h

.Long Covid Impact on Adult Americans:

Early Indicators Estimating Prevalence and Cost

A Solve Long Covid Initiative White Paper

April 5, 2022

Long Covid Impact on Americans:

Early Indicators Estimating Prevalence and Cost

solvelongcovid.org 2

CONTENTS

Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................................3

Background ..............................................................................................................................................................4

What is Long Covid / PASC? ..................................................................................................................................5

About Solve Long Covid Initiative ..........................................................................................................................7

Summary of Key Findings ......................................................................................................................................7

Methodology ..........................................................................................................................................................14

Model #1: Reported Case Model .........................................................................................................................14

Model #2: Seroprevalence Model ........................................................................................................................15

Updating to the Omicron model ...........................................................................................................................16

Economic Impact ..................................................................................................................................................17

Impact of Long Covid on the Labor Force ............................................................................................................ 17

Insights ...................................................................................................................................................................18

State Employment Metrics and Burdens .............................................................................................................. 18

Analysis ..................................................................................................................................................................21

Long Covid: A Tragic Opportunity .........................................................................................................................21

A Ragged Map .....................................................................................................................................................22

Put Work-First Strategies First .............................................................................................................................23

A Carrot & A Stick ................................................................................................................................................. 24

Disability Benets ................................................................................................................................................. 25

Wages Are Values ................................................................................................................................................25

If Forecasts Matter… ............................................................................................................................................26

Conclusions ...........................................................................................................................................................27

Acknowledgments .................................................................................................................................................28

Authors ................................................................................................................................................................. 28

References and Citations .....................................................................................................................................29

Endnotes ................................................................................................................................................................30

Long Covid Impact on Americans:

Early Indicators Estimating Prevalence and Cost

solvelongcovid.org 3

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

While most patients recover from COVID-19, as many as half experience lingering symptoms six or more

months after their initial infection.

1

Long Covid is the patient-preferred term used to describe this experience

of post-infection illness. Long Covid includes a broad range of symptoms that can be disabling, prevent the

patient’s recovery to pre-infection health, and thwart the patient’s return to the workforce.

Using mathematical models, publicly available data, patient-led research, and the published natural histo-

ries of other post-infection illnesses, specically myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/

CFS), Solve M.E. estimates the prevalence and cost of Long Covid on adult Americans, presented here. Most

importantly, these estimates differentiate between persons with milder symptoms and those experiencing dis-

ability or inability to work. While noting limitations of population and serology data, including under-reporting

and gender bias, these mathematical models and analyses were developed with a specic emphasis on the

impacts of this mass disabling event on American labor markets and labor shortages. Among the key ndings,

our models estimate:

The signicant numbers of those impacted by Disabling Long Covid (DLC) highlight the need for changes

to the structure of US disability benet programs as demand exponentially increases. Particularly, there is a

growing need for a scaled approach that reects a spectrum of disability to replace the current “one-size-ts-

all” approach. Additionally, employers will need to make signicant, sustained efforts to accommodate their

workers with post-infection illness.

While the overwhelming scale of COVID-19 and its estimated impacts on the labor force are the focus of

this analysis, it is important to note that prior to the current pandemic, there was and remains an existing

group of people who experience the long-term impacts post-infection diseases. These conditions include ME/

Long Covid Impact on Americans:

Early Indicators Estimating Prevalence and Cost

solvelongcovid.org 4

CFS, which was already costing the US economy up to $51 billion annually

2

and postural orthostatic tachycardia

syndrome (POTS), which costs 51% of patients over $10,000 or more,

3

prior to the exponential growth caused

by Long Covid. These should serve as a sobering reminder and a call to action to urgently address this looming

public health crisis.

BACKGROUND

Post-infection illness is not new. It is a documented, yet still misunderstood medical and research challenge. Two

years ago, the Solve ME/CFS Initiative (Solve M.E.) estimated the potential impact and cost of the inevitable

post-infection chronic illnesses expected to follow just behind the COVID-19 pandemic. Drawing from the col-

lected clinical and research knowledge of ME/CFS, Solve M.E. suggested that 3.5 million Americans may never

return to health, resulting in $48 billion in economic cost.

4

Other Post-infection illnesses that exhibit many of the

same symptoms as Long Covid include; myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), postural

orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) and other forms of dysautonomia, and mast cell activation syndrome

(MCAS). Several studies have found biological and clinical similarities between ME/CFS,

5

6

POTS,

7

8

and Long

Covid. The Government Accountability ofce also recently concluded that between 7.7–23 million Americans have

Long Covid.

9

“The ME/CFS research community is an untapped scientic resource that will be vital

to existing COVID-19 scientic, diagnostic, and treatment efforts.”

– “America’s Looming Health Crisis: COVID Patients Who Never Recover,”

Solve M.E. Whitepaper, April 21, 2020

To create these models, Solve M.E. applied the extensive knowledge base of ME/CFS in conjunction with mathe-

matical modeling, threatcasting, and new information published over the past two years, including information on

other post-infection illnesses. Like other post-infection illnesses, Long COVID is a complex, multi-system illness

that increases medical needs. Patients with these illnesses require additional services, testing, visits, and special-

ists. The complexity of these illnesses is a contributing factor to increased healthcare expenses and costs for this

patient population.

10

It is critical to acknowledge the partnership, research, and expertise of the Long Covid patient-led organizations

and recognize these predictive models would not exist without their contributions. The majority of these insights

and data were published by the Long Covid patients themselves. Additionally, it’s important to note the limitations

of these mathematical models, especially when utilizing data that is known to potentially undercount cases and

disproportionately exclude women and under-served communities (see Methodology pg 14).

The information presented in this publication represents early indications of prevalence and nancial burden of

“Long Covid,” the patient-preferred term, alternatively labeled Post-Acute Sequelae of COVID-19 or (PASC) by

some government and research bodies. Long Covid refers to individuals who experience new or worsening symp-

Long Covid Impact on Americans:

Early Indicators Estimating Prevalence and Cost

solvelongcovid.org 5

toms following a conrmed or suspected infection with SARS-Cov-2. PASC is an umbrella term, including those

with Long Covid, in addition to other post-infection experiences, such as tissue damage or post-ICU syndrome.

These terms embody the collection of post-infection symptoms, experiences, and challenges beyond the medi-

cal condition. What this paper hopes to capture are the extensive life-altering ramications for adult Americans

11

struggling with Long Covid, both as a consequence of nancial hardship, but also on communities collectively as

reected in labor markets and workforce.

What is Long Covid / PASC?

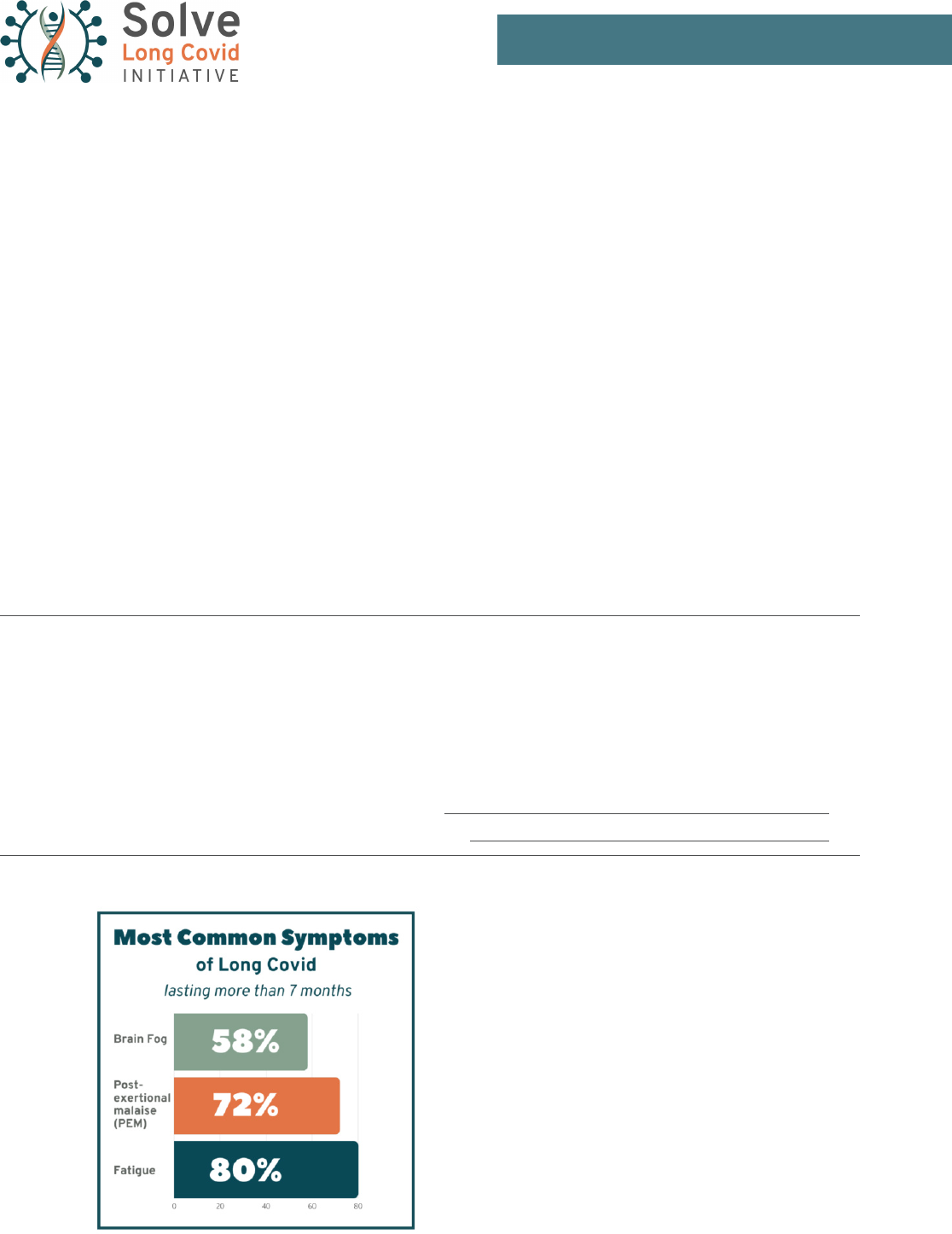

Long Covid / PASC describes a collection of lingering symptoms devastating the lives of many COVID-19 sur-

vivors. The most frequent prolonged symptoms—persistent fatigue, brain fog, and depleted energy after even a

minimal effort—have a profound impact on everyday functioning. Penn State College of Medicine researchers

found that over half of COVID-19 patients experience lingering symptoms six or more months after their initial

infection.

12

Our models reect that Long Covid affects an estimated 10-30% of people infected with SARS-CoV-2,

including those who were asymptomatic.

13

14

Researchers anticipate that millions of patients could have this dis-

ease for their lifetime.

15

“ The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) calls such cases ‘post-COVID condi-

tions,’ an umbrella term that refers to a range of ‘new, returning, or ongoing health problems’

experienced by people four or more weeks after initial coronavirus infection. Post-COVID

conditions also go by several other names, including long COVID, Long COVID, chronic

COVID, and post-acute COVID-19.”

—Yale Medicine. (2021, August 6). Long COVID (Post-Acute sequelae of SARS COV-2 infection, PASC).

Yale Medicine. Retrieved March 18, 2022, from https://www.yalemedicine.org/conditions/long-covid-

post-acute-sequelae-of-sars-cov-2-infection-pasc

Figure 1. Most Common Symptoms of Long Covid.

Characterizing Long Covid in an international cohort: 7 months

of symptoms and their impact. Davis et al, Lancet Jul. 2021

Long Covid Impact on Americans:

Early Indicators Estimating Prevalence and Cost

solvelongcovid.org 6

“ Researchers have identied several possible causes of Long Covid and have suggested that

causes may vary from person to person (see g. 2). For some, COVID-19 may cause the body

to produce an antibody that mimics SARS-CoV-2 and triggers an autoimmune response in

which the immune system attacks its own antibodies. For others, SARS-CoV-2 virus may

persist in the body and cause symptoms. Another possible cause is organ damage from

COVID-19. Research also suggests that microclots may form in blood vessels, blocking blood

ow and causing tissue damage. And COVID-19 may disrupt the immune system and reacti-

vate other previously contracted viruses, such as Epstein-Barr.”

—Science, Technology, Assessment, and Analytics, Science & Tech Spotlight: Long COVID (2022).

US Government Accountability Ofce. Retrieved from https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-22-105666.pdf

Figure 2. Some possible causes of Long Covid as suggested by researchers.

Science & Tech Spotlight: Long Covid (2022). US Government Accountability Ofce.

Long Covid (LC) in this paper is dened as a patient's experience of lingering or new symptoms following a

suspected or conrmed case of COVID-19. These symptoms may or may not be causing work loss, disability, or

disruption to daily life. Disabling Long Covid (DLC) in this paper is dened as a patient’s experience of disabling or

disruptive symptoms following a suspected or conrmed case of COVID-19. Those experiencing DLC are unable

to fully function at their pre-infection level and the experience of lingering or new symptoms results in disability

or reduced ability to work. Individuals experiencing DLC are assumed to be unable to work full-time or unable to

work at their pre-illness working level.

