Evaluation of

DHS' Information

Security Program for

Fiscal Year 2022

April 17,

2023

OIG-23-21

7

JOSEPH V

CUFFARI

www.oig.dhs.gov

DHS OIG HIGHLIGHTS

Evaluation of DHS’ Information Security

Program for Fiscal Year 2022

April 17, 2023

Why We Did

This Evaluation

We reviewed the Department of

Homeland Security’s information

security program for compliance

with Federal Information Security

Modernization Act of 2014

(FISMA) requirements. We

conducted our evaluation

according to fiscal year 2022

reporting instructions. Our

objective was to determine

whether DHS’ information

security program and practices

were adequate and effective to

protect the information and

information systems that

support DHS’ operations and

assets for FY 2022.

What We

Recommend

We made one recommendation

to DHS to address the

deficiencies we identified.

For Further Information:

Contact our Office of Public Affairs at

(202) 981-6000, or email us at

DHS-OIG.OfficePublicAffairs@oig.dhs.gov

What We Found

DHS’ information security program for FY 2022

was rated “effective,” according to this year’s

reporting instructions. We based this rating on

our evaluation of DHS’ compliance with the FISMA

requirements on unclassified and National

Security Systems, for which DHS improved its

maturity level in three functions compared to FY

2021. DHS received “Level 4 – Managed and

Measurable” in the Identify, Protect, Respond, and

Recover functions, and a “Level 3 – Consistently

Implemented” in the Detect function.

Based on our evaluation and testing, we identified

the following six deficiencies:

1. Systems were operating without an Authority to

Operate and without Contingency Plan Testing.

2. Plans of Action and Milestones used to mitigate

known information security weaknesses were

past due or not updated.

3. Security configuration settings were not

implemented for all systems tested.

4. Some components had identity and access

weaknesses.

5. An unsupported version of a Windows operating

system was running on a component

workstation.

6. Some components did not promptly apply

security patches to mitigate critical and high-

risk security vulnerabilities on selected systems

tested.

DHS Response

DHS concurred with the recommendation. We

included a copy of DHS’ comments in Appendix B.

www.oig.dhs.gov OIG-23-21

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

Table of Contents

Background ………………………………………………………………….…………….….1

Results of Evaluation……………………………………………………….…………….…5

DHS Improved the Effectiveness of Its Information Security

Program…………………………………………………………………………………………5

1. Identify………………………….……………………………………………………6

2. Protect………………………………………………………………………………11

3. Detect…………….………………………………………………………….…..…15

4. Respond…………………………………………………………………………....16

5. Recover………………………………………………………………………….….17

Recommendations……………………………………………………………………….....19

Management Comments and OIG Analysis .....…………………………………...…19

Appendixes

Appendix A: Objective, Scope, and Methodology ................................... 23

Appendix B: Management Comments to the Draft Report..................... 25

Appendix C: Major Contributors to This Report.................................... 29

Appendix D: Report Distribution………….………………………………….....30

Abbreviations

ATO Authority to Operate

CIO Chief Information Officer

CISA Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency

CISO Chief Information Security Officer

FISMA Federal Information Security Modernization Act of 2014

HQ Headquarters

HVA High Value Asset

ICE U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement

IG Inspector General

IT Information Technology

NIST National Institute of Standards and Technology

NSS National Security System

OCIO Office of the Chief Information Officer

www.oig.dhs.gov OIG-23-21

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

Background

Recognizing the importance of information security to the economic and

national security interests of the United States, Congress enacted the Federal

Information Security Modernization Act of 2014 (FISMA).

1

Information security

means protecting information and information systems from unauthorized

access, use, disclosure, disruption, modification, or destruction.

2

FISMA

provides a framework for ensuring effective security controls are in place to

protect the information resources that support Federal operations and assets.

3

FISMA focuses on program management, implementation, and evaluation of the

security of unclassified and National Security Systems (NSS).

4

Specifically,

FISMA requires Federal agencies to develop, document, and implement agency-

wide information security programs.

5

Each program should protect the data

and information systems supporting the operations and assets of the agency,

including those provided or managed by another agency, contractor, or source.

6

According to FISMA, agencies are responsible for conducting annual evaluations

of information programs and systems under their purview. Each agency’s Chief

Information Officer (CIO), in coordination with senior agency officials, is

required to report annually to the agency head on the effectiveness of the

agency’s information security program, including progress on remedial actions.

7

The Department of Homeland Security has various missions, such as

preventing terrorism, ensuring disaster resilience, managing U.S. borders,

administering immigration laws, and securing cyberspace. To accomplish its

broad array of complex missions, DHS employs approximately 240,000

personnel, all of whom rely on information technology (IT) to perform their

duties. It is critical that DHS provide a high level of cybersecurity

8

for the

information and information systems supporting day-to-day operations.

The DHS Chief Information Security Officer (CISO) bears primary responsibility

for protecting information and ensuring compliance with FISMA. The DHS

CISO heads the Information Security Office and manages the Department’s

information security program for its unclassified systems, its national security

1

44 United States Code § 3551 et.seq.

2

Id. at § 3552(b)(3).

3

Id. at § 3551(1).

4

DHS defines NSS as systems that collect, generate, process, store, display, transmit, or

receive Unclassified, Confidential, Secret, and Top-Secret information.

5

Id. at § 3554(b).

6

Id. at § 3554(a)(1), (2) and 3554(b).

7

Id. at § 3554(a)(5).

8

Cybersecurity is the process of protecting information by preventing, detecting, and

responding to attacks.

www.oig.dhs.gov 1 OIG-23-21

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

systems classified as “Secret” and “Top Secret,” and systems operated by

contractors on behalf of DHS. As part of the Department’s continuous

monitoring strategy, DHS CISO maintains awareness of the Department’s

information security program through: (1) Continuous Diagnostics and

Mitigation, (2) Ongoing Authorization Program, and the (3) Network Operations

Security Center.

9

Foremost to all DHS components is adhering to the IT security requirements

set forth in the Department’s security authorization process,

10

which involves

comprehensive testing and evaluation of security features of all information

systems before becoming operational

11

within the Department. This evaluation

process results in an Authority to Operate (ATO) decision, whereby a senior

official authorizes the operation of an information system based on an agreed-

upon set of security controls. Per DHS guidelines,

12

each component CISO is

required to assess the effectiveness of controls implemented before authorizing

the systems to operate, and periodically thereafter. According to applicable

DHS,

13

Office of Management and Budget (OMB),

14

and National Institute of

Standards and Technology (NIST)

15

policies, all systems must undergo the

authorization process before they become operational. The DHS CISO relies on

two enterprise management systems to keep track of security authorization

status and administer the information security program. Enterprise

management systems also provide a means to monitor plans of action and

milestones for remediating information security weaknesses related to

unclassified and Secret-level systems.

