1

“A Matter Requiring the Utmost Discretion”

A REPORT FROM THE ADVISORY TASK FORCE ON THE HISTORY OF

JEWISH ADMISSIONS AND EXPERIENCE AT STANFORD UNIVERSITY

September, 2022

Task Force Members:

Professor Ari Y Kelman (faculty), Chair

Professor Anthony Antonio (faculty)

Erika Bullock (graduate research assistant)

Emily Greenwald (graduate student)

Rabbi Laurie Hahn Tapper (staff)

Jem Jebbia (graduate research assistant)

Professor Emily Levine (faculty)

Odelia Lorch (undergraduate student)

Professor Kathryn Gin Lum (faculty)

Professor Matthew Snipp (staff)

Isaac Stein (alumnus)

Professor Mitchell Stevens (faculty)

Jeffrey Stone (trustee)

2

3

Table of Contents

Charge from the President to the Advisory Task Force on the History of Jewish Admissions and

Experience at Stanford University .................................................................................................. 4

Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................... 5

Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 7

What We Can Learn from Admissions .............................................................................. 11

The Emergence of Selective Admissions at Stanford ....................................................... 13

Snyder’s Intention to Suppress the Number of Jewish Students at Stanford .................. 17

Targeting High Schools ...................................................................................................... 20

Who Else Knew About Snyder’s Intentions? ..................................................................... 25

Admissions in Policy and Practice ..................................................................................... 26

Denial in Practice .............................................................................................................. 31

Impressions of Quotas ...................................................................................................... 39

Stanford’s Jewish Population ............................................................................................ 45

Conclusion ......................................................................................................................... 49

Recommendations ............................................................................................................ 52

Appendix A: The Glover Memo .................................................................................................... 63

Appendix B: Methodology for Historical Research ...................................................................... 64

Appendix C: Methodology for Quantitative Analysis .................................................................. 65

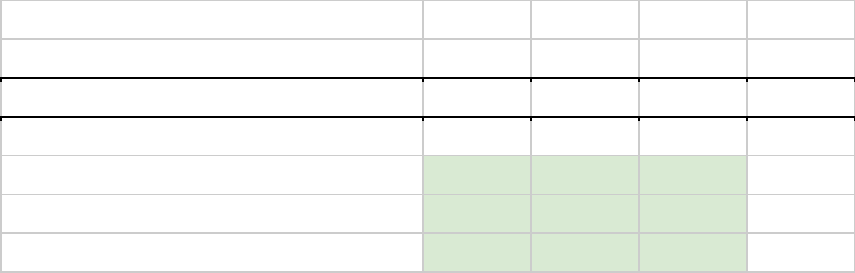

Appendix D: Enrollment Data from Selected Public High Schools as Presented in Registrar’s

Reports 1952-1960........................................................................................................................ 67

Appendix E: All Possible Combinations of Annual Enrollments at Stanford from Fairfax High

School, 1950-1958 ........................................................................................................................ 68

Appendix F: All Possible Combinations of Annual Enrollments at Stanford from Beverly Hills

High School, 1950-1958 ................................................................................................................ 69

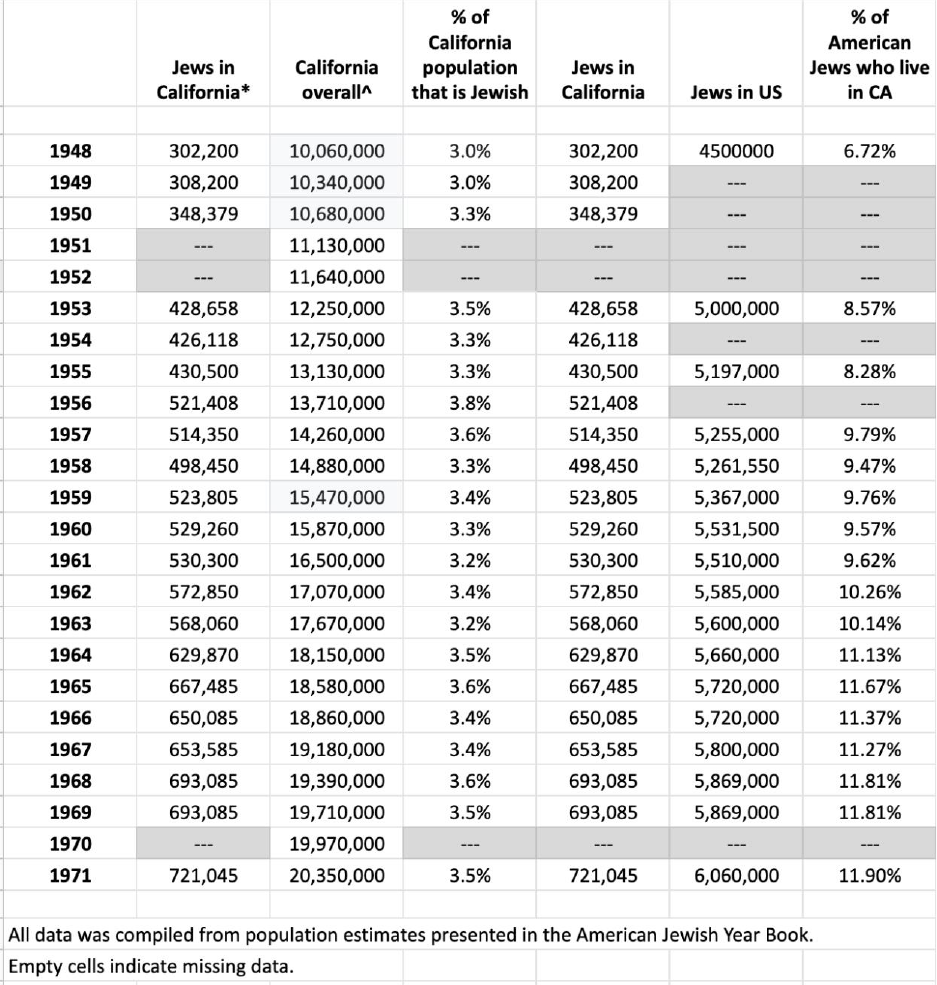

Appendix G: Jewish Population Data ........................................................................................... 74

Acknowledgements....................................................................................................................... 75

4

Charge from the President to the Advisory Task Force on the History of

Jewish Admissions and Experience at Stanford University

January, 2022

The Advisory Task Force on the History of Jewish Admissions and Experience at Stanford

University is charged with: (1) researching the history of admission policies and practices for

Jewish students at Stanford in the 1950s, including the allegations in a recent blog posting

“How I Discovered Stanford’s Jewish Quota” by Charles Petersen and (2) making

recommendations about how to enhance Jewish life on campus, including how best to address

any findings resulting from the research on admissions practices.

The task force will conduct this work under the sponsorship of the Office for Religious and

Spiritual Life and the Vice Provost for Institutional Equity, Access and Community. The findings

and recommendations of the task force will be presented to the President and Provost. The

President and Provost may ask for additional information or that the task force conduct such

other work as they deem appropriate.

All task force members will serve with an objective to represent the best interests of the entire

university and need to be open to multiple perspectives. Task force members are not intended

to represent any particular constituencies, but rather to consider issues impartially. It is

possible that committee members have heard, or even participated in, discussions on the issues

at hand. However, the role of the task force is to ascertain the relevant facts through the fact-

finding process and consider applicable principles with an open mind. Advocacy groups and

stakeholder perspectives may provide input on the issue through other methods, as

determined by the chair of the task force.

5

Executive Summary

In January 2022, an Advisory Task Force on the History of Jewish Admissions and Experience at

Stanford University was established to fulfill two interlocking charges. The first was to examine

Stanford’s admissions policies and practices during the middle of the 20th century to address

allegations about biases against Jewish students. The second was to make recommendations to

the university about “how to enhance Jewish life on campus, including how best to address any

findings resulting from the research on admissions practices.”

Charge #1

An extensive investigation uncovered two key findings. First, we discovered evidence of

actions taken to suppress the number of Jewish students admitted to Stanford during the early

1950s. Second, we found that members of the Stanford administration regularly misled parents

and friends of applicants, alumni, outside investigators, and trustees who raised concerns about

those actions throughout the 1950s and 1960s.

