D

E

P

A

O

T

M

E

N

T

F

T

H

E

A

R

M

Y

•

•

E

U

N

I

T

E

D

S

T

A

T

S

O

A

F

A

M

E

R

I

C

R

T

H

I

S

W

E

'

L

L

D

E

F

E

N

D

Joint Publication 3-16

Multinational Operations

01 March 2019

Validated on 12 February 2021

i

PREFACE

1. Scope

This publication provides fundamental principles and guidance for the Armed Forces

of the United States when they operate as part of a multinational (coalition or allied) force.

It addresses operational considerations for the commander and staff to plan, execute, and

assess multinational operations.

2. Purpose

This publication has been prepared under the direction of the Chairman of the Joint

Chiefs of Staff (CJCS). It sets forth joint doctrine to govern the activities and performance

of the Armed Forces of the United States in joint operations, and it provides considerations

for military interaction with governmental and nongovernmental agencies, multinational

forces, and other interorganizational partners. It provides military guidance for the exercise

of authority by combatant commanders and other joint force commanders (JFCs), and

prescribes joint doctrine for operations and training. It provides military guidance for use

by the Armed Forces in preparing and executing their plans and orders. It is not the intent

of this publication to restrict the authority of the JFC from organizing the force and

executing the mission in a manner the JFC deems most appropriate to ensure unity of effort

in the accomplishment of objectives.

3. Application

a. Joint doctrine established in this publication applies to the Joint Staff, commanders

of combatant commands, subordinate unified commands, joint task forces, subordinate

components of these commands, the Services, and combat support agencies.

b. This doctrine constitutes official advice concerning the enclosed subject matter;

however, the judgment of the commander is paramount in all situations.

c. If conflicts arise between the contents of this publication and the contents of Service

publications, this publication will take precedence unless the CJCS, normally in

coordination with the other members of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, has provided more current

and specific guidance. Commanders of forces operating as part of a multinational (alliance

or coalition) military command should follow multinational doctrine and procedures

Preface

ii JP 3-16

ratified by the United States. For doctrine and procedures not ratified by the United States,

commanders should evaluate and follow the multinational command’s doctrine and

procedures, where applicable and consistent with US law, regulations, and doctrine.

For the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff:

DANIEL J. O’DONOHUE

Lieutenant General, USMC

Director, Joint Force Development

iii

SUMMARY OF CHANGES

REVISION OF JOINT PUBLICATION 3-16

DATED 16 JULY 2013

• This publication was validated without change on 12 February 2021

• Removes and replaces Range of Military Options to a Competition Continuum.

• Updates and cleans up graphics throughout the joint publication (JP).

• Updates several of the quotes and examples throughout the JP.

• Terminology and acronyms updated to current lexicon.

• Utilizes “national” vice “political” will and decisions throughout.

• Updated out of date reference Internet links.

• ‘Stability operations’ changed to ‘stability activities’.

• Emphasized Joint Electromagnetic Spectrum Management Operations.

• Enhanced the Multinational Logistic section.

• Enhanced the Transition to Multinational Operations section.

• Updates Appendix A, “Planning Considerations Checklist.”

• Updates Appendix B, “Multinational Planning Augmentation Team.”

• Updates Appendix C, “Multinational Strategy and Operations Group.”

• Adds Appendix D, “Multinational Logistics.”

• Adds Appendix E, “Commander's Checklist for Logistics in Support of

Multinational Operations.”

• Includes “Counter Threat Networks” under “Other Multinational Operations.”

Summary of Changes

iv JP 3-16

Intentionally Blank

v

TABLE OF CONTENTS

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................. viii

CHAPTER I

FUNDAMENTALS OF MULTINATIONAL OPERATIONS

Multinational Operations Overview ........................................................................... I-1

Strategic Context ......................................................................................................... I-1

Nature of Multinational Operations ............................................................................ I-2

Security Cooperation .................................................................................................. I-5

Security Cooperation Considerations ......................................................................... I-6

Rationalization, Standardization, and Interoperability ............................................... I-8

CHAPTER II

COMMAND AND COORDINATION RELATIONSHIPS

Command Authority ..................................................................................................II-1

Unified Action ...........................................................................................................II-2

Multinational Force Commander ...............................................................................II-4

Overview of Multinational Command Structures ......................................................II-4

Multinational Command Structures ...........................................................................II-8

Multinational Force Coordination ..............................................................................II-9

Control of Multinational Operations ........................................................................II-17

Interorganizational Cooperation ..............................................................................II-18

CHAPTER III

GENERAL PLANNING CONSIDERATIONS

Diplomatic and Military Considerations .................................................................. III-1

Building and Maintaining a Multinational Force..................................................... III-3

Mission Analysis and Assignment of Tasks ............................................................ III-5

Language, Religion, Culture, and Sovereignty ........................................................ III-6

Legal ........................................................................................................................ III-8

Doctrine and Training ............................................................................................ III-10

Funding and Resources .......................................................................................... III-10

Protection of Personnel, Information, and Critical Assets ..................................... III-11

Rules of Engagement ............................................................................................. III-12

Combat Identification and Friendly Fire Prevention ............................................. III-13

CHAPTER IV

OPERATIONS

Land Operations ....................................................................................................... IV-1

Maritime Operations ................................................................................................ IV-3

Air Operations .......................................................................................................... IV-4

Space Operations ..................................................................................................... IV-7

Table of Contents

vi JP 3-16

Information .............................................................................................................. IV-8

Cyberspace Operations .......................................................................................... IV-10

CHAPTER V

OTHER MULTINATIONAL OPERATIONS

Stability Activities .................................................................................................... V-1

Special Operations .................................................................................................... V-2

Joint Electromagnetic Spectrum Management Operations ....................................... V-2

Noncombatant Evacuation Operations ..................................................................... V-4

Foreign Humanitarian Assistance Operations .......................................................... V-5

Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction ............................................................... V-7

Counterdrug Operations ............................................................................................ V-8

Countering Threat Networks ..................................................................................... V-8

Personnel Recovery .................................................................................................. V-9

CHAPTER VI

OTHER CONSIDERATIONS

Assessment ............................................................................................................... VI-1

Intelligence ............................................................................................................... VI-1

Information Sharing ................................................................................................. VI-5

Communications ...................................................................................................... VI-9

Joint Fires ............................................................................................................... VI-11

Host-Nation Support .............................................................................................. VI-11

Civil Affairs Operations ......................................................................................... VI-13

Health Services ...................................................................................................... VI-14

Personnel Support .................................................................................................. VI-14

Public Affairs ......................................................................................................... VI-15

Multinational Logistics .......................................................................................... VI-16

Meteorology and Oceanography ............................................................................ VI-20

Environmental ........................................................................................................ VI-21

Transitions.............................................................................................................. VI-22

Multinational Communications Integration ........................................................... VI-25

APPENDIX

A Planning Considerations Checklist ............................................................ A-1

B Multinational Planning Augmentation Team .............................................B-1

C Multinational Strategy and Operations Group ...........................................C-1

D Multinational Logistics ............................................................................. D-1

E Commander’s Checklist for Logistics in Support of

Multinational Operations ............................................................................ E-1

F Points of Contact ........................................................................................ F-1

G References ................................................................................................. G-1

H Administrative Instructions ....................................................................... H-1

Table of Contents

vii

GLOSSARY

Part I Abbreviations, Acronyms, and Initialisms .............................................. GL-1

Part II Terms and Definitions ............................................................................. GL-5

FIGURE

I-1 Notional Competition Continuum ............................................................... I-3

