DOCUMENT RESUME

ED 355 476

CS 011 223

AUTHOR

Winser, W. N.

TITLE

Fun with Dick and Jane: A Systemic-Functional

Approach to Reading.

PUB DATE

91

NOTE

26p.; Attached material

may not reproduce legibly.

PUB TYPE

Viewpoints (Opinion/Position Papers,

Essays, etc.)

(120)

EDRS PRICE

.MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage,

DESCRIPTORS

Context Effect; Critical Reading;

Elementary

Secondary Education; Foreign Countries;

Language

Role; Models; *Reader Text Relationship; *Reading;

Reading Instruction; *Reading

Processes; Social

influences; *Teacher Role

IDENTIFIERS

*Text Factors

ABSTRACT

Any model of reading must take into

account the role

of the language system in reading. Readers'

subjectivities and the

reading position taken up in

a text can be explicated by

demonstrating how texts function in

context and how readers function

in social situations to construct

possible meanings. Components of

this model include text and context

and their interaction, readers

with their social and cultural capital,

and the language system. The

last element consists of the potential

for meaning that the reader is

both using and building

up. A focus on the system enables the teacher

and learner to clarify the constructedness

of text so as to enable

the reader to deconstruct it and

to accept or resist it. The

teacher's role is to amplify the

context and to make the system

more

visible to readers so

as to scaffold their ability to read

critically. Several texts that illustrate

aspects of the model are

attached. (Contain, 16 references.) (Author/RS)

***********************************************************************

Reproductions supplied by EDRS

are the best that can be made

from the original document.

***********************************************************************

'Fun with Dick and Jane':

a systemic-functional approach to reading.

"PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE

THIS

MATERIAL HAS BEEN

GRANTED BY

TO THE EDUCATIONAL

RESOURCES

INFORMATION CENTER

(ERIC).-

BEST COPY UMW

2

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION

Office of Educational Research and Improvement

EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION

CENTER (ERIC)

1W41"flis document has been reproduced as

received from the person or organization

originating it

Minor changes have been made to improve

reproduction Quality

Points of view or opinions stated in this docu-

ment do not necessarily represent official

OE RI position or policy

1

ng

0

cJ

'Fun with Dick and Jane': a systemic-functional approach to reading.

Bill Winser, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, N.S.W., 2521, Australia.

Abstract: This paper argues that any model of reading must take into account the role of

the language system in reading. Readers' subjectivities and the reading position taken

up in a text can be explicated by demonstrating how texts function in context and how

reader. function in social situations to construct possible meanings. The components of

a reading model are outlined, including text and context and their interaction, readers

with their social and cultural capital, and the language system. The last element consists

of the potential for meaning that the reader is both using and building up. A focus on

the system enables the teacher and learner to clarify the constructedness of text so as to

enable the reader to deconstruct it and to accept or resist it. The teacher's role is to

amplify the context and to make the system more visible to readers so as to scaffold

their ability to read critically.

1. Reading: the need to understand the role of the language system

A reader, like a listener, is faced with the task of constructing meaning from a text. We

might say that the task for both is much the same: the reader has certain resources, the

text has certain characteristics, and both are constrained by and working within a social

context. These are well known factors in the reading process. However, if I had begun

this paper with a statement, such as:

'Buenas tardes, amigos. Como le va?'

you might have had difficulty in constructing much meaning at all, unless you are a

Spanish speaker. The context of this text and your own resources as an English speaker

(with more help from the resources of Italian) may have helped you gain the impression

that I was addressing you as friends (after all 'amigos' is fairly well known). But to get

any fuller meaning you would need to be able to use the resources of the Spanish

language.

These resources are the resources of the language system, the other, less visible

factor in the reading situation. In particular, the language system involves

an

understanding of how the strata of semantics (meaning), lexico-grammar (wording)

and phonology/graphology (sounding) all work together to make the text work. All

reading involves the use of the language system as a crucial aspect of the task, but the

system is often omitted or taken for granted in accounts of reading. One of the great

strengths of a functional educational linguistics has been to draw our attention to this

system and its role in literacy. While psycholinguistic descriptions of reading such as

3

1

2

Goodman's have taken the language system more seriously than most, they have had to

use a formal model of language derived from Chomsky's approach to linguistics,

which focussed on the sentence, using syntax as its basis, and which had

very little to

say about how meaning is constructed in language.

In the psycholinguistic models (e.g. Goodman, Watson & Burke,1987;

Smith,1982) readers are seen as bringing to the reading task their world knowledge and

their language knowledge, both of which are used in reading. These are important

insights, and have advanced our understanding of reading beyond the traditional model

where meaning is something to be extracted from the text. Nevertheless there is

an

assumption that all readings are equally valued and equally significant, with

a sense of

relativity about the feader's 'response' to text. What we now need to be able to show is

how the reader's experience of the world and of language has come about and how

both function in the reading task. While all of our experiences as readers differ, these

experiences are socially constructed and constrained. Further, differences between

individuals can be misleading since our development in a social environment produces

not a set of separated individuals but people whose experience has been similar and

thus results in shared attitudes and knowledges, not totally separate characteristics.

Such shared experience can be seen in people's class, ethnic, age and gender positions.

Finally, we must be able to show how it is that text itself can position

a reader, through

its tendency to appeal to dominant discourses (of class, race, generation and gender)

which conceal their own premises and appeal to the status

quo, the powerful position of

those who control social life. We need to be able to show how texts actually work

to

make meaning, and how readers can be empowered to resist

or, if they decide to do so,

to accept a reading position because they can see that it is in their own interests to do

SO.

If we are to demonstrate how readers' subjectivity is a significant factor in

reading we need to move beyond a psycholinguistic model to

a sociosemiotic approach.

Now that we have available a functional understanding of language that is

seen in the

Hallidayan model, and some insights from semiotics seen from

a poststructuralist

viewpoint, we are able to develop our understanding of the

way readers use language to

make meaning in reading much more easily. In this way it will be possible

to give a

fuller account of the reading process, and to point out the implications for teaching

reading at all levels.

An example of how control of the language system is needed for effective

reading may be seen when we consider the demands made

on readers by texts used in

the sciences, the social sciences and the humanities, and typical of those used

at school.

