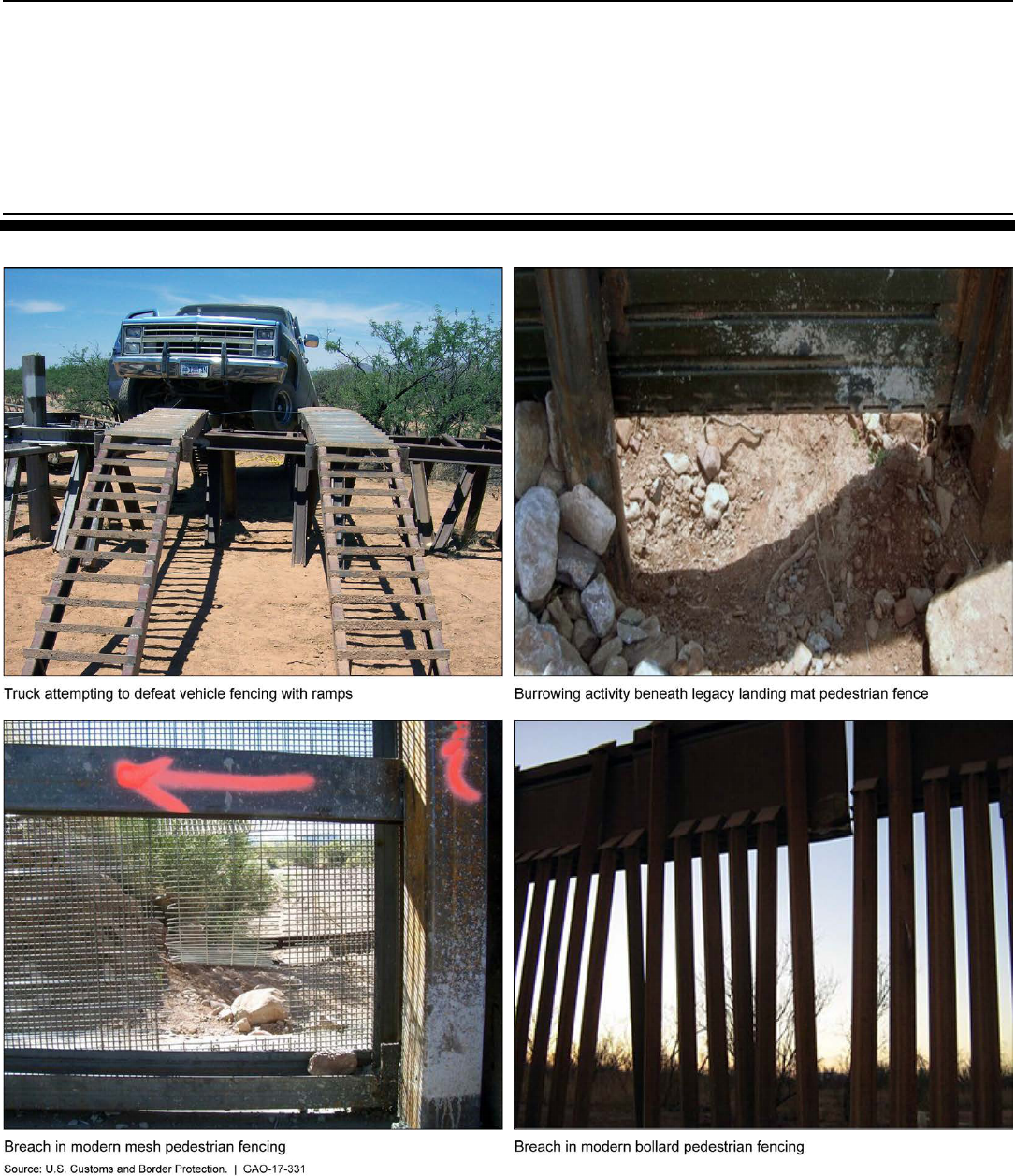

Agents we spoke with in these sectors also described witnessing illegal

entrants defeating border fencing through other methods. For example,

agents we spoke with in the Tucson sector told us they have witnessed

illegal entrants attempting to use ramps to drive vehicles up and over

vehicle fencing in the sector as well as burrowing under legacy pedestrian

fencing, as shown in figure 7. In addition, agents in the Tucson sector

stated that illegal entrants scale the taller pedestrian fencing designs,

such as bollard fencing. In contrast, agents we spoke with in the San

Diego sector stated that some segments of legacy fencing are low and

that they have witnessed illegal entrants jumping over the fence. Other

methods used to defeat border fencing described to us by Border Patrol

agents include using small aircraft to transport contraband over

pedestrian fencing and into the United States and building subterranean

tunnels from Mexico into the United States.