Long Covid Impact on Americans:

Early Indicators Estimating Prevalence and Cost

solvelongcovid.org 7

About Solve Long Covid Initiative

Based on more than 30 years of research and advocacy experience advancing the understanding of post-in-

fection diseases, the Solve Long Covid Initiative takes a strategic approach to integrating pre-pandemic and

post-pandemic knowledge and community insights. Our work in the post-infection disease space has allowed

us to create connections and build partnerships with researchers, clinicians, patients, government, and industry

leaders. The Solve Long Covid Initiative represents a collection of new and expanded Solve M.E. programs in

research, advocacy, and education that will improve outcomes for the millions suffering from poorly understood,

chronic diseases.

SUMMARY OF KEY FINDINGS

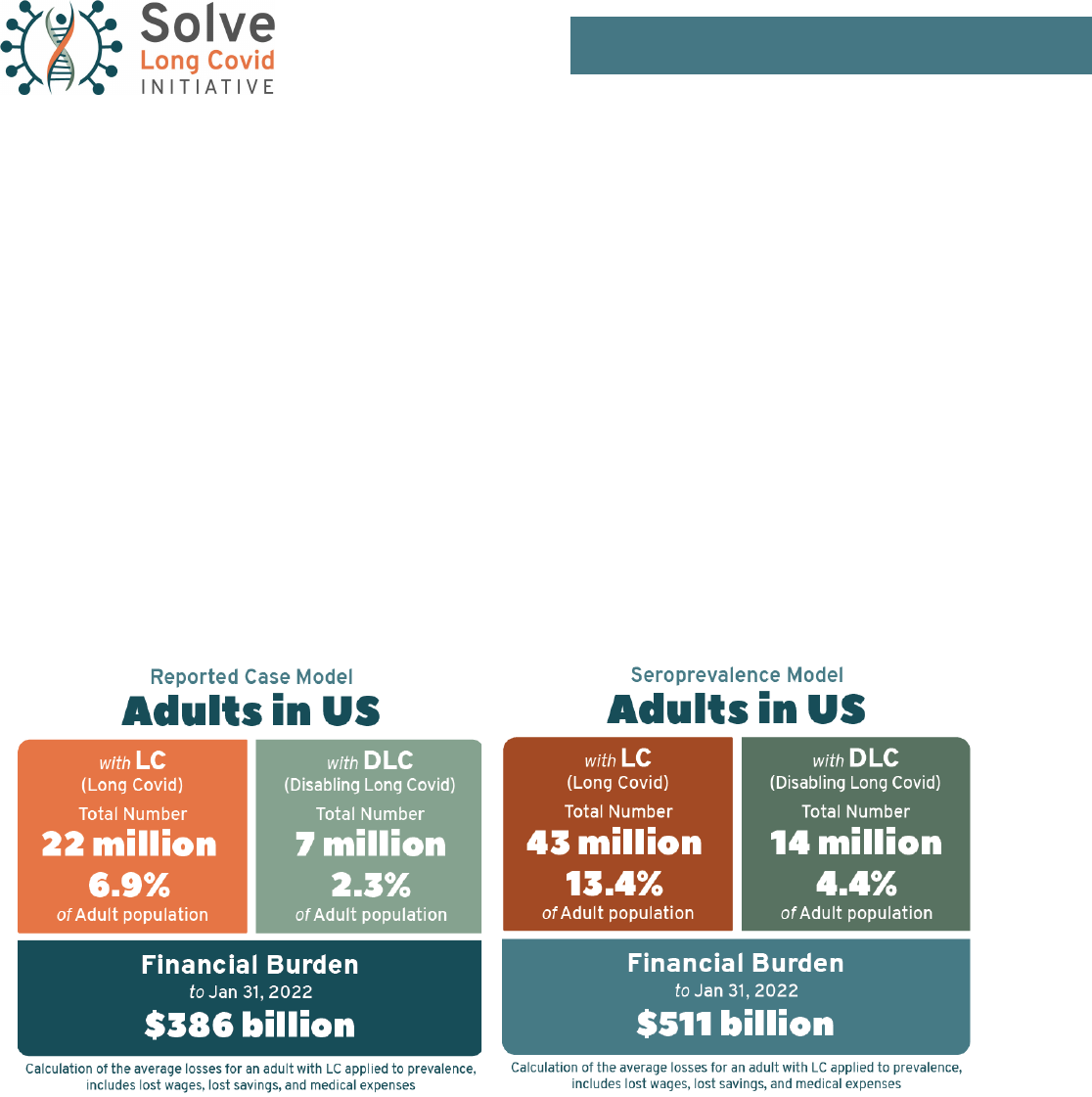

Long Covid is a pervasive economic and healthcare concern following the spread of COVID-19 that affects every

state in the nation. The Solve Long Covid Initiative models estimate that through January 31, 2022, the COVID-19

pandemic has potentially caused, at minimum, 22 million cases of Long Covid, with a higher estimate model

suggesting more than 43 million cases. This caseload includes 7 to 13% of the total population of the United

States. Of these cases, 7 to 14 million (2–4% of the total U.S. population) are expected to result in long-

term disability—placing individuals at risk of lifelong complex health problems and economic ruin from health-

care costs, unemployment, denied benets, eviction, and homelessness.

The states carrying the highest total caseload of Long Covid cases are, unsurprisingly, those with the largest

populations:

Table 1: Reported Case Model. Top 5 states for total Long Covid prevalence.

Ranking State LC Cases DLC Cases

1 California 2.47 million 817,000

2 Texas 1.84 million 611,000

3 Florida 1.64 million 543,000

4 New York 1.40 million 464,000

5 Illinois 860,000 285,000

Table 2: Seroprevalence Model. Top 5 states for total Long Covid prevalence.

Ranking State LC Cases DLC Cases

1 California 4.76 million 1.58 million

2 Texas 4.37 million 1.45 million

3 New York 2.83 million 936,000

4 Florida 2.49 million 828,000

5 Illinois 2.06 million 684,000

Long Covid Impact on Americans:

Early Indicators Estimating Prevalence and Cost

solvelongcovid.org 8

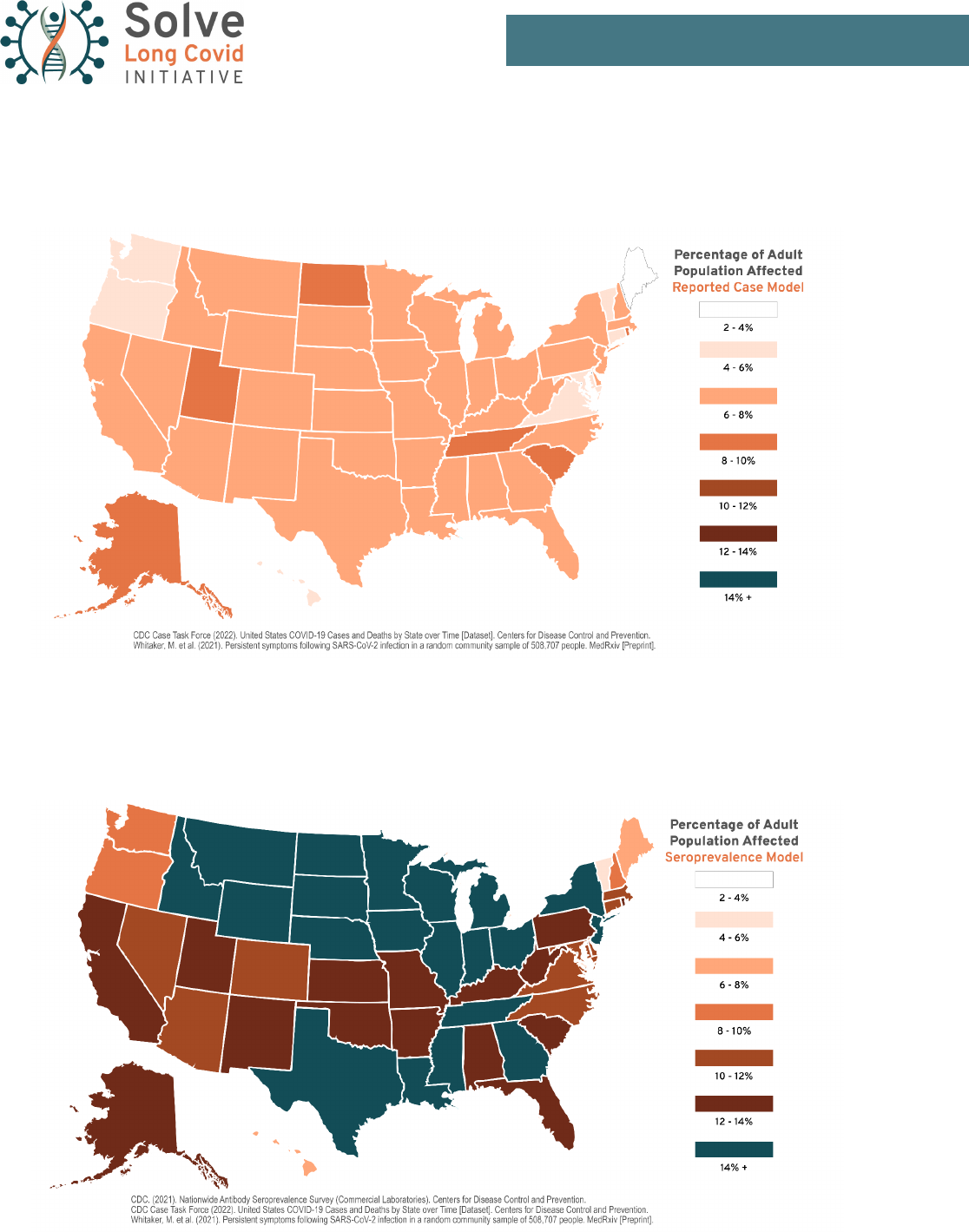

However, a more important statistic may be the proportion of a state’s population that is aficted by post-COVID

symptoms; an area of concern due to many inequalities. People in states with high rates of COVID infection were

disproportionately affected by poverty, chronic illness, and healthcare inequality prior to the pandemic. Pandemic

response, testing and vaccination rates also impacted Long Covid outcomes. A high disease burden inicted by

elevated rates of post-COVID illness threatens to further entrench these inequalities:

Table 3: States with the highest percentage of population affected by Long Covid.

Ranking

Reported Case Model Seroprevalence Model

State % LC % DLC State % LC % DLC

1 Rhode Island 9.5% 3.1% North Dakota 16.7% 5.6%

2 North Dakota 8.8% 2.9% Wisconsin 16.6% 5.5%

3 Utah 8.6% 2.9% Iowa 16.2% 5.4%

4 Alaska 8.4% 2.8% Illinois 16.1% 5.3%

5 Tennessee 8.3% 2.8% Wyoming 15.9% 5.3%

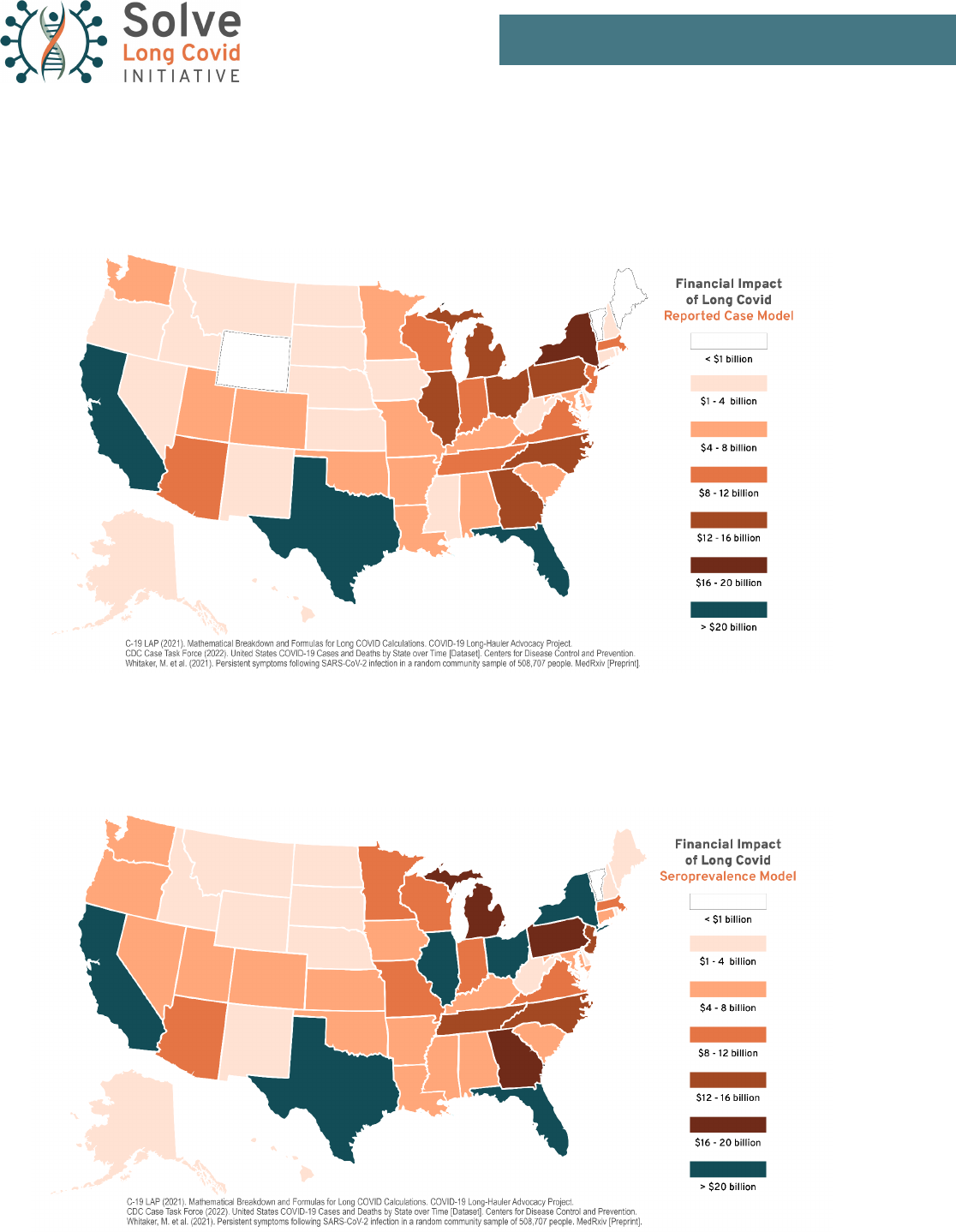

The widespread disability and economic loss caused by Long Covid has inicted a signicant cost on the Unit-

ed States and its citizens. When the estimated cost of healthcare expenses, lost savings, and lost income are

combined for the full estimated long-hauler population, it is estimated that disability caused by Long Covid has

cost over $386 billion since the pandemic began until January 31, 2022. However, this statistic only captures

the nancial burden currently experienced by individuals—it does not begin to assess the long-term and indirect

effects of this disease on businesses, communities, and federal, state, and local budgets.