Early in 1953, Stanford’s Director of Admissions, Rixford Snyder, raised concerns about

the number of Jewish students at Stanford to Frederic Glover, the assistant to Stanford

President Wallace Sterling. Glover conveyed his account of the conversation and of Snyder’s

desire “to disregard our stated policy of paying no attention to the race or religion of

applicants” in a memo to Sterling. Glover supported Snyder’s intentions. In the memo, Glover

specified that Snyder was concerned about two Southern California high schools that he knew

to have significant numbers of Jewish students: Beverly Hills High School and Fairfax High

School.

We do not know whether Snyder also took action against any other schools or students

who identified themselves as Jewish on their applications, regardless of their high school. But

we found a sharp drop in enrollments from these two schools in the class that started Stanford

in the fall of 1953. No other schools experienced such a sharp reduction in students enrolling at

Stanford at that time.

Snyder did not act alone. Although we do not know whether Sterling read the memo

from Glover, at least three other people in the top levels of Stanford’s leadership read it,

including the Provost, Douglas Whitaker. If Sterling read the memo, which we cannot confirm,

then he, too, may be implicated in knowing about Snyder’s intentions and not acting to stop

them.

We do not know how long Snyder acted against these two schools or if he acted against

other schools or individual students. But the effect was felt particularly keenly among Jews in

Southern California among whom developed a widespread understanding that Stanford had a

“quota” on Jewish students. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, when alumni, the Anti-

Defamation League, and at least one trustee raised concerns to Glover, Sterling, or Snyder, they

were met with dismissals and denials. Glover’s and Snyder’s written responses took advantage

of the literal definition of “quota” and the discretion built into Stanford’s admissions policies to

misrepresent what they knew to be otherwise true: that they collaborated to suppress the

number of Jewish students enrolling at Stanford.

Although some of Stanford’s peer institutions employed anti-Jewish prejudices in their

approach to admissions, Stanford has always affirmatively prided itself on never having done

6

so. The historical research presented here calls that claim into question. While there may

never have been a formal quota (and Stanford used that technical defense often), we have

found clear evidence of anti-Jewish bias in admissions at the highest levels of the university in

the early 1950s.

Charge #2

The historical facts laid out in the fulfillment of the first charge to the task force serve as

the foundation to the recommendations about how to enhance Jewish life on campus in the

present and future. This task force evidences one example of how Stanford is beginning to face

its past and build toward a more equitable, inclusive, and just future.

The challenges that Jewish students face in a world shaped by rising antisemitism and

that they experience on campus rather than during the admissions process differ considerably

from many of those identified in response to the first charge. In order to better frame the

recommendations that follow, the task force organized two focus groups (one with

undergraduates and one with graduate students) and 10 semi-structured interviews as part of a

pilot project intended to better understand the experience of Jewish students at Stanford.

The insights shared by Jewish students generated two tiers of recommendations. The

first tier responds to the discoveries of the task force regarding Stanford’s history of efforts to

suppress the number of Jewish students at Stanford and its record of denying and dismissing

concerns about those efforts. The second tier draws on the pilot inquiry in order to direct

resources that might enhance the experiences of Jewish students at Stanford in the 21

st

century. We recommend that the university:

Acknowledge and Apologize

• Stanford publicly acknowledge its historical participation in admissions practices

designed to discriminate against Jewish students.

• Stanford publicly apologize for taking actions to suppress the number of Jewish students

and for misleading those who raised concerns about those issues.

Explore, Educate, and Enforce

• Undertake a comprehensive study of contemporary Jewish life at Stanford.

• Develop and include modules addressing Jews and Jewish identity in appropriate

educational trainings, seminars, and programs intended to make ours a more equitable,

inclusive, and just community.

• The ASSU should enforce the Undergraduate Senate’s “Resolution to Recognize Anti-

Semitism in Our Community” (UGS-W2019-23).

• Schedule the opening of the school year so that it does not coincide with the Jewish

High Holidays and specifically Yom Kippur and Rosh Hashana.

• Provide for student religious and cultural needs in housing and dining.

• Clarify the relationship between the university and Stanford Hillel.

7

Introduction

“Rix is concerned that more than one quarter of the applications from men are from Jewish

boys. Last year we had 150 Jewish applicants, of whom we accepted 50. This condition appears

to apply one [sic] to men; there does not seem to be any increase in applications from Jewish

girls. … Rix … says that the situation forces him to disregard our stated policy of paying no

attention to the race or religion of applicants. I told him that I thought his current policy made

sense, that it was a matter requiring the utmost discretion. …”

- Fred Glover, February 4, 1953

“[I]t is inevitable that candidates of all faiths will be turned down. We are never accused of

being anti-Catholic or anti-Methodist, but the charge does seem to arise sometimes, when a

Jewish candidate is involved, that the University is anti-Jewish.”

- Fred Glover, December 28, 1954

This inquiry into the history of Stanford’s admissions policies takes shape during an historical

moment in which institutions of all kinds are critically reexamining their own histories. A

growing awareness of the severity of historical and systematic injustices have toppled

monuments, reinvented museums, and led to movements to rename everything from public

schools to city streets. As institutions committed to free inquiry and rigorous, fact-based

investigation, universities bear a particularly heavy responsibility for leading the way in these

efforts. Committees and commissions at Harvard, Princeton, Yale, Georgetown, and Johns

Hopkins have advanced efforts to acknowledge the role these institutions and their leadership

have played in the advancement of slavery, racism, eugenics, and other forces that exacerbated

systematic inequalities between people.

1

Stanford has engaged in its own efforts of self-

1

Anderson, Greta. 2020. “Campuses Reckon With Racist Past.” Inside Higher Ed. July 6, 2020.

https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2020/07/06/campuses-remove-monuments-and-building-names-legacies-

8

reflection, as well, which have resulted in the removal or alteration of names attached to

campus features.

2

As part of this effort, Stanford has created new positions in the Provost’s

office “intended to lead equity and inclusion efforts at Stanford.” It has also dedicated

significant resources toward IDEAL, a multifaceted initiative to address questions of inequality

and diversity in every area of the campus.

3

These efforts, both historical and programmatic, are

among the many required to lay the groundwork for impactful and lasting change on our

campuses and in our communities.

The immediate impetus for this investigation was the publication of an online

newsletter by Dr. Charles Petersen entitled “How I Discovered Stanford’s Jewish Quota.”

4

The

newsletter highlighted a memo (hereafter known as the Glover Memo) that Dr. Petersen

discovered in the papers of Stanford President J. E. Wallace Sterling that shared concerns of the

then-Director of Admissions, Rixford K. Snyder, about the possibility of a “high percentage” of

racism; “Georgetown Reflects on Slavery, Memory, and Reconciliation.” n.d. Georgetown University. Accessed

April 7, 2022. https://www.georgetown.edu/slavery/; “Princeton Renames Wilson School and Residential College,

Citing Former President’s Racism.” 2020. Princeton Alumni Weekly. June 27, 2020.

https://paw.princeton.edu/article/princeton-renames-wilson-school-and-residential-college-citing-former-

presidents-racism; Viglione, Giuliana, and Nidhi Subbaraman. 2020. “Universities Scrub Names of Racist Leaders —

Students Say It’s a First Step.” Nature 584 (7821): 331–32. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-02393-3; “Yale and

Slavery Working Group.” 2020. Office of the President. November 16, 2020.

https://president.yale.edu/committees-programs/presidents-committees/yale-and-slavery-working-group;

“Harvard & the Legacy of Slavery.” n.d. Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University. Accessed May

3, 2022. https://legacyofslavery.harvard.edu/homepage.

2

“Campus Names.” n.d. Accessed April 7, 2022. https://campusnames.stanford.edu/; Stanford University. 2018.

“Stanford Will Seek to Rename Serra Mall in Honor of Jane Stanford.” Stanford News (blog). September 13, 2018.

https://news.stanford.edu/2018/09/13/naming-report/; Stanford University. 2020. “Stanford Will Rename Campus

Spaces Named for David Starr Jordan and Relocate Statue Depicting Louis Agassiz.” Stanford News (blog). October

7, 2020. https://news.stanford.edu/2020/10/07/jordan-agassiz/.

