ISSN: 1962-5361

Disclaimer: This Philadelphia Fed working paper represents preliminary research that is being circulated for discussion purposes. The views

expressed in these papers are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Federal Reserve Bank of

Philadelphia or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors. Philadelphia Fed working papers

are free to download at: https://philadelphiafed.org/research-and-data/publications/working-papers.

Working Papers

Assessment Frequency and Equity

of the Real Property Tax: Latest

Evidence from Philadelphia

Yilin Hou

Maxwell School, Syracuse University

Lei Ding

Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia Community Development and Regional Outreach

David J. Schwegman

School of Public Affairs, American University

Alaina G. Barca

Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia Community Development and Regional Outreach

WP 21-43

December 2021

https://doi.org/10.21799/frbp.wp.2021.43

COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT AND REGIONAL OUTREACH

Assessment Frequency and Equity of the Real Property Tax:

Latest Evidence from Philadelphia

Yilin Hou, Lei Ding,* David J. Schwegman, Alaina G. Barca

December 2021

Hou: Maxwell School, Syracuse University

Ding and Barca: Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia

Schwegman: School of Public Affairs, American University

* Contact author: lei.ding@phil.frb.org. The authors thank Jeffrey Lin, Keith Wardrip, and Stephen Ross for

their helpful comments. The views expressed in these papers are solely those of the authors and do not

necessarily reflect the views of the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia or the Federal Reserve System. Any

errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors.

1

Abstract

Philadelphia’s Actual Value Initiative, adopted in 2013, creates a unique opportunity for

us to test whether reassessments at short intervals to true market value and taxing by such values

improve equity. Based on a difference-in-differences framework using parcel-level data matched

with transactions in Philadelphia and 15 comparable cities, this study finds positive evidence on

equity outcomes from more regular revaluations. The quality of assessment, as measured by the

coefficient of dispersion, improves substantially after 2014, although the extent of improvement

varies across communities. Vertical equity, measured by price-related differential, also

improved, although it was still above the standard threshold. Cross-city comparisons confirm

Philadelphia’s improvement in quality and equity of assessments after adopting the initiative.

These results highlight the importance of regular reassessment in places where property values

increase quickly, and they shed light on the disparate impacts of reassessment across income,

property value, race, and gentrification status. The paper makes the case that the property tax, if

designed well, can be an equitable tax instrument.

Key words: real property tax; valuation; assessment cycle; equity

JEL codes: H20, H31, H71, R51

2

1. Introduction

Although the property tax has long been criticized as the most unfair, even “the worst”

tax (Jensen, 1931; Fisher, 1996; Cabral and Hoxby, 2012), it has persisted through today in the

United States as the most important own-source revenue for many local governments. It is fair to

say that local autonomy thrives when localities control their own mainstay revenue. For this

important reason, improving the administration of the property tax is a perennial task for the

public finance community. The negative reputation of the property tax is derived mainly from

issues and challenges in property valuation, which demands up-to-date information about

multiple aspects of properties and requires trained professional staff, thereby posing high costs in

terms of technology and personnel. On top of these difficulties, property valuation is also

susceptible to idiosyncratic errors in assessment. Property assessment, thus, is a complex,

constantly evolving field.

Lags in property reassessment — or delays in estimating changes in the value of a

property since the last assessment — and poor tax collection can adversely affect the horizontal

and vertical equity of any local property tax system, as well as erode a local government’s

revenue-raising capacity (Weber et al., 2010). Sudden and unexpected changes in tax bills from

inaccurate assessments can leave capital-wealthy but liquidity-constrained households unable to

pay their tax bills (Alm et al., 2016). Furthermore, the property tax is sometimes referred to as

the “least fair” tax by the average American (ACIR, 1987; Fisher, 1996; Cabral and Hoxby,

2012): Property taxes are often found to be regressive, such that lower-value properties face

higher assessments relative to their actual market values than higher-value properties (Berry et

al., 2021; McMillen, 2013; McMillen and Singh, 2020). In particular, in jurisdictions where

regular reassessment is not mandated by the state, fairness in taxation becomes a serious concern,

3

as house appreciation is less likely to be included in the assessed value owing to long lags in

reassessment.

This study evaluates whether reassessments at short intervals to true market value and

taxing by such values improve equity. In most states, real property tax law requires regular

revaluation of properties. For example, counties in the state of Washington are required to

annually update assessed values of all properties based on appropriate statistical data, and they

are also required to physically inspect properties at least once every six years.

1

The state of

Pennsylvania, however, is one of the few states that does not have statutorily mandated

reassessments on a fixed cycle (Montarti and Weaver, 2007). In Philadelphia,

2

historical lags in

property assessment have resulted in systematic inequities in the city’s property tax system.

From the 1980s to 2012, Philadelphia did not conduct a comprehensive reassessment. As a

result, the assessed value listed on most property tax bills was estimated to be 60 percent lower

than true market values (Dowdall and Warner, 2012; Ding and Hwang, 2020). The quality of

assessments was poor, and properties with similar market values were often listed with

dramatically different assessed values (Gillen, 2008). As assessments were increasingly out of

line with actual property values and the tax burden had become increasingly unequal with respect

to wealth, Philadelphia adopted a property tax reform in 2013, known as the Actual Value

Initiative (AVI). The AVI was not only the first comprehensive revaluation of all properties in

the city in a 30-year window but also broke from the tradition of fractional assessment to

reassess all properties at full market value. To improve the quality of property assessments,

under the AVI, the city reassessed every property and changed in 2014 how tax bills were

calculated. Philadelphia conducted another comprehensive revaluation in 2019.

1

See dor.wa.gov/sites/default/files/legacy/docs/pubs/prop_tax/homeown.pdf.

2

Throughout this paper, Philadelphia refers to the city of Philadelphia, rather than the metropolitan area.

4

The AVI requires more regular revaluations to address issues related to poor assessment

quality and increasing inequity in property taxation in Philadelphia. As a policy shock, it

provides a unique opportunity for us to answer our research question: Do regular short cycles of

reassessment generate an equitable distribution of the tax burden among property owners? The

consensus among scholars and practitioners is that annual reassessment best maintains equity and

efficiency (Dowdall and Warner, 2012; Weber et al., 2010). Given the high costs of annual

reassessments, however, a vast majority of assessing jurisdictions nationwide conduct

reassessments less frequently. This overarching question in fact embeds several minor but not

less important subquestions: What is the impact of regular comprehensive reassessments on

properties across neighborhoods? Are more regular reassessments alone sufficient to achieve the

equity goal? And if not, what other assessment practices could improve equity in property

taxation? With empirical estimates on horizontal and vertical equity, we then consider the

ramifications of assessment cycles on the efficiency of the cycles in terms of possible behavioral

patterns of property owners.

Taking Philadelphia’s two recent reassessments as natural experiments, this paper uses

parcel-level data matched with sales transactions in Philadelphia and 15 comparable cities across

the nation to examine whether regular reassessments at short intervals to true market value and

taxing by such values improve horizontal and vertical equity. Horizontal equity, measured by the

coefficient of dispersion (COD) in this paper, measures the level of assessment uniformity:

whether parcels with the same (or close) attributes would be assessed and taxed at equal

amounts. Vertical equity, measured by the price-related differential (PRD), is concerned with the

inequality in assessments for properties of varying values: whether less expensive properties are

systematically assessed at higher ratios relative to their market values and thus bear a higher than

5

the fair share of property taxes than more expensive properties. The results suggest that before

the AVI, the quality of Philadelphia’s property assessments was worse than almost all other

cities in our sample and property taxes in Philadelphia were much more regressive than other

cities, as well. Pursuant to the AVI, the comprehensive revaluation in 2014 (and again in 2019)

led to marked improvement in assessment quality (horizonal equity), although the extent of

improvement in uniformity was much smaller in disadvantaged communities.

The vertical equity of Philadelphia’s property tax system also improved after the city

adopted the AVI. While a PRD between 0.98 and 1.03 is generally considered as the acceptable

range, Philadelphia had a PRD as high as 1.42 pre-AVI, suggesting lower‐priced homes were

systematically assessed at a greater percent of their market values than high-value ones. The

PRD declined to 1.28 in 2014 and further to 1.14 in 2019, showing a continued mitigation of

assessment inequity post-AVI. Effective tax rates also experienced larger declines for properties

in more disadvantaged communities, namely majority-Black or high-minority neighborhoods,

low-income neighborhoods, or lower-income nongentrifying neighborhoods. Cross-city

comparisons confirm that assessment quality in Philadelphia improved substantively against

other cities after 2014, although Philadelphia’s PRD remained above the popular threshold.

