BORDERSECURITY

ProgressandChallenges

withtheUseof

Technology,Tactical

Infrastructure,and

PersonneltoSecurethe

SouthwestBorder

Statement of Rebecca Gambler, Director, Homeland

Security & Justice

Accessible Version

Testimony

BeforetheSubcommitteeonBorderand

MaritimeSecurity,Committeeon

HomelandSecurity,Houseof

Representatives

For Release on Delivery

Expected at 2:00 p.m. ET

Thursday, March 15, 2018

GAO-18-397T

Error! No text of specified style in document.

United States Government Accountability Office

United States Government Accountability Office

Highlights of GAO-18-397T, a testimony

before the Subcommittee on Border and

Maritime Security, Committee on Homeland

Security, House of Representatives

March 2018

BORDER SECURITY

Progress and Challenges with the Use of

Technology, Tactical Infrastructure, and Personnel

to Secure the Southwest Border

What GAO Found

The U.S. Border Patrol, within the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) U.S.

Customs and Border Protection (CBP), has made progress deploying surveillance

technology—a mix of radars, sensors, and cameras—along the southwest U.S.

border. As of October 2017, the Border Patrol had completed the planned

deployment of select technologies to several states along the southwest border. The

Border Patrol has also made progress toward assessing performance of surveillance

technologies, but additional actions are needed to fully implement GAO’s 2011 and

2014 recommendations in this area. For example, the Border Patrol has not yet used

available data to determine the contribution of surveillance technologies to border

security efforts.

CBP spent about $2.3 billion to deploy fencing from fiscal years 2007 through 2015

and constructed 654 miles of fencing by 2015. The Border Patrol has reported that

border fencing supports agents’ ability to respond to illicit cross-border activities by

slowing the progress of illegal entrants. GAO reported in February 2017 that CBP

was taking a number of steps in sustaining tactical infrastructure—such as fencing,

roads, and lighting—along the southwest border. However, CBP has not developed

metrics that systematically use data it collects to assess the contributions of border

fencing to its mission, as GAO has recommended. CBP concurred with the

recommendation and plans to develop metrics by January 2019. Further, CBP

established the Border Wall System Program in response to a January 2017

executive order that called for the immediate construction of a southwest border wall.

This program is intended to replace and add to existing barriers along the southwest

border. In April 2017, DHS leadership gave CBP approval to procure barrier

prototypes, which are intended to help inform new design standards for the border

wall system.

Physical Barriers in San Diego, California, April 2016

The Border Patrol has faced challenges in achieving a staffing level of 21,370

agents, the statutorily-established minimum from fiscal years 2011 through 2016. As

of September 2017, the Border Patrol reported it had about 19,400 agents. GAO

reported in November 2017 that Border Patrol officials cited staffing shortages as a

challenge for optimal deployment. As a result, officials had to make decisions about

how to prioritize activities for deployment given the number of agents available.

View GAO-18-397T. For more information,

contact Rebecca Gambler at (202) 512-8777

Why GAO Did This Study

DHS has employed a variety of

technology, tactical infrastructure, and

personnel assets to help secure the

nearly 2,000 mile long southwest border.

Since 2009, GAO has issued over 35

products on the progress and challenges

DHS has faced in using technology,

infrastructure, and other resources to

secure the border. GAO has made over

50 recommendations to help improve

DHS’s efforts, and DHS has implemented

more than half of them.

This statement addresses (1) DHS efforts

to deploy and measure the effectiveness

of surveillance technologies, (2) DHS

efforts to maintain and assess the

effectiveness of existing tactical

infrastructure and to deploy new physical

barriers, and (3) staffing challenges the

Border Patrol has faced. This statement

is based on three GAO reports issued in

2017, selected updates conducted in

2017, and ongoing work related to DHS

acquisitions and the construction of

physical barriers. For ongoing work GAO

analyzed DHS and CBP documents,

interviewed officials within DHS, and

visited border areas in California.

What GAO Recommends

In recent reports, GAO made or

reiterated recommendations for DHS to,

among other things, assess the

contributions of technology and fencing

to border security. DHS generally agreed,

and has actions planned or underway to

address these recommendations.

Letter

Page 1 GAO-18-397T Border Security

Letter

Chairwoman McSally, Ranking Member Vela, and Members of the

Subcommittee:

I am pleased to be here today to discuss GAO’s work reviewing the

Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) efforts to deploy surveillance

technology, tactical infrastructure, and personnel resources to the

southwest border. This area continues to be vulnerable to illegal cross-

border activity. The U.S. Border Patrol reported apprehending almost

304,000 illegal entrants and making over 11,600 drug seizures along the

southwest border in fiscal year 2017. In January 2017, an executive order

called for, among other things, the immediate construction of a southwest

border wall and the hiring of 5,000 additional Border Patrol agents,

subject to available appropriations.

1

The Border Patrol, within DHS’s U.S. Customs and Border Protection

(CBP), is the federal agency responsible for securing the national borders

between U.S. ports of entry.

2

The Border Patrol divides responsibility for

southwest border security operations geographically among nine sectors,

and each sector is further divided into varying numbers of stations. To

respond to cross-border threats, DHS has employed a combination of key

resources, including surveillance technology, tactical infrastructure (which

includes fencing, roads, and lighting), and Border Patrol agents. For

example, DHS has deployed a variety of land-based surveillance

technologies, such as cameras and sensors, which the Border Patrol

uses to assist its efforts to secure the border and to apprehend individuals

1

Border Security and Immigration Enforcement Improvements, Exec. Order No. 13767, §§

2, 8 (Jan. 25, 2017), 82 Fed. Reg. 8793, 8795 (Jan. 30, 2017). The executive order

defines “wall” as a contiguous, physical wall or other similarly secure, contiguous, and

impassable physical barrier.

2

See 6 U.S.C. § 211(a) (establishing CBP within DHS), (c) (enumerating CBP’s duties), (e)

(establishing and listing duties of the U.S. Border Patrol within CBP). Ports of entry are

facilities that provide for the controlled entry into or departure from the United States.

Specifically, a port of entry is any officially designated location (seaport, airport, or land

border location) where DHS officers or employees are assigned to clear passengers and

merchandise, collect duties, and enforce customs laws, and where DHS officers inspect

persons entering or applying for admission into, or departing the United States pursuant to

U.S. immigration law and travel controls.