The disability caused by Long Covid greatly expands the pool of people experiencing long-term complex disability

from illnesses such as ME/CFS, POTS and other forms of dysautonomia, and other post-infection illnesses. Prior

to the pandemic, it is estimated that 2.5 million Americans live with ME/CFS, creating a $51 billion annual cost.

16

The number of people experiencing disability from Disabling Long Covid (7–14 million) could be 3–5

times the total number of pre-pandemic ME/CFS patients—with over 7 times the cost.

Long Covid Impact on Americans:

Early Indicators Estimating Prevalence and Cost

solvelongcovid.org 9

Map 1: Reported Case Model. Estimated total number of Long Covid (LC) cases in the United States as a

percentage of each state’s total population

Map 2: Seroprevalence Case Model. Estimated total number of Long Covid (LC) cases in the United States as a

percentage of each state’s total population

Long Covid Impact on Americans:

Early Indicators Estimating Prevalence and Cost

solvelongcovid.org 10

Map 3: Financial Burden of Long Covid (Reported Case Model). Estimated cost in lost wages, lost savings,

and medical expenses to Disabled Long Covid (DLC) patients in the United States to January 31, 2022, broken

down by state. This map uses the DLC estimates from the Reported Case Model.

Map 4: Financial Burden of Long Covid (Seroprevalence Model). Estimated cost in lost wages, lost savings,

and medical expenses to Disabled Long Covid (DLC) patients in the United States to January 31 2022, broken

down by state. This map uses the DLC estimates from the Seroprevalence Model.

Long Covid Impact on Americans:

Early Indicators Estimating Prevalence and Cost

solvelongcovid.org 11

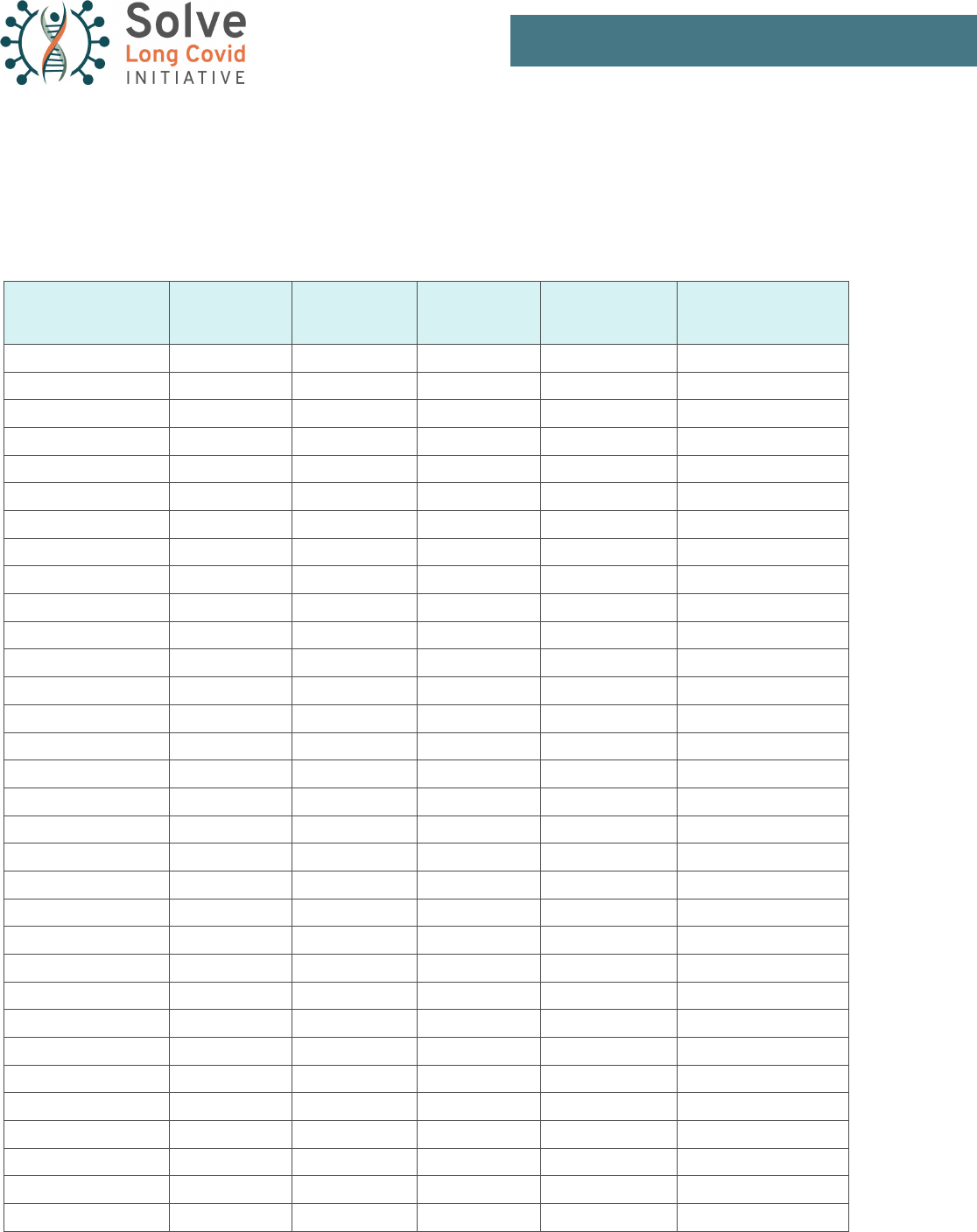

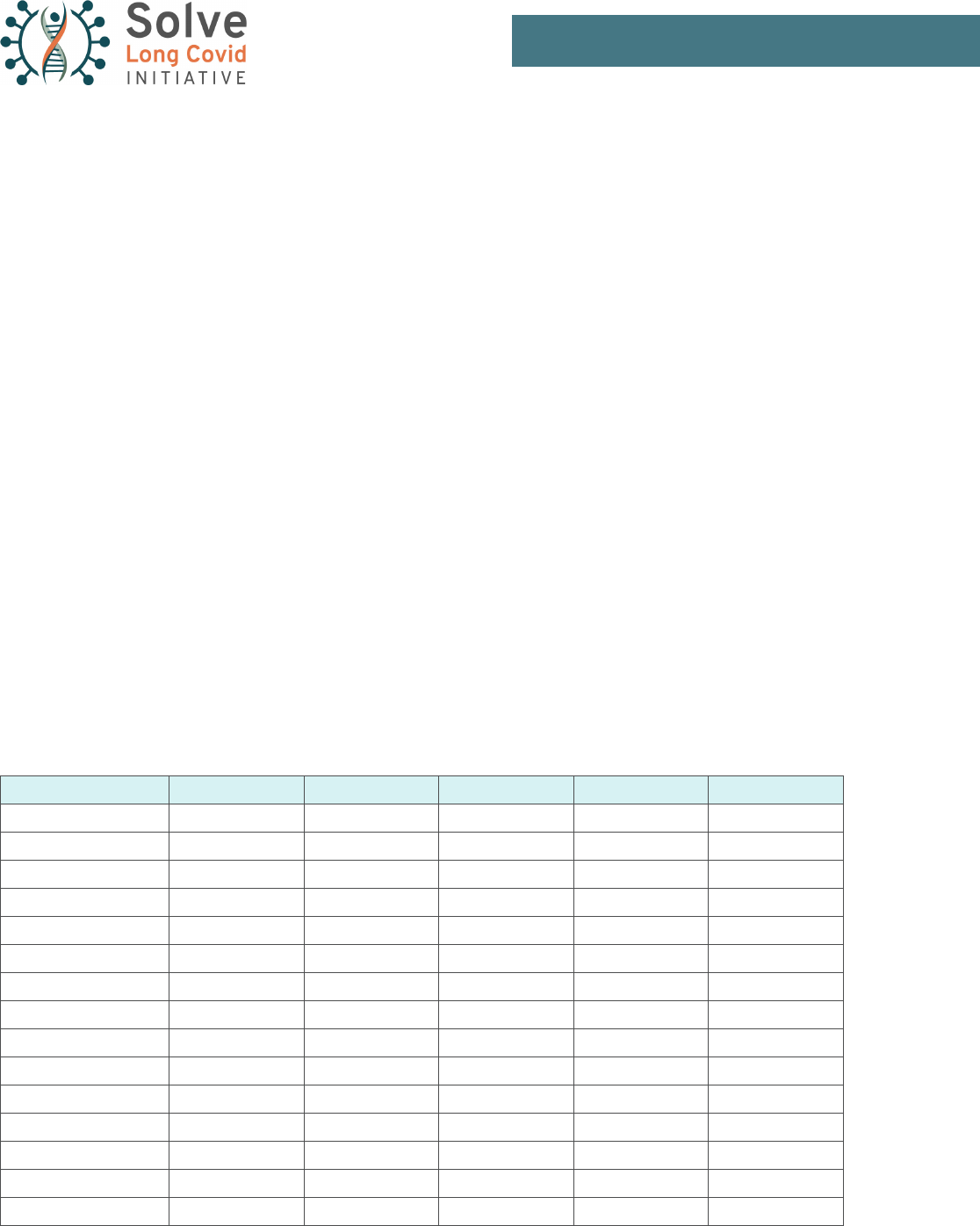

Table 4: Reported Case Model. Estimated number of Long Covid (LC) cases in the United States, broken down

by state. Estimates for this model are based on the number of surviving COVID cases reported by the CDC. The

number of LC cases is calculated at 30% of unvaccinated cases, with LC severe enough to cause disability being

calculated as 10% of unvaccinated cases. A modied calculation is used for vaccinated breakthrough cases.