Martin (1988) has shown that these texts use a 'Secret English'

to get their message

across. By this is meant the marked tendency for written language to rely on features of

3

English grammar that are not at all evident in everyday speech, which in turn

uses the

language of common sense and homely contexts. It is the language of written texts that

readers must learn to use if they are to be effective readers. One example is this sort of

text, a report likely to be used in science, where technical terms predominate (in bold

face):

("Whales"

from J. R. Martin, "Technology, bureaucracy and schooling", Dept of

Linguistics, University of Sydney)

Another example is a text more typical of the social sciences, also a report. Here

technical terms (underlined) also predominate, but there are also many abstract

expressions, also nouns, but nouns used where in everyday discourse we would

use

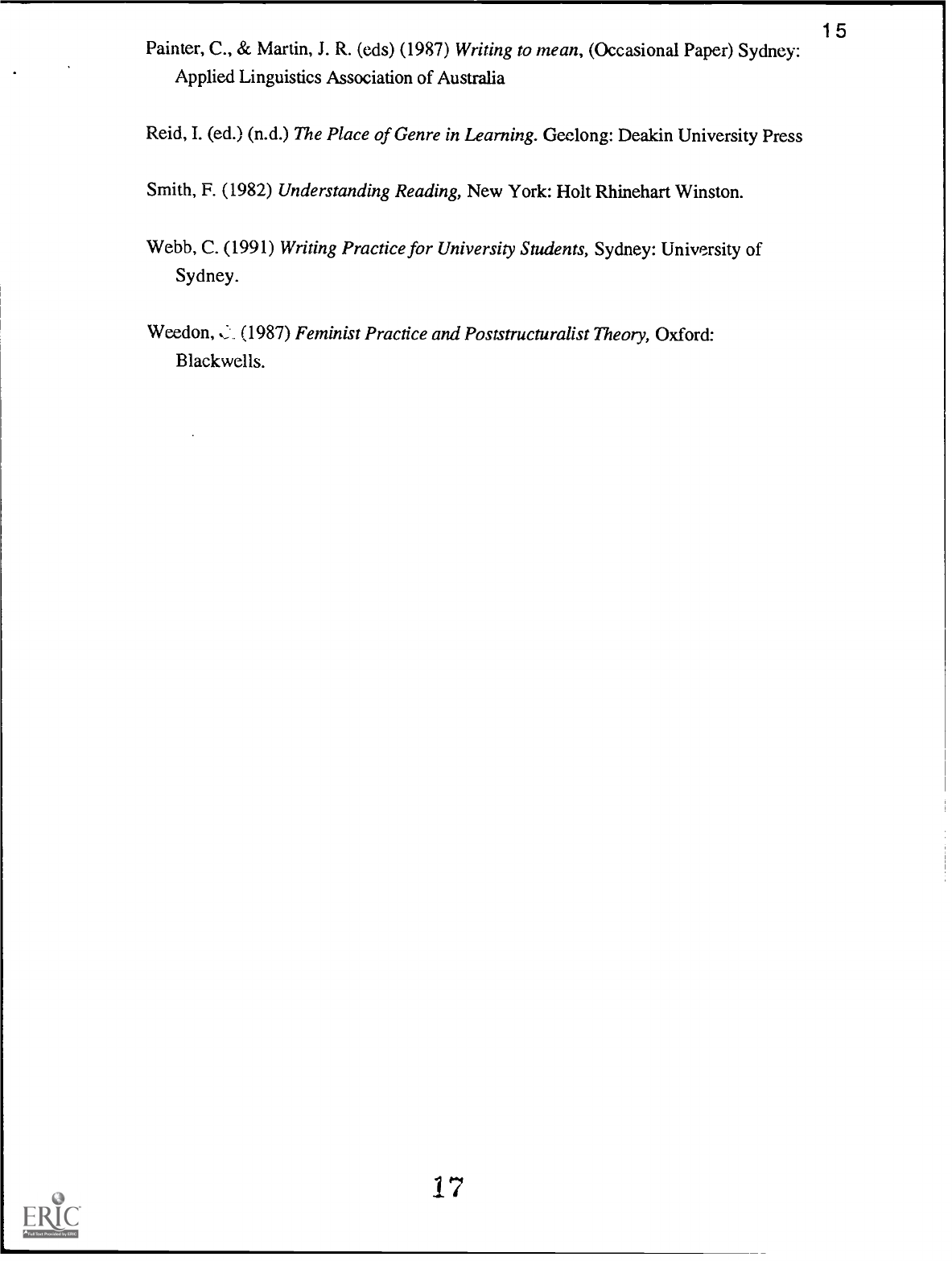

verbs. That is, they are nominalisations (bold face):

(JRM, source as above, "Inflation")

Finally, here is a text that may occur in the humanities, a historic. al recount:

(JRM, source as above, "The breakout")

We will examine how these sorts of texts make specific linguistic demands

on

the reader. We can demonstrate how the essential factors that

are involved in reading

them are fourfold: the reader, text features, social context and the language

system. It

is the recognition and description of how all these four aspects work together in the

reading process, in the practice of reading, that must now be considered

so as to

provide a more adequate model of reading and of English teaching.

2. Traditional or popular approaches to reading

a. Psychological models

Many of these accounts of reading, and particularly of learning to read,

set up

simple models of individual readers and a text, and

assume that authors present an

intended meaning in the text and that the task of the reader is to find

out what these

intentions are. Quite aside from the possible fallacy of assuming that the author has

an

intention, whatever that may be, these models give

very little guidance for teachers in

helping readers negotiate this mysterious pathway. As well, it is quite misleading

to

assume that the reader is an isolated individual unaffected by social factors and that the

text stands alone and is not a product of social and cultural forces.