FISMA Reporting Instructions

FISMA requires each agency Inspector General (IG) to perform an annual

independent evaluation to determine the effectiveness of the agency’s

information security program and practices. The FY 2022 Core Inspector

General Metrics Implementation Analysis and Guidelines

16

(Fiscal Year 2022

9

DHS Information Security Continuous Monitoring Strategy, Version 5.0, May 20, 2022.

10

NIST defines a security authorization as a management decision by a senior organizational

official authorizing operation of an information system and explicitly accepting the risk to

agency operations and assets, individuals, other organizations, and the Nation based on

implementation of an agreed-upon set of security controls.

11

According to DHS policy, an information system must be granted an Authority to Operate.

12

DHS System Security Authorization Process Guide, Version 14.1, April 4, 2019.

13

DHS System Security Authorization Process Guide, Version 14.1, April 4, 2019.

14

OMB Circular A-130, Managing Information as a Strategic Resource, July 2016.

15

NIST Special Publication (SP) 800-53, Revision 5, Security and Privacy Controls for

Information Systems and Organizations, September 2020.

16

The FY 2022 Core Inspector General Metrics Implementation Analysis and Guidelines was

based on coordinated discussions between representatives from OMB, the Council of the

Inspectors General on Integrity and Efficiency, Federal Civilian Executive Branch CISOs and

their staff, and the Intelligence Community.

www.oig.dhs.gov 2 OIG-23-21

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

FISMA Reporting Metrics) provide reporting requirements for addressing key

areas identified during independent evaluations of agency information security

programs. IGs are required to assess the effectiveness of information security

programs on a maturity model spectrum, in which the foundational levels

ensure that agencies develop sound policies and procedures, while the

advanced levels capture the extent to which agencies institutionalize policies

and procedures. Within the maturity model context, agencies should perform

risk assessments to identify the optimal maturity levels that achieve cost-

effective security, based on mission, risks faced, risk appetites, and risk

tolerance. NIST provides agencies with a common structure to identify and

manage cybersecurity risks across the enterprise, in alignment with five

functions from its Cybersecurity Framework.

17

Table 1. NIST Cybersecurity Functions and FY 2022 FISMA Domains

FISMA Domains

Risk Management

Supply Chain Risk Management

Configuration Management

Identity and Access Management

Data Protection and Privacy

Security Training

Detect

Develop and implement the appropriate activities to

identify the occurrence of a cybersecurity event.

Information Security Continuous

Monitoring

Respond

Develop and implement the appropriate activities to take

action regarding a detected cybersecurity event.

Incident Response

Cybersecurity Functions

Identify

Develop the organizational understanding to manage

cybersecurity risk to systems, assets, data, and

capabilities.

Protect

Develop and implement the appropriate safeguards to

ensure delivery of critical services.

Develop and implement the appropriate activities to

maintain plans for resilience and to restore any

Recover Contingency Planning

capabilities or services that were impaired due to a

cybersecurity event.

Source: NIST Cybersecurity Framework and FY 2022 FISMA Reporting Metrics

According to the FY 2022 FISMA Reporting Metrics, each Office of Inspector

General evaluates its agency’s information security program using selected

metrics from the FY 2021 IG metrics

18

for their applicability to critical efforts

emanating from Executive Order 14028

19

and OMB M-22-05

20

and cited in the

reporting instructions for the five cybersecurity functions listed in Table 1. The

questions are derived from the maturity models outlined within the NIST

Cybersecurity Framework. Based on its evaluation, OIG assigns each

17

Framework for Improving Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity, Version 1.1, April 16, 2018.

18

FY 2021 Inspector General FISMA Reporting Metrics, Version 1.1, May 12, 2021.

19

Executive Order 14028, Improving the Nation's Cybersecurity, issued May 12, 2021.

20

OMB Memorandum 22-05, Memorandum for the Heads of Executive Departments and

Agencies, December 6, 2021.

www.oig.dhs.gov 3 OIG-23-21

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

cybersecurity function a maturity level of 1 through 5, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2. OIG Evaluation of Maturity Levels

Maturity Level Maturity Level Description

Level 1 – Ad-hoc

Policies, procedures, and strategies are not formalized; activities are performed

in an ad-hoc, reactive manner.

Level 2 – Defined

Policies, procedures, and strategies are formalized and documented, but not

consistently implemented.

Level 3 – Consistently

Implemented

Policies, procedures, and strategies are consistently implemented, but

quantitative and qualitative effectiveness measures are lacking.

Level 4 – Managed and

Measurable

Quantitative and qualitative measures on the effectiveness of policies,

procedures, and strategies are collected across the organization and used to

assess them and make necessary changes.

Level 5 – Optimized

Policies, procedures, and strategies are fully institutionalized, repeatable, self-

generating, consistently implemented, and regularly updated based on changing

threats and technology landscape and business/mission needs.

Source: FY 2021 FISMA Reporting Metrics

21

Per the FY 2022 FISMA Reporting Metrics, when an information security

program is rated at “Level 4, Managed and Measurable,” the program is

operating at an effective level of security.

Scope of Our FISMA Evaluation

This report summarizes the results of our evaluation of the Department’s

information security program based on the FY 2022 FISMA Reporting Metrics.

We performed our fieldwork at DHS Headquarters (HQ), DHS Office of the

CISO, and at three selected DHS components. To determine whether DHS

components effectively manage and secure their information systems, we

reviewed the Department’s monthly FISMA Scorecards for unclassified systems

and NSS. As part of discretionary audits conducted over the past year, we

conducted technical testing to assess configuration management practices on

eight selected systems at two components (referred to as “Component E” and

“Component J”). Two of the eight systems assessed were designated as High

Value Assets (HVA).

22

We responded to the core questions cited in the FY 2022

FISMA Reporting Metrics based on our evaluation of DHS’ compliance with

applicable FISMA requirements.

21

The FY 2022 maturity levels were based on the FY 2021 FISMA Reporting Metrics.

22

An HVA is information or an information system so critical to the Department that the loss

or corruption of this information or loss of access to the system would have serious impact to

the organization’s ability to perform its mission or conduct business.

www.oig.dhs.gov 4 OIG-23-21

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

To determine the effectiveness of components’ implementation of their

information security programs, our independent contractor performed work at

the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), U.S. Immigration

and Customs Enforcement (ICE), and U.S. Citizenship and Immigration

Services (USCIS). The contractor evaluated each component based on the

maturity model approach outlined in the FY 2022 FISMA Reporting Metrics

and NIST’s Cybersecurity Framework. We have incorporated the contractor’s

work in this report.