Letter

attempting to cross the border illegally.

Page 2 GAO-18-397T Border Security

3

In addition, CBP spent

approximately $2.4 billion from fiscal years 2007 through 2015 to deploy

tactical infrastructure, including about $2.3 billion on fencing, at locations

along the nearly 2,000 mile long southwest border. The Border Patrol

deploys agents along the immediate border and in areas up to 100 miles

from the border as part of a layered approach the agency refers to as the

defense in depth strategy, and the Border Patrol reported it had 16,605

agents staffed at southwest border sectors at the end of fiscal year 2017.

4

Since 2009 we have issued over 35 products on the progress DHS and

its components have made and challenges it faces in using surveillance

technology, tactical infrastructure, personnel, and other resources to

secure the southwest border.

5

As a result of this work, we have made

over 50 recommendations to help improve DHS oversight over efforts to

secure the southwest border, and DHS has implemented more than half

of them. My statement describes (1) DHS efforts to deploy and measure

the effectiveness of surveillance technologies, (2) DHS efforts to maintain

and assess the effectiveness of existing tactical infrastructure and deploy

new physical barriers, and (3) staffing challenges the Border Patrol has

faced.

This statement is based on three reports we issued in 2017, and on

selected updates we conducted in November and December 2017 on the

Border Patrol’s efforts to address some of our previous

3

In November 2005, DHS launched the Secure Border Initiative (SBI) to develop a

comprehensive border protection system using technology, known as the Secure Border

Initiative Network (SBInet). Under the SBInet program, CBP acquired 15 fixed-tower

systems at a cost of nearly $1 billion, which are deployed along 53 miles of Arizona’s 387-

mile border with Mexico. In January 2011, in response to internal and external

assessments that identified concerns, the Secretary of Homeland Security announced the

cancellation of further procurements of SBInet surveillance systems. That same month,

CBP introduced the Arizona Border Surveillance Technology Plan. In June 2014, CBP

developed the Southwest Border Technology Plan, which incorporates the Arizona

Technology Plan, and plans to extend land-based surveillance technology deployments to

the remainder of the southwest border.

4

As part of this strategy, the Border Patrol deploys some agents to activities along the

immediate border while other agents may be assigned to activities further from the border,

such as immigration checkpoint operations that are generally located on highways 25 to

100 miles from the border.

5

See Related GAO Products page.

Letter

recommendations.

Page 3 GAO-18-397T Border Security

6

This statement also includes preliminary observations

and analyses from ongoing work related to the construction of new and

replacement physical barriers along the southwest border and our fourth

annual assessment of select DHS major acquisition programs.

7

Our

reports and testimonies, along with selected updates, incorporated

information we obtained and analyzed from officials at various DHS

components, and during site visits along the southwest border. More

detailed information about our scope and methodology can be found in

our published reports and testimonies. For ongoing work, we reviewed

acquisition documents, such as CBP’s Concept of Operations for

Impedance and Denial, the Wall System Operational Requirements

Document, and the Border Wall Prototype Test Plan. We also met with

officials from DHS components, including CBP’s Office of Facilities and

Management and the Border Patrol, from September 2017 to January

2018. Further, in December 2017 we conducted a site visit to California to

view existing tactical infrastructure and border wall prototypes that will

inform the design of future physical barriers along the southwest border.

All of our work was conducted in accordance with generally accepted

government auditing standards. Those standards require that we plan

and perform the audit to obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide

a reasonable basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit

objectives. We believe that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable

basis for our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

CBPHasMadeProgressDeploying

SurveillanceTechnologyalongtheSouthwest

6

GAO, Southwest Border Security: Border Patrol Is Deploying Surveillance Technologies

but Needs to Improve Data Quality and Assess Effectiveness, GAO-18-119 (Washington,

D.C.: Nov. 30, 2017); Southwest Border Security: Additional Actions Needed to Better

Assess Fencing’s Contributions and Provide Guidance for Identifying Capability Gaps,

GAO-17-331 (Washington, D.C.: Feb.16, 2017); Border Patrol: Issues Related to Agent

Deployment Strategy and Immigration Checkpoints, GAO-18-50 (Washington, D.C.: Nov.

8, 2017).

7

We plan to complete the current annual assessment of DHS major acquisition programs

in spring 2018. For the most recently published report, see: GAO, Homeland Security

Acquisitions: Earlier Requirements Definition and Clear Documentation of Key Decisions

Could Facilitate Ongoing Progress, GAO-17-346SP (Washington, D.C.: Apr. 6, 2017). We

plan to complete the review related to the construction of new and replacement physical

barriers along the southwest border later this year.