31

30

DHS deemed that specific details about the number of breaches for pedestrian fencing

to be sensitive; therefore, we did not include this information in this report.

31

We have ongoing work on selected smuggling threats along the southwest border,

which include subterranean, aerial, and maritime methods used to smuggle contraband

into the United States. We plan to report on the results of our work in 2017.

Page 24 GAO-17-331 Tactical Infrastructure

Figure 7: Select Methods used by Illegal Entrants to Defeat Border Fencing on the Southwest Border

Page 25 GAO-17-331 Tactical Infrastructure

CBP takes steps to identify intentional destruction or exploitation of

border fencing, including breaches, burrows, and tunnels, and addresses

them when they occur. For example, Border Patrol officials we met with in

the El Paso sector told us that agents regularly identify breaches in

border fencing during patrols. Once identified, agents notify the

appropriate Border Patrol officials at the station and sector level, who in

turn schedule the necessary repair work through one of CBP’s

maintenance and repair contracts, which we discuss later in this report.

CBP collects data that could be useful to assessing the contributions of

border fencing to border security operations at the sector level, but has

not conducted such an assessment. According to CBP, from fiscal year

2007 through 2015, it spent approximately $2.3 billion to deploy border

fencing along the southwest border, and CBP will need to spend a

substantial amount to sustain these investments over their lifetimes. CBP

did not provide a current life-cycle costs estimate to maintain pedestrian

and vehicle fencing, however, in 2009 CBP estimated that maintaining

fencing would cost more than $1 billion over 20 years.

32

Despite these

investments, CBP cannot measure the contribution of fencing to border

security operations along the southwest border because it has not

developed metrics for this assessment. According to CBP officials, CBP

suspended its efforts to measure the contributions of border fencing to

border security in 2013 due to sequestration related funding shortfalls.

CBP officials also stated that border fencing is a part of a system of

capabilities, including Border Patrol agents, surveillance technology, and

other TI, and as a result, developing metrics for a single element of this

system is challenging.

Although CBP does not have metrics to assess the contributions of

border fencing, it does collect data on the location of illegal entries that

can provide insight into where these illegal activities occurred in relation

to the various designs of pedestrian and vehicle fencing at the zone level.

For example, CBP collects data on apprehensions, turn backs, got

aways, and drive throughs, and border fencing, by type and design. CBP

could potentially use these data to develop metrics that compare

estimated known illegal entries before and after fence construction. CBP

could also use these data to help determine the extent to which border

32

CBP’s 2009 Life Cycle Cost Estimate (LCCE) estimated operations and maintenance

costs for fencing would be approximately $1.4 billion from 2009 to 2029.

CBP Has Not Assessed

Pedestrian or Vehicle

Fencing’s Contributions to

Border Security

Operations Along the

Southwest Border

Page 26 GAO-17-331 Tactical Infrastructure

fencing contributes to diverting illegal entrants into more rural and remote

environments as well as border fencing’s impact on apprehension rates

over time However, CBP has not developed metrics that systematically

use these data, or other available information, to assess the contributions

of border fencing to border security operations along the southwest

border. We used these data to conduct a descriptive analysis on (1) the

total estimated known illegal entries, (2) estimated drive throughs, (3)

estimated turn backs and got aways, and (4) apprehension rates of

estimated illegal entries in southwest border zones with border fencing,

by fence type, design, and zone coverage, and in southwest border zones

without border fencing. See Appendix I for more detailed information on

our analysis.

These data, in combination with information on other factors that affect

the location of illegal entries and agents’ ability to predict, detect, identify,

classify, and resolve illicit cross-border activities, could help CBP gain

insight into the contributions of pedestrian and vehicle fencing to border

security operations. For example, the locations of apprehensions, turn

backs, got aways, and drive throughs with the various types and designs

of fencing at the sector and zone level in conjunction with information on

geography, demographics, staffing, technology, and other TI, could help

CBP assess the contributions of border fencing to border security

operations as well as current and future fencing deployments and

replacement projects in light of other resource allocation priorities.

Past GAO reports on leading practices for performance management

have noted that agencies can use performance information to make

decisions that affect future strategies, planning and budgeting, identifying

priorities, and allocating resources.

33

These leading practices also note

that outcome-based performance information should be used for the

allocation of resources and in deciding among competing priorities in a

results oriented management system. We have also found that linking

cost with performance information infuses performance concerns into

planning and budgetary deliberations, prompting agencies to reassess

their performance goals and strategies to more clearly understand the

cost of performance. Performance information also allows program

managers to compare results with goals and thus determine where to

target resources to improve performance.

