ReporttoCongressonInternational

EconomicandExchangeRatePolicies

U.S.DepartmentoftheTreasury

OfficeofInternationalAffairs

October15,2009

Thisreportreviewsdevelopmentsininternationaleconomicandexchangeratepolicies,focusingonthe

firsthalfof2009,

andisrequiredundertheOmnibusTradeandCompetitivenessActof1988,22U.S.C.§

5305(the“Act”).

1

1

TheTreasuryDepartmenthasconsultedwiththeBoardofGovernorsoftheFederalReserveSystemandIMF

managementandstaffinpreparingthisreport.

Table of Contents

Key Findings .................................................................................................................................. 2

Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 2

U.S. Macroeconomic Trends ........................................................................................................ 5

Global Economy ............................................................................................................................ 8

U.S. International Accounts ......................................................................................................... 9

The Dollar in Foreign Exchange Markets ................................................................................ 11

Analysis of Individual Economies.............................................................................................. 12

Asia ........................................................................................................................................... 12

China .................................................................................................................................... 12

India ...................................................................................................................................... 15

Japan .................................................................................................................................... 16

Malaysia ............................................................................................................................... 18

Singapore .............................................................................................................................. 19

South Korea .......................................................................................................................... 21

Taiwan .................................................................................................................................. 22

Europe ...................................................................................................................................... 23

Euro Area ............................................................................................................................. 23

Norway .................................................................................................................................. 24

Russia ................................................................................................................................... 25

Switzerland ........................................................................................................................... 26

United Kingdom ................................................................................................................... 28

Middle East .............................................................................................................................. 29

Gulf Cooperation Council ................................................................................................... 29

Saudi Arabia ......................................................................................................................... 29

Western Hemisphere .............................................................................................................. 30

Brazil..................................................................................................................................... 30

Canada .................................................................................................................................. 32

Mexico .................................................................................................................................. 33

Venezuela ............................................................................................................................. 34

Appendix 1: An Historical Perspective on the Reserve Currency Status of the U.S. Dollar

....................................................................................................................................................... 36

Appendix 2: Report to Congress on IMF Bilateral and Multilateral Surveillance over

Members’ Policies ....................................................................................................................... 38

1

Key Findings

The Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of 1988 (the “Act”) requires the Secretary of the

Treasury to provide biannual reports on the international economic and exchange rate policies of

the major trading partners of the United States. Under Section 3004 of the Act, the report must

consider whether any foreign economy manipulates its rate of exchange against the U.S. dollar to

prevent effective balance of payments adjustments or to gain unfair competitive advantage in

international trade. For the period covered in this Report, January 1, 2009 to June 30, 2009,

Treasury has concluded that no major trading partner of the United States met the standards

identified in Section 3004 of the Act.

The Report further finds that the financial crisis that began in the summer of 2007, and

intensified in the fall of 2008, was especially severe in the last quarter of 2008 and the first

quarter of 2009. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has estimated that global real GDP

declined at an average annual rate of 6.5 percent during the first quarter of 2009 and international

trade fell sharply, contracting at an annual rate of 54 percent. Industrial production is estimated

to have declined by 18 percent. By early March 2009, global equity prices were down by 60

percent from their peak in October 2007. On a nominal effective basis, the dollar strengthened

5.9 percent in the fourth quarter of 2008 and a further 3.7 percent during the first quarter of 2009

as risk appetite fell sharply. There was widespread agreement that the crisis represented the

greatest economic challenge in more than a generation, and there was growing concern that the

world economy could be on the edge of a new depression

On April 2, 2009, Leaders of the G-20 met in London and pledged to do “whatever is necessary”

to restore confidence, growth, and jobs; repair the financial system and restore lending; and

maintain the global flow of capital. Pledges were made to deliver extraordinary fiscal and

monetary stimulus and financial sector support – the largest and most comprehensive global

stimulus program in modern times. In addition, G-20 Leaders pledged to make available an

additional $850 billion to international financial institutions to support emerging markets and

they committed to a substantial strengthening of financial market regulation and supervision.

The U.S. Administration, together with the U.S. Congress, had already begun taking exceptional

action to arrest the economic decline with emergency demand support measures under the

February 2009 $787 billion American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA). This was

buttressed by the Administration’s Financial Stability Plan (FSP) to strengthen credit, housing,

and financial markets, and by the joint Treasury/Federal Reserve bank stress tests conducted

under the Supervisory Capital Assessment Program (SCAP). Virtually every G-20 member

country and all the economies listed in this Report have put in place exceptional monetary and

fiscal measures to bolster demand and support a rejuvenation of growth.

These forceful interventions on a coordinated global scale worked. In the few months following

the April Leaders’ meeting, global economic growth turned positive, industrial production

bottomed and began increasing, international trade increased 10.2 percent, financial markets

improved sharply as interest rate spreads declined and access to credit broadened, and consumer

and business confidence improved. Globally, capital began flowing once again as risk aversion

began to dissipate. As moderation in downside risks prompted global investors to once again

shift their portfolios toward more risky assets, the dollar retraced some of its previous rise.

2

Despite the recent improvements in financial markets and economic growth, the global economic

recovery remains incomplete. Private-sector demand remains weak and unemployment in many

countries remains unacceptably high. To help guide the recovery and to reduce the risk and

incidence of future crises, G-20 Leaders agreed at the Pittsburgh Summit on September 24-25 to

launch a new Framework for Strong, Sustainable, and Balanced Growth. The goal of the

Framework is to help to ensure a better balanced global economy that is less prone to crisis and

to secure the ability to quickly mobilize early intervention in the event of prospective instability.

As part of the Framework, G-20 members with sustained, significant external deficits pledged to

undertake policies to support private savings and fiscal consolidation while maintaining open

markets and strengthening export sectors. G-20 members with sustained, significant external

surpluses pledged to strengthen domestic sources of growth. The G-20 will establish a process

of mutual assessment to help evaluate the sustainability of policies and develop corrective

actions where necessary.

As noted, no major trading partner of the United States met the standards identified in Section

3004 of the Act during the most recent reporting period. All of the countries described in this

Report have put in place policies to boost their economies and expand domestic demand. Global

imbalances have fallen sharply during the crisis from a peak of 5.9 percent of world GDP to an

IMF-estimated 3.6 percent in 2009. The U.S. current account deficit has fallen from a peak of

6.5 percent of GDP in the fourth quarter of 2005 to 2.9 percent of GDP in the second quarter of

2009. Most U.S. bilateral trade deficits have fallen as well. Some of the correction in global

imbalances is the result of cyclical factors and may be reversed as the global economy recovers.

However, some is also structural – as with the rise in private sector saving in the United States.

Of the 17 currencies examined in this Report, two (the Saudi Arabia riyal and the Venezuelan

bolivar) are fixed against the U.S. dollar. Among the remaining 15 currencies, all except the

Norwegian kroner depreciated against the dollar in the first quarter of 2009, as capital flows to

emerging markets declined and investors continued to shift their portfolios into dollar assets.

During the second quarter of 2009, 14 of these currencies appreciated against the dollar, as

improvements in financial market conditions and the global outlook led to a return to more

diverse portfolios. Only the Chinese renminbi remained unchanged against the dollar in the

second quarter. This lack of movement of the renminbi has contributed to upward pressure on

more flexible currencies in the region. Several emerging markets in the region have intervened

in the foreign exchange market to slow the pace of appreciation.

Although China’s overall policies played an important role in anchoring the global economy in

2009 and promoting a reduction in its current account surplus, the recent lack of flexibility of the

renminbi exchange rate and China’s renewed accumulation of foreign exchange reserves risk

unwinding some of the progress made in reducing imbalances as stimulus policies are eventually

withdrawn and demand by China’s trading partners recovers.

On an effective basis, the renminbi has depreciated 6.9 percent since February 2009. From the

end of February through June, China’s reserves increased both as a result of valuation changes

and additional purchases associated with intervention. Both the rigidity of the renminbi and the

reacceleration of reserve accumulation are serious concerns which should be corrected to help

ensure a stronger, more balanced global economy consistent with the G-20 Framework.

Treasury remains of the view that the renminbi is undervalued. The United States will continue

to work with China both in the G-20 and the bilateral Strategic and Economic Dialogue to pursue

3

policies that permit greater flexibility of the exchange rate and lead to more sustainable and

balanced trade and growth.

Appendix 1 of the Report provides data on the currency composition of reserves over the past 30

years. Despite repeated predictions of the demise of the dollar as the major reserve currency, the

data show no significant diversification of global currency reserves away from the dollar.