Results of Evaluation

DHS’ information security program for FY 2022 was rated as “effective,”

according to this year’s reporting instructions. We based this rating on our

evaluation of DHS’ compliance with the FISMA requirements on unclassified

and National Security Systems, for which DHS improved its maturity level in

three functions as compared to FY 2021. DHS received “Level 4 – Managed and

Measurable” in the Identify, Protect, Respond, and Recover functions, and a

“Level 3 – Consistently Implemented” in the Detect function.

Based on our evaluation and testing, we identified the following six deficiencies:

1. Systems were operating without an ATO or Contingency Plan Testing.

2. Plans of Action and Milestones (POA&M) used to mitigate known

information security weaknesses were past due or not updated.

3. Security configuration settings were not implemented for all systems

tested.

4. Selected components had identity and access weaknesses.

5. An unsupported version of a Windows operating system was running on

a component workstation.

6. Some components did not promptly apply security patches to mitigate

critical and high-risk security vulnerabilities on selected systems tested.

DHS Improved the Effectiveness of Its Information Security

Program

DHS improved its maturity level in three functions as compared with FY 2021,

with a maturity rating of “Managed and Measurable” (Level 4) in four of five

functions. We summarized a comparison of FY 2021 and FY 2022 ratings in

Table 3.

www.oig.dhs.gov 5 OIG-23-21

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

Table 3. DHS’ Maturity Level for Each Cybersecurity Function in

FY 2021 Compared with FY 2022

Cybersecurity

Function

Maturity Level

FY 2021 FY 2022

1. Identify Level 3 – Consistently Implemented Level 4 – Managed and Measurable

2. Protect Level 4 – Managed and Measurable Level 4 – Managed and Measurable

3. Detect Level 3 – Consistently Implemented Level 3 – Consistently Implemented

4. Respond Level 3 – Consistently Implemented Level 4 – Managed and Measurable

5. Recover Level 2 – Defined Level 4 – Managed and Measurable

Source: DHS OIG analysis based on our FY 2021 report

23

and FY 2022 FISMA Reporting

Metrics

The following is a complete discussion of all progress and deficiencies we

identified in each cybersecurity function as part of this evaluation.

1. Identify: The “Identify” function requires developing an organizational

understanding to manage cybersecurity risks to systems, assets, data, and

capabilities.

We determined DHS was operating at “Level 4 – Managed and Measurable” in

this function. DHS can further improve this area by focusing on centralized

risk management practices. For example, DHS did not provide an enterprise-

wide (portfolio) view of cybersecurity risk management activities for all systems

across the Department. Further, DHS did not provide documentation to

support that it had integrated cybersecurity risk management information into

its Enterprise Risk Management process, including DHS’ agency-wide risk

assessment, as discussed in OMB Circular A-123, the U.S. Government

Accountability Office’s Green Book, and NIST Special Publications (SP) 800-37

and 800-39.

We also identified component systems that were operating with expired ATOs.

Without valid ATOs, DHS cannot be assured effective controls are in place to

protect sensitive information stored and processed by these systems. We also

identified deficiencies in security weakness remediation, as several components

did not effectively manage the POA&M process as required by DHS. POA&M is

a tool to correct information security weaknesses found during any review done

by, for, or on behalf of the agency, such as audits or vulnerability assessments.

A POA&M identifies tasks that need to be accomplished and details the

resources required to accomplish elements of the plan, any milestones for

meeting tasks, and scheduled completion dates for milestones.

24

23

Evaluation of DHS’ Information Security Program for Fiscal Year 2021, OIG-22-55, August 1,

2022.

24

OMB Memorandum 02-01, Guidance for Preparing and Submitting Security Plans of Action

and Milestones, October 17, 2001.

www.oig.dhs.gov 6 OIG-23-21

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

Risk Management

Managing risk is a complex, multifaceted activity that requires involvement of

the entire organization. A key component of risk management is the security

authorization package (also referred to as an ATO package) that documents the

results of the security assessment. The ATO process provides the authorizing

official with information needed to make a risk-based decision whether to

authorize operation of the information system.

25

Per DHS guidance,

26

components are required to use enterprise management systems

27

that

incorporate NIST security controls when performing security assessments of

their systems. Based on OMB and NIST guidance,

28

system ATOs are typically

granted for a specific period, in accordance with terms and conditions

established by the authorizing official. DHS allows its components to enroll in

an ongoing authorization program established by NIST.

We determined that 5 of 11 DHS components did not meet the required

authorization target for high-value assets. DHS maintains a target goal of

ensuring ATOs for 100 percent of its 149 high-value systems assets. The ATO

target goal is 95 percent for its 449 other operational systems. In our review of

DHS’ May 2022 FISMA Scorecard for unclassified systems, we found that five

components did not meet the required authorization target of 100 percent for

high-value assets, as shown in Figure 1.

25

A Federal information system is an information system used or operated by an executive

agency, a contractor of an executive agency, or another organization on behalf of an executive

agency.

26

DHS FY22 Information Security Performance Plan, Version 5.0, January 18, 2022.

27

Enterprise management systems enable centralized storage and tracking of all

documentation required for the authorization package of each system.

28

OMB Circular A-130, Managing Information as a Strategic Resource, July 2016; NIST SP

800-37 Revision 2, Risk Management Framework for Information Systems and Organizations: A

System Life Cycle Approach for Security and Privacy, December 2018.

www.oig.dhs.gov 7 OIG-23-21

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

Figure 1. Selected Components’ Performance Meeting

the ATO Goal for High-Value Systems Assets

Source: DHS OIG analysis of DHS’ May 2022 FISMA Scorecard

90%

96%

96%

50%

86%

0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100%

Component J

Component I

Component G

Component F

Component D

In addition, according to DHS’ May 2022 FISMA Scorecard, there were 40 other

systems from 6 of 11 DHS components that did not meet the security

authorization target of 95 percent, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Selected Components’ Performance Meeting

the ATO Goal for Other Systems

85%

86%

86%

82%

84%

81%

78% 79% 80% 81% 82% 83% 84% 85% 86% 87%

Component J

Component H

Component G

Component F

Component D

Component A

Source: DHS OIG analysis of DHS’ May 2022 FISMA Scorecard

To determine the components’ compliance with DHS’ NSS security

authorization target, we examined the Department’s May 2022 NSS FISMA

www.oig.dhs.gov 8 OIG-23-21

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

Cybersecurity Scorecard. We found that all DHS General Support

System/Major Applications met DHS’ NSS ATO target of 90 percent.