Other model,; cuggest that reading is very closely related

to listening, and that

the task is to decode the text to sound, 'sounding it out'

so that the reader can 'hear' the

5

4

spoken words which are familiar in everyone's experience and thus construct meaning

directly from the text. This overlooks the essential differences between spoken and

written texts, and the approach is further weakened by the concepts involved in the

activities recommended by adherents of 'phonics', tasks which commonly are not

based on an accurate account of the relationship between sounds and the written text.

b. Literary models

Teachers of older readers often use a model of reading based on studies of

literature and literary theory. A prominent example is the reader- response approach,

and the similar tactical reading model, emphasising the freedom of the reader in making

any response to the text that arises from their own experience. When readings are

related to the needs or concerns of the reader, when it is believed that any reading is

meaningful, then we find that readers at school are likely to be vulnerable because their

reading may not match up with that of teachers (and external examinations). The

pressure to come up with a canonical reading, one that is socially approved in the

school context, or elsewhere, is very evident, although implicit, and it means that only

the students from an enriched background are likely to meet the hidden requirements.

While it is true that every reading of a text must have some validity in

some situation it

is not the case that it will be valid in every situation. Such reading practices conceal the

actual ways in which texts function to make meaning, the very teAtuality of texts which

operates through the genre and the language system.

Thus it is only through an understanding of the role of the language system,

as

well as generic and discursive patternings, that we can help readers

come to terms with

the meaning making practices of texts so that they can then be analysed and critiqued.

Without this understanding readers will passively be positioned by this particular

approach to reading, and thus disempowered when it comes to the ability to

even gain

access to the conventional reading, to say nothing of going beyond it through an

understanding of how alternative, possible readings can be made. (For

a fuller

explanation of this argument, see Anne Cranny-Francis's Narrative

genres: strategies

for resistance and change in this volume.)

Conclusion: some major problem areas in reading beliefs and practice.

Textual and linguistic transparency : both of these approaches, which

seem to

encompass a wide range of teaching practices, take the operation of the language and

social system for granted in reading. They do not give any significant account of how

the language system functions to make meaning in texts, and thus disempower readers

in the task of coming to terms with texts' reading positions and the discourses operating

in them. For readers and their teachers, language is rather like

a pane of glass,

transparent, and therefore not something that is significant in reading practice.

6

5

Individualism: these approaches are unlikely to be able to situate readers and texts in

the social and cultural matrix which provides an essential framework for reading. They

assume that social factors, including ideologies of gender and class, are of minimal

relevance to reading practice. Once again they are not capable of giving

an account of

how texts position readers and of how readers

can become aware of these textual

practices of meaning making.

Meaning making: a feature of these reading pedagogies is that they

assume that

meaning making is an aspect of the task that lies in the hands of the reader alone, often

isolated from the wider socio-cultural environment of both reader and

texts. We tend to

think of meaning as though it is identical to psychologically constructed notions like

'concept' or 'proposition', and that the reader has an individual, personal

store of these

that are brought to the reading task. But, as Weedon (1987, 41) has pointed

out,

'meanings do not exist prior to their articulation in language, and language is always

socially and historically located in discourses'. When we consider meaning making it is

essential to take into account the essentially social nature of the language

system, of

which meaning is a part, and of the fact that language predates and exists in the

culture,

including but going beyond the experience of any individual (although each individual's

texts fractionally contribute to change in the system, over time). The language system,

from a functional and sociosemiotic perspective, has developed

over the millenia in

social situations to allow people to exchange meaning within these social

contexts.

Some recent trends towards individualism and the solitary 'voice' have made

us lose

sight of this essential feature of language.

3. A model of reading that takes functional language seriously

It is now more widely accepted that what is involved in reading is the

construction of meaning from written texts. So it seems that

we could characterise it as

the act of interpretation of text. What is important is to note the

aspects or variables that

need to be described to give an adequate account of it. These

aspects we have seen

include:

Reader

Text

Context

Language

all working to construct meaning.

How are these related? A model that sketches this relationship

may look like

this:

7

6

text <

meaning

> context

language system

Reader

In this framework the interaction between text and context is the means the

reader has, using the language system, for constructing meaning. The reader, of

course, comes to the text with a history and a subject position deriving from experience

of discourses embodied in the experience of other texts, both written and spoken. To

some extent, such a discursive history will be unique for each individual, although

there will be considerable commonality between individuals, and there will be

distinctive positions occupied by groups of readers according to gender, class,

age and

ethnicity.

All texts are constructed in a context and all readers reconstruct texts in

a

context, the context of reconstruction being more or less different according to the

circumstances of the reader. Many readings of literary texts take place in contexts far

removed in time and space from their context of production, and

so readers can only

work from the cues internal to the text to set

up its context. The same applies to many

written texts, because they are bound to be removed from the context of their

production. The essential question is

- what are the features of context that enable a

reader to interpret a text?

There are two aspects of context that must be considered, the broader context

of the culture and the more specific context of situation. The cultural

context, consisting

of the knowledges, values and practices of groups within the society, is the

source of

ideologies and of social and individual purposes that we hold to be important. It is here

that the genres, the purposive patterns of behaviour realised in language,

emerge and

change. This context constrains and affects the numerous and

more specific contexts of

situation which are evident within the broader framework of family life,

at work, in

leisure pursuits and so on. The Hallidayan model of register describes these situations

in terms of three variables, field (what's going on), tenor (who's involved), and mode

(role of language, including channel of communication). All directly affect the

construction of text and its reconstruction in reading.

It can be seen that the reader's task is to reconstruct the context of culture and

situation, using inference and prediction as essential strategies. Other

texts are also part

of the context, as the important notion of 'intertextuality' shows. The

text below is one

from everyday life and is 'read' routinely by

many adults.

6

QBE TEXT

What factors of context are needed to do this? In the culture of western, urban,

industrial democracies car ownership occupies an important part and so social

consequences of car use emerge and become important at the level of protection of

'third parties'. This genre is used in the institution of commerce and in particular in

insurance, and so the structure of this text functions to incorporate the information

needed to effect insurance. In this case the insurer is seeking my business, so includes

the enticement to a discount, but the rest of the text sets out information about the

insurer, the details of my car, and the charge, in a structure that flows from top of page

down. The purpose is to convince me that this insurer is competent to provide what I

need.