Appendix 2 of the Report, required by the Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2009, Public Law

No. 111-32 (June 24, 2009) focuses on how to improve the effectiveness of IMF surveillance.

Rigorous bilateral and multilateral surveillance by the IMF will help shed light on trends that

could lead to the next unsustainable boom and allow preventative or corrective measures to be

put in place. Under the G-20 Framework for Strong, Sustained, and Balanced Growth, the IMF

will provide forward-looking analysis of whether the world's major countries are implementing

economic policies, including exchange rate policies, which are collectively consistent with G-20

objectives.

4

Introduction

This report focuses on international economic and foreign exchange developments in the first

half of 2009. Where pertinent and when available more recent data and developments are

included.

Exports and imports of goods to and from the areas whose economies and currencies are

discussed in this report accounted for more than 80 percent of U.S. merchandise trade in the first

half of 2009.

U.S. Macroeconomic Trends

The U.S. economy remained deep in recession at the start of 2009 but, as the first half of the year

drew to a close, signs of recovery began to emerge. The pace of economic contraction slowed

sharply in the second quarter as some sectors appeared to be stabilizing. Conditions in financial

and credit markets improved notably, and housing activity started to pickup during the spring

after a 3-year slump. Labor markets remained very weak but job losses began to moderate

midyear. Several new fiscal policy measures were put in place in early 2009 to stabilize

financial markets and put the economy back on the path towards long-term sustainable growth.

These initiatives, along with the injection of fiscal stimulus delivered by the American Recovery

and Reinvestment Act (the Recovery Act), enacted in mid February, are having the desired

impact. Financial market volatility decreased notably in the first half of the year, measures of

financial risk declined substantially, with some returning to pre-crisis levels, and credit flows

picked up considerably. Early indicators about the third quarter suggest that some sectors of the

economy are starting to recover. Most private forecasters expect moderate economic growth to

resume in the second half of 2009. The IMF projects US real GDP to decline by 2.7 percent in

2009 and rise by 1.5 percent in 2010.

2

The U.S. Economy Continued to Contract in the First Half of 2009

U.S. real GDP fell at an annual rate of 6.4 percent in the first quarter and at a 1.0 percent pace in

the second quarter. The second-quarter drop was the smallest in a year, partly due to a pickup in

government spending which boosted real GDP by 1.3 percentage points. The rate of decline in

private spending also slowed in the second quarter as the pullback in business investment

moderated and the downturn in residential investment slowed. Private inventories continued to

shrink but the drawdown was a smaller drag on growth in the second quarter, subtracting 1.4

percentage points from real GDP growth after reducing growth by 2.4 percentage points in the

first quarter. Consumer outlays fell by 0.9 percent following a modest 0.6 percent increase in the

first quarter. Exports and imports both declined but the drop in imports was larger. As a result,

net exports rose, boosting real GDP by 1.6 percentage points in the second quarter. Since the

previous business cycle peak in the fourth quarter of 2007, real GDP has fallen by an annual rate

of 2.5 percent – the largest six-quarter decline on record in the post-war period.

2

The IMF annually reviews U.S. economic performance and policies through the IMF Article IV surveillance

process. The last Article IV surveillance concluded in July 2009. The Article IV Staff Report and the results of the

IMF Executive Board’s discussion of the U.S. Article IV review can be found at

http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/cat/longres.cfm?sk=23144.0 In addition, the IMF discusses U.S. economic

policies and performance in the context of its twice yearly World Economic Outlook reports. These can be found at

http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2009/02/index.htm.

5

Labor Market Conditions Worsened

Labor market conditions continued to deteriorate in early 2009 as job losses accelerated and the

unemployment rate surged. During the first half of the year, 3.4 million jobs were cut from

nonfarm payrolls on top of the 3.1 million lost over the course of 2008. The unemployment rate

jumped by 2.3 percentage points between December 2008 and June 2009 to 9.5 percent and in

September stood at a 26-year high of 9.8 percent. Since the recession began in December 2007,

the jobless rate has risen by 4.9 percentage points.

While the labor market remained very weak heading into the second half of 2009, there were

signs that the rate of deterioration was slowing. The monthly pace of job losses moderated in the

third quarter of 2009 to 256,000, on average, from about 430,000 in the second quarter and

nearly 700,000 in the first quarter. Weekly initial claims data through September continued to

signal further job losses, but they also pointed to a slower pace of decline.

The Housing Sector Showed Tentative Signs of Stabilization

The housing market downturn entered its fourth year in 2009, but by spring housing activity

appeared to be stabilizing. Single-family housing starts appear to have hit bottom at the start of

the year and by August had risen by one-third from early 2009 lows. Permit issuance for future

construction also picked up in the first half of 2009 after falling steadily for more than three

years. Sales of both new and existing single-family homes have also moved off of the low levels

recorded in early 2009, and in August the combined total was near its highest level since late

2007. The inventory of unsold homes on the market retreated from a historically high level. In

August, the stock of new homes for sale was at its lowest level since 1992 and, relative to sales,

was approaching historical norms. Major house price measures started to stabilize at the end of

the second quarter, though they remained sharply lower than a year earlier.

Inflation Slowed Sharply

Consumer prices fell by 1.4 percent during the twelve months ending in June and were down by

1.5 percent over the year ending in August. A year earlier, headline consumer inflation was

around 5-1/2 percent. The dramatic reversal was due in large part to a steep drop in energy

prices. Food price inflation also moderated notably. Core inflation (excluding food and energy)

has also retreated, slowing from 2.5 percent in mid 2008 to 1.7 percent in June 2009, and 1.4

percent in August.

Conditions in Financial and Credit Markets Improved

Equity markets posted steep losses in 2008, triggered by weakness in the U.S. economy and

concerns about the performance and viability of a wide range of assets and the financial

institutions holding or guaranteeing those assets. Financial markets remained volatile at the start

of 2009 and equity markets continued to post losses well into the first quarter. In early March,

however, equities began to recover. From March 9 through the end of June, the S&P 500

jumped nearly 36 percent. This index has continued to post gains since mid year and through

October 1 had risen an additional 12 percent, bringing the increase so far in 2009 to 14 percent.

6

Credit market conditions improved in the first six months of 2009. The 3-month U.S. dollar

LIBOR-OIS spread – a measure of what banks perceive as the credit risk in lending to one

another – fell to 39 basis points at the end of June from 126 basis points in late December and an

all-time high of 365 basis points in early October 2008. This spread narrowed to around 14 basis

points by early October, close to the pre-crisis historical average of 9 basis points. Corporate

bond spreads also narrowed, pointing to a rising tolerance for risk. The spread between Baa-

rated corporate bonds and the 10-year Treasury note fell to 364 basis points in late June and

continued to ease through early October to 283 basis points. Though still elevated, this measure

is far below its December 2008 peak of 616 basis points. Mortgage rates dipped to new lows

early in the second quarter and, despite some upward movement, since then they remain at

historically low levels.

Additional Policy Measures Were Implemented to Stimulate the Economy

A number of monetary and fiscal policy measures were put in place in the latter half of 2008 to

stabilize financial and credit markets. With the economy weakening rapidly at the start of 2009

and markets still severely impaired, it became necessary to take additional action.

In February, Treasury introduced the Financial Stability Program, a set of initiatives to

strengthen financial institutions and jumpstart the flow of credit to households and businesses.

The first of these, the Supervisory Capital Assessment Program, subjected major banks to a

rigorous evaluation of their medium-term prospects. Following this highly transparent exercise,

major banks were able to raise a substantial amount of new capital. The Financial Stability

Program also expanded the scale and the scope of the Term Asset-Backed Securities Lending

Facility (TALF) in order to rehabilitate key channels of credit to households and businesses. The

announcement of the TALF’s launch in March helped narrow spreads, and the issuance of

consumer-related asset-backed securities has recovered substantially. Finally, the Financial

Stability Program created the Public-Private Investment Program to remove legacy assets from

bank balance sheets and re-liquefy key markets for financial assets. While this initiative has not

been implemented on the scale and scope originally anticipated, the government’s willingness to

commit resources to this effort likely contributed to the recovery of these markets.