3

Beginning in 2018, IDEAL has introduced a dashboard for representing the composition of the Stanford

community, new provostial fellows, new faculty hires, and “learning journeys,” all of which are intended to support

and encourage the creation of a campus that is a “respectful, fair and safe environment in which all members can

thrive.” See: https://ideal.stanford.edu/

4

Petersen, Charles. 2021. “How I Discovered Stanford’s Jewish Quota.” Substack newsletter. Making History (blog).

August 8, 2021. https://charlespetersen.substack.com/p/stanfords-secret-jewish-quota. The task force would like

to thank Dr. Petersen for raising the issue that led to the work of the task force. We are also grateful for his

generosity in sharing resources.

9

Jewish students enrolling at Stanford.

5

The memo, written by Sterling’s assistant Fred Glover,

reported that Snyder intended to limit the number of Jewish students, an idea that Glover

believed “made sense.” We do not know whether or not Sterling read the memo (a full

transcription of the memo can be found in Appendix A).

The report that follows focuses on four concerns. First, it examines the memo within

the context of Stanford’s admissions policies and practices of the time and it identifies the

mechanisms used to try and limit the number of Jewish students at Stanford. The second

concern explores efforts that Snyder and Glover took to mislead independent investigators,

alumni, and at least one trustee about their efforts. Third, it highlights the impact of Snyder’s

actions beyond the campus. Finally, it offers recommendations about how to improve the

experience of Jewish students at Stanford.

This report, therefore, draws on the past to engage a present in which antisemitism is

an increasingly pressing concern. Antisemitic events in the United States including the 2017

“Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, the 2018 massacre of Jews at the Tree of Life

synagogue, and the taking of hostages at a synagogue in Colleyville, Texas, in 2021 have shown

this to be true. The Anti-Defamation League’s 2021 Audit found antisemitic incidents in the

United States to be at an all-time high.

6

While it is possible to disagree about what constitutes

an antisemitic act, it is clear that American antisemitism remains a persistent, pernicious, and

highly malleable feature of American politics and culture and that it has found expression

5

Memo from Fred Glover to Wallace Sterling February 4, 1953. J. E. Wallace Sterling, President of Stanford

University, Papers (SC0216, Box 7, Folder 14). Department of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford

University Libraries, Stanford, Calif.

6

https://www.adl.org/audit2021w

10

everywhere along the political spectrum from the far right to the far left.

7

Stanford is not

insulated from these broader currents and members of the campus community feel the

pressures and pains born of a context in which people feel increasingly emboldened to espouse

antisemitic views and to act on them.

8

In response to these conditions, an investigation into past practices seems both abstract

and urgent. As some alumni interviewed for this project have asked, “Why investigate the

distant past when the pressures of the present seem so urgent?” This is a fair question, and it is

one that members of the task force have asked of ourselves. But as other such efforts at

Stanford and elsewhere have taught, it is difficult to engage with the present until we reckon

with the past. Reevaluating the past to reckon with and acknowledge it is a crucial step in

making substantive, meaningful, and long-lasting change.

This notion is central to Judaism’s understanding of repentance or הבושת (teshuva). The

term’s linguistic root is the same as the word “to return” or “to go back.” Etymologically, it

implies a process of returning to the past in order to acknowledge it, apologize, and make

amends. The evidence for what medieval philosopher Moses Maimonides calls “complete

repentance” is that a person behaves differently in light of their acknowledgement of past

7

Baddiel, David. 2021. Jews Don’t Count. TLS Books; Lipstadt, Deborah E. 2019. Antisemitism: Here and Now. New

York: Schocken; Rosenberg, Yair. 2022. “Why So Many People Still Don’t Understand Anti-Semitism.” The Atlantic.

January 19, 2022. https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2022/01/texas-synagogue-anti-semitism-

conspiracy-theory/621286/; Ward, Eric. 2017. “Skin in the Game.” Political Research Associates. Accessed April 7,

2022. https://politicalresearch.org/2017/06/29/skin-in-the-game-how-antisemitism-animates-white-nationalism;

Weiss, Bari. 2019. How to Fight Anti-Semitism. New York: Crown.

8

Throughout this report, we will follow the convention of writing “antisemitism” rather than “anti-Semitism.” The

rationale behind this spelling is best explicated by Deborah Lipstadt who has written: “In my own English-language

usage I choose not to go with the hyphen because the word, both as its creator had intended and as it has been

generally used for the past one hundred and fifty years, means, quite simply, the hatred of Jews. It does not mean

hostility toward a nonexistent thing called ‘Semitism.’” Lipstadt, Deborah E. 2019. Antisemitism: Here and Now.

New York: Schocken. 14.

11

deeds. It is in the spirit of הבושת that we offer this report to the university community, in the

hope that this return to the past is the beginning of a turn toward a better, more respectful,

and more equitable future for all of its members.

What We Can Learn from Admissions

Admissions can be understood as a membrane between the university and the public.

Admissions policies and practices shape the character and culture of every university or college

by selecting some people to join the institution while refusing others; these policies and

practices construct a student body out of an assortment of applicants and build a university

class by class.

9

Consequently, admissions offer a unique window into the composition of the

campus community and the formation of its culture. The policies and practices that define

admissions have profound and consequential effects far beyond the evaluation of any single

student.

Admissions offices, however, do not operate alone and their decisions are not made in

isolation. As an internal Stanford report from 1966 observed, “[A]dmissions policies and

procedures do not stand in isolation from the rest of the University. Rather — for good and bad

— they both influence and are influenced by the various characteristics of the Stanford

9

Soares, Joseph A. 2007. The Power of Privilege: Yale and America’s Elite Colleges. Stanford: Stanford University

Press; Steinberg, Jacques. 2002. The Gatekeepers: Inside the Admissions Process of a Premier College. 6/29/02

edition. Penguin Books; Stevens, Mitchell L. 2009. Creating a Class: College Admissions and the Education of Elites.

Cambridge, Mass.; London: Harvard University Press.

12

curriculum, formal and informal.”

10

Archival documents indicate that during the middle

decades of the 20th century, Stanford’s admissions decisions were managed by a small group of

admissions officers in collaboration with others in the Offices of the President and Provost,

development, alumni relations, faculty and staff, alumni “ambassadors,” and counselors and

principals at hundreds of high schools across the United States.

This extended admissions apparatus illustrates the complexity of the process and the

variety of factors accounted for within it. Early in the 20

th

century, as qualified candidates

began to outnumber available spots in incoming classes, elite American colleges and

universities pivoted from “qualitative admissions,” which admitted all qualified applicants,

toward an approach known as “selective admissions,” which chose among all qualified

applicants.

11

This new approach birthed questions about how to justify the selection of one

applicant over another or how to develop a policy that systematized acceptance decisions. As

historians Jerome Karabel, Marsha Synnott, and Harold Wechsler have shown, selective

admissions emerged at a moment in the history of American higher education when elite

colleges and universities faced increased demand from qualified students who did not “fit”

their image of either their desired students or their institutions.

12

10

Letter. Rixford K. Snyder to Thomas C. Dyer. January 23, 1967. Stanford University, President’s Office. Sterling-

Pitzer Transition Papers (SC0217, Box 3, Folder 2). Department of Special Collections and University Archives,

Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, Calif.

11

In his oral history, Snyder recalled that he helped Stanford move from “qualitative admissions,” which admitted

all qualified students, to “selective admissions,” which selects “among all those who do meet the established

requirements. See Snyder, Rixford K. Oral History. Stanford Oral History Project Interviews (SC1017,

https://purl.stanford.edu/cf859pn5973), pages 36-37. Department of Special Collections and University Archives,

Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, Calif.

12

Karabel, Jerome. 2005. The Chosen: The Hidden History of Admission and Exclusion at Harvard, Yale, and

Princeton. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co; Synnott, Marcia Graham. 1979. The Half-Opened Door: Discrimination and

Admissions at Harvard, Yale and Princeton, 1900-1970. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press; Wechsler, Harold S.

