NORTH CAROLINA JOURNAL OF LAW & NORTH CAROLINA JOURNAL OF LAW &

TECHNOLOGY TECHNOLOGY

Volume 23 Issue 2 Article 3

12-1-2021

Stating it Simply: A Comparative Study of the Quantitative Stating it Simply: A Comparative Study of the Quantitative

Readability of Apex Court Decisions from Australia, Canada, Readability of Apex Court Decisions from Australia, Canada,

South Africa, the United Kingdom, and the United States South Africa, the United Kingdom, and the United States

Mike Madden

Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncjolt

Part of the Law Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Mike Madden,

Stating it Simply: A Comparative Study of the Quantitative Readability of Apex Court

Decisions from Australia, Canada, South Africa, the United Kingdom, and the United States

, 23 N.C. J.L. &

TECH. 270 (2021).

Available at: https://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncjolt/vol23/iss2/3

This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. It has been

accepted for inclusion in North Carolina Journal of Law & Technology by an authorized editor of Carolina Law

Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected].

NORTH CAROLINA JOURNAL OF LAW & TECHNOLOGY

VOLUME 23, ISSUE 2: DECEMBER 2021

270

STATING IT SIMPLY: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF THE

QUANTITATIVE READABILITY OF APEX COURT DECISIONS FROM

AUSTRALIA, CANADA, SOUTH AFRICA, THE UNITED KINGDOM,

AND THE UNITED STATES

Mike Madden*

Even though common law courts create and articulate the law

within their decisions, surprisingly little is known about the

quantitative readability levels of any single national apex court’s

decisions, and even less is known about how any one apex court’s

readability levels compare to those of other similar apex courts.

This Article offers new data and analysis that significantly reduces

the blind spots in these areas by reporting the results of an original

empirical study of the readability of judicial decisions released in

2020 from the apex courts of five English-speaking jurisdictions.

This Article draws on applied linguistics theory and Natural

Language Processing techniques in order to provide both uni- and

multi-dimensional readability scores for the 233 judicial decisions

(comprising more than 3 million words of text) that form the corpus

of this study. The results show that readability levels vary by

approximately 50% between the most- and least-readable

jurisdictions (the United States and Australia, respectively). This

Article then analyzes the data comparatively in order to determine

whether institution- or jurisdiction-specific factors are capable of

explaining readability variances between the different courts. This

*

Ph.D. Student, University of Ottawa Faculty of Law, and graduate student

member of the Centre for Law, Technology and Society at the Faculty of Law at

the University of Ottawa in Ottawa, Canada. The author wishes to thank Professor

Nina Varsava, University of Wisconsin-Madison Law School, for her helpful

feedback on an earlier draft of this Article. The author also wishes to thank Dr.

Elizabeth F. Judge for her feedback on this Article, and her exceptional Ph.D.

supervision more generally. Finally, the author is grateful for the generous support

of the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC),

whose award of a Joseph-Armand Bombardier Canada Graduate (Doctoral)

Scholarship facilitated this research.

DEC. 2021] Quantitative Readability 271

Article concludes that certain comparative factors, such as the

average panel size used by each court and the ratios of both former

law professors and women who sit on panels in each jurisdiction,

can explain 23.7% of the total variances in readability scores. These

findings may help judicial branch and executive branch decision-

makers better understand how their court’s decisions “stack up”

against other courts in terms of readability and offer insights into

how readability levels could be enhanced.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................272

II. BACKGROUND & CONTEXT: READABILITY, LAW, AND THE

COMPARATIVE METHODOLOGY ........................................275

A. Understanding Quantitative Readability ........................275

B. What Is Already Known About the Readability of Law ..282

C. Relative Readability and the Comparative Methodology

......................................................................................285

III. STUDY DESIGN AND METHOD ...............................................287

A. Study Design ...................................................................287

1. Selecting the Level of Court to Study ........................287

2. Selecting Jurisdictions for the Study .........................288

3. Identifying Relevant Linguistic and Readability

Measures .................................................................289

4. Identifying Variables for Comparison ......................292

B. Method ............................................................................294

1. Case Selection and Acquisition .................................294

2. Data Pre-Processing .................................................295

3. Processing Tools, NLP Computations, and Exclusions

................................................................................296

4. Data Collection and Coding of Variables ................297

5. Descriptive and Analytical Statistical Techniques ...298

C. Limitations of the Study ..................................................299

IV. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION ....................................................300

A. Results: Reporting Linguistic and Readability Measures

......................................................................................301

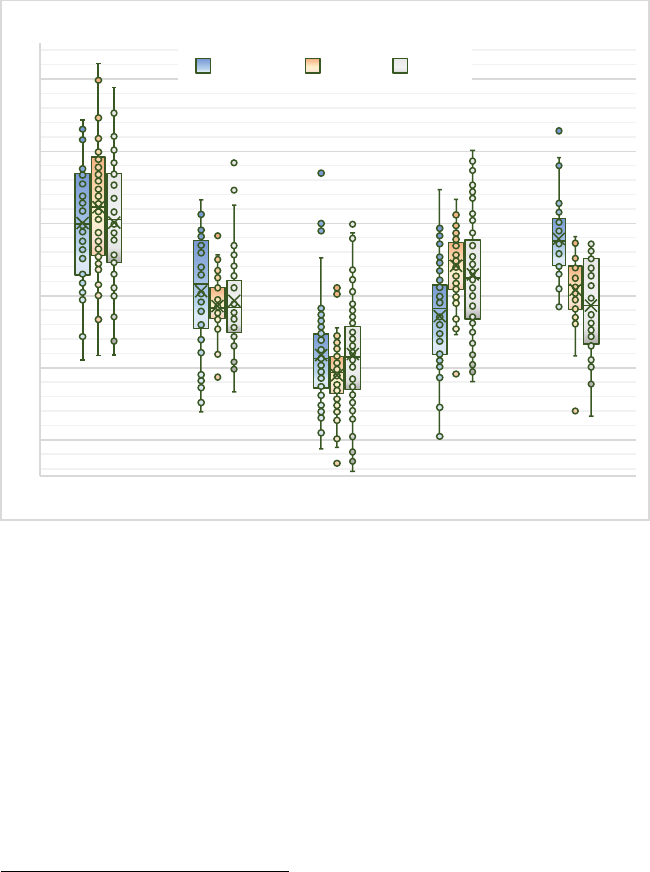

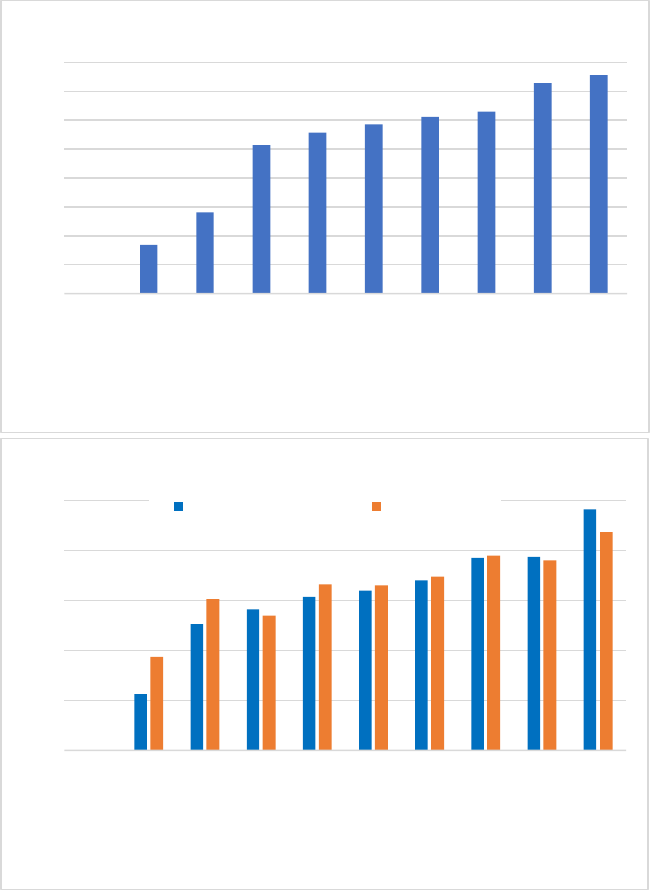

1. Decision Length ........................................................301

2. Average Concreteness for Content Words ................306

272 N.C. J.L. & TECH. [VOL. 23: 2

3. Average Frequency for Function Words—COCA

Academic Corpus ....................................................308

4. Average Proportion of Bigrams – Top 20,000 – COCA

Fiction Corpus ........................................................310

5. Readability Scores: CAREC-M, Flesch-Kincaid, and

SMOG .....................................................................313

B. Discussion: Comparative Analysis of Readability Results

......................................................................................319