Treasury also continued to play an active role in efforts to stabilize the housing market during the

first half of 2009. Treasury purchases of mortgage-backed securities and support to the

government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs), along with complementary policies implemented by

the Federal Reserve, helped hold down mortgage rates. The Making Home Affordable Program,

under which Treasury subsidizes mortgage modifications in order to reduce the incidence of

foreclosures. In early October, nearly one month ahead of the November 1 benchmark

established in July, more than 500,000 mortgages of distressed borrowers had entered a trial

modification period

To more directly stimulate domestic demand, Congress passed and President Obama signed the

American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (Recovery Act) in mid February. This $787 billion

stimulus package was designed to support income, saving, and consumption through tax cuts and

transfers to households, including the Making Work Pay tax credit, payments for unemployment

insurance, and one-time payments to Social Security and other eligible beneficiaries. Treasury

estimates indicate that nearly $63 billion in tax relief will have been made available by the end of

August 2009. Economic stimulus will also support necessary state programs and provide funds

7

for infrastructure investment. The spending from these programs will provide an important boost

to economic activity throughout 2009 and in 2010—by the end of September nearly $95 billion

in Recovery Act funds had been paid out by the government.

These measures are working. As noted above, financial markets have stabilized and conditions

in credit markets have improved dramatically since late last year. Measures of systemic risk

have declined substantially, with some returning to their pre-crisis levels, and there are clear

signs that the economy is stabilizing.

Temporary Stimulus Measures Contributed to Rising Federal Budget Deficit

The temporary measures to shore up the financial system and spur economic growth and job

creation along with lower revenues as a consequence of the recession have boosted the Federal

budget deficit. In FY2009, the deficit is projected to reach $1.6 trillion (11.2 percent of GDP).

Federal expenditures are expected to grow by 22 percent in FY2009, partly reflecting TARP

outlays and spending associated with the Recovery Act. Receipts are projected to fall by 18

percent, due in part to falling employment and income and declining asset values. The deficit is

expected to narrow once the temporary spending provisions of the Recovery Act expire and the

economy begins to improve, with the deficit averaging slightly more than 4 percent of GDP from

FY2012 to FY2019.

Global Economy

Global economic conditions continued to worsen in early 2009 and financial markets remained

under severe stress. Global trade plummeted and capital flows to emerging markets declined,

pushing down output, or sharply lowering growth rates in countries that had avoided the direct

effects of the financial crisis.

Real GDP in the G-7 economies fell at an annual rate of 8.6 percent in the first quarter of 2009,

the fourth consecutive quarterly decline, and the largest quarterly contraction in the post-World

War II era. Real GDP fell in all of the economies discussed in this report in the first quarter,

with the exception of China, India, and Korea.

3

China and India are the only two economies

discussed in this report that have not experienced a contraction in output during the crisis.

Nevertheless, growth has fallen sharply in both countries.

The severity of the crisis prompted an unprecedented coordinated response from monetary and

fiscal policymakers, particularly among the G-20 economies. By the time of the April 2009 G-

20 Leaders Summit, stimulus packages had been adopted by all G-20 fiscal authorities. In

addition, central banks had slashed interest rates and many had adopted non-conventional

measures to increase liquidity and support domestic demand. At the April Summit, Leaders

pledged to take whatever actions necessary to restore economic growth, lending, and

employment.

By late spring there were signs that these policy measures were stabilizing financial markets and

attenuating the decline in real GDP. In the G-7 countries, real GDP contracted at an annual rate

of 0.4 percent in the second quarter, the smallest decline in a year, and the economies of France,

3

Real GDP data for Saudi Arabia are not available on a quarterly basis.

8

Germany, and Japan expanded slightly. Similarly, in the emerging markets, output either

expanded or declines moderated. Declines in international trade also began to moderate in the

second quarter, with some recovery by the end of the quarter.

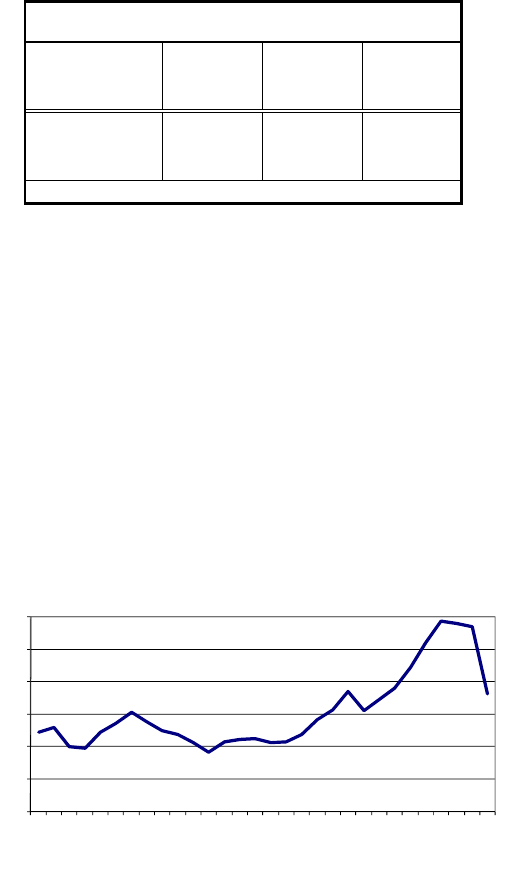

The success of global policy efforts can be seen

in the upward revisions in growth forecasts.

The contraction in the global economy in 2009

is now expected to be less severe than the

International Monetary Fund (IMF) forecast

earlier in the year, and a stronger bounce back

is expected in 2010, according to the latest IMF

projections. Nevertheless, growth in both the

advanced and emerging market economies is expected to remain below pre-crisis norms, with

large output gaps. Given the continuing economic weakness and risks to a sustained recovery,

G-20 leaders agreed at the Pittsburgh Summit in September 2009 that it was too early to remove

the policy stimulus. At the same time, they agreed that developing a transparent and credible

exit strategy was necessary, recognizing that the timing of the exits would differ across countries

and policy measures.

Global Output

(

percen

t

c

h

ange

)

World

Advanced

Economies

Emerging &

Developing

Economies

forecast 2009 -1.1 -3.4 1.7

forecast 2010 3.1 1.3 5.1

Average 2002-07 4.4 2.5 7.0

Source: IMF, World Economic Outlook, October 2009

Looking forward, Leaders of the G-20 established a new framework for more balanced and

sustainable growth. Under this framework, G-20 countries will work together to ensure that their

individual policies are collectively consistent with more sustainable and balanced trajectories of

demand, debt, reserve, and credit growth. To reduce the likelihood of future crises, the G-20 will

establish a process of mutual assessment to help evaluate the sustainability of policies and

develop corrective actions where necessary.

Shifts in global demand are already

underway. Global imbalances declined from

5.9 percent of world GDP in 2006 to an

estimated 3.6 percent in 2009. The global

crisis and associated drop in international

trade is at least partly responsible for the

decline in imbalances but some structural

changes appear to be underway. For

example, in some countries, notably the

United States, the crisis may have resulted in

a structural rise in private saving. As the economic recovery becomes established, fiscal

stimulus will need to be unwound and public saving should be increased. As was acknowledged

by Leaders at the Pittsburgh Summit, to sustain a strong recovery, this necessary rise in public

saving will need to be accompanied by an offsetting rise in domestic demand in other countries.

Otherwise, global growth will remain unacceptably low and the adjustment of current account

imbalances could stall.

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

1980

1982

1984

1986

1988

1990

1992

1994

1996

1998

2000

2002

2004

2006

2008

Source: IMF, WEO Database October 2009

Global Imbalances

(absolute sum of current account balances, as a percent of global GDP)

U.S. International Accounts

The U.S. current account deficit narrowed sharply to $203.3 billion in the first half of 2009 from

$339.1 billion in the second half of 2008, a decrease of 40 percent. In the second quarter of

2009, the current account deficit narrowed to $98.8 billion (2.8 percent of GDP). This is the

9

smallest deficit since the fourth quarter of 2001 in dollar terms and the smallest deficit as a share

of GDP in a decade. U.S. merchandise exports decreased 21 percent in the first half of 2009

from the second half of 2008 and service exports fell 11 percent. However, imports fell more

sharply—merchandise imports declined 26 percent, and service imports fell 12 percent.