II-1 Notional Multinational Command Structure ..............................................II-1

II-2 Notional Coalition Command and Control Structure ................................ II-4

II-3 Integrated Command Structure ..................................................................II-6

II-4 Lead Nation Command Structure ...............................................................II-6

II-5 Parallel Command Structure ......................................................................II-7

II-6 Coalition Command Relationships for Operation

Desert Storm (Land Forces) .....................................................................II-10

II-7 Order of Battle ..........................................................................................II-13

II-8 International Security Assistance Force Coalition

Command Relationships ..........................................................................II-14

II-9 Stabilization Force Coalition Command Relationships ...........................II-15

II-10 European Forces Coalition Command Relationships ...............................II-16

III-1 Factors Affecting the Military Capabilities of Nations ............................ III-2

III-2 Partner Nation Contributions ................................................................... III-4

IV-1 Multinational Force Land Component Commander

Notional Responsibilities ......................................................................... IV-2

IV-2 Multinational Force Maritime Component Commander

Notional Responsibilities ......................................................................... IV-4

IV-3 Multinational Force Air Component Commander

Notional Responsibilities ......................................................................... IV-5

V-1 Multinational Force Special Operations Component

Commander Notional Responsibilities ...................................................... V-3

VI-1 Multinational Intelligence Principles ....................................................... VI-2

VI-2 Notional Transitions of Authority .......................................................... VI-25

VI-3 Multinational Communication Integration ............................................. VI-26

B-1 Multinational Planning Augmentation Team

Augmentation Roles ...................................................................................B-2

D-1 Logistics Principles of Multinational Operations ...................................... D-2

D-2 United States and North Atlantic Treaty Organization

Classes of Supply .................................................................................... D-11

D-3 Illustrative Multinational Joint Logistic Center Structure ....................... D-15

D-4 Illustrative Logistic Command and Control

Organization: Alliance-Led ..................................................................... D-17

D-5 Illustrative Logistic Command and Control Organization:

United States-Led Multinational Operation ............................................ D-18

D-6 Illustrative Logistic Command and Control Organization:

United Nations-Commanded Multinational Operation ........................... D-20

Table of Contents

viii JP 3-16

Intentionally Blank

ix

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

COMMANDER’S OVERVIEW

• Describes the strategic context for multinational operations

• Discusses the nature and tenets of multinational operations

• Describes how security cooperation provides ways and means to help achieve

national security and foreign policy objectives

• Outlines command and coordination relationships within national and

multinational chains of command

• Discusses diplomatic and military considerations related to building and

maintaining a multinational force

• Describes how language, religion, culture, and sovereignty considerations

effect planning for multinational operations

• Outlines how land, maritime, air, space, information, and cyberspace

operations are conducted in a multinational context

Fundamentals of Multinational Operations

Multinational operations are conducted by forces of

two or more nations, usually undertaken within the

structure of a coalition or alliance. Other possible

arrangements include supervision by an

international organization such as the United

Nations, North Atlantic Treaty Organization

(NATO), or Organization for Security and

Cooperation in Europe.

Strategic Context

Nations form regional and global geopolitical and

economic relationships to promote their mutual

national interests, ensure mutual security against

real and perceived threats, conduct foreign

humanitarian assistance (FHA), conduct peace

operations, and promote their ideals. Cultural,

diplomatic, psychological, economic,

technological, and informational factors all

influence multinational operations and

participation. However, a nation’s decision to

Executive Summary

x JP 3-16

employ military capabilities is always a political

decision.

Nature of Multinational

Operations

The tenets of multinational operations are respect,

rapport, knowledge of partners, patience, mission

focus, team-building, trust, and confidence. While

these tenets cannot guarantee success, ignoring

them may lead to mission failure due to a lack of

unity of effort. National and organizational norms

of culture, language, and communication affect

multinational force (MNF) interoperability.

Security Cooperation

US national and Department of Defense strategic

guidance emphasizes the importance of defense

relationships with allies and partner nations (PNs)

to advance national security objectives, promote

stability, prevent conflicts, and reduce the risk of

having to employ US military forces in a conflict.

Security cooperation (SC) activities are likely to be

conducted in a combatant command’s daily

operations. SC advances progress toward

cooperation within the competition continuum by

strengthening and expanding the existing network

of US allies and partners, which improves the

overall warfighting effectiveness of the joint force

and enables more effective multinational

operations.

Rationalization, Standardization,

and Interoperability

International rationalization, standardization, and

interoperability with PNs is important for achieving

practical cooperation; efficient use of research,

development, procurement, support, and production

resources; and effective multinational capability

without sacrificing US capabilities.

Command and Coordination Relationships

Command Authority

Although nations will often participate in

multinational operations, they rarely, if ever,

relinquish national command of their forces. As

such, forces participating in a multinational

operation will always have at least two distinct

chains of command: a national chain of command

and a multinational chain of command.

National Command. As Commander in Chief, the

President always retains and cannot relinquish

Executive Summary

xi

national command authority over US forces.

National command includes the authority and

responsibility for organizing, directing,

coordinating, controlling, planning employment of,

and protecting military forces.

Multinational Command. Command authority for

a multinational force commander (MNFC) is

normally negotiated between the participating

nations and can vary from nation to nation. In

making a decision regarding an appropriate

command relationship for a multinational military

operation, the President carefully considers such

factors as mission, size of the proposed US force,

risks involved, anticipated duration, and rules of

engagement. Command authority will be specified

in the implementing agreements that provide a clear

and common understanding of what authorities are

specified over which forces.

Unified Action

Unified action during multinational operations

involves the synergistic application of all

instruments of national power as provided by each

participating nation; it includes the actions of

nonmilitary organizations as well as military forces.

Multinational Force Commander

MNFC is a generic term applied to a commander

who exercises command authority over a military

force composed of elements from two or more

nations. The extent of the MNFC’s command

authority is determined by the participating

nations or elements.

Overview of Multinational

Command Structures

No single command structure meets the needs of

every multinational command, but national

considerations will heavily influence the ultimate

shape of the command structure.

The basic structures for multinational operations fall

into one of three types: integrated, lead nation (LN),

or parallel command.

Integrated Command Structure. A good

example of this command structure is in NATO,

where a strategic commander is designated from

a member nation, but the strategic command

staff and the commanders and staffs of

Executive Summary

xii JP 3-16

subordinate commands are of multinational

makeup.

LN Command Structure. An LN structure

exists when all member nations place their

forces under the control of one nation. The LN

command structure can be distinguished by a

dominant LN command and staff arrangement

with subordinate elements retaining strict

national integrity.

Parallel Command Structures. Under a

parallel command structure, no single force

commander is designated. The MNF leadership

must develop a means for coordination among

the participants to achieve unity of effort. This

can be accomplished through the use of

coordination centers. Nonetheless, because of

the absence of a single commander, the use of a

parallel command structure should be avoided,

if at all possible.

Interorganizational Cooperation

In many operational environments, the MNF

interacts with a variety of stakeholders requiring

unified action by the MNFC, including nonmilitary

governmental departments and agencies,

international organizations, and nongovernmental

organizations (NGOs). Interorganizational

cooperation includes the coordination between the

Armed Forces of the United States; US

Government departments and agencies; state,

territorial, local, and tribal government agencies;

foreign military forces and government agencies;

international organizations; NGOs; and the private

sector.