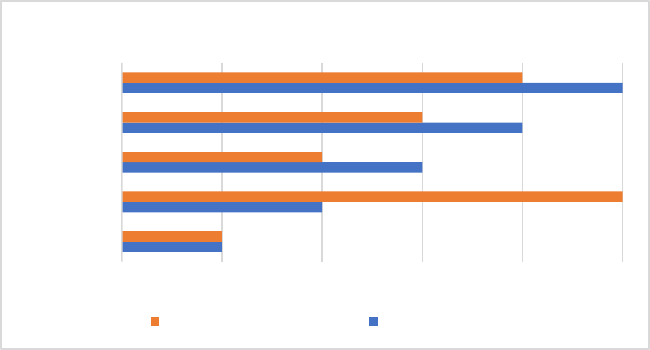

1. Adult Secondary School Completion Rate ................320

2. Clerk Involvement .....................................................321

3. Court Politicization ..................................................325

4. Panel Size ..................................................................328

5. Former Law Professors per Judge ...........................329

6. Degrees per Judge ....................................................331

7. Women per Judge ......................................................332

8. Multivariable Modeling to Explain Readability

Variances ................................................................333

V. CONCLUSION ...........................................................................335

I. INTRODUCTION

Legal theorists and rule of law scholars generally agree that one

requirement of a functioning legal system is that the system’s laws

must be knowable to those governed by the law.

1

In jurisdictions

wherein ‘law’ comprises not only legislation, but also common law

principles and rules that courts have set down in their judicial

decisions, stakeholders may find it important to consider the extent

to which the common law is ascertainable to the population. Many

common law judges and scholars explicitly acknowledge their

obligations to produce readable, accessible decisions and recognize

that their audiences are broad: judges must not only communicate to

the specific litigants, one another, and the legal profession, but also

1

LON L. FULLER, THE MORALITY OF LAW 39 (rev. ed. 1969); JOSEPH RAZ, THE

AUTHORITY OF LAW: ESSAYS ON LAW AND MORALITY 213–15 (1979); JOHN

RAWLS, A THEORY OF JUSTICE 209 (1999).

DEC. 2021] Quantitative Readability 273

to the citizenry as a whole.

2

Additionally, scholars are beginning to

note how an inability to read relevant legal materials (like case law)

can present significant “access to justice” barriers for citizens

generally, but in particular, for self-represented litigants, who need

to understand the law that applies to their cases.

3

Although one could

perhaps argue for less-publicly understandable laws,

4

this Article

begins from the assumption (grounded in “rule of law” theory)

5

that

it is inherently beneficial for the common law to be more—rather

than less—readable, and that, in any case, there is value in knowing

how readable judicial decisions are as a baseline fact.

How well are common law courts actually achieving the

objective of producing readable statements of the law? Perhaps

surprisingly, very little effort appears to have been made toward

answering this question, at least from an empirical or quantitative

perspective. This Article makes several further steps in that direction

by reporting the results of an original comparative readability study

that measures the quantitative readability of apex court decisions

released between January 1, 2020, and December 31, 2020, from

Australia (N = 46), Canada (N = 34), South Africa (N = 30), the

United Kingdom (N = 54), and the United States (N = 69), using a

variety of applied linguistics metrics. Additionally, by examining or

measuring how environment- and court-specific factors also differ

2

See, e.g., Gerald B. Wetlaufer, Rhetoric and Its Denial in Legal Discourse, 76

VA. L. REV. 1545, 1561 (1990); see The Honourable Nicholas Kasirer’s

Questionnaire (Questionnaire for the Supreme Court of Canada Judicial

Appointment Process), OFF. OF THE COMM’R FOR FED. JUD. AFF., Part 10(4) (Apr.

18, 2019), https://www.fja.gc.ca/scc-csc/2019/nominee-candidat-eng.html

[https://perma.cc/4MVT-MSNB]; see also The Honourable Justice David M

Paciocco’s Questionnaire (Questionnaire for Judicial Appointment), GOV’T OF

CAN., Part 11(4) (Apr. 7, 2017) http://www.canada.ca/en/department-

justice/news/2017/04/the_honourable_justicedavidmpacioccosquestionnaire.html

[https://perma.cc/6TG8-JBCN].

3

Patricia Hughes, Advancing Access to Justice through Generic Solutions: The

Risk of Perpetuating Exclusion, 31 WINDSOR Y.B. ACCESS JUST. 1, 13–15 (2013).

4

See Rabeea Assy, Can the Law Speak Directly to Its Subjects - The Limitation

of Plain Language, 38 J.L. & SOC’Y 376 (2011) (discussing how efforts to make

the law more readable may compromise legal clarity and precisions, ultimately

arguing that it is futile to hope that the law can be broadly accessible, without the

assistance of legal professionals, to average citizens).

5

FULLER, supra note 1, at 39.

274 N.C. J.L. & TECH. [VOL. 23: 2

across the five studied jurisdictions, this Article assesses how these

comparative factors may explain readability variances across the

jurisdictions.

The results of this study show that there are substantial variances

in quantitative readability levels across the five jurisdictions, of

approximately 50% in mean readability levels between the most-

and least-readable jurisdictions, based on two different

comprehensive readability formulae.

6

Furthermore, these results

show that statistically significant correlations of moderate effect size

exist between a decision’s readability level and the number of judges

on the panel,

7

the number of former law professors on the panel,

8

and the number of women on the panel.

9

Using these three factors

as independent variables and the decision readability scores as the

dependent variable, a multiple regression analysis yielded a

statistically significant model capable of explaining 23.7% of the

variance in readability scores.

10

In other words, jurisdiction-specific

and court-specific factors that are particular to the different apex

courts accounted for almost one quarter of the readability

differences in decisions from these courts.

The results of this study can assist legal scholars in better

understanding some of the factors that may be influencing

readability levels of apex court decisions within a given jurisdiction.

This understanding may, in turn, permit key officials within

governments (such as those responsible for appointing judges) and

judicial executives (such as Chief Justices who assign judges to

preside on particular panels) to act in ways that could support the

production of more readable judicial decisions in the future.

Ultimately, however, the results of this study offer only a partial

explanation for variations in readability levels across jurisdictions

and suggest that other factors (perhaps more related to the identity

of the author of a decision than to the court or jurisdiction from

6

See infra Table 5 and associated text.

7

See infra Table 6 and associated text.

8

See infra Table 7 and associated text.

9

See infra Table 9 and associated text.

10

See infra Table 10 and associated text.

DEC. 2021] Quantitative Readability 275

which the decision emerges) may better explain the readability

variances.

This Article begins in Part II with a brief discussion of the

relevant background and context of the current study. Part III

describes the design and method of the study, including its

limitations. Part IV presents and discusses the results of the study,

including measurements and observations of the studied apex courts

and their operating environments, as well as both descriptive and

analytical statistics relating to readability measures of the decisions

produced by these courts. This Article concludes by reiterating its

principal finding: readability differences between apex courts in

different countries can be explained, in part, by reference to

comparative factors; however, future studies that focus more on

characteristics of the individual authors of judicial decisions, as

opposed to characteristics of their working environments, could

provide a better understanding of additional sources of variance.

II. BACKGROUND & CONTEXT: READABILITY, LAW, AND

THE COMPARATIVE METHODOLOGY

In order to situate the present study within its appropriate

context, some explanations about the concept of quantitative

readability and its relevance to the law would be helpful. It is also

important to understand how a comparative methodology can be

applied to this topic in order to generate a set of useful findings, as

well as how such a methodology will differ in its focus and results

from a more “law and language” methodology. Consequently, this

Part: (A) introduces the concept of readability; (B) summarizes the

existing literature that focuses on the readability of court decisions;

and, (C) explains how a comparative methodology can be employed

in order to increase our understanding of apex court readability

levels.