U.S. Balance of Payments and Trade

($ billions, seasonally adjusted unless otherwise indicated)

2006 2007 2008 2008 2008 2009 2009

Q3 Q4 Q1 Q2

Current Account:

Balance on Goods -847.3 -831.0 -840.3 -221.1 -178.8 -124.0 -115.5

Balance on Services 86.9 129.6 144.3 35.1 34.3 31.6 32.5

Balance on Income 1/ 48.1 90.8 118.2 34.1 21.1 18.3 16.4

Net Unilateral Current Transfers -91.3 -116.0 -128.4 -32.4 -31.5 -30.3 -32.2

Balance on Current Account -803.5 -726.6 -706.1 -184.2 -154.9 -104.5 -98.8

Balance on Current Account as % of GDP -6.1 -5.3 -4.9 -5.1 -4.3 -3.0 -2.8

Major Capital Flow Components

(financial inflow +)

Net Bank Flows -40.1 -134.8 106.8 22.8 258.7 -253.2 -178.8

Net Direct Investment Flows -1.8 -122.8 -12.3 8.6 12.3 -16.4 -18.7

Net Securities Sales 724.9 661.8 791.7 166.7 242.8 93.4 20.7

Net Liabilities to Unaffiliated Foreigners by Non-banking Concerns 63.5 161.2 327.1 163.8 -36.1 9.2 43.4

Memoranda:

Statistical Discrepancy -1.7 64.9 200.1 38.1 67.2 69.8 41.2

Change in Foreign Official Assets in the United States 487.9 480.9 487.0 115.6 -16.0 70.9 125.0

Trade in Goods

Balance -828.0 -808.8 -816.2 -214.9 -174.0 -120.2 -111.8

Total Exports 1026.0 1148.2 1287.4 340.7 293.3 252.0 248.9

of Which:

Agricultural Products 66.0 84.3 108.3 28.9 23.3 21.6 23.7

Capital Goods Ex Autos 404.0 433.0 457.7 118.1 109.0 98.4 93.3

Automotive Products 107.3 121.3 121.5 31.9 27.3 17.5 16.7

Consumer Goods Ex Autos and Food 129.1 146.0 161.3 41.9 39.0 36.5 36.0

Industrial Supplies and Materials 2/ 276.0 316.4 388.0 107.2 82.2 66.8 68.7

Total Imports 1853.9 1957.0 2103.6 555.5 467.3 372.2 360.7

of Which

Petroleum and Products 602.0 634.7 779.5 130.8 85.4 52.2 56.9

Capital Goods ex Autos 418.3 444.5 453.7 115.2 106.7 91.6 86.4

Automotive Products 256.6 259.2 233.8 58.1 49.9 32.3 31.7

Consumer Goods Ex Autos and Food 442.6 474.6 481.6 123.0 114.1 105.9 104.8

1/ Including compensation of employees

2/ Including petroleum and petroleum products

Source: BEA, Bureau of Census

Net International Investment Position

U.S. net international indebtedness, as measured by the

Net International Investment Position (NIIP), widened to

$3.47 trillion at the end of 2008 from $2.14 trillion at the

end of 2007, when valuing direct investment at the current

cost of tangible assets. The value of U.S. assets held

abroad rose to $19.9 trillion in 2008 while the value of

foreign held assets in the U.S. increased to $23.4 trillion.

As a share of GDP, net indebtedness rose to 24.3 percent

in 2008, from 15.5 in 2007. If direct investment is valued

at the market value of owner’s equity, net indebtedness

widened to $4.0 trillion (28.1 percent of GDP) from $1

trillion (10.9 percen

U.S.NetInternationalInvestmentPosition

($trillions)

2007

2008

U.S.‐ownedass etsabroad 18.28 19.89

Offi c i a la s s ets 0.37 0.92

Privateass ets 15.35 12.35

DirectInvestment 3.45 3.70

For eignSecuri ti es 6.84 4.24

For eign‐ownedassetsintheU.S. 20.42 23.36

Offi c i a la s s ets 3.40 3.87

U.S.governme ntsec urities 2.54 3.23

U.S.Treasurys ecuri ties 1.74 2.33

Othera s s ets 14.53 13.02

U.S.Treasurya s s ets 0.64 0.88

Netinternationalposition ‐2.14 ‐3.47

perc entofGDP ‐15.50 ‐24.30

.5

t of GDP).

10

Net financial flows and price and exchange rate adjustments each contributed to the widening of

the NIIP.

4

Net financial flows increased net indebtedness by $0.5 trillion, as net foreign

acquisitions of U.S. financial assets exceeded net U.S. acquisitions of overseas assets. Most of

the increase in net indebtedness resulted from price and exchange rate adjustments. Price

declines of U.S.-held foreign assets outpaced declines of foreign-held U.S. assets by $0.7 trillion,

and the appreciation of the dollar in 2008 lowered the dollar value of U.S. assets abroad by $0.6

trillion.

The Dollar in Foreign Exchange Markets

For much of the first half of 2009 and into the third quarter, the near-term direction of the dollar

tended to be inversely correlated with market perceptions of financial and economic risk. The

dollar appreciated when risk aversion increased and depreciated when risk appetite increased.

Recently, however, this inverse correlation between the dollar and risk has become less clear, as

market participants have focused more on relative returns on U.S. and foreign assets.

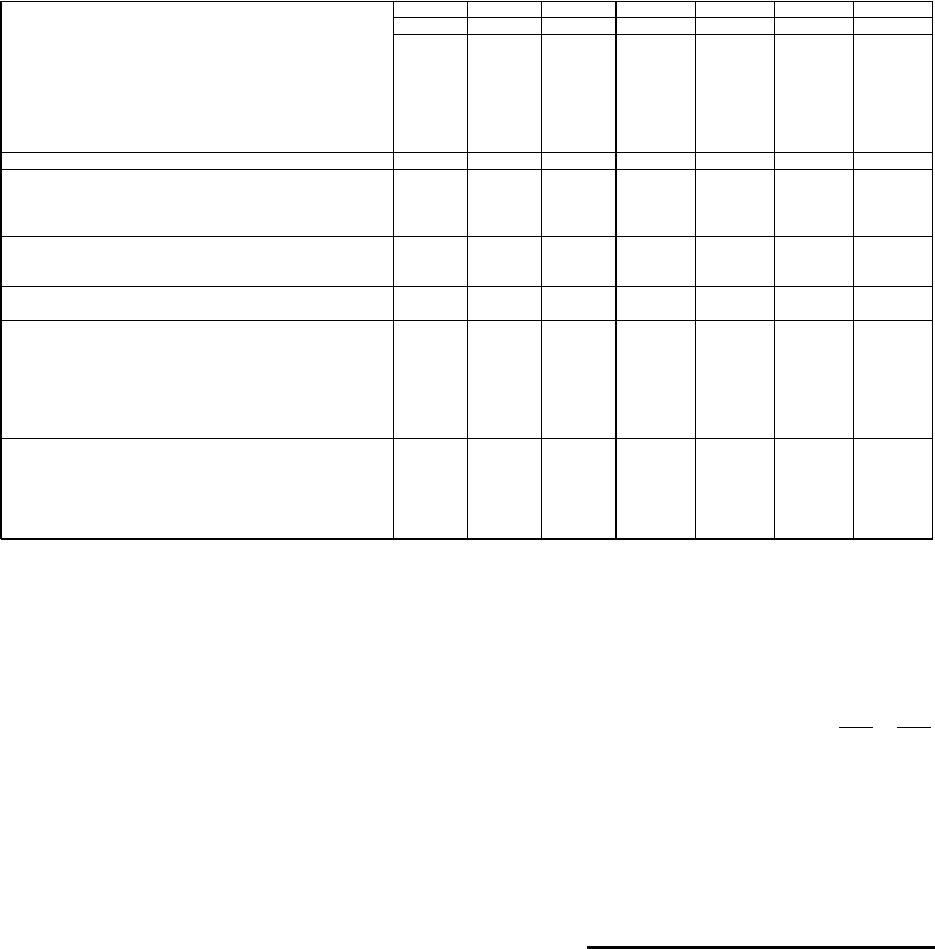

On a real effective basis, the dollar

rose by 3.5 percent in the first two

months of the year, against a broad

group of currencies, but has since

declined and at the end of September

had depreciated by 4.0 percent since

the end of 2008. Against the “major

currencies” the dollar has

depreciated by 6.3 percent in 2009

and by 1.7 percent against the

currencies of “other important

trading partners” (OITP).