General Planning Considerations

Diplomatic and Military

Considerations

The composition of an MNF may change as partners

enter and leave when their respective national

objectives change or force contributions reach the

limits of their nation’s ability to sustain them. Some

nations may even be asked to integrate their forces

with those of another, so that a contribution may, for

example, consist of an infantry company containing

platoons from different countries. The only

constant is that a decision to “join in” is, in every

Executive Summary

xiii

case, a calculated diplomatic decision by each

potential member of a coalition or alliance. The

nature of their national decisions, in turn, influences

the multinational task force’s (MNTF’s) command

structure.

Numerous factors influence the military capabilities

of nations. The operational-level commander must

be aware of the specific operational limitations and

capabilities of the forces of participating nations and

consider these differences when assigning missions

and conducting operations. MNTF commanders at

all levels may be required to spend considerable

time consulting and negotiating with diplomats,

host nation (HN) officials, local leaders, and others;

their role as diplomats should not be

underestimated.

Building and Maintaining a

Multinational Force

Building an MNF starts with the national decisions

and diplomatic efforts to create a coalition or spur

an alliance into action. Discussion and coordination

between potential participants will initially seek to

sort out basic questions at the national strategic

level.

Mission Analysis and Assignment

of Tasks

The MNFC’s staff should conduct a detailed

mission analysis. This is one of the most important

tasks in planning multinational operations and

should result in a revised mission statement,

commander’s intent, and the MNFC’s planning

guidance. As part of the mission analysis, force

requirements should be identified; standards for

participation published (e.g., training-level

competence and logistics, including deployment,

sustainment, and redeployment capabilities); and

funding requests, certification procedures, and force

commitments solicited from an alliance or likely

coalition partners.

Language, Religion, Culture, and

Sovereignty

Differing languages within an MNF may present

a significant challenge to command, control, and

communications and potentially affect unity of

effort if not mitigated. US forces cannot assume

the predominant language will automatically be

English, and specifying an official language for the

MNF can be a sensitive issue. Therefore, US forces

Executive Summary

xiv JP 3-16

should make every effort to overcome language

barriers.

Religion. Each partner in multinational operations

requires the capability to assess the impact of

religion upon operations. Assigned religious affairs

personnel serve as general planning considerations

advisers to the command regarding religious factors

among the local population, as well as assigned,

attached, or authorized personnel.

Culture. Each partner in multinational operations

possesses a unique cultural identity—the result of

their physical environment, economic, political, and

social outlook, as well as the values, beliefs, and

symbols that comprise their culture. Commanders

should strive to accommodate religious and cultural

customs, holiday observances, and similar concerns

of MNF members.

Sovereignty Issues. Sovereignty issues will be

among the most difficult problems the MNFC may

be required to mitigate. Often, the MNFC will be

required to accomplish the mission through

coordination, communication, and consensus, in

addition to traditional command concepts. National

sensitivities must be recognized and acknowledged.

Operations

Land Operations

In most multinational operations, land forces are an

integral and central part of the military effort. The

level and extent of land operations in a multinational

environment is largely a function of the overall

military objectives, any national caveats to

employment, and the forces available within the

MNF.

National doctrine and training will normally dictate

employment options within the MNF. Nations with

common tactics, techniques, and procedures will

also experience far greater interoperability.

Effective use of SC activities may significantly

reduce interoperability problems even for countries

with widely disparate weapons systems.

Executive Summary

xv

Maritime Operations

During multinational operations, maritime forces

can exercise sea control or project power ashore,

synchronize their operations with the other MNF

components, and support the MNFC’s intent and

guidance in accomplishing the MNF mission.

Maritime forces are primarily navies and coast

guard; however, they may include maritime-

focused air forces, amphibious forces, or other

government departments and agencies charged with

sovereignty, security, or constabulary functions at

sea.

Air Operations

Air operations provide the MNFC with a

responsive, agile, and flexible means of operational

reach. The MNFC can execute deep operations

rapidly, striking at decisive points and attacking

centers of gravity. Further, transportation and

support requirements can be greatly extended in

response to emerging crisis and operational needs.

Multinational air operations are focused on

supporting the MNFC’s intent and guidance in

accomplishing the MNTF mission and, at the same

time, ensuring air operations are integrated with the

other major MNF operational functions (land,

maritime, and special operations forces).

Space Operations

MNFCs depend upon and exploit the advantages of

space-based capabilities. Available space

capabilities are normally limited to already

deployed assets and established priorities for space

system resources. Space systems offer global

coverage and the potential for real time and near real

time support to military operations. US Strategic

Command, through the joint force component

commander, enables commands to access various

space capabilities and systems.

Information

All military activities produce information.

Informational aspects are the features and details of

military activities observers interpret and use to

assign meaning and gain understanding. Those

aspects affect the perceptions and attitudes that

drive behavior and decision making. The joint force

commander/MNFC leverages informational aspects

of military activities to gain an advantage; failing to

leverage those aspects may cede this advantage to

others. Leveraging the informational aspects of

Executive Summary

xvi JP 3-16

military activities ultimately affects strategic

objectives.

Cyberspace Operations

Cyberspace is a global domain within the

information environment consisting of the

interdependent network of information technology

infrastructures and resident data, including the

Internet, telecommunications networks, computer

systems, space-based resources, and embedded

processors and controllers. Cyberspace uses

electronics and the electromagnetic spectrum

(EMS) to create, store, modify, and exchange data

via networked systems. Cyberspace operations seek

to ensure freedom of action throughout the

operational environment for US forces and our

allies, while denying the same to our adversaries.

Cyberspace operations overcome the limitations of

distance, time, and physical barriers present in the

physical domains. Cyberspace links actions in the

physical domains, enabling mutually dependent

operations to achieve an operational advantage.

Other Multinational Operations

Stability Activities

Stabilization is the process by which military and

nonmilitary actors collectively apply various

instruments of national power to address drivers of

conflict, foster HN resiliencies, and create

conditions that enable sustainable peace and

security. Stability is needed when a state is under

stress and cannot cope. MNFs supporting

stabilization efforts should consider the use of

fundamentals of stabilization and the principles of

multinational operations to plan and execute

military activities to facilitate long-term stability.

The fundamentals are conflict transformation, HN

ownership, unity of effort, and building HN

capacity.

Special Operations

Special operations forces (SOF) can provide the

MNTF with a wide range of specialized military

capabilities and responses. SOF can provide

specific assistance in the areas of assessment,

liaison, and training of HN forces within the MNTF

operational area.

Executive Summary

xvii

Joint Electromagnetic Spectrum

Management Operations

To prevail in the next conflict, an MNF must win

the fight for EMS superiority. Devices whose

functions depend on the EMS are used by both

civilian and military organizations and individuals

for intelligence; communications; positioning,

navigation, and timing; sensing; command and

control; attack; ranging; and data transmission and

information storage and processing.

Noncombatant Evacuation

Operations

The President of the United States is the approval

authority for noncombatant evacuation operations

(NEOs), which will be conducted under the lead of

the chief of diplomatic mission, the President’s

personal representative to the HN. An NEO is

conducted to relocate designated noncombatants

threatened in a foreign country to a place of safety.

NEOs are principally conducted by US forces to

evacuate US citizens but may be expanded to

include citizens from the HN, as well as citizens

from other countries.

Foreign Humanitarian

Assistance Operations

FHA operations, particularly in developing

countries, often require the intervention and aid of

various agencies, including the military, from all

over the world, in a concerted and timely manner.

As a result, operations involve dynamic information

exchange, planning, and coordination.