Letter

Border,butHasNotFullyAssessed

Effectiveness

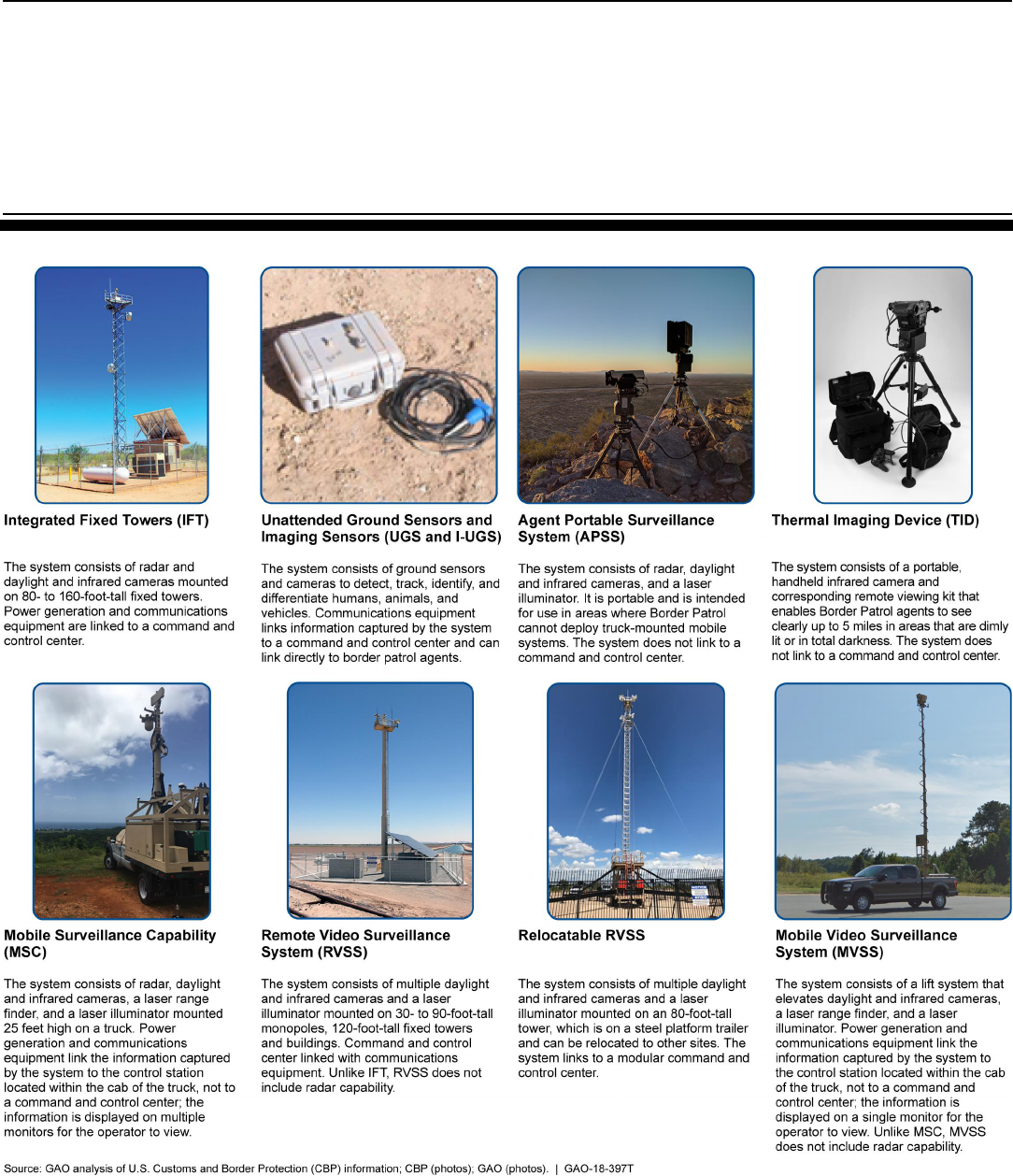

On multiple occasions since 2011, we have reported on the progress the

Border Patrol has made deploying technologies along the southwest

border. Figure 1 shows the land-based surveillance technology systems

used by the Border Patrol.

Page 4 GAO-18-397T Border Security

Letter

Figure 1: Border Surveillance Technology Systems Used by the Border Patrol

Page 5 GAO-18-397T Border Security

Letter

In November 2017, we reported on the progress the Border Patrol made

deploying technology along the southwest border in accordance with its

2011 Arizona Technology Plan and 2014 Southwest Border Technology

Plan.

Page 6 GAO-18-397T Border Security

8

For example, we reported that, according to officials, the Border

Patrol had completed deployments of all planned Remote Video

Surveillance Systems (RVSS), Mobile Surveillance Capability systems,

and Unattended Ground Sensors, as well as 15 of 53 Integrated Fixed

Tower systems to Arizona. The Border Patrol had also completed

deployments of select technologies to Texas and California, including

deploying 32 Mobile Surveillance Capability systems. In addition, the

Border Patrol had efforts underway to deploy other technology programs,

but at the time of our report, some of those programs had not yet begun

deployment or were not yet under contract. For example, we reported

that, according to the Border Patrol officials responsible for the RVSS

program, the Border Patrol had begun planning the designs of the

command and control centers and towers for the Rio Grande Valley

sector in Texas. Further, we reported that the Border Patrol had not yet

initiated deployments of RVSS to Texas because, according to Border

Patrol officials, the program had only recently completed contract

negotiations for procuring those systems. Additionally, the Border Patrol

initially awarded the contract to procure and deploy Mobile Video

Surveillance System units to Texas in 2014, but did not award the

contract until 2015 because of bid and size protests, and the vendor that

was awarded the contract did not begin work until March 2016.

9

Our

November 2017 report includes more detailed information about the

deployment status of surveillance technology along the southwest border

as of October 2017.

We also reported in November 2017 that the Border Patrol had made

progress identifying performance metrics for the technologies deployed

along the Southwest Border, but additional actions are needed to fully

implement our prior recommendations in this area. For example, in

November 2011, we found that CBP did not have the information needed

to fully support and implement the Arizona Technology Plan and

recommended that CBP (1) determine the mission benefits to be derived

8

GAO-18-119.

9

A bid protest, filed with GAO, is a dispute in which the protester alleges that a federal

agency has not complied with statutes and regulations controlling government

procurements. A size protest, filed with the Small Business Administration, is a challenge

of the determination that an awardee of a small business set-aside contract meets the

definition of “small business” in order to be eligible for the set-aside.

Letter

from implementation of the Arizona Technology Plan and (2) develop and

apply key attributes for metrics to assess program implementation.

Page 7 GAO-18-397T Border Security

10

CBP

concurred with our recommendations and has implemented one of them.

Specifically, in March 2014, we reported that CBP had identified mission

benefits of its surveillance technologies to be deployed along the

southwest border, such as improved situational awareness and agent

safety. However, the agency had not developed key attributes for

performance metrics for all surveillance technologies to be deployed.

11

Further, we reported in March 2014 that CBP did not capture complete

data on the contributions of these technologies. When used in

combination with other relevant performance metrics or indicators, these

data could be used to better determine the impact of CBP’s surveillance

technologies on CBP’s border security efforts and inform resource

allocation decisions. Therefore, we recommended that CBP (1) require

data on technology contributions to apprehensions or seizures to be

tracked and recorded within its database and (2) subsequently analyze

available data on apprehensions and technological assists—in

combination with other relevant performance metrics or indicators, as

appropriate—to determine the contribution of surveillance technologies.

CBP concurred with our recommendations and has implemented one of

them. Specifically, in June 2014, the Border Patrol issued guidance

informing agents that the asset assist data field—which records assisting

technology or other assets (canine teams)—in its database had become a

mandatory data field.