Our analysis of May 31, 2022, data from DHS’ unclassified enterprise

management system revealed that DHS and its components have made

progress reducing the number of systems operating without ATOs to 23,

compared to 56 of 600 (62 percent reduction) in FY 2021. Table 4 outlines the

number of unclassified systems operating without ATOs at selected

components from FYs 2020 to 2022.

Table 4. Number of Unclassified Systems Operating without ATOs

at Selected Components

Component FY 2020 FY 2021 FY 2022

Component A 2 6 0

Component B N/A N/A N/A

Component C 0 0 0

Component D 10 12 11

Component E 61 35 1

Component F 1 1 3

Component G 1 1 0

Component H 0 0 2

Component I 0 1 3

Component J N/A N/A 3

Component K 0 0 0

Total 75 56 23

Source: DHS OIG-compiled data from Evaluation of DHS’ Information Security Program for

Fiscal Year 2020, OIG-21-72, September 30, 2021, and analysis of data from DHS’

unclassified enterprise management system as of May 31, 2022

In our FISMA FY 2021 report, OIG-22-55, dated August 1, 2022, we

recommended DHS revise its (1) DHS 4300A Policy, (2) Handbook, and (3)

Ongoing Authorization Methodology to incorporate applicable changes from

NIST SPs, including SP 800-37, Revision 2,

29

and SP 800-53, Revision 5, and

SP 800-137A, to maintain consistency between the documents. In July 2022,

we reported to OMB that DHS had not yet updated this guidance to reflect the

new and revised controls. However, the Department updated its 4300A Policy,

Handbook, and Ongoing Authorization Methodology after our submission, in

September 2022. As a result of the Department incorporating the applicable

controls from various NIST SPs into its revised policies, it satisfied the intent of

one of the prior recommendations.

29

NIST Special Publication 800-37, Revision 2, was issued December 18, 2018, in which NIST

added a new "Prepare" step.

www.oig.dhs.gov 9 OIG-23-21

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

Weakness Remediation

OMB and DHS require using POA&Ms to track and plan the resolution of

information security weaknesses.

30

We found several components did not

effectively manage the POA&M process as required by DHS. For example,

components did not resolve all POA&Ms within 12 months or consistently

include estimates for resources needed to mitigate identified weaknesses as

required.

Our analysis of 8,344 open unclassified POA&Ms from DHS’ enterprise

management system as of May 31, 2022, showed that 2,350 were past due;

823 were overdue by more than a year, including 229 POA&Ms created for

HVAs; and 29 were overdue by more than 3 years. Of the 2,350 past due

unclassified POA&Ms, 396 had weakness remediation costs estimated at less

than $50,

31

as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Review of 8,344 Open Unclassified POA&MS

Source: DHS OIG analysis of data from DHS’ Enterprise Management System as of May 31,

2022

Based on our review of the May 2022 NSS FISMA Cybersecurity Scorecard, we

found that DHS HQ did not meet DHS’ NSS weakness remediation metrics for

30

OMB Memorandum 02-01, Guidance for Preparing and Submitting Security Plans of Action

and Milestones, October 17, 2001; Policy Directive Number 4300A, Information Technology

System Security Program, Sensitive Systems, Version 13.2, September 20, 2022.

31

To ensure sufficient resources are available to mitigate known information security

weaknesses, DHS requires that components include a nominal weakness remediation cost of

$50 when the cost cannot be estimated due to the complexity of tasks or other unknown

factors.

www.oig.dhs.gov 10 OIG-23-21

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

POA&Ms. This has been a consistent finding in our FISMA reporting since

2003.

Without valid ATOs and aggregated POA&M information, DHS cannot be

assured that effective controls are in place to protect sensitive information

stored and processed by these systems.

According to FY 2022 reporting metrics, our independent contractor rated

components’ Identify Risk Management domain “Level 3 – Consistently

Implemented” for ICE, and “Level 5 – Optimized” for CISA and USCIS.

Supply Chain Risk Management

The Supply Chain Risk Management (SCRM) domain focuses on the maturity of

agency SCRM strategies, policies and procedures, plans, and processes to

ensure that products, system components, systems, and services of external

providers are consistent with the organization’s cybersecurity and SCRM

requirements. This domain aligns with SCRM criteria in NIST SP 800-53,

Rev.5, Security and Privacy Controls for Information Systems and Organizations.

The Department’s management has developed draft SCRM policies and

procedures to ensure products, system components, systems, and services of

external providers are consistent with applicable cybersecurity supply chain

requirements. However, because the Department has not approved these draft

policies and procedures, the actions taken thus far do not effectively address

the maturity level indicators as discussed in the reporting metrics.

According to FY 2022 reporting metrics, our independent contractor rated

components’ Supply Chain Risk Management Domain “Level 3 – Consistently

Implemented” for USCIS, “Level 4 – Management and Measurable” for CISA,

and “Level 5 – Optimized” for ICE.

2. Protect: The “Protect” function entails developing and implementing the

appropriate safeguards to ensure delivery of critical services based on four

FISMA domains: (1) Configuration Management, (2) Identity and Access

Management, (3) Data Protection and Privacy, and (4) Security Training.

We determined DHS was operating at “Level 4 – Managed and Measurable” in

the Protect function. For example, DHS employs automation to resolve found

issues and address configuration changes. However, DHS has not addressed

its identified knowledge, skills, and abilities gaps. In addition, the results from

our August 2022 audit on cyber attack protections

32

revealed that some

components did not (1) ensure all users completed required cybersecurity

32

DHS Can Better Mitigate the Risks Associated with Malware, Ransomware, and Phishing

Attacks, OIG-22-62, August 22, 2022.

www.oig.dhs.gov 11 OIG-23-21

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

awareness training; (2) consistently educate users about the risks of malware,

ransomware, and phishing attacks; and (3) conduct at least one phishing

exercise in the period sampled. Based on technical testing results, DHS had

not implemented security configuration settings for all systems tested; one

component was running an unsupported version of a Windows operating

system on a workstation; and some components did not apply security patches

timely to mitigate critical and high-risk security vulnerabilities on selected

systems tested.

Configuration Management

We determined DHS was operating at “Level 4 – Managed and Measurable” in

the Configuration Management domain. As part of DHS OIG audits and

technical testing conducted during the year, DHS OIG performed security

assessments on six systems, including one HVA at two components

(Component E and Component J). Our testing confirmed that both

components had implemented a vulnerability patch management program.

However, the components did not ensure all known security patch and

software updates were remediated timely. In addition, we found an

unsupported version of Windows operating system on a workstation at

Component J.