Countering Weapons of Mass

Destruction

Countering weapons of mass destruction is a

continuous campaign that requires a coordinated

multinational and whole-of-government effort to

curtail the conceptualization, development,

possession, proliferation, use, and effects of

weapons of mass destruction related expertise,

materials, and technologies.

CONCLUSION

This joint publication provides doctrine for the

Armed Forces of the United States when they

operate as part of a multinational (coalition or allied)

force.

Executive Summary

xviii JP 3-16

Intentionally Blank

I-1

CHAPTER I

FUNDAMENTALS OF MULTINATIONAL OPERATIONS

1. Multinational Operations Overview

Multinational operations are conducted by forces of two or more nations, usually

undertaken within the structure of a coalition or alliance. Other possible arrangements

include supervision by an international organization such as the United Nations (UN),

North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), or Organization for Security and Cooperation

in Europe. Commonly used terms under the multinational rubric include allied, bilateral,

coalition, combined, or multilateral. However, within this publication, the term

multinational will be used to describe these actions. There are two primary forms of

multinational partnership the joint force commander (JFC) will encounter:

a. An alliance is the relationship that results from a formal agreement between two or

more nations for broad, long-term objectives that further the common interests of the

members.

b. A coalition is an arrangement between two or more nations for common action.

Coalitions are typically ad hoc; formed by different nations, often with different objectives;

usually for a single problem or issue, while addressing a narrow sector of common interest.

Operations conducted with units from two or more coalition members are referred to as

coalition operations.

2. Strategic Context

a. Nations form regional and global geopolitical and economic relationships to

promote their mutual national interests, ensure mutual security against real and perceived

threats, conduct foreign humanitarian assistance (FHA), conduct peace operations (PO),

and promote their ideals. Cultural, diplomatic, psychological, economic, technological,

and informational factors all influence multinational operations and participation.

However, a nation’s decision to employ military capabilities is always a political

decision.

b. Since Operation DESERT STORM in 1991, the trend has been to conduct US

military operations as part of a multinational force (MNF). This could be under the

auspices of a NATO operation, which may also include non-NATO nations (e.g., Operation

UNIFIED PROTECTOR in 2011) or an MNF consisting of a coalition of nations that is

formed without NATO (e.g., Operation INHERENT RESOLVE, 2014-present).

“In the decades after fascism’s defeat in World War II, the United States and its

allies and partners constructed a free and open international order to better

safeguard their liberty and people from aggression and coercion. Although this

system has evolved since the end of the Cold War, our network of alliances and

partnerships remain the backbone of global security.”

Summary of the 2018 National Defense Strategy of the United States of America

Chapter I

I-2 JP 3-16

Therefore, US commanders should be prepared to perform either supported or supporting

roles in military operations as part of an MNF. These operations could span the range of

military operations and require coordination with a variety of United States Government

(USG) departments and agencies, foreign military forces, local authorities, international

organizations, and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). The move to a more

comprehensive approach toward problem solving, particularly in regard to

counterinsurgency operations, other counter threat network activities, or stability activities,

increases the need for coordination and synchronization among military and nonmilitary

entities.

For more information on counterinsurgency operations and stability activities, see Joint

Publication (JP) 3-24, Counterinsurgency; JP 3-25, Countering Threat Networks; and JP

3-07, Stability.

c. Much of the information and guidance provided for unified action and joint

operations remains applicable to multinational operations. However, commanders and

staffs should account for differences in partners’ laws, doctrine, organization, weapons,

equipment, capacities, terminology, culture, politics, religion, language, and objectives.

There is no “standard template,” and each alliance or coalition normally develops its own

protocols and operation plans (OPLANs) to guide multinational action. While NATO

Allied doctrine provides guidance and authorities for US forces when operating as part of

a larger authorized NATO force, US forces should comply with US joint doctrine if NATO

doctrine is in conflict.

d. While most partner nations (PNs) recognize the range of military operations

terminology, authorities, commitments, and imposed constraints and restraints may not

mirror those of US forces who are now utilizing a ‘competition continuum’ (Figure I-1).

Allied Joint Publication (AJP)-3, Allied Joint Doctrine for the Conduct of Operations,

provides the NATO discussion comparable to JP 3-0, Joint Operations. For instance, some

frequent partners do not plan, execute, and assess their Services’ operations from a joint

perspective. Therefore, JFCs should establish early and continuous liaison that enhances

mutual understanding of each MNFs’ member’s commitment. This enhanced

understanding allows the JFC to consider the member’s operational, legal, and logistical

constraints and restraints (as prescribed by each partner’s national law and policy) and

facilitates operational planning that optimizes each contributing nation’s military

capabilities.

3. Nature of Multinational Operations

After World War II, General Dwight D. Eisenhower noted that “mutual confidence”

is the “one basic thing that will make allied commands work.” The tenets of multinational

operations are respect, rapport, knowledge of partners, patience, mission focus, team-

building, trust, and confidence. While these tenets cannot guarantee success, ignoring them

may lead to mission failure due to a lack of unity of effort. National and organizational

norms of culture, language, and communication affect MNF interoperability. Each partner

in unified action has a unique cultural identity. Military forces, civilian agencies, NGOs,

and international organizations approach military conflict from different perspectives.

Fundamentals of Multinational Operations

I-3

National and organizational values, societal and social norms, historic contexts, religious

beliefs, and organizational discipline all affect the perspectives of multinational partners.

Partners with similar cultures and a common language experience fewer obstacles to

interoperability. Even minor differences, such as dietary restrictions or officer-enlisted

relationships, may affect military operations significantly. Commanders may have to

accommodate cultural sensitivities and overcome diverse or conflicting religious, social,

societal, or traditional requirements, any of which can form bases for explicit or implicit

caveats on partners’ participation. In multinational operations, commanders rely upon the

tenets to build teamwork and trust in a joint or multinational force in multiple ways.

Commanders should establish relationships with their multinational counterparts based

upon mutual respect. Team building is essential to successful MNF interoperability. It can

be accomplished through training, exercises, and assigning missions that fit organizational

capabilities. Building teamwork and trust takes time and requires the patience of all

participants. The result is enhanced mutual confidence and unity of effort.

a. Respect. In assigning missions and tasks, the commander should consider that

national honor and prestige may be as important to a contributing nation as combat

capability. All partners must be included in the planning process, and their opinions must

be sought in mission assignment, organizational structure, and the operation assessment

process. Understanding, discussing, and considering partner ideas are essential to building

effective relationships, as are respect for each partner’s culture, customs, history, and

values. Junior officers or even senior enlisted personnel in command of small national

Figure I-1. Notional Competition Continuum

Security Cooperation

Operations in the Information Environment

Cyberspace Operations

Competition

Below Armed

Conflict

Armed

Conflict/War

Cooperation

Assure Deter Coerce Compel

Counter-Terrorism

Operations

Humanitarian

Assistance

Freedom of

Navigation

Forward Presence

Major Combat

Operations

Limited Contingency

Operations

Scale

Notional Competition Continuum

Competition

Continuum

Strategic

Use of Force

Campaign

Operations

Activities

Chapter I

I-4 JP 3-16

contingents may be the senior representatives of their government within the MNF and, as

such, should be treated with the courtesy and respect afforded the commanders of other

troop contributing nations. Without genuine respect of others, rapport and mutual

confidence cannot exist.

b. Rapport. US commanders and staffs should establish rapport with their

counterparts from PNs, as well as the multinational force commander (MNFC).