At the register level the field is car insurance, for third party injury, as seen in

features like 'premium', 'due date', and 'liable' as well as more complex nominal

groups - 'Compulsory third party personal injury insurance' and 'vehicle registration

certificate'. The tenor is free of affect, being that of authoritative business firm offering

business to a customer, as seen in the declaratives ('is payable', 'takes effect'), while

the mode is written and removed from face to face communication. These features of

the register must be appreciated by the reader if the text is to be understood, and it is

clear that there are many aspects of the culture of commerce and of insurance that it

takes for granted. It is not surprising to note that there are many problems in this text

for young readers and for some adult second language readers, particularly those

unused to urban social life. While an individual reader may lack knowledge of these

aspects of insurance, the knowledges are socially constructed and accessible within our

culture. It is this field knowledge that the reader may need help with, as well as other

register variables, if they are to interpret it properly and be able to use the text

adequately. For a number of examples of texts' register features and how we 'read'

them, see Halliday (1985, p. 170).

The text does not stand alone, however, but comes from a context of its own

and is related to other texts on which it is dependent

- just as one lesson in a sequence

depends for its meaning on the lessons that have gone before it. Anyone who has seen

other insurance documents, perhaps for life insurance, will quickly adapt to this one,

because the other texts are of the same genre and register. This notion of intertextuality

is an indication of the language context of any texts we read. Consider the texts that

are

presupposed by or taken up in the following.

"CHAPTER ONE" Text (from Kress, 1986)

Here we see an example of gendered discourse in a text that is easily recognised

as a Mill and Boon romance . Evidence for this discourse is found in lexical items like

'trim waist', 'embarrassment' and the detailed reference to the nurse's attention to her

9

7

appearance

'hairclip', 'frilly cap' and 'honey-blonde curls'. None of this information

is provided in the case of the male participants in the text, who are presented within the

framework of the intersecting discourse of medicine. The reader must be able to take

into account the other texts that deal with medical practice, often popular ones including

TV soaps, and also texts which present women and men in varying but patterned ways

according to social beliefs (ideologies) about the 'right' types of behaviour for each.

Many of the latter texts will first be encountered by younger readers at school, where it

has been shown (Baker & Freebody, 1989) that very restricted stereotypes of class and

gender are presented.

Once we have understood the role of context in the reconstruction of meaning in

reading, we can then examine some more specific aspects of the language system that

readers use. How does the language work to make meaning, in conjunction with the

information from context? One way of thinking about this is to consider how we read

by working 'top-down' or 'bottom-up'

shuttling between both the top level and the

bottom level. By top level we mean the discourse or whole text level, seeing the text as

a whole, and as the essential semantic unit, within the framework of the broader context

of the culture. Here the work of Martin (e.g. 1985; Reid, n.d.) has been influential,

with its conceptualisation of genre

a social process. By bottom level we refer to the

fundamental grammatical unit, the clause, which functions to make meaning in a

different way. Readers have to shuttle between these two levels constantly as they read

and construct meaning, and it is likely that their ability to do so will contribute

significantly to their reading competence.

Thus at the discourse level a reader will be making judgments about the social

purpose of the text, who would write it and to what end within our culture. Next the

generic structure of the text would come under attention: how does it begin, in what

ways does it develop and how does it end? Relevant issues here include the 'content'

of the subject area, the range of genres that are used and needed at various levels and in

our society, the experience of learners with these different genres, the ideologies

encoded in them, the social power of different genres, and the social background and

range of experience ('subjectivity') of learners.

Read these two texts. What is their purpose and their importance in our culture?

Texts: 'CARS' (From: Webb, 1991)

'WHALES'

They are factual texts, and deal with economic, biological and social issues that are

central in our culture. All of the issues just discussed concerning the top level matters

apply to them.

When we consider the bottom level, at the level of the clause and the

lexicogrammar, we are concerned with the reader's ability to use the subsystems of the

10

8

9

grammar. To summarise these, there would have to be a 'reading' of three major

subsystems of the grammar, each corresponding with the three register variables (field,

tenor and mode) and the three metafunctions or ways of meaning (Ideational

field;

Interpersonal - tenor; Textual mode).

The first, related to field, is the transitivity system, the means provided by the

grammar for the representation of knowledge and our experience of the world. Here we

focus on the participants (nouns and noun phrases), the processes (verbs) and

circumstances (adjuncts, or phrases carrying background information). The second,

related to tenor, is the mood system, our means for constructing dialogue between

writer and reader, with choices between indicative, including declaratives and

interrogative, and imperative. These are likely to vary greatly, from factual texts where

the tenor is almost neutral to those fictional and more personal texts where the

tenor is

strongly displayed. Other resources include matters like degrees of impersonality,

expressed by modality (being tentative or certain) and by modulation (obligation).

Finally there is the system of theme, related to mode, the

means we have for

constructing the message of the text as a whole. The theme is particularly important in

written texts. It is the element that comes first in the clause, its point of departure, from

the writer's point of view. Once the reader has established this starting point they

can

move on to the rest of the clause, the 'news' that the writer Wants to pass on.

In the two factual texts above we can examine these elements of the grammar.

When we consider transitivity, 'car', 'bus', 'travel' and,

more abstractly, 'transport'

seem to be important participants in one text. Processes include 'carry', 'use', 'reduce'

and, less obviously, 'is' and 'are'. In the other text we have items like 'whale', 'fish',

'mammal' and 'plates', the latter being specialist, technical terms that will need careful

explanation by teachers. Processes here include quite regular

use of 'is' and 'are'

('relational' processes), as well as 'can weigh', 'give birth', 'breathes', and 'hang

down'. The relational processes are important because they enable the writer

to present

information economically and to connect items with each other in taxonomic relations

that are so important in science. Sometimes the reader

may not appreciate how these

relations are being constructed and teachers will have to assist them here.

Mood presents quite different challenges to the reader. The

younger reader will

be used to a dialogue where relations are more

more clearly defined by the situation;

when Mum gives an order (imperative) it is obvious that she is

an authority. But in

these factual texts the writer mainly uses declaratives

'is' (a vehicle), 'have' (hair) and

(people) 'drive' (cars). These are authoritative statements made by the knowledgeable

expert writer, who is more distant from the reader than Mum is. Notice also how claims

are modulated: "Cars can usually carry...'.

10

Theme can be examined by marking off and listing the first part of each

clause,

that element before the process (verb). In the 'car'

text these are:

A car, like a bus

cars

Most cars

Many people

Bus travel, by contrast

In Australia, most people

Buses

Buses

As well as buses operated by the government, there

In the other text we have:

"What"

The answer

It

However, when asked [etc]

The blue whale

It

And it

There

What

Well, there

etc

However there are some much longer themes:

Being a mammal also

This fountain of vapour

The second group of whales

Such long themes are typical of technically oriented

texts which pack in 'information by

the use of these long nominal groups (noun phrases).