1977. The Qualified Student: A History of Selective College Admission in America. New York: Wiley.

13

The innovation of selective admissions solved the problem of having too many qualified

applicants by creating new, elaborate systems and metrics for evaluating them. This solution,

however, introduced new challenges: How does a school create systems that can assess “well

roundedness”? How does an application process provide indications of who will succeed and

who will not? What other aspects of a campus culture does this particular school value and

wish to account for in admissions? How does an admissions officer decide between two

apparently equally qualified students? The result has been that college admissions processes,

no matter how well-defined or well-explained, include plenty of room for discretion and

judgment. Selective admissions, therefore, is highly dynamic and subject to erroneous

judgments on the part of both institutions and applicants. “The decisions that determine the

sorting among colleges are guided by a certain substratum of factual knowledge about higher

education, supplemented by a vast, amorphous, and confused body of beliefs, rumors, folklore,

and gossip. This situation is true both of students in choosing colleges and of colleges in

choosing students.”

13

The Emergence of Selective Admissions at Stanford

Stanford’s approach to admissions has always afforded a great deal of discretion to those

making admissions decisions. From the 1920s until 1947, admissions were handled by the

Office of the Registrar in consultation with a faculty Committee on Admissions and Advanced

13

Thresher, B. Alden. 1966. College Admissions and the Public Interest. New York: College Entrance Examination

Board. 68.

14

Standing.

14

Applications were brief – barely two pages long – and recommendations were

highly formalized.

15

Applications included typical questions about schooling and residence,

alongside ratings of the applicant’s general health, eyesight, hearing, and whether they had

“speech handicaps” or “physical handicaps.”

16

Applicants were asked to report their father’s

occupation and their mother’s maiden name. It also included two questions about religion.

1. Of what church or religious society are you a member?

2. If not a member, church preference?

Applicants frequently left one or both of these answers blank. Others answered “Protestant” or

“Latter-Day Saints” or the name of a specific parish or church. One applicant left the first

question blank but indicated in the second that she was a member of Temple Shearith Israel in

San Francisco. Another said simply “Judaism.” The religion questions remained on Stanford’s

applications until 1950.

17

14

Fetter, Jean H. 1997. Questions and Admissions: Reflections on 100,000 Admissions Decisions at Stanford.

Stanford University Press. 1-5. See also Mitchell, J. Pearce. 1958. Stanford University 1916-1941. Stanford, CA: The

Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University. 48-52.

15

Beginning in 1929, Stanford adopted a “personal rating blank” for recommenders to complete. This appears to

have remained in use until the late 1940s when it was phased out in favor of a different approach to

recommendations. For an example of the form, see Patterson, Ruth. 1931. “Evaluation of a Personal Rating Blank

as Used at Stanford for Graduate Students.” Thesis (M.A.), Stanford, CA: Stanford University, School of Education,

page 5.

16

Stanford has retained files on every student who enrolled in the university. These files include grades,

correspondence about financial aid and academic standing, and applications. All of the information about

Stanford’s application forms during the period in question has been drawn from these microfilmed files. Stanford

University Registrar’s Office, Records (SC1288, Series 9, Boxes 4-12).

17

It is unclear what prompted the removal of the questions in 1950, but it was part of an overall revision of the

application, likely initiated by Al Grommon, director of admissions 1948–1950. A brief story appeared in 1947

announcing that “Stanford University does not consider race or religion in determining a candidate’s eligibility for

admission.” The article also noted that the religion questions would be deleted from new application forms. The

Stanford Daily. July 28, 1947, 1. Around this same time, the ADL launched an effort to remove religion questions

from college applications. It is unclear whether or not the ADL’s efforts influenced Stanford’s decision to change

its applications. For a note about the University of Alabama changing its application questions, see The ADL

Bulletin. 1952. “Bulletin Briefs,” January 1952. See also a note that Crack the Quota resulted in more than “700

colleges in 21 states” that had “had eliminated from their admission blanks those questions asking race, religion,

mother’s birthplace, etc., which have no legitimate bearing on an applicant’s qualifications for getting into college,

but are potentially harmful in the hands of a biased, or quota-minded, admissions officer.” The ADL Bulletin. 1956.

“Bulletin Briefs,” January 1956.

15

Stanford Registrar J. Pearce Mitchell (who served 1925-1945) explained that once an

application had been received, “The members of the Committee on Admissions and Advanced

Standing then reviewed all the data and based their decisions on the total desirability of the

applicant rather than on any one factor.”

18

The need to assess “total desirability” led to the

codification of a ten-point scale that awarded “three [points] for the school record on a strictly

mathematical scale; three [points] for the score on the aptitude test … and four points for the

Committee’s judgment regarding the student’s personal qualities, general promise, and so on.

Two members of the Committee read and scored all the applications, and averaged the

results.”

19

Although the process by which they decided to admit a given student or how they

applied the ten-point scale is unknown, Mitchell believed that “the results were reasonably

satisfactory.”

20

The years immediately after World War II required a change in approach. Students

returning from military service and others supported by the GI Bill resulted in an

“unprecedented number of qualified applicants for admission [that] was too impressive to be

ignored.”

21

Competition for spots had been “so keen” that the university was forced to “deny

admission to hundreds of students with fine records who, in normal times, would have been

accepted.”

22

In response, Stanford appointed Al Grommon, a professor of English, as its first

18

Mitchell, J. Pearce. 1958. Stanford University 1916-1941. Stanford, CA: The Board of Trustees of the Leland

Stanford Junior University. 52. Also quoted in Fetter, 4-5.

19

Mitchell, J. Pearce. 1958. Stanford University 1916-1941. Stanford, CA: The Board of Trustees of the Leland

Stanford Junior University. 52.

20

Mitchell, J. Pearce. 1958. Stanford University 1916-1941. Stanford, CA: The Board of Trustees of the Leland

Stanford Junior University. 52

21

President Donald Tresidder. Annual report of the president of Stanford University for the academic year ending

1946. 4. Stable url: purl.stanford.edu/dz233yh9603

22

Annual report of the president of Stanford University for the academic year ending 1946. 5. Stable url:

purl.stanford.edu/dz233yh9603

16

Director of Admissions in 1947. Grommon accomplished a great deal during his two years,

despite working without his own budget or staff.

23

In 1950, President J. E. Wallace Sterling replaced Grommon with a young professor of

history and Stanford graduate, Rixford Snyder.

24

Snyder got the nod after serving on the

Committee on Admissions and Advanced Standing, where he was the only member who

regularly read application files.

25

As the Director of Admissions, Snyder understood that his role

was to advance the mission of the university through the admissions process. He recalled that

Sterling

gave me two guidelines for my work in admission — build up a student body that would be

brighter than the then current faculty so he could attract outstanding professors from the East,

and to remember that the students I admitted in the fifties would be supporting the university

thirty years later — in short to consider both their qualifications and their potential loyalty to

the university.

26

Snyder understood that his job was to recruit students who would help ensure the future of the

university, and he took the responsibility seriously. He did not offer a discrete vision for who

these students ought to be, though he had a sense that they should not merely be “minds” or

23

Letter and Report. August 7, 1950. Al Grommon to Dr. J. E. Wallace Sterling. Office of Undergraduate

Admissions, Records (SC0407, Accession 1750, Box 1, Folder 7). Department of Special Collections and University

Archives, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, Calif.

24

Stanford Daily. April 14, 1950. Snyder joined the faculty after serving in the Navy during World War II. Before

his service in the Navy during World War II, Snyder taught in Stanford’s History Department as part of a team that

taught the Western Civilization course, a three-course sequence required of all undergraduates. In that role,

Snyder worked with Henry Madden, a lecturer who it has recently been discovered used his Stanford position and

budget to espouse views that were sympathetic to Nazism. See “Preliminary Report of the Task Force to Review

the Naming of the University Library.” April 18, 2022. Fresno, California: Fresno State University.

https://president.fresnostate.edu/taskforce-library/documents/HMMLibraryPreliminaryReport.pdf

25

Snyder, Rixford K. Oral History. Stanford Oral History Project Interviews (SC1017,

https://purl.stanford.edu/cf859pn5973), 28. Department of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford

University Libraries, Stanford, Calif.