60

70

80

90

100

110

Feb-02

Aug-02

Feb-03

Aug-03

Feb-04

Aug-04

Feb-05

Aug-05

Feb-06

Aug-06

Feb-07

Aug-07

Feb-08

Aug-08

Feb-09

Aug-09

Source: Federal Reserve Board

Real Effective Exchange Rate of the U.S. Dollar

February 2002 = 100

OITP

Broad

Major

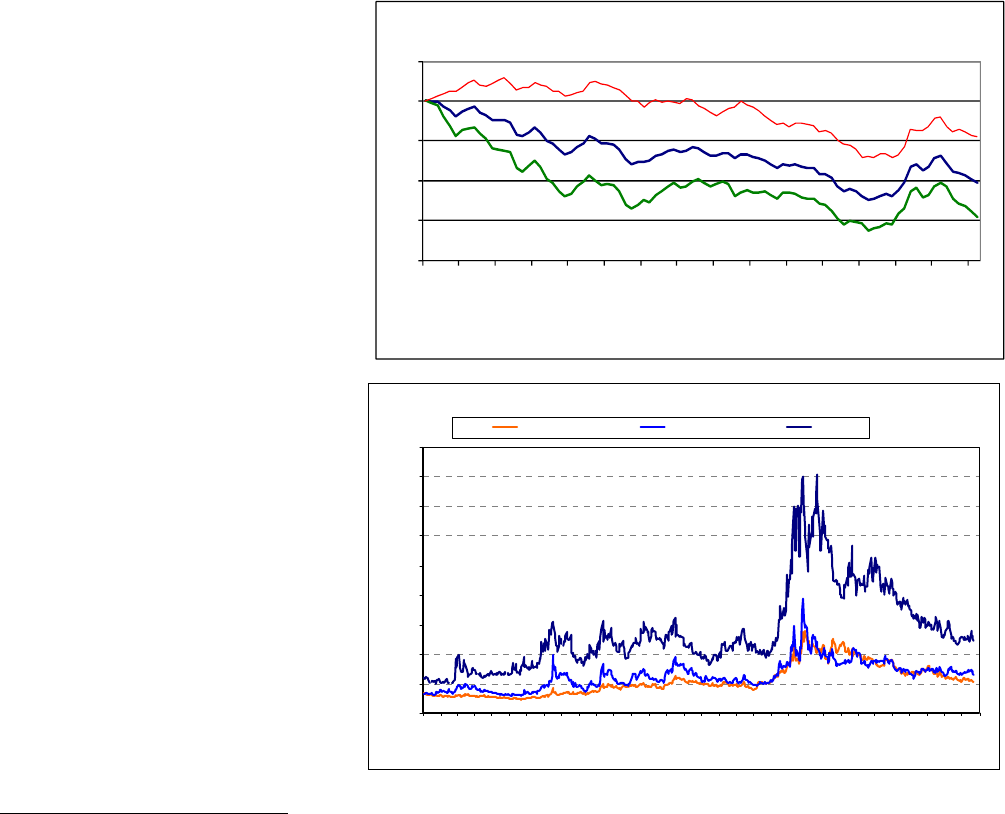

Early in 2009, there was strong

demand for dollars amid the

extreme risk aversion resulting

from the breakdown of money and

credit markets and the spike in

asset and currency market volatility

in late 2008. This included “safe

haven” buying of Treasuries by

global investors and repatriation

flows by U.S. investors. These

flows have slowed as money and

credit market conditions have

settled and volatilities have moved

closer to historically normal levels.

Options Implied Volatilities: Euro/Dollar, Dollar/Yen, U.S. Stocks

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

Jan-07

Feb-07

Mar-07

Apr-07

May-07

Jun-07

Jul-07

Aug-07

Sep-07

Oct-07

Nov-07

Dec-07

Jan-08

Feb-08

Mar-08

Apr-08

May-08

Jun-08

Jul-08

Aug-08

Sep-08

Oct-08

Nov-08

Dec-08

Jan-09

Feb-09

Mar-09

Apr-09

May-09

Jun-09

Jul-09

Aug-09

Percent

EURUSD USDJPY VIX

4

The NIIP is a measure of the stock of U.S. holdings of foreign assets minus the stock of foreign holdings of U.S.

assets (U.S. liabilities to foreigners). For this reason, changes in the valuation of these asset stocks can cause large

year to year fluctuations, particularly when valued at current market prices.

11

In March, policy changes by major central banks and governments – including non-conventional

monetary policy measures – alleviated market concerns about downside risks to the global

financial system and world economy. The moderation in downside risks prompted global

investors to re-allocate out of dollar assets amid a sustained recovery in asset markets. Major

global asset market indicators have now returned to levels not seen since Lehman declared

bankruptcy in September 2008.

Confidence was reinforced in the second quarter on a number of fronts. The April G-20 Leaders

Summit alleviated concerns about emerging markets, especially in Eastern Europe, and global

trade. Global investors increasingly sought exposure to growth, trade, and commodities as

economic data in both the advanced and emerging markets showed improvement. China’s fiscal

stimulus initiatives were seen as critical to the outlook for global growth and commodities

demand. U.S. financial sector earnings reports for the first quarter came in better than expected.

U.S. bank “stress tests” were a key marker of progress in the financial market recovery process

and were followed by increased capital raising by banks, issuance of non-guaranteed debt, and

repayment of TARP loans by some recipients.

Analysis of Individual Economies

Asia

China

The fall in global demand brought China's growth to a halt in the fourth quarter of 2008, but a

timely and aggressive fiscal and monetary policy stimulus has resulted in a strong domestic

economic recovery and a decline in its current account surplus, and as a result contributed

significantly to the recovery in global demand. Real GDP rose by 7.1 percent on a year-over-

year basis in the first half of 2009, as fixed investment and consumption contributed 6.2

percentage points and 3.8 percentage points to growth, respectively. Reflecting the decline in

China’s trade surplus, net exports in the first half of 2009 subtracted 2.9 percentage points from

growth. China does not publish quarterly output data, but private analysts estimate that output

rose between an annual rate of 4 and 6 percent in the first quarter, and between 15 and 19 percent

in the second quarter. In October, the IMF forecast that real GDP would increase by 8.5 percent

in 2009, up from its April forecast of 6.5 percent growth. The IMF is forecasting that in 2010

China’s economy will grow 9.0 percent and account for 28 percent of the anticipated 3.1 percent

pace of total global growth.

As global demand dried up in the fourth quarter of 2008, China’s exports plummeted. Exports

fell by 31 percent between the third quarter of 2008 and the first quarter of 2009, while imports

fell 30 percent. In the second quarter of 2009, imports recovered strongly on the back of China’s

economic stimulus; however, exports increased only slightly. As a result, China's trade surplus

narrowed to a three-year low of $35 billion (3.2 percent of GDP) in the second quarter. China's

current account surplus, though still large, narrowed to 6.7 percent of GDP in the first half of

2009, from an 11 percent high in 2007. China’s trade surplus with the United States fell to $103

billion in the first half of 2009, down from 13 percent from the first half of 2008.

New details on China’s fiscal stimulus program, originally announced in November 2008, were

provided by Chinese authorities in the first half of 2009. The draft 2009 budget, issued at

China’s National People’s Congress (NPC) annual meeting in March, indicates that new central

12

government spending will be $172 billion (3.9 percent of annual GDP) spread over two years.

This is less than one third of the two-year $590 billion fixed investment component of China’s

stimulus, which means that most of the funding for public fixed investment is being provided by

financial sector lending and local governments. Private analysts expect China’s budget deficit to

rise to 4 percent of GDP in 2009 compared to a 0.5 percent deficit in 2008.

In response to the slowdown in growth and the decline in inflationary pressures, Chinese

authorities loosened monetary policy significantly. At the end of 2008, the People's Bank of

China (PBOC) lowered the 1-year bank lending rate by 216 basis points to 5.3 percent lowered

reserve requirements for large banks by 200 basis points to 15.5 percent, reduced the amount of

outstanding central bank bonds, and lowered the interest paid on excess reserves.. Interest rates

and reserve requirements have remained at these levels through September 2009. Most

importantly, in conjunction with these efforts to increase liquidity in the banking system, the

PBOC lifted quantitative caps on bank lending towards the end of 2008, resulting in

extraordinary growth in new bank loans.

5

In the first half of 2009, banks issued $1.1 trillion in

new loans, equaling 35 percent of first half GDP, and more than triple the amount of new loans

in the first half of 2008. A significant proportion of these loans are believed to have gone to the

infrastructure projects promoted by China’s stimulus plan.

More recently, China’s banking regulators have become concerned that rapid loan growth was

resulting in a deterioration of lending standards and have taken steps to increase banks’

provisions for bad loans. In July and August, new loans fell to $355 and $410 billion

respectively, much lower than monthly average of $1.2 trillion in the first half of 2009. The

PBOC has also taken steps to dampen liquidity growth in the inter-bank market by raising rates

on its PBOC bills and repurchase agreements. Nevertheless, its stated goal remains to adhere to

a “moderately loose monetary policy.”