A. Understanding Quantitative Readability

Readability, for the purposes of this study, refers to text-centered

assessments of how easy or difficult, from a cognitive perspective,

texts are to read and understand for non-specific readers. This sense

of the term “readability” is consistent with how the term is used

within the fields of education and linguistics, where “readability”

276 N.C. J.L. & TECH. [VOL. 23: 2

has been defined as the quality that “makes some texts easier to read

than others”

11

and as “the sum total (including all the interactions)

of all those elements within a given piece of printed material that

affect the success a group of readers have with it.”

12

Readability, here, is not concerned with text legibility (i.e., the

extent to which the visual layout and presentation of a text facilitate

reader processing of that text), even though text legibility likely has

an impact on the physical or optical level of effort involved in

reading.

13

Instead, the readability dimensions of the present study

focus on the relative level of cognitive effort that a generic reader

would require to understand particular texts.

In this sense, readability is an objective but somewhat abstract

concept, offering a relative and general measure of how

comprehensible a text will be; readability does not, for instance,

account for reader-specific factors, such as a reader’s interest in the

text, education level, or familiarity with the subject matter.

Readability, then, says nothing about whether a particular individual

will actually understand a particular text; instead, readability

determines, in broad terms, whether more or fewer people are likely

to understand a specific text based on the language-related

properties of that text. Readability is therefore a useful concept

when considering texts that are intended for broad, heterogeneous

groups, or for groups whose characteristics are fluid or otherwise

not well-understood, because readability measurements should

determine whether one text is more or less likely to be understood

than another text—even if not much is known about the world of

potential readers of the texts. Since judicial decisions, written for

11

WILLIAM H. DUBAY, THE PRINCIPLES OF READABILITY 3 (2004).

12

Edgar Dale & Jeanne S. Chall, The Concept of Readability, 26 ELEMENTARY

ENG. 19, 23 (1949).

13

See Mark Sableman, Typographic Legibility: Delivering Your Message

Effectively, 17 SCRIBES J. OF LEGAL WRITING 9, 15–17 (2017); see also Mary

Alton Mackey & Marilyn Metz, Ease of Reading of Mandatory Information on

Canadian Food Product Labels, 33 INT’L J. CONSUMER STUD. 369, 371–72

(2009) (noting how typeface, color, contrast levels, and text placement can each

impact elements of readability); see generally Khaled Moustafa, Improving PDF

Readability of Scientific Papers on Computer Screens, 35:4 BEHAVIOUR & INFO.

TECH. 319 (2016) (describing how the column-based display of text within PDF

files on computer screens can inhibit readability of the text).

DEC. 2021] Quantitative Readability 277

broad and diverse audiences, fall within this category of text, there

are clear benefits to studying the readability levels of these texts.

Readability may be assessed quantitatively, qualitatively, or

through some combination of these methods. For instance, in

Crossley, Skalicky, and Dascalu’s study, the authors first used

crowd-sourced pairwise (qualitative) comparisons of side-by-side

texts in order to determine the relative readability levels of

approximately 600 texts.

14

Next, the authors (quantitatively) studied

the linguistic properties of two-thirds of these texts to derive,

through regression analysis, a readability formula that could

accurately predict text readability.

15

Finally, the authors

(quantitatively) tested their readability formula on the remaining

one-third of the texts and found that their formula validly predicted

the relative readability of these texts.

16

As this example illustrates,

quantitative readability formulae can be anchored in real-world,

human-involved, qualitative assessments of text readability (like a

pairwise comparison, or a reader comprehension test)—although a

quantitative readability formula can subsequently be applied on its

own once this anchor has been established and once the formula has

been validated.

17

The present study centers around the quantitative

readability of apex court decisions. Accordingly, the remainder of

the ensuing discussion focuses on the necessary background for

understanding quantitative, rather than qualitative, readability

concepts.

This Article does not explore the entire history of quantitative

readability studies in English, but these studies have been numerous

and varied. One of the earliest and most well-known readability

14

Scott A. Crossley, Stephen Skalicky & Mihai Dascalu, Moving Beyond

Classic Readability Formulas: New Methods and New Models, 42 J. RSCH.

READING 541, 546–49 (2019) (conducting a study for the purpose of developing

new readability models that identify linguistic features in texts that affect text

comprehension and reading speed).

15

Id. at 549–52.

16

Id. at 551–57.

17

See John C. Roberts, Robert H. Fletcher & Suzanne W. Fletcher, Effects of

Peer Review and Editing on the Readability of Articles Published in Annals of

Internal Medicine, 272:2 JAMA 119 (1994), for an example of such a study that

relies on previously-validated readability formulae (concluding that peer review

improves readability of manuscripts).

278 N.C. J.L. & TECH. [VOL. 23: 2

formulae to emerge from these studies was developed (or modified

from its earlier form) in 1948 by Rudolph Flesch.

18

Flesch’s

“Reading Ease” formula used counts of average syllables per 100

words and average words per sentence, together with a constant, to

give readability scores to texts on a scale of 1 to 100.

19

A score of

100 “corresponds to the prediction that a child who has completed

fourth grade will be able to answer correctly three-quarters of the

test questions to be asked about the passage that is being rated,”

20

while a score of 0 signifies a text that is “practically unreadable.”

21

The Flesch Reading Ease formula continues to be used within

popular word processing software applications, such as Microsoft

Word and Google Docs.

22

Many other formulae relying on similar analytical techniques to

produce readability measurements were introduced after the Flesch

Reading Ease formula between 1948 and 1995. Robert Gunning

developed the Gunning FOG Index in 1952, which measured

readability based on average sentence length, and average number

of words with three or more syllables (subject to some limited

exceptions) per 100 words.

23

The Automated Readability Index,

developed in 1967, relied on measures of words per sentence, and

characters per word, to produce an estimated reading grade level of

a text.

24

The Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level Score similarly relied on

measures of words per sentence and syllables per word to produce

an estimated reading grade level of a text.

25

Dale and Chall

18

Rudolph Flesch, A New Readability Yardstick, 32 J. OF APPLIED PSYCH. 221,

221–22 (1948).

19

Id. at 228–29.

20

Id. at 225.

21

Id. at 229.

22

See, e.g., Richard Johnson, How to Apply the Flesch Kincaid Readability

Formula to Your Content, OPTIMONK (Oct. 12, 2021),

https://www.optimonk.com/how-to-apply-the-flesch-kincaid-readability-

formula-to-your-content/ [https://perma.cc/5EP9-2T5F] (describing how to

access this readability formula in both Microsoft Word and Google Docs).

23

ROBERT GUNNING, THE TECHNIQUE OF CLEAR WRITING 35–37 (1952).

24

R.J. SENTER & E.A. SMITH, AUTOMATED READABILITY INDEX 7–12

(Aerospace Med. Rsch. Lab’y’s 1967).

25

J. PETER KINCAID ET AL., NAVAL TECHNICAL TRAINING COMMAND,

DERIVATION OF NEW READABILITY FORMULAS FOR NAVY ENLISTED PERSONNEL

14 (1975).

DEC. 2021] Quantitative Readability 279

(originally in 1948, shortly after Flesch introduced his Reading Ease

Formula) were unsatisfied with using word length as a proxy

measurement for word difficulty and therefore developed a

readability formula that relied on measures of average sentence

length, as well as a ratio of difficult words in the text (i.e., words not

listed within a 3,000-word list of commonly used words).

26

As computing power increased and computers generally became

more accessible, scholars began to employ (computer-based)

Natural Language Processing (“NLP”) techniques to derive and

apply readability measures.

27

For instance, the freely-available, web-

based Coh-Metrix 1.0 software tool was introduced in 2004 and was

intended to analyze “texts on multiple levels of language, discourse,

cohesion, and world knowledge.”

28

The tool computed both the

Flesch Reading Ease Score and the Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level

Score, while also measuring many other novel dimensions of a text

that were thought to be related to text comprehension and

complexity, including scores related to lexical diversity (the ratio of

unique words to total words),

29

word frequency (how commonly a

word occurs in the English language, as assessed based on

occurrences within large representative corpora of text),

30

concreteness (“how concrete or nonabstract a word is, on the basis

of human ratings”),

31

and cohesion (the overlap of words or ideas

across sentences, paragraphs, and the text as a whole).