State

Number of LC

Cases

Number of

Disabling LC

Cases

LC as Percent

of State

Population

DLC as Percent

of State

Population

Cumulative Cost to

Jan 31, 2022

Alabama 363,000 121,000 7.5% 2.5% $6.5 billion

Alaska 62,000 20,500 8.4% 2.8% $1.1 billion

Arizona 554,000 184,000 8% 2.7% $9.8 billion

Arkansas 230,000 76,500 7.7% 2.6% $4.1 billion

California 2,470,000 817,000 6.3% 2.1% $43.2 billion

Colorado 370,000 123,000 6.7% 2.2% $6.7 billion

Connecticut 205,000 68,000 5.7% 1.9% $3.7 billion

Delaware 73,000 24,000 7.7% 2.6% $1.3 billion

District of Columbia 38,000 13,000 5.6% 1.8% $700 million

Florida 1,640,000 544,000 8% 2.6% $29.8 billion

Georgia 702,000 233,000 6.8% 2.3% $12.6 billion

Hawaii 62,000 20,500 4.4% 1.4% $1.1 billion

Idaho 113,000 37,500 6.7% 2.2% $2 billion

Illinois 859,000 285,000 6.7% 2.2% $15.5 billion

Indiana 481,000 160,000 7.3% 2.4% $8.7 billion

Iowa 214,000 71,000 6.8% 2.3% $3.9 billion

Kansas 216,000 72,000 7.4% 2.3% $3.9 billion

Kentucky 344,000 114,000 7.8% 2.6% $6.1 billion

Louisiana 330,000 110,000 7.1% 2.4% $6 billion

Maine 52,000 17,000 3.9% 1.3% $940 million

Maryland 281,000 93,000 4.7% 1.6% $5.2 billion

Massachusetts 472,000 156,000 6.9% 2.3% $8.6 billion

Michigan 669,000 222,000 6.7% 2.2% $12 billion

Minnesota 391,000 130,000 7.1% 2.4% $7 billion

Mississippi 216,000 72,000 7.2% 2.4% $3.9 billion

Missouri 394,000 131,000 6.5% 2.2% $7.1 billion

Montana 72,000 24,000 6.9% 2.3% $1.3 billion

Nebraska 131,000 43,500 6.9% 2.3% $2.3 billion

Nevada 195,000 64,500 6.7% 2.2% $3.5 billion

New Hampshire 82,000 27,000 6.1% 2% $1.5 billion

New Jersey 619,000 205,000 7% 2.3% $11.3 billion

New Mexico 142,000 47,000 6.8% 2.3% $2.5 billion

Long Covid Impact on Americans:

Early Indicators Estimating Prevalence and Cost

solvelongcovid.org 12

State

Number of LC

Cases

Number of

Disabling LC

Cases

LC as Percent

of State

Population

DLC as Percent

of State

Population

Cumulative Cost to

Jan 31, 2022

New York 1,400,000 464,000 7.2% 2.4% $17.5 billion

North Carolina 716,000 238,000 7.1% 2.3% $12.6 billion

North Dakota 66,500 22,000 8.8% 2.9% $1.2 billion

Ohio 763,000 253,000 6.6% 2.2% $14 billion

Oklahoma 290,000 96,000 7.4% 2.5% $5.1 billion

Oregon 187,000 62,000 4.6% 1.5% $3.3 billion

Pennsylvania 783,000 260,000 6.1% 2% $14.2 billion

Rhode Island 100,000 33,000 9.5% 3.1% $1.8 billion

South Carolina 410,000 136,000 8.3% 2.7% $7.2 billion

South Dakota 67,000 22,000 7.8% 2.6% $1.2 billion

Tennessee 555,000 184,000 8.3% 2.8% $10 billion

Texas 1,840,000 611,000 6.6% 2.2% $33 billion

Utah 262,000 87,000 8.6% 2.9% $4.7 billion

Vermont 28,000 9,000 4.5% 1.5% $500 million

Virginia 457,000 151,000 5.4% 1.8% $8.2 billion

Washington 394,000 130,000 5.4% 1.8% $6.7 billion

West Virginia 132,000 44,000 7.2% 2.4% $2.3 billion

Wisconsin 449,000 149,000 7.8% 2.6% $8.1 billion

Wyoming 43,500 14,500 7.5% 2.5% $775 million

TOTAL & Average USA 22 million 7.3 million 6.9% 2.3% $386 billion

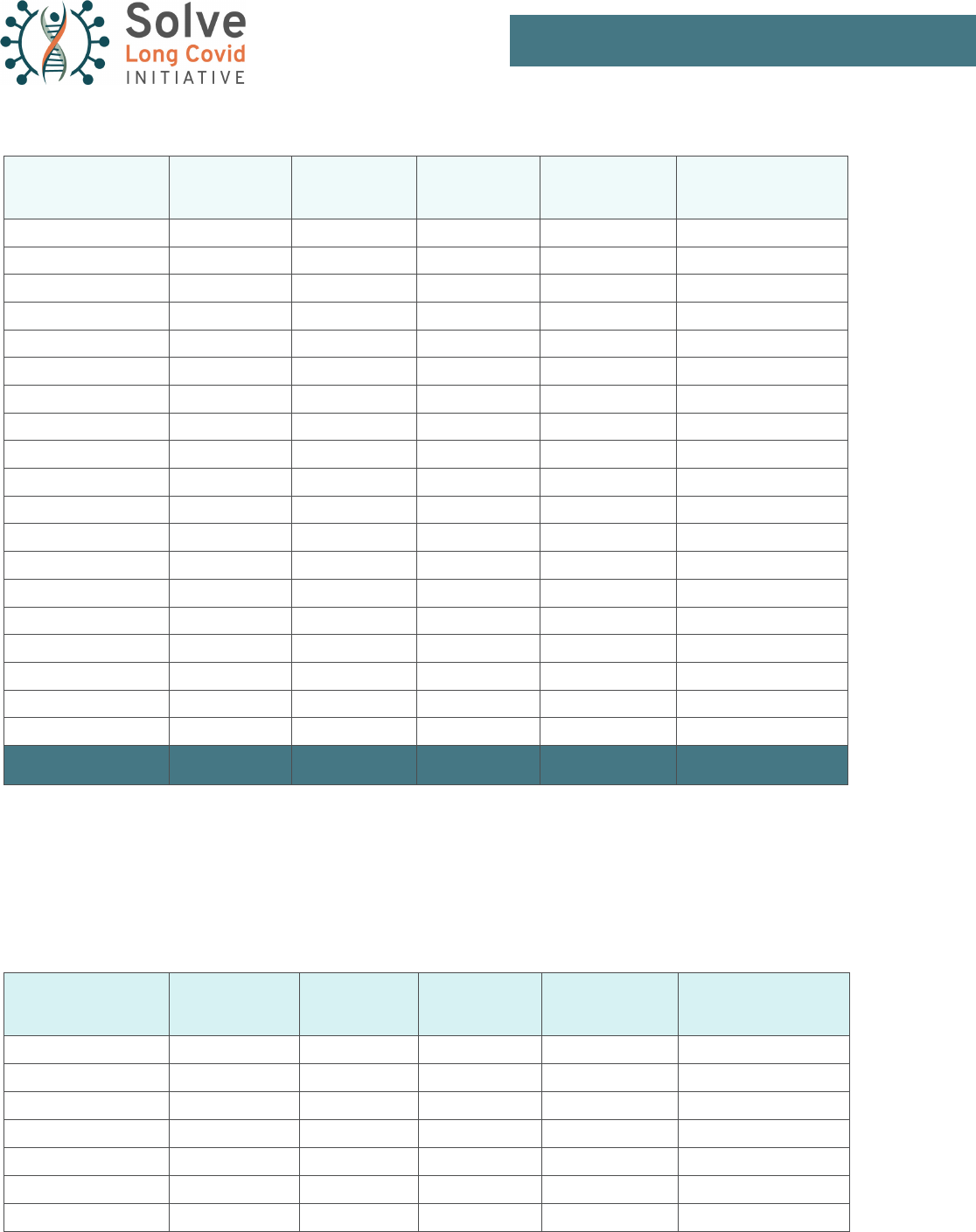

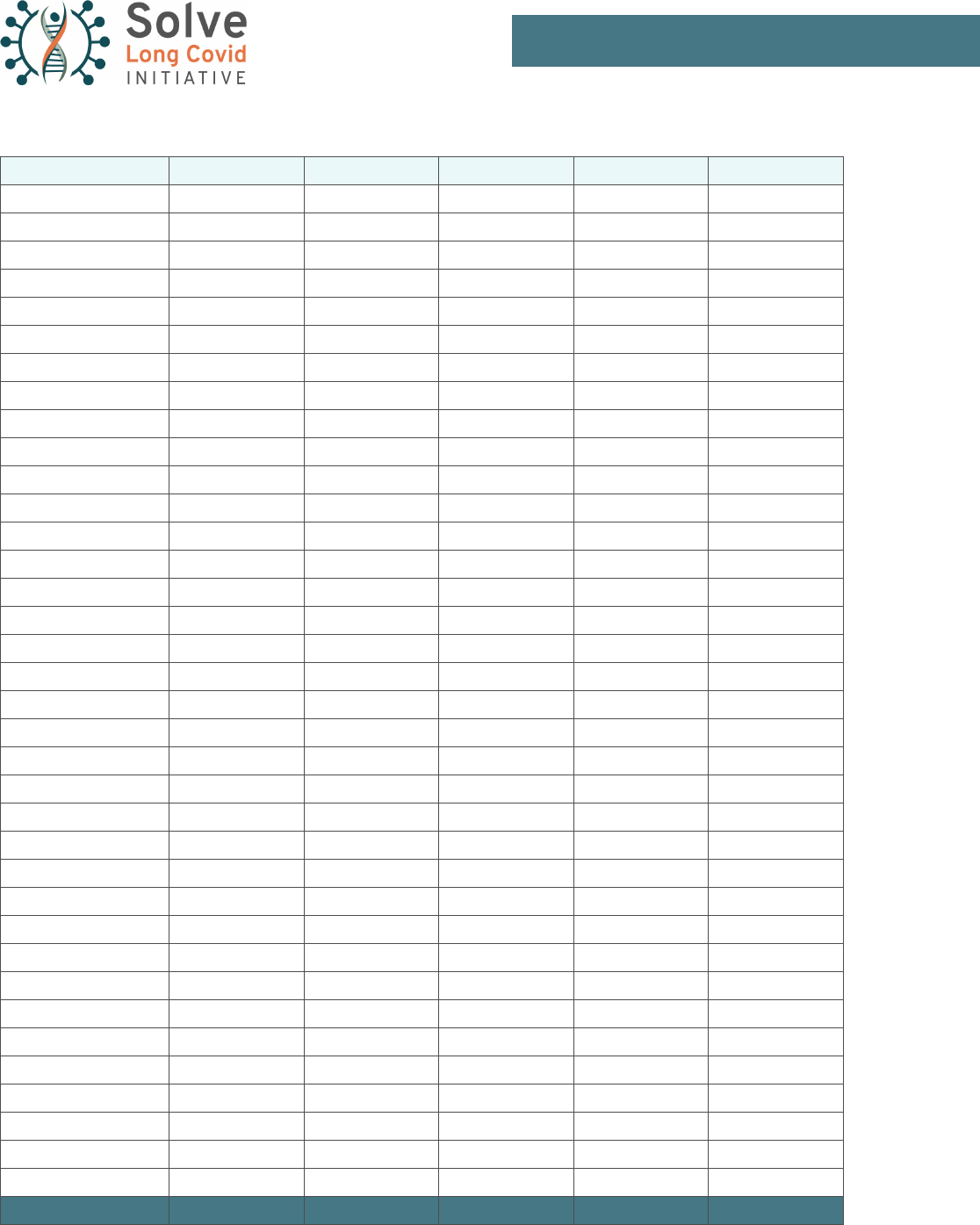

Table 5: Seroprevalence Model. Estimated number of Long Covid (LC) cases in the United States, broken down

by state. Estimates for this model are based on the average seroprevalence of the nucleocapsid antibody (indicat-

ing natural infection) in community surveys conducted in each state between 12/27/21 and 1/29/22. The number

of LC cases is calculated at 30% of unvaccinated cases, with LC severe enough to cause disability being calculat-

ed as 10% of unvaccinated cases. A modied calculation is used for vaccinated breakthrough cases.

State

Number of LC

Cases

Number of

Disabling LC

Cases

LC as Percent

of State

Population

DLC as Percent

of State

Population

Cumulative Cost to

Jan 31, 2022

Alabama 639,000 213,000 13.1% 4.4% $8.1 billion

Alaska 91,000 30,000 12.3% 4.1% $1.3 billion

Arizona 818,000 272,000 11.8% 3.9% $11.3 billion

Arkansas 396,000 132,000 13.3% 4.4% $5.1 billion

California 4,760,000 1,580,000 12.2% 4% $56.7 billion

Colorado 622,000 207,000 11.2% 3.7% $8.2 billion

Connecticut 409,000 135,000 11.4% 3.8% $4.9 billion

Long Covid Impact on Americans:

Early Indicators Estimating Prevalence and Cost

solvelongcovid.org 13

State

Number of LC

Cases

Number of

Disabling LC

Cases

LC as Percent

of State

Population

DLC as Percent

of State

Population

Cumulative Cost to

Jan 31, 2022

Delaware 109,000 36,000 11.5% 3.8% $1.5 billion

District of Columbia 86,500 29,000 12.6% 4.2% $990 million

Florida 2,490,000 828,000 12.1% 4% $34.8 billion

Georgia 1,520,000 503,000 14.7% 4.9% $17.4 billion

Hawaii 89,500 29,500 6.3% 2.1% $1.2 billion

Idaho 237,000 79,000 14.1% 4.7% $2.8 billion

Illinois 2,060,000 684,000 16.1% 5.3% $22.6 billion

Indiana 1,030,000 342,000 15.5% 5.2% $11.9 billion

Iowa 506,000 168,000 16.2% 5.4% $5.6 billion

Kansas 364,000 121,000 12.5% 4.2% $4.7 billion

Kentucky 579,000 192,000 13% 4.3% $7.5 billion

Louisiana 703,000 234,000 15.1% 5% $8.2 billion

Maine 90,000 30,000 6.8% 2.2% $1.2 billion

Maryland 679,000 225,000 11.3% 3.8% $7.5 billion

Massachusetts 735,000 243,000 10.8% 3.6% $10 billion

Michigan 1,500,000 499,000 15.1% 5% $17 billion

Minnesota 790,000 262,000 14.3% 4.7% $9.3 billion

Mississippi 462,000 154,000 15.5% 5.1% $5.3 billion

Missouri 779,000 259,000 12.8% 4.3% $9.4 billion

Montana

148,000 49,000 14.2% 4.7% $1.7 billion

Nebraska

292,000 97,000 15.3% 5.1% $3.3 billion

Nevada

350,000 116,000 12% 4% $4.4 billion

New Hampshire

131,000 43,000 9.7% 3.2% $1.7 billion

New Jersey

1,330,000 441,000 15% 5% $15.6 billion

New Mexico

253,000 83,000 12.1% 4% $3.2 billion

New York

2,830,000 936,000 14.4% 4.8% $26 billion

North Carolina

1,200,000 401,000 11.9% 3.9% $15.5 billion

North Dakota

125,000 42,000 16.7% 5.6% $1.5 billion

Ohio

1,840,000 612,000 15.8% 5.3% $20.3 billion

Oklahoma

532,840 177,000 13.6% 4.5% $6.6 billion

Oregon

340,000 113,000 8.3% 2.8% $4.2 billion

Pennsylvania

1,720,000 570,000 13.5% 4.5% $19.7 billion

Rhode Island

138,000 46,000 13.1% 4.3% $2 billion

South Carolina

666,000 222,000 13.4% 4.5% $8.7 billion

South Dakota

127,000 42,000 14.7% 4.9% $1.6 billion

Tennessee

1,000,000 333,000 15.1% 5% $12.5 billion

Texas

4,370,000 1,500,000 15.7% 5.2% $48 billion

Long Covid Impact on Americans:

Early Indicators Estimating Prevalence and Cost

solvelongcovid.org 14

State

Number of LC

Cases

Number of

Disabling LC

Cases

LC as Percent

of State

Population

DLC as Percent

of State

Population

Cumulative Cost to

Jan 31, 2022

Utah

389,000 130,000 12.7% 4.2% $5.4 billion

Vermont

32,000 11,000 5.2% 1.7% $524 million

Virginia

860,000 285,000 10.3% 3.4% $10.6 billion

Washington

668,000 222,000 9.2% 3% $8.3 billion

West Virginia

230,000 76,500 12.6% 4.2% $2.9 billion

Wisconsin

957,000 317,000 16.6% 5.5% $11.1 billion

Wyoming

92,000 31,000 15.9% 5.3% $1.1 billion

TOTAL & Average USA 43 million 14.3 million 13.4% 4.4% $511 billion

METHODOLOGY

Our group’s models of estimated Long Covid cases in the United States are derived from prior population-level

research on the prevalence of post-COVID symptoms combined with data on the number of COVID-19 cases in

each state collected through January 31, 2022. Our model estimates that of all people infected with COVID-19,

30% will develop at least one lingering symptom, and 10% will develop a disabling case of Long Covid (DLC)

severe enough to interfere with employment or activities of daily living. These rates are derived from Whitaker et

al (2021), a community sample of 500,000 people

17

that explores the prevalence of post-COVID symptoms in a

general, non-hospitalized population.

Although a consensus is emerging that Long Covid can develop in between 10 to 30% of COVID cases, determin-

ing how many people have had COVID-19 in the rst place is a much less certain question due to the persistent

undercounting of cases throughout the pandemic. To address this uncertainty, we developed two models:

1) A model using the reported COVID case numbers from each state to give a low estimate

2) A model using the CDC’s community seroprevalence survey to give a higher estimate that includes

unreported COVID cases

Model #1: Reported Case Model

This model uses the cumulative number of surviving COVID cases reported in each state until January

31, 2022, as reported by the CDC, to calculate the estimated number of Long Covid cases per state.

18

Us-

ing the rates from Whitaker et al (2021), we calculate that 30% of COVID cases in each state will develop

at least one long-term symptom, with one third of these cases (10% of the overall case numbers) devel-

oping a disabling case of Long Covid. Dividing each state’s estimated number of Long Covid cases by the

population gives an estimate of what percentage of each state’s population will be affected by long-term

post-COVID symptoms (See Table 4).

Long Covid Impact on Americans:

Early Indicators Estimating Prevalence and Cost

solvelongcovid.org 15

Of the two models, the Reported Case model provides the most up-to-date information on COVID case

numbers. This allows the model to reect recent changes in case data—like was observed with the rapid

spread of the Omicron variant. The main limitation of this model is its inability to account for unreported

cases of COVID. COVID cases have been under-reported throughout the pandemic,

19

and this is a wors-

ening problem during the Omicron surge due to strains on test availability, and the widespread use of at-

home Rapid Antigen Tests that are not included in ofcial case counts. The Reported Case Model should

therefore be used as a oor, or a low estimate, when trying to estimate the prevalence of Long Covid.

Model #2: Seroprevalence Model

Our group’s second model attempts to compensate for the Reported Case Model’s main limitation by

using a metric that is more inclusive of unreported COVID cases—the CDC’s Community Seroprevalence

Survey. The Seroprevalence Survey looks for the prevalence of the nucleocapsid antibody, which is a

marker of natural COVID infection as opposed to vaccine-induced immunity, within community samples

gathered in each state.

20

The average seroprevalence reported in each state is interpreted as the percent-

age of the population in that state with prior COVID-19 infection. The Long Covid prevalence rates are

then applied to this number of estimated COVID infections (See Table 5).

The Seroprevalence model should be used as a higher estimate of the prevalence of Long Covid, due to

its inclusion of unreported cases not included in ofcial case counts. However, we do so recognizing sev-

eral limitations that also contribute to its undercounting and inaccuracy. First, a signicant limitation of this

model is its reliance on averages of community sampling from which total case counts are extrapolated,

instead of being a true tallying of cases. This method of data collection makes the Seroprevalence model

more vulnerable to uncertainty and data artifacts than the reported case model. For example, it is possible

for estimated cases in states with high baseline infection rates to remain relatively static between months

if community sampling rounds return high-but-consistent seroprevalence rates. Secondly, using antibod-

ies to conrm past COVID infection is known to disproportionately exclude three groups; 1) women (who

are 4x less likely to retain antibodies than men),

21

22

2) mild cases (65% of mild cases serorevert in the

rst two months),

23

24

and 3) Long Covid cases (who have low or no antibodies).

25

The Seroprevalence model makes the assumption that all people with prior COVID infection possess

detectable COVID antibodies. However, this is not always the case—emerging research has found that

24–36% of people infected with COVID-19 lose antibodies in the months following infection (serorever-

sion),

26

or do not create detectable antibodies at all.

27

People who experience seroreversion may be at

higher risk of developing Long Covid—recent research indicates that low antibody and immune response

during acute COVID infection is correlated with a higher risk of persistent symptoms and Long Covid.

28

29

Although the seroprevalence model used in this paper does not take seroreversion into account, it is

important to acknowledge that the case counts predicted by this model—as high as they seem—still may

not capture some cases of Long Covid.

Long Covid Impact on Americans:

Early Indicators Estimating Prevalence and Cost

solvelongcovid.org 16

The model is also not sensitive to reinfections—a recent and emerging concern from the B.A. 1 and B.A. 2

Omicron variants.

30

However, despite these limitations, the Seroprevalence model returns a consistently

higher case count in proportion to the Reported Case model that can help ll in the gaps caused by un-

der-testing, under-reporting, and other limitations of the ofcial COVID case counts.

Updating to the Omicron model

Our rst Long Covid models were produced in November 2021—after mass vaccination campaigns but

prior to the emergence and rapid spread of the Omicron variant around the world. The Omicron surge

beginning in December 2021 required us to re-evaluate our Long Covid model due to signicant rates

of breakthrough infection among vaccinated individuals that had been relatively rare in previous surges.

Due to the protective effect of vaccines against severe illness and some protection against Long Covid,

the previous base rate of 30% Long Covid prevalence can no longer be assumed for the entire infected

population.

After the start of the Omicron surge in each state—December 25

th

, 2021 or earlier, depending on

state-level positivity and case data—the Long Covid model shifts from the earlier model assuming a 30%

prevalence of Long Covid for all COVID cases to a modied model that separates unvaccinated and

vaccinated breakthrough cases based on state-level vaccination rates. The Omicron model uses two

variables to account for uncertainty surrounding the level of protection that vaccination provides against

infection and long-term symptoms from Omicron:

1) The percentage of total Omicron cases occurring in vaccinated people. Data released by the

New York City Department of Health indicates that during New York City’s Omicron surge in early

December, unvaccinated individuals were 8 times more likely to test positive for COVID-19 than

vaccinated individuals.

31

Therefore, in this model, breakthrough cases accounted for 1 in 9—or

11% of total cases.

2) The reduction in risk against Long Covid for breakthrough infections, compared to unvaccinated

cases. An Israeli study found that vaccinated individuals with breakthrough cases were 54—68%

less likely to report four of the most common post COVID symptoms (fatigue, weakness, head-

ache, and muscle pain) than unvaccinated individuals.

32

For this model, we assumed that vac-

cination provides 66% protection against the development of any long-term COVID symptom—

giving a 10% risk of developing LC from a breakthrough infection compared to the 30% risk from

an unvaccinated infection. This risk prole mirrors the ndings of emerging cohort studies on the

prevalence of LC in vaccinated people with breakthrough infections.

33

The risk of disabling Long Covid from breakthrough infections is still unknown. For the purposes

of this model, we are assuming that vaccination provides strong protection (90%) against severe

long-term illness, giving vaccinated breakthrough cases a 1% chance of developing disabling

Long Covid Impact on Americans:

Early Indicators Estimating Prevalence and Cost

solvelongcovid.org 17

Long Covid, compared to the 10% risk posed for unvaccinated cases. Recognizing this assump-

tion represents a conservative estimate, time and further study will determine if vaccination

proves to be so effective against Omicron.

Economic Impact

The COVID Longhauler Advocacy Project (C-19 LAP) conducted a survey on the economic and labor

market impact of Disabling Long Covid.

34

Their model assumes a 10% prevalence rate of Long Covid

among COVID survivors, and focuses on people experiencing substantial disruption to their employment

and daily functioning from their illness. This 10% prevalence rate corroborates with the 10% of post-

COVID patients in the Whitaker study that described their symptoms as disabling.

The C-19 LAP’s models estimate the current costs of Long Covid from two sources—healthcare costs

and lost earnings. Their survey found that the average healthcare costs accumulated by people disabled

by Long Covid are $17,776 per person annually, and multiplying this gure by the number of disabled

long-haulers in a given state gives an estimate of the accumulated healthcare costs by state. The lost

earnings model looks at the 44% of the long-hauler sample that is unemployed and the 51% who are only

able to work part-time, and calculates the total amount of lost income based on the duration of lost work

capacity.

Our team created an interactive version

35

of these models that could be used to calculate state-level data.

The combination of healthcare costs and lost earnings gives a glimpse into the economic impact of Long

Covid on a state-by-state basis.

Impact of Long Covid on the Labor Force

To assess the impact of LC on the labor force, our team used statistics on state-level labor force participa-

tion released by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS).

36

The number of expected DLC cases in each state

were taken as a percentage of that state’s total labor force. This highlights the differential impact of DLC

among states with similar populations, but different infection rates and baseline levels of workforce partic-

ipation. This calculation also helps determine which states may experience the greatest economic impact

from COVID infection in working-age people.

Long Covid Impact on Americans:

Early Indicators Estimating Prevalence and Cost

solvelongcovid.org 18

INSIGHTS

State Employment Metrics and Burdens

This table is intended to provide a snapshot of state employment trends to put infection rates around the country

in perspective. As you might guess, under the national aggregates are real disparities. For example, in the rst

column of Table 6, we show state Labor Force Participation Rates (LFPR), the labor force as a percentage of the

non-institutionalized civilian population over sixteen. Although the national LFPR was 62.2% in January, 2022,

around the country rates ran from lows of 55% in Mississippi and West Virginia to the high 60% range in North

Dakota and Nebraska, on to 72% in Washington, DC. Among the nine Census Divisions the LFPR runs from a

low of 58% in the East South Central Division, to 64% in New England, and up to 66% in the West North Central.

The labor force includes both those with a job and those looking for work, and it’s important to policy makers as a

measure of worker engagement.