By examining the themes in this

way we can see how the message of the text is

built up and organised. If we set these against the corresponding

'news' (the rest of the

clause) we can then see very clearly how the

message is being constructed, its

patterning and continuity, and are therefore in

a position to help readers understand the

way these texts mean. In fact, while we have been operating at the bottom level the

process of listing the themes has enabled us to see how the whole

text is making

meaning.

What the reader has to do is to shuttle between these

macro and micro levels so

as to fully understand the text. Certainly the reader will have to be quite proficient

at the

1 2

11

lower level if they are to be able to deal with the broader questions associated with the

discourses at the higher level, but this is not a one way street and there will be

a need to

move between both levels constantly for competence in reading. At the lower level,

beginners (young readers, ESL readers of various ages) will need assistance with

aspects like tense, the article, phrasal verbs, singular/plural patterns and features of

written language like nominalisation and embedding, as well as abstract and technical

discourse.

There is an outcome to all of this discussion. Each text has been written with

a

reader position in mind (Kress, 1985). The propositions put in the text should ideally

be 'read' as obvious, natural, common sense and unproblematic. This is the compliant

pcsition for the reader to adopt. But the reader can resist this desired reading

- if they

know how the text has been constructed to make its message. The following text is

taken from a school textbook:

"ABORIGINALS"

What reading position has been constructed here? Notice how quickly the text

constructs the Aboriginal experience as one of lacking the ability to resist: this was the

problem - for the Aborigines, according to the writer. Aborigines

may not have seen

this as a weakness or a problem, however. Think of the numerous texts students

may

have already read which buttress this point of view, the cotexts that have already

positioned them as readers and predisposing them accept the 'voice' of this text. One of

the most far-reaching tasks of a teacher of reading or of English is to help students learn

to see through the text so as to understand how it has been constructed, and this can

only be done when the reader has been helped to acquire this understanding. Then the

reader will be able to resist, if that is in their best interest.

3. Reading pedagogy

So far we have been sketching out a linguistic model of what is involved in

reading. Here we briefly examine some of the teaching implications of the model. One

important source of guidance here is to be found in the insights gained from social

learning theory and in particular the language development studies of Halliday (1975) in

his book Learning how to mean, and of Painter (1984, 1991), especially the latter's

important article "The role of interaction in learning to speak and learning

to write" in

Painter and Martin (1987). These studies show how the language learner actively

works with more mature models of language, negotiating meaning in

a shared

environment where language and texts are modelled by the adult and jointly constructed

by child and adult.

1 3

12

The role of the teacher may be seen as one of amplifying the context in which

language is being used, equipping the student with an understanding about language

that is functional - of how language works to make meaning, as we have sketched it out

here, with reference to reading. The teacher must scaffold the students learning

activities, supporting their efforts to make meaning from texts by constantly clarifying

the contextual features we have outlined above, relating these to the language system,

and making the language more visible. One important element in this task is developing

a metalanguage, a language about language, so that teacher and student can

communicate readily. There are examples of such a metalanguage in

's paper, and

more systematic statements are to be found in the glossaries of the LERN and DSP

publications (see descriptions in the references).

The curriculum cycle that has been developed in the DSP project (Sydney

Metropolitan East Disadvantaged Schools Program, Erskineville Public School,

Erskineville, Sydney) includes elements concerned with modelling texts, jointly

constructing and individually constructing them. The first two elements are relevant to

reading pedagogy. These are the modelling and joint construction phases. When the

teacher models the text we are using a strategy that is a normal part of language

development, showing the student what is involved in a text's construction

- its

purpose and overall structure in context (our 'top level') and its more specifically

linguistic features (our 'bottom level'). Modelling texts that occur as part of the students

learning activities and that are relevant to their curriculum means a deliberate and

planned focus on the texts features, and perhaps some shuttling between the two levels

we have mentioned. This means that the teacher will have to analyse the texts, then be

prepared to take appropriate opportunities, within the planned activities of the

curriculum (whatever the subject area may be), to discuss and highlight the texts'

features - with individuals in reading conferences, with small groups, and occasionally

with the whole class.

Sometimes modelling will need to be given considerable emphasis in a reading

or English programme, especially when the genres and related language features are

new to the class. At other times brief minilessons are all that is needed.

The other strategy for reading instruction is that of joint construction of the

text's meaning. While modelling involves a fairly teacher oriented lesson,

strong

scaffolding, the activity of joint construction involves mutual, reciprocal activity

on

the part of teacher and students. Here the aim is for both to work at reconstructing

meaning from the text, using the knowledge gained from the modelling activities to

interpret the text and some conclusions about a 'reading'. The teacher's role here is that

of the expert language user, who directly assists the readers with suggestions about

an

interpretation using the top and bottom level features we have discussed. The students

14

13

are expected to use their knowledge of the 'field' of the text ie., its subject matter,

whether factual or fictional, in the joint activity of reconstructing meaning. Together

teacher and learner take this shared responsibility for making meaning. This is a

teaching strategy delicately poised between being too directive and too passive.

To understand some of the issues here the reader could now reexamine any of

the texts discussed here, asking the following questions:

What features of the text/context would you need to model?

What would be likely to come ;'p in a joint reading of this text? Where are the

problem areas in the context/language, as far as your own students are

concerned? What would you be able to expect from them? What would you

have to be ready to explain?

What reader position is called for by the text?

How could learners learn to challenge it?

Any further implications for our understanding of reading and reading

pedagogy?

4. Conclusion

The principles that are important for understanding reading and for teaching

English are far reaching ones, that relate to the types of text read, the sorts of context in

which they are relevant and the language features that are typical of them. Reading is

presented here as an activity that calls on the reader to articulate the factor of language,

context and text in the process of interpreting text. There are many more issues that are

relevant, particularly those concerning younger readers and other beginners; many of

these can be clarified by using linguistic principles. This is particularly the case with the

often vexed question of the relationship between the sound system and the written

system of language. Another aspect we can illuminate is the way in which reading can

be shown to develop over the long term, as the student learns 'how to mean' in more an

more registers associated with the culture and reflected in the curriculum and its

sequencing.