Establishing and maintaining rapport in a multinational environment through personal,

direct relationships is an effective means of ensuring successful unity of effort with or

among PNs. When interacting with non-English speakers, knowing at least a few phrases

and greetings will help establish a relationship. It is important to remember eye contact

and good listening skills are essential in building rapport. Therefore, when using an

interpreter, the focus should be on the person to whom the message is being conveyed.

Good rapport between leaders will improve teamwork among their staffs and subordinate

commanders and overall unity of effort. The use of liaisons can facilitate the development

of rapport by assisting in the staffing of issues to the correct group and in monitoring

responses, while taking care not to relegate operational decision making to those liaisons.

c. Knowledge of Partners. In addition to learning about the threat, deployed US

forces must demonstrate the capability to communicate and interact effectively with local

nationals, government officials, and other multinational partners. Developing and

demonstrating communication skills, regional knowledge, local customs, values, and

cultural awareness serves as a force multiplier that enables effective MNF operations.

d. Patience. Effective partnerships take time and attention to develop. Diligent

pursuit of a trusting, mutually beneficial relationship with multinational partners requires

untiring, evenhanded patience. This is more difficult to accomplish within coalitions than

within alliances; however, it is just as necessary. It is therefore imperative that US

commanders and their staffs apply appropriate resources, travel, staffing, and time not only

to maintain, but also to expand and cultivate multinational relationships. Without patience

and continued dialogue, established partnerships can rapidly degrade.

e. Mission Focus. When dealing with other nations, US forces should temper the

need for respect, rapport, knowledge, and patience with the requirement to ensure the

necessary tasks are accomplished by those with the capabilities, capacities, and authorities

to accomplish those tasks. This is especially critical with force protection (FP) where

failure could prove to have catastrophic results to personnel and mission. If operational

necessity requires tasks being assigned to personnel who are not proficient in

accomplishing those tasks, then the MNFC must recognize the risks and apply appropriate

mitigating measures (e.g., a higher alert level to potential threats). The JFC may need to

consider strategies to enable partners who may have capability shortfalls that would limit

their ability to accomplish tasks.

f. Trust and Confidence. Commanders should build personal relationships and

develop trust and confidence with other leaders of the MNF. Developing these

relationships is a conscious collaborative act rather than something that just happens.

Commanders build trust through words and actions. Trust and confidence are essential to

Fundamentals of Multinational Operations

I-5

synergy and harmony, both within the joint force and with our multinational partners.

Coordination and cooperation among organizations are based on trust. Trust is based on

personal integrity (sincerity, honesty, and candor). Trust is hard to establish and easy to

lose. There can be no unity of effort in the final analysis without mutual trust and

confidence. Accordingly, the ability to inspire trust and confidence across national lines

is a personal leadership quality to be cultivated. Saying what you mean and doing what

you say are fundamental to establishing trust and confidence in an MNF.

4. Security Cooperation

a. Security cooperation (SC) provides ways and means to help achieve national

security and foreign policy objectives. US national and Department of Defense (DOD)

strategic guidance emphasizes the importance of defense relationships with allies and

PNs to advance national security objectives, promote stability, prevent conflicts, and

reduce the risk of having to employ US military forces in a conflict. SC activities are

likely to be conducted in a combatant command’s (CCMD’s) daily operations. SC

advances progress toward cooperation within the competition continuum by

strengthening and expanding the existing network of US allies and partners, which

improves the overall warfighting effectiveness of the joint force and enables more

effective multinational operations. SC activities, many of which are shaping activities

within the geographic combatant commander (GCC) campaign plans—the centerpiece of

the planning construct from which OPLANs/concept plans (CONPLANs) are now

branches—are deemed essential to achieving national security and foreign policy

objectives. SC activities also build interoperability with NATO Allies and other partners

in peacetime, thereby speeding the establishment of effective coalitions—a key factor in

potential major combat operations with near-peer competitors.

b. The Guidance for Employment of the Force (GEF) provides the foundation for all

DOD interactions with foreign defense establishments and supports the President’s

National Security Strategy. With respect to SC, the GEF provides guidance on building

partner capacity and capability, relationships, and facilitating access (under the premise

that the primary entity of military engagement is the nation state and the means which

GCCs influence nation states is through their defense establishments). The GEF outlines

the following SC activities: defense contacts and familiarization, personnel exchange,

combined exercises and training, train and equip/provide defense articles, defense

institution building, operational support, education, and international armaments

cooperation.

c. GCC theater strategies, as reflected in their combatant command campaign plans

(CCPs), typically emphasize military engagement, SC, and deterrence activities as daily

operations. GCCs shape their areas of responsibility through SC activities by continually

employing military forces to complement and reinforce other instruments of national

power. The GCC’s CCP provides a framework within which CCMDs conduct

cooperative military activities and development. Ideally, SC activities lessen the causes

of a potential crisis before a situation deteriorates and requires substantial US military

intervention.

Chapter I

I-6 JP 3-16

d. The CCP is the primary document that focuses on each command’s activities

designed to attain theater strategic end states. The GEF and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs

of Staff Instruction (CJCSI) 3110.01, (U) Joint Strategic Campaign Plan (JSCP) (referred

to as the JSCP), provide regional focus and SC priorities.

e. DOD components may develop supporting plans that focus on activities conducted

to support the execution of the CCPs and on their own SC activities that directly contribute

to the campaign end states and/or DOD component programs in support of broader Title

10, US Code, responsibilities. The Services conduct much of the detailed work to build

interoperability and capacity with NATO Allies and mission partners.

For additional information on SC, see JP 3-20, Security Cooperation; Department of

Defense Directive (DODD) 5132.03, Department of Defense Policy and Responsibilities

Relating to Security Cooperation; the GEF; and the JSCP.

f. The DOD State Partnership Program establishes enduring relationships between

emerging PNs of strategic value and individual US states and territories. The DOD State

Partnership Program is an important contribution to the DOD SC programs conducted by

the GCCs in conjunction with the National Defense Strategy, National Security Strategy,

National Military Strategy, Department of State (DOS), campaign plans, and theater SC

guidance to promote national and combatant commander (CCDR) objectives, stability, and

partner capacity.

For more detailed discussion on the DOD State Partnership Program, see Department of

Defense Instruction (DODI) 5111.20, State Partnership Program (SPP), and JP 3-29,

Foreign Humanitarian Assistance.

5. Security Cooperation Considerations

a. Foreign internal defense (FID) is the participation by civilian and military agencies

of a government in any of the action programs taken by another government or other

designated organization to free and protect its society from subversion, lawlessness,

insurgency, terrorism, and other threats to their security. The focus of US FID efforts is to

support the host nation’s (HN’s) internal defense and development, which can be described

as the full range of measures taken by a nation to promote its growth and protect itself from

security threats.

b. US military support to FID should focus on assisting an HN in anticipating,

precluding, and countering threats or potential threats and addressing the root causes of

instability. DOD employs a number of FID tools that interact with foreign defense

establishments to build defense relationships that promote specific US security interests,

support civil administration, provide SC, develop allied and friendly military capabilities

for self-defense and multinational operations, and provide US forces with peacetime and

contingency access to an HN. FID typically involves conventional and special operations

forces from multiple Services. Special operations forces (SOF), military information

support forces, and civil affairs (CA) units are particularly well suited to conduct or support

FID.