32

The creators

of Coh-Metrix 1.0 continued to refine the tool from 2002 to 2011

33

in an effort to better predict deep comprehension of texts, instead of

the kind of “surface comprehension” that traditional readability

26

Edgar Dale & Jeanne S. Chall, A Formula for Predicting Readability, 27

EDUC. RSCH. BULL. 11, 15–18 (1948).

27

Arthur C. Graesser et al., Coh-Metrix: Analysis of Text on Cohesion and

Language, 36 BEHAV. RSCH. METHODS, INSTRUMENTS, & COMPUTS. 193, 201

(2004).

28

Id.

29

Id. at 198.

30

Id. at 197.

31

Id. at 196.

32

Id. at 199–201.

33

DANIELLE S. MCNAMARA ET AL., AUTOMATED EVALUATION OF TEXT AND

DISCOURSE WITH COH-METRIX 1–2 (2014).

280 N.C. J.L. & TECH. [VOL. 23: 2

formulae had predicted.

34

The current Coh-Metrix 3.0 web tool

35

now offers a Text Ease and Readability Assessor that groups

together different measures into five broad categories—narrativity,

syntactic simplicity, word concreteness, referential cohesion, and

deep cohesion—and gives a percentile score for each category in

order to show how the sample text compares with over 37,000 other

texts drawn from a broad reference corpus.

36

The Coh-Metrix tool is responsive in many ways to criticisms of

older readability formulae.

37

Namely, these formulae all rely on the

same two types of simple semantic and syntactic measures—

vocabulary difficulty (for which word length is often a proxy) and

syntactic complexity (for which sentence length is often a proxy)—

that are not always, only, or equally responsible for text

comprehension variances.

38

By introducing measures of narrativity

and cohesion, and by relying on more direct measures of semantic

difficulty (e.g., using word frequency instead of word length), the

Coh-Metrix tool “is motivated by theories of discourse and text

comprehension. Such theories describe comprehension at multiple

levels, from shallow, text-based comprehension to deeper levels of

comprehension that integrates multiple ideas in the text.”

39

In other

words, the Coh-Metrix tool represents an attempt to better measure

the various properties of a text that reading and discourse theory

suggest are actually influential in promoting or inhibiting one’s

understanding of a text.

New readability formulae that rely upon NLP techniques to

measure linguistic properties of both subject texts (i.e., the ones that

are relevant in a given study) and reference texts (i.e., the ones

typically organized as large corpora that provide a basis for

34

Danielle S. McNamara & Arthur C. Graesser, Coh-Metrix: An Automated Tool for

Theoretical and Applied Natural Language Processing, in APPLIED NATURAL

LANGUAGE PROCESSING: IDENTIFICATION, INVESTIGATION, AND RESOLUTION 188, 200

(Philip M. McCarthy & Chutima Boonthum-Denecke eds., 2012).

35

The Coh-Metrix 3.0 web tool is available at www.cohmetrix.com

[https://perma.cc/QML8-ZE3S].

36

MCNAMARA ET AL., supra note 33, at 76–77, 84–95.

37

ALAN BAILIN & ANN GRAFSTEIN, READABILITY: TEXT AND CONTEXT 53–54 (2016).

38

Id.

39

McNamara & Graesser, supra note 34, at 197.

DEC. 2021] Quantitative Readability 281

comparison), together with qualitative assessments of text

complexity or comprehension, now emerge regularly.

40

However,

some debate continues to exist about the usefulness of such

quantitative readability studies. Professors Bailin and Grafstein, for

instance, abandon the idea of studying readability from a

quantitative perspective altogether and instead encourage discussion

of the qualitative aspects of text properties that tend to facilitate or

impede comprehension.

41

Professors Davison and Kantor, in their

study of four texts that were rewritten in order to simplify the texts,

found that the changes did not necessarily lead to better readability

scores, mainly because the readability formulae failed to account for

important non-quantitative factors that contribute to

comprehension.

42

More recently, scholars have begun to note that

weaknesses in quantitative readability measurements may exist due

to weaknesses in the underlying qualitative (human-involved)

assessments of readability (or “criterion variables”), which ground

40

See, e.g., Scott A Crossley et al., Predicting the Readability of Physicians’

Secure Messages to Improve Health Communication Using Novel Linguistic

Features: Findings from the ECLIPPSE Study, 13 J. COMMC’N. HEALTHCARE

344, 346–53 (2020) (showing the results of a study, performed by the authors, of

the linguistic properties of 724 secure messages sent by physicians to patients that

had been ranked on their readability by a panel of expert raters, to derive a

readability formula that validly predicts message readability in this specialized

medical context); see also Nils Smeuninx, Bernard De Clerck & Walter Aerts,

Measuring the Readability of Sustainability Reports: A Corpus-Based Analysis

Through Standard Formulae and NLP, 57 INT’L J. BUS. COMMC’N. 52, 58–79

(2020) (assessing the readability of private-sector business reports through

measures of lexical density, subordinate clause use, and passive voice use,

alongside other classic readability formulae).

41

BAILIN & GRAFSTEIN, supra note 37, at 53–54.

42

Alice Davison & Robert N. Kantor, On the Failure of Readability Formulas

to Define Readable Texts: A Case Study from Adaptations, 17 READING RESCH.

Q. 187, 207 (1982) (“[T]here are features of texts which contribute to readability

and that these have not been given their due as factors entering into the question

of readability. They are difficult to quantify, and in many cases are only recently

beginning to be understood by linguists, cognitive psychologists, and others

interested in the analysis of discourse. Yet features of topic, focus, inference load,

and point of view play important roles in comprehension, which are all the more

crucial to identify because their effects are subtle.”).

282 N.C. J.L. & TECH. [VOL. 23: 2

the formulae.

43

For example, if multiple-choice reading

comprehension tests or fill-in-the-missing-word tests—commonly

used to norm a readability formula—are not actually valid measures

of comprehension, then the formula itself is also likely invalid.

44

Notwithstanding these criticisms, quantitative readability

studies continue to be conducted across a wide variety of

disciplines,

45

supporting both private sector

46

and public sector

47

needs. The present study accepts that quantitative readability studies

cannot provide a perfect truth on questions relating to the

comprehensibility of a text, but these studies can offer some useful

indicators about readability levels of texts—particularly for

comparative assessments of readability between different texts or

text sets.

B. What Is Already Known About the Readability of Law

Much has been written about readability and the plain language

movement—an effort to promote more effective communication

that, in many ways, implicates concepts of readability—in the

43

James W. Cunningham, Elfrieda H. Hiebert & Heidi Anne Mesmer,

Investigating the Validity of Two Widely Used Quantitative Text Tools, 31

READING & WRITING 813, 814–18 (2018).

44

Id. at 830–31.

45

See, e.g., Matthew R. Edmunds, Robert J. Barry & Alastair K. Denniston,

Readability Assessment of Online Ophthalmic Patient Information, 131 JAMA

OPHTHALMOLOGY 1610, 1611–15 (2013) (discussing health care); see Scott W.

Davis et al., Say What? How the Interplay of Tweet Readability and Brand

Hedonism Affects Consumer Engagement, 100 J. BUS. RSCH. 150, 154–57 (2019)

(discussing social media marketing); see also George R. Milne, Mary J. Culnan

& Henry Greene, A Longitudinal Assessment of Online Privacy Notice

Readability, 25 J. PUB. POL’Y & MKTG. 238, 241–45 (2006) (discussing consumer

privacy).

46

See, e.g., Gene E. Burton, The Readability of Consumer-Oriented Bank

Brochures: An Empirical Investigation, 30 BUS. & SOC’Y 21, 23–25 (1991).

47

See, e.g., Alexandre Deslongchamps, Readability and the Bank of Canada,

BANK OF CANADA STAFF ANALYTICAL NOTE 2018–20, June 2018,

https://www.bankofcanada.ca/2018/06/staff-analytical-note-2018-20

[https://perma.cc/6S8L-SGXH].

DEC. 2021] Quantitative Readability 283

contexts of legislative drafting,

48

jury instructions,

49

and the drafting

of legal forms

50

or court briefs.

51

Some of this type of work has

involved quantitative readability measures,

52

and/or other forms of

empirical analysis.

53

Much of the scholarship focuses on American

law, but studies of readability in law also appear within works from

other countries.

54

Not all of the studies view readability or plain

language efforts as being useful to the law.