Officially, China operates a “managed floating exchange rate regime based on market supply and

demand with reference to a basket of currencies.” In the summer of 2008, however, China

returned to a policy of maintaining a largely-stable renminbi-dollar exchange rate. Because the

renminbi has remained stable against the U.S. dollar in 2009, it has followed the movement of

the dollar against other currencies. According to the index of the Bank for International

Settlements (BIS), China’s real effective exchange rate appreciated 13.3 percent between June

2008 and February 2009, but it has depreciated on a real effective basis by 6.9 percent between

February and August 2009. Since the end of the dollar peg in July 2005, the renminbi has

appreciated a cumulative 21.2 percent against the dollar and 15.7 percent on a real effective

basis, based on the BIS measure.

In its 2008 annual report issued in August 2009, the PBOC reiterated its commitment to

exchange rate reform, noting that it “will closely watch the movement in the exchange rates of

the major currencies in the international market, and, following the principle of ‘self-initiated,

controllable, and gradual’ to improve the formation mechanism of the RMB exchange rate, make

the exchange rate more flexible, and keep it basically stable at an adaptive and equilibrium

level.” In the report, the PBOC also reiterated its two long-term goals of developing the foreign

exchange market and creating new exchange rate risk management instruments.

5

Credit quotas remain one of China’s most effective tools for curbing lending growth and monetary expansion.

Periods in which credit quotas are imposed usually result in a backlog of projects seeking financing.

13

China’s leadership has also shown a greater commitment to interest rate liberalization and at the

first U.S.-China Strategic and Economic Dialogue agreed to promote this in the future. The

PBOC annual report notes it “will accelerate the establishment of the benchmark interest rate

system in the money market, improve the central bank interest rate system, enhance the pricing

capabilities and expertise of financial institutions, and give greater play to the market in

determining interest rate levels.” Interest rate liberalization will improve resource allocation,

enhance the effectiveness of monetary policy as a market-oriented means of managing economic

activity, and increase the growth of household incomes.

China has taken several steps in the reporting period towards greater capital account

liberalization. First, the PBOC has implemented two pilot programs that allow corporations to

settle their foreign trade in renminbi.

6

Second, the PBOC has signed six bilateral currency swap

agreements with other central banks totaling RMB650 billion ($95 billion).

7

Third, since May

2009, several Hong Kong-funded banks within China have won approval to issue renminbi-

denominated bonds in Hong Kong. China’s Ministry of Finance also launched its first renminbi-

denominated sovereign bond sale outside the mainland in late September, issuing $879 million in

bonds in Hong Kong. Finally, the PBOC currently is exploring allowing domestic companies to

lend funds to their foreign subsidiaries without seeking approval from Chinese authorities. At

the first S&ED China agreed to further reduce capital controls by accelerating the allocation of

quotas for Qualified Foreign Institutional Investors, which allow non-residents to invest in

China’s capital markets.

The stability of the renminbi against the dollar over the past year, the real effective depreciation

that has taken place during the reporting period, continuing productivity growth in the Chinese

economy, and the acceleration of foreign reserve accumulation this year all suggest that the

renminbi remains undervalued. China currently holds $2.1 trillion worth of foreign reserves,

equivalent to 49 percent of its 2008 GDP or over two years of imports. In the first half of 2009,

China’s reserve assets increased by $186 billion.

Renminbi adjustment alone, however, will not be sufficient to reduce materially China’s current

account surplus or achieve more balanced, sustained Chinese growth. For this, China must

continue to reform its development strategy away from export and investment-led growth.

Chinese authorities have stated that they recognize the need to address the imbalances in the

domestic economy and have made “rebalancing” growth a key feature of China’s 11th Five-Year

Plan. In its second quarter report the PBOC noted, “w

hile the protracted contraction of external

demand will extend into the medium- and long-term period, the fundamental way to achieve sound

and relatively rapid economic development is to accelerate reform and restructuring programs, with a

priority on boosting consumption and domestic demand.”

While some progress has been made,

household consumption growth remains near or below the growth rate of GDP. As a result, the

share of household consumption in GDP declined from a recent peak of 46.4 percent in 2000 to

6

The first program allows corporations in the Yangtze River Delta and Guangdong to settle their trade in renminbi

with Hong Kong and Macao, while the second program allows corporations in Yunnan and Guangxi provinces to

settle trade in renminbi with ASEAN countries.

7

An official PBOC announcement on March 31 suggests that the new swap agreements allow firms in participating

countries to use renminbi to directly purchase Chinese imports. Unlike U.S. dollar swaps, governments cannot use

the renminbi swaps to engage in exchange rate intervention because the renminbi is not fully convertible. Nor can

recipient central banks exchange the renminbi received for China’s dollar holdings, according to the terms of the

swap. There is no evidence that any central bank has drawn on the swap lines.

14

35.3 percent in 2008, well below average for an economy of China’s income level. The low

share of consumption reflects a weak social safety net, demographic trends, and the limited

availability of financial services to households, including ceilings on bank deposit rates.

Shifting China’s growth to a more sustainable, consumption driven path will require policy

measures of a scale sufficient to bring about marked changes in the pattern of saving and

investment. A key element of this effort is the provision of better social services and a stronger

social safety net to reduce Chinese households’ need for precautionary savings. China has

recently taken important steps in this direction, including the announcement of a $124 billion

plan to extend basic health care coverage to most of the population by 2011. China also revised

the allocation of its fiscal stimulus in April, redirecting $63 billion (about 11 percent of the

stimulus package) from transportation and infrastructure investment and environmental

protection to low income housing, health, education, and technology innovation.

Corporate saving has risen rapidly over the last couple of years and now is the largest component

of China’s national saving. High corporate saving reflects a number of factors, including the

growing profitability of Chinese enterprises in recent years, low inflation-adjusted interest rates

and the cost of land and other inputs, and low dividend payouts from state-owned enterprises

(SOEs). China has begun collecting dividends from a portion of SOEs under a trial program that

started in late 2007, but at 5 to 10 percent of after-tax profits, the dividends remain low by

international standards. There are reports that the government is considering broadening the

dividend collection program to include more SOEs and increasing the level of dividends that

SOEs are required to pay. This would help reduce corporate savings if these additional resources

were transferred to households or invested in the social safety net, instead of being held or

reinvested in the enterprise sector.

As China’s recovery strengthens, moving to a more flexible exchange rate will give monetary

authorities greater scope to maintain price stability, particularly as China reduces capital controls

to promote greater international use of the RMB. In addition, greater exchange rate flexibility

will complement other structural reforms in promoting consumption-led growth by inducing

greater investment in services and other sectors more oriented towards China’s domestic market.

In the first Strategic and Economic Dialogue (S&ED) between the United States and China, held

in Washington DC in July 2009, both countries agreed to “

pursue policies of adjusting domestic

demand and relative prices to lead to more sustainable and balanced trade and growth.”

China also

agreed that it will continue to “implement structural and macroeconomic policies to stimulate

domestic demand and increase the contribution of consumption to GDP growth; further enhance

access in its service market and expand areas and channels for non-government investment, with

a view to expedite the development of its services industry and increase the share of services in

GDP. China committed to deepening further reform of its social safety nets, including

strengthening its basic old-age insurance system and enterprise annuities which should reduce

excess saving. The next S&ED will be held in China in the summer of 2010.

India

India’s economy is less exposed to the international economy than many other emerging

markets, and this has reduced the effect of the crisis on the Indian economy. Exports are a

15

smaller share of output than in most Asian economies and controls on capital flows are greater.

Nevertheless, the crisis has lowered economic growth. After exceeding 9 percent growth for

three years, growth slowed to 7.4 percent in 2008, reaching a low of 3.5 percent on an annualized

basis in the fourth quarter. Growth rebounded to 6.6 and 7.2 percent in the first and second

quarters of 2009, respectively, but the IMF expects the economy to grow by 5.4 percent this year

as lower demand and weak credit conditions are compounded by a poor monsoon season.

India has used both monetary and fiscal policy to stimulate the economy. The Reserve Bank of

India (RBI) reduced its repurchase rate by 425 basis points to 4.75 percent between October

2008 and April 2009. The reverse repurchase rate was cut by 275 basis points to 3.25 percent

and, the cash reserve ratio for banks was lowered by 400 basis points to 5.0 percent.

Fiscal stimulus measures, estimated by the IMF at around 0.6 percent of GDP, were announced

in early 2009. The package includes measures to boost consumption and investment in

infrastructure and to promote exports. India has limited room for additional fiscal stimulus. The

FY 2008/09 (April to March) consolidated fiscal deficit was 11.4 percent of GDP and public debt

is 80 percent of GDP.