Fundamentals of Multinational Operations

I-7

c. Security force assistance (SFA) is DOD’s activities that support the development

of the capacity and capability of foreign security forces (FSF) and their supporting

institutions. The US military conducts activities to improve the capabilities and capacities

of a PN’s (or regional security organization) executive, generating, and operating functions

through the execution of one or more SFA tasks, that include organizing, training,

equipping, rebuilding/building, or advising. While DOD primarily assists those FSF

organized under the national ministry of defense (or equivalent regional military or

paramilitary forces), the US military may support and coordinate with other USG

departments and agencies that are leading USG efforts to develop or improve forces

assigned to other ministries (or their equivalents) such as interior, justice, or intelligence

services.

d. Successful SFA operations require planning and execution consistent with the

following imperatives:

(1) Understand the Operational Environment (OE). This includes an

awareness of the relationships between the stakeholders within the unified action

framework, the HN population, business environment information, and threats. Key to

SFA success is an in-depth understanding of the size, organization, capabilities,

disposition, roles, functions, and mission focus of the PN’s security force.

(2) Ensure Unity of Effort. Unity of command is preferred but often

impractical. Command relationships can range from the simple to complex and must be

clearly delineated and understood. Within a multinational context, establishing

coordinating boards or centers assists unity of effort among the stakeholders.

(3) Provide Effective Leadership. SFA seeks to provide and instill leadership

at all appropriate levels of the FSF. Both MNF and HN leadership must fully comprehend

the OE and be prepared and supportive for the SFA effort to succeed.

(4) Build Legitimacy. The ultimate objective of SFA is to develop security

forces that are competent, capable, committed, and confident to contribute to the legitimate

governance of the HN population.

(5) Manage Information. This encompasses the collection, preparation,

analysis, management, application, and dissemination of information.

(6) Sustainability. This includes two major efforts: the ability of the US/MNF

to sustain the SFA effort throughout the operation or campaign, and the ability of the PN

security forces to ultimately sustain their operations independently.

(7) Do No Harm. SFA is often undertaken in support of complex operations and

US/MNF actions can become part of the conflict dynamic that either increases or reduces

tensions. SFA planners and practitioners must be sensitive to and maintain awareness for

adverse impacts in the security sector and on the HN population.

For additional discussion of SFA, see JP 3-20, Security Cooperation.

Chapter I

I-8 JP 3-16

6. Rationalization, Standardization, and Interoperability

a. International rationalization, standardization, and interoperability (RSI) with PNs

is important for achieving practical cooperation; efficient use of research, development,

procurement, support, and production resources; and effective multinational capability

without sacrificing US capabilities.

b. RSI should be directed at providing capabilities for MNFs to:

(1) Conduct rapid pace operations effectively at by leveraging the capabilities of

the entire MNF.

(2) Efficiently integrate and synchronize operations using common or compatible

doctrine.

(3) Communicate and collaborate at anticipated levels of MNF operations,

particularly to prevent friendly fire and protect the exchange of data, information, and

intelligence via either printed or electronic media in accordance with (IAW) appropriate

security guidelines.

(4) Share consumables consistent with relevant agreements and applicable law.

(5) Care for casualties consistent with relevant agreements and applicable law.

(6) Enhance military effectiveness by harmonizing capabilities of military

equipment.

(7) Increase military efficiency through common or compatible Service support

and logistics.

(8) Establish overflight and access to foreign territory through streamlined

clearance procedures for diplomatic and nondiplomatic personnel.

(9) Assure technical compatibility by developing standards for equipment design,

employment, maintenance, and updating so those nations that are likely to participate are

prepared. Extra equipment may be necessary so non-equipped nations are not excluded.

Such compatibility should include secure and nonsecure communications equipment and

should address other equipment areas, to include (but not limited to): ammunition

specifications, truck components, supply parts, and data transmission streams.

Detailed guidance on RSI may be found in CJCSI 2700.01, Rationalization,

Standardization, and Interoperability (RSI) Activities.

c. Rationalization. In the RSI construct, rationalization refers to any action that

increases the effectiveness of MNFs through more efficient or effective use of defense

resources committed to the MNF. Rationalization includes consolidation, reassignment of

national priorities to higher multinational needs, standardization, specialization, mutual

support or improved interoperability, and greater cooperation. Rationalization applies to

Fundamentals of Multinational Operations

I-9

both weapons and materiel resources (the processes to loan and/or transfer equipment to

another nation participating in an MNF operation) and non-weapons military matters.

d. Standardization. Unity of effort is greatly enhanced through standardization. The

basic purpose of standardization programs is to achieve the closest practical cooperation

among multinational partners through the efficient use of resources and the reduction of

operational, logistic, communications, technical, and procedural obstacles in multinational

military operations.

(1) Standardization is a four-level process beginning with efforts for

compatibility, continuing with interoperability and interchangeability measures, and

culminating with commonality. DOD is actively involved in several multinational

standardization programs, including:

(a) NATO’s main standardization fora; the five-nation (United States,

Australia, Canada, United Kingdom, and New Zealand) Five Eyes Air Force

Interoperability Council (AFIC); the American, British, Canadian, Australian, and New

Zealand (ABCANZ) Armies’ Program; and the thirteen-nation (Australia, Belgium,

Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, New Zealand, Spain,

United Kingdom, and United States) Multinational Strategy and Operations Group

(MSOG).

(b) The US also participates in the five-nation (Australia, Canada, New

Zealand, United Kingdom, and United States) Combined Communications-Electronics

Board (CCEB) that enables strategic and deployed force headquarters (HQ) information

and data exchange and interoperability of communications-electronics systems above the

tactical level of command, as well as the Australia, Canada, New Zealand, United

Kingdom, United States (AUSCANNZUKUS) Naval command, control, communications,

and computers organization working to achieve standardization and interoperability in

communications systems.

(2) Alliances provide a forum to work toward standardization of national

equipment; doctrine; and tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTP). Standardization is not

an end in itself, but it does provide a useful framework for commanders and their staffs.

Coalitions, however, are, by definition, created for a single purpose and usually (but not

always) for a finite length of time and, as such, are ad hoc arrangements. They may not

provide commanders with the same commonality of aim or degree of organizational

maturity as alliances.

(3) Alliances usually have developed a degree of standardization with regard to

administrative, logistic, and operational procedures. The mechanisms for this

standardization are international standardization agreements (ISAs). ISAs can be materiel

or non-materiel in nature. Non-materiel-related ISAs should already be incorporated into

US joint and Service doctrine and TTP. The five-paragraph operation order is one common

example. Materiel ISAs are implemented into the equipment design, development, or

adaptation processes to facilitate standardization. In NATO, ISAs are known as

standardization agreements (STANAGs) and AJPs and are instruments that are used to

Chapter I

I-10 JP 3-16

establish commonality in procedures and equipment. The ABCANZ Standards are another

type of ISA. The existence of these ISAs does not mean they will be automatically used

during an alliance’s multinational operation. Their use should be clearly specified in the

OPLAN or operation order. In addition, these ISAs cannot be used as vehicles for

obligating financial resources or transferring resources.

(4) Multinational publications (MPs) are a series of unclassified ISAs specifically

developed by NATO. MPs provide signatory nations with common doctrine, TTP, and

information for planning and conducting operations. These publications are available to

all nations through a NATO sponsor.

(5) Standardization agreements like AJPs, MPs, STANAGs, and ABCANZ

standards provide a baseline for cooperation within a coalition. In many parts of the world,

these multilateral and other bilateral agreements for standardization between potential

coalition members may be in place prior to the formation of the coalition. However,

participants may not be immediately familiar with such agreements. The MNFC

disseminates ISAs among the MNF or relies on existing standard operating procedures

(SOPs) and clearly written, uncomplicated orders. MNFCs should identify where they can

best standardize the force and achieve interoperability within the force. This is more

difficult to accomplish in coalition operations since participants have not normally been

associated prior to the particular contingency. The same considerations apply when non-

alliance members participate in an alliance operation. However, ISAs should be used

where possible to standardize procedures and processes.