While the Border Patrol has taken action to collect data on technology, it

has not taken additional steps to determine the contribution of

surveillance technologies to CBP’s border security efforts. In April 2017,

we reported that the Border Patrol had provided us a case study that

assessed technology assist data, along with other measures, to

determine the contributions of surveillance technologies to its mission.

12

We reported that this was a helpful step in developing and applying

10

GAO, Arizona Border Surveillance Technology: More Information on Plans and Costs Is

Needed before Proceeding, GAO-12-22 (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 4, 2011).

11

GAO, Arizona Border Surveillance Technology Plan: Additional Actions Needed to

Strengthen Management and Assess Effectiveness, GAO-14-368 (Washington, D.C.: Mar.

3, 2014).

12

GAO, 2017 Annual Report: Additional Opportunities to Reduce Fragmentation, Overlap,

and Duplication and Achieve Other Financial Benefits, GAO-17-491SP (Washington, D.C.:

Apr. 26, 2017).

Letter

performance metrics; however, the case study was limited to one border

location and the analysis was limited to select technologies. In November

2017, we reported that Border Patrol officials demonstrated the agency’s

new Tracking, Sign Cutting, and Modeling (TSM) system, which they said

is intended to connect between agents’ actions (such as identification of a

subject through the use of a camera) and results (such as an

apprehension) and allow for more comprehensive analysis of the

contributions of surveillance technologies to the Border Patrol’s mission.

One official said that data from the TSM will have the potential to provide

decision makers with performance indicators, such as changes in

apprehensions or traffic before and after technology deployments.

However, at the time of our review, TSM was still early in its use and

officials confirmed that it was not yet used to support such analytic efforts.

We continue to believe that it is important for the Border Patrol to assess

technologies’ contributions to border security and will continue to monitor

the progress of the TSM and other Border Patrol efforts to meet our 2011

and 2014 recommendations.

CBPIsPlanningtoConstructNewPhysical

Page 8 GAO-18-397T Border Security

Barriers,butHasNotYetAssessedtheImpact

ofExistingFencing

FencingIsIntendedtoAssistAgentsinPerformingTheir

Duties,butItsContributionstoBorderSecurity

OperationsHaveNotBeenAssessed

We have reported on the significant investments CBP has made in

tactical infrastructure along the southwest border. The Illegal Immigration

Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 (IIRIRA), as amended,

provides that the Secretary of Homeland Security shall take actions, as

necessary, to install physical barriers and roads in the vicinity of the

border to deter illegal crossings in areas of high illegal entry.

13

The

Secure Fence Act of 2006, in amending IIRIRA, required DHS to

construct at least two layers of reinforced fencing as well as physical

barriers, roads, lighting, cameras, and sensors on certain segments of the

13

Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 (IIRIRA), Pub. L.

No. 104-208, div. C, tit. I, subtit. A, § 102(a), 110 Stat. 3009, 3009-554 (classified, as

amended, at 8 U.S.C. § 1103 note).

Letter

southwest border.

Page 9 GAO-18-397T Border Security

14

From fiscal years 2005 through 2015, CBP increased

the total miles of primary border fencing on the southwest border from

119 miles to 654 miles—including 354 miles of primary pedestrian fencing

and 300 miles of primary vehicle fencing.

15

In addition, CBP has deployed

additional layers of pedestrian fencing behind the primary border fencing,

including 37 miles of secondary fencing.

16

From fiscal years 2007 through

2015, CBP spent approximately $2.4 billion on tactical infrastructure on

the southwestern border—and about 95 percent, or around $2.3 billion,

was spent on constructing pedestrian and vehicle fencing. CBP officials

reported it will need to spend additional amounts to sustain these

investments over their lifetimes. In 2009, CBP estimated that maintaining

fencing would cost more than $1 billion over 20 years.