We also identified misconfigured security settings on selected workstations,

domain controllers, servers, and mobile devices that may expose DHS data to

unnecessary security risks at the components tested. DHS requires

components document any deviation in implementing the control settings

through waivers or risk-acceptance. When factoring in all available waivers

through a risk acceptance memo, along with our assessment results,

components should arrive at 100% compliance. However, we determined that:

Component E implemented between 98 to 100 percent of the Defense

Information Security Agency Security Technical Implementation Guide

baseline settings.

Component J implemented from 58 to 97 percent of the required Defense

Information Security Agency Security Technical Implementation Guide

baseline settings.

Further, our security assessment revealed critical and high-risk Common

Vulnerability Scoring System vulnerabilities were not remediated timely on the

eight systems tested, including two HVAs at Components E and J. Specifically:

At Component E, we assessed 2 systems, including 1 HVA, and identified

8 critical and 30 high risk unique/individual weaknesses on 527

workstations, domain controllers, and servers tested. Further, at

www.oig.dhs.gov 12 OIG-23-21

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

Component E, we identified 1 unique critical vulnerability, occurring 32

times, that is listed in CISA’s Known Exploited Vulnerabilities catalog.

33

We also assessed two mobile applications and identified two critical and

seven high risk unique/individual weaknesses.

At Component J, we assessed 4 systems, including 1 HVA, and identified

14 critical and 201 high risk unique/individual weaknesses on 780

workstations, domain controllers, and servers tested.

When security patches are not applied in a timely fashion, components could

be subject to potential exploitation. Personnel within Components E and J

stated that the components are taking corrective actions to remediate the

security vulnerabilities identified during our other discretionary audits

conducted this year.

Our independent contractor rated components’ Configuration Management

Domain “Level 1 – Ad-hoc” for CISA, “Level 4 – Managed and Measurable” for

ICE, and “Level 5 – Optimized” for USCIS.

Identity and Access Management

We determined DHS was operating at “Level 4 – Managed and Measurable” in

the Identity and Access Management domain. Identity and access

management is critical to ensuring only authorized users can log onto DHS

systems. DHS has taken a decentralized approach to identity and access

management, leaving its components individually responsible for issuing

Personal Identity Verification (PIV) cards (access cards) for computer and

building access, pursuant to Homeland Security Presidential Directive-12.

34

DHS requires all privileged and unprivileged employees and contractors to use

PIV cards to log onto DHS systems.

Our audit of Component E revealed it does not consistently enforce multifactor

authentication. Component E requires non-privileged and privileged user

accounts to use multifactor authentication with PIV cards for workstations via

Microsoft’s Active Directory Group Policy Object.

35

However, Component E

does not enforce multifactor authentication with PIV cards for servers. Instead,

33

CISA Binding Operational Directive 22-01 – Reducing the Significant Risk of Known Exploited

Vulnerabilities, issued November 3, 2021, establishes a CISA-managed catalog of known

exploited vulnerabilities that carry significant risk to the Federal enterprise and establishes

requirements for agencies to remediate any such vulnerabilities included in the catalog.

34

Homeland Security Presidential Directive-12: Policy for a Common Identification Standard for

Federal Employees and Contractors, dated August 27, 2004, requires Federal agencies to begin

using a standard form of identification to gain physical and logical access to federally

controlled facilities and information systems.

35

Active Directory keeps track of users, computers, and groups. Active Directory uses Group

Policy Objects to enforce security and to limit access to protected resources.

www.oig.dhs.gov 13 OIG-23-21

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

Component E has allowed its privileged user accounts to authenticate with a

username and strong password in accordance with applicable policy. Further,

we identified 259 of 44,585 total users who were allowed to reset the password

for a powerful, privileged account, which Windows used to encrypt access

tickets at Component E. Component E personnel agreed that account

permissions should be reviewed. As of June 2022, Component E stated it had

already disabled some of the identified accounts and removed unnecessary

permissions from others.

As part of our technical testing, we accessed Component J implementation of

Microsoft’s Active Directory and determined that multifactor authentication via

PIV was enforced for its non-privileged users. For privileged accounts,

Component J has implemented strong authentication mechanisms. However,

Component J allowed 61 of 38,102 total users to reset the password for a

powerful, privileged account, which Windows used to encrypt access tickets.

Component J personnel stated that two Active Directory security groups were

inheriting password change permissions they were not intended to have. To

mitigate this weakness, Component J personnel stated they would break these

permission inheritances and correct the problem during their next update.

Our independent contractor rated components’ Identity and Access

Management domain at “Level 4 – Managed and Measurable” for CISA, ICE,

and USCIS.

Data Protection and Privacy

We determined DHS was operating at “Level 2 – Defined” in the Data Protection

and Privacy domain. DHS has not defined policies and procedures to mitigate

against Domain Name System infrastructure tampering. The Department has

not fully encrypted personally identifiable information and other sensitive data.

As part of DHS’ efforts to meet Executive Order 14028’s full encryption

requirement, program officials reported in March 2022 that DHS had only

applied encryption on 86 percent of DHS’ systems for data at rest and 96

percent for data in transit. Under Executive Order 14028, Federal agencies

were required to meet the President’s 180-day target for full encryption by

November 8, 2021.

Our independent contractor rated components’ Data Protection and Privacy

domain at “Level 1 – Ad-hoc” for CISA, “Level 2 – Defined” for ICE, and “Level 5

– Optimized” for USCIS.

Security Training Program

We determined DHS was operating at “Level 3 – Consistently Implemented” in

the Security Training domain. Educating employees about acceptable practices

www.oig.dhs.gov 14 OIG-23-21

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

and rules of behavior is critical for an effective information security program.

DHS has a security training program that DHS HQ, the Office of the Chief

Human Capital Officer, and the components manage collaboratively.

Specifically, the Department uses a Performance and Learning Management

System to track employee completion of training, including security awareness

courses. Components are required to ensure all employees and contractors

receive annual IT security awareness training, as well as specialized training

for employees with significant responsibilities.

DHS has not resolved its identified knowledge, skills, and abilities gaps of its

cyber workforce. As a result, the Department cannot ensure its employees

possess the knowledge and skills necessary to perform job functions, or that

qualified personnel are hired to fill cybersecurity-related positions.

In addition, the results from our August 2022 audit on cyber attack

protections

36

revealed that some components did not (1) ensure all users

completed required cybersecurity awareness training; (2) consistently educate

users about the risks of malware, ransomware, and phishing attacks; or (3)

conduct at least one phishing exercise in the period sampled.

Although the Department has made overall progress in the “Protect” function,

DHS components can further safeguard the Department’s information systems

and sensitive data by:

implementing all configuration settings;

improving identity and access weaknesses at selected components;

replacing unsupported operating systems;

implementing security patches timely; and

resolving identified gaps outlined in its cyber workforce.