55

There appears to have been far fewer studies on the readability,

or plain language, of judicial decisions. Of the quantitative

readability studies that have been conducted, some have analyzed

the writing styles of individual judges, looking at their

idiosyncrasies—particularly of judges who are thought to display

48

See, e.g., Ruth Sullivan, The Promise of Plain Language Drafting, 47

MCGILL L.J. 97, 101–08 (2001); see also David St. L. Kelly, Legislative Drafting

and Plain English, 10 ADEL L. REV. 409 (1986) (discussing options for plain

language reforms to Australian statutory laws).

49

See, e.g., Robert P. Charrow & Veda R. Charrow, Making Legal Language

Understandable: A Psycholinguistic Study of Jury Instructions, 79 COLUM. L.

REV. 1306, 1308–11 (1979).

50

See, e.g., Charles R. Dyer et al., Improving Access to Justice: Plain Language

Family Law Court Forms in Washington State, 11 SEATTLE J. SOC. JUST. 1065.

1082–95 (2013).

51

See, e.g., Robert W. Benson & Joan B. Kessler, Legalese v. Plain English:

An Empirical Study of Persuasion and Credibility in Appellate Brief Writing, 20

LOY. L.A. L. REV. 301, 305–12 (1987).

52

See, e.g., Lance N. Long & William F. Christensen, Does the Readability of

Your Brief Affect Your Chance of Winning an Appeal?, 12 J. APP. PRAC. &

PROCESS 145, 154–56 (2011).

53

See, e.g., Maria Mindlin, Is Plain Language Better? A Comparative

Readability Study of Court Forms, 10 SCRIBES J. LEGAL WRITING 55, 58–60

(2006).

54

See, e.g., I. Turnbull, Legislative Drafting in Plain Language and Statements

of General Principle, 18 STATUTE L. REV. 21 (1997) (U.K.); see also Jeffrey

Barnes, When Plain Language Legislation is Ambiguous – Sources of Doubt and

Lessons for the Plain Language Movement, 34 MELB. U.L. REV. 671, 704–07

(2010) (Austl.) (noting how plain language reforms, alone, cannot resolve most

questions of ambiguity within Australian statutes).

55

See Louis J. Sirico, Jr., Readability Studies: How Technocentrism Can

Compromise Research and Legal Determinations, 26 QUINNIPIAC L. REV. 147,

169–70 (2007).

284 N.C. J.L. & TECH. [VOL. 23: 2

excellent writing styles.

56

One qualitative study examined the use of

plain language techniques by the Supreme Court of the United States

(“SCOTUS”) during the tenure of Chief Justice Roberts.

57

DeFriez’s

unpublished doctoral thesis studied—both qualitatively and

quantitatively—a sample of 371 Idaho Supreme Court decisions

released between 1891 and 2017 and found that the decisions

became more readable over time.

58

However, the only published,

large-scale quantitative study to consider the readability of any

national apex court’s decisions was Whalen’s 2015 study of 6,206

SCOTUS decisions released since 1946.

59

Whalen calculated the

Simple Measure of Gobbledygook (“SMOG”)

60

scores for these

decisions and found that: (1) decisions were becoming less readable

over time;

61

(2) individual judges’ decisions became less readable

the longer the judges served on the court;

62

and, (3) conservative

judges wrote slightly less readable opinions than liberal judges.

63

No study to date has quantitatively examined the readability of

apex (or other) court decisions from a comparative perspective.

Similarly, no published study to date has quantitatively assessed the

overall readability of decisions from any of the High Court of

Australia (“HCA”), the Supreme Court of Canada (“SCC”), the

Constitutional Court of South Africa (“ZACC”), or the Supreme

56

See, e.g., Brady Coleman, Lord Denning & Justice Cardozo: The Judge as

Poet-Philosopher, 32 RUTGERS L.J. 485 (2001); see also Nina Varsava, Elements

of Judicial Style: A Quantitative Guide to Neil Gorsuch’s Opinion Writing, 93

N.Y.U. L. REV. ONLINE 75, 85–106 (2018) (reporting the results of a stylometric

study of Justice Gorsuch’s writing and finding that Justice Gorsuch’s reputation

as an excellent writer is empirically borne out within the study).

57

David A. Strauss, The Plain Language Court, 38 CARDOZO L. REV. 651 (2016).

58

Brian M. DeFriez, Toward a Clearer Democracy: The Readability of Idaho

Supreme Court Opinions as a Measure of the Court’s Democratic Legitimacy

(2017) (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Idaho) (ProQuest).

59

Ryan Whalen, Judicial Gobbledygook: The Readability of Supreme Court

Writing, 125 YALE L.J. F. 200, 202–10 (2016).

60

SMOG is a quantitative readability formula that is calculated based on the

number of three- (or more) syllable words within a thirty-sentence sample, first

introduced in 1969. See G. Harry McLaughlin, SMOG Grading – A New

Readability Formula, 12 J. READING 639, 641 (1969).

61

Whalen, supra note 59, at 202–04.

62

Id. at 204–06.

63

Id. at 208–10.

DEC. 2021] Quantitative Readability 285

Court of the United Kingdom (“UKSC”). Therefore, the present

study offers new insight about the readability levels of decisions

from individual apex courts and how these levels compare with one

another across national jurisdictions.

C. Relative Readability and the Comparative Methodology

Although some readability formulae purport to suggest a reading

grade level or an approximate education level needed by a reader to

comprehend a given text,

64

these suggestions are somewhat

unhelpful because the suggested levels can vary by several grades

for a particular text depending on which formula is used.

65

Furthermore, many readability formulae do not attempt to

benchmark their scores to particular education or grade levels.

66

In

other words, knowing an absolute readability score for a particular

text, in isolation, is not necessarily meaningful. However, knowing

the readability score for a particular text (or group of texts) relative

to another text (or group of texts) could be especially useful. For

instance, knowing that a document scores a 78 on a readability scale

does not tell one much; however, knowing that the same document

scores a 78 when most other similar documents score a 35 on the

same scale could show that far fewer people are likely to be able to

read that particular document than a typical document in its field.

As this discussion illustrates, there are good reasons to employ

a comparative methodology when assessing the readability of apex

court decisions if one assumes or hypothesizes that readability

results will not be identical across all apex courts. To start, some

frame of reference is generally needed (or is at least useful) in order

to understand the practical significance of a given set of readability

measurements for any individual apex court. Should a particular

court invest its limited resources in efforts to produce more readable

decisions? That question can be answered—at least in part—with

information about how readable that court’s decisions are in

64

See KINCAID ET AL., supra note 25, at 19; SENTER & SMITH, supra note 24,

at 7–12.

65

See McLaughlin, supra note 60, at 645 (“Comparisons show that SMOG

Grades are generally two grades higher than the corrected Dale-Chall levels.”).

66

See Flesch, supra note 18, at 225; Crossley, Skalicky & Dascalu, supra note

14, at 552–54; MCNAMARA ET AL., supra note 33, at 60–77.

286 N.C. J.L. & TECH. [VOL. 23: 2

comparison with the decisions of other similar courts. To

demonstrate this point, an investment may not be sensible if a court

is already producing the most readable decisions, but an investment

may be well-advised if a court is clearly lagging behind other

comparable courts.

However, a comparative approach facilitates more than just a

contextualized understanding of raw readability numbers; this

approach also opens up the possibility of understanding the factors

that explain differences in readability scores. Where different

common law jurisdictions all have apex courts that perform

essentially the same legal functions (i.e., disposing finally of

appeals, developing the law, and standardizing how the law is to be

applied)

67

but operate within somewhat different social, political,

legal, and institutional environments, there is reason to ask whether

any (and if so, which) environmental factors are capable of

explaining readability variances across the jurisdictions.

Finally, if such environmental factors are found to be driving

readability scores, then a comparative methodology may reveal a

type of best solution, or a path forward, for those interested in

improving readability scores within a given jurisdiction. For

instance, if a study of multiple jurisdictions—each possessing

different levels of factor X—shows that factor X correlates strongly

with higher readability scores, then a poorly-performing jurisdiction

should explore law reform interventions that foster growth of factor

X. While factor X may not actually cause changes in readability

scores (since correlation merely represents the existence of a

dependence or a relationship between two factors, but not

necessarily a causal relationship), exploring strongly correlated

factors as potential sources of positive change at the beginning is

more efficient than deciding on law reform interventions without

regard for the relevant data (essentially, by guessing).