17

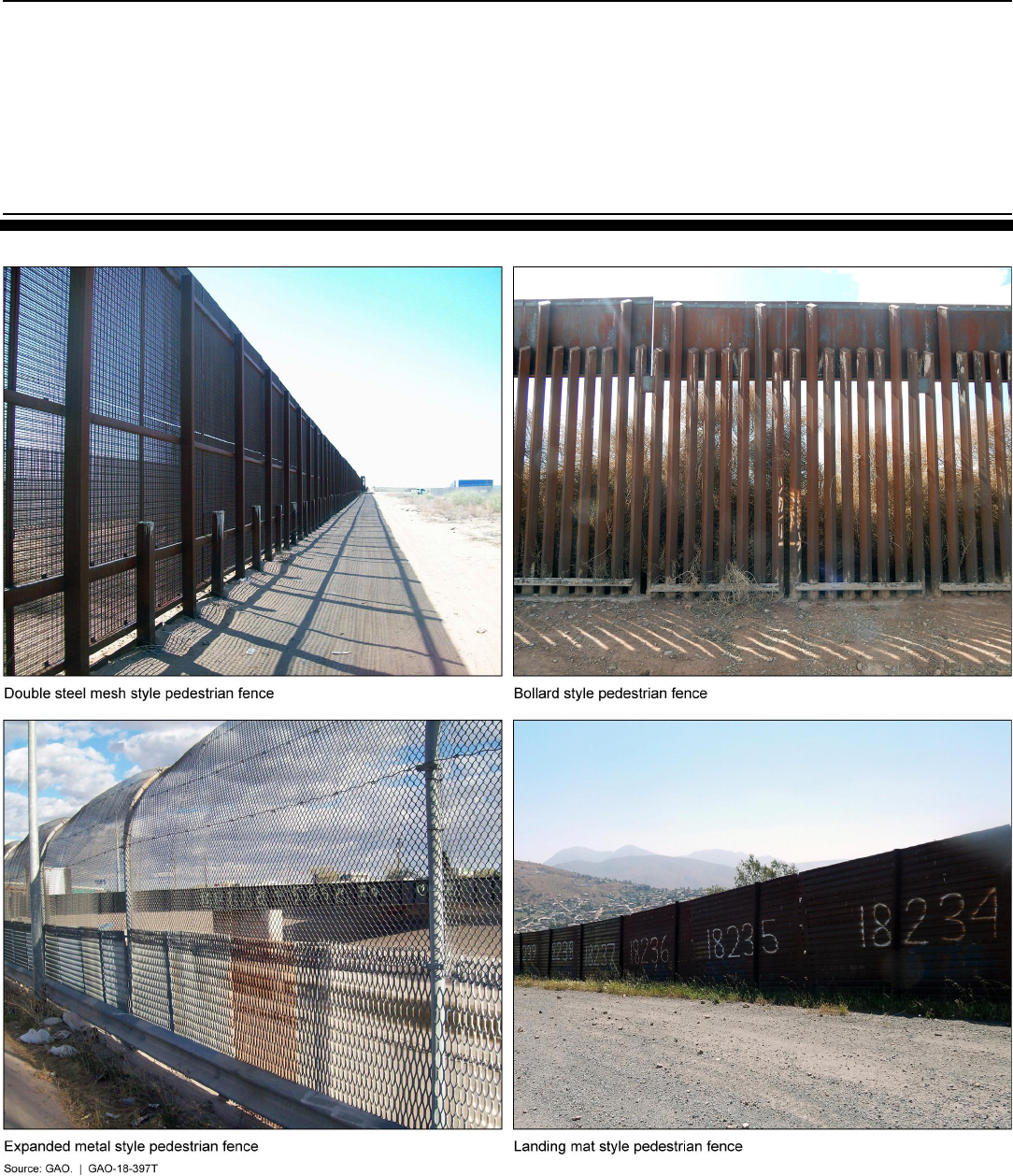

CBP used

various fencing designs to construct the 654 miles of primary pedestrian

and vehicle border fencing. Figure 2 shows examples of existing

pedestrian fencing deployed along the border.

14

See Pub. L. No. 109-367, § 3, 120 Stat. 2638, 2638-2639. Under the Secure Fence Act

of 2006, the Secretary of Homeland Security is to achieve and maintain operational

control over the borders of the United States through surveillance activities and physical

infrastructure enhancements to prevent unlawful entry by aliens and facilitate CBP’s

access to the borders. See id. § 2, 120 Stat. at 2638 (classified at 8 U.S.C. § 1701 note).

Subsequently, the DHS Appropriations Act, 2008, rewrote the border fencing requirements

section of IIRIRA to require that DHS construct not less than 700 miles of reinforced

fencing along the southwest border where fencing would be most practical and effective,

and to provide for the installation of additional physical barriers, roads, lighting, cameras,

and sensors to gain operational control of the southwest border. IIRIRA § 102(b), 110

Stat. at 3009-554 to -555, as amended by Pub. L. No. 110-161, div. E, tit. V, §

564(a)(2)(B)(ii), 121 Stat. 1844, 2090-91 (2007) (classified at 8 U.S.C. § 1103 note).

IIRIRA § 102(b), as amended, also gives the Secretary of Homeland Security discretion to

install tactical infrastructure in particular locations along the border, as deemed

appropriate. Id.

15

See 8 U.S.C. § 1103 note (notwithstanding fencing requirements, DHS is not required to

install fencing or other resources in a particular location along the border if the Secretary

of Homeland Security determines that the use or placement of such resources is not the

most appropriate means to achieve and maintain operational control over the border at

that location).

16

The first layer of fencing, the primary fence, may include both pedestrian and vehicle

fencing and is the first fence encountered when moving north from the border; the

secondary fence, located behind the primary fence, consists solely of pedestrian fencing;

and the third layer, or tertiary fence, is primarily used to delineate property lines rather

than deter illegal entries.

17

CBP’s 2009 life cycle cost estimate estimated operations and maintenance costs for

fencing would be approximately $1.4 billion from 2009 through 2029.

Letter

Figure 2: Selected Designs of Existing Pedestrian Fencing on the Southwest Border

Page 10 GAO-18-397T Border Security

Note: For the purposes of this statement, we refer to fencing constructed prior to January 2017 as

“existing” fencing or barriers. A January 2017 executive order called for the immediate construction of

a “contiguous, physical wall or other similarly secure, contiguous, and impassable physical barrier”

and CBP is assessing prototypes to inform future designs of barriers. See Exec. Order No. 13767, § 2

(Jan. 25, 2017), 82 Fed. Reg. 8793 (Jan. 30, 2017).

Letter

In February 2017, we reported that border fencing had benefited border

security operations in various ways, according to the Border Patrol.

Page 11 GAO-18-397T Border Security

18

For

example, according to officials, border fencing improved agent safety,

helped reduce vehicle incursions, and supported Border Patrol agents’

ability to respond to illicit cross-border activities by slowing the progress

of illegal entrants. However, we also found that, despite its investments

over the years, CBP could not measure the contribution of fencing to

border security operations along the southwest border because it had not

developed metrics for this assessment. We reported that CBP collected

data that could help provide insight into how border fencing contributes to

border security operations. For example, we found that CBP collected

data on the location of illegal entries that could provide insight into where

these illegal activities occurred in relation to the location of various

designs of pedestrian and vehicle fencing. We reported that CBP could

potentially use these data to compare the occurrence and location of

illegal entries before and after fence construction, as well as to help

determine the extent to which border fencing contributes to diverting

illegal entrants into more rural and remote environments, and border

fencing’s impact, if any, on apprehension rates over time. Therefore, we

recommended in February 2017 that the Border Patrol develop metrics to

assess the contributions of pedestrian and vehicle fencing to border

security along the southwest border using the data the Border Patrol

already collects and apply this information, as appropriate, when making

investment and resource allocation decisions. The agency concurred with

our recommendation. As of December 2017, officials reported that CBP

plans to establish initial metrics by March 2018 and finalize them in

January 2019.

CBPFacesChallengesinSustainingTactical

InfrastructureandHasNotProvidedGuidanceonIts

ProcessforIdentifyingandDeployingTactical

Infrastructure

In February 2017, we also reported that CBP was taking a number of

steps to sustain tactical infrastructure along the southwest border;

however, it continued to face certain challenges in maintaining this

infrastructure.

19

For example, CBP had funding allocated for tactical

18

GAO-17-331.

19

For the purpose of this statement, sustainment refers to the maintenance, repair, and

replacement of tactical infrastructure.