Essentially, however, many of the issues are summed up in the need to see

reading, and the study of English, as an activity where control of the language system

is critical if the reader is to develop into a competent and critical interpreter of the texts

that are used throughout the curriculum.

15

14

References

Baker, C., & Freebody, P. (1989) Children's First School Books,

Oxford:

Blackwell.

DSP: Teaching Factual writing; A brief Introduction to Genre; The Recount, Report,

Discussion Genre; Assessing Writing. Erskineville, N. S. W: Disadvantaged

SchoolsProgram, Metropolitan East (Erskineville Public School, Erskineville, N. S.

W., 2043, Australia)

Goodman, Y., Watson, D., & Burke, C. (1987) Reading Miscue Inventory, New

York: Owen, 2nd edn.

Halliday, M.A.K. (1976) Learning how to mean

,

London: Arnold.

Kress, G. (1985) Linguistic Processes in Sociocultural Practice. Geelong: Deakin

University Press.

Kress, G. (1986) "Reading writing and power", in Painter, C., & Martin, J. R. (eds)

(1987) Writing to mean, (Occasional Paper) Sydney: Applied Linguistics

Association of Australia

LERN: A Genre-based approach to Teaching Writing in

years 3-6; Explain, Argue,

Discuss: writing for essays and exams. Annandale: Common Ground

Publishing.(6A Nelson St., Annandale, 2038)

Martin. J. R. (1985) Factual Writing. Geelong: Deakin University Press.

Martin, J. R. (1988) "Secret English: Discourse Technology in a Junior Secondary

School", in L. Gerot et al., Language and Socialisation: Home and School

,

Sydney: Macquarie University.

Painter, C.(1984) Into the Mother Tongue, London: Arnold.

Painter, C. (1991)Learning the Mother Tongue, Geelong, Vic: Deakin University Press,

2nd edn.

1 6

15

Painter, C., & Martin, J. R. (eds) (1987) Writing to mean, (Occasional Paper) Sydney:

Applied Linguistics Association of Australia

Reid, I. (ed.) (n.d.) The Place of Genre in Learning. Geelong: Deakin University Press

Smith, F. (1982) Understanding Reading, New York: Holt Rhinehart Winston.

Webb, C. (1991) Writing Practice for University Students, Sydney: University of

Sydney.

Weedon, .L (1987) Feminist Practice and Poststructuralist Theory, Oxford:

Blackwells.

17

Whales

There are many species

of whales. They

are convenientl y divided into toothed

and baleen categories

toothed

are found world-wide in great

numbers.

The large f t is the Sperm

whale.

qt-ok,is to about the size of a boxcar.

Other

,:pecies familiar to Canadians

are the Beluga or white whale,

the Nrimehel with

its iinic.orn-like tusk. the

Killer whale or Urea.

the Pilot or Pothead

whale,

c r

i t torrimonlu stranded on beeches.

the Spotted and Spinner

Del phi ns that

.-rate a problem for tuna

stiners, and the Porpoises

which we commonly

see along

our shores

There are fe%....er species of

the larger baleen whel5

that filter

rill and small fish

through their baleen plates.

The lat gest is the Blue

whale which is

seen frequently

thei-mif of St Lawrence. it

r,91:11et, :1 length of 100 feet

and a weight of 200 tone,

equivalent to atout 30 African

elei.Thants. The goung

are 25 feet long at birth and put

on about 200 lbs. a day

on their milk diet. Other species

are: the fins which at a

length of 75 ft. blow spouts

of 20 ft.. the fast

swimming Seia, the Grags

so

comr!..nlu seen on migrations

along our Pacific coast

between Baia California and

the

Bering Sea, the Bow heads

of Alaskan waters. the

Rights, so seriously threatened,

the Humpbacks nioued

bu tourists in such places

as Hat:,tii and Alaska, the

smaller Bryde's whales,

and the smallest Minke

whales, which continue to

be

abundant worldwide.

As with the growing interest

in birding, increasing

numbers of whale watchers

can

distinguish the various species

of wales. 1W R Martin

19891

BEST CM MOLE

18

What is inflation, What

are the causes and consequences of inflation 7.*

What are the policies used to control

inflation?

inflation

is an increase in the general level

of retail prices, as measured

bu the

consumer price index (GPI). The CPI is

determined bgquarterlu

surveys of

prices for a representative

range of goons and services This 'basket' of

goods_

and services was determined

bu the Australian Bureau of Statistics

from an

esti matien of the pattern of

household expenditure in 1984.

The selected goods

and services are divided into eight

groups: food, clothing, health and personal

care, housing, household equipment and

operation, tobacco and alcohol,

recreation and education, and

transportation. Each item is given

a weighting

which reflects the relative importance

of the item in the household budget.

There are a number of factors

which contribute to inflation.

These include demand

pull, wage push, external

causes, inflationaru expectations,

public

sector causes, price shocks and

excess money supplu...

Causes

The causes of inflation

are high consumer demand, cost

push, increase in

money supply, high interest rates,

external factors and government

intervention.

High consumer demand is

.vhen consumers are demanding

at such substantial

levels th::t supplq is not ahle to

respond. An increase in

consumer demand will

result 4r, high prices owing

to a lhortage,in domestic

suppl 0. Therefore demand

over into imports,

.

G

BEST COPY AVAIL LIE

The Breakout: 16 October to

25 November

This most successful phase of the

Long March owes a great deal to the

diplomatic

kiil

of Zhou En lai and to the bravery of

the rearguard.

nowing that the south-west sector of the

encircling arm was manned by

troops from Guangdong provi nce, Zhou began

negotiations with the Guangdong warlord.

hp:.n

tIng. Chen was concerned that

a Guorni Mang victory over the Communists

would enable !:hiang Kaishek to threaten his

own i ndependence. Chen agreed to help the

Communists with communications equipment and

medical supplies and to allow the Red

Army to

pass

through his lines.