The present study leverages the benefits of using a comparative

methodology to achieve the study’s goals of reporting the

readability levels of apex court decisions released in 2020 from five

English-speaking jurisdictions. Specifically, the study looks more

closely at jurisdiction-specific factors to ascertain whether any of

67

PAUL DALY, APEX COURTS AND THE COMMON LAW 4–10 (Paul Daly ed., 2019).

DEC. 2021] Quantitative Readability 287

them—alone or in combination—can explain readability variances

across the jurisdictions.

III. STUDY DESIGN AND METHOD

Because the present study is one of the first of its kind, and

because the study employs natural language processing and

quantitative linguistics tools not commonly seen in legal

scholarship, the following subparts offer detailed descriptions of the

design and methods of the study, as well as some of its limitations.

A. Study Design

This subpart describes the design choices that were made in

creating the current study and the rationale for those choices. Given

the minimal amount of research that has been undertaken about

readability levels of court decisions from around the world, a variety

of approaches could be used to comparatively measure the

readability levels of decisions from courts in different countries.

However, as this section illustrates, the design choices that underpin

the present study were made in order to facilitate specific, targeted

comparisons between jurisdictions that appear to offer a sound basis

for studying readability variances between national apex courts.

1. Selecting the Level of Court to Study

Understanding the readability levels of common law court

decisions is useful primarily because these decisions declare the law

that governs the population, and because the law, as stated by the

courts, can be of interest to broader groups of stakeholders. Apex

courts tend to declare the law in the most geographically and

hierarchically definitive manner (i.e., throughout a jurisdiction’s

entire territory, and for the benefit of all lower courts within the

jurisdiction), so their decisions are likely significant to a wider range

and larger number of potential domestic readers than the decisions

of lower courts. Additionally, courts and scholars from outside the

jurisdiction tend to cite foreign apex court decisions more than trial

or appellate court decisions, making these decisions more globally

288 N.C. J.L. & TECH. [VOL. 23: 2

significant than other court decisions.

68

For these reasons, the

present study focuses solely on the readability of apex court

decisions.

2. Selecting Jurisdictions for the Study

To begin, this study is concerned with the readability of judicial

decisions as sources of law. Consequently, each jurisdiction selected

for the study needed to form part of the common law “family” that

recognizes the precedential value of judicial decisions and their

status as sources of law—even if the selected jurisdiction also drew

upon other legal traditions.

69

Along related lines, most readability

and quantitative linguistic measures are language-specific, so

selecting apex courts that all produce decisions in the same language

was necessary for this study in order for these decisions to be

compared on a common basis.

This study also sought to compare courts that perform similar

functions under similar procedural circumstances, so only apex

courts that sit at the pinnacle of, at a minimum, a three-tiered court

system (consisting of at least one level each of a trial and an

intermediate appellate court below the apex court) were included in

the study.

70

Specifically, jurisdictions with somewhat equivalent

caseloads were compared

71

to ensure that any statistical analysis of

the global pool of cases within the study would not be

disproportionately affected by decisions from a single jurisdiction.

Additionally, jurisdictions from across a broad geographic spectrum

were included: North America, Europe, Africa, and Oceania. In

68

See, e.g., TANIA GROPPI & MARIE-CLAIRE PONTHOREAU, THE USE OF

FOREIGN PRECEDENTS BY CONSTITUTIONAL JUDGES 418–20 (Tania Groppi &

Marie-Claire Ponthoreau eds., 2013) (noting how SCOTUS, SCC, ZACC, and

German Constitutional Court decisions have been observed to be the most

frequently cited foreign courts within the domestic jurisprudence of other

countries).

69

For instance, Canada’s legal system, when viewed as a whole, incorporates

elements of common, civil, and Indigenous law. South Africa’s legal system

similarly incorporates elements of common, civil, and customary law.

70

This criterion excludes jurisdictions like Singapore and Seychelles, which

both use courts of appeal as their apex courts.

71

The selected jurisdictions within the present study have between thirty and

seventy cases per apex court per year. India, in contrast, had 696 cases, and was

excluded on that basis.

DEC. 2021] Quantitative Readability 289

choosing jurisdictions from within these continents, selections were

driven in part by ease of access to the raw data (e.g., the judicial

decisions) and ease of effort in manipulating the raw data as required

for processing.

72

Finally, the selected jurisdictions needed to have

some meaningful variance across jurisdiction- and institution-

specific factors, in order to permit a comparative assessment of

whether these factors explain any readability variances across the

jurisdictions.

Applying these selection criteria to the list of potential

jurisdictions, the present study was ultimately designed to include

Australia, Canada, South Africa, the United Kingdom, and the

United States.

3. Identifying Relevant Linguistic and Readability Measures

One of the most obvious dimensions of a decision’s readability

is the length of the decision: longer texts take more total time and

effort to read than shorter texts. Thus, the present study includes

measures of decision length, in words, by apex court. Recently,

however, applied linguists have realized that several other factors

influence understanding, processing effort, and overall readability

of texts. For instance, linguistic studies have shown that readability

is affected by the extent to which words are imageable or concrete;

73

the present study therefore includes measures of average

concreteness for content words

74

within decisions.

72

Thus, as between Australia and New Zealand, and as between the United

Kingdom and Ireland, Australia and the United Kingdom were selected because

their decisions can be easily downloaded and manually converted to plain text

files (for processing by readability software) at a rate of about three to five minutes

per decision. In contrast, New Zealand’s and Ireland’s cases are only available in

PDF format. When converting these PDFs to plain text files, it would have been

necessary to manually remove each line break at the end of a line of text—a

process that would take approximately twenty to thirty minutes extra per file.

73

See Max Coltheart, The MRC Psycholinguistic Database, 33 Q. J.

EXPERIMENTAL PSYCH. 497, 497 (1981).

74

Content words (or lexical words) are words that contribute more information

to a text and make up the overwhelming majority of words in the English

language. Content words can be contrasted with function words (or grammatical

words) like pronouns, prepositions, and conjunctions that do not add meaning

inasmuch as they provide grammatical and relational structures for content words.

290 N.C. J.L. & TECH. [VOL. 23: 2

Linguists also recognize that readability and mental processing

times are affected by “the degree of cognitive entrenchment of

particular words / grammatical patterns” that are used within a text.

75

One quantitative technique for measuring such entrenchment

involves comparing a sample text (a judicial decision, for example)

to a reference corpus (a large body of representative texts) to see

how often words used within the sample appear within the reference

corpus—a raw frequency measure.

76

The present study reports one

such linguistic measure that influences readability: the average

frequency for function words, using the Corpus of Contemporary

American English (“COCA”)

77

Academic corpus as the reference

corpus.

78

Applied linguists have also recognized that concepts of

frequency can be applied, not only to individual words, but also to

multi-word phrases

79

—where more common phrases are processed

by audiences more easily than less common phrases.

80

Consequently, this study includes a frequency measure of the

See RONALD CARTER, VOCABULARY: APPLIED LINGUISTIC PERSPECTIVES 8 (2d

ed. 1998).

75

Stefan Th. Gries, Dispersions and Adjusted Frequencies in Corpora, 13

INT’L J. CORPUS LINGUISTICS 403, 403 (2008).

76

Xiaobin Chen & Detmar Meurers, Word Frequency and Readability:

Predicting the Text-Level Readability with a Lexical-Level Attribute, 41 J. RES. IN

READING 486, 488–91 (2018).

77

Mark Davies, The Corpus of Contemporary American English as the First

Reliable Monitor Corpus of English, 25 LITERARY & LINGUISTIC COMPUTING

447, 453–54 (2010).

78

One would expect frequent use of academic language in a judicial decision

to render the decision less readable.

79

Multi-word phrases are also often called N-grams (where “N” represents the

size of the phrase). Two- and three-word phrases are also often called bigrams and

trigrams, respectively. To offer a concrete example, consider the following

sentence: “I am hungry today.” The sentence contains three distinct bigrams (I

am; am hungry; hungry today) and two distinct trigrams (I am hungry; am hungry

today).