(6) MNF SOPs provide for standardization of processes and procedures for

multinational operations. For example, the Multinational Planning Augmentation Team

(MPAT) program developed an MNF SOP with the 31 MPAT nations, has used it within

real-world contingencies, and routinely uses it in exercises and training throughout the

Asia-Pacific region.

e. Interoperability. Interoperability greatly enhances multinational operations

through the ability to operate in the execution of assigned tasks. Nations whose forces are

interoperable across materiel and nonmateriel capabilities can operate together effectively

in numerous ways. For example, as part of developing PN security forces, the extent of

interoperability can be used to gauge the effectiveness of SC/SFA activities. Although

frequently identified with technology, important areas of interoperability may include

doctrine, procedures, communications, and training.

(1) Factors that enhance interoperability start with understanding the nature of

multinational operations as described in paragraph 3, “Nature of Multinational

Operations.” Additional factors include planning for interoperability and sharing

information, the personalities of the commander and staff, visits to assess multinational

capabilities, a command atmosphere permitting positive criticism and rewarding the

sharing of information, liaison teams, multinational training exercises, and a constant effort

to eliminate sources of confusion and misunderstanding. The establishment of standards

for assessing the logistic capability of expected participants in a multinational operation

should be the first step in achieving logistic interoperability among participants. Such

Fundamentals of Multinational Operations

I-11

standards should already be established for alliance members when the preponderance of

NATO nations are representative of a particular alliance.

(2) Factors that inhibit interoperability include restricted access to national

proprietary defense information; time available; any refusal to cooperate with partners;

differences in military organization, security, language, doctrine, and equipment; level of

experience; and conflicting personalities.

Chapter I

I-12 JP 3-16

Intentionally Blank

II-1

CHAPTER II

COMMAND AND COORDINATION RELATIONSHIPS

1. Command Authority

Although nations will often participate in multinational operations, they rarely, if ever,

relinquish national command of their forces. As such, forces participating in a

multinational operation will always have at least two distinct chains of command: a

national chain of command and a multinational chain of command (see Figure II-1).

a. National Command. As Commander in Chief, the President always retains, and

cannot relinquish, national command authority over US forces. National command

includes the authority and responsibility for organizing, directing, coordinating,

controlling, planning employment of, and protecting military forces. The President also

has the authority to terminate US participation in multinational operations at any time. All

nations participating in a multinational operation will have their own form of national

command. NATO and the European Union (EU) use the term “full command” to describe

national command by their member states.

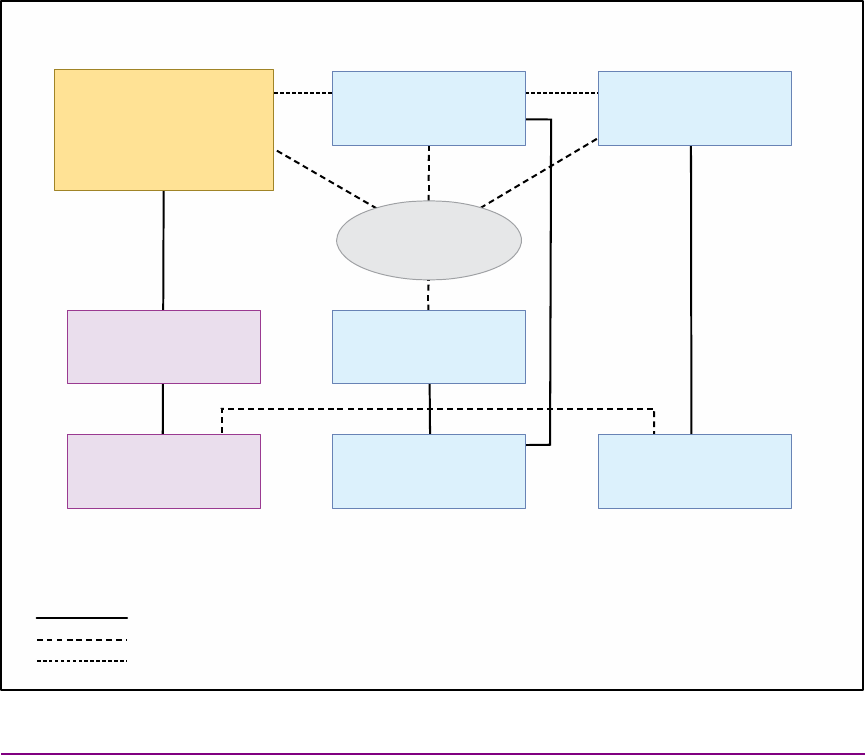

Figure II-1. Notional Multinational Command Structure

Notional Multinational Command Structure

*Examples include United Nations, alliances, treaties, or coalition agreements.

Legend

national command

command authority delegated to multinational force commander by participating nations

nation-to-nation communications

United States

President

and

Secretary of Defense

National

Government

Combatant

Commanders

Legitimizing

Authority

*

National

Government

Multinational Force

Commander

US National Force National ForceNational Force

Chapter II

II-2 JP 3-16

b. Multinational Command. Command authority for an MNFC is normally

negotiated between the participating nations and can vary from nation to nation. In making

a decision regarding an appropriate command relationship for a multinational military

operation, the President carefully considers such factors as mission, size of the proposed

US force, risks involved, anticipated duration, and rules of engagement (ROE). Command

authority will be specified in the implementing agreements that provide a clear and

common understanding of what authorities are specified over which forces.

For further details concerning command authorities, refer to JP 1, Doctrine for the

Armed Forces of the United States.

2. Unified Action

a. Unified action during multinational operations involves the synergistic

application of all instruments of national power as provided by each participating

nation; it includes the actions of nonmilitary organizations as well as military forces.

This construct is applicable at all levels of command. In a multinational environment,

unified action synchronizes, coordinates, and/or integrates multinational operations

with the operations of other HN and national government agencies, international

organizations (e.g., UN), NGOs, and the private sector to achieve unity of effort in the

operational area (OA). When working with NATO forces, it can also be referred to as

a comprehensive approach.

MULTINATIONAL OPERATIONS

In 2002, the Combined Maritime Forces was formed to counter piracy

and terrorism in the Persian Gulf, the Red Sea, and the Indian Ocean, a

three million square mile area. In 2005, Somalian pirates began raiding

ships in the Indian Ocean, especially in the Gulf of Aden. On the average,

each captured ship earned the pirates several million dollars and, in

2008, the pirates attacked 24 ships and seized 14 ships. In response to

the increased piracy, the United Nations Security Council passed four

resolutions condemning piracy and authorizing military forces to

conduct anti-piracy operations in over one million square miles of

territory. Under the Combined Maritime Forces, Combined Task Force

(CTF) 151, Counter-Piracy, was formed in January 2009 and is composed

of forces from several nations and two multinational commands. For

example, in 2010, CTF 151 was commanded by the following countries:

Singapore, Republic of Korea, Turkey, and finally by Pakistan. CTF 151

consisted of multinational forces, CTF 508, the NATO [North Atlantic

Treaty Organization] component commanded by a Portuguese, and then

by a Dutch commodore, and CTF 465, European Union Naval Forces,

was commanded by the Swedish, French, and finally by the Spanish.

Twenty-five different nations patrolled the Indian Ocean and defeated

the Somali pirates. CTF 151 also coordinated anti-piracy operations with

naval forces from China, Russia, and India.