Letter

infrastructure sustainment requirements, but had not prioritized its

requirements to make the best use of available funding, since CBP also

required contractors to address urgent repair requirements. According to

Border Patrol officials, CBP classifies breaches to fencing, grates, or

gates as urgent and requiring immediate repair because breaches

increase illegal entrants’ ability to enter the country unimpeded. At the

time of our February 2017 review, the majority of urgent tactical

infrastructure repairs on the southwest border were fence breaches,

according to Border Patrol officials. From fiscal years 2010 through 2015,

CBP recorded a total of 9,287 breaches in pedestrian fencing, and repair

costs averaged $784 per breach.

While contractors provide routine maintenance and address urgent

repairs on tactical infrastructure, certain tactical infrastructure assets used

by the Border Patrol—such as border fencing—become degraded beyond

repair and must be replaced. For example, in February 2017 we reported

that CBP had provided routine maintenance and repair services to the

primary legacy pedestrian fencing in Sunland Park, New Mexico.

However, significant weather events had eroded the foundation of the

fencing, according to the Border Patrol officials in the El Paso sector, and

in 2015 CBP began to replace 1.4 miles of primary pedestrian fence in

this area. We also reported on several additional CBP projects to replace

degraded, legacy pedestrian fencing with more modern, bollard style

fencing. For example, in fiscal year 2016, CBP began removing and

replacing an estimated 7.5 miles of legacy primary pedestrian fencing

with modern bollard style fencing within the Tucson sector. In addition,

from fiscal years 2011 through 2016, CBP completed four fence

replacement projects that replaced 14.1 miles of primary pedestrian

legacy fencing in the Tucson and Yuma sectors at a total cost of

approximately $68.26 million and an average cost of $4.84 million per

mile of replacement fencing. We plan to provide information on additional

fence replacement projects in a forthcoming report.

In 2014, the Border Patrol began implementing the Requirements

Management Process that is designed to facilitate planning for funding

and deploying tactical infrastructure and other requirements, according to

Border Patrol officials. At the time of our February 2017 review, Border

Patrol headquarters and sector officials told us that the Border Patrol

lacked adequate guidance for identifying, funding, and deploying tactical

infrastructure needs as part of this process. In addition, officials reported

experiencing some confusion about their roles and responsibilities in this

process. We reported that developing guidance on this process would

provide more reasonable assurance that the process is consistently

Page 12 GAO-18-397T Border Security

Letter

followed across the Border Patrol. We therefore recommended that the

Border Patrol develop and implement written guidance to include roles

and responsibilities for the steps within its requirements process for

identifying, funding, and deploying tactical infrastructure assets for border

security operations. The agency concurred with this recommendation and

stated that it planned to update the Requirements Management Process

and, as part of that update, planned to add communication and training

methods and tools to better implement the process. As of December

2017, DHS plans to complete these efforts by September 2019.

CBPHasTestedBarrierPrototypesandPlansto

Page 13 GAO-18-397T Border Security

ConstructNewBarriersinSanDiegoandRioGrande

ValleySectors

In response to the January 2017 Executive Order, CBP established the

Border Wall System Program to replace and add to existing barriers along

the southwest border. In April 2017, DHS leadership authorized CBP to

procure barrier prototypes, which are intended to help refine requirements

and inform new or updated design standards for the border wall system.

CBP subsequently awarded eight contracts with a total value of $5 million

for the construction, development, and testing of the prototypes. From

October to December 2017, CBP tested eight prototypes—four

constructed from concrete and four from other materials—and evaluated

them in five areas: breachability, scalability, constructability, design, and

aesthetics. CBP officials said the prototype evaluation results are

expected by March 2018.

CBP has selected the San Diego and Rio Grande Valley sectors for the

first two segments of the border wall system. In the San Diego sector,

CBP plans to replace 14 miles of existing primary and secondary barriers.

The primary barriers will be rebuilt to existing design standards, but the

secondary barriers will be rebuilt to new design standards once

established. In the Rio Grande Valley sector, CBP plans to extend an

existing barrier by 60 miles using existing design standards. CBP intends

to prioritize construction of new or replacement physical barriers based on

threat levels, land ownership, and geography, among other things. We

have ongoing work reviewing the Border Wall System Program, and we

plan to report on the results of that work later this year.

Letter

TheBorderPatrolHasContinuedtoFace

Page 14 GAO-18-397T Border Security

StaffingChallenges

In November 2017 we reported that, in fiscal years 2011 through 2016,

the Border Patrol had statutorily-established minimum staffing levels of

21,370 full-time equivalent agent positions, but the Border Patrol has

faced challenges in staffing to that level.

20

Border Patrol headquarters,

with input from the sectors, determines how many authorized agent

positions are allocated to each of the sectors. According to Border Patrol

officials, these decisions take into account the relative needs of the

sectors, based on threats, intelligence, and the flow of illegal activity.

Each sector’s leadership determines how many of the authorized agent

positions will be allocated to each station within their sector.

At the end of fiscal year 2017, the Border Patrol reported it had over

19,400 agents on board nationwide, and that over 16,600 of the agents

were staffed to sectors along the southwest border. As mentioned earlier,

the January 2017 executive order called for the hiring of 5,000 additional

Border Patrol agents, subject to available appropriations, and as of

November 2017 we reported that the Border Patrol planned to have

26,370 agents by the end of fiscal year 2021. The Acting Commissioner

of CBP reported in a February 2017 memo to the Deputy Secretary for

Homeland Security that from fiscal year 2013 to fiscal year 2016, the

Border Patrol hired an average of 523 agents per year while experiencing

20

GAO-18-50. Department of Defense and Full-Year Continuing Appropriations Act, 2011,

Pub. L. No. 112-10, div. B, tit. VI, § 1608, 125 Stat. 38, 140; Consolidated Appropriations

Act, 2012, Pub. L. No. 112-74, div. D, tit. II, 125 Stat. 786, 946 (2011); Consolidated and

Further Continuing Appropriations Act, 2013, Pub. L. No. 113-6, div. D, tit. II, 127 Stat.

198, 345; Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2014, Pub. L. No. 113-76, div. F, tit. II, 128

Stat. 5, 249; Department of Homeland Security Appropriations Act, 2015, Pub. L. No. 114-

4, tit. II, 129 Stat. 39, 41; Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2016, Pub. L. No. 114-113, div.