80

See Inbal Arnon & Neal Snider, More Than Words: Frequency Effects for

Multi-Word Phrases, 62 J. MEMORY & LANGUAGE 67, 76 (2010). The theory that

common phrases are more easily processed makes intuitive sense: readers of this

footnote will likely process the phrase “stop at the red light” much faster than they

would process the phrase “go at the red light.” The latter phrase jars on the reader

because of its unfamiliarity and may require re-reading for confirmation of the

contents of the phrase.

DEC. 2021] Quantitative Readability 291

proportion of bigrams in judicial decisions that appear in the top

20,000 most common bigrams from within the COCA Fiction

corpus.

81

Each of the above linguistic measures offer unidimensional

assessments of a factor that likely influences text readability.

However, readability is understood to be affected simultaneously by

many different factors. Therefore, this study also—and perhaps

most importantly—includes comprehensive (or multidimensional)

readability scores. Specifically, this study reports on Flesch-Kincaid

scores,

82

SMOG scores,

83

and Crowd-sourced Reading

Comprehension-Modified (“CAREC-M”)

84

scores. Flesch-Kincaid

scores are included because this measure of readability is arguably

the most widely known across all disciplines, perhaps because of its

inclusion within common word processing software packages.

85

SMOG scores are included because this measure has already been

used in legal scholarship as part of a large-scale study looking at

SCOTUS decisions.

86

Finally, CAREC-M scores are included

because this new measure leverages NLP techniques in order to

derive a comprehensive readability formula from observations of

several hundred text-related features (relating to word, phrase, and

sentence properties; sentiment; cohesion; and, numerous other

linguistic and grammatical properties of texts).

87

In this sense, the

CAREC-M score is perhaps the most sophisticated general

readability measure currently available: the score is “based on

81

Davies, supra note 77, at 453–54. Where the COCA Fiction corpus is a

general and non-specialized corpus, one would expect that judicial decisions using

a high proportion of the top 20,000 bigrams from that corpus to be more readable

than decisions using a low proportion of such bigrams. See id.

82

KINCAID ET AL., supra note 25, at 14.

83

McLaughlin, supra note 60, at 639.

84

Crossley, Skalicky & Dascalu, supra note 14, at 553; Joon Suh Choi & Scott

A. Crossley, Assessing Readability Formulas: A Comparison of Readability

Formula Performance on the Classification of Simplified Texts, EASYCHAIR (July

13, 2020), https://easychair.org/publications/preprint_download/Glkz [https://

perma.cc/3T87-X25Z].

85

See Norman Otto Stockmeyer, Using Microsoft Word’s Readability

Program, 88 MICH. BAR J. 46, 46 (2009).

86

See Whalen, supra note 59, at 202–10.

87

See Crossley, Skalicky & Dascalu, supra note 14, at 549–51.

292 N.C. J.L. & TECH. [VOL. 23: 2

linguistic features that better represent theoretical and behavioural

accounts of the reading process [and] significantly outperformed

classic readability formulas” in a validating study.

88

The above measures, when calculated for each of the large

number of full-text judicial decisions within the current study,

provide a robust and informed picture of the readability of those

judicial decisions. Although each measure offers distinct insights

into decision readability levels, CAREC-M scores were chosen

within this study as the most comprehensive measure of readability.

Consequently, all comparative and statistical analyses examining

jurisdiction- and court-specific variables as potential sources of

explanation for readability variances within the present study were

performed using CAREC-M scores as the relevant readability

measure.

4. Identifying Variables for Comparison

Initial research into apex courts from the selected jurisdictions,

as well as research of the environments within which these courts

operate, revealed many differences that could provide a useful basis

for comparison. In particular, the overall education levels of the

populations in the different jurisdictions varied substantially. One

might expect that judges would write decisions with some sense of

the population’s education levels in mind, such that readability

levels would be higher in jurisdictions with lower general education

levels. Accordingly, this variable was included in the study, with a

single measurement of adult secondary school completion rate for

each jurisdiction.

On a related point, initial findings showed that judges within

different jurisdictions possessed widely divergent levels of post-

secondary education, and that former law professors were appointed

to the apex courts more often in some jurisdictions than others. One

could logically assume that courts comprised of more-educated

judges would tend to produce less-readable decisions (since these

judges presumably have access to broader academic vocabularies

and have more experience with complex writing styles). Thus, these

variables were also included within the study—with discrete

88

Id. at 557.

DEC. 2021] Quantitative Readability 293

measures of (educational) degrees per judge and former law

professors per judge for each case within the study. Additionally, in

terms of demographic characteristics of judges, some courts had a

significantly greater proportion of female judges than other courts.

Some research has suggested that women write more readably than

men,

89

so one might expect that courts with a greater relative

representation of women would produce more readable decisions;

this variable—women per judge—was included in the study on that

basis.

On a more institutional-procedural level, different apex courts

hear cases with different panel sizes: in Australia some cases were

decided by a single judge, while in South Africa, one case was

decided by a panel of eleven judges (and many were decided by

panels of ten judges).

90

One might expect that decisions would be

more readable where panel sizes are larger, on the assumption that

more effort would need to be expended to communicate clearly to

fellow judges on the larger panel for the purpose of building a

majority or consensus view. For this reason, panel size was included

as a variable within the study, with unique measurements for each

decision.

In addition, judicial law clerks were used to differing extents

within the selected jurisdictions, with clerks heavily involved in

drafting decisions in some jurisdictions and not involved at all in

other jurisdictions. One might expect that a more collaborative

decision-drafting jurisdiction that involves clerks and judges

(instead of only judges) would produce more readable decisions. On

that basis, clerk involvement was included as a variable, with a single

subjective and relative ranking included for each jurisdiction.

Finally, the judicial appointment processes, and overall role of

the apex courts, are politicized to different extents in each

jurisdiction. One might expect judicial decisions to be more readable

in places with higher levels of politicization since a court’s

legitimacy in such places likely depends more heavily on approval

of the broad population. This factor might accordingly drive judges

89

See Erin Hengel, Publishing While Female, in WOMEN IN ECONOMICS 80,

80–82 (Shelley Lundberg ed., 2020).

90

See infra Table 6.

294 N.C. J.L. & TECH. [VOL. 23: 2

to write more accessible decisions aimed at the general population

in such jurisdictions. The variable of court politicization was

therefore included within the study, again with a single subjective

and relative ranking included for each jurisdiction.

Although the apex courts within the present study all fill similar

roles and perform similar functions, the differences in the above-

listed factors across the jurisdictions provide ample basis for

meaningful comparison. By studying readability variances

alongside differences in each of the above variables, the study can

assess the extent to which any of the variables alone, or in

combination, can explain the readability variances of the apex

courts.

B. Method

This subpart provides a detailed explanation of the way in which

the present study was conducted. Ideally, the results that the study

has produced should be replicable by anyone who follows the

method described below.

1. Case Selection and Acquisition

The data for this study was collected by first identifying all

decided cases for each apex court in 2020 from the respective courts’

websites.

91

Australian cases were downloaded in rich-text format

(“RTF”) and then batch converted to plain text (“TXT”) format

using the Mac OS 11 Text Utility.

92

For each Canadian, South

91

Judgments, Ordered By Date, Browsing By Year (2020), AUSTL. HIGH CT.,

http://eresources.hcourt.gov.au/browse?col=0&facets=dateDecided&srch-term=2020

[https://perma.cc/SK3H-ALLB]; Supreme Court Judgments, SUP. CT. OF CAN.,

https://scc-csc.lexum.com/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/2020/nav_date.do [https://perma.cc/Z3Q

E-4VHQ]; 2020 South Africa: Constitutional Court Decisions, S. AFR. LEGAL INFO.

INST., http://www.saflii.org/za/cases/ZACC/2020/ [https://perma.cc/H5WK-SETY]

(last visited Sep. 22, 2021); Decided Cases, THE SUP. CT.,

https://www.supremecourt.uk/decided-cases/2020.html [https://perma.cc/5FBK-JGV5];

Opinions of the Court – 2020, SUP. CT. OF U.S., https://www.supremecourt.gov/

opinions/slipopinion/20 [https://perma.cc/594J-BYAY].

92

See How to Batch Convert DOCX Files to TXT Format with Textutil in Mac

OS X, OSXDAILY, (February 20, 2014), https://osxdaily.com/2014/02/20/batch-

convert-docx-to-txt-mac/ [https://perma.cc/PJD4-3YBW], for a description of

how to perform this conversion.