According to FY 2022 FISMA Reporting Metrics, our independent contractor

rated components’ Security Training domain at “Level 1 – Ad-hoc” for CISA,

“Level 4 – Managed and Measurable” for USCIS, and “Level 5 – Optimized” for

ICE.

3. Detect: The “Detect” function entails developing and implementing

appropriate activities, including ongoing systems authorization and continuous

monitoring, to identify any irregular system activity.

36

DHS Can Better Mitigate the Risks Associated with Malware, Ransomware, and Phishing

Attacks, OIG-22-62, August 22, 2022.

www.oig.dhs.gov 15 OIG-23-21

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

Information Security Continuous Monitoring

We determined that DHS was operating at “Level 3 – Consistently

Implemented” in this function. The Department updated its 4300A Policy,

Handbook, and Ongoing Authorization Methodology after our FY 2022

submission to OMB, as referenced earlier in this report. As a result of the

Department incorporating the applicable controls from various NIST SPs into

its revised policies, it satisfied the intent of one of the prior recommendations.

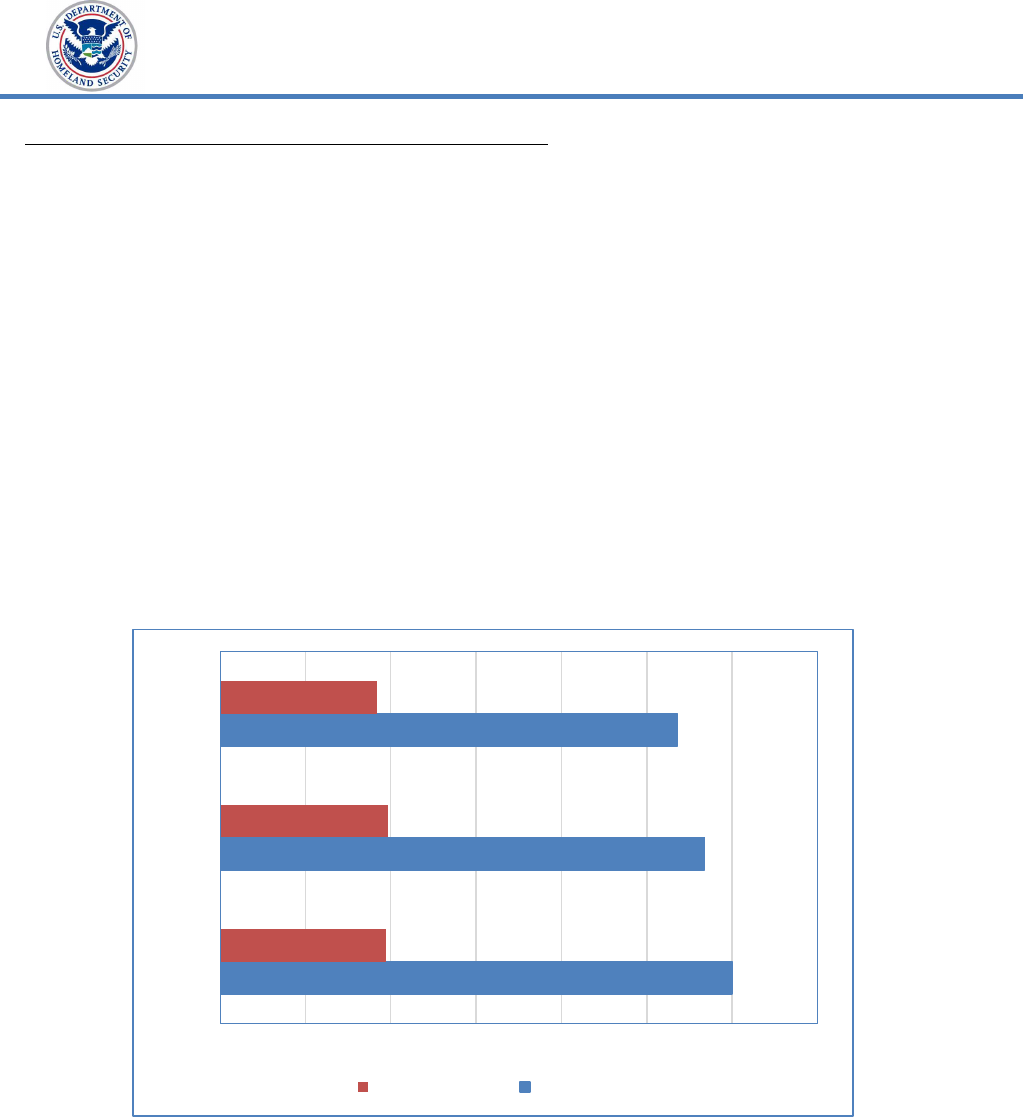

As of May 2022, eight components were enrolled in the Department’s ongoing

authorization program. The Department had decreased the number of systems

enrolled in the program by 2 percent from FY 2021 to FY 2022, as shown in

Figure 4. According to a DHS official, the decrease in system enrollment was

due to components decommissioning systems previously in the Ongoing

Authorization Program.

Figure 4. DHS Systems Enrolled in the Ongoing

Authorization Program from FY 2020 to FY 2022

600

568

536

194

197

184

FY 2022

FY 2021

FY 2020

0 100 200 300 400 500 600 700

Systems Enrolled

Total Systems

Source: DHS OIG-compiled based on DHS Office of the CISO data

Our independent contractor rated components’ Detect function at “Level 1 –

Ad-hoc” for CISA and “Level 4 - Managed and Measurable” for ICE and USCIS.

4. Respond: The “Respond” function entails developing and implementing

appropriate responses to detected cybersecurity events.

www.oig.dhs.gov 16 OIG-23-21

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

Incident Response

We determined DHS was operating at “Level 4 – Managed and Measurable” in

this function. However, our August 2022 audit on cyber attack protections

37

revealed that DHS can better protect its sensitive data from potential malware,

ransomware, and phishing attacks by revising its policies and procedures to

incorporate applicable new controls, in accordance with OMB policy. DHS can

also ensure its users receive the required security awareness training to

mitigate the risk.

Our independent contractor rated components’ Respond function at “Level 3 –

Consistently Implemented” for CISA, “Level 4 – Managed and Measurable” for

ICE, and “Level 5 – Optimized” for USCIS.

5. Recover: The “Recover” function entails developing and implementing plans

for resiliency and restoration of any capabilities or services impaired due to

outages or other disruptions from a cybersecurity event.

Contingency Planning

We determined DHS was operating at “Level 4 – Managed and Measurable” in

this function. DHS defined its policies, procedures, and strategies for

information contingency planning, but did not fully test these plans. For

example, as of May 2022, DHS had not tested 17 unclassified systems

contingency plans.