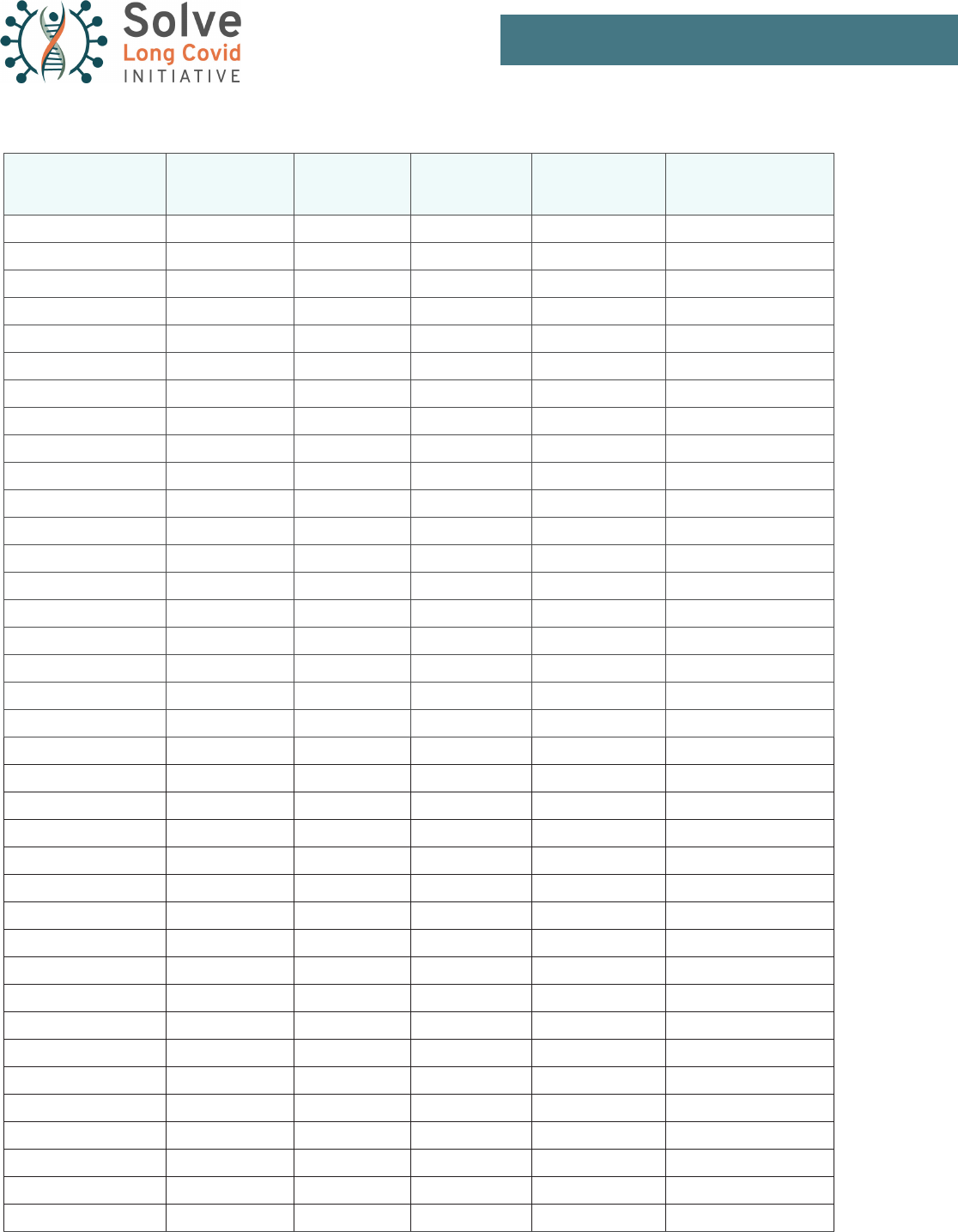

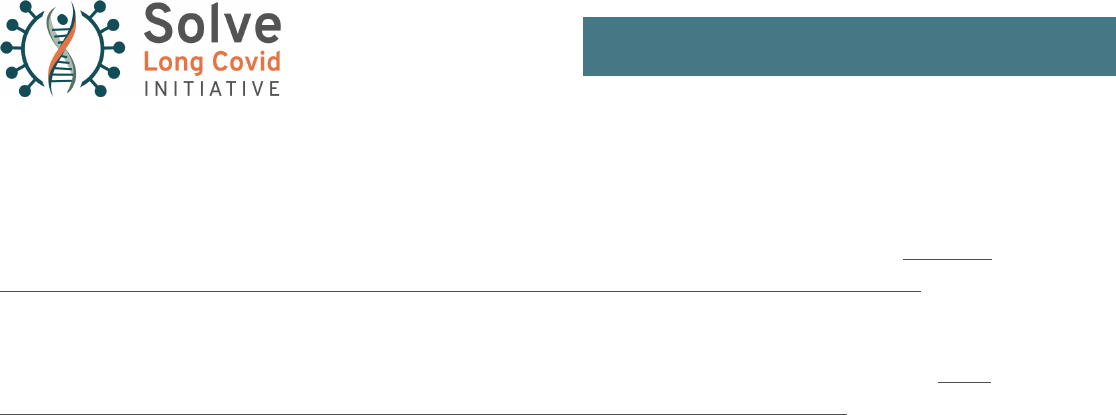

Table 6: State Employment Metrics and Burdens (Reported Cases). This matrix presents the estimated num-

ber of Disabling Long Covid (DLC) cases and costs shown in Table 4 in the context of selected labor-force metrics

for each state. The size of the labor force relative to the population is shown in column 1, and the job opening

rate, unlled positions as a share of those working, in column 2. Column 3 calculates the number of infections as

a percent of the labor force, and column 4, calculates the burden per worker by dividing the cumulative cost by

labor-force levels. Column 5 ranks these burdens against the national average. All labor force data taken from the

Bureau of Labor Statistics databases.

State LFPR Openings DLC % LF Burden Rank

Alabama 56.4 6.4 5% $ 2,882 119%

Alaska 66.0 8.7 6% $ 3,006 124%

Arizona 60.7 7.4 5% $ 2,760 114%

Arkansas 56.3 6.4 6% $ 3,093 128%

California 61.5 6.3 4% $ 2,266 94%

Colorado 68.5 7.6 4% $ 2,098 87%

Connecticut 63.6 6.7 4% $ 2,004 83%

Delaware 61.3 7.9 5% $ 2,659 110%

District of Columbia 71.7 5.3 3% $ 1,825 76%

Florida 58.6 7.3 5% $ 2,851 118%

Georgia 61.8 7.5 5% $ 2,424 100%

Hawaii 60.4 6.9 3% $ 1,596 66%

Idaho 61.8 7.2 4% $ 2,200 91%

Illinois 63.7 7.6 5% $ 2,437 101%

Indiana 61.9 7.4 5% $ 2,618 108%

Long Covid Impact on Americans:

Early Indicators Estimating Prevalence and Cost

solvelongcovid.org 19

State LFPR Openings DLC % LF Burden Rank

Iowa 66.8 7.2 4% $ 2,302 95%

Kansas 66.1 6.4 5% $ 2,586 107%

Kentucky 58.0 8.0 6% $ 2,952 122%

Louisiana 58.0 6.8 5% $ 2,895 120%

Maine 59.3 8.8 3% $ 1,388 57%

Maryland 65.6 7.5 3% $ 1,613 67%

Massachusetts 65.8 7.1 4% $ 2,270 94%

Michigan 59.4 7.8 5% $ 2,510 104%

Minnesota 67.6 8.1 4% $ 2,282 94%

Mississippi 54.9 6.4 6% $ 3,094 128%

Missouri 63.1 7.5 4% $ 2,304 95%

Montana 62.1 7.5 4% $ 2,301 95%

Nebraska 69.7 7.8 4% $ 2,223 92%

Nevada 59.5 6.7 4% $ 2,338 97%

New Hampshire 65.2 8.8 4% $ 1,932 80%

New Jersey 62.7 6.7 5% $ 2,444 101%

New Mexico 56.6 7.7 5% $ 2,649 110%

New York 59.1 5.9 3% $ 1,867 77%

North Carolina 59.7 7.2 5% $ 2,524 104%

North Dakota 68.8 7.6 5% $ 2,911 120%

Ohio 61.5 7.0 4% $ 2,423 100%

Oklahoma 60.1 6.6 5% $ 2,767 115%

Oregon 62.6 7.0 3% $ 1,506 62%

Pennsylvania 61.1 8.3 4% $ 2,233 92%

Rhode Island 63.2 7.6 6% $ 3,195 132%

South Carolina 57.1 7.7 6% $ 3,043 126%

South Dakota 68.4 6.9 5% $ 2,601 108%

Tennessee 60.3 7.6 6% $ 2,956 122%

Texas 63.3 6.3 4% $ 2,302 95%

Utah 67.5 7.3 5% $ 2,769 115%

Vermont 60.9 8.0 3% $ 1,522 63%

Virginia 62.9 7.2 4% $ 1,924 80%

Washington 64.2 5.8 3% $ 1,686 70%

West Virginia 55.0 7.1 6% $ 2,941 122%

Wisconsin 66.4 7.0 5% $ 2,596 107%

Wyoming 63.7 7.2 5% $ 2,674 111%

Total US 62.2 7.2 4% $ 2,417 100%

Long Covid Impact on Americans:

Early Indicators Estimating Prevalence and Cost

solvelongcovid.org 20

The Bureau of Labor Statistics also produces a monthly survey of labor churn, the Job Openings and Labor Turn-

over Survey (JOLTS), which is the source of the job openings rate shown in column 2. (JOLTS also tracks quits,

layoffs and hires.) These metrics run in long-term trends, with some states generally having less labor churn, and

others having more. The number of job openings are commonly considered as a share of total employment and

the national average, 7.2% in January, oats on a good deal of churn. For example, in January, Washington DC,

5.3%, and New York and Washington state, 6%, reported the lowest rates, while rates rounded up to 9% in Alas-

ka, New Hampshire, and Maine.

This table presents the more conservative case counts generated by the Reported Case Model, and includes only

Disabling Long Covid cases. Considering cases as a percentage of the labor force, instead of the general popula-

tion, captures the differences in labor force participation around the country. Rhode Island, which has the high-

est DLC infection rate, also has a low participation rate, and infections as a share of the labor force total to 6%,

double the shares in states with low infection and/or high participation rates. In North Dakota, which has a strong

participation rate and the second highest infection rate, the labor-force share of infections is 5%.

Table 4 sets out cumulative costs of Long Covid by state, but to make that meaningful in a country where state

labor forces run from about three-hundred thousand in Wyoming and Vermont to fourteen million in Texas, and

nineteen million in California, we calculated the share of that cost per labor force participant. For the tightest

metric, DLC taken from the Reported Case Model, the national average is $2,417, but within that Maine’s share

per participant, $1,388, is just 57% of the national average, and Oregon’s 62%. The shares in ve states running

above $3,000.00, Alaska, Arkansas, Mississippi, Rhode Island and South Carolina, run from 124% to 132% of the

national average. These calculations illustrate the disproportionate economic burdens different states will carry in

the coming years.

We’ve included the national averages across the bottom of the table as a frame for the rates among the states.

For example, although the DLC infection rate for California is average, the openings rate is lower than the national

average, which suggests less difculty lling positions, whereas in other states, including Rhode Island, South

Carolina and Tennessee the openings rate is above average, as is the infection rate, suggesting a higher hurdle.

We did not show the serology model estimates due to the limitations of this data (see Methodology pg 14), but

they tell the same story at higher percentages.

Long Covid Impact on Americans:

Early Indicators Estimating Prevalence and Cost

solvelongcovid.org 21

ANALYSIS

Long Covid: A Tragic Opportunity

The signicant numbers of those impacted by Disabling Long Covid (DLC) highlight the need for changes to the

structure of US disability benet programs, as demand exponentially increases. “One study of nearly 4,000 Long

Covid patients found that 45 percent reduced their work hours. For some, the change in job status can affect

health insurance, which can further complicate treatment options.”

37

It’s also important to note that a dispropor-

tionate number of Long Haulers are people who work in health care; rst responders, doctors, nurses, hospital

staff, home-health care, and clinic support teams, all of which are areas experiencing labor shortages. Addition-

ally, a disproportionate share of health-care workers in high contact positions are people of color.

38

Given this

reality, Long Covid is forcing us to recalibrate how we value our care workers.

The undercounting of COVID-19 cases has been a persistent issue throughout the pandemic that creates uncer-

tainty around the true number of people who may experience post-COVID symptoms. An analysis by the CDC

from November 2021 estimates that only 1 in 4 COVID cases have been reported, putting the total COVID case

count for this estimate at 146.6 million cases.

39

If this gure is correct, this rate of infection would result in 44 mil-

lion cases of LC, 14.6 million of which result in signicant disability. This projection estimates a similar caseload to

that given by our team’s Seroprevalence model–except the CDC’s estimate was made prior to the Omicron surge.

The projections of the number of both LC and DLC included in this paper, therefore, may be an underestimate

and so provide a oor. Remembering that the oor rests at approximately seven million potential workers who are

suddenly unable to work full time, or at all, may give us the commitment and courage to tackle these long-running

imbalances.

A cursory review of scholarship related to people working with a disability makes it clear that the rst priority is

keeping workers on the job. That is underscored by recent Bureau of Labor statistics data: 31.4% for those with a

disability aged 16 to 64 are employed, as are 72.5% without a disability. The unemployment rate for those with a

disability (10.1%), twice the rate of those without a disability (5.1%).

40

Using somewhat different metrics, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports that 26% of

Americans, or 61 million people, have some kind of disability.

41

However, these statistics fail to capture the plight

of many working with disabilities or chronic illness, who maintain their employment by utilizing sick leave, seeking

accommodations, passing on potential opportunities, or sacricing other parts of their lives. Many of those newly

disabled by DLC held productive jobs and have been fully attached to the labor force, but their illness still plagues

them in immeasurable ways. Being creative about how to retain those with DLC in the workforce will help others

in the disability spiral to get back to work as well.

Long Covid Impact on Americans:

Early Indicators Estimating Prevalence and Cost

solvelongcovid.org 22

A Ragged Map

It is useful to separate the overall prevalence of LC—the experiencing of any lingering post-COVID symptom—

from the impact of disability caused by LC on specic states and regions. Many of the states with the highest rates

of COVID infection and projected Long Covid rates, such as Southern states, suffer from long-running economic

and healthcare disparities. This is especially the case for the rural, working-poor within these states. The long-

term impacts of COVID will exacerbate existing disparities in states that experienced higher levels of disability and

poverty and lower levels of healthcare access prior to the pandemic. It is important to note that states and regions

more heavily affected by COVID were more likely to experience lower vaccination rates and a slower uptake of

vaccines, further increasing the risk of Long Covid.