26

Snyder, Rixford K. “Memories of a Santa Clara valley boy who never left, 1908-1991” typescript, 1991.

(SCM0237, Box 1), 86. Department of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford University Libraries,

Stanford, Calif.

17

“grinds.”

27

Instead, he emphasized the significance of “motivation, attitudes, character, and

future potential as citizens” in the creation of “strong alumni for the future.” Elsewhere,

Snyder explained, “Because Stanford is a residence university, and because it is important that

students fit into our community environment, the Committee bases as much as one-third of its

estimate of a candidate on this factor.”

28

Snyder served as the university’s Director of Admissions for 20 years that coincided with

critical decades in Stanford’s growth and emergence as an elite institution.

29

The story of

Stanford admissions during the 1950s and 1960s is one of creating a student body to match the

university’s growing reputation and rising stature. Snyder was central to this effort.

Snyder’s Intention to Suppress the Number of Jewish Students at

Stanford

Snyder also played a central role in efforts to limit the number of Jewish students at

Stanford. A 1953 memo written to President Sterling from his assistant, Fred Glover, explained

that Snyder has expressed concerns over the number of Jewish applicants (see Appendix A for a

27

Memo Rixford K. Snyder to Wallace Sterling. February 10, 1958. J. E. Wallace Sterling, President of Stanford

University, Papers (SC0216, Box A1, Folder 14). Department of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford

University Libraries, Stanford, Calif. See also Press Release. October 10, 1963. Stanford University, News Service,

Records circa 1891-2013 (SC 0122, Series 1, Box 186, Folder “Admissions: News releases 1960-1969”). The Press

Release quotes Snyder saying, “They have an all-round scholastic quality which marks them as ‘bright without

being grinds.’”

28

Snyder, Rixford K. “Admissions Standards: Tough but Flexible.” Stanford Review (January 1958), 13-15. Stanford

University News Service (SC0122, Box 3, Folder 1). Department of Special Collections and University Archives,

Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, Calif.

29

Rebecca Lowen’s history of Stanford during this period focuses almost exclusively on the efforts of the

administration and faculty. Lowen, Rebecca S. 1997. Creating the Cold War University: The Transformation of

Stanford. Berkeley: University of California Press. See also Gillmor, C. Stewart. 2004. Fred Terman at Stanford:

Building a Discipline, a University, and Silicon Valley. Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press.

18

full transcription of the memo).

30

Calling the number of Jewish students a “problem,” Glover

wrote: “Rix has been following a policy of picking the outstanding Jewish boys while

endeavoring to keep a normal balance of Jewish men and women in the class.” He continued,

“Rix feels that this problem is loaded with dynamite, and he wanted you [Sterling] to know

about it, as he says that the situation forces him to disregard our stated policy of paying no

attention to the race or religion of applicants.” Glover wrote that he approved of Snyder’s

decision. “I told him that I thought his current policy made sense” and said that he promised to

check with Sterling and let Snyder know if Sterling “had different views.”

Glover wrote the memo at precisely the moment when Snyder was starting to organize

and systematize the admissions process. In the oral history he conducted with the Stanford

Historical Society, Snyder recalled that “it wasn’t until really 1953 our admissions changed” to

become more selective, and that 1952 was the first year when he had to “turn down qualified

male applicants.” Calling the rise in applications a “problem” and a “major revolution in the

Stanford application picture,” Snyder noted that between 1951 and 1958, applications from

male candidates rose 151 percent and applications from female applications rose 101

percent.

31

Among other concerns, Snyder was trying to manage an admissions process that

was changing rapidly in three ways. First, competition between male students had grown

30

Memo from Fred Glover to Wallace Sterling February 4, 1953. J. E. Wallace Sterling, President of Stanford

University, Papers (SC0216, Box 7, Folder 14). Department of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford

University Libraries, Stanford, Calif.

31

Snyder, Rixford K. “Admissions Standards: Tough but Flexible.” Stanford Review (January 1958), 13-15. Stanford

University News Service (SC0122, Box 3, Folder 1). Department of Special Collections and University Archives,

Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, Calif. See also Report. Rixford K. Snyder “SUMMARY OF REPORT ON

ADMISSIONS MADE ON JUNE 19, 1957 TO THE COMMITTEE ON ACADEMIC AFFAIRS OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES

BY RIXFORD K. SNYDER DIRECTOR OF ADMISSIONS.” J. E. Wallace Sterling, President of Stanford University, Papers

(SC0216, Box B1, Folder 1). Department of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford University

Libraries, Stanford, Calif.

19

increasingly competitive and Snyder needed to develop a rationale for determining which

students to admit and which to reject.

32

Second, he and his two assistants were reading more

and more applications each year and they were looking for a way to manage the process.

In the Glover Memo, Glover relayed that Snyder had identified “a number of high

schools in Los Angeles — Beverly Hills and Fairfax are examples — whose studentbody [sic] runs

from 95 to 98% Jewish. If we accept a few Jewish applicants from these schools, the following

year we get a flood of Jewish applications.” Contemporary reports from the Registrar support

Snyder’s hunch: Between 1949 and 1952, Fairfax sent 20 male students and Beverly Hills High

School sent 67 – the fourth largest number among public high schools in California and the

largest outside of the Bay Area.

33

During these years, however, Stanford rejected very few

male applicants, so these numbers reflect a largely non-selective admissions process.

Nevertheless, he expressed concern over the number of applicants from these two schools

because of the “flood” created “if we accept a few Jewish applicants.”

Fairfax High School and Beverly Hills High School, while not the only schools to serve

substantially Jewish neighborhoods, were exceptional in this regard, situated in two of the most

densely Jewish neighborhoods in the Los Angeles area.

34

As one demographic study of Los

Angeles Jews concluded, “We find that the densest areas of Jewish population are on the

32

Owing to Jane Stanford’s quota on female students, competition among female applicants was much tougher

than it was among male applicants. Even after the Trustees voted to lift the quota in 1933 to allow more female

students and, in the process, to fend off economic pressures, a de facto quota remained in place as the university

required female students to live on campus but did not expand housing for them. The quota on female students

was only formally lifted in 1973.

33

Registrar’s Report for 1952 (SC1760 box 3).

34

Massarik, Fred. 1953. “A Report on the Jewish Population of Los Angeles.” Los Angeles, CA: Los Angeles Jewish

Community Council; Massarik, Fred. 1959. “A Report on the Jewish Population of Los Angeles.” Los Angeles, CA:

Jewish Federation Council of Greater Los Angeles.

20

Westside, with the Wilshire-Fairfax and the Beverly Fairfax area being more than 60 percent

Jewish. … A surprisingly high proportion of Jewish population is found in the Beverly Hills

area.”

35

These neighborhoods were so densely Jewish that it raised concerns for leaders in the

Los Angeles Jewish community who noted that non-Jewish students were requesting transfers

out of Fairfax High School, where they were uncomfortable in their minority status.

36

Snyder

appears to have used the demographics of these two schools as a proxy for Jewish students.

Targeting High Schools

Snyder needed a proxy because Stanford’s application forms did not ask about religion

or ethnicity, although it retained questions about father’s occupation and mother’s maiden

name, along with a requirement that applicants supply a photograph of themselves. On their

own, however, these pieces of information would not have allowed Snyder and his office to

identify Jewish applicants with certainty. This was even the case at Harvard, earlier in the

century. When Harvard set about trying to limit the number of Jewish students in 1922, it

convened a committee to develop a system for detecting Jewish applicants. An applicant

labelled “J1” meant that “the evidence pointed conclusively to the fact that the student was

35

Massarik, Fred. 1953. “A Report on the Jewish Population of Los Angeles.” Los Angeles, CA: Los Angeles Jewish

Community Council. 13. For a note about Fairfax, see Moore, Deborah Dash. 1994. To the Golden Cities: Pursuing

the American Jewish Dream in Miami and L.A. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. 86. See also Morris,

Bonnie J. 1997. The High School Scene in the Fifties: Voices from West L.A. Westport, Conn: Bergin & Garvey;

Vorspan, Max, and Lloyd P. Gartner. 1970. History of the Jews of Los Angeles. Regional History Series of the

American Jewish History Center of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America. San Marino, Calif: Huntington

Library.