Following an expansion of the current account deficit for much of 2008, the deficit narrowed to

1.5 percent of GDP in the first quarter of 2009, as imports fell by twice the rate of decline in

exports. In the second quarter, a rebound in trade flows resulted in a rise in the merchandise

trade deficit but a rising surplus in trade in services and increases in transfer payments resulted in

a further reduction in the current account deficit to 0.9 percent of GDP. The U.S. bilateral trade

deficit with India narrowed to $2.6 billion in the first half of 2009, from $4.7 billion in the first

half of 2008, as U.S. imports from India fell sharply.

India’s official exchange rate arrangement is a managed float, and the rupee moved in both

directions during 2009. The rupee appreciated by 1.8 percent against the dollar in the first half

of 2009 but the exchange rate was unchanged in the third quarter. On a real effective basis, the

rupee depreciated by 0.3 percent in the first half of 2009, but was down 3.2 percent for the year

through September. Foreign currency reserves, after falling by $56 billion in the second half of

2008 rose by $7.5 billion in the first half of 2009 to $254.1 billion.

The stated aim of foreign exchange intervention is to smooth volatility. While the RBI seeks to

achieve its monetary objectives of price stability and well-anchored inflation expectations by

adjusting market liquidity through its policy rates and the cash reserve ratio, at times, it has used

the exchange rate to help meet monetary objectives.

Japan

Despite the relative insulation of Japan’s financial system from the global financial turmoil, the

crisis has resulted in the most severe recession in Japan's post-war history, lasting four

consecutive quarters and amounting to a cumulative 8.7 percent decline in output. Japan has

been particularly vulnerable to the global economic downturn due to the large share of

manufacturing in GDP and its high dependence on exports (notably autos and electronics) for

growth. Real exports fell by 64 percent in the first quarter of 2009, compared to the fourth

quarter on an annualized basis. A 28 percent increase in exports in the second quarter, compared

to the first quarter, and fiscal stimulus measures adopted by the Japanese government helped

16

boost real GDP growth to a 2.3 percent annualized rate. The IMF expects real GDP to fall by 5.4

percent in 2009 followed by 1.7 percent growth in 2010.

Continued weak domestic demand resulted in a decline in imports in both the first and second

quarters. Exports fell by more than imports in the first quarter resulting in a trade deficit but the

second quarter increase in exports led to a trade surplus in the second quarter. Japan’s

substantial net income on foreign investment was enough to ensure that its current account

balance remained in surplus, rising from 1.5 percent of GDP in the first quarter of 2009 to 3.1

percent in the second quarter. Japan’s merchandise trade surplus with the United States

decreased from $40 billion in the first half of 2008 to $18 billion in the first half of 2009.

Exports to the United States declined by 42 percent year-over-year in the first half of 2009,

compared to a 25 percent decline in imports from the United States.

Japanese financial markets have improved significantly in the first half of 2009, in parallel with

global financial markets. Japan’s benchmark TOPIX stock price index rose by 10 percent in the

first half of the year, following a 42 percent drop in 2008 (its sharpest one-year percentage drop

in history). Money market and corporate credit conditions also have improved substantially due

to targeted efforts by Japanese authorities and the thawing of international credit markets. The

precipitous drop in equity prices that continued into the first quarter of the year, however, put

significant stress on Japanese banks, due to their sizeable corporate equity holdings, as

internationally active Japanese banks are required to recognize unrealized market losses on their

equity holdings, subtracting from Tier 1 capital. According to the IMF, major Japanese banks

raised over $32 billion in private capital in the first half of 2009 in response to the decline in Tier

1 capital. The share of preferred stock and hybrid instruments in Tier 1 capital remains high,

however, at between 20 and 60 percent, compared to core Tier 1 capital and tangible common

equity. Major Japanese banks maintained a Tier 1 capital ratio near 7.7 percent during fiscal

year 2008 (April 2008-March 2009).

Japanese authorities have responded to the financial crisis with a variety of fiscal, monetary, and

financial policy measures. On the fiscal side, the government announced a fourth stimulus

package in April 2009, following three separate stimulus packages in 2008. The IMF expects the

April package to add approximately 2.0 percentage points to GDP over the next two years, and

expects the cumulative impact of the fiscal packages on output in 2009 and 2010 to be equivalent

to 1.8 percent and 1.0 percent of GDP, respectively. The consolidated fiscal deficit is projected

to widen from 3.3 percent of GDP in fiscal year 2007 to about 12 percent in fiscal year 2009 as a

result of increased spending measures and a fall in government revenue.

On the monetary side, the Bank of Japan (BOJ) has maintained an accommodative policy stance

by keeping its policy rate (the uncollateralized overnight call rate) at 0.1 percent. Japan slipped

back into deflation in early 2009. In August, headline consumer prices fell 2.4 percent year-

over-year, the fastest pace of decline on record. Core prices (excluding perishable foods and

energy) were down 0.9 percent in August.

The BOJ also has promoted financial market stability and improved corporate financing

conditions by continuing to accept a broad range of collateral in its discount operations;

increasing the amount of its Japanese government bond purchases; buying outright commercial

paper, asset-backed commercial paper, corporate bonds, and stocks held by banks; and creating a

facility to provide subordinated loans to banks as Tier 2 regulatory capital. In addition, the BOJ

17

and the Federal Reserve have extended an unlimited dollar liquidity swap line until February

2010. The government and regulatory authorities have also continued to provide support to the

financial sector by increasing public funds available for bank recapitalization (about $120

billion); allocating funds to purchase corporate equities from banks (up to $200 billion);

adjusting the capital adequacy calculation methodologies for banks; and easing mark-to-market

accounting rules in measurement and classification.

Japan maintains a floating exchange rate regime and Japanese authorities have not intervened in

the foreign exchange market since March 2004.

Japan’s foreign exchange reserves fell by 1.5

percent in the first half of 2009 to $988 billion as a result of lower interest earnings and valuation

changes on existing reserve holdings.

The Japanese yen appreciated against the dollar in the last half of 2008 continuing through

January 2009. The yen depreciated by 14 percent between mid-January and mid-April, but has

moved upward since then. In the first half of 2009, the yen depreciated by 6.2 percent against

the dollar, but is up 1.1 percent for 2009 through September. On a real effective basis, the yen

depreciated by 11 percent in the first half of 2009. The yen’s depreciation early in the year

reflected Japan’s weak economic outlook and an increase in investors’ risk appetite. Net

outflows of private capital increased in the first half of 2009 to approximately $80 billion from

$69 billion in the second half of 2008.

Malaysia

The Malaysian economy is heavily dependent on exports and was hard hit by the decline in

global demand in the first quarter of 2009. Real GDP fell at an annual rate of 18.3 percent in the

first quarter of 2009, with sharp declines in both exports and domestic demand. In the second

quarter, real GDP rose at an annual rate of 14.1 percent as trade flows rose and policy measures

boosted domestic demand.

Malaysia implemented aggressive fiscal and monetary measures in response to the global crisis.

Last November, it announced a 1 percent of GDP fiscal stimulus plan and, in March 2009, it

announced a second, much larger stimulus plan (8 percent of GDP) to be implemented over 2009

and 2010. On the monetary policy side, the central bank cut its overnight policy rate by 25 basis

in November and a further 125 basis points in two moves in early 2009, bringing the overnight

policy rate to 2.0 percent. Concurrently, reserve requirements were lowered to further improve

liquidity conditions.

In addition, Malaysian officials have implemented proactive policies that have helped the

financial system cope with the global economic slowdown. Among these measures, the

government has implemented blanket guarantees for all ringgit and foreign currency deposits; an

extension of the central bank’s liquidity facility to insurance companies; and a small- and

medium-sized enterprise credit guarantee program. The central bank has also established a

roughly $11 billion bilateral currency swap with the People’s Bank of China.

In April, the government announced plans to liberalize the services sector, including measures

aimed at increasing the share of services in GDP. In addition to its newly promoted service

sector reforms, the government aims to increase openness in the financial sector. This includes

relaxing restrictions on foreign financial institutions allowed to operate in Malaysia, permitting a

18

higher threshold for foreign equity investments in Malaysian banks and insurance companies,

and granting increased operational flexibility to foreign banks. Many of these steps are aimed at

attracting increased foreign direct investment.