42

Firstly, labor force participation rates – the share of the population over the age of sixteen who are working or

looking for work – varies by state. As mentioned above, the lowest rates, in the mid-50%, are in Alabama, Ar-

kansas, Mississippi, and West Virginia. While the highest rates, around seventy percent, are in Nebraska, South

Dakota, Minnesota and Iowa. (A searchable database

43

from the very useful Federal Reserve Economic Data

engine maintained by the Saint Louis Fed that presents these trends over time.)

The trajectory of DLC cases will play out within the varying economic conditions of each state. Although we

cannot know if the people sidelined by DLC were in the labor force prior to diagnosis, the share of the popula-

tion working or willing to work provides a useful economic frame. For this reason, we calculated the projected

case numbers as shares of the labor force for each state. A snapshot of the disparities visible in two states with

populations of similar size is a comparison between Kentucky and Oregon. Kentucky’s population is just 6% larger

than that of Oregon, and the labor force participation rate in Kentucky is 57%, compared to 62% in Oregon. The

projected number of DLC cases in Kentucky, however, is 114,276, about twice the expectation in Oregon, 61,860.

Kentucky’s share would amount to 6% of the labor force, twice Oregon’s projected rate of 3%.

In their latest report on disability outlays and rates, the CDC reported that Kentucky spent about 41% of their

health care budget on persons with a disability, or $14 billion, at a level of $15,177 per person, and persons with

disabilities make up 35% of the over-18 population.

44

In Oregon, the share drops to 26% of the over-18 popu-

lation, with spending running at 40% of the health-care budget, or $11.9 billion, and $16,127 per recipient. The

higher rate in Kentucky would consume about twice the share of the budget as would the lower rate in Oregon. At

$17,776 per LC patient, this is a painful stressor on an already overextended system.

45

Since previous employment rates among those impacted by Long Covid remain a true “known unknown,” these

estimates are limited in predicting the true impact across various regions. Nevertheless, these models serve as a

loud wake-up call for policy makers in each state.

Long Covid Impact on Americans:

Early Indicators Estimating Prevalence and Cost

solvelongcovid.org 23

Put Work-First Strategies First

In a seminal paper written in 2014, Richard Burkhauser, Mary C. Daly, Duncan McVickar, and Roger Wilkins

tracked work strategy reforms in three Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) coun-

tries, looking for clues for policy makers in the United States.

46

They documented how, despite the gatekeeper

standards here in the United States being quite strict compared to other countries, rates of those receiving ben-

ets did rise when Congress raised wage replacement rates. Then, these same rates fell in late 1970s as gate-

keepers were urged to interpret rules more strictly, and, again, in the 1980s when Congress mandated the Social

Security Administration to recheck recipients and conrm that they still qualied. These changes, “rigorously

enforced by the SSA at the start of the Reagan administration,” resulted in a “substantial drop” in those receiving

benets in spite of a major recession. Later, in 1984, policymakers responded to backlash against an unrealistical-

ly high bar for disability qualication and moved toward a more organic evaluation of individual workers’ abilities to

work, allowing mental health and physical pain to be considered.

Two things jump out from our clouded past that are crucial to any current Long Covid disability discussion. First,

early reports indicate that a number of people suffering from LC will be able to work on some days and not on

others. There is growing research showing that people who live with chronic illness in which there is no timeline

for recovery, or those with similar disabilities, with appropriate medical care and accommodations may, over time,

increase their energy envelope and accomplish an increasing number of tasks each day. As a care provider in

the eld noted in an informal meeting, “When your husband is sitting there with his head in his hands, he may be

thinking through what he can do that day….”

That dovetails with major lessons cited by the research team Burkhauser et al mentioned above: disability is not

an “immutable state,” but depends on the health as well as the economic, cultural and social environment of the

worker. When disability payments are restricted to those with total and permanent impairments, the impact is a

system that lacks the agility needed to support the reality of many illnesses that ebb and ow. Johnson et al’s next

point is that disability programs must reect the true spectrum of disability. Programs that sought to keep those

with impairment in the labor force led to better outcomes for the system and the individual. Programs that reect

multiple levels of disability are better suited for keeping those with mild or moderate disability in the workforce.

Creating disability categories for those needing partial assistance would make it possible for those with partial

impairment to stay in the labor force.

Enabling people with LC to remain in the labor force without sacricing their remaining health is the current

pre-eminent challenge and one thing is clear: employers themselves are going to have to make real efforts to ac-

commodate their workers. In many cases, this will require a change in workplace culture that may ultimately prove

benecial and be embraced by workers and employers alike. Creating a path to the workplace for individuals with

disabilities and chronic illness will be part of the solution to labor shortages.

Long Covid Impact on Americans:

Early Indicators Estimating Prevalence and Cost

solvelongcovid.org 24

A Carrot & A Stick

Shifting the focus to the employer is in line with the new denition of “work disability” advanced by the World Health

Organization over the last decades, an evolving codex of the identied impairment, workplace accommodations, and

the nancial benets of staying in or leaving the workforce. Elsewhere Mary Daly and Richard Burkhauser argue that

“experience ranking” disability contributions ultimately means that the full cost of individual employers’ unwillingness

to accommodate and rehabilitate employees is borne by the employers themselves.

47

They suggest offering a “car-

rot” to employers who make accommodations for workers in the form of reduced Social Security Disability Insurance

taxes. This makes nancial sense since keeping workers who have developed a disability employed makes them

less likely to move into long-term disability. And the “stick” for those who don’t? Of course, a higher contribution.

Let’s take one example, the Netherlands. In 2002, after decades of trying to rein in their disability system, previous-

ly considered by some the worst in the industrialized world, the Dutch fundamentally transformed their system by

replacing work itself as the expectation in lieu of cash transfers. They increased incentives for both employers and

employees to use accommodations and rehabilitation in order to get back to work following the onset of disabili-

ty. Workers were now the responsibility of the employer for two years, and during that period of time could only be

dismissed if they refused “reasonable work requirements.” Firms were given best practices to implement and paid

premiums covering the rst ten years of a partial disability benet. Long considered out-of-control, the Dutch system

became an example of how a country could learn from mistakes, one that other countries could follow.

Sweden instituted similar changes in 2000, bringing rehabilitation and vocational trainers in early, and requiring

checkpoints at three, six and twelve months. These early interventions and accommodations stemmed the ow of

new applicants into long-term disability. In other words, many of those with new disabilities wanted to work, were

capable of work, and worked when given appropriate support and accommodations. Employers should investigate

providing similar rehabilitation and vocational support services to newly disabled employees to potentially prevent

the loss of valuable talent.

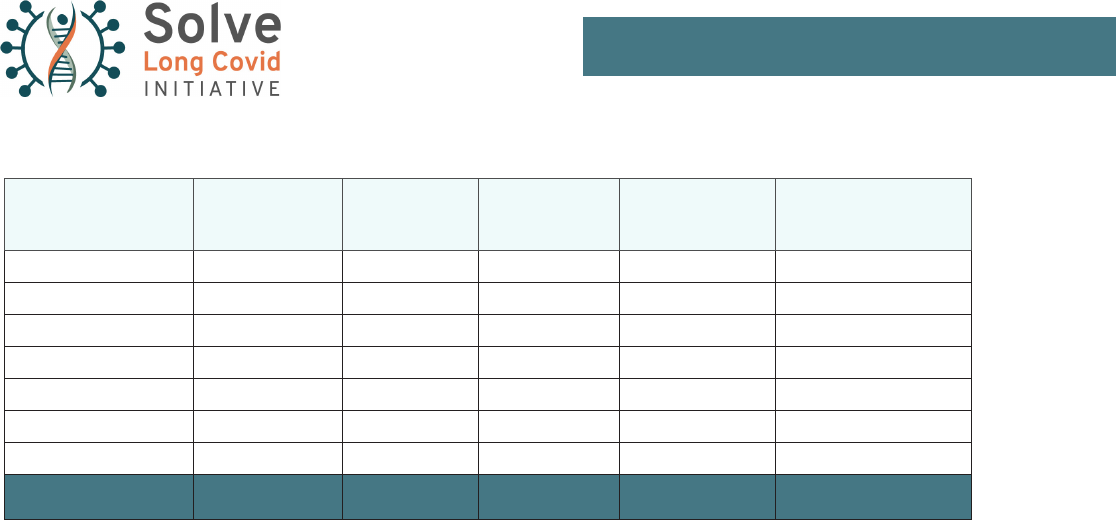

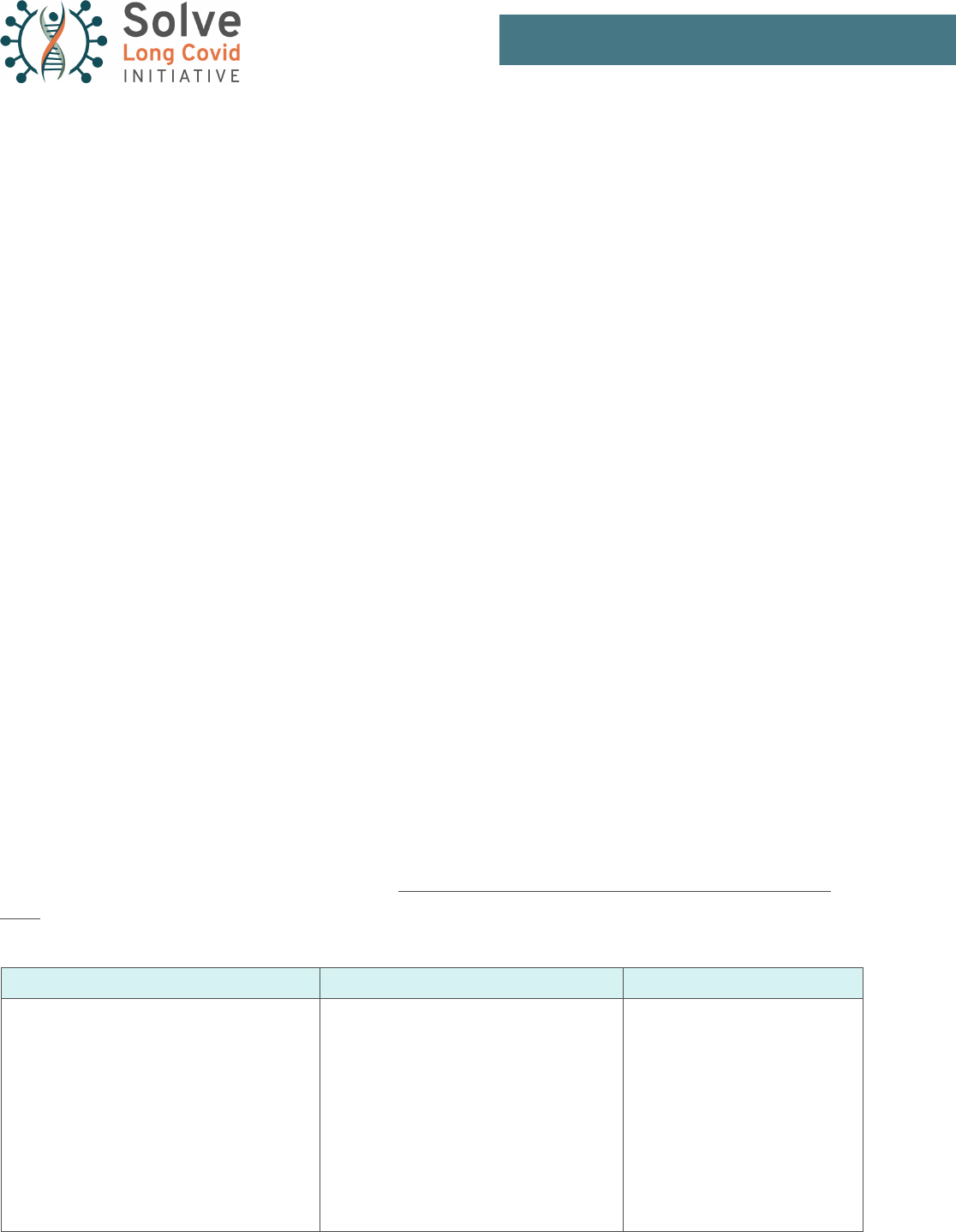

Table 7. Partial List of Potential Modications for Workers with Post-infection Illness By Symptom.

The possible modications listed below are from the U.S. Department of Labor’s Job Accommodation Net-

work’s chronic fatigue syndrome webpage. This table identies a selection of accommodation ideas, presented

here by overlapping symptoms with Long Covid.