DHS has a department-wide business continuity program to restore essential

business functions and resume normal operations in response to emergency

events. As part of this program, DHS implemented a Reconstitution

Requirements Functions Worksheet to collect information about components’

key business requirements and capabilities needed to recover from attack or

disaster. DHS used this information to develop a Reconstitution Plan outlining

macro-level procedures for all DHS senior leadership, staff, and components to

follow to resume normal operations as quickly as possible in the event of an

emergency. The procedures may involve both manual and automated

processing at alternate locations, as appropriate.

DHS components are responsible for developing and periodically testing such

contingency plans outlining backup and disaster recovery procedures for the

respective information systems.

38

However, as of May 31, 2022, we identified

the following deficiencies:

37

DHS Can Better Mitigate the Risks Associated with Malware, Ransomware, and Phishing

Attacks, OIG-22-62, August 22, 2022.

38

DHS Policy Directive Number 4300A, Information Technology System Security Program,

Sensitive Systems, Version 13.2, September 20, 2022.

www.oig.dhs.gov 17 OIG-23-21

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

Our review of the May 2022 NSS FISMA Cybersecurity Scorecard showed

that DHS HQ did not meet DHS’ NSS compliance target for contingency

plan testing.

More specifically, ICE, the Management Directorate, the Science and

Technology Directorate, the Transportation Security Administration,

39

and USCIS had not tested contingency plans for 17 of 600 unclassified

systems, based on our analysis data from DHS’ enterprise management

system.

A well-documented and tested contingency plan can ensure the recovery of

critical network operations. Untested plans may create a false sense of

security and an inability to recover operations timely.

According to FY 2022 FISMA Reporting Metrics, our independent contractor

rated components’ “Recover” function at “Level 2 – Defined” for USCIS and

“Level 3 – Consistently Implemented” for CISA and ICE.

Summary of Selected Components’ Implementation of Information

Security Programs

Our independent contractor rated component information security programs

effective for ICE and USCIS, as each achieved “Level 4 – Managed and

Measurable” or higher in three of the five functions. CISA’s overall information

security program was rated not effective because it only achieved “Level 4 –

Managed and Measurable” or higher in one of five functions. Table 5

summarizes the implementation of information security programs by CISA,

ICE, and USCIS.

39

After the issuance of our draft report Transportation Security Agency informed DHS OIG the

system was decommissioned in September 2022.

www.oig.dhs.gov 18 OIG-23-21

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

Table 5. Summary Status of CISA, ICE, and USCIS Information Security

Programs for FY 2022

Function CISA ICE USCIS

Identify Level 5 – Optimized Level 5 – Optimized Level 5 – Optimized

Protect Level 1 – Ad-hoc

Level 4 – Managed

and Measurable

Level 5 – Optimized

Detect Level 1 – Ad-hoc

Level 4 – Managed

and Measurable

Level 4 – Managed and

Measurable

Respond

Level 3 –

Consistently

Implemented

Level 4 – Managed

and Measurable

Level 5 – Optimized

Recover

Level 3 –

Consistently

Implemented

Level 3 – Consistently

Implemented

Level 2 – Defined

Overall Rating Ineffective Effective Effective

Source: DHS OIG contractor-compiled summary status information

Since 2019, our independent contractor has performed fieldwork at 12 selected

components and rated 5 components’ information security programs as

“ineffective” because the components achieved below “Level 4 – Managed and

Measurable” in three of five functions, in accordance with the FY 2022 FISMA

Reporting Metrics.

Recommendation

Recommendation 1: We recommend the DHS Chief Information Officer

enforce the requirements for components to obtain Authority to Operate their

systems, promptly use sufficient resources to create and monitor Plans of

Action and Milestones to mitigate known information security weaknesses, and

ensure contingency plans are tested.

Management Comments and OIG Analysis

We obtained written comments on a draft of this report from the Director of the

Departmental Government Accountability Office-OIG Liaison Office (Director),

who expressed the Department’s appreciation for OIG’s work planning and

conducting its review and issuing this report. We reviewed the Department’s

comments, as well as the technical comments previously submitted under

separate cover, and updated the report as appropriate.

www.oig.dhs.gov 19 OIG-23-21

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

Response to Report Recommendation:

The Department concurred with the recommendation. Following is a

summary of DHS’ response to the recommendation and the OIG’s analysis.

DHS Comments to Recommendation: Concur. The Department provided the

corrective actions to address deficiencies identified.

Deficiency 1: Systems were operating without an Authority to Operate.

In FY 2022, DHS CISO worked through the DHS CISO Council on a weekly

basis to address compliance and security matters facing the Department, such

as system authorizations, compliance with Executive Order 14028, and Zero

Trust architecture development. As a result, the percentage of systems

operating with a current ATO and updated contingency plans rose from 78

percent of the Department population in the first quarter of FY 2022 to 97

percent in the fourth quarter of FY 2022.

Throughout FY 2022, DHS CISO established the Department’s standards for

Ongoing Authorization. The DHS CISO Council approved this program on

January 26, 2023. The Department expects the new standards for Ongoing

Authorization will be published by the end of March 2023 as Attachment BB,

DHS Ongoing Authorization Program, of DHS Policy Directive 4300A, Information

Technology System Security Program, Sensitive Systems. This program provides

all DHS FISMA reportable system owners the opportunity to streamline their

compliance activities to avoid the scheduling factors that sometimes complicate

system ATO renewal. Estimated Completion Date: September 30, 2023.

Deficiency 2: POA&Ms used to mitigate known information security

weaknesses were past due or not updated.

In March 2022, DHS leveraged its Unified Cybersecurity Maturity Model

framework to prioritize the overdue POA&M in the Management Directorate

immediate prioritized remediation. According to the Department, the Unified

Cybersecurity Maturity Model framework was key to identifying which overdue

POA&Ms needed to be addressed immediately to improve the cybersecurity

posture of the Management Directorate’s systems and successfully closed

about 64 percent of the overdue POA&Ms. The Department is implementing

this POA&M prioritizing method at other components. Additionally, DHS

implemented this framework in FY 2023 as part of its monthly scorecard

process to guide cybersecurity maturity improvements for the Department.

Estimated Completion Date: September 30, 2023.

Deficiency 3: Security configuration settings were not implemented for all

systems tested

.

www.oig.dhs.gov 20 OIG-23-21

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

DHS has developed an annual Information Security Performance Plan based on

OMB’s FISMA cybersecurity metrics, which includes new standards and

associated scoring for compliance with Defense Information Security Agency

Secure Technical Implementation Guide. This new standard has increased

awareness and compliance with system configurations across all Department

components and FISMA systems. The DHS Office of the Chief Information

Officer (OCIO) expects this will improve security configuration settings

compliance for all DHS FISMA systems throughout FY 2023. Estimated

Completion Date: September 30, 2023.