Overall, our results highlight the importance of regular reassessments in cities that

experienced large increases in property values (e.g., through gentrification) and shed light on the

disparate impacts reassessment might have across income, property value, race, and

gentrification. Thus, the paper makes the case that with regular reassessments, the real property

tax can be an effective tax instrument, with facilitation by other practices or tax relief programs

to ensure and maintain an equitable impact. This paper contributes to the literature on property

taxation in a number of ways. First, the policy shock of the AVI allows us to identify the causal

6

effects of more regular reassessments on improving assessment quality and redistributing the

property tax burden. This paper provides updated evidence on the (horizontal and vertical) equity

effects of property revaluation after a long lapse in reassessments. Second, this study looks into

the heterogeneity of the effects among properties in different neighborhoods and find that more

regular reassessments provide greater benefit for property owners in more disadvantaged

neighborhoods, although assessment accuracy does not necessarily improve as much. Finally,

our research question cuts deep to the core of property tax administration — equity and

efficiency. Conventional taxation theory has these two principles as holding a tradeoff. We argue

that in terms of the property tax, equity and efficiency can move in unison — raising one will not

lower the other, but rather the two will mutually reinforce through more frequent, regular

property tax reassessments.

2. Analytical Framework and Context

2.1. Property Assessment and Rationales

Value Assessment

Value assessment in property taxation determines the tax base of each property at some

snap point of time via obtaining an as accurate as possible estimate of the market value of a

property. Estimates are then converted into assessments either at 100 percent of market value or

at a uniform percentage (assessment ratio) of the market value. The former is full value

assessment, whereas the latter is a fractional assessment. As long as the estimates are accurate,

the assessed value, A, matches the market value, V, providing a reliable tax base.

The purpose of obtaining accurate estimates of market value is to equitably distribute the

burden of financing local public services, with the assessed value as a ratio of the total tax base.

7

The rationale for regular reassessment is that market value fluctuates. Although the value of

properties trends up over time, the extent of change can be very uneven across neighborhoods,

property types, and value ranges in a jurisdiction. It is a heterogeneous process on several

dimensions. At the neighborhood level, amenities and typological features are one dimension. By

housing type, some appreciate quickly, some slowly, and some do not grow or even depreciate.

Along the range of housing prices (quality), the elasticity of demand and supply is another

dimension to consider.

The property tax is a levy on the stock of household wealth. The heterogeneity of value

changes over time demands regular reassessments to distribute the burden of public services on

the basis of household wealth. Absent regular assessments, the distribution of the tax burden

among properties will not be equitable, eroding the fairness of the tax and trust of the public in

government.

Assessment Cycles

In this paper, we use the following working definitions of assessment cycles and this

paper explores the relationship between the length of assessment cycles and a set of equity

(uniformity) measures. Comprehensive assessment (mass appraisal) is conducted in discrete

cycles by the year (valuation upon transaction or upon completion of new construction is

different). The shortest cycle is annual, which offers the highest probability of match between

market value (V) and assessed value (A), , which is the best for securing equity; thus, it is

the ideal cycle. The annual cycle is taken as the default. There can be a parameter before A,

, 0 < 1. When a jurisdiction uses estimated market value as assessed value, = 1;

when a jurisdiction uses a fractional assessment system, < 1.

8

We classify time between reassessments by three categories. The first category, a short

cycle, refers to one that reassesses every two or three years. Short cycles are suboptimal relative

to annual valuations, but the annual cycle is often not practicable for various reasons. For

example, a small jurisdiction or one with inadequate resources cannot afford to assess each year.

Uniformity of assessment from each comprehensive assessment can maintain most of its force

within a reasonably short period; thus, a short cycle may maintain uniformity before a large

inequity occurs. Short cycles arise as a compromise from the ideal cycle, often as the result of

balancing the high cost of an annual cycle with uniformity of valuation.

The second category, a regular cycle, refers to assessments that are conducted once every

four to six years. Although longer than a short cycle, these cycles are at least regular. The

regularity of valuation between two assessments mitigates erosion to uniformity (equity) to a

limited extent. These cycles often are adopted by small taxing jurisdictions, mainly for cost

reasons.

Finally, a long or irregular cycle refers to assessment cycles that are longer than six

years, beyond the length of a full economic cycle. These long cycles often become or drag into

irregular, indefinitely long cycles. These are the scenarios that have often occurred, caused

extreme inequity, and triggered the tag of the “worst tax.”

Under the U.S. federal system, states fall in at least two types — strong states and home

rule states — in their relation with localities in the regulation of local taxation. The former type

are Dillon-rule states that not only stipulate short or regular cycles but also strictly enforce the

required cycle. Take Virginia, for example: the 1984 revision of the Virginia Code requires

counties and cities to adopt a regular (fixed-length) cycle. The latter type allows local discretion,

9

without stipulating much regulation. New York is an example of home rule states, where local

taxing jurisdictions decide their own assessment cycles.

The administration of the property tax has evolved toward regular, short, preferably

annual reassessments, which are also what the states have mostly tried to promote since the

second half of the 20th century. Among the rationales for the preferred cycles is a technical

consideration: assessment is heavily subject to human judgment based on limited information,

out of which errors are unavoidable. The technical errors capitalize into property values and, if

not corrected in a timely manner, can erode tax equity for years.

2.2 Gaps in What Is Known

The academic literature has been thin on the administration of the property tax in general

and on the effects of assessment cycles in particular. Among the few earliest studies, Geraci

(1977) and Bowman and Mikesell (1990) identified some determinants of assessment equity,

including characteristics of assessors, staffing of the assessor’s office, and tools for valuation.

Mikesell (1980) examined the impact of assessment cycles on assessment quality. Using data

from Virginia local tax assessing units in the years 1973 through 1976, he found that 68 percent

of the units in regular cycles had better outcomes (higher uniformity or a 10 percent lower COD)

compared with units in annual reassessment, and he found much smaller improvement in the

latter group. He speculated that in states that require annual reassessments, revaluations were

often just copying prior years’ numbers, probably with a flat percentage adjustment for all

properties.

More recent research better accounts for potential simultaneity and omitted variable bias.

Using cross-sectional data (1992) of assessing towns and cities in New York, Eom (2008) found

10

a positive relationship between assessment uniformity and frequent reassessment. Specifically,

each additional year of lag in reassessment may lead to a 1.6 percent reduction in assessment

uniformity, while an additional reassessment over the previous four years improves uniformity

by 17.8 percent. However, there has not been more recent updated empirical evidence to support

that annual reassessment should be the norm or that short and regular cycles are preferred. This

paper fills the niche.

2.3 The Actual Value Initiative of Philadelphia

In 2013, after several years of public discussions and evaluations, Philadelphia adopted a

comprehensive property tax reform, known as the Actual Value Initiative (AVI), which became

effective for property tax bills in 2014. Under the AVI, Philadelphia conducted the first

comprehensive reassessment since the 1980s for the market value of every property in the city.

Consequently, the newly assessed values of properties under the AVI would more accurately

reflect their market values. For example, from 2005 to 2013, the mean assessed value of single-

family residential properties in Philadelphia remained almost flat, but after the full market value

reassessment, the average assessed value almost tripled (Ding and Hwang, 2020). All properties

were reassessed again at full market value in 2019.

Under the AVI, the city also changed the way it calculates tax bills (Ding and Hwang,

2020; Dowdall, 2015). Specifically, before 2013, the city used fractional assessment, at 32

percent (a predetermined ratio), so that less than one-third of a property’s estimated market value

counted as assessed value, and the nominal tax rate was 9.771 percent. The AVI replaced

fractional assessment with full market value assessment, with 100 percent of a property’s

estimated value as assessed value to calculate tax bills. Claimed to be a revenue-neutral reform,

11

the AVI redistributed the tax burden in the city, and the nominal tax rate plummeted to 1.34

percent in 2014. Properties with no or small increases in market values since the 1980s benefited

with lowered tax bills, whereas those with large appreciations in value received larger tax bills.