Various Sources

Command and Coordination Relationships

II-3

b. Nations do not relinquish their national interests by participating in

multinational operations. This is one of the major characteristics of operating in the

multinational environment. Commanders should be prepared to address issues related to

legality, mission mandate, and prudence early in the planning process. In multinational

operations, consensus often stems from compromise.

Somalian Piracy Threat Map (2005-2010)

COMBINED TASK FORCE 151

Combined Task Force (CTF) 151, a multinational task force established

to conduct counter-piracy operations in the Gulf of Aden and Somali

Basin, operates under a mission-based United Nations Security Council

Resolution mandate throughout the Combined Maritime Forces area of

operations to actively deter, disrupt, and suppress piracy in order to

protect global maritime security and secure freedom of navigation for

the benefit of all nations. Contributing nations have included ships from

Australia, the Republic of Korea, Pakistan, Thailand, Turkey, and the US.

In conjunction with the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and European

Union Naval Force, ships from CTF 151 patrol in the Somali Basin and

the Internationally Recommended Transit Corridor in the Gulf of Aden.

CTF 151 also coordinates anti-piracy operations with naval forces from

China, Russia, and India.

Various Sources

Chapter II

II-4 JP 3-16

3. Multinational Force Commander

a. MNFC is a generic term applied to a commander who exercises command authority

over a military force composed of elements from two or more nations. The extent of the

MNFC’s command authority is determined by the participating nations or elements.

This authority can vary widely and may be limited by national caveats of those nations

participating in the operation. The MNFC’s primary duty is to unify the efforts of the

MNF toward common objectives. An operation could have numerous MNFCs.

(1) MNFCs at the strategic level are analogous to GCC level.

(2) MNFCs at the operational level may be referred to as subordinate MNFCs or

a multinational task force (MNTF). This level of command is roughly equivalent to the

US commander of a subordinate unified command or joint task force (JTF) and is the

operational-level portion of the respective MNF. Integrated MNTFs, such as the NATO-

led International Security Assistance Force (ISAF), will have embedded MNTF personnel

throughout the HQ. A lead nation (LN) MNTF HQ, like Multinational Force-Iraq, will be

staffed primarily by LN personnel and augmented by personnel from other MNTF

countries. Some integration in staff functions is possible, but the bulk of the work will be

handled within the LN structure. The LN provides the commander and the majority of

staff with the MNF HQ. Moreover, it is likely to dictate the language and command and

staff procedures utilized. Ultimately, the LN assumes responsibility for all aspects of

planning; execution; assessment; command, control, communications, and information

structure; doctrine; and logistic coordination that supports it. Other nations assign

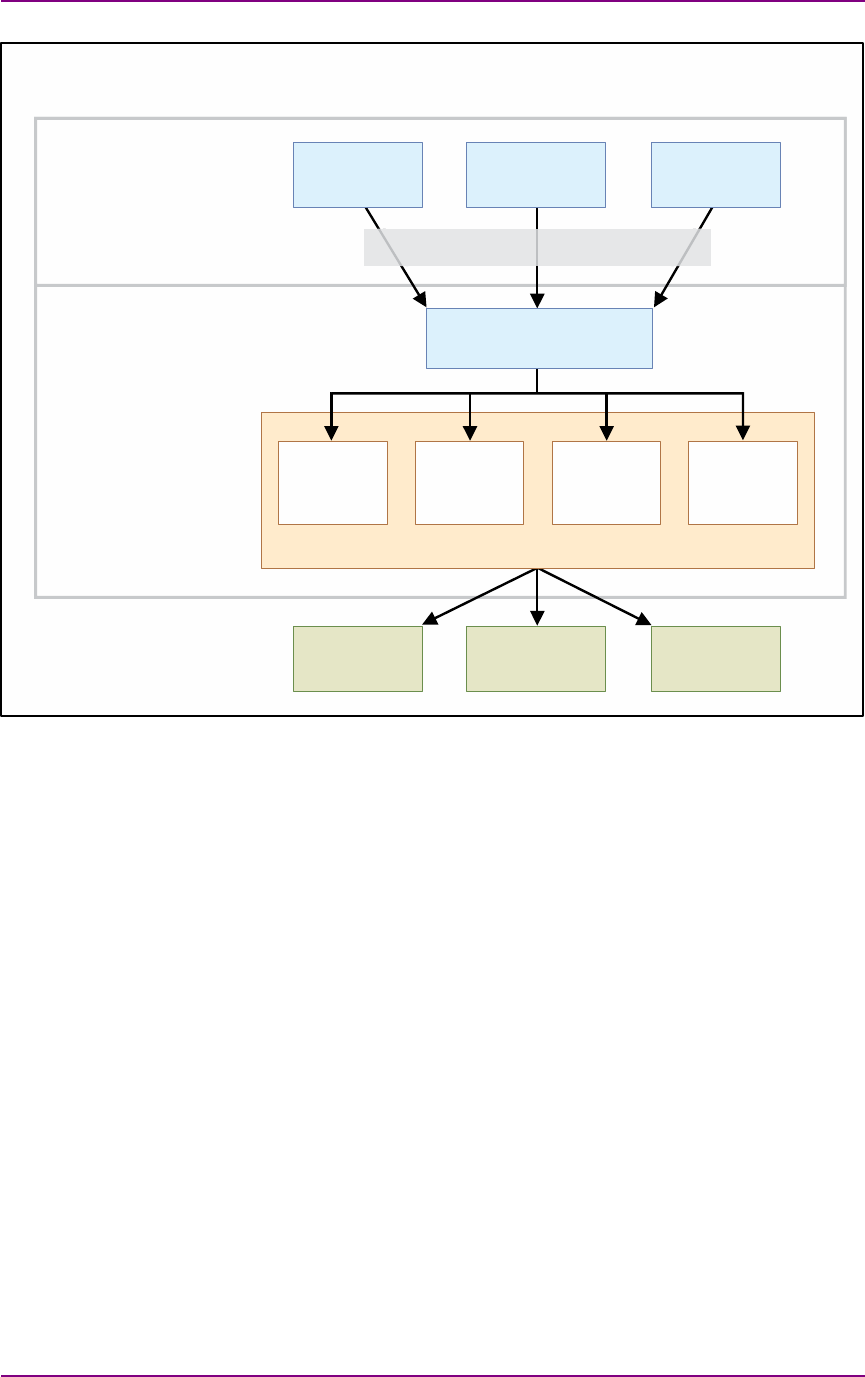

contributions to the force and fulfill some positions within the LN’s staff. Figure II-2

illustrates an example of the various command levels.

b. MNFCs should integrate and synchronize their operations directly with the

activities and operations of other military forces and nonmilitary organizations in the OA.

All MNTF commanders plan, conduct, and assess the effectiveness of unified action IAW

the guidance and direction received from the national commands, alliance or coalition

leadership, and superior commanders.

c. The MNF will attempt to align its operations, actions, and activities with NGOs

operating in a country or region. NGOs may be precluded from coordinating and

integrating their activities with those of an MNF to maintain their neutrality.

d. Training of forces within the MNTF command for specific mission standards

enhances unified action. The MNFC should establish common training modules or

certification training for assigned forces. Such training and certification of forces should

occur prior to entering the MNTF OA. Certification of forces should be accomplished by

a team composed of subject matter experts from all nations providing military forces to the

MNFC.

4. Overview of Multinational Command Structures

No single command structure meets the needs of every multinational command, but