Between 21 October and 13 November the Long

Marchers slipped quietly

through the first, second and third lines of the

enci:-cling enemy. Meanwhile the

effective resistance of the tiny rearguard lulled

the Guomi Mang army Into thinking

that they had tr.ipped the entire Communist

army. By the time the Guomindang leaders

realized what was happening, the Red Army had

three weeks' start on them. The

ma

rr: hi nil

columns, which often stretched over 90 kilometres,

were made up of young

peasant boys from south-eastern China. Fifty-four

per cent were under the age of 24.

Zhu De had left a vivid description of these

young soldiers:

They were lean and hungry

men, many of them in their middle and

late teens. .most were illiterate.

Each man wore a long

sausage like a ponch...filled with enongh rice

to last two or

three days.

(A. Smedley,

Tile

&.eet Ave, Calder, New York, 1953,

pp.

311-12)

By mil-November life became more difficult

for the Long Marchers. One

veteran recalls:

Whfin hard pressed by enemy forces

we marched in the daytime and

at such times the bombers pounded

us.

We would scatter and lie

down; get up and march then scatter and

lie down again, hour

after how.

Our dead and wounded were rally and

our medical

workers had a very hard time.

The peasants always helped

us

and offered to take our sick,

our wounded and exhausted.

Each

man left behind was given some money, ammunition

and his rifle

and told, to organize and lead the

peasants in partisan warfare

when he recovered.

(Han Su yi n,

Crtppled Tres, Jonathon Cape, London,

1970, pp. 311-312)

When entering new areas the Red Army established

a pattern which was

sustained throughout the Long March:

We always confiscated the property of

the landlords and

militarist officials, kept enough food

for ourselves and

distributed the rest to poor peasants

and urban poor... We also

held great mass meetings.

Our dramatic corps played and

sang

for the people and our political workers

wrote slogans and

distributed copies of the Soviet

Constitution....I1 we stayed in

a place for even one night we taught the peasants

to write six

characters: 'Destroy the Tuhao (landlord)

and 'Divide the

Land' .

(A.

Smedley, Th e greet

Atold,

Calder, New York, 1958, pp. 311-12)

20

BEST COPY AVAIL13LE

.

-

2s.:

-

-

COMPULSORY THIRD PARTY Personal Injury Insurance ----"'"g

QBE

0

C

0

R

T

A

C

a

P

GEE INSURANCE LIMITED .4.c.N aoo

a99

MOTOR ACCIDENTS (CP) UNIT

PO. SOX 1652

NORTH SYDNEY 2059

TELEPHONE . 131 303

N' WINSER

2525

This is not a vehicle registration certificate

YOU MAY BE ENTITLED TO A

SPECIAL DISCOUNT.

CALL US

ON 13.1.303

( LOCAL CALL COST

ANYTTH:RE I N NSW)

FOR MORE

I NFORMATI ON .

CEWCIFICATE No:

36-0021618604-3

POLICY No

A0-0083000-CTP

The

meow* on this insurance Is payable on or tailors tn. DUE DATE.

The Third Party ;lousy lakes effect on the data of registration and

terminate* On

the date on +neon the registration Moues II aCConlance moth 111* MOTOR

ACCIDENT ACT 1981.

if CT" Insurance and reguttnitton are effeCted after the DUE DATE.

In

accordance otth the Moto accident, act tbSt. /Ou may be sersoneile

hail*

if

yoU Catlike infUrf td arlOther *boson.

Payment instructions are on the reverse of this nonce.

REG No.

EXPIRY DATE

RENEWAL No.

OG.1906

23/12/92

00000039

VEHICLE

E6 MI TSTJ

VIN/CHASSISAINGINE

No.

TM2H41TL19029803

GARAGED POSTCODE

CLASSIFICATION

PREM CODE

2525

1

601

PLEASE PAY THIS AMOUNT

DUE DATE

23112/91

239.40

Pavement Date - Rectum or Stew°

Insurance must be paid before including ATA copy with your registration

papers

Pay your insurance to your Insurance Company before including this part with

your registration papers

COMPULSORY THIRD PARTY Personal Injury

Insurance

Nave and IslOons

. N..

WINSER

1525

Peewee Ouse - heesset er them

-'4*;;;.

t'ea"-et..K

Mee Rim OW I

VeloChessimerAeateebeineer

I tense at Cowl hes 10

I Nuerer Coes

I CTIP

0GJ906

I 714214ITEI9029130 I

I

IZ

100000000I

36

I

002161E6CM "r:-

01 00000000 36'00216.18604. T

cmulsoaEma 36-00216186G4-3

Per veer Membialseeee "our Inmereweireest lee peki at as* Onesolt of Wesiess.

The leek wit ressol CialsmerCemy Ira MOW tb.

For melt of

avocet*4

Ulestpac Banking Corporation

STONILY OPPPCZ.

mom This Meet set be iniesissnee UMW that Imam internil oweeseires.

The tune le not to be modOloialso leedaleys on Irseemetisa

pesads ot amass I iheesese vise ne* be avidialibi 'MN ciesnan

Mosewn

Of Cfleellie

ewe on toy 151idenwe

Payment Date - Roma or Stamm

Five of Inmates fee at

any digefelle elraflerl

7 CREDIT

OBE INSURANCE LIMITED

AGA. cos 137

,

2 1

C

61

Toms

IRCc163

032010.00I: 760,0436o

239140.

Having

a

whale of

a

time

'What :5 the biggest fish in the world?" The

answer is hat, of course, the blue whale

For

wholes are not fish but mammals. :t is in fact

'he whale shark, which can grow to 15.

metres :ong and weigh 50 tonnes

.

However.

when asked to name the biggest creature

that ever lived. this time the answer would

indeed be the blue whale.

The blue whale is the biggest of ail animals.

It can grow to 25 or 30 metres long, which is

as !ong as 8 cars :n a line. (In the aid days.

before whaling, they grew to 40 metres.;

And it can weign over 1 00 tonnes as much

as 25 elephants. There are many other types

of whale living in

the oceans around

Australia and these are pretty big too.

What do we mean when we say that 'he

whale 's a mammal and not a fish? Weil.

'here are three main differences. Firstly,

whales and other mammaisi are warm-

bioocieci whereas fish are cold-0100am

Secondly, whales have

wnerecs fisn

nave scales. ;Actually wholes have very little

hair but their skin

is very much like the

ordinary mammal skin.) And thiraly, wnaies

give birth to their young and suckle them on

milk, whereas fisn lay eggs.