36

“West Side Tensions,” n.d. (1955-1956). Jewish Federation Council of Greater Los Angeles, Community Relations

Committee Collection IV, Box 9, Folder “CRC-1956, “Westside Tensions Committee.” Urban Archives Center, Oviatt

Library, California State University, Northridge. See also Baumgarten, Max David. 2017. “Searching for a Stake: The

Scope of Jewish Politics in Los Angeles from Watts to Rodney King, 1965-1992.” Ph.D., Los Angeles, CA: UCLA.

https://escholarship.org/content/qt8gk6m3ks/qt8gk6m3ks.pdf. 45. With gratitude to Max D. Baumgarten for

providing these valuable documents.

21

Jewish,” whereas one identified as “J3” “suggested the possibility that the student was

Jewish.”

37

Snyder did not have the resources for such an elaborate undertaking.

Instead, Snyder followed a simpler and more discreet path laid out by his colleagues at

Yale. Although Glover noted that “Harvard and Yale stick strictly to a quota system,” it was also

not entirely accurate.

38

Before adding a question about religion to its applications in 1934, Yale

reduced but did not eliminate Jewish enrollments from neighboring areas known to have

sizeable Jewish populations: New Haven, Hartford, and Bridgeport, as well as public school

students from New York, Chicago, and Philadelphia, the three cities with the largest American

Jewish populations.

39

Of course, some non-Jewish students would have been caught up in this

effort, but Yale’s admissions team chalked it up to the cost of a more discreet effort intended to

“protect our Nordic stock,” according to Yale President James Rowland Angell.

40

Yale’s strategy

worked to suppress the number of Jewish students on campus and to effectively hide its efforts

from scrutiny.

Snyder appears to have followed this approach and its effect coincided with the

expression of his intention. First, Snyder stopped including these two schools in his recruitment

efforts.

41

Prior to 1953, itineraries of recruitment trips of Stanford’s admissions officers

37

“Statistical Report of the Statisticians” quoted in Karabel. The Chosen. 96. See also Synnott. The Half-Opened

Door, 94-95.

38

The nature of Harvard’s and Yale’s efforts to suppress the number of Jewish students was also not common

knowledge in 1953. Though Harvard’s activities in the 1920s were a matter of public record, Harvard seems to

have evaded the suspicions of the Anti-Defamation League in the early 1950s. “Great institutions–Harvard, New

York University, the University of Chicago, the University of Pennsylvania, to name a few–place no racial or

religious barriers upon admission.” Forster, Arnold. 1950. A Measure of Freedom. New York, NY: Doubleday and

Company. 116.

39

Oren. Joining the Club. 53-55. See also Karabel. The Chosen, 117-119; Synnott. The Half-Opened Door, 152.

40

Angell quoted in Karabel, 119.

41

Itinerary. “Southern California Trip.” January 8-12, 1951. Cuthbertson (Kenneth M.) Papers 1941-1994 (SC0582,

Box 98, file 9) Department of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford,

Calif. This document mentions visits to both Beverly Hills High School and Fairfax High School. A collection of

22

included trips to Fairfax High School and Beverly Hills High School. After the Glover Memo, they

disappear, though other Los Angeles high schools that catered to neighborhoods with large

Jewish populations, like Hamilton High School, Hollywood and North Hollywood High Schools,

continued to appear on recruitment schedules. Despite reporting that “the three Admissions

Officers concentrated their efforts on the problems of recruitment of the Freshman Class,”

Snyder omitted recruiting directly from two schools that previously had regularly sent

significant numbers of students to Stanford.

42

Their records would easily have qualified them

as “feeder schools,” in the parlance of the Admissions Office.

Second, Snyder appears to have taken other steps that had more direct and measurable

effects, visible only in a close analysis of the annual reports of the Registrar’s Office. As

mentioned earlier, between 1949 and 1952 Stanford enrolled 67 students from Beverly Hills

High School and 20 students from Fairfax. From 1952 to 1955 Stanford enrolled 13 students

from Beverly Hills High School and 1 from Fairfax.

43

The Registrar’s records do not indicate any

other public schools that experienced such a sharp drop in student enrollments over that same

six-year period or any other six-year period during the 1950s and 1960s.

itineraries and recruiting trip reports from 1954 and 1955 can be found in J. E. Wallace Sterling, President of

Stanford University, Papers (SC0216, Box 7, Folder 17) Department of Special Collections and University Archives,

Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, Calif. None of these mention Beverly Hills or Fairfax. School recruitment

visits were also announced through the Stanford University News Service. Fox example, see Press Release.

October 21, 1953. Stanford University, News Service, Records circa 1891-2013 (SC 0122, Series 1, Box 186, Folder

“Admissions 1949-59: News Releases) Department of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford

University Libraries, Stanford, Calif.

42

Report “Annual Report of the Director of Admissions for the Year 1953-1954.” Rixford K. Snyder. Annual Report

of the President of Stanford University (SC 1103, Box 2, Folder “President's Report Administration 1953-54”)

Department of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, Calif.

43

The date range corresponds to calendar years, while the Registrar’s Office presented its data according to

academic year, so what looks like four calendar years refers to three academic years: 1949-1950, 1950-1951, and

1952. This was the practice throughout the period in question.

23

Though the Registrar’s Office reported enrollments annually, it presented data on high

schools in three-year increments. As a result, each Registrar’s Report does not reflect a single

year’s total but the sum of three years of admissions. The 67 students from Beverly Hills High

School that had enrolled at Stanford (according to the Registrar’s Report of 1952) accounted for

the total number of students over three academic years: 1949-1950, 1950-1951, and 1951-

1952. Similarly, when the Registrar reported in 1955 that Stanford enrolled only a single

student from Fairfax, that, too, reflected the total number of students over three years: 1952-

1953, 1953-1954, and 1954-1955. Given this approach to reporting, it is impossible to ascertain

how many students from any given high school enrolled at Stanford in a particular academic

year.

Additional analyses, however, confirmed both the pattern and the timing of the decline,

suggesting a strong correlation between Snyder’s intention, Glover’s support of it, and the

reduction in students from those two schools who enrolled at Stanford. Though it is impossible

to determine with certainty how many graduates of any particular high school enrolled at

Stanford in any given year, we were able to calculate all of the possible combinations of

admission totals for each of these two high schools for the years in question (a more complete

description of our methods can be found in Appendix C and the data tables for the two high

schools are reproduced in Appendix E and Appendix F).

Our analysis revealed that between 16 and 29 graduates of Beverly Hills High School

enrolled at Stanford in the fall of 1952. One year later, that number dropped to between 0 and

13, which remained the range of possible enrollments for the next three years. Practically the

same story unfolds with respect to Fairfax High School. In 1951-1952, Fairfax sent either eight

24

or nine students to Stanford. The following year, Fairfax sent either a single student or no

students. This pattern persisted for the next three years, with only one or zero Fairfax

graduates enrolling in any given year.

We wish to offer three important caveats in the conclusions we can draw from the data.

First, we have no way of knowing whether or not the students who applied to Stanford from

these schools identified as Jews. We note, however, Snyder’s understanding that these schools

had significant Jewish populations, so we followed his inclination and focused our analysis on

those schools. Second, there is no way of knowing precisely how many students from any

single high school actually enrolled at Stanford during any given year. Third, these data are

based only on the number of students who ultimately enrolled at Stanford. They do not reveal

how many students applied, how many were accepted, and how many opted to attend

elsewhere. The number of admits from a given school or the “yield” of those students (what

was then referred to as the “drop off” rate) were not retained and are not available.

Nevertheless, it seems reasonable to conclude that the sharp drop in enrollments from these

schools reflected a reduction in offers of admission. Furthermore, to have had two schools that

regularly and reliably sent students to Stanford so suddenly reverse course and stop sending

students on its own accord would likely have raised concerns in the Admissions and Registrar’s

offices. We found no evidence of such concerns.