Deficiency 4: Selected components had identity and access weaknesses.

OCIO continues to lead the adoption of Multifactor Authentication for 100

percent of Department’s FISMA systems. By the first quarter of FY 2023, the

Department stood at 93 percent compliance. OCIO also initiated an overhaul

of the entire Department’s standards for privileged account issuance and

management. Since the beginning of FY 2023, OCIO has been updating an

attachment to DHS 4300A to clearly reflect the minimum standards for the

review, approval, and issuance of privileged accounts on any DHS FISMA

system. This effort will standardize the process for the provisioning and

deprovisioning of privileged accounts department-wide. Estimated Completion

Date: September 30, 2023.

Deficiency 5. An unsupported version of a Windows operating system was

running on a component workstation.

OCIO continues to work with the components to improve compliance with all

Information Security Performance Plan metrics, one of which is using fully

supported operating systems by upgrading to the current approved version of

Windows. The Department tracks this metric in the DHS Monthly FISMA

Scorecard using Information Security Performance Plan-defined metrics for

prohibited operating systems. DHS will continue to work to upgrade all

systems found to be using an unauthorized version of Windows. Estimated

Completion Date: September 30, 2023.

Deficiency 6. Some components did not promptly apply security patches to

mitigate critical and high-risk security vulnerabilities on selected systems tested.

OCIO prioritized the maturation of component patching capabilities in FYs

2022 and 2023. To date, the Department has increased its centralized

patching capability to reach 88 percent of all DHS. OCIO has prioritized

increasing the adoption of centralized patching capability so that it reaches 100

percent of DHS endpoints. Estimated Completion Date: September 30, 2023.

www.oig.dhs.gov 21 OIG-23-21

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

Appendix A

Objective, Scope, and Methodology

The Department of Homeland Security Office of Inspector General was

established by the Homeland Security Act of 2002 (Public Law 107−296), which

amended the Inspector General Act of 1978.

The objective of our evaluation was to determine whether DHS’ information

security program and practices were adequate and effective to protect the

information and information systems that support DHS’ operations and assets

for FY 2022. Our independent evaluation focused on assessing DHS’

information security program using requirements outlined in the FY 2022

Inspector General Federal Information Security Modernization Act of 2014

(FISMA) Reporting Metrics. Specifically, we evaluated DHS’ information security

program’s compliance with requirements outlined in five NIST Cybersecurity

Functions.

We performed our fieldwork at the DHS Office of the CISO and at selected

organizational components and offices: CISA, ICE, and USCIS. To conduct our

evaluation, we interviewed relevant DHS HQ and component personnel,

assessed DHS’ current operational environment, and determined compliance

with FISMA requirements and other applicable information security policies,

procedures, and standards. Specifically, we:

reviewed the results from our FY 2019, FY 2020, and FY 2021 FISMA

evaluations and used them as baselines for the FY 2022 evaluation;

evaluated policies, procedures, and practices DHS implemented at the

program and component levels;

reviewed DHS’ POA&Ms and ongoing authorization procedures to

determine whether security weaknesses were identified, tracked, and

addressed;

evaluated processes and the status of the department-wide information

security program reported in DHS’ monthly information security

scorecards regarding risk management, contractor systems,

configuration management, identity and access management, security

training, information security continuous monitoring, incident response,

and contingency planning; and

developed an independent assessment of DHS’ information security

program.

We incorporated technical testing results from other projects, and we also

included results from discretionary projects conducted during the same fiscal

year. We reviewed information from DHS’ enterprise management systems to

determine data reliability and accuracy. We found no discrepancies or errors

www.oig.dhs.gov 23 OIG-23-21

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

in the data. OIG contractors performed fieldwork at CISA, ICE, and USCIS to

support our evaluation.

We conducted this review between May 2022 and February 2023, under the

authority of the Inspector General Act of 1978, as amended, and according to

the Quality Standards for Inspection and Evaluation issued by the Council of

the Inspectors General on Integrity and Efficiency. We did not evaluate OIG’s

compliance with FISMA requirements during our review.

www.oig.dhs.gov 24 OIG-23-21

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

Appendix C

Major Contributors to This Report

Chiu-Tong Tsang, Director

Shawn Hatch, Audit Manager

Stefanie Tynes, Auditor-in-Charge

Sonya Davis, Auditor-in-Charge

Brendan Burke, Auditor

Bridgette OgunMokun, Auditor

Lawrence Polk, Cybersecurity Specialist

Thomas Rohrback, Director, Cybersecurity Risk Assessment Division

Rashedul Romel, Supervisory IT Specialist

Jason Dominguez, IT Specialist

Taurean McKenzie, IT Specialist

Thomas Hamlin, Communications Analyst

Brandon Landry, Referencer

www.oig.dhs.gov 29 OIG-23-21

OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL

Department of Homeland Security

Appendix D

Report Distribution

Department of Homeland Security

Secretary

Deputy Secretary

Chief of Staff

Deputy Chiefs of Staff

General Counsel

Executive Secretary

Under Secretary, Office of Strategy, Policy, and Plans

Assistant Secretary for Office of Public Affairs

Assistant Secretary for Office of Legislative Affairs

Chief Information Officer

Chief Information Security Officer

Audit Liaison, Office of the Chief Information Officer

Audit Liaison, Office of the Chief Information Security Officer

Audit Liaisons, U.S. Customs and Border Protection, Federal Emergency

Management Agency, ICE, Office of Intelligence and Analysis, USCIS, CISA,

Science and Technology Directorate, Transportation Security Administration,

Coast Guard, and Secret Service

Office of Management and Budget

Chief, Homeland Security Branch

DHS OIG Budget Examiner

Congress

Congressional Oversight and Appropriations Committees

www.oig.dhs.gov 30 OIG-23-21

Additional Information and Copies

To view this and any of our other reports, please visit our website at:

www.oig.dhs.gov.

For further information or questions, please contact Office of Inspector General

Follow us on Twitter at: @dhsoig.

OIG Hotline

To report fraud, waste, or abuse, visit our website at www.oig.dhs.gov and click

on the red "Hotline" tab. If you cannot access our website, call our hotline at

(800) 323-8603, fax our hotline at (202) 254-4297, or write to us at:

Department of Homeland Security

Office of Inspector General, Mail Stop 0305

Attention: Hotline

245 Murray Drive, SW

Washington, DC 20528-0305