The effects of the two reassessments under the AVI are very clearly illustrated in Figure

1, where the dashed line marks the mean assessed values and the solid line marks the mean

market values for single-family residential homes. Between tax years 2010 and 2013, there was

very little change in the average assessed value for these properties; only new sales or properties

under appeals were likely to be reassessed. Beginning in 2014, an almost three-fold increase in

the assessed value considerably closed the difference between the average assessed value and the

average market value. Absent comprehensive reassessments from 2014 through 2018 (there was

a small increase in the tax rate in 2016 from 1.34 percent to 1.4 percent), the gap grew wider

again, with assessed value decreasing slowly, likely because of appeals and market value

increasing quickly. Then the second comprehensive full value reassessment in tax year 2019

closed some of the gap between the two values. Overall, the recent AVI tax reform in

Philadelphia as a natural experiment offers the best and most representative case for our study.

While the AVI requires the city to reassess all properties more regularly, it does not

necessarily change the administration of property assessment practices or the quality of

assessments. In other words, while a comprehensive reassessment should render the assessed

values closer to true market value, it does not necessarily make assessments more equitable, and

its effectiveness is still an empirical question.

12

3. Data and Methodology

3.1 Methodology

This study intends to isolate the effect of the AVI on the level of horizontal and vertical

equity of residential property assessments by comparing the assessment outcomes before and

after the adoption of the AVI in Philadelphia with those of a national sample of peer cities. Here,

properties (sales) in Philadelphia are considered as the treatment group because they became

subject to regular revaluation under the AVI post-2014. Properties in peer cities that did not

experience such a policy shock are considered as the comparison group. The two-way, property-

level, difference-in-differences (DID) model can be specified as:

Y

ijt

= β

0

+ β

1

TREAT

j

+ β

2

POST

t

+ β

3

TREAT

j

*POST

t

+ ΘTRACT

j

+ λYEAR

t

+ ε

ijt

(1)

in which Y

ijt

represents the outcome measure for property i in tract j and in year t. TREAT

j

is the

dummy variable that represents properties in Philadelphia (the treatment group). POST

t

is the

time dummy and is assigned a value of one for the post-2014 period. TREAT

j

*POST

t

is the two-

way interaction of the treatment and the time dummies. While both TREAT

j

and POST

t

are

omitted in the estimation because we include the tract and yearly fixed effects in our model, we

can still identify the effects of AVI by estimating the coefficient, β

3

, of the interaction term,

TREAT

j

*POST

t

. TRACT

j

and YEAR

t

are vectors of tract- and year-fixed effects.

To evaluate the heterogeneity in the effects of the AVI across neighborhoods that differ

by income, racial composition, and gentrification status (for the definition in this paper, see

footnote 15), we employ the following model using data from Philadelphia only.

Y

ijt

= β

0

+ β

1

NBHD

j

+ β

2

POST

t

+ β

3

NBHD

j

*POST

t

+ ΘTRACT

i

+ λYEAR

t

+ ε

ijt

(2)

13

in which NBHD represents the different types of neighborhoods (by race, income, or

gentrification status) and the coefficient of the interaction, β

3

, captures the change in the outcome

measures post-AVI in the corresponding type of neighborhoods relative to the change in the

reference group. In other words, β

3

measures how the AVI impacts properties in a particular type

of neighborhood differently from other neighborhoods. All other terms are as defined in equation

(1) above.

3.2 Measures of Horizontal and Vertical Equity

Horizontal equity (i.e., assessment uniformity) is concerned with assessment

differentiation between parcels with the same (or close) attributes. Thus, a uniform assessment,

with all properties of equal value being assessed and taxed at equal amounts, achieves horizontal

equity. Vertical equity is concerned with the treatment of properties over the range of values.

Applying different assessment ratios to properties of varying values results in vertical inequity.

For example, a system in which less expensive homes are systematically assessed at higher sales

ratios than more expensive homes is regressive, while a system in which the assessment ratio

increases as property value increases is progressive. When the ratio is consistent across home

values, a property tax system is considered equitable.

The assessment ratio (R) is defined as the assessed value of a property to the actual sale

price of the property (assessed value [A

i

] divided by market value [V

i

] in the year the property is

sold): = /, in which V

i

can be proxied by the recorded sales price of each property. This

measure could capture both horizontal and vertical equity, with the major limitation that it does

not directly measure any deviation from the desired threshold.

14

The International Association of Assessing Officers (IAAO) has suggested acceptable

thresholds as industry standards for horizontal equity and vertical equity in property assessment.

Here, we discuss two measures, coefficient of dispersion (COD) for horizontal equity and price-

related differential (PRD) for vertical equity, that are most often used in the literature. Taken

together, the COD and the PRD characterize the degree of assessment equity in a particular

housing market.

Measure of Horizontal Equity

The most common measure to assess horizontal equity is the COD, which measures the

average percent deviation of an individual parcel i's assessment ratio from the target (or median)

assessment ratio in a jurisdiction. The calculation of the COD of a sample of sales transactions

can be expressed as:

=

|

|

= |1

| (3)

where R

0

is the target assessment ratio in the taxing jurisdiction. In an ideal scenario, every

property would be assessed exactly at its market value, and thus each property would have an R

i

of “1.” So we use a value of “1” for R

0

, and then the mean COD is computed as the average

COD across all properties. Higher values of COD indicate less uniformity in assessment, while

lower COD values suggest relatively uniform assessments, and thus imply that a property tax

system is horizontally equitable.

According to the IAAO Standard on Ratio Study (2013), a reasonable COD for single-

family homes is between 5 percent and 15 percent, conditional on the age of the property and

neighborhood type, and the target COD for residential properties in “older, heterogeneous areas”

15

such as Philadelphia should be 15 percent or less.

3

Accordingly, we also created a dummy

variable that equals 1 if a sale has a COD of 15 percent or less.

To measure the actual tax burden for property owners, we use the effective tax rate as

another outcome, which is calculated as the tax amount divided by the market value of the

property proxied by sales price of arm’s length transactions.

Measure of Vertical Equity

While there is a general consensus that the COD is an appropriate measure to examine

horizontal equity, there is no such consensus over how to test the vertical equity of a property tax

system. We use the PRD as the primary measure of vertical equity,

4

which is calculated by

taking the mean assessment ratio for all parcels in the sample and dividing it by the weighted

mean ratio, where the weight is the sale price. This calculation can be expressed as:

=

[4]

A PRD of 1 thus implies an absence of vertical inequity in property assessment in a

particular geography: Assessments would be perfectly uniform across home values if the

weighted mean is equal to the unweighted mean. A PRD greater than 1 suggests the presence of

assessment regressivity, in which higher-value properties are assessed at lower ratios, and higher

3

As Eom (2008) notes, there is a nonlinearity inherent in the COD — it is much easier to decrease a COD from 30

percent to 20 percent than from 15 percent to 5 percent.

4

There are some important limitations with the PRD in measuring vertical equity, because PRD tends to be

estimated downward because of right-lying outliers that skew the distribution (Almy et al., 1978; Gloudemans,

1999; Carter, 2016). A number of strategies to evaluate the vertical equity of a tax system have been proposed (see

Paglin and Fogarty, 1972; Cheng, 1974; Almy et al., 1978; Bell,1984; Sunderman et al., 1990; and Kochin and

Parks, 1982).

16

values of PRD indicate greater regressivity. A PRD less than 1 instead suggests the presence of

assessment progressivity, in which lower-value properties are assessed at lower ratios.

The IAAO Standards (2013) suggest a PRD between 0.98 and 1.03 as the acceptable

range. This range is asymmetric around 1 because there is an upward bias in the denominator,

which does not affect the numerator. A PRD above 1.03 is generally considered regressive, i.e.,

favoring high‐valued homes, while a PRD below 0.98 is deemed progressive, which favors low‐

valued homes.

3.3 Data

Data used in this study primarily are obtained from two sources, in addition to data from

the U.S. Census Bureau (the 2009–2013 American Community Survey and U.S. Census

TIGER/Line Shapefiles). The first source is the publicly available administrative parcel-level

data from the City of Philadelphia’s Department of Revenue (DOR), the Philadelphia

Department of Records, and the Office of Property Assessment (OPA). The parcel-level tax files

contain annual assessed values, characteristics of each parcel (e.g., property type: residential or

commercial, single-family, condo, or multifamily), tax amount, as well as exemptions and

abatements, all from 2010 to 2019. Each parcel has a unique identifier that enables us to match

units across data sets. We also used real estate transfer data compiled by the Philadelphia

Department of Records,

5

which were merged to respective parcels; thereby, we have information

on assessments and taxes for properties that were transferred during the study period. Using

ArcGIS, we also conducted a spatial join to link property-level data to Philadelphia’s census

tracts.