It is worth noting in this regard that enrollments from other public schools that had

significant Jewish student populations remained relatively stable. San Francisco’s Lowell High

School, which was known to attract significant numbers of San Francisco’s Jewish teenagers, did

experience a drop in the number of students it sent, but it was not nearly as sharp as Fairfax

25

and Beverly Hills High Schools. Hamilton High School, which served another Jewish

neighborhood in Los Angeles, saw a slight increase in the number of students it sent to

Stanford, and Hollywood and North Hollywood High Schools consistently sent a small number

of students that was largely unchanged between 1952 and 1955. Beyond California, schools

known to have large Jewish student populations, like New Trier High School (Winnetka, IL),

Garfield High School (Seattle, WA), or Grant and Lincoln High Schools (Portland, OR),

experienced no comparatively sharp decline in the students they sent to Stanford as a result of

Snyder’s intention to limit the number of Jewish students at Stanford (See Appendix D for

enrollment data from selected public high schools).

44

These schools, however, did not have the

density of Jewish students that the two Los Angeles area schools did.

It is unclear how long Snyder’s efforts were in effect, but the repercussions were long

lasting. Over the course of the 1950s and into the 1960s, Beverly Hills High School rebounded

somewhat, possibly sending as many as 21 and as few as 8 students in 1958. But Fairfax never

did. Our estimates suggest that it may have sent between 1 and 3 students each year through

the end of the 1950s.

45

Who Else Knew About Snyder’s Intentions?

Snyder’s intentions with respect to Jewish applicants were not a secret among

Stanford’s leadership. Glover knew about them, thought that they “made sense,” and

44

Masotti, Louis H. 1967. Education and Politics in Suburbia: The New Trier Experience. Cleveland: Press of

Western Reserve University.

45

Again, however, these numbers would not have remained consistent, and a rise one year would have to be

followed by a reduction in following years, in order to match the three-year totals provided in the Registrar’s

Reports.

26

conveyed both his and Snyder’s sentiments to President Sterling. As was common practice at

that time, people in the administration indicated that they had read a particular document by

checking off their initials on a list, usually typed or stamped directly on the document.

According to this convention, we can conclude that the Glover Memo was read by Sterling’s

two secretaries, Marguerite Cole and Lillian Caroline Owen, and by the Provost, Douglas Merritt

Whitaker. Sterling did not indicate that he read the memo, as no check mark appears by his

name. As a result, we cannot definitively conclude that Sterling read the Glover Memo.

The tone and content of the memo, however, indicated that Glover intended it for

Sterling. Glover concluded the memo by stating his intention to “relay these highlights of our

conversation to you [Sterling] and let Rix know if you had different views.” He used a familiar

salutation (“Dear Wally”), adding that this “was a matter requiring the utmost discretion.”

Admissions in Policy and Practice

Identifying others who knew about the Glover Memo contributes a crucial piece of this

larger story, as it illustrates that Snyder acted within the broad mandate of his office and with

the tacit permission of others in the administration. Stanford assigned its Director of

Admissions “the final responsibility for the admission or rejection of all candidates.”

46

Though

Snyder consulted with the Faculty Committee on Admissions, he regularly complained that they

46

Report. Rixford K. Snyder. November 21, 1958. “Annual Report of the Office of Admissions to the President for

the Academic Year 1957-1958.” J. E. Wallace Sterling, President of Stanford University, Papers (SC0216, Box 7,

Folder 18) Department of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, Calif.

27

were not fulfilling their duties.

47

The result was an admissions policy that assigned a great deal

of discretion to the Director of Admissions.

48

Snyder had inherited the ten-point system with its allotment of four points to “personal

qualities” from Grommon and the Registrar’s office.

49

He also inherited a policy that made

explicit his latitude and authority over admissions decisions. A 1945 outline of the

responsibilities of the Admissions Committee assigned it the authority for “adjusting entrance

credentials,” as well as the power to “exercise such discretion as shall subserve the equities in

particular cases without imperiling the general regulation.”

50

In other words, they were given

the power to both set the rules and make exceptions to them.

Snyder relished this policy and Sterling backed Snyder’s efforts to defend the discretion

afforded the Admissions Office throughout his presidency. In 1957, when Stanford published its

first self-study in a volume called The Undergraduate in the University, the faculty committee

behind the study criticized the ten-point scale. Specifically, the faculty committee expressed

47

In one report, Snyder wrote with exasperation, “Again this year, the members of the Faculty Committee on

Admissions failed to read any folders, despite repeated requests to do it.” J. E. Wallace Sterling, President of

Stanford University, Papers (SC0216, Box 7, Folder 18) Department of Special Collections and University Archives,

Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, Calif.

48

In 1959, The Committee on Admissions passed a motion affirming their faith in the Director of Admissions. “We

express our confidence in the Director of Admissions and support him in his use of judgment within the present

limits of his authority.” Excerpts from Minutes of Committee on Admissions. December 22, 1959. J. E. Wallace

Sterling, President of Stanford University, Papers (SC0216, Box A1, Folder 14) Department of Special Collections

and University Archives, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, Calif.

49

Beginning in 1929, Stanford adopted a “personal rating blank” for recommenders to complete. This appears to

have remained in use until the late 1940s when it was phased out in favor of a different approach to

recommendations. For an example of the form, see Patterson, Ruth. 1931. “Evaluation of a Personal Rating Blank

as Used at Stanford for Graduate Students.” Thesis (M.A.), Stanford, CA: Stanford University, School of Education,

page 5. It also asked recommenders to evaluate the student’s “manner and affect,” leadership, initiative (“does he

need constant prodding?”), ability to control emotions, and sense of purpose. It also asks if students have

“superior physique, athletic ability, normal health and strength, frequent sickness, some physical disability.”

50

“By-Laws of the Academic Council.” June 15, 1945. Richard Lyman, President of Stanford University (SC0215,

Series 1, Box 2, Folder: “Enrollment Data: Stanford”). Department of Special Collections and University Archives,

Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, Calif.

28

concerns about the four points allotted to a “personal rating,” which they felt to be “avowedly

subjective: determination of qualification is based upon the joint estimate of high school

counselors and admissions staff members of the student’s character, personality, motivation,

ability to survive at Stanford, anticipated contribution to the University community, and special

talents and abilities.”

51

The faculty committee sought a more formal approach, grounded in an

assessment of applicant qualities that they hoped would predict the likelihood of a student’s

“survival” at Stanford.

Snyder was furious about the report, which he felt did not appreciate the demands of

his office. He stressed that without his “freedom of judgment” Stanford would lose top

candidates from “prestige private schools.” He fiercely defended the admission of athletes, the

allotment of legacy admissions, and his power to admit students who were wealthy and

connected, despite his belief that the faculty “Admissions Committee would reject them.”

Objecting to the imposition of such a system for making admissions decisions, Snyder cracked,

“It is not ‘family-like’ to base all decisions affecting the family according to a formula.” He

saved his choicest criticism for the faculty, whom he deemed “irresponsible.” “They are

exercising authority without assuming the responsibility for their actions,” he continued. “They

will then leave the admissions staff with the responsibility of handling the consequences of

their actions and of explaining them to those affected by them, but with no authority to

51

Hoopes, Robert, and Hubert Marshall. 1957. The Undergraduate in the University: A Report to the Faculty by the

Executive Committee of the Stanford Study of Undergraduate Education, 1954-56. Stanford, Calif: Stanford

University. 18.

29

operate under principles and policies which we sincerely believe to be correct and best for

Stanford.”

52

Sterling supported Snyder in his effort to retain the freedom of his office and avoid what

Sterling thought to be the excessive meddling of the faculty. In a response to Snyder’s memo,

Sterling affirmed both his commitment to the policy and to Snyder’s desire to operate without

excessive faculty oversight. “The policy as stated is clear and agreeable, and I ask that you

utilize it in the administration of admissions to Stanford University. It is my further

understanding that the matter of consulting with the Subcommittee on Undergraduate

Admissions … is at your discretion.”