33

GAO, Managing for Results: Enhancing Agency Use of Performance Information for

Management Decision Making, GAO-05-927 (Washington, D.C.: September 2009).

Page 27 GAO-17-331 Tactical Infrastructure

Developing metrics that can help CBP measure the contributions of

fencing to border security operations along the southwest border, could

better position CBP to make these and other resource allocation

decisions without the best available information to inform competing

mission priorities and investments, such as additional manpower and

surveillance technologies. An assessment of border fencing’s

contributions to border security operations could help position CBP to

identify the cost effectiveness of border fencing compared to other assets

the agency deploys, including Border Patrol agents and various

surveillance technologies. This information would also help position CBP

to justify continued investments in border fencing and, if needed, help

CBP identify future investment priorities, and more effectively target

public resources.

CBP contracts with private contractors who provide sustainment

services— maintenance, repair, and new construction—for TI in the nine

southwest border sectors, which are subdivided into four maintenance

and repair work areas. In providing these sustainment services,

contractors are tasked with identifying and performing routine TI

maintenance and repair requirements, which are classified in five general

categories – (1) fences and gates, (2) roads and bridges, (3) drainage

and grates, (4) lighting and electrical, and (5) vegetation control and

debris removal. Contractors record these requirements in work plans and

submit them to Border Patrol for approval. Once Border Patrol approves

the work plan, the contractors complete the approved TI maintenance and

repair requirements, such as blading a degraded road or clearing and

removing vegetation.

CBP and contractors are to classify maintenance and repair requirements

in each category as urgent or routine. Routine maintenance and repair

CBP Manages TI

Sustainment but

Border Patrol Has Not

Provided Guidance

on its Process for

Identifying and

Deploying TI

CBP Manages the

Sustainment of TI and Has

Taken Steps to Mitigate

Challenges

Page 28 GAO-17-331 Tactical Infrastructure

includes work that is required due to normal wear and tear, deterioration

due to age, and other damage to TI assets not caused by severe weather

events or intentional sabotage. For example, TI contractors may

reposition and upgrade lighting used to illuminate operational areas along

the southwest border. In addition, contractors are to perform routine

maintenance on patrol roads that erode and degrade over time due to

weather and wear and tear caused by the Border Patrol agents who use

them. However, Border Patrol agents from sectors we visited identified

several challenges in sustaining TI, including:

Addressing Maintenance and Repair of Roads on Other Public or

Private Lands. Border Patrol has authority to use public roads owned or

operated by federal, state or local, and tribal entities, as well as certain

privately owned roads, for border security operations.

34

However, sector

officials stated that they face challenges in addressing maintenance and

repair of these roads. Specifically, sector officials in two sectors we visited

told us that it may take time to secure an agreement providing for

maintenance of some roads needed to conduct border security

operations. In addition, sector officials stated that in instances where

portions of a single road have different owners, CBP must enter into

separate agreements with each owner. Officials in one sector stated that

these challenges may hinder CBP’s ability to address maintenance of

roads in a timely manner for use in border security operations.

Funding for TI Sustainment Requirements. CBP has funding allocated

for addressing TI sustainment requirements; however, CBP must

prioritize its requirements to make best use of available funding, and it

can take time to address all requirements. For example, officials in one

sector we visited stated that an increase in its inventory of surveillance

technology has been accompanied by the construction of new roads,

which adds to the sector’s TI inventory. In order to address this increase

in TI inventory, CBP and sector officials stated that they prioritize

maintenance and repair of roads and other requirements in each work

plan based on funding availability and how these requirements affect

border security operations. CBP officials told us that the contractor and

34

See 23 U.S.C. § 101(a)(22), which defines a “public road” as any road or street under

the jurisdiction of and maintained by a public authority and open to public travel. In

addition, Border Patrol is statutorily authorized to, without a warrant, access private lands

(but not dwellings) within 25 miles of the border, for the purpose of patrolling the border to

prevent illegal entry of aliens (see 8 U.S.C. § 1357(a)(3)); and CBP may seek to establish

agreements with private landowners to use, and in certain instances address maintenance

and repair of, their property in furtherance of border security operations.

Page 29 GAO-17-331 Tactical Infrastructure

CBP develop and communicate the work plan to sector officials. Sector

officials then review the work plan and prioritize maintenance and repair

that are critical to border security operations and communicate these

updates to CBP officials for execution. Sector officials in one sector stated

that in general, roads that are critical to border security operations are

prioritized over roads that are less used by agents. Sector officials in this

sector also stated that continually prioritizing the maintenance and repair

of certain roads over others can result in degraded roads in the sector.