5

These are available through OpenDataPhilly at www.opendataphilly.org/.

17

The administrative data from Philadelphia are compared with control group data from

CoreLogic Solutions, the latter of which were used to construct a transaction and assessment data

set for our control group of comparable cities for the 2012–2015 period.

6

The selection criteria

are: (1) the 30 largest U.S. cities and one smaller peer city, Pittsburgh, from Pennsylvania based

on its similarities to Philadelphia; (2) cities with consistent and reasonable counts of observations

in the data set during our sample period; (3) cities that conducted no comprehensive overhaul of

their assessment system based on our knowledge during our sample period. Applying these

criteria, we narrowed down to 15 cities. They are Baltimore; Charlotte, NC; Columbus, OH;

Dallas; Denver; El Paso, TX; Fort Worth, TX; Houston; Oklahoma City; Phoenix; Pittsburgh;

Portland, OR; San Antonio; Seattle; and Washington, D.C. A few other major cities, such as

New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles, were not selected, primarily because of either limited

coverage during the study period or a significant number of observations with missing values in

their assessment or sales data.

We made a few additional decisions in creating the final sample of residential properties

for our analysis.

7

First, the analysis focuses only on arm’s length transactions of single-family

residential properties. Arm’s length transactions generally refer to market-rate sales involving

buyers and sellers with no previous relationship (rather than, for example, sales between relatives

or foreclosure auctions). Prices from arm’s length transactions thus should better reflect true

market values, since buyers and sellers in these transactions are more likely to be seeking a price

that maximizes their own self‐interest. We focused on single-family home sales primarily

because of the higher volume of sales within this property class compared with other types of

6

Unfortunately, CoreLogic Solutions only offered this data set to us through 2015.

7

In addition to the two decisions discussed in the text, we also limited each property parcel to one transaction per

month to remove duplicates. If there were multiple transactions of the same property parcel in a month, we only

included the transaction with the highest price.

18

residential units, such as multifamily residential and condo units. Additionally, single-family

homes have a higher within-class uniformity than other property classes.

Second, sales with a missing value for the sales price, extremely low or high prices (those

with assessed values below $1,000 or above $2,000,000), or with extremely high or extremely

low assessment ratios were excluded from the analysis. The sales prices for 4.8 percent of sales

are missing in Philadelphia; another 26.9 percent of sales have sales prices below $1,000.

8

These

observations were excluded to mitigate the bias induced by these outliers. In addition, a small

share of sales transactions suffer from the issue of invalid transactions, as a 2018 audit report of

the Philadelphia OPA highlighted, for which we can conclude quite confidently that either the

sale price is not valid, the assessment does not reflect current market conditions, or the property

data underlying the assessment is far from accurate.

9

Because it is impossible to verify the

validity for millions of sales over multiple years, we followed the IAAO-recommended

maximum trimming limits

10

and excluded sales with assessment ratios above 3.0 or below 0.1

(about 5 percent on each side), which represent a further 9.1 percent of transactions.

11

After

trimming, the statistics provide a more logical and meaningful basis to come to informed policy

recommendations and tax administration practices.

8

Sales prices were recorded as $1 in 20.1 percent of sales, meaning these were not arm’s length sales. Our trends

were robust to alternative exclusion thresholds.

9

By the 2018 audit report of Philadelphia OPA: “Some, if not many, of the sales as identified as valid by the City are

not truly valid. This makes it impossible to continue the analysis without considering further action to yield a

clearer insight regarding assessment accuracy.”

10

The IAAO Standard states it is appropriate to set maximum trimming limits of no more than 10 percent (20

percent in extreme circumstances with small samples). We use an acceptable level of trimming — about 10 percent

of observations — to drop the outliers, while making sure the final sample still allows for a meaningful analysis and

reflects actual overall performance.

11

And the share of sales with invalid or small sales prices or with particularly large or small assessment ratios

decreases slightly over time during the study period. Thus, our results are likely an underestimate of the AVI’s

impact.

19

These data cleaning procedures were followed also for the control cities. The data are

made up of single-family properties, with duplicate month-property records cleaned; extreme

sales prices were removed; the same boundaries of assessment ratio values were trimmed; and

sparse tracts were removed. We also removed cities with sparse or inconsistent amounts of data

across years and focused on the years 2012–2015 in order to retain the 15 selected cities.

Our final sample has 156,171 sales transactions during the 2010 to 2019 period in

Philadelphia for our baseline regression. For the cross-city regression, there are 704,899

observations for the control group and 54,683 for the treatment (Philadelphia) of single-family

home transactions during the 2012–2015 period.

4. Impact of AVI on Equity: Descriptive Analyses

4.1 Horizontal Equity

Table 1 provides summary statistics of single-family residential properties in Philadelphia

by year from 2010 to 2019, where columns (1) to (4) are contextual information and columns (5)

to (9) are analytical indexes derived from the first four. The number of transactions and mean

sale price were both low through 2012 as part of the sluggish recovery from the Great Recession.

The market began to warm up in 2013 and has been improving since, with transactions and sale

prices smoothly trending up. From 2010 through 2013, the mean assessment ratio stayed in the

mid-50s, with the CODs also in the mid-to-high-50s, almost four times the acceptable level of 15

percent set by the IAAO for “old, heterogeneous areas” like Philadelphia. The percentage of

CODs below 15 percent was in the single digits, and the PRD was way above the IAAO

threshold.

20

Adopted as a response to increasing inequity in property taxation, the AVI seemed to

have done what it is supposed to do. The average assessment ratio more than doubled, increasing

to 119 percent in 2014. That is, the AVI led to increased assessed values in general, and an

average greater than 100 percent suggests that at least a significant share of assessments were

higher than their actual sale prices. The average COD decreased by a quarter from 55 percent in

2013 to 41 percent in 2014 — horizontal equity saw a huge improvement. The share of

assessments with a COD below 15 percent quadrupled from about 8 percent to 33 percent. These

indices showcase a substantive amelioration of horizontal equity in property assessment due to

the full valuation reform.

On the basis of the reassessment in 2014, the second reassessment in 2019 generated

continued improvement. The absolute error of the average assessment ratio decreased from near

20 percent (19.3 percent in 2014) to about 9 percent in 2019. This adjustment could be

explained, among other reasons, as institutional learning from repeated reassessments within a

short window of time.

12

The mean COD improved a further 9 percentage points (from 41 percent

to 32 percent), confirming the benefit of reassessment in a short interval, although it remained

more than double the threshold of 15 percent. The share of CODs within the threshold, however,

dropped by 4 percentage points, for which we do not have a good explanation, except that the

city has a lot to learn while it is still in the exploratory stage toward regular cycles of assessment

after a three-decade lapse.

Figure 2, showing the density of the CODs for residential sales in 2013, 2014, and 2019,

illustrates more finely how assessment accuracy improved from reassessments at short intervals.

In 2013, the density peaked at 0.6, with the whole distribution being far right from zero. The first

12

Needless to say, there are other contributors, including repeal-induced assessment adjustments due to the sharply

increased housing prices during that period relative to the largely unchanged assessments from 2014 to 2019.

21

revaluation (in 2014) shifted the distribution to the left, which suggests a significant

improvement in horizontal equity across properties. Then, the second reassessment (in 2019)

shifted the tail of the distribution further to the left, confirming the results from the statistical

analyses above. Clearly, assessment accuracy in Philadelphia has been improving following the

two comprehensive assessments since the AVI was adopted in 2014.