53

Thus empowered, Snyder continued to resist efforts by the faculty to direct the work of

his office until he resigned as Dean of Admissions in 1969. When Stanford completed its second

campus self-study, which took the form of a ten-volume report known as the “Study of

Education at Stanford” (SES), the faculty again found fault in the ten-point scale and flexibility it

afforded.

54

“The scheme would be more nearly described by a division which gave 4 points to

the prediction of academic achievement and 6 points to the personal ratings.”

55

The

52

Memo. Rixford K. Snyder to Wallace Sterling. February 10, 1958. J. E. Wallace Sterling, President of Stanford

University, Papers (SC0216, Box A1, Folder 14). Department of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford

University Libraries, Stanford, Calif.

53

Memo. Wallace Sterling to Rixford K. Snyder. February 17, 1958. J. E. Wallace Sterling, President of Stanford

University, Papers (SC0216, Box A1, Folder 14). Department of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford

University Libraries, Stanford, Calif. Emphasis added. See also Memo. J. E. Wallace Sterling to Rixford K. Snyder.

January 28, 1960. J. E. Wallace Sterling, President of Stanford University, Papers (SC0216, Box 7, Folder 18)

Department of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, Calif.

54

Stanford University, ed. 1969. The Study of Education at Stanford: Report to the University. Stanford, CA:

Stanford University.

55

“Report to the Humanities and Sciences Faculty,” 1967(?), Office of Undergraduate Admissions, records, 1962-

2020 (SC1750, Folder 7). Department of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford University Libraries,

Stanford, Calif.

30

committee made a number of recommendations to improve the process and, importantly, to

undertake more systematic efforts to recruit minority candidates.

56

As he had a decade earlier, Snyder defended his office, complaining that SES unfairly

characterized his work and the policies that guided it. After a long list of questions and

concerns, Snyder concluded, “What disturbs me most, however, is the unfairness with which

the reports present the current admission procedures and ignore reality in their proposals.”

57

However, he did not just intend to defend the reputation of his office but its role in shaping the

university. He closed his correspondence on the matter by stating his “sincere conviction that

the University’s best interests are jeopardized by the … major recommendations.”

58

Toward the end of his tenure, in response to the changing tides of the campus and the

country, Snyder supported the university’s efforts to recruit more broadly and specifically to

recruit students from minoritized groups. But he also advocated for expanding religious and

geographic diversity, noting that “religious and geographical diversity are synonymous here

since the Jewish and Catholic population are concentrated in the Northeast.”

59

His conflation

56

Stanford University, ed. 1969. The Study of Education at Stanford: Report to the University. Stanford, CA:

Stanford University. 69. In part, the recommendation reads, “We make no recommendation on the number or

proportion of minority-group student Stanford should admit. There are too few now, and we can hardly foresee a

time when there will be too many.”

57

Memo. Rixford K. Snyder to Herbert Packer, Chairman, Steering Committee, Study of Education at Stanford.

September 16, 1968. Stanford University, President’s Office, Sterling-Pitzer Transitional Records 1946-1970

(SC0217, Box 3, Folder 2). Department of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford University Libraries,

Stanford, Calif.

58

Report. “Annual Report of the Office of Admissions to the President for the Academic Year 1957-1958. Rixford K.

Snyder to Provost Fred Terman. November 21, 1958. Annual Report of the President of Stanford University (SC

1103, Box 5, Folder “Administration 1957-58”) Department of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford

University Libraries, Stanford, Calif. See also: Memo. Rixford K. Snyder to Herbert Packer, Chairman, Steering

Committee, Study of Education at Stanford. August 29, 1968. Stanford University, President’s Office, Sterling-Pitzer

Transitional Records 1946-1970 (SC0217, Box 3, Folder 2). Department of Special Collections and University

Archives, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, Calif.

59

Memo. Rixford K. Snyder to Richard Lyman, Vice President and Provost. March 17, 1967. Lyman (Richard W.),

President of Stanford University, Papers 1965-1981 (SC0215, Series 1, Box 1, Folder “Student-Faculty Sub-

31

of religion and demography, though framed within an effort to ensure a diverse student body,

inadvertently echoed his less generous response from the early 1950s. At the beginning of his

term in the Admissions Office, Snyder used demography to stanch the enrollment of Jewish

students; at the end, he employed demography as a recruitment tool. In both cases, however,

demography served as a proxy for identifying Jewish students.

Denial in Practice

Snyder acted with the tacit support of some in the president’s inner circle and within an

Admissions Office that was empowered by a policy that afforded him a great deal of discretion.

This combination of factors created a situation in Stanford admissions wherein Snyder could

reduce or restrict the number of Jewish students at Stanford by targeting specific high schools

known to have significant populations of Jewish students and still claim that the university did

not impose a quota on Jewish students.

University leadership took advantage of this technicality to dismiss claims that they

unfairly restricted admissions of Jewish students. In public statements and private

correspondence, Glover and Snyder each took advantage of the technical distinction between

Stanford’s formal policy and the literal definition of the term “quota” to reject and discredit

concerns about Jewish applicants and students. Sterling took a similar approach, though we

cannot determine whether or not he was acting with knowledge of Snyder’s efforts. When

alumni, parents, the Anti-Defamation League of B’nai B’rith (ADL), and some trustees of the

Committee on Admissions 1967). Department of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford University

Libraries, Stanford, Calif.

32

university inquired about Stanford’s orientation toward admitting Jewish students, Glover,

Snyder, and Sterling rebuffed their concerns, sometimes taking umbrage that such a claim

would even be levied against the institution.

The first such letter we found was written in December 1954, 18 months and two

admissions cycles after the Glover Memo. An alumnus then serving as a judge in the Pacific

Northwest wrote a letter to a member of the Law School faculty sharing that he had heard

word “for more than a year” of Stanford’s quota on Jewish students. At first, he said, he

dismissed the concerns because they came from parents whose children were not accepted to

Stanford and because he knows “how unreliable such statements can be.” But, he observed,

they persisted. “Within the past week,” the author wrote, “two people, neither of whom is

acquainted with the other,” mentioned the limitation on Jewish students. “They also insisted

that the statistics of the entering classes clearly show a sharp drop in the percentage of Jewish

students who are admitted.” He concluded, “If these rumors are false, and I am in a position to

help stop them, I certainly will. However if they are true, I want to know about it.”

60

The letter

was forwarded to Fred Glover.

Glover’s reply was dismissive, describing the ten-point scale in order to explain that

“each applicant to Stanford is considered individually on the same three factors,” before

addressing the charges directly. “We are never accused of being anti-Catholic or anti-

Methodist but the charge does seem to arise sometimes, when a Jewish candidate is involved,

that the University is anti-Jewish.” He went on to explain that the university’s admissions

60

Letter. Gus Solomon to James Brenner, Stanford Law School. December 6, 1954. Lyman (Richard W.), President

of Stanford University, Papers 1965-1981 (SC0215, Box 10, Folder “Discrimination: Religious (Incl. Jewish)”)

Department of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, Calif.

33

procedures do not ask about religion, race, or “social background,” so “if anyone has statistics

on the proportion of Jewish students entering Stanford, the figures are not Stanford’s.” He

added, “If we had such information, we could defend ourselves better against charges of

discrimination, but if we maintained it, we would be open to charges that we kept the data to

establish quotas.” He closed the letter by extending his sympathies and offering a note of

cooperation and goodwill. “It disturbs us deeply to have such rumors circulating as you have

heard, and I hope that the above information will answer the questions which have been raised

in your own mind.”

61

In his reply, Glover also noted that this was not the first time Stanford was accused of

employing an “anti-Jewish” policy. He revealed that Stanford had recently been the subject of

an investigation by the ADL that focused on its use of quotas, but that “the University was

cleared of any anti-Jewish discrimination.” Glover tried to further minimize the judge’s

concerns by stating that “the source of these rumors is very likely the same as” those which led

to the first investigation, suggesting that they were hearing different accounts of the same

incident and that they not be taken too seriously. In dismissing the judge’s concerns, Glover did

not mention what he knew to be true: that the Admissions Office engaged in practices,

congruent with policy, that were intended to suppress the number of Jewish students at