Decreased Stamina/Fatigue Memory Loss/Brain Fog Light Sensitivity

• Scooters

• Ergonomic and Pneumatic tools, assessments

and equipment

• Flexible schedule

• Job restructuring / medical leave

• Periodic rest breaks

• Telework, working from home, working remotely

• Stand-lean stools

• Wheelchairs

• Modied Workplace

• Aide/Assistant/Attendant

• Additional training time / training refreshers

• Electronic organizers

• Job coaches

• Professional organizers

• Recorded directives, messages materials

• Reminders

• Support Person

• Visual schedulers

• Written instructions

• Memory software

• Timers and watches

• Alternative lighting

• Anti-glare lters

• Additional shields, shades

• LED light lters

• Lighting gel lters

• Non-uorescent lighting

• Personal visors

• Telework, working from home,

working remotely

• Simulated skylights or windows

Long Covid Impact on Americans:

Early Indicators Estimating Prevalence and Cost

solvelongcovid.org 25

Disability Benets

The convoluted requirements of our current system have the unintended consequence of discouraging disabled

workers from staying in the labor force and creating disproportionate barriers for those with complex, invisible

disabilities, like post-infection illnesses. First, they don’t recognize partial disability, which is already emerging as

a common characteristic of Long Covid. Second, by capping what someone drawing disability benets can earn

in the market, by denition, prevents people from working if and when they can. Counterproductively, these caps

create a barrier for those who are able and willing to contribute to the workforce part-time or with accommodations

when their symptoms are less severe. Administering a system that makes up a percentage of lost wages was

once an overly complicated process of algorithms, but advances in technology have made it simpler and attain-

able. And third, although those who receive disability benets have work options, the pages on which the Social

Security Administration outlines the steps required to return to the disability system after a failed work stint are

littered with “you may be able,” not you “will” be able. Thus, recipients are penalized just for trying to work since a

job that doesn’t work out can cause a recipient to lose all support.

Burkhauser et al also push back against the most common opposition to reform—that millions of disabled workers

rely on disability transfers to stay out of poverty—with evidence from European experiments. Specically, prioritiz-

ing accommodations for disabled workers can increase employment and improve personal outcomes, especially

when they replace programs, like ours, that create barriers to working. Their “most important” lesson is that poli-

cies that encourage employers and employees to work together, especially with government programs that guide

employers with best practices, can lower long-term costs and simplify the assessment process. Beyond the cost

savings, such reforms of our disability system improve opportunities for those with disabilities.

48

Wages Are Values

Dr. Mary Daly, a Professor of Social Policy at Templeton College in Oxford, has related insights into this topic. Dr.

Daly studies the value of undervalued care work, whether paid or unpaid, and her work focuses on care economy,

distinct from other research that advances care as a social good. She notes that in the United States, the U.K.

and less so in Australia, care work tends to be underpaid, with training limited, and as a “poor sector” or even an

“unproductive” sector of the economy, is easily ignored. Dr. Daly sees the Long Covid crisis as an opportunity to

rethink this, and one that has yet to be fully put to use.

49

Leisure and hospitality workers have received substantial and appropriate pay increases since the onset of the

pandemic. As a reminder of the promises we made to our essential workers at the beginning of the pandemic,

among production and nonsupervisory workers, overall private-sector earnings have increased 12% since Febru-

ary 2020, with wages of bar and restaurant workers rising 16%, and a 15% rise among health care and private ed-

ucation. But home-health care workers’ earnings are up just 10% over this span, lagging behind the average. That

gets them to 80% of total private wages, better than restaurant workers’ 61%, but for a sector with an outsized

share of women and minority workers, this is an underpinning of inequality.

Long Covid Impact on Americans:

Early Indicators Estimating Prevalence and Cost

solvelongcovid.org 26

The persistent low wages of home healthcare workers are not a smart move. In September 2021, the Bureau of

Labor Statistics projected home health and personal care aides to be the sector with the largest numerical growth

over the next decade, making them both the most in demand and among the lowest paid. Home-health care work-

ers have been the subject of several inquiries into the use of certain labor practices to depress wages, including

by the Treasury Department, and academics.

50

Considering the increase in demand created by newly disabled Long Covid patients, shortages in the home health

and personal care sector will ripple through the economy, as families will increasingly rely on them as they go

back to work. We will need to support workers and patients who need help here, remembering that communities

of color bear a disproportionate burden of Long Covid home-health care.

If Forecasts Matter…

If the number of DLC working age Americans ends up topping seven million (as suggested by our reported case

model estimate), it will be in range of the close to eight million workers who lost their jobs by the lowest point of

the Great Recession of 2008. Such an impact is crushing even when compared to the more severe, if partially

preventable, losses of the pandemic. Additionally, the projected number of those who will be affected by LC, even

if of a more transitory nature, already meets that bar. If the number of working age Americans disabled by Long

Covid ends up topping 14 million (as suggested by our seroprevalence model estimate), the impact will be seismic

in scope and scale.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, there are currently about 11 million unlled jobs in the United States.

51

While that gure may be inated by window-shopping employers, to say that’s an all-time high doesn’t do it jus-

tice. The current “openings rate,” the number of openings as a share of total employment,

52

stands at 7%, more

than double the average of 3.1% before the pandemic. State job opening rates run in long-term trends, but it’s

worth noting that some large states with smaller shares of their labor forces affected by DLC, like California and

Washington, have job opening rates lower than the national average, while some states, especially Alaska and

South Carolina, face the challenge of both an infection and a job opening rate above the national average. In re-

ality, the post-infection illness’ impact may lack the drama of sudden declines, but even the dragged out effects on

personal well-being will almost certainly depress the productive side of the economy, while raising wages.

If there is any value to trying to predict demographic trends, it’s to bring the outcomes in line with our values.

Strengthening supply chains while keeping workers attached to the labor force is a goal we all agree on. As Long

Covid patients become commonly recognized in society, employers will need to take an active role supporting the

workers they need, being exible, and trusting them to work from home when necessary and working with patients

to nd appropriate accommodations to their workplace needs. Public/private partnerships will need to be strength-

ened, and short-term support for those recently affected by DLC will need to be exible. Help with child and elder

care; job sharing, a successful strategy that can be a partnership among workers in recovery, may need to be

broadened and restructured to remove barriers for people with Long Covid and other post-infection illnesses.

Long Covid Impact on Americans:

Early Indicators Estimating Prevalence and Cost

solvelongcovid.org 27

CONCLUSIONS

Post-infection illness is not new and insights drawn from both pre-pandemic knowledge of post-infection illnesses

and post-pandemic knowledge of Long Covid can be incredibly helpful to analyzing early indicators to estimate

prevalence and nancial burden. Utilizing two models of Long Covid cases in the United States, derived from

prior population data and serology data, our modeling predicts a range of cases between 22 to 43 million Ameri-

can adults at a potential cost to adult Americans with Long Covid ranging from $386 billion to $511 billion through

January 31, 2022.

If these models prove accurate, Long Covid will have a potentially catastrophic impact on disability systems, work-

places, and millions of families across America. These models may have limited use, but their message is clear;

‘There is no realistic scenario in which the Long Covid impact on American systems, workplaces, and families is

small.’ Instead, these models provide a rst glimpse, like the tip of an iceberg, of a massive incoming systemic

shock that urgently needs to be addressed by business and government leaders.

On top of the challenges posed by Long Covid itself, the Urban Institute recently projected that thirteen to fourteen

million Americans are likely to lose Medicaid coverage in the coming year.

53

The challenges presented by post-in-

fection syndromes are not demand issues and can’t be resolved by the market alone. It’s a colossal challenge for

a fractured nation, but working together can improve the outlook for many of our co-workers, friends, and family

while shoring up the market economy. With these considerations, we draw these key conclusions:

● Government and business leaders should prioritize policies, guidelines, and programs that keep workers

on the job through workplace accommodations and vocational support programs.

» This includes: part-time, exible, and/or reduced hours, reasonable accommodations (including

telework), assistive technologies, and medical leave.

● Disability is not an “immutable state;” Invest in short-term and mid-term disability programs designed to

empower a patient to return to work as they heal, rather than creating barriers to working

● Stop approaching disability payments exclusively as a payment of last resort for those with total and per-

manent impairments. This limits what can be done within the system. Instead, reduce barriers for access-

ing disability, returning to work, and returning back to disability as needed.

● Employers themselves will need to make sincere efforts to accommodate their workers with post-infection

illness, something that for many may be new.

● Special consideration should be given to communities of color, disproportionately impacted by the pan-

demic, Long Covid, and post-infection illnesses.

● Key workers, like home-care and nursing, must be valued more highly and will face signicant increases

in demand as a result of Long Covid.

Long Covid Impact on Americans:

Early Indicators Estimating Prevalence and Cost

solvelongcovid.org 28

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

A special thanks to COVID-19 Longhauler Advocacy Project, whose economic impact work as part of “An Open

Letter to President Biden, Cabinet and Congressional Leadership and Key Government Agencies” pub-

lished the nancial calculations utilized here.

The authors would like to acknowledge the Patient Led Research Collaborative for their exceptional work “Char-

acterizing long COVID in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact” which has

educated and informed so many.

With heartfelt gratitude, we’d like to thank our reviewers for their insights and input; Oved Amitay, Karyn Bisoff,

Jessica Brown-Clark, Hannah Davis, Stewart Gittleman, Leslie Phillips, Reva Singh, and Lauren Stiles.

Deepest thanks to Stephanie Mackay, a true pioneer in bringing those with disabilities into the labor force, both

her generosity in discussing impediments outlined in this paper, and for her decades of invaluable work.

Authors

Philippa Dunne has long studied long-term labor trends with an emphasis on inequity and exclusion. Always on

the hunt for economic narratives to debunk, she is currently advancing research that breaks down the false di-

chotomy between economic and ecological outcomes. She is co-editor of TLRAnalytics, and Director of Outreach

at Hudsonia, a small for-not-prot ecological research rm.

Melissa Smallwood (MS 2021, MA 2016) is a Science and Technology Policy researcher with a background in

neuroscience, psychology, social science, and disability studies. She is a recent graduate of Arizona State Uni-

versity's School for the Future of Innovation in Society, where she worked on her Master's Thesis with Brian David

Johnson's Threatcasting lab. Her current work explores the long-term policy implications of Long-Haul COVID-19

and other enduring consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic. Her other interests include the bioethical dimen-

sions of neurological and genetic technologies.

Emily Taylor is the Vice President of Advocacy and Engagement at Solve M.E. with over fteen years of policy,

organization, and advocacy experience around issues of disability and patient empowerment in both the non-prot

and government sectors. She received a B.A. with honors in politics and international relations from Scripps College

in Claremont and earned her M.A. in American politics from Claremont Graduate University. Emily draws inspiration

from her mother who has battled ME/CFS as well as chronic autoimmune and thyroid conditions since 1999.

Long Covid Impact on Americans:

Early Indicators Estimating Prevalence and Cost

solvelongcovid.org 29

REFERENCES AND CITATIONS

C-19 LAP (2021). Mathematical Breakdown and Formulas for Long COVID Calculations. COVID-19

Long-Hauler Advocacy Project. https://www.longhauler-advocacy.org/calculations-formulas

CDC Case Task Force (2022). United States COVID-19 Cases and Deaths by State over Time [Dataset].

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://data.cdc.gov/Case-Surveillance/United-States-COVID-19-

Cases-and-Deaths-by-State-o/9mfq-cb36

Job Accommodation Network, & Loy, B., (2018). Accommodation and Compliance Series: Employees with

Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Accommodation and Compliance Series. https://askjan.org/disabilities/Chronic-Fa-

tigue-Syndrome.cfm.

Kuodi, P. et al. (2022). Association between vaccination status and reported incidence of post-acute

COVID-19 symptoms in Israel: a cross-sectional study of patients tested between March 2020 and November

2021. MedRxiv [Preprint]. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.01.05.22268800v2

Millman, J. (2022). NY Breakthrough Infection, Unvaccinated Case Rates Both Halved in Week as Omi-

cron Recedes. NBC New York. https://www.nbcnewyork.com/news/coronavirus/omicron-ny-covid-cas-

es-breakthrough-infection-fully-vaccinated-symptoms/3504616/

NYC Health (2022). COVID-19: Data [Dataset]. New York City Department of Health. https://www1.nyc.

gov/site/doh/covid/covid-19-data.page

U.S. Government Accountability Ofce. Science & Tech Spotlight: Long COVID. March 2, 2022. Science,

Technology Assessment, and Analytics. https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-22-105666.pdf

Whitaker, M. et al. (2021). Persistent symptoms following SARS-CoV-2 infection in a random community

sample of 508,707 people. MedRxiv [Preprint]. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.06.28.2125945

2v1

Long Covid Impact on Americans:

Early Indicators Estimating Prevalence and Cost

solvelongcovid.org 30

ENDNOTES

1

Groff D, Sun A, Ssentongo AE, et al. Short-term and Long-term Rates of Postacute Sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 Infection: A

Systematic Review. JAMA Network Open. 2021;4(10):e2128568.

2

L.A. Jason & A.A. Mirin (2021) Updating the National Academy of Medicine ME/CFS prevalence and economic im-

pact gures to account for population growth and ination, Fatigue: Biomedicine, Health & Behavior, 9:1, 9-13, DOI:

10.1080/21641846.2021.1878716

3

Bourne, KM, Chew, DS, Stiles, LE, Shaw, BH, Shibao, CA, Okamoto, LE, Garland, EM, Gamboa, A, Peltier, A, Diedrich, A,

Biaggioni, I, Sheldon, RS, Robertson, D, Raj, SR (University of Calgary; Duke University School of Medicine, Durham; Stony

Brook University School of Medicine; Dysautonomia International, East Moriches; Vanderbilt Autonomic Dysfunction Center,