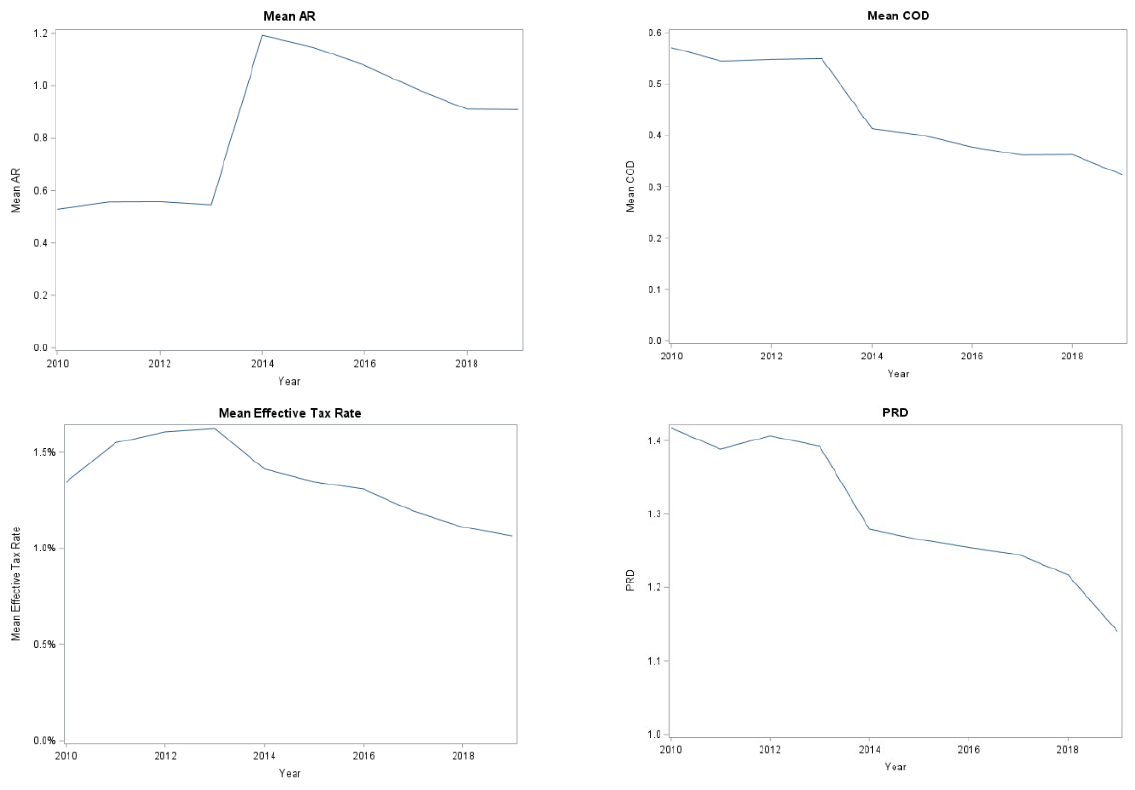

We can also look at the effective tax rate to determine how these trends in assessment

accuracy take shape in actual taxes paid. The bottom left panel of Figure 3 graphs the mean

effective tax rate over time. Post-AVI, around the same time that averages in the assessment ratio

increased and the CODs and the PRDs decreased, the average effective tax rate declined.

Contrary to these other metrics, the citywide average effective tax rate did not experience as

dramatic of a change between 2013 and 2014, but it has still steadily declined since 2013.

Figure 4 compares trends from 2012 to 2015 between Philadelphia and the control group

of 15 cities. The mean values of assessment ratio, the COD, percentage of CODs below 15

percent, and the PRD of the control group are smooth over this four-year period; Philadelphia’s

metrics trend similarly to the control group pre-AVI for all values except the PRD but diverge

from the control group post-AVI. Philadelphia’s assessed value and proportion of acceptably

accurate assessments both jumped more than twofold in 2014, whereas the control group

experienced a lower assessment ratio and only a slight improvement in acceptably accurate

assessments. Philadelphia’s mean COD and mean PRD both fell drastically in 2014, whereas

those measures each fell only very slightly in the control group.

In Figure 5, we map the COD by census tract in Philadelphia for 2013, 2014, and 2019.

The left panel shows the COD in 2013, with most tracts having high CODs. The middle panel,

for 2014, shows substantive improvement from the 2014 reassessment, but the CODs in over half

22

of the tracts were still quite high, especially in areas close to the downtown urban core. The right

panel, for 2019, shows moderate COD values across the city, indicating huge improvement

overall and a decline of the intense cross-tract variation in COD values. We can infer that even

with the AVI, one comprehensive assessment cannot solve long-accumulated issues all at once;

regular reassessment at short intervals, as well as improved quality of reassessment, is the key.

Overall, assessment accuracy improved after the AVI was adopted in 2014. As shown in

Table 1, despite the improvement in the average COD in Philadelphia following the first full

market reassessment in 2014, as well as the second full market reassessment in 2019, there was

still significant variation in CODs. This pattern implies that each comprehensive reassessment

results in a level shift — but not necessarily a trend shift — in measures of horizontal equity.

That is, each reassessment better equalizes properties of similar assessed value, but it does not

seem to systematically alter assessment practices such that there are significant improvements to

reduce the variation of assessed values from the mean.

4.2 Heterogeneity in Assessment Quality Post-AVI

To evaluate how the quality of assessment changed over time for properties in more

disadvantaged communities, we break all the sales into multiple groups based on tract-level

characteristics. Specifically, we categorize all neighborhoods in Philadelphia by median income

(in quartiles), share of White residents (in quartiles), property value (in quartiles), majority race

23

(Black, White, and other),

13

and gentrification status (gentrifying, nongentrifying, and

nongentrifiable).

14

Figure 6 shows trends in the average COD across neighborhoods, suggesting that before

the AVI was implemented, tracts that were higher income, higher value, non-Black, and

gentrifying were more likely to have a higher COD, meaning tracts with these characteristics

were more likely to have less accurate value assessments. After the AVI, however, these trends

flip. Sales in lower-income, lower home value, majority-Black and nongentrifying tracts had

higher CODs than those in other neighborhoods; that is, tracts with these characteristics were

more likely to have less accurate assessed values after the AVI.

Although this correlative trend cannot be deemed a direct result of the implementation of

the AVI, the distinction in trends across groups may suggest that changes surrounding the AVI

had a particularly negative impact on assessment quality immediately following the policy’s

implementation for already vulnerable groups (i.e., homes in majority-Black, nongentrifying,

lower-home value, and lower-income tracts). Nonetheless, the gap in the average COD across

groups appears to be converging after the adoption of the AVI, especially in more recent years.

4.3 Vertical Equity

13

Based on data from the 2009–2013 5-year American Community Survey, tracts are categorized by tract majority

race, where a tract is majority White (47 percent of observations) if the population is more than 50 percent non-

Hispanic white, majority Black (35 percent of observations) if it is more than 50 percent Black (defined as Hispanic

Black or non-Hispanic Black), and other (18 percent of observations) if it is neither majority White nor majority

Black as they are defined above.

14

Ding and Hwang (2020) define a gentrifiable tract as one in which the median household income was below that

of the city in 2000, a gentrifying tract as one which is gentrifiable and experienced both (1) an increase in either its

median gross rent or median home value above the respective city average and (2) an increase in its share of college-

educated residents from 2000 to 2013 above the average city increase, and a nongentrifying tract as one that is

gentrifiable but does not satisfy both requirements to be considered gentrifying.

24

Philadelphia’s PRD in 2010 through 2013 was between 1.39 and 1.42, clearly above the

threshold of 1.03, indicating that assessments were highly regressive in the city (Table 1 and

Figure 3, bottom right panel). In other words, lower‐priced homes were systematically assessed

at a greater percent of their market value. The long period with no reassessments and disparities

in Great Recession–induced price crashes across submarkets should help explain such high levels

of regressivity. The differential effects of the Great Recession on the various submarkets could

also have exacerbated the quality of assessment. The PRD decreased to 1.28 in 2014, indicating a

marked improvement under the AVI, but it remained regressive. The 2019 reassessment

decreased the PRD further to 1.14, showing a continued mitigation of assessment inequity.

To put the results for Philadelphia into a comparative context, the 2013 PRD of the peer

cities ranges from 0.97 in Phoenix to 1.30 in Pittsburgh (Table 2). The PRD for Pittsburgh was

only slightly lower than that for Philadelphia, likely because these two cities are in the same

state, and it does not require regular revaluations. All cities in the control group had smaller

changes in their PRD from 2013 to 2014 than did Philadelphia, with a control group average

change of -0.009 (a maximum decrease of -0.051 in Columbus City and a maximum increase of

0.034 in Baltimore, compared with a decline of 0.081 in Philadelphia). Pittsburgh had almost no

change in its PRD (from 1.30 in 2013 to 1.31 in 2014). Philadelphia’s improvement in PRD

obviously outstripped any other city in the control group, most likely because of the adoption of

the AVI. Of course, assessment inequity in Philadelphia until 2014 was still more regressive than

most of the other cities.

Collectively, the above descriptive results using the most common equity measures

suggest there was some improvement in the vertical uniformity of the property tax system

25

following reassessment. Despite that improvement, vertical inequality remains significantly

above the acceptable level.