F, tit. II, 129 Stat. 2242, 2495 (2015). For fiscal year 2017, the Consolidated

Appropriations Act, 2017, did not include the provision from prior years mandating a

workforce floor for Border Patrol agents, but the accompanying explanatory statement

directed CBP to continue working to develop a fully justified workforce staffing model that

would provide validated requirements for all U.S. borders and to brief the appropriations

committees on its progress in this regard within 30 days of the enactment of the

Consolidated Appropriations Act (enacted May 5, 2017). See Explanatory Statement, 163

Cong. Rec. H3327, H3809-10 (daily ed. May 3, 2017), accompanying Pub. L. No. 115-31,

131 Stat. 135 (2017).

Letter

a loss of an average of 904 agents per year.

Page 15 GAO-18-397T Border Security

21

The memo cited

challenges such as competing with other federal, state, and local law

enforcement organizations for applicants. In particular, the memo noted

that CBP faces hiring and retention challenges compared to DHS’s U.S.

Immigration and Customs Enforcement (which is also planning to hire

additional law enforcement personnel) because CBP’s hiring process

requires applicants to take a polygraph examination, Border Patrol agents

are deployed to less desirable duty locations, and Border Patrol agents

generally receive lower compensation.

In November 2017, we reported that the availability of agents is one key

factor that affects the Border Patrol’s deployment strategy. In particular,

officials from all nine southwest border sectors cited current staffing levels

and the availability of agents as a challenge for optimal deployment. We

reported that, as of May 2017, the Border Patrol had 17,971 authorized

agent positions in southwest border sectors, but only 16,522 of those

positions were filled—a deficit of 1,449 agents—and eight of the nine

southwest border sectors had fewer agents than the number of

authorized positions. As a result of these staffing shortages, resources

were constrained and station officials had to make decisions about how to

prioritize activities for deployment given the number of agents available.

We also reported in November 2017 that within sectors, some stations

may be comparatively more understaffed than others because of

recruitment and retention challenges, according to officials. Generally,

sector officials said that the recruitment and retention challenges

associated with particular stations were related to quality of life factors in

the area near the station—for example, agents may not want to live with

their families in an area without a hospital, with low-performing schools, or

with relatively long commutes from their homes to their duty station. This

can affect retention of existing agents, but it may also affect whether a

new agent accepts a position in that location. For example, officials in one

sector said that new agent assignments are not based solely on agency

need, but rather also take into consideration agent preferences. These

officials added that there is the potential that new agents may decline

offers for stations that are perceived as undesirable, or they may resign

their position earlier than they otherwise would to pursue employment in a

more desirable location. We have ongoing work reviewing CBP’s efforts

21

The Acting Commissioner’s memo outlines plans and requests to assist the Border

Patrol in hiring more agents, including the additional 5,000 agents called for in the

Executive Order on Border Security and Immigration Enforcement Improvements.

Letter

to recruit, hire, and retain its law enforcement officers, including Border

Patrol agents.

Chairwoman McSally, Ranking Member Vela, and Members of the

Subcommittee, this concludes my prepared statement. I will be happy to

answer any questions you may have.

GAOContactandStaffAcknowledgments

Page 16 GAO-18-397T Border Security

For questions about this statement, please contact Rebecca Gambler at

(202) 512-8777 or [email protected]. Contact points for our Offices of

Congressional Relations and Public Affairs may be found on the last page

of this statement. Individuals making key contributions to this testimony

are Jeanette Henriquez (Assistant Director), Leslie Sarapu (Analyst-in-

Charge), Ashley Davis, Alana Finley, Tom Lombardi, Marycella Mierez,

and Claire Peachey.

Related GAO Products

Page 17 GAO-18-397T Border Security

RelatedGAOProducts

Southwest Border Security: Border Patrol Is Deploying Surveillance

Technologies but Needs to Improve Data Quality and Assess

Effectiveness. GAO-18-119. Washington, D.C.: November 30, 2017.

Border Patrol: Issues Related to Agent Deployment Strategy and

Immigration Checkpoints. GAO-18-50. Washington, D.C.: November 8,

2017.

2017 Annual Report: Additional Opportunities to Reduce Fragmentation,

Overlap, and Duplication and Achieve Other Financial Benefits. GAO-17-

491SP. Washington, D.C.: April 26, 2017.

Homeland Security Acquisitions: Earlier Requirements Definition and

Clear Documentation of Key Decisions Could Facilitate Ongoing

Progress. GAO-17-346SP. Washington, D.C.: April 6, 2017.

Southwest Border Security: Additional Actions Needed to Better Assess

Fencing’s Contributions to Operations and Provide Guidance for

Identifying Capability Gaps. GAO-17-331. Washington, D.C.: February

16, 2017.

Southwest Border Security: Additional Actions Needed to Better Assess

Fencing’s Contributions to Operations and Provide Guidance for

Identifying Capability Gaps. GAO-17-167SU. Washington, D.C.:

December 22, 2016.

Border Security: DHS Surveillance Technology, Unmanned Aerial

Systems and Other Assets. GAO-16-671T. Washington, D.C.: May 24,

2016.

2016 Annual Report: Additional Opportunities to Reduce Fragmentation,

Overlap, and Duplication and Achieve Other Financial Benefits. GAO-16-

375SP. Washington, D.C.: April 13, 2016.

Homeland Security Acquisitions: DHS Has Strengthened Management,

but Execution and Affordability Concerns Endure. GAO-16-338SP.

Washington, D.C.: March 31, 2016.

Related GAO Products

Southwest Border Security: Additional Actions Needed to Assess

Resource Deployment and Progress. GAO-16-465T. Washington, D.C.:

March 1, 2016.

Border Security: Progress and Challenges in DHS’s Efforts to Implement

and Assess Infrastructure and Technology. GAO-15-595T. Washington,

D.C.: May 13, 2015.

Homeland Security Acquisitions: Addressing Gaps in Oversight and

Information is Key to Improving Program Outcomes. GAO-15-541T.

Washington, D.C.: April 22, 2015.

Homeland Security Acquisitions: Major Program Assessments Reveal

Actions Needed to Improve Accountability. GAO-15-171SP. Washington,

D.C.: April 22, 2015.

2015 Annual Report: Additional Opportunities to Reduce Fragmentation,

Overlap, and Duplication and Achieve Other Financial Benefits. GAO-15-

404SP. Washington, D.C.: April 14, 2015.