Malaysia’s current account surplus has remained above 10 percent of GDP since late 2002, the

reflection of its persistent saving-investment imbalance. Saving in Malaysia remains high, while

investment has yet to recover to its pre-Asian financial crisis peak in 1997. The current account

surplus has not declined during the global economic downturn. In the second quarter of 2009,

Malaysia’s current account surplus was 18.5 percent of GDP. Malaysia’s bilateral trade surplus

with the United States, however, has fallen from $9.5 billion in the first half of 2008 to $5.8

billion in the first half of 2009, as exports to the United States have fallen sharply.

Malaysia ended the ringgit’s fixed exchange rate pegged to the dollar and revalued the currency

in July 2005. It has since maintained a managed floating exchange rate regime. Officially, the

central bank intervenes in both directions to smooth out excessive volatility in the ringgit

exchange rate and has no explicit exchange rate target. After falling by 28 percent during the

second half of 2008, Malaysia’s holding of foreign exchange reserves fell by $404 million, or 1

percent, during the first half of 2009 to $85.3 billion.

The ringgit depreciated by 7.9 percent against the dollar between the end of December 2008 and

mid-March, but has appreciated since then. For 2009, through September the ringgit is roughly

unchanged against the dollar. On a real effective exchange rate basis, based on the BIS index,

the ringgit depreciated 2.4 percent in the first eight months of 2009.

Over the long term, a more flexible exchange rate policy would contribute to more balanced and

stable economic growth in Malaysia by allowing domestic consumption and private investment

to play a greater role in the economy and by enabling the economy to adjust more effectively to

external shocks.

Singapore

Singapore’s highly trade dependent economy (imports and exports represent 350 percent of

GDP) was hit hard by the global crisis. Real GDP declined at an annual rate of 12.2 percent in

the first quarter of 2009, the fourth consecutive quarterly decline, led by declining exports.

There are signs, however, that a recovery is underway. Real GDP rose at an annual rate of 20.7

percent in the second quarter. Merchandise exports, which fell by 46 percent between July 2008

and January 2009, rose by 29 percent between January and August. The IMF is projecting a 3.3

percent decline in real GDP in 2009, but a 4.1 percent increase in real GDP in 2010.

Weak domestic demand and falling commodity prices resulted in a reversal in inflation over the

past year. Prices declined by 0.5 percent in June on a year-over-year basis, down from a 7.6

percent inflation rate in April 2008. The decline in prices moderated to 0.3 percent in August,

but the authorities continue to forecast deflation of between 0 and 1 percent over the near-term.

The government has deployed a range of monetary and fiscal instruments over the first half of

the year to help lessen the impact of the global recession. Following approval of an

expansionary budget in January, the government moved quickly to implement a fiscal stimulus

package. Focused on saving jobs and helping viable businesses stay afloat and increase

19

competitiveness, the stimulus measures are estimated to provide a fiscal impulse of about 3

percent of GDP in 2009-2010. The stimulus measures are expected to increase the fiscal deficit

to 3.5 percent of GDP (the largest in Singapore’s history) in FY2009 (April 2009-March 2010);

because of ample fiscal reserves, however, the government will not need to borrow from the

public.

To promote financial sector stability, in late 2008 the government expanded Singapore’s deposit

guarantee program to cover all Singapore dollar and foreign currency deposits of individual and

non-bank customers until 2010. The central bank also entered into a $30 billion currency swap

arrangement with the Federal Reserve, which was later extended through February 2010.

Singapore has not drawn on the swap line.

Singapore’s banking sector has remained stable throughout the financial crisis, although the

economic slowdown has increased the number of non-performing loans and decreased bank

profits. Nonetheless, overall loan growth has recovered more quickly than in past recessions,

with sizeable increases in May and June.

The Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) manages the Singapore dollar exchange rate

against an undisclosed basket of major trading partner currencies to maintain domestic price

stability, allowing domestic prices to be largely determined by the pass-through of international

prices. In October 2008, MAS shifted from a policy of “modest and gradual” nominal

appreciation of the Singapore dollar against the currency basket to a zero appreciation policy. In

the face of declining exports and a deepening recession, in April the central bank further eased

monetary policy by re-centering the exchange rate band on the prevailing nominal effective

exchange rate (NEER) level, while maintaining the band width and slope (currently at zero

percent appreciation). The move resulted in a devaluation of the Singapore dollar by

approximately 1.5 percent against the currency basket. To reduce pressure for faster

appreciation, the authorities intervene in the foreign exchange market and sterilize the

interventions through foreign exchange swaps, direct borrowing, and repos.

The Singapore dollar depreciated by 1.1 percent against the U.S. dollar in the first half of 2009,

but appreciated by 2.7 percent in the third quarter. On a real effective basis, the Singapore dollar

depreciated by 4.7 percent based on the JP Morgan Real Effective Exchange Rate Index in the

first half of 2009, but depreciated by a lesser 2.8 percent based on the BIS index. Foreign

exchange reserves fell by $2.8 billion in the first half of 2009, to $174.7 billion, but remain

roughly equal to the country’s GDP and short-term debt. These reserve numbers do not include

the government’s substantial stockpile of net fiscal reserves, which are estimated at more than

$200 billion (about 100 percent of GDP).

Singapore’s two sovereign wealth funds, GIC and Temasek, manage the country’s large

accumulation of foreign assets. As of end-August 2009, Temasek managed $134 billion, up

considerably from the $85 billion under management by end-November 2008. GIC discloses

less information about assets and returns, indicating only that the fund manages well in excess of

$100 billion. GIC did disclose a 25 percent loss at the height of the crisis, but has not published

any current statistics.

Singapore’s large current account surplus – the product of a high national saving rate relative to

domestic investment – fell to 9.2 percent of GDP in the first quarter of 2009, before rising to

20

10.5 percent in the second quarter. The current account surplus has fallen substantially from its

28 percent of GDP peak in early 2007. Net capital outflows increased significantly in the first

half of 2009, to nearly 15 percent of GDP (from 6 percent of GDP in 2008).

The United States and Singapore have a free trade agreement, and Singapore typically runs a

bilateral trade deficit with the U.S. Weak domestic demand resulted in declining trade between

the two countries in the first half of 2009, but with U.S. exports to Singapore falling at twice the

rate of U.S. imports from Singapore, Singapore’s trade deficit declined from $6.3 billion in the

first half of 2008 to $3.0 billion in the first half of 2009.

South Korea

After being hard-hit by the global crisis in late 2008, the South Korean economy has recovered

strongly in 2009 as a result of significant domestic economic stimulus and improved terms of

trade. Following an 18.8 percent annualized decline in real GDP in the fourth quarter of 2008,

Korea’s economy expanded by 0.5 percent in the first quarter of 2009, and 11.0 percent in the

second quarter. Growth in the first quarter was driven by net exports and government spending,

while growth in the second quarter was driven by net exports and private consumption. The IMF

has pared its estimate for the 2009 decline in Korean GDP from 4.0 percent, projected in April,

to 1.0 percent, projected in October.

In response to the external shock from the international financial crisis, the Korean government

implemented significant fiscal and monetary stimulus. Korea’s 2009 fiscal stimulus totals 3.8

percent of GDP ($30 billion), one of the largest among G-20 countries. The fiscal stimulus

includes roughly 1.2 percent of GDP in tax cuts and 2.6 percent in new expenditures. On the

monetary side, between September 2008 and February 2009, the Bank of Korea (BOK) reduced

its benchmark interest rate by 325 basis points to 2 percent, the lowest level in over a decade.

From the second quarter of 2008 through the first quarter of 2009, Korea’s merchandise exports

fell by 31 percent, as a result of the sharp drop in global demand. In the second quarter of 2009,

exports expanded 10 percent as global trade flows improved. Korea’s exports to China, which

make up a quarter of its total exports, are recovering strongly, while exports to the United States

and the European Union, which make up 20 percent of exports, continue to be weak. In the first

half of 2009, Korean exports to the United States declined 23 percent from the first half of 2008,

while imports from the United States fell 35 percent. As a result, Korea’s bilateral trade surplus

with the United States increased from $3.7 billion in the first half of 2008 to $5.1 billion in the

first half of 2009.

Korea’s overall nominal trade balance has shifted from a deficit of $1.2 billion in the first half of

2008 to a surplus of $22.1 billion in the first half of 2009. This shift has been driven by a 10

percent improvement in Korea’s terms of trade from end-June 2008 to end-June 2009, and a 22

percent depreciation of the won against the U.S. dollar in the same period. Korea’s current

account, driven by the shift in the trade balance, shifted from a 3.8 percent of GDP deficit in the