5. Impact of the AVI on Horizontal Equity: Regression Results

This section summarizes the regression results of the short-term impact of the AVI on

horizontal equity. The AVI’s effect is captured by the coefficient of the interaction variable

(PHIL

∗

POST), representing the change in the value of the corresponding outcome measure post-

AVI of a property in Philadelphia. As defined earlier, the control group consists of residential

property sales in our 15 comparison cities. None of these cities experienced significant changes

in their property tax systems during the study period (2012–2015). Based on the observations

only in Philadelphia, we further evaluate the disparate impact of the AVI on properties in

different types of neighborhoods.

5.1. Effects of AVI on Horizontal Equity of Assessments

As shown in Table 3, we find that the AVI led to a significant improvement in horizontal

equity in residential property assessments. The adoption of the AVI in Philadelphia leads to a

decrease of 11.0 percentage points in the COD for an average property.

15

In other words, the

average COD results confirm that, compared with cities without similar comprehensive changes

in their assessment system, the adoption of more regular reassessments generally makes

assessments more uniform across properties of similar values.

15

Results from the tract-level regressions are quite consistent with the property-level results, and the magnitude is

even larger.

26

When the outcome variable is the dummy of whether the COD of a sale is below 15

percent, the results are quite consistent: The probability of having a COD below 15 percent

increases by 25.8 percentage points after the adoption of the AVI. These results confirm that the

AVI not only helps improve average assessment accuracy but it also markedly improved the

proportion of properties with acceptably accurate assessment levels. When the assessment ratio

is used as the outcome variable, the results are quite consistent; the AVI helps improve

horizontal equity by bringing the assessment ratio closer to one.

5.2. Heterogeneity in AVI’s Effect on Horizontal Equity

In Table 4, we find that the impact of the AVI on horizontal equity varies significantly

across neighborhoods in Philadelphia. Overall, the results suggest the assessment ratio decreased

after the adoption of the AVI in disadvantaged neighborhoods (majority Black,

16

low-income,

lower property value neighborhoods, as well as lower-income nongentrifying neighborhoods).

All these suggest tax assessments became fairer across neighborhoods, as assessments in these

neighborhoods experienced smaller increases (or larger declines) relative to sales prices after the

adoption the AVI than those in other neighborhoods.

The improvement in the uniformity of assessments, however, was smaller in these more

disadvantaged neighborhoods: The improvement in CODs was much smaller in majority-Black,

low-income, or lower property value neighborhoods, relative to other neighborhoods. For

example, there was a larger variation of assessment values from sales prices in majority-Black

neighborhoods, and quality of assessments in those neighborhoods even became slightly worse

16

Note that here, tracts are categorized by the “majority Black,” or simply “Black,” binary variable, in which a tract

is Black (35 percent of observations) if it is more than 50 percent Black (defined as Hispanic Black or non-Hispanic

Black), and it is non-Black (65 percent of observations) if it is not majority Black as defined above.

27

post-AVI: The percent of sales with a COD below 15 percent decreased by 24.9 percentage

points in majority-Black neighborhoods relative to non-Black neighborhoods.

When we use yearly dummies instead of one POST dummy, the results confirm that the

uniformity in assessment, as measured by the COD, becomes relatively worse in majority-Black

neighborhoods, especially in the initial years after the AVI was adopted. The assessment ratio

and the COD in majority-Black neighborhoods experience a relatively larger increase

immediately after the adoption of the AVI (2014 and 2015) than in later years. This could be

partly explained by the generally larger variation of assessment among low-value properties.

This may also be attributed to the methodology, data reporting, or other aspects of the property

valuation practices that may affect the quality of property assessments. While property tax

horizontal uniformity has improved over time, the change in the COD in majority-Black

neighborhoods from the pre-AVI level was still significantly larger than that in majority-White

neighborhoods as of 2019 (by 22 percent). Similar patterns can be found for properties using

other measures of neighborhood disadvantages, such as lower-income neighborhoods, high-

minority neighborhoods, neighborhoods with lower property values, or nongentrifying

neighborhoods. It is concerning if such an assessment system makes low-income and

predominantly minority neighborhoods more vulnerable. More research is warranted regarding

additional interventions to mitigate potential disparate impacts of more frequent reassessment.

5.3. Effects of the AVI on Horizontal Equity of Property Owners’ Tax Burdens

In terms of the actual tax burden for property owners, compared with other cities, the

effective tax rate did not experience significant changes after the adoption of the AVI, as shown

28

in Table 3. This is consistent with the claim by the city government that the AVI is largely a

revenue-neutral policy.

However, the impact of the AVI on tax burdens varies significantly across neighborhoods

(Table 4). In fact, properties in majority-Black neighborhoods, high-minority neighborhoods,

low-income neighborhoods, and nongentrifying neighborhoods saw a larger decrease in their

effective tax rate relative to those in other more advantaged neighborhoods. Taken together with

the PRD results presented above, these results suggest the AVI generally makes property taxes

more equitable in Philadelphia. This is especially evident in the model using yearly dummies,

which suggests the effective tax rate declines over time post-AVI in majority-Black

neighborhoods relative to the non-Black ones (from -0.334 percentage point in 2014 to -0.753

percentage point in 2019). The results suggest that while property owners in less advantaged

neighborhoods experienced patterns of worsening uniformity of assessment, the improvement in

tax burden for property owners in the same neighborhoods continued even after the adoption of

the AVI.

In addition to improving the quality of assessments, the regressivity of the property tax

can also be mitigated by well-targeted tax relief programs. For example, the AVI was adopted

together with two major programs: one to mitigate tax increases for owner-occupied

homeowners (the Homestead Exemption program)

17

and one for long-term homeowners who

were likely to face sharp increases in property tax bills after the reassessments (the Longtime

Owner Occupants Program or LOOP). The Homestead Exemption program should make

property taxation more progressive, since the amount of the exemption is fixed regardless of the

value of the property; thus, homeowners of lower-value properties enjoy larger benefits from the

17

The Homestead Exemption program, the biggest single mitigation program, is available for all owner-occupied

primary residences in Philadelphia, regardless of the homeowner’s income or length of tenure in their residences.

29

program. In contrast, certain tax programs may increase the regressivity of property taxes. For

example, Philadelphia has an abatement program that was enacted in 1997, under which new

construction or major rehabilitation projects are entitled to a 10-year tax abatement on the value

of the newly constructed or rehabilitated improvements.

6. Conclusion

Despite decades of property tax revolts, local governments continue to rely heavily on

property taxes. Property assessment, however, is a complex and constantly evolving field and

there has been no consensus on whether property values should be regularly reassessed to assure

the equity of the real property tax. In practice, many U.S. states do not mandate regular

revaluation cycles — at least not short, regular cycles. During long intervals between

assessments, property values in urban centers diverge widely: Those in wealthy districts and

prime locations appreciate quickly, whereas those in poor districts and less desirable locations

rise very little, if at all. Recessions could also exacerbate the quality of overall property

assessment when assessments do not keep up with sharper declines in property values in harder-

hit areas. Thus, taxes that are levied at the same rate but are based on outdated valuations may

hurt low-income homeowners.

The empirical results show generally positive evidence of regular revaluations, although

impacts appear to vary across neighborhood types. The quality of assessments in Philadelphia, as

measured by the COD, improves significantly after the revaluation in 2014. The tax burden for

properties in less advantaged neighborhoods was also reduced after the AVI was introduced,

although an alternative vertical equity measure presents mixed results. These results highlight the

importance of regular reassessment in cities experiencing significant increases in property values

30

(i.e., gentrification) and shed light on the disparate impacts that reassessment might have across

income, property value, race, and gentrification.

While our findings suggest that more regular reassessments do improve vertical and

horizontal equity, such a program does not address all the challenges of property assessment or

property tax administration. The quality of assessment of Philadelphia properties, although

significantly improved post-AVI, is still far above the acceptable threshold. This could be

explained by variations in assessment methodologies or issues related to quality control, data

collection, and data cleaning for property transactions.

Discussions of city- and state-level revaluation policy changes have been in the works for

some time. At the national level, regular revaluation of properties has been required by the real

property tax law in most states. At the state level, a 2010 study of county assessment practices in

Pennsylvania recommended that the Pennsylvania General Assembly consolidate property

assessment law into a uniform statewide system and require more frequent reassessment at an

interval of four years (Weber et al., 2010). Such changes could not only improve assessment

quality and equity across all counties in Pennsylvania but also lower the administrative costs of

reassessment, simplify processes to mitigate human error, and comply with the state

constitution’s uniformity clause.