DEC. 2021] Quantitative Readability 295

African, and United Kingdom decision, the full text of the decision

was “copied” from the HTML webpage containing the decision, and

“pasted” into a new TXT file using the Mac OS 11 Text Editor

application. For the United States, each decision’s citation was used

to search the decision in the Google Scholar database, where HTML

versions of the decisions were available. The text of each decision

from its HTML webpage was then “copied” and “pasted” into a text

file (following the same process as for Canadian decisions). In this

manner, individual TXT files were created and stored for all

decisions from 2020 from each of the selected apex courts.

2. Data Pre-Processing

Each TXT file was opened individually. Once opened, all front-

end matter preceding the text of the decision, other than core

identifying information (e.g., style of cause, date, judges present,

etc.), was manually deleted, such as the names of counsel,

headnotes, case summaries, cases cited, authors cited, and other

similar front-end information. Similarly, all back-end information

following final statements of disposition of the cases or other

conclusions were also deleted manually. The back-end information

that was deleted included footnotes, annexes or appendices, copies

of orders issued by the courts, and other similar information. The

extent of information that preceded or followed the actual decision

varied greatly from one decision to another (e.g., some SCOTUS

cases had extensive footnotes, while others had no footnotes), and

from one jurisdiction to another (e.g., most SCC cases had lengthy

headnotes and case summaries, but most UKSC cases had no such

information). After manually deleting the front- and back-end text

from each file, the decisions were then saved and ready for

processing by NLP software with only a common and

approximately equal amount of extra (case-identifying) text

included in each file.

296 N.C. J.L. & TECH. [VOL. 23: 2

3. Processing Tools, NLP Computations, and Exclusions

All decisions were processed through the Simple Natural

Language Processing (“SiNLP”) software application,

93

which is

freely available for both Mac and Windows operating systems,

94

to

measure decision length (in words) for each decision. At this stage,

any decisions that contained less than 260 words (including any

remaining front- and back-end text) were excluded from the study

(N = 16).

95

These decisions were excluded because both the SMOG

and CAREC-M comprehensive readability formulae are intended for

use with larger text samples.

96

The remaining decisions were then

processed through the Tool for the Automatic Analysis of Lexical

Sophistication (“TAALES”),

97

which is also freely available for

93

Scott Crossley et al., Analyzing Discourse Processing Using a Simple

Natural Language Processing Tool (SiNLP), 51 DISCOURSE PROCESSES 511,

520–24 (2014). This application provides seven different simple linguistic

measures, such as number of words, sentences and paragraphs, and average word

and sentence lengths, for all text files processed by the software. See id.

94

See NLP Tools for the Social Sciences – SiNLP: The Simple Natural

Language Processing Tool, NLP TOOLS FOR THE SOC. SCIS. [hereinafter NLP

Tools for the Social Sciences], https://www.linguisticanalysistools.org/sinlp.html

[https://perma.cc/5MRG-F74N] (last visited Oct. 4, 2021).

95

From Australia, N=1; from Canada, N=13; from the United States, N=2; and

from both South Africa and the United Kingdom, N=0. The excluded decisions

tended to be ones wherein a lower court’s decision was upheld or overturned by

the apex court in a very short opinion that expressed full agreement with the lower

court (or a judge of that lower court) without further explanation.

96

SMOG calculations are based on a minimum of thirty sentences of text

(which would equate to approximately 600–900 words of text from a typical

judicial decision). See McLaughlin, supra note 55. CAREC-M calculations are

intended for text samples of more than 200 words. See J.S. Choi & S.A. Crossley,

NLP Tools for the Social Sciences - ARTE: Automatic Readability Tool for

English, NLP TOOLS FOR THE SOC. SCIS., https://www.linguistic

analysistools.org/arte.html [https://perma.cc/E5G9-LT9L] (last visited Oct. 4,

2021). Given that front- and back-end matter comprised approximately 60 words

in many decisions within the present study, a minimum threshold of 260 words

was selected as an inclusion criterion.

97

Kristopher Kyle, Scott Crossley & Cynthia Berger, The Tool for the

Automatic Analysis of Lexical Sophistication (TAALES): Version 2.0, 50 BEHAV.

RES. METHODS 1030, 1032–37 (2018). This application provides over 250

different linguistic measures, including range and frequency for words and N-

gram from multiple corpora, psycholinguistic properties of words, and many other

related measures, for all text files processed by the software. Id.

DEC. 2021] Quantitative Readability 297

both Mac and Windows operating systems,

98

in order to measure the

following text dimensions: average concreteness for content words;

average frequency for function words (COCA Academic); and,

average proportion of bigrams in top 20K (COCA Fiction). Finally,

all decisions were processed through the Automatic Readability

Tool for English (“ARTE”) software application,

99

which is freely

available for both Mac and Windows operating systems,

100

to

compute Flesch-Kincaid, SMOG, and CAREC-M comprehensive

readability scores.

4. Data Collection and Coding of Variables

Data for each jurisdiction for adult secondary school completion

rate was taken from an Organisation for Economic Co-operation

and Development (“OECD”) database

101

using figures from 2018

(the most recent year with reported figures for all five of the

jurisdictions forming part of the present study). This data point is

reported in terms of the percentage of the adult population in the

jurisdiction with less than a completed upper secondary school level

of education.

102

Data for panel size was compiled by identifying, via a manual

count for each decision, the number of judges who participated in

the decision. Similarly, data for degrees per judge, former law

professors per judge, and women per judge was collected first by

identifying which judges participated in the decision. This

information was used, together with publicly available biographical

information about each judge relating to their educational and

professional experiences (drawn primarily from official court

websites), in order to produce the relevant measures. For the

variable degrees per judge, each post-secondary degree possessed

by a judge was counted (regardless of whether the degree was at the

98

See NLP Tools for the Social Sciences, supra note 94.

99

Choi & Crossley, supra note 84. This application provides comprehensive

readability scores for all text files processed by the software, based on nine

different formulae (e.g., Dale-Chall, SMOG, ARI).

100

Id.

101

Adult Education Level, ORG. ECON. COOPERATION & DEV,

https://data.oecd.org/eduatt/adult-education-level.htm [https://perma.cc/S8J8-FY6Y]

(last visited Apr. 2, 2021).

102

Id.

298 N.C. J.L. & TECH. [VOL. 23: 2

undergraduate, masters, or doctoral level), but diplomas and

certificates were not counted. The variable was calculated by

dividing the total number of degrees possessed by all judges on a

panel by the number of judges on the panel. For the variable former

law professors per judge, any judge who had worked full-time as a

law professor for at least two years was counted, but judges who had

taught on a part-time basis as sessional or adjunct faculty were not

counted. The variable was calculated by dividing the number of

judges on a panel who had formerly been law professors by the total

number of judges on the panel. For the variable women per judge,

any judge who was biographically described using “she/her”

pronouns was counted, and the variable was calculated by dividing

the total number of women on a panel by the total number of judges

on the panel.

Quantitative data for clerk involvement and court politicization

were not yet available for use within the present study. This study

therefore relied on secondary sources discussing each of these

variables to derive subjective relative scores for each jurisdiction.

The results and the sources relied upon to derive the results are

identified in detail below.

103

5. Descriptive and Analytical Statistical Techniques

A number of approaches were used in order to determine how

readability variances across jurisdictions may be explained by

jurisdiction- or court-specific variables. With respect to variables for

which only national data is available and for which there are not

discrete measurements specific to each case being analyzed (e.g.,

adult secondary school completion rate, clerk involvement, and

court politicization), comparative analysis was undertaken by

comparing mean readability scores in each jurisdiction with national

levels of the relevant variable—in a largely descriptive manner. In

the case of variables for which there are discrete measurements for

each case (e.g., panel size, degrees per judge, former law professors

per judge, and women per judge), statistical analysis was performed

using SPSS software to compute Pearson correlations between each

variable and CAREC-M readability scores. Additionally, SPSS

103

See infra Part IV.B.2 (“Clerk Involvement”) and Part IV.B.3 (“Court

Politicization”).

DEC. 2021] Quantitative Readability 299

software was used to run a multiple regression analysis as a means

of modeling the extent to which a combination of variables might

explain overall readability variances across jurisdictions.

C. Limitations of the Study