Arizona Border Surveillance Technology Plan: Additional Actions Needed

to Strengthen Management and Assess Effectiveness. GAO-14-411T.

Washington, D.C.: March 12, 2014.

Arizona Border Surveillance Technology Plan: Additional Actions Needed

to Strengthen Management and Assess Effectiveness. GAO-14-368.

Washington, D.C.: March 3, 2014.

Border Security: Progress and Challenges in DHS Implementation and

Assessment Efforts. GAO-13-653T. Washington, D.C.: June 27, 2013.

Border Security: DHS’s Progress and Challenges in Securing U.S.

Borders. GAO-13-414T. Washington, D.C.: March 14, 2013.

Border Patrol: Key Elements of New Strategic Plan Not Yet in Place to

Inform Border Security Status and Resource Needs. GAO-13-25.

Washington, D.C.: December 10, 2012.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection’s Border Security Fencing,

Infrastructure and Technology Fiscal Year 2011 Expenditure Plan. GAO-

12-106R. Washington, D.C.: November 17, 2011.

Page 18 GAO-18-397T Border Security

Related GAO Products

Arizona Border Surveillance Technology: More Information on Plans and

Costs Is Needed before Proceeding. GAO-12-22. Washington, D.C.:

November 4, 2011.

Homeland Security: DHS Could Strengthen Acquisitions and

Development of New Technologies. GAO-11-829T. Washington, D.C.:

July 15, 2011.

Border Security: DHS Progress and Challenges in Securing the U.S.

Southwest and Northern Borders. GAO-11-508T. Washington, D.C.:

March 30, 2011.

Border Security Preliminary Observations on the Status of Key Southwest

Border Technology Programs. GAO-11-448T. Washington, D.C.: March

15, 2011.

Secure Border Initiative: DHS Needs to Strengthen Management and

Oversight of Its Prime Contractor. GAO-11-6. Washington, D.C.: October

18, 2010.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection’s Border Security Fencing,

Infrastructure and Technology Fiscal Year 2010 Expenditure Plan. GAO-

10-877R. Washington, D.C.: July 30, 2010.

Department of Homeland Security: Assessments of Selected Complex

Acquisitions, GAO-10-588SP. Washington, D.C.: June 30, 2010.

Secure Border Initiative: DHS Needs to Reconsider Its Proposed

Investment in Key Technology Program. GAO-10-340. Washington, D.C.:

May, 5, 2010.

Secure Border Initiative: DHS Has Faced Challenges Deploying

Technology and Fencing Along the Southwest Border, GAO-10-651T.

Washington, D.C.: May 4, 2010.

Secure Border Initiative: Testing and Problem Resolution Challenges Put

Delivery of Technology Program at Risk. GAO-10-511T. Washington,

D.C.: March 18, 2010.

Secure Border Initiative: DHS Needs to Address Testing and

Performance Limitations That Place Key Technology Program at Risk.

GAO-10-158. Washington, D.C.: January 29, 2010.

Page 19 GAO-18-397T Border Security

Related GAO Products

Secure Border Initiative: Technology Deployment Delays Persist and the

Impact of Border Fencing Has Not Been Assessed. GAO-09-1013T.

Washington, D.C.: September 17, 2009.

Secure Border Initiative: Technology Deployment Delays Persist and the

Impact of Border Fencing Has Not Been Assessed. GAO-09-896.

Washington, D.C.: September 9, 2009.

Border Patrol: Checkpoints Contribute to Border Patrol’s Mission, but

More Consistent Data Collection and Performance Measurement Could

Improve Effectiveness. GAO-09-824. Washington, D.C.: August 31, 2009.

Customs and Border Protection’s Secure Border Initiative Fiscal Year

2009 Expenditure Plan. GAO-09-274R. Washington, D.C.: April 30, 2009.

Secure Border Initiative Fence Construction Costs. GAO-09-244R.

Washington, D.C.: January 29, 2009.

Page 20 GAO-18-397T Border Security

(102613)

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the

United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety

without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain

copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be

necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

GAO’sMission

The Government Accountability Office, the audit, evaluation, and investigative

arm of Congress, exists to support Congress in meeting its constitutional

responsibilities and to help improve the performance and accountability of the

federal government for the American people. GAO examines the use of public

funds; evaluates federal programs and policies; and provides analyses,

recommendations, and other assistance to help Congress make informed

oversight, policy, and funding decisions. GAO’s commitment to good government

is reflected in its core values of accountability, integrity, and reliability.

ObtainingCopiesofGAOReportsandTestimony

The fastest and easiest way to obtain copies of GAO documents at no cost is

through GAO’s website (https://www.gao.gov). Each weekday afternoon, GAO

posts on its website newly released reports, testimony, and correspondence. To

have GAO e-mail you a list of newly posted products, go to https://www.gao.gov

and select “E-mail Updates.”

OrderbyPhone

The price of each GAO publication reflects GAO’s actual cost of production and

distribution and depends on the number of pages in the publication and whether

the publication is printed in color or black and white. Pricing and ordering

information is posted on GAO’s website, https://www.gao.gov/ordering.htm.

Place orders by calling (202) 512-6000, toll free (866) 801-7077, or

TDD (202) 512-2537.

Orders may be paid for using American Express, Discover Card, MasterCard,

Visa, check, or money order. Call for additional information.

ConnectwithGAO

Connect with GAO on Facebook, Flickr, Twitter, and YouTube.

Subscribe to our RSS Feeds or E-mail Updates. Listen to our Podcasts.

Visit GAO on the web at https://www.gao.gov.

ToReportFraud,Waste,andAbuseinFederal

Programs

Contact:

Website: https://www.gao.gov/fraudnet/fraudnet.htm

E-mail: [email protected]

Automated answering system: (800) 424-5454 or (202) 512-7470

CongressionalRelations

Orice Williams Brown, Managing Director, W[email protected], (202) 512-4400,

U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7125,

Washington, DC 20548

PublicAffairs

Chuck Young, Managing Director, [email protected], (202) 512-4800

U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7149

Washington, DC 20548

StrategicPlanningandExternalLiaison

James-Christian Blockwood, Managing Director, [email protected], (202) 512-4707

U.S. Government Accountability Office, 441 G Street NW, Room 7814,

Washington, DC 20548

PleasePrintonRecycledPaper.