At the city level, the Philadelphia City Council recommended in 2019 that the OPA

overhaul its leadership, partner with private firms to increase assessment accuracy and appraisal

services, and reform its quality control methods (Clarke, 2019). The Office of the Controller also

advised that OPA targets its efforts on the geographic areas that are most disproportionately tax

burdened — North, Southwest, and West Philadelphia (Rhynhart, 2019). It also recommended

readdressing land valuations, improving the transparency of assessment methods, and examining

31

the true impact of the current tax exemptions and abatements aimed to protect vulnerable

homeowners. The city also hired consultants in 2019 to evaluate the city’s property assessment

system (J.F. Ryan Associates, Inc., 2018). Based on recommendations from the evaluation, the

city initially planned to implement a new assessment system in 2020, which has been delayed

because of the COVID-19 crisis. Approaches such as these city- and state-level policy proposals

may help fill the equity gaps that the AVI hasn’t managed to mitigate in Philadelphia’s property

tax system.

This paper provides updated evidence on the equity effects (horizontal and vertical) of

property revaluation on the distribution of the tax burden among owners along the income

spectrum after a long lapse in reassessments. The paper makes the case that the real property tax

can be well maintained as an effective tax instrument, although other practices or tax relief

programs might be necessary to ensure an equitable impact. Despite conventional taxation theory

holding equity and efficiency as tradeoffs, the evidence presented supports the idea that equity

and efficiency can improve in unison, such that each reinforces the other through more frequent,

regular property tax reassessments. As a case study, this empirical research contributes to

debates on the design of property taxation systems. The results can help researchers and

policymakers understand the complicated relationship between property sales, assessments, and

property taxes.

32

References

Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations (ACIR) 1987. Changing Attitudes on

Governments and Taxes. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office.

Alm, J., Hawley, Z., Lee, J.M., Miller, J.J., 2016. Property Tax Delinquency and Its Spillover

Effects on Nearby Properties,” Regional Science and Urban Economics, 58: pp. 71–7.

Alm, J., Hodge, T.R., Sands, G., Skidmore, M., 2014. “Detroit Property Tax Delinquency: Social

Contract in Crisis,” Public Finance and Management, 14(3): pp. 280–305.

Almy, R.R., International Association of Assessing Officers, 1978. Improving Real Property

Assessment: A Reference Manual. Chicago: The Association.

Anderson N.B., Dokko, J.K., 2016. “Liquidity Problems and Early Payment Default Among

Subprime Mortgages,” Review of Economics and Statistics, 98(5): pp. 897–912.

Bell, E.J., 1984. “Administrative Inequity and Property Assessment: The Case for the Traditional

Approach,” Property Tax Journal, 3: pp. 123–31.

Berry, C., Schmidt, M., Langowski, E., Wang, X., Rockower, J., 2021. Property Tax Fairness

from the Center of Municipal Finance, Harris School of Public Policy, University of

Chicago. Available at propertytaxproject.uchicago.edu/.

Bowman, J.H., Mikesell, J.L., 1990. “Improving Administration of the Property Tax: A Review

of Prescriptions and Their Impacts,” Public Budgeting and Financial Management, 2(2): pp.

151–76.

Cabral, M., Hoxby, C., 2012. “The Hated Property Tax Salience, Tax Rates, and Tax Revolts,”

NBER Working Paper No. 18514.

Carter, J.M., 2016. “Methods for Determining Vertical Inequity in Mass Appraisal,” Fair &

Equitable, 14(6): pp. 3–8.

Cheng, P.L., 1974. “Property Taxation, Assessment Performance, and Its Measurement,” Public

Finance, 29: pp. 268–84.

Clarke, D.L., 2019. “Council Releases Recommendations for Property Assessment,”

Philadelphia City Council. Available at phlcouncil.com/council-releases-recommendations-

for-property-assessment-reforms-following-independent-audit/.

Deboer, L., Conrad, J., 1988. “Do High Interest Rates Encourage Property Tax Delinquency?”

National Tax Journal, 41(4): pp. 555–60.

Ding, L., Hwang, J., 2020. “Effects of Gentrification on Homeowners: Evidence from a Natural

Experiment,” Discussion paper, Community Development and Regional Outreach, Federal

Reserve Bank of Philadelphia.

Dowdall, E., 2015. The Actual Value Initiative: Philadelphia’s Progress on Its Property Tax

Overhaul, Philadelphia: The Pew Charitable Trusts. Available at

www.pewtrusts.org/~/media/assets/2015/09/philadelphia-avi-update-brief.pdf.

33

Dowdall, E., Warner, S., 2012. The Actual Value Initiative: Overhauling Property Taxes in

Philadelphia, Philadelphia: The Pew Charitable Trusts. Available at

www.pewtrusts.org/~/media/legacy/uploadedfiles/

wwwpewtrustsorg/reports/philadelphia_research_initiative/philadelphiapropertytaxespdf.pdf.

Eom, T.H., 2008. “A Comprehensive Model of Determinants of Property Tax Assessment

Quality: Evidence in New York State,” Public Budgeting and Finance, 28(1): pp. 58–81.

Ferreira, F., Gyourko, J., 2009. “Do Political Parties Matter? Evidence from U.S.

Cities,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 124(1): pp. 399–422.

Fisher, G.W., 1996. The Worst Tax? A History of the Property Tax in America. Lawrence, KS:

University Press of Kansas.

Geraci, V.J., 1977. “Measuring the Benefits from Property Tax Assessment Reform,” National

Tax Journal, 30: pp. 195–205.

Gillen, K.C., 2008. “Updated Results on Property Assessment Accuracy, Uniformity and Equity

in Philadelphia,” Econsult Corporation. Available at

media.philly.com/documents/taxproj07gillen08.pdf.

Gloudemans, R.J., 1999. Mass Appraisal of Real Property. Chicago: International Association of

Assessing Officers.

Higginbottom, J., 2010. State Provisions for Property Reassessment. Washington, D.C.: Tax

Foundation.

International Association of Assessing Officers, 2013. Standard on Ratio Studies. Kansas City,

MO: IAAO.

J.F. Ryan Associates, Inc., 2018. Council of the City of Philadelphia – 2019 Property Assessment

Audit. Newburyport, MA: J.F. Ryan Associates, Inc.

Jensen, J.P., 1931. Property Taxation in the United States. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kochin, L.A., Parks, R.W., 1982. "Vertical Equity in Real Estate Assessment: A Fair

Appraisal?” Economic Inquiry, 20: pp. 511–32.

Langley, A.H., 2018. “Improving the Property Tax by Expanding Options for Monthly

Payments,” Lincoln Institute of Land Policy Working Paper No. 18AL1.

McMillen, D., 2013. “The Effect of Appeals on Assessment Ratio Distributions: Some

Nonparametric Approaches,” Real Estate Economics, 41(1): pp. 165–91.

McMillen, D., Singh, R., 2020. “Assessment Regressivity and Property Taxation,” Journal of

Real Estate Finance and Economics, 60: 155–69.

Mikesell, J.L., 1980. “Property Tax Reassessment Cycles: Significance for Uniformity and

Effective Rates,” Public Finance Quarterly, 8(1): pp. 23–37.

Miller, J.J., 2012. The Cost of Delinquent Property Tax Collection. University of Illinois at

Chicago: Dissertation.

34

Montarti, E., Weaver, E., 2007. Pennsylvania’s Property Assessment System Needs Change,

Pittsburgh: Allegheny Institute for Public Policy, Report No. 07-07.

O’Flaherty, B., 1990. “The Option Value of Tax Delinquency: Theory,” Journal of Urban

Economics, 28(03): pp. 287–317.

Paglin, M., Fogarty, M., 1972. “Equity and the Property Tax: A New Conceptual Focus,”

National Tax Journal, 25: pp. 557–66.

Property Assessment Reform Task Force, 2018. “Pennsylvania Property Assessment: A Self-

Evaluation Guide for County Officials,” Pennsylvania Local Government Commission.

Rhynhart, R., 2019. “The Accuracy and Fairness of Philadelphia’s Property Assessments,”

Office of the Controller. Available at controller.phila.gov/philadelphia-audits/property-

assessment-review/.