Being a mammal aisc means that the whale

breathes air :n and out of :ts :ungs. !ike yau

and me. However, the air goes :n and out

through a "'blowhole an top of the whale's

head. not through .ts mouth. In this way, the

bicwhcie is

like the whcieis two nostrils,

which have joined together and movec to its

forehead!

A blue whcie can stay underwater for 'en

minutes or more on one breath of air sucked

in hrough the biowhole. When the whale

returns to the surface t breathes out and is

areath. being warm and moist, condenses .n

the cola ocean air like ;,our breath aces on

a :old winters -naming). This fountain of

vapour can be seen a long way off arta shows

wnere the whale tics surfaced. This :s why

the aid whcie-nunters used to shout 'There

she oiowsi"

There are 'we main groups of whales.

disringuisned by the way they feed. The first

group are catlea the baleen or witcriei one

11,

22

BEST COPY AVANALE

wnc:es. They 'eec ay iiitering our

Sala!

red

res :rcrn -he secwcrer

-cws

sieve cicres nsice -heir -ncuths.

The sieve

otcres ncng ccwn :nsice he

knees =urn,

!lire on hternai rricusrcche. The water Sows

:n !hrcucn he mouth wnen .t's open anc

whale -hen pushes :ts 'ongue -crward :arta

forces he .,eater out aver he sieve plates.

Smell creatures called krill (see cage 34) are

drained l'rorn he seawater, licked di the

Oates. and swailowed by he whale.

The sec-and group ai whales is caded

toothed whales, They teed on :urge animals

which they catch and tear up using their rows

or sharp teeth. Killer whales

and sperm

wncies aelong 'a

second group. !filer

wncies .:an ze escec:ciiv

'eroclous anc

attack seals. penguins. scula. !arge

aria

even other wnctes.

a-

:

I:rt...

.R6 2.1

i...

2.,..M.....

1.0,

.........

.0.4i;

.

1. .".

...-

23

BEST tkii'V

CHAPTER OWE

The Royal Heathside Hospital,

in a fashionable suburb

of

London,

was the epitome of excellence in modern medicine.

Its

structure of polished black stone and gleaming chrome

rose

to

an

impressive

height of

twelve

storeys,

5

contrasting

sharply with the small shops and

streets

of

quiet Victorian houses on its doorstep.

At

first

there

had been some protests when

this

giant

started to rise in the neighbourhood,

but during the

ten

years

since its completion the locals had grown proud

of

10

their new hospital.

There were

700 beds in spacious and

well-equipped

wards and the very latest technology in all

supporting departments.

Added to that

a thriving Medical

School and an efficient School of Nursing

...

'Wby,

it's

almost a pleasure to be ill these days!'

So

15

said

Hr.

Lomond

to

Dr.

Stirling,

the

stalwart

new

registrar, on his first visit to Addison Ward.

-

The patient slipped his arm around the trim

waist of young

Sister Bryony Clemence.

'They're a vest bunch of nurses

on this ward,

roc,

but she's the cream!'

He grinned

at

20

her

embarrassment as she eased herself away.

'You don't

need to blush, Sister.'

The

houseman,

John Dawson,

accompanying

Dr.

Stirling,

winked broadly at Bryony, but the registrar,

concentrating

en

the

charts he was studying,

either did not

hear or

25

chose to ignore the remarks.

He glanced towards Hr. Lomond,

on Addison for the control

or his diabetes, and observed pleasantly:

'Well, you seem

to be stablising nicely now.

You'll be going home before

long.'

30

The small group moved on towards their last

patient,

but

before discussion could begin both doctors' bleeps

sounded

urgently.

Flaking

for

the nurses' station

John

Dawson

picked

up the telephone.

After a brief exchange he came

speeding beck to murmur urgently to the registrar:

'It's a

35 cardiac

arrest,

Simpson

Ward.'

Whereupon both

he and

Grant Stirling were gone in a flash.

Student

Nurse ratty Newman,

fresh from the

Introductory

Block and full of enthusiasm,

dogged Bryony's

footsteps.

'Does that mean we have to get a bed ready, Sister?'

Bryony smiled at her eagerness,

'No,

the patient will go

to Intensive Care first

... if they're in time.'

She

adjusted

a white hairclin holding the frilly cap

on

her

honey-blonde

curls and glanced at her

watch

as

an

orderly

appeared

pushing

the

patients'

tea-trolley.

'Well,

I

expect

that's

the

end

of

rounds

for

this

45

afternoon.

You can relieve Nurse Smith while she

goes to

tea,

fatty.

She's in High Dependency,

with Tina.

You

know, the new anorexic girl ...'

The

junior

sped off to her appointed task

while

Bryony

detailed others of the staff to go to tea.

P,1,71.,AHE

A

car,

like

a

bus,

is a

vehicle for

transporting people. Cars

can usually carry

a maximum of 5 or 6 people whereas

buses

can cany many more. Most cars use

petroleum

or

diesel fuel

as do buses, but

there are

some cars and buses which life

electric. Many people

are killed or initIted

each

year in car accidents. Bus travel, by

contrast,

is

a very safe form of travel,

although just

one serious accident can

claim

many lives.

in Austraiia,

most

people drive

cars, and the roads of many

urban centres

are choked with this form of

private transport.

Buses

can reduce the

amount of traffic on the road because they

can carry more people, and therefore they

save on fuel and other costs.

Buses

generally operate

on urban, suburban, or

inter-urban

routes.

As well

as buses

operated by the

government,

there

are

some private bus companies, particularly

for long distance travel.

Essay Writing: 011T MASTER 12

25

Aboriginal cuitures...did not survive in the face of European invasio

This was due in part to the ethic of territoriality, which placed mo

emphasis on defence than on offence. Because of the strict adherence t

this, no social mechanisms existed for creating armies to fight the

Europeans, who had an easy time tackling tribe after tribe. As welt

`gibes found it impossible to unite in the short time allowed. The

Aborigines' emphasis on the necessity of stability and the European

desire for expansion, progress and change inevitably clashed....--

4

(Queensland Department of Education, (1988) Primary, Social Shales

Sourcebook: Year 4)

26