Officials in this sector also stated that the use of degraded roads in border

security operations increases the wear and tear on patrol vehicles and

increases the cost of maintaining these vehicles.

While CBP and Border Patrol officials stated they prioritize routine

maintenance requirements that are most critical to border security

operations, contractors are also required to address urgent repair

requirements. Urgent repair requirements are typically the result of severe

weather events or intentional damage to TI assets. CBP requires

contractors to address these requirements within a 24-hour period to

mitigate any negative effects on border security operations. For example,

CBP classifies breaches to fencing, grates, or gates as urgent and

requires immediate repair because, according to Border Patrol officials,

breaches increase illegal entrants’ ability to enter the country unimpeded.

According to Border Patrol officials, the majority of urgent TI repairs on

the southwest border are fence breaches. From fiscal year 2010 through

fiscal year 2015 CBP recorded a total of 9,287 breaches in pedestrian

fencing at an average cost of $784 per breach to repair. Figure 8 shows

an example of a fence breach and subsequent repair.

Page 30 GAO-17-331 Tactical Infrastructure

Figure 8: Fence Breach Due To Drive-Through Entry and Subsequent Repair

While contractors provide routine maintenance and address urgent

repairs on TI, certain TI assets used by Border Patrol become degraded

beyond repair and must be replaced. For example, in the Yuma sector,

Border Patrol officials identified portions of primary legacy pedestrian

fencing that had become so degraded by illegal entrants digging

underneath the fencing and land erosion in the area that it required

additional support to remain erect. In addition, Border Patrol officials in

the El Paso sector stated that while CBP provides routine maintenance

and repair services to the primary legacy pedestrian fencing in Sunland

Park, New Mexico, significant weather events have eroded the foundation

of the fencing. In addition, the erosion in the area has caused damage to

nearby roads used by agents to conduct border security operations.

Sector officials identified, and we observed, primary legacy pedestrian

fencing that leans toward Mexican territory and that required additional

support to prevent the fencing from collapsing. Sector officials noted that

that due to the erosion and terrain in the area, they have been limited in

their repair efforts. See figure 9.

Page 31 GAO-17-331 Tactical Infrastructure

Figure 9: Legacy Pedestrian Fencing in Sunland Park, New Mexico, March 2016

In addition, sector officials identified, and we observed, other primary

legacy pedestrian fencing in Sunland Park, New Mexico, where debris

had accumulated on the Mexican side of the border, reducing the overall

height of the fencing to approximately two feet in certain areas. Officials

told us that the fencing is located three feet from the official U.S. border

and that conducting maintenance on the fencing would require debris

removal machinery that would encroach into Mexican territory. See

figure 10.

Page 32 GAO-17-331 Tactical Infrastructure

Figure 10: Legacy Pedestrian Fencing in Sunland Park, New Mexico, March 2016

Sector officials stated that the condition of the fencing in Sunland Park,

New Mexico, negatively affects border security operations due to its

proximity to populated urban areas on both sides of the border, among

other factors. Border Patrol officials in the El Paso sector stated that the

degraded fencing is located approximately one quarter of a mile from an

urban area on the U.S. side of the border where illegal entrants can

quickly obtain transportation and blend in with the local U.S. population.

While in general, agents stated they have seconds to minutes to interdict

illegal entrants in urban areas, sector officials and agents stated that the

condition of the fencing reduces the time agents have to interdict illicit

cross-border activity because the degraded fencing does not slow down

the progress of illegal entrants. As a result, sector officials stated the

sector deploys additional manpower in the area in order to conduct

effective border security operations.

Page 33 GAO-17-331 Tactical Infrastructure

In addition, sector officials stated that modern pedestrian fencing in

downtown El Paso, Texas, had diverted illegal entrant activity to Sunland

Park, New Mexico, where the primary legacy pedestrian fencing is

compromised. El Paso sector officials stated that while the Sunland Park,

New Mexico, area of operations has the greatest amount of illegal activity

in the El Paso sector, the condition of the primary legacy pedestrian

fencing does not achieve its intended purpose of slowing the progress of

illegal entrants. In addition to the fencing in Sunland Park, Border Patrol

has identified other degraded primary legacy fencing along the southwest

border, such as the Yuma and Tucson sectors.

To address degraded legacy pedestrian fencing, CBP is replacing this

fencing with more modern, bollard style fencing. For example, in fiscal

year 2015, CBP began the process of replacing 1.4 miles of existing

primary pedestrian fencing in Sunland Park, New Mexico—within the El

Paso sector—with new bollard style pedestrian fencing. The fence

replacement project also entails constructing a widened and elevated

patrol road adjacent to the fence and the installation of culverts designed

to mitigate the effects of severe weather events in the area. CBP