Simonsen, B., Robbins, M.D., Helgerson, L., 2001. “The Influence of Jurisdiction Size and Sale

Type on Municipal Bond Interest Rates: An Empirical Analysis,” Public Administration

Review, 61(6): pp. 709–17.

Sternlieb, G., 1972. The Urban Housing Dilemma. New York: Housing and Development

Administration.

Sternlieb, G., Lake, R.W., 1976. “The Dynamics of Real Estate Tax Delinquency,” National Tax

Journal, 29(3): pp. 261–71.

Sunderman, M., Birch, J., Cannaday, R., Hamilton, T., 1990. “Testing for Vertical Inequity in

Property Tax Systems,” Journal of Real Estate Research, 5(3): pp. 319–34.

Swierenga, R.P., 1976. Acres for Cents: Delinquent Tax Auctions in Domestic Iowa. Westport,

CT: Greenwood Press.

Waldhart, P., Reschovsky, A., 2012. “Property Tax Delinquency and the Number of Payment

Installments,” Public Finance and Management, 12(4): pp. 316–30.

Weber, J.A., Scott, L., Andersen, C., Dakouri, M., et al., 2010. Pennsylvania County Property

Reassessment: Impact on Local Government Finances and the Local Economy, Harrisburg,

PA: The Center for Rural Pennsylvania. Available at

www.rural.palegislature.us/county_reassessment_2010.pdf.

Whitaker, S., Fitzpatrick, T.J., 2013. “Deconstructing Distressed-Property Spillovers: The

Effects of Vacant, Tax-Delinquent, and Foreclosed Properties in Housing

Submarkets,” Journal of Housing Economics, 22(2): pp. 79–91.

35

Figure 1: Mean Sales Prices and Mean Assessments of Single-Family Residential Properties in Philadelphia, 2010–2019

Source: Authors’ calculations using data on property assessments, tax payment history, and sales transactions from the City of Philadelphia’s Department of Revenue, Department

of Records, and Office of Property Assessment.

36

Figure 2. Philadelphia Coefficient of Dispersion (COD) Distribution in 2013, 2014, and 2019

Source: Authors’ calculations using data on property assessments, tax payment history, and sales transactions from the City of Philadelphia’s Department of Revenue, Department

of Records, and Office of Property Assessment.

37

Figure 3: Mean Assessment Ratio, Coefficient of Dispersion, Effective Tax Rate, and Price-Related Differential, Philadelphia

Source: Authors’ calculations using data on property assessments, tax payment history, and sales transactions from the City of Philadelphia’s Department of Revenue, Department

of Records, and Office of Property Assessment.

38

Figure 4: Measures of Horizontal Equity and Vertical Equity, Philadelphia vs. Control Group of Cities, 2012–2015

Source: Authors’ calculations using data on property assessments, tax payment history, and sales transactions from the City of Philadelphia’s Department of Revenue, Department

of Records, and Office of Property Assessment, and national control city data from CoreLogic Solutions.

39

Figure 5. Average Coefficient of Dispersion (COD) in Philadelphia by Neighborhood in 2013, 2014, and 2019

Source: Authors’ calculations using data on property assessments, tax payment history, and sales transactions from the City of Philadelphia’s Department of Revenue, Department

of Records, and Office of Property Assessment, and U.S. Census TIGER/Line Shapefiles.

40

Figure 6. Coefficient of Dispersion (COD) Trends by Neighborhood Characteristics

Source: Authors’ calculations using data on property assessments, tax payment history, and sales transactions from the City of Philadelphia’s Department of Revenue, Department

of Records, and Office of Property Assessment, and 2009-2013 American Community Survey data.

41

Table 1: Descriptive Statistics for Sales in Philadelphia

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9)

Year

# of

Sales

Mean

Sale

Price

Mean

Assessm

ent

Mean

Tax

Amount

Mean

AR

Mean

COD

Percent

COD

< 15%

PRD

Mean

Effective

Tax

Rate

2010 12,596 $137,884 $51,640 $1,179 0.53 0.57 0.07 1.42 1.34%

2011 11,363 $133,575 $53,694 $1,329 0.56 0.54 0.09 1.39 1.55%

2012 12,029 $140,307 $55,774 $1,413 0.56 0.55 0.07 1.41 1.61%

2013 13,381 $145,997 $57,369 $1,492 0.55 0.55 0.08 1.39 1.62%

2014 13,517 $165,434 $154,299 $1,655 1.19 0.41 0.33 1.28 1.41%

2015 15,756 $164,414 $149,106 $1,622 1.15 0.40 0.33 1.27 1.35%

2016 18,455 $172,862 $148,670 $1,679 1.08 0.38 0.34 1.25 1.31%

2017 20,040 $187,057 $148,588 $1,694 0.99 0.36 0.31 1.25 1.19%

2018 20,102 $196,348 $147,089 $1,700 0.91 0.36 0.25 1.22 1.11%

2019 18,932 $202,013 $161,284 $1,855 0.91 0.32 0.29 1.14 1.06%

Source: Authors’ calculations using data on property assessments, tax payment history, and sales transactions from the City of

Philadelphia’s Department of Revenue, Department of Records, and Office of Property Assessment.

Table 2: Descriptive Statistics in Philadelphia and Peer Cities

Total Sales Mean Sales Mean Assessment Mean AR Mean COD

Pct COD

Below 15%

PRD

Mean

Effective Tax

Rate

2013

2014

2013

2014

2013

2014

2013

2014

2013

2014

2013

2014

2013

2014

2013

2014

Philadelphia 13,381 13,517 $145,997 $165,434 $57,369 $154,299 0.55 1.19 0.55 0.41 0.08 0.33 1.39 1.28 1.62% 1.41%

Baltimore 8,144 5,629 $153,624 $138,851 $149,504 $131,912 1.26 1.27 0.52 0.54 0.25 0.21 1.29 1.34 2.95% 2.93%

Charlotte 15,196 13,828 $209,967 $226,544 $197,080 $195,958 1.05 0.96 0.26 0.24 0.50 0.49 1.12 1.11 1.37% 1.27%

Columbus 17,731 13,084 $135,482 $148,748 $134,761 $141,799 1.24 1.13 0.40 0.30 0.41 0.48 1.24 1.18 2.78% 3.25%

Dallas 12,505 9,420 $263,046 $263,703 $230,791 $226,348 0.94 0.89 0.24 0.23 0.42 0.41 1.07 1.04 2.54% 2.43%

Denver 12,336 10,038 $332,432 $368,169 $274,531 $276,218 0.84 0.76 0.21 0.27 0.40 0.22 1.02 1.01 0.58% 0.52%

El Paso 4,273 2,833 $150,385 $148,010 $149,543 $145,510 1.06 1.04 0.21 0.20 0.54 0.53 1.07 1.06 3.40% 2.86%

Fort Worth 11,301 5,825 $165,997 $159,691 $150,785 $137,366 0.96 0.90 0.20 0.21 0.53 0.49 1.06 1.05 2.77% 2.60%

Houston 25,053 24,668 $238,696 $254,692 $207,874 $226,551 0.93 0.94 0.22 0.22 0.45 0.46 1.07 1.05 2.56% 2.52%

Oklahoma City 11,893 12,047 $147,955 $157,418 $141,558 $156,444 1.07 1.09 0.25 0.19 0.59 0.75 1.11 1.09 1.29% 1.25%

Phoenix 29,385 17,531 $206,105 $215,219 $113,231 $124,470 0.53 0.57 0.48 0.44 0.03 0.03 0.97 0.98 0.72% 0.70%

Pittsburgh 3,508 3,154 $142,009 $160,418 $116,743 $125,583 1.07 1.03 0.40 0.39 0.28 0.26 1.30 1.31 2.55% 2.09%

Portland 11,242 10,210 $331,552 $348,896 $296,005 $324,654 0.94 0.97 0.18 0.17 0.51 0.58 1.05 1.04 1.34% 1.30%

San Antonio 14,543 9,333 $174,423 $194,937 $158,143 $174,734 0.95 0.93 0.21 0.20 0.50 0.52 1.04 1.04 2.50% 2.43%

Seattle 10,358 8,129 $473,597 $512,510 $371,149 $389,338 0.83 0.79 0.25 0.25 0.26 0.22 1.06 1.04 0.97% 0.87%

Washington, D.C. 6,862 5,331 $546,066 $546,573 $449,642 $450,541 0.88 0.87 0.24 0.23 0.38 0.39 1.07 1.05 0.76% 0.68%